Health matters: making cervical screening more accessible

Updated 31 August 2017

Summary

Attendance for cervical screening has been falling year on year. This professional resource aims to address this decline in attendance by presenting recommendations that can help increase access to screening and awareness of cervical cancer.

Scale of the problem

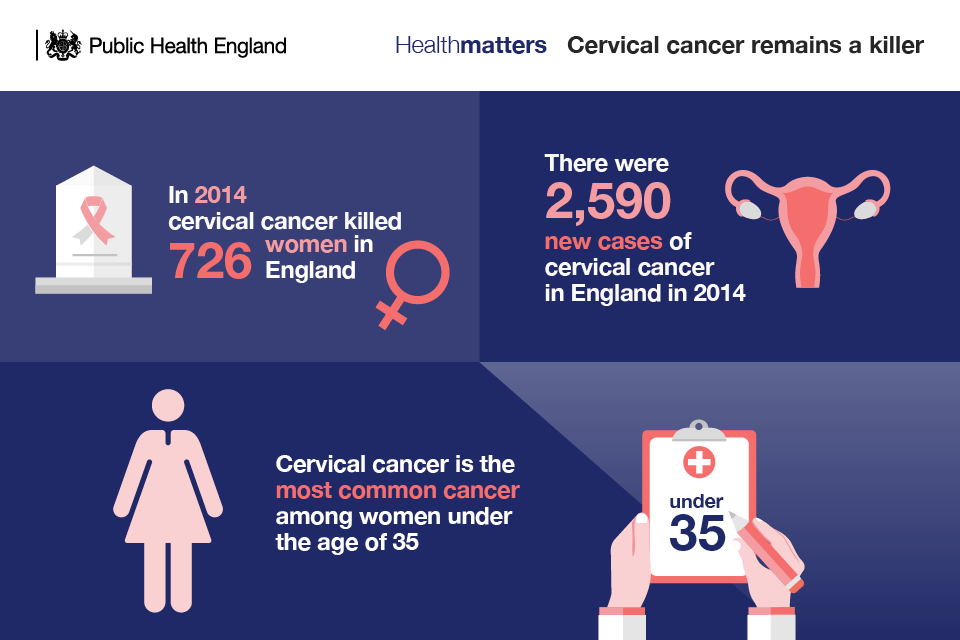

In 2014, there were 2,590 new cases of cervical cancer in England and a total of 3,224 new cases in the UK, according to Cancer Research UK. That works out at around 9 new cases of cervical cancer a day. These were seen in almost all in women who were too old to benefit from the vaccination programme.

In recent years, cervical cancer has become the most common cancer among women under the age of 35.

Although cervical cancer mortality rates have decreased by up to 70% since the introduction of the NHS cervical screening programme in 1988, there were still 726 deaths from the disease in England in 2014 and a total of 890 in the whole of the UK. The crude mortality rate shows that there are 3 cervical cancer deaths for every 100,000 females in the UK.

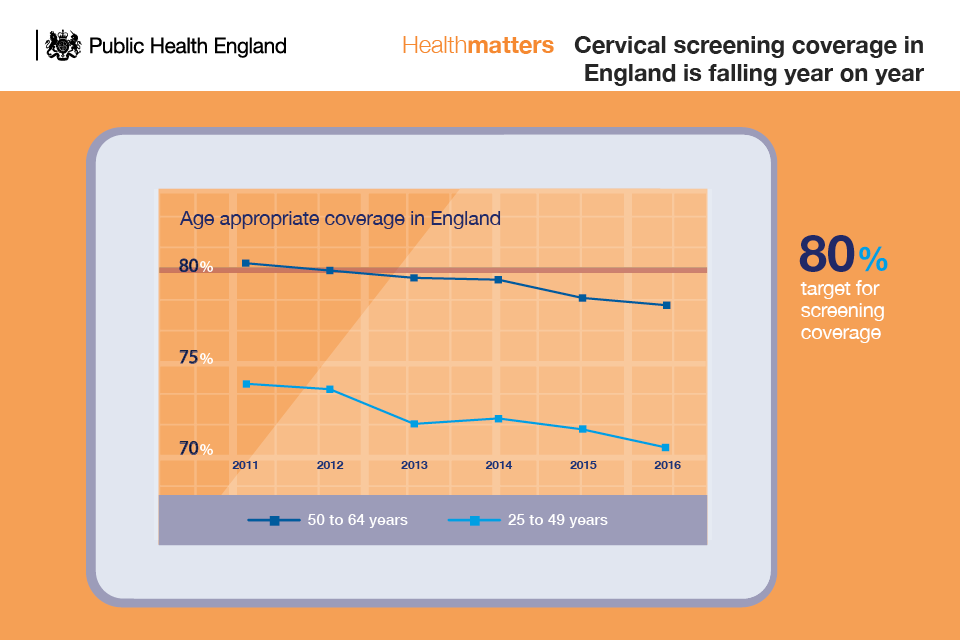

Despite the success of the programme, screening coverage has fallen over the last 10 years and attendance is now at a 19-year low. Coverage is going down across all age groups.

Screening figures collected by NHS Digital show that coverage amongst women aged 25 to 49 years was 70.2% at 31 March 2016. This compares to 71.2% as at 31 March 2015 and 73.7% as at 31 March 2011. For women aged 50 to 64 years, the coverage at 31 March 2016 was 78.0% which compares to 78.4% as at 31 March 2015 and 80.1% as at 31 March 2011.

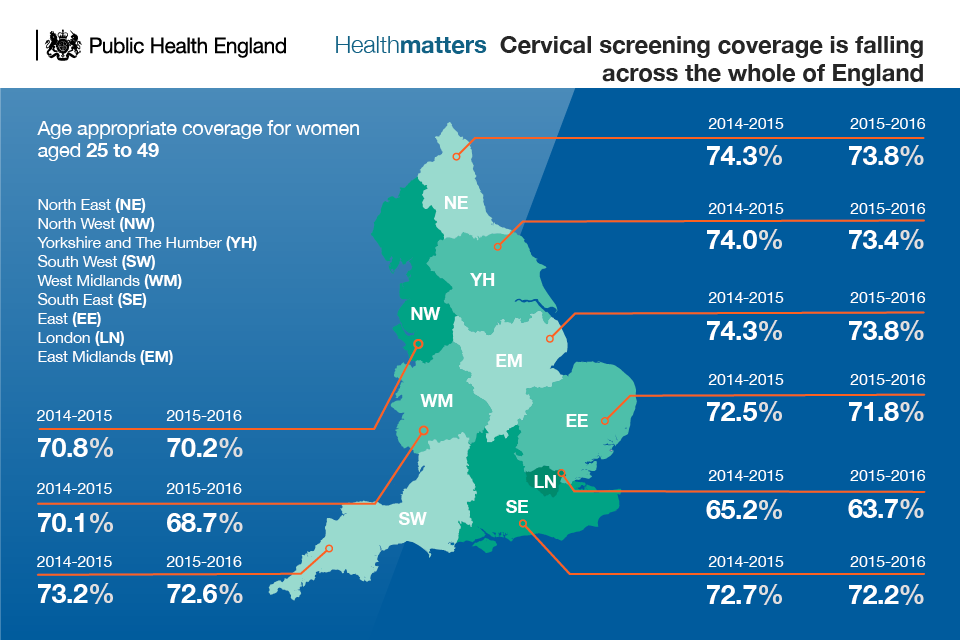

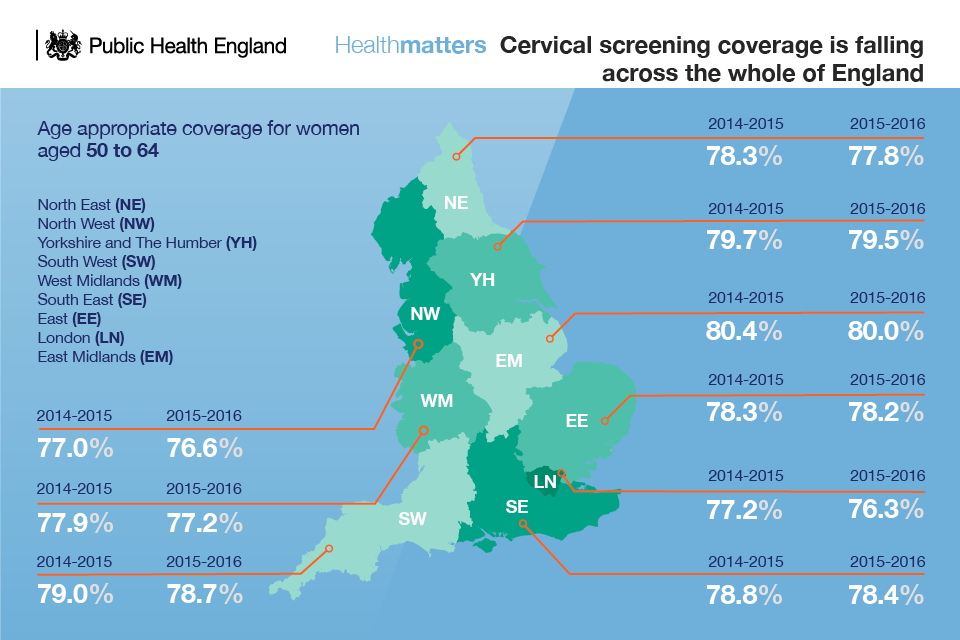

At a regional level, coverage of the full eligible age group in 2016 ranged from 66.7% in London to 75.9% in the East Midlands. The vast majority of reporting regions reported a fall in coverage at 31 March 2016 when compared with 2015.

51 out of 160 local authorities achieved coverage of 75% and above. 58 local authorities achieved coverage of 70% to less than 75%. The national target for cervical screening coverage is 80%.

There was a fall of 2.4% in the number of women aged 25 to 64 years invited for screening in 2015 to 2016 compared with the previous year. In total, 4.21 million women were invited, most of whom were aged 25 to 49 (3.26 million) with women aged 50 to 64 accounting for 0.95 million of those invited.

Declining coverage of cervical screening has serious implications not just for cervical cancer diagnosis rates and mortality, but also financial implications for the NHS, and the wider economy.

Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust has calculated that raising screening coverage to 84% could save the NHS £10 million a year and also prevent the Treasury losing up to £6 million in tax revenues, and significantly ease the impact on survivors’ personal finances.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programme

The UK HPV immunisation programme started in 2008. All girls aged 12 to 13 are offered the HPV vaccine as part of the NHS adolescent vaccination programme. The HPV programme is mainly provided through schools and has one of the most successful implementation records in the world. Since the start of the programme in 2008 more than 8.5 million doses of HPV vaccine have been given in the UK, with close to 90% of eligible teenagers vaccinated.

Human papillomaviruses cause more than 99% of all cervical cancers. The HPV vaccine currently used in the UK programme protects against the 2 HPV types (HPV 16 and 18) that cause most cases (over 70%) of cervical cancer. The vaccine also provides protection against other less common cancers and genital warts, the most common viral sexually transmitted infection in the UK.

Surveillance data already suggest that the programme is achieving its aims. The vaccine has contributed to a significant decrease in rates of infection with the 2 main cancer-causing human papillomaviruses in women and men. This is consistent with very high vaccine effectiveness among those vaccinated and suggests that herd-protection is also lowering prevalence among those who are not vaccinated. The UK programme is expected to eventually prevent hundreds of deaths from cervical cancer every year.

Vaccination status must be recorded on the local child health information system (CHIS) and GP clinical records to make sure girls who are not up to date can be vaccinated before their 18th birthday. HPV vaccination details should also be uploaded on to the National Health Application and Infrastructure Services (NHAIS) system (Open Exeter) so that as these young women become eligible for the NHS Cervical Screening programme (currently at the age of 25 in England) their immunisation history is known. In June 2017 PHE published updated guidance for commissioners and providers on access to Open Exeter, uploading HPV vaccination data and viewing and downloading vaccine coverage data for different cohorts.

Making cervical screening more accessible

NHS cervical screening programme

Cervical screening is not a test for cervical cancer. Screening is intended to detect abnormalities within the cervix that could, if undetected and untreated, develop into cervical cancer.

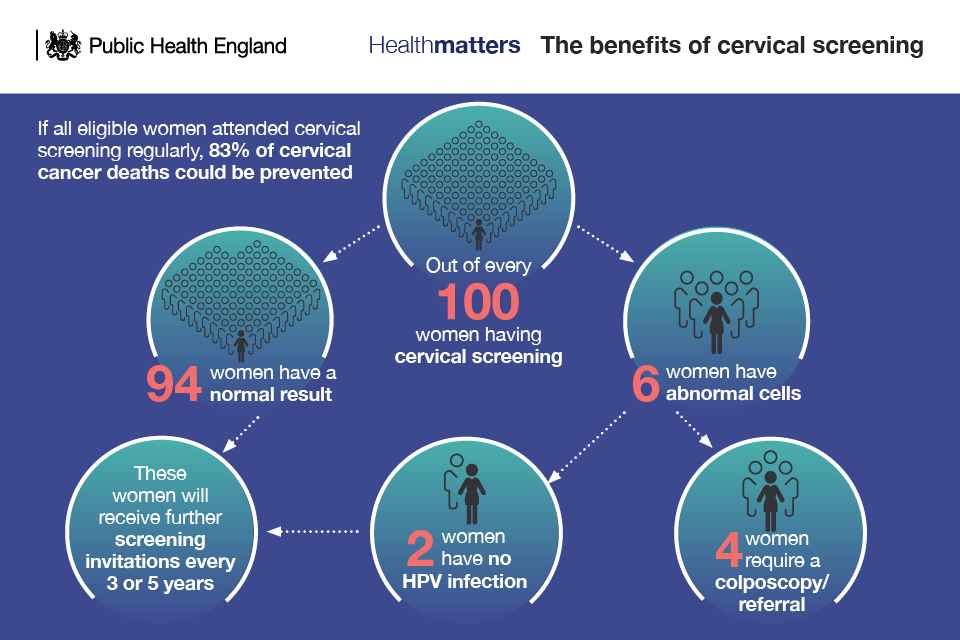

A study on the impact of cervical screening on cervical cancer mortality estimated that in England cervical screening currently prevents 70% of cervical cancer deaths. However, if everyone attended screening regularly, 83% could be prevented.

Women are offered screening every 3 or 5 years depending on their age. Women aged 25 to 49 are invited for routine screening every 3 years, whereas those aged 50 to 64 are invited for routine screening every 5 years.

The programme uses liquid based cytology (LBC) to collect samples of cells from the cervix. A cytologist will examine these samples under the microscope to look for any abnormal changes in the cells.

HPV testing is also used in the programme to help manage women who have low grade abnormal cell changes and as a test of cure in women who have received treatment for abnormal cell changes.

Following a successful pilot scheme, primary HPV testing will be introduced into the cervical screening programme during 2019. This means that all cervical screening samples will be tested for HPV first, and will only go on to have cytology testing if HPV is found. Primary HPV testing has been shown to be a more effective screening test.

Screening starts at 25

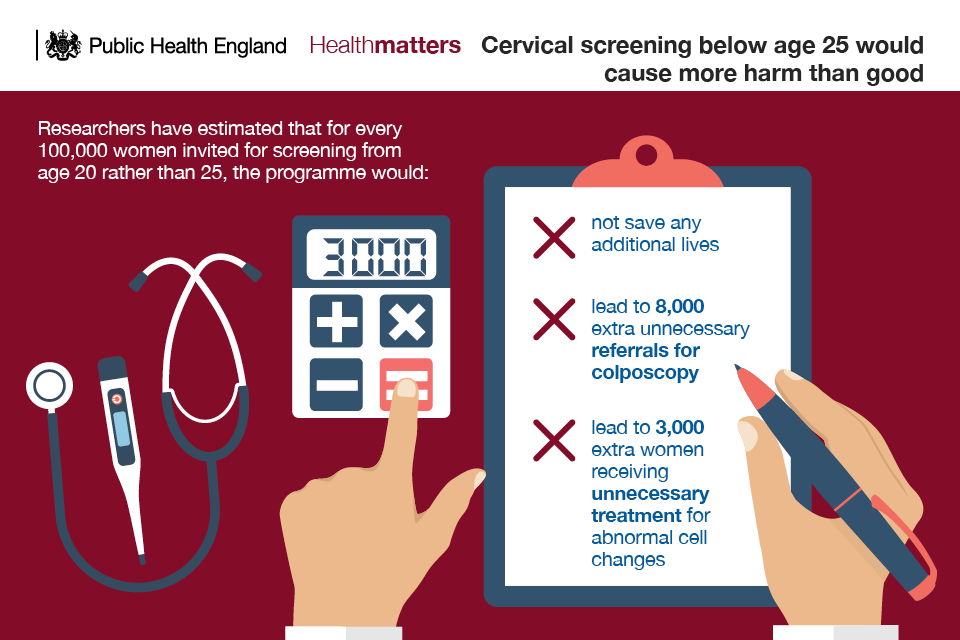

In England, the cervical screening programme is offered to women just before their 25th birthday. There have previously been calls to lower the screening age to 20. The UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) is responsible for assessing the evidence and making recommendations to the 4 UK governments about population screening programmes. UK NSC had a consultation on the starting age for cervical screening in 2012 and recommended not to invite women for cervical screening until the age of 25.

Based on the balance of evidence inviting healthy women under 25 for cervical screening would be likely to do more overall harm than good.

In younger women, abnormal cell changes in the cervix develop more often than in older women but are much more likely to clear up by themselves.

Younger women are more likely to receive an abnormal test result but the cell changes found in younger women are less likely to develop into cancer. Younger women are therefore more likely to have unnecessary further investigations and treatments.

Women with symptoms of cervical cancer

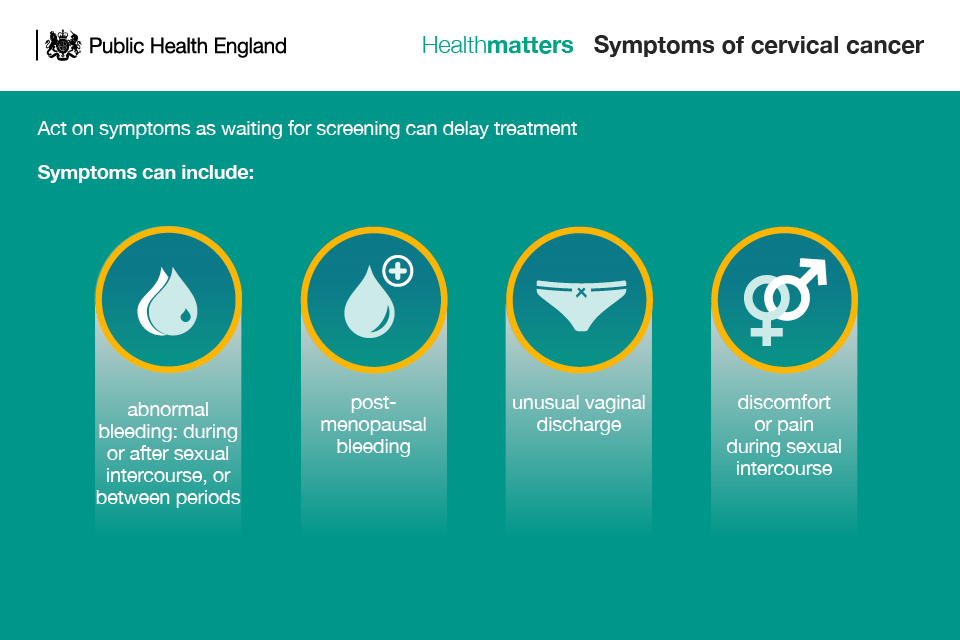

If a woman has symptoms of pain or bleeding between periods or after menopause then a screening test could actually cause delay in getting specialist treatment. The screening test isn’t a cancer test, it just indicates whether further investigations are needed.

If a woman has symptoms, we know she requires further investigation; waiting for a screening result would be unnecessary and would simply delay this. There is cervical screening guidance for GPs on how to manage women with symptoms.

Lower back pain is often associated with the symptoms above.

Health professionals, most typically GPs, should be alert to the symptoms of cervical cancer and should refer women for further investigation where necessary.

Department of Health guidelines for young women aged 20 to 24 state that women experiencing vaginal bleeding after sex and in between periods be offered a speculum examination either in primary care or at a genito-urinary medicine (GUM sexual health) clinic in line with NICE guidance.

Addressing barriers to screening attendance

Not going for cervical screening is one of the biggest risk factors for developing cervical cancer.

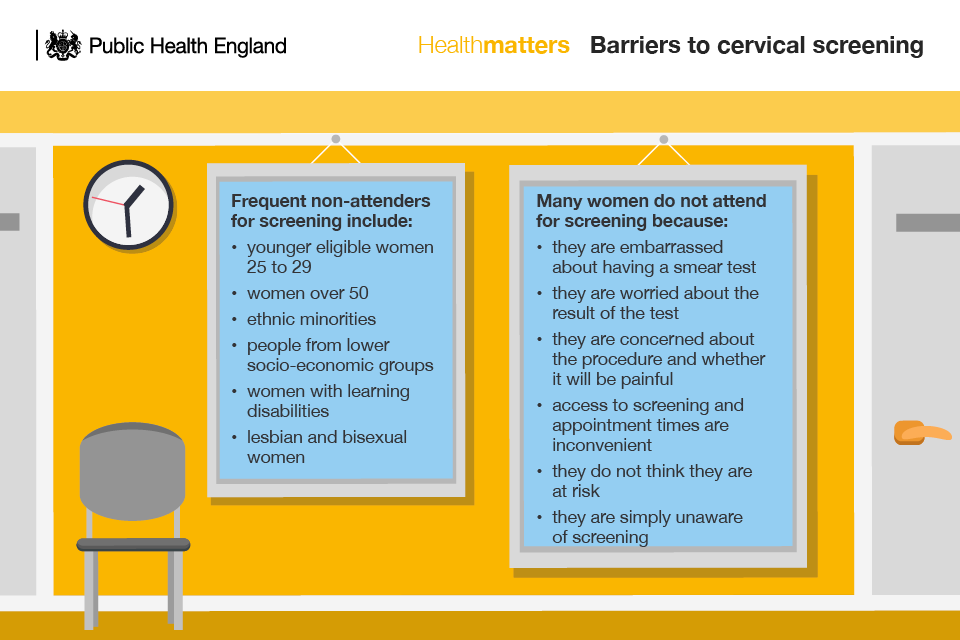

Other reasons for not attending for screening include:

- cultural or language barriers

- no female sample takers being available

- not understanding HPV and the role it plays in cervical cancer development

Several studies have identified groups that are frequent non-attenders for screening.

Women over 50

The number of older women attending their cervical screening appointments is at a 17-year low. In England, screening coverage in 2014 to 2015 was 81.6% for 50 to 54 year olds falling to 74.8% of 55 to 59 year olds and 73.2% of 60 to 64 year olds.

A lack of knowledge about the cause of cervical cancer and who can be affected appear to be contributing to older women not attending cervical screening.

A survey by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust found that 29.1% of women over 50 have found the smear test painful since growing older, including 24.4% experiencing pain since going through the menopause.

Younger women

A study on cervical cancer prevention and screening: the role of human papillomavirus testing, published in June 2017, found that coverage was just 63% in UK women aged 25 to 29 in 2014.

A survey conducted by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust on the knowledge of and barriers to cervical screening in the first invited cohort (25 to 29 year olds) and last (60 to 64 year olds) revealed:

- 26% of 25 to 29 year olds worried that the procedure would be painful and embarrassing

- 1 in 10 women aged 25 to 29 though that the test would pick up other sexually transmitted diseases

- 1 in 10 of 25 to 29 year olds worried about what the results would say

Anecdotally, some health professionals have expressed concerns that younger women may not be taking up screening because they have been vaccinated against HPV and incorrectly believe that they are no longer at risk of cervical cancer.

Ethnic minorities

Ethnicity has been associated with lower attendance for cervical screening.

A study by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust on the differing understanding of cervical screening among white women and women from a Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) community found that a third more BAME women of screening age (12%) compared to white women (8%) said they had never attended screening. 30% of Asian women reported not knowing what cervical screening is.

Poor understanding of what the test was for and why it was important has been highlighted as a barrier to cervical screening, with twice as many BAME women (30%) as white women (14%) saying that better knowledge about the test and its importance would encourage them to attend the screening.

Furthermore, only 28% of BAME women said they felt comfortable talking to a male GP about cervical screening, compared with 46% of white women.

A UK study on the barriers to cervical cancer screening among ethnic minority women involving interviews with women from a range of ethnic minority backgrounds (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Caribbean, African, black British, black other, white other) and 11 white British women identified a number of potential emotional barriers (fear, embarrassment and anticipated shame) as well as low perceived risk among some ethnic groups.

Language and cultural differences can affect understanding or the screening process. It is important to take measures to ensure all women understand the purpose of the screening programme and the procedure for taking the sample. Language translations of the screening invitation leaflet are available to download. Primary care is responsible for sourcing and offering language support during sample taking if needed.

Deprivation

Deprivation has been linked to lower screening attendance and a higher rate of cervical cancer incidence. This may be due to a combination:

- higher rates of smoking

- early age of first coitus

- multiple sexual partners

- lower socio-economic status

Women with learning disabilities

Research on access to cancer screening in people with learning disabilities in the UK found that people with learning disabilities are 45% less likely to be screened for cancer compared to their counterparts without learning disabilities.

Public Health England (PHE), in association with Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, has created The Smear Test Film, a health education film resource for women eligible for cervical screening who have mild and moderate learning disabilities.

Health professionals should share the film with women who have learning disabilities and their carers to help inform them about screening and the role in preventing cervical cancer.

Lesbian and bisexual women

Sometimes, lesbian women have been incorrectly advised by health workers that they don’t need screening because they don’t have sex with men. Or, they may be told by other lesbians that they don’t need to be screened. However, women should be offered screening and consider attending, regardless of their sexual orientation.

A literature review on cervical screening in lesbian and bisexual women commissioned by the NHS cervical cancer screening programme in 2009 found that uptake of cervical screening is up to 10 times lower among lesbian and bisexual women.

Lesbian and bisexual women should be given the correct information to enable them to make an informed choice to participate in screening and vaccination in the same way as heterosexual women.

There is no evidence to suggest that lesbian or bisexual women should be screened any more or less often.

Transgender

Trans men aged 25 to 64, who are still registered with the GP as female will routinely be invited for cervical screening. PHE information for trans people advises that trans men consider having cervical screening if they have not had a total hysterectomy and still have a cervix.

Trans men aged 25 to 64 and registered with a GP as male will not be invited for cervical screening. GPs should advise that screening is recommended if they have not had a total hysterectomy and still have a cervix. Trans women, aged 25 to 64, won’t need to be screened if they don’t have a cervix.

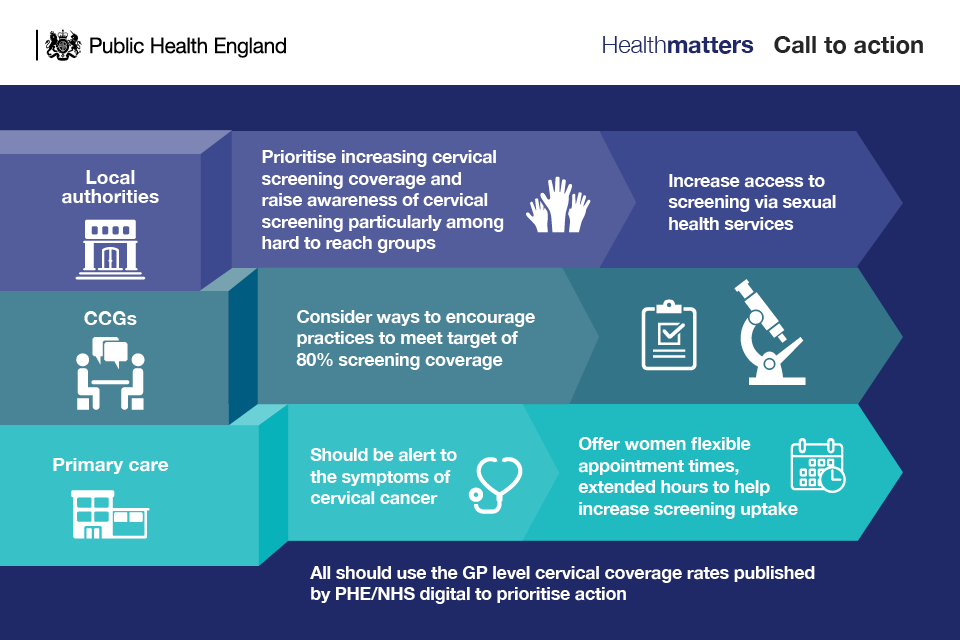

Call to action

The cervical screening in the spotlight report by Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust has highlighted wide variations in activities undertaken by local authorities and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and the need to do more to promote cervical screening and increase uptake.

Listed below are a number of ideas, some that have been used for other screening programmes, that may help to increase screening coverage.

Local authorities need to raise awareness of cervical screening. Awareness is the first stage necessary before behaviour can occur, and awareness is, of course, essential to informed choice.

However, almost half (44%) of local authorities have not undertaken any activities to increase screening attendance in the last 2 years.

Local authorities can work directly with GP surgeries to raise awareness of screening as well as through:

- local resident magazines, issuing press releases and using digital channels such as social media

- posters and information across a wide range of venues including hairdressers, pharmacies, libraries, gyms, children’s centres, job centres and public toilets

- directly with women in their communities

- through targeted information provision

Local authorities should ensure that provision of screening though sexual health services is maintained. Some women, in particular women who work, will find it more convenient to go to a sexual health service rather than making an appointment with their GP. Some women may find it more practical to include cervical screening at the same time as other tests, or they may find it less embarrassing to see a sexual health practitioner rather than their local family’s doctor or practice nurse.

CCGs

Almost two-thirds (60%) of CCGs have not undertaken any activities to increase screening attendance in the last 2 years, according to Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust.

CCG commissioners alongside local authorities need to map out the situation in their local area using PHE data so they can target resources in increasing uptake among certain populations such as ethnic minority groups and older women.

CCGs should use PHE’s interactive screening coverage tool to investigate screening coverage for their practices and how they compare with neighbouring CCGs.

The tool provides data on the number of women in each practice that have not had a smear test but remain eligible for screening in the practice. It can be used to support practices to identify the size of the cohort to address.

Quality schemes, such as the use of locally enhanced services, may help to improve screening coverage.

Primary care teams

GPs and practice nurses can play a central role in educating women and therefore in increasing attendance for screening.

All women must be given the opportunity to make an informed choice about whether or not to attend for cervical screening. The decision should be based on an understanding of:

- why they are being offered screening

- what happens during the test

- the benefits and risks of screening

- the potential outcomes (including types of result, further tests and treatment)

- what happens to their screening records

Training

GPs and practice nurses should also be alert to the symptoms of cervical cancer. Practices should consider:

- holding educational events or sessions on cervical screening as part of GP Protected Learning Time

- provide training to staff including receptionists and health trainers so they can positively promote cervical screening

- work with public health colleagues to promote local awareness campaigns and to train non-clinical cancer champions

Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust provides awareness raising resources for primary care, and there is a cervical screening awareness week in June each year.

Improving uptake

Evidence demonstrates that GP endorsement has a positive effect on cervical screening uptake.

The cervical screening programme sends a standard invitation letter and a reminder letter 18 weeks later to women who are eligible for cervical screening. Standard letters sent by the programme can include an additional paragraph of free text specific to a GP practice.

The registered GP sends out a second reminder letter to non-attenders. This provides an opportunity to tailor the practice invitation according to the services the practice provides and the practice population. Helpful content includes:

- surgery opening times

- reassurance that the sample taker will be female

- offering opportunities for a conversation about any screening concerns

The use of alerts or screen prompts for anyone who defaults provides an opportunity for clinicians to raise awareness that screening is available and that individuals remain eligible.

Access

Providing a variation of appointment times during the day and in the evening will help women in choosing when they can attend for screening. Limiting access to screening appointments can impact on coverage.

Identifying need

Individual practices should also use PHE’s interactive screening coverage tool to investigate screening coverage for their practices and how they compare with neighbouring practices. The data will be updated every 3 months and will therefore provide more up to date information than the current annual statistical report.

Practices should consider:

- working with neighbouring GP practices that have low attendance to implement initiatives to follow up with non-attenders

- working with public health colleagues to promote local awareness campaigns and to train non-clinical cancer champions

Voluntary sector

The voluntary sector has a role to play in helping to raise awareness of cervical screening using their knowledge of local communities and through their outreach programmes.