Biological Security Strategy: summary of public response

Updated 15 June 2022

Introduction

Published in March 2021 the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy (the Integrated Review) set out the vision for the UK’s role in the world over the next decade. The Review set out the need to review and reinforce the cross-government approach to biological security, including a refresh of the 2018 Biological Security Strategy. As part of the work to refresh the strategy in 2022, the government will reevaluate the risk landscape and consider the evolving priorities since COVID-19 and in light of rapid advances in science and technology.

Biological security in this context covers:

- a major health crisis (such as pandemic influenza or new infectious disease)

- Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

- a deliberate biological attack by state or non-state actors (including terrorists)

- animal and plant diseases, which themselves can pose risks to human health

- accidental release and dual-use research of concern

In support of the refresh of this Strategy, on 16 February 2022 a Call for Evidence was published on GOV.UK. It closed for submissions on 01 April 2022. Input and challenge from a wide range of technical experts was sought on topics related to biological security including the key challenges, opportunities, threats and vulnerabilities, how the UK can capitalise on opportunities (for example, COVID-19 mitigations, lab standards, overseas health systems), lessons since the 2018 strategy was issued and approaches to monitoring and evaluation of the strategy.

The responses have now been reviewed and analysed with material being shared with the relevant policy teams in government and informing the development of the strategy. The refreshed Biological Security Strategy will be published in autumn 2022.

Response Statistics

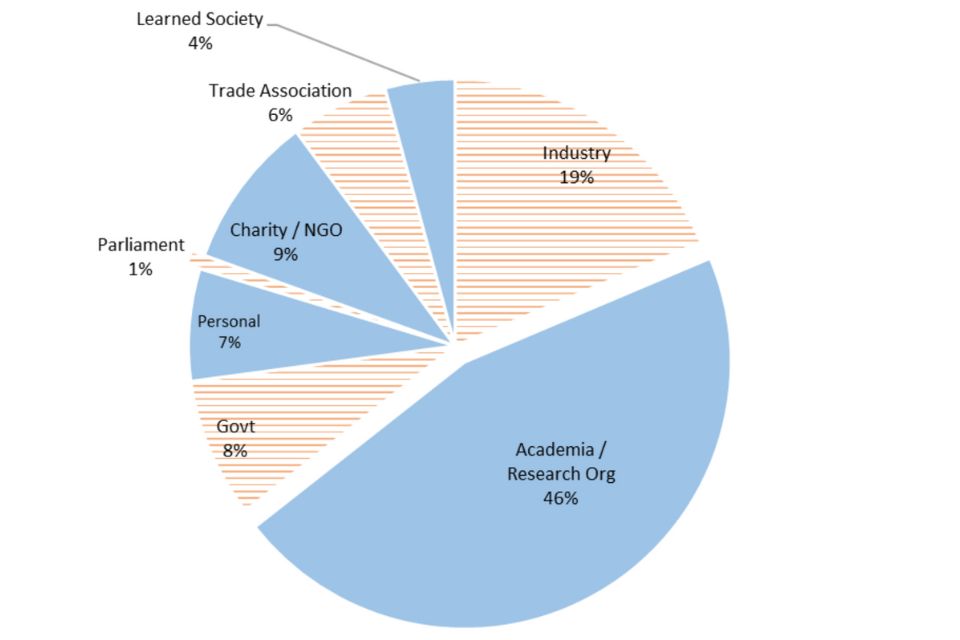

61 responses were submitted representing 118 individuals and organisations. 77% of the 118 identified themselves as having good insight or expert knowledge of their particular field of biological security. A wide range of sectors were covered in the responses, highlighted in the table below, and respondents were mainly located in the UK.

Figure 1: Breakdown of sectors providing Call for Evidence responses (NGO - Non-Government Organisation)

| Sectors | Breakdown of sectors |

|---|---|

| Academia/Research Org | 46% |

| Industry | 19% |

| Charity/NGO | 9% |

| Government | 8% |

| Personal | 7% |

| Trade Association | 6% |

| Learned Society | 4% |

| Parliament | 1% |

Key Themes

This section provides an overview of the key themes drawn out of the responses. The Call for Evidence mainly consisted of open questions, therefore solicited a wide range of responses. There was no requirement for respondents to answer all the questions.

Risk

Noting that the majority of responses focussed on naturally occurring risks due to the sectors the respondents were representing, overall the Call for Evidence responses indicated an agreement there is an increase in overall risk from biological security threats out to 2030. Key considerations included:

- climate change and globalisation factors (for example, trade, intensive farming, conflict, travel) are leading to changing patterns of human, animal and plant health which are exacerbating the risk from naturally occuring threats (for example, increasing prevalence of zoonoses and vector-borne diseases)

- AMR is the growing ‘silent’ pandemic

- increased likelihood of accidental release and potential for misuse due to the:

- pace and scale of advances in biotechnology coupled with technological convergence

- a lack of international oversight of the proliferation of high containment labs, driven by an increase in funding for gain-of-function research

- democratisation of science leading to the proliferation of ‘experts’ with the information, access and skills to perform potentially dangerous research. Guidance and oversight mechanisms have not kept pace with technological developments and are currently insufficient

- COVID-19 has exposed vulnerabilities to biological threats, which may incentivise malicious actors to pursue bioweapons. Non-proliferation efforts may become more difficult given the lack of international oversight of high containment laboratories around the world and the advent of misinformation in this area[footnote 1].

Governance and leadership

Responses emphasised the importance of a whole-of-government (encompassing integration across defence and security and one-health[footnote 2]) approach to biological security with clear accountability, and greater use of collaboration fora to draw in external expertise. Regarding the question of a single, accountable role or body to meet the full range of biological threats[footnote 3]: 31% of respondents supported this idea citing its potential role to improve coherence and coordination. However there were concerns about whether this could increase bureaucracy, focus too much attention on one area of risk or dilute expertise. Alternative solutions such as strengthening existing systems and implementing better pan-department oversight and coordination were suggested. 54% of respondents chose not to answer this question. Submissions cited the importance of periodic review of the strategy alongside regular, publicly available monitoring and evaluation[footnote 4] activities against clearly defined goals and timelines.

Data and analysis

Improving access to data, data-sharing mechanisms and interoperability between governments and external partners nationally and internationally were seen as key to detect biological threats. There was support for sustainable domestic and international early warning and surveillance systems to generate real-time data on naturally occurring pathogens and rapid alerts for deliberate biological threats that may be used for malicious intent. Furthermore, the importance of the scientific infrastructure and skills (for example, high-performance computing and modelling) to underpin these capabilities was acknowledged. Responses recognised the need for the UK to continue to play a leadership role in efforts to develop global surveillance systems and capacity building support to Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) in this respect.

Horizon scanning and foresight

The need to maintain an updated, accurate biological security risk picture covering all potential deliberate and naturally occurring threats was identified. Respondents suggested better and more regular horizon-scanning and foresight mechanisms were required which also draw out new technologies and the opportunities and risks they present.

Domestic and international regulation

Responses identified a need to strengthen the Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)[footnote 5], both by increasing its remit and improving its funding. Building international laws and restrictions to address concerns around the democratisation of science were also raised, where increasing access to DNA synthesis risked use by hostile actors and required regulatory oversight. Responses discussed reducing biothreats by limiting their potential for disruption to the UK, and deterring them as a viable option for malicious state and non-state actors.

Research and laboratory standards, safety and security

25% of respondents supported a greater role for standards, safety and security. 64% of respondents chose not to answer this question. Responses particularly focussed on the proliferation of BSL3/4[footnote 7] laboratories, the pace and scale of technological change / technology convergence[footnote 8] and the democratisation of science (for example, DIY Biology[footnote 9]) as examples of the drivers for this. There was a general view that formal oversight mechanisms to mitigate risks throughout the research cycle should be reviewed, whilst also encouraging better self-regulation.

Lessons from COVID-19

Responses indicated that experience and interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic could be usefully drawn upon to maintain sustainable levels of Life Sciences research, capacity and long-term manufacturing capabilities. In particular, closer working relationships and collaboration models between government, industry and academia to strengthen biological security aims were drawn out.

Leveraging international best practice

Many responses cited that the UK should continue to leverage its status as a centre of research excellence to promote the science base and influence international policy on biological security. Where examples of best practice the UK might learn from were requested[footnote 10], the USA was the most frequently cited international comparator for a range of measures including its import systems and approach to research and development. Australia and New Zealand were mentioned for their border measures and cautious approach to biological security, and South Korea and Singapore for their emergency health security approaches.

International fora

The UK was recommended to continue to engage with and support the LMIC countries most likely to first encounter naturally occurring biological threats, those existing international bodies and groups such as the UN Biorisk Working Group / UN Office for Disarmament Affairs, the WHO’s Pandemic Intelligence Hub and Global AMR and Use Surveillance System (GLASS), and charities that work globally to strengthen health capabilities and resilience overseas. Driving improvements in shared global standards and encouraging strengthened biological security across international borders was recommended as a means to aid UK biological security.

Investment

Responses cited a greater need for targeted interventions, sustained investment and incentivisation to ensure the UK has the right science focus and capacity, manufacturing base and stockpiling capabilities. This covered two main areas: investment in science; here vaccinology and genomic surveillance were discussed frequently, and investment in industry, in the context of UK resilience and the ability to rapidly scale-up a response.

Borders

Responses described the role and importance of borders to both prevent and detect biological security threats entering the UK. With global economies being increasingly interconnected, the need to focus on monitoring animals, plants and food (particularly exotic species) entering the UK to prevent potential importation of pathogens or pathogen-containing vectors was highlighted, noting the opportunities Brexit has provided. Greater border monitoring was highlighted as a requirement to detect and identify these threats to UK biological security.

Communication to raise awareness

Training and education on biological security risks, including how research could be mis-used across the Life Sciences sector and those sectors converging with Life Sciences (for example, artificial intelligence) was noted as needing more focus in the responses. Additionally there was an acknowledgement of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in heightening the public’s knowledge of biosecurity; pathogen spread, preventative behaviours and non-pharmaceutical interventions which can be built upon to support other aspects of awareness raising for biological security. Conversely, responses noted the pandemic had highlighted misinformation in public health and this needed to be addressed.

Ongoing engagement

The Call for Evidence contributions are one of several information sources being used to inform the development of the Biological Security Strategy and ensure it is driven by a strong and diverse evidence base (including from outside government). As the Strategy develops, the Cabinet Office is continuing to engage with external experts to develop its policy proposals.

For further information please contact biosecuritystrategy@cabinetoffice.gov.uk.

-

Note: the Call for Evidence opened shortly before the Russian aggression against Ukraine started on 24 February 2022; the heightened biological security threat level with reference to this conflict was discussed in 10% of responses. ↩

-

‘One Health’ is an approach to designing and implementing programmes, policies, legislation and research in which multiple sectors communicate and work together to achieve better public health outcomes. The ‘One Health’ approach is critical to addressing health threats in the animal, human and environment interface - WHO definition (https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-policy/one-health). ↩

-

Question 3 (c) in the Call for Evidence. ↩

-

Question 4 in the Call for Evidence. ↩

-

See https://www.un.org/disarmament/biological-weapons/ “The Biological Weapons Convention” ↩

-

Question 2 (h) in the Call for Evidence. ↩

-

Labs are classified depending on what level threat of biological material they have the facilities and training to contain. Biosafety level one labs handle pathogens not known to consistently cause disease in humans, and BSL-4 labs handle the most high risk, often aerosol transmitted, pathogens; such as smallpox. https://www.phe.gov/s3/BioriskManagement/biosafety/Pages/Biosafety-Levels.aspx ↩

-

The tendency for technologies that were originally unrelated to become more closely integrated and even unified as they develop and advance. ↩

-

DIY biology is an umbrella term for people doing all manner of biology experiments in unconventional settings - https://www.rsb.org.uk/biologist-features/the-unlikely-labs. ↩

-

Question 3 (d) in the Call for Evidence. ↩