Call for evidence on data sharing and open data in banking

Updated 18 March 2015

1. Introduction

1.1 About this call for evidence

At Autumn Statement 2014 the government made clear its intention for the UK to be the global centre for financial technology and to lead the world in open source data in banking. The government announced new measures designed to support business and consumer lending through online peer to peer platforms and, as part of the government’s Midata initiative, confirmed that Gocompare would be the first company to build a comparison tool to enable customers for the first time to get detailed comparisons of personal customer accounts by using their bank data.

In addition to this, the government published the report Data Sharing and Open Data for Banks written by the Open Data Institute and consultancy firm Fingleton Associates, and committed to launch a call for evidence in early 2015 on how best to deliver an open standard for application programming interfaces (APIs) in UK banking and to ask whether more open data in banking could benefit consumers.

The Autumn Statement announcement on APIs and open data.

In this call for evidence the government is seeking views from interested parties on how the recommendations set out in the report should be developed, what benefits more open data in banking could bring to consumers and, in particular, how an open API standard in UK banking could best be delivered.

The government will then consider the responses and what actions are required to deliver positive outcomes in this area, including an open API standard for UK banks. Any other views or suggestions that respondents wish to put forward on any of the discussion points raised or other relevant areas not specifically covered here are also welcomed.

The government would also like to understand how quickly these recommendations could be taken forward to ensure that consumers can realise the benefits as soon as possible.

A summary of the views the government is requesting as part of this call for evidence is in Chapter 4.

1.2 Who should respond to this call for evidence?

The government would expect banks, consumer groups, financial services providers, card schemes, payment institutions, financial technology firms and app and software designers to be interested in responding to this call for evidence, but welcomes views from anybody interested in the subjects of data sharing through APIs and open data in banking.

1.3 Background on data sharing and open data

Application programming interfaces, or APIs, allow two pieces of software to talk to one another. In banking, APIs can be used to enable financial technology (fintech) firms to make use of bank data on behalf of customers in innovative and helpful ways. For instance, through external bank APIs customers can make use of applications on their smartphones which allow them to see clearly how much money they spend on food, and how their spending on food fluctuates through the course of a month or year.

Open data refers to data that can be used and redistributed by anyone for free, and for example in banking can be used to improve the ability of challenger banks or alternative finance providers to make effective decisions about who to lend money to, or enable comparison applications to make more detailed and accurate assessments of how customers can save money.

In considering how the UK can remain at the forefront of financial technology and innovation, in June 2014 the government commissioned the Open Data Institute, who engaged Fingleton Associates, to explore how competition and consumer outcomes in banking could be affected by the publication of more open data and by banks giving customers the ability to share their bank data with third parties using APIs.

Their report explains that improving the ability of customers to share their bank data with third parties through external APIs, and increasing the quantity of data published by banks as open data, could provide a number of benefits to customers and to competition in UK banking.

The report sets out a number of recommendations on how these two initiatives could best be taken forward:

-

banks agree an open API standard for third party access

-

independent guidance should be provided on technology, security and data protection standards that banks can adopt to ensure data sharing meets all legal requirements

-

an industry wide approach should be established to vet third party applications and publish a list of vetted applications as open data

-

standard data on PCA terms and conditions published by banks as open data

-

credit data should be made available as open data

The government agrees that these recommendations could bring very significant benefits to consumers, and to financial technology and innovation.

2. Why and how open data and an open API standard can increase competition in banking

2.1 Benefits of data sharing and open data in banking

The government is determined to drive more competition in the UK banking sector. More competition in banking means that banks have to work harder to innovate and provide the best possible products and services for customers, and that customers get more choice about where and how to bank.

Ensuring customers, banks and alternative finance providers have the data and information they need is central to a competitive banking industry:

-

customers need to have the right information on the types of products and services available to them, and be able to compare them effectively to make informed decisions on who to bank with

-

banks and alternative finance providers need the right data to understand better what products and services their customers need. This enables challenger banks and alternative finance providers to enter into the market and compete effectively, and design products for underserved areas of the market

Giving customers more choice about how they use their bank data can also support greater competition in banking. Banks, alternative finance providers and fintech firms would have more incentive to develop innovative applications which utilise bank data on behalf of customers, and compete to offer new products that customers can benefit from.

Put simply, increasing the amount of data that is available, and making it easier for people to use, will improve competition and innovation in UK banking and create a richer banking experience for customers.

2.2 Open data

More open data in banking would increase the amount of data for customers, banks and alternative finance providers to use.

Open data is the publication of non-personal data in aggregated form which is machine readable and can be used by anyone. The British Bankers’ Association (BBA) already publishes information on where banks are lending by geographical region as open data.

The publication of more open data by banks could provide alternative finance providers and fintech firms with a richer source of information to make effective lending decisions and to make better use of customer bank data. For example, publishing the prices of, and terms and conditions associated with, banks’ products as open data and in real-time would help to facilitate a more accurate comparison of products by comparison websites.

2.3 APIs

APIs are the easiest and most effective way for customers to make use of their bank data.

APIs are sets of instructions that allow one piece of software to connect with another. Outside of banking, APIs are used to provide a variety of functions to good effect. Mobile phone applications like Twitter or Facebook use APIs to connect data on their servers with third parties and the customer’s mobile phone, and companies like Uber, airbnb and Opentable use APIs to connect their drivers, their hosts and restaurants with customers in real time. For example, Uber uses APIs to plug into drivers’ and passengers’ GPS data, identify where the drivers are in relation to the passengers, and inform the passengers when the driver is one minute away and when the driver has arrived.

However, while some financial services providers and financial technology firms in the UK have begun to make use of APIs in banking, their full potential has not been explored to date.

Currently, the most common process which enables customers to allow third parties to make use of their bank data on their behalf is ‘screen-scraping’. Screen-scrapers work by getting online banking log-in details from individuals, then using them to access their account data on their behalf. While screen-scrapers can provide individuals with a number of useful services, such as adding together how much a customer spends on transport across all of a customer’s accounts, there are obvious privacy and security concerns with providing secure log-in details to a third party, and in the UK customers would, in many cases, be violating their banks’ Terms and Conditions.

Given the risks with screen-scraping technologies for personal bank data, the government has been pursuing an alternative solution over the last 12 months: Midata. Midata allows customers to download their account data from their online banking and upload it into an online comparison tool (or, in theory, any other useful application). It therefore does not require customers to divulge their log in credentials to a third party. As set out above, the government announced at Autumn Statement 2014 that customers would be able to make use of their Midata by April of this year, and that Gocompare would be the first company to build a comparison tool to enable customers to get detailed comparisons of personal customer accounts using their bank data.

The government believes that the process and potential application for customers using their bank account data could be simplified and broadened through APIs.

Like screen-scrapers, APIs provide a mechanism for customers to share their bank data with a third party without the need for input each time. However, unlike screen-scrapers APIs do not require customers to provide their internet banking log-in credentials to the third party. Furthermore, unlike Midata, APIs work without requiring customers to download and then upload their bank data, so there is no limitation to APIs working on popular brands of smartphone and or tablet.

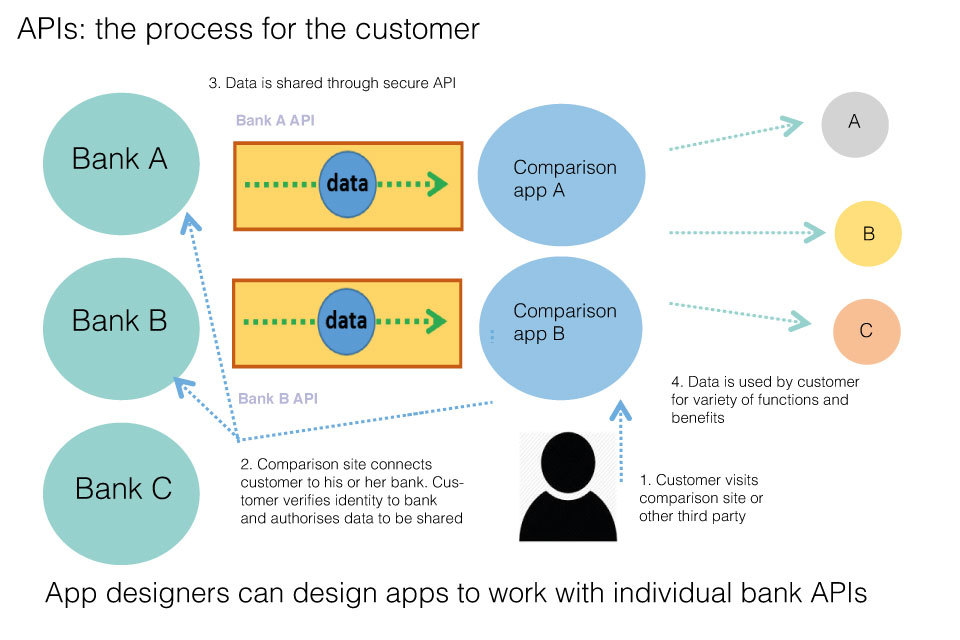

The diagram below sets out how APIs could work in banking:

Diagram 1: using an external API in banking

APIs: Diagram 1

APIs in banking can work by the customer logging into their internet banking and giving permission for a third party to access their bank data on their behalf directly. The bank data that a third party can review and the functions that the third party can use the data for via an API can be controlled by the customer’s bank. For instance, a bank could allow a third party to see some data, such as which restaurants the customer likes to eat at in order for that third party to provide relevant promotional offers, but it could redact more sensitive customer information. The bank could also play a role in ensuring that only approved third parties are able to access customers’ bank data, and ensuring that customers are aware of what data will be accessed and what the data can and cannot be used for. As such, external APIs can be used in a way that is consistent with the requirements of the Data Protection Act, and sensitive to privacy concerns. Nevertheless, the government recognises that understanding fully issues around consumer protection and security and privacy of data from an open API standard are essential to ensuring its effective delivery, and we invite views on these points below.

The French bank Crédit Agricole has been an early adopter of external APIs to enable its customers to connect with third party applications and allow them to make use of their bank data on their behalf. An application (‘app’) store lists all of the available products and services for Crédit Agricole’s customers to choose from. Available applications range from monitoring trends in a customer’s spending to providing a detailed breakdown of how much a customer spends on healthcare.

Fintech firms could develop applications to make use of a range of other services which are available to customers. For instance, an app developer could design an app to work on a customer’s smartphone, which uses the customer’s GPS data and bank data to provide advice on what products or services that customer may like to buy in any given area. The example cited in the report is that a customer could receive advice on whether or not to buy a cheaper coffee, or to forgo it altogether, on entering a coffee shop if they have exceeded their pre-set budget for that month.

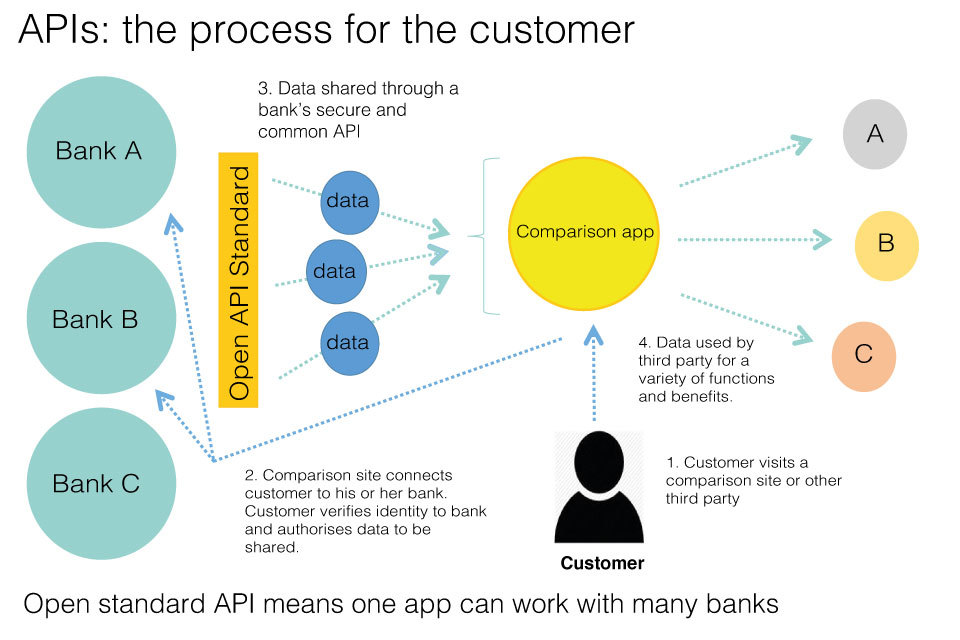

As recommended in the report, the government wants to go beyond how APIs are currently used in other countries, to deliver an open API standard in UK banking. An open API standard would entail UK banks developing a single and common API, which is publicly available and can be used by any fintech firm or app developer to design products or apps which work for all UK banks. This would help to create a better market for app development and a greater ecosystem for fintech firms and developers to work within, as a single app could then connect with, and be used by customers from, any bank. This would help to ensure that the UK remains at the forefront of financial technology and innovation.

The diagram below sets out how an open API standard could work in UK banking:

Diagram 2: an open API standard

APIs Diagram 2

3. The report on data sharing and open data for banks

This section sets out some of the key conclusions of the ODI’s and Fingleton Associates’ report and asks questions to be considered by respondents.

Their report sets out in detail what APIs are, how they work, and how an open API standard in UK banking could benefit customers and help to increase competition. It states that the Personal Current Account and SME banking markets in particular could benefit from external bank APIs, but that a range of financial services markets and companies operating within those markets stand to gain from an improved ability to share data and information. For instance, consumer advice and comparison services would benefit from being able to provide predictive and real-time advisory and comparison tools; SME lenders could make use of new financial management tools and a quicker and more accurate credit assessment; and banks could act as platforms for third party innovation and have the opportunity to develop a more varied suite of digital products.

The report estimates that that it would cost around £1million per bank to develop an open API standard, and that the implementation of an open API standard could be completed from start to finish within a year.

While the government intends to deliver an open API standard in banking, we are not intending at this stage to define the scope of who should contribute to its development, or who could make use of it and how. Having said that, our focus is on the main providers of personal current accounts but we are interested to understand how widely we should be considering its development and potential application. We welcome views on all these points below.

The Government is interested to understand:

Question 1

What benefits and risks could arise from an open API standard?

Question 2

What can the government do to facilitate the development and adoption of an open API standard?

Question 3

Who should play a role in the development of an open API standard and who should be able to make use of it and how?

Question 4

What are the costs likely to be for banks, or other financial services firms and providers of credit, developing an open API standard in banking?

Question 5

The government would like to deliver an open API standard in banking as quickly as possible. Are there practical issues which could affect quick delivery? Would 1 to 2 years be a reasonable timescale for delivery?

The report explains some of the standards that should accompany the use of an open API standard in banking and how it could operate:

-

before a third party could access a customer’s bank data through an API the customer would be required to give their consent to their bank

-

customers need to be able to authenticate themselves with their bank in a simple, informed and secure way

-

external APIs can be designed by banks to restrict or control what information can be accessed, and who they can be accessed by

-

the bank should be responsible for setting out precisely what information will be accessed and how that data will be used

-

the customer has ongoing control and visibility over terms of access to their data and can revoke permission at any time

-

an open API standard can enable fintech firms or developers to build applications that interact with it

-

third party access to the API should be governed by a vetting process

-

the technical and security standards governing the use of an open API standard should meet the highest of requirements.

The government is interested to understand:

Question 6

What issues would need to be considered in terms of data protection and security, and what is the best way to address these?

Question 7

What are the technical requirements that an open API standard should meet?

The report also considers the benefits of open data and how, in particular, more open data in banking could support growth, help to increase competition in banking and improve consumer choice. Additional datasets that could be provided range from aggregated data on current account performance and loan defaults to ATM locations, branch opening hours and standardised terms and conditions around interest rates on credit balances.

The government is interested to understand:

Question 8

What benefits do respondents see from the publication of more open data in banking?

Question 9

What issues would need to be considered in terms of data protection and security, and what is the best way to address these?

Question 10

What are the other risks or costs of publishing more open data in banking, and how can they be addressed?

The report concludes by setting out a number of recommendations that could help to improve data sharing and open data in banking:

-

banks agree an open API standard for third party access

-

independent guidance should be provided on technology, security and data protection standards that banks can adopt to ensure data sharing meets all legal requirements

-

an industry wide approach should be established to vet third party applications and publish a list of vetted applications as open data

-

standard data on PCA terms and conditions published by banks as open data

-

credit data should be made available as open data

Question 11

Do respondents agree with the recommendations set out in the report?

Question 12

If so, what action do they think is required by banks and the government to bring them about?

4. Summary of views requested

The call for evidence has asked for views on a number of different topics. Please find a summary of the views sought below.

Table 1: summary of views requested

| 1 | What benefits and risks could arise from an open API standard? |

| 2 | What can the government do to facilitate the development and adoption of a shared API standard by the major UK banks? |

| 3 | Who should play a role in the development of an open API standard and who should be able to make use of it and how? |

| 4 | What are the costs likely to be for banks, or other financial services firms and providers of credit, developing an open API standard in banking? |

| 5 | The government would like to deliver an open API standard in banking as quickly as possible. Are there practical issues which could affect quick delivery? Would 1 to 2 years be a reasonable timescale for delivery? |

| 6 | What issues would need to be considered in terms of data protection and security, and what is the best way to address these? |

| 7 | What are the technical requirements that an open API standard should meet? |

| 8 | What benefits do respondents see from the publication of more open data in banking? |

| 9 | What issues would need to be considered in terms of data protection and security, and what is the best way to address these? |

| 10 | What are the other risks or costs of publishing more open data in banking, and how can they be addressed? |

| 11 | Do respondents agree with the recommendations set out in the report? |

| 12 | If so, what action do they think is required by banks and the Government to bring them about? |

5. Call for evidence responses

5.1 How to respond

When responding please say if you are a business, private individual or representative body. In the case of representative bodies please provide information on the number of people or businesses you represent.

Please send your responses by 25 February 2015 to: Datasharing.CfE@hmtreasury.gsi.gov.uk

Alternatively, you can write to:

Data Sharing and Open Data in Banking

Banking and Credit Team

HM Treasury

1 Horse Guards Road

London

SW1A 2HQ

5.2 Confidentiality

Information provided in response to this call for evidence, including personal information may be published or disclosed in accordance with access to information regimes. These are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) and the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

If you want information that you provide to be treated as confidential please be aware that, under FOIA, there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals with, amongst other things, obligations of confidence. In view of this it would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on HM Treasury.

HM Treasury will process your personal data in accordance with the DPA and in the majority of circumstances this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to third parties.

5.3 Consultation principles

This call for evidence is being run in accordance with the government’s consultation principles.

The government’s consultation principles state that ‘timeframes for consultation should be proportionate and realistic’. This Call for Evidence will run for [four] weeks, which should be sufficient time for stakeholders to consider and respond, given the likely audience. The government considers that this is an appropriate amount of time to review the report and the questions raised, and contribute to this evidence-gathering exercise.