COVID-19 testing and vaccination in a deprived local authority: Blackpool

Describes obstacles experienced by Blackpool Council and its public health team in supporting testing, and local responses implemented to overcome challenges.

Executive summary

This case study describes the experiences of those working in Blackpool Council and its public health team in supporting testing and vaccination among vulnerable groups, as well as some of the local responses implemented to overcome challenges. It also includes the perspectives of the programme director of a third-sector organisation and 3 Blackpool community champions. The case study has been compiled from a series of in-depth interviews. While there may be themes common to other local authorities, findings may not be generalisable: each local area has its own blend of challenges.

The following themes emerged from our in-depth interviews.

Transience and temporary accommodation

According to interviewees, the high rates of transience and temporary accommodation have constituted important barriers to the effective rollout of the testing and vaccination programmes. They have made it difficult to locate residents in temporary housing, efficiently run the local test and trace system, and create a sense of community cohesion.

Houses of multiple occupation (HMOs) have been described as particularly problematic due to the high number of unregistered HMOs and the severe level of deprivation commonly found among occupants.

Apathy and disengagement

Widespread apathy and disengagement among disadvantaged groups, and more particularly within those living in HMOs, was a prominent theme in the interviews. Members of the public health team and Community Champions reported that many Blackpool residents were withdrawn from society and completely disengaged from public health initiatives.

Confusion and lack of awareness around weekly testing

Interviewees reported that a lack of awareness or understanding as one of the barriers to increasing uptake of asymptomatic testing in the community. Some residents were reportedly unclear about the purpose of taking regular lateral flow tests (LFTs), and/or where to collect LFTs.

Lack of engagement from large employers

Blackpool public health team reported having worked closely with local employers to promote asymptomatic testing among employees. According to interview participants, they had found the workplace to be an effective setting to engage migrant workers and younger or disengaged groups. However, the local authority had faced some reluctance from large private organisations concerned about identifying positive cases and losing part of their workforce as a result.

Close collaboration with Blackpool voluntary community and faith sector

The close collaboration between the public health team and Voluntary Community and Faith Sector (VCFS) organisations was described as having been an essential feature of the response in Blackpool to the pandemic. All interviewees emphasised the key role played by the voluntary community and faith sector in delivering the national testing and vaccination schemes. They reported that the £211,690 grant received in January 2021, as part of the Community Champions Programme, had contributed to supporting vulnerable groups with a variety of needs related to testing and self-isolation.

A localised approach drawing on available assets

Interviewees emphasised the importance of a localised approach to supporting testing and vaccination in Blackpool. A localised approach involves using local assets including VCFS, police, fire and rescue teams and other organisations in the community; offering pragmatic support to HMO tenants through the local network; and operating a local test and trace system that complements the national scheme.

Tailored communication

According to interview data, the local authority’s efforts towards creating tailored communication was driven by 2 principles: simplifying messaging and emphasising the role of local government as a support provider. It was reported that this tailored approach led to many residents being more receptive towards information on coronavirus (COVID-19) testing.

Introduction

Blackpool is a large town and seaside resort in Lancashire. It has a high level of deprivation, an older population and a high level of transience. These characteristics have created a singular set of challenges in managing the COVID-19 pandemic. In this study, we explore the experiences of the Blackpool public health team, a third-sector organisation and Community Champions to develop and promote COVID-19 testing and vaccination. We also describe some of the local initiatives implemented to address some of the reported challenges.

This report sets the research context including Blackpool’s socio-demographic profile, COVID-19 positivity and death rates, as well as test and vaccine uptake numbers. It describes the barriers to testing and vaccination reported by Blackpool public health team and the Programme Director of a large third-sector organisation. The report then outlines the local responses put in place to address these barriers. Finally, we conclude this paper with some future considerations.

Methodology

This study draws on semi-structured interviews, which were conducted in May and June 2021, with 8 stakeholders who were:

- 4 members of Blackpool public health team cited as Participants A, B, C and D

- the programme director of a large VCFS organisation cited as Participant E

- 3 community champions cited as Participants F, G and H

Each interview was conducted remotely, was audio-recorded and lasted between 50 and 60 minutes. Thematic analysis was applied to all interviews in order to identify prominent themes and findings were submitted to interview participants to maintain quality and minimise interviewer bias. In addition to qualitative data, quantitative evidence from NHS Test and Trace data management systems was used to determine levels of testing in Blackpool and describe the local context.

This study was conducted in line with government social research guidance (1) and research participants provided informed consent before data collection. This report was reviewed and approved by the research participants.

The report was completed in July 2021.

Study limitations

The focus of the qualitative element of this report is community testing, and as such, it does not address testing or vaccination in institutional settings such as care homes and hospitals – neither of staff nor residents or patients.

While much can be learned from a case study, the generalisability of findings from one locality is limited (2). This research draws on a small sample of participants who shared their personal experiences of developing and managing testing and vaccination services within their local authority.

This study focuses on barriers to testing and vaccination, as reported by interviewees. It also presents the experiences of Community Champions, who have been supporting vulnerable residents during the pandemic, but does not involve any direct reporting from disadvantaged groups in Blackpool. With these limitations in mind, the purpose of the case study is not to generalise the results to the wider population. Instead, it provides a description of some the challenges faced by local authorities, charity organisations and volunteers during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Finally, another limitation of this study is the lack of data on hidden groups such as occupants of unregistered HMOs or temporary migrant workers. As a result, these groups are not included in some calculations, such as positivity rates.

We would draw your attention to a postscript to this case study, provided in May 2023 by the Director of Public Health for Blackpool. This can be found in the Annex to this report.

Context

Blackpool socio-demographic and equality profiles

An older population

Blackpool is a unitary authority in the county of Lancashire, in North West England. It has a population of 140,000 and an area of 35 square kilometres. Table 1 gives the age breakdown of Blackpool’s population. As in other coastal authorities, older people (those aged over 65 years) account for a greater proportion of Blackpool’s population than is observed at national level. People aged 17 years and under represent 21% of the population (3).

Table 1: Blackpool population age groups (2019)

| Age group | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 0 to 17 years | 21% |

| 18 to 64 years | 58% |

| 65-plus years | 21% |

Source: Lancashire.gov.uk

A low level of ethnic diversity

Table 2 gives the ethnicity of Blackpool’s population. The majority of Blackpool residents are of White ethnicity, with minority ethnic groups estimated to make up just 3% of the population, compared with 15% for all of England and Wales (4).

Table 2: Ethnic groups in Blackpool (2011)

| Ethnic group | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White | 97% |

| Asian | 2% |

| Mixed/multiple | 1% |

| Black | 0.2% |

| Arab | 0.2% |

| Other ethnic group | 0.2% |

Source: 2011 Census.

The total does not equal 100% due to rounding.

A high level of transience

Population turnover in Blackpool is high. Transience – the movement of people with a high degree of residential mobility, which frequently accompanies a chaotic lifestyle – has been recognised in Blackpool for a long time (5). Population statistics (6) show that some areas in Blackpool have extremely high levels of population inflow and outflow. For example, Blackpool South Shore has a population inflow rate of 193 per 1,000 population. The 2011 census revealed that, using commonly accepted criteria, 11% of the population in Blackpool could be classified as transient. Further evidence from housing and benefits data suggests that within the first 6 months of settlement, 55% of Blackpool’s transient residents are likely to move again (4). The section on barriers that the high level of transience and the socio-economic circumstances of transient residents pose for test and trace services.

Housing

Transience in Blackpool is closely related with a high rate of temporary accommodation and HMOs. The market for poor quality private rented sector properties is fuelled by former hotel accommodation reaching the end of its life, when it is then converted with or without permission to privately rented small flats and bedsits. There are approximately 3,000 known HMOs in the authority (7).

Economy

As a major tourist destination, Blackpool has a lower than average rate of employee jobs in the manufacturing sector and a much greater reliance on service sector employment. It is well-represented in the employment sector of arts, entertainment, recreation and other services (3). As a result, Blackpool has a high proportion of seasonal workers employed in the tourism and hospitality industries. The number of Eastern Europeans, mostly Polish immigrants, working in the resort and surrounding area has grown in recent years (8).

Deprivation

The 2019 Indices of Multiple Deprivation revealed that Blackpool was ranked the most deprived area out of 317 districts and unitary authorities in England (9). Forty-two percent of its lower layer super output areas (LSOAs) were among the 10% most deprived in the country, and 8 of these were also in the top 10 (3). The unitary authority also has a high rate of child poverty with 35% of children in Blackpool living in poverty (nearly half in wards with the worst rates of deprivation), compared with 21% of all children in England.

Unemployment (those actively seeking employment but currently not in a job) is around 8% in Blackpool. This is higher than England (6%) and the North West (6%). The Blackpool working-age population claiming employment and support allowance or incapacity benefit is 13%, compared to 8% for the North West region, and 6% for England (10). Blackpool also has more residents with no qualifications (31%) than the national average (22%) (4)

Public health

The high level of poverty in Blackpool is reflected in the public health of this authority. According to the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities’ annual Local Authority Health Profiles (11), residents in Blackpool have a lower life expectancy than the national average. In the poorest parts, life expectancy is 12.3 years lower than the average for men and 10.1 years lower for women.

Behavioural risk factors for Blackpool (2018 Local Authority Health Profile) include high rates of alcohol-related harm hospital admissions. In Blackpool alone, the hospital admission rate for alcohol-related conditions is 1,015 per 100,000 per year, compared with 663 for England (3). In addition, estimated levels of excess weight in adults (aged 18 and over), smoking prevalence in adults (aged 18 and over) and physically active adults (aged 19 and over) are worse than the England average. In 2019, the suicide rate in Blackpool was well above the country average, with 14 per 100,000 compared to 10 per 100,000 for England (12).

Vaccination and testing data for Blackpool

Vaccination coverage

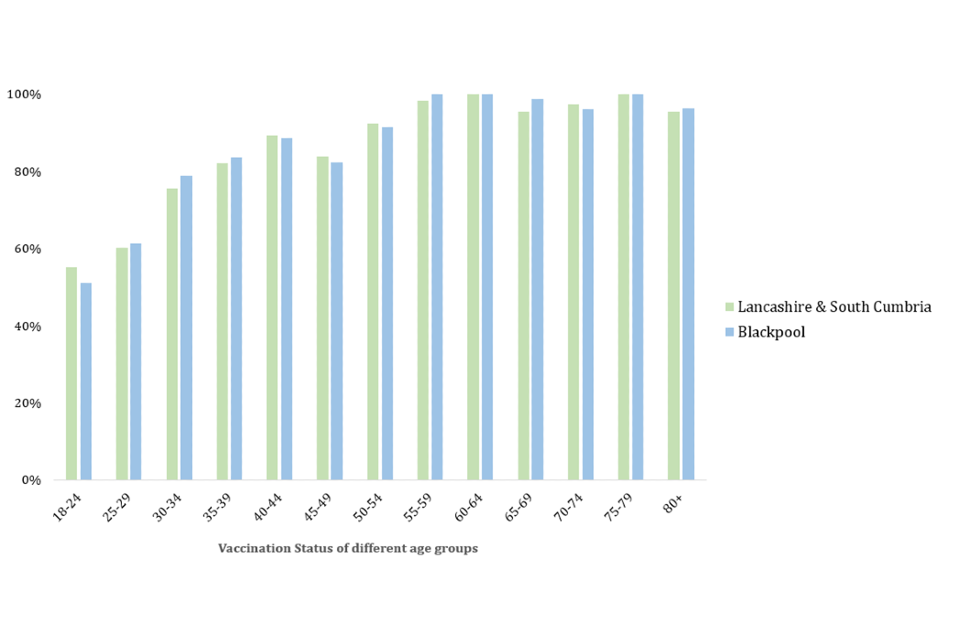

As of 28 June 2021, Blackpool achieved good vaccination uptake, with 95,534 people having received one dose and 77,279 people having received 2 doses. Figure 1 below shows the percentage of people, by age group, who have received at least one dose of vaccination in Blackpool and in Lancashire and South Cumbria. The figure is a column chart, the X-axis representing 13 different age ranges and the Y-axis representing the percentage range from 0 to 100. The green columns represent data derived from people living in Lancashire and South Cumbria and the blue columns represent data derived from people living in Blackpool. Vaccine uptake in both areas is about 55% in the 18 to 24 age range and steadily increases to mid to high 90% in the 55 to 59 age range and remains high for all later age groups.

Figure 1: Percentage of people in Lancashire and South Cumbria and Blackpool who have had at least one dose of vaccination

Source: NHS England

Test uptake

As table 3 illustrates, the proportion of people who had taken a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test in Blackpool from April 2020 until 26 May 2021 was slightly lower than the test uptake for the North West region (42% versus 47% of the population).

Table 3: Overall PCR test uptake for Blackpool and North West from 1 April 2020 to 26 May 2021 – number of individuals tested

| Blackpool | North West | |

|---|---|---|

| Tested | 58,501 | 3,363,397 |

| Population | 140,000 | 7,224,000 |

| Proportion tested | 42% | 47% |

Source: NHS Test and Trace Data Management System

Table 4: PCR test uptake for Blackpool and North West from 1 January 2021 until 26 May 2021 – number of individuals tested

| Blackpool | North West | |

|---|---|---|

| Tested | 35,095 | 2,012,177 |

| Population | 140,000 | 7,224,000 |

| Proportion tested | 25% | 28% |

Source: NHS Test and Trace Data Management System

Although the uptake in PCR testing in both regions was much reduced between 1 January to 26 May 2021 (Table 4), the number of tests administered per capita was higher in Blackpool (Table 5). This indicates a higher rate of multiple testing of some Blackpool residents.

Table 5: PCR test uptake from 1 January 2021 until 26 May 2021 – number of tests

| Blackpool | North West | |

|---|---|---|

| Tested | 114,339 | 4,794,816 |

| Population | 140,000 | 7,224,000 |

| Number of tests per capita | 0.82 | 0.66 |

Source: NHS Test and Trace Data Management System

Similar to PCR uptake, lateral flow test (LFT) rates show that, while the number of individuals tested is at the same level in Blackpool and North West (Table 6), the number of tests administered is higher in Blackpool (Table 7). This, again, indicates a higher rate of repeated testing in Blackpool.

Table 6: LFT uptake from 1 January 2021 to 26 May 2021 – number of individuals tested

| Blackpool | North West | |

|---|---|---|

| Tested | 38,970 | 1,998,432 |

| Population | 140,000 | 7,224,000 |

| Proportion tested | 28% | 28% |

Source: NHS Test and Trace Data Management System

Table 7: LFT uptake from 1 January 2021 to 26 May 2021 – number of tests

| Blackpool | North West | |

|---|---|---|

| Tested | 317,849 | 14,297,177 |

| Population | 140,000 | 7,224,000 |

| Number of tests per capita | 2.3 | 2.0 |

Source: NHS Test and Trace Data Management System

Note: the provision for asymptomatic testing of staff at Blackpool Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust was via a technology called Loop Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) which would not have been included in either LFT or PCR testing numbers via NHS Test and Trace Data Management System. At the time of the study, the Universal Testing Offer was in place and NHS staff using LFTs may have been accessing testing via this route. The implications of this are that when comparing testing rates between geographies there may have been an impact on the calculation of testing rates (both proportion of individuals participating in testing and number of tests per person). Given the intensity of testing in care homes, and the relatively low number of care homes in the Blackpool local authority area, this may also explain why slightly lower rates of testing were observed via the NHS Test and Trace testing programme.

Reported barriers to developing testing and vaccination programmes

Transience and temporary accommodation

Blackpool has a substantial transient population, with approximately 8,000 people moving into and out of the area over the course of 2015 (13). These include people moving from other parts of the country to access low-cost housing, seasonal workers, especially from Eastern Europe, and an estimated 500 Gypsy families, according to Blackpool public health officials.

The high rate of transience results in high levels of movement between properties within Blackpool, especially in the private rented sector. The local authority has a large proportion of poor quality privately rented housing, often converted from former guest houses. These have led to intense concentrations of deprivation, and an environment that contributes to lack of opportunity and poor health. Participant B described the severity of the housing situation as follows:

We have the largest tourist economy in the country. Huge stock of ex-holiday homes, ex-bed and breakfasts, converted into very poor accommodations. It’s really shocking. It was never built to house people all year round. We have this problem. Bigger here than anywhere else in the country.

Interviewees reported that the high level of low-quality temporary accommodation has been one of the main challenges of rolling out testing and vaccination programmes in Blackpool. They explained that a high level of transience not only makes it extremely difficult to create a sense of community cohesion, but also hinders their ability to locate residents in temporary housing and run the local test and trace system as efficiently as they could.

Interviewees reported that problems associated with inadequate and poor-quality HMOs were identified before the pandemic but that they have since been exacerbated.

Regarding HMOs, that was recognised way before COVID. We’ve looked at the uptake in these areas, we know the uptake falls by age, we know it’s lower for males. It’s not a feeling. We know there’s a problem in HMOs.

(Participant B)

According to interviewees, one of the main challenges of reaching residents living in HMOs has been the high proportion of unlicensed HMOs and unregistered HMO residents. As 2 interviewees said:

We have a lot of people not registered and living in HMOs. We can’t know what our rates are if we don’t know the actual numbers. Landlords have been using terms such as students’ accommodations, but they’re not.

(Participant C)

There’s a lot of sofa surfing and things like that. Informal arrangements. About demographics, we actually don’t know since many people aren’t registered with GP practices. We’re suspecting it’s more than in other places.

(Participant B)

Interviewees’ description of a sizeable hidden population in Blackpool indicates that the number of positive cases in the authority may be higher than the official figures. Another reported obstacle of engaging HMO occupants was that many are vulnerable individuals living in precarious conditions.

It’s not a student population in HMOs. They’re older than that. People who have been around, they’ve got drug problems, drifted around, ended up in Blackpool because it’s cheap accommodation here, just go to the pub and live on the social security.

(Participant C)

Members of the local public health team concurred that the greatest constraint to rolling out COVID-19 vaccination in HMOs has been the imposition of an age limit. They believed that promoting the vaccine among HMO tenants, while only a proportion of occupants may be in the relevant age bracket, would be ineffective.

The biggest barrier is the vaccine age limit. We’re going to get in there once we get in there, we need to be able to offer it to everybody. The message ‘go get the vaccine if you’re the right age’ is too complicated for our population. It’s either get the vaccine or don’t get the vaccine.

(Participant C)

There’s no point going to an HMO where 6 people live and say “Three of you, you can get it, and the rest of you can’t have it”.

(Participant B)

Apathy and disengagement

A prominent theme in interview data was reported apathy and disengagement around COVID-19 testing and vaccination commonly found within some disadvantaged groups, and more specifically among HMO occupants. Interviewees described some Blackpool residents as showing low levels of either health literacy or engagement. One of the interviewees described the phenomenon as follows:

We’ve done segmentation work before. We know we have a really large population that are just not engaged with their own health and well-being in general. If they fell ill, they wouldn’t do anything about it.

(Participant B)

Furthermore, members of the public health team highlighted that the town includes a large number of residents who are withdrawn from society and, as a result, disengaged from public health initiatives.

The fatalistic and disengaged are a large chunk of people who come to Blackpool and live in HMOs, aren’t really interested in the wider world. It doesn’t matter what the message is, they aren’t interested.

(Participant C)

Confusion and lack of awareness about regular asymptomatic testing

One of the barriers to asymptomatic testing described in the interviews is a lack of awareness, as well as some level of confusion, about regular symptomatic testing. Some residents are reportedly unclear about the purpose of taking regular LFTs and/or where to collect LFTs.

The comms to get tested twice a week hasn’t really reached anyone anywhere. There’s a large part of the community that seems unaware that they can get tests from the chemist, et cetera…There seems to be a void in the comms.

(Participant B)

Lack of data on self-collect or home testing uptake

Members of the public health team said that they had detailed data on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) uptake, but were not well sighted on asymptomatic home testing.

For some things we have a huge amount of details. Because we do our own contact tracing. We’ve got good information on the symptomatic PCR testing going on. In terms of positive and negative tests. The bit we’re unsure is the LFT routine, we don’t have as much detail there.

(Participant B)

Interviewees described 2 reasons for lack of traceability of LFTs being a barrier to promoting regular asymptomatic testing. First, the local authority is unable to identify the final recipients of collected LFTs unless self-tests are associated with a given official structure such as a school, a workplace or medical setting.

Whether it goes to all the right places and engaging all the right people…We don’t have that level of detail. Especially with the testing at home. When it’s attached to a certain setting: school, NHS centre, et cetera…, we do have this data. Otherwise, we don’t know

(Participant A)

Secondly, although the Blackpool public health team was able keep track of the number of LFTs collected from the various available outlets, they reported a gap in the data where residents do not register their results online.

We know how many packs they’re taking from us but other than that we don’t know the results.

(Participant C)

Interviewees expected that many Blackpool residents would not register negative LFT results due to the perceived complexity of the online registration process, which they described as ‘too difficult’ and ‘very long-winded’. On the other hand, they believed that positive LFTs do get reported and are followed by a confirmatory PCR test.

Lack of engagement from large employers

Interviewees described large private organisations’ reluctance to support testing in the workplace as a ‘missed opportunity’ (Participant A). While local employers had reportedly embraced the local authority’s campaign for regular testing of asymptomatic employees, national companies in Blackpool had not engaged. According to interviewees, large companies’ disengagement was due to trade unions’ opposition to workplace testing schemes, as well as employers’ concerns about identifying positive asymptomatic cases and losing part of their workforce as a result.

In the workplace, we have an issue with the largest national employers. We can’t get it in supermarkets, we couldn’t get it in [organisation name redacted] where we have 3,500 people in Blackpool. Because of the trade unions and this not being part of their policy.

(Participant C)

Local responses addressing barriers to testing and vaccination

Close collaboration with Blackpool VCFS

In response to COVID-19, Blackpool public health team reported having established close collaboration with the voluntary community and faith sector (VCFS) which were already providing services to the community pre-pandemic. One aspect of the cooperation between the local authority and VCFS consisted of fortnightly briefings during which the council, Blackpool public health and third-sector organisations discussed the latest official guidance, local priorities and barriers or concerns experienced by the community. Interviewees spoke positively about the collaboration:

The council’s approach was key. They very quickly created the infrastructure to bring together the third sector. Council pulled together the infrastructure of the third sector and did it on a geographical basis, so it is accessible equally. The relationship between third sector and local authority is much better than before the pandemic. Having access to the [director of public health] on a regular basis has made a great difference.

(Participant E)

There has traditionally been a third sector-local authority split. Because local authorities used to provide funding. In working together, we’ve proven that we could achieve so much more.

(Participant D)

In January 2021, Blackpool Council received a £211,690 grant from central Government through the Community Champions Programme. This funding has contributed to supporting the work of volunteers who have offered vulnerable groups assistance with a variety of needs related to testing and self-isolation. Interviewees reported that Community Champions funding was split among 9 organisations in key areas and ‘has made a significant difference’ (Participant E). Community Champions funds were used to provide VCFS organisations with physical resources, including food parcels, to support vulnerable residents.

Community Champions’ activities have also been supported by the creation of the Corona Kindness Hub whose goal has been to provide a single point of contact for residents in need of assistance during the pandemic. The hub is staffed with over 100 approved volunteers who have intimate knowledge of their community and how to engage it. In order to minimise negative socio-economic impacts of self-isolation, the Corona Kindness Hub has helped disadvantaged Blackpool residents by providing a wide breadth of support, including help to obtain food, health care and medication; with welfare, mental health and loneliness; help for someone they care for; with utilities and bills, and around debt or benefits (including claiming Statutory Sick Pay).

According to interview data, another important role of VCFS and Community Champions has been to disseminate public health messages and tackle any misinformation from the early stage of the pandemic.

Misinformation isn’t really an issue because it was addressed by third sector organisations very early on. Digital comms have been useful to address that.

(Participant E)

Members of the public health team described VCFS as an invaluable asset to support vulnerable groups with testing, self-isolation and vaccination. They also explained that close collaboration with VCFS is aligned with the local authority’s effort to adopt a localised approach drawing on community resources.

A localised approach drawing on available assets

A prominent theme that emerged from interviews was the importance of a localised or ‘geographical’ (Participant E) approach to supporting testing and vaccination in Blackpool.

We have close neighbourhoods in Blackpool. It is not diverse in terms of its population. People identify with the estate or the area they live in. We look at the geographical split and trusted organisations within those geographies.

(Participant E)

As described in the previous section, the VCFS has been a crucial asset for Blackpool Council and the public health team during the pandemic. Interviewees highlighted the importance of other local resources, including the police, fire and rescue teams and ‘high profile people in the community such as football club managers’.

The further link to the public sector that we’ve found very useful is linking with the local police teams. To identify vulnerable people. I don’t see that often in other towns. The policing teams are integrated into a lot of the buildings that we manage. They are physically accessible. It’s easy to pick up a conversation with the Police Community Support Officer (PCSO).

(Participant E)

Pragmatic support to HMO tenants through the local network

HMO occupants have been a particularly underserved group when promoting testing and vaccination. As a response, the public health team has tapped into local networks to deliver support to this group of residents.

We use the third sector, council staff and housing associations. Anybody that has these connections with individuals in those properties.

(Participant A)

Interviewees also characterised their support to HMOs as being very ‘hands-on’ (Participant C). Their pragmatic approach consists of “go[ing] in HMOs with an iPad and book vaccination slots with them [because] it needs to be done on the spot”. (Participant C)

Local test and trace system

Blackpool Council has also developed a local contact tracing system which interviewees describe as highly efficient.

The local test and trace has worked very well and we would hate to lose that. It would be crazy to lose that now. We can do so much more and engage people in different way than the national system.

(Participant B)

The local test and trace system had the involvement of third VCFS organisations which provided a range of support services to vulnerable residents who needed to self-isolate. An interviewee explained that Blackpool test and trace team ‘use the existing community services to go knock at people’s doors’ (Participant A). In addition, all interviewees reported that face-to-face conversations around testing often led to advice on and support with booking a COVID-19 vaccine.

Contacting residents through the local Test and Trace is an opportunity to make contact with them and talk about other services. It’s having this conversation about the vaccine and booking it with them.

(Participant D)

It all trickles down to where trust lies. When you’re engaging with communities, trust lies with people who are local to you, where you can have that conversation that might open to something else, and that knowledge that, yes, you need to self-isolate, but I didn‘t know that you didn’t have enough food in your house for one week. That’s something a centrally-managed system would never tap into.

(Participant E)

In the interview extracts below, an interview participant summarises the benefits of a localised test and trace service delivered through the joint efforts of the council and VCFS.

With a local network of trusted organisations that have got links in other support areas, you end up not just having someone to self-isolate, but you end up having a conversation that may change their lives. And that’s the benefit of a very localised, joined-up approach because, 1: you will deliver the service better because you know what you’re talking about from a geographical perspective, and 2: you know the networks that exist within your locality. It makes the whole programme just run smoother.

(Participant E)

Produce tailored communication

Interviewees reported that the local authority’s efforts towards creating tailored communication was driven by 2 principles: simplifying messaging and emphasising the role of local government as a support provider.

Simplifying messaging

Interview participants explain that the rationale behind offering simple messaging is to reach ‘a population that is less engaged with literacy than most’ (Participant C). This means adopting ‘a very direct and straightforward’ style (Participant B) and communicating ‘in black and white terms’ (Participant C).

As regards communication on testing, members of Blackpool public health team reported the benefits of diffusing simpler public health messaging related to COVID-19 symptoms.

We have quite good testing figures in Blackpool. The main reason is, we all along said, irrelevant of the symptoms that are being described by central government, if you’re unwell in any way, please go and get tested. If you’ve got a sore throat, just click through and say ‘yes I’ve got symptoms’ and go get a PCR. One of the worse things we could have done was to say: only go if you have a temperature. To say that if you’re unwell in any way, go and get tested, that massively helped.

(Participant D)

As mentioned in the test uptake section, while Blackpool has similar PCR testing rates to the North West region in terms of number of people tested, the local authority has a significantly higher number of tests per capita (82% compared with 66% for North West), indicating that there has been repeat use of PCR by at least some residents. This testing pattern may have been partly shaped by the information approach described in the above interview extract and urging Blackpool residents to adopt a cautious approach.

Nurturing a sense of community

Local communications in Blackpool were produced with the aim of ‘taking the national guidance and the national message and putting it in a community accessible format’ (Participant D). This has required using the voice of residents in information materials, as well as highlighting the benefits of testing and vaccination to the community. The idea of nurturing a sense of community has been at the heart of the ‘Get Blackpool Back’ public health campaign recently launched in the local authority.

Emphasis on support rather than compliance

A prominent theme in interview data is the emphasis on the support provided by the local authority to the community, as opposed to messaging revolving around the need for compliance with COVID-19 regulations. Following this principle, the local authority has articulated its communication related to COVID-19 around ‘engagement and partnership’ with the community (Participant A).

It’s about communication, and support. Not in a sort of scrutiny, we’re coming to watch you kind of way. It’s about we’re here to help you, assist you, keep you safe.

(Participant A)

It’s a different conversation if you start with “Are you ok? What can we do to help?” Just gathering data from people and telling them what not to do doesn’t work when trying to engage people locally.

(Participant B)

Reaching younger, disengaged and transient groups through local employers

As outlined in the first section of this study, Blackpool attracts a large transient population, including seasonal workers in the hospitality and tourism industries. For this reason, the council and public health team have been working closely with local employers to promote testing and vaccination among employees. Following Lancashire’s participation in a central Government pilot for workplace testing, Blackpool Council has continued its collaboration with employers in order to increase testing and vaccine uptake, particularly in the catering industry. According to interviewees, the workplace has revealed to be an effective setting to engage migrant workers and younger or disengaged groups:

They’re coming to work so working with their employers is the most sensible thing to do, working with the hotels, the hospitality. That’s the main route.

(Participant B)

Public protection colleagues worked with hotels because they have a lot of workers coming from Eastern Europe and getting them tested and vaccinated is an issue.

(Participant C)

Conclusion and future considerations for Blackpool

This case study of Blackpool describes the complex set of challenges facing local stakeholders in the rollout of the national testing and vaccination programmes. It also presents some of the measures put in place by Blackpool public health and VCFS to address the needs of the community.

Among the various barriers reported by interviewees, the existence of a large proportion of hidden population found in temporary accommodation and unregistered HMOs was described as particularly problematic. These hidden groups are typically disengaged and withdrawn from society, which calls for targeted interventions through the local authority and local stakeholders. Another salient aspect of Blackpool experience of the COVID-19 pandemic has been the vital role played by the VCFS and the reported efficacy of the Government Community Champions Programme funding. Blackpool public health teams’ close collaboration with the third sector has supported them in developing a hyper-local approach that responds to the particular needs of vulnerable groups.

This research highlights the need for a discussion around the future role of local authorities in managing the pandemic, including the human and financial resources necessary to deliver national public health initiatives.

Annex: postscript from the Director of Public Health for Blackpool

Looking back on this case study, conducted early in the COVID-19 pandemic, an obvious observation is that while it does much to identify problems, it does not does not describe all the many things that we put in place by way of solutions. Throughout, as a local authority and provider of public health services, we engaged wholeheartedly with both our voluntary sector and with local businesses.

The research conducted for this case study, together with other local knowledge and insights, allowed us to organise our resources in a way that we believed would be most effective to support people in Blackpool. By way of example, these are some of the many initiatives that we put in place:

- Localised tailored regular communications through various media channels by our communications team with weekly videos presented by the Director of Public Health.

- Strong support from our local authority finance team to ensure financial support in the form of grants was given speedily.

- Setting up CoronaKindness to support residents that might need support with shopping, medicines and other deliveries whilst self-isolating.

- Advice and practical support to primary and secondary chools on an almost weekly basis during the height of the pandemic.

- A strong Local Authority Outbreak Management function.

- Supporting local agencies with workplace testing and setting up local testing sites.

- Support to businesses through our highly proactive Public Protection Team.

- Taking on Test and Trace functions at a local level at the earliest opportunity and providing a more effective service than the national system.

- Supplementing the NHS vaccination offer with a mobile vaccination offer which continued until early 2023.

Dr Arif Rajpura BSc, MB ChB, MPH, FFPH, MBA, DRCOG, DFFP, PGC (Exec Coaching)

Director of Public Health

Blackpool Council

Number One

Bickerstaffe Square

Blackpool

FY1 3AH

References

1. GSR Professional Guidance Ethical Assurance for Social and Behavioural Research in Government

2. Yin RK. Case study research: Design and methods (Fourth Edition) Thousand Oaks, California: Sage 2009

4. 2011 Census for England and Wales

5. Memorandum by Blackpool Council (CT 47)

6. ONS Mid-Year Population Estimates 2018

7. Blackpool Council Housing Strategy 2018 to 2023

8. Local Economy Baseline for Blackpool: A Report to Blackpool Council

9. English indices of deprivation 2019: technical report

10. ONS UK unemployment figures

11. Office for Health Improvement and Disparities Local Authority Health Profiles