COVID-19 testing in a deprived local authority: Hackney, London

Describes the obstacles experienced by Hackney Council and its public health team in supporting testing, and the local responses implemented to overcome challenges.

A skyline aerial photo of Hackney taken with a drone, by Aero-Scope.co.uk via Wikimedia Commons

Executive summary

This case study describes the obstacles experienced by Hackney Council and public health team in supporting testing, as well as some of the local responses implemented to overcome these challenges.

The following themes emerged.

Coronavirus (COVID-19) testing hesitancy is often linked to the financial and practical impacts of self-isolation.

In an effort to support disadvantaged communities, Hackney Council has established a close cooperation with voluntary and community services. According to interviewees, third sector organisations have been an effective channel to build engagement within the most deprived wards.

Digital exclusion has been identified by Hackney’s public health team as a significant barrier to testing.

Digital exclusion may result from either digital poverty or a lack of technological skills. Local initiatives to tackle digital exclusion have included offering ‘no-appointment’ testing and developing non-digital channels, such as telephone helplines.

A persistent lack of understanding of COVID-19 transmission and the benefits of testing has been described as one of the difficulties experienced by Hackney Council in promoting testing.

Interviewees attributed the lack of understanding or awareness around COVID-19 to low levels of literacy and education, language barriers and untailored communication materials.

Mistrust and disengagement were described as one of the barriers to testing and vaccination among disadvantaged groups.

According to interviewees, an apparent lack of trust in government and official bodies within these groups can result in lack of engagement in local and central authorities’ initiatives. The public health team in Hackney has addressed this issue through collaborating with third sector organisations and the Community Champions, who have played a key role in disseminating information to residents who might not access it through mainstream channels.

Another reported barrier to increasing testing rates was the lack of granular analyses of socio-demographic and test and trace data conducted locally.

This has been described as a hindrance to the effectiveness of testing services in Hackney. A more detailed examination of local data would allow more targeted interventions.

The most salient aspect of Hackney’s response to the pandemic was to establish close cooperation with the third sector.

This helped to reach and engage residents in more deprived areas of the borough.

About this report

Hackney is one of London’s most deprived boroughs (1) and a highly ethnically diverse local authority. In this qualitative study, we explore the challenges faced by Hackney public health team to develop and promote COVID-19 testing. We also describe some of the local initiatives implemented to address identified barriers to testing.

This study is presented as follows: section 2 sets the research context including Hackney’s socio-demographic profile, its level of deprivation, COVID-19 mortality rates and available testing services. Section 3 describes the barriers to testing reported by Hackney public health team during in-depth interviews. Section 4 outlines the local responses put in place to address these barriers. Finally, we conclude this paper with some general recommendations.

In this report, the terms ‘disadvantaged’ and ‘deprived’ are used interchangeably to refer to groups or individuals experiencing socio-economic hardship.

Methodology

This qualitative study draws on in-depth interviews with 4 key members of the Hackney public health team in March and April 2021. Interviewees are cited as Participant A, B, C or D.

Each interview was conducted remotely (via telephone or videoconference), audio-recorded and lasted between 50 and 60 minutes. Prominent themes were identified across the 4 interviews using bottom up thematic analysis. Interviews provided valuable insights into the barriers experienced by stakeholders in the local authority in developing and promoting testing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, we used quantitative evidence from NHS Test and Trace data management systems to determine levels of testing in Hackney and describe the local context.

This study was conducted in line with government social research guidance (2) and research participants provided informed consent before data collection. This report was reviewed and approved by the research participants.

The report was completed in July 2021.

Study limitations

While much can be learned from a case study, findings from one locality are not generalisable (3). This research draws on a small sample of participants who shared their personal experiences of developing and managing testing services within their local authority.

This study focuses on barriers to testing as reported by the local authority and does not involve any direct insight into the experiences of residents.

With these limitations in mind, the purpose of the present case study is not to generalise results to the wider population. Instead, it highlights some of the potential challenges faced by local authorities during the pandemic.

Hackney socio-demographic and equality profile

This section describes Hackney’s demographic and socio-economic profile and provides data on COVID-19 mortality rates and testing services.

A young population

The London borough of Hackney has an estimated total population of 281,000 residents with an almost 50:50 male to female ratio. It has a relatively young population with a quarter of its residents under 20. The proportion of people between 20 and 39 years is 40% and those aged over 55 make up only 16% of the population. The median age in Hackney is 32, compared to 35.8 in London and 40.4 in the UK overall (4).

The sixth most ethnically diverse borough in London

Hackney is a culturally diverse area, with well-established Caribbean, Turkish, Kurdish, Vietnamese and strictly orthodox Charedi Jewish communities. A large group of more recently arrived residents include people from Europe, North and South America, Australasia and African countries (5).

The borough’s increasing diversity currently marks it out as the sixth most ethnically diverse borough in London. Table 1 gives the proportion of Hackney’s population in different ethnic groups, using data from the 2011 census.

Hackney’s White British ethnic group represents 36% of its total population, compared with 45% for London and 80% for England. The second largest ethnic group in Hackney is the African/Caribbean/Black British group (23%), among which Africans – more particularly, the Nigerian community – are the largest group within this category. Kings Park and Chatham wards both fall within the top 20 wards in England with the highest numbers of Nigerian residents. The third largest ethnic group in Hackney is Other White (16%) which has shown a 60% increase since 2001. Hackney has large and long-established Turkish, Kurdish and Turkish-Cypriot communities who fall within the Other White ethnic category and total 6% of the population. Other White residents also include the second largest Charedi Jewish community in Europe, as well as a large proportion of people from Eastern European countries, particularly Poland.

Table 1. Ethnic groups in Hackney

| Ethnic group | % |

|---|---|

| White English/Welsh/ Scottish/Northern Irish/British | 36.2% |

| White: Other White | 16.2% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/ Black British: African | 11.4% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/ Black British: Caribbean | 7.8% |

| Other ethnic group: Any other ethnic group | 4.6% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/ Black British: Other Black | 3.9% |

| Asian/Asian British: Indian | 3.1% |

| Asian/Asian British: Other Asian | 2.7% |

| Asian/Asian British: Bangladeshi | 2.5% |

| White: Irish | 2.1% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black Caribbean | 2.0% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: Other Mixed | 2.0% |

| Asian/Asian British: Chinese | 1.4% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Black African | 1.2% |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic group: White and Asian | 1.2% |

| Asian/Asian British: Pakistani | 0.8% |

| Other ethnic group: Arab | 0.7% |

| White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller | 0.2% |

Source: 2011 census

Religious profile

Thirty-nine percent of Hackney’s residents are Christian. This is a lower percentage than the figures for London (48%) and England (59%). Hackney has a higher proportion of people of the Jewish and Muslim faiths than London and England.

Level of deprivation

The 2019 Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) (6) shows that Hackney is the London borough with the highest proportion of lower super output areas (LSOAs) within the most deprived 10% nationally (11% of its LSOAs). It is also the 78th most deprived local authority out of 339 in England. Hackney ranks particularly highly on the child poverty index (41%, the third highest in London), as well as poverty and isolation among older people (7).

The job density in Hackney – that is, the ratio of total jobs to population aged 16 to 64 – is 0.77, compared to 1.03 for London and 0.87 for the UK (8). In March 2020, 10% of Hackney’s working age population claimed out-of-work benefits, the highest rate among all London boroughs. The number of out of work benefit claimants in Hackney is particularly high and there is a high level of in-work poverty. Hackney also has the highest rate of working-age adults who have no qualifications: 11% compared to 7% for London overall.

In addition to a high level of unemployment, the city has a difficult housing market, with rent for an average one-bedroom dwelling in Hackney standing at 61% of median pre-tax pay, one of the highest ratios in London. The borough also has one of the highest rates of households in temporary accommodation (26.8 households per 1,000 compared to an average of 16.6 across London) (9).

The high level of deprivation in Hackney is reflected in a lower life expectancy than the London average, especially for males, whose average life expectancy at birth is 78.8 years compared to 80.5 for the whole of London (5).

Wealth disparities within Hackney

Like other boroughs across East London, Hackney has undergone a process of gentrification (10) – the influx of more affluent people and businesses resulting in an increase in property values and the displacement of earlier, usually poorer residents. Gentrification is a factor in disparities in the local authority and has impacted local community dynamics by creating concentrations of more established, poorer, and mostly ethnic minority groups (notably Caribbean, Vietnamese, Charedi Jewish, Turkish/Kurdish), particularly in south and west Hackney. The more recent demographic includes an incoming of wealthier middle class able to afford the private housing market. The disparities, perceived by some residents as having created ‘2 Hackneys’, have led to increasing tensions which were further exacerbated over the course of the lockdown, as ethnic minorities were disproportionately affected by COVID-19 (11).

A total of 16 neighbourhoods in Hackney are among the 10% most deprived in England, including, among others, Wick Streets bordering on the River Lea, parts of Clapton, Manor House and Hoxton. More affluent areas in Hackney include Haggerston, Victoria, Dalston, Lordship and Hackney Central where average private property prices have passed the £500,000 mark. Wealth disparities within the borough were reflected in the COVID-19 prevalence rates during the first and second waves of infections, more deprived areas having been more severely hit.

COVID-19 in Hackney

COVID-19 mortality and positivity rates in Hackney

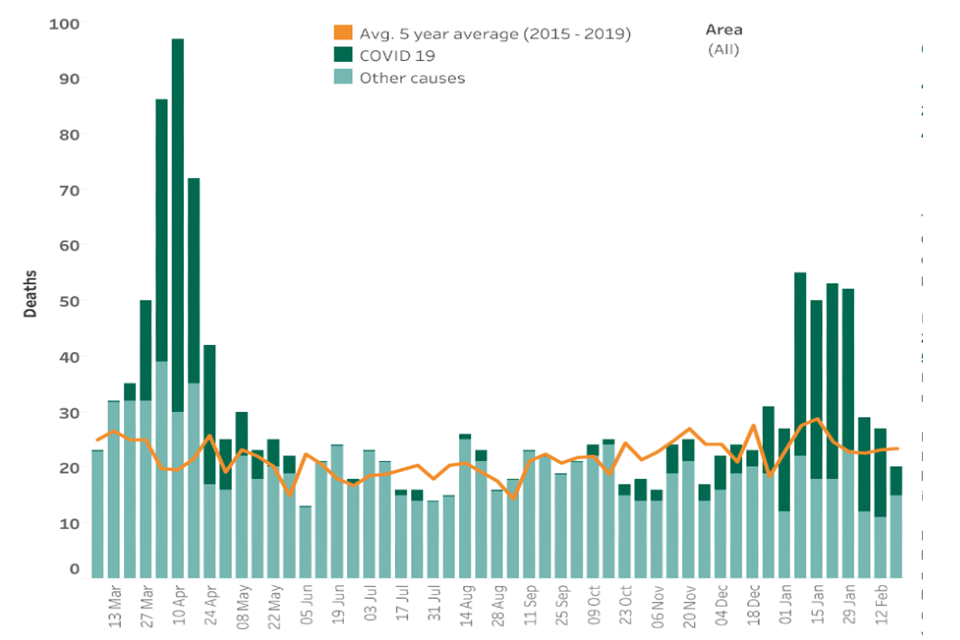

Hackney was especially hard-hit by high COVID-19 mortality rates at the onset of the pandemic (ranked third of all local authorities in England between 1 March and 31 April 2020) (14). Comparison with the 5-year average mortality rate for City and Hackney (see Figure 1) provides an indication of how the pandemic has affected mortality locally. The figure is a column chart with the Y-axis presenting the time period between March 2020 and February 2021 and the X-axis representing the number of deaths. The light green columns represent deaths arising from causes other than COVID-19, the dark green columns represent deaths due to COVID-19, the orange line represents the average deaths measured between 2015 and 2019. After a sharp increase in COVID-19 related deaths between March and mid-May 2020, mortality rates went back to levels similar to the number of deaths in Hackney over the past 5 years. In January 2021, the borough experienced a second wave of COVID-19 deaths, which was lower than the peak in April 2020.

Figure 1. Mortality rates in Hackney and City between March 2020 and February 2021

Source: ONS

Intra-borough variation of COVID-19 positivity rates

Data on prevalence of COVID-19 during the highest peak of the first wave of infections, week of 7 April 2020, and during the second wave, November 2020, shows differences across wards, with the highest number of cases in Brownswood, Homerton, and Hoxton West. These 3 wards have a higher proportion of residents in social housing, lower levels of qualifications and a more ethnically diverse population, relative to the borough averages. Generally, higher positivity rates have coincided with higher levels of deprivation.

Available COVID-19 testing services in Hackney

COVID-19 testing capacity has been increasing consistently across the UK since March 2020. The first symptomatic test centre located in Hackney was launched in September 2020 and testing capacity in the borough was built up gradually.

Hackney Council has also been running local test and trace operations complementing the national system. Drawing on local data, Hackney Council staff have been offering guidance to local residents regarding contact tracing and self-isolation (15).

Reported barriers to testing in Hackney

This section describes some of the challenges in increasing and promoting COVID-19 testing in the local authority. According to interviewees, the high level of deprivation and the multitude of ethnic backgrounds found in parts of Hackney contributed to shaping the borough’s experience and management of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Inability to self-isolate if tested positive - financial and practical impact of self-isolation

Interviewees reported that the main barrier to testing within disadvantaged groups was the concern of having to self-isolate following a positive COVID-19 test. Reluctance towards getting tested was, therefore, not directly related to testing itself, but to a range of financial and practical considerations linked to self-isolation. For many disadvantaged residents, self-isolation had a direct impact on remuneration and repeated periods of self-isolation may be a threat to their employment security. Other practical concerns included caring responsibilities for children and older relatives.

It’s not only the financial issues that are the problem. Some people are not going to lose money, but they are concerned that, especially if they’ve been through several periods of self-isolation, if they’ve been someone’s contact, they may be concerned about their job. There are a lot of barriers for people. And there are some other practical issues, like we did a survey recently, and they found out that some people only had 2 days’ worth of food in the house. People had pay as you go gas and electric meters. So, if your gas runs out in the middle of your ten days, you’re supposed to just stay at home in the cold? Or how are you going to go and top it off?

(Participant A)

Self-isolation means people can’t budget because they get universal credit once a month and they can only manage little and often. They can’t ask somebody to go to the shops for them. They don’t have those resources or maybe they feel uncomfortable doing that. So, if they’re told if you take this test, you’ll have to self-isolate for 10 days…

(Participant B)

Lack of awareness of available support from central and local authorities

Where practical support during self-isolation was available from the council, it was noted that residents were not always aware of it. For instance, vulnerable people may not have known about the one-off financial support of £500 for workers who would lose earnings as a result of self-isolation. Moreover, some parents and guardians on a low income may have been unaware that they were also eligible to a £500 payment when taking time off work to provide childcare where their child had to self-isolate.

Participant A described how a lack of understanding of the role of local authorities and the available support network may contribute to residents’ reluctance to getting tested for fear of having to self-isolate:

When they talk to someone from Test and Trace, they ask, “Do you need any help?” and they say, “Yeah,” they put them in touch with their local council. Well, their local council wasn’t going to look after their mother who lives 30 miles away. So, not everyone understands the system well enough to know that they can call other councils or to say to their local council, can you contact that council because their mother is on her own and blah blah do you know what I mean?

(Participant A)

Digital exclusion

Interviewees reported that a large proportion of Hackney residents did not have access to reliable broadband or to a technological device that would allow them to easily book a COVID-19 test or simply look for relevant information on testing. Participant A summed up the challenges faced by digitally excluded groups as follows:

A lot of people in Hackney who, to use the jargon, are in digital poverty, don’t have good access to the internet, or they don’t have a device that would enable them to do the booking very easily. So, a lot of our residents, for example, wouldn’t be at home with broadband. But they might have a smart phone, but then, to do the booking online, how much of their data are they going to have to use to do that? A lot of people also don’t have those all-inclusive plans, they’re on these pay as you go phones and so that actually becomes a very expensive undertaking just to book a test.

(Participant A)

With the rollout of home testing, digital exclusion remains one of the main challenges to increase testing within certain communities:

For example, the Charedi community, really still struggle registering kits. And because of digital divide and their cultural and religious observance, doesn’t include access to the Internet for many people. And there are quite a number of pockets of deprivation in the north of the borough.

(Participant B)

Lack of understanding of COVID-19 transmission and the benefits of testing

A prominent theme across all interviews was a perceived persistent lack of understanding around COVID-19 transmission and the benefits of testing. This was said to remain a significant barrier to testing within deprived areas:

People are struggling to understand why. If you think of the COM-B model*, in health psychology and behavioural insight, you have opportunity, capability and motivation. We have lots of opportunity and capability now. Brilliant. But if people don’t want to use them…

(Participant B)

*The COM-B model proposes that there are 3 components to any behaviour: capability (C), opportunity (O) and motivation (M).

As described by interviewees, lack of understanding may be partly attributed to low literacy, education and English proficiency rates, commonly found in the most deprived areas. One interviewee reported a high level of confusion around the objectives and benefits of rapid testing, and how it can coexist with vaccination.

I think the key element, and this is what I’m banging my head about, it’s basically, we don’t have strong enough comms from central government on rapid testing and getting people to understand why it’s necessary. I was on a call this morning with a colleague and he said I don’t understand why we need to test twice a week. So, I tried to explain the infection curve with the incubation period and level of infectiousness.

(Participant B)

One of the problems we have, at the moment, is that people don’t really get rapid testing. They don’t get why it’s twice a week, they don’t get why if they’ve had the vaccine, they need to do a rapid test. They just don’t get it. It doesn’t matter if we do a 3-page spread in the Hackney Gazette. Some people won’t see it. It’s not penetrating enough.

(Participant B)

Lack of trust and engagement

Lack of trust in central and local authorities has been reported as a noteworthy, although less significant, obstacle to testing in disadvantaged communities.

You’ve got to understand that those structural inequalities are built on years and years of having, of people feeling they can’t trust the government, that they can’t trust any institutions. They’re always marginalised and things are difficult to navigate, whether it is DWP, or trying to get a job, or anything, trying to maintain housing. These are just built in how people relate to you.

(Participant B)

Access to test sites

According to both test uptake data and the interviews, lack of access to test sites was a substantial barrier to testing at the earlier stage of the pandemic. Regional centres requiring substantial road travel from the borough were incompatible with Hackney’s low car ownership rate: only 35% of households in the borough own a car (16). As Participant A said, “When the testing started to develop the more local offer, that was an enormous improvement”.

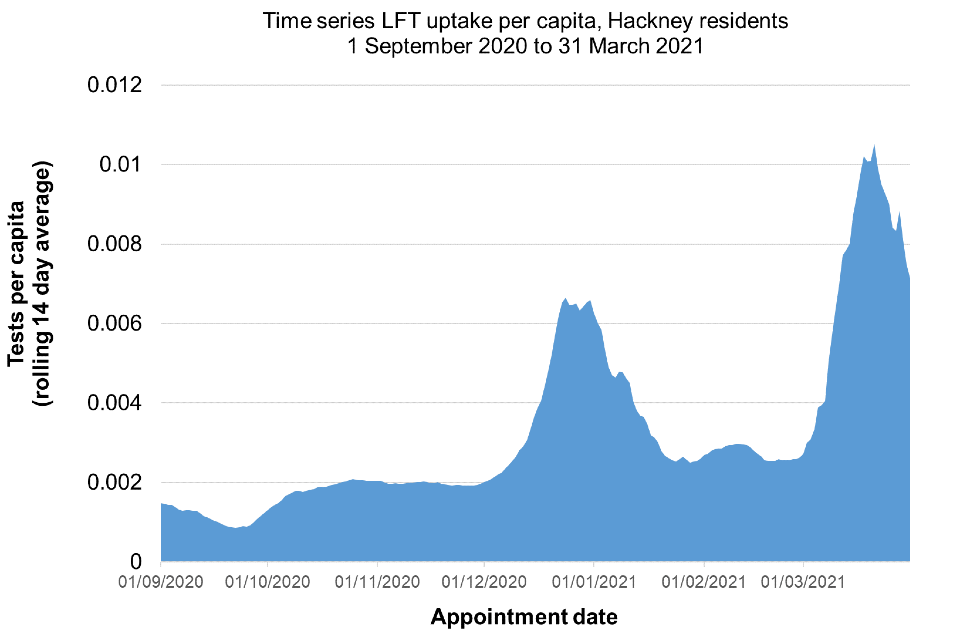

Figure 2 below is a line chart demonstrating uptake of testing over a particular time period with the area below the line coloured in. The X-axis represents the time periods over which appointments for testing were made and the Y-axis represents a measure of the number of tests performed per capita which has been measured over an average of 14 days. The results show a consistent rise in first rapid testing – lateral flow test (LFT) – uptake in Hackney, with a sharper rise since mid-December 2020, coinciding with the appearance of the LFT site in the borough.

Figure 2. Time series LFT uptake per capita, Hackney residents, 1 September 2020 to 31 March 2021

Source: NHS Test and Trace data management system

Lack of suitable spaces for test centres

Finding adequate spaces to establish testing sites, in accordance to standard operating procedures, was challenging for the local authority. While they have endeavoured to set up test centres in locations that would both be most convenient to disadvantaged residents, and address high infection rates, they were not always able to do so. For example, it was essential for the local public health team to set up the third local test site (LTS) in the north of the borough in order to address high COVID-19 prevalence within pockets of deprivation. Sandford Court, located in a housing estate, was selected, as the only available space in the area. The site was apparently unpopular and test uptake remained low.

And the third one (LTS) we put in the north of the borough, in Sandford Court. And the only place we could put it was in right the middle of a housing estate. That was unbelievably bad. And to be fair, it looks awful, and you can totally see why residents felt really upset about that. Basically, it was the only space that we had… eventually, the Hackney Borough Command Centre, did the brilliant job of finding the Arriva Bus Garage that we now use.

(Participant B)

Moreover, they argued that establishing testing in the wrong setting has had a negative impact on residents’ trust in the local authority’s ability to manage the pandemic.

It’s your building block in everything you do. If you mess up and no one can trust you, you’ve completely started off on the wrong foot.

(Participant B)

Sandford Court LTS was later replaced with what was reportedly seen locally to be a more suitable location.

Limited data on communities’ geographical distribution

While local authorities and NHS Test and Trace have made important efforts to strategically set up testing sites to provide an adequate coverage of all communities, their work was reportedly hindered by a lack of granular understanding of the geographical distribution and testing rates of various ethnic and religious communities. For instance, and as previously described, the Other White Other ethnic group in Hackney includes a large Turkish community, the largest Charedi Jewish community in Europe, Gypsy travellers, as well as a high number of residents from Poland and South America. Our interviewees suggested that the existing local data did not allow them to locate these different groups and offer more targeted communication and testing services.

Our data isn’t showing us at ward level, by ethnic group. We might get age, but we don’t get by ethnic group. But also, it’s very broad ethnic groups. That’s so generic. We’ve got at least 12 different African communities, not to mention the South American communities. And then ‘Other’, we’ve got the Charedi Jewish community, the Turkish community, but they’re not the same. How do we know what’s going on with the Gypsy community for example? Where should the pop-up clinic be located? And it’s hard to communicate with people if you don’t know where they are.

(Participant A)

Additionally, interviewees report the absence of detailed local test and trace data that would allow them to identify communities or areas where contact tracing is low.

We input that data into CTAS* to then lose it, and not understanding the wider picture. It’s then difficult for us to target particular groups and have more targeted initiatives. After people get a rapid test, what do they do? What things could we do to make sure that they are more likely to engage with test and trace and share their contacts?

(Participant D)

*CTAS stands for Contact Tracing and Advisory Service, the national IT system for recording information about people who have tested positive for COVID-19 and their contacts.

Local initiatives addressing barriers to testing

In this section, we describe local initiatives implemented by the Hackney public health team in response to the barriers to testing they identified. While we do not provide any evaluation evidence of the effectiveness of these interventions, we report interviewees’ rationale for these measures and their perceptions of their potential impact on the community.

Collaborating with the third sector

Members of the local public health team described the council’s collaboration with Hackney Voluntary and Community Services (HVCS) as key in reaching disadvantaged and disengaged groups in Hackney.

Building trust and engagement through a bottom-up approach

Interviewees described the council’s close cooperation with third sector organisations as an assets-based approach that draws on both local government resources and those of the voluntary and community sector. This bottom-up approach was intended, among other objectives, to support testing among residents in the borough’s most deprived areas. According to Participant B, this has led to a positive ‘ripple effect’ in the community.

In December 2021, COVID-19 funding made available to the local authority allowed the council and public health team to offer grants to third sector organisations and train volunteers on a range of topics including health and safety measures, the availability of testing, how to access testing, the contact tracing system, available support during self-isolation, as well as effective communication and signposting.

As part of their effort to engage with local communities, Hackney Council and public health team launched a Community Champions Programme with the aim of communicating important public health messages to vulnerable residents, through trained volunteers and frontline staff. Participant D described the initial objective of the programme as follows:

In the beginning… it’s very diverse in Hackney, the aim was to reach some of these communities, so the focus was on test and trace. That was our initial insight, that’s why we looked at this. Because people were not understanding it, the test and trace system, didn’t know what it meant, didn’t know, you know, any sort of financial support. There was confusion, if you remember the beginning, especially for our population that are quite far from mainstream services.

(Participant D)

The Community Champion programme was open to a variety of people with an active interest in helping the community.

If you’re a champion, you could be working within a voluntary organisation, you could equally be someone who’s working in the council, or just volunteering in the borough or just have an active interest. So, it’s kind of a combination of these different things under one umbrella.

(Participant D)

As a result of the programme, 110 public health community champions have been trained and deployed across 53 different local VCS organisations, expanding the local authority’s capacity to provide information and support to disadvantaged groups. Each Community Champion covered a given neighbourhood or street, and had, therefore, a deep understanding of the experiences and challenges of local residents. Community Champions were reported to have played a key role in disseminating information on COVID-19 testing to residents who might not have access to information through mainstream channels. This included adults with learning disabilities, residents with a low level of literacy and those who need messaging translated into their native language.

Other interviewees saw the work of the Community Champions as paramount in building relationships of trust with the most vulnerable groups.

People don’t know where to go. So, the Community Champions have become some sort of an independent but trusted source of information. And that’s really important, especially where there are structural inequalities and people are not sure who they can trust.

(Participant B)

Furthermore, interviewees report that Community Champions have provided them with valuable insight into effective methods to communicate with local communities. One interviewee explained how volunteers had been systematically consulted before the production of communication materials.

We check our communication with them before we produce something new. For example, bubbles, people didn’t understand that, especially our Turkish community. So, we made a new poster specifically for this, which we translated into Turkish. And also, our ambition is getting champions to share their resources a bit more.

(Participant C)

Third sector support with self-isolation

HVCS associations and Community Champions had organised an integrative support system that included aid to vulnerable residents during self-isolation.

We have a very strong food network which has been absolutely outstanding in its response, being able to, if somebody literally has no food, they will have a food parcel delivered to them for as long as they need it. It’s been an unbelievable response from our community and voluntary sector.

(Participant B)

All interviewees report that self-isolation support provided by the third sector may have contributed to overcoming some of the practical barriers to testing.

Tackling digital exclusion

Interview participants described the following initiatives put in place to address digital exclusion: walk-in testing, non-digital channels and practical support from Community Champions.

Walk-in testing

Throughout the pandemic, walk-in testing was offered to all test sites during specific time slots. According to one interviewee, walk-in testing was popular among more disadvantaged residents.

We then looked at people who would book online and some people who don’t have digital access. There’s going to be language barriers. People will be quite anxious, people won’t necessarily understand what’s being asked of them, they won’t understand that they were supposed to have booked. But it’s more important that people turn up and get tested.

(Participant B)

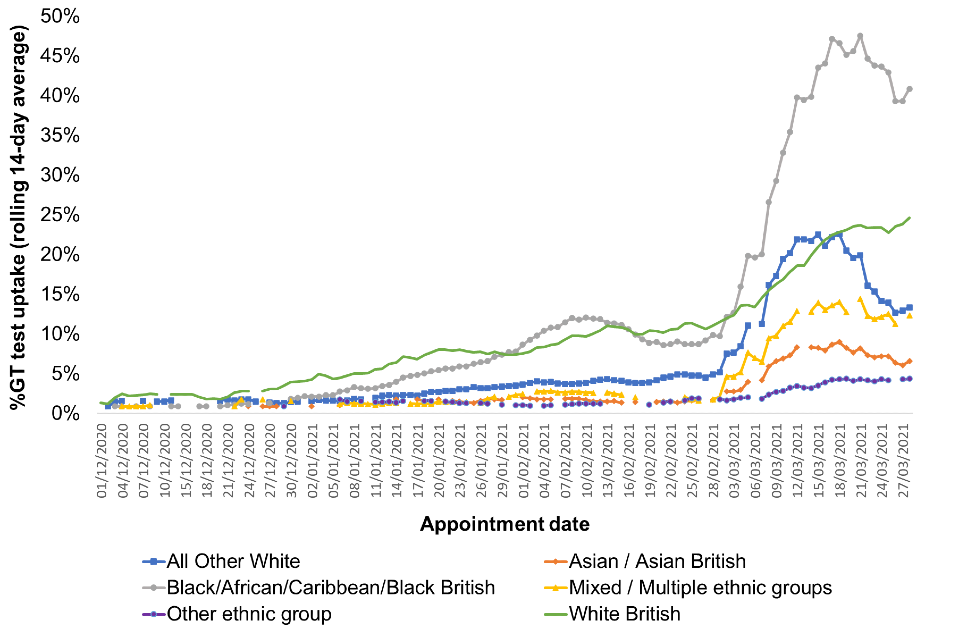

While there has not been a formal impact evaluation of walk-in testing in the area, interviewees believed that it may have contributed to a higher uptake in some of the more deprived and ethnically diverse wards, such as Hackney Wick. Figure 3 demonstrates uptake of LFT by different ethnicities over time. Figure 3 is a line graph with different ethnicities represented by different colours of lines, the X-axis represents the time period over which testing appointments were made and the Y-axis represents uptake over a 14 day rolling average. Between the end of February and late April 2021, in Hackney Wick, LFT uptake increased from 17% to 34% of total LFT testing within the African and Caribbean group, and from 4% to 8% for the Asian group.

Figure 3. Time series LFT uptake by ethnicity for Hackney Wick residents (1 December 2020 to 28 March 2021)

Source: NHS Test and Trace data management system

Non-digital channels (helplines)

The Hackney public health team had also implemented pragmatic solutions to support the Charedi Jewish community, in which use of the internet is limited due to both digital poverty and cultural practice. They set up a helpline linking callers directly to one of the test sites from which test operatives can assist them with registering their tests. The local authority was working towards establishing a local service with the sole purpose of recording test results for residents.

The next step is to set up a local service that will just record results for people. For the Charedi community, it’s still difficult to record results. They can call the number and someone will record the results for them. We need to look at how we’ll do that.

(Participant B)

Practical support from Community Champions

Interviewees reported that another pragmatic solution to deal with digital exclusion had been to support the most disadvantaged residents through the Community Champion Programme. Community Champions had helped vulnerable residents with accessing the NHS Test and Trace website, booking tests on their behalf and acting as a trusted person to receive a notice.

Providing tailored and accessible information

Interviewees said that a significant aspect of Hackney Council’s work to support testing in the community had been the production of information materials adapted to the socio-demographic characteristics of its residents. They believed that better engagement could be achieved through information formats tailored to areas with low literacy rates and high linguistic variety. According to Participant B, a year into the pandemic:

Many people still don’t understand how this virus gets transmitted, and we need to equip people with basics: How does this thing spread? Why do we test twice a week? Getting vaccinated doesn’t mean you don’t need to take a test.

(Participant B)

Rather than providing information on testing as an isolated service, interviewees highlighted the need to adopt an integrated approach to information materials demonstrating “how behaviours are linked, why they are beneficial to them, how they can apply them to their lives.” (Participant B). Interviewees suggested the use of short information videos shareable through social media such as WhatsApp.

If there was like, an animation, saying the ’beat the COVID curve’ or something, and a short video that could be shared on WhatsApp and social media. Some sort of visualisation, that allow people to say, ‘Oh yeah now I understand.

(Participant B)

Things are still quite hard for Community Champions to take the sort of information that’s been nationally produced and share it with the community. We’re not really thinking in the minds of our residents. It’s not a WhatsApp format, it’s in a PDF, it’s long, there’s lots of bullets. Gov.uk guidance is not really accessible to our community. To be honest they won’t look there. If you had a place on the website where you click and say, ‘Right, you can send it to yourself in a WhatsApp,’ that you could share those messages is one way to sort these things out. We need to put ourselves in the shoes of the Champions.

(Participant C)

Interviewees reported that, with the rapid rollout of home and community testing, Hackney Council had directed significant effort into communication around regular asymptomatic testing. They highlighted the importance of communication aids, translated into languages spoken in the local community, and which can be easily distributed through community champions.

Community collect, the home kits are really brilliant. Well done to central Government to work with Innova to adapt their LFTs for home use. There’s a comms campaign coming out soon from central Government about testing, that will be very helpful. The more they can produce, communication aids, in different languages, in different format, that we can share through community champions, social forums.

(Participant B)

For us, the priority now is to make sure they become their own experts, training, swabbing aids, stuff like that […] we now need to support the understanding about rapid testing, about registering the kits, going to the helpline, and so on…

(Participant B)

Conclusion

This case study shares the ‘on the ground’ experience of public health teams and highlights the complexity of being able to reach out to a diverse population, many of whom are vulnerable and at higher risk of adverse health and socioeconomic outcomes of COVID-19. A key learning is the potential value of collaboration with the third sector as a channel to engage disadvantaged and under-represented groups. Hackney Voluntary and Community organisations, alongside Community Champions, were seen to have played an essential role in disseminating public health messages and assisting vulnerable residents with testing and self-isolation. They were seen to have helped combat the issues of digital exclusion, language barriers, and misinformation and to have contributed to building strong relationships with local communities.

The case study highlighted complexities of a local public health response combining COVID-19 vaccination and testing. Participants described the need to provide accessible information on the link between testing and vaccination. They reported a high degree of confusion within the community around the need to continue testing while the COVID-19 vaccine is being rolled out. Their solution was to offer a one-stop information service linking testing, social distancing, self-isolation and vaccination.

References

1. London Councils: Indices of Deprivation 2019

2. GSR Professional Guidance Ethical Assurance for Social and Behavioural Research in Government

3. Yin, RK (2009). ‘Case study research: Design and methods, Fourth Edition.’ Thousand Oaks, California Sage

4. ONS mid-2020 population estimates by local authority

5. Equality and Diversity facts and figures for Hackney

6. English indices of deprivation 2019: technical report

7. Leeser, R (2019) Indices of Deprivation 2019 Initial Analysis

8. Labour market profile, via Nomisweb

9. Social housing in Hackney: Have your say on how we allocate homes and support people in housing need (2020)

10. Lees, Loretta (2019). ‘Gentrification, displacement, and the impacts of council estate renewal in 21st century London’

11. Bear and others. (2020). ‘A Right to Care: The Social Foundations of Recovery from COVID-19.’ London: LSE monograph

12. Data from Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government

13. National Housing Federation

15. ‘Hackney and City step up to boost local test and trace efforts’