Gemma: flying high as a space scientist

The career of our chief scientist of space weather was literally written in the stars.

Gemma Attrill grew up with both her parents being physicists and a picture from the Hubble Space telescope on her bedroom wall. But she was inspired to pursue her pioneering career by a ‘Women into Physics’ event at the University of Sussex while she was studying for her GCSEs.

The People Inside: Gemma Attrill

The event discussed the wide range of careers available to a physics graduate. Gemma was also able to see microscopes powerful enough to measure the width of an electron shell.

She said:

“When you are a school student about to go into sixth form and choose your A-Levels that’s really mind-blowing.

“That was a really key pivotal moment for me actually deciding I wanted to pursue physics professionally.

“I don’t think anyone was more surprised than my parents when I said I wanted to do physics for my A-levels but I certainly received a lot of encouragement and support from them.”

The mum of 2, and army wife, has worked at the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (Dstl) for 13 years. During her time here, she has helped grow the space capability and its international reputation working on numerous important projects.

Gemma talks space weather

She was the UK lead for the Coordinated Ionospheric Reconstruction Cubesat Experiment (CIRCE) space mission which was part of the first ever UK space launch. This involved the launch of 2 satellites the size of a box of cereal, which reached space but a failure of the rocket meant the mission didn’t make it to orbit.

She’s involved in shaping the aims of the next mission, working with both UK and international partners.

She said:

“The most exciting thing about my role is probably the sheer breadth of different people I interact with, the different topic areas and the different systems I encounter.

“I would say I probably spend about 80% of my day outside of my comfort zone. There is always something challenging that needs doing.

“My proudest achievement is probably being the UK lead for the CIRCE satellite mission. It was a real privilege to work with such an amazing team, and be part of the first ever space launch from the UK.”

Gemma, who was once an Air Cadets glider pilot, had planned to pursue a career as an elite fast jet pilot until she was told she needed glasses. This acted as a catalyst for her studying physics at university.

Aurora Borealis

She says she feels grateful as her career path has afforded her the opportunity to travel the world living in both the Arctic and Japan in the same year (where she endured extreme temperatures which differed by 100C).

Towards the end of her Masters degree at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, she got the chance to live in the Arctic for 6 months to study the aurora from a glacier at the University Centre in Svalbard. This experience spanned the arctic winter, as well as studying in the land of the midnight sun.

Then as part of her PhD at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, she got the opportunity to climb mountains in Japan during a 6-month summer fellowship at the Kwasan Solar Observatory, part of Kyoto University.

She had her Dstl application form already prepared as she completed her PhD, but before she could submit it she was offered a post-doctoral research position at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, near Boston, in the USA.

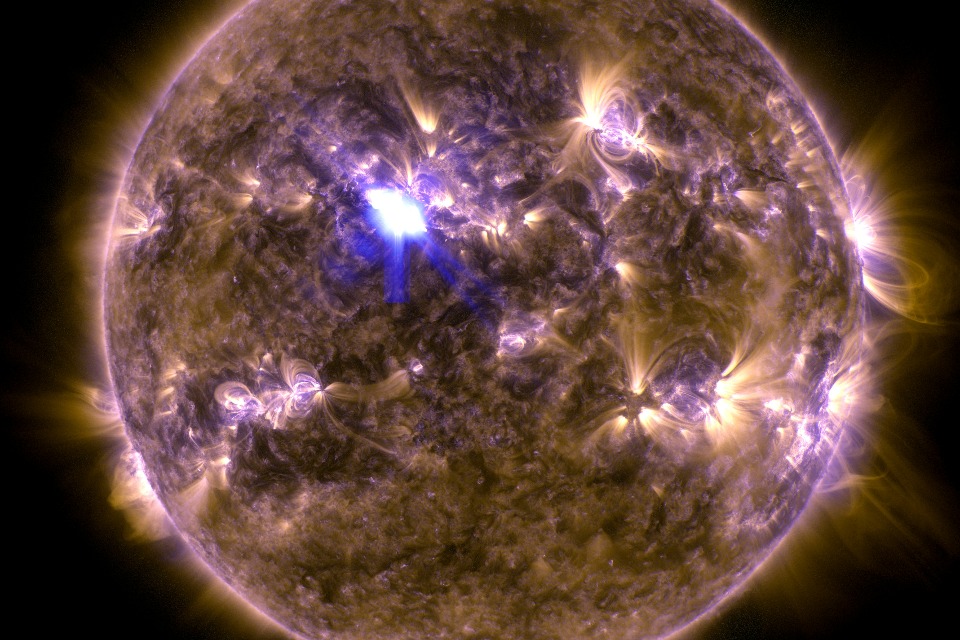

Her first job was for NASA, winning funding for her research which enabled the first observations of solar coronal waves using X-ray data from a Japanese-UK-US satellite mission.

After several years she dusted off her application, returned to the UK and joined Dstl as a systems engineer and set about “”working out where space was done within Dstl”.

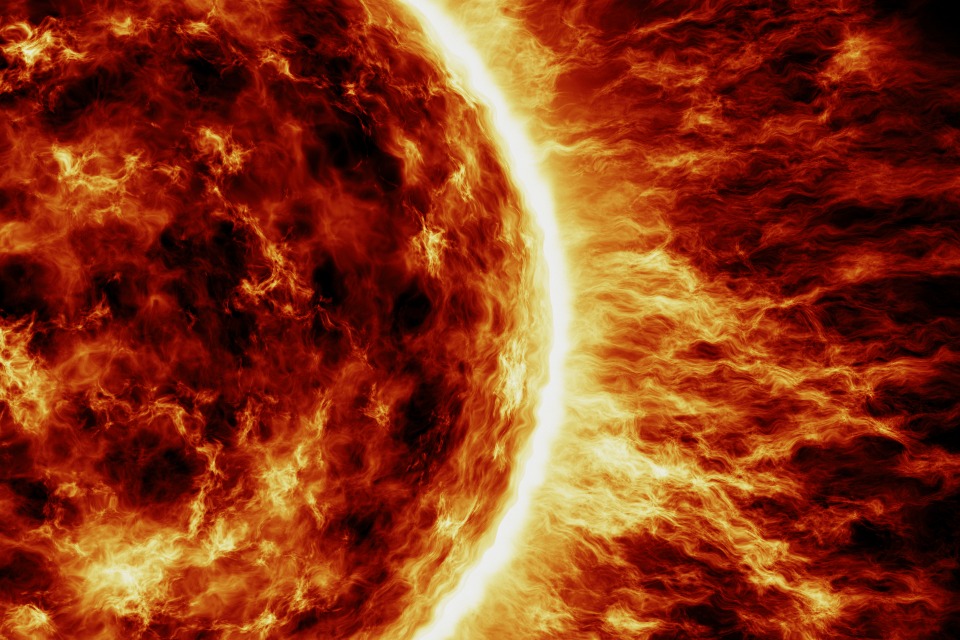

Her current work involves looking at the potential impact of both day-to-day, and extreme space weather driven by coronal mass ejections and solar flares. Plasma from the sun (many times the mass of Mount Everest, threaded by intense magnetic field lines) can be unleashed in a single eruption. Solar flares release huge amounts of energy and in 1859 the resultant storms overloaded the technology of the day (the telegraph system). This is known as the Carrington event.

There’s much more reliance on technology in the modern age. Extreme space weather is on the National Risk Register, and the Ministry of Defence (MOD) plays a role alongside other government departments in working to mitigate this risk.

CIRCE mission patch

She said:

“I think the most mind-blowing fact about space weather is how this is really, in many senses, a dangerous, life-threatening environment that we have to deal with that’s created by our star.

“It’s a real dichotomy when you, at once, have something that is so beautiful and life-giving and then can potentially be extraordinarily threatening as well.

“It is a real privilege to be working on something that impacts not only what we do here in defence, focused around the UK, but that also impacts society - humanity as a whole.”

Gemma has worked with the top minds in government, industry and academia across nations on a number of pioneering projects. She said working in space involved close collaboration with colleagues and partners to bring together a wide range of specialist knowledge.

Solar flare

She added:

“There is a tagline phrase which is used in the space industry, which is that ‘space is hard’.

“There are a huge variety of challenges which makes working in space really interesting and rewarding.”

Even though she no longer looks through a telescope as part of her role, she still remembers the special moment when she saw the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn as a student on a mountain in Wales.

Space Systems is one of our capability areas.

Gemma’s life changed after going to an amazing science facility… find out about our summer and industrial placements.