James Webb Space Telescope/MIRI

The telescope is studying the first stars and galaxies, and examining the physical and chemical properties of solar systems.

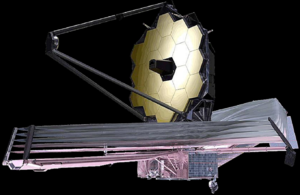

Artist's rendering of the JWST observatory. Credit: NASA

The UK in the James Webb Space Telescope

Looking back in time

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is looking further back in time than any other telescope, to 400 million years after the Big Bang.

JWST is a collaboration between ESA, NASA and the Canadian Space Agency, which launched on Christmas Day in 2021 as the successor to the Hubble Space Telescope.

The four key goals of the JWST are:

- to search for light from the first stars and galaxies that formed in the Universe after the Big Bang

- to study the formation and evolution of galaxies

- to understand the formation of stars and planetary systems

- to study planetary systems and the origins of life

These goals can be accomplished more effectively by observation in near-infrared light rather than the part of the spectrum visible to the human eye. For this reason, JWST’s instruments are not only measuring visible or ultraviolet light, like the Hubble Telescope, but using a much greater capacity to perform infrared astronomy.

JWST will also study the atmospheres of exoplanets identified by the European Space Agency PLATO science mission, which is necessary to understand their potential for hosting life.

By securing a leading role on this prestigious NASA mission, UK scientists involved are making their mark at the forefront of global space science research.

As the successor to Hubble, JWST is already generating astonishing images of our Universe, and inspiring the next generation of UK researchers and engineers.

Stephan’s Quintet galaxy grouping. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, and STScI

On 12 July 2022, NASA released the first images and spectroscopic data returned by JWST, using scientific instruments such as the UK-built mid-infrared instrument (details below). These stunning pictures include phenomena such as Stephan’s Quintet, the Carina Nebula, the Southern Ring, WASP-96b, and SMACS 0723, as they would have appeared billions of years ago. The infrared images are the sharpest and deepest ever taken of our Universe so far and marked the beginning of JWST’s science operations. View them in more detail on ESA and NASA websites.

What does the JWST do?

To study these distant objects, the telescope uses infrared light and must be cooled to within a few tens of degrees above Absolute Zero or -273°C. This is to prevent radiation from the telescope and its instruments swamping the astronomical signals. To achieve this, JWST uses a huge multi-layer sunshield which is the area of a tennis court.

The NASA time-lapse video reveals JWST under construction. (Credit: NASA Goddard)

To capture the very faint signals, the main telescope mirror is 6.5 metres in diameter, the largest ever flown in space, and is gold-coated to optimise its ability to reflect infrared light. Its 18 segments folded up inside the rocket for launch, then unfold in space.

JWST’s Integrated Science Instrument Module (ISIM) houses four instruments, which are:

- MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument)

- NIRCam (Near Infrared Camera)

- NIRSpec (Near Infrared Spectrograph)

- FGS/NIRISS (Fine Guidance Sensor/Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph)

How is the UK involved?

The UK led the European Consortium to build MIRI, which “sees” faint infrared (IR) light invisible to the human eye and peers far into the past, observing very distant galaxies and newly forming stars and planets. MIRI uses IR because, unlike visible light, it can penetrate the dense dust clouds which surround newly forming stars and planets.

The UK provided the scientific leadership on MIRI and the instrument design and managed the overall project. The UK was also responsible for the overall construction of the instrument and the quality control to ensure that MIRI would operate as intended and cope with the harsh conditions of space.

MIRI was the first instrument to be delivered to NASA, in May 2012. It was then integrated and tested with the other science instruments and the telescope.

MIRI was built for ESA by a European Consortium of 10 countries, led by Principal Investigator Prof Gillian Wright at the Science and Technology Facilities Council’s UK Astronomy Technology Centre. The European Consortium works in partnership with a team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab, who have contributed the detectors and cryo-cooler for MIRI.

Mission facts

The UK (UK Space Agency since 2011 and STFC) has invested almost £20 million in the development phase of MIRI and has continued to support essential post-delivery testing, integration, calibration and characterisation activities by the UK MIRI team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Centre, Johnson Space Centre and more recently at prime contractor Northrop Grumman in California.

This work is critical to understanding the instrument behaviour in operations and optimising the interpretation for the science data which will eventually be returned from the mission.

STFC’s UK Astronomy Technology Centre contributes the Instrument Science Leadership though Prof Gillian Wright, along with the optical design/engineering and calibration sources.

Other UK institutes involved in MIRI are:

- Rutherford Appleton Laboratory (Thermal engineering and instrument assembly integration and testing)

- Airbus Defence & Space UK (Consortium project management, Product Assurance co-ordination and System Engineering lead)

- University of Leicester (Mechanical Engineering and Ground Support Equipment)

- University of Cardiff (Calibration unit elements)

A full list of people from across the UK that are playing an active role in the JWST can be found on this page.

In March 2021, Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) announced the selected JWST General Observer programs for Cycle 1. The selected proposals were prepared by more than 2,200 unique investigators from 41 countries, including 43 US states and territories, 19 ESA member states, and 4 Canadian provinces. There were also more successful UK-led proposals than any other non-US country. More detailed information about the approved proposals can be found here.

For more information, visit the NASA, ESA and JWST UK websites.

Updates to this page

-

Updates made throughout the page.

-

Update to incorporate new information on the telescope

-

Updated after launch.

-

Updated launch date.

-

Updated May 2021.

-

Mission content updated.

-

First published.