Aligning your pension scheme with the TCFD recommendations: consultation guidance

Updated 2 July 2021

Ministerial foreword

Tackling climate change is one of the defining issues of the twenty-first century. It is a top priority for me as Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion. I am committed to ensuring all pension scheme trustees do everything they can to act to limit the risk climate change poses to their members’ future retirement income. These actions will also have beneficial impacts on our planet. TCFD is the most widely-adopted way in which organisations are managing and reporting climate risk, I want to ensure all trustees have the help they need to align their schemes with its recommendations.

That is why I am delighted that this guidance is being published for consultation. I would like to thank Stuart O’Brien of Sackers, and many others in the pensions industry, and civil society who have worked closely with the Government to create this guidance – written with industry, for industry.

We have come a long way over the past 18 months in terms of pension schemes’ governance of climate change as a major financially material risk to their investments. This action places the UK at the forefront of action on this globally.

In 2018, I clarified and strengthened, through regulation, the fiduciary duties of trustees to recognise the present and long-term risk and opportunities of ESG issues, including climate change, to the solvency of DB schemes and the value of members’ DC pensions, and act.

In 2019, those regulations came into force, and schemes are now required to document a policy on climate change and other financially-material risks related to ESG, and to update their Statement of Investment Principles accordingly.

The Government’s Green Finance Strategy, set an expectation that all large asset owners would be disclosing in line with the recommendations of the Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures by 2022. However, I am proposing to take powers in the current Pension Schemes Bill to require climate change risk governance and TCFD reporting. We will consult on these requirements later this year and issue further guidance on compliance with final regulations, as quickly as possible.

But my expectation is that schemes do not need regulations in order to start actively managing their exposure to climate change in line with the Taskforce recommendations and reporting on how they have done so. As more and more pension schemes move towards TCFD reporting voluntarily, it is absolutely imperative that trustees have the necessary skills and knowledge to follow the recommendations of the Taskforce.

That is why I welcome this guidance and the subsequent consultation. Pension schemes of all sizes will find helpful tips on how to embed climate change risk governance and identification of investment opportunities. Progressive schemes will find opportunities to show leadership in an area where members are increasingly engaged. I recognise concerns from some trustees that TCFD is beyond their capability at present. This guidance provides the framework that will help reassure trustees that all schemes, large or small, can manage exposure to the risk and opportunities of the transition to a low-carbon economy and the risk associated with a dramatically different climate in the future.

It is very important to me that every pension scheme trustee, civil society group, financial institution and indeed pension scheme member feeds their thoughts into the development of this guidance. There is no use in a single point of reference for trustees that does not reflect their requirements and those of the industry as a whole.

To conclude, pensions are all about savings for the long term. As an industry we know that if we don’t tackle climate change then the long term future for ourselves and our children will be severely compromised. We need to act.

I look forward to hearing your views.

Foreword by the Chair

Climate change poses an existential threat to our planet and society. We all try to do our bit to reduce our impact on the environment, but the task required to avoid dangerous levels of temperature increases is a collective challenge.

Against this backdrop it might be difficult to see the role trustees of UK pension schemes have to play. Most trustees will have acknowledged the financial risk of climate-related risk on their pension schemes but this is just one of a myriad of issues that trustees need to spend time considering. With a range of potential climate scenarios and highly complex impacts reaching far into the future, few trustees will have developed concrete plans to quantify and address the risks of climate change or capitalise on the opportunities of the transition to a net zero carbon economy.

However, trustees must act. Regulations require that trustees disclose and report on their climate policies and the Government has made clear its aim that schemes start actively managing their exposure to climate-related risks. Trustees should not approach the regulatory requirements as a tick-box exercise. Policies and risk management processes need to be meaningful for trustees to meet their overarching fiduciary duties, taking account of climate change as a material financial issue. It is for that reason that the Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group (PCRIG) was formed in 2019: to provide cross-industry guidance to help pension trustees meet their existing legal responsibilities. And it is with great pleasure that we launch this consultation on our new guide, providing practical steps to help trustees comply with their duties to manage climate-related risks.

For many pension schemes this may require new information. However, the process of risk management and setting investment strategies will already be familiar and the guide is designed to help trustees by providing a starting point for the integration of climate issues into existing trustee governance processes.

The guide also provides a framework for TCFD aligned disclosure. For trustees starting out, public disclosure may be a longer-term aspiration, but the process of following the TCFD recommendations, as set out in the guide, should provide a useful approach to assessing climate-related risks, enabling trustees to set a more resilient investment strategy for the benefit of their members.

Finally, over the page is a list of acknowledgments of all those members of PCRIG who have so generously given of their time to produce this guide. Without the contributions of each and every member of the group, production of the guide would not have been possible. In addition to this many more have provided their input along the way and I am grateful to all the trustees and professional advisers who have contributed and shared their wisdom and experience so far. We look forward to hearing the wider views of industry during the consultation.

Acknowledgements

The members of the Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group are:

Stuart O’Brien (Chair) – Sacker & Partners LLP

Edward Baker – Principles for Responsible Investment

Andrew Blair – Department for Work and Pensions

Alexander Burr – Legal and General Investment Management

Steven Catchpole – Aviva

Megan Clay – Client Earth (seconded to DWP until February 2020)

Claire Curtin – Pension Protection Fund

Caroline Escott – Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association

Benjamin Fagan-Watson – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

David Farrar – Department for Work and Pensions

Adam Gillett – Willis Towers Watson

Paul Hewitt – Vigeo Eiris

Melanie Jarman – The Pensions Regulator

Mark Jeavons – Aon

Claire Jones – LCP

Amanda Latham – The Pensions Regulator (until February 2020)

Adam Matthews – Church of England Pensions Board

Emmet McNamee – Principles for Responsible Investment

Catherine Ogden – Legal and General Investment Management

David Page – BMO Global Asset Management

Russell Picot – Special Adviser to the TCFD

Nadine Robinson – Climate Disclosure Standards Board

David Russell – Universities Superannuation Scheme

Matt Scott – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (until December 2019)

Nat Smith – Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy

Peter Uhlenbruch – Share Action (Asset Owners Disclosure Project)

Faith Ward – Brunel Pension Partnership

About this consultation

This consultation brings forward non-statutory guidance for the trustees of occupational pension schemes on assessing, managing and reporting climate-related risks.

Sections of the guidance may be of interest to others, including managers of funded public sector schemes.

This follows the Green Finance Strategy announcement of July 2019 that the Government and The Pensions Regulator had jointly established an industry group to develop TCFD guidance for pension schemes and would consult on the guidance.

Who this consultation is aimed at

- pension scheme trustees and managers

- pension scheme members and beneficiaries

- pension scheme service providers, other industry bodies and professionals

- civil society organisations; and

- any other interested stakeholders

Purpose of the consultation

This consultation seeks views on non-statutory guidance. Any moves to put the guidance onto a statutory footing will be subject to separate consultation.

Scope of consultation

As non-statutory guidance, the guidance is aimed at pension schemes in both Great Britain and in Northern Ireland. References to Great Britain legislation are to be taken, where necessary, as including the corresponding Northern Ireland legislation.

Duration of the consultation

The consultation period begins on 12 March and runs until 2 July 2020. Please ensure your response to the draft guidance reaches us by that date as any replies received after that date may not be taken into account.

How to respond to this consultation

Please complete the online questionnaire which accompanies this draft guidance.

Alternatively, if you wish to submit information which cannot be provided via a web form, please send your consultation responses to:

Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group

c/o Sacker & Partners LLP

20 Gresham Street, London, EC2V 7JE

Email: pensions.governance@dwp.gov.uk

Final guidance

We will aim to publish final guidance in the Autumn of 2020.

Our response will summarise the responses to this consultation.

Freedom of information

The information you send us may need to be passed to colleagues within the Department for Work and Pensions, published in a summary of responses received and referred to in the published consultation report.

All information contained in your response, including personal information, may be subject to publication or disclosure if requested under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. By providing personal information for the purposes of the public consultation exercise, it is understood that you consent to its disclosure and publication. If this is not the case, you should limit any personal information provided, or remove it completely. If you want the information in your response to the consultation to be kept confidential, you should explain why as part of your response, although we cannot guarantee to do this.

To find out more about the general principles of Freedom of Information and how it is applied within DWP, please contact the Central Freedom of Information Team:

Email: freedom-of-information-request@dwp.gov.uk

The Central FoI team cannot advise on specific consultation exercises, only on Freedom of Information issues. Read more information about the Freedom of Information Act.

Part I – Introduction

1. How to use this guide

- This guide aims to help trustees evaluate the way in which climate-related risks and opportunities may affect their strategies by making use of the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).

- Trustees should familiarise themselves with the framework of this guide and the separate “Quick Start Guide”.

- Part II of the guide sets out a suggested approach for the integration and disclosure of climate risk within the typical governance and decision-making processes of pension trustee boards. This focuses on how trustees might usefully consider climate-related risks and opportunities.

- Whilst the guide covers disclosure (as recommended by the TCFD), it is recognised that for many pension schemes this will be a new exercise, which may require new processes and information. Trustees may wish to use this guide to prioritise the adoption of robust governance procedures as a first step, with public disclosure as a second step. Where trustees do disclose, this guide seeks to align trustee governance and decision-making processes with the TCFD recommended disclosures. *Part III of the guide contains technical details on recommended scenario analysis and metrics that trustees may wish to consider using to record and report their findings. Whilst many trustees will ask their professional advisers to work through the detail and advise on implementation, the section contains freely available tools that trustees may use themselves.

1.1. Introduction

1. The Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is an independent body which has developed recommendations on how organisations can identify and disclose information about climate-related financial risks and opportunities. More detail on the TCFD’s recommendations is set out in Chapter 4.

2. By making use of the recommendations of the TCFD, this guide aims to provide a useful framework and guidance to help trustees of occupational pension schemes evaluate the way in which climate-related risks may affect the strategies and plans of the pension schemes they are responsible for, and then report on this activity to their stakeholders in a consistent and transparent manner.

3. The guidance is aimed at trustees of private sector schemes, but sections of the guidance may be of interest to others, including managers of funded public sector schemes.

1.2. Intended audience

4. Government has set the expectation that all listed companies and large asset owners, including occupational pension schemes, will disclose in line with TCFD by 2022. Amendments made to the Pension Schemes Bill will, if passed, provide a regulation making power for the Government to require prescribed pension schemes to publish climate change related risk information and to impose requirements with a view to securing that there is effective governance of those schemes with respect to the effects of climate change.[footnote 1]

5. Whilst smaller schemes may not yet be expected to report in line with the TCFD recommendations, most trustees are subject to statutory requirements to specify and disclose their policies on climate change and to carry out risk assessments (see Chapter 3 for further detail). This guide provides a suggested framework that all trust-based occupational pension schemes may find useful in order to develop such policies and integrate them into trustee decision-making. The framework may further assist trustees in demonstrating compliance with their fiduciary duties to take account of financially material factors and to act prudently.

6. Part III of this guide contains technical detail on the climate change scenario analysis that trustees may wish to consider and the decision-useful metrics that trustees can measure. Whilst some of this may be of greatest use to professional advisers and pension scheme providers, it is recognised that the resources available to each pension scheme will vary by scheme size, budget, type of benefits provided and the maturity of the scheme. Trustees can, however, approach this in a proportionate way. Chapter 10, in particular, suggests some freely available tools that trustees can use for basic scenario analysis.

1.3. Structure of this guide

7. This guide is structured sequentially based on the way a pension trustee board might typically approach decision-making. Part I sets out the legal requirements for pension scheme trustees to consider climate-related risk in their decision-making and more detail on the recommendations made by the TCFD.

8. Part II sets out a suggested approach for the integration and disclosure of climate risk assessment in the typical governance and decision-making framework of pension trustee boards, indicating (where applicable) how these align with the TCFD recommended disclosures. Guidance is also provided on how trustees should approach stewardship on climate-related issues, including exercising voting rights, reviewing progress and communicating with members about the actions taken. Chapter 8 provides some additional points for defined benefit schemes to consider, including the incorporation of climate-related risks into the employer covenant assessment.

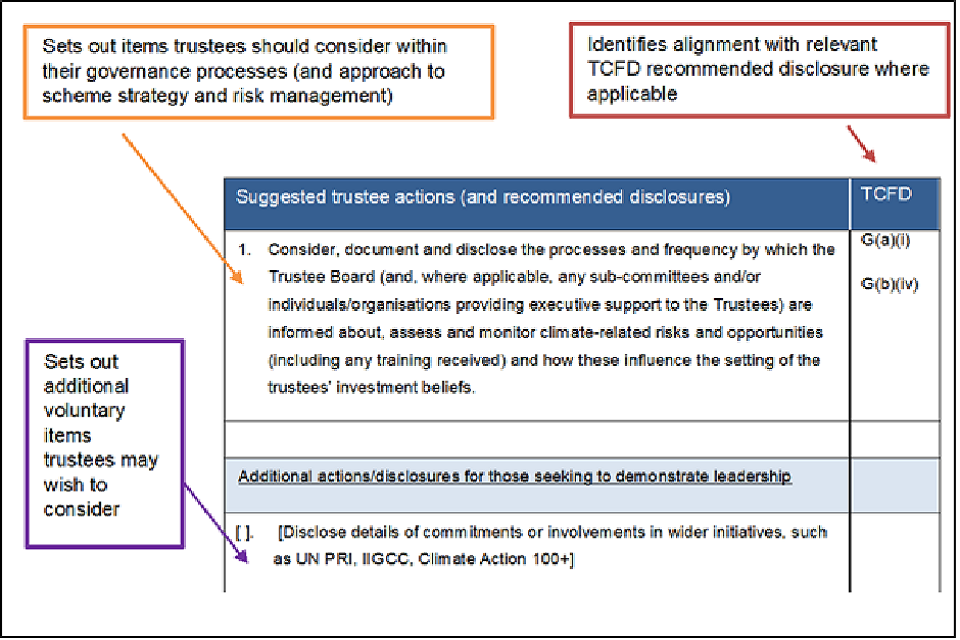

9. Each Chapter in Part II includes a summary table showing the suggested actions and disclosures for that chapter and the relevant TCFD disclosure recommendation.

Figure 1: Guide to the summary tables

10. In Part III, the guide sets out how trustees can analyse the resilience of their scheme to different climate-related scenarios, including the transition to a lower-carbon economy. Models are provided for trustees to assess resilience both qualitatively and quantitatively, and recommendations are made as to the metrics and target which trustees can use to help to measure and manage climate-related risk exposure.

11. Appendices can be found in Part IV.

2. Introduction - Understanding climate change as a financial risk to pension schemes

- All pension schemes, regardless of size, investments or their time horizons, are exposed to climate-related risks. When considering the financial implications of climate change, trustees should understand the different implications of transition risks and physical risks on their investments.

- As investors, most schemes have capital at risk as a result of the low carbon transition. In addition, many defined benefit schemes are supported by employers or sponsors whose financial positions and prospects are dependent on current and future developments in relation to climate change.

- The Paris Agreement aims to ensure that the increase in average temperatures above pre-industrial levels is kept to ‘well below’ 2°C by 2100 and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C. The longer the delay in climate policy action, the more forceful and urgent any regulatory policy intervention will inevitably be and the more severe the likely impact will be on companies and investors.

2.1. The financial risk of climate change

12. The world’s climate is already 1°C warmer today[footnote 2], on average, than relative to pre-industrial times and the rate of increase is roughly ten times faster than the average rate of ice-age-recovery warming. The dominant cause for this is extremely likely to be the rapid increase in anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases which are now at concentration levels unprecedented in at least 800,000 years[footnote 3].

13. The average temperature rise conceals more dramatic changes at the extremes and is already having disruptive effects. It is a risk multiplier, exacerbating existing issues with energy, resource and food security and increasing the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events. This is made worse by the size of, and inertia in, the climate system which creates a multi-decadal lag between carbon dioxide emitted today and its full impact, meaning that further warming is already “locked-in” and climate-related risk will grow over time.

Climate change poses unprecedented challenges… The increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events could trigger non-linear and irreversible financial losses. In turn, the immediate and system-wide transition required to fight climate change could have far reaching effects potentially affecting every single agent in the economy and every single asset price.

François Villeroy de Galhau Governor of the Banque de France

Bank for International Settlements report: Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change (2020) [footnote 4]

14. All pension schemes are exposed to climate-related risks, whether investment strategies and mandates are active or passive, pooled or segregated, growth or matching, or have long or short time horizons. Many schemes are also supported by employers or sponsors whose financial positions and prospects are dependent on current and future developments in relation to climate change.

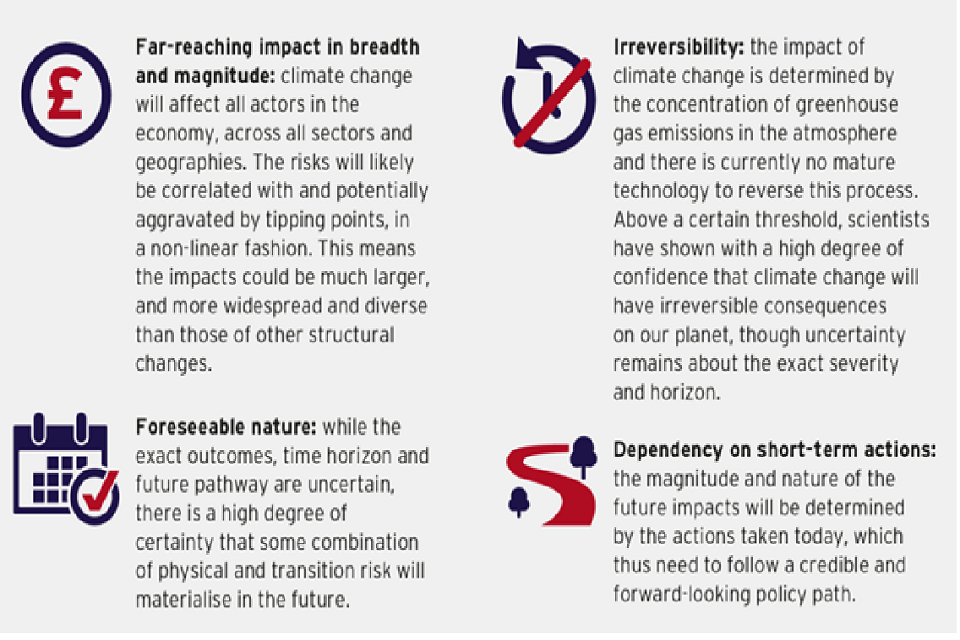

Figure 2: Distinct characteristics of climate change that require a different approach [footnote 5]

15. The potential severity of the physical impacts of climate change and its direct correlation with the concentration of greenhouse gases motivated the international community to commit to reducing emissions in Paris in December 2015. The Paris Agreement[footnote 6], an international treaty negotiated by 197 parties, aims to ensure that the increase in average temperatures above pre-industrial levels is kept to ‘well below’ 2°C by 2100 and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C (Article 2.1(a) UNFCCC, 2015). Restricting global average temperature increases to these levels will require a significant change in the fundamental structure of the economy at national and international levels.

This Agreement […] aims to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change, in the context of sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty, including by […] making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

Paris Agreement, Article 2.1(c) UNFCCC, 2015

16. This is likely to affect all parts of the economy, especially energy, manufacturing, construction, transport and agriculture. These transformations and the transition to the low-carbon economy create risks for companies that do not plan and adapt adequately and to the pension funds that hold their equity and debt. It may result in ‘stranded assets’, where the value of certain assets is significantly reduced because they are rendered obsolete or non-performing from a financial perspective.

17. This will be particularly relevant to energy intensive sectors, the fossil fuel-based industries and the wide range of companies and sectors whose current business models are predicated on significant energy use and/or greenhouse gas emissions, most commonly through burning fossil fuels. These companies will be subject to hardening regulatory limits or financial penalties imposed on their activities, replacement by climate-friendly competitors, decarbonisation of the power supply, legal challenges and other non-conventional challenges such as reputational issues resulting from their impact on the climate. Investors will have capital at risk as a result of the low carbon transition.

18. The impact on pension schemes as investors may not be immediately obvious or uniform. For example, whilst the utility sector is one of the most strongly exposed to climate policy risk, it may contribute a relatively small proportion of a typical pension scheme’s investment portfolio. On the other hand, manufacturing may have a lower sectoral risk but may constitute a larger part of a pension scheme’s portfolio and may therefore have a greater overall effect. Trustees need to consider the impacts across their portfolios as a whole.

2.2. Types of climate-related risks

19. When considering the financial implications of climate change, a distinction can be drawn between transition risks and physical risks. The former relates to the risks (and opportunities) from the realignment of our economic system towards low-carbon, climate-resilient and carbon-positive solutions (e.g. via regulations or market forces). The latter relates to the physical impacts of climate change (e.g. rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, increased risk to coastal systems and low-lying areas from rising sea levels and increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events).

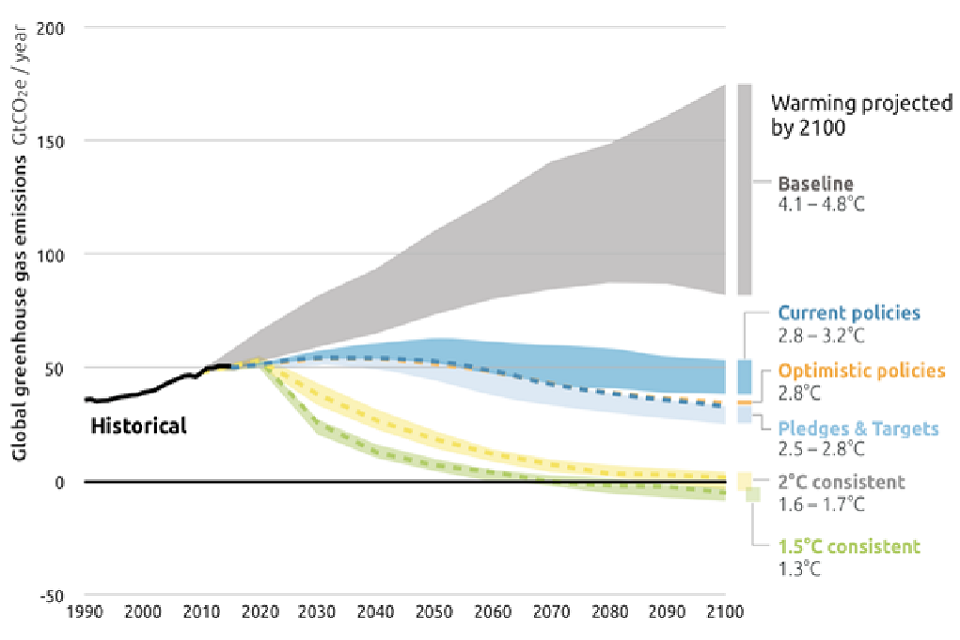

20. Perhaps of greatest concern is the significant risk that policy achievement falls short of the Paris Agreement goal, leading to global average temperature increases well in excess of 2°C. Current policies fail to get even close to 2°C let alone the Paris Agreement ambition of well-below 2°C.

21. Temperature rises based on current policies (with estimates varying from 2.8 to 3.2°C relative to pre-industrial levels based on the current trajectory) would have large and detrimental impacts on global economies, society and investment portfolios.

Figure 3: 2100 Warming projections - emissions and expected warming based on pledges and current policies

Source: Climate Action Tracker, Dec 2019 update[footnote 7]

Stranded asset risk

Various research reports have studied the risk of fossil fuel assets becoming ‘stranded’ assets[footnote 8] which ‘at some point prior to the end of their economic life (…) are no longer able to earn an economic return’. This can occur due to a change in policy/legislation, a change in relative costs/prices, or circumstances in the physical environment (e.g. impact of floods or droughts).

Fossil fuels are the most obvious example of assets at risk of stranding and there are already examples of coal mines, coal and gas power plants, and hydrocarbon reserves which have become stranded by the low carbon transition. However, other assets may be affected such as gas pipelines and agricultural assets.

Reports have produced varying estimates of the financial impact based on different future scenarios, some of which could have materially detrimental impacts on investment portfolios. It is therefore in the interest of trustees and boards to explore stranded asset risks in the context of their own portfolios, defining their beliefs and assessing current portfolio exposure.

2.3. The impact of the inevitable policy response

22. With current policies anticipated to lead to temperature increases of around 3°C, the longer the delay in climate policy action, the more forceful and urgent any regulatory policy intervention will inevitably be in order to limit global average temperature increases to a level that’s more likely to allow for economic and social stability. This would have a more severe impact on companies and pension schemes as investors.

23. We know now that annual global emissions must start to reduce with a significant annual rate of reduction thereafter[footnote 9]. Without this, companies face increased cost and uncertainty from a disorderly low-carbon transition and increased physical risks, and investors face increased risk compared to a scenario where climate policy is enacted smoothly and steadily[footnote 10].

2.4. Why trustees cannot assume climate-related risks are already “priced-in”

24. An investor might expect financial market prices – at least in an efficient market – to already reflect the risks presented by a transition to a lower carbon economy and there is some evidence that markets are now partly pricing in climate change risks. However, asset prices may not fully reflect the financial impact of future physical risks or the transition costs associated with policy action required to limit global warming to 2°C or less.[footnote 11] This is particularly so where “business as usual” models are based on current policies, which are anticipated to lead to temperature increases of around 3°C.

Climate change is striking harder and more rapidly than many expected.

World Economic Forum, Global Risks Report 2020[footnote 12]

25. There are a number of reasons for this. The future of climate policy is highly uncertain given the extended time horizons and political economy considerations, while forecasting requires very long-term projections. There are also challenges in differentiating between long-term economic effects, what the markets are currently pricing, and the potential market shocks if and when the market re-prices climate risks.

26. Finally, the market pricing of assets will say little about a given investor’s own attitude or tolerance to risk, or the implications of different climate scenarios. Trustees should therefore be wary about relying on marked to market pricing of assets as a measure of climate-related financial risks.

3.The legal requirements on trustees to consider climate-related risks

- Trustees have a legal duty to consider matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making. The climate crisis poses a financial risk to all asset owners. Trustees should consider how, and to what extent, it could impact their investments and the necessary actions that arise from that assessment. This will depend on the investments held and the duration of the scheme. In the case of defined benefit schemes, trustees should also consider potential impacts on their sponsor covenant.

- Trustees have additional statutory obligations to document their policies on material financial factors and to consider and document their approach to risk. These statutory obligations specifically require consideration of climate change.

- The Pensions Regulator considers climate change to be systematically significant to its regulatory regime, including protecting member benefits and reducing calls on the PPF.

3.1. Fiduciary duty

27. Trustees should take advice on their legal duties in the context of specific exercises of investment powers, but may wish to think in terms of three core duties when making investment decisions, as outlined below.

28. In practice day-to-day investment decisions will almost always be delegated to a third party (and in most cases trustees will act on professional advice from investment consultants). However, trustees should be mindful that they retain overall responsibility for securing members’ benefits and are required to provide proper oversight of their delegates (including fiduciary managers) [footnote 13]

(A) Exercise investment powers for their proper purpose

29. Pension scheme trustees must exercise their investment powers for the purposes for which they were given.[footnote 14] The consideration of climate-related risks and opportunities should take place in this context. Trustees should consider how properly taking into account climate-related risks and opportunities will assist in delivering on the purpose of the trust (namely for the provision of pension benefits).

30. In a defined contribution scheme trustees must not relegate the consideration of climate change to members via self-select funds. Rather, trustees must consider its relevance as part of their duty to provide both a default fund and self-select funds appropriate to the needs of the membership.

(B)Take account of material financial factors

31. Trustees should always take into account any relevant matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making. These are frequently referred to as “financial factors”.[footnote 15] This may well be about whether a particular factor is likely to contribute positively or negatively to anticipated returns. But it may equally be about whether a factor will increase or reduce risk.

32. A wide range of factors may impact the long-term sustainability of an investment, including poor governance or environmental degradation. These can all properly be considered by pension trustees to the extent that they are financially material.

33. Chapter 2 explains in further detail the financial risks of climate change and the low carbon transition. Whenever trustees consider that such factors are financially material to their scheme, they should take them into account in their investment decision-making.[footnote 16]

34. When considering the financial implications of climate change, trustees should consider the financial implications of both transition risks and physical risks and determine the extent to which they are financially material to:

- in a defined benefit scheme: the scheme’s assets, liabilities and the covenant of the sponsoring employer(s); and

- in a defined contribution scheme: the investment risk and returns of the default fund and any applicable member self-select funds (see below).

35. Where appropriate, trustees should take advice and implement processes to build climate resilience across pension scheme assets.

36. Trustees of schemes providing defined contribution benefits must consider the implications of climate-related risks on any default fund and may also need to consider the extent to which they are taken into account in any member self-select funds (including AVCs). The nature of the funds may dictate which factors are taken into account in the investment processes of those funds. However, trustees should ensure that the funds remain suitable for their members and the materials in relation to them are sufficiently clear, including as to climate-related risks.

(C) Act in accordance with the “prudent person” principle

37. Trustee investment powers must be exercised with the “care, skill and diligence” that “a prudent person would exercise when dealing with investments for someone else for whom they feel morally bound to provide”.[footnote 17]

38. Prudence will always be context specific and will evolve over time. In a defined benefit scheme prudence should be assessed by reference to funding levels and employer covenant and the likely time horizon over which members’ benefits will be paid. In a defined contribution scheme trustees should consider what is appropriate to the membership demographic and the investment objectives of the investment options, including the scheme’s default fund. Trustees should also bear in mind that many members’ pensions will be invested for a long time (including in drawdown/annuity policies) and will be exposed to longer-term risks.

39. The financial risks from climate change have a number of distinctive elements which present unique challenges and require a strategic approach to financial risk management[footnote 18]. In line with the prudent person principle, trustees must consider likely future scenarios, how these may impact their investments and what a prudent course of action might be as part of their scheme’s risk management framework. Past data may not be a good indicator of future risks.

40. Trustees should also recognise that market standards are evolving in this area and that what may be considered “prudent” in relation to climate-related risks today might no longer meet that standard in the future, given developing understanding of these risks. Trustees should keep matters under review.

3.2. Pensions Legislation

Statutory requirements apply to pension trustees in addition to their fiduciary duties. Again, trustees should take advice on their legal obligations but should take note of the following regulatory requirements in particular[footnote 19]:

(A) Effective system of governance including internal controls

42. Section 249A of the Pensions Act 2004 requires that the trustees or managers of pension schemes in scope should have “an effective system of governance including internal controls”, on which The Pensions Regulator must issue a Code of Practice covering matters such as how that effective system of governance:

- provides for sound and prudent management of their activities;

- includes consideration of environmental, social and governance factors related to investment assets in investment decisions; and

- is subject to regular internal review

43. The Code of Practice must also cover key functions including an effective risk-management function, and the need for trustees to carry out and document their own-risk assessment. Where environmental, social and governance factors are considered in investment decisions, the Code of Practice will also cover how such risk assessment must include an assessment of new or emerging risks, including risks related to climate change, use of resources and the environment (physical risks), social risks and risks related to the depreciation of assets due to regulatory change (transition risks).

[Note – At the time of writing the Code of Practice has not been published. This section will be updated to correspond with TPR’s updated Code, when available] [footnote 20]

(B) Disclosure of policies in Statement of Investment Principles

44. For pension schemes to which section 35 of the Pensions Act 1995 applies (broadly, trust-based schemes with at least 100 members), the trustees must prepare a Statement of Investment Principles (SIP). The purpose of a SIP is to set out the trustees’ investment strategy, including their investment objectives and the investment policies they adopt.

45. Trustees must include in their SIPs their policies in relation to risks, including the ways in which risks are measured and managed[footnote 21]. Further requirements in relation to the required content of the SIP are included in the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005.[footnote 22] Specific requirements pertinent to climate change include:

- Trustees must, from 1 October 2019, include their policies in relation to:

– “financially material considerations” over the appropriate time horizon of the investments, including how those considerations are taken into account in the selection, retention and realisation of investments[footnote 23]. Financially material considerations are defined to include “environmental, social and governance considerations (including but not limited to climate change), which the trustees consider financially material”; – the exercise of the rights, including voting rights attaching to the investments, and on engagement activities in respect of the investments, including when and how the trustees would engage with issuers, asset managers, stakeholders and co-investors on matters including the issuer’s strategy, risks, social and environmental impact and corporate governance.

- Trustees must, by 1 October 2020, include their policies in relation to the trustees’ arrangements with their asset manager(s), setting out how they incentivise each manager to align its investment strategy and decisions with the trustees’ policies mentioned above and to make decisions based on assessments about medium to long-term performance.

(C) Annual Report and Accounts

47. Trustees are required to prepare an annual report and accounts within seven months of the end of each scheme year. Further requirements in relation to the required content of the annual report and accounts are included in the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013.[footnote 24]

48. Trustees should take advice on the timing and content required in relation to their particular scheme, although, broadly in each annual report prepared after 1 October 2020:

- Trustees of defined benefit schemes must include a statement on how their voting and engagement policies have been implemented.

- Trustees of schemes providing defined contribution benefits are required to include a statement setting out how, and the extent to which, all policies have been implemented during the year.

(D) Pension Schemes Bill

49. Amendments made to the Pension Schemes Bill[footnote 25] will, if passed, provide a regulation making power for the Government to require pension schemes to publish climate change-related risk information and further to impose requirements with a view to securing that there is effective governance of the scheme with respect to the effects of climate change. At the time of writing, however, such provisions have not yet been enacted.

The Pension Schemes Bill

Government has tabled an amendment to the Pension Schemes Bill which seeks to amend the Pensions Act 1995. It sets out that:

Regulations may impose requirements on the trustees or managers of an occupational pension scheme of a prescribed description with a view to securing that there is effective governance of the scheme with respect to the effects of climate change.

The requirements which may be imposed by the regulations include, in particular, requirements about

(a) reviewing the exposure of the scheme to risks of a prescribed description;

(b) assessing the assets of the scheme in a prescribed manner;

(c) determining, reviewing and (if necessary) revising a strategy for managing the scheme’s exposure to risks of a prescribed description;

(d) determining, reviewing and (if necessary) revising targets relating to the scheme’s exposure to risks of a prescribed description;

(e) measuring performance against such targets;

(f) preparing documents containing information of a prescribed description.

Separately:

Regulations may require the trustees or managers of an occupational pension scheme of a prescribed description to publish information of a prescribed description relating to the effects of climate change on the scheme.

It also sets out that

In complying with requirements imposed by the regulations, a trustee or manager must have regard to guidance prepared from time to time by the Secretary of State.

Statutory guidance will be separately developed by Government and consulted on in due course.

Voluntary obligations

Trustees who have agreed to become signatories to voluntary initiatives may have already accepted additional climate reporting obligations.

PRI signatories: the PRI is making some climate indicators mandatory to report to PRI itself but voluntary to disclose publicly. The remaining PRI climate-related risks indicators will stay voluntary with a view to becoming mandatory as good practice develops.

Stewardship Code signatories: [footnote 26] signatories must (principle 4) report on how they have identified and responded to market-wide and systemic risks including climate change, and how they have (principle 7) ensured tenders have included a requirement to integrate climate change to align with the time horizons of clients and beneficiaries

4. The TCFD recommendations

- TCFD establishes a set of eleven clear, comparable and consistent recommended disclosures about the risks and opportunities presented by climate change. The increased transparency encouraged through the TCFD recommendations is intended to lead to decision-useful information and therefore better informed decision-making on climate-related financial risks.

- By applying the TCFD recommendations and making the recommended disclosures, pension trustees will be better placed to properly assess and understand what climate change actually means for their particular scheme – and will be better equipped to make decisions that ensure the best outcomes for pension scheme members.

4.1. A lens for understanding climate-related financial risks

50. The Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) was established as an industry-led initiative in December 2015 to develop recommendations for clear, comparable and consistent disclosures of climate-related risks and opportunities in mainstream financial reports. The TCFD aimed to improve the quality of climate-related financial disclosures thereby “support[ing] more appropriate pricing of risks and allocation of capital in the global economy”. [footnote 27]

51. The TCFD recommendations (issued in June 2017) establish a set of recommended disclosures through which organisations can identify and disclose decision-useful information about material climate-related financial risks and opportunities. [footnote 28] The recommendations are also applicable to asset owners and asset managers. As of February 2020, 1027 organisations globally had declared their support for the TCFD, representing a market capitalisation of over $12 trillion[footnote 29] and extensive work is ongoing across a number of industry and regulatory groups to support widespread implementation of the TCFD’s recommendations.[footnote 30]

52. The TCFD recommendations are structured around four thematic areas that represent core elements of how organisations operate: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets. These might be considered to apply to pension trustees (as asset owners) as follows:

Figure 4: The TCFD recommendations

Governance – Disclose the trustees’ governance around climate-related risks and opportunities

Strategy – Disclose the actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the pension scheme where such information is material

Risk Management – Disclose how the trustees identify, assess, and manage climate-related risks

Metrics and Targets – Disclose the metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities where such information is material

53. The four core elements of the TCFD recommendations are supported by eleven recommended disclosures set out in the table below. Further guidance provided by the TCFD on the recommended disclosures specific to asset owners is set out in Appendix 1.

TCFD Recommended disclosures

| Governance | Strategy | Risk Management | Metrics and Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| a) Describe the board’s oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities | a) Describe the climate-related risks and opportunities the organisation has identified over the short, medium, and long-term. | a) Describe the organisation’s processes for identifying and assessing climate-related risks. | a) Disclose the metrics used by the organisation to assess climate-related risks and opportunities in line with its strategy and risk management process. |

| b) Describe management’s role in assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities. | b) Describe the impact of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy, and financial planning. | b) Describe the organisation’s processes for managing climate-related risks. | b) Disclose Scope 1, Scope 2, and, if appropriate, Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions, and the related risks.[footnote 31] |

| c) Describe the resilience of the organisation’s strategy, taking into consideration different climate-related scenarios, including a 2°C or lower scenario. | c) Describe how processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related risks are integrated into the organisation’s overall risk management. | c) Describe the targets used by the organisation to manage climate-related risks and opportunities and performance against targets. |

4.2. Why the TCFD recommendations may be helpful for pension trustees

54. As set out in Chapter 3, pension trustees are already subject to a number of statutory requirements to specify and disclose their policies on climate change, alongside other policies relating to environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. Several of the TCFD disclosures align to these existing statutory requirements, including disclosure of trustees’ strategy via their policies on climate change, and their governance, via the requirement for an effective system of governance that includes “consideration of environmental, social and governance factors related to investment assets in investment decisions”.

55. All the TCFD disclosures are likely to assist trustees demonstrate compliance with their fiduciary duties to take account of relevant factors which are financially material to their investment decision-making and to act prudently.

56. Although the TCFD recommendations focus on “disclosures” by organisations, the framework is fundamentally a useful tool for pension trustees in assessing the relevance of climate change and managing any consequences. This may assist trustees in meeting the legal requirements on considering climate-related risks. It will also be a useful lens for trustees of DC and hybrid schemes as they compile the relevant statement on how they have implemented policies in the SIP, as required from October 2020. In particular, the TCFD’s Strategy (c) recommendation to assess the resilience of their strategies (and by extension portfolio) using scenario-based analysis (see Chapter 10) encourages forward-looking, long-term assessment of the financial implications of climate change.

4.2. Disclosure: the voluntary – for now – ‘D’ in TCFD

57. The disclosure – the ‘D’ - aspect of TCFD is voluntary at present. Failure to publish in line with TCFD would not mean that a scheme was in breach of regulation (though schemes without adequate processes for managing material climate risks might well be). In any event, the increased transparency encouraged under the TCFD recommendations and 11 recommended disclosures is intended to lead to better informed decision-making. More broadly, better quality information contributes towards more efficient and sustainable markets.

58. The voluntary requirement to disclose, however, may change, in light of amendments to the Pension Schemes Bill[footnote 32] and given the Government’s statement (set out in the 2019 Green Finance Strategy) that all listed companies and large asset owners, including occupational pension schemes, are expected to disclose in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022.[footnote 33]

59. This guide will help schemes to lay the groundwork and develop good practice in the meantime.

60. To promote disclosure of “decision-useful” information, the TCFD has outlined seven Principles for Effective Disclosures, which should: 1) represent relevant information; 2) be specific and complete; 3) be clear, balanced, and understandable; 4) be consistent over time; 5) be comparable among companies within a sector, industry, or portfolio; 6) be reliable, verifiable, and objective; 7) be provided on a timely basis.

PART II – Integrating and disclosing climate-related risks in trustee governance, strategy and risk management

5. Defining climate-related investment beliefs

- Investment beliefs can help focus trustees’ investment decision-making and make it more effective. Climate change should be considered as part of these beliefs.

- Trustees should allow appropriate time and training to ensure that they have a sufficient understanding of climate change to define their investment beliefs.

- Trustees should consider the roles and responsibilities within the trustee board (and, where applicable, any sub-committees and/or individuals/organisations providing executive support to the trustees) for climate-related issues.

5.1. Investment beliefs

61. Trustees may find it helpful to develop and maintain a set of beliefs about how investment markets function and which factors lead to good investment outcomes.[footnote 34] Investment beliefs, developed by reference to research and experience, can help focus trustees’ investment decision-making and make it more effective. Climate change should be considered as part of these beliefs. Trustees’ investment beliefs should not be confused with their personal (i.e. ethical or moral) beliefs.

62. Trustees should define their climate-related investment beliefs (e.g. about potential future climate change scenarios, how to manage their impacts and take climate-related opportunities). Beliefs should take into account practical circumstances (e.g. scheme size/resources, internally/externally managed assets and preference for an active/passive investment approach).

63. Trustees may wish to consider including in their investment beliefs the trustees’ position on the following:

- clarifying the trustees’ position on climate change considerations as part of the trustee fiduciary duty.

- the extent to which the trustees consider market prices reflect climate-related risks and the ability of asset managers to exploit any mispricing.

- clarifying the trustees’ convictions around the balance between engagement, voting and/or divestment as appropriate tools to manage climate-related risks.

- Recognising the way in which climate-related risks can be taken into account (both as a risk and an opportunity) in active/passive mandates and in relation to different asset classes.

64. Trustees should consider the internal consistency of their investment beliefs. For example, trustees of defined contribution schemes who believe in the efficacy for the scheme’s default fund of a pure passive market-cap weighted fund with no flexibility to reduce allocations selectively should consider how this will reconcile with strong beliefs in relation to the impact of climate change on markets during the time horizon of the scheme’s members. Likewise, trustees who believe in the ability of asset managers to identify and exploit asset mispricing should consider how this reconciles with a view that climate-related risks alone have been adequately “priced in” to company valuations.

5.2. Trustee climate competence: knowledge and understanding required to define investment beliefs

65. Where trustees identify a lack of sufficient understanding of climate-related financial risks to define their investment beliefs on the issue with confidence (or that there has previously been insufficient time allocated on board agendas to it), they should allocate specific time at a future board meeting or an investment strategy session dedicated to climate-related risk issues.[footnote 35] Trustees should ensure that they allow adequate time to look at the issue in sufficient depth to ensure that they are meeting their legal duties. This might include more detailed sessions on:

- the latest evidence on the investment impacts of climate change and views from investment consultants, asset managers, independent experts and other advisers on how climate-related risks and opportunities have the potential to affect different investment portfolios.

- the trustees’ legal obligations to consider and act on climate-related issues (and the extent to which the trustees’ policies need to be disclosed or reported on).

- in a defined benefit scheme, the potential impact of climate-related risks on the scheme sponsor’s covenant.

- the range of possible actions that might be taken to help manage climate-related risks (and capture the opportunities), including case studies of good practice actions across the investment community. Trustees may also wish to consider the potential impacts if there is an active decision to ‘do nothing’.

| Investment beliefs – Suggested trustee actions (and recommended disclosures) | TCFD |

|---|---|

| 1. Identify, document and disclose the relevant climate-related investment beliefs and policies of the trustee board, whether these are set by the trustees or a sub-committee (e.g. investment sub-committee) and the frequency of their review. | |

| 2. Consider, document and disclose the processes and frequency by which the trustee board (and, where applicable, any sub-committees and/or individuals/organisations providing executive support to the trustees) are informed about, assess and monitor climate-related risks and opportunities (including any training received) and how these influence the setting of the trustees’ investment beliefs. | G(a)(i) G(b)(iv) |

| 3. Identify, define and disclose the roles within the trustee board (and, where applicable, any sub-committees and/or individuals/organisations providing executive support to the trustees) that have oversight, accountability and/or manage responsibilities for climate-related issues. | G(b)(i) |

| Additional actions/disclosures for those seeking to demonstrate leadership | |

| 4. Disclose details of commitments or involvements in wider initiatives, such as UN PRI, IIGCC, Climate Action 100+ etc. |

6. Considering climate-related risks in setting scheme investment strategy and manager selection, review and monitoring

- Trustees should consider how different investments and investment strategies could be affected by the transition to a low carbon, climate-resilient economy and under different future climate scenarios.

- Scenario analysis and modelling are helpful tools to use in considering climate risks in setting the scheme’s investment strategy.

- Trustees should consider their risk appetite and time horizons in the context of their scheme and their current investment strategy, noting the need for well-defined risk management processes to ensure climate related-risks are effectively measured and managed.

- Trustees should consider how climate risks may affect different asset classes and sectors in which the scheme has invested and the investment approaches in each portfolio.

- Having determined their overall strategic asset allocation, trustees should consider the mandates set for each asset class and the method by which investments are made; and they should identify strategic actions to reduce exposure to climate-related risks, as well as options for investment in climate-related opportunities.

- Climate competence should be factored into both manager selection, review and monitoring to execute agreed mandates for each asset class and method of investment.

- Trustees should make use of the expertise of their investment consultants and advisers but should not be overly reliant on them to set the agenda. Trustees should challenge advisers and set objectives for them to factor climate-related risks into their advice.

6.1. Investment (and investment adviser) objectives

66. Trustees should set clear investment objectives for their scheme (and their advisers) and identify how and when they should be achieved. A scheme’s investment strategy (and any adviser objectives to support that strategy) should support and be consistent with the trustees’ objectives, taking account of the trustees’ view of climate-related risks in the circumstances of the scheme and allowing for the fact that the objectives may evolve over time.

67. Trustees should distinguish between strategies for defined benefit and defined contribution schemes. In a defined benefit scheme, this will involve considering the scheme’s funding levels and employer covenant as part of an integrated risk management (IRM) approach.[footnote 36] In a defined contribution scheme, trustees should consider the risk/return profile appropriate to the membership and in particular the design of the default investment strategy. This will involve consideration of the needs of the scheme’s members, and how these might change in the future.[footnote 37]

6.2. Considering risk appetite

68. Considering risk appetite can help trustees determine whether their current investment strategy is appropriate. Trustees should consider how different investments and investment strategies could be affected by the transition to a low-carbon economy and/or the physical impacts of climate change under different scenarios and whether implementing an alternative strategy may be more likely to achieve the scheme’s objectives. Trustees should also consider their risk appetite for capitalising on investment opportunities connected with the transition to a low-carbon economy and, if applicable, their belief that they should help to fund investments that are needed to achieve the low carbon transition.

69. Adequate risk management depends on having the right processes and the right metrics in place. However, it is worth reiterating that climate change represents a negative externality that carries potentially very high and costly market-wide risks which may be largely unpriced or mispriced. The scale and complexity of climate change and its resulting impacts requires strong and well-defined risk management processes to ensure that the risks are being measured and managed.

6.3. Use of scenario analysis

70. Trustees should:

- undertake climate scenario analysis and/or modelling, considering the scenarios to be used, how the impacts are calculated and the output of the analysis (by asset class, sector, strategic asset allocation etc.)

- consider how they use scenario analysis (including the impact of different scenarios on different types of assets, sectors and investment approaches within each portfolio) to manage climate related risks and opportunities, including how the analysis has been interpreted and acted on and any future plans.

71. See Chapter 10 for further details on scenario analysis.

6.4. Considering climate-related risks as part of strategic asset allocation

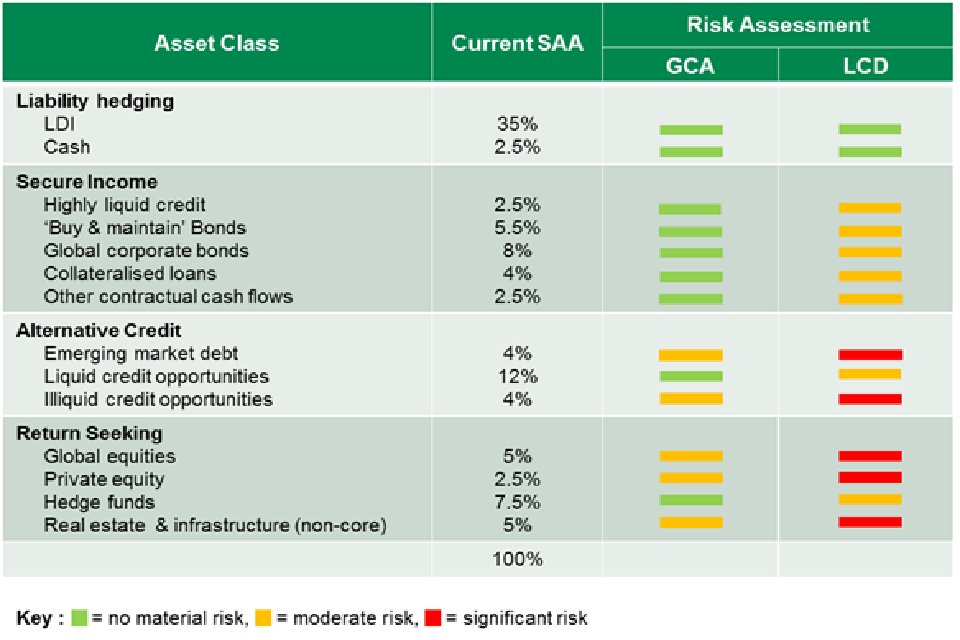

72. Trustees should consider how climate-related risks may affect the different asset classes the pension scheme is invested in over time.

73. The proportion of different types of growth, matching and other assets held will vary by scheme (depending in a defined benefit scheme on the maturity of the scheme, its funding levels and employer covenant). In a defined contribution scheme a default fund may have a pre-determined process by which assets are transitioned from higher growth to lower volatility as a member approaches retirement age.

74. Growth assets are generally expected to be more sensitive to climate-related risks than matching assets[footnote 38] but trustees should consider the impact of different climate change scenarios on all asset classes (see Chapter 10). This should be factored into investment decision-making as part of a scheme’s strategic asset allocation – i.e. a top-down integration instead of employing a case-by-case bottom-up approach to climate change.

75. The consideration of climate-related risks, using scenario analysis, may prompt trustees to make changes in their overall strategic allocations to different asset classes or the timeframe over which an agreed transition from growth to matching assets will occur. Trustees may also wish to consider whether certain asset classes and sectors may be expected to benefit from the low carbon transition and may wish to make positive allocations to these and/or make changes to the scheme’s strategic allocation targets (e.g. set targets to increase exposure to certain types of infrastructure, real estate, private equity, etc. within a set timeframe).

76. Trustees may also wish to consider how agreed asset allocation targets and ranges may be impacted by climate change and whether it is necessary to increase ranges around existing asset class allocations to provide more leeway for significant moves towards the upper and lower boundaries during times of high volatility.

6.5. Determining how climate-related risks are incorporated within investment mandates and portfolio construction

77. Having determined their overall strategic asset allocation, trustees must consider the mandates they intend to set for each asset class and the method by which the investments will be made.

78. Because trustees generally do not choose specific investments themselves,[footnote 39] they will usually delegate this power to authorised asset managers.[footnote 40] Whilst some larger pension schemes may invest through a manager who will manage a segregated portfolio of assets on behalf of the trustees, in many cases trustees will invest via pooled funds.

-

Actively managed pooled funds - In relation to the selection of an actively managed pooled fund (or the appointment of an active manager in relation to a segregated mandate), trustees should carefully consider the investment objectives and restrictions under which the manager will make investment decisions. Trustees should identify funds and managers which adopt an investment approach which is aligned with the trustees’ investment beliefs (including engagement and, where applicable, voting policies – see chapter 7). Manager capabilities should be considered carefully (see [6.6] below).

-

Passively managed pooled funds - In relation to passively managed funds, trustees should consider the indices that might be suitable to track. To date, market-capitalisation weighted indices have been used by the majority of pension trustees (particularly in defined contribution schemes). However, these indices usually reflect business-as-usual scenarios and as allocation guidelines for sector diversification, such indices may tend to overweight high carbon sectors (e.g. oil and gas). Trustees may wish to consider the use of alternative indices if they wish to maintain a passive approach. However, in doing so care should be taken as ESG or climate tilted indices may suffer from the same flaw by maintaining overall sector allocations (going overweight for some oil and gas firms to compensate for being underweight in another).

79. In both active and passive funds, risk may be measured relative to specified benchmark indices (either as the basis of a tracking mandate in a passive fund or as a benchmark for performance for an active manager). Trustees should consider that the choice of index may limit the ability to allocate investments in line with trustee investment beliefs containing specific climate goals.

80. Where applicable, trustees may consider a number of strategic actions to reduce identified exposure to risks. These might include:

- a shift in passive investments to low carbon benchmarks rather than tracking a market-capitalisation weighted index;

- making use of funds which take a “factor-based” approach which takes account of climate-related risks rather than tracking an index;

- replacing existing asset managers and/or investing in new priority areas using emerging taxonomies as the basis;

- engagement with asset managers and investee companies on climate-related risks (see chapter 7), collaborating with trustees of other schemes as appropriate.

81. Trustees should establish their preferred approach(es) and consider and document any changes to the trustees’ strategy over time. These should be embedded into the trustees’ governance, investment strategy, risk management and reporting processes.

82. Trustees may also wish to consider the potential strategic options for investing in climate-related opportunities and agree priority areas for further research (including the extent to which the trustees expect their investment consultants or asset managers to investigate and present opportunities in these areas).

6.6. Factoring climate-related risk management capabilities into the selection, review and monitoring of asset managers

83. Having decided upon the mandates they intend to set for each asset class, as well as the method of investment, trustees must consider the process and requirements for the selection, review and monitoring of managers to execute these mandates. This may begin with a review of the climate policies of existing or prospective managers. However, it also requires rigorous due diligence on how these are executed. An assessment of an asset manager’s governance of climate issues and the broader integration of climate impacts into their business strategy is recommended. Appendix 2 provides a number of suggestions for trustees to help them carry out due diligence of asset managers’ capabilities and approach to climate-related risk management.

84. Where schemes invest through a segregated portfolio, whether active or passive, trustees should seek to ensure that their existing managers take an approach to climate which largely aligns with the trustee’s investment beliefs. Where trustees carry out a tender exercise for the appointment of a new manager trustees may wish to consider in addition the prospective managers’ broader investment offering and approach and potentially the expertise, capability and track record of the manager to work with the trustees to develop and deliver solutions aligned with their investment beliefs around climate change.

85. For those schemes investing via pooled funds, whether active or passive, trustees should assess the integration capabilities of managers and approach taken for that fund/strategy; these should cover a range of approaches.

- For active (and factor-based) strategies, it is important to consider how the asset manager applies climate research, data and beliefs to enhance their fundamental analysis (or factor-based approach), and how this is reflected in and complemented by stewardship activities and voting policies (see chapter 7). Trustees should consider the extent to which the approach aligns with their investment beliefs on climate-related issues and delivers on the pension scheme’s strategy. Trustees should assess manager performance against any climate-related mandates, performance benchmarks, or targets set by trustees and consider asking managers for examples of recent cases where climate factors have influenced buy/hold/sell investment decisions.

- For passive strategies, trustees will need to have considered the suitability of market-cap based solutions, against alternative index offerings. When selecting an asset manager to provide these, trustees should in all cases rigorously assess the stewardship activities and voting policies of asset managers. When selecting climate indices, they should seek to ensure that the manager’s approach to climate more broadly, and in particularly its stewardship activities, complement the index solutions on offer.

86. In their monitoring and review of existing managers, trustees may also consider the following strategic actions to hold managers to account on their management of climate-related issues:

- Assess quality of climate-related disclosure provided by managers, preferably against the TCFD recommendations.

- Assess quality of climate-related voting and engagement practices by managers (see chapter 7).

- Require managers to perform and report back on climate scenario analysis on their holdings (see chapter 10).

- Require managers to undergo periodic climate-related assessments (such as carbon auditing or stranded assets).

6.7. Investment consultants (and fiduciary management)

87. In practice, many trustees will rely heavily on their advisers and consultants to provide strategic advice about investment strategies, asset allocation and asset manager selection. Increasingly, trustees will rely on other consultant and adviser services, including manager research and analysis and reporting on asset manager performance. Although trustees will usually have ultimate responsibility for making decisions on these issues, investment consultants’ advice will often be highly influential.[footnote 41]

88. Where trustees have legal duties to consider and address climate risk, consultants will need to have regard to these when providing their advice. However, trustees retain ultimate responsibility to effectively monitor and oversee their advisers.[footnote 42] Trustees are also required to set objectives for their investment consultants.[footnote 43]

89. Trustees should consider setting specific objectives for their investment consultants to:

- advise so as to help trustees develop climate-related strategies (and processes to manage risk) that are aligned with trustees’ investment beliefs on climate-related issues;

- address climate-related risks and opportunities material to the scheme in their investment advice, adapting their core services accordingly (including demonstrating a robust track-record that shows the adviser’s capacity to assess and address the issues); and

- assess the climate-related performance (and resilience to climate related risks) of the schemes’ asset managers and funds and to proactively suggest alternative approaches where these are not aligned with the trustees’ investment beliefs on climate-related issues.

90. Where trustees delegate both the consultancy and implementation of investment strategy to a fiduciary manager, trustees should apply the principles relating to both asset managers and consultants as set out above. Trustees should agree with the fiduciary manager where responsibility lies in relation to each of the actions set out below, depending on the extent to which investment strategy decisions are delegated by the trustees to the fiduciary manager.

Investment strategy

| Suggested trustee actions (and recommended disclosures) – Overall strategy | TCFD |

|---|---|

| 1. Consider, document and disclose whether (and if so, the processes and frequency by which) the trustees (and/or relevant sub-committee) consider climate issues when setting the scheme’s investment strategy. | G(a)(ii) |

| Consider, document and disclose how the trustee board (or relevant sub-committee) will identify climate-related risks/opportunities. Trustees may wish to consider: – what information is needed to evaluate climate-related risks and opportunities, and where can it be sourced; – which risks/opportunities could be material (including existing and emerging regulatory requirements related to climate change); – what process will the trustees adopt for determining size/scope of risks/opportunities at total fund/strategy level, and individual asset class-level. Risks and opportunities should be considered in absolute terms and in relation to the risk appetite of the scheme; – how the trustees have assessed the materiality – the likelihood and impact – of climate-related risks (and opportunities) - e.g. by sector and/or geography, as appropriate; and – the role of the trustee’s investment consultants in bringing climate-related risks/opportunities to the trustees’ attention (and their capacity and expertise to do so). |

S(a)(iii) R(a)(i) R(a)(ii) R(a)(iii) |

| 3. Identify, document and disclose the extent (consistent with the trustees’ investment beliefs) to which and how the trustees intend to factor climate-related risks and opportunities into relevant investment strategies - both at total fund/strategy level, and individual asset class-level. | S(b)(i) S(b)(ii) S(b)(iv) |

| 4. Identify, document and disclose what the trustees consider to be the relevant short-, medium-, and long-term horizons, taking into account: – in a defined benefit scheme, the likely time horizon over which members’ benefits will be paid; and in a defined contribution scheme the likely time horizon over which members’ monies will be invested to and through retirement. |

S(a)(i) |

| 5. Identify, document and disclose the climate-related issues for each time horizon (short, medium, and long-term) that could have a material financial impact - whether transition or physical risk. Examples of risks to cover may include: increased pricing of greenhouse gas emissions; substitution of existing products and services with lower emission alternatives; successful/unsuccessful investments in new technology; moves to more efficient buildings and infrastructure; litigation risk; extreme weather risk. | S(a)(ii) |

| 6. Consider, document and disclose the resilience of the scheme’s strategy, taking into consideration different climate-related scenarios, including a 2°C or lower scenario and how this informs the design of strategies. | S(c)(i) |

| 7. Consider, document and disclose how the trustees’ processes for identifying, assessing, and managing climate-related risks are integrated into the scheme’s risk register and/or integrated risk management approach. Trustees may wish to consider: – their processes for managing climate-related risks, including how they make decisions to mitigate, accept, or control those risks; – their processes for prioritising climate-related risks, including how materiality determinations are made; and – the role of the trustee’s investment consultants in advising on the integration of climate-related issues within an integrated risk management approach. |

R(b)(i) R(b)(ii) R(c)(i) |

| 8. Identify, document and disclose the extent (if at all) to which climate-related issues are included in the trustees’ investment consultant’s strategic objectives.[footnote 44] Trustees may wish to consider (but need not disclose) any similar requirements incorporated into consultants’ investment service agreements. | G(a)(ii) |

| Suggested trustee actions (and recommended disclosures) – Asset allocation and defining asset manager / pooled fund mandates | TCFD |

|---|---|

| 9. Identify, document and disclose how the trustees consider that climate change may impact the scheme’s growth, matching and other portfolios (including the default fund in a DC scheme), taking into account the short-, medium-, and long-term horizons the trustees have identified as relevant. This should include identifying and taking account of areas where the scheme’s (or default fund’s) asset allocation ranges and portfolio structure are expected to evolve in the future. | S(a)(ii) |

| 10. Identify, document and disclose the extent (if at all) to which climate-related risks are embedded/included in strategic asset allocation decisions (and detail any changes resulting from scenario analysis into strategic asset allocation decisions). | S(b)(i) S(b)(iii) S(b)(iv) |

| 11. Consider, document and disclose how scenario analysis is used as a relevant factor in informing asset allocation and decisions to invest in specific asset classes. | S(b)(iii) S(c)(ii) |

| 12. Consider, document and disclose how the scheme’s growth, matching and other portfolios are positioned in relation to the transition to a lower-carbon economy. Trustees may wish to consider: – within different asset classes, the scheme’s exposure to those sectors that are particularly sensitive to transition risk (energy, utilities, materials); and – in relation to passive funds, the extent to which low-carbon transition risks and opportunities are part of the index and whether the trustees have considered any reallocation to alternative index funds or factor-based funds with climate-related weightings. |

S(b)(i) S(c)(i) R(b)(iii) |

| 13. Consider, document and disclose how climate-related risks may impact funds with higher exposure to economic sectors that are concerned with physical assets or natural resources, such as real estate, infrastructure, timber, agriculture and tourism (being the most vulnerable to physical risks of climate change). Trustees may wish to consider: – TCFD’s focus sectors (i.e. Energy; Materials and Buildings; Transportation; and Agriculture, Food, and Forest Products); – regional and sectoral mix to identify and capture the areas where the greatest climate transition is expected to occur; and – exposure to and management of stranded assets. |

S(b)(i) |

| Suggested trustee actions (and recommended disclosures) – Asset manager selection, review and monitoring | TCFD |

|---|---|