Draft statutory guidance: Disclose and Explain asset allocation reporting and performance-based fees and the charge cap

Updated 30 January 2023

Background

About this Guidance

1. The Occupational Pension Schemes (Administration, Investment, Charges and Governance) (Amendment) Regulations 2023 (“the 2023 Regulations”) introduce new requirements for trustees and managers of certain occupational pension schemes.

2. For the first scheme year that ends after 1 October 2023, trustees and managers of relevant[footnote 1] occupational pension schemes, are required to disclose their full asset allocations of investments from their default funds. Where a relevant scheme is a qualifying collective money purchase scheme[footnote 2], trustees must disclose its full asset allocations of investments as such schemes will not have default funds[footnote 3]. This information must be recorded in the annual chair’s statement and is to be published alongside other relevant parts of the statement on a publicly accessible website.

3. This guidance is intended to assist trustees and managers of relevant occupational pension schemes in the calculation and format of asset allocation disclosures.

4. From 6 April 2023, the 2023 Regulations also introduce an option for trustees and managers to enter into investment arrangements that include performance-based fees, in the knowledge that they will be able to exempt the performance-based element of the fee from their charge cap calculations. The regulatory charge cap limit is 0.75% which applies to the default funds of occupational pension schemes used for automatic enrolment and to qualifying collective money purchase schemes.

5. The 2023 Regulations attach conditions on what qualifies as a performance-based fee structure for the charge cap exemption. This guidance provides support on the broad range of performance-based fee structures that exist and an understanding of the merits of these. It does not provide an exhaustive list of what performance-based fees do or which fee structures are considered most appropriate. Trustees and managers must have regard to this guidance but should also seek their own independent professional and legal advice before entering into any agreement which involves the use of performance-based fees.

6. This guidance, issued by the Secretary of State for the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP), should be read in tandem with the 2023 Regulations.

7. Existing legislation places duties on trustees in relation to scheme administration and governance and trustees must ensure they are familiar with these duties. Trustees should also refer to The Pensions Regulator (TPR) codes of practice and guidance on the standards expected when complying with their legal duties and seek their own independent legal advice.

Who this guidance is for?

8. This guidance is for trustees and managers of relevant occupational pension schemes who, regardless of size, must comply with the requirements to report their asset allocation in accordance with regulation 25A (assessment of asset allocation) of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 (“the Administration Regulations”[footnote 4]), and publish this information under regulation 29A of the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 (“the Disclosure Regulations”[footnote 5]), as amended by the 2023 Regulations.

9. This guidance is also for trustees and managers of occupational pension schemes which provide money purchase benefits who wish to take up the option to exclude ‘specified performance-based fees’ from the regulatory charge cap set at 0.75% p.a. A specified performance-based fee is defined in Regulation 2 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 (“the Charges and Governance Regulations”[footnote 6]) and must be disclosed in accordance with Regulations 23 and 25 of the Administration Regulations and published in accordance with Regulation 29A of the Disclosure Regulations, as amended by the 2023 Regulations.

10. The guidance is not relevant to:

- an executive pension scheme;

- a relevant small scheme;

- a scheme that does not fall within paragraph 1 of schedule 1 (description of schemes) to the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013;

- certain public service pension schemes;

- a scheme which provides no money purchase benefits other than benefits which are attributable to additional voluntary contributions.

Legal status of this guidance

11. This statutory guidance is produced under the powers in:

- Paragraph 1(2)(b) of Schedule 18 to the Pensions Act 2014,

- Paragraph 2(2)(b) of Schedule 18 to the Pensions Act 2014,

- Section 113 (3A) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993.

Compliance with this Guidance

12. TPR regulates legislative compliance for all occupational pension schemes and publishes guidance on the roles of employers and trustees. Neither the Government nor TPR can provide a definitive interpretation of legislation, which is a matter for the courts.

13. Where schemes do not comply with a relevant legislative requirement TPR can take enforcement action depending on the nature of the breach. This could include a financial penalty.

14. Enforcement of the requirements contained in Part V of the Administration Regulations, including the production and content of the chair’s statement, is provided for in Part 4 of the Charges and Governance Regulations.

Expiry or review date

15. This guidance will be reviewed, as a minimum, every three years, from the date of first publication, and updated when necessary. When the guidance is reviewed, established and emerging good practice and user testing may be included.

Disclose and explain asset allocation disclosure

16. The 2023 Regulations require trustees or managers of relevant occupational pension schemes to disclose the percentage of assets allocated in the default arrangement to specified asset classes. Where a relevant scheme is a qualifying collective money purchase scheme, this breakdown is required in respect of the asset classes held by the scheme.

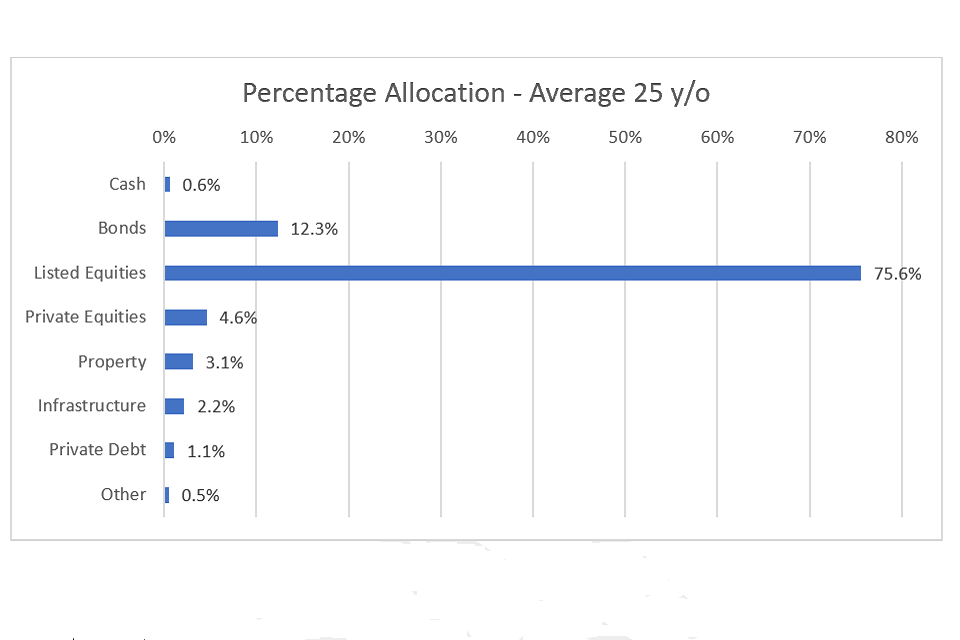

17. Publication of asset allocation data will be an important step towards transparency, standardisation and comparability across the occupational pensions market. It is important that members have access to all relevant information surrounding the investments being made using their contributions and the outcomes these investments could have on their future retirement. Public disclosure would also enable trustees, employers and members to compare the value for money differing asset allocations bring to members when read alongside the net returns on investments also published in the chair’s statement.

18. The information on asset disclosure must be stated in the annual chair’s statement for the first scheme year ending after 1 October 2023, be updated annually, and be published alongside other relevant parts of the statement on a publicly available website.

19. This section of the guidance is designed to assist schemes in the reporting of their asset allocations. For illustration purposes, we suggest how this information could be displayed in the required disclosures.

Scope

20. The 2023 Regulations require all relevant schemes providing money purchase benefits or collective money purchase benefits to disclose and explain their asset allocation in their annual chair’s statement. This includes any hybrid scheme which offers money purchase or collective money purchase benefits.

21. Where these disclosures relate to a default arrangement within a relevant scheme, a “default arrangement”[footnote 7] is where contributions are placed without the member having expressed a choice as to where the contributions are allocated, or in which 80% or more of members have actively chosen to invest. Some exceptions apply (for example, arrangements relating solely to AVCs). Legal requirements applicable to default arrangements differ depending on whether they are used by employers to comply with their duties under automatic enrolment. The legal definition of “default arrangement” is set out in regulation 3 of the Charges and Governance Regulations, with the modifications set out in regulation 1 of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005[footnote 8].

22. Where a scheme has more than one default arrangement, trustees should look to disclose the asset allocation for each default arrangement, regardless of how or when they became default arrangements, where members are still invested in the fund at the end of the scheme year, so that members invested outside of the main default are not disadvantaged.

23. If a qualifying collective money purchase scheme is divided into sections[footnote 9] (or if there is a qualifying collective money purchase section or sections within a scheme) then the asset allocation within each section’s fund should be reported on separately.

Asset allocation disclosure

24. The 2023 Regulations require trustees to disclose in their annual chair’s statement the percentage of assets allocated to each of the following asset classes in their default arrangement, or scheme if a qualifying collective money purchase scheme:

a. cash

b. bonds - creating or acknowledging indebtedness, issued by a company, or by the UK Government

c. listed equities - shares listed on a recognised stock exchange

d. private equity (that could include venture capital and growth equity) - shares which are not listed on a recognised stock exchange

e. infrastructure - physical structures, facilities, systems, or networks that provide or support public services including water, gas and electricity networks, roads, telecommunications facilities, schools, hospitals, and prisons

f. property/real estate - property which does not fall within the description in paragraph (e)

g. private debt/credit - instruments creating or acknowledging indebtedness which do not fall within the description in paragraph (b)

h. other - any other assets which do not fall within the descriptions in paragraphs (a) to (g).

Asset class definitions

25. Explanations of the asset classes that must be disclosed in a clearly identifiable manner are provided below. Further detail is then included on sub-asset classes that schemes may wish to also disclose to help member understanding:

- Cash: Cash and assets that behave similarly to cash e.g., treasury bills. This only includes invested cash and not cash held in a bank account or accounting values such as net current assets.

- Bonds: Loans made to an issuer (a government or a company) which undertakes to repay the loan at an agreed later date. The term refers generically to corporate bonds or government bonds (gilts). However, in common parlance, the term bond is more likely to be used with reference to a corporate bond, while the term gilt refers exclusively to UK government investments, including index-linked gilts. Schemes must disclose the percentage of their default asset allocation, or asset allocation if a CMP scheme, held in corporate and UK government bonds/gilts. Schemes may wish to provide further information about specific types of bonds they invest in.

Where applicable, schemes could provide further detail on the allocation to:

- Fixed interest gilts

- Index-linked gilts

- Investment grade bonds

- Non-investment grade bonds

-

High yield bonds.

- Listed equities: Shares in a company which are bought and sold on a stock exchange. Owning shares makes shareholders part owners of the company in question and usually entitles them to a share of the profits (if any), which are paid as dividends.

Where applicable, schemes may wish to provide further detail on their listed equity regional allocations as follows:

- UK equities

- Developed market equities (excluding UK)

-

Emerging markets

-

Private equity: Unlisted equities which are not publicly traded on a stock exchange. Private equity funds can encompass a broad range of investment styles. Schemes should provide a sub-asset allocation to show members the nature of their exposure. This may include:

- Venture capital: Private equity generally for small, early-stage business that are expected to have high growth potential but with access to other forms of financing.

- Growth equity: investment in a relatively mature company that is going through a transformational event in their lifecycle, with potential for growth

- Buyout or leveraged buyout funds: Invest in more mature businesses, often taking a controlling interest.

Where applicable, schemes may wish to provide further detail on their private equity investments as follows:

- Proportion of UK-based companies invested in

- Proportion of non-UK based companies invested in

-

Proportion in particular sectors

-

Example: technology, life sciences, climate-based solutions, sustainable energy, etc.

- Whether invested through a pooled fund / collective investment scheme / Long Term Asset Fund etc.

-

Property: Real estate.

-

Freehold, (In Scotland, ‘heritable’) or leasehold property schemes may wish to provide narrative to help members understand the types of property that have been invested in (such as offices, retail, etc.) and the nature of that investment (such as long-term leases, short term development etc).

- Infrastructure: physical assets that support functioning society such as water, gas and electricity networks, roads, telecommunications, schools, hospitals, prisons etc.

Schemes should state their infrastructure investment (UK and/or overseas) under this asset class category, even if that exposure is through one of the other asset classes listed in this guidance.

Schemes may wish to provide a breakdown of their infrastructure assets by:

- Economic infrastructure – includes investments in renewable energy, utilities, transport, and telecommunications.

- Social infrastructure - mainly involves public health, education and building, construction, and maintenance.

Schemes may wish to provide further details of the type of infrastructure assets presently held and how they may be developed over the life of the investment, this could be aided using a case study.

- Private debt: non-bank lending to companies, not issued or traded publicly.

Private debt can encompass a broad range of investment styles, schemes may wish to provide a sub-asset allocation to show the reader of the disclosures the nature of their exposure. This could include:

- Seniority of debt

- Geography

-

Sector

- Other: Assets which are not considered to be part of any of the asset classes described above.

The total asset allocation should add up to 100%.

Importance of look-through for asset allocation disclosure

26. Where schemes use funds that allocate to more than one asset class, trustees should look through the fund and state the underlying asset allocation of each fund vehicle. For example, a multi-asset fund may be classed as a listed equity overall, but when you look through to the underlying assets, there is exposure to private equity, infrastructure, private debt etc. Examples of such funds can include funds that are often categorised or named as managed, balanced, multi-asset or diversified funds.

27. There are a range of legal fund structures that determine the ownership of the underlying assets within a fund. For example, underlying assets may belong to the trustees, or the trustees may own units of the fund. The value of those units is closely linked to the value of the pool of underlying assets, rather than just the fund overall.

28. Trustees must look through the ownership structure of the fund vehicle and state the asset allocation relating to the economic exposures of the underlying asset classes[footnote 10].

29. Where schemes use assets that do not use a physical allocation, such as derivatives, trustees should aim to state what their synthetic allocation would provide in physical asset terms. Where that is not possible, schemes should provide an explanation to help members understand the situation but class the assets as “other” so that the total asset class percentage remains at 100%. The nature of such synthetic exposures can be complex and may not clearly transcribe into the specified asset allocation list where the total of all assets is expected to sum to 100%.

30. Schemes should only state the exposure to their invested assets and should not include non-invested assets, such as cash at bank or accounting values such as net current assets.

Age-specific disclosures

31. Relevant occupational DC schemes should use age profiles as part of the default asset allocation disclosure to represent the different asset allocation phases in accumulation. We would suggest that schemes may wish to consider using ages that are consistent with existing disclosures. For example, we advised in ‘Completing the annual Value for Members assessment and Reporting of Net Investment Returns’ guidance[footnote 11], age specific asset allocations for savers aged 25, 45, 55 years. We would now also advise using “1 day prior to State Pension age” as a further age cohort for disclosure to capture asset allocations close to retirement age and just before decumulation begins, when de-risking is more prevalent.

32. Such an approach is not expected in collective money purchase schemes given their collective nature.

33. The table below provides an example as to how schemes could report their asset allocation by the four recommended age cohorts. The example is presented in both table and graph form since disclosure of this kind must be accessible to members as well as industry experts. To note, the examples provided below act as an illustrative representation of a pension scheme’s asset allocation and does not represent DWP’s understanding of best practice or attempt to represent any particular scheme in reality.

Composition of returns & example presentations of data

| Asset class | Percentage allocation – average 25 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 45 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 55 y/o (%) | Percentage allocation – average 1 day prior to SPA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cash | 0.6 | 6.3 | 31.6 | 54.3 |

| Bonds | 12.3 | 39.3 | 37.2 | 38.1 |

| Corporate bonds | 8.1 | 22.6 | 18.7 | 18.4 |

| Government bonds | 2.7 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 16.2 |

| Other bonds | 1.5 | 7.3 | 6.2 | 3.5 |

| Listed equities | 75.6 | 43.7 | 22.9 | 5.5 |

| Private equity | 4.6 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 0.6 |

| Venture capital / growth equity | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 |

| Buyout funds | 3.7 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Property | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.4 | 0.3 |

| Infrastructure | 2.2 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 0.4 |

| Private debt | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 |

| Other | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

34. The graph below is an example of how schemes may like to disclose the asset allocation for an individual age cohort.

An example of how schemes may like to disclose the asset allocation for an individual age cohort.

Reporting Period

35. Schemes should calculate and report the allocation of assets as part of their annual chair’s statement. The first chair’s statement to include this asset allocation disclosure is for the first scheme year ending after 1 October 2023. This information must also be published alongside other relevant parts of the statement on a publicly available website.

Averaging

36. If a scheme’s asset allocation has fluctuated or changed significantly throughout a scheme year, trustees may wish to use averaging to represent their allocation. This could be done by selecting four valuation points throughout the year, no closer than three months apart, at which the percentage allocation to each asset class is calculated. A mean average of these percentages could then be calculated and disclosed as an average from across the scheme year.

Performance-based fees and the charge cap

Applies to default funds of occupational money purchase pension schemes used for automatic enrolment or collective money purchase benefits.

37. Regulation 2 of the 2023 Regulations amends the Charges and Governance Regulations to provide the option for schemes to exclude ‘specified performance-based fees’ (paid out of an investment fund in which a pension fund invests) from the list of charges that fall within the regulatory charge cap limit of 0.75% p.a.

38. Specified performance-based fees are considered to be designed so that the fee is incurred when a fund’s performance exceeds a pre-agreed investment return. This section of the guidance is designed to assist schemes determine which criteria must be met for a specified performance-based fee to be considered outside the scope of the charge cap.

39. Schemes should be aware that the exemption from the charge cap does not apply to fees that are not related to performance. This includes annual fixed management fees or other charges that may form part of an overall fee agreement where performance-based fees are also present. Schemes must continue to include all other fees within their charge cap calculation.

40. Schemes must ensure that any specified performance-based fees relating to funds that their scheme has invested in are disclosed in the annual chair’s statement. This information must also be published on a publicly available website. This disclosure is to ensure full transparency to members.

41. The provision allowing specified performance-based fees to be excluded from the cap intends to make it easier for schemes to be able to access a broader range of asset classes where performance-based fees are prevalent. It is intended to incentivise schemes and fund managers to agree to terms that link payment of performance-based fees additional or increased to the net benefit the scheme members receive. This should provide schemes with greater flexibility and freedom to enter into performance fee arrangements where trustees agree this is in the financial interests of members.

42. From the outset schemes should consider whether the additional incentive provided by a specified performance-based fee to a fund manager is expected to lead to additional value to members that outweighs the expected cost to members that could not be achieved through a flat fee-based structure.

43. In addition to this guidance, schemes should also seek professional advice on their investments where performance-based fees may be incurred.

44. This guidance does not cover the strategic or operational aspect of illiquid assets. The operational aspect includes a range of issues including valuation, member flows, treating members fairly. Schemes should seek professional advice on these areas as part of their evaluation of how funds with performance-based fees will form part of their scheme’s overall investment arrangements and the practical challenges to work through.

What are performance-based fees?

45. Performance-based fees aim to align the financial interests of the investment manager and investors, in their joint aspiration for profit. They are commonly associated with investments where there is a high level of involvement by the fund manager in executing the fund’s investment strategy and the management of its underlying assets.

46. Performance-based fees are often found in privately traded assets such as private equity, venture and growth capital, and private credit. Such funds may also invest in publicly traded assets. A performance fee can therefore be applied to any asset class or a fund that blends multiple asset classes.

47. The structure of performance-based fees varies. The most common structure being the combination of a fixed annual management fee linked to the size or value of the committed capital and paid regardless of return, and a performance-based element which is payable upon investment returns exceeding a certain “hurdle rate”. To note, it can also be possible to invest in privately traded assets just through a fixed management fee structure.

48. Schemes should take professional advice from a competent advisor on performance-based fees when evaluating any investments. For those with performance-based fees, schemes should consider these in the context of other investment opportunities, their fee structures and the operational implications of including those types of investments in the scheme’s investment arrangement. Schemes should also consider the extent to which there may be scope to work with fund managers to develop terms that best serve member outcomes.

Specified performance-based fees

49. The 2023 Regulations determine that only a performance-based fee that meets the following criteria can be excluded from the charge cap calculation:

“Specified performance-based fees” means fees, or any part of those fees, which are:

(a) payable by the trustees or managers of a pension scheme to a fund manager in relation to investments managed by the fund manager for the purposes of the scheme;

(b) calculated only by reference to investment performance, whether in terms of the capital appreciation of those investments, the income produced by those investments or otherwise;

(c) only payable when:

(i) investment performance exceeds a pre-agreed rate, which maybe fixed or variable; or

(ii) the value of those investments exceeds a pre-agreed amount;

(d) calculated over a pre-agreed period of time; and

(e) subject to pre-agreed terms designed to mitigate the effects of short-term fluctuations in the investment performance or value of those investments.”

Return on investments

50. The return of the fund should be derived from realised returns from disposal or the change in valuation of the fund’s underlying assets and any income that those assets have produced. The calculation of the return will be in accordance with the fund’s investment vehicle and the regulatory guidelines for that fund vehicle, with further detail specified in the terms of the fund.

51. Due diligence by the trustees or manager of the scheme and their advisers should include the method used to calculate the return. We would expect the fund authorisation to require verification of returns.

Pre-agreed rate or amount

52. Trustees or managers of the scheme should agree with the fund manager the agreed rate or amount which the investment must reach or be realised i.e. the asset is sold before the fund manager is entitled to a performance-based fee. Where schemes invest in a fund alongside (and on the same or substantially the same terms as) other third-party investors not linked to the fund manager, there is no need for the performance-based fee to be separately negotiated by the scheme, as long as the scheme considers that the performance-based fee is appropriate in the light of the 2023 Regulations and this guidance.

53. The pre-agreed rate or amount is commonly, but not exclusively, referred to as a hurdle rate. A hurdle rate can be:

a. An agreed rate – level of outperformance above a benchmark/index before a performance-based fee is paid out. This could be a variable rate, such as a published financial performance index that will vary based on the index’s published constituents or may consist of a blend of more than one index or (the most commonly encountered hurdle) may simply be a compound rate of interest applied to net investment in a fund from time to time.

b. An amount – this could be a fixed amount. This is commonly a fixed percentage amount, or a series of fixed percentage amounts.

54. Performance-based fees only become due when that pre-agreed rate or amount is exceeded.

55. Before they agree with the fund manager to the investment proposition, schemes must have given full consideration to how the rate or amount directly links to the net benefit return scheme members could receive.

56. Schemes should also consider if the rate is appropriate to the type of assets being invested in, the fund’s strategy and the economic outlook and the level of return that might be achieved through similar funds that do not charge performance-based fees.

57. The rate or amount will influence how the fund manager is incentivised, so for example a high rate or amount may incentivise the fund manager to take more risk to try and achieve that hurdle e.g., a 15% hurdle rate would mean that the manager needs to deliver performance above that level before the performance-based fee commences, whereas a 5% hurdle rate would incur the performance-based fee at lower levels of performance.

58. To compare a hurdle rate of 5% and 15% would require details of how the fund invests, as higher return targets typically require more risk to be taken which implies a greater chance of high returns as well as the potential for high losses. The appropriate hurdle rate or amount is for the trustee or manager of the scheme to agree having considered the options outlined by the fund manager, considered these in context of the fund’s peer group, with consideration for the scheme’s overall investment strategy and on taking professional advice.

59. Schemes should engage with the fund manager and their advisers to consider their preferred structure for the agreed rate or amount of return, the level that it is set at, and may wish to look at scenarios to ensure that the level is understood in context of potential performance-based fees paid and their impact on member outcomes.

When performance-based fees are measured

60. The specified performance-based fee will be calculated by the performance over a pre-agreed period of time. This pre-agreed period of time, or measurement period, is a pre-determined time period between two consecutive points over which performance-based fees are accrued. For some funds, the period may be that between two consecutive valuation points (for example, a fund may compare Net Asset Value figures from time to time to calculate investment returns and the proportion of that which makes up the performance-based fee). Whereas for others, such as closed-ended funds, it may be the time between the drawdown of funds (and there may be more than one such date) and a distribution or other payment by the fund. Note that the measurement period may differ to the payment period, covered in the next section.

61. The measurement period can be set to reflect the characteristics of the underlying assets given the assets are often illiquid. By their nature they are not listed on an exchange and so there is not a readily available quoted price, therefore measurement periods could be monthly, quarterly, annually, or longer. However, performance-based fees could still apply to funds that are valued on a daily basis and fund managers may devise fund types and valuation periods that blend the requirements of investors, such as DC schemes, with the characteristics of the invested assets.

62. An example of an investment that could have a valuation period of annual or longer, might be a large national infrastructure project that will take many years to design and build before it can then deliver utility. An example of an investment with more frequent valuations, which could be weekly or monthly, could be short term credit provided to small and medium businesses.

63. Schemes should consider the appropriateness of the proposed valuation frequency with the fund manager and their advisers.

64. Independent asset valuations - Performance-based fees are often applied to assets which require specialist valuation. It is recommended that trustees ensure that there is independence in the valuation, such as from the use of a third-party valuer, or an independent audit.

When performance-based fees are paid

65. The payment period, also sometimes known as the crystallisation period, is the timing point at which the fund manager is paid any performance-based fees that they are due.

66. The payment period is often set to coincide with when underlying physical assets are developed and then sold, or credit assets mature, as that relates to the fund’s cashflow and an appropriate time at which payments can be made.

67. However, payment is not always made to the fund manager as cash, they could for example be paid with units of the fund in question, taken from the investor’s unit allocation. This can alleviate the need to have cash available over the life of fund, with the manager only receiving cash at such time as the underlying fund assets are sold.

68. To note, the payment period will not always align with the valuation period. The trustees should work with the fund manager to develop a suitable period over which performance can be measured, and over which payment is then made.

Fairness for members

69. A common issue that is often raised is that good performance must be earned before managers are then paid their performance-based fee. However, if a member joins at the end of the good performance, they suffer the higher fee but have not benefited from the good performance. Trustees should work with fund managers and other professionals to ensure that the spread of cost/benefit is fair for all scheme members.

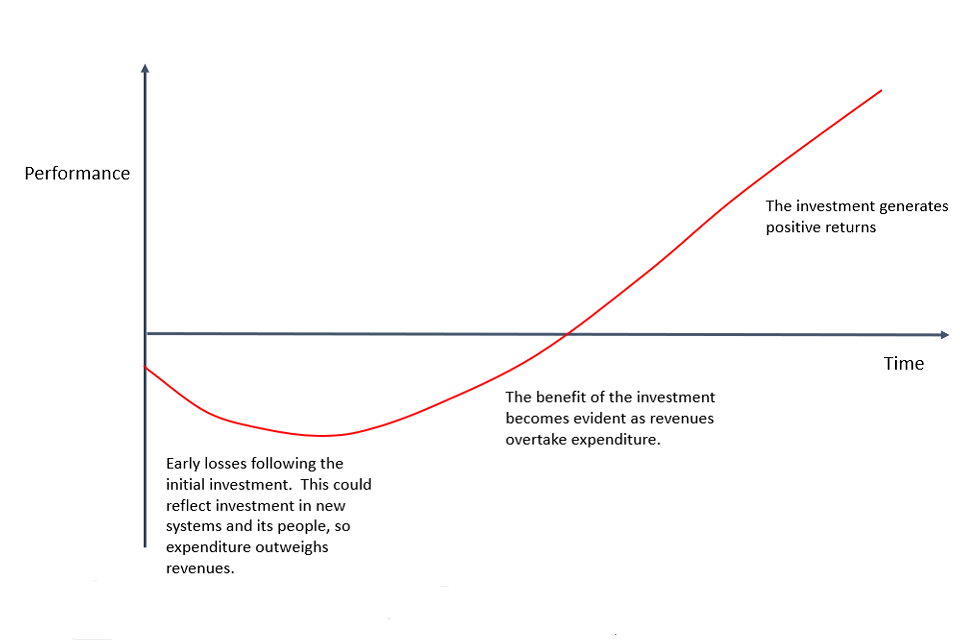

Fund journey example

Consider an example of a private equity investment where the returns can be characterized by their profile which is often called the “J-curve” effect. This J curve effect is being used as an example to illustrate member fairness, it is not an endorsement of J curve performance profiles or their use, for example, in DC schemes, the merits of which would have to be considered strategically by trustees and their advisers.

Fund journey example

Consider a scheme that invested over the full J curve.

- A member that was in the scheme before the investment was made, but left just after the initial investment, would have suffered the costs of the investment but not enjoyed the benefits of the performance that followed.

- A member joining at the bottom part of the J curve would have missed the worst of the poor returns and benefitted from the positive performance.

- A member that was invested throughout the J curve would have experienced performance midway between the two previous members.

Trustees should be aware of the potential profile of returns that may lead to material differentials in outcomes by participation periods of members. Some assets can be more prone to this pattern of returns, with mitigations such as the scheme selecting its investment period or making several overlapping investments.

Another differential based on member participation is if the payment period differs to the valuation period. For this J curve example, if there are performance-based fees that are paid with a delay to the valuation point, a member could join near the end of the investment (the right-hand side of the J curve) and may have to pay those fees without having benefitted from the returns.

This J curve example is not representative of the timing or pattern of returns of all funds with performance-based fees but is illustrative of the type of challenges they can present, compared to funds with just fixed management fees. The potential for high expected returns and so high fees, particularly compared what many money purchase schemes use as the staple of their default funds, could lead to large differentials in member outcomes, with regards to impact on member outcomes versus fees paid.

As signalled above, trustees will need to seek professional advice on how the measurement and payment of performance-based fees is fair for all scheme members invested.

Volatility of returns and performance-based fees

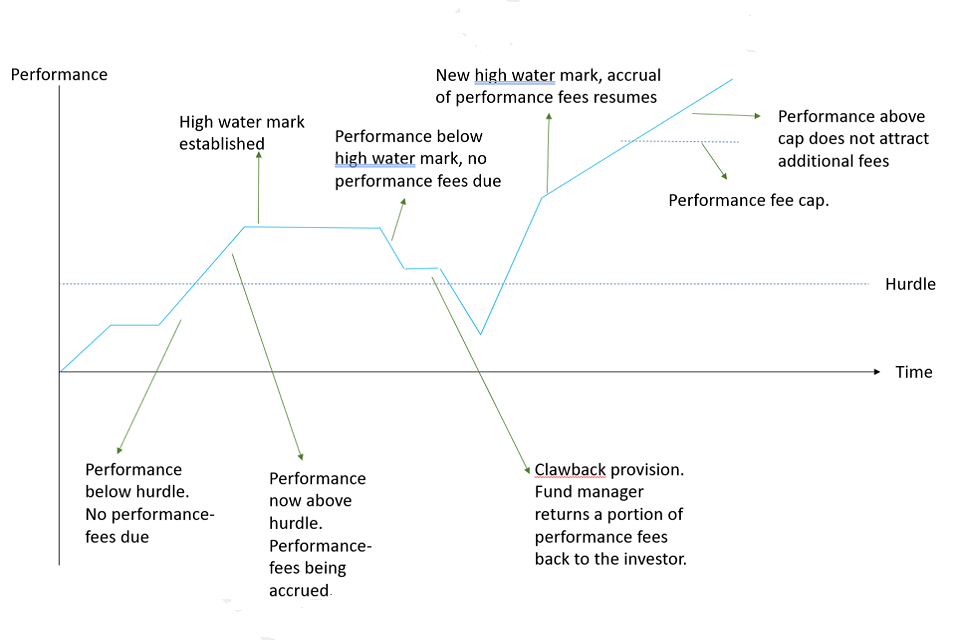

70. Specified performance-based fees structures should include mechanisms that offer protections to pension schemes and their members. This is so fund managers are not taking excessive risk or being paid twice for the same level of performance or for performance which turns out to be impermanent. The 2023 Regulations require trustees and managers of schemes work with their advisers and the fund manager to ensure they put in place a fee structure mechanism which provides appropriate safeguards for members. Some of the more common mechanisms that can provide protection are provided below, but this is not an exhaustive list.

- High water mark - a protection mechanism for investors to ensure that the fund manager only receives performance-based fees for generating additional levels of performance. This avoids an investor paying performance-based fees repeatedly on the same level of performance during periods of volatility.

- ‘Whole fund’ structures – in certain closed-ended structures the manager is only entitled to performance-based fees to the extent that all the fund’s investments, when taken as a whole and once realised, provide sufficient returns to allow investors to receive back all their initial investment, plus any hurdle or similar threshold. This prevents the manager retaining a reward for early successful investments where those are then followed by later losses that cumulatively exceed the extent of the fund’s initial gains.

- Clawback mechanism – this is a provision that requires fund managers to pay back previously received performance-based fees (net of tax) if the fund manager subsequently underperforms in future time periods. Trustees may consider that this helps to align member and fund manager interests and provide some mitigation should a period of poor performance ensue after previous gains. Such mitigation is only in respect of fees. The capital that has been invested is still at risk.

- Escrows – performance-based fees to which the manager is entitled may be placed into an escrow account for a period of time and only become accessible to the manager once the fund has achieved a certain level of consistent or permanent performance.

- Caps – there can be a cap on the total amount of performance-based fees that could be due. Trustees may decide that a cap would help ensure that the fund manager’s incentive for performance was in line with their expectations, and not far beyond which could entail taking more risk than the trustees would be expecting. Trustees may decide that a cap also helps when presenting performance-based fees to members, assuring members as to the total amount of fees that could be due. At the same time, a cap on performance-based fees may also disincentivise the fund manager to expend effort on generating further strong performance once the cap has been reached.

Performance-based fee structure example

71. The example below illustrates how some of the performance-based fee mechanisms may be combined and work together. Trustees and managers of schemes should take appropriate advice on how the fees can be applied.

Performance-based fee structure example

Pro-rated and smoothing performance-based fees

72. As a result of the introduction of specified performance-based fees that can be excluded from the charge cap, the options allowing schemes to pro-rate the effects of performance-based fees for part year members and smoothing fees over multiple years for the purposes of the charge cap, that can be currently applied in accordance with regulations 7, 7A, 8 and 8A of the Charges and Governance Regulations[footnote 12] are to be repealed.

73. However, with respect to the smoothing option the 2023 Regulations do allow for any schemes that have applied this to continue using it up to the date which is 5 years after the end of the first charges year in which the trustees or managers first chose to rely on the smoothing provisions.

Disclosure reporting

74. The 2023 Regulations require that the amount of any specified performance-based fees incurred in relation to each default arrangement (if any) or, in the case of a qualifying collective money purchase scheme, the scheme during the scheme year, is stated as a percentage of the average value of the assets held by that default arrangement or collective money purchase scheme during the scheme year. This information must be included in the annual chair statement and made available on a publicly available website.

75. Schemes should consider carefully how they present the amount of performance-based fees in the annual chair’s statement as there may be periods when their magnitude differs considerably to the other fees paid on their default fund or other industry default funds. There may also be periods when the year-on-year changes are very significant.

76. Schemes may want to consider supplementing the regulatory disclosures with detail to add context to performance-based fees, such as,

a. The application of the hurdle rate, and additional mitigations used that make up the fee structure used such as high-water marks, caps, clawback etc.

b. A timeline of how performance-based fees are measured and paid.

77. Additional information may also include for example, previous years’ information, and additional narrative to relate to the fund’s performance and how that is expected to impact member outcomes.

78. Depending on the performance-based fee timing, schemes could also consider providing additional disclosure at periods more frequently than annually. This could be relevant if that aligns with measurement or payment periods, and if there may be a desire to disclose information in relation to fair treatment of members that may join or leave a scheme, or alter contributions, part way through a scheme year.

79. This additional information could take the form of literature or interactive graphics to help members understand how performance-based fees have been considered by their trustees, including such scenarios of fees that are in the disclosures in question.

Fund sheets

80. We suggest that this further information on performance-based fees could be reported to members in the normal course of reporting, for example by making use of guides and fund sheets. This would involve trustees working with fund managers to prepare a document that can be shared with members that could include examples of the types of assets that the fund will invest in and how the fund manager will manage those assets, to help members relate the activity of the fund manager to the potential fees becoming due.

81. We suggest that any fund sheet produced is updated annually, so that it can be used to explain performance-based fees that have been incurred, in context of the stage of the fund’s life cycle.

-

A relevant scheme is an occupational pension scheme which provides money purchase benefits or collective money purchase benefits (excluding money purchase benefits solely related to Additional Voluntary Contribution (AVC) arrangements), which is not a scheme with only one member, a relevant small scheme or an executive pension scheme as defined ↩

-

As defined in regulation 3A of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015. Where there is sectionalisation, the information on the assets held must be broken down by section. ↩

-

Collective money purchase schemes are commonly known as collective defined contribution schemes. ↩

-

See The Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996 - legislation.gov.uk ↩

-

See The Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 - legislation.gov.uk ↩

-

See The Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 - legislation.gov.uk ↩

-

See The Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 - legislation.gov.uk ↩

-

See The Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005 - legislation.gov.uk ↩

-

This sectionalisation might occur where it has been decided to adjust the design of the collective benefits offered to automatically enrolled employees going forward. The old section and new section would continue to be considered qualifying collective money purchase schemes and subject to these disclosure requirements. ↩

-

As defined in the Occupational Pension Schemes (Administration, Investment, Charges and Governance) (Amendment) Regulations 2023, Amendment of the Occupational Pension Schemes (Scheme Administration) Regulations 1996, paragraph 25A (4). ↩

-

See paragraph 33 of Completing the annual Value for Members assessment and Reporting of Net Investment Returns - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk) ↩

-

See The Occupational Pension Schemes (Charges and Governance) Regulations 2015 - legislation.gov.uk ↩