Statutory guidance: Governance and reporting of climate change risk: guidance for trustees of occupational schemes

Updated 17 June 2022

Draft statutory guidance proposed to be issued pursuant to section 41A(7) and 41B(3) of the Pensions Act 1995 and section 113(2A) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993

This draft Guidance does not have any effect until the Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) (Amendment, Modification and Transitional Provisions) Regulations 2022 come into force.

Part 1: Background

About this Guidance

1. From 1 October 2021 the Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) Regulations 2021[footnote 1] (“the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations”) introduced new requirements relating to reporting in line with the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations, to improve both the quality of governance and the level of action by trustees in identifying, assessing and managing climate risk.

2. The Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) (Miscellaneous Provisions and Amendments) Regulations 2021[footnote 2] (“the Miscellaneous Provisions Regulations”) have amended the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013[footnote 3] (“the Disclosure Regulations”) to introduce disclosure requirements relating to the reports required by the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations.

3. From 1 October 2022, the Occupational Pension Schemes (Climate Change Governance and Reporting) (Amendment, Modification and Transitional Provision) Regulations 2022 introduce new requirements to be met by trustees of schemes in scope of the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations, by making amendments to those Regulations, in relation to the calculation and reporting of a metric which gives the alignment of the scheme’s assets with the climate change goal of limiting the increase in the global average temperature to 1.5˚C above pre-industrial levels.

4. In complying with the requirements in Part 2 of and the Schedule to the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations trustees are required to have regard to guidance issued from time to time by the Secretary of State[footnote 4].

Legal status of this Guidance

5. This Guidance is Statutory Guidance produced under sections 41A(7) and 41B(3) of the Pensions Act 1995 (“the 1995 Act”) and section 113(2A) of the Pension Schemes Act 1993 (“the 1993 Act”), unless otherwise stated.

6. The guidance on trustee knowledge and understanding included at Part 2 paragraphs 33-41 is not Statutory Guidance but is intended as best practice. Trustees are not required to have regard to it, but are encouraged to do so.

Expiry or review date

7. This Guidance will be reviewed at a minimum of every 3 years from the date of first publication (8 June 2021), and updated when necessary.

8. When we review the Guidance we will consider, for possible inclusion, lessons from established and emerging best practice in the identification, assessment and management of climate risks and opportunities and in the production of TCFD reports (see paragraph 14), and improvements in data quality, modelling capabilities and completeness.

Audience

9. This Guidance is for trustees who are subject to the requirements in Part 2 of and the Schedule to the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations, as described below. Once the requirements are fully phased in, this will include trustees of both money purchase and non-money purchase schemes with £1bn or more in “relevant assets”. It will also include trustees of all authorised master trusts and authorised schemes (once established) providing collective money purchase benefits, in both the accumulation and decumulation phases.

10. Trustees of schemes whose relevant assets are £5bn or more at the end of their first scheme year ending on or after 1 March 2020 will be subject to the climate change governance requirements from 1 October 2021 or, if later, from the date they obtain audited accounts in relation to that scheme year (in this Guidance we refer to this as the “first wave”)[footnote 5].

11. Trustees of authorised master trusts will be subject to the governance requirements from 1 October 2021 or, if later, the date the trust becomes authorised. Trustees of authorised schemes (once established) providing collective money purchase benefits will be subject to the governance requirements from the date the scheme is authorised.

12. Trustees of schemes which are not captured by the first wave and whose relevant assets are £1bn or more at the end of their first scheme year ending on or after 1 March 2021 will be subject to the governance requirements from 1 October 2022 or, if later, the date they obtain audited accounts in relation to that scheme year (in this Guidance we refer to this as the “second wave”).

13. Trustees of schemes captured by neither the first nor second waves whose relevant assets are £1bn or more at the end of a scheme year which falls on or after 1 March 2022 will be subject to the governance requirements from the beginning of the scheme year which is one scheme year and one day after the scheme year end date when the relevant assets were £1bn or more.

14. Trustees must produce and publish a report (“TCFD report”), containing the information required by Part 2 of the Schedule to the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations, within 7 months of the end of any scheme year in which they were subject to the climate change governance requirements. Regulation 6(2) provides for limited exceptions to this requirement.

15. Where a scheme’s relevant assets fall below £500m on any subsequent scheme year end date, the trustees will cease to be subject to the climate change governance requirements with immediate effect (unless the scheme is an authorised scheme). The trustees must still publish their TCFD report for the scheme year which has just ended within 7 months of the scheme year end date, unless one of the exceptions in regulation 6(2) applies.

16. The circumstances in and timing by which trustees fall in and out of scope of the requirements are further detailed in the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations. The purpose of this Guidance is not to restate those legal requirements, but instead to help trustees understand how to meet them when they apply.

17. Trustees of other schemes may also find this Guidance helpful when implementing climate change risk governance and reporting on a voluntary basis.

PCRIG guidance on TCFD Recommendations

18. The Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group (PCRIG) has produced non-statutory guidance[footnote 6] for trustees on ways to approach improving their scheme’s climate governance and TCFD disclosures. Whilst it is not mandatory for trustees to consider or follow the PCRIG’s guidance, trustees may find its practical nature very helpful. For example, it sets out the types of action trustees may wish to consider following an assessment of climate risks and opportunities (which is beyond the scope of this Guidance). It also suggests wider resources that trustees may find helpful for scenario analysis amongst other topics. Trustees may therefore find it helpful to consider the PCRIG’s guidance in addition to this Statutory Guidance.

When this Guidance should be followed

19. The Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations require the trustees of schemes in scope to:

- implement climate change governance measures and produce a TCFD report containing associated disclosures; and

- publish their TCFD report on a publicly available website, accessible free of charge

20. The amendments made to the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 by the Miscellaneous Provisions Regulations require trustees who must produce a TCFD report to, among other things:

- include the website address of the TCFD report in the Annual Report

- tell members that the TCFD report has been published and where they can locate it by including this information in the Annual Benefit Statement and, for defined benefit (DB) schemes, the Annual Funding Statement

21. Trustees of occupational pension schemes must have regard to this Guidance when complying with the requirements under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations and with the requirements in the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013 listed above.

‘Must’ vs ‘Should’ vs ‘May’

In this Guidance, activities will be described as things trustees either ‘should’ do, ‘may’ choose to do or ‘must’ do. What this means for the purposes of the Guidance is set out below.

Should

It is expected that trustees will follow the approach set out in the Guidance and if they choose to deviate from that approach they should describe concisely the reasons for doing so in the relevant section of their TCFD Report.

May

Trustees can choose to follow the approach set out in the Guidance, and are encouraged to do so where possible, but if they choose not to they are not expected to explain their reasons in their TCFD Report.

Must

This is a requirement imposed by legislation. Failure to meet the requirement may lead to enforcement action by The Pensions Regulator.

Compliance with this Guidance

22. For occupational pension schemes, The Pensions Regulator (TPR) monitors compliance with legislation and provides guidance about what trustees need to do. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) is responsible for answering questions about the policy intentions behind the legislation. Neither DWP nor TPR can provide a definitive interpretation of the legislation, which is a matter for the courts.

23. Trustees and service providers should consider the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations to determine whether the new requirements apply to them, taking further advice where necessary.

24. Where the trustees do not comply with a requirement under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations – including where this is as the result of a failure to have regard, or to have proper regard, to this Guidance – TPR may take enforcement action which includes the possibility of a financial penalty. A mandatory penalty applies where there is complete failure to publish any TCFD report on a publicly available website, accessible free of charge.

25. Enforcement of requirements under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations is provided for in Part 3 of those Regulations. Regulation 5 of the Disclosure Regulations[footnote 7] sets out the penalties for failure to comply with the requirements of those Regulations, as referred to in this Guidance.

Part 2: Climate Change Governance Requirements – Overview

“As far as they are able”

1. Trustees are required to carry out the following activities “as far as they are able”[footnote 8]:

- undertake scenario analysis, taking into account the potential impact of climate change on the scheme’s assets and liabilities, the resilience of the scheme’s investment strategy and the resilience of any funding strategy[footnote 9]

- obtain the Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions and other data relevant to their chosen metrics. (Trustees are not required to obtain Scope 3 emissions data in the first scheme year that they are subject to the requirements)[footnote 10]

- use the data obtained to calculate their selected metrics[footnote 11] use the metrics they have calculated to identify and assess the climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to the scheme[footnote 12]

- measure the performance of the scheme against the target they have set in relation to one of their selected metrics[footnote 13]

2. Requirements to undertake the relevant activities “as far as they are able” recognise that there may be gaps in the data trustees are able to obtain about their scheme assets for the purposes of carrying out scenario analysis or calculating metrics. In addition, it recognises that particular challenges may arise in relation to the quantification of climate risks including some sovereign bonds, relevant contracts of insurance, asset backed contribution structures and derivatives. Additionally, in the case of DB schemes, there may be limitations in the scenario analysis they can carry out in relation to their liabilities, funding strategy or the sponsoring employer’s covenant.

3. Certain data may be expensive to collect or associated analysis complex to carry out. Trustees or those acting on their behalf are not expected to spend disproportionate amounts of time attempting to fill data gaps in relation to firms which are unlikely – due to their business activities or size – to contribute to climate-related risks posed to the scheme.

4. If trustees are able to obtain data or analysis in a format which is usable but only at a cost – whether directly or indirectly via liaison with advisers – which they believe to be disproportionate, they may make the decision to treat this data or analysis as unobtainable. A robust justification for doing so should be set out in their TCFD report.

5. Trustees should prioritise engagement on persistent data gaps which are likely to make the most material difference to accurately assessing the level of climate-related risk (or opportunity), to ensure that data quality continues to improve. Additional information requests to fill data gaps should be made with due regard to the size of the investee company in question and the likely materiality of their contribution to climate-related risks faced by the scheme.

6. The requirement to undertake scenario analysis “as far as they are able” will require trustees, or those acting on their behalf, to seek comprehensive data across their portfolio. For trustees of DB schemes, considering the resilience of the funding strategy as part of their scenario analysis would include considering the sponsoring employer’s covenant “as far as they are able”. However, if they cannot obtain a complete picture, they should still undertake scenario analysis.

7. In cases of incomplete data, trustees may need to:

- where they have a majority of data for particular asset classes - use modelling or estimation to fill the missing data gaps

- where there are certain asset classes or aspects of liabilities for which impacts, data or modelling tools are very limited or uncertain - take a qualitative instead of quantitative approach (see Part 3, paragraphs 64 to 67) for those aspects of their analysis, or proceed with scenario analysis for part of their portfolio or for those liabilities only

8. For any data trustees were unable to obtain, trustees must describe in their TCFD report the reasons for this.

9. For metrics, trustees must obtain data required to calculate their chosen metrics “as far as they are able”. They must then use this obtained data to calculate their chosen metrics as far as they are able. Similarly, trustees must measure, as far as they are able, performance against the target they have set in relation to one of their chosen metrics.

Limitations in data should not deter trustees from taking steps towards quantifying and assessing their scheme’s exposure to climate-related risks and opportunities more effectively through the use of metrics, and managing that exposure through the use of targets. Even estimated or proxy data can help identify carbon-intensive hotspots in portfolios, which can help to inform their investment and funding strategies.

Trustees should, as far as they are able, seek to populate gaps in data. For example, they may request that service providers apply sectoral averages based on companies that do publish data to fill in gaps in relation to companies who do not, or use other assumption-based modelling.

10. We note also that methodologies for calculating metrics in relation to certain asset classes, particularly derivatives, are not yet established. We do not expect trustees to be able to readily calculate emissions associated with derivatives at the current time.

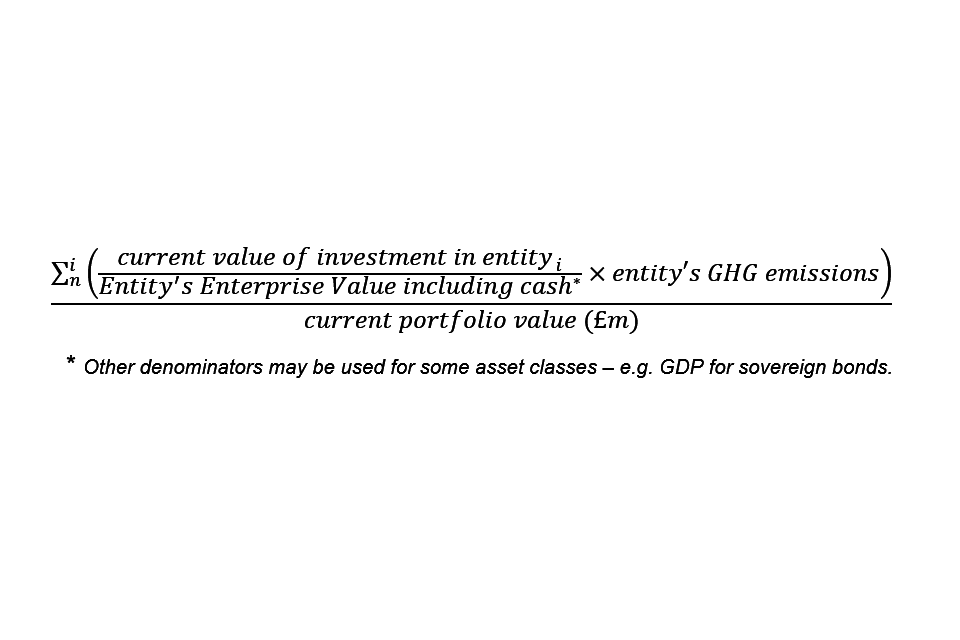

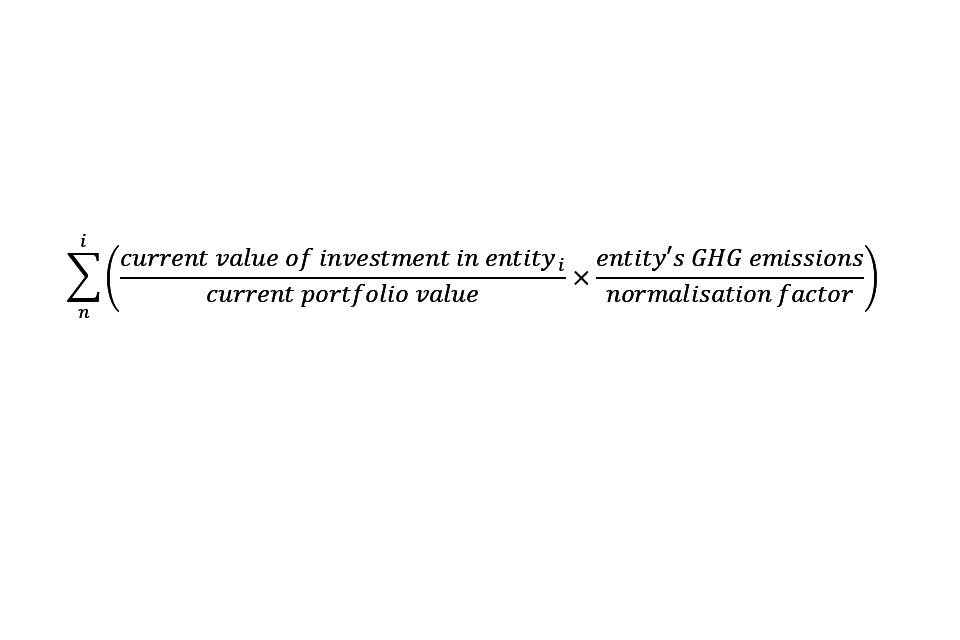

11. For metrics and targets, the Scope 3 emissions[footnote 14] of a scheme’s investments are likely to be challenging. Trustees are therefore not required to obtain Scope 3 emissions in the first scheme year that the regulations apply to them, although they may wish to do so. Trustees should seek to ensure the emissions of scheme assets are calculated in line with the GHG Protocol Methodology[footnote 15].The emissions should then be apportioned using a consistent approach[footnote 16] to allow, so far as possible, for aggregation and comparability across asset classes and funds and between schemes.

12. For metrics trustees must explain in their TCFD report why, if relevant, the data does not fully cover the portfolio or extend to all required scopes of emissions.

13. This explanation should be concise but it should set out clearly what data is missing and the impact this has in terms of the scope of the analysis or calculations the trustees have been able to do. It should also make clear where estimations or models have been used to fill gaps, any assumptions that could impact significantly on the results, whether any data gaps still remain and what steps the trustees are taking to address these gaps.

14. If trustees are using third party providers for scenario analysis, calculation of metrics, or measuring the scheme’s performance against targets, they should make sure that they are provided with sufficient information to be able to report on this.

Ongoing and Discrete Requirements

15. Some of the requirements imposed on trustees under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations are ongoing. This means that the activities trustees undertake to meet them should be maintained and where necessary, updated throughout the scheme year. This applies to the activities associated with governance, strategy (excluding scenario analysis) and risk management.

16. Some of the requirements are discrete. This means that the duty is to do something at a particular frequency. This applies to the activities associated with scenario analysis, metrics and targets.

Frequency of discrete activities

17. Scenario analysis must be carried out in the first scheme year during which the requirements in Part 1 of the Schedule apply to the trustees– even if the first year of application is a part year – and then at least every three scheme years thereafter. In the intervening scheme years when trustees are not required to carry out scenario analysis, they must still consider whether it is nevertheless appropriate to do so. Further information is set out in the section on scenario analysis below.

18. The data for metrics should be obtained, and the metrics calculated, in each scheme year. Performance against the target which trustees have set should also be measured and the target reviewed in each scheme year. Further information is set out in the section on metrics and targets below.

Level of the assessment

19. Governance and Risk Management activities should be carried out for the whole scheme.

20. Trustees should undertake the Strategy activities, including scenario analysis, at the following levels – and report accordingly:

- For a single section DB scheme, or for a DC scheme with no member choices (just one arrangement, and no self-select funds): at the level of the whole scheme

- For a scheme with more than one DB “section”[footnote 17]: at the level of each section. However, sections with similar characteristics in relation to assets, liabilities and funding may be grouped

- For DC schemes: for each popular arrangement offered by the scheme. A popular arrangement is considered to be one in which £100m or more of the scheme’s assets are invested, or which accounts for 10% or more of the assets used to provide money purchase benefits (excluding assets which are solely attributable to Additional Voluntary Contributions)

21. For schemes providing both DB and DC benefits, the two benefits should be considered separately for the purposes of the above – so for a scheme with two DB sections with dissimilar characteristics and one popular DC arrangement, the activities under Strategy should be carried out three times.

22. Where popular arrangements use life-styling or a number of target date funds for different age profiles, trustees may carry out the assessment in the round, but should identify risks and opportunities which affect particular cohorts more strongly.

23. Where appropriate, the approach set out above for Strategy activities should also be followed by trustees for calculating and reporting Metrics. However, if, in calculating absolute emissions metrics and emissions intensity metrics, trustees believe it is not meaningful to aggregate data across certain asset classes within a given section or arrangement of the scheme, they should not do so.

24. Trustees are free to measure performance against Targets and report on this in whatever way they see fit.

25. For self-select funds and default arrangements which do not meet the definition of a popular arrangement, trustees may also choose to undertake and report on the Strategy activities, including scenario analysis, calculate and report on Metrics, and set, measure performance against and report on Targets.

Risks and opportunities

26. To meet the requirements imposed by the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations 2021, trustees should have a good understanding of the climate-related risks and opportunities that are relevant to their scheme. Trustees should understand that as a systemic risk, climate change risk could include risks outside of the obvious sectors, including those which are both directly and indirectly affected.

27. Trustees may find it helpful to split their analysis of risks into ‘physical risks’ and ‘transition risks’ as a way to understand the potential impact on the scheme’s investments:

- Physical risks are those that pertain to the physical impacts that occur as the global average temperature rises. For example, the rise in sea levels could have impacts such as flooding and mass migration. Extreme weather events, such as flooding and fires, could become more frequent and severe, and these incidents could threaten physical assets and disrupt supply chains

- Transition risks arise as we seek to realign our economic system towards low-carbon, climate-resilient solutions. Changes in industry regulation, consumer preferences and technology will take place and impact on current and future investments

28. Litigation risks may also result where businesses and investors fail to account for the physical or transition risks of climate change.

29. Climate change risks are financial risks. The financial risks resulting from the effects of climate change have a number of distinctive elements:

- far-reaching in breadth and magnitude: The financial risks from physical and transition risk factors are relevant to multiple lines of business, sectors and geographies. Their full impact may therefore be larger than for other types of risks, and the risks are potentially non-linear, correlated and irreversible

- the time horizons over which financial risks may be realised are uncertain. Past data is unlikely to be a good predictor of future risks

- there is a high degree of certainty that financial risks from some combination of physical and transition risk factors will occur

- the magnitude of future impact will, at least in part, be determined by the actions taken today. This includes actions by governments, firms, pension schemes and a range of other actors

30. Trustees have a legal duty to consider matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making. Trustees must not only consider the kinds of financial risks which might affect investments (and in the case of DB schemes, their liabilities and sponsoring employers’ covenant), they should consider where climate change, and action to address climate change, might contribute positively to anticipated returns or to reduced risk.

31. Climate change related opportunities may include access to new markets and new technologies related to the transition to a low-carbon economy. Examples of climate-related risks and opportunities and their potential financial impacts are comprehensively set out in the TCFD’s Final Recommendations[footnote 18].

32. Climate-related risk and opportunity is one of the major categories of financial factors of which trustees need to take account. Trustees also need to take account of other risks affecting the pension scheme, in line with their fiduciary duty. As such, trustees are expected to take a proportionate approach to managing climate-related risks and opportunities. The time spent by trustees on considering climate-related risks and opportunities, should not come at the expense of considering other major risks, including financially material social and governance factors.

Trustee knowledge and understanding of climate-related risks and opportunities

Important – this section is not Statutory Guidance, but is intended as best practice.

Trustees are not required to have regard to this section of the Guidance but are encouraged to do so. Trustees are not expected to provide an explanation in their TCFD Report if they choose not to follow this Guidance.

33. Beyond existing duties to have knowledge and understanding of pensions law and trusts law and the principles relating to investments[footnote 19], new requirements for knowledge and understanding in relation to climate change apply to individual and corporate trustees who are subject to requirements in the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations. The new requirements are prescribed by regulation 2 of the Miscellaneous Provisions Regulations.

34. Individual trustees must have sufficient knowledge and understanding of the identification, assessment and management of risks arising to occupational pension schemes from the effects of climate change and of opportunities relating to climate change to enable them to meet the requirements in Part 1 of the Schedule to the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations.

35. Individual trustees must have the appropriate degree of knowledge and understanding of these matters to enable them to properly exercise their functions. In the case of corporate trustees, the company is required to secure that any person exercising its functions as trustee has the appropriate degree of knowledge and understanding of these matters.

36. This means, for example, understanding how scenario analysis works, why climate change poses a material financial risk and its relevance to overall risk management.

37. This understanding need not require a mastery of technical detail, however. It is anticipated that in most cases, trustees – or those exercising trustee functions in the case of corporate trustees – will not be carrying out the underlying activities to identify or assess climate-related risks and opportunities themselves. Nor will they be implementing investment strategies which take account of climate change in a hands-on way. Rather, they will identify experts to do this. Yet, as trustees are ultimately responsible for identifying, assessing and managing climate-related risks the scheme is exposed to, they should have sufficient knowledge and understanding to understand the results of any analysis and know how to take action in light of these results, or indeed to challenge assumptions, external advice and information. In the case of corporate trustees, they should ensure that those exercising their functions have this knowledge and understanding.

38. Trustees are encouraged to ensure that they – or those exercising their functions, in the case of corporate trustees – are keeping their knowledge and understanding of how to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks and opportunities up-to-date, so that they can meet the knowledge and understanding requirements.

39. Stewardship activities, including engagement and voting activities, can promote the long term success of pension schemes by encouraging investee companies to take a long-term, responsible approach to their business strategy. Through engagement with intermediaries including consultants and asset managers, as well as investee companies, trustees will also be in a good position to keep their knowledge of climate change risk and opportunities up-to-date and learn about governance approaches, strategies, risk management tools, metrics and targets.

40. Industry collaboration, not only on stewardship but also on trustee knowledge and understanding more broadly, is encouraged, particularly as resources, including climate data, analytical tools and associated guidance improve.

41. The disclosures made in the TCFD report will help demonstrate to those reading that report whether the trustees have an appropriate degree of knowledge and understanding in respect of the climate-related risks and opportunities they manage[footnote 20]. Where the content of the disclosures is poor, this could raise concerns to The Pensions Regulator about the trustees’ level of knowledge and understanding.

Part 3: Climate change governance and production of a TCFD Report

1. This section of the Guidance sets out the matters to which trustees of the schemes in scope must have regard when producing a TCFD report in accordance with the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations.

2. To do this effectively, trustees need to meet the requirements specified in the Regulations in relation to Governance, Strategy and Risk Management, carry out scenario analysis, select and calculate appropriate Metrics and set Targets and measure the scheme’s performance against them.

Purpose of disclosures

3. The Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations require trustees to disclose a range of information about their scheme. The specifics of these disclosures are set out in Part 2 of the Schedule to the Regulations, with more information in this Guidance.

4. In general, trustees should regard disclosure as the output of the processes they have put in place and actions they have taken to understand and address the risks and opportunities that climate change poses to the scheme.

5. Disclosing the information is an important way to help achieve transparency toward members, TPR and the pension sector generally. This should improve accountability, and the development of future regulation and best practice. However, the principal purpose of disclosure is to ensure that trustees are thorough and rigorous in taking the actions required by the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations. This is aligned with the Government’s intention to make TCFD-aligned disclosures mandatory across the economy by 2025[footnote 21].

Content of a TCFD Report

6. A significant benefit of making TCFD reports publicly available is that it will provide members with the opportunity to engage with their scheme’s climate-related risks and opportunities, and the potential impacts on their pension savings.

7. Whilst we acknowledge the challenges of producing a TCFD report which is digestible by all beneficiaries, trustees should present their TCFD reports in a way that would allow a reasonably engaged and informed member to be able to interpret and understand trustees’ disclosures, and raise concerns or queries where appropriate.

8. As a minimum, the TCFD report should include a plain English summary which is for members to read and allows them to become easily acquainted with the key findings from the report. This will allow trustees to retain the necessary more in-depth analysis in the main body of the report, which more engaged members may still wish to read in full.

9. Trustees should also consider the TCFD’s own Principles of Effective Disclosure, as set out in the Annex, when producing their TCFD Reports.

10. In summary, the core elements that should be included in the TCFD report are:

Governance

The organisation’s governance around climate-related risks and opportunities.

Strategy

The actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy and financial planning.

Risk Management

The processes used by the organisation to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks.

Metrics and Targets

The metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities.

Governance

11. ‘Governance’ refers to the way a scheme operates and the internal processes and controls in place to ensure appropriate oversight of the scheme. Those undertaking governance activities are responsible for managing climate-related risks and opportunities. This includes trustees and others making scheme-wide decisions. This includes – but is not limited to – decisions relating to investment strategy or how it should be implemented, funding, the ability of the sponsoring employer to support the scheme and liabilities.

12. Under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations trustees must establish processes to satisfy themselves that any person undertaking scheme governance activities takes adequate steps to identify, assess and manage any climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to those activities. Trustees must also establish processes to satisfy themselves that others advising or assisting the trustees with respect to governance activities take adequate steps to identify and assess any relevant climate-related risks and opportunities.

13. Firms carrying out asset management alone would not typically be considered to be undertaking governance activities. Administrators are unlikely to be in scope unless they are undertaking activities related to the scheme to which climate-related risks and opportunities are relevant. With regard to those advising or assisting the trustees – legal advisers are specifically excluded from the requirement.

14. The PCRIG Guidance[footnote 22] provides some information on how trustees can factor climate-related risk management capabilities into the selection, review and monitoring of asset managers.

Trustees’ and others’ oversight of climate-related risk

15. Trustees have ultimate responsibility for ensuring effective governance of climate-related risks and opportunities. The roles and responsibilities of the trustees and others making scheme-wide decisions pertaining to climate-related risk should be addressed at board, sub-committee and individual trustee levels. The Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations require trustees to put in place and report on the governance processes that ensure they have oversight of the climate-related risks and opportunities relevant to the scheme. These governance processes should enable trustees to be confident that their statutory obligations and fiduciary duties are being met.

16. Trustees should decide the appropriate governance structure and processes for their scheme. Trustees may choose to take an approach to the oversight and management of climate-related risks and opportunities that replicates the process for how they consider other risks and opportunities. Alternatively, trustees may decide that the governance process around climate-related risk and opportunities should be separate, reflecting the unique challenge these risks pose and the severity of the impact they could have on their scheme. Either approach is acceptable – trustees may base the decision on their assessment of the magnitude, nature, unpredictability and duration of climate-related risks to the scheme, and may take account of cost and complexity.

17. Trustees should allocate time and resources for meeting their obligations on climate change governance and reporting. It is expected that for most schemes, trustees will require regular discussion of climate-related risk and opportunities at board level, as a substantive agenda item.

18. All schemes are exposed to some degree of climate-related risks and opportunities. The appropriate amount of time and resource the trustee allocates to governing these risks will depend on factors such as the size, type and maturity of the scheme, and the degree to which the scheme is exposed to climate-related risk. Trustees should use outputs from other TCFD-related activities, including Risk Management, Strategy (including scenario analysis) and Metrics and Targets to help determine how much time and resource is allocated to overseeing climate-related risk.

19. Trustees may need to revise their governance structure and processes in light of these outputs. For example, if trustees discover, through scenario analysis, that some of the scheme’s assets are particularly vulnerable to a type of climate-related risk, they should reconsider whether they are dedicating sufficient resource to processes for assessing and mitigating risk.

Oversight of climate-related risk by those who undertake governance activities and advise or assist with those activities

20. Most occupational pension schemes operate a governance structure that is at least partly reliant on persons other than the trustees or trustee board. The Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations apply in respect of those undertaking governance activities in relation to the scheme and those who advise or assist the trustees with respect to governance activities. By undertaking governance activities, we mean making scheme-wide decisions. By advising or assisting with respect to governance activities, we mean advising or assisting the trustee with scheme-wide decisions. Those undertaking governance activities or advising or assisting with respect to these activities include:

- employees of the scheme

- employees of the principal or controlling employer[footnote 23]

- employees of the scheme funder or strategist[footnote 24] (in the case of a master trust); and

- external advisers who provide services to the trustee

21. External advisers include those who influence significant climate-related decisions, including investment consultants, scheme actuaries, voting advisers, covenant advisers and fiduciary managers. The common characteristic of these persons is that they are engaged by the trustees or the sponsoring employer, to advise or assist the trustees with scheme-wide decisions or to occasionally make scheme-wide decisions.

22. Trustees must establish and maintain processes to satisfy themselves that those assisting with or advising on scheme governance activities take adequate steps to identify and assess any climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to the matters on which they are advising or assisting. However, this need not be a separate process for each type of advice or assistance, and an approach proportionate to the materiality of the climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to the matters being assisted with, or advised on, is expected.

23. Trustees should clearly define the roles and responsibilities, in relation to climate-related risk, of the groups of people they consider to be involved in governing the scheme. This should not extend beyond the role these persons hold in relation to the specific scheme.

24. Trustees should satisfy themselves that those undertaking governance activities, other than the trustee, and those advising or assisting in relation to those activities each have adequate climate-related risk expertise and resources, to the extent necessary for that person’s role. The governance processes put in place should enable trustees to engage with those governing the scheme or advising or assisting with governance, and check that they have adequately prioritised climate-related risk.

25. When using external advisers to identify and/or assess climate-related risks and opportunities, trustees should consider and document the extent to which these responsibilities are included in any agreements, such as investment consultants’ strategic objectives and service agreements.

26. Trustees must also ensure that the scheme’s governance process and structure provides them with adequate oversight of how those governing the scheme, on their behalf, are managing the scheme and adequately assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities.

27. Trustees should ensure that persons to whom they have assigned climate-related responsibilities have clear directions in terms of how and when they inform trustees of their work. It is expected that trustees would need regular updates, the frequency of which will depend on the particular risks the scheme is exposed to and the results of other TCFD-related outputs, like scenario analysis. It is important that trustees understand the information provided to them and can critically challenge this information, where appropriate.

28. Trustees cannot delegate responsibility for their obligations under the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations Trustees have ultimate responsibility for how the scheme manages climate-related risks and opportunities. The requirements do not impose new legal duties on persons other than trustees.

29. Trustees should ensure that information about the scheme that is relevant to the identification, assessment and management of risks and opportunities relating to climate change is shared between persons tasked with these responsibilities. There should be clear lines of communication between those working on climate-related risk and others within the scheme.

30. Trustees should provide opportunities for their employees carrying out governance activities to undertake training on climate risks and opportunities. Where skills gaps are identified by the trustees, they may find it useful to encourage external advisers to do the same for their own employees.

31. Trustees may find it helpful to do a skills audit in relation to:

- The trustees’ expertise on climate change

- The expertise of others undertaking governance activities; and

- The expertise of those advising or assisting in respect of governance activities

32. Having a clearer picture of the skills and gaps that exist across these three groups will help the trustees develop processes to keep their knowledge and understanding in relation to Governance, Strategy, Risk Management and Metrics and Targets up-to-date.

Disclosure of governance information

In relation to the governance disclosure requirements, trustees must describe in their TCFD report:

- how they maintain oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to the scheme

- the roles of those undertaking scheme governance activities, in identifying, assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities relevant to those activities

- the processes the trustees have established to satisfy themselves that those undertaking scheme governance activities take adequate steps to identify, assess and manage those risks and opportunities

- the role of those advising or assisting the trustees with scheme governance activities; and

- the processes the trustees have established to satisfy themselves that the person advising or assisting takes adequate steps to identify and assess any climate-related risks and opportunities which are relevant to the matters on which they are advising or assisting

34. To help contextualise these disclosures, trustees should concisely describe:

- how the board and any relevant sub-committees are informed about, assess and manage climate-related risks and opportunities and the frequency at which these discussions take place

- whether they questioned and, where appropriate, challenged the information provided to them by others undertaking governance activities – or advising and assisting with governance; and

- the rationale for the time and resources they spent on the governance of climate- related risks and opportunities

35. Trustees should also concisely describe, in relation to those who undertake governance activities, or advise or assist with governance of the scheme:

- the kind of information provided to them by those persons about their consideration of climate-related risks and opportunities faced by the scheme; and

- the frequency with which this information is provided

36. Trustees should describe the training opportunities they provided for their employees in relation to climate change risks and opportunities. Where trustees identified skills gaps, they may also describe whether they encouraged external advisers to provide training opportunities.

37. Trustees may wish to provide an organogram or structural diagram in their TCFD report, showing which groups / individual roles have responsibilities for governance of climate-related risks and opportunities. This may include executive officers, in-house teams and / or third parties engaged by the trustees. For the avoidance of doubt, there is no expectation that this would involve disclosing personal data of individuals.

Strategy

38. Trustees should think strategically about the climate-related risks and opportunities that will have an effect on the scheme. In doing so they must consider climate-related risks and opportunities in relation to their investment strategy and their funding strategy, where they have one. Part of this assessment will include scenario analysis. More detail about this is set out from paragraph 62 onward.

Investment strategy and funding strategy

39. ‘Investment strategy’ refers to factors such as the scheme’s strategic asset allocation, the selection of investment mandates and portfolio construction. It includes whether the scheme’s investments and mandates are active or passive, pooled or segregated, growth or matching, have long or short time horizons and are liquid or illiquid in nature.

40. ‘Funding strategy’ refers to the strategy by which the trustees expect to have sufficient assets to meet the expected future payments due from the scheme. It includes consideration of:

- the scheme’s assets and how the value(s) of the assets held are expected to develop in the future

- the scheme’s liabilities and the assumptions used to determine them

- the contributions that will be paid by the sponsoring employer to meet the scheme funding requirements of Part 3 of the Pensions Act 2004 (and the likelihood of those contributions being paid)

- the strength of the covenant offered by the sponsoring employer and how the strength of the covenant is expected to develop over the expected lifetime of the scheme

41. Consideration of the resilience of the funding strategy to the effects of climate change includes consideration of the sponsoring employer’s covenant as well as covering tolerance to changes in assumptions. This includes undertaking scenario analysis.

Scope of assessment

42. All asset types are within scope for the assessment of a scheme’s investment strategy, funding strategy (where it has one) and for scenario analysis. Trustees should not start from the assumption that climate change is irrelevant for some assets or sectors. For example, climate-related risks could affect the value of assets such as corporate and sovereign debt. Climate change may also affect the strength of the sponsoring employer’s covenant.

Time horizons

43. Trustees must decide the short, medium and long-term time horizons that are relevant to their scheme. Trustees must state in their TCFD report the time horizons they have chosen.

44. It is up to trustees how they determine their time horizons. However, in deciding what the relevant time horizons are, trustees must take into account the liabilities of the scheme and its obligations to pay benefits. Trustees should also take account of the following:

- In a DB scheme or a DB section[footnote 25] of a scheme: the likely time horizon over which current members’ benefits will be paid. This may be the longest time horizon they will need to consider

- In a DC scheme or a DC section of a scheme: the likely time horizon over which current members’ monies will be invested to and through retirement. This may be the longest time horizon they will need to consider

45. Trustees may also consider other factors such as the scheme’s cash flow, investment strategy and, where they have one, funding strategy.

46. Trustees are not required to disclose in their TCFD report why they have chosen certain time horizons. However, they may decide to do so.

Types of risks and opportunities

47. Trustees must identify, and assess the impact of, what they consider to be the relevant climate-related risks and opportunities for each time horizon (short, medium and long term). See Part 2, paragraphs 26 to 32 above for guidance on types of climate-related risks and opportunities that may be relevant to the scheme. Examples of climate-related risks and opportunities and their potential financial impacts are also comprehensively set out in the TCFD’s Final Recommendations[footnote 26].

Considerations relating to the employer covenant

48. The covenant is a significant source of support for most DB schemes. Sponsoring employers’ businesses may be affected by climate change including (but not limited to) physical risks (e.g. to their supply chains) and/or transition risks, which may be particularly impactful for sponsoring employers in, or dependent upon, high carbon sectors.

49. As part of their assessment of the resilience of the funding strategy, trustees of DB schemes must consider the impact of climate-related risks and opportunities on the sponsoring employer’s covenant over the relevant short, medium and long-term time horizons. Trustees’ scenario analysis must also, as far as they are able, consider the resilience of the covenant in the relevant chosen scenarios.

50. Trustees seeking information about the impact of climate change on their sponsoring employer may wish to consider:

- Engaging with the sponsoring employer to discuss its assessment of the climate-related risks, and opportunities, to which it is exposed. The information above on “Risks and Opportunities” (see Part 2, paragraphs 26 to 32) may help frame this discussion

- Any climate-related disclosures, such as those made in line with the TCFD’s recommendations, by the sponsoring employer

51. Where trustees of a DB scheme have identified climate-related concerns with the sponsoring employer and the potential strength of the covenant, we would encourage them to consult with, and where necessary challenge, the sponsor, where they deem this appropriate. Trustees may wish to take action such as:

- considering whether their investment strategy and funding strategy are sufficiently prudent, in light of non-mitigated climate risks

- considering whether their long-term funding objective is appropriate or needs to change

- incorporating climate-related triggers into the scheme’s contingency planning framework

52. However, trustees are not compelled to take action. Where they cannot form a robust assessment of the impact of climate change on the covenant, for example because of a lack of information or uncertainty about the impact of climate change on the sponsoring employer’s business model, they should keep the assessment under review and consider elevating covenant risks within their risk management priorities.

53. Discussions about the impact of climate change on the covenant will often involve confidential information about the sponsoring employer. This is equally true for other information shared as part of the covenant review process and wider discussions. Its confidential nature should not therefore prevent it from being shared with trustees and their advisers.

54. When making their own TCFD disclosures, trustees should take account of the confidential nature of information shared about the covenant. However, trustees and sponsoring employers should not assume that this information is always confidential business information that would harm the sponsoring employer if disclosed. For example, trustees may be able to disclose higher level information and/or information about the process they have followed. Trustees may wish to take legal advice regarding confidentiality.

Assessing the impact on the investment strategy and funding strategy

55. Trustees must, on an ongoing basis, assess the impact of the climate-related risks and opportunities they have identified on the scheme’s investment strategy, and the funding strategy, where the scheme has one.

56. Climate change may affect a scheme’s assets, including by impairment or enhancement of the income or capital growth expected to be generated by the individual investments held. DB schemes’ liabilities may also be affected by impacts on inflation, interest rates and demographic factors, particularly longevity. Climate change may also impact the sponsoring employer’s covenant.

57. Trustees should consider climate-related risks and opportunities in the context of their strategic asset allocation, and how climate change may affect the different asset classes the pension scheme is invested in over time. They should also take account of the anticipated changes in asset allocation over time when assessing the impact on their investment and funding strategy.

58. Trustees should consider the asset manager mandates they have set or intend to set for each asset class. Trustees may wish to align the investment mandates they implement with the climate-related risks and opportunities they have identified as relevant to their scheme.

59. Trustees investing in pooled funds should consider how the managers take climate change into account in those funds, including in relation to stewardship and engagement.

60. It is up to trustees how they undertake the assessment of the impact on the investment and funding strategies. However, trustees may find it helpful to “grade” or organise the identified risks and opportunities across the short, medium and long-term time horizons they set. Factors that could be considered include likelihood, timeline, severity of impact etc.

61. In line with the TCFD’s Supplemental Guidance for Asset Owners, trustees may wish to undertake, either directly or through their agents, engagement activity with investee companies to encourage better disclosure and practices related to climate-related risks. This may help improve data availability and trustees’ ability to assess such risks[footnote 27].

Scenario Analysis

62. Scenario analysis requirements must be met by trustees “as far as they are able”. More information about this is set out at Part 2, paragraphs 1 to 14.

63. This may mean that initially, for some schemes, not all asset classes can be included in the scenario analysis or that some assets will be assessed by a broader qualitative approach. Particular challenges relate to those asset classes mentioned in paragraph 2 of Part 2 above. It may be that in the case of relevant contracts of insurance, especially those which are not “collateralised”, reference to the appropriate insurer’s TCFD disclosures can be made.

Considerations for approaching scenario analysis

Quantitative or qualitative scenario analysis

64. The purpose of scenario analysis is to better understand the risks and opportunities posed by climate change to the scheme and to inform trustees’ strategy and investment decisions accordingly. A scenario describes a path of development leading to a particular outcome. Scenarios are not intended to represent a full description of the future but rather to highlight central elements of a possible future and to draw attention to the key factors that will drive future developments. They are hypothetical constructs, not forecasts, predictions or sensitivity analyses.

65. Scenario analysis may be qualitative and/or quantitative. Trustees with no or limited experience of scenario analysis may find it easiest to start with qualitative analysis. Qualitative scenario analysis uses narratives to explore the implication of different possible climate impacts. At its most basic, trustees could start from the question “what if…?” and introduce potential climate-related risks, for example “what if policymakers introduced a high carbon price?”.

66. Quantitative scenario analysis can produce more developed and rigorous outputs. Trustees of all schemes in scope should progress towards developing the sophistication of their scenario analysis and to using quantitative analysis, especially where they believe that climate change could pose significant risks to their scheme.

67. Trustees may wish to overlay their quantitative analysis with a qualitative narrative, for example by providing some wider context and explaining the impact of their findings. In line with the TCFD’s Supplemental Guidance for Asset Owners, trustees may wish to provide a discussion of how climate-related scenarios are used, such as to inform investments in specific assets[footnote 28]. This can help with their own, and others’, understanding.

Using third-party providers

68. Trustees may wish to use the services of a third-party provider to do scenario analysis. A third-party provider may be able to help trustees apply an “off the shelf” scenario or to develop a bespoke one.

69. However, whether or not they use a third-party provider, trustees should ensure that they have an understanding of the scenarios that are used. This includes the underlying assumptions which make up the scenarios (for example, scenarios will be based on assumptions about variables such as the use of carbon capture and storage technologies, the timing of emissions reduction and the scope of policy interventions). If trustees do not understand these, it will be difficult for them to interpret and act on the outputs of the scenario appropriately.

70. The TCFD Technical Supplement on the use of Scenario Analysis in disclosure of climate-related risks and opportunities[footnote 29] sets out more details on common assumptions in scenario analysis.

71. Trustees should also consider whether they could gain more insight from undertaking a simpler form of scenario analysis in-house than out-sourcing it to a third-party. Trustees should keep in mind the purpose of scenario analysis. (see para 64 above). They should not assume that this will be best achieved by using the most complex, sophisticated and/or expensive tools available.

Information from asset managers

72. Trustees may find it easiest to do a “top-down” analysis of the scheme-level risks to their scheme’s aggregated portfolio. This may be easier than starting from information from asset managers about individual asset classes. It is also likely to be difficult for trustees to aggregate scenario analysis that has been done on different asset classes or by different managers for reasons such as different underlying assumptions.

Chosen scenarios

73. Trustees must, as far as they are able, conduct scenario analysis in at least two scenarios where there is an increase in the global average temperature and in one of those scenarios the global average temperature increase selected by the trustees must be within the range of 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels, to and including 2oC above pre-industrial levels. The temperature used in the scenario should be the “eventual” temperature increase within the chosen timeframe, on the assumption that the temperature would stabilise at this level and not continue increasing.

74. In selecting the scenarios they will use, trustees should consider not only the projected potential global average temperature rise, but also the nature of the transition to that temperature rise. For example, it is possible to have many different scenarios representing an eventual global average temperature rise of 2°C above pre-industrial levels because of differences in the assumptions made about the type of transition. Trustees may therefore want to consider a range of scenarios like the following:

- a measured, orderly transition takes place with climate policies being introduced early and becoming gradually more stringent. Ambitions under the Paris Agreement and commitments such as the UK’s commitment to achieve net zero by 2050 are met in an orderly manner. This is likely to mean lower transition risks and less severe physical risks. (Such a scenario could be used for the required scenario of a temperature increase within the range of 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels, to and including 2oC above pre-industrial levels)

- a sudden, disorderly transition takes place with climate policies and wider action on climate change not happening until late (e.g. introduced around 2030). Although climate goals are met, transition risks are also more likely to materialise, given the need for sharper emissions reductions, alongside increased physical risks. (Such a scenario could be used for the required scenario of a temperature increase within the range of 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels, to and including 2oC above pre-industrial levels)

- a “hot house world” which assumes only currently implemented policies are preserved, current commitments are not met and emissions continue to rise. This would mean climate goals are missed and physical risks are high with accompanying severe social and economic disruption

75. The Network for Greening the Financial System sets out representative scenarios in the above ranges which trustees may wish to reflect in their own scenario analysis[footnote 30].

76. A list of reference scenarios can also be found at Annex 2 of the Climate Financial Risk Forum Guide to Scenario Analysis[footnote 31].

77. Trustees should choose scenarios that reflect their reasoned assessment of plausible pathways and should not focus on scenarios that rely on progress, or otherwise, that they consider unlikely to happen. Trustees may wish to assess the impact of each scenario over the short, medium and long term horizons identified under their Strategy activities.

78. As with the Strategy activities, trustees should take account of anticipated changes in asset allocation over time when carrying out scenario analysis. For example, in the case of a recently closed DB scheme, the trustees should not assume either that the asset allocation will be the same in 30 years as it is now, or the effect of a climate scenario on an assumed “snapshot” asset allocation at a distant point in the future. Rather, they should seek, where possible, to consider the impact of the temperature scenario on the assets as the allocation changes over time.

79. Physical risks are relevant in all scenarios that assume any global temperature increase. Trustees should therefore test the resilience of their investment strategy and, if they have one, their funding strategy against both transition and physical risks.

80. When selecting scenarios, trustees should seek to avoid selecting those which, although related to different eventual temperature increases, present similar trajectories over the relevant time horizons. For example, trustees of a scheme with a time horizon of 10 years should avoid using two scenarios that both assume ‘business as usual’ for the next decade before diverging.

Scenario analysis and the funding strategy

81. Assessing the resilience of the funding strategy includes consideration of the sponsoring employer’s covenant. The covenant is an important source of support for many DB schemes. Trustees should use scenario analysis to better understand the potential impact on the covenant of the effects of climate change. Trustees may initially find it easiest to start with qualitative scenario analysis for the covenant. Trustees may wish to address questions such as:

- what are the greatest risks posed to the sponsoring employer in our chosen scenarios / what if X happens?

- what could the sponsoring employer do to address such a risk? Is the sponsoring employer taking action to avoid and/or address such a risk?

Liabilities

82. Trustees must, as far as they are able, assess the potential impact on the scheme’s liabilities of the effects of the global average increase in temperature, and also of any steps which might be taken because of the temperature increase – by governments or otherwise – in their chosen scenarios. This may include considering the impact on:

- financial assumptions based on market yields / assumed market values that may be mispriced if they do not take account of climate change

- investment return assumptions based on models that extrapolate past trends and so implicitly ignore the possible future impact of climate change

- mortality rates, which may be impacted by environmental factors such as air pollution, changes in temperatures and extreme weather events and economic factors such as financial well-being and access to healthcare

83. This is a developing area of work and trustees and their advisers may not always be able to reach robust conclusions on which they are able to act. However, trustees should still seek to understand the potential impact of the effects of climate change on their liabilities.

Annual review

84. Scenario analysis must be undertaken in the first scheme year during which trustees are subject to the requirements in the Regulations– even if the first year of application is a part year – and in every third scheme year thereafter. However, this timescale is reset if trustees decide to undertake scenario analysis before that third scheme year.

85. If the first year in respect of which the requirements apply is a part scheme year, scenario analysis undertaken in that scheme year, but before the date from which the requirements apply to the trustees, may still be relied upon to meet the requirements.

86. Provided the TCFD report is produced and published in accordance with the Regulations within 7 months of the end of the scheme year, the drafting of the TCFD report can take place after the end of the scheme year.

87. Trustees must always describe their most recent scenario analysis in their TCFD report, but may also choose to describe previous scenario analysis where that scenario analysis remains relevant.

88. In the scheme years where trustees are not required to undertake scenario analysis, they must review their most recent scenario analysis and determine whether they should nevertheless undertake new scenario analysis in order to have an up-to-date understanding of the matters they are required by the Regulations to consider.

89. Circumstances which are likely to lead trustees to decide that new scenario analysis should be undertaken in a scheme year where it is not mandatory include, but are not limited to:

- a material increase in the availability of data. This is likely to happen as TCFD reporting increases across the investment chain, bringing with it more data for different asset classes and for sponsoring employers’ businesses. This is likely to happen rapidly in the first few years after the Climate Change Governance and Reporting Regulations are in force

- a significant/material change to the investment and/or funding strategy or some other material change in the scheme’s position

90. Trustees may wish to consider undertaking new scenario analysis in the following circumstances, if they think it is appropriate to do so:

- the availability of new or improved scenarios or modelling capabilities (for example 1.5oC scenarios) or events that might reasonably be thought to impact key assumptions underlying scenarios (for example, more countries making net zero commitments)

- a change in industry practice/trends on scenario analysis. This may include increased popularity of particular types of scenarios or widespread use of particular temperature outcomes to use for a “business as usual” scenario

91. If trustees decide not to undertake new scenario analysis, they must explain in their TCFD report the reasons for their decision. If they do not carry out new scenario analysis, they must also include the results of the most recent scenario analysis in their latest TCFD report, as set out below.

Disclosure of Strategy and scenario analysis information

92. Trustees must describe in their TCFD report:

- the time periods which the trustees have determined should comprise the short term, medium term and long term

- the climate-related risks and opportunities relevant to the scheme over the time periods that the trustees have identified and the impact of these on the scheme’s investment strategy and, where the scheme has a funding strategy, the funding strategy

- the most recent scenarios the trustees have used in their scenario analysis

- the potential impacts on the scheme’s assets and liabilities which the trustees have identified in those scenarios and, if the trustees have not been able to obtain data to identify the potential impacts for all of the assets of the scheme, why this is the case

- the resilience of the scheme’s investment strategy and, where the scheme has a funding strategy, the funding strategy, in the most recent scenarios * the trustees have analysed; and where trustees have concluded that it is not necessary to undertake new scenario analysis outside the mandatory cycle, the reasons for this determination

93. Trustees should also describe in their TCFD report:

- their reasons for choosing the scenarios they have used; and

- the key assumptions for the scenarios used and the key limitations of the modelling (for example, material simplifications or known under/over estimations); and

- any issues with the data or its analysis which have limited the comprehensiveness of their assessment (see section on “as far as they are able” at Part 2, paragraphs 1 to 11 above)

94. Trustees may include information in their TCFD report on any other aspects of the assessment of their investment strategy and, if they have one, funding strategy and scenario analysis that they consider would be helpful to disclose.

Risk Management

95. Risk management is of fundamental importance to effective governance around the potential implications of climate change and disclosure in line with the TCFD recommendations. Climate-related risk presents unique challenges and requires a strategic approach to risk management. Trustees must establish and maintain processes for the purpose of enabling them to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks which are relevant to the scheme, and must ensure that their overall risk management integrates these processes.

96. This means having adequate processes for the management of all risks to which the scheme is exposed, including climate-related risks. Trustees must identify, assess and manage the transitional risks to their investments that the pursuit of a lower carbon economy will bring, as well as the physical risks to their assets brought about by the changes in our climate which are already taking place. Risks to liabilities and employer covenants are further risks trustees must consider where these are relevant to the investment strategy or funding strategy.

97. Good risk management is a key characteristic of a well-run scheme and an important part of the trustee’s role in protecting members’ benefits. An adequate risk management system will help trustees to keep scheme assets safe and protect the scheme from risks, as far as that is appropriate. Trustees are best placed to decide what risk management process to use, but should be asking:

- “which climate change risks are most material to the scheme?”

- “how do we take account of transition and physical risks in our wider risk management?”

- “how does climate change affect our risk appetite?”

Processes for identifying and assessing climate-related risk

98. Trustees must establish and maintain processes for the purpose of enabling them to identify and assess climate-related risks which are relevant to the scheme. A scheme’s existing processes may warrant adjustment to ensure they sufficiently address the unique characteristics of climate-related risks.

99. Transitioning to a lower-carbon economy may entail extensive policy, legal, technology, and market changes to address mitigation and adaptation requirements related to climate change. Depending on the nature, speed, and focus of these changes, transition risks may pose varying levels of financial and reputational risk to schemes.

Climate-related risk types

The TCFD recommendations divide climate-related risks into two major categories:

Transition Risks

This category includes policy, legal, technology, market and reputation risk factors. Descriptions of these transition risks can be found in the TCFD’s guidance on Risk Management, alongside approaches for managing those risks and possible metrics for measuring risk[footnote 32].

Physical Risks

Physical risks from climate change can be event driven (acute) or longer-term shifts (chronic) in climate patterns, and include risks such as a rise in sea levels, with impacts including flooding, and the destruction of biodiversity.

These physical risks will have financial implications for schemes, such as direct damage to assets and indirect destabilising impacts from supply chain disruption. Other potential impacts of physical changes in the climate are wider economic and social disruption, including mass displacement, environmental-driven migration and social strife.

100. Trustees may rely on other persons, including advisers, asset managers and the sponsoring employer’s management teams, to help them identify and assess climate-related risks. However, trustees have overall responsibility for the management of these risks and also of the opportunities arising from climate change. Possible approaches to identifying and assessing transition risks and physical risks involve the trustees, or others acting on their behalf:

- identifying climate-related regulatory developments that may impact scheme investments

- assessing the potential for new and emerging technologies to offer opportunities and to supersede legacy technologies

- identifying relationships between news or events and business and financial impacts to manage reputational risks to the scheme or its investments

- engaging with service providers to compare the scheme’s position to peers or competitors

- considering the impact of physical risk factors such as physical damage – and disruption to outsourcing arrangements and supply chains – for key parts of the scheme’s portfolio

- given the long-term nature of climate risk – extending their consideration to longer time horizons

101. The trustees’ assessment of climate-related risks is fundamental to their prioritisation of those risks, and the management of those which pose the most significant potential for loss and that are most likely to occur.

102. Trustees may use a traditional “likelihood and impact” approach to gauge the severity or materiality of their risks. Given some of the unique characteristics of climate-related risks, trustees may expand their prioritisation criteria to include “vulnerability” and “speed of onset”.

- vulnerability refers to the susceptibility of a scheme to a risk event, in terms of its preparedness, agility, and adaptability

- speed of onset is the time that elapses between the occurrence of an event and the point at which the scheme feels its effect. Knowing the speed of onset can help trustees develop risk response plans

103. The processes for assessing risks to assets should be applied at the asset-class or key sector level as a minimum. Trustees may consider undertaking more granular risk appraisal to identify trends in risk. This may include, for example, consideration of the potential for a breakdown of longer-term average correlations between asset classes, particularly where climate change impacts accelerate and worsen, or where policy reaction is swifter and more substantial than currently priced in by the markets. Processes to assess risk should also be applied in relation to liabilities and the employer covenant. These considerations may potentially influence the time horizons selected.

104. As outlined in TPR’s Integrated Risk Management (IRM)[^104] guidance, risk identification should not be a one-off exercise. Further, TPR recommends that, as a minimum, trustees should consider conducting high level risk monitoring at least once a year. Trustees should increase the frequency of monitoring if risk levels approach pre-determined risk appetites.

Processes for managing climate-related risk

105. Trustees must ensure they have processes in place for the purpose of enabling them to manage effectively climate-related risks which are relevant to the scheme. Trustees should consider whether new risk management tools are needed to support management of climate-related risks or whether existing tools can be adjusted to reflect the unique characteristics of these risks.

106. Trustees should consider the time horizon over which risks are traditionally identified and assessed and whether that time horizon is sufficiently long-term to take account of the timescale over which climate-related risks need to be considered (see paragraphs 43-46), or whether it should be extended. It is not necessary to extend the timescale beyond the time horizon over which current members’ benefits will be paid (for DB), or for which current members’ monies will be invested (for DC).

Integration of climate-related risk

107. Whatever climate-related risks are financially material to the pension scheme, trustees must embed management of these into the scheme’s wider risk-monitoring and management processes. There are four key principles trustees should consider:

- Interconnections: Integrating climate-related risks into the scheme’s existing risk management framework requires analysis and collaboration amongst those undertaking governance activities and, if relevant, with asset managers, investment consultants and DB funding and covenant advisers

- Temporal orientation: Climate-related physical and transition risks should be analysed across short, medium, and long-term time frames for operational and strategic planning. Analysis of physical risks, in particular, may require extension beyond traditional planning horizons