Expanding access to naloxone: summary of feedback

Updated 24 January 2024

Introduction

Why changes are needed

Naloxone is a drug that reverses the effects of an opioid overdose, and so can help to prevent overdose deaths. Naloxone is a prescription only medicine regulated by the Human Medicines Regulations 2012 (HMRs). This means that there are controls on who can legally administer, sell and supply naloxone.

There are various exceptions to the regulations, which we described in more detail in the expanding access to naloxone consultation. These exceptions have made it easier for some drug treatment services to distribute both intramuscular (injectable) and intranasal (nasal) naloxone in recent years. But we are aware that the current regulations can still produce unnecessary barriers to using naloxone.

At the Drugs Ministerial Meeting on 17 September 2020, the Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Prevention, Public Health and Primary Care made a public commitment to consider amending the HMRs to allow naloxone to be more easily distributed to at-risk people who use drugs. Ministers from across the UK strongly agreed that the current legislation on naloxone needed to be reviewed.

As a result, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), the Department of Health in Northern Ireland, the Scottish Government and the Welsh Government consulted on new proposals to widen access to naloxone. The proposals included expanding the list of settings and individuals that can give out naloxone without a prescription or other written instruction.

Our intention is to make it easier for people who need naloxone to access it. This will help prevent at-risk people who use drugs dying from opioid overdose.

England

Since the consultation was launched, the UK government has launched a new 10-year drugs strategy. The strategy includes £533 million for England to support the government’s aim of delivering a world-class treatment and recovery system for people who experience drug and alcohol dependency. DHSC will support local areas to ensure that this extra funding means a full range of evidence-based interventions are available in every area. This will include interventions to reduce harm and save lives, such as access to naloxone.

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, the Department of Health has published a new 10-year substance use strategy, Preventing Harm, Empowering Recovery. Supported by 5 population-level outcomes, the vision of the strategy is that:

People in Northern Ireland are supported in the prevention and reduction of harm and stigma related to the use of alcohol and other drugs, have access to high quality treatment and support services, and will be empowered to maintain recovery.

The strategy contains a specific commitment and action to expand access to naloxone in Northern Ireland.

Scotland

In June 2020, Scotland introduced a temporary measure that enabled individuals other than drug treatment service workers to distribute naloxone to people at risk of overdose, and to their families and friends, as long as they were registered to do so with the Scottish Government.

The Lord Advocate put in place a statement of prosecution policy on supplying naloxone. This is time-limited to the period in which services are disrupted by the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. It aims to relax the rules around who can supply and distribute naloxone, to maximise its availability during this time.

A range of non-drug services are distributing naloxone in Scotland under this arrangement, including:

- community hubs

- sexual health services

- homeless services

- women’s services

Wales

Naloxone distribution continues to be an important part of the harm reduction approach in Wales. The Welsh Government provides funding for kits carried by the police and any kits stored in agencies.

In January 2021, the Welsh Government published a revised Substance misuse delivery plan (2019 to 2022) in response to COVID-19. This plan commits the Welsh Government to support the distribution of take-home naloxone and develop this in the community.

The Welsh Government works closely with partners to continually develop initiatives for distributing naloxone.

Current legislative framework

The Medicines and Medical Devices Act 2021 (‘the act’) received royal assent on 11 February 2021. Part 2 of the act confers powers to amend or supplement the law relating to human medicines.

Under section 45(1) of the act, a public consultation must take place before any regulations can be made using powers under the act, and this would include any legislative amendments to the HMRs.

Consultation process

The public consultation sought views on exempting certain additional individuals and services from regulations 214 and 220 of the HMRs with respect to the supply of injectable and nasal naloxone. Among other things, this could enable the exempted individuals and services to lawfully distribute naloxone without a prescription or other written instruction to a person “for the purpose of saving a life in an emergency”.

The specific individuals and services consulted on were:

- outreach and day services for people who experience homelessness or rough sleeping

- temporary or supported accommodation services for people with substance use disorders or people who experience homelessness or rough sleeping

- police officers

- drug treatment workers commissioned by police and crime commissioners (PCCs) to work in police custody suites

- prison officers (orderly officers and duty governors)

- probation officers

- registered nurses

- registered paramedics

- registered midwives

- pharmacists

Main findings

The consultation sought views on the extent to which respondents agreed or disagreed with the proposals. All questions were optional and gave respondents the opportunity to justify their answer or provide more information in a free text box.

In total, we received 704 responses (699 via GOV.UK and 5 via email). Several organisations sent more information via email to support their survey responses. We received responses from all 4 UK nations.

Of the 704 responses, just under a third (218) were from organisations and just over two-thirds (486) were from individuals. The organisations included:

- charities

- professional representative bodies

- NHS trusts

- drug treatment service providers

- commissioners

- private companies

- community interest companies

- housing organisations

- criminal justice sector representatives

Of the individuals who responded, 27% said that they had lived experience, and 87% said they had professional experience of drug use, drug overdose, or naloxone use.

There was strong support for the proposals in the consultation. The main findings were that:

- 63% agreed that naloxone is difficult to access in the event of an overdose

- over 90% agreed that outreach and day services, temporary or supported accommodation services, drug treatment workers, police officers, prison officers, nurses and paramedics should be able to supply naloxone without a prescription

- support for midwives being able to supply naloxone without a prescription was slightly lower but still very high, at 88%

- most respondents who reported that they represented the professions and services that we consulted on thought it was ‘highly likely’ or ‘somewhat likely’ that they would hold a stock of naloxone if the regulations were changed

- 77% agreed that labelling requirements should not apply when naloxone is given by services without a prescription

- over 80% agreed that allowing the professions and services that we consulted on to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription would help reduce overdoses and drug-related deaths (this figure was over 95% for several of these individuals and services)

- more respondents thought there are risks associated with administering injectable naloxone (34%) than thought there are risks associated with administering nasal naloxone (20%)

Due to an error with the survey question, we have excluded pharmacists and probation officers from the analysis. We explain this in more detail in section 3.2.

You can find a more detailed summary of the consultation responses below, including a selection of anonymised comments that provide insight into respondents’ views on some of the proposals.

Not all respondents answered every question, but the response rate for the multiple-choice questions was high, ranging from 93% to 99%. For the free text questions, the response rate was lower and more varied. So, we have provided the response rate for individual questions separately in section 3 below where relevant.

We have presented the findings based on the total number of responses to each question, with blank responses removed. Unless otherwise stated, any figures that describe the level of agreement to a question include both ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ responses. Figures that describe the level of disagreement include ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ responses. All questions also contained a ‘neither agree nor disagree’ option.

Summary of responses

Access to naloxone under the current regulations

We asked, “to what extent do you agree that the current regulations mean naloxone is difficult to access in the event of an overdose?”

Nearly two-thirds (63%) of respondents agreed that naloxone is difficult to access in the event of an overdose. This is compared to 16% who disagreed that access is difficult.

Several respondents noted the positive changes that previous amendments to the HMRs have brought in recent years (in 2015 and 2019), but it is clear there are still barriers to accessing naloxone.

Respondents made a distinction between access to naloxone for drug treatment services, which they thought was relatively easy, and for other organisations and services, which is much harder. Respondents also highlighted some of the limitations of only drug treatment services having wider access to naloxone. This is because most of these services have restricted operating hours of 9am to 5pm on weekdays, and many people who misuse drugs are not in contact with these services at all.

Other respondents talked about the variation and inconsistency in access that the current regulations can produce. Some felt the regulations are unclear and difficult to follow and create “undue caution” and a “lack of confidence” among people involved in setting up local arrangements to help access naloxone.

Some respondents mentioned variation between services and areas, and even among different staff members at the same service, in their willingness to provide naloxone to people who are likely to witness an overdose. A small number of responses said that only named or specific people were able to issue naloxone. This suggests that even if the service can access naloxone, there can be other administrative and institutional barriers that prevent them distributing it more widely.

Several respondents felt that the changes proposed in the consultation would ease the current concerns about setting up local agreements by giving services “permission” to access naloxone. Respondents said it would make it easier to get a supply of naloxone to give to people at risk of an opioid overdose.

Respondents also raised some other practical barriers to accessing naloxone, including:

- individual local authority funding, which can produce variation across areas

- the supply and price of nasal naloxone

- an “overly complex” chain for “supply, purchasing and distribution” that means treatment services are the “single source of distribution in the system” that all other organisations rely on

Settings and individuals that should be able to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription or other written instruction

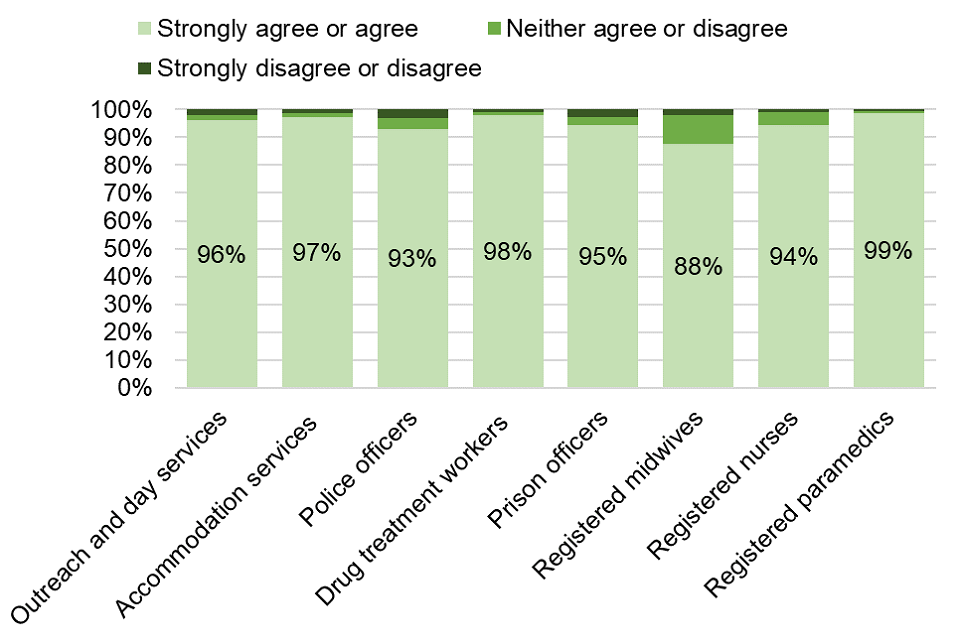

We asked, “to what extent do you agree that the following settings/individuals should be able to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription?” Responses are shown below in figure 1.

Figure 1: level of support for each service or profession being able to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription

Figure 1. Level of support for each service or profession being able to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription

There were very high levels of agreement (over 95% of respondents) that outreach and day services, temporary or supported accommodation services, drug treatment workers, and paramedics should be able to supply naloxone without a prescription.

There were also high levels of agreement (over 90% of respondents) for police officers, prison officers, nurses and paramedics to be able to supply naloxone without a prescription. Support for midwives was slightly lower but still high, at 88%.

We have excluded pharmacists and probation officers from the analysis for this question due to data quality concerns. There was a technical issue with the survey platform hosting the consultation and the response options for probation officers and pharmacists were provided in reverse order to the other settings. This is likely to have caused some respondents to select a different response from what they intended to (selecting ‘strongly disagree’ or ‘disagree’ instead of ‘strongly agree’ or ‘agree’, or vice versa). This has compromised the validity of the findings for pharmacists and probation officers for this question. This technical issue was confined to question 2. No other consultation data was affected.

Just over three-quarters of respondents also provided a free text answer for question 2. We analysed these responses and found that many respondents expressed support for pharmacists being able to supply take-home naloxone. This is because of many pharmacies’ convenient locations and opening hours. It is also based on the fact that pharmacists and pharmacy teams already see people who use drugs on a regular basis through substitute prescribing and needle and syringe programmes. Respondents also felt that this level of contact can produce trusting relationships between pharmacists and people who use opioids.

The consultation responses did not contain much information or views about probation officers. So, we spoke to HM Prison and Probation Service and probation officers to understand their support and their stakeholder’s support for these proposals, and potential concerns about them. We will continue to engage with these professions, and others who would be affected by any changes made because of this consultation.

The main themes that emerged from the free text responses to this question were that:

- naloxone should be available in any situation, to people in any profession, where overdose might occur

- naloxone should be available as widely as possible, including in more settings than were explicitly consulted on

- widening access saves lives

Free text responses to this (and other consultation questions) also said that enabling a wider number of services and individuals to supply take-home naloxone would particularly help to reach people who are not in contact with treatment services. Some respondents were concerned that not doing so would be a “missed opportunity to reduce deaths from overdose”.

Several respondents noted that naloxone provision should be wider than the existing regulations allow (that is, only certain types of drug treatment services) because, as one said:

Many individuals who would benefit from naloxone do not attend [drug treatment services] as they feel they do not have a problematic drug issue and therefore do not need to. However, individuals from this cohort will encounter other professional services from time to time, be that police officers, medical professionals or those others listed [in the consultation].

Stocking and supplying naloxone

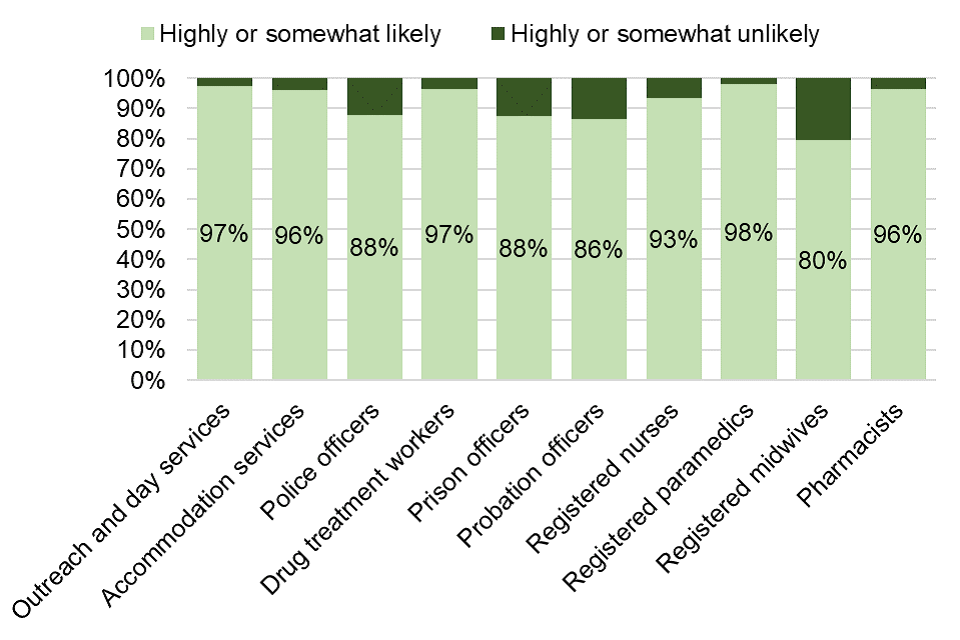

We asked, “if you represent any of the following services or individuals, do you think it is likely that they would keep a stock of and supply naloxone if the regulations were changed such that they were eligible to do so?”

For each of the services and professions we consulted on, the number of respondents who selected ‘I do not represent these individuals’ was around half. Figure 2 shows the responses of those who reported that they did represent the services and individuals listed. Most of these respondents (over 80% across all the professions, over 95% for outreach services, temporary or supported accommodation services, drug treatment workers, paramedics and pharmacists) thought it was highly likely or somewhat likely that a stock of naloxone would be held by the services or individuals listed if the regulations were changed.

Figure 2: perceived likelihood that each service or profession would keep a stock of naloxone and supply it if regulations were changed

Figure 2. Perceived likelihood that each service or profession would keep a stock of naloxone and supply it if regulations were changed

From the responses, the most common opinion was that frontline workers who encounter overdoses are prepared to use naloxone and that allowing them to do so would save lives.

One respondent said:

All organisations, and the staff that work for them, who might have contact with individuals that may come across overdose situations should be able to supply take home naloxone without need for prescriptions.

Respondents noted that wider distribution of naloxone would support the ‘no wrong door’ and ‘make every contact count’ strategies. These strategies seek to make the most of any interaction a person has with health and care services and professionals, to encourage them to take steps to improve their physical and mental health. These strategies also aim to ensure that as many different services and professionals as possible can help people find the support they need. Through this approach, naloxone could be supplied to opioid users in whatever which part of the emergency, health, substance misuse treatment, social care or criminal justice system they engage with.

Respondents also commented that distributing naloxone creates a point of contact with otherwise hard-to-reach people. Allowing more services to distribute naloxone would increase contact with this population, which might encourage them to engage with drug treatment and other healthcare services.

Respondents expressed some concern about increasing the number of services eligible to distribute naloxone. They felt that any new services and locations would need training and support, including training for frontline staff to correctly identify an overdose. Several respondents were concerned about the unknown effects of administering naloxone during pregnancy.

Other settings that should be able to obtain or supply naloxone

We asked, “are there any settings not explicitly cited in the above questions that you would support being able to obtain or supply naloxone?”

Respondents suggested a very broad range of additional settings in response to this question. We grouped the settings suggested by respondents by theme, for example, grouping together all recovery-related settings like mutual aid groups and peer networks. This resulted in 101 different groups of settings.

No single type of setting featured in the majority of responses. But the most popular suggestion was for family and friends of people with substance misuse problems being able to obtain naloxone, and the services supporting them being able to supply it.

A theme that was present in responses to several of the consultation questions was to make wider changes than just expanding the exemptions in the HMRs to the individuals and settings that we consulted on. The breadth of the additional settings suggested in response to this question provides further support for the idea of wider changes.

Respondents also suggested that the UK government should assess the effect of the Lord Advocate’s statement of prosecution policy in Scotland, which relaxed the rules around who can supply and distribute naloxone, and make similar changes across the UK.

Some respondents felt that making naloxone more widely available, with more people and services providing it, would also ‘normalise’ it as a health intervention. Many respondents suggested naloxone should be as “widely available as automatic defibrillators have become in public settings”, or first aid kits.

Labelling requirements

We asked, “to what extent do you agree that the labelling requirements on prescription-only medicines, such as the name of the individual to whom the medicine is being supplied, should be disapplied when naloxone is given out by services without a prescription?”

Over three-quarters of respondents (77%) agreed or strongly agreed that labelling requirements should not apply when naloxone is given by services without a prescription.

Reducing drug-related deaths

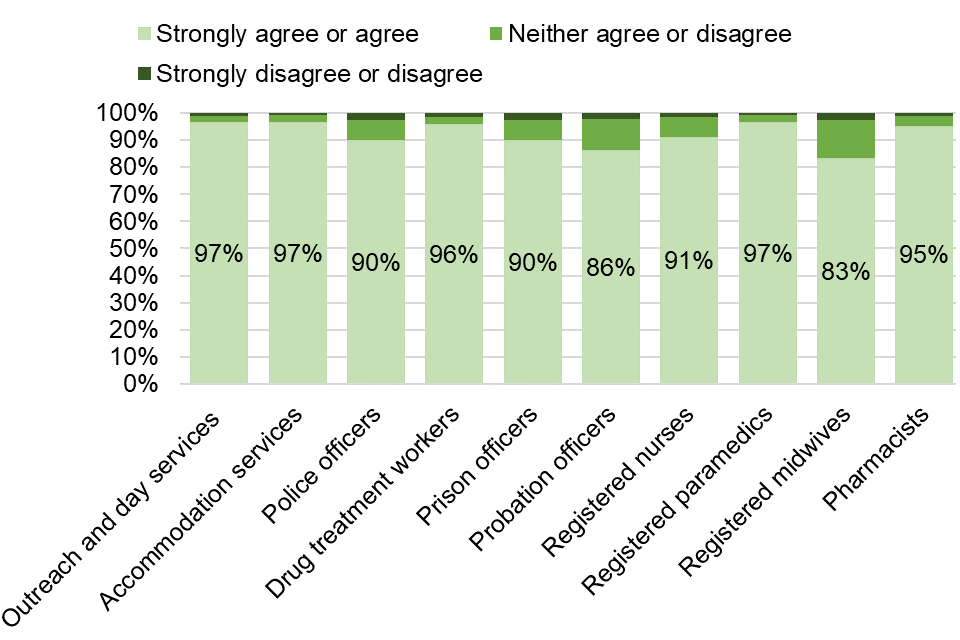

We asked, “to what extent do you agree that allowing the below settings or individuals to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription would help to reduce the incidence of opioid overdose and drug-related deaths?”

Responses are shown below in figure 3.

Figure 3: level of agreement that allowing each service or profession to supply naloxone would reduce the number of overdoses and drug-related deaths

Figure 3. Level of agreement that allowing each service or profession to supply naloxone would reduce the number of overdoses and drug-related deaths

More than 80% of respondents agreed that allowing services to supply take-home naloxone without a prescription would help reduce overdoses and drug-related deaths. Agreement was particularly high (over 95% of respondents agreeing) in responses for:

- outreach services

- temporary or supported accommodation services

- drug treatment workers

- pharmacists and paramedics

Most of the free text responses included the theme that widening access to naloxone saves lives. The next most prevalent theme in responses to this question was that naloxone should be available in any setting, and to any person, that might encounter an overdose.

A common observation was that people who use opioids often do not access healthcare through the typical channels. Respondents argued that naloxone should be available across all possible services, without prescription, to ensure that people can access it. Respondents also felt that providing naloxone creates an opportunity to make contact with hard-to-reach people.

One respondent said:

Offering naloxone allows us to open up these conversations with people, build trust in services and relationships, which are fundamental to any intervention.

Some respondents expressed concern about the burden of additional duties and administration for the staff in services that would be distributing naloxone.

Injectable and nasal naloxone: risks and benefits

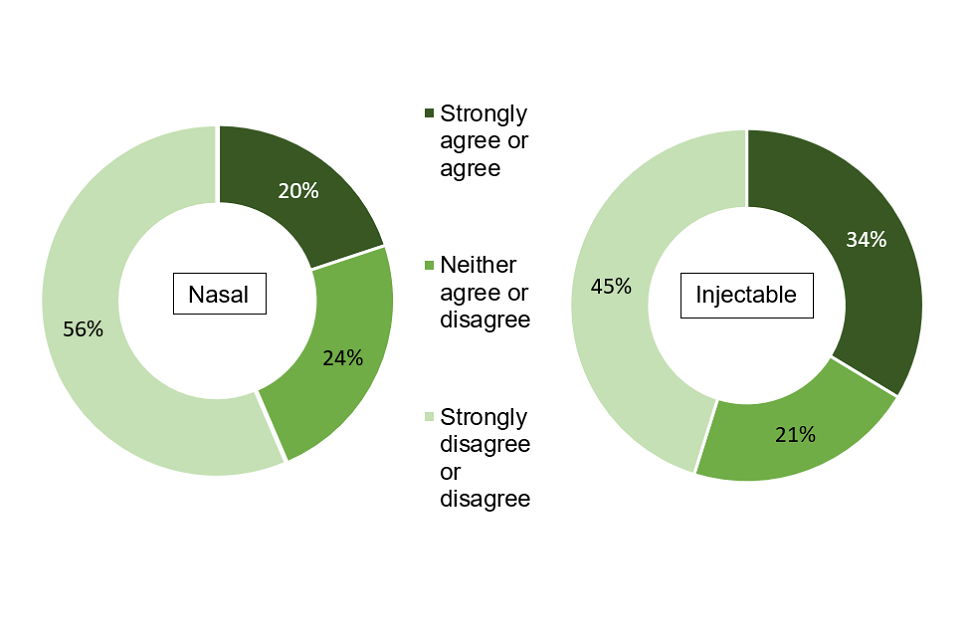

We asked, “to what extent do you agree that there are risks associated with the administration of naloxone in either nasal or injectable form?”

Responses are shown in figure 4 below.

Figure 4: level of perceived risk associated with nasal and injectable naloxone

Figure 4. Level of perceived risk associated with nasal and injectable naloxone

Some respondents (a quarter of respondents for nasal naloxone and a fifth for injectable naloxone) neither agreed nor disagreed that using naloxone carries risks. Some people felt there were no risks at all.

About a third of respondents (34%) agreed that there was a risk associated with administering injectable naloxone compared to a fifth (20%) for nasal naloxone. Just over half (56%) disagreed that there were risks associated with nasal naloxone while just under half (45%) disagreed for injectable naloxone.

In the free text responses, respondents noted risks with both forms of administration, although many felt these were minimal or limited, particularly compared to the risk of a fatal overdose.

Specifically for injectable naloxone, respondents were concerned about:

- needle stick or sharps injuries to the person administering the naloxone and anyone else close by

- the risk of the needle being misused if not properly disposed of

- potential spread of blood-borne viruses

- the risk of infection and bruising or muscle damage at the injection site

Respondents highlighted other considerations for injectable naloxone, including people who do not inject opioids not wanting to be injected or carry needles:

One respondent said:

intramuscular naloxone requiring an injection can be a barrier to its wider uptake, especially among people who do not inject drugs. There is a stigma attached to carrying needles and evidence has shown that people remain hesitant to carry and use them.

Some respondents felt that nasal naloxone is a better choice compared to the injectable form, as the risks around its administration are smaller. But, respondents also felt that acute withdrawal is more likely to occur after using the nasal spray, as the dose of naloxone delivered in a single dose is higher than in a single injectable dose.

The main risk that respondents mentioned for both forms of naloxone is that it can bring about withdrawal symptoms, which can cause confusion, aggression and even violence from the person who was treated with naloxone. This could pose a risk to the person administering the naloxone. For the person receiving the naloxone, the main risks of withdrawal that respondents mentioned were respiratory arrest and cardiac arrest. Other risks mentioned included risks to people with unknown heart conditions, risks to an unborn child in a pregnant person and allergic reactions.

We included this question in the consultation to help us understand the perceived risks around the 2 different forms of take-home naloxone. Both the injectable and nasal forms are evidence-based, effective and licensed for use in the UK.

Many respondents said that people who might have to administer naloxone should be trained and educated to mitigate risks. Respondents mentioned specific important areas for training including:

- awareness of the potential for naloxone to wear off more quickly than the opiates the person took, causing them to overdose again

- dosing knowledge, such as the risk of administering too large an initial dose of naloxone and what to do if the naloxone is not as effective as expected (possibly due to the patient having other drugs in their system)

- awareness of the other aspects of dealing with an opioid overdose, such as needing emergency assistance, needing oxygen, and monitoring after administering naloxone

We analysed this question further by cross-referencing responses to this question with responses to question 9, “if your organisation distributes naloxone, have you received training on how to use it?” (see tables 1 and 2 below).

This showed that, for both nasal and injectable forms of naloxone:

- people who had not received training on how to use naloxone were more likely to agree that there are risks associated with its administration

- people who had received training were more likely to disagree that there were associated risks

This shows that training may reduce the perception of risks associated with administering either form of naloxone.

Table 1: respondents perceived risk of injectable naloxone and training status

| Training received | Agree that there are risks | Disagree that there are risks | Neither agree nor disagree that there are risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 26% | 55% | 19% |

| No | 60% | 3% | 37% |

| Not applicable | 43% | 34% | 23% |

Table 2: respondents perceived risk of nasal naloxone and training status

| Training received | Agree that there are risks | Disagree that there are risks | Neither agree nor disagree that there are risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 16% | 64% | 19% |

| No | 43% | 30% | 27% |

| Not applicable | 24% | 45% | 31% |

There was a mixed opinion from respondents about the risks of naloxone but a strong sense that the benefits of administering naloxone outweigh any risks associated with either the medicine or how it is administered.

In 2012, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs’ review of naloxone’s availability concluded that “the balance of benefit around providing naloxone, and the opportunities for reversing overdoses and saving lives, is greater than any potential risks”. This seems to be an opinion shared by many respondents to the consultation.

We also asked, “is there anything else you would like to share on the risks and benefits of naloxone which you have not provided in answers above?”

Of the 285 responses we received to this question:

- 39% said that naloxone saves lives

- 25% wanted the government to go further than just widening existing exemptions to the groups listed in this consultation

- 13% said that the benefits of providing naloxone outweighed the risks

Respondents also thought that the stigma of carrying and using naloxone is a barrier to it being used. Some felt that current opioid users might fear that receiving take-home naloxone would result in criminalisation, by putting them “on the police’s radar”. Others felt that people who previously used opioids and who are at high risk of relapse and overdose might reject naloxone because of its association with “traditional heroin users”. Again, respondents noted that stigma is particularly associated with intramuscular naloxone, with some suggesting that the friends and families of people at risk of overdose may be reluctant to carry it because of its “association with injecting drug use”.

Safeguards

We asked, “what safeguards do you think should be required in the settings from which naloxone is supplied?”

The 2 main themes raised in response to this question related to training and protocols around the safe storage and distribution of naloxone.

Most respondents (67% of the 524 respondents who answered this question) agreed that training for staff and service users in the use of naloxone is important. Responses covered safeguarding issues around administering and supplying naloxone. For example, respondents specifically highlighted the need for training on how to recognise an overdose. Some also suggested that basic CPR and life support training could be needed, including information on contacting emergency services after giving someone naloxone.

Respondents also mentioned the need for services to develop patient pathways that include onward referral to drug and alcohol treatment services or other sources of support, such as follow-up support.

Some respondents felt that training should be regularly reviewed and repeated to make sure that people who might have to administer naloxone keep their knowledge up to date. This will help the person receiving naloxone to have confidence in the person administering it. Some respondents also felt that it would be worth including naloxone training in staff objectives and competency frameworks.

Some respondents believed that people who had administered naloxone should have the opportunity for a debrief because the experience can be traumatic. It was suggested that a suitable forum to discuss best practices and concerns would be useful.

Another repeated theme was the need for clear and safe protocols (local or national) and facilities for handling, storing and disposing of naloxone by people responsible for supplying it. This would include:

- systems to monitor and record supply and use

- a register of who has been given take-home naloxone

- recording batch numbers and replenishing any out-of-date stock

Some respondents mentioned legal liability training, risk assessment and the need to get appropriate consent to supply naloxone.

Some respondents said that no further safeguards were needed. But if safeguards were in place, they should not be too onerous, as this could inhibit the supply of naloxone. A small number of respondents felt there should be age restrictions on who can access naloxone. For example, this could mean not allowing access for anyone aged 16 and under, unless there are exceptional circumstances.

Naloxone training

We also asked, “if your organisation distributes naloxone, have you received training on how to use it? If ‘yes’, do you believe said training is sufficient?”

Of the 386 respondents who answered this question saying they had received training, 84% felt that it was sufficient, with 11% highlighting the need for regular refresher training.

Responses showed that some NHS organisations and third sector bodies already provide training on how to use naloxone. Some stressed the importance of non-clinical trainers needing extra training as they lack specialist knowledge. Respondents also highlighted the benefits of peer-led training. Some respondents called for guidance on training and said that it should be tailored for specific audiences and should include training for both nasal and injectable naloxone.

We also asked, “how easy do you think it would be to expand this training to additional settings?”

Of the 340 respondents who answered this question, 75% felt that training could be easily expanded to more settings. Some respondents believed extra resources would be needed to expand provision.

Some respondents believed that training could be easily expanded for both injectable and nasal naloxone, though not all respondents specified the type of naloxone. Some respondents specified some people that may prefer nasal due to a fear of needles. They also thought a fear of needles, stigma and general reluctance could be barriers to training. These people would need extra support to overcome these barriers.

Respondents felt that training is or should be straightforward, so it is accessible to people that need it. Eleven per cent of respondents to this question felt that training could be easily delivered online. Many expressed satisfaction with online training, although some believed it should also be supplemented with practical sessions, particularly for injectable naloxone.

Equality

We asked, “do you think the proposals risk impacting people differently, or could impact adversely on any of the protected characteristics covered by the Public Sector Equality Duty set out in section 149 of the Equality Act 2010 or by section 75 of the Northern Ireland Act 1998?”

Of the 335 people who responded to this question, 217 (65%) said that the proposals consulted on do not risk impacting people differently. A further 50 people (15%) said maybe the proposals could impact people differently, or that they did not know, were not sure, or did not feel well placed to comment on this question. A very small proportion (2%) of people who responded felt that the proposals did risk impacting people differently.

Several respondents said that increasing the types and number of services that can supply naloxone is likely to reduce barriers to access and help to reduce inequalities. Others felt that every effort should be made to break down specific barriers to naloxone access, such as for women and people in ethnic minority and other minority communities.

Next steps

The proposals we consulted on were to enable more people in different roles and settings to legally be able to supply take-home naloxone to people at risk of overdose, without a prescription or other written instructions.

Analysis of the responses to this consultation shows there is overwhelming support for allowing more organisations and individuals to supply take-home naloxone.

The Department of Health and Social Care is committed to expanding access to naloxone and we will work with the devolved governments to examine policy options to take this forward over the next few months. We will publish a full government response to this consultation by the end of this year.

Whatever the outcome of this work, the UK government and the devolved governments will consider the equality impacts suggested in response to this consultation when taking forward any proposals to expand access to naloxone.