Consultation impact assessment

Updated 29 January 2024

Applies to England, Scotland and Wales

| Lead Department/Agency | Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) |

| Planned coming into force /implementation date | To be confirmed |

| Origin (Domestic/EU/Regulator) | Domestic |

| Policy lead | Gavin Forsdyke |

| Lead analyst | Zaynab Yasmeen |

| Departmental Assessment | Self-certified |

| Total Net Present Social Value (over 10year period) | £-2.4m |

| Equivalent Annual Net Direct Cost to Business (EANDCB)(over 10 year period) | £0.3m |

| Business Impact Status | Non-Qualifying Regulatory Provision |

1. Summary - Intervention and impacts

1.1 Policy background and issue, Rationale for Intervention and Intended Effects

Lack of long-term planning and poor risk management among some trustees in defined benefit (DB) occupational pension schemes presents the risk that their members will not receive the full benefits they have been promised. To reduce the risk to members the Pension Schemes Act 2021 requires trustees of DB pension schemes to determine a funding and investment strategy for ensuring that pensions benefits can be provided over the long term.

The 2018 White Paper[footnote 1] found that the scheme funding system was working well for the majority of (DB) pension schemes, but good practice was not universal. It proposed a package of measures to improve decision-making and governance for all schemes by delivering clearer more enforceable scheme funding standards, with a greater focus on risk management and longer-term planning.

Some schemes were taking a short-term view of funding requirements and may not be effectively setting an investment strategy and managing the long-term obligations of the scheme and therefore inadequately anticipating or managing scheme funding risks. Severely underfunded schemes present a risk to members, the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) and ultimately other PPF levy payers. If the sponsoring employer of the scheme becomes insolvent then the scheme may have to enter the PPF, resulting in some members potentially losing 10% or more of their benefits[footnote 2]. Therefore, government intervention is necessary to ensure that schemes are making investment decisions in a way which results in the highest probability of members receiving their pensions in full. The draft regulations set out the key principles for setting and revising the funding and investment strategy and detail the evidence that must be provided in the statement of strategy. The practical details and metrics will be provided by The Pensions Regulator (TPR) in a revised DB Funding Code of Practice. These changes are necessary to raise standards and to ensure all schemes plan for the long term and mitigate risks in a maturing DB landscape. They are also needed to support TPR’s scheme funding powers by making clearer what all DB schemes are required to do.

1.2 Brief description of viable policy options considered (including alternatives to regulation)

We considered the following options:

Option 0: Do nothing

Leaving the system unchanged would not deliver improvements to the scheme funding regime. Funding standards would lack clarity, which would continue to lead to poor decision making by schemes, and TPR would continue to find them difficult to enforce. Although many schemes have a long term objective (LTO) in place, evidence[footnote 3] suggests that a sizeable minority do not. As a result, members of these schemes would be at risk of poorer retirement outcomes, because of poor decision making outside the scope of existing TPR powers.

Option 1: Making the DB Funding Code of Practice enforceable

Making the DB Funding Code of Practice[footnote 4] enforceable would not resolve the problem of lack of clarity and could make things worse by giving statutory force to something that was already unclear. In addition, TPR has already taken steps to support trustees’ voluntary application of the Code, and this has not been enough to suggest that making it enforceable would be effective.

Option 2 (preferred option): Introduce secondary legislation to provide detail of the requirements in the Pension Schemes Act 2021 to:

-

Impose a duty on trustees to have a funding and investment strategy so that as a minimum by the time the scheme is significantly mature there is low dependency on the sponsoring employer and investments have high resilience to risk.

-

Require trustees to set out the funding and investment strategy in a statement of strategy that is signed by the chair of the trustees on behalf of the trustee board, who must appoint a chair if they do not already have one.

-

Introduce a new regulation, to be used alongside existing regulations to support clearer funding standards by clarifying key terms such as “appropriateness” and “prudence”, in secondary legislation

1.3 Preferred option: Summary of assessment of impact on business and other main affected groups

We will not be able to determine the full impacts and costs that are introduced by these legislative changes until the detail of all components of the regime are known – this includes the Pensions Regulator’s revised Defined Benefit Funding Code of practice which will contain more detailed guidance and specification on how to comply with legislative requirements in setting the Funding and Investment Strategy. A Business Impact Target (BIT)[footnote 5] will be completed by TPR following their consultation to accompany the revised DB Funding Code of Practice. At this stage, we give a high-level assessment of possible business and other impacts. Once that is completed, we will update our impact assessment of these legislative changes accordingly.

We anticipate there to be minor familiarisation and implementation gross cost to business, partially offset by savings for schemes associated with improved clarity of the requirements.

The impact of any changes to deficit repair contributions[footnote 6] (DRCs) as a result of the funding and investment strategy will be included in TPR’s BIT assessment. These costs would result from legislative changes however it is the TPR revised DB Funding Code of Practice which will determine the scale of these costs.

Departmental Policy signoff (SCS):

Fiona Frobisher

Date: 21/03/2022

Economist signoff (senior analyst):

Andrew Ward

Date: 24/02/2022

Better Regulation Unit signoff:

Prabhavati Mistry

Date: 24/02/2022

2. Additional detail – policy, analysis, and impacts

2.1 Setting the long term objective - costs and benefits to businesses

1. Background information – scheme liabilities; and scheme running strategies and objectives

DB pension schemes provide pensions and other benefits usually based on final salary or career average salary and length of service, as set out in the scheme rules. Risks, including longevity risk and investment return risk[footnote 7], are borne by the scheme and its sponsoring employer not members. A scheme’s funding position is evaluated annually as required by legislation and an actuarial valuation is completed at least every three years.

A scheme’s funding position is the difference between the assets the scheme holds and its liabilities (i.e. how much it is expected to have to pay out to its members). DB liability (and hence funding position) estimates inherently carry an element of uncertainty as, for example, it is impossible to estimate future longevity or investment returns with certainty. There are a range of DB scheme liability measures, each designed and used for a specific purpose. They differ in the way the assumptions needed to assess scheme liabilities (like future investment returns) are made. The most relevant measures for the purposes of this impact assessment are the Statutory Funding Objective (SFO) and the International Accounting Standard Nineteen (IAS19):

-

Statutory Funding Objective: The “statutory funding objective” requires schemes to have sufficient and appropriate assets to cover its “technical provisions”. A scheme’s “technical provisions” (TPs) are defined as the amount required, on an actuarial calculation, to make provision for the scheme’s liabilities. Trustees and employers agree the methods and assumptions (which must be prudent) used in the actuarial calculation. The Pension Schemes Act 2021 introduces a new requirement for a scheme’s TPs to be calculated in a way that is consistent with the funding and investment strategy as set out in the statement of strategy.

-

International Accounting Standards 19: This valuation method is used when companies report their annual accounts. The methodology is set on a common basis to facilitate international comparisons.

Details of all four widely used valuation methods are set out in TPR’s ‘Understanding the different ways of valuing a defined benefit scheme’.[footnote 8]

Scheme liabilities are a product of a range of factors including: the number of members; the amount of pension benefits and survivor benefits promised; and longevity. Some of these factors are not known and will be estimated by the scheme actuary using assumptions agreed by the trustees and the employer.

Existing good funding practice, encouraged by TPR’s current DB scheme funding code of practice and other guidance, already encourages schemes to have a LTO and to use an Integrated Risk Management model to consider risks to funding, investments and employer covenant in an integrated way. However, this good practice is not mandatory.

DB schemes may have different strategies and objectives regarding how they are run in the long-term (more detail and discussion can be found in the White Paper). Examples of an acceptable funding and investment strategy (referred to as a LTO in the White Paper) could be to:

-

Reach self-sufficiency at significant maturity with a funding and investment strategy that has high resilience to investment risk and low dependency on the sponsoring employer (the minimum requirement)

-

Buy-out by a set time

-

Enter a consolidator vehicle within an agreed timeframe

The existing good funding practice, facilitated by TPR, already encourages schemes to have a LTO in place. However, it is not mandatory.

2. The baseline / counterfactual

Most DB schemes already have a LTO (sometimes known as a target) in place. TPR’s DB Research 2018[footnote 9] found 76% of trustees and 79% of employers responded that schemes closed to future accrual had in place a journey plan or long-term target, which leaves nearly a quarter that did not have an explicit long-term target. Surveys from pensions consultancies also tend to suggest that most schemes already have a LTO. For example, according to Aon’s Survey[footnote 10], which interviewed 170 schemes, only 8% did not have a long-term plan (but note that Aon’s clients may not represent the industry average).

Based on this evidence, we assume that 80% of DB schemes already have a LTO in place (a lower end estimate between the 76% TPR research and 92% Aon Survey). As this is a point in time estimate, we also assume that there is a constant proportion in the counterfactual over time. This assumption is based on signals suggesting that although the proportions of schemes with different objectives have been changing over recent years, the proportion reporting no or unknown objectives stayed broadly similar (e.g., 6% according to Aon’s survey 2015 and 8% according to Aon’s survey 2017).

However, as pointed out by TPR and referenced in the Department’s White Paper, schemes may well have a long-term plan but for some the plan may be largely aspirational and does not drive funding and Deficit Repair Contribution (DRC) commitment. Such schemes will need to adjust their funding plans and sponsoring employers will need to fund their schemes in line with their LTO. Any schemes with a LTO which is currently weaker than low dependency funding by significant maturity will need to set a stronger long-term target as part of their new funding and investment strategy and must be funded to that level. Employers are already required to fund the pension benefits and the new funding and investment strategy does not itself increase overall costs. But it may well bring forward contributions and increase costs in the short and medium term.

3. Business impacts

The proposed option will require schemes to set a funding and investment strategy for providing pension benefits over the long term. The 2018 White Paper referred to this as a LTO. The minimum requirement is low dependency funding[footnote 11] by significant maturity with a high resilience to investment risk. A minority of schemes which remain open to both further accrual and to new members, which are in a steady state and not maturing, will not move towards their long-term funding and investment targets.

The business impacts will mainly be for schemes whose TPs are currently weaker than what would be required for them to achieve low dependency funding at significant maturity with a high resilience to investment risk (i.e., they are on the wrong path).

These schemes will have to strengthen their TPs, potentially leading to the emergence of a deficit or an increase in deficit, and therefore potentially requiring DRCs or increased DRCs. Other impacts will arise for schemes currently taking too much unsupported risk (i.e., too weak an employer covenant and/or too mature).

The draft Regulations and TPR’s revised DB Funding Code of Practice will link the investment risk that a scheme should support to the strength of the employer covenant and scheme maturity. The Code will provide specific metrics for discount rates for the fast-track compliance route. The full impacts will be assessed as part of the TPR BIT assessment following the Code being consulted on.

3.1. Familiarisation and implementation costs.

There are 5,220 DB schemes in total[footnote 12]. As set out above, we assume 80% already have a LTO in place. That means the remaining 1,044 schemes[footnote 13] will be directly affected by the requirement. As some schemes may have a largely aspirational plan, which does not drive scheme management and funding decisions, we make an assumption about the number of schemes with a LTO that does not drive scheme management decisions. The percentage of schemes with a LTO that is only aspirational could be anywhere between 0% and 100%. In the absence of any certain information, we assume that half of those that already have a LTO have it as an aspiration – i.e., 2,088[footnote 14] schemes. Sensitivity analysis around this assumption is conducted below in section 3.1.1.

Initially, these draft Regulations set the requirements. However, the TPR Code will define the concepts quantitatively. It will look at what is low dependency (discount rate and other assumptions), significant maturity and high resilience to risk. TPR has undertaken an initial consultation and published an interim response[footnote 15]. TPR sought views on:

-

Their proposed approach to the revised DB Funding Code of Practice (twin-track compliance routes and their approach to prudence and risk-taking).

-

The key principles that they propose should underpin the Code.

-

Options for how these principles could be applied in practice through more detailed guidelines).

TPR will undertake a second consultation on the draft DB Funding Code of Practice itself and the guidelines it will contain, informed by the responses to this first consultation, their BIT (following the consultation) and legislation. At this stage, before the consultation and exact requirements and guidance are agreed, we cannot estimate familiarisation and implementation (and other) costs with certainty. As set out above, a full assessment will be in TPR’s BIT. For now, we give an illustration of the potential scale of impact only.

Through discussion with policy colleagues who have worked on the funding and investment strategy legalisation, the following assumptions have been made:

-

It will take a day (8 hours) for a trustee to read through and ‘absorb’ the changes.

-

One trustee from those schemes that already have a LTO will need to familiarise (sharing the information with other trustees of the scheme is then assumed to be negligible).

-

All trustees from those schemes that have none or just an aspirational LTO will have to familiarise.

There are 3.2 trustees per DB scheme[footnote 16], on average. Assuming an average hourly wage of a trustee of around £29 per hour[footnote 17] and applying the figures and assumptions above gives a cost estimate for familiarisation at the secondary stage of around £2.8 million[footnote 18].

Those schemes that do not already have a LTO will need to agree one, as part of determining their funding and investment strategy. It must be agreed with the employer which is likely to involve negotiations along with advice from the scheme actuary and advisers such as investment managers and covenant advisers. Associated costs are expected to vary on a scheme-by-scheme basis – from negligible for those that already have a clear strategy and just need to formalise it, to potentially material for those that are currently applying a short-term approach to scheme management (focused only on the next triennial review). At this stage, we cannot quantify the costs of determining and agreeing a funding and investment strategy due to the scheme specific nature and significant uncertainties involved. TPR will consult before any changes to the DB Funding Code are made and will analyse the impact on their BIT. As mentioned in the Department’s White Paper, TPR’s initial view based on their experience is that the governance costs of setting a LTO will be relatively low for those already adopting good practice and applying the principles set out in the DB funding code[footnote 19].

3.1.1. Familiarisation/Implementation Cost- Sensitivity Analysis

We have arbitrarily assumed that 50% of the schemes with a LTO have it as an aspiration rather than firm commitment. If all schemes with a LTO were to have this as an aspiration rather than firm commitment, all 5,220 schemes would have to go through the full familiarisation process with all trustees reading through and transposing the requirements. In this worst-case scenario, the total familiarisation cost to businesses would be approximately £3.9 million[footnote 20]. However, if all schemes with a LTO currently have it as a firm commitment, then only schemes who do not have a LTO currently would have to complete the full familiarisation process. As discussed above we assume 20% of schemes do not have a LTO currently, and therefore only 1,044 schemes would have to go through the full familiarisation process. This would result in total familiarisation costs of around £1.7m[footnote 21].

3.2. Ongoing costs and benefits.

As set out above, having a funding and investment strategy in place will not alter the schemes’ underlying pension liabilities. However, it may have some implications on scheme servicing and associated costs. Broadly speaking, clearer funding requirements, including a funding and investment strategy, may have the following implications on some schemes:

1) Scheme liability estimates and associated contributions.

Any estimates of scheme liabilities and hence net funding position inherently carry a degree of uncertainty (irrespective of the funding and investment strategy that is chosen). Those schemes that are currently targeting artificially low pension scheme liabilities and/or inconsistently with their LTO may need to revise their approach because of the proposed changes. In some cases, the change in the valuation may lead to an estimated deficit or a higher estimated deficit which will in turn require a recovery plan and DRCs or higher DRCs. This does not change the real (underlying) pension liability; but it alters the way the scheme is being serviced. In essence, some contributions into the scheme are brought forward, but the overall funding requirement over the scheme’s lifetime is not altered. However, applying discounting (as required by the HMT’s Green Book) to cash flows means there may be a net cost to business from contributions brought forward even if the overall scheme’s lifetime gross servicing cost remains unaffected. The impact of any changes to DRCs as a result of the funding and investment strategy will be included in TPR’s BIT assessment.

However, in some cases the scheme funding (and hence business cost) impact may be the opposite. Current lack of clarity in funding requirements and the scheme’s LTO means there is a risk that in some cases schemes may be applying overly cautious assumptions for the purposes of their valuations leading to inflated deficit estimates and associated costs. The requirement to have a specific funding and investment strategy and clearer funding standards more generally may lead to savings for some schemes.

In any case, clearer requirements are expected to reduce the amount of time and resources schemes need to invest in understanding what is required from them.

2) A change in the scheme’s chosen investment strategy.

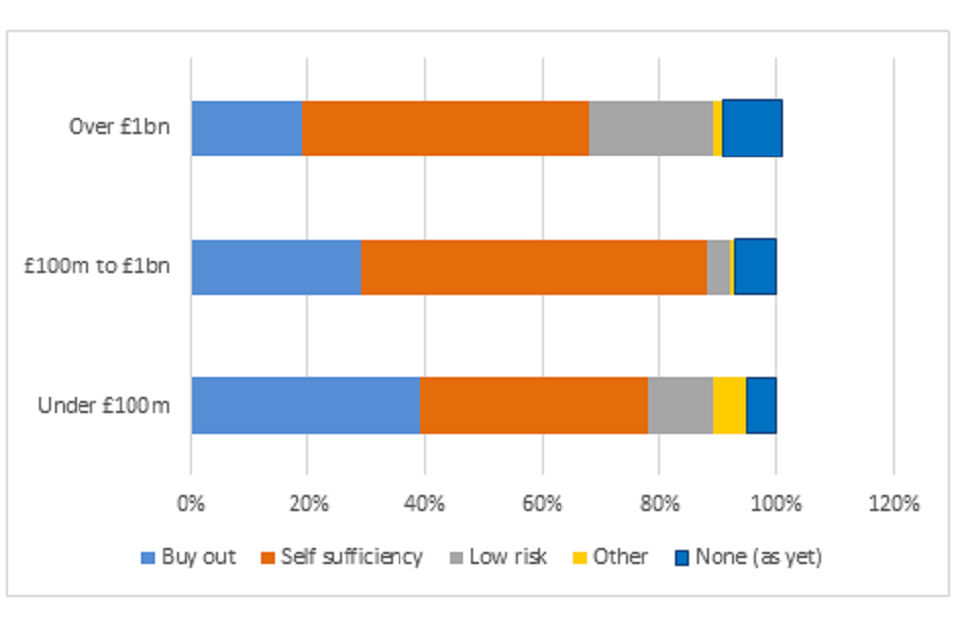

Existing evidence shows that many schemes are already considering different objectives depending on their scheme specific circumstances – see figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Distributions of LTOs by scheme sizes.

Source: Aon, Global Pensions Risk Survey 2017[footnote 22]

The Pension Schemes Act 2021 introduced the requirement for schemes to set a funding and investment strategy, including funding and investment targets. Once this is agreed, some schemes may need to revise their approach to funding and investments in order to achieve these targets.

They may need to change their investment strategy such that it is invested with a higher resilience to risk, reducing reliance on the employer covenant by the time the scheme is significantly mature. In this case it is possible that schemes receive lower investment returns (for example if they shift from equities to bonds), which could in turn lead to higher employer contributions or DRCs in some cases. However, this comes with an expectation of lower volatility and so less risk of substantially increased employer contributions or DRCs in the future if investment expectations do not materialise. The impact of any changes to employer contributions or DRCs as a result of investing with a higher resilience to risk, and hence assuming lower future investment returns in practice, will be included in TPR’s BIT assessment, along with other items that could impact employer contributions or DRCs.

3.3. Indirect impact – potential company balance sheet and credit rating impacts.

As set out above, there may be some schemes that will see an increase in their estimated DB pension liability as a result of the proposed requirement for a funding and investment strategy. However, when it comes to company balance sheets, the overarching DB liability measurement standard is IAS19 – which is based on a standardised set of assumptions for schemes. We anticipate that this should not affect the IAS19-based deficits since it is based on standardised assumptions that are not likely to be affected by the changes.

4. Costs and benefits to scheme members

There will be no costs to members as there will be no need for them to familiarise with the changes or implement them. The requirement is aimed to improve scheme funding. Better scheme funding is anticipated to improve the security of members’ pensions – i.e., to increase the likelihood of members ending up getting their pensions paid in full. It is not deemed proportionate to monetise this benefit.

5. Small and Micro Business Assessment (SaMBA)

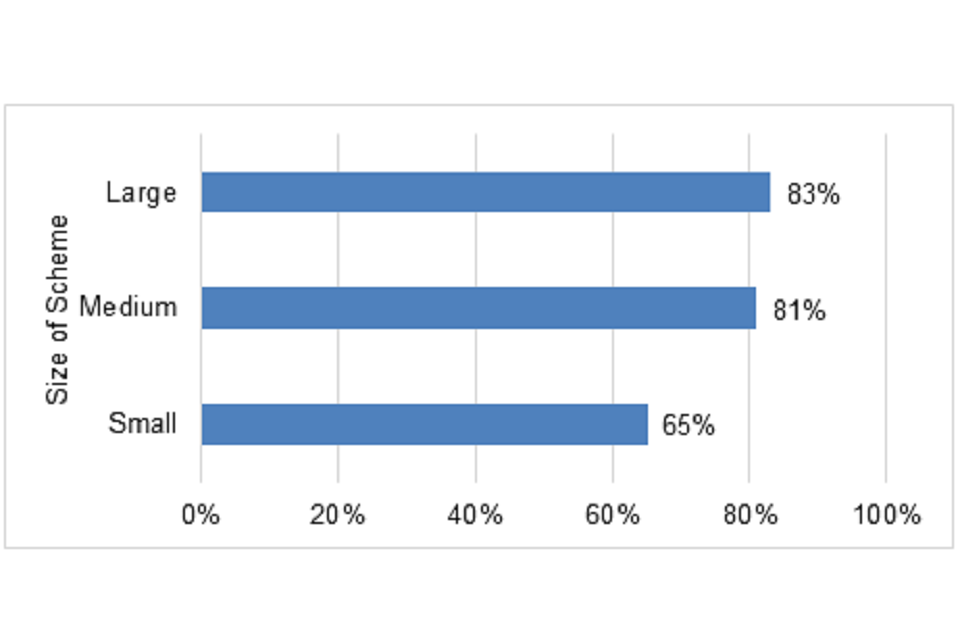

The costs to business fall on funded (private sector) DB pension schemes. As shown in Figure 2 below, small, and micro schemes are less likely to be compliant and as a result, are more likely to incur costs because of the proposed changes. In the case of DB schemes, the sponsoring employer will be responsible for these costs. Therefore, businesses that sponsor small schemes are more likely to incur a cost because of the proposed change. As such, it is possible that small and micro businesses that sponsor small DB pension schemes may be affected.

Figure 2: Proportion of trustees that reported having an aim for journey plan, by scheme size[footnote 23].

Source: TPR Defined benefit trust-based pension schemes research summary report.

However, DB schemes are predominately of medium or large sizes. As shown in the table below, 36% of DB schemes have less than 100 members and are therefore considered to be small. The proposed changes are expected to have a disproportionate impact on small schemes, however these schemes make up a smaller proportion of DB schemes in total.

Table 1: Estimated numbers of DB schemes split by size of scheme[footnote 24].

| Size of Schemes (The number of members) | Estimated 2021 Universe |

|---|---|

| 2-99 | 1,874 |

| 100-999 | 2,280 |

| 1,000-4,999 | 720 |

| 5,000-9,999 | 160 |

| 10,000+ | 186 |

| All | 5,220 |

Assessing the impact of the proposed changes here on this group is difficult. As it is not necessarily the case that small and micro pension schemes correspond to small and micro businesses. For example, large firms may run a DB scheme with only a few members. Similarly, small employers may enter their staff into a large DB scheme (as it is possible for a DB scheme to be sponsored by more than one employer). As this legislation will affect schemes depending on their compliance with the requirements in the baseline and small schemes are less compliant, employers that sponsor small schemes are likely to be disproportionately affected. There is currently no robust evidence to link pension scheme size to employer size and so it is difficult to accurately assess the impact on small and micro businesses.

There is information in the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) data set on the size of DB sponsoring employers with active members. This will only include those who are contributing to a DB pension so will exclude members who are in schemes closed for future accrual, but it helps to provide an indication of the size of DB sponsoring employers. The table below shows the proportion of private sector and not for profit active DB members by employer size.

Table 2: Proportion of active DB members, by employer size[footnote 25]

| Size of Employers | Proportion of DB members * |

|---|---|

| 0 | 0% |

| 1-9 | 2% |

| 10-49 | 10% |

| 50-99 | 4% |

| 100-499 | 14% |

| 500-999 | 9% |

| 1000+ | 61% |

| All sizes | 100% |

*Figures are rounded to the nearest 1%.

This information above provides evidence that the majority (88%) of active DB members are employed at businesses with 50 or more employees (and hence not a small or micro business). However, there is no information on the business sizes where there are no longer active members, and this does not provide information about the size of the scheme that the members are in. But it does provide an indication that most DB sponsoring employers are medium or large employers.

6. Monitoring and Evaluation

We will work with TPR and the industry in order to understand and review the post-implementation impact and publish a report setting out the conclusions of the review, in accordance with sections 28 to 32 of the Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 (c.26). This is to be done, no later than five years after the Regulations come into force, and subsequently at intervals of not more than five years.

Table 3: Estimated Direct Cost to Business

| Scheme Volumes | Cost** | How often | Assumptions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Familiarisation (Central Estimate) | 5,220 | 2,810,000 | One-off | All trustees[footnote 26] have to familiarise. Hourly wage of a trustee is around £29. For those without a LTO or only an aspirational LTO it will take eight hours to familiarise and transpose the regulations. Approximately 80% of schemes have a LTO. Arbitrarily assumed that 50% of those with a LTO have it as an explicit target. Those with a LTO as an explicit target only take 1 hour to familiarise. |

| Familiarisation (Lower Estimate) | 5,220 | 1,740,000 | One-off | All trustees have to familiarise. Hourly wage of a trustee is around £29. For those without a LTO or only an aspirational LTO it will take eight hours to familiarise and transpose the regulations. Approximately 80% of schemes have a LTO. Arbitrarily assumed all those with a LTO have it set as an explicit target. Those with a LTO as an explicit target only take 1 hour to familiarise. |

| Familiarisation (Upper Estimate) | 5,220 | 3,870,000 | One-off | All trustees have to familiarise. Hourly wage of a trustee is around £29. For those without a LTO or only an aspirational LTO it will take eight hours to familiarise and transpose the regulations. Approximately 80% of schemes have a LTO. Arbitrarily assumed that none of the schemes with a LTO have it as an explicit target. All have to do a full eight hours of familiarisation. |

** Costs all rounded to the nearest 10,000.

-

Defined benefit trust-based pension schemes research summary report and Global Pension Risk Survey 2019 ↩

-

Deficit repair contributions are contributions made by the employer to the scheme in order to address a technical provisions deficit, in line with the Schedule of Contributions and the recovery plan. ↩

-

Longevity risk refers to the risk that life expectancies and actual survival rates exceed pricing assumptions used by actuaries. Investment risk refers to the risks that should investments not perform as expected, that the actual returns will be lower than expected. ↩

-

TPR – Understanding the different ways of valuing a defined benefit scheme ↩

-

Defined benefit trust-based pension schemes research summary report page 5., DB Schemes Research Final Report ↩

-

‘low dependency on the employer’ is defined as meaning that the scheme is not projected to rely on further employer contributions in respect of accrued rights. This means that the scheme must have sufficient low risk assets to provide for pension rights already accrued. ↩

-

5,220*0.20 = 1,044 ↩

-

((5,220-1,044) x 0.5) = 2,088 ↩

-

Trustee Landscape Quantitative Research 2015 - Estimate based on Figure 3.2.3 Number of trustees by scheme size, page 14. ↩

-

The median hourly wage for a corporate manager or director is around £23 in the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings 2021, Table 2.5. This is uplifted by 27% for overheads from the archived Green Book. ↩

-

Calculation: (1,044 + 2,088) x 3.2 x 8 x £29 + (2,088) x 1 x 8 x £29 = £2,810,000 Figure rounded to nearest 10,000 ↩

-

Protecting Defined Benefit Pension Schemes (White Paper- March 2018) page 57 ↩

-

5,220 x 8 x 3.2 x £29 = £3,870,000 Figures rounded to nearest 10,000 ↩

-

(8 x 1 x £29 x 4,176) + (8 x 3.2 x £29 x 1,044) = £1,740,000 Figures rounded to nearest 10,000 ↩

-

Aon Global Pension Risk Survey 2017- UK survey findings page 6. ↩

-

Defined benefit trust-based pension schemes research summary report - page 24. Small: 12-99 Members, Mid-sized: 100-999 Members and Large: 1000+ Members ↩

-

The Purple Book 2021 - page 12 ↩

-

Source: DWP estimates derived from ONS Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (GB) ↩

-

Used the average number of trustees (3.2). ↩