Accessibility action plan consultation (HTML version)

Updated 25 July 2018

Ministerial Foreword

My ambition is to ensure that people with physical and hidden disabilities have the same access to transport and opportunities to travel as everyone else. This consultation seeks to understand what more needs to be done to improve transport accessibility and is my first major action as Accessibility Minister.

This Government is committed to improving disabled people’s access to transport. As we set out in our 2017 manifesto, we believe that where you live, shop, go out, travel or park your car should not be determined by your disability.

Accessible transport can make the difference between feeling socially isolated and feeling socially included. It can influence the extent to which you feel lonely or depressed, or whether you feel physically and mentally well. It can also contribute to your ability to secure and maintain long-term employment.

Accessible transport is not only about having accessible buses and trains; for example, it is also about the support and understanding of drivers and transport staff operating and delivering these services.

In addition, accessible transport not only relates to the services provided through mass transit. It is also provided in your local community through the work of important organisations, such as local community transport groups, networks like Driving Mobility and local Mobility Centres.

Positive achievements have been made in the transport sector. Many thousands of buses and trains are now physically accessible to more people with disabilities; stations and airports routinely include features and facilities to meet disabled people’s needs; and the pedestrian environment in many areas is much less challenging for those with mobility or vision impairments.

However, there are a number of areas where barriers to disabled people’s access remain. This can be due to, for example, a lack of training or understanding by transport staff; a need for more engagement by local authorities with local organisations representing people with disabilities when developing street design projects; or for increased monitoring and enforcement of accessibility standards.

Over the last few years, I have met with people with disabilities and disability organisations to better understand the barriers to transport accessibility. It is clear to me that those barriers extend far beyond those relating to the need to improve physical access. They include providing services in a way that ensures everyone can have confidence in the transport system, and particularly so for people with autism, dementia or mental health conditions such as anxiety, depression or phobias.

Last year, the Department for Transport sponsored the first Mental Health Summit within the transport sector, to draw attention to the need to do more in this area and promote the work of pioneering transport operators. The Department is indebted to organisations such as the Mental Health Action Group and Anxiety UK for the evidence and guidance that they have provided on these issues and for helping us to drive change. I am committed to doing more to support work in this area.

This draft Action Plan sets out our proposed strategy to address the gaps in existing provision of transport services which serve as a barrier to people with disabilities. It will be delivered in close partnership with a wide range of public and private sector bodies, as well as the travelling public. The draft Action Plan includes:

- advocating for greater consistency in the way transport services and facilities are delivered

- ensuring that accessibility features currently required by regulations are consistently monitored and compliance is enforced

- reviewing and monitoring access to parking in line with the Government’s manifesto commitment to improve disabled access to parking

- improving the amount, reliability and available information on passenger facilities, particularly accessible toilets, at stations and on trains

- highlighting the need for better awareness training for transport staff of the requirements of people with visible and hidden disabilities or impairments, and promoting best practice disability training guidance

- identifying and taking steps to address the challenges facing people with disabilities when seeking spontaneous travel – it is important that disabled people are able to travel as freely and easily as everyone else

This draft Action Plan sets out some specific commitments for increasing transport accessibility, and seeks your views and ideas about what additional steps we could take to create a system which enables people with disabilities to independently use the transport network. We would welcome input from disabled and older people, those with mental health conditions, consumer groups, transport operators and staff, local authorities and transport regulators.

People with disabilities have the same right to travel independently as anyone else and I am committed to delivering a transport system that works for all.

Paul Maynard

Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Rail, Accessibility and HS2

DPTAC Chair Foreword

Foreword from the Chair of the Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee (DPTAC)

There is little doubt that the UK benefits from a very diverse transport system. But there are too many areas where disabled people are still excluded.

DPTAC’s vision is that disabled people should have the same access to transport as everybody else, to be able to go where everyone else goes and to do so easily, confidently and without extra cost.

Over the last three decades we have been actively challenging, questioning, encouraging and advising the Department and Ministers on how to achieve that vision. Over that time, we have seen significant improvements in access to all modes of transport.

This draft Accessibility Action Plan (AAP) represents part of an ongoing journey for the Department in its work to improve disabled peoples access to transport and the built environment in which it operates.

In a time of change, challenge and great uncertainty it is important that the Department keeps its focus firmly on the future and in particular understands how to ensure that people are confident about accessing transport. An ageing population, increasing passenger numbers on the railways, the development of large infrastructure projects such as Crossrail and the High Speed rail network, the devolution of bus services, innovations in technology, the increase in the use of mobility scooters, new entrants to the taxi and private hire vehicle market, and the planning and construction of built environments brings challenges and opportunities for us all.

Change and uncertainty also reinforce the need for clear actions and outcomes. This Action Plan is the motor that will continue to drive improved access. DPTAC has played a key role in the development of the Plan from its initial stages and now through this consultation stage. And we will continue to hold the Department to account after publication of the Plan.

We very much welcome this consultation and we encourage everyone who has an interest in using transport to feed in your comments. We particularly need the Department for Transport to hear from people who have experienced problems that have put you off travelling that are not tackled in this AAP, and from those who perceive particular modes of transport as inaccessible so don’t even consider using them.

This is your opportunity to advise, challenge, shape, inspire and influence the Plan and help to bring about change that improves access for disabled people.

Keith Richards

Chair of the Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee

How to respond to the consultation

The consultation period began on 24 August 2017 and will run until 22 November 2017. Please ensure that your response reaches us at the following email or postal address on or before the closing date.

If you would like further copies of this consultation document, it can be found at www.gov.uk/dft#consultations or you can contact the address below if you need alternative formats (e.g. Braille).

Please send consultation responses to:

Email: AAPConsultation@dft.gsi.gov.uk

Or:

Accessibility Action Plan Consultation

Department for Transport

Zone 2/14

Great Minster House

33 Horseferry Road

London

SW1P 4DR

When responding, please state whether you are responding as an individual or representing the views of an organisation. If responding on behalf of a larger organisation, please make it clear who the organisation represents and, where applicable, how the views of members were assembled. If you have any suggestions regarding other individuals or organisations who may wish to be involved in this process please contact us or forward the document to them.

A summary of responses, including the next steps, will be published following closure of this consultation.

Freedom of Information

Information provided in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be subject to publication or disclosure in accordance with the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) or the Environmental Information Regulations 2004.

If you want information that you provide to be treated as confidential, please be aware that under the FOIA, there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals, amongst other things, with obligations of confidence.

In view of this it would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information, we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on the Department.

The Department will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act (DPA) and in the majority of circumstances this will mean that your personal data will not be disclosed to third parties.

Consultation principles

The consultation is being conducted in line with the Government’s key consultation principles. Further information is available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/consultation-principles-guidance

If you have any comments about the consultation process please contact:

Consultation Co-ordinator

Department for Transport

Zone 1/29

Great Minster House

London SW1P 4DR

Email: consultation@dft.gsi.gov.uk

1. Introduction

‘Transport, by whatever means, presents one of the greatest challenges to disabled people’[footnote 1]

1.1 Disability affects 1 in 5 (13.3 million) people in the UK[footnote 2] and can include physical or sensory impairments, as well as less visible or ‘hidden’ disabilities such as autism, dementia, learning disabilities or anxiety.[footnote 3]

1.2 For many people a lack of mobility or confidence in using the transport system is a barrier to employment, education, health care, and to a social life. It also comes at a cost to the individual in terms of loss of independence. Furthermore, research by the Extra Costs Commission has shown that disabled people experience higher transport costs as a result of inaccessible public transport, leading to increased use of taxis and private hire vehicles.

1.3 A lack of mobility or confidence in the transport system also comes at a cost to the state (at national and local level) in terms of lost tax revenue and increased dependence on welfare and home care. In 2017, the unemployment rate for working age disabled people in the UK was 9.1%, whilst the unemployment rate for non-disabled working age people was 4.1%.[footnote 4] Research has shown that a 10% rise in the employment rate amongst disabled adults could contribute an extra £12 billion to the Exchequer by 2030.

1.4 As a government, we are committed to building a country that works for everyone and our ambition is to enable one million people with disabilities to take up employment over the next ten years, and to put parity of esteem between physical disabilities and hidden disabilities, such as mental health conditions.

1.5 Last year, the Department for Work and Pensions and the Department of Health published the Improving Lives – the Work, Health and Disability Green Paper. The Green Paper consultation closed on 17th February 2017 and received several thousand responses across all sectors. The Green Paper outlined the previous Government’s proposals for improving work and health outcomes for disabled people and people with long-term health conditions, and it is clear that accessible transport plays a part in achieving these goals. The Government continues to be committed to this agenda and will set out next steps in due course.

1.6 As a Government, we are committed to unlocking the barriers to employment for disabled people in order to close the unemployment gap and increase their spending power. The disposable income of households with a disabled person is estimated to be £249 billion (PDF, 92.1KB). Lack of access to transport and the built environment can result in shops and businesses missing out on this potential revenue and can mean that the choice and opportunity for disabled people is reduced.

Disability within an ageing population

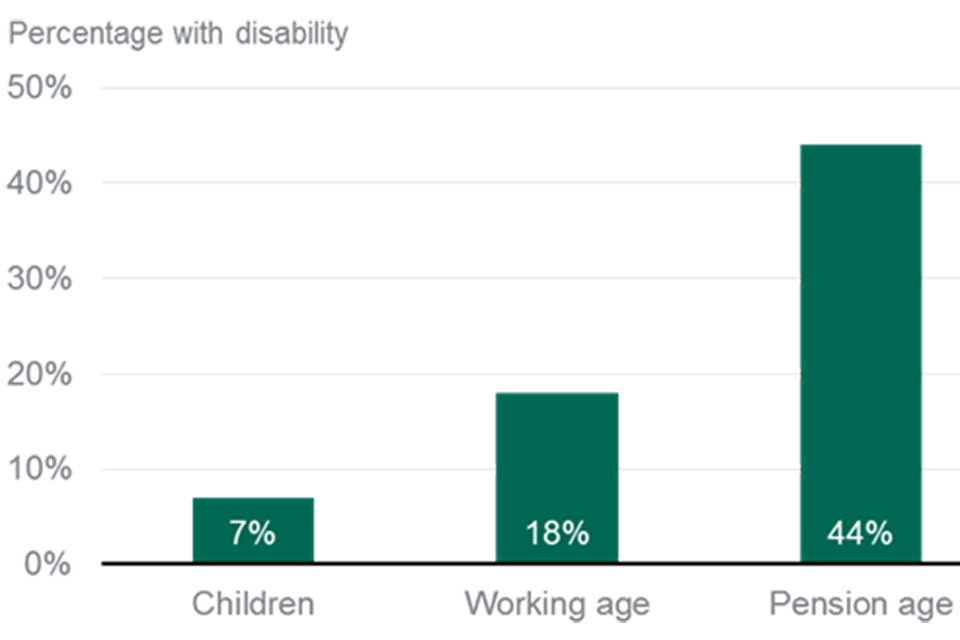

1.7 Our population is ageing and while many people retain high levels of fitness and mobility into old age, there is a connection between age and disability (see Figure 1). Disability within an ageing population can take many forms, but will often bring a combination of factors, including some loss of vision and hearing, stiffness of joints, and reduction in the ability to walk long distances.

Figure 1: Disability prevalence by age group, 2015/16 (Family Resources Survey 2015/16)

1.8 Short-term memory loss and more acute forms of dementia are more likely with increasing age. A person’s risk of developing dementia rises from one in 14 over the age of 65, to one in six over the age of 80.[footnote 5]

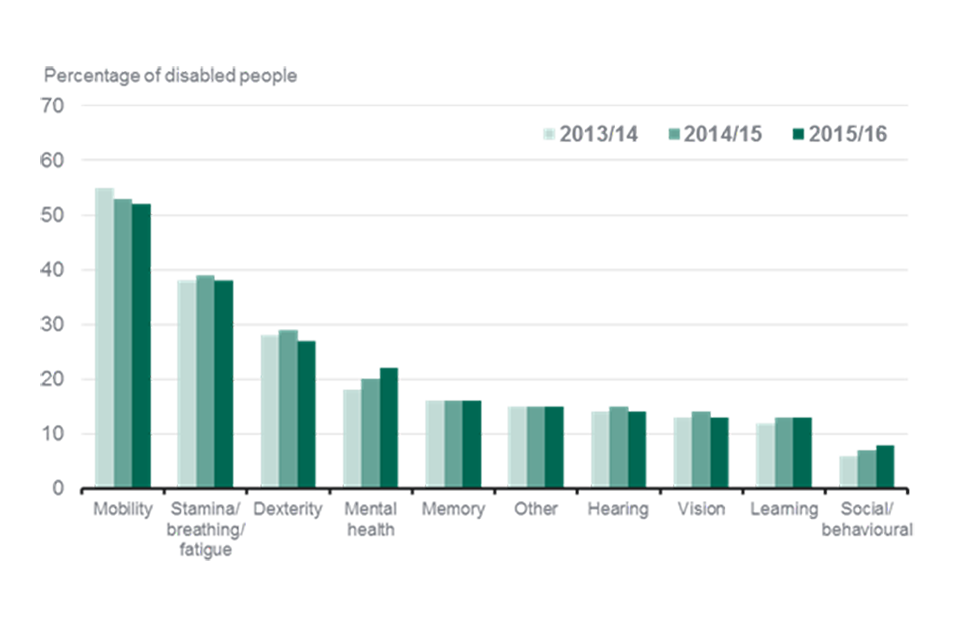

Figure 2: Impairments reported by disabled people, 2013/14 to 2015/16, United Kingdom (Family Resources Survey 2015/16)

1.9 In addition to the 13.3 million people with disabilities, many other people have mobility restrictions. These include pregnant women and people travelling with baby buggies, small children or luggage. Increasing levels of obesity also have an impact on people’s mobility and are another factor in planning for accessibility.

1.10 Transportation plays an important role in enabling people with disabilities, as well as those with mobility restrictions, to travel with ease. Our ambition is to deliver a transport system which is accessible to all whatever their background or characteristics[footnote 6]. This is in line with the social model of disability, which takes the view that it is the reaction of society to the impairment, for example through its provision of services and facilities, which can be the disabling factor, rather than the impairment itself[footnote 7].

1.11 The Transport for Everyone Action Plan: an action plan to improve accessibility for all, published in 2012, set out the vision of the Government at the time, for increasing transport accessibility for disabled people. It outlined how the Government would work to overcome the barriers that impede or prevent access to the transport system, which includes changing negative attitudes towards disabled and older people.

1.12 Since the 2012 Action Plan, thousands of buses and trains are now physically accessible to many more disabled people; stations and airports routinely include features and facilities to meet disabled people’s needs, and the pedestrian environment in many areas is much less challenging for those with mobility or vision impairments than it was.

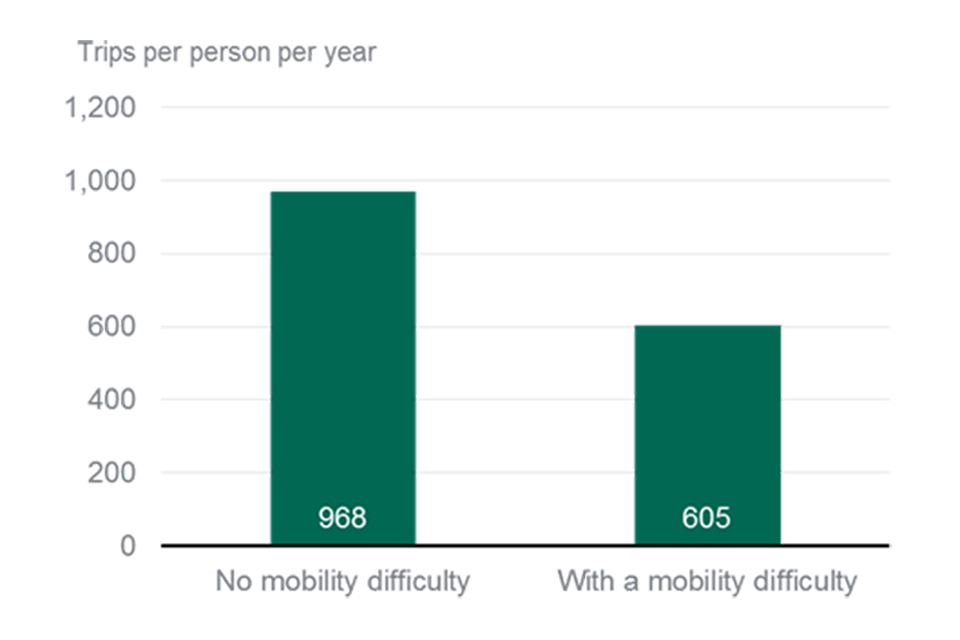

1.13 However, there remains a gap between the ease of accessing the transport system for disabled people compared to non-disabled people. This is demonstrated by the difference between the numbers of trips made by disabled people compared to non-disabled people, shown in Figure 3, where those with mobility difficulties only make 62% of trips compared to those without. This could be for a range of reasons including physical access difficulties, or anxiety about the attitudes of transport staff or passengers.

Figure 3: Trips per person per year by mobility difficulty[footnote 8], 2015 (National Travel Survey 2015)

1.14 This draft Accessibility Action Plan seeks to address the gaps in existing provision, and outlines how we intend to build on the progress made to date.

1.15 Our goal is to deliver a transport system that works for everyone, both those with disabilities and the non-disabled. We want to ensure that accessibility is addressed at the initial design and planning stages of transport programmes, including major infrastructure projects such as Crossrail and HS2.

1.16 Our proposals are based on consultations with disabled people and disability organisations, as well as on the findings and recommendations of the House of Lords Select Committee report on the Equality Act 2010 (PDF, 2.1MB) and input from the Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee (DPTAC), the Department’s advisers on accessibility policy.

1.17 Whilst this document contains specific questions for consultation, we would welcome your views on all of the proposals contained within it.

2. Scope

2.1 Responsibility for transport policy and delivery has been devolved to the administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to varying degrees. Notable reserved areas are cross border rail services, rail infrastructure investment in Wales, and aviation. Policy on equal opportunities, including accessibility, remains a reserved power.

2.2 The scope of this paper is restricted to those areas for which the DfT has direct responsibility in England and for those transport matters on which powers have been reserved at UK level.

2.3 The Equality Act 2010 applies in England, Scotland and Wales, but not in Northern Ireland, where the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 is still the key legal document in dealing with discrimination in the transport field.

2.4 It is also important to note that while the Equality Act 2010 transport requirements have not been devolved, the power to make statutory duties to deliver the public sector equality duty has, and the duties imposed on public authorities in England, Wales and Scotland can vary.

3. The progress so far

3.1 There has been significant progress in tackling physical and behavioural barriers to mobility over the past twenty years. A number of separate regulations[footnote 9] have established accessibility requirements across bus, rail and taxi vehicles.

3.2 Since their introduction in 2000, the Public Service Vehicle Accessibility Regulations (PSVAR) have resulted in a significant improvement in the accessibility of local transport for disabled people.

3.3 By April 2016, 94% of buses had received a certificate indicating that they met the PSVAR requirements, with a further 3% being of a low floor design, removing some of the barriers to bus usage that disabled people face. We expect the compliance figures to continue rising as the deadline for coaches approaches in 2020.

3.4 In addition, in 2001, the statutory concessionary fare scheme established free bus travel for older and disabled people across England. Since the scheme was introduced, the number of bus passes issued to disabled people has continued to rise, and in 2015/16 there had been 912,000 bus passes issued, an increase of 20% since 2010/11.

3.5 In the rail sector, 75% of rail vehicles operating on mainline services are compliant with accessibility standards, and all must be compliant by the 1 January 2020 deadline, as set out in the 2010 Rail Vehicle Accessibility Regulations (RVAR).

3.6 In addition, since 2014 over £160m of funding has been allocated to upgrade railway stations under the Access for All programme. This funding delivers accessible routes at stations by installing lifts or ramps, as well as features to help other disabilities, including tactile paving, signage or customer information systems. So far 25 stations have been delivered with this funding, with more than 40 others in various stages of construction or development. This builds on the 150 accessible routes at stations which have been delivered by the programme since its launch in 2006.

3.7 As of 2015, over 58% of taxis in England were accessible. This included all 22,500 London taxis, which are wheelchair accessible under Transport for London’s ‘Conditions for Fitness’ licensing policy.

3.8 Taxi and private hire vehicle (PHV) drivers must comply with specific requirements preventing passengers who use assistance dogs or wheelchairs from being refused carriage or charged extra for their journey. The provisions relating to passengers in wheelchairs came into force on the 6th April 2017 for drivers of vehicles designated as wheelchair accessible by the respective local licensing authority.

3.9 The Department also seeks to promote independent mobility for disabled and older people through its funding of the 13 Mobility Centres[footnote 10] across England. Over the past three years the Department has committed over £10m of funding for Mobility Centres, which has resulted in a 30% increase in the number of driving assessments undertaken by the centres.

4. Consistency in accessing transport services

4.1 One of the key barriers to accessibility identified by many disabled people is a lack of consistency in the way that services and facilities are delivered. This can apply across a wide range of areas, from the look and availability of a concessionary bus pass, to the way that signage is organised at a station or airport. In part this is due to regional and local variances in interpretation of standards and guidelines, sometimes stemming from the desire to have a clear identity for an individual local authority or operator.

4.2 The impact on some disabled people can, however, be significant. For those with visual impairments, not being able to confidently find the facilities they need is a problem. For people on the autism spectrum or with mental ill health, finding differences – for example, between the hours at which concessions are available from one local authority to the next – can be unsettling and may trigger a loss of confidence.

Accessible streets

4.3 Streets and roads make up around three quarters of all public space. Their appearance, and the way in which they function, therefore have significant impact on people’s lives. Well-designed, accessible streets encourage people to linger and spend time in them, which can also provide economic benefits; for example, for local retail.

4.4 In recent years there has been a significant change in attitudes to street design and management. The focus is increasingly on creating streets that function as places to visit and spend time in. The UK has a good level of basic provision of features such as dropped kerbs, tactile paving, and tactile and audible signals at traffic lights. Unlike many other countries, at signal controlled crossings the green pedestrian signal is protected so that people know they can cross with safety. This is not to say that more cannot be done, and we continue to promote the provision of accessibility infrastructure through our advice and guidance.

4.5 Wide-ranging guidance on street design is provided to practitioners in many of the documents we produce, all of which include references to the need for inclusive design. The key documents in this area are Manual for Streets and Manual for Streets 2, published in 2007 and 2010 respectively.

4.6 The guidance changed the approach to the design and provision of residential and other streets, and has an excellent standing among practitioners seeking to provide well-designed streets. Both documents promote inclusive design as a key part of improving the public realm. Although the technical guidance within both Manuals is still current, we are aware that the planning aspects may need updating in the light of changes to national planning policy guidance. We are considering how to update both documents.

4.7 Inclusive Mobility is a key piece of guidance, which enables local authorities to deliver accessible public realm environments. Whilst the guidance is recognised by some local authorities, we are keen to ensure that it is used consistently by all local authorities. We also recognise that it is in need of an update, particularly to cover the much greater knowledge and understanding now available of the needs of those with hidden disabilities, including autism, dementia and mental health conditions.

Tactile paving

4.8 Tactile paving surfaces are essential to guide and warn pedestrians, who are blind or partially sighted, of road crossings, platform edges and other potential hazards. The Department’s Guidance on the Use of Tactile Paving Surfaces was based on extensive research and has proved effective over many years. However, application and interpretation of the guidance by local authorities varies widely, meaning that some of the consistency can be lost, leading to less effective provision.

4.9 Although adhering to the Guidance on the Use of Tactile Paving Surfaces is not a statutory requirement, not doing so may leave an authority open to legal action. In 2012 the London Borough of Newham was found to have acted unlawfully by adopting a different local policy to the national guidance without adequately justifying why this was necessary[footnote 11] .

4.10 We will commission new research to ensure that the guidance fully reflects modern standards and changes in pedestrian environments, and provides greater emphasis on the importance of consistent application.

- Action 1: We will commission a research project to scope the updating of the ‘Inclusive Mobility’ guidance by the end of summer 2017. As part of this project we will also examine updating our guidance on the use of tactile paving surfaces. We will then consider the recommendations and determine a way forward.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Shared space

4.11 One approach to street design that has become more common in recent years is that of ‘shared space’. The aim of this is to encourage road users to share the full width of the highway, using a range of design features to achieve this. It is a spectrum, with many different types of scheme falling within it. Shared space has become synonymous in some places with the concept of a ‘level surface’ – the situation in which kerbs between footway and carriageway are removed. This is not a requirement of shared space and is generally only appropriate to consider in places with very low traffic volumes and speeds.

4.12 We understand that navigation can be a problem for visually impaired people in shared space streets. Our guidance published in Local Transport Note 1/11: Shared Space, already stresses the importance of engaging with groups representing disabled people during the development of any shared space scheme. It also makes clear the need for authorities to ensure their designs are inclusive and reminds them of their duties under the Equality Act 2010.

4.13 The 2010 Act includes a requirement that local organisations representing disabled people must be consulted at the earliest planning stage. There is plenty of advice available on running effective consultation and engagement processes, and we encourage authorities to make use of these resources. One example is the Chartered Institution of Highways and Transportation’s (CIHT) guidance on public involvement in street schemes.

4.14 We consider that the guidance provided in the Local Transport Note is still fit for purpose, but may not have always been properly applied; perhaps because of conflicting local authority objectives or a lack of skills, leading to schemes in which accessibility has not been adequately considered.

4.15 We are working with the CIHT, one of the professional bodies representing the highway and traffic engineering community, on a review of shared space and other street design projects. The aim is to provide clarity on how such schemes should be designed and developed. CIHT are involving a range of groups in the work, including DPTAC, and the Equalities and Human Rights Commission (EHRC).

4.16 The review by CIHT is intended to set out some key design principles for designers, and to reinforce to designers that improving inclusivity is not just one of many objectives for a scheme, but must be embedded within the process. All public realm schemes have a range of objectives to fulfil, but unlike others, inclusivity has a statutory regime behind it and authorities must consider the Public Sector Equality Duty when designing any public realm improvements, not just shared space.

4.17 The review is also likely to make recommendations for further work in this area. We will consider the need to revise guidance in the light of those recommendations.

4.18 Street design takes in a wide range of design approaches and, as discussed above, we believe a revised ‘Inclusive Mobility’ guidance will also be key to helping embed accessibility into all street environments, not just those labelled ‘shared space’.

- Action 2: We will continue our involvement with CIHT on their work on shared space. After we receive their report by the end of 2017, we will consider the recommendations and announce how we will take them forward.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Cycling Infrastructure

4.19 Our Cycling and Walking Investment Strategy was published on 21 April 2017 and sets out an inclusive approach to increasing the levels of walking and cycling . Alongside the Strategy, we have published guidance on developing Local Cycling and Walking Infrastructure Plans to help local authorities take a more strategic approach to improving conditions for cycling and walking. This guidance recognises that the design and implementation of good cycling and walking infrastructure should consider the needs of all users, and encourages local authorities to consult with disabled people, as well as other groups, when developing their plans and schemes.

4.20 The revised Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions 2016 included many new cycling and walking measures to help make cycling more accessible for all. New measures include designs for advanced stop lines and cycle early-start signals, which are of particular benefit to those needing additional time or distance to advance from traffic. To reflect these changes, we will refresh our guidance in Local Transport Note 2/08: Cycle Infrastructure Design, to ensure that local authorities can continue to design good, safe schemes that work for everyone in accordance with legislation.

4.21 We will also work closely with Highways England to maximise the benefits for disabled people of its new Cycling Strategy. This was published in 2016 and has led to an updating of Highways England’s design standards, enabling the strategic road network to be cycle-proofed and also enabling enhanced accessibility for a variety of users, including disabled people.

- Action 3: We will refresh our guidance in Local Transport Note 2/08: Cycle Infrastructure Design to ensure that local authorities can continue to design good, safe and inclusive schemes that work for everyone in accordance with legislation.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Audible and Visual announcements on buses

4.22 For people with visual impairments and hearing loss, as well as for those with learning disabilities, cognitive impairments, autism or mental health conditions, accessible information is a vital aid to independent travel.

4.23 The Government is committed to securing improvements in the provision of accessible information on board bus services. The Bus Services Act 2017 creates powers to implement an accessible information requirement, mandating the provision on-board local bus services throughout Great Britain of audible and visible information identifying the respective route and each upcoming stop.

- Action 4: We will work with disabled people, the bus industry and the devolved administrations, on the Regulations and guidance which will implement the Accessible Information Requirement on local bus services throughout Great Britain, helping disabled passengers to travel by bus with confidence.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Physical Accessibility of buses

4.24 The Public Service Vehicles Accessibility Regulations 2000 (PSVAR) set out access requirements for new buses and coaches, and imposed deadlines by which all vehicles in service had to comply. PSVAR has applied to single-deck vehicles designed to carry over twenty-two passengers on local and scheduled routes since 1st January 2016, and double-deck buses since 1st January 2017. Coaches have until 1st January 2020 to meet the requirements.

4.25 PSVAR requires vehicles subject to it to incorporate a wheelchair space and boarding facilities suitable for the standard ‘reference wheelchair’[footnote 12], as well as priority seating, colour-contrasting hand-holds and a range of other features, to enable disabled passengers to board, alight and travel in comfort and safety.

4.26 We are aware that in a number of areas, particularly in some rural areas, high floor, non-accessible coaches, which are not required to be PSVAR-compliant until 2020, are being used to provide local bus services subsidised by the local authority. This means that some passengers are not being provided with accessible services.

4.27 When tendering local bus services, local authorities should be conscious of their Public Sector Equality Duty, and ensure that their decisions are consistent with it. Non-compliance with the public sector equality duty may be used to challenge policies or decisions made by a public authority through a complaint or legal action.

Bus concessionary fares

4.28 There are some differences in eligibility and the nature of bus concessions for disabled people between England and the devolved administrations in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, both in terms of who is eligible and when the concession is available.

4.29 In some circumstances the lack of cross-border acceptance may mean that concessionary pass holders are unable to reach their nearest town for free where it is located across a border. In many cases however, Travel Concession Authorities (TCAs) have put in place discretionary arrangements to resolve this issue.

4.30 In England, local authorities may also interpret the statutory eligibility criteria differently, which can mean that people who qualify in one area may not in another. In particular, people with hidden disabilities may find that their entitlement is not consistently recognised when applying in different areas of the country.

4.31 To inform future policy making it would be useful to understand your perspective on how well the national bus concession in England supports disabled people. It is important to note, however, that there are no current plans to amend primary legislation.

Future Policy Development

Consultation Question 1

How well do you feel the national bus concession in England succeeds in supporting the local transport needs of disabled people, and how might it be improved? Please be as specific as possible in your response.

Increasing availability and accessibility of taxis and private hire vehicles

4.32 While wheelchair accessible taxis are now widely available in major towns and cities, in many smaller towns and rural areas there are few, if any, taxis and private hire vehicles (PHVs) that can accommodate a passenger who needs to remain in their wheelchair. Taxi and PHV licensing authorities already have powers to determine the make-up of their fleets, but there is no consistent approach to doing so.

4.33 In addition, disability groups have reported that newer generations of ‘accessible’ taxis and PHVs are not consistently designed to meet the needs of passengers; for example, those who are not wheelchair users, but who need assistance with boarding and alighting from handholds, lower steps or swivel seats.

Image 1: Example of wheelchair accessible taxi

4.34 The Extra Costs Commission recommended that the Government exercise standard setting powers. We are currently in the process of updating our best practice guidance for taxi and PHV licensing authorities, and we will consult on this by the end of 2017. This guidance will include recommendations on ensuring that an inclusive service is supported.

4.35 In particular, it will encourage authorities to use their existing powers to require prospective drivers to complete disability awareness and equality training prior to being licensed, and will emphasise the importance of taking robust action against drivers who have discriminated against disabled customers, including where an assistance dog or wheelchair user has been refused.

4.36 Authorities already have the powers they need to ensure that taxis and PHVs within their jurisdiction are accessible to those who need them, and the revised guidance aims to help them to make more effective use of these powers.

4.37 We believe that licensing authorities should collaborate to develop a shared understanding about the needs of disabled passengers, helping them to take a more consistent approach in ensuring that the overall service provided by taxis and PHVs in their areas meet the needs of everyone who wishes to use them.

- Action 5: We will review and consult on best practice guidance for taxi and PHV licensing authorities, which will include strengthened recommendations on supporting accessible services, including on the action that licensing authorities should take in response to reports of assistance dog refusal. This guidance is expected to be published in 2017.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

- Action 6: We will seek to increase the number of accessible vehicles through appropriate recommendations to taxi and PHV licensing authorities in our draft revised best practice guidance.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Ensuring a consistent taxi service

4.38 As well as ensuring the physical accessibility of vehicles used in taxi and PHV transport, we also need to ensure the inclusivity of the services they provide. We were told by disabled people of instances where taxi or PHV drivers failed to stop when hailed, charged extra for providing assistance or carrying a wheelchair, or refused the carriage of an assistance dog.

4.39 Under the Equality Act 2010, taxi and PHV drivers, in common with other service providers, must make reasonable adjustments to enable disabled people to access their services. The Equality Act also makes it a criminal offence to charge extra for carrying an assistance dog or wheelchair user, or to refuse them carriage. The provision with respect to passengers in wheelchairs applies only to drivers of taxis and PHVs designated as wheelchair accessible by the respective local licensing authority, and also includes a requirement to provide appropriate assistance.

4.40 Informed by the recommendations of the Extra Costs Commission in 2015 and following extensive stakeholder engagement, the provisions preventing such discrimination against passengers in wheelchairs, Sections 165 and 167 of the Equality Act 2010, came into force on the 6th April 2017.

4.41 The continued illegal discrimination by some taxi and PHV drivers against disabled passengers is unacceptable, and we encourage local authorities to take appropriate action against those responsible when instances are reported. In particular, we would encourage local authorities to provide clearer information on the making of complaints about continued discrimination by some taxi and PHV drivers, and encourage them to take effective action against those responsible when instances are reported.

4.42 The Extra Costs Commission also recommended that information about how to make complaints be readily available, and Scope is currently working with ‘Which?’ to empower taxi and PHV users, by advising them how to complain effectively and seek redress when they receive an inadequate level of service.

4.43 We also agree with the findings of the Extra Costs Commission and Law Commission reports (PDF, 1.7MB) that consistent and effective disability awareness and equality training plays an important role in giving drivers the knowledge and skills to assist disabled passengers and to avoid discriminating against them.

4.44 Some operators have demonstrated commitment to making their services more accessible. Uber, for instance, worked with Scope and other organisations representing disabled people, to review the challenges faced by disabled passengers, addressing instances of inadequate service, overcharging and availability of wheelchair accessible vehicles. This work resulted in the launch of two new travel options, enabling passengers to request a driver who has completed disability awareness training and to book a wheelchair accessible PHV. The operator has ensured that such services cost no more than its cheapest standard option.

4.45 Examples such as this demonstrate that taxi and PHV providers can make changes to address the barriers faced by people with disabilities. We are keen to see more taxi and PHV providers take steps to build awareness of the needs of disabled passengers and to ensure that they receive an accessible service on an equal basis to other passengers.

Reviewing the Blue Badge scheme

4.46 The Blue Badge scheme is a lifeline for disabled people who rely on being able to park close to their destination. Issues about eligibility for people with non-physical disabilities have been raised.

4.47 Our view is that the regulations do not preclude the issue of badges to people with non-physical disabilities. Whatever the disability, a person may be eligible if their condition causes very considerable difficulty in walking. Ultimately, the decision as to whether a person’s mobility problems constitute ‘difficulty walking’, and the degree of that difficulty, is a matter for local authorities to assess on a case-by-case basis.

4.48 However, we agree with DPTAC that improvements could be made so that eligibility criteria are more consistently applied across the country and that more effective enforcement would strengthen the scheme for those who rely on it.

4.49 We want to ensure that the rules and guidance are clear for individuals and local authorities and that there is greater consistency in the assessment of such applicants by local authorities.

- Action 7: We will review, in co-operation with DPTAC and others, Blue Badge eligibility for people with non-physical disabilities. This will include considering the link to disability benefits.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Railway station improvements

4.50 Many of our stations were built in the Victorian era when the needs of disabled people were not considered. Some stations have listed status, which can place restrictions on the extent and manner in which improvements can be made.

4.51 We are, however, committed to improving station access to make our existing stations more accessible, and the industry is required to meet current EU and UK accessibility standards whenever station infrastructure is installed, replaced or renewed. Failure to do this can lead to enforcement action by the Office of Rail and Road (ORR).

4.52 Many stations are also improved as part of major enhancement programmes. For example, Birmingham New Street and Reading stations are now accessible for the first time, and the Crossrail programme will provide step free access at an additional 40 stations.

4.53 We have published Design Standards for Accessible Railway Stations which set out the standards Network Rail and train operating companies (TOCs) must comply with.

4.54 For stations which are not undergoing other upgrade work, the Department’s Access for All programme has played a major part in improving accessibility. By 2019, the programme will have invested over £500m in improving access to railway stations.

4.55 Over 150 stations have been given step free, accessible routes to and between every platform, and around 1,500 have received smaller scale improvements such as tactile paving or accessible toilets. To build on this success, the Access for All programme was extended in 2014, with an additional £160m to fund 68 more accessible routes. By 2019, 42 of these will have been completed, with the remainder in development.

4.56 There still remain stations that are inaccessible to people with disabilities – and indeed to those travelling with baby buggies or heavy luggage. The Department will continue to seek additional funding to extend the Access for All programme further.

4.57 The Department also funds train operators, through their franchise agreements, to undertake accessibility improvements at their stations through a Minor Works Budget. This Minor Works Budget, worth in the region of £300,000 per year, must be used to fund improvements such as better signage, adapted waiting rooms, ticket halls and toilets, or tactile paving and handrails.

4.58 A study carried out for the Department for Transport in 2015 found that 33% of wheelchair users, 19% of hearing impaired passengers and 15% of mobility impaired passengers, made extra journeys following station improvements.

Access for All improvements at Godalming and Acocks Green railway stations

- Action 8: We will continue to roll-out station access improvements for which funding has been allocated, and deliver the Access for All programme in full, building on the significant progress that the programme has already made. We will continue to seek to extend the Access for All programme further in the future.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Guidance on access to air travel

4.59 The provision of information is vital in ensuring that all travellers can confidently undertake air travel and enjoy the benefits it brings. For disabled people and/or people with reduced mobility, information regarding the accessibility of aviation, including the legislation and available services, is key to making travel plans.

4.60 The Department published its Access to Air Travel for Disabled People – Code of Practice 2003 (PDF, 309KB), which provided advice on all aspects of access to air travel. This aimed to promote a better understanding of accessibility needs, and to set out the legal requirements and recommendations into best practice for all those involved in providing services related to air travel, including airports, airlines, aircraft designers, travel agents, tour operators, ground handling companies and retailers.

4.61 The Code of Practice was subsequently updated in 2008 to coincide with changes in legislation in this area, namely the introduction of EU Regulation (EC) 1107/2006, regarding the rights of disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility when travelling by air. The updated Code was equally focused on the obligations for the service providers in the aviation sector.

4.62 The Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), as the industry regulator, works closely with UK airports and airlines to maintain high standards of service for disabled passengers and those with reduced mobility. The CAA has published further industry-specific guidance, including guidance for airports on providing assistance to passengers with hidden disabilities.

4.63 The CAA also actively monitors service providers’ performance in this area, and has introduced, in co-operation with the industry, a regulatory performance framework, containing a range of measures against which UK airports are required to set, measure and report on their performance.

4.64 The results are collected by the CAA and published in an annual report, which increases transparency to passengers and enables the CAA to hold airports to account if the assistance provided does not meet the expected standards.

4.65 The first report was published in August 2016 (PDF, 539KB) and collected data on thirty airports, ranking them in accordance with a number of criteria, including levels of customer satisfaction in the provision of assistance service, monthly ‘waiting time’ performance targets for assistance, and consultation and involvement of local charities and disability organisations in the development of the assistance service at the airports, as well as other criteria.

4.66 Ten airports[footnote 13] of varying size were ranked as providing a very good service. These airports also consulted widely with local charities and disability organisations to develop their assistance services. Gatwick, Birmingham and Glasgow International airports have also been consistently praised by the CAA for the quality of their assistance service. This report demonstrates that it is possible to overcome the logistical challenges of large airport operations to provide a high quality assistance service that meets the needs of passengers with disabilities.

4.67 The CAA intends to publish an updated report on airport performance by the end of 2017.

4.68 In addition to the CAA, several other organisations have published extensive guidance aimed at the travelling public, in order to inform them of their rights, and encourage disabled persons and those with reduced mobility to travel by air. These organisations include the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) (PDF, 375KB) and the Consumer Council for Northern Ireland (CCNI).

4.69 We are interested in hearing your views on whether you think that guidance, regarding disabled persons or persons with reduced mobility when travelling by air, could be improved.

4.70 While this consultation focuses on the provision of information, there will be further opportunities to explore the experiences of disabled passengers and those with reduced mobility when travelling by air in the UK.

4.71 We are planning to develop a new Aviation Strategy, which will be an ambitious programme of work exploring opportunities for Government to make a positive difference to the passenger experience.

4.72 The work will consist of a series of consultations exploring a wide variety of issues, including the consumer experience of aviation, and the travel experience of disabled passengers and those with reduced mobility more specifically. A Call for Evidence, setting out the Government’s plans and objectives for this work, was published for consultation on 21st July 2017. More information on the timings of the various Green Papers which will each concentrate on specific issues will be published in due course.

Future Policy Development

Consultation Question 2

As a passenger or an organisation representing disabled people, what is your experience of information and guidance setting out the rights of disabled persons or those with reduced mobility when travelling by air?

We have listed some questions below which you may find helpful in responding. However, the list is not exhaustive and you should not feel restricted to the themes below.

Is there enough information available regarding your rights as a disabled or less mobile passenger when travelling by air?

Is the existing information and guidance clear and understandable, or is it too technical? For example, could the wording be improved? If so, how?

Are there any particular areas where you feel there is too little information available? Is the existing information focused on certain areas while leaving gaps in others, or is there a balance?

Is the existing information easy to access/find? If not, what could be done to make the information easier to access?

In your opinion, which organisation (e.g. the Government, a consumer rights advocacy, a disability organisation, etc.) would be most appropriate to provide information and guidance in this area? Why?

Consultation Question 3:

As an industry representative or a service provider in the aviation sector, what is your experience of guidance regarding your obligations when providing services to disabled persons or those with reduced mobility when travelling by air?

We have listed some questions below which you may find helpful in responding. However, the list is not exhaustive and you should not feel restricted to the themes below.

Based on the existing guidance, do you know what is expected of you when providing services to disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility?

Is the guidance detailed enough? Is there enough information available?

Is the existing information easy to access/find? If not, what could be done to make the information easier to access?

What could be added to the guidance to make it easier for you to provide services to disabled persons and persons with reduced mobility?

Are there any specific areas that you feel are not adequately covered in the existing guidance? Are there any areas that you feel the existing guidance is placing too much emphasis on?

Accessibility on passenger ships and at ports

4.73 The EU Maritime Passenger Rights Regulation (EU 1177/ 2010), which is directly applicable within the UK, ensures that all passengers, including those with disabilities or reduced mobility, receive comparable assistance at the start, during and at the end of their journey. The Maritime & Coastguard Agency (MCA) acts as the National Enforcement Body (NEB) for the UK, working with carriers and operators to ensure compliance and taking enforcement action when required.

4.74 Passengers with disabilities or reduced mobility should be accepted for carriage and not refused transport, except for reasons which are justified on the grounds of safety. Carriers are obliged to co-operate with disability organisations and engage with them in the training of their personnel, and in organising assistance to disabled persons and those with reduced mobility. Carriers are also obliged to take into account international standards and recommendations on design set by the International Maritime Organisation and the EU[footnote 14], as well as MCA guidance.

4.75 Carriers and terminal operators must also provide passengers with disabilities or reduced mobility, assistance free of charge in ports, including embarkation and disembarkation, and on board ships.

4.76 The existing legislation requires terminal operators and ports to establish or have in place – where it is appropriate – non-discriminatory access. There is no requirement for ports, terminal operators or ships to retrofit. However, they are required to take account of the needs of passengers with disabilities and those with reduced mobility when carrying out major refurbishment or design of new infrastructure.

4.77 We would encourage all bodies responsible for designing new ports and terminals or major refurbishments to give full consideration to the accessibility needs of passengers with disabilities and reduced mobility, and to design facilities that can be used by all passengers.

Future Policy Development

Consultation Question 4

As a passenger or an organisation representing disabled people, what are your experiences with maritime passenger services when travelling by sea, in particular are there any issues where you feel more could be done to improve accessibility for passengers with disabilities or with reduced mobility?

We have summarised the actions contained in the Consistency in Accessing Transport Services section, and would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the actions proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

-

Action 1: We will commission a research project to scope the updating of the ‘Inclusive Mobility’ guidance by the end of summer 2017. As part of this project we will also examine updating our guidance on the use of tactile paving surfaces. We will then consider the recommendations and determine a way forward.

-

Action 2: We will continue our involvement with CIHT on their work on shared space. After we receive their report by the end of 2017, we will consider the recommendations and announce how we will take them forward.

-

Action 3: We will refresh our guidance in Local Transport Note 2/08: Cycle Infrastructure Design to ensure that local authorities can continue to design good, safe and inclusive schemes that work for everyone in accordance with legislation.

-

Action 4: We will work with disabled people, the bus industry and the devolved administrations, on the Regulations and guidance which will implement the Accessible Information Requirement on local bus services throughout Great Britain, helping disabled passengers to travel by bus with confidence.

-

Action 5: We will review and consult on best practice guidance for taxi and PHV licensing authorities, which will include strengthened recommendations on supporting accessible services, including on the action that licensing authorities should take in response to reports of assistance dog refusal. This guidance is expected to be published in 2017.

-

Action 6: We will seek to increase the number of accessible vehicles through appropriate recommendations to taxi and PHV licensing authorities in our draft revised best practice guidance.

-

Action 7: We will review, in co-operation with DPTAC and others, Blue Badge eligibility for people with non-physical disabilities. This will include considering the link to disability benefits.

-

Action 8: We will continue to roll-out station access improvements for which funding has been allocated, and deliver the Access for All programme in full, building on the significant progress that the programme has already made. We will continue to seek to extend the Access for All programme further in the future.

5. Monitoring the Impact of Regulatory Compliance

5.1 Accessibility standards for trains have been mandatory for new trains since 1999 and the deadline for compliance for pre-1999 trains is 1st January 2020.

5.2 Standards include the requirement for the installation of accessible features, such as audio-visual passenger information systems, palm operable doors with audio-visual warning functions, handholds, priority seating, accessible toilets, wheelchair spaces, provision of manual boarding ramps, colour-contrasting floors and external door markings.

5.3 During our pre-consultation engagement with disabled people and organisations representing disabled people, there were concerns raised around accessibility features, which are covered by legislation, not being consistently monitored and enforced.

Improving accessibility and passenger experience on board trains

We are committed to improving the travelling experience of people with disabilities using facilities on our trains and stations. We have summarised all the relevant actions from across this consultation here:

-

Action 9: Subject to the finalisation of the Statement of Funds Available (in October this year), Government will allocate funding to provide additional accessible toilet facilities at stations as part of the next rail funding period (from 2019 onwards).

-

Action 10: From October 2017, DfT will fund a pilot to explore opportunities to improve train tanking facilities and increase the availability of train toilets. Building on the learning from this and industry-led research in this area, we will consider how best to allocate further investment, beginning with upcoming franchising opportunities.

-

Action 11: ORR will publish the results of its large programme of research, looking in depth at accessibility and assistance, in 2017. It is expected that the results will provide a snapshot of industry performance and include industry level recommendations to take forward (further information on the research is provided in Section 7 on Spontaneous Travel).

-

Action 12: DfT is exploring with the Rail Delivery Group (RDG) the ability for train operators to provide ‘alternative journey options’ if the journey becomes unsuitable – for example, if the only accessible toilet on a train goes out of use unexpectedly.

-

Action 13: We are exploring with RDG the possibility of placing dynamic notifications on the Stations Made Easy web pages, of the availability of accessibility features on trains.

-

Action 14: We are also exploring with RDG how notifications of such incidents can be provided to passengers as early as possible.

-

Action 15: We are working with the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) to launch an innovation competition in September 2017, which will find solutions to reducing the cost of accessibility improvements at stations, including the availability of accessible toilets. This competition will also focus on making improvements aimed at those with hidden disabilities.

-

Action 16: We are also investing in a new rail innovation accelerator which will look at how the availability of facilities can be improved.

Progress so far

5.4 Currently, 75% of all passenger rail vehicles in Great Britain (a total of over 12,300 vehicles) have been built, or fully refurbished, to modern access standards. This is an increase of 25% since the 2012 Accessibility Action Plan.

5.5 The remaining vehicles must be refurbished by 2020, or replaced by new trains, for example, under the Thameslink or Intercity Express programmes, or as part of the new franchises for the North (e.g. new, compliant trains will replace older vehicles as part of the delivery of the Northern and TransPennine Express franchises).

5.6 For trains built before 1999 which are still in service, the deadline for compliance is 1 January 2020. The Department is working closely with the owners and operators of these trains to ensure that the necessary work is scheduled in time to meet this deadline. In some cases, older trains, such as Pacers in the north of England, will be replaced by modern trains by 2019.

5.7 The images overleaf are of (before and after) the Persons of Reduced Mobility Technical Specifications for Interoperability (PRM-TSI) refurbishment work on trains (Class 465/0 and Class 465/1 Electric Multiple Units) operated by SouthEastern and owned by Eversholt Rail (UK) Limited.

Image 3: Before and after example of refurbished accessible toilet facilities

Image 4: Before and after example of refurbished doors with colour-contrasting floors and accessible handrails

Image 5: Before and after example of refurbished accessible wheelchair seating facilities

5.8 Reaching the 100% accessibility target in 2020 will represent more than 20 years of investment in upgrades in rolling stock since standards were first introduced.

Continuously improving the passenger experience

5.9 We are committed to ensuring that the ongoing benefits of investment in rolling stock upgrades are realised. As part of our engagement with disabled people and disability groups, concerns were raised around the reliability of accessibility features once installed. For example, accessible toilets are sometimes unavailable because they are out of service due to technical faults or other problems.

5.10 In 2017, we completed a review of requirements on train operating companies (TOCs) to report on the reliability of the accessibility features installed in their rolling stock, and we are now developing further reporting criteria for train operating companies to improve the quality of data reported.

5.11 The Department is also undertaking a piece of work to evaluate the impact of train accessibility features on rail travel for disabled passengers. The aim of this review is to clearly understand whether investment has been made in the right places on rail vehicles to enable confident use of the network.

5.12 The findings of the study will provide a benchmark to indicate the value to passengers of these changes and will provide evidence of whether there is more which could be done to adapt the layout and features inside trains to improve accessibility further.

5.13 Alongside this, operators of franchised passenger services regularly report to the Department on aspects of their performance; for example, punctuality, reliability or train cancellations.

5.14 We will explore options to include requirements to report on the reliability of accessibility features and link this to work ORR is carrying out to assess the quality of provision of service under Disabled People’s Protection Policy (DPPP) commitments. We believe that including such requirements will help to drive continuous improvement in rail vehicle accessibility.

Action 17: We will commission research, which will be published by 2018, to measure the impact for passengers of work to improve rail vehicle accessibility since the introduction of Rail Vehicle Accessibility Regulations (RVAR) and the introduction of the Persons of Reduced Mobility Technical Specification for Interoperability (PRM TSI).

Action 18: By the end of 2017, we will publish performance data on accessible features on trains, and details of any remedial action necessary to improve both the quality of the data reported and any areas of poor performance.

Action 19: We will also share the performance data reported to us with ORR, to inform any action they take to ensure operators are meeting their legal requirements to comply with accessible rail vehicle standards. We would welcome your feedback.

Do you agree or disagree with the actions proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Future Policy Development

Consultation Question 5

When you use a train, what has been your experience of accessibility equipment, such as the passenger announcements (either audible or visual), accessible toilets or manual boarding ramps, or other accessibility features)?

For example, do you find this equipment reliable, and if not, how could train operators better ensure reliability or assist you?

Ongoing accessibility of buses and coaches

5.15 Since their introduction in 2000, the Public Service Vehicles Accessibility Regulations (PSVAR) have prompted a significant improvement in the accessibility of local transport for many disabled people.

5.16 By April 2016, 94% of buses[footnote 15] had received a certificate, indicating that they met the PSVAR requirements, with a further 3% being of a low floor design, removing some of the barriers to bus usage that disabled people face. Coaches have until 1st January 2020 to meet the requirements.

5.17 Disabled passengers now rightly expect a high standard of accessibility from bus services, yet still sometimes find that vital equipment, such as the boarding ramps used by wheelchair users, are not working when they come to board.

5.18 The Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) enforces the Public Service Vehicles Accessibility Regulations (PSVAR) on behalf of the Department for Transport. Enforcement is undertaken as part of routine vehicle compliance-checking, and in 2015 over 7,000 public service vehicles were inspected. Of these, only 47 were found to be non-compliant with PSVAR, generally because of malfunctioning rather than missing components.

5.19 The role of the DVSA, in undertaking compliance checks and enforcing PSVAR, remains key to ensuring that standards of accessibility are maintained and that operators take the upkeep of required facilities just as seriously as they did their initial compliance with the Regulations.

5.20 The Department for Transport will continue to work with the DVSA to review their existing remit, and to ensure that their enforcement activity appropriately targets those operators least likely to comply and those aspects of PSVAR which are of greatest importance to disabled travellers.

Image 6: Impact of PSVAR on bus design

Action 20: We will support the DVSA in its activities to communicate with operators on, and incentivise prompt compliance with, PSVAR, and to take decisive action where this does not happen. We will expect the DVSA to report annually on the action taken.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Refusal of assistance dogs in taxis

5.21 A 2015 Guide Dogs for the Blind Association (Guide Dogs) survey ‘Guide Dogs (2015) Access All Areas’ found that 44% of assistance dog owners who had been refused access to a service in the preceding year had experienced such discrimination when attempting to use a taxi or PHV. Such refusals are not only unacceptable and illegal, but they seriously inhibit disabled people’s confidence and ability to live independent lives.

Action 21: We will review, with Government partners and stakeholders, the reasons why some taxi and PHV drivers refuse to transport assistance dogs, and identify key actions for local or central government to improve compliance with drivers’ legal duties.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

Monitoring abuse of disabled parking spaces

5.22 The Government’s manifesto has committed to improving disabled access to parking. This will include monitoring the abuse of disabled parking spaces. Being unable to park close enough to shops or other destinations because non-badge holders have parked where they should not, is not simply an inconvenience for people with impaired mobility; it often denies them the opportunity to make a visit or attend an appointment.

5.23 In some cases the abuse of accessible parking spaces is not in relation to drivers parking without a badge, though this can be the case; but it can also be drivers displaying a badge which does not belong to them and that they are not entitled to use.

5.24 For on-street parking, the Blue Badge system applies, and the level of attention given by local authorities to monitoring the use of Blue Badge parking spaces by non-Blue Badge holders varies widely across the country.

Action 22: We have begun publishing enforcement newsletters aimed at local authorities (i.e. all Blue Badge teams and parking teams) to promote enforcement success stories and good practice, in order to help encourage better enforcement of disabled parking spaces. We will also continue our regional engagement workshops with local authorities and will work with DPTAC on both initiatives.

We would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the action proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

We have summarised the actions contained in the Monitoring the Impact of Regulatory Compliance section above and would welcome your feedback. Do you agree or disagree with the actions proposed? Are there any other areas which require further attention? Please explain why.

-

Action 9: Subject to the finalisation of the Statement of Funds Available (in October this year), Government will allocate funding to provide additional accessible toilet facilities at stations as part of the next rail funding period (from 2019 onwards).

-

Action 10: From October 2017, DfT will fund a pilot to explore opportunities to improve train tanking facilities and increase the availability of train toilets. Building on the learning from this and industry-led research in this area, we will consider how best to allocate further investment, beginning with upcoming franchising opportunities.

-

Action 11: ORR will publish the results of its large programme of research, looking in depth at accessibility and assistance, in 2017. It is expected that the results will provide a snapshot of industry performance and include industry level recommendations to take forward (further information on the research is provided in Section 7 on Spontaneous Travel).

-

Action 12: DfT is exploring with the Rail Delivery Group (RDG) the ability for train operators to provide ‘alternative journey options’ if the journey becomes unsuitable – for example, if the only accessible toilet on a train goes out of use unexpectedly.

-

Action 13: We are exploring with RDG the possibility of placing dynamic notifications on the Stations Made Easy web pages, of the accessibility features on trains.

-

Action 14: We are also exploring with RDG how notifications of such incidents can be provided to passengers as early as possible.

-

Action 15: We are working with the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) to launch an innovation competition in September 2017, which will find solutions to reducing the cost of accessibility improvements at stations, including the availability of accessible toilets. This competition will also focus on making improvements aimed at those with hidden disabilities.

-

Action 16: We are also investing in a new rail innovation accelerator which will look at how the availability of facilities can be improved.

-

Action 17: We will commission research, which will be published by 2018, to measure the impact for passengers of work to improve rail vehicle accessibility since the introduction of Rail Vehicle Accessibility Regulations (RVAR) and the introduction of the Persons of Reduced Mobility Technical Specification for Interoperability (PRM TSI).

-

Action 18: By the end of 2017, we will publish performance data on accessible features on trains, and details of any remedial action necessary to improve both the quality of the data reported and any areas of poor performance.

-

Action 19: We will also share the performance data reported to us with ORR, to inform any action they take to ensure operators are meeting their legal requirements to comply with accessible rail vehicle standards.

-

Action 20: We will support the DVSA in its activities to communicate with operators on, and incentivise prompt compliance with, PSVAR, and to take decisive action where this does not happen. We will expect the DVSA to report annually on the action taken.

-

Action 21: We will review, with Government partners and stakeholders, the reasons why some taxi and PHV drivers refuse to transport assistance dogs, and identify key actions for local or central government to improve compliance with drivers’ legal duties.

-

Action 22: We have begun publishing enforcement newsletters aimed at local authorities (i.e. all Blue Badge teams and parking teams) to promote enforcement success stories and best practice, in order to help encourage better enforcement of disabled parking spaces. We will also continue our regional engagement workshops with local authorities and will work with DPTAC on both initiatives.

6. Training and education

6.1 However good the underlying legal requirements for accessibility to vehicles, and to the pedestrian and built environments, unless those responsible for designing, implementing and delivering accessibility understand what is needed in the provision of assistance, and why, our ambitions for greater accessibility will not materialise.

6.2 Positive steps were taken by transport operators as part of the 2012 London Olympics and Paralympics, to train staff in providing information and assistance to disabled people. We are also aware of positive examples of training and awareness-raising across other parts of the transport sector.

6.3 In the rail sector, every train and station operating company must, as a condition of its licence, have a Disabled People’s Protection Policy (DPPP), approved by ORR. As part of this, train operators provide disability awareness training to staff.

6.4 As part of its role of monitoring compliance with DPPPs, ORR collects and publishes data from licence holders on the numbers of staff undertaking disability awareness training and the kinds of training provided. ORR’s 2016 report included positive examples, such as Virgin Trains West Coast’s work with a dementia charity to pilot dementia-friendly training for staff.

6.5 In the bus industry, disability awareness training is available, and completed by the majority of drivers, as part of their periodic Certificate of Professional Competence (CPC). Completion of such training will become mandatory on the 1st March 2018 in Great Britain. We will support the bus industry and training accreditors in their implementation of this requirement, and have already worked with bus operators and disabled people to develop best practice guidance, which will help to provide drivers with the knowledge and skills to assist any disabled passenger.

6.6 There are some examples of good practice across the private hire sector. Uber provides selected drivers with disability awareness training, and customers can request a driver who has completed the course. Birmingham licensing authority has introduced mandatory training for its prospective PHV drivers.