FPC leverage ratio consultation

Updated 2 February 2015

1. Introduction

Reform of the UK’s financial sector regulation and a strong and stable financial system are key elements of the government’s long-term economic plan. This government has undertaken a wide-ranging programme of fundamental reforms to the UK’s financial regulation as set out in the Financial Services Act 2012. The government has learnt from the mistakes of the past and established focused regulators with clear objectives.

The government’s reforms are based on four years of analysis, consultation and legislation to reform the UK’s financial sector. They represent the biggest ever overhaul of the UK’s banking system. In 2010, the Chancellor asked Sir John Vickers to lead the Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) which made recommendations for fundamental reform of banking, including the creation of ring-fenced banks to protect the essential functions of retail banking. In 2012, in response to the LIBOR scandal, the Chancellor recommended to Parliament the creation of the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS). The Banking Reform Act 2013 implemented the key recommendations of the ICB and the PCBS. The work to raise the standards of conduct in the financial system is continued by the Fair and Effective Markets Review that the Chancellor announced in June 2014.

1.1 The Financial Policy Committee

The Financial Policy Committee (FPC), established on 1 April 2013 by the Financial Services Act 2012, is a vital part of the government’s new system of financial regulation. The FPC is the UK’s macroprudential regulator: its objective is to protect and enhance the stability of the UK’s financial system by identifying, monitoring and addressing systemic risks. The FPC works with the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) to address risks to the system as a whole, while the PRA and FCA have responsibility for microprudential and conduct regulation of individual firms, respectively.

1.2 The FPC Leverage review

On 26 November 2013, the Chancellor requested that the FPC undertake a review of the leverage ratio and its role in the regulatory framework. The Chancellor noted the strong progress that had been made internationally on bank capital standards and the ongoing work by the FPC to finalise the medium term capital framework for UK banks. In light of these developments, the Chancellor judged that it was an appropriate time for the FPC to consider all outstanding issues relating to the leverage ratio, including whether and when the FPC needed any additional powers of direction over the leverage ratio, and whether and how leverage requirements should be scaled up for ring-fenced banks and in other circumstances where risk-based capital ratios are raised. Subject to the FPC presenting a detailed and evidence based recommendation, the Chancellor said he would expect to be able to submit the Committee’s proposals in this Parliament for approval.

On 31 October 2014, following almost a year of work and extensive consultation with stakeholders, the FPC published its response, the Review of the leverage ratio. The Review recommended that the FPC given new powers of direction over the leverage ratio framework for the UK banking sector. Specifically, the Review recommended that the FPC should have a power of direction to set:

- minimum leverage ratio requirement to be set at 3%

- supplementary leverage ratio buffer rate to be set as a proportion of the systemic risk-weighted capital buffers using a scaling factor of 35%

- countercyclical leverage ratio buffer rate to be set as a proportion of the countercyclical capital buffer rates using a scaling factor of 35%

1.3 The government’s response

The Review makes a strong, evidence-based argument for the implementation of a leverage ratio framework as a complement to the existing risk-based capital requirements. As confirmed in the Chancellor’s letter to the Governor of 31 October 2014, the government accepts the recommendations and intends to take forward legislation in this Parliament to grant the FPC new powers of direction over the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA). To this end, the government is consulting on draft legislation granting the FPC powers of direction over:

- a minimum leverage ratio that will apply to all PRA-regulated banks, building societies and investment firms; this will apply to G-SIBs and other major domestic UK banks and building societies as soon as practicable and to all other firms in scope from 2018

- a supplementary leverage ratio buffer for G-SIBs, ring-fenced banks and large building societies; leverage buffers for G-SIBs will be phased in in parallel with the G-SIB risk-weighted systemic buffers as from 2016, and leverage buffers for ring-fenced banks and large building societies will apply from 2019

- a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer that will apply to all institutions subject to the minimum; this will come into force to the same timescale as the minimum requirement.

1.4 Aims of the consultation

This consultation seeks to gather the opinions of stakeholders and other interested parties concerning the leverage ratio framework that the Financial Policy Committee (FPC) has recommended it be granted new powers of direction over. This consultation also seeks comments on the draft legislation granting the FPC these powers.

The FPC indicated in its final report that, were it to be granted the powers of direction it has requested, the leverage ratio framework would be implemented as follows:

- minimum leverage ratio requirement would be set at 3%;

- supplementary leverage ratio buffer rate would be set as a proportion of the systemic risk-weighted capital buffer rate using a scaling factor of 35%; and

- countercyclical leverage ratio buffer rate would be set as a proportion of the countercyclical capital buffer rate using a scaling factor of 35%.

This consultation does not seek views on the FPC’s proposed calibration of the leverage ratio framework described above, as this is a matter for the FPC.

Structure of this consultation

This consultation is set out as follows:

- Chapter 2 provides an overview of the FPC and its existing powers

- Chapter 3 explores the rationale for leverage ratio tools

- Chapter 4 sets out the government’s proposals

- Chapter 5 contains a copy of the draft statutory instrument

- Chapter 6 sets outs a summary of the consultation questions that government is seeking views on

1.5 Implementation

Once the government has considered the responses to this consultation, it will publish a summary of the responses received alongside laying a draft statutory instrument in Parliament. These documents will be accompanied by an impact assessment.

Section 9L of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) provides the vires for HM Treasury making macroprudential Orders prescribing macroprudential measures for the purposes of section 9H of the same Act. Orders made under section 9L are subject to the affirmative procedure and must be approved by both Houses of Parliament before they come into force.

2. The Financial Policy Committee

2.1 Macroprudential policy and the Financial Policy Committee

There has been increasing recognition that traditional microprudential policies allowed financial vulnerabilities to grow unchecked, contributing to the global financial crisis. A key lesson of the crisis has been that the safety and soundness of individual institutions focused primarily on financial resources and idiosyncratic risks (i.e. microprudential regulation) is not on its own sufficient to maintain financial stability.

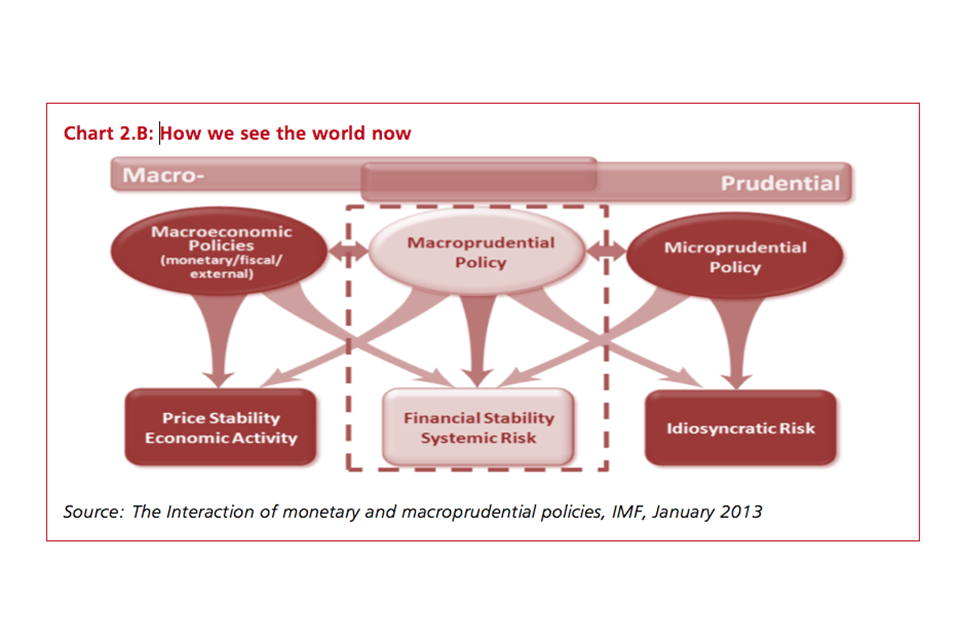

As a result, authorities across the world have sought a more comprehensive approach to financial stability by introducing a macroprudential policy regime to complement both microprudential policy and macroeconomic policy (see Chart 2.A and Chart 2.B).

Macroprudential policy can deploy traditional regulatory tools (relying on the regulators for implementation and enforcement). However, it adapts the use of these tools to counteract growing vulnerabilities in the financial system by assessing two key dimensions of risk:

- cross-sectional dimension of risk: the contributions of individual institutions to systemic risk. This is related to connections between institutions, the distribution of risk with the sector and structural factors such as information asymmetries. These can be monitored by tracking balance sheet information such as capital ratios

- time-series dimension of risk: the evolution of systemic risk through time. This is related to over-exuberance in the upturn of the financial cycle being exacerbated by systematic under-pricing of risk, leading to asset bubbles, stretched balance sheets and other unsustainable expansionary trends. This can be monitored by tracking a wide set of macroeconomic variables such as the ratio of credit to GDP

Chart 2.A: How we saw the world before the financial crisis

Chart

Source: The Interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies, IMF, January 2013

Chart 2.B: How we see the world now

Chart

Source: The Interaction of monetary and macroprudential policies, IMF, January 2013

The UK has embraced macroprudential policy and is not alone in moving to incorporate macroprudential policy into its regulation of the financial system. The European Systemic Risk Board in the European Union and the Financial Stability Oversight Council in the United States are just two prominent examples of this international shift.

The UK government created the independent Financial Policy Committee (FPC) within the Bank of England with statutory responsibility for maintaining financial stability[footnote 1].

The FPC’s primary objective is to identify, monitor, and take action to remove or reduce systemic risks with a view to protecting and enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system. However, given there are interactions between macroprudential policy and economic activity (see Chart 2.B), the government provided the FPC with a secondary objective to support the economic policy of the government.

The FPC has eleven members, of which ten are voting members. Its members are the Governor of the Bank of England, three of the Deputy Governors, the Chief Executive of the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), the Bank’s Executive Director for Financial Stability Strategy and Risk, four external members appointed by the Chancellor, and a non-voting HM Treasury member.

The FPC meets on a quarterly basis, and it publishes a Financial Stability Report (FSR) every 6 months. The aim of the FSR is to set out the FPC’s assessment of the outlook for the stability and resilience of the financial sector.

2.2 Powers of the FPC

The FPC has two main sets of powers at its disposal. These are its powers of recommendation and powers of direction. Reflecting its macroprudential role, the FPC is not responsible for making decisions in respect of individual firms: it can only make recommendations or issue directions that relate to all regulated institutions or to all institutions that meet a specified description. The role of the FPC is therefore a crucial complement to, but distinct from, those of the firm level regulators – the PRA and the FCA.

2.3 Powers of recommendation

The FPC has a power to make recommendations to the regulators — the PRA and the FCA — about the exercise of their functions, such as to adjust the rules facing banks and other regulated financial institutions. The FPC can issue these recommendations on a ‘comply or explain’ basis. Should the regulators decide not to implement these ‘comply or explain’ recommendations, they would be required to explain their reasons for not doing so[footnote 2].

The FPC is also able to make recommendations to HM Treasury, including on additional macroprudential tools that the Committee considers that it may need, and on the ‘regulatory perimeter’ – that is, both the boundary between regulated and non-regulated activities within the UK financial system, and the boundaries between the remits of different regulators within the regulated sector[footnote 3].

The FPC also has a broader power to make recommendations to any other persons. For example, this power allows the FPC to make recommendations directly to the industry or to independent bodies such as the Financial Reporting Council.

2.4 Powers of direction

The second set of powers is to give directions to the regulators (i.e. the PRA and FCA) to implement specific macroprudential tools.

The Capital Requirements Regulation and the Capital Requirements Directive 4 establish rules concerning the prudential supervision of banks and certain investment firms. These rules contain a formalised framework for macroprudential measures where they operate directly on risk weights, levels of own funds, large exposures liquidity or micro-prudential buffers. Moreover, the framework established rules for setting the countercyclical capital buffer.

Currently, the FPC has the power to apply two macroprudential tools that operate within the EU framework for macroprudential measures:

- it is responsible for policy decisions on the countercyclical capital buffer (CCB): this requires firms to build up capital and release it when the FPC judges it to be the best approach to head off threats to financial stability. The FPC’s decisions on the UK CCB rate apply to firms’ UK exposures

- it has a power of direction over sectoral capital requirements (SCRs): this allows the FPC temporarily to increase banks’ capital requirements on exposures to specific sectors. The FPC is able to adjust SCRs for exposures to three broad sectors: residential property, including mortgages; commercial property; and, other parts of the financial sector

These tools apply to all banks, building societies, and large investment firms incorporated in the UK (smaller investment firms which are not authorised by the PRA have been carved out from the scope of the FPC’s powers regarding SCRs by the government).

Use of the CCB and SCR tools can enhance the resilience of the financial system in two ways: first, directly by increasing the loss-absorbing capacity of the financial system increasing the resilience of the system to periods of stress; and second, via indirect effects on the amount of financial services supplied by the financial system through the cycle (either through the distribution or overall level of these services), reducing the severity of periods of instability.

Although the measures contained in this consultation paper will concern the prudential supervision of banks and investment firms, they will not operate within the current formalised EU framework for macroprudential measures. Therefore it will be important for the FPC to be cognisant of developments in the EU relating to macroprudential policy, where these impact on the measures contained in this consultation paper

2.5 Accountability

There are a number of ways by which the FPC is held accountable for the exercise of its powers.

FPC policy decisions, including any new directions and/or recommendations, are communicated to those to whom the action falls (e.g. the PRA or FCA). The policy decision is also communicated to the public, either via a short statement in the first and third quarters of the year or via the Financial Stability Report (FSR) in the second and fourth quarters.

For each of its powers of direction, the FPC must prepare, publish and maintain a written statement of the general policy that it proposes to follow in relation to the exercise of its power including maintaining core indicators. Furthermore, when making recommendations or giving directions to the regulators the FPC must provide an estimate of the benefits and costs, unless it is not practicable to do so.

A formal Record of the FPC’s policy meetings is published around a fortnight after the relevant meeting. It must specify any decisions taken at the meeting and must set out, in relation to each decision, a summary of the FPC’s deliberations.

FPC members also appear regularly before Members of Parliament at Treasury Select Committee (TSC) hearings, where they are required to explain their assessment of risks and policy actions. The TSC has also held confirmation hearings for members.

Furthermore, the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) requires that statutory instruments that set out the FPC’s tools in secondary legislation must go through an affirmative legislative procedure. Therefore, both Houses of Parliament must expressly approve any draft macroprudential tools orders before they can become law[footnote 4].

3. Leverage and financial stability

3.1 An introduction to the leverage ratio

Bank capital represents the residual claim on banks’ assets after other creditors, such as deposit holders, have been repaid. UK banks, building societies and investment firms are subject to capital adequacy requirements, the aim of which is to ensure firms’ hold sufficient capital to absorb losses, including those arising from deteriorating economic conditions.

The Basel III framework defines an internationally agreed capital standard for internationally active banks in order to establish a level playing field and minimise the risk of cross-border capital arbitrage. The UK government strongly supports the Basel III framework, which has been implemented in the EU through the Capital Requirements Regulation/Capital Requirements Directive IV (CRR/CRDIV).

Broadly, Basel III incorporates two types of capital adequacy ratios:

- risk-weighted standards, which are based on a granular assessment of the risks of the assets that a firm holds, with more capital required to be held against higher risk assets. Firms either use standardised risk weights set by the regulator based on historical industry wide data, or they use their own internal models to calculate risk weights (or a combination of these two approaches)

- a leverage standard, which also seeks to ensure that firms have adequate capital to absorb losses, but which treats all exposures equally regardless of their estimated risk

The Basel III leverage ratio as set out in the standards for leverage ratio disclosure published by the Basel Committee in January 2014[footnote 5] is defined as the capital measure (the numerator) divided by the exposure measure (the denominator), with this ratio expressed as a percentage. Unlike risk-weighted assets (RWA) capital ratios, all exposures are weighted equally in the calculation of the leverage ratio.

The capital measure is defined in Basel III as Tier 1 capital, which can be further be broken down into Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) and Additional Tier 1 (AT1). CET1 is the sum of common equity (e.g. ordinary shares), retained earnings and other reserves held by the firm. AT1 consists of instruments that resemble debt instruments until a trigger point is reached (usually a specified risk-weighted capital ratio for the issuing entity), at which point they convert into ordinary shares or are written down. This conversion automatically improves the capital ratio of the issuing firm.

The Basel III definition of the exposure measure is the sum of:

- on-balance sheet exposures (e.g. the loans made by the firm)

- derivative exposures (both exposure from underlying assets and counterparty credit risk)

- securities financing transaction exposures (e.g. repos, reverse repos, security lending and borrowing, and margin lending transactions)

- off-balance sheet items (e.g. commitments -including liquidity facilities- direct credit substitutes, acceptances, standby letters of credit and trade letters of credit)

As all on-balance sheet exposures are equally weighted, this ensures that firms are required to hold a minimum amount of capital relative to their exposures regardless of their activities. Also exposures cannot be offset by risk mitigation (e.g. any collateral held against an exposure does not reduce the exposure measure for leverage ratio calculation). This prevents the exposure of a firm deteriorating rapidly if its collateral devalues.

Leverage ratios are usually expressed as a percentage, with lower percentages indicating greater leverage, and regulatory requirements are expressed as minimum requirements, e.g. a 3% leverage ratio requirement requires a firms to have a leverage ratio greater than 3%. These percentages are sometimes expressed as multiples, for example: a firm that has a leverage ratio of 3% is 33 times leveraged (i.e. its exposures are 33 times larger than its Tier 1 capital) and a 4% leverage ratio equates to 25 times leveraged.

3.2 The role of leverage ratios in macroprudential regulation

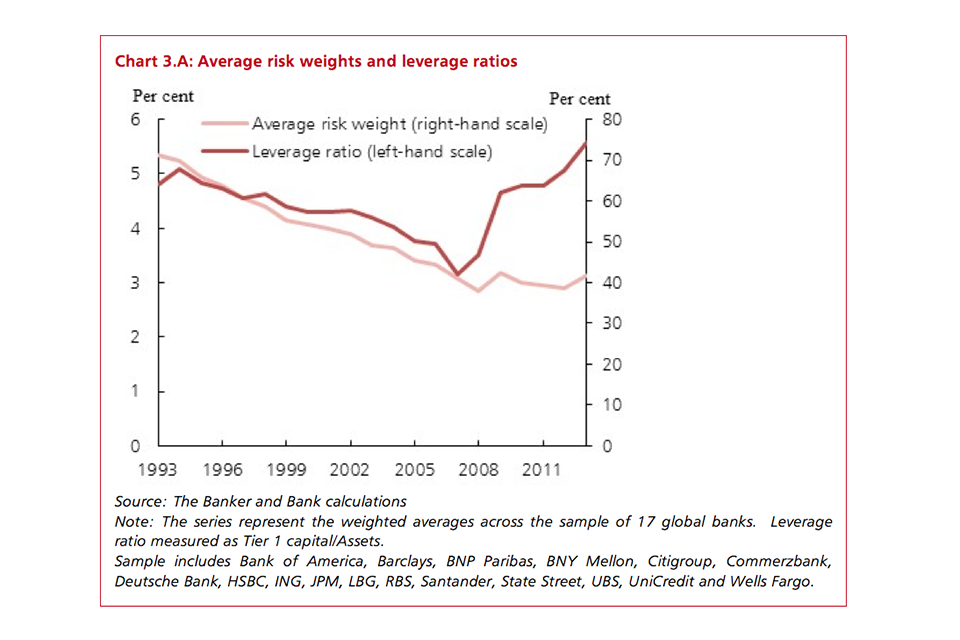

The recent financial crisis revealed serious weaknesses in the existing framework of internationally agreed standards of capital adequacy. Banks in most jurisdictions were only required to meet risk-weighted capital requirements and were not subject to leverage requirements. In the lead up to the crisis, some banks’ balance sheets expanded significantly while average risk weights declined (see chart 3.A below). Banks funded increases in their lending through greater amounts of relatively cheaper debt rather than equity.

Chart 3.A: Average risk weights and leverage ratios

Chart showing average risk weights and leverage ratios

Source: The Banker and Bank calculations

Note: The series represent the weighted averages across the sample of 17 global banks. Leverage ratio measured as Tier 1 capital/Assets. Sample includes Bank of America, Barclays, BNP Paribas, BNY Mellon, Citigroup, Commerzbank, Deutsche Bank, HSBC, ING, JPM, LBG, RBS, Santander, State Street, UBS, UniCredit and Wells Fargo.

However, the riskiness of some assets turned out to be greater than initially thought. This meant that, as losses materialised, firms did not have enough capital to absorb them. Moreover, the crisis revealed that some types of capital instruments that banks were holding were not sufficiently loss absorbing. As market confidence decreased, firms were left vulnerable because of increased roll-over risk of their short-term debt, and funding was severely curtailed. At the height of the crisis, this led to firms having to deleverage quickly, selling into a falling market. The losses on these assets depleted firms’ regulatory capital. Firms were forced to deleverage further due to market concerns that they were not adequately capitalised relative to the exposures they still held, resulting in a destabilising negative feedback loop.

A number of important changes to the regulatory framework have been made since the crisis. A selection of the most prominent are shown below.

- Basel III agreement introduced significantly higher minimum capital ratios, supplemented by a series of additional buffers

- quality of the capital required to meet these requirements was also significantly increased by the Basel III agreement

- Basel Committee is pursuing an ongoing programme of work to strengthen the risk-based capital framework

- an internationally agreed liquidity framework is being introduced for the first time, requiring banks to hold larger buffers of liquid assets to survive a shock to funding markets and incentivising them to rely on more stable funding sources

- there has been a concerted effort, both in the UK and internationally, to tackle the “too big to fail” problem[footnote 6], including by building the resilience of systemic firms and by making them more resolvable.

Moreover, the UK regulatory and supervisory framework includes a number of tools to complement, and address weaknesses in, the risk based regime, including supervisory reviews of banks’ models for calculating risk weight and a regime of annual stress tests to ensure that there is sufficient capital in place for extreme but plausible stresses

3.3 The strengths of a leverage ratio requirement

There is international agreement that the leverage ratio is a crucial complement to risk-based capital requirements and can play an important role in mitigating the risks described above. Firms’ leverage ratios were a useful indicator of failure during the last crisis, and the period immediately preceding the crisis was characterised by sharp increases in leverage. Firms with high leverage ratios have greater amounts of capital to absorb losses which materialise and have less reliance on debt financing. Those with low leverage ratios rely relatively more on debt to fund their lending, exposing them to the risks described above.

The leverage ratio restrains balance sheet growth, ensuring that firms preserve a minimum amount of capital to absorb losses regardless of the risk profile of their assets. The international standard proposed by the Basel Committee on Banking Standards (BCBS) is currently a minimum 3% leverage ratio. In other words, a bank would be able to increase its exposures only up to a maximum of 33 times relative to the amount of Tier 1 capital it holds. As exposures are not weighted by risk in the calculation of the leverage ratio, imposing leverage limits also provides additional protection against uncertainties and risks that are difficult to model. The additional protection provided by a leverage ratio can be particularly important during the upswing of the credit cycle, when, as the financial crisis showed, risk may be systemically underestimated by risk-based models and those who use them (including regulators).

The leverage ratio’s relative simplicity can also help improve market transparency and comparability, particularly as investors have become more sceptical about risk-weights. International work on the consistency of risk-weights has highlighted this. For example, although some variability is to be expected because of supervisory discretion and the way that firms model their risks, Basel’s review of the consistency of risk-weights applied in the trading book showed that there was considerable variability in risk-weights applied by different banks to the same hypothetical portfolio. Although work is ongoing to improve transparency and reduce variability of risk-weighted assets, it is still difficult for the market to compare how well-capitalised banks are using risk-based measures. The leverage ratio should help increase transparency and comparability of firms’ solvency.

3.4 The weaknesses of a leverage ratio requirement

However, despite the usefulness of the leverage ratio, the government agrees with the FPC that the leverage ratio should be seen as a useful complement to, rather than an alternative to, risk-based capital requirements, and that the value of a leverage ratio on its own should not be overstated. The evidence that leverage ratios are sometimes a better indicator of failure than risk-based capital ratios does not mean that leverage requirements are a cure-all for financial stability risks. It is unlikely that lower leverage alone would have prevented the last crisis, and had firms faced a leverage ratio requirement, they might have behaved differently.

Moreover, even where it is used as a complement to risk based capital requirements, the leverage ratio can create undesirable incentives for some firms or in relation to some types of assets. If a firm is bound by or is close to falling below the required leverage ratio, there would be an incentive to reallocate assets across the group at the solo or sub-consolidated level or to increase the riskiness of assets at both the solo and group level for the greater return on equity until the risk-based capital ratio starts to bite. As the recent IMF Global Financial Stability Report[footnote 7] notes:

New regulatory requirements may induce banks to retrench from some activities if they are unable to re-price. For example, when binding, the leverage ratio (LR) could make it uneconomical to hold or acquire lower risk assets.

Banks with low average risk weights will be relatively more constrained by leverage ratio requirements. Firms which are genuinely low risk will therefore face pressure either to increase capital or to change their business model in response to a binding leverage requirement. This could create substantial competitive disadvantages, especially for firms, such as mutuals, which are required by law to provide particular types of loans as the majority of their lending portfolios. Some firms also are restrained in the ways in which they can raise capital (for example, building societies cannot issue equity as they are owned by their members) and these firms are likely to be hit harder by higher capital requirements imposed by leverage ratio requirements. Moreover, the incentive to “risk-up” may have the undesired effect of increasing the risks that firms that previously used low-risk business models are exposed to.

The calibration of the leverage framework is crucial to mitigating these risks. The FPC concluded in its impact assessment that, based on its proposed calibration, the levels of additional capital implied by the leverage framework would have only a modest impact on individual firms and markets.

3.5 Recent developments

An international leverage ratio

In September 2009, the G20 announced its support for the introduction of an internationally consistent leverage ratio. The leverage ratio “would serve as a supplementary measure to the Basel risk-based framework, with a view to migrating to a Pillar 1 treatment based on appropriate review and calibration.”[footnote 8]

A proposed 3% minimum leverage ratio is one of the key elements of the Basel III agreement. In January 2014, the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS) agreed a final definition of the leverage ratio.[footnote 9] This is due to be disclosed by internationally active banks from 1 January 2015 to allow leverage ratios to be compared across jurisdictions. The BCBS will continue to monitor the implementation of the leverage ratio, and a final calibration of the leverage ratio is expected by 2017, following a review, with a view to migrating to a binding Pillar 1 minimum requirement from 1 January 2018.

A number of international jurisdictions – including Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States – either already impose leverage ratio requirements on firms or are intending to do so.

3.6 The EU’s CRDIV Regime

The EU does not currently have a requirement for credit institutions to meet a Pillar 1 leverage ratio. However, where there is concern about a firm’s leverage, supervisors have the ability to impose a Pillar 2 leverage ratio. This is applicable on a firm-by-firm basis.

EEA firms however must report their leverage ratio to regulators from 1 January 2014. Public disclosure is mandated from 2015. This must be at the group level as well as at the solo significant subsidiary or sub-consolidated level. Firms are able to disclose under the transitional definition of capital.

The European Banking Authority (EBA) is required to assess whether the leverage ratio is appropriate for EU credit institutions. One of the key questions it will consider is whether different business models should meet different leverage ratio minimum requirements or whether there should be a one-size-fits all approach regardless of the type of institution. Other issues such as whether the introduction of the leverage ratio results in movement of activity to shadow banking, the impact on lending to the economy and on institutions’ risk profiles will also be considered. The EBA must report to the European Commission by 31 October 2016. The Commission will then submit a report for the EU Council and Parliament- with a possible legislative proposal.

3.7 The European Systemic Risk Board

In April 2013, the ESRB stated that where time-varying risk-weighted capital requirements applied, a countercyclical leverage ratio could also apply to maintain its role as a backstop to the risk-weighted capital ratios.[footnote 10] The ESRB also noted that its use could be envisaged at the national level before potential adoption across the EU.

3.8 Recent developments in the UK

In September 2011, the Independent Commission on Banking (ICB) – established by the Chancellor in 2010 - recommended that a higher leverage ratio buffer requirement should apply to large ring-fenced banks.[footnote 11] The ICB argued that this would ensure that the leverage ratio retained its complementary role alongside the higher risk-based buffer requirements of 11.5% Tier 1 that the largest ring-fenced banks would have to meet (i.e. when the bank’s average risk-weight was below 35%, the leverage ratio would be the more constraining ratio). In response to the ICB’s recommendations, the government reiterated its support for a binding minimum leverage ratio, including for ringfenced banks, and committed to continuing to press for full implementation of the Basel III standard in the UK through European legislation. However, the government did not at that stage judge that the case had been made to diverge from international standards by imposing higher leverage requirements on large ring-fenced banks.[footnote 12]

In March 2012, the interim FPC recommended that HM Treasury should give it powers of direction over a “maximum ratio of total liabilities to capital and to vary it over time”. The FPC noted that “a leverage ratio limit would constrain financial institutions’ ability to increase the overall size of their exposures relative to their capacity to absorb losses. Key strengths of the leverage ratio were its simplicity, transparency and the fact that it does not depend on an assessment of the relative riskiness of assets. Importantly, by restricting overall balance sheet size, a leverage ratio might mitigate funding risks indirectly”[footnote 13]. In response to this recommendation, HM Treasury agreed to grant the FPC a countercyclical leverage ratio power from 2018, subject to a review in 2017 to assess progress on international standards[footnote 14].

In 2012, in response to the LIBOR scandal, the Chancellor recommended to Parliament the creation of the Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards (PCBS). The PCBS called for a leverage ratio to improve the capitalisation of the major UK banks.

On 26 November 2013 the Chancellor wrote to the Governor asking the FPC to undertake a review of the role of the leverage ratio within the capital framework. The Chancellor noted the strong progress that had been made internationally and the ongoing work by the FPC to finalise the medium term capital framework for UK banks. In light of these developments, the Chancellor judged that it was an appropriate time for the FPC to consider all outstanding issues relating to the leverage ratio, including whether and when the FPC needed any additional powers of direction over the leverage ratio, and whether and how leverage requirements should be scaled up for ring-fenced banks and in other circumstances where risk-based capital ratios are raised. Subject to the FPC presenting a detailed and evidence based recommendation, the Chancellor said he would expect to be able to submit the Committee’s proposals in this Parliament for approval.

3.9 Existing leverage ratio standards applying to UK banks

The FPC has issued two recommendations on the leverage ratio, with which the Financial Services Authority (FSA)[footnote 15] and the PRA have complied.

In 2011 and 2012, the interim FPC recommended that the FSA should encourage banks to disclose the Basel III transitional and end-point leverage ratios from 2013[footnote 16] - two years ahead of the internationally agreed timeline. The aim of this was to help increase market confidence in the capital adequacy of firms. The largest eight UK banking groups and building societies[footnote 17] have been disclosing their leverage ratios on a bi-annual basis.

At its meeting in March 2013, the interim FPC made a set of recommendations concerning the regulatory capital positions of the major UK banks and building societies[footnote 18]. This included a recommendation that the PRA ensure that these institutions had credible plans in place to meet the higher leverage requirements that would come into effect after full implementation of Basel III[footnote 19]. As part of its implementation of these recommendations, the PRA announced that it would expect these firms to meet a 3% Tier 1 leverage ratio[footnote 20]. All these firms are currently meeting a 3% leverage ratio[footnote 21].

4. The government’s proposals

4.1 Rationale for giving the FPC powers of direction over leverage

The FPC has a broad power of recommendation that allows it to make recommendations to the PRA and FCA (“the regulators”) and to the industry itself on matters relating to leverage or to other issues relevant to financial stability.

The FPC has recommended to HM Treasury that it should be given a power to issue directions to the PRA with regards to:

- a minimum leverage ratio requirement that would apply to all PRA-regulated banks, building societies and investment firms

- an additional leverage ratio buffer to be applied to systemically important firms that would supplement minimum requirements

- a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer that would be applicable to all firms subject to the minimum leverage ratio requirement

While the FPC has been able to use it powers of recommendation to date, the government believes that there are benefits to the FPC possessing a power of direction over leverage ratio requirements.

Firstly, powers of direction provide for greater certainty to the FPC as, unlike a recommendation, the regulator is compelled, within the scope of its powers, to comply with the direction[footnote 22]. Moreover, as the FPC notes, there may be circumstances where tensions arise between the preferred policy actions of microprudential and macroprudential regulators. For example, in a downturn the macroprudential authority might judge that loosening regulatory requirements could help to protect and enhance the resilience of the financial system as a whole, whereas the microprudential regulator may place more weight on maintaining standards to protect individual firms.

Implementation of directions is potentially quicker than for recommendations: a power of direction requires the PRA or FCA not only to comply but also to act as soon as practicable. This could be an important consideration in relation to a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer, where certainty on changes may be important to enable firms to alter their capital plans as soon as possible.

Furthermore, powers of direction allow for greater accountability and policy predictability than recommendations. In addition to the duty to explain how a policy action will help the FPC meet both its objectives, which applies both to recommendations and to directions to the regulators, the FPC is required to produce and maintain a statement of general policy it proposes to follow for each of its direction powers. These statements set out in general terms how the power works, the types of risks that it will be used to address and in what situations the FPC would expect to use the power. The FPC is also expected to provide as part of the statement a list of key indicators that it will consider when judging if policy action using the tool in question is appropriate. Ex ante explanations of this depth are not possible or practical for the FPC’s recommendation power because of its breadth.

The information contained within the policy statement helps market participants discern the FPC’s policy reaction function and serve as useful context when the FPC is held to account for its actions after the fact. Providing the FPC with direction powers will therefore provide firms with greater certainty regarding the leverage ratio requirements that they will face when the FPC’s framework is fully put in place as the FPC will be required to state how it intends to use its powers ahead of their use. Linking the FPC’s leverage ratio powers to existing capital buffers (e.g. the additional leverage ratio buffer for systemic firms being linked to G-SIB and SRB capital buffers) in legislation will provide industry with certainty as to how those powers will work. This increased transparency will be important for firms to understand and anticipate how the FPC’s actions will affect their capital planning. As stated in the Chancellor’s letter to the Governor on 26 November 2013 requesting that the FPC undertake a review of leverage, this government strongly supports the FPC’s aim to bring greater certainty to the medium term capital framework for UK firms[footnote 23].

However, whilst the above suggests there are benefits associated with granting the FPC more powers of direction, there are also potential benefits from prescribing a set of tools which is proportionate to the threat being posed. This means a set of tools whose role and effects can be more clearly defined, which avoids undue complexity and helps to ensure public accountability and communication. By maintaining simplicity and clarity of the macroprudential framework, the FPC is more likely to convey a clear reaction function (i.e. improve predictability of its actions) which helps shape expectations of future FPC actions.

Clearly, having a large number of overlapping tools with several possible permutations of use, calibration and interactions between them, would make it especially difficult to establish a clear and coherent use for each tool and therefore make it extremely challenging to convey a policy reaction function. This would make it difficult to shape expectations and could result in greater uncertainty.

4.2 Minimum leverage ratio requirement

The FPC has recommended that it should be given a power of direction to set a minimum leverage ratio requirement for all banks, building societies and investment firms regulated by the PRA. The FPC has stated that it intends to set this minimum requirement at 3% and that prior to the introduction of the international requirements in 2018, this minimum would be applied to systemically-important banks and building societies. The minimum requirement would be applied to all other firms in scope from 2018.

The government agrees that the FPC should be given a power of direction to set a minimum leverage ratio requirement for all banks, building societies and investment firms regulated by the PRA. As explained above, the unweighted nature of the leverage ratio ensures that all firms preserve a minimum amount of capital to absorb losses regardless of the risk profile of their assets, guards against firms underestimating the true riskiness of their assets and provides a directly comparable measure across firms.

The FPC has stated that it expects to adopt the internationally agreed Basel definition of the exposure measure, as implemented via European law, when using its powers of direction over the leverage ratio[footnote 3]. Both the Basel Committee and the EBA have committed to reviews of the leverage ratio, which could lead to revisions to the definition of the exposure measure.

The FPC’s review indicated that the Committee will expect firms to meet the minimum leverage requirement primarily with CET1 capital (at least 75% of eligible capital) and that firms should use AT1 with conversion trigger rates of at least 7% CET1 ratio. The Basel agreement currently requires banks to disclose their leverage ratios using a total Tier 1 definition of capital with no restrictions on the use of Additional Tier 1 (AT1). The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision will undertake a review of leverage ratio capital standards in 2017 and the government expects that the FPC will review its approach in light of the final Basel position.

Question 1:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a minimum leverage requirement to all firms?

4.3 Additional leverage ratio buffer

As discussed above, there is international agreement that firms that are systemically important, either globally or domestically, should be required to hold additional capital buffers reflecting the higher costs to the wider financial system of their distress or failure. The FPC has recommended that it be given a power of direction to require the PRA to apply a systemic leverage buffer requirement to such firms, in proportion to the size of these firms’ systemic risk weighted capital buffers, arguing that this is necessary to maintain the relationship between the risk-weighted capital ratio and leverage ratio regimes. Several other jurisdictions, including Denmark, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the US have already announced that they will apply higher leverage requirements to systemic firms. The FPC has stated that it intends to set the ratio of systemic leverage ratio buffer at 35% of systemic capital buffers and that firms will be expected to meet this buffer with CET1 only.

The government agrees with the FPC that systemically important banks should be subject to higher leverage buffers. The government proposes to provide the FPC with a power of direction to require the PRA to impose a leverage ratio buffer, proportionate to the size of risk-weighted systemic capital buffers, on the following categories of firms:

- G-SIBs

- other major domestic UK banks and building societies, including ring-fenced banks

4.4 G-SIBs

CRR/CRDIV requires that firms that have been identified as G-SIBs by the Financial Stability Board will be required to hold additional CET1 capital (up to 3.5 percentage points) on top of their existing RWA capital requirements. These buffers will be rolled out from 2016, with the requirements expected to be fully in place by 2019. The government proposes that the FPC should have a power to direct the PRA to apply additional leverage ratio buffers to these firms, in proportion to their G-SIB buffers. Table 4.1 illustrates the range of leverage ratio requirements that would apply to G-SIBs using the FPC’s proposed calibration of 35% of systemic risk capital buffers.

4.5 Table 4.1: G-SIB additional leverage ratio buffers

| Firm | GSIB capital buffer (per cent) | Leverage ratio additional buffer (per cent) | Total leverage ratio requirement (per cent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Chartered | 1.0 | 0.35 | 3.35 |

| RBS | 1.5 | 0.525 | 3.525 |

| Barclays | 2.0 | 0.70 | 3.70 |

| HSBC | 2.5 | 0.875 | 3.875 |

Source: HMT calculations

Note: Totals assume a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer rate of 0%.

4.6 Ring-fenced banks and large building societies

The government has previously announced that, as part of its implementation of the recommendations made by the Independent Commission on Banking, ringfenced banks and large building societies will be required to hold an additional equity capital buffer of up to 3%, over and above the tougher new Basel III standards[footnote 24]. The government intends to use the discretionary ‘Systemic Risk Buffer’ (SRB), a macroprudential tool which is provided for in European legislation, to implement this requirement[footnote 25].

Consistent with the government’s commitment to have the ringfencing legislation fully in place before the end of this Parliament, the government intends to lay the SRB legislation in Parliament before the end of this year, and the SRB framework will then be set by the FPC and PRA in 2015. The legislation will provide that the methodology for calibrating SRB buffers will determined by the FPC, and will be applied by the PRA, who will have discretion over the rate set for each individual institution. Affected firms will be required to meet SRB capital buffer requirements from 2019, when ringfencing comes into force.

The government proposes that the FPC should have a power to direct the PRA to apply additional leverage buffers to ringfenced banks and large building societies, in proportion to the size of their systemic risk buffers. These leverage buffers would apply from 2019. The benefits of applying a leverage buffer to ring-fenced banks and large building societies will need to be considered carefully against the potential costs to ringfenced banks and other low-risk business models of having to meet additional leverage ratio requirements. Table 4.2 illustrates the range of leverage ratio requirements that would apply to ring-fenced banks and large building societies using the FPC’s proposed calibration of 35% of systemic risk capital buffers.

4.7 Table 4.2: RFB and large building societies’ additional leverage ratio buffers

| SRB capital buffer (per cent) | Leverage ratio additional buffer (per cent) | Total leverage ratio requirement (per cent) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.35 | 3.35 |

| 2 | 0.70 | 3.70 |

| 3 | 1.05 | 4.05 |

Source: HMT calculations

Note: Totals assume a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer rate of 0%.

The government notes that the regulators plan to consult extensively next year on the FPC and PRA’s proposals for the SRB framework. The government believes that the consultation should address the impact of different levels of calibration for the SRB on important factors such as: the levels of lending to the real economy; the degree of competition in retail banking; the impact on lenders with low average risk weights; and the maintenance of a diverse set of business models in the banking industry. Given the importance of these issues, a consultation of 2-3 months will be necessary to provide firms with adequate opportunity to feed in their views and shape the conclusions of the FPC and PRA Board.

Question 2:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a leverage ratio buffer to UK G-SIBs with reference to their G-SIB capital buffer?

Question 3:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a leverage ratio buffer to UK D-SIBs with reference to their systemic risk buffer?

4.8 Countercyclical leverage ratio buffer

The FPC has recommended that it should be given a power to require the PRA to impose a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer (CCLB). This buffer would apply to all firms that are required to meet the minimum leverage ratio requirement.

The government agrees that the FPC should have a power of direction over the countercyclical leverage ratio in order to ensure that, during the upswing of the credit cycle, when systemic risk tends to increase, firms remain sufficiently protected against uncertainties and risks, including those arising from asset classes with low risk weights.

The FPC has indicated that it expects as a guiding principle that it would set the CCLB rate as a fixed proportion of the prevailing countercyclical capital buffer (CCB) rate. The CCB is an additional buffer of CET1 capital that can be used to build resilience during upswings in the credit cycle and restrain over-exuberant lending ahead of periods of financial distress. These additional requirements are then removed once risks have crystallised in order to support the recovery of credit provision. The default setting of the CCB is zero. The FPC is responsible for the quarterly decision on the CCB buffer rate for the UK. The FPC’s decisions on the UK rate of the CCB are informed by the “buffer guide”, which translates the credit to GDP gap into a suggested setting for the CCB rate, as well as other core indicators set out in its policy statement[footnote 27]. By adjusting the level up or down, the FPC is able to adjust the capital held against the exposures of UK banks, building societies and larger investment firms. Firms have up to a year to comply with increases in the CCB in order to provide sufficient time for them to meet the requirement. The FPC can set a deadline shorter than a year where justified by exceptional circumstances.

4.24 Like the CCB, a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer would be used to build resilience and restrain balance sheet growth during credit booms. These additional requirements would then be removed once risks have crystallised in order to support the recovery of credit provision. The FPC expects as a “guiding principle” to set the CCLB rate at 35% of the CCB rate. For example a CCB rate of 1% would imply an additional countercyclical leverage buffer of 0.35%. For example a CCB rate of 1% would imply an additional countercyclical leverage buffer of 0.35%. However, the government proposes to give the FPC discretion to move the CCLB independently of the CCB. The government would welcome the views of respondents on this approach. The FPC also proposes that, as with the counter-cyclical capital buffer, firms should be required to meet the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer with CET1 capital.

Mirroring the framework for the CCB, firms would normally have 12 months to meet any increases in the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer. The FPC also proposes to consider the option to extend the compliance timetable to up to 24 months for firms or groups of firms. This option could, for example, be used to avoid possible adverse effects created by firms that have limited capital raising options undertaking rapid shifts in balance sheet composition or size in order to meet higher requirements. The government believes that the regulators should seek the views of the industry on this issue as part of any consultation prior to the introduction of new PRA rules implementing the CCLB.

The Basel III agreement and CRD IV provide for reciprocity between national regulators with regards to adjustments in the CCB rate up to 2.5 per cent, and voluntary reciprocity above this level. For example, if the FPC were to raise the CCB rate for UK banks’ UK exposures, pursuant to the principle of reciprocity other national regulators would be expected to require banks and investment firms to hold an equivalent capital requirement against their UK exposures, at least up to rates of 2.5 percent. This helps to ensure a level playing field and prevents the effectiveness of this tool being undermined by foreign lenders who might otherwise step in to make up any reduction in credit supply.

As the FPC notes in its review document, there is currently no equivalent EU or international agreement in relation to a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer as exists with respect to the CCB. As a result, at least initially, the FPC will not be able to rely on regulatory authorities in other jurisdictions to operate a system of reciprocity in relation to the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer. While this could reduce the effectiveness of this macroprudential tool, for example because UK branches of European Economic Area firms would not automatically subject to the countercyclical leverage ratio requirements set by the FPC, the government agrees with the FPC that there remain significant financial stability benefits to giving the FPC this power now.

The government notes that many of the responses to the FPC’s July 2014 consultation paper raised the issue of complexity as an argument against the introduction of elements of the FPC’s initial proposals, including the proposal to introduce a countercyclical leverage power. The FPC has taken on the views of respondents and recommended a simpler leverage ratio framework. Regarding the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer in particular, the FPC propose that countercyclical leverage ratio buffers will be rounded to the nearest 10 basis point increment to avoid small movements in leverage buffer requirements due to changes in buffer levels in countries to which firms have relatively small exposures.

The government previously agreed to grant the FPC a countercyclical leverage ratio power in 2018, subject to a review in 2017. However, in light of the evidence produced by the FPC in its final review, the government has concluded that the FPC should be granted this power as soon as practicable so that the FPC can take action to address risks that might arise in the interim.

Question 4:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power of direction to require the PRA to impose a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer as soon as practicable?

Question 5:

What would be the advantages and disadvantages of tying the rate of the CCLB to the rate of the CCB in the statutory instrument?

4.9 Implications of leverage ratio requirements

The implications of a leverage ratio framework are intrinsically linked to the calibration of the requirements imposed on firms. The FPC is only permitted to take action if it judges it to be necessary to address financial stability risks and, subject to achieving that objective, it must support the economic objectives of the government. Moreover, the FPC has a statutory obligation to exercise its functions with regard to the principle of proportionality, and is required to publish a cost benefit analysis whenever it exercises its powers, including its powers of direction (unless it judges that it is not reasonably practicable to do so). Both the costs and benefits will therefore be carefully considered by the FPC whenever it considers deploying these tools. The FPC’s report includes a proposed calibration of the framework and a cost-benefit analysis that assesses the impact of this calibration.

The government expects the FPC‘s leverage ratio framework to benefit the UK economy by boosting the resilience of the financial system to systemic crises, which are associated with significant economic costs. The government believes that the resilience of the financial sector will be improved due to leverage ratio requirements complementing existing RWA capital ratios by: limiting balance sheet stretch; providing additional protection against uncertainties and risks that are difficult to model; increasing the resilience of systemic institutions; and enhancing the FPC’s ability to increase resilience further during upswings of the credit cycle through the use of a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer. This should reduce the frequency of periods of financial instability while improving the ability of the financial system to weather losses when they do occur. These two effects should reduce the economic output forgone as a result of these periods of instability. On 31 October 2014, the FPC published an impact analysis in its final report on the leverage ratio framework. This consisted of an assessment of the impact and effectiveness of the powers of direction that the FPC recommended it be granted on the basis of the FPC’s proposed calibration. The FPC’s impact analysis estimated that a permanent reduction in the probability of a crisis occurring of 1% would lead to an expected GDP increase of £4.5bn per annum.

As the FPC’s impact analysis notes, the increase in capital requirements that would result from the introduction of its proposed leverage framework could result in a higher cost of credit to the real economy. However, the FPC assesses that, on the basis of its proposed calibration, the benefits arising from a reduced probability of future financial crises would outweigh the costs arising from higher real economy borrowing costs.

Firms are currently required to meet RWA capital ratios based on the composition of their exposures, and the government’s proposals would also require them to comply with leverage ratio requirements. The government recognises that, depending on the FPC’s calibration of its framework, these additional requirements could impose costs on some firms and negatively impact their ability to compete with firms that are less bound by the new requirements. Firms with low average risk weights are most likely to find that they are bound by the FPC’s proposed leverage requirements.

For firms that are bound by the leverage ratio, assuming that they decide not to run down any voluntary buffers that they may hold above regulatory requirements, they can respond to an increase in leverage requirements by:

- increasing retained earnings, for example by reducing cash dividend payments or discretionary staff remuneration

- issuing new equity and/or reducing other forms of funding

- reducing their exposures by reducing the size of their loan portfolios and/or changing the composition of their balance sheets towards higher risk assets with higher returns

Where firms bound by the leverage ratio choose to reduce their reliance on debt financing, this would tend to decrease their return on equity due to the generally lower cost of financing through debt relative to equity financing. Firms may choose to absorb this cost, thereby reducing their profitability, or increase lending spreads in order to pass this cost onto consumers. Firms may therefore be incentivised to change the composition of their balance sheets towards higher risk assets with higher returns in order to maintain return on equity, though these higher risk assets would attract higher risk-weighted capital requirements. As the FPC notes in its impact assessment, this could increase incentives for firms bound by the leverage ratio to lend to higher risk-weighted borrowers, including as SMEs.

The FPC has said that it expects that its proposed calibration of the leverage framework would result in risk weighted capital requirements remaining the binding constraint for the majority of firms, but for some firms the leverage ratio requirements imposed by the FPC would likely be the binding regulatory requirement.

As mentioned above, the FPC has published an impact analysis in its Review. The government is not therefore publishing a separate impact assessment to accompany this consultation, but it will publish one when the legislation is finalised and laid in Parliament, alongside a consultation response document.

4.10 Procedural requirements when implementing directions

4.38 The FPC is not required to consult prior to exercising its powers of direction, but is required by the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) to publish explanations when exercising its powers of recommendation and direction. These explanations must include a cost-benefit analysis, where reasonably practicable. When the PRA or FCA take action to implement a direction from the FPC, any procedural requirements that are applicable under the Financial Services and Markets Act (FSMA) 2000 would normally apply. For example, if the regulator makes rules to implement an FPC direction, it would be required to undertake consultation on those rules, including a cost-benefit analysis.

When creating macroprudential tools in secondary legislation the government is able to modify or exclude any procedural requirements that would otherwise apply under FSMA 2000 on a tool-by-tool basis[footnote 28].

The government believes explanations and cost-benefit analysis by the FPC, coupled with PRA procedural requirements for consultation on and cost-benefit analysis of the implementation of relevant rules, are a vital accountability mechanism. The FPC’s leverage tools could have far-reaching implications for lenders and borrowers, and it is vital that the Committee’s decisions are as open and transparent as possible. Appropriate periods of consultation will allow the regulators to make use of the expertise of the industry in the design of rules, while cost-benefit analysis is an important tool for the public and Parliament to hold the FPC and the regulators to account for their decisions.

The government does not propose to waive procedural requirements for the FPC’s leverage ratio powers of direction over the minimum requirement and the additional buffers for systemically important firms. If the FPC changes the calibration of these elements of the leverage ratio framework, the PRA will need to consult, including a cost-benefit analysis, on the implementation of this action via its rules.

In some cases, it may be necessary to act quickly in order to prevent damage to the stability of the financial system. In urgent cases, both the PRA and FCA have the ability to waive consultation requirements in order to take action quickly[footnote 29]. In the case of the PRA, consultation requirements can be waived where a delay would be prejudicial to the safety and soundness of the firms it regulates and in the case of the FCA, the test is that a delay would be prejudicial to consumers. It is clear that where a delay in implementing an FPC direction could provoke severe financial instability, this would negatively impact both firms and consumers.

The government proposes that procedural requirements with respect to the use of the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer should apply as follows.

- if the FPC sets the CCLB rate as a fixed proportion based directly on CCB rates, the PRA will be required to consult, including an assessment of the costs and benefits, before first applying any requirements. However, to the extent that this scaling factor remains unchanged the PRA will not be required to consult or carry out a cost-benefit analysis when the FPC changes the UK CCB rate or other CCB rates change

- if the FPC wishes to subsequently change the scaling factor used to calculate the CCLB, the PRA would be required to produce a cost-benefit analysis of the action

- if the FPC decides to use the CCLB independently from the CCB, then the PRA would be required to consult, including an assessment of the costs and benefit, before making any rules to implement the FPC direction

4.44 In some cases, it may be necessary to act quickly in order to prevent damage to the stability of the financial system. In urgent cases, both the PRA and FCA have the ability to waive consultation requirements in order to take action quickly. In the case of the PRA, consultation requirements can be waived where a delay would be prejudicial to the safety and soundness of the firms it regulates and in the case of the FCA, the test is that a delay would be prejudicial to consumers. It is clear that where a delay in implementing an FPC direction could provoke severe financial instability, this would negatively impact both firms and consumers.

Question 6:

Do you agree that all procedural requirements should apply to changes in the minimum requirement and additional buffer or would there be benefits in waiving procedural requirements in some situations?

Question 7:

Do you agree that the procedural requirements for the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer should mirror the approach used for the CCB?

5. Summary of consultation questions

Question 1:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a minimum leverage requirement to all firms?

Question 2:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a leverage ratio buffer to UK G-SIBs with reference to their GSIB capital buffer?

Question 3:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power to require the PRA to apply a leverage ratio buffer to UK domestic systemically important banks with reference to their systemic risk buffer?

Question 4:

Do you agree that the FPC should have a power of direction to require the PRA to impose a countercyclical leverage ratio buffer as soon as practicable?

Question 5:

What would be the advantages and disadvantages of tying the rate of the CCLB to the rate of the CCB in the statutory instrument?

Question 6:

Do you agree that all procedural requirements should apply to changes in the minimum requirement and additional buffer or would there be benefits in waiving procedural requirements in some situations?

Question 7:

Do you agree that the procedural requirements for the countercyclical leverage ratio buffer should mirror the approach used for the CCB?

-

The structure of the FPC and its objectives are set out in Part 1A of the Bank of England Act 1998, as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012. ↩

-

As set out in section 9Q of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act, 2012) ↩

-

As set out in section 9P of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) ↩ ↩2

-

The Treasury may make use of an emergency procedure whereby the instrument become law immediately but then must be approved within 28 days if it is to remain in force. ↩

-

This is the problem that firms that are large, systemic and too complex for their failure to be safely managed without serious economic consequences or recourse to public funds are perceived to benefit from an implicit government guarantee. ↩

-

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/gfsr/2014/02/pdf/text.pdf ↩

-

https://www.g20.org/sites/default/files/g20_resources/library/Pittsburgh_Declaration_0.pdf ↩

-

http://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/recommendations/2013/ESRB_2013_1.en.pdf ↩

-

http://www.ecgi.org/documents/icb_final_report_12sep2011.pdf ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/32556/whitepaper_banking_reform_140512.pdf ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financialstability/documents/fpc/statement120323.pdf ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/191584/condoc_fpc_tools_180912.pdf ↩

-

The FSA was the sole firm-level regulator prior to its dissolution and the establishment of the PRA and FCA on 1 April 2013 ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/records/fpc/pdf/2012/record1209.pdf ↩

-

Barclays, HSBC, Santander UK, Lloyds Banking Group, Royal Bank of Scotland, Co-operative Bank, Nationwide and Standard Chartered. ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/Records/fpc/2013/record1304.aspx. This recommendation was applied to the following firms: Barclays, Co-op, HSBC, Lloyds, Nationwide, RBS, Santander UK and Standard Chartered. ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/records/fpc/pdf/2013/record1304.pdf ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/news/2013/181.aspx ↩

-

PRA (2013b) ↩

-

Section 9H(8) of the Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012) provides that directions cannot require the regulators to do anything outside their legal power. ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/news/2013/chancellorletter261113.pdf ↩

-

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/223566/PU1488Banking_reform_consultation-_online-1.pdf A large building society is one that is considered to be similarly systemic to large ring-fenced banks. ↩

-

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/financialstability/Documents/fpc/policystatement140113.pdf ↩

-

Section 9I(2) Bank of England Act 1998 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012). ↩

-

Section 138L(1) and (2) Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (as amended by the Financial Services Act 2012). ↩