Summary of responses and government response

Updated 25 June 2019

Joint statement from Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), Food Standards Agency (FSA) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland and Food Standards Scotland.

1. Introduction

Following tragic events concerning allergen related incidents, the government has been reviewing the allergen labelling framework to ensure that the UK’s allergic consumers can have more trust in the food they consume.

It is estimated that 1 to 2% of adults and 5 to 8% of children in the UK have a food allergy. There is no cure for food hypersensitivity. It demands life-long management. There is no single measure that can remove the risk for a consumer. No combination of measures can eradicate a food hypersensitive person’s own duty of care to keep themselves safe. Taken as a whole, people with a food hypersensitivity face gaps in their equity of food choices, reduced quality of life, and serious risks to their health and wellbeing, with those who are 16-24 years old disproportionately at risk of serious harm.

It is crucial that consumers are provided with accurate and easily accessible information about allergens in foods, and clearer labelling will help to mitigate against consumers facing consequences that can be disastrous.

The legislative framework around the provision of food allergen information is largely set by the Food Information to Consumers (FIC) Regulation (EU 1169/2011). Under FIC, food which is prepacked, for example a ready meal sold in a supermarket, must be labelled with full ingredients with any of the EU’s 14 specified food allergens (see Annex A) emphasised. With non-prepacked food, however, which includes food that is prepacked for direct sale, domestic Food Information Regulations 2014 (FIR) (England) and parallel FIR regulations in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales, allow food businesses to make allergen information available by any means that they choose; including orally by a member of staff.

Government has been looking specifically at amending the legislative framework around food that is prepacked for direct sale (PPDS). Put simply, PPDS foods are foods that are packed on the same premises from which they are being sold, before they are offered for sale. These might include a packaged salad or baguette from a shop that was made by staff earlier in the day, packaged in the kitchen and then placed on a shelf for customers to purchase. It is often difficult for consumers to distinguish between prepacked and PPDS foods, and anecdotal evidence suggests that consumers assume that the absence of allergen information on packaged foods means food allergens are not contained in the product, which may not be the case for PPDS foods.

Government has a key role to play in setting the regulatory framework to ensure that consumers are provided with the information they need to allow them to make safe food choices. The Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), the Food Standards Agency (FSA) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and Food Standards Scotland (FSS) have worked closely together to conduct a review of the allergen labelling framework for PPDS products.

On 25 January 2019, Defra, FSA and FSS launched a UK wide consultation on proposed amendments relating to the mandatory information, form of expression and presentation of allergen labelling information for PPDS foods. The focus was on four proposed policy options.

The consultation was carried out through the online survey Citizen Space, and ran for nine weeks from 25 January to 29 March 2019. In total we received 1887 responses, from across the UK; of which:

- 1625 identified as individuals

- 126 identified as businesses with 30% identifying as a large business and 67% identifying as a micro, small or medium business

- 83 identified as public sector bodies, the majority being local authorities

- 29 identified as NGOs, including charities, such as allergen patient groups, and trade associations representing businesses

There were 24 respondents that could not be attributed to one of the other four types with complete confidence.

Over the course of the consultation, we also conducted eight stakeholder engagement events in England, two workshops were held in Northern Ireland and three in Wales with multiple stakeholder groups. In total, 108 people attended and contributed to the workshops in England (please refer to table 1 for a further breakdown).

Table 1. Number of participants involved in the workshops in England and Wales by stakeholder group

| Stakeholder group | Total number of attendants |

|---|---|

| Local Authorities | 62 |

| Businesses | 44 |

| Consumers | 34 |

| Allergy patient groups & healthcare professionals | 11 |

Food Standards Scotland carried separate stakeholder engagement in Scotland. This included, a survey of visitors to a public event, designed to appeal to all allergy sufferers (including those with food hypersensitivity) and a workshop attended by food safety trainers, food businesses, charities and enforcement officers.

This document summarises the responses to the consultation across the UK.

2. The consultation questions

The consultation sought opinions and comments on proposed options to improve the way allergen information is given to the consumer, focusing specifically on PPDS products. Over the first five sections the questions looked to gather comprehensive views concerning: PPDS definition, the policy options, business size definitions, exemptions and implementation, and thoughts on the impact assessment. The final section looked at the reporting of “near misses”. The information gathered from this final section was designed to fit into a larger piece of work being undertaken on “near misses” by the FSA.

2.1 Prepacked for Direct Sale (PPDS) definition

Current regulations do not specifically define PPDS in legislation, and ongoing engagement with stakeholders indicated that there was some confusion around the interpretation and understanding of what PPDS is.

For the consultation we used the FSA’s technical guidance on allergen labelling, set out below (as FIC does not provide a specific definition of PPDS), and gathered views about the quality and scope of this interpretation. “Prepacked foods for direct sale: This applies to foods that have been packed on the same premises from which they are being sold. Foods prepacked for direct sale are treated in the same way as non-prepacked foods in EU FIC’s labelling provisions. For a product to be considered ‘prepacked for direct sale’ one or more of the following can apply:

- it is expected that the customer is able to speak with the person who made or packed the product to ask about ingredients

- foods that could fall under this category could include meat pies made on site and sandwiches made and sold from the premises in which they are made[footnote 1]”

2.2 Policy options

Four policy options were proposed, one non-legislative (promote best practice) and three legislative (mandate ask the staff labels, mandate allergen labelling, mandate full ingredient labelling). Respondents were asked to state a preferred policy option (a combination of options was also allowed) and to justify their selection. Other relevant information about the options was also gathered, for example, how government might promote best practice.

2.3 Business size definitions, exemptions and implementation

The consultation gathered views on which businesses any new policy should apply to, whether any businesses should be exempt (and what the grounds for any exemption should be) and how long businesses should be given to implement any new policy.

2.4 Impact assessment

The consultation and workshops also included questions related to the impact assessment produced for the consultation. These questions generally focused on gathering further evidence and insight on the calculations and assumptions made in the impact assessment. They also sought to identify any additional impacts or benefits the policy options may have, that had not been considered. The evidence obtained from the consultation has been used to inform the revised impact assessment.

2.5 Reporting non-fatal anaphylactic shock incidents (“near misses”)

The last section of the survey contained a question about how relevant authorities (for example, the National Health Service, Local Authorities and the FSA) can work more cooperatively together in the domain of reporting and addressing serious, non-fatal incidents of anaphylactic shock - “near-misses”. While this information is not strictly relevant to the central purpose of the consultation, data gathered here will fit into a larger piece of work being undertaken by the FSA.

3. Summary of responses

All respondents had the opportunity to comment on every policy option being considered.

The emphasis of the analysis has been largely qualitative, with the aim being to understand the range of key issues raised by respondents, and the reasons for holding their particular views. This includes potential areas of agreement and disagreement between different groups of respondents.

Within each of the workshops, participants had the opportunity to discuss the benefits and risks of the policy options, and which was their preferred. These discussions were conducted in small groups, and therefore there is a risk that participants were biased in their opinion or did not feel comfortable expressing views that differed from the majority of the group. With that in mind, any preferences expressed within these discussions did not supersede the individual’s or business’s response to the online consultation. The aim of these discussions was to understand the reasons behind the views expressed.

3.1 Prepacked for Direct Sale (PPDS) definition / Other types of food government should review

We asked respondents whether they agreed with the FSA’s definition of PPDS, and for those that did not we asked for other factors that should be taken into account when considering whether a product is PPDS.

In the survey, over 70% of businesses, individuals and public sector bodies that responded agreed with the PPDS definition, whilst a small majority of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) disagreed. The key reason for disagreeing with the definition was that it was not comprehensive enough. Specifically, businesses, and allergy patient groups and healthcare professionals, raised concerns around the assumption that consumers would be able to speak to the person who had prepared the food, suggesting that this might not always be the case.

The consultation sought to identify whether respondents thought other types of non-prepacked food should be reviewed in the future. For those that said yes, they were asked which of the following should be reviewed in the future and their reasons:

a. Food packed on the sales premises at the consumer’s request

b. Food not packed, such as loose items sold to the consumer, without packing and meals served in a restaurant or cafe

c. Non-prepacked food ordered via distance selling, for example a takeaway pizza ordered over the phone or via the internet

d. Other

The majority of individuals, public sector bodies and NGOs thought that the government should review other types of non-prepacked food (loose foods and foods packed at the consumer’s request), compared to around half of businesses. The key reason given for reviewing other types of non-prepacked food was that labelling should be consistent across all products and that the introduction of different rules for PPDS products only could cause confusion for all stakeholder groups. Following Brexit we will have the opportunity to review food labelling to ensure we have a framework that meets the needs of UK consumers and producers.

Individuals were also keen that “may contain” labels are reviewed, as well as the issue of cross-contact. Though this is was not directly covered in the workshops, there was a strong sentiment from food allergic consumers that these issues should be in scope for future review.

3.2 Policy options

Under this section we asked what respondents’ preferred policy option was and whether there was a preference for a combination of options. There were also a number of policy option specific questions such as: whether anything else should be included in best practice, and whether there are alternative options not proposed that we should be considering.

Option 1 – Promote best practice

Individuals, businesses, NGO’s and public sector bodies

This option was viewed positively in consultation responses and with all stakeholder groups during workshops and seen as necessary to improve wider business practices (including beyond PPDS). However, it was recognised as lacking legal standing and was largely only preferred when applied in combination with other options. As a standalone option it was felt it does not go far enough and may be difficult to define.

In all the workshops, across the UK option 1 was often considered to be a necessary supplement to the other options. For example, a common point made was that option 1 would need to be used in tandem with regulatory options to support the delivery and implementation of change.

The top suggestions for promoting best practice were: training for businesses and staff; awareness raising campaigns; and incorporating allergens awareness and practice into inspections or the Food Hygiene Rating Scheme.

Option 2 – Mandate “ask the staff” labels on packing of food prepacked for direct sale, with supporting information for consumers in writing

Individuals

Individuals were largely unsupportive of option 2 as it is similar to the current situation which they consider to be inadequate. The key risks for option 2 focused on the possibility that staff may not know what allergenic ingredients were in food, staff may make an error when conveying information, and staff may not always be around to ask. It was also noted in workshops that not all consumers feel confident to ask (especially younger consumers) or engage with businesses.

Businesses

Around half of businesses that responded preferred option 2 (sometimes in combination with option 1). The main reason given was that it was thought to be the simplest regulatory option in terms of implementation for businesses, particularly for small and micro businesses. Businesses also thought that this option would be the best for opening dialogue between consumers and staff in food businesses around allergies.

Retailers raised concerns about option 2 during a workshop, emphasising the perceived risk of placing too much responsibility on staff, who may have limited competency in dealing with allergen information.

Public Sector Bodies

A small portion of public sector bodies identified this as their preferred option, chiefly citing ease of identifying non-compliance. It was also noted that option 2 meant there was no risk of mislabelling. In a workshop with Local Authorities, a similar point was agreed, with participants feeling option 2 had the best chance for high compliance and ease of enforcement. They did however raise concerns around the fact that under this option allergen ingredient information provision was still based on staff knowledge, and the consumer asking the right person.

NGOs

About half of non-governmental organisations who expressed a preference in the consultation favoured a combination of the options, most notably a combination of options 1 and 2 or 1 and 3. Their reasons were similar to businesses in that they were the most practical and least costly options. It was noted that having option 2 would prompt consumers to ask, and make them more comfortable about asking. Some NGO’s expressed a preference for options 2 and 3 together and noted that as option 3 only included the 14 allergens, option 2 would be needed alongside it for those with allergies outside of the 14.

Option 2 would require businesses to provide supporting information in writing. We asked respondents whether they thought this supporting information should be the 14 allergens, or full ingredient labelling, and received the following responses:

Fifty two percent of businesses preferred to supply information on the 14 allergens only, whereas 86% of individuals wanted a full list of ingredients. NGO and Public Sector Body respondents were roughly evenly split.

The main reason for listing all ingredients was because some people have allergies outside of the EU’s list of 14 allergens and full ingredients would increase the safety for these consumers.

The main reasons against doing so, however, was that it was considered to be burdensome and costly for businesses, particularly small businesses. It was also argued that it would mean there was too much information for consumers to look through.

Option 3 – Mandate name of the food allergen labelling on packing of food prepacked for direct sale

Individuals

In the survey individuals showed limited support for option 3 (8 %). The key concern around this option was that many people have allergies outside the listed 14. This concern was echoed by allergic consumers in workshops. It was felt that only full ingredient labelling (option 4) would allow consumers to make a safe and informed decision due to the diversity of foods capable of causing allergic reactions. It was noted that the Annex II allergens did not cover foods such as peas, lentils, other legumes and pulses which are known to cause allergic reactions.

Businesses

Eleven percent of businesses supported this option. These businesses noted that it would be less burdensome than option 4 and would be good for consumer safety. However, many businesses had concerns that option 3 would require significant time and financial expenditure for businesses to implement, particularly small and micro businesses. Sourcing and printing the labels would be costly and it would be expensive when businesses wanted to bring in new products or when ingredients were substituted.

The consultation indicated businesses had concerns regarding the feasibility of safely implementing this option. This was particularly in relation to mislabelling products, especially in busy kitchen environments, where products containing different food allergens are made simultaneously, and which are often very different environments compared to factory environments where prepacked goods are typically prepared. Business also expressed wider concerns about a range of potential actions small and micro businesses may take if option 3 was legislated:

- stop advanced preparation and pre-packaging of loose food and/or replace with prepacked food, possibly leading to reduced consumer choice

- continue, but choose to pack at the customer’s request, which may introduce additional food hygiene and allergen cross-contact risks

- find it more difficult to substitute ingredients, which may limit consumer choice and lead to potentially increased food waste and cost

Within the workshops, businesses and retailers noted that this option allowed for continued flexibility in terms of substitutions. Their concerns were consistent with those raised in the online consultation.

Public Sector Bodies

Option 3 was generally favoured by public sector bodies either on its own (39%) or in combination with other options. Comments focused on the ease of implementation and transparency associated with option 3. It was also seen as a compromise for the customer and business.

Concerns were raised, however, around the risks of mislabelling (similar to those indicated by business), giving the consumer a false sense of security, and reducing the conversation between the consumer and businesses.

NGOs

In the survey support from NGO’s for option 3 was limited (12%), although in combination with other policies (1 or 2) there was stronger support. As noted above some thought that option 3 would need to be combined with option 2, as some people have allergies outside the 14.

Within the workshop, allergy patient groups and healthcare professionals viewed it as a good practicable solution for all businesses which has been tried and tested in the retail environment.

Option 4 – Mandate name of the food and full ingredient list labelling, with allergens emphasised, on packing of food prepacked for direct sale

Individuals

Option 4 was the overwhelming policy choice for individuals. 73% of all individuals that responded supported option 4. The key reasons given for this preference were that: it was considered the safest option for consumers; it provides them with the best information to make an informed decision; and it supports those eating PPDS with allergies outside the EU’s 14 listed allergens. They also supported option 4 as it was not reliant on staff members who they reported do not always know all the allergy information or are not always available to ask.

Comments in workshops attended by food allergic consumers were consistent with the consultation, with references made to the increased safety and information provided by option 4.

In a separate survey of visitors to a public allergy and free from event in Scotland, of the 117 responses received, 70% supported option 4.

Businesses

Full ingredient labelling was the preferred policy option for 13% of businesses. The responses indicated that businesses felt option 4 created the same challenges as with option 3. Key areas of focus were cost, difficulties implementing full ingredient labelling and risk of mislabelling. Businesses also highlighted the complexity involved in frequently updating and clearly communicating accurate ingredient information down the supply chain to a label.

Other comments from industry in the survey indicated specific concerns that small and micro businesses have around option 4:

- smaller businesses are less able to use long-term contracts to maintain a consistent product or technical specification to prevent ingredient substitution

- there is typically more risk of accidentally experiencing cross-contact in a small kitchen, than in a larger factory with controls like sequencing of production

- supply chains for small/micro businesses are more prone to disruption requiring rapid ingredient substitution

- larger businesses typically prepare pre-packed food and have access to greater resources for quality assurance than smaller/micro businesses selling PPDS.

For the businesses that supported option 4, they felt this was the safest option for the consumer, and provided information to consumers allergic to foods outside the EU’s list of 14 allergens. Some larger businesses also noted that they had begun to pilot this approach.

Public Sector Bodies

This option was the preferred approach for 14% of public sector bodies. Of those who supported option 4, it was noted that this would be the only way the consumer could have full confidence in what they were buying and this was the most consistent approach. The main reason for not supporting option 4 was that it would be onerous for small businesses. A couple of public sector bodies noted the risk of mislabelling and that some businesses may avoid selling PPDS if such legislation comes in.

During the workshops, Local Authorities made a similar point for option 4 as with option 3. In particular they raised the risk of mislabelling in smaller businesses and busy kitchen environments, where there are fewer systems of control in place (see option 3 above). Local Authorities also remarked that option 4 would be harder to enforce and more costly due to the complexity of checking the accuracy of full ingredient labels.

NGOs

This was the preferred option for 13% of NGOs. These organisations felt that full ingredient labelling is the most consistent approach and the safest for consumers.

During the workshop, allergy patient groups and healthcare professions noted that option 4 could lead consumers to wrongly presume, because of broadly similar labels, that PPDS foods are subject to the same level of quality assurance and controls as prepacked food. FSA guidance and public information campaigns were suggested by some participants as ways to mitigate against this.

In a separate workshop in Scotland, attended by food safety trainers, food businesses, charities and enforcement officers, option 4 emerged as the preferred approach overall.

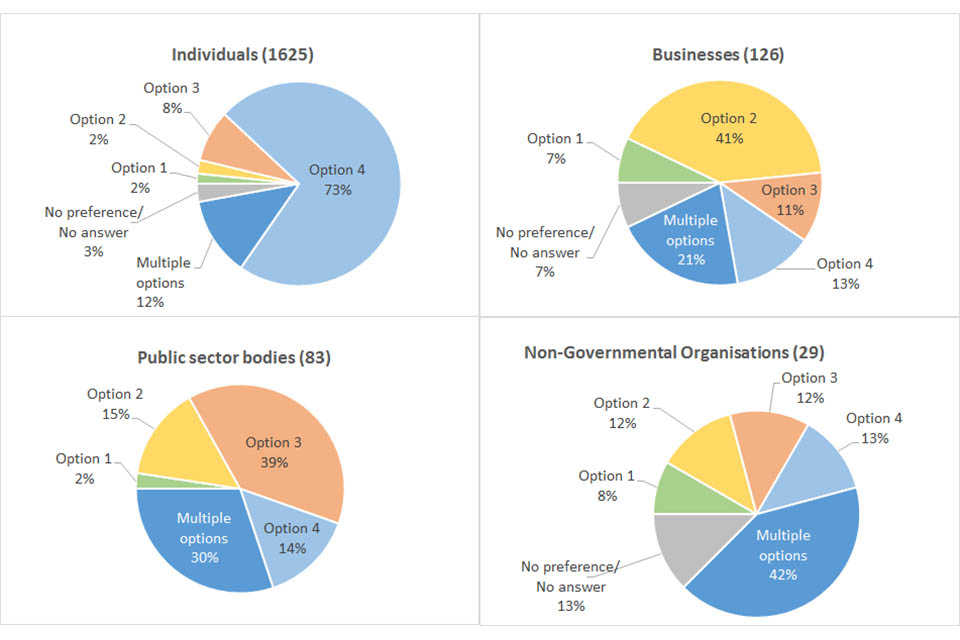

Summary of preferred policy option by group

Below are the breakdowns from the Citizen Space responses of the preferred policy option for the four different stakeholder groups. The number of respondents from that specific group are in brackets.

| Preferred Options | Businesses (126) | Individuals (1625) | Public sector bodies (83) | Non-Governmental Organisations (29) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Option 1 | 7% | 2% | 2% | 8% |

| Option 2 | 41% | 2% | 14% | 13% |

| Option 3 | 11% | 8% | 39% | 13% |

| Option 4 | 13% | 73% | 14% | 13% |

| Multiple options | 21% | 13% | 30% | 42% |

| No preference/ No answer | 7% | 3% | 0% | 13% |

3.3 Business size definitions, exemptions and implementation

We asked respondents whether there should be a two-tiered approach, or exemptions to the policy options and how long an implementation period should run for.

Exemptions

Ninety percent of individual respondents believed that all businesses should be included in all policy options. The main reason given was that customers cannot be expected to be aware of the specific distinctions which exemptions are based on. Around three quarters of NGOs and 80% of public sector bodies also agreed that there should be no exemptions.

Around two thirds of responding businesses also preferred no exemptions.

Across the board, there was little support for small and micro businesses being exempt from options 1 and 2 but greater support for exemptions from options 3 and 4.

The key reasons cited for not including small and micro businesses in options 3 and 4 noted by businesses, public sector bodies and a couple of NGO’s, were the costs and resources required to provide the labels.

In the workshops, large businesses, allergy patient groups and health care professionals noted they wanted no exemptions based on business size because consumers may not be aware of these distinctions and it could create a safety issue. In workshops, individuals and Local Authorities felt that small and micro businesses were the ones with the highest risk and should therefore not be exempted.

Enforcement and implementation

Almost all individual respondents believed that all options should be implemented within a year, if not six months. The main reason cited by individuals for a short implementation period (6 months to 1 year) was that allergic consumers needed to be protected as soon as possible, as a matter of urgency, to prevent more deaths. A number of public sector bodies also noted that short time-scales were required due to the serious consequences for allergy consumers and felt that options 1 and 2 could be implemented in short time frames (6 months to a year).

Businesses and NGOs favoured a longer implementation period, particularly for options 3 and 4. Public sector bodies also believed option 3, and particularly option 4, would take longer, but almost all preferred implementation periods of two years or less. Whilst businesses agreed that options 1 and 2 would be quicker to implement, most felt that a longer time would be needed for options 3 and 4. The main reason being that time would be required to change the way the business operates, put new systems and equipment in place and train staff. Overall, over 50% of businesses indicated than an implementation period of up to 2 years would be sufficient to implement full ingredient labelling. NGOs supported the view that some options would take more time to implement.

In workshops, Local Authorities stressed that implementation time should centrally consider mitigating any risk to consumers, and as part of this, sufficient time for the Food Standards Agency to publish relevant guidance should be given.

4. Government response

4.1 England and Northern Ireland

After careful consideration of consultation responses, advice of the Food Standards Agency and the potential effects each option might have on UK consumers, businesses and local authorities, the Government intends to take forward option 4 in England and Northern Ireland, mandating full ingredient labelling for all PPDS foods. Whilst the change in the law will apply in England and Northern Ireland only, the UK government has been working with the devolved administrations throughout and is committed to pursuing a UK wide approach to protect consumers.

These changes will be made through amendment to ‘The Food Information Regulations 2014’ and parallel FIR regulations in Northern Ireland in summer of 2019, which will come into force two years later, in summer 2021.

The primary reasons for this policy choice are that: the consultation clearly indicated that full ingredient labelling best delivers the interests of consumers with food allergies and intolerances, and at the same time most effectively mitigates the public health risk associated with allergens.

The decision reflected several other key considerations:

- The FSA, the independent government department that led the analysis of the consultation responses, advised Defra to introduce full ingredient labelling with a 2 year implementation period.

- It was the preference of 73% of individuals who responded to the consultation; an important factor in considering which policy best achieves our stated objective of increasing allergic consumers’ confidence in the food they eat.

- Consumers require consistency and clarity. Introducing different labels and approaches to allergens for a particular subset of food which is difficult to differentiate (prepacked and PPDS) risks continued confusion and uncertainty.

- Food allergies have a big impact on quality of life for consumers. For this reason it demands more ambitious measures to address the issues and risks. This opportunity to make improvements, albeit in a small element of the food market, should not be overlooked.

- This is compounded by the additional risk facing younger people, in their teens to early adulthood. This is not usually considered a vulnerable group in food safety terms; but in this instance, where more risky behaviours are part of the normal passage of life, it makes allergy and intolerance risk management a particular challenge.

- There is no cure for food allergies. It demands life-long management. There is no single measure that can remove the risk for a consumer. No combination of measures can eradicate a food allergic consumer’s own duty of care to keep themselves safe.

- Consultation responses from businesses suggested that a longer implementation time would help them adapt their practices, alongside support from local authorities.

- The main concerns raised, chiefly by businesses and local authorities, against option 4 can be reasonably ameliorated through a 2 year implementation period, allowing for: local authorities to familiarise themselves with new legislation and train enforcement officers; and businesses to have the time to put new systems and equipment in place and train staff.

- The FSA will be working with businesses to help them put the necessary checks and controls in place to validate and verify allergen information on packaging. The FSA will also:

a. Create an industry community for food businesses to accelerate sharing of best practice; and improve allergen knowledge and awareness for businesses so that they are aware of their responsibilities.

b. Revise the Safer Food Better Business pack to incorporate management of allergens in small businesses.

FSA guidance will be published alongside the legislation to support businesses and local authorities, and this will be followed up with more detailed guidance before the end of the year. The FSA will be working with businesses and representative organisations during the implementation period to support sharing of allergen initiatives and best practices. Regarding one off events, if you handle, prepare, store and serve food occasionally and on a small scale (e.g. one off cake baking for village fete), you do not need to register as a food business, and you are not bound by these rules.

4.2 Scotland

After careful consideration of consultation responses, advice from Food Standards Scotland and the potential effects each option might have on Scottish consumers, businesses and local authorities, the Scottish Government intends to take forward option 4 in Scotland, mandating full ingredient labelling for all PPDS foods. The Scottish Government is committed to close working with the UK government and Welsh Government on a common approach across the UK.

The Scottish Government has asked Food Standards Scotland to undertake further work to fully assess the benefits, impacts, risks, and enforcement approaches to determine how full ingredients listing can be achieved accurately and in ways that will provide the greater certainty that consumers seek. This will require detailed discussions with stakeholders to understand fully any technical and regulatory compliance challenges that some businesses may face. Scottish Ministers also want to consider piloting implementation, and allow time to develop robust guidance and training to support any regulatory change.

The Scottish Government aims to implement any new legal obligations by autumn 2021.

4.3 Wales

Ministers in Wales are currently reviewing the evidence gathered through the consultation, and advice from the Food Standards Agency, and intend to make a decision shortly.

5. Annex A - Allergenic foods

There are 14 substances or products causing allergies or intolerances which (unless exempted[footnote 2]) are legally considered to be mandatory information for consumers under FIC. This requirement is extended to all foods provided to consumers and includes food that is:

- prepacked (e.g. a bar of chocolate, a sealed packet of crisps, a jar of sauce or a can of soup)

- not prepacked (e.g. restaurant meals)

- packed at the consumer’s request (e.g. a deli sandwich prepared, wrapped and handed to the customer)

- prepacked for direct sale (PPDS; e.g. a sandwich prepared by staff on the premises and prepacked before the customer chooses it)

If a food product contains or uses an ingredient or processing aid derived from one of the substances or products listed below, it will need to be declared by the Food Business Operator to the consumer on the packaging for prepacked foods, or, for non-prepacked foods in the UK, by any means the Food Business Operator chooses, including orally by a member of staff:

- Cereals containing gluten, namely: wheat (such as spelt and khorasan wheat), rye, barley, oats and their hybridised strains and products thereof

- Crustaceans and products thereof

- Eggs and products thereof

- Fish and products thereof

- Peanuts and products thereof

- Soybeans and products thereof

- Milk and products thereof (including lactose)

- Nuts, namely: almonds, hazelnuts, walnuts, cashews, pecan nuts, Brazil nuts, pistachio nuts, macadamia or Queensland nuts, and products thereof

- Celery and products thereof

- Mustard and products thereof

- Sesame seeds and products thereof

- Sulphur dioxide and sulphites >10mg/kg or 10mg/L

- Lupin and products thereof

- Molluscs and products thereof

This list is consistent across the EU and cannot be amended by individual Member States.

-

www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-allergen-labelling-technical-guidance.pdf ↩

-

Some ingredients made from the allergens listed above will not cause an allergic reaction because they have been highly processed (for example fully refined soya oil or wheat glucose syrups). This is because the allergen/protein has been removed and the product has been assessed by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) as not possessing an allergenic risk to the consumer. A full list of exemptions is available at Annex II of FIC. ↩