Improving broadband for Very Hard to Reach Premises: Government response

Updated 25 May 2022

1. Ministerial foreword

The government is committed to making the UK a global leader in digital connectivity. Levelling up means ensuring that reliable, long-lasting gigabit-capable connections are made widely available across the UK.

It is now more important than ever to have resilient telecoms networks in place. During the last 18 months, digital connectivity has been imperative, allowing millions to work from their homes, providing information and entertainment to those isolating and allowing education to continue while schools, colleges, and universities were closed.

I am proud of the work done so far by the telecoms industry, supported by the government and Ofcom, which has already delivered gigabit-capable broadband to over 65.8% of premises in the UK, including more than half a million homes and businesses in hard to reach areas. However, there is a lot more still to be done.

Our rural communities need good digital connectivity to prosper in an increasingly connected world, and we are committed to ensuring that no part of the UK is left behind. By definition, it is going to be much more difficult to deliver gigabit connectivity to the hardest to reach parts of the UK - around 20% of UK premises - and that is why we have committed a record £5 billion of capital funding to support deployment in these areas.

I am keen that decisions about better broadband are based on evidence from those who will be most affected by them. Detailed information about the demand for broadband services, their invaluable benefits, barriers to deployment and take-up is crucial. We also need evidence from suppliers and vendors on technology availability, maturity, capabilities and costs to provide connectivity in Very Hard to Reach areas, both in the UK and overseas.

I would like to thank everyone who submitted a response to this call for evidence. This will be used to inform the future policy decision making of the experiences of those facing limited connectivity so that we do not see a digital divide emerge.

Julia Lopez

Minister for Media, Data, and Digital Infrastructure

2. Executive summary

Context

The government has ambitious plans to achieve a nationwide rollout of future-proof, gigabit-capable broadband and 5G networks as soon as possible to unlock the huge economic and social benefits that this will bring. As we emerge from the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, ensuring the whole country has access to world-class digital infrastructure will be critical to our economic recovery. DCMS continues to work with the industry to target a minimum of 85% gigabit-capable coverage by 2025 and to get as close to 100% as possible. We have launched our £5 billion ‘Project Gigabit’ programme to ensure premises in hard-to-reach areas are not left behind in being able to access gigabit-capable networks. We have already announced which areas will benefit from the first 2 phases of this record investment, and we will continue to update our procurement pipeline on a quarterly basis.

We are aiming to ensure that 95% of the UK’s geographic landmass has 4G coverage from at least one mobile network operator by 2025 and that the majority of the UK population has 5G coverage by 2027. We are already taking steps to deliver this and through our Wireless Infrastructure Strategy we will set out a long-term strategic policy framework for the development, deployment and adoption of 5G and future networks in the UK. However, while the government is making significant progress in delivering improved connectivity to the country, we know that in some areas the cost of delivering gigabit-capable broadband coverage rises exponentially. We are therefore likely to need to consider alternative options to connect some premises, initially estimated to be less than 100,000 in total, which are deemed ‘Very Hard to Reach’.

To do this, we needed to better understand and explore all possible options for improving broadband connectivity for these Very Hard to Reach premises. The purpose of this call for evidence was to develop our understanding of these areas and seek more information on:

-

Demand

-

Benefits

-

Barriers

-

Approaches

The call for evidence set out the current broadband programmes being offered by the government as well the rationale for undertaking the call for evidence as a means of understanding the requirements of prohibitively expensive premises and the range of technology approaches available. The responses that we have received from the consultation have been used to inform our response and will help to inform our policy proposals for improving broadband in Very Hard to Reach areas in the future.

The call for evidence

The call for evidence ran between 15 March and 25 June 2021 and sought stakeholders views in the following 3 areas:

-

Demand

-

Benefits

-

Barriers

The call for evidence also exclusively sought the views of Market Participants in the following area:

- Approaches

Resident household and business users of rural broadband were invited to submit their responses through an online survey. Market participants and organisations representing relevant stakeholders were invited to participate either through the survey or by providing a long-form response.

The majority of responses were received through the online survey. Therefore. answers have been collated to form a more detailed understanding of the issues that affect respondents’ rural connectivity. Responses received as a long-form submission often linked their answers to the overarching subject matter rather than per the specific question asked. Therefore, this document has been structured in a similar manner, taking into account both the survey responses and the long-form submissions to reflect the information provided.

A significant proportion of the responses provided by representative organisations made reference to Project Gigabit. This was either regarding the procurements that are ongoing or the Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme that is available to some premises.

As highlighted in the call for evidence, the focus of this document was on premises that are primarily Very Hard to Reach because of their geographic location. Therefore, premises that are due to be covered by a government-funded rollout such as the Superfast Broadband Programme or expected to be delivered by Project Gigabit will not be classified as Very Hard to Reach.

In addition, we recognise that some premises may not be geographically Very Hard to Reach but may have a high cost to upgrade and/or serve due to low economies of scale. This could be because of previous network deployment strategies or legacy services.

However, while we understand that premises such as these exist, they are not the focus of this call for evidence.

Government response

All responses to the call for evidence have been recorded and analysed. This document outlines the key points made, drawing out the common themes that have emerged and the most frequently expressed points of view.

Based on the evidence gathered during the call for evidence, the government will produce a set of policy proposals in due course that will set out how we expect the market in these areas to develop and what further actions might need to be taken to address the needs of these premises.

The government’s response is discussed in more detail at the end of this document.

3. Overview

The UK government’s ambition is to deliver nationwide gigabit-capable broadband as soon as possible. We have set a clear strategy through the Future Telecoms Infrastructure Review, Statement of Strategic Priorities, and the planned, record £5 billion investment into Project Gigabit. In the period to 2025, we are targeting a minimum of 85% gigabit-capable coverage but are working with the industry to accelerate delivery to get as close to 100% as possible.

To support private sector deployment in the most commercial 80% of the UK, the government will continue to implement an ambitious programme of work to encourage investment in gigabit-capable broadband and remove barriers to rollout. Delivering gigabit-capable broadband in the hardest to reach 20% of the UK is more challenging, which is why the government has set out plans to support the delivery of gigabit-capable connectivity to these areas through Project Gigabit.

This programme builds on the previous programmes that the government has established to improve broadband in less well-served areas. For example, the £1.9 billion Superfast Broadband programme has delivered superfast broadband speeds to over 5.5 million UK premises (approaching 20% of the UK). Through public and private sector investment, superfast broadband is now available to 97% of UK premises[footnote 1] and the UK has one of the highest rates of superfast coverage in Europe, including in rural areas.

The Superfast Broadband Programme is continuing alongside Project Gigabit, and it is now mainly delivering full-fibre broadband to the 3% of UK premises that do not yet have access to superfast speeds. Before the launch of Project Gigabit, the government also rolled out other programmes such as the Local Full Fibre Networks programme and Rural Gigabit Connectivity programme to stimulate gigabit broadband rollout, including in more rural and remote areas.

Through the broadband Universal Service Obligation (USO), the government has legislated to provide every household with a ‘backstop’ legal right to request a decent broadband connection, providing a minimum download speed of 10 Mbps and an upload speed of 1 Mbps. The broadband USO is funded by the telecoms industry and is subject to a cost threshold of £3,400 per premise. Consumers are required to pay the excess costs of connection above this threshold.

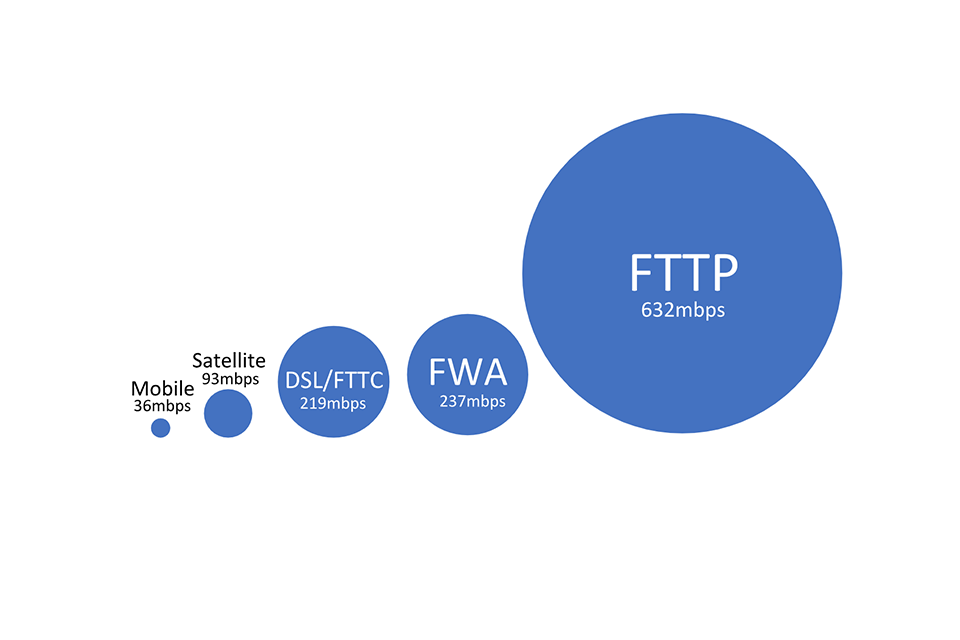

Since this legislation was enacted in the Digital Economy Act 2017, the number of premises that cannot get a broadband service that meets the minimum specification under the USO has fallen from 1.1 million premises to 123,000 premises as of May 2021.[footnote 2] This is due in part to the government’s Superfast Broadband programme but also significant improvements in 4G network coverage and wider availability of Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) services. Our £5 billion Project Gigabit will also prioritise premises without access to superfast broadband speeds, wherever possible.

We expect that the number of premises that cannot get a USO level service will continue to reduce over time as a result of further government investment in broadband, including through the £5 billion Project Gigabit, as well as further improvements in wireless networks from additional spectrum and masts, and the USO itself.

In October 2021, BT stated that they had already built USO connections that covered over 3,700 homes and were in the process of building over 2,500 more across the UK.[footnote 3] The vast majority of these premises are being upgraded to a gigabit-capable full-fibre connection compared to the minimum download speed of 10 Mbps under the USO. BT’s next report is due by 30 April 2022 and we expect that thousands more premises will be benefiting from the USO by that point.

However, the costs of delivering gigabit-capable broadband coverage rise exponentially as deployment continues to the most remote premises. A very small proportion of premises - potentially less than 100,000 - are therefore likely to be significantly above the broadband USO’s reasonable cost threshold and considered ‘Very Hard to Reach’ with gigabit-capable broadband technologies like fibre to the premises technology. This is due to factors like their isolated geographic locations or the often substantial distances between them and existing or planned telecoms infrastructure, which make it challenging to deliver improved broadband.

The purpose of this call for evidence, therefore, was to develop our understanding of these areas and seek more information on:

- Demand: Consumer and business demand for broadband services in Very Hard to Reach areas. In particular, we were seeking information on current provision and adoption patterns by consumers and businesses in these areas, including businesses in the agricultural sector.

- Benefits: Further evidence on the benefits that delivering enhanced broadband services to Very Hard to Reach areas yields, including social, environmental or economic benefits.

- Barriers: Evidence of barriers to user adoption (other than services being unavailable in an area), and evidence relating to barriers that may impede infrastructure operators and service providers from offering improved broadband services in these areas. This evidence could also relate to barriers to investment (for parties providing finance for such investments).

- Approaches: Evidence relating to the availability, maturity, capabilities and costs of advanced technologies and novel approaches to provide connectivity in Very Hard to Reach areas, either within the UK or from overseas.

We asked for evidence from 4 types of stakeholders:

- Consumers of broadband services, in particular those who are resident in remote rural parts of the UK and cannot access broadband speeds that meet the minimum specification under the broadband USO.

- Business users of broadband services in these areas, including those working in the agricultural sector.

- Market participants, including infrastructure suppliers/operators, retail or independent broadband service providers, mobile network operators and equipment vendors.

- Representative organisations, who may for example be representing rural stakeholders, consumer groups or any sub-groups of the stakeholders listed above. This group could also include local government bodies and rural enterprise partnerships.

4. Responses

The call for evidence received responses from residential households, businesses, market participants and representative organisations representing consumers, small businesses, farmers and crofters, as well as local councils.

The call for evidence asked for information on 4 themes to develop our understanding of these areas and seek more information concerning delivering improved connectivity to Very Hard to Reach premises. A series of questions were asked on each of the following areas:

The specific questions asked can be found in Annex A.

Most of the responses linked their answers to the overall theme rather than a specific question being asked, providing a more detailed view of the wider policy area. This document, therefore, responds similarly, reflecting each theme individually rather than addressing each question in turn.

We received 3315 responses to the call for evidence, including 67 from market participants and organisations representing them. Due to some age groups (Figure 4.2) and regions (Figure 4.5) being overrepresented in the survey, consumer and business responses were weighted by age group and regions to make the results more representative. The supplier data, however, is unweighted. The weights have been estimated based on ONS population data and NSPL premises level data. All data and charts have used the weighted data unless otherwise stated.

Figure 4.1: Responses to the call for evidence survey per Nation (unweighted)

Figure 4.2: Our consumer response sample is skewed towards older age groups (unweighted data).

| Age bracket | Percentage of respondents |

|---|---|

| 18 - 34 | 10% |

| 35 - 44 | 15% |

| 45 - 54 | 23% |

| 55 - 64 | 26% |

| 65+ | 25% |

Question: How old are you? N = 2096

As shown in Figure 4.3, the majority of businesses are 10 years old or older. This echoes that the majority of our respondents are older as seen in the chart above (Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.3: The majority of businesses in our sample have been operating for more than 10 years (unweighted data).

| Age of business | Percentage of businesses |

|---|---|

| Less than 2 years | 5% |

| 2 - 5 years | 14% |

| 6 - 10 years | 12% |

| 11 - 20 years | 24% |

| 21+ years | 45% |

Question: How long has your firm been in operation? N = 469

Figure 4.4 shows the rurality of respondents, using 2 measures. The first is the count of responses to the question posed. The second uses respondents’ postcodes and matches them to National Statistics Postcode Lookup data (NSPL)[footnote 4]. There is a slight discrepancy between the 2 estimates as there are some postcodes from the call for evidence that do not match with the NSPL data. The results show a broader spread, and that some respondents declaring themselves rural are actually in suburban or remote areas, by NSPL definitions.

Figure 4.4: Self-declared and NSPL rurality of respondents (unweighted data).

| Rurality category | Self-declared | NSPL estimated |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | 2% (68) | 1% (36) |

| Suburban | 5% (137) | 8% (220) |

| Rural | 80% (2369) | 71% (2054) |

| Remote | 13% (390) | 20% (578) |

| Unsure | 1% (35) | N/A |

Questions: How would you describe the area you live? NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?). N = 2964 and 2888 respectively.

Figure 4.5 shows that the majority of responses were in the East Midlands, the South West and Scotland. This is partly due to some postcode outliers within these regions, such as Leicestershire and Shetland more specifically, which had very high levels of responses. Additionally, the Warwickshire town of Southam also had a disproportionately high response rate. Conversely, only 9 responses were received from London based postcodes.

Figure 4.5: Our consumer sample is skewed towards the East Midlands, South West and Scotland (unweighted data).

| Region | Percentage of respondents |

|---|---|

| East Midlands | 17% |

| South West | 17% |

| Scotland | 12% |

| West Midlands | 11% |

| South East | 9% |

| North West | 8% |

| Wales | 6% |

| North East | 6% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 6% |

| East of England | 5% |

| Northern Ireland | 2% |

Question: Which part of the UK are you from? N = 2999

Long-form responses to the call for evidence suggested that the majority of rural businesses in our sample are micro and SME family businesses. Businesses that responded to the call for evidence were predominantly in the agriculture and tourism industries (Figure 4.6).

Figure 4.6: Our business sample is mostly made up of agriculture and construction/transport firms (unweighted data).

| Industry | Call for evidence | ONS rural businesses |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | 34% | 28% |

| Construction/Transport | 30% | 18% |

| Accommodation/Food | 11% | 5% |

| Wholesale/Retail | 5% | 10% |

| Public Administration | 4% | 7% |

| Post/Telecomms | 1% | 2% |

Question: What is the main sector that your firm operates in? N = 486 & ONS rural business data[footnote 5]

The non-nationwide providers in our sample are mostly operating outside of London and the South East (Figure 4.7).

Figure 4.7: The majority of responses from non-nationwide market participants came from Scotland, the South West and the North of England (unweighted data).

| Region | Percentage of Providers |

|---|---|

| Scotland | 39% |

| North East | 22% |

| North West | 22% |

| South West | 22% |

| East of England | 17% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 17% |

| East Midlands | 13% |

| South East | 13% |

| London | 4% |

Question: Which region of the country do you operate in? N = 238

5. Topic A: Demand

The questions asked in this section can be found in Annex A.

Context

As outlined in the call for evidence we need to understand in more detail the needs of communities and businesses located in Very Hard to Reach locations and how they expect their needs and requirements to change over time.

This is because currently available evidence on demand for broadband services is often affected by measurement techniques or the substantial aggregation of data. Having an understanding of the needs of the consumer both now, and in the future, will allow us to optimise future policy in a more geographically specific manner, tailored to the needs of these areas.

The most up to date evidence, as detailed in the call for evidence, is from before the COVID-19 pandemic and showed that consumers in remote and rural areas are already more likely to work from home. It also showed that there are proportionately more registered businesses in remote rural areas than in any other rurality type.

The most abundant business types registered in rural areas are ‘agriculture’ (28%), construction & transport (18%), wholesale/retail (10%), public administration/social security (7%), and hospitality (5%) as in Figure 4.5.

We heard

Rural and remote areas have slower speeds than urban areas despite having similar broadband needs.

Consumer and business responses from the call for evidence showed that a significant majority of premises in remote and rural areas experience slower broadband speeds than those located in urban areas.

Figure 5.1 estimates the average speeds of consumer respondents split by their rurality. The consumers who live in postcodes classified as remote are more likely to have slower speeds at a postcode level than those in rural or urban and suburban postcodes.

Figure 5.1: Respondents in remote areas had lower average download speeds than more urban postcodes.

| Rurality of Respondent | Up to 10 Mbps | 11 - 24 Mbps | 25 - 100 Mbps | 100 - 300 Mbps | 300+ Mbps | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban & Suburban | 14% | 5% | 15% | 51% | 14% | 100% |

| Rural | 28% | 21% | 11% | 36% | 4% | 100% |

| Remote | 65% | 8% | 11% | 15% | 1% | 100% |

Questions: NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?). Connected Nations Postcode Average Speed based on postcode (What is your postcode?). N = 1725

The majority of respondents who live in remote areas are estimated to have broadband speeds below 10 Mbps. While some of these premises are likely to be eligible for the broadband Universal Service Obligation (USO), many will also be able to access a faster speed through either a forthcoming government scheme or by accessing a Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) service.

We learned from many long-form responses that in remote and rural areas in the UK, there is a strong demand for good connectivity. Generally, those living and working in rural areas want to see an improvement in their broadband service. In addition, it was noted that there was greater demand for improved broadband speeds and reliability amongst residents with the slowest connectivity.

As part of its response, the Independent Networks Cooperative Association (INCA) provided data showing that:

- 16% of rural premises currently have a download speed of <10 Mbps which INCA describes as ‘completely inadequate broadband and therefore have an urgent need for a better connection to avoid complete digital exclusion’

- a further 15% (total 31%) have ‘an immediate need to improve broadband to meet current expectations’

- final 50% (total 81%) would ‘need to upgrade by approximately 2025 to keep up with changing requirements’

Ofcom estimated[footnote 6] that as of May 2021, 123,000 premises were potentially eligible for a broadband Universal Service Obligation connection as they did not have access to a decent broadband service from a fixed network or a Fixed Wireless Access (FWA) network. Ofcom stated that 120,397[footnote 7] of these premises are located in areas designated as ‘Rural’. Therefore, while some premises identified by both the INCA report and the call for evidence survey may have a connection of less than 10 Mbps, overall, only approximately c.2.7% of premises in rural areas[footnote 8] are unable to access a decent broadband connection.

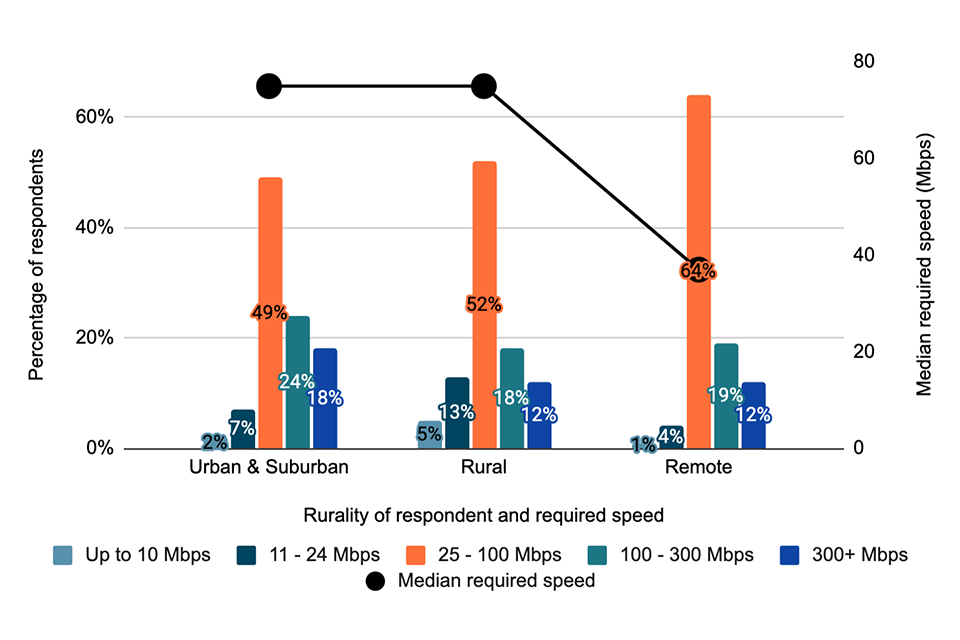

Figure 5.2 below shows that across ruralities, the most common speeds required are between 25 - 100 Mbps. Furthermore, within ruralities, the median required speed is mostly consistent at 75 Mbps for Rural, and Urban and Suburban, only dropping to 37 Mbps in remote areas.

Figure 5.2: Respondents required similar speeds across ruralities.

Chart shows similar requirements across ruralities.

Questions: What broadband download speed do you think you currently require? To clarify, this is the speed which meets your needs, this may or may not differ to the speed you currently purchase. NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?). N = 1569

Representative organisations including Cumbria County Council and the Federation of Small Businesses in response to the call for evidence noted that a reliable connection delivering 10 Mbps was more important than a faster connection. The NALC, among others (noted below) also highlighted that councils stated residents’ needs were for speeds between 40 and 100 Mbps.

The Agricultural Productivity Task Force’s (APTF) long-form response said: ‘Approaches need to be varied and suited to the particular location and need of the businesses, with a priority of connecting with a decent speed now instead of making farms wait for gigabit speeds for many years, while they remain less productive.’

West Sussex County Council said in its long-form response: ‘It is evident that many rural businesses and premises require faster connections, but not necessarily gigabit-capable solutions’ and ‘It is felt that the requirement for gigabit-capability in the full end to end solution could [increase] the cost unnecessarily, when there are alternative opportunities for low cost, very quick improvements to rural connection speeds, which would be a dramatic improvement for the consumer and meet their urgent needs.’

The NFU (National Farmers Union) is calling for a ‘wider application of alternative broadband solutions for these very hard to reach areas as we feel that delivering broadband of good-to-average speeds immediately is the first priority.’

In its response, the National Association of Local Councils (NALC) said that ‘typically councils stated that their residents needed speeds of between 40 Mbps and ultra-fast 100 Mbps’.

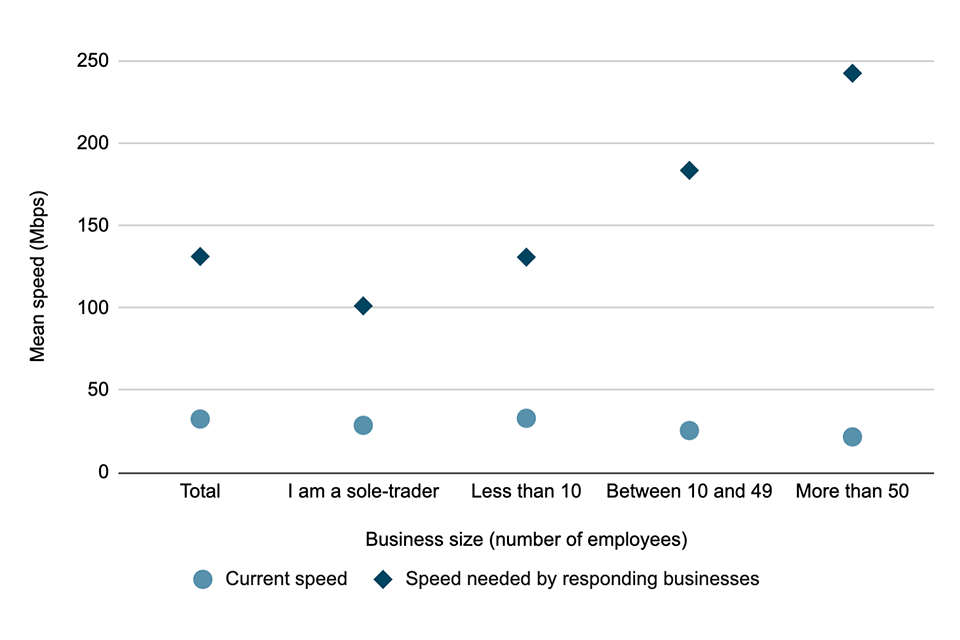

The survey results identified that rural and remote businesses reported needing speeds well above what they receive and that larger businesses saw a wider disparity than smaller ones Figure 5.3. Businesses often identified the use of video conferencing with customers or suppliers as the aspect of their business operations for which current speeds are insufficient.

Figure 5.3: Almost all respondents reported that they needed a greater download speed for their business than their current highest advertised speed.

Almost all respondents reported that they needed a greater download speed for their business than their current highest advertised speed.

Questions: What broadband download speed do you think is currently required for your business? Vs What is your maximum advertised download speed (according to your supplier)? N = 266

We heard that currently, to get a connection suitable for their needs, some residents must travel to alternative locations to complete online activities. The Farmers’ Union of Wales (FUW) stated that it wasn’t ‘uncommon for FUW members to have to walk or drive to a certain hot spot in order to obtain mobile phone signal and/or internet coverage.’

The department has also received correspondence from members of the public which expresses frustration at this issue, with one correspondent explaining their frustration at not being able to work from home due to poor connections and instead having to go into their workplace as a key worker despite also being considered as someone who should shield from COVID-19.

Anecdotal evidence was given, to suggest that during the COVID-19 pandemic, children attended online lessons from cars after parents had driven them to a place with a suitable connection. Online schooling during this time was difficult for those living in rural areas due to poor broadband with the NALC reporting that some pupils were forced to attend school by exception to continue their education.

The majority of respondents reported that they are unhappy with their current service citing unreliable services and poor speeds. In long-form responses, anecdotal evidence was given of difficulties including an example of some residents finding it takes over 2 hours to do an online grocery shop because they have lost signal multiple times.

Figure 5.4 shows remote and rural consumers in our survey tended to be less satisfied with most aspects of their broadband compared with urban/suburban consumers.

The most remote consumers have lower satisfaction with both reliability and pricing. Comparing this to survey work by Which?,[footnote 9] we observe price and reliability also being the most complained about the issue.

Figure 5.4: Rural and remote consumers tend to be less satisfied than urban/suburban.

| Average satisfaction | Urban & Suburban | Rural | Remote | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speeds | 2.1 | 2 | 1.8 | 2 |

| Reliability | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 2.4 |

| Customer service | 2.9 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Price | 2.8 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.6 |

| Usage restrictions | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.8 | 3 |

Questions: NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?). Please rate your satisfaction with the following aspects of broadband service: Speed, Reliability, Customer Service, Price, Usage Restrictions, Overall. N = 1661 - 1677. 1 = Lowest Satisfaction, 5 = Highest Satisfaction

Ofcom, as part of its Customer Satisfaction Tracker, estimated that 87% of consumers were satisfied with their internet service[footnote 10] with a further 8% dissatisfied. Compared to our analysis, we observed very polarising results, with 56% of respondents answering as dissatisfied and 18% as satisfied (25% answered as neutral). Ofcom’s estimate is a nationwide average and is not split by rurality, which may explain the difference and suggest that rural/remote respondents may generally be less satisfied.

We also heard in long-form responses from representative organisations that there is a significant proportion of premises in rural areas that are dissatisfied with their current broadband service due to unreliability. The Federation of Small Businesses (FSB) said in its response to the call for evidence that a ‘Lack of reliability is a key issue for small businesses and often more important than speed itself.’ This was reportedly an issue for both fixed broadband and wireless services.

We heard that some rural businesses, employees, and rural residents have to drive to hotspots to access and use online services such as email, accounting, and video conferencing. During the COVID-19 pandemic, some people reported working outside friends’ houses in their cars so they could follow government COVID-19 restrictions and have access to a suitable broadband connection. Others stated that they have had to incur additional costs to rent an alternative office space that has a broadband connection suitable for their business needs.

Generally, most individuals who responded to our call for evidence stated that they own a smartphone and possess multiple devices. However, the Action for Communities in Rural England stated in the call for evidence response provided by the Communications Consumer Panel & Advisory Committee for Older and Disabled people (ACOD) that some younger respondents have been reported to find it difficult only having a smartphone to access online services which can make accessing work, education and opportunities harder.

Figure 5.5 shows that younger demographics are more inclined to use mobile phones as well as video and music streaming services[footnote 11], and conversely, those aged 65 and over are more inclined to use landline phones[footnote 12]. Ofcom data[footnote 13] shows total mobile phone use is in the range 97%-98% for all age groups except for those above the age of 65 where it is instead 84%. Pay-TV access was surprisingly lower in elderly groups in our survey, but this may be due to confusion around the difference between Pay-TV and video streaming.[footnote 14]

Figure 5.5: Respondents who are aged 65+ tended to have lower access to music and video streaming services.

| Businesses | 18 - 44 | 45 - 64 | 65+ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile/smartphone | 97% | 96% | 87% |

| Home broadband | 86% | 94% | 93% |

| Landline telephone | 70 % | 86% | 92% |

| Pay TV | 66% | 68% | 51% |

| Video streaming | 91% | 76% | 51% |

| Music streaming | 78% | 64% | 23% |

Questions: How old are you? Which of the following services do you have access to? N = 1897

Figure 5.6 shows that all households tend to make use of multiple devices that connect to the internet regardless of rurality, which will be driving increased demand for better broadband.

Figure 5.6 All households use multiple devices that connect to the internet.

| Device/service | Rural | Remote |

|---|---|---|

| Mobile/smart phone | 97% | 96% |

| Tablet | 84% | 81% |

| Laptop | 89% | 89% |

| Desktop computer | 59% | 44% |

| TV set that connects to the internet | 84% | 81% |

| Games console | 38% | 32% |

| Personal Wi-Fi hotspot device (e.g. Mi-Fi) | 17% | 11% |

| Server computer | 8% | 3% |

| Connected home products (e.g. smart meter) | 59% | 37% |

Questions: NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?). Which of these devices do you own? N = 2097

We also heard in the long-form response from Lancaster University Management School that ‘those with good connectivity through broadband also tend to own smart TVs and gaming equipment, and some had digital home security devices.’ The adoption of connected devices varies on the speed available to the premises.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for improved connectivity in rural and remote areas.

There was agreement among respondents that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the need for improved connectivity in rural and remote areas for consumers and businesses. In its response to the call for evidence, the FSB said that digital connectivity ‘will be vital in the post-covid recovery.’

Market participants also reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted consumption patterns amongst consumers and brought forward a large rise in bandwidth use.

All respondents agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the need for digital connectivity and that people were reliant on their broadband connections for working from home, shopping, entertainment, and socialising. Video conferencing platforms were used more and Lancaster University found that these platforms were used for social interactions that before the COVID-19 pandemic were not usually online such as book clubs, the Women’s Institute, online bell ringing, and virtual conferences.

The Farmers’ Union of Wales (FUW) said that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the rural-urban divide as large numbers of rural children were unable to access online classes and online learning platforms following the closure of schools. The National Farmers’ Union Scotland (NFUS) also noted during the COVID-19 pandemic a widening of the rural-urban divide, stating that farming and crofting communities were at a greater disadvantage than urban areas.

There was a consensus among the respondents that those with poor broadband access particularly struggled through the COVID-19 pandemic and were left in vulnerable circumstances. They had difficulties ordering supplies online and could not get them from physical shops as they were shut due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Cairngorms National Park Authority believe there is a need for improved broadband connections in remote-rural areas for education and healthcare.

The response from Communications Consumer Panel and Advisory Committee for Older and Disabled people (ACOD) said: ‘We understand from d/Deaf stakeholders that consumers using text and video relay, and speech-to-text services in rural areas (or connecting with others who are in rural areas) during the [COVID-19] pandemic, have found it difficult to participate fully, due to connectivity issues affecting the speed and delivery of the captions and images they rely on.’

Caithness Chamber of Commerce highlighted how the Scottish and UK governments appear to be encouraging hybrid working for the foreseeable future means that increased broadband consumption patterns will become the norm.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, satellite provider Viasat noted that customers had increasingly migrated from entry-level speed (ViaSat-1 offered 12 Mbps) and data packages to the highest level offerings (ViaSat-2 offered 50 to 100 Mbps) during the COVID-19 pandemic. This, Viasat noted, was largely due to the need for more telework, telemedicine and remote learning.

Quickline presented that data consumption had continued to grow ‘exponentially’ in recent years and that they expected this to continue for the ‘foreseeable future’ ultimately leading to an ongoing increase in the bandwidth requirement of around 30% per year. However, one change, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, has been an increase in demand during the ‘busy hour’, with it now a ‘busy period’.

Other respondents also agreed with Quickline’s findings that changes because of the COVID-19 pandemic would increase data consumption including a pattern of increased use surrounding the ‘busy hour’ creating a broader peak. Video streaming is likely to be driving the demand alongside an increase in working from home which respondents expect to continue.

Businesses

According to research carried out by FSB in 2019,[footnote 15] 47% of rural businesses use an ADSL connection while just 11% use an FTTP (Fibre to the Premises) connection. 37% of the 1,500 locations that Historic Houses represent say they have access to reliable 4G and fibre optic broadband.

Representative organisations with an agricultural focus said that FTTC (Fibre to the Cabinet) is the dominant connection for their members, but a high proportion are reliant on mobile connections, and 4G dongles are frequently adopted.

APTF and NFU noted that they believe ‘Total mobile coverage and gigabit-capable broadband access for farming businesses is essential if the industry is to be able to respond to the changes in agricultural policy, consumer/market demands for more sustainable and ethical production and remain profitable.’

Mobile coverage

Some respondents noted that residents of rural areas can sometimes experience a lack of wireless signal and be located in mobile not-spots.

Respondents have reported disparity between 4G coverage, meaning that some large areas do not have sufficient coverage to access the internet with a mobile device. NFU reported that 7% of respondents to its annual survey reported no reception at all, and therefore, they deem that the current mobile network is insufficient for the needs of its community.

Ofcom (2020)[footnote 16] estimated that 100% of urban premises have indoor 4G coverage from at least one mobile network operator. This is based on figures provided by Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) to Ofcom. This drops a little in rural areas to 95% indoor 4G coverage. This is not borne out in our data, with Figure 5.7 showing only 59% and 45% indoor coverage in rural and remote areas, respectively.

This discrepancy in mobile coverage compared to Ofcom estimates is partly a reflection of how rural some respondents are, however it may also be due to respondents only answering based on their current provider’s coverage as opposed to all 4 mobile network operators.

Figure 5.7: A large number of respondents in remote areas reported no mobile coverage.

| Percentage of respondents | No mobile coverage | 2G & 3G | 4G & 5G |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urban & suburban | 5% | 15% | 75% |

| Rural | 16% | 20% | 59% |

| Remote | 31% | 20% | 45% |

Questions: Do you have a 2G, 3G, 4G or 5G mobile service at your household? NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?) N = 1822

In its long-form response, NFUS reported ‘The 2021 NFUS member survey revealed 48% of respondents described the quality of their mobile signal in their home and office as “poor” or “very poor”, 25% “acceptable”, and 26% “good” or “very good”. Similar experiences were reported for mobile signal quality on and around farms.’

Similarly, in our call for evidence business survey (of which most respondents were either rural (78%) or remote (18%)), we heard that only 18% of respondents had coverage that worked well indoors and out. Most of the remaining respondents said they had partial workplace coverage (Figure 5.9).

Figure 5.8: The majority of businesses experienced limited mobile coverage.

Question: What is mobile coverage like inside your workplace? N = 336

Respondents to the call for evidence commented that the government’s current broadband schemes, including both the broadband USO and the government’s Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme, needed to be amended to meet demand from both businesses and consumers.

Historic Houses noted in its response that the broadband USO should be increased to a minimum download speed of 20 Mbps and an upload speed of 2 Mbps. The CLA and the Countryside Alliance also called for a 2 Mbps upload speed to be the USO requirement. In addition, Historic Houses stated that they believed that there should be more assistance from the government to enable community broadband schemes.

Cairngorms National Park Authority said that after 2 years of work, nothing came out of the community scheme developed by Community Broadband Scotland, as the solutions were to be provided centrally via the Scottish Government’s Reaching 100 (R100) Superfast rollout programme.

Only 12% of businesses said they had applied for a broadband connectivity voucher, and of those, only 18% (2.5% in total) have so far received a better connection. Figure 5.10 shows that most were awaiting their connection and Gigabit vouchers and the Superfast Broadband Programme were the slightly more popular schemes. Only one business mentioned the broadband USO.

Figure 5.9: Most businesses did not use or receive a better connection from voucher schemes

| Voucher | Awaiting | Scheme did not proceed | Received a better connection | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gigabit voucher | 15 | 14 | 4 | 33 |

| Superfast scheme | 6 | 7 | 3 | 16 |

| Better broadband | 8 | 10 | 2 | 20 |

| Local authority scheme | 7 | 8 | 1 | 16 |

| Other | 3 | 5 | 3 | 11 |

Question: You stated that you have applied for a broadband connectivity voucher. Please tick all the vouchers which you applied for and which stage of the application you are at. N = 56. N.b. Some businesses applied for more than one scheme therefore these totals do not add up to the N above

Figure 5.10 shows that of businesses that had not applied for vouchers, only one in 3 knew where they could find more information.

Figure 5.10: Most of the respondents were unaware of where to find information on vouchers

| Yes - I’m aware | No - I’m unaware |

|---|---|

| 30.2% | 69.8% |

Question: You haven’t applied for a broadband connectivity voucher. Are you aware of where to find information on these vouchers in your area? N = 349

6. Topic B: Benefits

The questions asked in this section can be found in Annex Annex A.

Context

Despite having evidence from both previous and ongoing government schemes, the call for evidence looked to further quantify the social, environmental and economic benefits of improved connectivity for communities who are located in Very Hard to Reach Areas.

Additional evidence is required as previous academic and social research has primarily focused on rural areas, rather than remote rural premises which make up the vast majority of Very Hard to Reach Areas.

New technologies including agri-tech and other rural digital communication platforms also require further research on their benefits given how relatively recently they have been introduced.

The evidence that we can compile from the call for evidence will enable us to assess the benefits of improved and more reliable broadband in Very Hard to Reach locations, both regarding their geographical remoteness but also compared to their current level of access to digital connectivity and alternative services.

Previous evidence has shown that residents in remote rural areas face substantially greater travel times and disruption when attending work or social activities as well as accessing basic services.

With agriculture, forestry and fishing making up approximately 50% of registered businesses in Very Hard to Reach Areas in England[footnote 17], these industries are disproportionately affected by poorer connectivity, which could have a detrimental impact on their productivity.

We heard

In the responses we received to the call for evidence, there was a consensus amongst respondents that an improved connection would improve the general standard of living for most in remote and rural areas of the UK.

Responses noted that an improved connection would improve the reliability of video and screen sharing on conference calls, improve the situation for those working from home, improve access to services for an ageing population, reduce social isolation, further enable location-based services and increase productivity as a result of less time being spent waiting for a connection to load.

All responses said that better broadband would improve access to online services, such as banking and healthcare, the ability to work from home and keep in touch with friends and family.

In the survey, we asked respondents whether they believed better broadband would improve their ability to keep in touch with family and friends, use online entertainment, access support services, work from home whilst caring for someone, and improve their welfare and wellbeing. As shown in Figure 6.1, we found that across all ruralities, respondents overwhelmingly agreed that better broadband would improve all of these things. Here, we define agreement with these statements as respondents choosing either agree or strongly agree in response to the questions posed.

Figure 6.1: Almost all respondents agree broadband improves key facets of their lives regardless of rurality.

| Use cases posed to respondents | Urban | Rural | Remote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keeping in touch with family | 93% | 95% | 95% |

| Online entertainment | 95% | 98% | 99% |

| Accessing support services | 93% | 95% | 98% |

| Working from home whilst being someone’s carer | 95% | 97% | 95% |

| Welfare and wellbeing | 95% | 97% | 96% |

Questions: Do you agree or disagree with the following statements: Better broadband would improve my ability to keep in touch with friends and family, Better broadband would allow me to/improve my access to online entertainment (e.g. films and TV streaming), Better broadband would make it easier to access support services, Better broadband would improve my ability to work from home whilst also caring for others, Better broadband would support my well-being and welfare. N = 314, 885, 1523, 1823, 1689 by use case respectively. When respondents chose ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to the question above, this is considered a positive perception.

Education was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and highlighted the need for improved connectivity and limitations imposed on those with limited service.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of students were expected to work from home due to COVID-19 restrictions. Online schooling was found to be a particular challenge for those living in rural areas due to poor connectivity.

We heard through long-form responses that respondents found better broadband allowed for easier and better remote learning, especially when it is the only option (e.g. during national lockdowns) as well as better live-streamed online lessons.

In its response, the National Association of Local Councils (NALC) reported that some pupils were forced to attend school by exception because of poor connectivity. It is believed that for many of these pupils an improved broadband connection would have allowed them to learn from home and play a more interactive role in their remote education than was otherwise possible. In its response, Pupils 2 Parliament said that with faster broadband, the children and young people they had interviewed would play more games, faster, more complicated and with better graphics, do online school homework and be able to call friends and family.

Figure 6.2 shows that the proportion of respondents who had a positive perception of virtual education increased across ruralities since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The highest proportion is in remote areas, but the largest post-pandemic increase is in rural areas. We define a positive perception as a respondent choosing either ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ to one of the statements put forward.

Figure 6.2 The majority of respondents had a more positive perception of virtual education after the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Rurality | Pre-Covid | Post-Covid |

|---|---|---|

| Urban | 32% | 39% |

| Rural | 47% | 61% |

| Remote | 57% | 63% |

Questions: Based on your virtual education experience before March 2020 (the beginning of the first COVID-19 lockdown), please rank the following statements: It saved you time compared to a face to face lesson, The virtual lesson’s structure was as good as being face to face, Broadband quality didn’t affect my virtual lesson, The quality of learning was as good as being face to face, The household participant felt as engaged in the virtual lesson as a face to face lesson, The household participant would be open to having another virtual education session. Based on your virtual education experience since March 2020 (the beginning of the first COVID-19 lockdown), please rank the following statements: The structure of virtual lessons was as good as face to face, Your teachers/lecturers adapted quickly and comfortably to virtual lessons, You had all the required technology to best adapt to virtual learning, Broadband hasn’t affected your virtual education experience, The household participant felt as engaged in the virtual lesson as a face to face lesson, The household participant would be open to having another virtual education session. N = 41, 426, 63 respectively by rurality

Productivity

The responses to the call for evidence suggested that most rural businesses already make use of online applications for accounting, orders, conferencing, and banking where they can. However, many struggle without ‘decent broadband’ and therefore require better connectivity to complete tasks. All respondents said that improved connectivity would improve the productivity of businesses and would mean that online applications can be used more extensively and efficiently.

In its response, Which? highlighted a study by Olive which reported: ‘58% of people said that they had been unable to access the help of online banking facilities they needed from home since [the COVID-19 national] lockdown’. Respondents to the call for evidence consider these services an integral part of the modern lifestyle. National Parks England told us that these online services are vital in remote and rural areas to provide online access to services that are otherwise physically located many miles away.

We heard that the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the issues faced by those with poor connectivity. Most respondents noted that some rural businesses would diversify if they had the connectivity to do so.

The restrictions imposed on businesses through the COVID-19 pandemic has however forced some rural businesses to use what connectivity they have to diversify their business to continue running. Caithness Chamber of Commerce said this is most notable in the food and drink manufacturing sector who made use of social media and online ordering to move to a direct-to-customer model during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tourism NI noted in its response that ‘many businesses have already enhanced their online presence, or may do so’ to improve their current situation and aid recovery post-pandemic.

While the general lack of connectivity appeared to affect the day to day running of rural businesses based on responses received to the call for evidence (online bookings, placing orders with suppliers, etc), Historic Houses reported that many of their members adapted their visitor attraction businesses during the national COVID-19 lockdowns. They were able to offer virtual tours, online exhibitions and craft fairs despite these changes requiring a faster speed than usual.

Figure 6.3 illustrates that approximately 28% of businesses in our survey said they were able to diversify using their current digital connectivity. However, 30% said that poor connectivity was a barrier to their diversification plans.

Figure 6.3: Digital connectivity has allowed some firms to enter different markets, the largest effect has been in the wholesale/retail market

| Percentage of respondents | No - I cannot diversify because of problems with my digital connectivity | No - diversifying has been unrelated to digital connectivity/I have not diversified | Yes - I have used/am planning to use it to diversify | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 30% | 41% | 28% | 100% |

| Agriculture | 30% | 47% | 23% | 100% |

| Transport/storage | 35% | 33% | 32% | 100% |

| Hotels/Restaurants/Leisure/Tourism | 37% | 40% | 23% | 100% |

| Wholesale/retail | 0% | 21% | 79% | 100% |

Question: Has digital connectivity enabled you to enter different markets/sectors in addition to your original business activities? N = 396

In their response to the call for evidence, Historic Houses agreed that diversification was important, stating that:

Reliable connectivity in rural areas can also enable historic house estates to diversify by offering business lets and units to other rural SMEs and start-ups. For example, Houghton Hall and Belvoir Castle have recently successfully set up business parks and retail parks on their estates. Access to reliable broadband is critical to these initiatives, and a lack of connectivity is currently a major barrier to businesses basing themselves in more remote areas. Driving more business to rural areas will support fragile rural economies, provide jobs and improve access to products and services for people living in rural areas.

Openreach stated in its response to the call for evidence that nationwide-full fibre could enhance workforce participation through remote and flexible working. They estimate that this could result in:…

Nearly 1,000,000 more people could enter the workforce by 2025 (compared to around 500,000 in the previous research). This includes over 300,000 working-age carers, nearly 250,000 older workers, and 400,000 parents of dependent children

In addition to the £59 billion GVA boost, the increase in workforce participation would have a GVA impact of £25 billion (approximately doubling the previously estimated impact of £13 billion) – increasing GVA in 2025 by just over 1.3%.

While this research was national, it did not provide a breakdown of rurality. However, Openreach noted that ‘it did assess the residential choices in several different density areas, including the lowest density’.

The Agricultural Productivity Task Force (APTF) stated in its response to the call for evidence that ‘research conducted in the US has determined that successful implementation of digital connectivity could bring an additional $500 billion to global GDP by 2030.’

Agriculture

From an agricultural perspective, improved connectivity could increase farm productivity through monitoring crops and livestock, access to remote learning and working, leading to expansions in businesses and diversification of farm businesses, and improved farm safety. It could also lead to an adoption of AgriTech and 5G technologies onto farms.

NFU said in response to the call for evidence that ‘7.8% of the farming workforce [are] over 70 and therefore in the vulnerable group, the lifeline that digital connectivity gives cannot be underestimated.’

Many agricultural applications have importance for running a business or working remotely, and the importance was exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many agricultural representative organisations offered examples in their responses: - Farmers’ Union of Wales: ‘many farmers are still unable to complete online quarterly VAT returns, SAF, BCMS or EIDCymru submissions due to poor broadband, and must rely on others to do this for them.’ - Agricultural Productivity Task Force: ‘Precision farming is a term for farming practices where technology is used to improve efficiency and is becoming increasingly common and has the potential to improve yields, profits, and lessen environmental impact. Precision farming is used across farm types with farmers using technology to manage crops or livestock. A report of case studies showed that dairy farmers save approximately 20% on labour through the use of robotic milking systems and some farmers reported increases in milk yields of 2-12%.’ - National Farmers Union: ‘On many horticulture farms (such as soft fruit farms) irrigation is almost entirely computerised with programmes that water each plant to meet individual water needs.’

While no responses were given explaining how the provision of specific broadband services would have social or economic benefits to remote rural customers, many responses explained how improved connectivity overall would have social and economic benefits. This shows that consumer focus is broadly on the availability of connectivity rather than the technology available to deliver it.

Respondents to the call for evidence highlighted the potential for improvements in digital connectivity that could lead to significant economic, social and environmental benefits.

The CLA stated in its response to the call for evidence that ‘When looking at the potential of digital connectivity in rural areas, the Rural England and Scotland’s Rural College report estimates that: ‘Unlocking the digital potential of rural areas across the UK could add between £12 billion and £26 billion (Gross Value Added) annually to the UK economy. This would result from the additional turnover achieved by rural-based businesses, which would be between £15billion and £34 billion annually.’

The Agricultural Productivity Task Force responded to the call for evidence by noting that ‘A report from the Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) for Openreach estimated that businesses with a substantial broadband speed increase of 200-500 Mbps had an estimated incremental impact of 3% productivity gain per worker. The report states that some productivity increases will be indirect where the farmer themself may not have fibre broadband, but if others that they interact within the supply chain are running more efficiently, it will contribute to an overall improvement in productivity. This will arguably be even greater for rural businesses as the current start point is much lower than the standard business.’

Caithness Chamber of Commerce also believes that there is no need for an assessment of the economic or social benefits of the provision of improved digital connectivity as it is fundamental to doing business today.

There were 140 agricultural firms surveyed and 30% required whole farm coverage. As seen in Figure 6.4, of the 30% that required whole farm coverage over half relied on a mobile network to provide coverage and 20% used FWA.

Figure 6.4: Most agricultural firms who use connectivity across their farm use a mobile network.

Question: What do you have in place to provide whole-farm connectivity? N = 36

A boost to the local economy

Several responses from representative organisations said that improved digital connectivity could retain and increase rural populations and help address the issue of an increasingly ageing population.

It was also suggested in long-form responses that an improvement in digital connectivity in rural areas may bring more tourism as rural businesses will be able to attract more guests with online advertising, and tourists will enjoy feeling connected in rural locations. In its response, the British Holiday & Home Parks Association (BH&HPA) said: ‘Holidaymakers may also be taking longer breaks with the option to work while away from home. Parks are therefore finding that the provision of wi-fi to their customers or holiday caravan owners is becoming more important and is regarded as an essential service rather than a ‘nice to have.’

Lancaster University Management School found in its study that there is a desire for good connectivity as it attracts and keeps people in the community. In particular, they said that 5G could future-proof the community and fast track entrepreneurial and business diversification plans.

Health and wellbeing

Improved broadband is thought to improve both mental and physical health, as well as overall increasing safety. This is especially important for those living in rural and remote areas, who have dangerous occupations.

While respondents seem generally keen on online/virtual health services such as online GP appointments, many reported that members were unable to make use of them due to poor connectivity. Respondents say this is an example of needing better connectivity in rural remote areas.

We heard that improved connectivity means that it could be easier to keep in touch with loved ones, even if it is not in person. All respondents said that access to services, such as online libraries, medical appointments, learning, and banking, due to better connectivity would improve wellbeing and welfare. In their research, Lancaster University Management School had a respondent who said: ‘My heart sinks when the landline and broadband go down. It leaves you feeling isolated (particularly as we have no mobile reception) as it sometimes takes days to be resolved’.

The theme of isolation was recurring and Farmers’ Union for Wales said in their response ‘farming is known as a particularly isolated occupation, with the highest rate of suicide above any other occupation. In a recent survey by Tir Dewi, 51% of farmers surveyed in Powys saw mental health as an issue affecting them. The [COVID-19] pandemic has prevented agricultural shows and agricultural markets from operating as usual, therefore digital connectivity has been even more important for allowing farmers to have contact and socialise (albeit over a screen).’

Environmental impacts

It was noted by some respondents that improved connectivity would have a secondary benefit of helping to reduce the environmental impact of some activities as well as helping to monitor activities related to the environment.

Lancaster University Management School said in its response:

The Environmental Monitoring use case is focusing on monitoring water and flooding in Coverdale and surrounding areas by engaging with three principal infrastructures in monitoring activities: vulnerable bridges, roads, and ancillary infrastructures. The goal is to be able to intervene earlier to prevent expensive damage, either through bridge collapse or total road closures through remote monitoring 5G enabled equipment. Several bridges have been identified together with a local water treatment plant that supplies water to a local village.

The Agricultural Productivity Task Force (APTF) stated that improved broadband would allow for more ‘precision farming’ which would ‘improve efficiency and is becoming increasingly common and has the potential to improve yields, profits, and lessen environmental impact.’

As further environmental regulations and agri-environment schemes are introduced, the Farmers’ Union of Wales (FUW) said that connectivity ‘will be increasingly important to enhance agriculture’s beneficial impact on the environment, to monitor and document improvement, and to improve accuracy of inputs.’

Research from 2018, highlighted Cornwall Council’s response, that the amount of time people are working at home has increased since connecting to a superfast service and as a result ‘The uplift in homeworking has positive environmental consequences – taking an average of 154 miles off the typical weekly commute.’[footnote 18]

7. Topic C: Barriers

The questions asked in this section can be found in Annex A.

Context

The very low presence and availability of existing networks in remote rural areas is a known fundamental barrier to the adoption of improved broadband services in Very Hard to Reach Areas.

While the government has substantial and detailed data, typically at the premises level, on ‘fixed wired’ broadband networks, data on ‘fixed wireless’ networks is less detailed and often relies on modelling assumptions.

Furthermore, information on space-based systems such as satellites is much more limited and often provided on a case-by-case basis by providers themselves rather than through official data gathering (e.g. Ofcom Connected Nations Reports).

This call for evidence aimed to assess how best to remove current barriers to delivering improved broadband to consumers in Very Hard to Reach locations and to realise the benefits without distorting existing competitive markets.

From previous correspondence to the department, it was identified that some of the most common barriers to consumers at present are, in no particular order:

- high quotes given by broadband providers

- information on future builds or current availability is not accessible

- general lack of infrastructure, e.g. premises too far away from the cabinet, with no/intermittent 4G signal

- the premises have missed out or been excluded from a previous network build

We heard

Several significant barriers to better broadband connectivity remain for both businesses and consumers in remote rural areas, leaving them with fewer choices and slower speeds than their urban and suburban counterparts.

Several barriers to faster connectivity were identified by consumers, businesses and representative organisations in response to the call for evidence both through the survey and the long-form responses.

The most commonly identified barriers to better connectivity included; the availability of services in an area, the cost and reliability of a given connection and the perception that switching broadband providers could be risky and lead to a loss of service completely.

The responses to both the consumer and business survey highlighted that premises in remote and rural areas had significantly slower average download speeds than their counterparts in urban and suburban areas, despite having similar broadband demands (Figure 5.2). This speed data was generated by matching the respondents’ postcode with Ofcom connected nations data. This demonstrates that one of the primary barriers to accessing faster connectivity speeds faced by consumers and businesses in Very Hard to Reach areas is a lack of availability.

The majority of both remote and rural premises are designated by Ofcom as Area 3 (91% and 83% respectively). These are ‘Non-Competitive Areas’ as determined by the regulator, with Openreach typically the only operator providing a large-scale network. The remaining premises are located in Ofcom Area 2, which are ‘Potentially Competitive Areas’ where one or more existing alternative ultrafast networks are already present or where one or more operators have a plan to deploy.

Even where competitive alternatives to Openreach’s network exist, consumers may not feel comfortable switching. Consumer advocate group Which? highlighted in its response that 38% of consumers believed that changing providers ‘is too risky and may lead to a worse service’, with almost half of this group (46%) preferring to ‘stick with their current broadband as it’s ‘tried and tested’.

The consumer responses to our call for evidence were comparable to the findings by the Which? research. When asked whether in the past 3 years they had done anything to try and improve the speed or quality of their broadband connection 29% of respondents said they had changed their provider — with 32% stating they had changed package or service (whilst remaining with the same supplier).

The responses from the call for evidence consumer survey highlight the difficulty that many consumers may feel when it comes to accessing a better broadband connection through a fixed-line. Often they are left with only one fixed infrastructure provider (Openreach), meaning that switching (retail provider) will not result in a faster or more reliable connection.

While FTTP remains the preferred technology choice, less than half of businesses and consumers were aware of the government’s Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme. However, businesses and consumers are willing to try alternatives to fixed connectivity where available.

There are several alternative connectivity options available in some rural areas to both residential consumers and businesses who are looking to switch away from a fixed line broadband service in order to boost reliability or speed such as 4G/5G Fixed Wireless Access and satellite.

In addition, there are a number of schemes that may be able to help consumers and businesses access financial support to upgrade their connection including the broadband Universal Service Obligation and the government’s Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme.

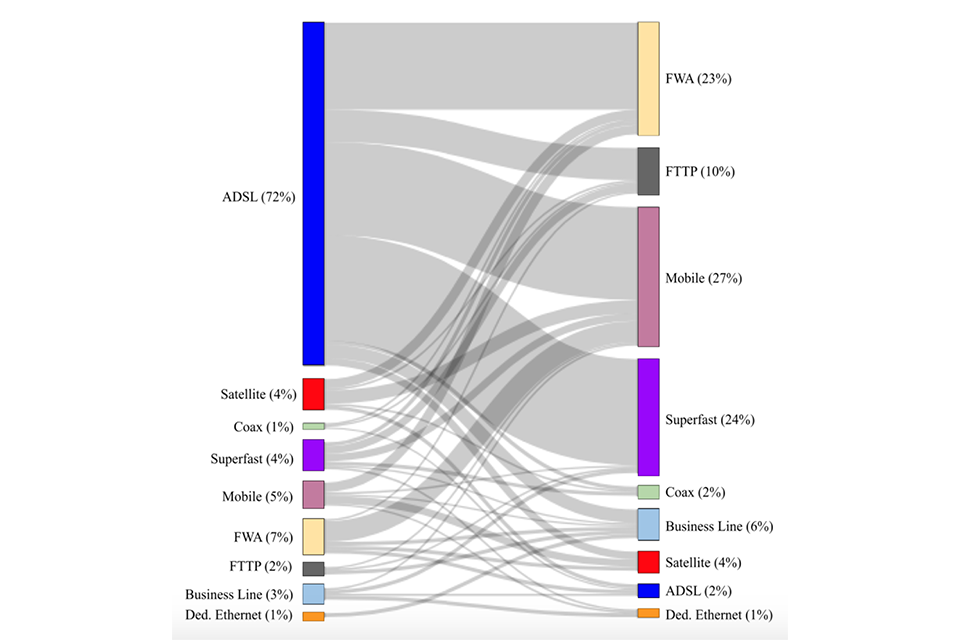

Only 14% of consumers stated that they had changed the technology used to deliver broadband in the past 3 years. Of the consumers who had switched technology, the majority had moved from ADSL to either a Superfast connection, Fixed Wireless Access, or a mobile broadband solution. (Figure 7.1)

Figure 7.1: Sankey diagram of consumers who said they switched technology (Left: from, Right: to). Consumers are willing to try alternatives to fixed-line connections to access an improved connection.

Diagram shows consumers are willing to try alternatives to fixed-line connections to access an improved connection.

Question: You stated that you changed technology to improve broadband, which technology did you change from and to? N = 256. ‘Other’ includes ‘Dedicated Ethernet’ and ‘Hybrid Fibre Coaxial Cable’.

On the other hand, 65% of business respondents indicated that they had tried an alternative to fixed broadband, with 56% of those surveyed exploring Fixed Wireless Access and 43% exploring Satellite. Just under one-third (29%) of all respondents indicated they had tried both. Businesses appear to be more active in exploring new technologies compared to consumers.

Responses from a number of representative organisations noted that FTTP remained the preferred technology choice. However, they also noted that consumers and businesses without access to FTTP were happy to take on a Fixed Wireless or Satellite connection to boost their connectivity options.

While the local delivery body, Connecting Devon and Somerset stated that respondents only saw ‘technologies like 4G or satellite [as nothing] more than potential interim, stop-gap solutions’, other respondents were more positive and called on the government to do more to support them.

Which? responded that it recognised a ‘trade off’ needed to be made between ‘cost of provision, cost to the consumer and speed of the connection.’ Historic Houses noted that wireless systems would ‘reduce the expense and disruption of cable-based broadband in protected areas’, while Lancaster University Management School stated that as part of its independent study Mobile Access North Yorkshire (MANY) wireless systems were seen as the most ‘cost-effective method’ of delivering high-speed internet services in rural and hard to reach areas.

Awareness of Fixed Wireless Access was low amongst consumers, whereas almost half of respondents were aware of a satellite connection. When asked if they had explored the use of either Fixed Wireless Access or satellite service, 71% stated they were aware of what Fixed Wireless Access is, with 79% saying the same about satellite connectivity (Figure 7.2).

However, despite high awareness, satellites were less explored than Fixed Wireless Access connections, indicating a gap between awareness and interest. One potential explanation is increased media coverage of new broadband satellite projects such as OneWeb and Starlink.

Figure 7.2: Consumers are more aware of satellite connectivity but less interested in taking out a connection

| Fixed Wireless Access / Satellite | Fixed Wireless Access | Satellite |

|---|---|---|

| I’ve explored the use of fixed wireless and it is available | 234 | 244 |

| I’ve explored fixed wireless but it isn’t available in my area | 408 | 232 |

| I’ve not searched about fixed wireless services | 301 | 477 |

| I am aware but not interested in fixed wireless | 150 | 437 |

| I’m not aware of what fixed wireless is | 437 | 359 |

Questions: NSPL rurality based on postcode (What is your postcode?) Have you explored the use of fixed wireless services in your area? Have you explored the use of satellite services in your area? N = 1749

When respondents were asked what was preventing them from taking a FWA or satellite service, both consumers and businesses noted that price, speed and reliability were all concerns that prevented them from taking an alternative service. Respondents also noted that data caps, listed building status and high latency were other smaller factors that contributed to this hesitancy to adopt a Fixed Wireless Access or satellite service.

The findings from the call for evidence survey were similar to comments made by organisations representing consumers. The Ofcom Advisory Committee for Scotland noted that ‘While many hail satellite broadband as the solution to rural connectivity, costs, performance and latency have traditionally been mitigating factors. Further, in areas of the Scottish Highlands, mountainous territory has prevented optimal reception.’ Furthermore, the National Association of Local Councils (NALC) highlighted that while Councils were aware of the services on offer, often their constituents were not.

Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme and the broadband USO

The majority of market participants that responded to the call for evidence stated that they were not registered with one of the schemes listed in question C27.[footnote 19] However, Openreach and the rural SMEs including Quickline and Wessex Internet were registered to some, or all, of the schemes listed. This was not unexpected given that many of the respondents to the call for evidence were either service or infrastructure providers who are ineligible to access the schemes due to the current limitations of their infrastructure.

Awareness of both the Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme and the broadband Universal Service Obligation (USO) was low amongst both consumers and businesses.

As previously shown in Figure 5.10 and Figure 5.11, when asked about both schemes, only 12% of businesses stated they had applied for a voucher and of those that hadn’t applied, only 30% said they were aware of where to find further information. Only one business mentioned the broadband Universal Service Obligation .

Consumers showed a slightly higher degree of awareness than businesses when asked about available broadband schemes, although less than half (41%) had explored either a community broadband scheme or applied for a Gigabit Broadband Voucher

When asked in the call for evidence survey, exactly half of all suppliers who responded stated that they offered either a ‘community-based partnership’ or another mechanism which allowed consumers to group together to deliver an improved network.

Half of the suppliers also noted that they offered discounts for customers based on whether they were able to self dig or provide site provision or power. This helped to lower the cost to the customer and remove a potential barrier to deployment for both supplier and customer.

Responses to the call for evidence showed that on average, 172 connections per supplier have been made using community-based partnerships.[footnote 20] While often used within a community-based partnership, not all of these connections may have been delivered using the government’s Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme.[footnote 21]

However, more broadly, representative organisations noted that both the broadband USO and the Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme had aspects to them that meant applicants were unable to benefit due to the high connection costs — even with the additional funding offered.

The Country Land and Business Association (CLA) stated in its response ‘One of the major issues we are evidencing with the Universal Service Obligation (USO) is that the application of the price threshold of £3,400 for infrastructure is a major constraint…’ while the National Farmers Union for England and Wales (NFU) highlighted that the price cap made it ‘unlikely that many of our farms will be able to qualify for the USO.’

Furthermore, with regard to Gigabit Broadband Vouchers, Which? stated that ‘While access to vouchers, such as the Gigabit Broadband Voucher Scheme, aims to help those in rural areas with slow speeds, costs may still be prohibitive even with this support in very hard to reach areas.’

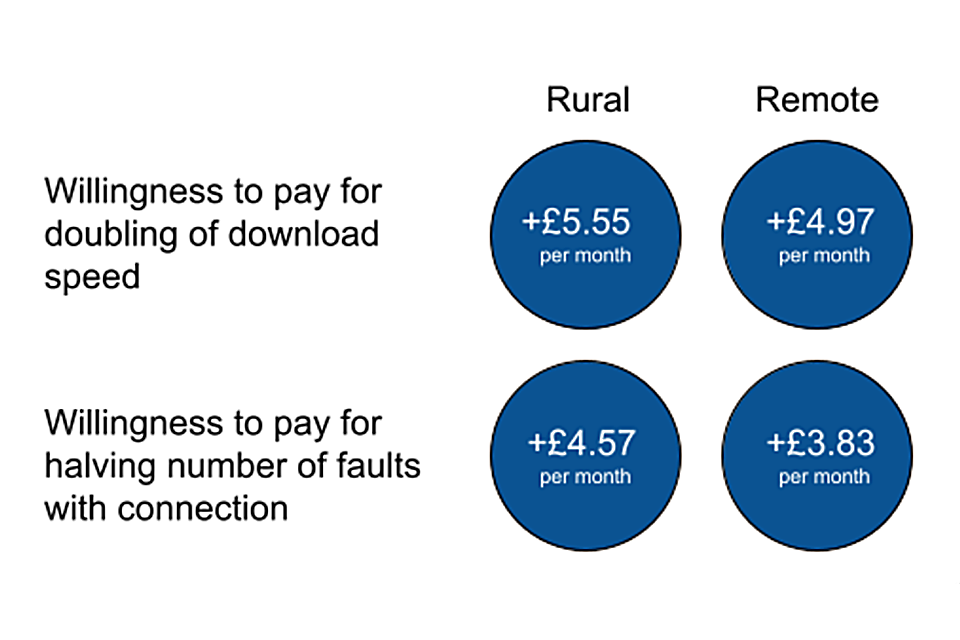

When taking out a new service, responding businesses and consumers are willing to pay slightly more to see a doubling of their broadband speeds and increased reliability.

As part of the consumer survey, we asked respondents both what they were paying for their broadband connection, as well as how much extra they would be willing to pay for:

- a doubling of their download speeds

- a tangible increase in reliability, such as halving the number of faults

The average consumer who responded to the call for evidence reported currently paying, on average, £37.16 for their broadband connection, slightly higher amount than Ofcom’s estimated average of £31 for dual-play services.[footnote 22]