Oil and gas price mechanism consultation (HTML)

Updated 26 November 2025

Foreword

The UK oil and gas industry has played a significant role in our country’s history. Alongside its critical role in our energy supply, it has contributed over £400 billion in production taxes since the late 1960s and created thousands of jobs, especially in the North-East of Scotland.

The sector is expected to contribute a further £19 billion in tax receipts between now and 2030, supporting the public finances and the UK’s clean energy transition. This transition will bring significant economic opportunities for businesses and workers whilst helping to protect consumers from future price shocks.

After a period of several changes to the fiscal regime, I recognise the importance of providing the oil and gas sector with long-term certainty on taxation. That is why this government is committed to ending the Energy Profits Levy (EPL) on 31 March 2030, or earlier if the Energy Security Investment Mechanism is triggered. Once the EPL ceases, it is the government’s intention to implement a new mechanism that gives investors certainty about how the fiscal regime will respond to any future oil and gas price shocks.

The government is clear that it is right that when oil and gas prices are unusually high, the sector should make an additional contribution to the public finances. I am pleased to see many in the sector agree with this principle but note there are a range of views on the appropriate approach. That is why this consultation seeks views on how to design a new mechanism which will balance the needs of the sector, investors, and the Exchequer at times of unusually high prices.

This new mechanism will be predictable and sustainable, and we will ensure that it minimises distortions on investment decisions when prices are not unusually high. This will support continued investment in our domestic oil and gas production throughout the transition.

Over the past six months, I have had constructive and open discussions with operators and supply chain companies operating in the UK oil and gas sector. I would like to thank the sector for its constructive approach to these discussions with both me and HM Treasury officials. I look forward to further close working with the sector and other stakeholders to develop the best possible price mechanism for the future.

James Murray MP

Exchequer Secretary to the Treasury

1. Introduction

The government recognises that the UK oil and gas industry requires fiscal stability and certainty to make confident, long-term investment decisions including investment in renewable technologies. To provide this, at Autumn Budget 2024 the government committed to ending the EPL in 2030 (or earlier if the Energy Security Investment Mechanism (ESIM) is triggered). The government has also committed to working in partnership with the industry and other stakeholders to introduce an Oil and Gas Price Mechanism (referred to here as mechanism or new mechanism) that can respond to future oil and gas price shocks.

This document sets out the government’s policymaking objectives and design options for a new mechanism. The government is committed to introducing a new mechanism that:

-

Delivers a fair return on the UK’s resources at times of unusually high prices,

-

Is predictable and provides certainty,

-

Minimises distortions on investment decisions,

-

Minimises the administrative burden for taxpayers and HMRC,

-

Recognises the difference between oil and gas markets.

The new mechanism will allow the UK to benefit from immediate additional revenues during periods of unusually high prices, while also ensuring that the industry has the clarity it needs regarding the future fiscal landscape. By offering a stable and predictable framework, the government aims to strike a balance that supports both the Exchequer interest and the industry’s capacity to innovate, plan and invest in the future.

Chapter 3 sets out in more detail what the above objectives mean in practice. Chapter 4 explores two potential policy options including elements of the design which we ask for stakeholders’ views on, and Chapter 5 asks for views on the factors that should be considered when setting a threshold (the point at which this new mechanism applies).

The background on the current fiscal regime is outlined at Annex A. It currently consists of three permanent elements and one temporary element (the EPL). The permanent elements of the oil and gas fiscal regime and the EPL are not being considered as part of this consultation. The broader elements of the UK tax system as they apply to the oil and gas sector (such as Income Tax, National Insurance, VAT and mainstream Corporation Tax) are also out of scope.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) has launched a separate consultation and call for evidence, titled ‘Building the North Sea’s Energy Future’[footnote 1], which sets out the framework for the future of energy in the North Sea. The government is committed to providing stability and certainty in both the fiscal and regulatory regimes.

2. About you

Anyone is welcome to respond to this consultation. To help the government understand the context of your answers and assess the views from different stakeholders, it would be helpful to have some information about you. You should indicate if you are responding on behalf of an organisation, business or other group. In the case of representative bodies, please provide information on the number and nature of people you represent.

Question 1 What is your name?

Question 2 What is your email address?

Question 3 Which category in the following list best describes you? If you are replying on behalf of a business or representative organisation, please provide the name of the organisation/sector you represent, where your business(es) is located, and an approximate size/number of staff (where applicable).

-

Oil and/or Gas Upstream Producer (offshore)

-

Oil and/or Gas Upstream Producer (onshore)

-

Oil and/or Gas Mid or Downstream Sector

-

Oil and/or Gas Supply Chain

-

Renewable Energy Producer

-

Renewable Energy Supply Chain

-

Energy Trader

-

Energy Supplier

-

Carbon Capture and Storage Sector

-

Trade Body or Association

-

Provider of Finance

-

Environmental Group

-

Academic

-

Education and Skills

-

Accountant / Tax Adviser

-

Individual

-

Other

3. Context and Policy Objectives

For decades, North Sea operators and workers have helped to power the UK and beyond. Successive administrations have developed a fiscal regime that supports companies to invest whilst aiming to ensure that an appropriate share of the benefits accrues to the UK economy as a whole.

The current fiscal regime consists of three permanent elements: Ring Fence Corporation Tax, Supplementary Charge, and Petroleum Revenue Tax, and additionally the temporary EPL. Further information on the fiscal regime can be found at Annex A.

Prior to 2022, the oil and gas fiscal regime did not include an element that could respond specifically to oil and gas price shocks. That is why, following the global increase in energy prices driven by global circumstances including Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the previous government introduced the EPL which is due to expire in 2030 or earlier if the ESIM is triggered.

Once the EPL ends, the government is committed to ensuring that there is a permanent mechanism in place to respond to future oil and gas price shocks. This new mechanism will form an integral part of the permanent regime (alongside the elements listed above) but responding only when there are unusually high prices, helping to protect jobs in existing and future industries.

The government has developed five key policy making objectives that will guide the design of the new mechanism which can be found below.

This Chapter provides further explanation of these objectives, alongside the evidence that the consultation is seeking to gather in line with each of them.

Deliver a fair return on the UK’s resources at times of unusually high prices

The oil and gas fiscal regime is designed to deliver a fair return for the UK for the exploitation of our natural resources. This recognises our ownership of our natural resources, and that it is right that the UK shares in the profits from their exploitation. Therefore, the new mechanism must also ensure that the UK receives a fair share during times of unusually high oil and gas prices.

The mechanism, as with all fiscal measures, must also be fair and proportionate for industry and investors. This means setting the thresholds (see Chapter 5) and rates at the appropriate level ensuring that the sector can continue to manage existing fields and invest in the clean energy transition, protecting jobs in existing and future industries. The new mechanism will not target revenues or profits made outside times of unusually high prices.

This consultation will seek to understand the costs associated with operating in the UK/UKCS and will ask for evidence on forecasting and modelling to support the development of a methodology to define unusually high prices.

Be predictable and provide certainty

The government recognises that stability in the fiscal regime plays an important role in enabling investment. While this is the case across the economy, it is particularly true for the oil and gas industry given the time horizons over which projects occur, the significant upfront capital investment required, and time taken from initial investment to return on that investment. However, the government acknowledges that changes to the oil and gas fiscal regime in recent years have led to a period of uncertainty for the sector and its investors.

After this period of change, a key aim of the mechanism is to provide the industry and its investors with long-term certainty and predictability on how the fiscal regime will respond to unusually high prices after the EPL ends in 2030 or earlier if the ESIM is triggered. To achieve this the price thresholds (i.e. the circumstances where the tax will apply) and rates of the mechanism will be set out in advance of the EPL ending. This will mean industry can more easily project how much tax they might pay in times of unusually high prices, should such a circumstance occur.

By introducing the mechanism in advance of a future price shock, this will also ensure that the nation can share in the benefits of price shocks immediately.

To further support predictability, the mechanism will be robust and durable. It will be designed so that it remains appropriate, relevant, and proportionate in the long-term.

This consultation will gather evidence on long-term planning and decision-making processes to ensure the mechanism’s relevance and effectiveness.

Minimise distortions on investment decisions

Oil and gas production in the North Sea will be with us for decades to come and the government is committed to supporting companies to manage existing fields for the entirety of their lifespan. Many oil and gas companies are also making significant investments in the clean energy transition including decarbonising their own production.

Therefore, to support existing fields and the energy transition, it is important that the mechanism does not, as far as possible, influence or distort investment decisions made during times of normal oil and gas prices. To achieve this, the mechanism will only apply to the gains companies receive when prices are unusually high and will not apply to gains when prices are closer to normal levels.

Minimise additional administrative burdens for taxpayers and HMRC

Administrative complexity can lead to additional costs for businesses and can lead to errors in tax returns. This is why the government will aim to implement a mechanism that is as simple as possible for taxpayers and HMRC to administer. This also recognises that a high administrative burden would be particularly disproportionate for a new mechanism that is only intended to apply during times of unusually high prices.

Recognise the difference between oil and gas markets

Oil and gas prices have historically risen and fallen together. The two commodities are also often produced together as by-products of each other.

However, the government recognises that oil and gas markets are changing, and that whilst oil and gas prices are still rising and falling together, gas prices have been subject to greater price shocks. The government also recognises that some projects are significantly more focused on one commodity than the other.

This consultation will therefore consider the relationship between oil and gas production and profits and consider scenarios in which one commodity is subject to unusually high prices while the other is not. The new mechanism will aim to recognise the differences in the markets.

4. Policy Options

The government has considered policy options, including international comparators and engaging in discussion with stakeholders. It is now consulting on two models. The first, a revenue-based model (RBM) that would target the excess revenue a company receives for its oil and gas sold above threshold prices. The second, a profit-based model (PBM) that would target a proportion of profits deemed to arise from unusually high prices by reference to ‘average market prices’ and the thresholds.

These models have been designed in line with the government’s objectives as set out in Chapter 3.

A comparative analysis of the models against the objectives suggests that the RBM allows for a more effective targeting of gains arising from unusually high prices, ensuring the impact on investment decisions is minimised as well as being able to distinguish between oil and gas more easily. Whilst the government’s current preference is to introduce an RBM, this consultation seeks your views on the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, and your views on the specific design choices of each model. The government will take a final decision once it has considered all the views submitted through the consultation.

Chapter 5 discusses the mechanism’s thresholds, how they will be set and how they will be adjusted. This Chapter will therefore refer generically to ‘the thresholds’. The government is seeking views in this Chapter on the overall structure of the mechanism. Once the thresholds are set, as informed by views put forward in response to Chapter 5, it will then be applied to the models outlined below.

As is standard for government, it will not consult on the tax rate of the mechanism. The final rate will depend on the final policy design, and the government’s decision on the price threshold (it is likely that a higher threshold will require a higher rate and vice versa).

Revenue-based model (RBM)

A RBM would identify the revenue above the thresholds (one for oil and one for gas) and apply the tax to this element. For example, if the threshold was $2 a barrel of oil and a barrel of oil is sold for $3, then revenue of $1 would be subject to the RBM.

The ‘market price’ (or ‘spot price’) of either oil or gas at a given time is not necessarily the price a company receives for their oil or gas. Often, companies will hedge against price fluctuations or sell their oil and gas at a price that is distinct from the market price at that time (this can be done using forward contracts, derivatives, contracts with banks or other mechanisms). The government wants to ensure that the true value a company receives for their oil and gas is what is considered for this new mechanism. Therefore, for the purposes of the RBM, realised prices for sales of oil or gas will be used.

However, the government is also aware that companies may use hedging and other financial instruments not directly linked to the specific sale of their oil and gas to mitigate the risk of price fluctuations. It is the government’s intention that the RBM will consider any gains or losses arising from the use of those financial instruments. The government will work with stakeholders to ensure the true realised value of sale is brought into charge.

As with other taxes that form the oil and gas fiscal regime, where oil or gas is sold on a non-arm’s length basis (e.g. to a trading company part of the same group) the RBM will apply similar rules for valuation purposes. [footnote 2]

The government is minded to apply the RBM to each transaction or grouped transaction (i.e. an amount of oil and gas sold at the same price on the same contract terms) because it better captures unusually high prices. This is on the basis that the administrative burden will be minimal as companies already keep details of transactions and achieved prices for accounting purposes. However, the government would welcome views on what the administrative burden would be in practice and to work with stakeholders to minimise this as far as possible.

As the RBM applies to revenues, no deductions for costs will apply. As outlined in Chapter 5, when setting the thresholds, the government will factor in the cost of operating and investing in the UK/UKCS. As the RBM will apply to the top slice of revenue achieved from prices above the thresholds (and will not apply to the portion below the thresholds), the government does not believe it is appropriate to introduce additional deductions or allowances. As set out in more detail in Chapter 5, the mechanism for adjusting the thresholds will also consider natural increases in costs over time that may otherwise impact a company’s core revenue.

The government does not envisage that the sector will face any exceptional costs exceeding those during times of normal prices but would welcome representations on this.

For completeness, the government wants to avoid a situation where there may be ‘double taxation’. Therefore, the tax point for the RBM would be the first point of sale following extraction. In most cases, this will be when the commodity leaves the ring fence.

Question 4: Do you foresee any challenges with using the realised price (rather than market price) as the determinant? If so, please provide further comment on those challenges?

Question 5: If you produce oil or gas, what is your strategic approach to mitigating the risk of price fluctuations? For example, how are different hedging practices and/or other financial instruments used? And what is the extent to which your organisation hedges vs selling at spot price?

If you do not produce oil or gas, what are the strategic approaches to mitigate the risk of price fluctuations that you see in the sector? For example, how are different hedging practices and/or other financial instruments used?

Question 6: Do you envisage any challenges to applying a RBM on a transaction basis? If so, please explain (including an assessment of the additional administrative burden). Linked to this, please provide comments on whether using the first point of sale following extraction as the tax point achieves the right outcome.

If you produce oil or gas, please provide information on how your organisation sells its oil and gas, as well as your record keeping practices.

Question 7: The government would welcome representations on the exceptional costs (above inflationary changes) that companies may experience during unusually high prices. Please provide supporting evidence.

Profit-based model (PBM)

To effectively target gains from unusually high prices and ensure the mechanism only applies when prices are unusually high, the PBM will identify a proportion of profits that will be deemed attributable to price shocks. This will be calculated by comparing an ‘average market price’ with the thresholds. The proportion that the ‘average market price’ is above the threshold will apply to the profit figure. The PBM will apply to that element of profit that has been deemed to arise from unusually high prices.

The government will set out clear rules for calculating the ‘average market price’ during a company’s accounting period. They will be similar to how the reference price is calculated in the ESIM[footnote 3].

At the end of a company’s regular accounting period (AP), a company will do this calculation as part of their normal CT return. If the ‘average market price’ across the AP is below the threshold in place at the end of the AP then there would be no further action. If the ‘average market price’ across the AP is above the threshold, then the PBM would apply to the amount deemed to arise from unusually high prices. This refers to the proportion of the company’s profits equal to the proportion that the ‘average market price’ for that AP is above the threshold.

For example, if a company makes £75 million profit and the ‘average market price’ across that company’s AP for oil is $9 a barrel and the threshold is $6 a barrel then 33.33% (£25 million) of the company’s profit will be deemed to arise from usually high prices and subject to the PBM.

The profit figure that the PBM will use will be an adjusted ring fence profit similar to the current EPL profit definition. This would exclude decommissioning expenditure and financing costs, and as this mechanism will only apply during unusually high prices, would only include losses arising in-year (including through group relief). There are principled reasons for this approach. First, this new mechanism would apply only at a specific point in time during unusually high prices. Second, this mechanism would only apply to the element of profit above the price thresholds, which will exceed core projected profits required to generate a return on investment over the life cycle of the project.

A key principle is that the new mechanism recognises different oil and gas markets. The government is aware of the complexity of identifying specific oil or specific gas profits. Whilst it is possible to distinguish the revenue arising from either oil or gas, it is very difficult to distinguish the costs specific to oil and costs specific to gas production. Therefore, the government is considering whether a proxy could be used to enable a level of recognition of the different oil and gas markets in a PBM. The government accepts that using a proxy comes with its own challenges, but on balance, may be the most appropriate approach. We would welcome stakeholders view on this approach and on what proxy may be appropriate. It is important that, whatever proxy may ultimately be used, it is easily verifiable without the need for additional compliance checks.

One option the government is considering is using the revenue shares from oil and gas as a proxy that would then apply to total profits (e.g. if a company sold oil and gas at a 2:1 ratio, 66% of the profit will be assigned as ‘oil profits’ and the remainder as ‘gas profits’). Another alternative is using production volume – where oil and gas are measured in terms of barrels of oil equivalent using agreed conversion factors – rather than revenue generated.

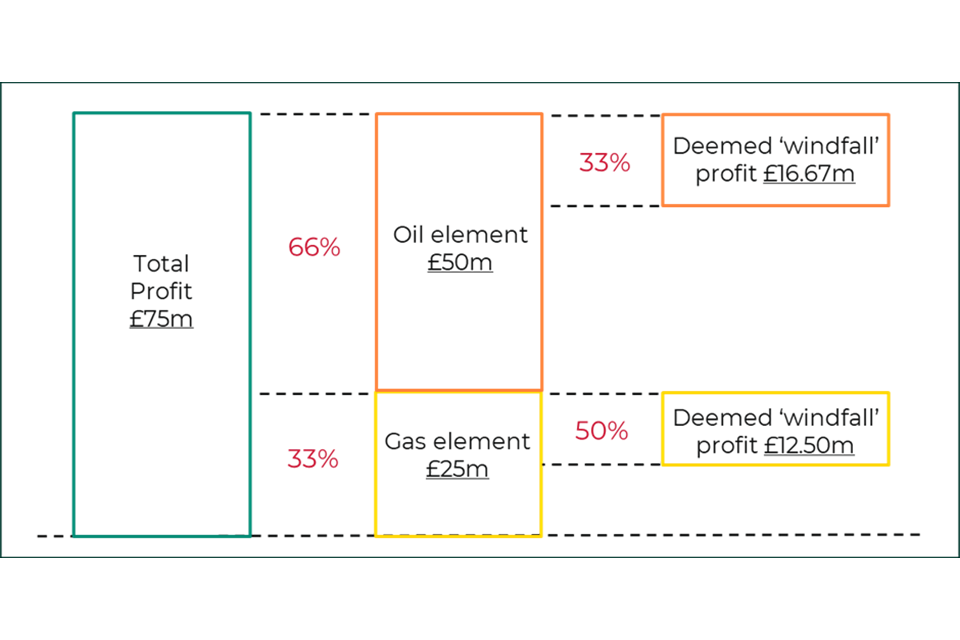

For example, to account for the different oil and gas markets, the calculation to determine the deemed profit arising from unusually high prices could have an oil and a gas weighting. Using the example above (and for this example a 2:1 oil to gas split has been used), £50 million will be assigned to oil and £25 million to gas. If the ‘average market price’ for oil is $9 a barrel and the threshold for oil is $6 a barrel, then 33.33% (£16.67 million) will be subject to the PBM. Separately, if the ‘average market price’ for gas is £5 a therm and the threshold is £2.5 a therm, then 50% (£12.50 million) will be subject to the PBM. Therefore, in total, £29.17 million out of £75 million will be subject to the PBM. A visual representation of this example has been provided below.

Figure 1.A - Example PBM recognising different oil and gas profits

As the PBM will only apply during unusually high prices, and on the top slice above the thresholds, the PBM will not include additional investment allowances.

Question 8: The government would welcome your views on the overall design of the PBM.

Question 9: The government would welcome your views on the tax base and definition for adjusted ring fence profits for the PBM.

Question 10: Do you agree that the most appropriate way to account for the different oil and gas markets in a profit calculation is to use a proxy rather than attempt to apportion costs? Please provide additional detail to support your view. In addition, what proxy would be most appropriate to use?

Administration of the Mechanism

A key objective of the mechanism is that it minimises, as far as possible, the administrative burden to both taxpayers and HMRC. The government also recognises that there will be periods where companies and HMRC will need to administer the mechanism when there are no liabilities (for example, when oil or gas prices are below the thresholds).

As far as possible, HMRC will seek to use existing systems and processes and will work with stakeholders to minimise that administrative burden.

Additionally, it is HMRC’s intention to utilise, as much as possible, the existing Corporation Tax (CT) administrative provisions[footnote 4]. That means that existing reporting and payments requirements will apply to the mechanism, including the Instalment Payment Regulations (therefore large, and very large companies will be required to pay their liability to the new mechanism in three instalment payments).

A final impact assessment will be made on the viability of this approach once the final policy design has been agreed.

Question 11: Do you agree that, if possible, the mechanism should utilise the existing CT administrative provisions? The government would also welcome views on the best approach to administer this new mechanism (as well as an assessment of additional administrative costs), with a view to minimising the administrative burden.

Comparison against government objectives

To analyse the merits of each model, the government has used the policy objectives for this mechanism. This is set out below.

The government would welcome views on the merits of each model. The government’s early thinking is that a RBM better aligns with the objectives set out in Chapter 3. This is mainly because it can more effectively target gains arising from unusually high prices and distinguish between oil and gas.

Table 1.A - comparison against government objectives

| Objectives | Revenue-based model | Profits-based model |

|---|---|---|

| Delivers a fair return on the nation’s resources at times of unusually high prices. | Easy to target outcomes of ‘unusually high prices. | More challenging to target outcomes from ‘unusually high prices’ as it would depend on a company’s profit margins. During unusually high prices, it would treat companies differently (e.g. loss making companies, by virtue of when high prices occur at a particular stage in their project life cycle, might not pay this mechanism despite benefitting from high prices). |

| Predictable and provides certainty. | Rates and thresholds would be set out in advance. Companies will be able to forecast when new tax payable, and as realised prices are used the amount of tax payable. | Whilst the rates and thresholds would be set out in advance, whether a company would be subject to this additional mechanism (over a project lifecycle) would be dependent on when high prices occurred – increasing uncertainty. |

| Minimises distortions on investment decisions. | Provided thresholds and rates are set at appropriate levels, straightforward to achieve through RBM. | Provided thresholds and rates are set at appropriate levels, can be achieved through PBM. Could risk distorting short-term decisions although unlikely to be significant. |

| Minimises additional administrative burdens for taxpayers and HMRC. | Companies will need to account for each oil and gas transaction separately. As far as possible, we will look to utilise existing HMRC systems to administer. | Depending on final policy design (particularly on the tax base that will be subject to this mechanism), companies would be required to calculate the deemed element of profit subject to the PBM and there could be an additional administrative burden. As far as possible, we will look to utilise existing HMRC systems to administer. |

| Recognises the difference between oil and gas markets. | Straightforward to account for differences in oil and gas as the revenues from oil and gas transactions would be accounted for separately. | Challenging to achieve as the ringfence currently accounts for oil and gas together. A PBM would likely rely on a proxy to apportion between oil and gas profits. If not, it will require complex rules to assign capex/opex to either gas or oil without using a proxy. |

Question 12: Do you agree with the government’s overall assessment that, in comparison with a PBM, a RBM better targets additional gains as a result of unusually high prices? Please provide additional comments to support your view.

5. Defining Unusually High Prices and Setting the Thresholds

A fundamental policy objective of the new mechanism is that it applies only at times of unusually high oil and/or gas prices. This Chapter sets out the factors the government will consider when defining unusually high prices, and how this will influence the government when it sets and adjusts ‘the threshold’ – the point at which the mechanism will take effect – noting the top slice design of this new mechanism.

The policy options the government is considering require a threshold to operate. As the impact of the threshold will vary depending on the final design choice, the government has not announced a specific threshold in this consultation. Instead, the government will consider the factors outlined below, and others highlighted by stakeholders. This is to take a data driven approach to ensure the mechanism provides a fair return on the nation’s resources at times of unusually high prices whilst supporting investment in the UK/UKCS.

Stakeholders will be aware of the EPL’s ESIM. The ESIM is a mechanism that is independent to the calculation of EPL liabilities. It is a mechanism that determines if and when the EPL should be permanently turned off based on oil and gas prices (the dual lock). The mechanism the government is currently consulting on will have a direct impact on the calculation for this new mechanism’s liability, with different gas and oil thresholds that work independently of each other (see para 5.6 on the interaction of different thresholds).

For the avoidance of doubt, this new mechanism will apply only to the element of revenue or profit above the threshold (not total profit or revenue).

It is important that the new mechanism, as far as is reasonably possible, recognises the different oil and gas markets. To that end, the government is considering setting two thresholds – one for oil and one for gas. The policy models discussed in Chapter 4 set out policy options to recognise the different oil and gas markets within this new mechanism to ensure, as far as possible, that the new mechanism captures revenue/profit from gas and oil separately.

The government recognises that there are multiple blends, types and categories of both oil and gas, and there therefore may be a case for introducing additional thresholds to reflect these variations. The case for this is particularly strong when comparing the pricing of Natural Gas Liquids (NGLs) and oils. However, to minimise the administrative burden for both government and the sector, the government’s current view is that one oil and one gas threshold is sufficient. Additionally, as these thresholds will be set to capture revenue/profit resulting from unusually high prices, the variance in commodity prices of different blends, types and categories of oil or gas is unlikely to have a material impact.

Question 13: Do you agree that two thresholds (one for oil and one for gas) are sufficient to effectively administer the new mechanism? If not, please provide detail on the variance between different blends, types and categories of oil and gas, the material impact on project economics as well as how many and which additional thresholds the government should consider.

In particular, how should the thresholds account for NGLs to ensure that the mechanism effectively targets gains arising from unusually high prices?

As well as the different blends, types and categories of oil and gas, these commodities are also sold in different units and contract types.

When considering different data sources to help set the thresholds, the government will, where possible, use spot Brent Crude prices per barrel in dollars for oil and NBP Day-Ahead prices per therm in sterling for gas.

For oil, the Brent blend is the most widely used price indicator for oil produced in the UK/UKCS, and is sold on the international market, priced in US dollars. The price for natural gas in the UK/UKCS, on the other hand, is largely influenced by European gas markets so pence per therm is appropriate. Both these units are also used by the Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). As such, it is the government’s current approach to set the thresholds using those units (i.e. $/barrel of oil and p/therm of gas). This approach is in line with previous engagement with the sector in developing the ESIM.

The government is aware that there are some advantages and disadvantages to using a foreign currency for a long-term mechanism that will impact UK taxpayers – issues which may be further complicated by the approach to adjusting the thresholds over time (see paragraph 5.24). On the one hand, using dollars per barrel removes the risk of currency fluctuations for businesses, on the other hand, costs for operators in the UK/UKCS are in sterling, therefore currency changes may alter the proportion of gains arising from unusually high prices. The government would welcome stakeholders’ views on this point.

Question 14: Do you agree with the government’s current approach that the threshold for oil should be set in dollars per barrel and that the threshold for gas should be set in pence per therm? In particular, the government would welcome views on what currency the oil threshold should be set.

Factors to consider when setting the thresholds

In order to set appropriate thresholds, the government will consider several factors: backward looking, historical data and forward-looking forecast data (short and long-term price assumptions used by experts, investors, operators, and government organisations). In addition, and in recognition that the UK/UKCS is a maturing basin, the government will also consider the costs involved with operating and investing in upstream oil and gas production in the UK/UKCS.

To note, when looking at data series over time, whether outturn or forecasts, figures can be represented in nominal prices (i.e. the cash paid at the time the relevant commodity was/will be sold) or in constant prices (i.e. the value of the relevant commodity adjusting for inflation). Throughout this consultation, and given the long-term nature of this mechanism, the government will consider constant prices so that the impact of inflation is considered. For the purposes of this consultation, 2024 constant prices will be used, and nominal prices will be converted to constant prices using a US GDP deflator for oil and UK GDP deflator for gas. Once this mechanism has been legislated for, the thresholds for a particular financial year would be announced by the government and specified in nominal terms.

Question 15: Do you have any views on the proposed approach to convert from nominal to constant prices when looking at the data series used to set the thresholds?

Historical oil and gas prices

Historical prices are a form of outturn data. They provide an accurate reflection of oil and gas prices over a period of time. Outturn data also adds a level of transparency and is not subject to speculation.

When considering historical prices, the government will need to consider the ‘look back’ period (i.e. how far back and to what point). This period needs to consider a number of factors. It needs to be sufficiently long so that it captures a broad range of price cycles and to reflect the fact that, as a mature basin, the vast majority of upstream production from the UK/UKCS will derive from investment that has already occurred – so investment decisions were made on the basis of price assumptions in the past. On the other hand, the ‘look back’ period needs to also reflect the modern economic position of upstream oil and gas production.

For the purposes of this analysis, and in line with the approach taken during the development of the ESIM, the data source the government will use for oil is the monthly Brent crude oil nominal dollar price per barrel published by the World Bank (Crude oil, UK Brent 38` API). For gas, the daily day-ahead prices produced by the Independent Commodity Intelligence Service (ICIS) and provided by DESNZ (NBP Price Assessment Day-Ahead Bid/Offer Range Daily Outright (Bid):GBp/th). These figures will then be converted into 2024 constant prices.

Question 16: What are your views on an appropriate ‘look back’ period (and to what date) to consider when analysing historical prices?

Oil and gas price forecasts

Future oil and gas price are impacted by several factors including, but not limited to, global economic activity, global and local production, and storage capacity as well as geo-political conditions. Forecasts provide a snapshot of future price expectation at a given time.

Nonetheless, when operators and lenders make investment decisions relating to upstream oil and gas production in the UK/UKCS, they rely on, amongst other things, oil and gas price forecasts. These come in a variety of forms (e.g. short- and long-term price assumptions - operators and lenders will often refer to these as ‘price decks’). Each operator and lender with use their own price forecasts, as will third party organisations.

Due to the uncertainty associated with forecasting, often, but not always, forecasts will produce a range – referred to as a ‘low’, ‘medium’ (or ‘central’) and ‘high’ price scenario (or assumptions). Whilst there is broad alignment on what may constitute a ‘medium’ or ‘central’ price scenario, there is less alignment on the definitions of a ‘low’ or ‘high’ price scenario. Different organisations use different definitions of extremes to define their different ‘low’ and ‘high’ price scenarios. To control for this, the government is principally focused on understanding the different ‘medium’ price scenarios (or ‘central’ price assumptions) operators, lenders and other stakeholders may use.

Question 17: If you produce oil or gas, what are your ‘medium’ price scenario forecasts (or ‘central’ price assumptions) for both the short and long term? What are the drivers of these assumptions?

What are your ‘high’ price scenario forecasts (or ‘high’ price assumptions) with supporting narrative on the conditions that may trigger this, and the expected likelihood/risk factor used?

If you do not produce oil or gas what are your views on ‘medium’ and ’high’ price assumptions? What is the driver of these assumptions?

Cost of operating and investing in the UK/UKCS

The UK/UKCS is a mature basin. The costs associated with operating and investing in the UK/UKCS are therefore different when compared to other basins. To reflect this, and to ensure that companies are still able to receive a fair share on their investment, the government would like to consider the total project costs when setting the thresholds.

However, the government is also aware that there is a link between costs and the price of oil and gas. As prices increase, more projects become commercially viable. When considering appropriate thresholds, the government will focus on costs associated with projects that would be commercially viable in normal times, as informed by publicly available data and stakeholder’s input.

Question 18: If you produce oil or gas, what is your full cycle average cost per barrel of oil equivalent (BOE)/per therm (as appropriate) in constant (2024) prices for historic projects and future projects and the cost sensitivity of those projects? If you do not produce oil or gas, what are your views on the costs of projects as outlined above?

The government understands the importance of setting the thresholds appropriately, therefore it will consider each factor in the round and their relevance to effectively target gains arising from unusually high prices. The government would also like to work with stakeholders to determine what, if any, factors should hold a greater weight compared to others, and whether there are other factors the government should consider.

Question 19: Do you agree that the government should consider the historical oil and gas prices, oil and gas price forecasts, as well as the cost associated with operating and investing in the UK/UKCS when setting the thresholds? Are there any other factors the government should consider? Should any factor hold greater weight?

How should these factors be used when setting the thresholds

Once the government has established what factors it will consider when setting the thresholds, and the relevance of each one, it will need to determine how to set the thresholds.

So that the mechanism meets its broader policy objectives of minimising the impact on investment and ensuring a fair return for the nation’s resources during times of unusually high prices, the government will set the thresholds above:

-

Average long-term historical price

-

Current central price assumptions

-

Costs associated with operating and investing in the UK/UKCS

Question 20: Do you agree that setting the thresholds using these factors is an appropriate starting point for determining unusually high prices, capturing a fair return of the UK’s resources and ensuring investment is not impacted? If not, what factors, with supporting evidence, would be more appropriate?

How to ensure the thresholds are future proof

The government’s second key objective for the new mechanism is that it will be predictable and provide certainty. It is the government’s desire to design the mechanism in a way that it is future proof. Therefore, it will have pre-determined rules on how the thresholds will be adjusted over time to ensure that the thresholds meet the mechanism’s key objective over the long term. This will ensure operators and investors will have confidence in the fiscal regime in each price scenario.

The purpose of adjusting the thresholds is to ensure that the proportion of profit or excess revenue that is captured by the mechanism as a result of unusually high prices remains constant in real terms from the point that the thresholds are announced.

Early thinking is that these objectives could be achieved by automatically adjusted thresholds on an annual basis using a UK Gross Domestic Product (GDP) deflator. Other deflators have been considered (Consumer Price Index (CPI), Capex/Opex Deflators) but none reflect the economic changes over time as well as a UK GDP deflator. It provides a broad-based measure of price development. However, the government is also aware that using a UK GDP deflator on a threshold priced in dollars may not be appropriate and that GDP figures can be revised after they are first published, so may impact the certainty/confidence the government can give the sector. On the other hand, CPI is a well understood metric by the general population and over the long term aligns closely with the UK GDP deflator. The government would welcome views on this.

For the avoidance of doubt, the adjustment mechanism can increase as well as decrease the thresholds.

There are practical considerations of exactly how to adjust the thresholds (e.g. what data series to use, from what period). The government will work with stakeholders and tax technical experts to work through these details at a later date.

Question 21: Do you agree with the overarching principle of adjusting the threshold?

Question 22: Do you agree that the most appropriate mechanism is a UK GDP deflator? If not, what would be more appropriate? What other challenges do you envisage of using a UK GDP deflator if the oil threshold was set in dollars per barrel?

6. Next Steps

The deadline for responses to this call for evidence is 28 May 2025. Reponses through Smart Survey is preferable. If you would like to provide further details or respond to the call for evidence via email, you can by emailing your response to:

ogpricemechanismconsultation@hmtreasury.gov.uk

If you wish to send a hard copy, this can be sent to:

Oil and Gas Price Mechanism Consultation

Energy and Transport Tax Team

HM Treasury

1 Horse Guards Road

London

SW1A 2HQ

Please mark any commercially sensitive information so that the government can treat that accordingly when it publishes its Summary of Responses.

Paper copies of this document or copies in Welsh and alternative formats (large print, audio and Braille) may be obtained free of charge from the above email address. This document can also be accessed from GOV.UK.

It will not be possible to give substantive replies to individual representations. Where possible, please also provide evidence to support your responses.

7. Equalities

The public sector equality duty came into force in April 2011 (s149 of the Equality Act 2010) and public authorities like HM Treasury are now required, in carrying out their functions, to have due regard to the need to achieve the objectives set out under s149 of the Equality Act 2010 to:

-

eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under the Equality Act 2010;

-

advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it;

-

foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it.

Question 23: If not covered by your answers to other questions, what are in your view the implications of these policy considerations for those who share a protected characteristic? If there are negative impacts, what potential mitigations could be considered?

8. Processing of Personal Data

This section sets out how we will use your personal data and explains your relevant rights under the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR). For the purposes of the UK GDPR, HM Treasury is the data controller for any personal data you provide in response to this consultation.

Data subjects

The personal data we will collect relates to individuals responding to this consultation. These responses will come from a wide group of stakeholders with knowledge of a particular issue.

The personal data we collect

The personal data will be collected through email submissions and are likely to include respondents’ names, email addresses, their job titles, and employers as well as their opinions.

How we will use the personal data

This personal data will only be processed for the purpose of obtaining opinions about government policies, proposals, or an issue of public interest.

Processing of this personal data is necessary to help us understand who has responded to this consultation and, in some cases, contact certain respondents to discuss their response.

HM Treasury will not include any personal data when publishing its response to this consultation.

Lawful basis for processing the personal data

The lawful basis we are relying on to process the personal data is Article 6(1)(e) of the UK GDPR; the processing is necessary for the performance of a task we are carrying out in the public interest. This task is consulting on the development of departmental policies or proposals to help us to develop good effective policies.

Who will have access to the personal data

The personal data will only be made available to those with a legitimate need to see it as part of consultation process.

We sometimes publish consultations in conjunction with other agencies and partner organisations and, when we do this, this will be apparent from the consultation itself. When we these issue joint consultations, your responses will be shared with these partner organisations.

As the personal data is stored on our IT infrastructure, it will be accessible to our IT service providers. They will only process this personal data for our purposes and in fulfilment with the contractual obligations they have with us.

How long we hold the personal data for

We will retain the personal data until work on the consultation is complete.

Your data protection rights

You have the right to:

-

request information about how we process your personal data and request a copy of it.

-

object to the processing of your personal data.

-

request that any inaccuracies in your personal data are rectified without delay.

-

request that your personal data are erased if there is no longer a justification for them to be processed.

-

complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office if you are unhappy with the way in which we have processed your personal data.

How to submit a data subject access request (DSAR)

To request access to your personal data that HM Treasury holds, please email: dsar@hmtreasury.gov.uk

Complaints

If you have concerns about Treasury’s use of your personal data, please contact the Treasury’s Data Protection Officer (DPO) in the first instance at privacy@hmtreasury.gov.uk.

If we are unable to address your concerns to your satisfaction, you can make a complaint to the information commissioner at casework@ico.org.uk or via this website: https://ico.org.uk/make-acomplaint.

Annex A: The Oil and Gas Fiscal Regime

-

The exploration for and production of oil and gas in the UK and on the United Kingdom Continental Shelf (UKCS) is taxed differently to other activities. These activities are treated as a separate trade, ring fenced from other activities, and profits arising are taxed at a higher rate than for other businesses. The fiscal regime has been designed to encourage companies to explore for and develop the UK’s oil and gas resources whilst aiming to ensure that an appropriate share of the benefits accrues to the UK economy as a whole.

-

The current tax regime consists of the temporary EPL and three other permanent elements as outlined below. None of these elements will be considered as part of this consultation and are covered below only to provide context and background information.

-

Ring Fence Corporation Tax (RFCT). This is calculated in broadly the same way as the standard corporation tax applicable to all companies. However, the ring-fence prevents profits from UK and UKCS oil and gas extraction being reduced by losses from other activities. The current rate of RFCT is 30% and is set separately from the rate of mainstream corporation tax (currently 25%).

-

Supplementary Charge (SC). This is an additional charge of a further 10% on a company’s ring-fence profits. The ring-fence profits are adjusted so there is no deduction for finance costs, and companies can benefit from a 62.5% (75% for onshore activity) Investment Allowance on certain expenditure, after their investment starts generating income.

-

Petroleum Revenue Tax (PRT). This is a field-based tax charged on profits arising from oil and gas production from individual oil and gas fields which were given development consent before 16 March 1993. Since 1 January 2016, the rate of PRT has been set permanently to 0% to simplify the tax regime for investors and to ensure those companies who incur losses, especially decommissioning losses, can benefit from the decommissioning relief they are entitled to. . PRT repayments are chargeable to RFCT and SC.

-

Energy Profits Levy (EPL). Introduced in May 2022, the EPL is an additional temporary tax on a company’s ring-fence profits. The levy was implemented in response to extraordinary profits made by oil and gas companies driven by global events, including resurgent demand for energy post COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Set at a rate of 38%, the levy takes the headline rate of tax on upstream oil and gas activities to 78%. The EPL will end in March 2030 or earlier if both oil and gas prices fall to or below prices set out in the Energy Security Investment Mechanism.

Annex B: Summary of Questions

Question 1

What is your name?

Question 2

What is your email address?

Question 3

Which category in the following list best describes you? If you are replying on behalf of a business or representative organisation, please provide the name of the organisation/sector you represent, where your business(es) is located, and an approximate size/number of staff (where applicable).

Question 4

Do you foresee any challenges with using the realised price (rather than market price) as the determinant? If so, please provide further comment on those challenges.

Question 5

If you produce oil or gas, what is your strategic approach to mitigating the risk of price fluctuations? For example, how are different hedging practices and/or other financial instruments used? And what is the extent to which your organisation hedges vs selling at spot price?

If you do not produce oil or gas, what are the strategic approaches to mitigate the risk of price fluctuations that you see in the sector? For example, how are different hedging practices and/or other financial instruments used?

Question 6

Do you envisage any challenges to applying a RBM on a transaction basis? If so, please explain (including an assessment of the additional administrative burden). Linked to this, please provide comments on whether using the first point of sale following extraction as the tax point achieves the right outcome.

If you produce oil or gas, please provide information on how your organisation sells their oil and gas, as well as your record keeping practices.

Question 7

The government would welcome representations on the exceptional costs (above inflationary changes) that companies may experience during unusually high prices. Please provide supporting evidence.

Question 8

The government would welcome your views on the overall design of the PBM.

Question 9

The government would welcome your views on the tax base and definition for adjusted ring fence profits for the PBM.

Question 10

Do you agree that the most appropriate way to account for the different oil and gas markets in a profit calculation is to use a proxy rather than attempt to apportion costs? Please provide additional detail to support your view.

In addition, what proxy would be most appropriate to use?

Question 11

Do you agree that, if possible, the mechanism should utilise the existing CT administrative provisions?

The government would also welcome views on the best approach to administer this new mechanism (as well as an assessment of additional administrative costs), with a view to minimising the administrative burden.

Question 12

Do you agree with the government’s overall assessment that, in comparison with a PBM, a RBM better targets additional gains as a result of unusually high prices? Please provide additional comments to support your view.

Question 13

Do you agree that two thresholds (one for oil and one for gas) are sufficient to effectively administer the new mechanism? If not, please provide detail on the variance between different blends, types and categories of oil and gas, the material impact on project economics as well as how many and which additional thresholds the government should consider.

In particular, how should the thresholds account for NGLs to ensure that the mechanism effectively targets gains arising from unusually high prices?

Question 14

Do you agree with the government’s current approach that the threshold for oil should be set in dollars per barrel and that the threshold for gas should be set in pence per therm? In particular, the government would welcome views on what currency the oil threshold should be set.

Question 15

Do you have any views on the proposed approach to convert from nominal to constant prices when looking at the data series used to set the thresholds?

Question 16

What are your views on an appropriate ‘look back’ period to consider when analysing historical prices?

Question 17

If you produce oil or gas, what are your ‘medium’ price scenario forecasts (or ‘central’ price assumptions) for both the short and long term? What are the drivers of these assumptions?

What are your ‘high’ price scenario forecasts (or ‘high’ price assumptions) with supporting narrative on the conditions that may trigger this, and the expected likelihood/risk factor used?

If you do not produce oil or gas what are your views on ‘medium’ and ‘high’ price assumptions? What is the driver of these assumptions?

Question 18

If you produce oil or gas, what are your total average cost per barrel of oil equivalent (BOE)/per therm (as appropriate) in constant (2024) prices for historic projects and future projects and the cost sensitivity of those projects?

If you do not produce oil or gas, what are your views on the costs of projects as outlined above?

Question 19

Do you agree that the government should consider the historical oil and gas prices, oil and gas price forecasts, as well as the cost associated with operating and investing in the UK/UKCS when setting the thresholds? Are there any other factors the government should consider? Should any factor hold greater weight?