Police powers: pre-charge bail government response (accessible version)

Updated 6 September 2021

Foreword by the Home Secretary

This Government is committed to ensuring the police have the powers they need to protect victims of crime. We have listened to what you have said in the consultation and we are taking action to place the welfare and interests of victims at the heart of the criminal justice system.

Pre-charge bail is an important tool. It allows the police to reduce the risk of harm to victims and witnesses by setting robust and proportionate conditions on those under investigation and supports the timely progression of investigations.

We passionately believe that victims should have a voice in the pre-charge bail system. It is vital that victims are included in the process that is designed to keep them safe from harm. We will be ensuring that the police listen to victims and help them to understand the bail conditions when they are set and varied throughout the pre-charge bail process.

Pre-charge bail is one part of a much bigger system which we are continually trying to improve. We are determined to provide police with the powers they need to secure justice for victims efficiently. The removal of the presumption against bail and the amended legislative framework for timescales around bail, will assist the operational reality of modern policing investigations.

This document sets out a summary of the responses to the consultation and the Government’s proposals to reform the law in this area, which will need to be taken forward in Parliament.

Rt Hon Priti Patel MP

Home Secretary

Introduction

This document is the post-consultation report for the consultation paper, Police Powers: Pre-charge Bail.

It will cover:

- introduction: Government approach

- the background to the consultation

- a summary of the consultation responses

- a detailed response to the specific questions raised in the consultation and

- the next steps following this consultation.

Further copies of this report and the consultation paper can be obtained from the consultation outcome Police powers: pre-charge bail.

An individual who has been arrested by the police but who has not yet been charged can be released on pre-charge bail, with or without conditions, or released without bail while the investigation continues.

Individuals on pre-charge bail are required to return to the police station at a specified date and time, known as ‘answering bail’, to either be informed of a final decision on their case or to be given an update on the progress of the investigation.

Conditions may be imposed upon the individual if they are deemed necessary to: prevent someone from failing to surrender to custody, prevent further offending, prevent someone from interfering with witnesses, or otherwise obstructing the course of justice. Conditions may also be imposed for the individual’s own protection or, if aged under 18, for their own welfare and interests.

The Government legislated through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 to address concerns that individuals were being kept on pre-charge bail for long periods, sometimes with strict conditions.

The reforms introduced:

- a presumption against pre-charge bail unless necessary and proportionate; and

- clear statutory timescales and processes for the initial imposition and extension of bail, including the introduction of judicial oversight for the extension of pre-charge bail beyond three months.

Since the reforms came into force, the use of pre-charge bail has fallen, mirrored by an increasing number of individuals ‘released under investigation’ or RUI. This change has raised concerns that bail is not always being used when appropriate, including to prevent individuals from committing an offence whilst on bail or interfering with victims and witnesses. Other concerns focus on the potential for longer investigations in cases where bail is not used and the adverse impact on the courts.

The Government committed to reviewing this process to consider whether further change is needed to ensure that bail is being used where appropriate and to support the police in the timely progression of investigations. As a result of the consultation process, a number of proposals will be taken forward to ensure the bail regime is proportionate and effective. Where legislation is required to give effect to these proposals, as set out in this document, this will be taken forward in the current parliamentary sitting.

As part of the wider review into pre-charge bail, the Government has also undertaken a review of the research literature which will be published alongside this report. The Government has considered HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services’ (HMICFRS) thematic inspection into pre-charge bail and released under investigation; and HMICFRS’ inspection into the super-complaint made by the Centre for Women’s Justice into ‘Police failure to use protective measures in cases involving violence against women and girls’.

Background

The consultation paper Police Powers: Pre-charge Bail was published on 5 February 2020. It invited comments on the timescales and criteria for pre-charge bail, the effectiveness of bail conditions as well as non-bail investigations.

The consultation period closed on 29 May 2020 and this report summarises the responses, including how the consultation process influenced the final development of the proposals consulted upon.

A Welsh Language copy can be found in the consultation outcome Police powers: pre-charge bail.

A breakdown of respondents is at Annex A.

The consultation asked 13 questions covering six topics:

- Criteria for pre-charge bail;

- Timescales for pre-charge bail;

- Non-bail investigations;

- Effectiveness of bail conditions;

- Other Issues; and

- Your experience.

Summary of responses

A total of 844 responses to the consultation paper were received. 780 responses were submitted through the online form, 63 were received via email and 1 response was received by post.

Please note not all respondents answered every question and due to rounding, some of the tables will have percentage totals above 100%.

The responses were analysed and identified as belonging to different sectoral groups by the respondents’ self-declaration. The below table shows the breakdown of the biggest sectoral groups. The category of ‘Others’ contains other sectors that had minimal responses, including law enforcement agencies such as HM Revenue and Customs; academics; and other government bodies such as local authorities and Police and Crime Commissioners. This analysis has been used to find the levels of support among sectors for the proposals in the consultation. A smaller subgroup made up of members of the public, who had referenced being under investigation in their responses, was also used.

| Sector | Percentage of total responses |

|---|---|

| Police Force (Police) | 64 |

| Members of the Public (MOP) | 21 |

| Charity sector (Charities) | 5 |

| Legal profession and services (Lawyers) | 3 |

| Others | 7 |

There was generally high agreement across most categories for longer bail timeframes, removal of the presumption against bail and use of specific risk-based factors. Notably, members of the public who had been investigated and lawyers were less supportive of the longest timeframes of bail.

Criteria for pre-charge bail

Background

To address concerns about individuals being placed on pre-charge bail for long periods, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced a presumption against pre-charge bail unless its application is considered both necessary and proportionate in all the circumstances. This point is also reinforced by guidance released by the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC), which stresses the need to consider bail in high harm[footnote 1] cases. The Government has been clear that it fully supports the use of pre-charge bail.

However, following discussions with the police and other stakeholders, the Government has become increasingly concerned that pre-charge bail is not being used in cases where it may be necessary and the process of ‘released under investigation’ (RUI) is being used in its place. This gives rise to a number of issues as conditions cannot be placed on the suspect and police officers using RUI are not subject to the same level of accountability around decision-making, timescales, notification to the suspect, victims and witnesses.

Proposal

Proposal 1: The Government proposes legislating:(i) to end the presumption against pre-charge bail, instead requiring pre-charge bail to be used where it is necessary and proportionate and (ii) to add a requirement that a custody officer must have regard to the following factors when considering whether application of pre-charge bail is necessary and proportionate:

- The severity of the actual, potential or intended impact of the offence;

- The need to safeguard victims of crime and witnesses, taking into account their vulnerability;

- The need to prevent further offending;

- The need to manage risks of a suspect absconding; and

- The need to manage risks to the public The Government believes the bail system should assist the police to make risk-based decisions, and to use their experience to consider the application of pre-charge bail on a case by case basis, rather than being required to apply bail for specific offences or in all cases.

Questions

Four questions were asked in this section. Questions 1-3 were closed questions and Question 4 was a free text option.

Q1. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the general presumption against pre-charge bail should be removed?

| Answer | Response % | Total Response |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 65 | 530 |

| Agree | 17 | 142 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 3 | 27 |

| Disagree | 7 | 54 |

| Strongly disagree | 8 | 68 |

| Total who responded to this question | 100 | 821 |

82% (672) of respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the proposal to end the presumption against pre-charge bail, 15% (122) of respondents strongly disagreed or disagreed. There was high level agreement across all categories of respondent that the presumption should be removed. The strongest support was among the police at 84% (452), and other enforcement bodies at 86% (6).

Q2. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the application of pre-charge bail should have due regard to specific risk-factors?

| Answer | Response % | Total Response |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 46 | 370 |

| Agree | 40 | 322 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 6 | 46 |

| Disagree | 6 | 46 |

| Strongly disagree | 3 | 26 |

| Total who responded to this question | 100* | 810 |

*Owing to rounding the total percentage who responded does not add up to 100

The majority of respondents agreed with the requirement for the police to have regard to specific risk factors when making bail decisions, with 86% (692) responses strongly agreeing or agreeing. This positive response was seen across all categories of respondent.

Q3. To what extent do you agree/disagree that the application of pre-charge bail should consider the following risk factors:

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. The severity of the actual, potential or intended impact of the offence (n=811) | 60 | 27 | 6 | 4 | 3 |

| b. The need to safeguard victims and witnesses, taking into account their vulnerability (n=811) | 82 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| c. The need to prevent further offending (n=810) | 69 | 23 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| d. The need to manage risks of a suspect absconding (n=810) | 63 | 30 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| e. The need to manage risks to the public (n=808) | 75 | 19 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

There was again strong agreement across all categories of respondent that the application of pre-charge bail should use the above risk factors. There was particularly strong support for risk factors (b) and (e) emphasising that bail should be used to safeguard victims and protect the public.

Q4. Do you have any other comments? For example, are there any other risk-factors we should consider? Or any comments on the discounted approaches outlined in the consultation proposal?

Out of 844 responses to the consultation, 43% (363) of respondents provided a comment to this question. The most common response at 24% (86) reiterated support for the removal of the presumption against bail or a presumption of bail to be introduced. Key stakeholders suggested any risk decisions should be based on strong evidence of the risk. A significant minority of 12% (45) suggested an emphasis should be placed on protecting children and vulnerable victims.

Conclusions and next steps

The Government acknowledges that the changes brought in by the Policing and Crime Act 2017, which introduced the presumption against using pre-charge bail, has had a number of knock-on effects within the criminal justice system. Whilst it achieved its aim of introducing safeguards for suspects who were being placed on bail for lengthy periods, it has inadvertently led to an increase in the number of people who are ‘released under investigation’ (RUI). Use of RUI has meant that there are suspects who are still under investigation for lengthy periods, but not subject to the oversight and reporting requirements that they would have under pre-charge bail.

Victims are also affected by the use of RUI, as there is no mechanism enabling suspects released under investigation to be subject to conditions, which can lead victims to feel less protected by the police. The Government is committed to ensuring that victims are well-supported by the pre-charge bail system and that the system operates as effectively as possible, with proportionate use of conditions, balanced against the need to safeguard victims.

The Government aims to legislate to remove the presumption against the use of pre-charge bail and to make it easier to use bail in cases where it is necessary and proportionate. This will create a neutral position within legislation so that there is neither a presumption for nor against pre-charge bail. Decisions on bail will continue to be made with reference to whether such a decision is necessary and proportionate on a case by case basis.

The Government has listened to those in favour of introducing a need to consider risk factors when deciding on whether to place a suspect on bail and are considering how best to incorporate these into the framework. This will be designed to aid the police in making risk-based decisions which place an emphasis on the protection of victims, witnesses and the suspect themselves.

Timescales for pre-charge bail

Background

To address the issue of individuals being under investigation for long periods, sometimes with strict bail conditions, the Policing and Crime Act 2017 introduced:

- An initial 28-day limit to the use of pre-charge bail authorised by an inspector; with subsequent extensions up to 3 months and beyond to be authorised by senior officers (superintendents or above) and magistrates, respectively; and

- A requirement for senior officers and magistrates to authorise extensions to bail only if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting the individual under investigation to be guilty. The senior officer/court must also have reasonable grounds for believing that: further time is needed to make a charging decision or further investigation is needed; the decision to charge is being made, or the investigation is being conducted, diligently and expeditiously; and the use of pre-charge bail is necessary and proportionate in all the circumstances.

Feedback from policing stakeholders has highlighted that these changes have disincentivised the use of bail, especially in complex cases which require further investigation and can be difficult to progress and/or conclude in 28 days. There were concerns that the current system is operationally unrealistic. Home Office data,[footnote 2] [footnote 3] from published statistical bulletins on crime outcomes for those offences where pre-charge bail might be more commonly applied, suggest cases do take longer than the 28-day limit, which corroborates the concerns raised by stakeholders.

Proposal

The Government proposed legislating to amend the statutory framework governing pre-charge bail timescales and authorisations and sought views on three potential models.

| Current Model | Model A | Model B | Model C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Bail Period | To 28 days, Inspector | To two months, Custody Officer | To three months, Custody Officer | To three months, Custody Officer |

| First extension | To three months, Superintendent | To four months, Inspector | To six months, Inspector | To six months, Inspector |

| Second extension | Beyond three months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | To six months, Superintendent | To nine months, Superintendent | To nine months, Superintendent |

| Third extension | As above. | Beyond six months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | Beyond nine months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) | To 12 months, Superintendent |

| Fourth extension | As above. | As above. | As above. | Beyond 12 months, Magistrate (at three-month extension intervals) |

All three models propose:

- restoring the initial bail authorisation to custody officers given both their independence from investigations and their experience in making risk-based decisions;

- introducing additional points at which the investigation including the use of pre-charge bail will be reviewed;

- maintaining an initial bail period - but increasing its length; and

- maintaining judicial oversight but changing the point at which judicial oversight of authorisations is introduced.

Of the proposed models, all three will provide enough time for most low level and drug offences to be concluded within the first bail extension. Model A will require frequent authorisations by a magistrate thereafter and Model B and C will capture most crimes requiring judicial oversight for the more complex and serious offences.

Questions

Two questions were asked in this section. Question 5 was a closed question and Question 6 was a free text question.

Q5: Please rank the options below in order of preference (1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th).

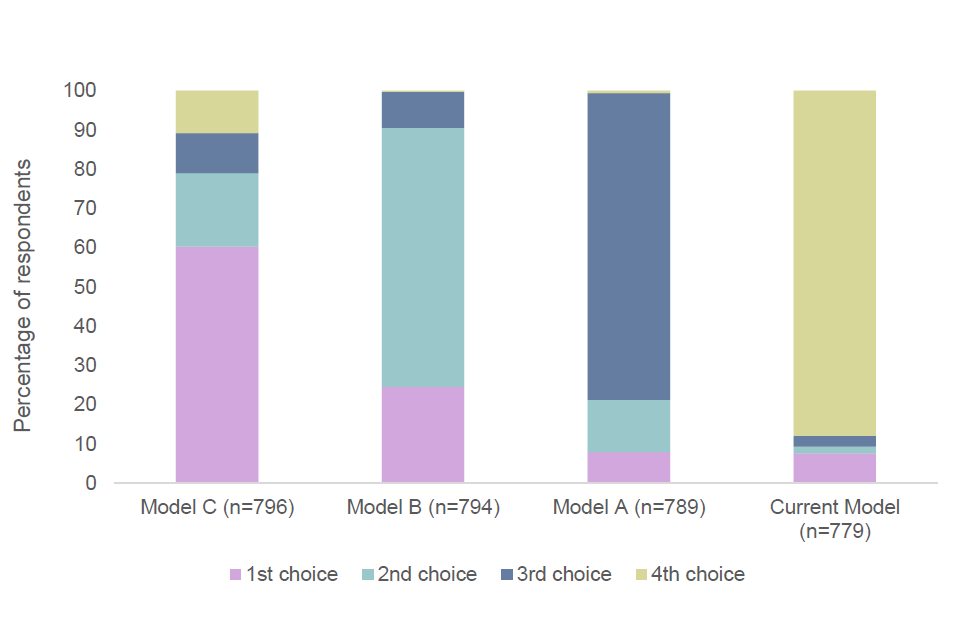

A stacked bar chart showing the percentage of respondents who chose each option as their 1st, 2nd, 3rd or fourth choice.

Model C received the most first preference votes across most sectors including the police. Both Model A and the Current Model were far less popular. There were some differences in how the sector categories ranked the models. The table below outlines the most and least desirable models of each sector.

| Sector | Most Desirable Model | Least Desirable Model |

|---|---|---|

| Police | Model C | Current Model |

| Members of the Public | Model C | Current Model |

| Law Enforcement Bodies | Model C | Current Model |

| Charities | Model C | Current Model |

| Other Government Bodies | Model B | Model C |

| Members of the Public who had been under investigation | Current Model | Model C |

| Lawyers | Current Model/Model B | Model C |

| Academics | All models equally | All models equally |

Combining the first and second preference votes to see which model receives broadest support, Model B becomes the most popular.

| Preference order | Current Model | Model A | Model B | Model C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined 1st and 2nd | 73 | 168 | 719 | 629 |

When looking at combined first and second preferences, the only sector which did not show strong support for Model B are members of the public who had been under investigation, who favoured the current model, and lawyers, who showed equal preference for Models A and B.

Q6. Do you have any other comments? For example, do you have a different proposal or are there circumstances in which the proposed timescales would not be appropriate?

Out of 844 responses to the consultation, 260 (31%) provided an answer to this question. The comments generally covered three areas of concern:

- ‘Investigations take too long/cause further delays’- These comments suggested modern investigatory methods take time (especially if digital forensics form part of the investigation). They suggested even simple/minor investigations will always require an initial extension. Excessive workloads and delays can occur e.g. waiting for a charging decision which mean it is inevitable investigations will take longer. Some expressed the view that judicial oversight is needed to hold police officers accountable and ensure that they will commit limited resources to investigate.

- ‘Authorisation and internal supervision of extensions’- There was concern that senior officers are already involved in a number of other duties and will not have the capacity to authorise the level of custody extensions expected.

- ‘Court Oversight’ – Concerns were raised that Magistrates’ Courts may not have the capacity and sufficient knowledge of police investigations to make realistic assessments on the progress of investigations. A similar point was also raised that courts will be subject to a huge increase in bail considerations if the timescales and authorisation levels were not amended accordingly. There was concern about the bureaucracy involved in applying for extensions from court and that law enforcement should be able to appeal magistrates’ decisions on bail.

Conclusions and next steps

Model B attracted the broadest support amongst the widest variety of groups when considering all preferences and the Government intends to legislate to implement this model. This takes into consideration the need to balance the views of all those who responded to the consultation with the operational practicalities of the system.

The Government recognises that the existing timescales and authorisation levels are not suitable in that they do not properly reflect the operational realities faced by the police and other law enforcement bodies. The majority of police investigations require longer than the existing applicable bail period (ABP) of 28 days, and it is right that we recognise this by adjusting the timescales. There has been a huge burden placed on Superintendents who are currently required to approve bail extensions should the investigation exceed 28 days, which is common. We agree with the views expressed in the consultation and think it is unwise to overburden Superintendents with bail approvals whilst they are juggling many other operational responsibilities.

Our intention is to legislate to put Model B on a statutory footing, which will provide more proportionate timescales and levels of authorisation that will recognise these operational realities. The decision for approving the initial bail period will be made by the custody officer, who has the necessary skills and experience in making risk-based decisions, as well as the independence from the investigation itself. Where it is necessary to extend bail, this will be decided by an Inspector at the 3-month stage and any further extensions will be approved by a Superintendent at the 6-month stage. This will share out the administrative burden of extending bail periods and balances the need for swift and effective investigations against the practical difficulties of completing investigations within short timeframes. The new model will continue to provide independent judicial oversight of the bail system through the Magistrates’ Court, which will authorise any extensions beyond 9 months, or beyond twelve months in particularly complex cases. This will ensure that the court is not overburdened with extensions at an early stage in the process but will still provide much-needed oversight of the bail regime.

The Government also recognises that other law enforcement agencies – namely the Serious Fraud Office (SFO), Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), National Crime Agency (NCA), and HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) – are also affected by changes in pre-charge bail legislation. Consultation responses highlighted that many of their investigations can be far lengthier and more complex than standard police cases. Taking this into account, the Government aims to create timescales within legislation for these agencies that will reflect the nature of their investigations whilst ensuring that there is sufficient oversight within the system.

Non-bail investigations

Background

Prior to the 2017 reforms, all individuals released after arrest while investigations continued were released on pre-charge bail, with or without conditions. A side effect of these reforms was the rise in the use of the police process known as “released under investigation” or RUI as well as a rise in other non-bail investigations.

Not all individuals on RUI have been arrested. It has become increasingly common for individuals to be interviewed voluntarily. This is known as Voluntary Attendance (VA). We therefore use the terminology “non-bail” to refer to investigations when pre-charge bail is not used, including cases where the individual may not have been arrested but is still under investigation.

RUI and other non-bail investigations are not subject to the same statutory framework as pre-charge bail. This means there are no timescales or oversight set out in legislation.

A number of stakeholders have raised concerns that the increased use of RUI has had two major impacts:

- Longer investigations: The police do not have fixed dates to update individuals, victims and witnesses on the progression of their investigations, and there are no legal requirements governing timescales, unlike with bail. It is important to note that there are a number of other factors at play which can lead to longer police investigations, including resourcing and digital evidence.

- Delays to courts: As individuals on RUI are not required to return to a police station for a charging decision, they are instead charged via post known as a “postal charge and requisition” (PCR). Individuals who fail to respond to their PCR, either intentionally or due to issues with their address, are therefore failing to turn up to court for their hearing, known as ‘failure to attend’ (FTA). FTA is an offence for which a magistrate can issue a warrant so the police may arrest the individual and bring them to court. An increase in the rate of FTA offences creates delays in the progression of cases to court, increased costs to court, increased costs to the police and decreased likelihood of prosecution.

There are also concerns regarding the use of RUI, given that the regime does not enable conditions to be attached to the individual’s release. This may mean that victims and witnesses are less protected under the RUI process than they would be if the individual was on bail.

The National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) have sought to address the lack of statutory oversight of RUI by issuing guidance that recommends supervisory reviews of RUI cases every 30 days, regular updates to victims and individuals, and the setting of target investigation end dates.

Proposal

In the consultation the Government proposed a new framework for the supervision of RUI and VA cases. We proposed that the framework would mirror the timescales already in place for pre-charge bail and any changes that may have been made to those timescales as a result of the review. The proposed framework had set review points and did not put a limit on the length of police investigations, and reviews would have been carried out by the police and not been subject to judicial oversight. Individuals on RUI and VA would not have been subject to conditions. The framework would have been set out in codes of practice.

Questions

Two questions were asked in this section. Question 7 was a closed question and Question 8 was a free text question.

Q7. To what extent do you agree/ disagree that there should be timescales in codes of practice around the supervision of ‘released under investigation’ and voluntary attendance cases?

| Answer | Response % | Total Response |

|---|---|---|

| Strongly agree | 34 | 272 |

| Agree | 35 | 282 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 9 | 73 |

| Disagree | 12 | 94 |

| Strongly disagree | 11 | 85 |

| Total who responded | 100* | 806 |

*Owing to rounding the total percentage who responded does not add up to 100.

There was high level agreement at 69% (554) that there should be timescales incorporated into a code of practice for RUI and VA cases. This agreement was represented across all sectors.

Q8. Do you have any other comments? For example, if you disagree, do you have alternative proposals for the supervision of ‘released under investigation’ and voluntary attendance cases?

34% (288) of respondents provided an answer to this question. There was a minority of 12% (34) who viewed RUI as pointless and as a weak alternative to bail. They felt that time limits will not address the underlying reasons that result in investigations taking long periods of time. The other view presented was that time limits are fairer allowing suspects and defence solicitors to plan accordingly with 37% (106) of respondents supporting an introduction of timeframes for RUI investigations. There was a common theme that RUI use will decrease after wider reforms to bail have been made.

Another issue raised was the postal requisition of suspects where they had no fixed abode. The Government is aware of the concern that when a suspect is not bailed there can be issues in sending a charging decision through the post, which adds cost and delays into the justice system.

Conclusions and next steps

The Government acknowledges the strong agreement expressed about non-bail investigations which related to the lack of rationale for the existence of RUI and the lack of a statutory framework for non-bail investigations. The Government agrees that RUI is an unsatisfactory process which does not provide the necessary level of accountability around decision-making, communication with the suspect, victims and witnesses, and timescales for completing the investigation. On top of this, there are no conditions attached to RUI cases which can lead to victims being inadequately protected by the regime.

Given the Government’s intention to remove the presumption against bail, we expect the use of RUI to drop significantly following these reforms. Decision-makers will be able to set bail, with reference to the necessary and proportionate criteria and the risk factors set out in guidance, either with or without conditions. If individuals do not meet these criteria, it is likely that no further action is the most appropriate course to take. As we expect the use of RUI to decline, we will not be introducing timescales into the RUI process and instead will work with the sector to limit the use of RUI going forward.

In terms of other non-bail investigations, our intention is to work with policing partners on guidance on the voluntary attendance (VA) scheme to ensure that it is being used in an effective and proportionate manner. Further non-legislative proposals will be worked up in longer time with regard to postal requisition.

Effectiveness of bail conditions

Background

Individuals released from police custody on pre-charge bail may be subject to conditions, for example, prohibiting them from contacting the victim. Applying bail conditions means that the police can effectively manage a suspect within the community while the investigation progresses.

There are two ways pre-charge bail can be infringed: failing to answer pre-charge bail; and breaching pre-charge bail conditions.

Failure to answer court bail (i.e. to return to the police station) is a criminal offence. When an individual on pre-charge bail fails to answer, they can be arrested on suspicion of committing a criminal offence under section 6 of the Bail Act 1976, which carries a maximum three-month sentence of imprisonment or a fine on conviction. There is no equivalent for pre-charge bail.

If an individual breaches their conditions of pre-charge bail, they can be arrested and taken to the police station. A breach of pre-charge bail conditions is not a criminal offence, although the breach itself may amount to a separate offence. For example, contacting a witness may also be an offence under the Protection from Harassment Act 1997. More commonly, the individual is brought into custody only to be re-released on pre-charge bail with the same conditions as previously set.

Stakeholders have raised concerns with the Home Office that the lack of criminal penalty associated with breaching bail conditions may have negative consequences on victims and witnesses, the public and the criminal justice system. To understand these issues in more detail, we sought views on the effectiveness of bail conditions.

Proposal

There was no specific proposal the Government was seeking views of respondents on, but rather a more wide-ranging question on bail conditions.

Questions

Two questions were asked in this section. Question 9 was a closed and Question 10 was free text.

Q9. To what extent do you agree/disagree that pre-charge bail conditions could be made more effective:

| Strongly agree | Agree | Neither agree nor disagree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a.to prevent someone interfering with victims and witnesses? (n=830) | 80 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| b. to prevent someone committing an offence while on bail? (n=827) | 72 | 18 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| c. to prevent someone failing to surrender to custody? (n=829) | 66 | 21 | 8 | 3 | 2 |

All sectors excluding academics expressed strong agreement that bail conditions need to be more effective in each of the objectives of pre-charge bail. Academics were equally split between agreement and disagreement. Strongest agreement again was in support of using bail to provide greater protection for witnesses and victims.

Q10. What could be done to make bail conditions more effective?

55% (468) of respondents answered this question. Of those 81% (377) of responses supported introducing an offence or punishment for breach of bail conditions. 3% (13) including key stakeholders in the criminal justice system expressed a view that breach of bail conditions should not be made an offence.

The question received strong representations from a range of respondents, including victim’s support groups, charities and former and currently serving police officers, expressing support for introducing measures that will make a breach of pre-charge bail conditions a criminal offence. The support for such a measure largely stems from pre-charge bail conditions being perceived as ineffective as the police do not have powers to enforce them unless a suspect is arrested and charged with a separate offence, such as intimidation of a witness.

However, in response to the same question, legal professionals and members of the judiciary expressed concern over breach of pre-charge bail conditions being made a criminal offence. Creation of a criminal offence could suggest that bail is designed to be punitive and may lead to over-criminalisation of suspects; additionally, it could cause inconsistency in the system as breach of post-charge bail is not a criminal offence.

Conclusions and next steps

The Government acknowledges the strong support for strengthening the consequences for breaches of pre-charge bail conditions. However, having worked through the likely impact of the creation of a separate offence for breach of pre-charge bail conditions, the Government has assessed that this is not currently a workable legislative option. However, the Government is keeping this issue under review and seeking to improve data collection in this area to better understand the issue and what actions may be appropriate

We do acknowledge the feedback that we have received to the effect that the current system does not provide the police with an effective deterrent to prevent breaches of bail conditions and protect the public, nor does it offer enough protection to victims and witnesses. The Government is proposing that, as part of the pre-charge bail process, victims are helped to understand any pre-charge bail conditions that are set in their case, how these will assist in keeping them safe from further harm and are given an opportunity to raise their views. It is right that victims should feel safe and protected by the bail system.

Other issues and your experience

The final 3 questions were free text questions.

Questions

Q11. Are there any other issues or proposals you would like to raise with us in relation to the use of pre-charge bail or released under investigation?

Out of 844 responses to the consultation, 33% (276) responded to this question. Many repeated issues or comments raised in previous questions and a few responses raised similar points.

Several respondents raised issues around RUI. Of those that responded, 7% (19) wanted RUI abolished, 9% (25) wanted RUI reformed and 5% (13) raised concerns with postal requisitions systems for suspects when RUI is used. Consideration of victims was also mentioned with 12% (34) of respondents raising issues on victims’ rights and wanting to give them more consideration within the framework.

11% (30) of respondents expressed a view that breach of bail conditions should have some form of formal sanction. 10% (28) respondents expressed a desire for better guidance, training and funding to improve the use of pre-charge bail/RUI and improve investigation times. A small minority of 8% (21) expressed frustration at delays caused by the CPS and 5% (14) were critical of the changes brought in by the Policing and Crime Act 2017.

Q12. How have you been personally affected by ‘pre-charge bail’ or ‘released under investigation’?

None of the respondents answered this question.

Q13. If you have been affected, how do you think the system could be improved?

Out of 844 responses to the consultation, 10% (86) of respondents answered this question. Many repeated issues raised in previous questions and no overarching themes were common across responses. The most common opinion expressed was that investigations should be conducted more quickly, with 20% (17) expressing the view that current timeframes are too long. Respondents also suggested: a presumption of using pre-charge bail 15% (13), improved working between criminal justice organisations 15% (13) and that there should be consequences for breaching PCB conditions 12% (10).

Conclusions and next steps

A significant minority of responses indicated a frustration at how the 2017 changes to the bail system were implemented, with criticism of the level of training and guidance provided to law enforcement at the time. The Government is committed to learning lessons from the implementation of the 2017 reforms and will work with policing stakeholders and other interested parties to ensure that the implementation of any new reforms is completed in conjunction with adequate training and guidance.

A common theme across multiple questions and responses was the level of information-sharing in relation to victims and vulnerable people. The Government is considering available options for greater information-sharing amongst forces and organisations. This includes developing guidance and training for police and other branches of Government to share and capitalise on best practice in this area.

The Government will seek to bring the legislative changes outlined above in a Bill before Parliament at the earliest opportunity in 2021. New guidance will be issued to assist with the implementation of these changes in due course.

Consultation principles

The principles that Government departments and other public bodies should adopt for engaging stakeholders when developing policy and legislation are set out in the Cabinet Office Consultation Principles 2018.

Annex A – Breakdown of respondents by type

| Answer | Number of responses received | Percentage of responses |

|---|---|---|

| Academics | 4 | 1% |

| Charities and Victim Services | 45 | 5% |

| Lawyers and Judiciary | 23 | 3% |

| Members of the Public | 205 | 24% |

| Other Governmental Bodies | 18 | 2% |

| Other Law Enforcement Agencies | 7 | 1% |

| Police Forces and Police Officers | 545 | 64% |

-

Cases where the offences incur significant adverse impacts, whether physical, emotional or financial, upon individuals or the wider community. ↩

-

Police data available from the Home Office Data Hub cover date of crime recording and date an outcome is recorded for that crime. The time between these two dates can be considered investigation time, though the data is not able to identify specifically those cases where pre-charge bail was applied. ↩

-

Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2017 to 2018; Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2018 to 2019; Crime outcomes in England and Wales 2019 to 2020. ↩