Police powers: pre-charge bail overview of the evidence (accessible version)

Updated 6 September 2021

Scarlett Furlong, Victoria Richardson and Andy Feist

January 2021

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Richard Martin (Assistant Professor of Law at the London School of Economics and Political Science), Professor Anthea Hucklesby (Professor of Criminal Justice and Head of the School of Social Policy at the University of Birmingham), and Professor Mandy Burton (Professor of Socio-Legal Studies at the University of Leicester), for peer reviewing this report.

Executive summary

Introduction

The police in England and Wales can grant pre-charge bail (PCB), also known as police bail, to individuals arrested on suspicion of a criminal offence but where there are no grounds to keep them in detention while the investigation continues. At this stage there is insufficient evidence to charge.

The main purposes of PCB can be summarised under three headings: − The protection of victims and witnesses, primarily linked to conditions applied to PCB such as no contact with the victim. − Investigative management, allowing investigations to progress to obtain evidence. − Suspect management, including reducing the risk of re-offending.

PCB was subjected to legislative change through the Policing and Crime Act (PCA) 2017. The changes were principally the result of concerns that suspects were spending extended periods of time on PCB, often for the case against that suspect not to be taken forward.

The PCA reforms – which created a presumption against the use of police bail – resulted in a precipitous drop in using PCB in the year after their introduction, mirrored by an increasing number of individuals being ‘released under investigation’ (RUI). The decreased use of PCB has led to various criticisms, particularly around weakened investigative management, less information for suspects regarding the progress of their case, and weaker protections for victims and witnesses.

The Home Office committed to reviewing the PCB and RUI process to consider whether further change will ensure that bail is being used where appropriate and to support the police in the timely progression of investigations. To help inform this work, this evidence review seeks to address the following issues: (1) what data exists on the use and nature of PCB; and (2) what impact have the 2017 reforms had on the use of PCB in England and Wales. The evidence review also explores the very limited evidence base on the effectiveness of PCB. It is based on a structured evidence-gathering exercise of published and forthcoming research literature, and data from a range of sources.

The use and nature of pre-charge bail

Limited published research exists on PCB before the reforms in 2017. Most studies have found that around one-third of suspects arrested were placed on PCB in the years before 2017. Other analysis suggests it might be closer to two-fifths. Studies have also found that substantial proportions of bailed suspects are ultimately not charged, with nearly half of cases in studies by both Hucklesby (2015) and Phillips and Brown (1998) resulting in no further action (NFA).

Hucklesby’s (2015) detailed two-force study found that while the ethnicity of bailed suspects broadly reflects the profile of those arrested, White European suspects were more likely to be charged than those from other ethnic groups. In contrast, bailed suspects from black and minority ethnic backgrounds were more likely to have their cases end in NFA.

There is very limited information on the frequency and type of conditions imposed through PCB, the rationale behind their imposition or the extent of breaches. Hucklesby (2015) found vastly different approaches towards imposing conditions in her two study forces prior to the reforms, with one force not using conditions at all, and the other applying conditions in two-thirds of PCB cases. ‘Banning’ conditions, i.e. keeping away from people and places, were those most frequently applied.

Based on Freedom of Information (FOI) responses from 29 forces in England and Wales, analysis by The Law Society covering the period before and after the change in legislation provides some evidence of the impact to the 2017 reforms. For a sub-set of 27 forces, in the 12 months following the reforms, the number of suspects on PCB dropped by around 85%, from approximately 190,000 to 29,000. Home Office data show that PCB numbers started to recover in the second year after the reforms. Figures for the same 27 forces show use of PCB increased by 106% to approximately 60,500 in the year ending March 2019, and a further 92% in the year ending March 2020 to approximately 115,800.[footnote 1] However, these data suggest that PCB remains well below pre-reform levels.

It is generally believed that the modest recovery in PCB volumes in 2018/19 and 2019/20 is linked to concerns around the police’s response to the reforms raised initially by HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS, 2018), and the police service’s response to the publication of the National Police Chiefs’ Council’s (NPCC) guidance on usage in 2019.

After the reforms and the creation of the presumption against PCB, individuals were increasingly RUI. The Law Society FOI analysis suggests that there was a clear shift from releasing individuals on PCB to RUI. In 2017/18, approximately 177,000 individuals were RUI in the 29 forces in England and Wales that responded to the FOI.

Post reform, a substantial proportion of individuals released on PCB for the first 28 days have their post release status changed to RUI thereafter. This adds to the complexity of measuring PCB and RUI volumes in the post-reform landscape.

Force-level variations

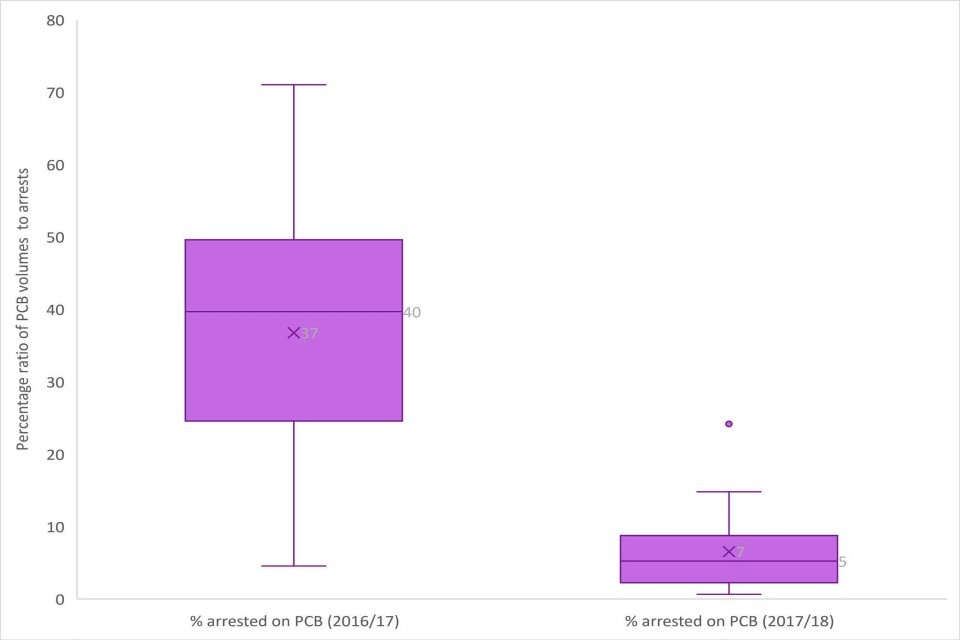

Force-level data indicate a wide variation in the use of PCB in the year before the reforms. Comparing PCB use against arrest volumes (28 forces), seven forces had a PCB to arrest ratio of 50% or above in 2016/17, while six forces recorded ratios below 20%.[footnote 2]

In the year following the reforms – for the same sample of forces – eight forces had a PCB to arrest ratio of below 2%, while six forces had ratios above 10%. While almost all forces saw marked reductions in the proportion of arrestees who were subject to PCB in the wake of the reforms, some virtually abandoned using PCB altogether, while other forces maintained use at a moderate rate.

Impact of the decreased use of PCB and the increased use of RUI following the 2017 reforms

The large-scale reduction in the use of PCB, especially immediately after the reforms, has raised concerns about the impact on victims, witnesses, suspects and the wider criminal justice system (CJS) process. There were particular concerns that those suspected of serious offences – violent and sexual offences, and those involving repeat offenders – were RUI rather than granted PCB, even though they often met the pre-conditions for PCB.[footnote 3] By releasing a suspect under investigation, and not on PCB, the police cannot impose conditions to manage the suspect, which in turn raised concerns about the impact on the protection of victims and witnesses.[footnote 4] Concerns were also raised about how the move toward RUI affected suspects and the management of investigations.

Impact on victims and witnesses

Using bail to either directly change an offender’s behaviour towards a victim or to allow victims and witnesses to feel safer has been viewed as one of the central benefits of PCB. However, robust evaluative evidence on this effect is not available. Much of the ‘theory of change’ appears to be through imposition and policing of conditions attached, rather than through PCB itself. Recent research commissioned by HMICFRS and HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate (HMCPSI) highlighted that bail conditions often made victims feel safer, particularly in offences where there is a close victim-offender relationship. However, Learmonth (2018) found that victims were often critical of specific conditions and their enforcement. In the post-reform landscape, HMICFRS/HMCPSI (2020) also found that the police were rarely considering the views of the victim when deciding on whether to release the suspect on PCB or RUI, and, for the former, what, if any, conditions to impose.

Others have pointed to a series of secondary benefits of bail conditions. For example, HMICFRS (2019) considered the impact of bail conditions in domestic abuse cases and suggested that bail conditions could help inform other agencies’ decision making, particularly in protecting victims at home. By contrast, the absence of conditions made it more difficult to evidence the need for emergency housing or a protection order (PO).

While this review did not identify any robust outcome evaluations on PCB, a more substantive evidence base exists on the effectiveness of POs. The PO research was initially examined as part of the review because POs share some features of PCB with conditions. However, ultimately, it was concluded that the differences in the way POs are administered were too great for the evidence to be easily translated across to PCB.

Analysis was undertaken to explore whether the sharp fall in PCB in the first year of the reforms was associated with a change in offences closed with the outcome ‘victim does not support the investigation – suspect identified’.

Five forces more than doubled their ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcome numbers in the year to March 2018, more than in any other year ending March 2017 to 2020. In addition, four of these five forces recorded low bail to arrest ratios of less than 5%, suggesting the use of PCB post reform was at extremely low levels in these forces in the year after the reforms. However, this does not provide evidence of a causal link.

Impact on investigative management

A second concern was that creating the presumption against PCB removed a critical feature of effective investigative management. Research (Hillier and Kodz, 2012; Hucklesby, 2015) found that officers, pre-reform, viewed PCB as a useful policing tool and that re-bailing suspects was necessary to effectively manage an investigation. Having fixed bail dates served as prompts for the investigative process. Losing these prompts and IT systems not being adapted to monitor suspects after their release are thought to have contributed to poorer supervision of investigations and extended investigation times.

Concerns about the relationship between PCB reform and the timeliness of investigations have been identified as impacting on suspects, victims and witnesses. In the most extreme cases, delays are thought to have affected a small number of offences where investigations are constrained by time limits for prosecution, resulting in cases being dropped (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020).

Data show long run increases in typical investigation durations since the year ending March 2015. The average (median) time taken to charge suspects has more than doubled from 14 days in the year ending March 2016 to 33 days in the year ending March 2020. However, it is hard to discern the precise impact of the shift to RUI from other factors. It is likely that the general increase in the investigative durations is due to a complex cocktail of factors including increasing levels of demand on the police, such as more reporting of complex crimes, and it being increasingly common to retrieve and examine digital evidence. The move to RUI may also have been a contributing factor by weakening the discipline of investigative management.

The impact on suspects

There are two main dimensions to the impact on suspects.

The large-scale shift to RUI has led to weaker communications between investigators and suspects. The reforms sought to reduce the long durations that suspects found themselves on PCB, principally under conditions. However, because of the shift to RUI, suspects find themselves without the guaranteed access to information about the progression of their case that the bail checkpoints previously created. This creates uncertainty around the case and can contribute to lengthy investigations, leaving suspects ‘in limbo’.

The lack of monitoring of RUI suspects by forces has potential issues around the handling of biometric samples. In his 2019 annual report, the Biometrics Commissioner noted that owing to the restrictive nature of police IT systems, some forces were unable to provide data about the number of suspects RUI, with knock-on impacts on the effective management of biometric samples (Wiles, 2020). This might have led to some forces unlawfully holding biometric data.

1. Introduction

The police in England and Wales can grant pre-charge bail (PCB), also known as police bail, to individuals arrested on suspicion of committing a criminal offence, but where there are no grounds to keep them in detention while the investigation is ongoing. At this stage in the investigative process, there is insufficient evidence to charge the individual for the offence. PCB is used to manage the arrested individual during the investigation while evidence is obtained in relation to the offence. A person granted bail is periodically required to re-attend a police station. To secure compliance with the requirements of bail, conditions may be attached, such as no contact with a victim or restrictions on entering certain areas.

Prior to the bail reforms of 2017, there were growing criticisms that some suspects were spending extended periods on bail before they were charged with an offence or the case was closed as ‘no further action’ (NFA). The Government legislated through the Policing and Crime Act 2017 (PCA) to address these concerns. Specifically, it introduced measures to limit PCB periods, seeking to rebalance the police use of bail in the interest of fairness. The PCA introduced a presumption against using PCB unless its application was considered both necessary and proportionate in all the circumstances. It also provided clear statutory timescales and processes for the initial imposition and extension of bail. PCB currently operates under this legislation.

Since the reforms came into force (April 2017), the use of PCB has fallen – dramatically in the first year – mirrored by an increasing number of individuals ‘released under investigation’ (RUI) (The Law Society, 2019). However, individuals released under investigation are not subject to conditions,[footnote 5] and there are no time limits set for the suspect to return to the police station.

The marked decrease in using PCB and the increased use of RUI have led to a new set of criticisms. In general, these criticisms can be grouped into three areas:

Victims and witnesses

Suspects, who often met the pre-conditions (see footnote 3) for PCB under the 2017 amendments, including those suspected of domestic abuse and sexual offences, were nonetheless being placed on RUI. This meant that victims and witnesses in these cases were at risk of not being protected through conditions that police bail could provide.

Investigative management

Weakened investigative management due to ending the requirement under PCB of fixed points when officers had to engage with a suspect directly. This, it was argued, might affect the timeliness of case progression. Additional delays in already long case durations might further impact negatively on victims, witnesses and suspects.

Suspects

Suspects not released on bail can be left RUI for long periods of time with no or irregular updates on the progress of their case, adding further uncertainty to the process.

The Government committed to reviewing PCB to consider the need for further change to ensure that PCB is being used where appropriate and to support the police in the timely progression of investigations.

As part of the review, it was proposed that an evidence review on PCB should be undertaken. Specifically, this has sought to address two key issues: (1) what data exists on the use and nature of PCB; and (2) what impact have the 2017 reforms had on the use of PCB in England and Wales. The exercise also intended to explore the evidence on the effectiveness of PCB. However, very limited robust evidence directly associated with the effectiveness of PCB was identified.

2. Methodology

The contents of this review are based on a structured evidence-gathering exercise of published evidence and data.

2.1 Research evidence

The research literature assessed for this review were studies which were easily accessible and in the English language. The search for international research on PCB focused on criminal justice processes which were equivalent to PCB in England and Wales. Within the UK, broadly similar approaches to PCB were found in Scotland and Northern Ireland, although they have different legislative terms. For example, in Scotland the process for releasing suspects before charge with conditions is called ‘investigative liberation’. Hence the search criteria needed to be sufficiently broad as to identify the legislative and criminal justice processes in other countries.

An initial exploratory review, and discussion with subject matter experts, revealed that, while a reasonable amount of research and grey literature exists on the nature and use of PCB, there was little published research into the effectiveness of PCB. However, a more extensive evaluation-based research literature did exist on other forms of pre-charge ‘controls’ such as protection orders (POs). PO interventions, while not direct equivalents to PCB, bore some similarities to PCB with conditions in the way they sought to address offender behaviour, or to support victims, before any charges against a suspect were laid. POs were therefore initially included within the search criteria.

The full set of search criteria used were:

Pre-charge bail

Police, law enforcement, court, pre-charge bail, bail, released under investigation, post-charge bail, crime, policing, criminal justice, domestic abuse, effectiveness, domestic violence, sexual assault, harassment.

Protection orders

Protection orders, civil protection orders, domestic violence protection orders and notices, barring orders, civil orders, stalking protection orders, restraining orders, effectiveness, occupation orders, non-molestation orders, domestic abuse.

Search terms were applied to the following databases: National Police Library, Social Research Association, Campbell Collaboration, NCJRS, WorldCat, Google Scholar and Google search. This search was limited to studies from 1984 to present, to only include research on PCB following legislative changes contained within the PACE Act (1984). The main searching took place between November 2019 and March 2020.

The search yielded 79 published articles and reports which initially met the search criteria for PCB. Three studies were also provided by academics with expertise in PCB. Of the articles and reports, many were excluded because they were not empirical research studies or academic evaluations, or they were not directly relevant to the topic area. This report draws primarily upon eight studies which involved exploratory research PCB or RUI and 11 studies which explored bail in the wider context of the criminal justice system. None of these studies were formal impact evaluations and the majority were descriptive. None reported direct evidence to answer the question on the effectiveness of PCB within the criminal justice process.

The search yielded 61 published studies which initially met the search criteria for POs. Of these, 13 were subject to a more detailed review. There were three systematic reviews and/or meta-analyses (Benitez et al., 2010; Dowling et al., 2018a; Cordier et al., 2019). One focused specifically on reviewing the effectiveness of POs in reducing recidivism in domestic violence[footnote 6] cases (Cordier et al., 2019). The other looked more broadly at research into the use and impact of POs for domestic violence, using the EMMIE framework[footnote 7] (Dowling et al., 2018a). The literature covered by both reviews is dominated by research on POs from the US, therefore it may not be generalisable to England and Wales. The third review, by Benitez et al. (2010), explored whether POs protect victims and the public by reducing the risk of future harm. The ten remaining individual PO studies were reviewed using the Maryland scale.[footnote 8]

Ultimately, having reviewed the PO evidence, it was concluded that the differences in the way POs are administered were too great for the evidence to be easily applied to PCB. The findings from the review of studies of POs are therefore summarised only briefly in the main report, with a more extensive description in Appendix D.

2.2 Data

The evidence review has also drawn upon available data on the use of PCB in England and Wales. These were frequently patchy and inconsistent (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020). Data on the use of PCB were not routinely collected until after the reforms in 2017. Beyond the bespoke studies described above, very little data have been collected on bail conditions, bail breaches, offending on bail, bail extensions and police actions in response to any bail breaches.

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests generated some useful material on overall use of PCB, although there were issues with both coverage – not all forces responded – and comparability across forces (The Law Society, 2019). Differences exist in recording and categorising bail from force to force (e.g. individual force IT systems for bail management are not analogous) making it difficult to precisely compare PCB usage across forces. HMICFRS/HMCPSI (2020) identified several reasons why the data may not be comparable. Forces measure PCB and RUI cases in different ways. For example, some forces count on an offender basis, whereas others count on an offence basis. Nevertheless, the FOI data were helpful as they allow, to some extent, broad comparisons to be made on the use of PCB before and after the reforms.

Data on PCB have been published as experimental statistics in the Home Office’s Police Powers and Procedures statistical bulletins since 2018 (Home Office, 2018; 2019; 2020a). These cover how many individuals were released on PCB and average time spent on PCB. In the first year, year ending March 2018, coverage was limited to only 17 forces, but this increased to 41 forces and 40 forces in years ending March 2019 and 2020, respectively. Despite data now being routinely collected, police forces[footnote 9] and HMICFRS have raised concerns about the quality of data, highlighting the existence of partial returns and a lack of consistency between police forces in recording PCB (Home Office, 2019; HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020). As these data are experimental, any conclusions should be made with caution. The experimental statistics do not cover RUI data.

3. History and context of pre-charge bail

There are several stages in the criminal justice process when the decision to bail an individual can be made:

- By the police when there is not sufficient evidence to charge, also known as precharge bail (PCB).

- By the police when there is sufficient evidence available to charge, also known as post-charge bail.

- By the courts when a person has been charged, also known as court bail.

Bail can be imposed with or without conditions in all three circumstances.

3.1 Process of pre-charge bail

The police in England and Wales can grant PCB under Part 4 of the Police and Criminal and Evidence Act 1984 (PACE). The suspect can only be detained in custody in most cases up to 24 or 36 hours (referred to as the ‘custody clock’) before they must be charged or released. If additional enquires are required, and they cannot be undertaken immediately, then the suspect is released until the police complete their enquiries, so they are not detained in custody unnecessarily. PCB means the individual under investigation is released from police custody, with or without conditions, while officers continue their investigation.

In the period before April 2017, an individual who was arrested, but for whom enquiries were ongoing, would usually be released on PCB. On rare occasions, releasing a suspect pending further investigations without bail prior to the 2017 reforms took place in the aftermath of Hookway.[footnote 10] Since April 2017, suspects released without charge are either RUI or on PCB, with or without conditions.

Once released from custody on PCB, the suspect’s custody clock stops and when the suspect returns to answer their bail, the clock continues and any further evidence that has been obtained can be put to them. The suspect may then be charged, re-bailed, released under investigation or no further action taken against them. The Bail Act 1976 specifies that no conditions should be imposed with PCB unless it appears to the officer granting bail that it is necessary to do so to prevent a person from failing to surrender or committing further offences etc (see 3.2 below for more details) (Bail Act, 1976). Legislation covering bail exists under multiple Acts and Figure 1 sets out how the authority for the police to impose PCB has evolved over time.

Figure 1: Timeline of PCB in England and Wales

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1925 | Pre-charge bail introduced under the Criminal Justice Act (CJA) 1925 |

| 1976 | Following the CJA 1967 which introduced conditional bail, Section 3 of the Bail Act 1976 enshrined the power to impose conditions on bail for courts |

| 1984 | Following the 1981 Royal Commission on Criminal Procedure, PCB subjected to tighter controls under The Police and Criminal Evidence Act (PACE) 1984 |

| 2003 | Police powers extended to allow officers to attach bail conditions to PCB under the CJA 2003 |

| 2017 | Reforms to PCB following the consultations were introduced in the PCA 2017 |

| 2019 | Review into PCB law announced by Government |

Source: Bail Act (1976); PACE (1984); CJA (2003); Cape (2016); PCA (2017); Gov.uk (2019)

Information on comparative jurisdictions, such as Northern Ireland and Scotland, is summarised in Appendix A. PCB can also be imposed where there is sufficient evidence to charge a suspect and the suspect is bailed while the CPS make a charging decision (granted under s.37(7)(a) PACE). This type of pre-charge bail was not the subject of the reforms made under the PCA 2017 and is not subject to the same authorisations or timescales as PCB where there is insufficient evidence to charge. It is not covered in detail in this evidence review.

3.2 Pre-charge bail with conditions

The Criminal Justice Act (CJA) 1967 introduced conditional bail which was enshrined in the Bail Act 1976 and subsequent legislation has amended it further.[footnote 11] If the preconditions (see footnote 3) for granting bail as set out in Section 3 of the Act are met, conditions should be applied to the suspect’s bail in order to ensure that the suspect:

- surrenders to custody at the end of the bail period

- does not commit an offence while on bail

- does not interfere with witnesses

- does not otherwise obstruct the course of justice.

Conditions may also be attached for the suspect’s own protection and, where the suspect is a child or young person, for their own welfare. Conditions imposed may include:

- A ban on leaving the country including the requirement to surrender a passport

- Not being allowed to enter a certain area such as the home of the alleged victim

- Adherence to curfew

- Residing at a specific residence during the bail period

- Not being allowed to communicate with certain people e.g. victims, witnesses and known associates.

Conditions are not legally specified and central advice or guidance on what conditions police should impose is limited. There are very few restrictions on what conditions they can impose, with officers using their own discretion. However, the Bail Act 1976 and the CJA 2003 state that for either pre-or post-charge bail the police cannot impose the following conditions on a suspect (CPS.gov.uk, 2019):

- To reside at a bail hostel

- To attend an interview with a legal adviser

- To make themself available for probation enquires and reports

- That contain electronic monitoring requirements.

Taking this all in to account, PCB can arguably be claimed to be meeting three main objectives: suspect management (including preventing re-offending); protecting victims and witnesses, primarily through conditional PCB; and investigative management including allowing time to obtain evidence.

Purposes of unconditional PCB

- Investigative management, e.g. allows time to obtain evidence, investigations to be conducted in a timely manner and limits the time spent in police custody

- Suspect management, which is closely linked to investigative management, e.g. suspect under duty to re-attend a police station

Purposes of conditional PCB

- Protect victims and witnesses, e.g. to ensure suspect does not approach or contact the victim or witness

- Investigative management, e.g. does not obstruct the course of justice

- Suspect management, which is closely linked to investigative management, e.g. preventing further offences being committed while on bail or keeping suspects away from criminal associates

3.3 Breaches

Under PCA 2017, breach of PCB conditions is arrestable, but it is not a criminal offence (CPS.gov.uk, 2019). Therefore, there is no criminal sanction resulting from a breach.[footnote 12] Officers can arrest individuals for a breach, and then charge the suspect with the original offence or release them with or without charge, either on bail or without bail. If they are released on bail, conditions set for the original bail can be re-applied. There is currently no available data on breaches of conditions, although some exploratory research on this area (Hillier and Kodz, 2012) is discussed later in this report.

3.4 The 2017 Act and its aftermath

Calls for legislative reforms to PCB grew following several high-profile cases where individuals were released on bail for long periods – in some cases over a year – but ultimately not charged. These cases included individuals arrested on suspicion of sexual offences between 2012 and 2014 as part of Operation Yewtree. Bail conditions included having supervised contact with their children and surrendering passports. When giving evidence to the Home Affairs Select Committee in March 2015, one celebrity who was arrested and bailed without charge expressed the view that the protracted period on bail resulted in significant personal, professional and financial loss (House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, 2015).

Following public consultations by the College of Policing (2014) and the Home Office (2015), and on the back of the Home Affairs Committee report (2015), further legislation regarding PCB was introduced. The Policing and Crime Act (2017) came into force on 3 April 2017 which aimed to rebalance the police use of bail in the interest of fairness. This legislation included reforms of PACE (1984) such that:

- an initial PCB limit of up to 28 days was set

- a presumption of release without bail unless necessity and proportionality criteria are met

- extensions of PCB had to be authorised by a superintendent (up to three months after the initial bail date), or by a Magistrates’ Court (longer than three months after the initial bail date)

- the authorising inspector must consider any representations made by the person or their legal representative (s.50A(b) PACE).

Historically, the purpose of PCB was to limit the time spent in police detention and to release suspects, without charge, for them to return later to the police station. Under PACE it was outlined that PCB is available to manage an arrested individual while the investigation continues to obtain evidence in relation to the offence, or while a decision to charge is being attained.

However, the PCA 2017 introduced further bail pre-conditions which had to be met. The custody officer now needs to feel satisfied that releasing the person on bail is necessary and proportionate in all circumstances. In addition, an officer of the rank of inspector or above must authorise the release. If this is not the case but the grounds remained to suspect an individual of an offence, then they should be released with no bail obligations (i.e., RUI).

When individuals are RUI, they are not subject to any conditions, and as there are no time limits set for the suspect to return to the police station, the time for the investigation is unlimited. This is contrary to the intentions of the amendments of the PCA (2017), which aimed to reduce how long an individual was under investigation.

There was a substantial reduction in PCB in the immediate aftermath of these changes, mirrored by an increase in using RUI. The marked decrease in using PCB, and the growth in RUI, has led to a new set of criticisms. The Law Society (2019) drew on case studies from lawyers where suspects had been RUI for long periods with no updates on how their case was progressing. The Centre for Women’s Justice (2019) launched a super-complaint which heavily criticised the police for failing to impose bail conditions in high-risk cases where female victims were particularly vulnerable. There were also concerns that the reforms had led to weakened investigative management, particularly with the increased use of RUI, as there were no requirements for officers to check in with suspects.

HMICFRS’s PEEL effectiveness report (2018) for 2017 highlighted concerns about the reduced use of PCB. It included a national recommendation for all forces to review how they implemented the PCB reforms by September 2018. Subsequently, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) published guidance around using PCB and RUI in early 2019. This guidance was intended “to reinforce the message that in the right circumstances, the use of PCB is still a legitimate investigative and safeguarding tool” (NPCC, 2019; p. 1). The Government announced in 2019 that it would review PCB laws (Gov.uk, 2019.)

4. The use and nature of pre-charge bail

4.1 The use and nature of PCB prior to the 2017 reforms

Very little published data exists on the use and nature of PCB. One rare early insight comes from Phillips and Brown’s (1998) detailed statistical examination of the CJS process in the 1990s. This was based on a survey of 4,250 people who had been detained at ten police stations in England and Wales. Research by Hillier and Kodz (2012) and Hucklesby (2015) provides useful insights into the use of PCB prior to the reforms. Hillier and Kodz (2012) conducted interviews and focus groups with 80 police practitioners in five police forces. Hucklesby (2015) conducted research in two police forces in England between 2011 and 2013. The mixed methods study comprised observations, a review of 14,173 PCB records, questionnaires completed by police officers and 38 interviews with police staff. Martin (forthcoming) undertook a detailed study of PCB two years before and two years after the reforms in a single force. His dataset included over 247,000 individual offences across the four-year period.

Volumes

Several studies suggest that, pre-reform, approximately one-third of those arrested were subsequently released on PCB (see Appendix B; Hillier and Kodz, 2012; House of Commons Home Affairs Committee, 2015; College of Policing, 2016; College of Policing, 2017). Other analysis has suggested a higher proportion. Based on data from 12 police forces provided by the College of Policing, it has been estimated that 404,000 individuals were released on PCB in the year ending March 2014 (Home Office, 2015), equivalent to around 43% of arrestees. And in the year immediately before the reforms (2016 to 2017), a comparison of FOI data and Home Office arrest data suggested a similar overall ratio (Law Society 2019; Home Office 2020a).[footnote 13] However, these aggregate estimates conceal much wider variations in PCB use at force level.[footnote 14]

Offence type

Hucklesby (2015) found that PCB was most commonly used for: violence offences, approximately one-third in both forces; theft-related offences, around one-fifth in both forces; and property offences (19% in Force A, 13% in Force B). Philips and Brown (1998) also found that the use of PCB varied considerably according to offence type. It was most frequently given where suspects had been arrested for fraud, sexual offences, robbery and drug offences, where approximately 30% of those arrested were bailed for further enquires.

Duration

Based on data provided by 12 forces for the year ending March 2014, around eight in ten (79%) suspects were on PCB for up to three months, while an estimated 14% were on bail for between three and six months (Home Office, 2015). Only 1% – equivalent to an estimated 5,000 individuals nationally – were on bail for in excess of 12 months. Hucklesby (2015) found that the average time spent on bail was between six and seven weeks in both forces studied, in line with a College of Policing (2016) estimate based on nine forces. The College of Policing (2016) also found that of the 9% of cases bailed initially for over 90 days, rape, sex and drug offences were most common (accounting for 55% of these cases). As with most aspects of PCB, individual forces show wide variations in the average duration of PCB. Law Society (2019) data indicate that in the year prior to the reforms, the average duration of PCB for suspects in nine forces ranged from 53 days to 175 days. Martin’s (forthcoming) single force study, based on data for suspects linked to almost 25,500 offences recorded between April 2015 and April 2017 (i.e. before the reforms), found an average PCB duration of 140 days per offence, with 65% of offences dealt with within the first three months.[footnote 15]

Outcomes post bail

Studies have generally found that around a half of PCB cases before the reforms resulted in NFA. Hucklesby (2015) found that almost half of the bail records analysed in the two police forces had an NFA outcome while Phillips and Brown’s (1998) much earlier study found that 44% of PCB cases had an NFA outcome. Hillier and Kodz (2012) found that those bailed were more likely to be given an NFA outcome than a charge. The proportion of NFAs has also been found to vary by offence type, with 60% for sexual offences, 50% for violence offences and 20% for traffic offences (Hucklesby, 2015).

Ethnicity

In her research on two police forces, Hucklesby (2015) found that while the ethnicity of bailed suspects broadly reflected the profile of arrest data, White European suspects given PCB were more likely to be charged than people from other ethnic groups on PCB. Cases involving suspects from black and other minority ethnic backgrounds were more likely to result in NFA.

Conditions

There is little data on the frequency and type of conditions imposed through PCB or the extent to which suspects comply. This extends to data on reasons behind decisions and breaches of conditions. However, the evidence that exists suggests that practice can vary widely from force to force. Hucklesby (2015) found that of the two forces, one used bail conditions in 67% of PCB cases. The other force had a policy not to impose bail conditions on PCB at all, which was criticised by nearly all those interviewed in the force. Martin’s (forthcoming) single force study found 68% of suspects on bail had conditions in the year before the reforms. Hucklesby’s (2015) interview-based research suggested that ‘banning’ conditions, i.e. keeping away from people and places, were the type of conditions most frequently used. Police officers interviewed by Hillier and Kodz (2012) viewed penalties for breaching police bail conditions as inadequate, commonly describing them as being a ‘toothless tiger’.

There is a larger evidence base on conditions around post-charge and court bail; both Hucklesby (2001) and Raine and Wilson (1996) found regional variation on the use of post-charge bail conditions in their research. The types of conditions focused around a few themes such as residing at a specific address and similar to Hucklesby’s (2015) findings for PCB, ‘banning’ conditions’ include preventing contact with victims and/or witnesses, and keeping away from specific areas and associates.

4.2 The use of PCB and RUI in England & Wales following the reforms in 2017

The number and percentage of individuals on PCB

Arguably the most useful source of data on the immediate impact of the 2017 reforms on the use of PCB comes from a Law Society (2019) report. Their analysis examined the use of PCB and RUI by the police in England and Wales and Northern Ireland. The main value of The Law Society analysis is that it covers the period before and after the change in legislation. However, these data are not part of an established data collection but are based on an FOI request and should therefore be treated with caution.

There may also be some specific measurement issues in PCB data in the post-reform period. Pre-reform, suspects would stay on PCB for the duration of the investigation. However, this situation seems to have changed in the post-reform period. Martin’s (forthcoming) detailed study of an English force found that while individuals would be placed on PCB initially, some switched to RUI after the initial 28-day bail period. This affected 20% of bailed cases in the year ending 2 April 2019. Of the offence types analysed, sexual offences (26%), rape/attempted rape (19%) and grievous bodily harm (18%) were most likely to switch from PCB to RUI following the initial 28-day bail period.[footnote 16] Home Office exploratory research[footnote 17] undertaken for this review also found evidence that, post-reform, PCB cases were often switching to RUI after the initial 28-day bail period (between 31% and 37% of cases in the two forces examined). This makes the question of consistently counting PCB and RUI volumes much less straightforward after the reforms. The HMICFRS/HMCPSI thematic review of PCB (2020) found that, in most forces, a suspect’s status defaults to RUI after the 28-day initial bail period ends.

The Law Society (2019) report is based on data from an FOI request submitted by law firm Hickman & Rose Solicitors. In response to the request, 29 police forces in England and Wales returned data for years ending 2 April 2017 and 2018.[footnote 18] The following analysis combines FOI data from The Law Society and Home Office experimental statistics[footnote 19] for the years ending March 2019 and 2020, to provide an overview of trends based on a consistent sample of forces.[footnote 20] In Figure 2, a subsample of data from 27 forces for all datasets is presented to map aggregate trends in PCB use. This subset of 27 forces account for three quarters (75%) of PCB volumes in the year ending March 2020.

Figure 2: Number of individuals arrested and subsequently placed on PCB in England and Wales, based on a sample of 27 forces (Based on a consistent set of 27 English and Welsh forces covered in all three datasets.)

| Year | Number placed on PCB |

|---|---|

| 2016/17 | 190000 |

| 2017/18 | 29300 |

| 2018/19 | 60500 |

| 2019/20 | 115800 |

Figure 2 shows that, in 27 forces, approximately 190,000 individuals were put on PCB in year ending 2 April 2017 (Law Society, 2019). This figure dropped by 85% to approximately 29,300 in the year ending 2 April 2018, the year after the reforms. Home Office experimental statistics for the same 27 forces suggest the number of individuals on PCB increased by 106% in the year ending March 2019, to 60,500. In the year ending March 2020, numbers increased again, up by 92%, to 115,800, but were still below prereform volumes (a difference of around 74,000). The Home Office experimental statistics on PCB achieved high levels of force coverage in the most recent two years (41 forces in the year ending March 2019, and 40 forces in the year ending March 2020). Looking at the 40 forces which submitted data for each of the last two years, there was an 81% increase in the use of PCB, from approximately 84,200 to 153,500, in England and Wales (Home Office, 2019; Home Office, 2020a).

The increase in PCB after the reforms were introduced in April 2017 is thought to be partly related to concerns raised by HMICFRS and the issuing of NPCC guidance in 2019. In their PEEL effectiveness report for 2017, HMICFRS issued a recommendation requiring all forces to review how they implemented changes to PCB by September 2018. That report also stated that “forces should then put into effect any necessary changes to make sure they are using bail effectively, and in particular that vulnerable victims get the protection that bail conditions can give them” (HMICFRS, 2018; p. 29). NPCC operational guidance clarifying the position around the use of PCB was published in January 2019 (NPCC, 2019). This guidance emphasised the need to continue to use PCB, where necessary and proportionate, highlighting PCB’s importance as a legitimate investigative and safeguarding tool.

While issues remain about the consistency and reliability of the FOI data across forces, it is helpful to examine the broad pattern of PCB usage by force, before and after the reforms. Force by force numbers are given in Appendix C. Figure 3 sets out ratios of PCB to arrest volumes for 2016/17 and 2017/18 ranked by 2018 values.[footnote 21] They imply a very wide variation in use of PCB in the year before the reforms. Seven forces achieved ratios of 50% and above in 2016/17, while six forces recorded ratios of below 20%. Following the reforms, eight forces saw ratios fall to 2% or less. However, six forces[footnote 22] had ratios of 10% and above, with Essex having the highest ratio (24%). Although these ratios can only be taken as illustrative, they suggest that while most forces saw marked reductions in the PCB to arrest ratio across the two years, some saw the ratio fall to very low levels. And while all but one force reduced their ratios, others achieved ratios which exceeded those that some forces were achieving before the reforms.

Figure 3: Estimated ratio of PCB volumes to arrests, years 2016/17 and 2017/18, selected forces

There is a two-day difference between the timeframes for the arrest data collected for the Home Office Police Powers and Procedures publication (1 April to 31 March) and the FOI data provided by The Law Society (3 April to 2 April).

| Force | 2016/17 | 2017/18 |

|---|---|---|

| Hertfordshire | 8.8 | 0.6 |

| Cleveland | 14.0 | 0.7 |

| Dorset | 37.4 | 1.2 |

| Thames Valley | 39.8 | 1.2 |

| Derbyshire | 5.1 | 1.5 |

| Devon and Cornwall | 40 | 1.8 |

| Leicestershire | 44.8 | 2.2 |

| Avon and Somerset | 41.3 | 2.3 |

| North Wales | 33.4 | 3.7 |

| Staffordshire | 38.5 | 3.7 |

| Northamptonshire | 33.8 | 4.1 |

| Nottinghamshire | 50.9 | 4.2 |

| Cheshire | 35.9 | 4.7 |

| Lincolnshire | 38.2 | 5 |

| Merseyside | 21.6 | 5.5 |

| Gwent | 50.2 | 6.9 |

| Bedfordshire | 40 | 6.9 |

| Greater Manchester | 39.6 | 6.9 |

| London Metropolitan | 44.6 | 7.9 |

| Cumbria | 51.1 | 8.3 |

| Cambridgeshire | 48.45 | 8.7 |

| Norfolk | 4.5 | 8.8 |

| Warwickshire | 50 | 10.7 |

| Surrey | 57.3 | 11.1 |

| Suffolk | 12.5 | 12.2 |

| South Wales | 21.6 | 13.7 |

| West Mercia | 55.2 | 14.8 |

| Essex | 71. | 24.2 |

Source: Law Society (2019); Home Office (2020a)

Limited data exist on how the PCB reforms affected different crime types. Martin’s (forthcoming) detailed before and after study of one force found the overall composition of PCB by offence type changed after the reforms. Comparing the percentage share of PCB by offence type, Martin found there was a shift towards more serious interpersonal offences in the two years after the reforms, and a corresponding fall in the share accounted for by theft offences. For example, sexual offences increased from 10% to 18% of total PCB and GBH went up from 6% to 12%. By contrast, theft offences fell as a share of PCB (27% pre-reforms but only 8% in the two years after). However, changes in the crime type share of PCB need to be considered against the marked fall in its overall use after the reforms. Martin found that total volumes fell from an average of 12,344 prereform (April 2015 to April 2017) to an average of 1,165 post-reform (April 2017 to April 2019). So, while serious offences accounted for a greater share of all PCB after the reforms, bail volumes for these offences showed absolute falls in this same time period.

Use of RUI following the reforms

After the reforms, and introducing the presumption against PCB, the main option for managing arrested suspects whose investigations were ongoing became RUI. Just as there had been a large fall in the use of PCB in the immediate aftermath of the reforms, the use of RUI became commonplace (The Law Society, 2019). Figures based on FOI requests from 29 forces in England and Wales published by The Law Society revealed that approximately 177,000 individuals were on RUI in the year ending 2 April 2018 (The Law Society, 2019). This broadly equates to the approximate 171,000 reduction in the number of arrestees on PCB for these forces, suggesting that there was a simple shift from releasing individuals on PCB to RUI. However, we would not expect these figures to match entirely. One of the challenges around measuring PCB (and RUI) volumes post-reform is that the individuals would sometimes shift from PCB to RUI as the case progressed (see above).

Timeliness

Comparing data on durations for those on bail is arguably of only limited value. This is because the precipitous reduction in bail volumes that took place after the reforms mean that neither the volume of cases, nor the types of offence characteristics covered, are comparable before and after 2017.

5. The impact of the decreased use of PCB and increased use of RUI following the reforms in 2017

The large-scale reduction in using PCB, especially in the period immediately after the reforms, raised concerns about the impact on suspects, victims, witnesses and the wider criminal justice system. In particular, there were concerns that those suspected of serious offences – violent and sexual offences – and those involving repeat offenders, were being RUI rather than released on PCB, even though they often meet the pre-conditions for PCB (see footnote 3) (see for instance, The Law Society, 2019). In this section, evidence on the impact of the changes is considered.

5.1 Views of the impact on victims and witnesses – primary and secondary effects

One area of concern is how reduced use of PCB has affected victims’ and witnesses’ safety and wellbeing, especially in cases involving domestic abuse or other offences involving close victim-offender relationships, for example rape, sexual assault and stalking offences (Learmonth, 2018). There are several linked questions here. The first of these – classified here as primary effects – relates to how the use of bail conditions can either change an offender’s behaviour towards a victim, or, alternatively, simply allow a victim to feel safer (Centre for Women’s Justice, 2019).

5.2 Victim perceptions on pre-charge bail

Studies which have focused explicitly on the extent to which victims felt bail affected their feelings of safety are rare. As part of the HMICFRS/HMCPSI inspection on PCB, research was conducted with 27 victims of crime by BritainThinks (2020). Participants had been victims of a range of crime types, but domestic abuse and stalking/harassment offences dominated (17 of the 27 participants). Investigations had been closed at the time of interview, with offences taking place within the 18 months before their participation in the research. Some victims were not clear whether suspects in their cases had been given RUI or PCB, and generally found the terminology confusing. However, participants were apparently clear about when suspects in their cases had been released under PCB with conditions. Participants generally described feeling safer in cases where suspects had been released with bail conditions, particularly if they knew that the suspect was not permitted to contact them while the investigation was ongoing. Knowing that they had ‘permission’ to contact the police and report this if it happened made them feel more confident, even if they believed the likelihood of a breach of this condition was high. These findings echo those from some of the literature on POs – see Appendix D. By contrast, some victim interviewees described feeling unsafe when suspects were under RUI. They felt there was nothing in place to prevent re-offending, a view most strongly held by domestic abuse and stalking and harassment victims. An exploratory small-scale study into the use of bail in rape cases (Learmonth, 2018) found that survivors expected to be entitled to personal safety during the investigation and were distressed when bail conditions were felt to be inadequate.

5.3 Professionals’ perceptions of victims’ security

Research undertaken for HMICFRS by BritainThinks (2020) also included interviews with professionals – mainly those working in third-sector bodies directly supporting victims – to gather their perceptions on the impact of PCB on victims’ feelings of safety. Two main findings emerged. First, they argued that the absence of bail conditions signalled to victims that even if they are at risk they were being taken less seriously, and they felt ‘isolated’ and ‘alone’. Second, they argued that absence of conditions resulted in more limited lines of communication with the police. This in turn engendered a stronger sense of support from the police through PCB (with conditions) than RUI.

There is certainly some evidence that, three years after the reforms, and despite the recovery in PCB volumes, the right balance between bail and RUI has not been found. The joint HMICFRS/HMCPSI inspection on PCB (2020) was critical of the police for not considering the views of the victim when deciding on whether to bail a suspect and informing the conditions to impose. In their analysis of 140 case files in charged cases, they found that in just under half (62), RUI had been used when PCB with conditions would have met the ‘necessity’ and ‘proportionate’ tests. These offences included domestic abuse, sexual offences and offences against children. Martin’s (forthcoming) research in one force found that for offences which had warning classification flags for ‘domestic abuse’ and/or ‘child at risk’, the proportion of suspects who were subject to PCB fell markedly when comparing the two years before and two years after the reforms (from 15% down to 3%). The Law Society (2019) also highlighted several examples where not putting the suspect on bail put the public at risk.

This, of course, is not the same as saying the system was working effectively in managing the risk around victims before the reforms, particularly in domestic abuse and sexual offence cases. The evidence points to a variable picture, albeit one where a much higher number of suspects were placed on PCB for the duration of their investigations prior to the reforms. But in the area around managing victim risk, on the most critical issue around the use conditions, very limited evidence exists. Hucklesby’s (2015) research on two forces showed that one force operated with no conditions, while the other force used conditions in two-thirds of PCB cases. Learmonth’s (2018) small-scale study found four of the six women interviewed to be critical of the conditions of PCB which were insufficient for their needs, particularly the lack of consequences for breaches of conditions.

5.4 The evaluation evidence base

Of course, we still cannot draw on robust evidence that shows that PCB with conditions definitively works, leading to better outcomes (e.g. reduced victimisation, higher levels of victim satisfaction or lower levels of victim withdrawals, reduced risks to the suspect). No evaluative studies were identified explicitly on PCB. Some potentially useful evaluations conducted on the effectiveness of POs were identified and are summarised in Appendix D. Some functions of POs are similar to conditional PCB, such as applying restrictions on individuals not to contact the victim or enter certain locations or addresses. However, there are some fundamental differences between PCB and POs that make ‘translation’ of the evidence difficult. In some jurisdictions, PO violations can result in a criminal sanction, which is not the case for breaches of PCB. Durations of POs are typically longer than PCB. POs tend to be victim-generated rather than an automatic criminal justice response initiated by the police and tend to be focused on a smaller subset of offence types (principally around domestic abuse).

The evidence base on the effectiveness of POs suggests that there are some situations where POs may be effective in reducing re-offending and protecting the victim. Two systematic reviews provided some evidence that POs can be effective at reducing recidivism in domestic violence and interpersonal violence cases (Dowling et al., 2018a; Cordier et al., 2019). In their evaluation of Domestic Violence Protection Orders (DVPOs) in England and Wales, Kelly et al. (2013) found that DVPOs were associated with reduced rates of victimisation. However, other studies found that some victims continued to suffer violence or violations of their POs (Logan and Walker, 2009; Kothari et al., 2012). Nevertheless, Logan and Walker (2009) found that most victims perceived POs to be effective, even in cases where POs were violated and violence continued. Kelly et al. (2013) also found that POs could be more effective when used alongside support services. But, as noted, directly translating these findings across to PCB with conditions is not straightforward.

5.5 Changes in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcomes

Data were examined to assess whether any impact of reduced use of PCB might be reflected by an increase in offences closed with the police outcome ‘evidential difficulties suspect identified – victim does not support further action’.[footnote 23] The assumption was that victims might be less likely to support investigations if suspects in their cases were not subject to PCB (with conditions), and any effect might be most apparent in those cases where victims and suspects were known to each other. The precise theory of change is likely to be complex, but the absence of bail with conditions might be linked to an increase in victim’s concerns around safety or a feeling that a case is not being taken seriously and increase the likelihood of victim withdrawal. In addition, if the ending of PCB contributed to longer investigations, this also might increase the risk of victim withdrawal. If there was a year-on-year impact on ‘victim does not support’ outcomes in the wake of the reforms, it would be most evident in the year ending March 2018, as the partial recovery in PCB volumes in subsequent years might have ameliorated any immediate effect.

Many factors lead victims to withdraw their support for police action. An international review of the evidence on domestic abuse – ‘victim does not support’ outcomes are overrepresented within DA offences[footnote 24] -found a variety of reasons for victims’ retraction of statements (Dowling et al, 2018b).[footnote 25] The most commonly identified were: fear of reprisal; still wanting a relationship with the perpetrator; wanting the perpetrator to receive help instead of punishment; not wanting their children to be without a parent; not wanting to subject their children to the court process; fatigue with or pessimism regarding the court process; and financial reliance on the perpetrator. A casefile-based study of recorded rapes (Feist et al., 2007) found that, in victim withdrawal cases, victims wanting ‘to move on’ and a reluctance to see through the investigation or prosecution each accounted for one-fifth of withdrawals. Pressure from others to withdraw and fear of reprisals accounted for 10% and 5% respectively. In addition, other factors will affect changes in ‘victim does not support’ volumes over time. These are likely to include changes arising from changes in the reporting of offences, the composition and recording of offences and the recording of outcomes.

Table 1 and Table 2 show trend data for ‘victim does not support’ outcomes – suspect identified’ with ‘suspect not identified’ included for comparison. The number of ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcomes grew steadily in the period after year ending March 2015, increasing by more than fivefold by the year ending March 2020, accounting for a steadily increasing share of rising recorded crime volumes (Table 1 and Table 2). At the aggregate level, it is hard to find evidence of a sudden and marked shift in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcomes taking place shortly after the reforms. The annual rate of increase slows down during the period, including between the critical years ending March 2017 and 2018 (down from 38% to 34% respectively). We have also looked at changes in the ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcome by force, owing to the variability in the use of PCB at the force level before and after the reforms.

Table 1: Trends in the number of outcomes(a) recorded in year, by selected outcome type:years ending March 2015 to 2020 (excluding GMP[footnote 26])

The figures in this table relate to outcomes recorded in the year regardless of when the associated crime was recorded.

| Years ending 31 March | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidential difficulties, suspect identified: victim does not support further action | 194,036 | 392,679 | 542,671 | 726,235 | 906,054 | 1,009,432 |

| Year-on-year percentage change | 102% | 38% | 34% | 25% | 11% | |

| Evidential difficulties, suspect not identified: victim does not support further action | 49,443 | 118,618 | 158,931 | 216,066 | 250,609 | 239,062 |

| Year-on-year percentage change | 140% | 34% | 36% | 16% | -5% |

Source: Home Office (2020b)

Table 2: Trends in the ratio of selected outcomes recorded in year to total recorded crime, years ending March 2015 to 2020 (excluding GMP) (The figures in this table relate to outcomes recorded in the year regardless of when the associated crime was recorded. Ratio based on number of outcomes recorded in year divided by number of crimes recorded in year.)

| Years ending 31 March | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Police recorded crime | 3,374,272 | 3,671,883 | 4,056,404 | 4,551,859 | 4,935,419 | 5,006,941 |

| Change | 9% | 10% | 12% | 8% | 1% | |

| Evidential difficulties, suspect identified: victim does not support further action (ratio) | 6% | 11% | 13% | 16% | 18% | 20% |

| Evidential difficulties, suspect not identified: victim does not support further action (ratio) | 1% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 5% |

Source: Home Office (2020b)

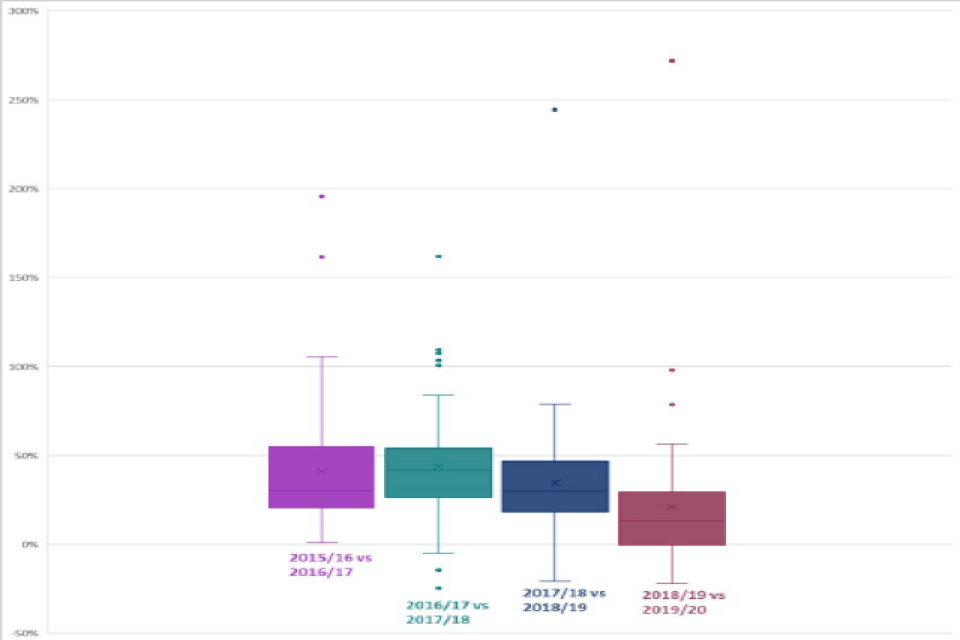

Figure 4 and Table 3 show the distribution of 43 forces’ year-on-year changes in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcomes between 2016 and 2020.[footnote 27] Several features are worth highlighting. First, the median year-on-year change for this outcome was at its highest when comparing years ending March 2017 to 2018 at 42%. This compared with lower median increases in the years either side (see Table 3). Second, compared to other years, year ending March 2018 saw more forces that more than doubled their ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcome (five forces, with year-on-year increases ranging from 101% to 162%). This compares with three forces in years ending March 2016 to 2017 and one in each of the later comparison periods. Of the five forces which recorded a doubling in this outcome, all but one recorded arrest to PCB ratios of below 5% in the year ending March 2018.[footnote 28]

This analysis does not, of course, provide direct evidence that the PCB reforms caused the increase in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’ outcomes in some forces in the immediate aftermath of the reforms. As noted above, many factors can result in victims withdrawing their support for the investigation. However, the data presented are consistent with a theory that the reduction in PCB may have contributed in part to the uplift in ‘victim does not support’ volumes in some forces in the year after reform.

Figure 4: Percentage change in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’, by force area and year, years ending March 2016 to 2020(The figures in this chart relate to outcomes recorded in the year regardless of when the associated crime was recorded.Excludes GMP.)

Box and whisker plot showing the data that are detailed in table 3 below.

Source: Home Office (2020b)

Table 3: Percentage change in ‘victim does not support – suspect identified’, by force area and year, years ending March 2016 to 2020(The data in this table relate to outcomes recorded in the year regardless of when the associated crime was recorded.Excludes GMP.High outliers in a box and whiskers plot are larger than Q3 by at least 1.5 times the interquartile range.)

| Years ending 31 March | 2016/17 | 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 30% | 42% | 30% | 12% |

| Range | 2% to 196% | -25% to 162% | -13% to 244% | -19% to 272% |

| ‘High’ outliers(c) (number & range) | 2 (162% to 196%) | 5 (101% to 162%) | 1 | 3 (79% to 272%) |

| Number of forces showing increases over 100% | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

5.6 Victims: secondary benefits

It has been suggested that there may be some wider benefits from bail conditions, particularly in domestic abuse cases. In their update inspection on domestic abuse, HMICFRS (2019) considered the impact of the bail reforms on domestic abuse cases. Drawing on a focus group with nine practitioners from Women’s Aid, the HMICFRS inspection identified the following areas of concern:

Some police officers had been advising victims to apply for a non-molestation order incases where they had not used bail, thereby placing the responsibility on the victim toprotect themselves.

The absence of bail conditions made it hard to justify keeping the suspect away fromthe home they shared with the victim. Some suspects had been released with no bailconditions and had returned to the family home as they shared a joint tenancy with thevictim, forcing victims and their children to leave.

Where housing departments were asking for proof that a victim needed emergencyhousing, bail conditions would have previously assisted in providing this evidence.This was also found in research by Learmonth (2018) into the use of bail in rapecases where interviewees highlighted conditions are used as a mechanism toleverage safeguarding across partner agencies.

Victims were finding it harder to evidence the need for other safeguarding mechanisms – such as a restraining order – without information on bail history or breaches of bail. Additionally, Hunter, Burton and Trinder (2020) noted that in child arrangement proceedings where domestic abuse is raised, evidence of action in the CJS might be required to support a case in the family courts. Of these four examples, all but the first might be assessed as being closer aligned to secondary – or indirect – benefits of bail with conditions. In other words, it is not the bail which directly changes offender behaviour or victim’s perceptions of safety, rather it is how the existence of bail conditions may be utilised to support decisions around other remedies or protections. And while it can be questioned as to whether bail conditions are the correct mechanism for flagging risk to other agencies, the focus here is on trying to understand the possible impacts of the reforms on existing processes.

5.7 The impact on investigative management

The second area of concern around the impact of the PCB reforms is on investigative management. The main criticism here was that the creation of the presumption against bail removed a pivotal mechanism in effective investigative management. Research undertaken prior to the reforms suggested that PCB acted as a useful management tool and that the process of re-bailing suspects was helpful to effectively manage an investigation (Hillier and Kodz, 2012; Hucklesby, 2015). For instance, Hillier and Kodz (2012) found that re-bailing was particularly useful in cases where the investigation had not progressed as quickly as expected, further evidence was awaited or if the initial bail period was just not long enough.

It is argued that the shift to RUI – and the resulting absence of milestones that existed under PCB – has weakened both the discipline of case management and the supervision of suspects (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020; Wiles, 2020). This in turn is thought to have contributed to longer elapsed times between arrests and case outcomes. In the most extreme cases, it has been suggested that delays have affected a small number of offences where investigations are constrained by time limits for prosecution, resulting in cases being dropped (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020). The wider consequences of delays are the loss of more supportive victims and witnesses, and potentially fewer charges (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020; HMICFRS/BritainThinks, 2020). HMICFRS/HMCPSI (2020) also highlight that, due to delays in investigations, there are often further delays to the prosecution of cases as suspects are notified via postal requisition.[footnote 29]

Concerns about the relationship between PCB reform and the timeliness of investigations have been identified as issues relevant to both victims and suspects. However, trying to isolate the PCB reforms’ effect on timeliness of investigations is difficult. The time it takes from a crime being recorded to a charge or other outcome being given has been increasing for most offence types over recent years, and the increase pre-dates the 2017 bail reforms.[footnote 30] The average (median) time taken to charge suspects after initial recording has more than doubled from 14 days in the year ending March 2016 to 33 days in 2020 (Home Office, 2020c) (Figure 5). At the time of the 2017 reforms, the year-on-year change in median values for two of the most relevant (i.e. suspect identified) outcome groups – charged and victim does not support the investigation (suspect identified) – show little change between years ending March 2017 and 2018 (up one day in each case). However, given that these are England and Wales median values for all crime types, the figures will conceal more marked changes if analysed at a more granular level (see Martin, forthcoming).

Figure 5: Median time (in days) between offence recorded and outcome assigned, years ending March2016 to 2020

| Year ending March | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evidential difficulties (suspect identified; victim supports action) | 36 | 39 | 40 | 45 | 45 |

| Charge/summons | 14 | 17 | 18 | 23 | 33 |

| Evidential difficulties (victim does not support action | 16 | 14 | 12 | 16 | 15 |

| Investigation complete - no suspect identified | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

Source: Home Office (2020c)

Various factors are thought to have increased investigation durations this period: additional demands on the police, including more reporting of complex crimes, and the increased need to retrieve and examine digital evidence. Richardson et al. (forthcoming) showed that between 2010 and 2018, there had been a marked increase in the proportion of investigations with some element of digital evidence. And while this effect is most obvious in sexual offence cases, it is present across a wide range of crime types.

The College of Policing (2016) identified that forensic analysis was one of the key drivers behind long periods of PCB before the reforms. They found that 60% of cases over 90 days had some form of forensic samples as the reason for bail. They also found that the most frequent type of forensic analysis was ‘phone downloads’, with 33% of cases where suspects were bailed over 90 days giving this as the reason for extending bail. While ‘computer interrogation’ only accounted for 3% of cases it had the longest mean length of bail at 84 days. Some 63% of the cases where ‘computer interrogation’ was given as a reason related to rape or other sexual offences, while 10% related to fraud offences.

With digital forensic demands increasing and investigation durations extending, it has been suggested that officers simply know in advance that they will need to seek a magistrate’s extension after the initial three months’ extension to bail has elapsed. It is therefore easier for the police to release the suspect under investigation (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020; Martin, forthcoming).

The College of Policing (2016) also found that longer bail periods also reflected the need to obtain a witness statement from a third party, e.g. from a medical professional. Hales and Wiggett (2017) and Martin (forthcoming) made similar observations on the factors contributing to investigative delays.

5.8 The impact on suspects

Concerns regarding the impact that the 2017 bail reforms have had on suspects have also been raised (The Law Society, 2019). There are two main dimensions to the impact on suspects. First, that the large-scale shift to RUI has led to weaker communications between investigators and suspects; and, second, specific concerns around the monitoring of RUI suspects by forces, with potential issues around the handling of biometric samples. These impacts are closely linked to the impact on investigative management. Each is dealt with in turn.

While the reforms sought to reduce the duration of individuals on PCB, data suggest that these long durations in ‘limbo’ on PCB have, because of the reforms, simply shifted to suspects being RUI. Lengthy investigations can place a strain on suspects, victims, witnesses and families (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020). Moreover, the process of updating the suspect on the progress of the investigation, which was a legal obligation under PCB, is not a mandatory feature of RUI. Confusion has existed in some forces about who is responsible for providing updates to suspects about progress of the investigation (HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020). Under RUI, it has been suggested that suspects are simply not informed of the progress of the investigation (The Law Society, 2019).

The Biometrics Commissioner also identified some specific weaknesses around the PCB reforms and its impact on case management, and specifically around suspect management and the handling of forensic samples. In his 2019 annual report, it was noted that some forces could not provide data about the number of suspects RUI due to weaknesses in force monitoring of these cases. This was believed to indicate the problem faced by most forces that IT systems could not be adapted to record and monitor suspects released, unless they were on bail. HMICFRS/HMCPSI (2020) have also expressed concern about the lack of a recording system for RUI in many forces. This further raised issues around the management of biometric samples. A person with no other convictions where NFA was taken against them would normally, by law, have their biometrics deleted at this point if they were not held on bail. But because many forces’ IT systems had not been rapidly modified, the biometrics of suspects who are RUI could be being held unlawfully and as a result could produce unlawful forensic matches. Although progress was being made by forces (see HMICFRS/HMCPSI, 2020), the Commissioner was critical of the delays in the system updating two years after the PCB reforms (Wiles, 2020).

5.9 Voluntary attendance and pre-charge bail

Finally, it is important to touch briefly on the relationship between the PCB reforms and so-called voluntary attendance as an alternative to arrest. Prior to the 2012 changes to Code G of PACE, suspects being investigated by the police for criminal offences were, when sufficient grounds were present, arrested for criminal offences. Since the revised Code G was introduced, the use of arrest has declined. Suspects who are not arrested may be asked to attend voluntarily, at a specific time and place (usually at a police station), to answer police questions. This is called voluntary attendance (VA) or voluntary interviews. It has been estimated that, overall, around one-third of those investigated as suspects are now subject to VA, rather than being arrested (Wiles, 2020).

The precise nature of the interaction between the growth in VA numbers and the PCB reforms is difficult to disentangle. Growth in the use of VA has been criticised by victims’ groups (e.g. The Centre for Women’s Justice, 2019) as, prior to the reforms, its use was likely to have independently led to reductions in using bail (since bail could only be granted to arrestees). And others have been critical of the increased use of VA for offences which might be expected to yield an arrest – sexual offences and violent offences – because they preclude the taking of biometric samples pre-charge (Wiles, 2020). National figures on VA by offence type are limited but ONS has published figures from HMICFRS on arrests and VAs for domestic abuse-related crimes in the year ending March 2019 (ONS, 2019). For 27 forces that provided arrest and VA data, there were approximately 150,300 arrests and 21,300 VA for domestic abuse-related crimes in the year ending March 2019 (ibid.). It has been suggested that the reduction in the use of bail with conditions post-reform has made VA appear relatively more attractive compared with arrest as the advantages of arrest over VA diminish if the ability to apply bail with conditions is less commonly available (Wiles, 2020). Increased use of VA may also have other consequences on suspects, victims and investigative management. However, data quality on VA is not sufficient to assess this.

6. Concluding remarks