Ransomware legislative proposals: reducing payments to cyber criminals and increasing incident reporting (accessible)

Updated 2 September 2025

To: This consultation is open to the public.

The government is particularly interested to hear from those who anticipate being required to comply with the proposals, those in Industry and Research as well the general public.

Duration: From 14 January to 8 April 2025

Enquiries to: Ransomware Legislative Proposals Consultation Homeland Security Group

Home Office

5th Floor

Peel Building

2 Marsham Street London

SW1P 4DF

ransomwareconsultation@homeoffice.gov.uk

How to respond

Please provide your response by 17:00 on 8 April 2025 at: https://www.homeofficesurveys.homeoffice.gov.uk/s/E6ROXH/

If you are unable to use the online system, for example because you use specialist accessibility software that is not compatible with the system, you may download this form and email or post it to the above contact details.

Please also contact the above details if you require information in any other format, such as Braille, audio, or another language.

We may not be able to analyse responses not submitted in these provided formats. Response paper: A response to this consultation exercise will be published in due course.

Introduction

1. For the purposes of this consultation, the Home Office views ransomware as:

2. A type of malicious software (“malware”) that infects a victim’s computer system(s). It can prevent* the victim from accessing system(s) or data, impair the use of system(s) or data and/or facilitate theft of data held on the victim’s networked systems or devices. A ransom is demanded (normally payment of cryptocurrency) from the victim to regain access to the system(s); for data to be restored; or for data not to be published on criminal-operated data leak websites.

3. *This includes but is not limited to encryption.

4. The targets of ransomware can range from ordinary individuals using their home computers and other personal devices, to major companies and public bodies whose entire systems and networks are put under attack.

5. For the serious and organised crime gangs behind the global fraud industry, ransomware is an increasingly lucrative part of their operations, with industry estimates suggesting that ransomware criminals received more than $1 billion from their victims globally in 2023. [footnote 1]

6. In the UK, ransomware is considered the greatest of all serious and organised cyber crime threats, the largest cyber security threat, and is treated as a risk to the UK’s national security by the National Crime Agency (NCA) and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).[footnote 2]

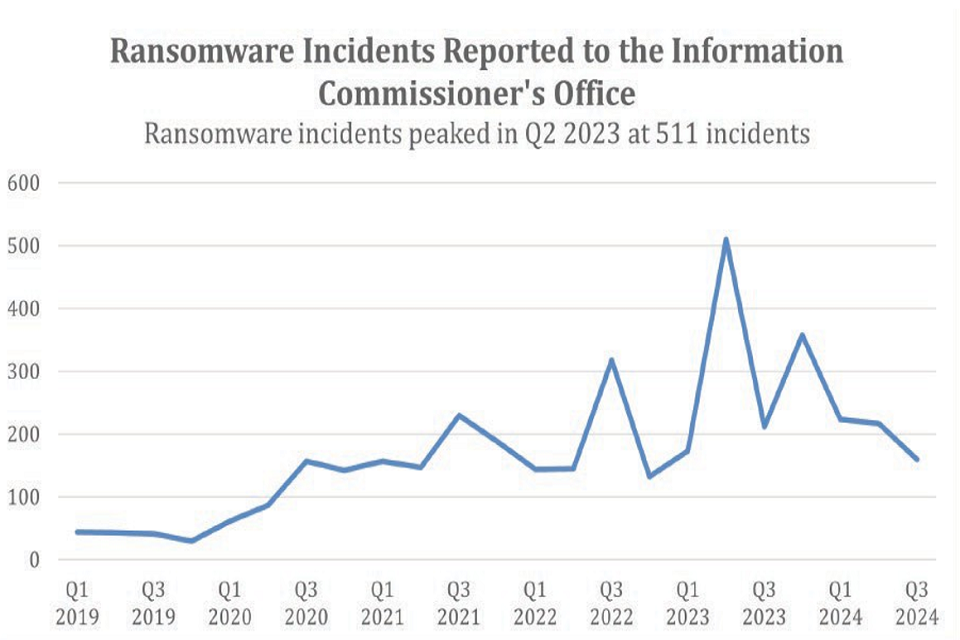

7. In 2023, incidents of ransomware attacks reported to the Information Commissioner’s Office reached their highest level since 2019 [footnote 3] and private sector reporting to the National Crime Agency indicates that the number of UK victims appearing on ransomware data leak sites has doubled since 2022[footnote 4]. Home Office polling shows that nearly three quarters (74%) of the public are aware and concerned about the threat of ransomware occurring in the UK.[footnote 5]

8. In recent years, there have been several high-profile cases where organisations like the NHS, the Guardian and the British Library have been subject to ransomware attacks – causing serious short-term disruption to their systems and to the individuals reliant on their services.

9. However, for every case that has hit the headlines, there are thousands of others where private sector firms have been prevented from doing business, or where members of the public have had to deal with the distress of having their privacy and personal data breached.

10. For any such organisations or individuals, it may seem like a necessary evil to pay a ransom to relieve themselves from the disruption and intrusion they are facing. From a societal point of view though, this only serves to reinforce the business model of the criminal gangs responsible and makes the practice of ransomware more lucrative and widespread.

11. Home Office polling shows that more than two-thirds of the public agree that it is wrong for a business to pay a ransom because that ransom could be used by attackers to fund more criminal activities.[footnote 6]

12. Reducing the spread of ransomware attacks, and undermining the criminals’ business model, requires an entirely new approach, and one that will help the UK to lead the world in fighting back against the increasing risks posed by this crime to our society and economy.

The impact of ransomware

13. There are a range of factors that we need to consider when assessing the damage that ransomware does to our society and economy: most important are the impact on individual victims; the consequences for businesses, public bodies, and their clients; the wider criminal harms arising from ransomware attacks; and the effect on confidence in online activity:

-

a. Academic research based on interviews with victims and incident reporters has highlighted the wide range of the damage caused by ransomware attacks, including physical, financial, reputational, psychological, and social harms [footnote 7]. This research aligns with findings from in-depth interviews conducted by the Home Office which explored the experience and impacts of ransomware attacks for individuals and businesses, including examining the financial and non-financial costs faced by victims.[footnote 8]

-

b. In some cases, the significant costs and losses caused to organisations by the disruption of a ransomware attack can threaten their very existence, with instances of organisations permanently ceasing to trade as a result (see case studies below). The Home Office’s research with victims found that financial costs can be both direct and indirect, with some organisations needing to pay significant amounts for external technical, legal or PR support.

-

c. There can also be high costs to the clients of businesses and public bodies from the closure or disruption of services, something seen most visibly to date when the systems of healthcare or transport organisations have been affected, leading to the cancellation of appointments or key services. The costs faced by business in responding to ransomware attacks could also end up being passed on to consumers.

-

d. As well as profiting from the payment of ransoms, academic research indicates that criminals could either directly sell the data that they steal in online marketplaces[footnote 9] or use it themselves for other malicious purposes. This can include card-not-present fraud, digital identify theft, the creation of false accounts, or breaking a password or username recovery process to takeover an existing digital or bank account.[footnote 10]

-

e. As organisations increase the volume and type of data, they collect on their customers to feed proprietary algorithms (including behavioural, attitudinal and engagement data, or tracking and real-time location data), there is also an increasing risk that ransomware attackers will steal and sell this data to other criminals or states to facilitate further serious crime and harm to individuals.[footnote 11] [footnote 12]

-

f. Academic research has also highlighted the wider impact of ransomware attacks on society, the economy and national security. [footnote 13] They can undermine confidence and lead to avoidance of using online services and engaging with the wider world over the Internet,[footnote 14]which can lead to complacency around online security and fatigue around the importance of data privacy.[footnote 15]

Case Studies

14. A scenario-based model by the Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies analysed possible harms of an attack on UK critical national infrastructure (CNI) via the South East electricity distribution network. The report calculated sector direct losses to production due to lost power of between £7.2bn and £53.6bn with a central estimate of £18.1bn based on response time.[footnote 16]

15. The report scenario was not ransomware specific, focussing instead on the possible impacts of wider malicious cyber activity, so whilst it cannot necessarily be directly extrapolated to a ransomware attack, it provides a useful sense of magnitude for a worst-case scenario.

16. In addition, we now have a sufficient body of real-life incidents where organisations in the UK were affected by ransomware attacks to inform the magnitude of harms to organisations that may result if those attacks are allowed to continue:

17. In September 2023, KNP Logistics Group, one of the UK’s largest privately owned logistics groups, blamed a ransomware attack suffered three months earlier for its insolvency, with the loss of more than 700 jobs in the process.[footnote 17] Foreign exchange firm Travelex also collapsed into administration six months after a ransomware attack at the end of 2019, with administrators citing the impact of the attack as a key factor.[footnote 18]

18. On 3 June 2024, a ransomware attack on a pathology service joint NHS-private venture led to elective procedures, including surgeries and cancer treatment, being postponed and some services having to be diverted to other hospitals.[footnote 19] Up to 26 September 2024, NHS data showed 10,152 acute outpatient appointments and 1,710 elective procedures were postponed at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, as a result of the disruption.[footnote 20]

19. Other specific examples of recent UK-focussed ransomware incidents that highlight the need for action in this area include:

-

a. Royal Mail ransomware attack (January 2023) – domestic and international operations were affected for several weeks when hit by the Russian cyber- crime group LockBit.

-

b. Capita breach (March 2023) – this ransomware incident compromised sensitive data affecting pensions nationwide. Capita reported that they expected associated costs to be around £15m to £20m. [footnote 21]

-

c. British Library (October 2023) – a ransomware group posted approximately 600GB of data, including staff and user personal data, on the dark web. Following the cyber attack, research services were severely restricted for two months, with full recovery taking even longer. [footnote 22]

-

d. NHS Dumfries & Galloway (March 2024) – a ransomware group posted three terabytes of stolen patient data on the dark web.

Box 1: The LockBit Network

Over a four-year period from 2020-24, the Russian-based LockBit organisation became the most prolific and harmful facilitator of ransomware attacks worldwide, targeting thousands of victims and causing losses of billions in ransom payments and recovery costs. Their main business was selling so-called ‘affiliates’ the tools and infrastructure required to carry out their own attacks, a practice known as ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS).

In common with other ransomware attacks, when a victim’s network was infected by LockBit’s malicious software, their data was stolen, and their systems encrypted. A ransom would be demanded in cryptocurrency for the victim to decrypt their files and prevent their data from being published. Investigations have shown that, even when ransoms were paid, Lockbit continued to hold and exploit for gain the data stolen in various attacks.

The UK’s National Crime Agency, working closely with the FBI, and supported by partners from nine other countries, led the covert investigation of LockBit as part of a dedicated taskforce called Operation Cronos. That culminated in February 2024 with investigators infiltrating and taking control of LockBit’s online infrastructure, as seen below.

Note: a screenshot of the landing page that users would find when attempting to access Lockbit services. Image has pictures of the flags from the countries involved and shields/logos of their law enforcement. Countries are: the UK, USA, France, Japan, Switzerland, Canada, Australia, Sweden, the Netherlands, Finland and Germany.

As a result of this operation, dozens of LockBit’s affiliates were also put out of action, hundreds of cryptocurrency accounts were frozen, at least twenty individuals connected to the LockBit network have had personal sanctions imposed on them, and several other individuals have been arrested by law enforcement partners in Eastern Europe.

In May 2024, one of the previously anonymous leaders of the LockBit network, Dmitry Khoroshev, was publicly unmasked and sanctioned by the UK, US and Australia, with the FBI offering a $10m reward for information leading to his arrest and/or conviction.

Just as important as the action taken to dismantle LockBit’s criminal enterprise and target the individuals behind it, the investigators were also able to provide peace of mind to many of the network’s previous victims by retrieving and destroying the data illegally acquired by LockBit and their affiliates during past ransomware attacks.

Ransomware – the threat landscape

20. The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) maintains reports of data security breaches, including ransomware incidents experienced by organisations. The data in figure 1 below from the ICO suggests that incidents of ransomware attacks are increasing, with ransomware incidents reported to the ICO peaking at 511 in the second quarter of 2023. [footnote 23] Figure 1. Ransomware incidents reported to the Information Commissioner’s Office

21. The wider evidence base on the scale of ransomware attacks is limited due to factors such as the general underreporting of cyber crime and the sophisticated nature of ransomware attacks. However, other evidence gives some indication of the extent of victimisation.

22. Private sector reporting to the National Crime Agency indicates the number of UK victims appearing on ransomware data leak sites has doubled since 2022.[footnote 24]

23. The Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2024,[footnote 25] which explores the cost and impact of cyber breaches and attacks on businesses, charities, and educational institutions, found that half of businesses reported experiencing at least one cyber attack, of which six per cent identified their organisation’s devices being targeted with ransomware.

24. The Crime Survey for England and Wales [footnote 26] estimated that there was a ‘demand for money to release files’ – a proxy indicator for ransomware – in three per cent of computer virus incidents against individuals in the year to March 2023.

25. Home Office polling with the UK general public [footnote 27] also suggested that approximately 11 per cent of the public had indirect experience of ransomware, reporting that the organisation where they work, or an organisation they are a customer of, had experienced a ransomware attack.

26. The National Cyber Security Centre assess that ransomware is a financially motivated crime, largely committed by cyber criminals. These criminals are assessed to be predominantly based overseas, in Russia and other jurisdictions that do not routinely cooperate with UK law enforcement. They are not typically directed by their host states but operate as part of organised crime groups or networks. These criminals have the capacity to severely impact the UK’s most critical assets and services, meaning ransomware poses a threat to the UK’s national security.

27. The proceeds of these crimes are largely transferred through cryptocurrency, which has made purchasing criminal services and receiving payments easier, cheaper, and faster and creates challenges in identifying individuals and controlling illicit payments. [footnote 28] The financial incentive driving ransomware attacks is also likely to grow further as digitalisation continues, and more organisations of all kinds store valuable data that can be targeted and extorted.

28. There are many business models available to ransomware actors, but the most common business model is ‘ransomware as a service’ (RaaS). In this model organised crime groups provide other cyber criminals with malware to orchestrate an attack anonymously for a cut of the ransom payment. The introduction of RaaS has lowered barriers to entry and makes it possible for any criminal to cause widespread harms without advanced technical skills.[footnote 29]

29. In response, law enforcement has evolved their response to ransomware attacks and the cyber crime ecosystem and have proven their ability to go after the networks at the root of ransomware attacks with notable examples such as LockBit and Evil Corp (see Boxes 1 & 2). However, the combined challenges of overseas impunity, anonymity and traceability of finance currently make ransomware very difficult to reduce through law enforcement.

30. We must therefore consider what action we can take as a country to improve the ability of UK law enforcement agencies to identify new patterns and threats in this area, enable intelligence gathering and investigation of ransomware attacks as they are taking place, and use that intelligence to work with international partners and take down the gangs responsible.

31. But ultimately, it is also clear that this type of crime only works if the potential victims are willing to pay the ransom that the gangs demand. Academic research suggests that criminals operating in this area will assess the level of ransom they can set, and the profit they will expect to make, against the probability that the victim will pay. Criminals may refine their techniques and learn better strategies to maximise profit, including offering victims a range of options at different prices or give different victims different prices.[footnote 30]

32. It follows that – beyond anything we can achieve through better law enforcement alone – by disrupting the business model of the ransomware gangs, we hope to reduce the likelihood in their minds that they will succeed in obtaining a ransom payment if they target individuals and organisations in the UK.

Box 2: The EvilCorp Group

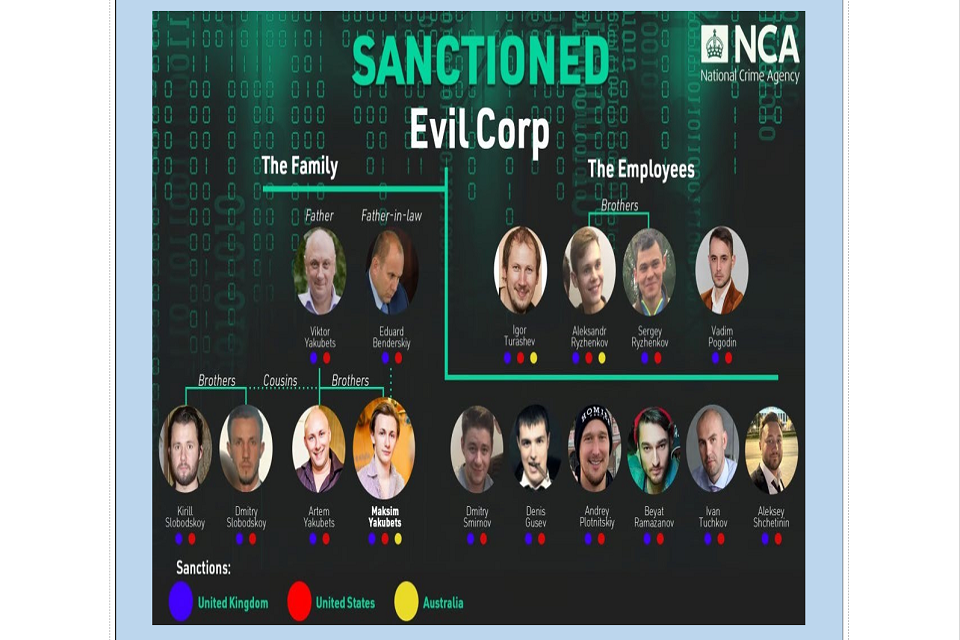

Evil Corp formed as a Moscow-based financial crime group in 2014, soon branching into cyber crime. They lead the development and distribution of malware and ransomware used to extort at least $300 million from their victims around the world, ranging from banks to hospitals. Alongside their own ransom activities, they were tasked with conducting cyber- attacks and espionage on behalf of the Russian Intelligence Services, an indication of the close links to the Russian state that helped fuel their rise in the late 2010s.

An extensive investigation by the National Crime Agency during that period helped map out the history and reach of Evil Corp’s criminality and contributed directly to the decision by US authorities in 2019 to indict and sanction the head of Evil Corp, Maksim Yakubets, and several other members. This caused considerable disruption to Evil Corp, damaging their ability to operate, and making it harder to elicit ransom payments from their victims.

While some members of the group continued to develop high-profile malware and ransomware strains, such as WastedLocker and Hades, the group’s tactics changed to evade law enforcement scrutiny, switching from volume attacks to targeting high-earning organisations. Other members moved away from using their own technical tools, instead using ransomware strains developed by other crime groups, such as LockBit.

The NCA continued to monitor Evil Corp’s activities, and their analysis contributed to the announcement in October 2024 of further coordinated action by the UK, US and Australia against members of the group. For the UK, that included sanctions which impose asset freezes and travel bans on 16 individuals linked to Evil Corp and its activities, including nine actors sanctioned by the US in 2019, along with an additional seven individuals, whose links to the group had not previously been exposed. These sanctions and the accompanying assessment publicly highlighted the links between the group members, the evolution of their activities and links to both the Russian State and other ransomware actors, such as LockBit (earlier disrupted by sanctions and law enforcement efforts under Operation Cronos).

An organogram of EvilCorp members including a family tree of some of the members. Those sanctioned include: Viktor Yakubets; Eduard Benderskiy; Kirill Slobodskoy; Dmitry Slobodskoy; Artem Yakubets; Maksim Yakubets; Igor Turashev; Aleksandr Ryzhenkov; Sergey Ryzhenkov; Vadim Pogodin; Dmitry Smirnov; Denis Gusev; Andrey Plotnitskiy; Beyat Ramazanov; Ivan Tuchkov; Sleksey Shchetinin.

The action taken against leading members of Evil Corp will further damage a group through operational disruptions and a very public illumination of the threat. Action like this helps to impose cost, build awareness of the threat, and remove the comfort of anonymity of these actors who like to hide in the shadows. By further identifying links to other actors and the State, we disrupt the hostile network and toxic ecosystem that enables their activities.

Purpose of this consultation

33. Based on the analysis above, the Home Office has three immediate, overarching objectives when it comes to our work in this area:

- a. Reduce the amount of money flowing to ransomware criminals from the UK, thereby deterring criminals from attacking UK organisations.

- b. Increase the ability of operational agencies to disrupt and investigate ransomware actors by increasing our intelligence around the ransomware payment landscape.

- c. Enhance the Government’s understanding of the threats in this area to inform future interventions, including through cooperation at international level.

34. The Home Office have set out three specific proposals in this document designed to achieve these objectives, that are likely to be applicable across the UK. We are seeking feedback on the proposals before we decide to go ahead with their implementation, and we will also use the evidence from this consultation to support future advice and guidance for the victims of ransomware.

35. The key aim of these proposals is to protect UK businesses, citizens and CNI, whether UK owned or not. We would therefore particularly welcome responses from organisations with global and multi-national structures to ensure that we can protect UK customers and suppliers who interact with their services. We are keen to understand how we can best apply these proposals alongside broader corporate and data requirements, such as the UKGDPR.

36. This consultation will tackle difficult questions about victim behaviour during a cyber incident; how much information can and should be shared with UK authorities; and if and when it is appropriate to pay a ransom. The proposed measures reflect the seriousness with which ransomware is taken by this Government and reflects an ambition to drastically reduce the harm caused to UK prosperity and security by ransomware attacks. Inputs to this consultation will support the development of the best possible measures to achieve this goal.

Box 3: The Counter Ransomware Initiative

While this consultation document focuses on the action the Home Office proposes to take within the UK to tackle the threat that our own citizens, businesses and public bodies face as a result of ransomware, we are also playing a leading role in coordinating the global response to this type of crime, working with our partners overseas.

The Counter Ransomware Initiative (CRI) was created in 2021 and is the only dedicated multilateral forum for international partners to come together to develop new approaches and processes to combat ransomware. The UK serves alongside Singapore as the co-lead for policy development, and the two countries led the forum towards a groundbreaking joint statement in 2023 denouncing ransomware payments and confirming, for the first time, that no central government funds should be used to pay ransomware demands.

In October this year, the UK again helped lead efforts at the CRI to endorse new guidance drawn up in concert with the global insurance industry, encouraging organisations to carefully consider their options instead of rushing to make payments to cyber criminals in an attempt to stop disruption and data loss, and making clear that paying a ransom will often only embolden these criminals to target other victims, with no guarantee of data retrieval, malware removal or the end of a ransomware attack.

Instead, the guidance encourages organisations to report attacks to law enforcement authorities, check if data backups are available and get advice from recognised experts. The UK joined with 39 other CRI members and 8 global insurance bodies to endorse the guidance, the objectives of which strongly echo the purpose of this consultation to undermine the business model of ransomware criminals and take away the financial incentive for them to target organisations with their attacks.

Proposals for consultation

37. The Home Office has developed the consultation objectives through an evidence- based approach, supported by other government departments and agencies, industry experts and leading think tanks. In the course of those discussions, some stakeholders proposed a greater focus on resilience measures (e.g. better computer security and backup systems) and others urged stricter controls over the use of cryptocurrencies.

38. The Home Office appreciates these representations, and we are particularly supportive of continued efforts to build greater resilience. However, we believe these should be undertaken in conjunction with additional measures, as set out in this consultation, which aim to provide rapid, targeted and effective action by helping to break the ransomware business model. These proposals draw on international successes and insights gained from the UK’s leading role in the international Counter Ransomware Initiative – see Box 3 above.

39. Any legislation flowing from this consultation process will be introduced in conjunction with comprehensive communications, ongoing industry engagement, and voluntary measures such as recent guidance issued by the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and the insurance industry, advising against the making of ransom payments.

40. Proportionality is at the core of all of the reporting proposals in these measures. The intent is to ensure that UK victims are only required to report an individual ransomware incident once, as far as possible, to avoid unnecessary burdens. The Home Office will work with DSIT to ensure that these proposals and those in the upcoming Cyber Security and Resilience Bill are aligned and complementary, ensuring these two regimes do not create duplication and are simple and clear for organisations in scope.

41. For the purposes of this consultation, any reference to “economy-wide” is taken to mean applicable to any individual or organisation in the UK who suspects they are a victim of a ransomware attack regardless of organisational size or sector. However, as set out in the discussion below, a key objective of this consultation is to get the balance right between making these proposed measures as comprehensive and impactful as possible, while not creating unreasonable or disproportionate burdens on ordinary individuals and organisations.

42. The three proposals are:

- targeted ban on ransomware payments for CNI and the public sector

- ransomware payment prevention regime

- ransomware incident reporting regime

Consultation Proposals

Proposal 1

Targeted ban on ransomware payments for all public sector bodies, including local government, and for owners and operators of Critical National Infrastructure, that are regulated, or that have competent authorities.

Proposal details

43. Our central goal is to protect the UK’s public services and critical national infrastructure (“CNI”) from the disruption caused by ransomware attacks. Home Office polling shows that the UK public share that objective, with their highest levels of concern about the possibility of a ransomware attack focused on national infrastructure (84%) and UK government agencies (79%). [footnote 31] We believe that one of the most effective ways of preventing ransomware attacks is to ensure that the criminal gangs looking to target our essential agencies and infrastructure know they will make no money from doing so.

44. This proposal would go beyond our current principle that central government departments cannot make ransomware payments by prohibiting all organisations in the UK public sector (including local government), and CNI owners and operators (in sectors defined by the National Protective Security Authority, [footnote 32] subject to regulation/competent authorities) from making a payment to cyber criminals in response to a ransomware incident. The Home Office is seeking views as to whether essential suppliers to these sectors should also be included. This would extend our current principle that central departmental funds cannot be used to pay a ransomware payment to all publicly funded bodies. Numerous countries have affirmed this principle through the Counter Ransomware Initiative statement, expressing their intention to not make ransom payments.[footnote 33]

45. We are also seeking views on how to achieve the right balance of effective and proportionate measures to encourage compliance with the proposed ban, ranging from criminal penalties (such as making non-compliance with the ban a criminal offence) or civil penalties (such as a monetary penalty or a ban on being a member of a board). The Home Office welcomes views on other measures that could be used to encourage compliance with the ban.

Background to proposal

46. Ransomware is distinct from other forms of cyber crime due to its direct financial extortion model, where the profit is directly tied to securing payment from victims. This model drives the continual evolution and persistence of ransomware attacks. Figure 2 is a simplified diagram of the ransomware payment cycle, from the US Institute for Science and Technology. [footnote 34]

The ransomware payment cycle:

- Attack

- Ransom negotiation

- Ransom payment

- Obfuscation of funds

- Cash out

- Resourcing

47. Breaking this payment cycle is essential to disrupting the ransomware business model, and the Home Office is focussing on steps 2 and 3 with this proposed ban. Ransomware attacks are complex, and the movement of illicit funds can happen quickly. Cyber criminals are increasingly using sophisticated technologies and techniques to move and hide the flow of their illicit funds.[footnote 35] Disrupting the payment cycle stops these funds moving into the hands of criminals and prevents them from growing and developing their operations.

48. We have seen that attacks which do not lead to payment are unattractive propositions for ransomware criminals. Data from the NCA-led investigation into the LockBit network, as discussed in Box 1 above, reiterated this.

49. By restricting ransomware payments, the Government is seeking to affirm a non- payment position as a public and binding commitment. Ransomware criminals will be critically aware of this when conducting attacks. This would cement the UK, and our essential infrastructure, as an unattractive target to criminals by making clear that our organisations do not pay ransoms.

Proposal 2: A new ransomware payment prevention regime

To cover all potential ransomware payments from the UK.

Proposal details

50. In Home Office polling carried out in 2024, the public were presented with a range of scenarios regarding the payment of a ransom, including what might happen in the event of payment. 68 per cent of the public believed that it is wrong for a business to pay a ransom because that ransom could be used by attackers to fund more criminal activities.[^36]

51. The Home Office is proposing to introduce a payment prevention regime, which would require any victim of ransomware (organisations and/or individuals not covered by the proposed ban set out in Proposal 1), to engage with the authorities and report their intention to make a ransomware payment before paying over any money to the criminals responsible.

52. After the report is made, the potential victim would receive support and guidance – including the discussion of non-payment resolution options, and the authorities would review the proposed payment to see if there is a reason it needs to be blocked, e.g. where it could go to criminals subject to sanctions designations, or in violation of terrorism finance legislation. If the proposed payment is not blocked, it would be a matter for the victim whether to proceed.

54. The information provided through the initial reports, and any further engagement with the authorities, may feed into the intelligence used to support operational activity and contribute to major investigations such as that carried out into LockBit and Evil Corp (see Boxes 1 & 2).

55. Through this proposal, we are seeking both to improve our understanding of the ransomware payment landscape, and to influence victim behaviour and experience, by providing victims with advice and guidance before they decide whether to make a ransomware payment. Figure 3 is an initial illustration of how this regime may work:

Figure 3. Illustration of ransomware payment prevention regime

Step 1 - Victim reports intention to make ransom payment

Step 2 - Government reviews payment and opens dialogue with victim

Step 3 - If appropriate, operational partners are made aware of the intention to make a payment and may offer victim support or guidance.

Step 4 - Government confirms to victim if there is a reason to block the payment.

Background to proposal

55. Currently, law enforcement and operational partners do not have a complete view of the ransomware payment landscape, i.e. who is making payments, who the money is going to, when, why, and for how much. This impacts our understanding of the threat and opportunities for intervention. We are seeking to change this, building on existing guidance [footnote 37] and arrangements facilitated by the National Cyber Security Centre.[footnote 38]

56. As outlined above, the Home Office believes it is important to discourage organisations from paying ransoms to disrupt the ransomware business model and break the cycle of attacks. The Cyber Security Breaches Survey (2024) reported that almost half of businesses (48 per cent) have a policy not to pay ransoms.[footnote 39]

57. However, it is recognised there are circumstances where businesses of many kinds may feel that they need to pay a ransom. That decision will often result from weighing up several competing factors and can be a ‘cost/benefit’ decision, with reputational damage, impact on business continuity, and size of ransom all taken into account [footnote 40] [footnote 41] [footnote 42].

58. Some businesses may also feel that they are genuinely faced with no choice but to pay or see their business fold. Others may feel that the harm that would arise if their stolen data was released into the public domain is greater than the harm of paying the ransom, albeit the National Cyber Security Centre [footnote 43], National Crime Agency [footnote 44] and Information Commissioner’s Office [footnote 45] have stressed that paying a ransom is no guarantee of protecting the data at risk.

59. As the National Crime Agency said after leading the operation which dismantled the LockBit network, “some of the data found on LockBit’s systems belonged to victims who had paid a ransom to the threat actors, evidencing that even when a ransom is paid, it does not guarantee that data will be deleted, despite what the criminals have promised.” [footnote 46]

60. In Home Office polling carried out in 2024, the public were presented with a range of scenarios regarding the payment of a ransom, including what might happen in the event of payment. 68 per cent of the public believed that it is wrong for a business to pay a ransom because that ransom could be used by attackers to fund more criminal activities. [footnote 47] When we asked more detailed questions about whether this would depend on the characteristics of the business or reason for paying the ransom, there was a greater degree of public uncertainty over the right approach. [footnote 48]

61. The Home Office is keen to hear views on the best measures for encouraging compliance with this regime, such as whether to impose criminal and/or civil penalties for non-compliance, especially where a payment is made after the victim has been told it has to be blocked, and whether this regime and any accompanying compliance measures should apply to all potential victims – including smaller businesses, charities and members of the public – or whether a higher threshold should be set for the size of the organisation and/or the amount of the ransom demanded.

62. The Home Office also welcomes views on what additional support and/or guidance should be provided to encourage compliance with the regime, potentially building on existing collaboration between the National Cyber Security Centre and Information Commissioner’s Office. A statement made by these organisations sets out that the ICO will “consider early engagement and co-operation with the National Cyber Security Centre positively when setting its response.”[footnote 49]

Proposal 3: A ransomware incident reporting regime

That could include a threshold-based mandatory reporting requirement for suspected victims of ransomware.

Proposal details

63. The more that we understand the scale, type and source of the ransomware threats that individuals and organisations in the UK are facing, the better able the Home Office will be to:

- Keep our advice and guidance for victims fit for purpose and up to date.

- Ensure any future ransomware interventions are appropriate and effective.

- Support organisations in growing their resilience and preventing future attacks.

- Compile the intelligence and evidence that our law enforcement agencies need to disrupt and dismantle ransomware gangs and sanction their operatives.

64. In keeping with those objectives, the Home Office wishes to consult stakeholders on the proposed introduction of a ransomware incident reporting regime for suspected victims of ransomware. We are exploring whether this should be economy-wide, or whether it should only impact organisations and individuals meeting a certain threshold. The reporting requirement would apply regardless of the victim’s intention to pay the ransom. If the mandatory reporting requirement is brought in with a threshold, we would continue to encourage all victims of a ransomware incident to report through the same mechanism.

65. For victims subject to the mandatory reporting requirement, the below diagram, figure 4, illustrates the proposed process:

Who would the report be to?

- to the relevant part of government

- reports would be dealt with confidentially across the government with information shared only when necessary

What would victims be required to report?

An initial report that an incident has happened, including:

- if a ransom demand has been received

- if the organisation can recover from existing resilience measures

- if the ransomware group is identifiable at this stage

A detailed report with further details including:

- the vector of access

- if resilience measures have been implemented

- any further details on the attack

How long do victims get to report?

- initial report within 72 hours

- full report within 28 days

66. Home Office polling indicates high levels of agreement amongst the public that businesses should report a ransomware attack, with 81 per cent of the public believing that a business should report the attack, even if they can resolve it on their own [footnote 50].

67. In addition to this, qualitative Home Office research [footnote 51] has found that some individual victims and sole traders were not aware that reporting ransomware attacks was an option and did not know how or where they could do so. There was also evidence that victims did not understand the severity of the attack or importance of reporting ransomware, even if they had successfully regained control over their systems after an attack. Any new reporting regime would therefore be accompanied by comprehensive public communications to explain the regime and its benefits.

68. The intent is to ensure that UK victims are only required to report an individual ransomware incident once, as far as possible. Reporting required under this regime would be deconflicted from the proposed reporting required under the Ransomware Payment Prevention Regime. The Home Office is aware of additional reporting requirements, for example for organisations subject to the Network Information System Regulations. The Home Office will work with other Government Departments to consider the deconfliction of reporting requirements during the development of any legislation.

Background to proposal

69. The current underreporting of ransomware attacks creates a substantial and avoidable gap in our intelligence picture regarding the scale and source of ransomware attacks on the UK and affects the ability of law enforcement agencies to target their investigations to maximum effect.

70. It follows that – besides not putting more money into the hands of criminals by paying ransoms – the most helpful contribution that organisations and individuals can make to our collective fight against ransomware is to report every attack they suffer. That is regardless of whether or not they intend to make a payment. The information about those attacks contributes to our analysis of the ransomware landscape.

71. Research has found that businesses will sometimes consider reporting a ransomware attack to the authorities but decide against it; reasons include because they are embarrassed, or because of a perceived burden on law enforcement, or because they think it is only necessary if they are in need of recovery assistance. [footnote 52] Reporting decisions can be affected by victims’ perceptions of what will happen if they report, rather than what is likely to happen in reality, and a lack of awareness of reporting routes can also be a potential blocker.[footnote 53]

72. The reporting gap is particularly acute in cases where victims are able to recover from the attack quickly using backups and alternative measures, and therefore never have to consider making a ransomware payment. While operational agencies are keen to encourage offline backups, resistant cloud back-ups [footnote 54] and good cyber hygiene to assist in rapid recovery[footnote 55], it is important that those organisations with strong resilience against ransomware attacks also recognise the collective benefit we all gain from them reporting those attacks.

73. Reporting regimes for cyber incidents in other countries vary in the criteria applied – for example, by size of organisation; the depth of information demanded at different times after an incident; and to whom incidents are reported. Alongside our analysis of the responses to this consultation, the Home Office will consider what best practice is available from other countries, particularly in considering the scope for any mandatory reporting regime.

Ransomware Public Consultation Privacy Notice

How and why your data is being used:

The Home Office has developed three new ransomware-focused measures, aiming to tackle the issue of ransomware. This consultation is seeking feedback on these three proposals.

The Home Office will collate and analyse responses on respondents’ views on new proposed measures. The Home Office will use the responses to develop understanding and impact of the suggested proposals and to develop legislation if necessary. We will summarise all responses and publish this summary on GOV.UK.

The Home Office collects and processes personal information to fulfil its legal and official statutory functions. We will only use personal information when the law allows us to and where it is necessary and proportionate to do so.

The Home Office is only allowed to process your data where there is a lawful basis for doing so. We have systems and policies in place to limit access to your information and prevent unauthorised disclosure. Staff who access personal information must have appropriate security clearance and a business need for accessing the information, and their activity is subject to audit and review. The lawful basis for the collection and processing of this data is Article 6(1)(e) of the UK GDPR processing is necessary for a performance of a public task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.

More information about the ways in which the Home Office may use your personal information, including the purposes for which we use it, the legal basis, and who your information may be shared with can be found at Information rights privacy information

Storing your information

Your personal information will be held for as long as necessary for the purpose for which it is being processed and in line with departmental retention policy. For a consultation data will be destroyed 5 years after the project has closed. More details of this policy can be found at What to keep: Home Office retention and disposal standards - GOV.UK.

Confidentiality

Information provided in response to this consultation, including personal information, may be published or disclosed in accordance with the access to information regimes (these are primarily the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), the Data Protection Act 2018 (DPA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Environmental Information Regulations 2004).

If you want the information that you provide to be treated as confidential, please be aware that, under the FOIA, there is a statutory Code of Practice with which public authorities must comply and which deals, amongst other things, with obligations of confidence. In view of this it would be helpful if you could explain to us why you regard the information you have provided as confidential. If we receive a request for disclosure of the information we will take full account of your explanation, but we cannot give an assurance that confidentiality can be maintained in all circumstances. An automatic confidentiality disclaimer generated by your IT system will not, of itself, be regarded as binding on the Home Office.

The Home Office will process your personal data in accordance with the Data Protection Act 2018.

Requesting access to your personal data

You have the right to request access to the personal information the Home Office holds about you. Details of how to make the request can be found at Personal information charter - Home Office - GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

Your personal information, supplied for the purposes of this consultation, will be held and processed by the Home Office. The Home Office is the controller of this information. Contact the Ransomware Legislative Proposals Consultation Team for questions relating to the consultation:

Ransomware Legislative Proposals Consultation Homeland Security Group

Home Office

6th Floor

Peel Building

2 Marsham Street London

SW1P 4DF

Email Address: ransomwareconsultation@homeoffice.gov.uk

Questions or concerns about personal data

The Home Office has a Data Protection Officer who can be contacted if you wish to complain how the Home Office has managed and used your personal data. Details of the Department’s Data Protection Officer can be found at dpo@homeoffice.gov.uk.

Or write to:

Office of the DPO Home Office Peel Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

You have the right to complain to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) about the way the Home Office is handling your personal information. Details on how you do this can be found at Make a complaint - ICO.

To protect your privacy please avoid including any personal information in any free text boxes, such as names, addresses, phone numbers, or email addresses.

About the questionnaire and how the data will be used

The survey will take approximately 30-40 minutes to complete, depending on how much detail you give.

Please submit your response by 8 April 2025.

To help us analyse the responses please use the online system wherever possible: https://www.homeofficesurveys.homeoffice.gov.uk/s/E6ROXH/

This research is being conducted by the Home Office to understand views towards the Ransomware Legislative Proposals.

The privacy notice can be found here: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/ransomware-proposals-to-increase-incident-

This notice reflects your rights under data protection legislation including the UK General Data Protection Regulation and lets you know how the Home Office looks after and uses your personal information. It also explains how you can request a copy of your information.

Participation in this survey is entirely voluntary. If at any point you wish to withdraw from the survey, you are free to do so without obligation.

How do I fill out the questionnaire?

Please use the online system wherever possible. If you are unable to use the online system, please send this questionnaire by email to ransomwareconsultation@homeoffice.gov.uk or by post to:

Ransomware Legislative Proposals Consultation Homeland Security Group

Home Office

5th Floor

Peel Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

Most questions can be answered by putting a cross x in the box next to or highlighting the answer that applies to you.

Some questions will ask you to: cross or highlight one box only and some will ask you to: cross or highlight all boxes that apply.

Some questions include a space for you to answer in your own words to provide more detail about a particular subject. This will be indicated by a free text response box.

Some questions may not apply to you, and you will be directed to the next one that does by following an arrow like this: Go to QX

Further information is provided in boxes indicated by (i) symbol which includes additional information about the topic and in some cases instructions on who should answer the questions which follow. Please read these carefully.

Please try to answer every question that applies to you. If you cannot remember or do not know, please cross or highlight the relevant box where shown or leave the question blank.

Throughout the questionnaire, there are references to paragraph numbers. These relate to the paragraphs in ‘Consultation Proposal’ which you can refer back to.

-

Chainalysis. Ransomware Hit $1 Billion in 2023 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

The National Crime Agency describes ransomware as one of the most harmful cyber threats due to the significant financial losses incurred; the threatened theft of intellectual property, sensitive commercial data, or customer Personally Identifiable Information (PII); the disruption of service caused by attacks; and the reputational harm that can result. ↩

-

Information Commissioner’s Office. ‘Data security incident trends’ Information Commissioner’s Office ↩

-

National Crime Agency. Cyber. National Strategic Assessment 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses 2025 ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

MacColl J and others. The Scourge of Ransomware: Victim Insights on Harms to Individuals, Organisations and Society. Royal United Services Institute 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. The experiences and impacts of ransomware attacks on individuals and businesses (2025). ↩

-

Ouellet M and others. ’The network of online stolen data markets: How vendor flows connect digital marketplaces’. The British Journal of Criminology 2022: volume 62, issue 6, pages 1518-1536 ↩

-

Zaeifi M and others. ‘Nothing personal: Understanding the spread and use of Personally Identifiable Information in the Financial Ecosystem‘ 2024: pages 55-65. ↩

-

Ablon, L. ‘Data Thieves: The Motivations of Cyber Threat Actors and Their Use and Monetization of Stolen Data’. RAND 2018 ↩

-

Curran, D. ’Surveillance capitalism and systemic digital risk: The imperative to collect and connect and the risks of interconnectedness’. Big Data & Society 2023: volume 10, issue 1 ↩

-

MacColl J and others. The Scourge of Ransomware: Victim Insights on Harms to Individuals, Organisations and Society. Royal United Services Institute 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘The experiences and impacts of ransomware attacks on individuals and businesses’ (2025). ↩

-

Choi H and others. ‘The role of privacy fatigue in online privacy behaviour’ Computers in Human Behaviour 2018: volume 81, pages 42-51 ↩

-

Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies. ‘Integrated Infrastructure: Cyber Resiliency in Society, Mapping the Consequences of an Interconnected Digital Economy’ Cambridge Centre for Risk Studies University of Cambridge 2016 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

UK logistics firm blames ransomware attack for insolvency, 730 redundancies. The Record 2023 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Travelex falls into administration, with loss of 1,300 jobs The Guardian 2020 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

MacColl J and others. The Scourge of Ransomware: Victim Insights on Harms to Individuals, Organisations and Society. Royal United Services Institute 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

NHS England. Update on cyber incident: Clinical impact in south east London September 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Capita. Update on cyber incident - Capita 2023 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

British Library Cyber Incident Review 2024 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Information Commissioner’s Office. ‘Data security incident trends’ Information Commissioner’s Office. ↩

-

National Crime Agency. National Strategic Assessment 2024 National Crime Agency (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

GOV.UK. ‘Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2024’ 2024 GOV.UK (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Office for National Statistics. Crime in England and Wales. Office for National Statistics. ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. Ransomware, extortion and the cyber crime ecosystem. National Cyber Security Centre. ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. Ransomware, extortion and the cyber crime ecosystem. National Cyber Security Centre. ↩

-

Hernandez-Castro, J and others. ‘An economic analysis of ransomware and its welfare consequences’ The Royal Society Open Science 2020 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

In the UK, there are thirteen national infrastructure sectors: Chemicals, Civil Nuclear, Communications, Defence, Emergency Services, Energy, Finance, Food, Government, Health, Space, Transport and Water ↩

-

GOV.UK ‘CRI joint statement on ransomware payments’ 2023 (viewed 10 January 2025) ↩

-

Brammer Z. ‘Mapping The Ransomware Payment Ecosystem: A comprehensive visualization of the process and participants Institute for Security and Technology. 2022 (viewed on 11 December 2024). Resourcing involves actors reinvesting fundings in new malware, personnel and other tools to further their activity. Obfuscating of funds may involve blending cryptocurrencies of many users together to hide the origins and owners of the funds. ↩

-

Financial Action Task Force. ‘Countering Ransomware Financing’ Financial Action Task Force 2023 (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. ‘Guidance for organisations considering payments in ransomware incidents’ National Cyber Security Centre (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

The NCSC has Certified Information Security Prprofessional (CISP) to facilitate information sharing between organisations, as well as our sector information exchanges (IEs) and other trust groups. Transparency blog - NCSC.GOV.UK ↩

-

GOV.UK. ‘Cyber Security Breaches Survey 2024’ 2024 (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

Cartwright A and others. ‘How cyber insurance influences the ransomware payment decision: theory and evidence’ Geneva papers on risk and insurance-issues and practice 2023: volume 48, issue 2 ↩

-

Meurs T and others. ‘Ransomware: How attacker’s effort, victim characteristics and context influence ransom requested, payment and financial loss’ Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (ecrime) 2022: pages 1-13 ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘The experiences and impacts of ransomware attacks on individuals and businesses’ (2025). ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. ‘A guide to ransomware’ National Cyber Security Centre (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

National Crime Agency ‘Cyber crime’ National Crime Agency (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

Information Commissioner’s Office. ‘Ransomware and data protection compliance’ Information Commissioner’s Office (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

National Crime Agency. ‘International investigation disrupts the world’s most harmful cyber crime group’ National Crime Agency (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

Information Commissioner’s Office. ‘ICO and NCSC stand together against ransomware payments being made’ Information Commissioner’s Office (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘Knowledge and perceptions of the UK public on ransomware against businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘The experiences and impacts of ransomware attacks on individuals and businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

Home Office in collaboration with Ipsos. ‘The experiences and impacts of ransomware attacks on individuals and businesses’ 2025 ↩

-

Yilmaz, Y. ‘Investigating the impact of ransomware splash screens’ Journal of Information Security and Applications 2021 (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. ‘Principles for ransomware-resistant cloud backups’ National Cyber Security Centre (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩

-

National Cyber Security Centre. ‘What is cyber security?’ National Cyber Security Centre (viewed on 11 December 2024) ↩