Prosecuting road traffic offences in Scotland, fixed penalty notice reform: government response to consultation

Updated 8 September 2020

Executive Summary

Throughout the UK, where the police believe that a person has committed certain minor road traffic offences, sections 75 to 77 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 (RTOA) give the police the power to issue a conditional offer of fixed penalty notice (COFPN). This scheme was introduced in 1989 as an alternative to prosecution. Once a COFPN is issued, an individual has 28 days to accept the offer and make payment. If the offer is not accepted or if the recipient fails to take any action, police in Scotland will submit a report to the procurator fiscal for consideration of whether a prosecution should take place.

In England and Wales, in addition to powers to issue COFPNs, the police have powers to issue fixed penalty notices (FPNs) on-the-spot to alleged offenders under section 54 of the RTOA. In the event that the recipient does not either pay the fixed penalty on time or request a hearing in respect of the FPN, a sum equal to one and a half times the FPN amount becomes a registered fine and is collected and enforced in line with the normal procedures in place for court-imposed fines. There is no need for the police to report the matter to the Crown Prosecution Service, nor for a prosecution to take place.

The Scottish Government wishes the law in Scotland to be changed to allow the police to issue on-the-spot FPNs to suspected offenders of road traffic offences committed in Scotland. This is reserved legislation so the UK government is responsible for making any changes. Accordingly, at the Scottish Government’s request, the Department for Transport (DfT) undertook a consultation seeking views on the proposal for FPN reform.

26 responses were received from a range of respondents, including government, public and business. The majority of respondents were in favour with a number of respondents supporting FPN reform on the basis the change would provide a proportionate way to deal with road traffic offences while reducing the need for court proceedings and resulting in more efficient use of resources across the justice system. A factual summary of responses is available. Furthermore, analysis of the likely impacts undertaken by the Scottish Government made clear that this proposed reform would lead to cost and time savings across the public sector while reducing the burden on Scotland’s police, prosecutors and courts.

Having considered the consultation responses and taken account of the detailed costing work, the Scottish Government is satisfied that extending the power to issue FPNs under section 54 RTOA to Scotland would lead to a more proportionate system with cost and time savings for justice partners. Consequently the Scottish Government has decided that it wishes the law in Scotland to be changed to allow the issuing of on-the-spot FPNs to suspected offenders of road traffic offences committed in Scotland. The change would extend to the police in the first instance. Further consideration may then be given to extending the change to traffic wardens and vehicle examiners. The UK government agrees that this would be a sensible reform and will consider the legislative changes required.

Introduction

The consultation on extending section 54 of the RTOA to Scotland was undertaken against the background of the following wider Scottish Government justice aspirations of:

- vision - this proposed reform works towards the vision of a Just, Safe and Resilient Scotland, as outlined in the justice strategy

- priorities - this reform would contribute to ensuring our system and interventions are proportionate, fair and effective, and work towards the following priorities:

- we will modernise civil and criminal law and the justice system to meet the needs of people in Scotland in the 21st Century

- we will work to quickly identify offenders and ensure responses are proportionate, just, effective and promote rehabilitation.

The proposed fixed penalty notice reform will work towards these priorities by introducing greater flexibility in the enforcement of road traffic offences and providing a more proportionate response to offenders.

Background

Some consultees asked why the position has come to be as it is now, whereby enforcement agencies in England and Wales have the power to issue FPNs to offenders on-the-spot but those in Scotland do not. The answer lies in historical changes to the relevant legislation.

When the RTOA was enacted the power in section 54 to issue FPNs on-the-spot extended to England, Wales and Scotland. It enabled a constable in England, Wales and Scotland to issue an on-the-spot fine to alleged road traffic offenders, at the roadside, in circumstances where the driver was in possession of their licence at the time of being stopped.

However, the power to issue a FPN under section 54 to an alleged offender who was not in possession of their driving licence, and was told to go to a police station within 7 days extended only to England and Wales – not to Scotland. This aspect of section 54 in relation to Scotland was never commenced.

Section 75 of the RTOA, as originally enacted, provided for conditional offers of a fixed penalty; it extended only to Scotland, not to England and Wales. It only allowed for conditional offers to be sent by the procurator fiscal.

The UK government identified a number of road safety objectives in the late 1980s and decided to prepare a bill (the Road Traffic Bill) to implement those that required legislative change. The bill dealt with technological advances in road traffic enforcement, namely, fixed cameras to detect speeding and traffic light offences.

In preparing the bill, the government took the view that if the benefits of fixed cameras were to be fully reaped, then it made sense for conditional offers to be available in England and Wales. Accordingly, the government decided to extend section 75 of the RTOA to England and Wales. However, the government took the opportunity presented by the bill also to consider enforcement powers in relation to Scotland.

The substantive proposal in the bill was to extend to the police in Scotland the power to issue conditional offers that had been restricted to the procurator fiscal. The purpose was to enable greater flexibility as the police would be able to issue conditional offers at the site of the offence or remotely from a central office.

Given that the police would, as a result of this change, be able to issue conditional offers to offenders – including at the roadside – the UK Parliament agreed that this change obviated the need for the power in section 54 (on-the-spot fines) to extend to Scotland. Accordingly, the bill amended section 54 to remove its application to Scotland. The Road Traffic Bill became the Road Traffic Act 1991 and meant that the RTOA (i) extended the power to issue conditional offers to the police; and (ii) removed Scotland from the power to issue on-the-spot FPNs.

That explains why the legal position in Scotland is different from the position in England and Wales. In Scotland the power to issue a COFPN is available to the enforcement agencies as an alternative to prosecution. Once a COFPN is issued, an individual has 28 days to accept the offer and make payment. If the offer is not accepted or if the recipient fails to take any action, the police will submit a report (Standard Prosecution Report (SPN)) to the procurator fiscal (Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service) for consideration of whether a prosecution should take place. It should also be noted that, in Scotland, the enforcement agencies have powers available to them to fix FPNs to vehicles under section 62 of the RTOA.

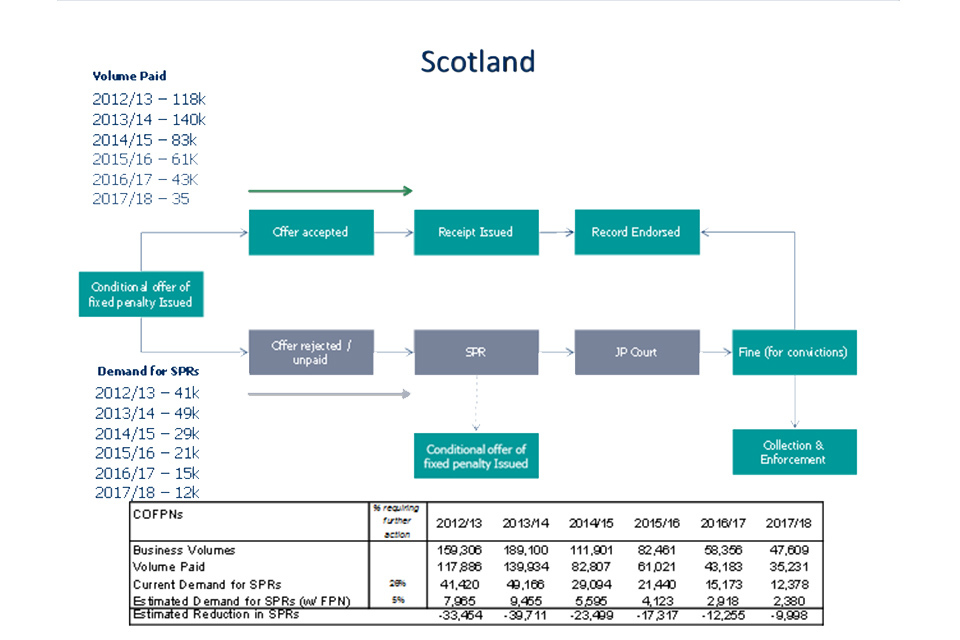

The diagram below sets out the COFPN process and business volumes in Scotland (the latter detailed in both tabular and free text form). With regards to the COFPN process, this is presented through 2 routes available to the member of public following the award of a conditional offer of a Fixed Penalty Notice. The routes are:

- route one outlines 3 clear steps – Step 1 the acceptance of the offer; Step 2, receipt of payment; and then Step 3 an individual’s record being updated

- route two outlines 5 clear steps – Step 1 follows the offer being rejected and/or unpaid; Step 2 leads to an escalation to creation and submission of a standard prosecution report (SPR) to COPFS; Step 3 will then see the COPFS consider whether to issue a further conditional offer or take the matter to court; Step 4 leads to the court determination and, if convicted, a fine. Step 5 follows through to collection and enforcement

COFPN process diagram plus Scotland volume figures. The process is detailedin the proceeding text of the consultation document.

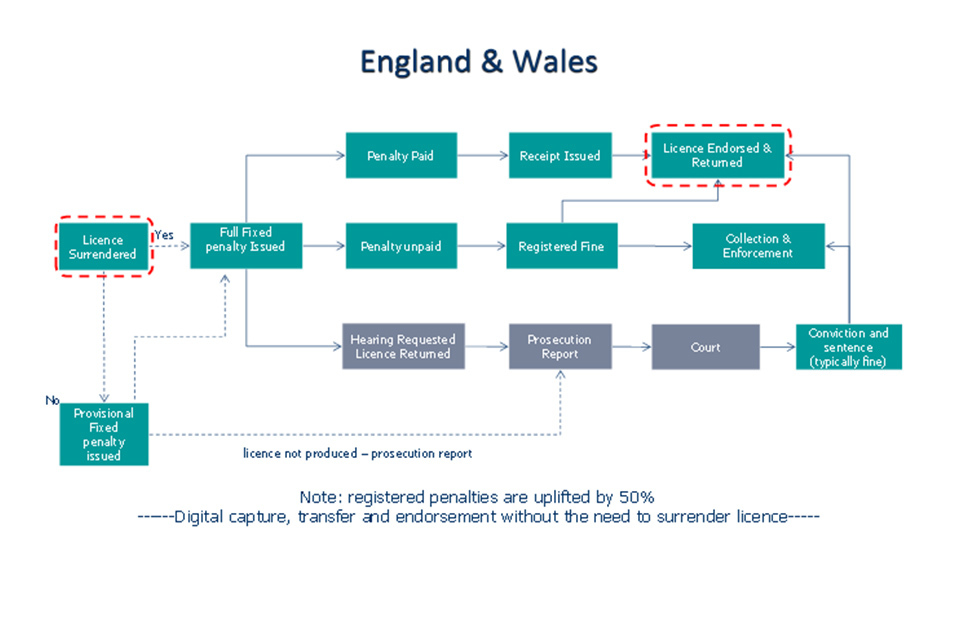

In England and Wales, section 54 of the RTOA provides police officers with the option to issue FPNs in respect of certain low-level road traffic offences. There is a crucial distinction between the way in which failure to respond to a FPN is dealt with as opposed to failure to address a COFPN.

In the event that the recipient does not either pay the fixed penalty on time or request a hearing in respect of the FPN, a sum equal to one and a half times the FPN amount becomes a registered fine and is collected and enforced in line with the normal procedures in place for court-imposed fines. There is no need, in those circumstances, for the police to report the matter to the Crown Prosecution Service, nor for a prosecution to take place.

The diagram below shows the FPN process in England and Wales:

The diagram below details the process in England and Wales when a full fixed penalty has been issued, and the 3 potential subsequent scenarios. The scenarios are:

- Scenario 1 details the next steps within an uncontested position where the penalty is paid in full, a receipt issued to acknowledge payment and finally the licence is endorsed and returned to the individual

- Scenario 2 details the next step of the position where the fine has been accepted but there is a failure to pay, resulting in the fine being registered with the court, where it will increase by 50%. The court will then enforce the new fine. Following the collection and payment of the fine, the licence is endorsed and returned to the individual

- Scenario 3 details the position where the individual wishes to contest. That leads to a hearing being requested, the development of a prosecution report before potential progression to Court. If the case reaches the Court stage and that concludes a determination of conviction and sentence confirming the original fine, the final steps will be the enforcement and collection of the fine, with the licence then endorsed and returned to the individual

Diagram detailing the process in England and Wales when a full fixed penalty has been issued, and the three potential subsequent scenarios as detailed in the text.

The proposal

Rationale for intervention

In Scotland, the existing position is a problem because it uses limited justice resources on unnecessary justice processes that could be handled more effectively and proportionately.

Section 54 RTOA only applies in England and Wales and criminal justice organisations in Scotland are keen that it should also apply in Scotland, as it provides a more flexible, efficient and effective method for dealing with minor road traffic offending.

As set out above, the ability to issue FPNs in addition to COFPNs should reduce the number of COFPNs issued. This would in turn lead to Police Scotland reporting fewer unpaid COFPNs to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, which would in turn lead to fewer complaints being registered at Justice of the Peace courts. The key benefit of this should be to reduce bureaucracy and enhance the capability of Police Scotland, the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and the Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service (SCTS) to carry out other work. It is important to note that the right of the recipient to challenge the FPN should s/he wish to do so would be preserved.

As well as saving resources for these organisations, FPN reform would increase the resilience of the justice system and provide a more proportionate response to dealing with road traffic offences.

The power to issue FPNs in Scotland will not replace COFPNs; instead they would supplement each other. FPN reform would provide greater flexibility to enforcers in Scotland to use the most appropriate option in any given circumstance.

For example, if a police officer stops a driver in person, it may be more appropriate to issue an FPN, whereas COFPNs may be more appropriate for remote enforcement e.g. speed cameras. In England and Wales, where both FPNs and COFPNs are currently available, an increased reliance on enforcement cameras has led to greater use of COFPNs.

Consultation

Between 27 March 2018 and 8 May 2018, the Department for Transport (DfT) held a consultation exercise, at the Scottish Government’s request, regarding provisions to bring the Scottish regime in line with England and Wales.

The consultation was published on GOV.UK and brought to the attention of relevant justice and transport stakeholders. The consultation asked for feedback on the proposal to amend section 54 of the Road Traffic Offenders Act 1988 so that it applied to Scotland.

26 responses were received from a range of respondents, including government, public and business. The majority of respondents were in favour with a number of respondents supporting FPN reform on the basis the change would provide a proportionate way to deal with road traffic offences while reducing the need for court proceedings and resulting in more efficient use of resources across the justice system. A minority (mostly from individual Justices of the Peace) were opposed to the proposed policy change. The main concerns conveyed by consultees are dealt with below.

A factual summary of consultation responses was published in November 2018 and is available.

In addition to the written consultation document, Scottish Government Justice officials ran a workshop on 21 August 2018 with Police Scotland, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, SCTS and Justice Analytical Services (JAS) to share data, discuss implementation, and discuss issues raised in the consultation.

When the government published the factual summary of the consultation responses, it included the following commitments by the Scottish Government which have now all been carried out. These were to:

- carefully consider, through engagement with justice and transport stakeholders, issues (within the scope of the consultation) raised by respondents

- produce a Scottish Government: impact assessment

- engage with the Department for Transport and the Office of the Secretary Of State for Scotland to reach a decision on the way forward and agree a final response to the consultation.

The main issues raised during the consultation were:

- the Scottish Government: impact assessment – some respondents called for an impact assessment considering the projected effects in more detail. Consequently, in the factual summary of consultation responses, the Scottish Government gave an undertaking to assess potential costs and savings of FPN reform. This detailed costing work can be seen in the technical annex

- resources – concerns were raised that there could be a rise in unpaid fines and a large increase in the workloads on the Fines Courts and Fines Enforcement staff. Although FPN reform may lead to an increase in numbers of fines for SCTS’s Fine Enforcement Officers to collect, since SCTS retain 33% of fines, any increase in collection work should be self-funding

- furthermore, FPN reform should not in itself lead to any significant increase in the volume of fines enquiry court hearings and subsequent warrants. Also, the 50% statutory uplift for failing to pay within the offer period is likely to encourage compliance.

- implementation – a range of matters associated with implementation were raised such as the importance of guidance and updating IT systems. These have been given early consideration and would be developed in more detail prior to any legislation being commenced. A number of respondents raised concerns about extending provisions to traffic wardens and vehicle examiners, so any such extension would require further consideration

- Court process – concerns were expressed about the importance of court attendance as a deterrent, the potential for non-court disposals to trivialise criminal offences, and the importance of ensuring there is a robust appeals process within an appropriate timescale. However, the proposed reforms would still have court proceedings for those who wish to challenge their FPN and penalty points arguably constitute a similar level of deterrent

Likely impacts

Benefits

The analysis in the attached technical annex suggests that, based on current levels of standard prosecution reports (SPRs) and reasonable assumptions, that with relatively minor initial outlay, savings are likely to range from £0.7 million to £3 million. These savings could be substantially affected by trends in offending or policy changes. For example, if SPRs rise substantially, back to their 2014 to 2015 levels potential savings may range from £1.4 million to £5.7 million.

The majority of these would be notional savings which would be unlikely to be realised in financial terms. However, the time savings that these figures represent would enable partners to spend substantially more time on other tasks such as preventing offending, dedicating resources to more serious crimes and improving the justice system for victims and witnesses. They would provide the justice system with greater resilience to deal with fluctuations in demand caused by seasonal campaigns or by changes in policy and priorities.

Although it is not possible to quantify, there should also be additional savings for Police Scotland associated with decreasing the numbers of court appearances, as well as the reduced overtime payments and administrative work associated with these.

Furthermore, FPN reform would lead to swifter, more proportionate resolution that would prevent large numbers of people receiving a conviction for relatively minor road traffic offences.

Costs

Engagement with justice partners made clear that there would be some minor costs associated with implementation of FPNs and associated training and IT. However there is no outcome projected which does not include substantial, annually recurring savings to justice partners. If FPN reform is taken forward, it will be closely monitored and evaluated, so if the savings are at the lower end of predictions, further action would be considered to ensure that potential savings are realised, where appropriate.

Impacts of the regulatory changes are estimated to be low and the costs to business do not warrant a full UK government impact assessment. The detailed costing work developed after the workshop can be seen in the technical annex.

Discussion

Both the consultation plus the costs and benefits modelling work make clear that there is a compelling case for FPN reform. The majority of responses to the consultation were in favour of this reform and substantive issues raised such as the need for impact assessment and to be implemented effectively, have been addressed or will be part of consideration in the next steps of the policy development process.

This engagement process has established that the policy intervention would lead to cost and time savings across the public sector while reducing the burden on Scotland’s police, prosecutors and courts. This fits in with the Scottish Government’s long-standing commitment to enhance the efficiency of the criminal justice system, as set out in Justice in Scotland – Vision and Priorities, while continuing to ensure that someone accused of a crime should be treated fairly. The principle of non-court alternatives to prosecution, used appropriately, is already well-established in Scotland as a part of a fair and efficient system.

Conclusion

Having considered the consultation responses and taken account of feedback from the workshop and the detailed costing work, the Scottish Government is satisfied that FPN reform would lead to a more proportionate system with cost and time savings for justice partners.

Consequently the Scottish Government wishes the law in Scotland to be changed to allow the police to issue on-the-spot fixed penalty notices to suspected offenders of road traffic offences committed in Scotland. Given that the vast majority of road traffic enforcement is undertaken by the police, (rather than by traffic wardens or vehicle examiners) and the cost analysis undertaken as part of this consultation exercise relates to the police, the powers would, in the first instance, extend solely to the police. Subsequent consideration may be given to the role of traffic wardens and vehicle examiners to assess whether they should also have this power.

The UK government is content for this reform to proceed and will consider a suitable legislative opportunity.

Next Steps

The Scottish Government and the UK government will consider the way forward and as this is a reserved matter, the UK government will consider legislative changes required.

Annex

Fixed penalty notice reform – technical annex: options appraisal

As previously set out, Scottish Government Justice officials ran a workshop on 21 August 2018 with Police Scotland, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service , SCTS and Justice Analytical Services (JAS) to share data, discuss implementation, and discuss issues raised in the consultation. The purpose of this Annex is to set out some of the technical matters considered in more detail.

Options considered

Two options have been considered.

Option 1:

- retain the current system – will mean continuing to use valuable and limited justice partner resources in a range of procedures such as issuing and processing SPRs, and processing high volumes of cases where there may be more proportionate ways to issue penalties for low level offending. As well as the costs associated with these, this option will require substantial input of time from police officers, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, SCTS and so on.

Option 2:

- fixed penalty notice reform - the following sets out the impact of FPN reform on a range of Justice partners, including SCTS, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and Police Scotland. In addition to justice partners, the reform would have an important impact on witnesses who would no longer have to attend court to provide evidence related to these offences and those who have offended who would face a swifter, more proportionate sanction for their offence.

Scottish Government Justice officials ran a workshop on 21 August 2018 with Police Scotland, Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, SCTS and Justice Analytical Services (JAS) to collectively identify issues that should be addressed in such a Scottish Government impact assessment, share data, discuss implementation and consider the full government response to the consultation that will be published in the coming months. This Scottish Government impact assessment is based on these deliberations as well as management information data and further engagement with partners over subsequent weeks.

Impact of FPN reform: justice partners

| COFPNs | % requiring further action | 2012/13 | 2013/14 | 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | 2017/18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business Volumes | 159,306 | 189,100 | 111,901 | 82,461 | 58,356 | 47,609 | |

| Current demand for SPRs from unpaid COFPNs | 26% | 41,420 | 49,166 | 29,094 | 21,440 | 15,173 | 12,378 |

| Estimated demand for SPRs (with FPN reform) | 5% | 7,965 | 9,455 | 5,595 | 4,123 | 2,918 | 2,380 |

| Estimated reduction in SPRs | -33,454 | -39,711 | -23,499 | -17,317 | -12,255 | -9,998 |

Since 2013 to 2014, there has been a steady decline in business volumes for COFPNs. This decline is due to a combination of factors including a move to a more outcome-focused approach and more proportionate response to low level offending as well as a more general decrease in crime across society. Despite this, there were 47,609 COFPNs issued in 2017/18 and 26% (12,378) of these required SPR to be submitted to procurators fiscal[footnote 1].

Under the current model approx. 26% of business volumes require SPRs to be issued. With FPN reform the model assumes this will reduce to approx. 5% (2,380) as, based on similar direct measures such as the anti-social behaviour FPN, there is likely to be approximately 5% who either wish to challenge their notice or do not produce their licence to the police (which could lead to an SPR being issued).

Based on these assumptions, using 2017 to 2018 data, FPN reform could potentially reduce the number of SPRs the police submit and Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service have to consider, by approx 9,998 per year.

Figures published by Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service suggest that the vast majority of SPRs are marked for further action, including court proceedings. For example, in the year 2017/18 88% of SPRs were marked by prosecutors for further action. If this figure is applied to the 2017/18 data, then approx. 8,800 fewer cases will be marked for further action.

Some SPRs will be marked for a second direct measure from Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service, and a proportion will pay their fine after this second notice, so they will not all progress to complaints registered at JP courts. If an SPR results from failure to pay a COFPN then it is more likely to be routed to a higher prosecution forum such as the JP court over a fiscal direct measure although there is no data on how many SPRs are resolved through this route.

If FPN reform is taken forward, there is some uncertainty over both:

a) the proportion of COFPN-eligible offences which would in practice be given an FPN

and

b) the proportion of FPNs for endorsable and non-endorsable offences that would result in payment, registered fine or court action in Scotland

Although justice partners are confident that the majority of COFPNs could be changed to FPNs in the new regime, if COFPNs continue to be used in place of FPNs for some offences, or if the rates of payment or registered fines are much lower than anticipated, it is possible that the reduction in court volumes could be lower than presented, with associated reductions in cost savings.

Scottish Government analysts have interrogated separate statistics on payment rates for FPNs and COFPNs in England and Wales, however these are difficult to use with confidence for comparison purposes, due to differences in practice and terminology. One source from 2013 cites payment rates for endorsable offences subject to FPNs in E&W between 2000 and 2013 as 97% (considerably higher than current payment rates for endorsable COFPNs in Scotland), while other statistics suggest that payment rates are considerably lower than this, with trends of increasing court action in recent years. Furthermore, comparability is difficult as it is unclear whether these sources refer exclusively to FPNs, as opposed to FPNs and COFPNs in combination. There are a range of further comparability issues, including the existence of other outcomes in England and Wales, such as driver retraining courses.

Despite this uncertainty we are confident that there is no outcome projected which does not include substantial, annually recurring savings to justice partners. If FPN reform is taken forward, it will be closely monitored and evaluated, so if the savings are at the lower end of predictions, further action would be considered to ensure that potential savings are realised, where appropriate.

A range of potential savings has been provided in the below tables. They set out 4 potential levels of SPR reduction – 5,000, 10,000, 15,000 and 20,000, so that there are robust figures whether the decline in SPRs continues or if the trend reverses.

The 3 tables below set out savings models for justice partners based on three different assumptions. In these models the police costs are constant but the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and SCTS costs vary as follows:

- the cost of a fixed penalty case at a JP court equates to 10% of the average sheriff/JP court case for Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and 10% of the average sheriff/JP court case pleading guilty at 1st calling for SCTS

- the cost of a fixed penalty case at a JP court equates to 25% of the average sheriff/JP court case for Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and 25% of the average sheriff/JP court case pleading guilty at 1st calling for SCTS

- the cost of a fixed penalty case at a JP court equates to 50% of the average sheriff/JP court case for Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and 50% of the average sheriff/JP court case pleading guilty at 1st calling for SCTS[footnote 2]

These are small percentages as the vast majority of SPRs will not require evidence to be led so the costing is primarily for case marking, letter pleas etc. However, some proportion will progress to intermediate diets and evidence-led trials with witnesses in attendance, in which case costs will drastically escalate.

Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service and SCTS do not have data to indicate which of these assumptions is most accurate, so this Scottish Government impact assessment contains the full range to ensure all possibilities receive due consideration.

Table 1 – 10% assumption

| Section 54 - potential savings (Note - for illustrative purposes only) | Average costs per case | % costs applied to RTA FPN Offences | Average costs for RTA FPN case | % receiving legal assistance | Volume of cases redirected by section 54: 5,000 (96 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by section 54: 10,000 (192 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by section 54: 15,000 (385 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by section 54: 20,000 (577 per week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Potential Police Savings (SPRs) | £18.13[footnote 3] | £12.50 | £62,500 | £125,000 | £187,500 | £250,000 | ||

| Potential Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service Savings | £444[footnote 4] | 10% | £44 | £222,000 | £444,000 | £666,000 | £888,000 | |

| Potential SCTS Savings | £101[footnote 5] | 10% | £10 | £50,500 | £101,000 | £151,500 | £202,000 | |

| Total Potential Savings | £335,000 | £670,000 | £1,005,000 | £1,340,000 |

Table 2 – 25% assumption

| Section 54 - Potential Savings (Note - for illustrative purposes only) | Average Costs Per Case | % Costs Applied to RTA FPN Offences | Average Costs for RTA FPN Case | % receiving Legal Assistance | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 5,000 (96 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 10,000 (192 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 15,000 (288 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 20,000 (385 per week) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Potential Police Savings (SPRs) | £18.13[footnote 3] | £12.50 | £62,500 | £125,000 | £187,500 | £250,000 | ||

| Potential Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Savings | £444[footnote 4] | 25% | £111 | £555,000 | £1,110,000 | £1,665,000 | £2,220,000 | |

| Potential SCTS Savings | £101[footnote 5] | 25% | £25 | £126,250 | £252,500 | £378,750 | £505,000 | |

| Total Potential Savings | £743,750 | £1,487,500 | £2,231,250 | £2,975,000 |

Table 3 – 50% assumption

| Section 54 - Potential Savings (Note - for illustrative purposes only) | Average Costs Per Case % Costs Applied to RTA FPN Offences | Average Costs for RTA FPN Case | % receiving Legal Assistance | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 5,000 (96 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 10,000 (192 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 15,000 (288 per week) | Volume of cases redirected by Section 54: 20,000 (385 per week) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Potential Police Savings (SPRs) | £18.13[footnote 3] | £12.50 | £62,500 | £125,000 | £187,500 | £250,000 | ||

| Potential Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service Savings | £444[footnote 4] | 50% | £222 | £1,110,000 | £2,220,000 | £3,330,000 | £4,440,000 | |

| Potential SCTS Savings | £101[footnote 5] | 50% | £51 | £252,500 | £505,000 | £757,500 | £1,010,000 | |

| Total Potential Savings | £1,425,000 | £2,850,000 | £4,275,000 | £5,700,000 |

Police Scotland

Further potential savings

In addition to the above, further notional savings would be derived from fewer numbers of court appearances for officers meaning they spend more time in communities, reduced overtime payments and disrupted rest days, as well as less administrative work associated with citations and countermands.

In 2016 to 2017 25,350 police witness citations were issued, although in the vast majority of cases, officers would not be required to give evidence.

Further potential costs

Introduction of FPNs would need to be closely monitored to see if it leads to an increase in low value warrants, however it is possible that the cohort subject to these would be unchanged in the new system. This would also be impacted by other ongoing work in relation to fines enforcement.

Police Scotland would require to implement a new ICT system to manage tickets to provide a national function. It may also increase demand within the central ticket office function which could have resourcing implications. In addition to this, there would be an initial outlay in both capital funding and resourcing costs associated with the development of training materials and the updates to fixed penalty notices.

Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service

Further potential costs

Guidance will need to be produced however this cost should be absorbed into Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service’s budgets and should not require additional resources.

Scottish Courts and Tribunals Service

Further potential costs

In 2017 to 2018, SCTS collected £3.9 million from COFPNs. SCTS retained £391,000 (10% retention rate) as part of overall funding arrangements agreed with the Scottish Government with the balance remitted by Scottish Ministers to UK Treasury (note: the retention rate for registered fines is 33%). From 2018 to 2019 onwards the balance of funds collected will go to the Scottish Consolidated fund.

Although FPN reform may lead to an increase in numbers of fines for SCTS’s Fine Enforcement Officers to collect, since SCTS retain 33% of fines income, any increase in collection work should be self-funding.

As outlined, FPN reform should not in itself lead to any significant increase in the volume of fines enquiry court hearings and subsequent warrants. Additionally, the 50% statutory uplift for failing to pay within the offer period is more likely to encourage compliance.

The success to strengthening the administrative enforcement process and minimising judicial and police involvement in the fines process is improved access to data which SCTS are actively pursuing as well as progressing other legislative changes.

FPN reform would require updating IT systems. This is likely to require an initial outlay of around £25,000 to 30,000.

Justice of the Peace Courts

| 2014/15 | 2015/16 | 2016/17 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complaints Registered | 66,819 | 54,856 | 41,402 |

| Trials (Evidence Led) | 3,151 | 3,258 | 2,810 |

The level of complaints registered in the Justice of the Peace Court has declined substantially in recent years, reflecting both a decrease in recorded crime levels and decisions taken by police and prosecutors to resolve lower level offences through the issuing of fixed penalty notices or fiscal fines. The vast majority of these complaints registered do not reach an evidence-led trial. If FPN reform is taken forward potentially up to 8,800 fewer complaints would be registered at JP courts.

Impact of FPN reform on legal aid

The Scottish Legal Aid Board have confirmed that FPN reform is likely to have a negligible effect on legal aid expenditure. The new offences that could be subject to FPN are all low level JP court and very unlikely to meet the statutory merits test, therefore they would not be legally aided.

Scottish firms impact test

Justice partners do not predict that FPN reform will have significant impact on businesses in Scotland and no issues were raised within the consultation. It is possible that a reduction in legal procedures associated with unpaid COFPNs could lead to a decline in independent legal advice. We do not have data on this, however justice partners advised that the majority of cases would be unrepresented so this is likely to be a small effect. It was not raised as a concern in the consultation response from the Law Society.

The motoring organisations who responded to the consultation were in favour of FPN reform, stating that it would help eliminate the confusion caused by two separate legal frameworks and significantly improve the experience for the motorists.

No business interests raised any concerns in the consultation. This is as anticipated since any motoring businesses who could be disproportionately affected by a new policy response to motoring offences, will have noted the reduction in the likelihood of court appearances and accompanying legal costs. Also, the recipient has the right to challenge the FPN should s/he wish to do so.

Competition assessment

It is not anticipated that FPN reform will have an impact on competition within Scotland. The proposals do not create a competitive advantage for any particular sector or individual; they offer benefits across the whole justice sector.

Enforcement, sanctions and monitoring

If taken forward, the effect of FPN reform would be monitored by Scottish Government and Justice Partners for their individual interests as well as the Justice Board who take a strategic overview of the impact of justice policies and their interactions amongst justice partners.

Partners will be mindful of the impact that FPN reform could have on freeing up resources that could be used more effectively elsewhere to meet justice outcomes. They will also be conscious of the impact this reform could have on behaviours, for example leading to greater use of FPNs. To do this, should not require the collection of specific new data as they should be available through existing management information structures.

Summary and Recommendation

The figures contained in this technical annex are conservative due to the lack of precise data on some areas of cost savings. The current analysis suggests based on current levels of SPRs and reasonable assumptions that with relatively minor initial outlay, savings are likely to range from £0.7 million to £3 million.

These savings could be substantially affected by trends in offending or policy changes. For example, if SPRs rise substantially, back to their 2014 to 2015 levels potential savings may range from £1.4 million to £5.7 million.

The majority of these would be notional savings which would be unlikely to be realised in financial terms. However, the time savings that these figures represent would enable partners to spend substantially more time on other tasks such as preventing offending, dedicating resources to more serious crimes and improving the justice system for victims and witnesses. They would provide the justice system with greater resilience to deal with fluctuations in demand caused by seasonal campaigns or by changes in policy and priorities.

Although it is not possible to quantify, there should also be additional savings for Police Scotland associated with decreasing the numbers of court appearances, as well as the reduced overtime payments and administrative work associated with these.

Furthermore, FPN reform would lead to swifter, more proportionate resolution that would prevent large numbers of people receiving a conviction for relatively minor road traffic offences.

Overall, the cost and benefit analysis is clear that FPN reform would reduce the burden on Scotland’s police, prosecutors and courts while ensuring that those accused of a crime should be treated fairly. This fits in with the Scottish Government’s long-standing commitment to enhance the efficiency of the criminal justice system, as set out in Justice in Scotland – Vision and Priorities.

Footnotes

-

A small number of SPRs are also reported each year from DVSA – there were 110 SPRs in 2017/18 ↩

-

Ideally both figures would be for pleading guilty at first calling but data is not available at this stage for all justice partners ↩

-

Average cost of simple SPR £18.13 recent Audit Scotland Report (lower cost of £12.50 used assumes abbreviated report used) ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Average cost of prosecution in sheriff/jp court is £444. The vast majority of SPRs for section 54 offences will not require evidence to be led and will only require case marking from Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Average cost of a case pleading guilty at 1st calling (these cases are at the lower end and more likely to be letter pleas and so on) ↩ ↩2 ↩3