Government response (accessible version)

Updated 18 August 2021

Outline and contact details

This document is the post-consultation report for the consultation paper, “Consultation on a new legal duty to support a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence”.

It will cover:

- introduction: Government approach

- the background to the consultation

- a summary of the consultation responses

- the next steps following this consultation

- a detailed response to the specific questions raised in the consultation

Further copies of this report and the consultation paper can be obtained by contacting the Serious Violence Unit at the address below:

Serious Violence Unit

Home Office

5th Floor, Fry Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

Telephone: 0207 035 8303

Email: SVLegalDutyConsultation@homeoffice.gov.uk

This report is also available on GOV.UK.

Alternative format versions of this publication can be requested from:

SVLegalDutyConsultation@homeoffice.gov.uk

Complaints or comments

If you have any complaints or comments about the consultation process you should contact the Home Office at the above address.

Introduction: Government Approach

-

The Government’s Serious Violence Strategy is clear that tackling serious violence is not only a law enforcement issue, it needs a multi-agency approach involving a range of partners and agencies such as education, health, social services, housing, youth and victim services with a focus on prevention and early intervention. Action should be guided by evidence of the problems and what works in tackling the root causes of violence. To do this, we must bring organisations together to share information, data and intelligence and encourage them to work in concert rather than in isolation.

-

The proposed new duty is a key building block of the Government’s public health approach to preventing and tackling serious violence. We are also investing £100m extra funding in 2019/20 to support increased police activity to tackle knife crime. This includes the provisional allocation of £35m funding for the introduction of Violence Reduction Units in the 18 force areas most affected by serious violence. The proposed duty will complement and assist the Violence Reduction Units in their aim of preventing and tackling serious violence, by providing a strategic platform with the right regulatory conditions to support successful delivery of this multi-agency approach, including through the extended set of partners on whom the duty will fall.

-

Other building blocks to the approach include the £200m investment over ten years for the Youth Endowment Fund, which will focus on targeted early intervention with those children and young people most vulnerable to involvement in serious violence; and the establishment of the cross party, cross sector, Serious Violence Taskforce which is chaired by the Home Secretary, to provide additional oversight and external challenge of this critical work.

-

This all builds on the Government’s Serious Violence Strategy which was published in April 2018. In particular, it builds on the analysis of the drivers and risk factors for serious violence set out in the Strategy, as well as the Strategy’s commitments such as the investment of £22m in the Early Intervention Youth Fund which is supporting 40 projects in England and Wales; and the introduction of the National County Lines Coordination Centre which has already co-ordinated three separate weeks of intensive law enforcement action resulting in more than 1600 arrests, over 2100 individuals engaged for safeguarding, and significant seizures of weapons and drugs.

-

Noting the opportunities and challenges that have been described in response to the options in the consultation, the Government intends to bring forward primary legislation, when parliamentary time allows, to create a new duty on relevant agencies and organisations to collaborate, where possible through existing partnership structures, to prevent and reduce serious violence. In doing so, the Government will create the conditions for flexibility in local areas to allow agencies and bodies to determine how best to work together to address local need. The Government also recognises the important role of Community Safety Partnerships in this context, so we Consultation on a new legal duty to support a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence will amend the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to ensure that serious violence is an explicit priority for Community Safety Partnerships.

-

The geographical scope of the proposed new duty is England and Wales, mirroring that of the Serious Violence Strategy. The Welsh Government supports this approach which recognises the importance of creating flexibility for local areas and the intention to complement the existing mechanisms that are already in place to tackle serious violence, and the different legislative and partnership landscape in Wales.

Background

7. The consultation on a new legal duty to support a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence was published on 1 April 2019. It invited comments on three options for achieving an effective multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence.

8. The three proposals set out in the consultation document were:

- Option one: a new duty on specific organisations to have due regard to the prevention and tackling of serious violence. This was the Government’s preferred option and would be achieved by introducing primary legislation to place a new duty on specific organisations to have due regard to the prevention and tackling of serious violence. The list of specific organisations would include local authorities, senior figures in criminal justice institutions, education, child care institutions, health and social care bodies and the police. It would not necessitate a specific multi-agency setting but would act to encourage and improve partnership working and information sharing.

- Option two: a new duty through legislation to revise Community Safety Partnerships. This could be achieved through legislating to amend Community Safety Partnerships to ensure they have a strategy for preventing and tackling serious violence. This option would directly commit organisations to become members of a partnership (in this case, the Community Safety Partnership) rather than requiring organisations to have “due regard” to preventing and tackling serious violence.

- Option three: a voluntary non-legislative approach. This approach would encourage areas to adopt voluntary measures to engage in a multi-agency approach instead of, or to complement, introducing a new statutory duty. This would mean a range of organisations would recognise they have an important role to play in preventing and tackling serious violence. The Government would support communities and local partnerships by facilitating the sharing of best practice across geographical boundaries and providing guidance where appropriate.

9. The consultation closed on 28 May 2019 and this report summarises the responses, including how the consultation process influenced the development of the policy consulted upon.

Summary and next steps

10. We have reviewed all responses received to the consultation, through the online questionnaire, postal and email submissions, a breakdown of the results, and findings from these have been set out in this consultation response document at Annex A. The responses indicated that there is clear support for the Government’s description of an effective multi-agency ‘public health’ approach to preventing and tackling serious violence, however there was no clear consensus about which of the three options listed in the paper would best achieve this approach.

11. As set out in the introduction, the Government intends to bring forward primary legislation to create a new duty on organisations to collaborate, where possible through existing partnership structures, to prevent and reduce serious violence, and in recognition of the important role of Community Safety Partnerships in this context, we also intend to amend the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 to ensure that serious violence is an explicit priority for Community Safety Partnerships.

Option One: New duty on specific organisations to have due regard to the prevention and tackling of serious violence

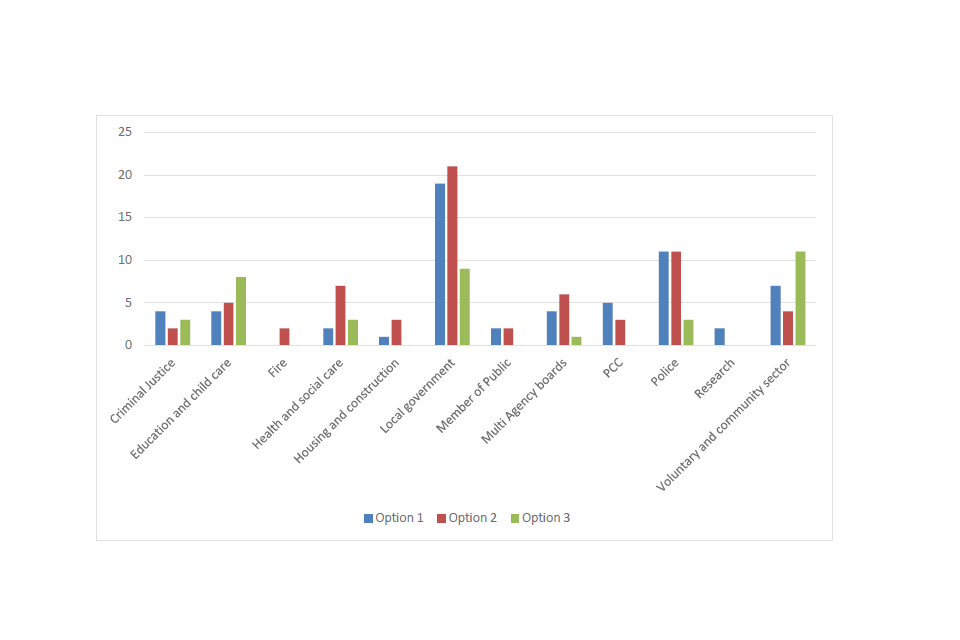

12. 37% of responses supported option one[footnote 1]. Of respondents who provided information about their professional sector and favoured one of the three options, option one was the preferred option for the criminal justice sector, police and crime commissioners and the research sector. The police sector and members of the public supported equally options one and two.

13. Although some partnerships work well in tackling serious violence, in others there are gaps in performance in terms of competing priorities, strength of partnership, and/or a lack or absence of important elements such as data sharing and intelligence. Successfully dealing with this issue means ensuring that all relevant agencies are focussed on and accountable for preventing and reducing serious violence and a new duty is an important means of achieving this. This option has the advantage in that it places a new duty on specific organisations or authorities but leaves it to them to decide how best to comply. It therefore provides flexibility, but the logic of such a duty should mean that the relevant organisations will engage and work together in the most effective local partnership in that area.

14. We are clear that there is a need for a multi-agency approach involving partners and agencies. Primary legislation will place a statutory duty on specific organisations or authorities to ensure they are focussed on and accountable for preventing and reducing serious violence. We want to galvanise the partnerships that are not as effective at preventing and reducing serious violence currently by encouraging them to share data, intelligence and knowledge to generate evidence-based analysis of the problem and solutions.

15. Such a duty would create the conditions for relevant agencies and partners to collaborate and communicate regularly, to use existing partnerships and to share information and take effective coordinated action in their local areas. Ultimately, we want to reduce serious violence across England and Wales, ensuring that everyone can expect an effective collaboration and prioritisation wherever they live.

16. Along with increasing the consistency in terms of the prioritisation and accountability in organisations for preventing and reducing serious violence, respondents to the consultation also highlighted that option one would allow for local flexibility in deciding how to implement.

17. However, as with options two and three, option one did not have a majority of support from respondents to the consultation and we have considered the reasons given for this. As set out in Annex A, the majority were around the belief that existing duties and legislation are sufficient or suggesting funding and time pressures, however, the marked rise we have seen in serious violence since 2014 suggests that more needs to be done.

18. There were also respondents to the consultation who raised concerns that any duty would be placed on individual professionals. The intention has always been to introduce primary legislation that would place a duty on specific organisations, rather than on individual professionals to have due regard to the prevention and tackling of serious violence. However, we do understand the concerns raised where respondents to the consultation have understood option one to be similar to activities under the “Prevent duty”, set out in the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015, which includes guidance detailing a range of activity for staff such as to undertake training to identify children at risk of being drawn into terrorism, and to challenge extremist ideas. In addition, some respondents raised concerns around the language proposed in option one, specifically having “due regard” being too vague or lacking clarity.

19. In considering these responses, we have re-visited how this new primary legislation will be framed and we have decided not to introduce legislation to “have due regard”, instead we will legislate to ensure that specific organisations or authorities have a duty to collaborate and plan to prevent and reduce serious violence. This change will ensure that the duty is the responsibility of agencies and bodies rather than individual professionals and to provide the necessary clarity around what is expected, while still enabling those organisations the freedom to decide how to best discharge this duty in their local area.

20. We have heard through the consultation responses that the duty should be flexible enough to take account of the problem profile in local areas. Therefore, we propose that it will be open to the local area to set its own reasonable definition of serious violence for the purpose of defining the scope of its activities. We expect that this definition should encompass serious violence as defined for the purposes of the Government’s Serious Violence Strategy and include a focus on issues such as public space violent crime at its core.

21. The consultation asked if the list of specified agencies set out in Schedule 6 of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 are the right organisations to work to tackle and prevent serious violence, with 62% of online respondents agreeing[footnote 2]. However, 107 respondents made suggestions for potential additional partners. The most commonly raised suggestions for additional partners to those already included in Schedule 6 were for the voluntary, community and faith sector, clinical commissioning groups and the fire and rescue service to be included.

22. While we have considered these suggestions, we do not feel that it is appropriate to extend the duty to the voluntary sector, instead we intend to provide guidance and support to local areas to ensure that the voluntary, community and faith sectors are engaged in activity effectively, to allow for flexibility at a local level to include the most relevant organisations to tackle and prevent serious violence.

23. The Government will give further consideration to the representations made during the consultation about suitable organisations and authorities who should be subject to the new duty. We will work across government and carry out further informal targeted consultation with relevant organisations and bodies following the Government response, to finalise the list of specific organisations or authorities.

Option Two: New duty through legislating to revise Community Safety Partnerships

24. 40% of online respondents supported option two[footnote 3]. Of respondents who provided information about their professional sector and favoured one of the three options, option two was favoured by fire and rescue services, health and social care, local government, housing and construction sectors and multi-agency boards. The police sector and members of the public supported equally options one and two.

25. This option differs from option one as it directly commits organisations to become members of a Community Safety Partnership rather than placing a duty on specified organisations to preventing and tackling serious violence. This has the benefit of the clarity of legislating for Community Safety Partnerships becoming the lead partnership in fulfilling this key mission against serious violence.

26. We recognise that Community Safety Partnerships are stronger in some areas than others, and this variation may initially impact on the effectiveness of some Community Safety Partnerships in tackling violent crime, with a number of respondents raising this concern. In addition, the geographical reach of Community Safety Partnerships might mean they are not the optimum partnership model in all areas. However, a number of respondents[footnote 4] did raise the positive work underway within their area.

The Community Safety Partnerships are well established with extensive cross-fertilised networks and embedded working practices across the field of community safety, criminal justice, health, safeguarding and the third sector. There has been around 20 years accumulated knowledge, skills, expertise, policy and practice developments across its broad portfolio, that can act as a solid foundation for the introduction of an additional duty and a reinvigoration of the Community Safety Partnership status.

Blaenau Gwent County Borough Council

27. We believe that wherever possible, existing partnerships and structures should be used to bring relevant organisations together to prevent and tackle serious violence. While Community Safety Partnerships are not the only partnership to have responsibility for drawing together relevant partners, as an established multi-agency partnership they have a vital role to play in tackling and preventing serious violence.

28. That is why we intend to introduce legislation to amend section 6(1) of the Crime and Disorder Act 1998 which sets out the strategies Community Safety Partnerships must formulate and implement, to explicitly include serious violence. By ensuring Community Safety Partnerships formulate and implement a serious violence strategy it would ensure that it remains a priority at a local level. Combining this amendment to the Crime and Disorder Act, with a new duty on specific organisations or authorities, would also enable Community Safety Partnerships to raise the issues to a higher strategic level as necessary given that in some local areas there are a significant number of Community Safety Partnerships and this may make it difficult for other partners to engage with them effectively.

Option Three: A voluntary non-legislative approach

29. 23% of online respondents supported option three[footnote 5]. Of the respondents who provided information about their professional sector and favoured one of the three options, option three was favoured by the voluntary and community sector and the education and childcare sector.

30. A voluntary non-legislative approach was the option in the consultation document that the fewest respondents felt would be the best approach to tackle and prevent serious violence. Some (25) respondents used the consultation to provide detail about voluntary approaches being taken in their areas, and while there are some voluntary arrangements which work well, a high number of respondents (87) highlighted concerns that without legislation the partnerships in some areas would be weaker than in others.

31. On 18 June 2019, the Home Secretary announced the provisional allocation of £35 million to Police and Crime Commissioners in 18 areas to set up Violence Reduction Unit. These will bring together community leaders and other key partners with police, local government, health and education professionals to identify the drivers of serious violence and develop a response to them. Violence Reduction Units will ensure there is effective planning and collaboration to support a longer-term approach to preventing violence. The proposed duty will complement and assist the Violence Reduction Units in their aim of preventing and tackling serious violence, by providing a strategic platform with the right regulatory conditions to support successful delivery of this multi-agency approach, including through the extended set of partners on whom the duty will fall.

32. We have been working closely with other Government departments and partner agencies, including the police and existing Violence Reduction Units, to develop the core set of requirements that those in receipt of Violence Reduction Unit funding will need to deliver. This has allowed us to provide a clear steer to local areas on how we expect Violence Reduction Unit funding to be applied.

Additional considerations

Inspection, accountability and enforcement

33. It is clear from the majority of online responses to the consultation that responsible authorities subject to the duty would best be held to account through inspections, either joint thematic inspections or by individual inspectorates through their existing inspection powers. We will undertake an informal consultation with inspectorates to scope options for an inspection regime. For example, through joint thematic inspections.

34. There will also be an expectation on relevant agencies, including for any public authorities for which there is no existing inspection body, to publish details of how they carry out their responsibilities under the duty, for example through existing monitoring arrangements or through local multi-agency plans. Finally, the Government will continue to consider what enforcement action for non-compliance might be required.

Guidance and support for local areas

35. The Government will publish guidance supporting the new legislation to assist statutory agencies to effectively deliver a multi-agency public health approach. The guidance will highlight best practice and explain how different partnership models can work in practice, including with Violence Reduction Units. In doing so, we will emphasise the importance of involving the voluntary, community and faith sectors, recognising the key contribution that they are able to make in this area, but also allowing for flexibility to ensure that appropriate organisations are working together to tackle the specific challenges faced across England and Wales.

Annex A: Summary of responses

1. A total of 225 responses to the consultation paper were received[footnote 6]. Of the 221 respondents who answered the question[footnote 7], 57 (26%) reported that their agency or organisation was in the local government sector, 31 (14%) reported their organisation was in the voluntary and community sector and 29 (13%) reported their agency or organisation was in the police sector.

2. The consultation document provided three options for ways to tackle and prevent serious violence. Of the responses provided to the consultation paper, while there was overall support for the vision to use a multi-agency approach to tackle and prevent serious violence, there was no single option proposed to achieve this that garnered a majority of support.

Table 1: Options Preference

| Option preference | % of respondents |

|---|---|

| Option 1 only | 37% |

| Option 2 only | 40% |

| Option 3 only | 23% |

For each option, the table includes the response for only those that have not responded “Yes” to any of the two alternative options. This table excludes any other responses other than “Yes” and “No”, “such as “maybe” and “possibly”.

3. The below chart shows the options favoured by each organisation or agency, where respondents indicated a preference and selected a profession or area in which their organisation worked.

Table 2: Option preference by organisation/agency

A bar chart showing the percentage of organisations/agencies that preferred each of the 3 options.

This chart excludes, those that answered yes to multiple options.

Responses to specific questions

Part 1: General questions

What sector does your agency/organisation represent?

Table 3: Number of responses by agency/organisation

| Agency/Organisation | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Criminal Justice | 13 |

| Education and child care | 26 |

| Fire | 3 |

| Health and social care | 22 |

| Housing and construction | 5 |

| Local government | 56 |

| Member of the public | 6 |

| Multi Agency boards | 16 |

| PCC | 10 |

| Police | 29 |

| Research | 4 |

| Voluntary and community sector | 31 |

| Unknown | 4 |

4. Of the 221 respondents who answered the question, 57 (26%) reported that their agency or organisation was in the local government sector, 31 (14%) reported their organisation was in the voluntary and community sector and 29 (13%) reported their agency or organisation was in the police sector.

Is your agency/organisation part of or does it work with any existing multi-agency partnership such as a Community Safety Partnership?

5. 76% of those responding to the question reported that their organisation or agency either is currently part of, or works with, an existing multi-agency partnership.

Where is your agency/organisation based?

6. With the exception of Northern Ireland, responses were received from those working in organisations or agencies across the UK. The largest number of responses for any one area came from London with 62 (29%) of the 216 respondents who answered the question. The fewest responses received in England and Wales came from Yorkshire and the Humber with only 6 (3%).

Table 4: Percentage of responses by region

| Region | Percentage of responses |

|---|---|

| East Midlands | 7% |

| East of England | 10% |

| London | 29% |

| North East | 4% |

| North West | 9% |

| Scotland | 1% |

| South East | 11% |

| South West | 9% |

| Wales | 7% |

| West Midlands | 11% |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 3% |

What agencies/organisations do you work closely with to prevent and tackle serious violence in your area? Multiple answers possible

7. Of the respondents that indicated they work with other organisations in preventing and tackling serious violence, the most commonly selected organisations or sectors were: police, voluntary and community sector, local government and health and social care. However, the majority of respondents indicated they worked with all the organisations listed.

Table 5: Number of respondents working in collaboration with other organisations

A bar chart showing the number of respondents working in collaboration with other organisations. Police: ~180. Voluntary and community sector, local government and health and social care ~160. Education and childcare: ~150. Criminal justice: ~140.

Part 2: Current work in the area of serious violence

Does your agency/organisation currently have activities in place to prevent/tackle serious violence?

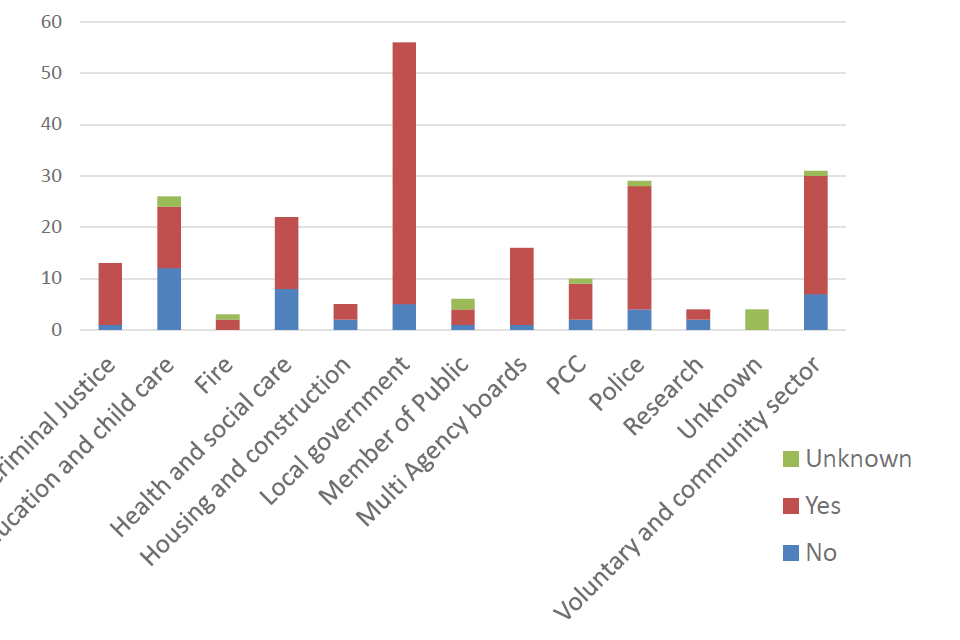

8. The majority of those responding to this question (79%) answered yes to this question that there are currently activities within their organisation or agency to prevent and/or tackle serious violence. The chart below provides a breakdown per agency or organisation responding. Out of the 24 respondents from the education and childcare sector that provided an answer, 50% reported that their agency/organisation does not currently have activities in place to prevent/tackle serious violence.

Table 6: Number of respondents with current activities in place

A bar chart showing the number of respondents with current activities in place.

If you are currently working in an agency/organisation with an interest in serious

violence:

What kind of activity do you undertake in preventing and tackling serious violence?

Multiple answers possible.

9. The most commonly raised activities respondents answering this question said that they were undertaking were early intervention and preventative initiatives for root causes e.g. education and funding for intervention and prevention services e.g. youth services and drug/alcohol centres.

If you currently do not have activities in place to prevent/tackle serious violence, what activities do you feel would be beneficial to address serious violence in your area?

Open question.

10. Of those responding to this question, some raised concerns in their responses that preventing or tackling serious violence was not part of their role and took the opportunity to express their dislike for the policy proposals outlined in the consultation document. The most common point raised in these responses was that preventing or tackling serious violence was not part of the role of the individual responding or organisation (for example educational or health professionals).

11. Of those responding suggesting activities that would be beneficial, the suggestions included early intervention and prevention initiatives, including increased funding to support initiatives and further funding for the police.

Early intervention programmes to reduce the known risk factors among vulnerable children and young people.

Central Bedfordshire Council

Local Authority ring fence funding on prevention services aimed at preventing underlying causes of serious violence, and in particular drug treatment services

Office of the Durham Police & Crime Commissioner

Part 3: Questions posed in the body of the consultation document

Do you agree that the vision and focus for a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence is correct? If not, please explain why.

12. The clear majority of respondents (86%) to the consultation indicated support for a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence.

13. Of those providing an open question response, the majority reiterated their support for a multi-agency approach or from those providing positive work underway in their area or supporting academic research.

14. The most commonly raised reasons for not supporting the vision for a multi-agency approach to preventing and tackling serious violence were the concerns that it does not focus on the broader or underlying issue causing serious violence, or concerns around the lack of funding or time organisations and staff have.

I think more needs to be done at the early intervention stage by other agencies in conjunction with police there are opportunities that are missed to divert people getting involved in serious violence

Met Police Officer

… we do not consider that the vision developed in this consultation fully represents a public health approach to serious violence. The public health approach considers serious violence as an epidemic that has to be treated with the same whole system preventative approach as an epidemic disease.

Safer London

Do you consider that Option One would best achieve the consultation vision?

Please explain why.

15. 37% (61) of respondents stated that Option One was their preferred option. The most commonly raised explanations for either agreeing or disagreeing with Option One were that existing duties and legislation were sufficient to tackle serious violence (39) or a dislike for taking a legislative approach. Respondents also raised concerns around the lack of funding or time organisations and staff have.

16. Respondents also expressed that Option One would allow for local flexibility in deciding how to implement and that it could have a positive impact on consistency across England and Wales in terms of the prioritisation and accountability in organisations for tackling serious violence. A number of respondents also highlighted the positive work they are doing with regard to tackling serious violence or suggestions for how Option One could work in their area.

It is believed that the existing duty to consider crime and disorder in all aspects of service delivery is sufficient and a further specific duty would simply duplicate this.

Oldham Community Safety & Cohesion Partnership

I think that the partnership landscape is complex and becoming ever more so. Statutory footing would ensure that partners had clear deliverable frameworks and would give the ability to challenge and hold each to account.

Avon & Somerset Police, Safeguarding Team

“This enables agencies to prioritise the issue of serious violence but to be creative in creating bespoke multi agency solutions that work for the local area”

Cheltenham Borough Council, Strategy & Engagement

We consider Option One to be the best means of achieving the consultation vision. Establishing a new legal duty to support a multi-agency approach provides both focus and accountability for partners to prevent and tackle serious violence.

Office of Gwent Police & Crime Commissioner

Do you consider the specific agencies listed in Schedule 6 to the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 the right partners to achieve the consultation vision?

If not, please explain why.

17. Of the 185 respondents who provided a definitive “yes” or “no” to this question, 111 felt that the agencies listed in schedule 6 were the right partners to achieve the consultation vision, 74 respondents did not. However, 107 respondents then went on to answer the second part of the question. The majority of those responding to this question felt that the list of organisations as set out in Schedule 6 needed to be updated. The most commonly raised suggestions for additional partners to those already included in Schedule 6 were for the voluntary, community and faith sector (23), clinical commissioning groups (19) and the fire and rescue service (15).

There is a significant role for the wider voluntary, community and faith sector in relation to delivering sustainable long-term outcomes for the vision.

Sefton Council, Communities Team

CCG’s should be an integral core member, if they don’t commission the right services (with the most effective measures), there could be a fractured offer across the piece.

Avon & Somerset Police, Safeguarding Team

Consideration may also need to be given to including Fire and Rescue Authorities given their role in prevention.

Welsh Local Government Association

Do you consider that Option two would best achieve the consultation vision?

Please explain why.

18. 40% of respondents felt that option two would best achieve the consultation vision. However, there were concerns expressed including the lack of funding or time organisations and staff have. There were also concerns raised about the inconsistency, both geographically and in terms of reach, that community safety partnerships had, that the option targeted the wrong agencies or made suggestions for alternative target agencies and that the current duties and legislation were sufficient to tackle serious violence.

19. Again, some respondents provided examples of how they believed option two could work and of positive work underway in their area or organisation.

As noted in the consultation document, the geographical reach of Community Safety Partnerships differs across the country and in many cases means that they are not the optimum partnership model as decision making may be more effective at a higher strategic level.

Devon County Council, Communities Team

…partnership established would be insufficient to achieve consistency cross sector. This would not be in line with existing practices including the partnership established through the OPCC. There would be concerns that this would lead to geographical inconsistency by not harmonising the approach across PCC areas.

East Sussex County Council, Communities Team

Community Safety Partnerships are in a key position to challenge serious violence as a contextual safeguarding arena. However, the issue cannot be addressed just through these partnerships and need health providers and education, amongst others, to work effectively together, to avoid exclusion and put in services at the Early Help level.

Devon County Council, Communities Team

Should the list of Statutory Partners in Community Safety Partnerships be added to so that they can adequately prevent and tackle serious violence in local areas?

If so, what organisations?

20. The majority of those responding believed that the list of statutory partners in Community Safety Partnerships should be added to with 116 respondents definitively responding “yes” to the first part of this question and 68 responding “no”. However, 131 respondents went on to provide a further response, with the most commonly seen suggestions being educational establishments (schools, colleges etc), the voluntary, community and faith sector and residential homes and social landlords.

Education – particularly when working on these issues due to the links between gang involvement and exclusions/off rolling. Working with young people in PRUs is key when considering this agenda.

Safer Wolverhampton Partnership, City of Wolverhampton Council

The communities and the young people affected by violence who are not represented in any of the available options.

MAC UK

If option 2 is selected, we feel that a wide range of third sector organisations must be involved, including equality organisations

Diverse, Cymru

All housing providers should have a greater statutory role in crime prevention and all health agencies should have more explicit duties placed on them with regard to information and data sharing.

Redditch Borough Council & Bromsgrove District Council

Do you consider that Option Three would best achieve the consultation vision?

Please explain why.

21. This was the least preferred option with only 23% of respondents believing that option three would be the best approach. The most frequently cited reasons for it not being the best approach were that the respondent either did not think that a voluntary approach to tackling serious violence would work as it was weak or that legislation was needed.

There was no support for a voluntary, non-legislative approach. In the current financial climate where resources are stretched so thinly it was felt that there needed to be an element of compulsion and if there was not, then organisations would simply opt out.

Northumbria Police

This would be a backward step. We need the strength of legislation to tackle a national problem

Haybrook College

In order to engage all necessary partners included within this vision we believe a requirement to participate is necessary.

Office of the Police Fire & Crime Commissioner for Essex

What other measures could support such a voluntary multi-agency approach to tackling serious violence, including how we ensure join up between different agencies?

22. Of the 150 people/organisations responding to the question about what other measures could support a voluntary multi-agency approach, a number of points were raised including funding, information and intelligence sharing, the requirement for a strong and clear lead or governance structure to be in place and the need for timely and therapeutic interventions.

23. As with previous options, some respondents provided examples of work being done, and models used within their area or by their organisation.

Easier information sharing processes and regular meetings to discuss areas of concern.

OneLife Suffolk

Have a national body lead that is recognised and has authority. Doesn’t need to be directly linked to government like Home Office.

Met Police Officer

Part 4: Questions about the consultation options and their possible impact

24. Many of the responses provided to the questions in Part 4 of the consultation document (time/resource, staff and other costs) have been used to inform our impact assessment which has been published alongside this response document. For further details please see the published impact assessment.

Option 1: a new duty on specific organisations to have due regard to the prevention and tackling of serious violence

What, if any, benefits do you envisage under the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

25. Of the respondents that envisaged benefits under option one, the most commonly selected benefits were a more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at the local level, improved collaboration with other organisations and improved outcomes for victims and reductions in serious violent crime.

Table 7: Benefits of Option 1

| Benefit | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| A more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at a local level | ~ 110 |

| Improved collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 100 |

| Improved outcomes for victims | ~ 95 |

| Reductions in serious violent crime | ~ 95 |

| Improved outcomes for offenders | ~ 80 |

| Improved organisational processes | ~ 60 |

| Reduction of pressure upon time | ~ 20 |

| Less resources or costs to your agency/organisation | ~ 20 |

What, if any, disadvantages do you foresee arising from the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

26. Most respondents ticked ‘no’ for this question and did not identify any disadvantages with this option. Where concerns were raised these included potential time pressures and costs.

Table 8: Disadvantages of Option 1

| Disadvantage | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| Increased time pressures on your organisation | ~ 105 |

| Increased resources or costs to your organisation | ~ 100 |

| Diversion of spending/resources away from other areas | ~ 85 |

| Local variation in preventing and tackling serious violence | ~ 70 |

| Issues around collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 55 |

| Worsening of organisational processes | ~ 35 |

| Poor outcomes for victims/offenders | ~ 30 |

Option Two: New duty through legislating to revise Community Safety Partnerships What, if any, benefits do you envisage under the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

27. As with option one, of the respondents that envisaged benefits under option two the most commonly selected benefits were improved collaboration with other organisations and a more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at the local level. However, most respondents ticked ‘no’ for the listed benefits of option two.

Table 9: Benefits of Option 2

| Benefit | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| Improved collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 105 |

| A more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at a local level | ~ 95 |

| Reductions in serious violent crime | ~ 85 |

| Improved outcomes for victims | ~ 80 |

| Improved outcomes for offenders | ~ 75 |

| Improved organisational processes | ~ 65 |

| Less resources or costs to your agency/organisation | ~ 20 |

| Reduction of pressure upon time | ~ 15 |

What, if any, disadvantages do you foresee arising from the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

28. Most respondents ticked ‘no’ for this question and did not identify any disadvantages with this option. Where concerns were raised these included potential time pressures and costs.

Table 10: Disadvantages of Option 2

| Disadvantage | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| Increased resources or costs to your organisation | ~ 85 |

| Increased time pressures on your organisation | ~ 85 |

| Local variation in preventing and tackling serious violence | ~ 65 |

| Diversion of spending/resources away from other areas | ~ 60 |

| Issues around collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 55 |

| Worsening of organisational processes | ~ 35 |

| Poor outcomes for victims/offenders | ~ 25 |

Option Three: A Voluntary Non-legislative approach

What, if any, benefits do you envisage under the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

29. As with options one and two, of the respondents that envisaged benefits under option three the most commonly selected benefits were improved collaboration with other organisations, a more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at the local level and improved outcomes for victims. It should be noted that this option had fewer responses indicating benefits compared with options one and two.

Table 11: Benefits of Option 3

| Benefit | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| Improved collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 45 |

| A more consistent approach in preventing and tackling serious violence at a local level | ~ 40 |

| Improved outcomes for victims | ~ 40 |

| Improved outcomes for offenders | ~ 35 |

| Reductions in serious violent crime | ~ 30 |

| Less resources or costs to your agency/organisation | ~ 25 |

| Improved organisational processes | ~ 15 |

| Reduction of pressure upon time | ~ 15 |

What, if any, disadvantages do you foresee arising from the proposed option?

Multiple answers possible.

30. Most respondents ticked ‘no’ for this question and did not identify any disadvantages with this option. Where concerns were raised, these included local variation in preventing and tackling serious violence; and issues around collaboration with other organisations.

Table 12: Disadvantages of Option 3

| Disadvantage | Total (volume) |

|---|---|

| Local variation in preventing and tackling serious violence | ~ 70 |

| Issues around collaboration with other agencies/organisations | ~ 70 |

| Increased time pressures on your organisation | ~ 55 |

| Poor outcomes for victims/offenders | ~55 |

| Increased resources or costs to your organisation | ~50 |

| Worsening of organisational processes | ~ 45 |

| Diversion of spending/resources away from other areas | ~ 45 |

Final questions relating to all options, for all respondents

How can the organisations subject to any duty or voluntary response be best held to account?

31. Of the 196 respondents to this question, the majority thought that organisations subject to a duty or a voluntary response would be best held to account through inspections (either joint or by individual inspectorates), as suggested in the consultation document.

32. Other responses given included suggestions of self-reporting for organisations (for example through annual reports or self-assessments), through reporting against clearly defined performance measures or via existing accountability regimes and mechanisms.

Through inspection processes in addition to performance frameworks that are robustly managed and monitored

Office of Police & Crime Commissioner, Cleveland

Supported by a meaningful national performance framework that measure positive impact over action and allows for consistency and baselining to identify good practice and struggling areas.

Northamptonshire Police

Submission of self-audit tools, action plans and remedial updates

Safer North Hampshire

Aside from your answers given in previous sections, are there any other considerations that you would like to raise regarding one or more of the proposed options?

Open question.

33. Of the 115 responding to this question, the most commonly raised response was, as seen in previous questions, concern around funding or time pressures faced by their organisation – a number of respondents also expressed the view that greater accountability or leadership was needed from the Government.

34. Again, a number of respondents took the time to inform us of local approaches being taken or to provide research or data.

Offline Responses

35. Alongside the online survey tool, we received a number of responses directly through the published email address inbox and one through the postal address.[footnote 8] Of these, 63 responses were submitted in a format incompatible with the overall analysis and as such we have had to consider these separately here.

36. Of the 59 respondents who provided information about the sector that their agency/organisation represented, 25% where from the police sector, 22% from the local government sector, 12% where from the health and social care sector, 8% from both the education and childcare sector and the voluntary sector and 5% from the criminal justice sector. 18% were categorised as “other”, this included members of the public, unions, the Children’s Commissioner and housing bodies.

37. Of the 81 offline responses the majority, 78%, explicitly stated that they supported tackling and preventing serious violence through multi-agency working.

38. Where respondents expressed support for one of the options outlined in the consultation document, 14 respondents agreed with or supported option one, 15 respondents supported option two and 15 respondents supported option three. Seven respondents expressed support for a combination of options, for example option one and option two, option one and option three or option two and option three. 39. Some respondents also expressed disagreement for the options outlined in the consultation paper, with 21 disagreeing with option one, 15 disagreeing with option two and 13 disagreeing with option three.

40. Those responding offline, raised similar concerns to those responding online. Nine respondents did not support the adoption of a legislative approach and 10 respondents suggested that existing duties or legislation were sufficient to tackle and prevent serious violence. 20 respondents suggested that they needed further clarity on how the options would work and 19 raised the need for best practice sharing or guidance.

41. Regarding how organisations subject to any duty or voluntary response can be best held to account, 16 respondents provided an opinion. Seven advocated for joint or individual inspections, four suggested police and crime commissioners have governance and oversight of any duty, two respondents suggested accountability through clear performance measures and reporting and two respondents suggested that accountability should take place via existing accountability regimes.

42. Additional suggestions raised by those responding offline included the need for early intervention, the need to involve the community, community groups and young people and the view that any response to serious violence should be based on evidence and research.

Annex B - Methodology

1. The consultation questions were developed by Home Office policy officials and analysts. Economists were involved in the questions relevant for the Impact Assessment.

2. We received a total of 288 responses to the consultation. 207 responses were received via the Home Office online survey tool, and 81 survey responses were received offline either by completed offline questionnaire, letter or email. 18 of these responses had been filled in to mirror the consultation document and these were added to the 207 and analysed these 225 were together. 63 responses have been analysed separately as “offline responses”. The analysis of the offline responses is further described in Annex A.

3. As the consultation was open for anyone to respond, it was not possible to calculate response rates.

4. Home Office analysts did not weight the findings as it was not possible to determine with confidence what responses were submitted in personal or professional capacity. In addition, the weighting would be arbitrary as there are various factors that could influence how much importance could be given to difference responses.

5. The open-ended questions in the online questionnaire and the other responses as submitted by email or post were coded into various themes to facilitate the analysis of large volumes of qualitative responses. The responses were predominantly coded following a ‘bottom-up’ approach in which the codes were developed based on the responses. The final coding framework as derived from the online coding then formed the basis for the offline coding, alongside any new codes that emerged from the analysis of the offline data.

6. Through this reiterative process a framework of common themes emerged, which were subsequently used for the analysis.

7. As a guiding principle, for each question the most frequently occurring responses were identified and reported accordingly.

8. The closed questions relating to the three options and their costs and benefits were analysed in Excel by two Home Office analysts and this analysis was subsequently checked for quality by two Home Office analysts not involved in the analysis previously.

9. The open questions relating to the costs and benefits of the three options were coded and analysed by one Home Office analyst in Excel. One Home Office analyst not involved in the coding and analysis checked a random sample of 30 per cent of the coded responses and the final analysis.

10. The other open questions of the online questionnaire and offline responses as reported in this document were coded and analysed by policy officials in Excel. The coding was conducted by two policy officials for each set of online and offline responses, and one Home Office analyst not involved in the coding checked a random sample of approximately ten per cent of the coded responses.

11. The findings as presented in this document exclude the blank responses.

12. The findings from the open-text responses as presented in this document were not broken down by geography or sector due to a low number of responses per theme identified.

Annex C: Consultation principles

The principles that government departments and other public bodies should adopt for engaging stakeholders when developing policy and legislation are set out in the consultation principles.

-

This includes only online responses from those that did not respond “Yes” to any of the two alternative options, it also excludes any other responses other than “Yes” and “No”, “such as “maybe” and “possibly”. ↩

-

117 respondents answered “yes” to this question and 72 responded “no”. ↩

-

This includes only online responses from those that did not respond “Yes” to any of the two alternative options, it also excludes any other responses other than “Yes” and “No”, “such as “maybe” and “possibly”. ↩

-

38. ↩

-

This includes only online responses from those that did not respond “Yes” to any of the two alternative options, it also excludes any other responses other than “Yes” and “No”, “such as “maybe” and “possibly”. ↩

-

We received a total of 288 responses to the consultation. 207 responses were received via the Home Office online survey tool, and 81 survey responses were received offline either by completed offline questionnaire, letter or email. 18 of these responses had been filled in to mirror the consultation document and these were added to the 207 and these 225 were analysed together. 63 responses have been analysed separately as “offline responses”. ↩

-

Excludes 4 responses that did not answer this question. ↩

-

We received 81 offline responses either directly through the published email address inbox and one postal response. 18 of these responses had been filled in to mirror the consultation document and these 18 are included within the 225 responses considered within the overall analysis as set out in the previous chapter. ↩