Summary of responses to the consultation Smarter Regulation: Fire safety of domestic upholstered furniture

Updated 22 January 2025

1) During the consultation period, officials from the Office for Product Safety and Standards held 23 stakeholder meetings to present and discuss the proposals, with the view to supporting stakeholders’ understanding of the new approach proposals in order to elicit feedback on them. These meetings included large-scale presentations with businesses and trade associations, group discussions with the Fire Services and Trading Standards, and individual stakeholder meetings.

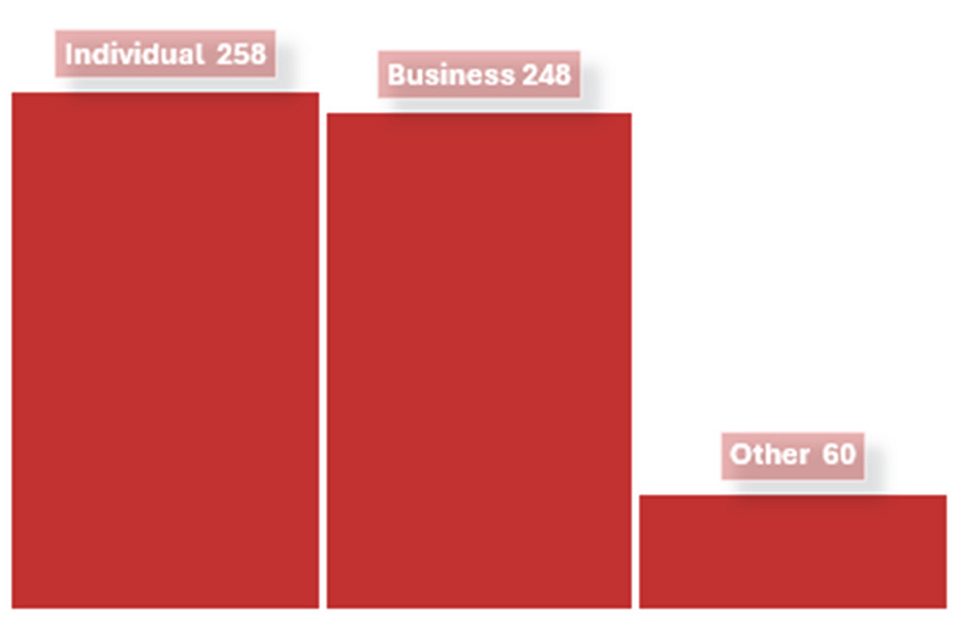

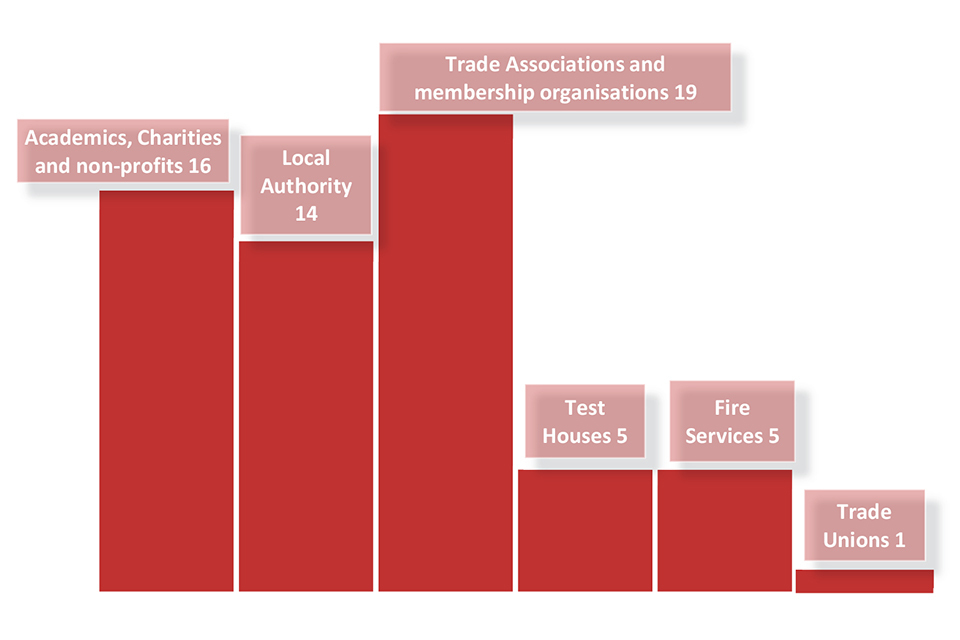

2) 566 written responses to the consultation were received, with 455 responses received via an online platform (Qualtrics) and 111 by email. The majority of responses came from businesses and individuals, as broken down in Fig. 1 and Fig. 2.

3) A campaign organised by re-upholsterers that was signed by 5793 individuals was also submitted and, in addition, views were expressed and collated via the Eco-chair website which hosted the campaign.

Figure 1: Responses received

Figure 2: Other organisations

4) Each individual response was carefully considered and all feedback within a response was analysed. A detailed overview of stakeholder feedback is set out in themes, which include the consultation questions relevant to that theme, and a summary of responses to those questions.

Theme 1 – Defining responsibilities, scope and definitions

Relevant consultation questions and summary of responses

Question 2: Do you have any comments on the economic operators included as having obligations? Are the associated obligations appropriate? Are there any economic operators that we have not considered?

5) Many respondents felt that component suppliers should be responsible for the testing and compliance of the components they supply as well as for providing information on CFRs used. Respondents raised that this is particularly important for small businesses, manufacturers of bespoke products and re-upholsterers who do not have the resources or expertise to carry out testing or assess the chemical safety of materials.

6) Some responses expressed confusion around retailers selling their own branded products and whether this makes them a manufacturer. Similarly, the distinction between re-manufacturing and re-upholstery was raised as an area of potential ambiguity.

7) Many respondents wanted greater clarity on ‘further suppliers’ and how they relate to the term ‘distributors’ which is used in other product safety legislation. It was also suggested that legal responsibilities for waste handlers, furniture recyclers, repair cafes, contract suppliers, suppliers of furniture as part of a holiday let and charities that donate should be more clearly captured. Some respondents asked for more detail on what further suppliers should do to ensure or verify compliance, especially after transport and storage. Some respondents suggested manufacturers and importers could share Declarations of Conformity with further suppliers so that they are confident they are procuring and supplying compliant products.

8) A few respondents highlighted that online marketplaces, fulfilment houses and social media platforms should have clear obligations in line with other suppliers of furniture, and the potential need for a responsible person established in the UK. There were also questions about whether the new approach would apply to hobbyists or micro part-time businesses who sell on online marketplaces.

Question 3: Do you agree with proposals for which products should fall within scope of the new approach? Please provide as much evidence as possible to support suggestions.

Question 4: Are any of the product types referred to as being in or out of scope ambiguous, and would they benefit from further definition?

9) The majority of respondents supported the proposed products that fall in scope. There was strong support for removing the specified baby products from scope, although some respondents questioned the proposal on the grounds of fire safety. Separately, the amount of time children spend in adult beds and sitting on sofas was raised with the implication that removing baby products from scope to protect them from exposure to CFRs would only have a partial impact.

10) Some respondents said that CFRs would likely still be required to meet the General Product Safety Regulations 2005 (GPSR). A few respondents suggested keeping baby products in scope and specifying that CFRs cannot be used would be preferable and ensure fire safety and chemical safety of those products. Conversely, some respondents also suggested a number of additional baby products for removal from scope. These included: Highchairs, chair mounted seats and table mounted seats, travel cots, baby walkers, cribs and cradles.

11) A few respondents highlighted that the proposed dimensions (<75 cm x 190 cm) for mattresses coming out of scope would allow some adult mattresses to come out of scope as well. A number of responses said that mattress toppers/pads should be explicitly in or out of scope using the same mattress size limit. Respondents also suggested that definitions for mattress toppers/pads should follow BS7177. A number of respondents expressed the view that mattresses should be removed from scope entirely because they are covered by bedding which, if ignited, would overwhelm a mattress’ fire resistance.

12) Some respondents recommended that size cut-offs should be more consistent across the affected products and commented that more emphasis should be placed on volume. Some responses said that the cut-off for scatter cushions was too small, and others that the cut-off for bean bags and floor cushions was too large. It was also stated that the use of multiple scatter cushions together could create a potential fire safety risk where they were being removed from scope. Linked to this were concerns about unmodified foam being used in cushions and pet furniture that was below the size cut-off, where that was previously not permitted. A few respondents also asserted that clear guidance on GPSR requirements will be necessary for those products coming out of scope and for products with size cut-offs.

13) A number of responses highlighted that consideration should be given to upholstered office furniture, as it is reasonably foreseeable that office furniture intended for a contract setting will be used in the home, given the increase in home working. Concerns were also raised about the use of hospital beds, hospital chairs and other upholstered care products, or products designed for use by people with disabilities in domestic settings, and whether they are in scope, especially because they are not always supplied by the NHS and are available for the general public to purchase. In addition, one respondent highlighted the additional fire risk posed by the storage of products being removed from scope.

14) Many responses, predominantly from re-upholsterers and those manufacturing one-off, bespoke products, stated that products manufactured using traditional/natural materials, such as cotton and wool, should be out of scope, owing to the purported inherent fire resistance of those materials. In contrast, some respondents challenged this view, asserting that materials like cotton are susceptible to smouldering and open-flame ignition sources.

15) A number of responses requested more clarity on the exempted baby products, as well as the status of cushion inners, foam pillows, fabric walling, divan beds, upholstered footboards and headboards, throws and loose and stretch covers. Some responses queried how the proposals applied to modular mattresses designed for children.

Question 5: Do you agree that outdoor upholstered furniture should remain in scope of the regulations, unless an outdoor upholstered product warning label is affixed?

16) While a majority of respondents indicated support for the proposal, some did not think it sufficiently mitigated the risk that consumers will use or store the products inside, where they would pose a significant fire risk. Respondents stated that there was a fire safety risk where outdoor products are used on balconies and walkways within residential flats. It was also pointed out that manufacturers are able to condition-test outdoor furniture and that they can be made fire safe in a way that does not deteriorate as a result of being stored outside.

Question 6: Do you agree with the proposal to retain the policy of exempting all products manufactured prior to 1st January 1950 from the regulations?

17) Responses widely supported the proposal but a few respondents raised concerns about how the date of manufacture can be determined to establish manufacturing prior to 1950. Some respondents suggested that if pre-1950s products are re-upholstered using modern materials, including polyurethane foam, those materials should be compliant.

Question 18: Do you have any feedback on the list of locations that are included and excluded from the definition of private dwelling that sets the scope of the regulation?

18) Whilst there was general support for the locations proposed as being in and out of scope of the definition of private dwelling, some respondents felt that there are still areas between the proposed definition of domestic premises under the new approach and settings where the Regulatory Reform (Fire Safety) Order 2005 applies that would benefit from greater clarity. Respondents requested further clarity in respect of HMOs, lodgings and boarding arrangements, accommodation provided for the armed forces, private rooms in a residential care home (where some of the furniture may be hospital grade), specialized housing (such as sheltered accommodation, extra-care housing and other similar housing), student accommodation, park homes and holiday parks, hotels, Bed & Breakfasts, Airbnbs and other short term lets.

Question 19: Do you have any further comments on the definitions?

19) Within the proposed essential safety requirements, the following terms were highlighted as vague and open to interpretation: burn slowly, readily ignite, self-extinguish, flaming ignition source, chemical flame retardant, jeopardise and other person.

20) Within the proposed Flame Retardant Technology Hierarchy, the following terms were considered ambiguous: inherently flame retardant and inherently flame retardant materials.

21) In relation to product testing, conformity assessment and technical files, respondents requested clarity on: product in its final form, representative sample, designated standard, periodic testing and datasheet.

22) In relation to proposed provisions on re-upholstery (Part 3 of draft regulations), respondents requested clarity on: re-upholsterer, refurbishment, re-cover and hobbyist.

23) In relation to scope and implementation, the following terms were raised: bespoke, scatter cushion, interliners, outdoor, second-hand, online marketplaces and place on the market.

Theme 2 – Product compliance requirements

Relevant consultation questions and summary of responses

Question 7: Do you agree with the proposed essential safety requirements? If not, please provide evidence to support your assertions.

24) The majority of respondents supported the introduction of ESRs, commenting that the approach aligns with other modern product safety legislation, allows a degree of flexibility in the regulations, supports innovation and takes account of a wide range of ignition sources.

25) Some respondents were concerned that removing testing requirements from the regulations in favour of new voluntary standards will lead to uncertainty in how to comply, inconsistency in product compliance, reduced fire safety and an uneven playing field. The majority of respondents said that the success of the ESRs depends on the new British Standards and that without them, the ESRs could be considered vague and open to interpretation.

26) A few respondents were concerned that the draft ESRs allow for a product to ‘burn slowly’, potentially increasing toxic smoke release and reducing escape time. Other responses thought the ESRs should not apply to all products in scope and variations should apply to certain products such as cushions and seat pads. Some responses expressed alternative views that the new outcome-based approach would not maintain fire safety or reduce CFRs.

Comments in respect of open-flame testing

27) Many respondents raised concerns about the inclusion of the open-flame ignition resistance requirement. They thought that this would not enable a reduction in the use of CFRs. It was suggested the approach taken should mirror the smoulder tests in Europe and the USA and follow the recommendation made by the Environmental Audit Committee in its 2019 report on Toxic Chemicals in Everyday Life. A few respondents cited data from the World Health Organization European Health Information Gateway which shows that the fire death rate for the United Kingdom is not significantly better than in other comparable countries that do not impose filling materials and flaming ignition flammability standards.

28) Other responses said that the US model in Technical Bulletin 117-2013 provides no meaningful fire safety benefit, as resistance to ignition by a smouldering cigarette is less important today due to the prevalence of reduced ignition propensity cigarettes, and that it is important to maintain both flaming and non-flaming ignition sources to maintain fire safety.

29) Some respondents mentioned that the open-flame requirement does not recognise the inherent flame retardancy of certain natural materials which currently only need to meet a smoulder test under the FFRs.

Comments in respect of the ESR for foam (including comments on non-foam filling materials)

30) Many respondents felt that a separate ESR for foam undermines the final item testing approach and that only the exterior should be fire resistant while others felt that a barrier material could protect the foam within the product, negating the need to test it separately. Various views were shared on the level of ignition resistance of foam, most prominently that the current Crib 5 test leads to excessive use of CFRs. Some responses said more broadly that foam will have to contain CFRs if it is to pass open-flame ignition source tests, which will affect recyclability of products and the attempts to promote the circular economy. Some stakeholders felt that the ignition resistance of foam (and all other filling materials) was futile as a cover material catching fire would overwhelm the fire resistance capability of the foam filling.

31) Many other stakeholders said that there should be a requirement for all filling materials to be tested, to avoid industry pivoting to equally flammable non-foam fillings, while some said that natural filling materials should be treated differently.

Comments in respect of the ESR for CFRs

32) There was widespread support for increasing safety in respect of CFRs. Some respondents raised the interactions with wider Government legislation on chemical safety and suggested that existing chemicals legislation could be more robust and that amendments were required to protect consumers and those working in the furniture industry from potentially harmful chemicals.

33) It was requested by some respondents that the Government takes a specific view on what CFRs should, and should not be permitted for use in furniture, while other respondents recommended that all CFRs should be banned from use in furniture, citing evidence that they provide negligible delay to fire ignition and increase smoke toxicity when a product burns.

34) Many respondents expressed the view that furniture assemblers and re-upholsterers should not be responsible for the safety of the chemicals, as they do not apply them to components and often do not even know what they are.

35) Respondents asked for clarity on the meaning of terms such as ‘jeopardise the safety of any consumer’ and ‘foreseeable behaviour’ to support compliance and enforcement.

Comments in respect of conformity assessment, accreditation, testing and new British Standards

36) Respondents called for further guidance to support conformity assessment, with one respondent recommending the introduction of a conformity assessment body to bring greater confidence that manufacturers have met the requirements placed on them.

37) Others commented that ISO 17025 accreditation is disproportionate and that the definition of ‘accredited laboratory’ should include in-house test facilities that are audited or assured by the United Kingdom Accreditation Service (UKAS) accredited test houses, and that selected flammability tests should be specified on the test house’s schedule of accreditation. Counter views presented did support the proposal, noting the lack of testing oversight under the existing regulations.

38) Most respondents highlighted the need for the new voluntary British Standards to support design and manufacture of products compliant with the ESRs, particularly for SMEs which have limited resources and testing capability. Some respondents recognised the opportunity for new standards to reflect modern domestic hazards and the ability to update standards more quickly than legislation. Respondents said that it would be challenging to implement the new approach until these standards are ready. A handful of respondents expressed concern that moving to voluntary standards would reduce fire safety and prefer statutory, mandatory testing.

Question 8: Do you agree with approach proposed by the hierarchy?

39) Many responses supported the principle of reducing CFRs and stated that businesses are already voluntarily taking steps to design out CFRs where possible, mentioning adherence to voluntary environmental and health industry standards such as Oeko Tex and DZHC.

40) A number of responses said the success of the hierarchy would depend on the new standards and the agreed level of ignition resistance and whether polyurethane foam will always need to contain CFRs, along with a clear determination of what is defined as ‘inherently flame retardant’.

41) Many respondents felt that the proposed hierarchy is not sufficiently robust and does not go far enough to achieve its aims of encouraging a reduction in the use of CFRs. Many stated that cost should not be allowed as a determining factor when manufacturers consider what is ‘practicable’, as most businesses will take the cheapest route to manufacture products at competitive prices, which means using CFRs.

42) Respondents raised concerns about creating an uneven playing field, where progressive businesses will take action to reduce CFRs but will struggle to compete with lower cost products that use CFRs. Respondents mentioned that inherently flame retardant materials may not be as fire safe as it is assumed, or provide sufficient comfort, and are not readily available which may limit consumer choice and innovation.

43) A number of stakeholders felt that CFRs should not be treated as one homogenous group and should be ranked or disaggregated and considered within groups or sub-groups. They stated that some CFRs (e.g. graphite) are shown to be effective and non-harmful to human-heath and the environment, while other groups can be restricted, preventing regrettable substitutions. Some respondents said that the hierarchy discourages innovation in CFR technologies to find better and safer solutions.

44) Many responses cited the ambiguity of terms such as ‘inherently flame retardant materials’ and ‘chemical flame retardants’, especially in respect of materials which are marketed as inherently flame retardant when they contain reactive CFRs covalently bonded to material fibres.

45) Several respondents expressed the view that the hierarchy would create a disproportionate administrative burden, particularly on SMEs, and would need to be supported by clear guidance.

46) A number of respondents felt that a quantifiable reduction target for CFRs should be specified and that the Government should provide a clear route map for the phasing out of CFRs within an agreed timeframe.

47) One respondent commented that the approach proposed by the hierarchy could be carried out at company level rather than product level, and others felt that this information should be provided on company websites and shared with importers and further suppliers to increase transparency and inform consumer purchasing decisions.

Question 9: Do you agree testing a composite or representative sample of the final item is the correct approach to assess the safety of upholstered products?

48) Many responses were supportive of the proposal to test the final item, or a representative sample, on the basis that it improves fire safety by addressing the hazard as it appears in the home. It also takes account of flammable components near the cover and how materials interact with one another in the event of a fire. They agreed this approach would enable a reduction in the use of CFRs, and that it would give them greater flexibility to innovate and design better flame-retardant solutions into products. Some respondents highlighted that the industry is familiar with final-item and composite testing already, citing existing standards such as BS 7177 and EN1021.

49) Some responses asserted that having to make a second product for testing purposes would be cost prohibitive for bespoke furniture, and they do not benefit from the research and development facilities that large businesses do. Respondents suggested that for bespoke furniture there will need to be a continuation of component testing within the industry.

50) Respondents offering ‘any fabric, any frame’ ranges challenged the proposal given the impact of testing each variable in its final form (or a representative sample thereof), which will likely lead to a potential reduction in consumer choice and/or significant price increases.

51) Respondents highlighted the limited testing capacity in the UK for full-scale final product testing, and the costs associated with it, while others raised concerns about the waste and environmental issues associated with test samples and the additional storage and transportation costs they would incur.

Theme 3 – Information provision (product labelling and technical documentation)

Relevant consultation questions and summary of responses

Question 10: Do you agree with the labelling proposals, including the requirement to list chemical flame retardants on the label. If not, please explain and provide any evidence.

52) While the majority of respondents supported the labelling proposals, some respondents raised concerns about the difficulty in obtaining information about CFRs from suppliers, what constituted a CFR, how the information should be presented on the label and whether consumers would understand the information.

53) A few respondents discussed the cost to produce the label and the impact on product development times. A number of businesses suggested more than one label per product for different types of information, and it was also proposed that components should be labelled separately for CFRs to support recycling and waste disposal.

54) A number of respondents were in favour of including an option for digital labelling via QR codes or for aligning with the EU’s plans to implement Digital Product Passports.

Question 11: Do you agree with the suggested contents of the technical file? Please include evidence to support the inclusion of further elements, or removal of elements included in proposals.

55) It was stated that the proposed technical file would increase administrative burdens, particularly for SMEs, re-upholsterers and manufacturers of bespoke products. Some responses suggested that elements of the required information would be difficult to obtain from the supply chain, especially where components are not manufactured in the UK. Some stakeholders felt that the technical file information should be held on the manufacturer’s website, but acknowledged the challenge in maintaining accurate information, while others, felt that the information should be held in an online database maintained by government.

56) Other suggestions were for maintaining technical files for longer than 10 years, given the average lifespan on products in scope, such as sofas, and that technical files should be made available to waste managers to support appropriate disposal at end of life. A number of respondents suggested the technical file should apply to a ‘family’ of products, rather than each individual variation.

Question 14: Do you agree with the proposal to require product labelling information to be included in online product listings?

57) Many stakeholders highlighted the challenge of enforcement of products sold via online marketplaces. It was suggested that the proposed requirement to provide information should also extend to mobile apps as well as second-hand listing sites and social media platforms and some stakeholders suggested that ‘web page’ needed to be defined. Some felt that the requirement should only apply to larger businesses selling online, and for re-upholsterers that the requirement should apply to new products only to enable older products that do not bear a fire label to be sold online.

58) A number of large businesses stated that the date of manufacture and batch numbers should not be required for online listings as this information is not known when products are listed online. Some respondents mentioned that maintaining the information across all online platforms could be onerous.

Theme 4 – Re-upholstery and second-hand

Relevant consultation questions and summary of responses

Question 12: Do you agree with proposals for a re-upholstery permanent label? Please provide evidence to support any suggested changes.

59) The majority of respondents felt that the requirement to label the product once re-upholstered should be supported by obligations on material suppliers to provide information in respect of the materials used. Some stakeholders suggested a list of CFRs on the re-upholstery permanent label to support a circular economy and waste disposal, while others suggested the label should indicate where the re-upholstered product does not contain CFRs, as well as where it does.

60) A minority of stakeholders said that re-attaching the product’s original permanent label following re-upholstery was not relevant because it may no longer reflect the composition of the re-upholstered product.

General comments on re-upholstery

61) The majority of re-upholsterers did not agree with the proposals for the supply of added upholstery in the course of re-upholstering or repairing a product. They oppose the ESR for foam fillings when unmodified foam could be protected by the use of inherently fire-resistant barrier materials, and suggested an exemption for natural materials. A number of others felt that all filling materials should meet an ESR, not just foam. A minority of stakeholders disagreed with the proposal for materials being supplied by the customer being out of scope.

62) Respondents felt that the requirement to retain evidence for 10 years of component testing on added upholstery is a disproportionate burden on small businesses. Respondents said that the responsibility to conformity assess added upholstery should be borne by material suppliers.

63) A number of stakeholders requested clarity on the definition of re-upholstery, and some respondents said that repairs under warranty on newly supplied products should not be caught by the obligations on re-upholsterers. Some stakeholders have suggested that ‘Right to Repair’ legislation should apply to upholstered furniture to support the safe re-upholstery of upholstered products.

Question 13: Do these proposals strike the right balance in facilitating the second-hand market and ensuring that only safe products are supplied?

64) Some small and micro businesses expressed concern that they will lose a significant proportion of their business if they are no longer able to continue re-upholstering products to sell, if those products are required to bear an original permanent label. Vintage products originally manufactured between 1950 and 1980 would not be permitted for sale on the second-hand market leading to good quality furniture ending up in landfill unnecessarily and it was said this would undermine broader efforts to promote product circularity, despite a growing trend in upcycling and resale. One respondent highlighted that this could create a furniture black market.

65) Other respondents felt that placing products on the market without testing them created a fire risk and that no consideration was given to the potential fire risk created by stain treatments that may have been applied in the home, while some felt the proposed approach would ensure fire safety and access to furniture during a cost-of-living crisis.

Theme 5 – Implementation, enforcement and statutory review

Relevant consultation questions and summary of responses

Question 1: Does your organisation require a transitional period, and do you have any comments on the period proposed?

66) Some respondents supported the proposed 18-month transitional period, while others stated that the proposed transitional period is too short and suggested a 2-to-3-year transitional period in order to manage existing stock, re-design products, adopt a new testing regime and conformity assessment process, develop technical documentation and to take account of test lab capacity and accreditation to the new standards.

67) Many respondents said that the transitional period should not begin until the new British Standards have been published and designated to allow stakeholders sufficient time to develop products and adapt approaches in line with the new standards. Others said delays in developing the new standards would delay the implementation of the new approach and the benefits it would bring, particularly in the case of reducing CFRs.

Question 15: Do you agree with the proposal to extend the period for instituting legal proceedings from 6 to 12 months?

68) While most respondents agreed with the proposal, some suggested increasing the period for instituting legal proceedings to 3 years, with it beginning when an offence is discovered (rather than when the offence was committed) in line with the Toys (Safety) Regulations 2011. A few respondents raised concerns about the limited resources in local authorities to robustly enforce the regulations. Some asked for clarity on what ‘when an offence was committed’ and ‘instituting legal proceedings’ mean.

Question 16: Do you have any comments on the proposal for a 5-year review clause?

69) The majority of respondents supported the proposal for a 5-year review clause, however a range of respondents suggested the review take place at the end of the transitional period and some respondents asked for continuous monitoring and evaluation including a review after 3 years. Some respondents suggested aligning the review with a study being conducted on the occupational exposure of re-upholsterers to CFRs.

Theme 6 – Impacts

Relevant consultation question and summary of responses

Question 17: Do you have any comments on the detail of the impact assessment? Please provide any evidence or data that should be considered alongside the figures outlined.

70) Many respondents agreed that testing costs were difficult to estimate without the new standards in place, but felt that costs associated with final item and representative sample testing were significantly underestimated, especially for bespoke products and made-to-order ranges if all combinations need to be tested. Linked to final item testing, comments were made about the potential saving from reducing the use of CFRs and the impact on waste infrastructure.

71) Some respondents stated that the estimated familiarisation and labelling costs were too low, and a few respondents highlighted that the cost of purchasing standards and keeping them up to date has not been reflected in the impact assessment.

72) The majority of re-upholstery respondents stated that the impact assessment does not address a potential loss of business if they cannot re-upholster and resell furniture that does not contain an original permanent label, while SMEs expressed concerns about the cost of meeting additional requirements.

73) Respondents also pointed out that the cost of test lab accreditation has not been considered nor has the impact, in terms of cost, time and logistics, that this will have on businesses using their services.

74) Some respondents stated that the proposed new approach represented a net benefit in terms of fire safety, though this was difficult to monetise.

List of consultation respondents

Businesses

- 4 Seasons Outdoor UK Ltd

- 888 Designs

- A Hollingshead Upholstery

- A P S Upholstery

- A Share and Sons Ltd

- Airsprung Beds

- Alex Sherman

- Alice Kiltie Upholstery

- Altfield Ltd

- Altrium Vintage

- Amandas Treasures

- APM

- B&A Quilting UK Ltd

- Baby Barn Pram & Nursery Centre Ltd

- Babyco

- BabyStyle UK Ltd

- Bailey Ceilings Ltd

- Bebecar

- Becca Robins Upholstery

- Bethie Tricks

- Birtkitt Hill & Black

- Bluebird Upholstery

- Bolton Consultancy

- Box Upholstery

- Bristol Upholstery Collective

- British Baby Box

- Bubblebum UK Ltd

- Bugaboo International B.V.

- By Anna Elizabeth

- By Tumbisha

- Carezza Design Ltd

- Carpenter Ltd

- Charles Of Lloyd

- Cheltenham Upholstery

- Clarkson Coatings Ltd

- Clayhills Upholstery

- Clueit Webb Interiors Ltd

- Coakley & Cox Ltd

- Comfortex Ltd

- community playthings

- Consciously creative

- COSATTO Ltd

- Covercraft Upholstery

- Craft Upholsterer

- Crafted Upholstery

- CuddleCo

- Cybex Gmbh

- Dan-Foam ApS

- Delyth Upholstery

- Design Dispensary

- Design Marque Consulting Design

- Dexta Moors Ltd

- DG Product Safety

- Dorel UK

- Dorking upholstery studio

- Dreams Ltd

- Dream-tiques

- E.M. Makes

- Edge of the Wood Upholstery

- Edge Upholstery

- Edwina Boase Interiors

- Elisa Bespoke Interiors

- Ella Doran Design Ltd

- Embrace Bespoke Upholstery & Design

- Emma Stewart Interiors Ltd

- Evolve Interiors Studio

- fabric & finery Helensburgh

- Facelift Interiors

- Fama Sofas

- Fermob

- Finch and Toad Upholstery

- Fine Bedding Company

- Fledgling Upholsterer

- Floral Chicken (Stuart Townsend Ltd)

- Formulated Polymer Products Ltd

- Freeman Studio

- French-Brooks Interiors Ltd

- FSN UK Ltd

- Fully Re-Covered Bespoke Upholstery

- Funky Footstools UK

- Gabrielle Ara Upholstery

- Gathered UK

- Georgia Bosson Studio

- Glebe house vintage

- Greater Manchester Hazards Centre

- Green Sheep Group

- Green Textile Consultants Ltd

- Guy designs consultancy Ltd

- H & C Whitehead Ltd

- H Dawson

- Hair in the Chair

- Hart Upholstery

- Hauck UK Ltd

- Hayward Studio Upholstery / Shoreditch

- Hazeldean Upholstery & Soft Furnishings

- Hedvig Upholstery

- Helene Marie Design

- Hendron & Co Upholstery

- Hestia Upholstery

- Highgrove Beds Ltd

- Hillside Upholstery

- Hlalgarden upholstery

- Houxupholstery

- Ickle Bubba

- IKEA

- In Recovery Upholstery

- Individual upholsterer

- Innerpiece upholstery

- Interior Design Declares

- Interior Folk

- Ivyâs Girl

- JE Ekornes

- Joanne Cole Upholstery

- John Cotton Group Ltd

- John Hatch Upholstery & Interiors

- John Lewis

- JPS purchasing

- Katherine Regan Designs

- Kettler GB Ltd

- Kinder Design Ltd

- Kirsty Lockwood Furnishings

- Kub Products Ltd

- Kyoto

- Latexco NV

- Legacy Retrims

- Lorna Smith Interiors

- Lucy and the machine

- Lynwen Brown Upholstery

- Macnaughton Holdings Ltd

- Madderdyer Upholstery

- Mamas and Papas

- Materialise Interiors

- MB Textiles Ltd

- MiCala Upholstery

- Mick Sheridan Upholstery

- Miles GmbH

- Mobus Fabrics

- Modus furniture

- Moooi UK

- Newell Brands

- Next Ltd

- Nicola Parkes Upholstery

- Nuby-UK LLP

- Oliver Bonas

- One Nice Thing Ltd

- Oxford Upholstery

- Oxygen Upholstery

- Palava

- Panaz

- Parker & Gibbs Ltd

- Peg Perego

- Peter Fournel Antique Restoration and Upholstery

- Polly Granville

- PollyB Bespoke Ltd

- PW Greenhalgh Finishing Ltd

- R Fraser Upholstery

- Rachael South Upholstery

- Rapture & Wright

- Recticel

- Refabrikate

- Relish

- Robert Lines Upholsterers Ltd

- Room to Bloom

- Ross Langley Bespoke Furniture

- S. Ross & Co Ltd

- Sainsburys

- Sally Ross Richmond

- Sarah Jane Hemsley Upholstery

- Sarah Parry Design

- Savy Living

- Saxon Furniture Ltd

- Sealy UK Ltd

- Shnuggle Ltd

- Shoreditch Design

- Silentnight

- Silver Cross (UK) Ltd

- Simba Sleep

- Siren Furniture Ltd

- Sleepezee

- Smith And British

- Sonnaz Ltd

- Sophie Carter Upholstery

- Sparky Leather

- Spring Upholstery Brighton

- Square Two Furniture

- St Albans Upholstery School and Studio

- Steelcase (Southeast)

- Sterling Furniture Group Ltd

- Stokke AS

- Straw and Order Ltd Upholsterer

- Studio Stanway

- Studio52

- Stuhl Upholstery

- Sturgess and Sturgess

- Sussex Upholstery

- TCM Living

- Team Tex (UK) Ltd

- TexChem

- The Belfield Group

- The Chair Dr

- The Ergobaby Carrier

- The Footstool Gallery

- The Open House Design Ltd

- The Orangery

- The Polster Project

- The Recovery Room

- The Salvaged Woodshop

- The Traditional Upholstery Workshop

- The Upholsteress

- Thistledown Upholstery and Soft Furnishing

- Thompson Clarke Interiors

- Thrive International LLC

- Tigerlily Upholstery

- Tin House Studio LLP

- Trent Upholsteries Ltd

- Tresithick Upholstery Training

- Twojays Corner Antiques

- Unique Bespoke Upholstery

- Unseen Icons

- Upholstered Furniture Action Council

- Upholstery Bureau

- Vantage Capital Markets

- The Project Group

- Victoria Turner Upholstery

- Vintique Upholstery

- Vita Cellular Foam UK

- VM Furnishing

- W J Cox and Son

- We Could Be Kings Ltd

- Whitehead Designs Ltd

- Willow interiors

- Willow Upholstery

- Yorke Upholstery & Interiors

- Zoe Knight Interiors

Fire Services

- Fire Sector Federation

- Institution of Fire Engineers

- London Fire Brigade

- National Fire Chiefs Council

- Warwickshire Fire and Rescue Service

Test Houses

- Consumer Product Safety Advice Ltd

- Eurofins MTS Consumer Product Testing UK Ltd

- FIRA International Ltd

- Fire Protection Association

- SATRA Technology

Trade Associations and membership organisations

- Association of Master Upholsterers and Soft Furnishers

- Baby Products Association

- BIFMA

- British Furniture Confederation

- British Furniture Manufacturers Association

- British Retail Consortium

- BSEF – The International Bromine Council

- European Furniture Industries Confederation

- EUROPUR

- Furniture Industry Research Association (FIRA)

- FRETWORK

- Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association

- Leisure & Outdoor Furniture Association Ltd

- Long Eaton Guild of Furniture Makers

- Long Eaton Chamber of Trade

- National Bed Federation

- Pinfa, a Sector Group of Cefic

- Polyurethane Foam Association

- The Worshipful Company of Upholders

Trading Standards and Local Authorities

- Ards and North Down Borough Council

- Buckinghamshire and Surrey Trading Standards

- East Renfrewshire Council, Environment Department

- EETSA Regional Product Safety Group

- Environmental Health Northern Ireland

- Hampshire County Council

- Hertfordshire County Council

- Kent County Council Trading Standards

- Kirklees Council

- Leicestershire County Council

- Suffolk Trading Standards

- Telford Trading Standards

- Trading Standards Southeast Ltd

- West Yorkshire Trading Standards

Academics, Charities and Non-profits

- Blue Patch

- Cancer Prevention & Education Society

- Chartered Institution of Waste Management

- Chartered Trading Standards Institute

- Chem Trust

- Eco-Chair

- Fidra

- Furniture Recycling Group Ltd

- Green Science Policy Institute

- National Trust

- RoSPA

- Scottish Community Safety Network

- UKAS

- University of Dayton Research Institute

- Wales Safer Communities Network

- Whale and Dolphin Conservation

Trade Union

- Fire Brigades Union

Others

- Individuals (258)

- Unknown Business (1)