Chapter 1: Background and summary of proposals

Updated 7 July 2021

1. This chapter considers pension scheme trustees’ duties to consider climate change and the likelihood that climate change is a financially material risk, as well as an opportunity, for pension schemes. It summarises government work to date on pension schemes and climate change, and the actions taken by trustees so far.

2. The background to the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) is then covered, and we explain how reporting in line with the TCFD recommendations will improve both the quality of governance and the level of action on managing climate risk. This chapter also covers the benefits of trustees reporting on the alignment of the scheme’s investments with the ambitions on limiting the global average temperature increase set out in the Paris Agreement.

3. The chapter concludes with a summary of our proposals, which are explained in more detail in the rest of the consultation document.

Trustees’ duties to consider climate change

4. The Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group (PCRIG) – a group with representation from all quarters of industry, civil society and government convened to provide guidance for trustees of pension schemes on integrating climate-related risk assessment and management into decision-making and reporting – have highlighted that all pension schemes face climate-related risks irrespective of the way they invest or the estimated duration of liabilities:

All pension schemes are exposed to climate-related risks, whether investment strategies and mandates are active or passive, pooled or segregated, growth or matching, or have long or short time horizons. Many schemes are also supported by employers or sponsors whose financial positions and prospects are dependent on current and future developments in relation to climate change.[footnote 1]

5. There is evidence to suggest that we are currently on track to see 3°C of warming by the end of the century[footnote 2]. However, recent research by the International Monetary Fund has specifically identified that stock prices do not reflect future climate risk:

a sudden shift in investors’ perception of this future risk could lead to a drop in asset values, generating a ripple effect on investor portfolios and financial institutions’ balance sheets.[footnote 3]

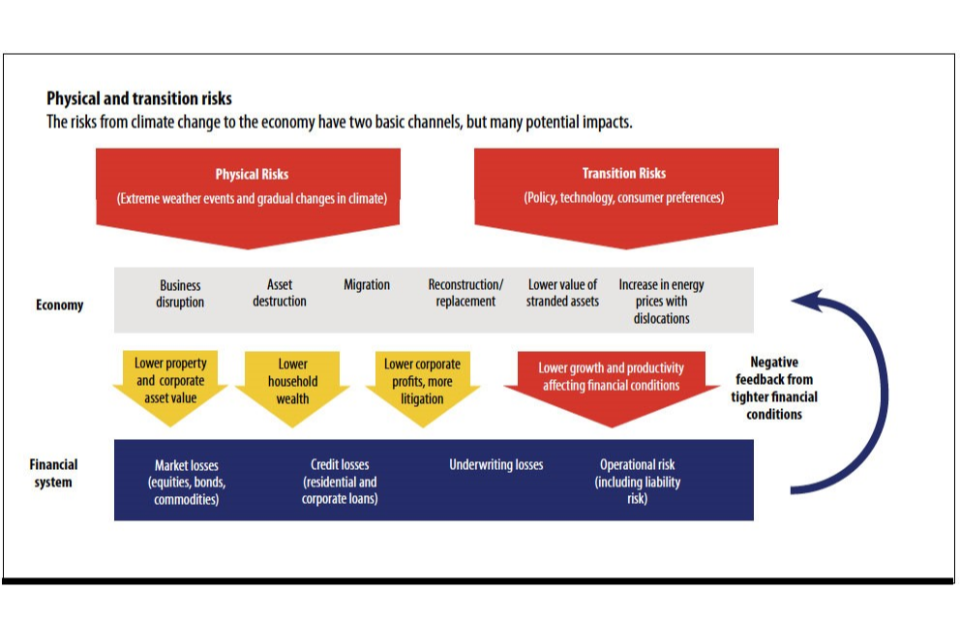

6. Emerging evidence also suggests that some assets are in the process of being significantly repriced as their transition or physical risk is recognised[footnote 4]. The mechanisms by which climate change risk affects the economy and in turn the financial system, with feedback effects for the economy, are set out schematically below[footnote 5].

Figure 1: Climate change affects the financial system through two main channels: physical risks and transition risks

Phyisical and transition risks on the financial system.

7. The financial analysis relied on by the market to determine valuations is also often based on the extrapolation of short-term cash flow estimates, so longer-term risks are not necessarily priced into the market[footnote 6].

8. These long-term risks come in two distinct forms for most financial firms: physical risks and transition risks.

- physical risks are those that pertain to the physical impacts that climate change is already bringing and will continue to bring in the event of a certain level of global average temperature rise (global warming). These include risks such as the rise in sea levels, with impacts such as flooded industrial sites and mass migration, as well as phenomena such as increased rate of extreme weather events which threaten physical assets and disrupt supply chains

- transition risks are less about ‘what would happen in the event climate change is not fully addressed’ and more about the risks associated with action to tackle climate change. As we seek to realign our economic system towards low-carbon, climate-resilient solutions, what regulations, behavioural changes, structural readjustment will take place and how will that affect current and future investments? Such risks include the future change in the energy mix on which the world depends or new, climate-conscious consumer trends

9. But this is not to say that the risks are exclusively longer term – market shocks are very likely in response to inevitable regulatory policy interventions[footnote 7] and we know that, in order to meet the goal of the Paris Agreement to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, annual global emissions must start to reduce with a significant annual rate of reduction thereafter[footnote 8].

10. Gambling on an inadequate response from policy makers and regulators offers trustees no reassurance either. Companies and investors face increased cost and uncertainty from both a ‘disorderly’ low-carbon transition and the likely accompanying – considerable – physical risks.

11. Trustees have a duty to act in the best interests of pension scheme beneficiaries[footnote 9], as well as duties to act prudently, conscientiously and with upmost good faith, seeking advice where needed. Given the nature and likely materiality of the risks posed by climate change, trustees’ fiduciary duties require them to take it into account. The PCRIG ‘unpacks’ this duty [footnote 10] as follows:

- exercising investment powers for their proper purpose – trustees must exercise their investment powers for the purposes for which they were given. Trustees should consider how properly taking into account climate-related risks and opportunities will assist in delivering on the purpose of the trust (namely for the provision of pension benefits)

- taking account of material financial factors – trustees should always take into account any relevant matters which are financially material to their investment decision-making, whatever their source. This includes whether a particular factor is likely to contribute positively or negatively to anticipated returns, or will increase or reduce risk. Their duties are not limited to “traditional” factors such as interest rate, exchange rate, or inflation risk

- acting in accordance with the ‘prudent person’ principle – trustee investment powers must be exercised with the care, skill and diligence that “a prudent person would exercise when dealing with investments for someone else for whom they feel morally bound to provide”. In line with the prudent person principle, trustees must consider likely future climate scenarios, how these may impact their investments and what a prudent course of action might be as part of their scheme’s risk management framework

DWP and pension scheme activity on climate change

The Law Commission’s reports

12. The Kay Review of UK Equity Markets and Long-Term Decision Making[footnote 11], published in 2012 identified concerns about how the fiduciary duties described in paragraph 11 above were interpreted in the context of investment. It therefore recommended that the Law Commission should review the legal concept of fiduciary duties as applied to investment, to address uncertainties and misunderstandings on the part of trustees and their advisers. The Law Commission’s report[footnote 12], published in July 2014, concluded that trustees should take into account factors which are financially material to the performance of an investment, whatever their source.

13. Following guidance issued by The Pensions Regulator (TPR) in relation to managing Defined Contribution (DC) schemes (also known as money purchase benefits)[footnote 13] and funding Defined Benefit (DB) schemes[footnote 14], and a further Law Commission report on pension funds and social investment[footnote 15], government concluded that a legislative change was required to put the need to consider the full range of financially material matters – including climate change – beyond doubt[footnote 16].

Clarifying and strengthening trustees’ investment duties

14. In June 2018 we made proposals[footnote 17] for amendments to the Statement of Investment Principles (SIP) which must be prepared by most schemes with 100+ members and to the default SIP, which – subject to a number of exceptions – must be prepared by trustees of schemes with 2+ members offering money purchase benefits and a default arrangement.

15. This legislation[footnote 18] was made in September 2018 with some measures coming into force on 1 October 2019 and the remainder[footnote 19] coming into force on 1 October 2020. It includes measures to:

- require consideration of financially material risks and opportunities whatever their source, by extending the content of SIPs

- enable comparison of the quality of SIPs and to learn from others, by requiring publication

- minimise the risk of requirements being met with rarely-reviewed, generic ‘box ticking’ documents by requiring trustees of schemes offering money purchase benefits (broadly, DC and hybrid schemes) to prepare and publish an implementation statement reporting on how, and the extent to which, the SIP has been followed during the year

- facilitate scrutiny by engaged members by including a link to SIP and implementation statement in the annual benefit statement sent to members

Other pensions legislation

16. Two more pieces of legislation which are relevant to climate change risk have subsequently been brought into force since the regulations described above, in accordance with European Union legislation which became due for transposition before the UK left the EU.

17. Regulations which came into force in January 2019[footnote 20] require trustees of pension schemes, subject to some exceptions, to establish and operate an effective system of governance including internal controls. They also tasked TPR with the duty to issue a Code of Practice in relation to this duty.

18. The forthcoming Code must be taken into account by a court or tribunal when determining whether the legal requirements have been met[footnote 21]. It requires, amongst other things, trustees to carry out a risk assessment within 12 months of the end of the next scheme year, to begin after TPR issue the Code of Practice. This should include whether and how the trustees assess risks relating to climate change, the use of resources and the environment, and risks relating to the depreciation of assets as a result of regulatory change.

19. Separately, regulations made in May 2019[footnote 22] required defined benefit schemes to make their SIP publicly available on a website by 1 October 2020, and made a number of additions to the SIP to be incorporated by the same date. These include the requirement to explain how their arrangements with asset managers incentivise alignment of the investment strategy with the trustees’ SIP and to make decisions based on medium to long-term performance of investee firms. Finally, the regulations introduced a more limited published implementation statement for defined benefit schemes, covering only monitoring and engagement with issuers, investment managers, co-investors and stakeholders, to be made publicly available on a website by 1 October 2021.

Pension scheme trustees’ response

20. Reactions to the regulations have been widely analysed and reported by a range of market participants. In September 2019, in the run up to the legislation coming into force, the consultants Hymans Robertson[footnote 23] found that 96% of trustees were prepared for the regulations, despite 84% of them facing some challenges.

21. There have been other more mixed responses. The pensions law firm Sackers[footnote 24] in August 2019 found that 85% of surveyed trustees had already updated, or would update, their SIP for compliance purposes, but that only 13% had made or intended to make material changes to their investments. The Society of Pensions Professionals found[footnote 25] that for 38% of its members, the approach taken by most of their clients was tick box only, although it also found that 57% thought their clients had a genuine interest in ESG but had simply not changed their portfolio yet.

22. Collectively this research suggests that advised pension scheme trustees are complying with the letter of the law but taking their time on making decisive changes to strategy. Notably, Hymans Robertson also found that 70% of trustees were supportive of the regulations, with 27% strongly supportive, while only 7% oppose them.

23. More difficulty has been found in the smallest defined contribution schemes. TPR’s DC schemes survey[footnote 26], carried out ahead of the regulations coming into force, found that only 21% of schemes took climate change into account when formulating their investment strategies and approaches, with the most common reasons being that it’s “not relevant to our scheme” or that trustees were “not required to do this”.

24. TPR’s research suggests that non-compliance appear to be highest in the smallest pension schemes.

Responses to Ministerial letters

25. In October 2019 the Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion, Guy Opperman MP, wrote to 40 of the largest defined benefit pension schemes and 10 of the largest defined contribution pension schemes by assets.

26. The letters (see Annex 1 for full text) asked pension schemes a number of questions including:

- what substantive changes have you made to your investment strategy in the last 3 years to take account of ESG and climate change and when have you made them?

- does your scheme make climate disclosures in line with the TCFD framework? What aspects of the TCFD recommendations do you meet? Do you plan to meet more in the next 12 months?

- are there further specific actions government might take to impress upon pension schemes – or others – the materiality of climate change risk and how it might be minimised. If so, what are those actions?

27. Responses, summarised below, showed significant progress in the actions taken by larger pension schemes, but indicated a need for progress in other areas with low take up of the Taskforce for Climate-related Financial Disclosure (TCFD) recommendations, even amongst the largest pension schemes.

Figure 2: Substantive changes made to investment strategy in the last 3 years to take account of ESG and climate change

| TCFD recommendation | |

|---|---|

| Best practice | 34% |

| Good practice | 37% |

| Doing the minimum | 29% |

Best practice – close monitoring of investment managers and changing manager where appropriate, and changes in asset allocation in more than one sector – for example, corporate bonds, property or infrastructure as well as equities.

Good practice – evidence of climate risk being a real consideration in appointment, retention and replacement of managers; ongoing monitoring of managers and changes of manager where appropriate; and changes in asset allocation in one sector.

Doing the minimum – some consideration of climate or other environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks; consideration, or conversations with consultants and/or managers, before making appointments, but no evidence of actual changes in investment decisions.

Figure 3: Making climate disclosures in line with the TCFD recommendations

| TCFD recommendation | |

|---|---|

| Best practice | 13% |

| Good practice | 29% |

| Doing the minimum | 58% |

Best practice – carrying out whole of TCFD recommendations now, or some aspects of TCFD recommendations now with clear intention to be meeting all in next year.

Good practice – some evidence of carrying out some aspects of TCFD recommendations now or evidenced a clear intention to begin reporting in the next year.

Doing the minimum – no evidence of schemes carrying out disclosures in line with TCFD recommendations, and no disclosures planned in next year.

Further specific actions government might take

28. In response to the question on further specific actions government might take to highlight the materiality of climate change risk and how it might be minimised, two key themes were most frequently identified:

- the need for industry guidance and direction from the government – we have contributed to this through our participation in the PCRIG

- the need for mandatory TCFD reporting – this is the key theme of this consultation. 34% of the schemes that responded, called, unprompted, for mandatory TCFD reporting. A further 29% of schemes wanted to see further government action in this space but did not explicitly mention TCFD recommendations

Wider action on greening finance

The TCFD recommendations

29. The TCFD is a global, private sector led group assembled in December 2015 at the instigation of the international Financial Stability Board (FSB), an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system, which was then chaired by Mark Carney. Following extensive public consultation, they published their recommended disclosures in June 2017[footnote 27].

30. The recommendations were designed to be adoptable by all organisations, including both non-financial groups and the financial sector, from asset managers to asset owners, including banks, insurers and pension schemes. The TCFD designed the set of recommendations as a flexible framework for these organisations to produce decision-useful, forward-looking information on the financial impacts of climate change, which would accommodate continued rapid evolution in climate-related modelling, management and reporting.

31. The final report included 11 recommendations. These are split into Governance, Strategy, Risk Management and Metrics and Targets.

Figure 4: Core elements of recommended climate-related financial disclosures

Core elements of recommended climate-related financial disclosures: governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets

Governance

The organisation’s governance around climate-related risks and opportunities.

Strategy

The actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the organisation’s businesses, strategy and financial planning.

Risk Management

The processes used by the organisation to identify, assess and manage climate-related risks.

Metrics and Targets

The metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities.

The Green Finance strategy

32. Following the report of the UK Government-commissioned Green Finance Taskforce[footnote 28] in March 2018, the government’s Green Finance Strategy[footnote 29] was published in July 2019. This set out a range of actions in relation: to mainstreaming climate and environmental factors as a strategic imperative; to mobilise private finance for clean and resilient growth; and to cement the UK’s leadership in green finance.

33. Amongst the announcements were:

- the government’s expectation for all listed companies and large asset owners to disclose in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022

- the creation of a joint taskforce with UK regulators, chaired by government, which will examine the most effective way to approach disclosure

- the establishment of the PCRIG[footnote 30] as an industry group to develop TCFD guidance for trustees of pension schemes. This group published comprehensive non-statutory guidance for consultation in March 2020. The consultation received 40 responses and has now closed. We anticipate that final guidance will be published at the end of 2020

34. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) has worked closely with other government departments and regulators, in the UK joint TCFD taskforce, chaired by Her Majesty’s (HM) Treasury. In bringing forward these proposals for legislation to achieve TCFD reporting by large pension schemes, DWP has aligned itself with direction across government.

Mandating TCFD-aligned disclosures

35. The evidence from the occupational pension sector, as well as nationally and internationally, is that now is an appropriate time to move towards mandatory TCFD-aligned disclosures, beginning with larger pension schemes.

36. In the occupational pension sector itself, responses to letters from the Minister for Pensions and Financial Inclusion referred to above demonstrate that the largest schemes are already taking action, with 71% of respondents going significantly beyond statutory minimums in their activity. But they also indicated the need for a nudge, with fewer than half of schemes making any TCFD-aligned disclosures or having plans to do so in the next 12 months. The PCRIG’s draft guidance has provided pension schemes with the guidance and direction to begin to take steps to report – now is the time to move towards legislation to embed the practice widely. This will also remove any ‘first mover’ disadvantages for schemes that have already taken action and will level the playing field.

37. Nationally, the Green Finance Taskforce called for the TCFD recommendations to be integrated throughout the existing UK corporate governance and reporting framework, and government’s Green Finance Strategy has set a clear expectation that disclosures will be made in line with the TCFD recommendations by large asset owners by 2022. The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) have already launched a consultation on the TCFD recommendations by UK premium listed issuers[footnote 31]. Due to the COVID-19 epidemic the consultation deadline has been extended to 1 October 2020 with a Policy Statement and final rules now expected early in 2021[footnote 32]. The FCA is also currently considering how best to enhance climate-related disclosures by FCA-regulated firms, in line with its Feedback Statement on climate change and green finance last October[footnote 33] (FS 19/6).

38. Internationally, the TCFD recommendations have become a key part of the UK Government’s focus and engagement with other signatories to the United Nations (UN) Framework Convention on Climate Change and the UN Climate Change COP26, which will take place in Glasgow in November 2021.

39. In his February 2020 speech “The Road to Glasgow”, Mark Carney, the then Governor of the Bank of England and the current Finance Adviser to the Prime Minister for COP26 set out government’s intention to develop pathways to determine the best approaches to making climate disclosure mandatory[footnote 34]. This consultation forms part of that work.

The Pension Schemes Bill

40. Building on the expectations set out in the Green Finance Strategy, government amendments were made to the Pension Schemes Bill during its passage through the House of Lords. It now[footnote 35] includes powers to make regulations:

- imposing requirements on scheme trustees with a view to securing that there is effective governance of the scheme with respect to the effects of climate change

- requiring information relating to the effects of climate change on the scheme to be published

- ensuring compliance with the requirements above

41. Ministers have made clear that the provisions are intended to allow governance processes and disclosures aligned with the TCFD recommendations to be mandated[footnote 36]. This consultation is about when and how schemes should be required to adopt these enhanced governance requirements and report in line with the TCFD recommendations.

42. Government also made clear during debates in the House of the Lords that the measures will not, and cannot, be used to direct pension scheme investment:

Let me be clear. This does not mean that it is for the government to direct schemes or set their investment strategies. The government never have directed pension scheme investment, and do not intend to. Our clear view is that the amendments do not permit us to do that.[footnote 37]

Baroness Stedman Scott, House of Lords Committee Stage, 26 February 2020

43. The measures can only be used with a view to securing that there is effective governance of schemes with respect to the effects of climate change and to require associated disclosures.

Benefits of the TCFD recommendations

44. In the “Road to Glasgow” speech referred to above, Mark Carney expanded on the advantages of the TCFD recommendations:

The TCFD has become the go-to standard for consistent, comparable and decision-useful and efficient information. It is comprehensive, encompassing recommendations on governance, strategy and risk management, as well as metrics and targets. And most importantly, it represents the best views of the private sector of what is decision useful, capturing the opinions of both the companies that must access finance and of the providers of capital from across the financial system.

The TCFD has widespread public backing from across the financial sector. Every major systemic bank, nine of the top ten asset managers, all the credit rating agencies, all major accounting firms and shareholder advisory firms back the TCFD.

45. TCFD-aligned disclosures offer the opportunity for trustees of occupational pension schemes to move away from the relatively high-level disclosures prescribed in the Statement of Investment Principles.

46. It permits them to demonstrate how the consideration of climate change risks and opportunities are integrated into the pension scheme’s entire decision-making apparatus.

47. Carrying out scenario analysis, reporting on appropriate metrics including greenhouse gas emissions, and setting appropriate targets, would provide valuable inputs which can inform a pension scheme’s strategy. It would also allow trustees to monitor and review progress, and, where they control investments, to make amendments to the investment strategy where necessary. Disclosing this information provides greater transparency to beneficiaries about how their money is being managed.

48. The flexible structure of the TCFD recommendations also allows trustees to continuously improve climate risk governance and reporting in the light of rapidly increasing data quality and completeness and emerging best practice.

49. Many aspects of the tools and data used for climate-related analysis are still in development, but investors can take substantive action now to address climate risk and to report on it as part of their duties to scheme members and beneficiaries. Whilst investment analysis is never a perfect science, there is already enough data, analysis and tools – real change is already happening when trustees and asset owners use that investor data to act.

50. Analysis by the Transition Pathway Initiative[footnote 38] reviewed 332 corporations worldwide in 16 business sectors and showed that:

- 26% reported on climate scenario planning

- 40% reported on climate risks and opportunities in strategy

- 62% reported on board responsibility for climate change

- 66% reported on processes to manage climate risks

- 70% set public targets of some duration, with 57% setting long-term targets

- 76% disclosed scope 1 and 2 emissions, with 61% disclosing scope 3 emissions

Challenges to adoption of the TCFD recommendations

51. We recognise that adoption of the TCFD recommendations is a journey. Our proposed policy has been developed with a range of challenges in mind. Challenges relating to data availability are also covered in chapter 3. Challenges around publication and explaining the results are addressed in chapter 4.

COVID-19

52. This consultation comes as the UK economy is still recovering from the severe disruption of the COVID-19 pandemic. government has recognised the distress caused to many sectors and individual businesses. But delaying decisive action on climate risk will only expose companies, trustees and pensions savers to potential turbulence in the future. It is vital we make our financial system more resilient as we look to build back better and greener

53. However, we need a proportionate approach. This is why, in our proposals, we are excluding smaller schemes, and are giving even the largest schemes a minimum of one year to prepare.

Discouraging ‘tick box’ disclosures

54. High quality TCFD reporting will represent an essential element of good scheme governance, regardless of a requirement to publish.

55. With that in mind, the proposals in this consultation do not seek to be simply another disclosure requirement. We propose that our policy, and our eventual regulations, will make clear that these changes concern governance decisions, and the disclosure requirements should instead be viewed as part of a wider, robust governance process.

Legal liability

56. During our informal stakeholder engagement, some trustees have raised a concern that expressing their best estimates of the effects of climate change on their pension schemes may give rise to legal risk, if those estimates subsequently turn out to be inaccurate.

57. The same standards will be expected of trustees in relation to estimates and disclosures about the effects of climate change, as are expected in relation to any other estimates and disclosures that trustees make about their pension scheme. Trustees are expected to comply with their existing duties under the Trust Deed and Rules for the particular pension scheme, under general trust law and under existing pensions legislation. First and foremost, they must act in accordance with their fiduciary duties towards pension scheme beneficiaries. This means acting in their best interests and carrying out their duties prudently, conscientiously and with the utmost good faith and taking advice where specialist input is needed, for example about investment decisions and applicable legislation.

58. When taking such advice, as with any professional advice, trustees need to be able to demonstrate that their advisers are properly qualified and ensure that they, as trustees, understand any advice they receive. Importantly, trustees do also need to be able to challenge and question professional advice to aid their understanding and be able to justify their reasons for following or not following it.

59. When drawing conclusions and making disclosures about the scheme’s climate change risks, trustees will be expected to weigh up competing factors, to take all relevant factors into account and to ignore irrelevant factors, and to reach a decision about what to disclose which is reasonable, and which meets the requirements of the legislation.

60. We cannot give trustees any general reassurances on compliance with these proposals around climate change. Any questions of trustee liability would depend heavily on the particular facts of the case and the eventual regulations and both statutory and non-statutory guidance. However, trustees would be supported by both statutory guidance – the proposed contents of which are covered in this consultation – and non-statutory guidance produced by the PCRIG. Moreover, trustees can help to mitigate legal liability risk by being transparent about the approach they have taken to aspects of TCFD reporting such as scenario analysis.

61. The expectation, as with other trustee decisions, would be that the exercise of trustees’ discretion and decision-making would be assessed based on the information and circumstances reasonably available at the relevant time. Trustees are expected to act in accordance with their legal duties and powers, but they are not expected to predict the future. However, a strength of the scenario analysis included within the proposals is that it allows trustees to carefully consider multiple different possible outcomes based on available data and information.

62. The usual rules would also apply in relation to exonerations and indemnities for trustees. For example, there might be provision in their Trust Deed and Rules exonerating them from personal liability in certain circumstances, although there will usually be ‘carve outs’ for where trustees have acted dishonestly or in bad faith. They may also benefit from an indemnity from the scheme employer, from the scheme’s assets or liabilities or from indemnity insurance, which could cover their liability in certain circumstances.

How trustees respond

63. Finally, we recognise the concerns of some pension scheme trustees that scenario analysis, or disclosure of greenhouse gas emissions or other metrics or targets, may lead to increased pressure for divestment of pension schemes from high carbon sectors.

64. As highlighted above, we recognise that the ultimate decision-making on climate change risk and opportunities are matters for trustees alone. The government’s changes to the law, as set out above, have sought to provide clarity to trustees that consideration of ESG factors, including climate change, is an appropriate and important part of their duties. This message has been further strengthened by the ambitious new Stewardship Code, which took effect from 1 January 2020[footnote 39].

65. The government sees stewardship of assets, including engagement with higher carbon firms and voting at Annual General Meetings (whether directly or via asset managers), as entirely legitimate responses to the climate risk revealed through TCFD-aligned disclosures.

66. Indeed, holding such assets places trustees in an influential position to steward firms towards lower-carbon business practices, which is why government advocates collaboration with business, as opposed to divestment, as the most effective means of holding companies to account on climate change. Government believes that selling assets to less engaged shareholders is likely to be counterproductive from a climate-risk mitigation perspective.

67. Whilst engaged members and civil society groups have an important role in facilitating scrutiny, these measures are not intended to give any support to campaign groups calling for blanket divestment from certain assets. Government continues to believe this would be the wrong approach – engagement with high-carbon companies, when done effectively, can reduce the climate risk to which the scheme is exposed. At the same time, stewarding these firms to set a plan for the transition can have a greater impact on climate change than simply selling assets to others who might not hold investee firms to account. Ultimately, Trustees have primacy in investment decisions; it is not for the government to direct trustees to sell or buy certain assets and these proposals do not create any expectation that schemes must divest or invest in a given way.

Paris alignment and “Implied temperature rise”

68. The Paris Agreement[footnote 40] includes a commitment to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels (Article 2.1(a)). The Agreement also aims to make financial flows consistent with low Green House Gas emissions and climate-resilient development (Article 2.1(c)). Finally, it states that in order to achieve the long-term temperature goal, global GHG emissions should peak as soon as possible, with rapid reduction thereafter in accordance with best available science (Article 4.1).

69. Disclosure in line with the TCFD recommendations discussed in this consultation provides information that could help assess transition risks and opportunities associated with a selected portfolio, fund, or investment strategy. And since these recommendations were introduced, there is also increasing interest from investors and businesses in the idea of ‘Paris alignment’. This may also be expressed as alignment with the transition to a ‘net zero’ economy.

70. One of the attractions of thinking about business and investment through the framing of Paris alignment or net zero is the focus on forward-looking assessment of potential contributions to global warming. This can provide valuable information about progress, or lack of progress, towards limiting the global average temperature rise.

71. The Paris Agreement, however, was not written specifically for investors or businesses. A certain amount of work is therefore necessary in order to translate what its commitments mean for them in practice. For example, a pension scheme’s ‘alignment’ will be dependent upon analysis of the underlying assets, their current emissions and their likely associated emissions trajectory, but different sectors and asset classes will face different challenges in relation to reducing emissions. These differences will need to be reflected in how they are assessed. In response to these challenges, a substantial amount of work is being undertaken by industry to review and assess the emerging approaches to measuring and reporting information on the position of their portfolios relative to the transition to the net zero carbon economy. This includes work by the TCFD, the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance[footnote 41], the COP26 Private Finance Hub and the Paris Aligned Investment Initiative coordinated by the Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change (IIGCC)[footnote 42].

Portfolio warming or implied temperature rise

72. One way of understanding and reporting progress towards Paris alignment which has gained traction within the financial sector is the idea of measuring ‘portfolio warming’ or the ‘implied temperature rise’ (ITR) of investment portfolios. This is also sometimes referred to as ‘degree warming’, ‘temperature score’, or the ‘portfolio warming potential’. The idea is that financial institutions can model the likely global average temperature rise above pre-industrial levels with which their holdings are consistent. The outcome of this modelling is a single metric, for example a portfolio may have an ITR of 3°C.

Benefits and challenges of measuring and reporting implied temperature rise

73. The government sees value in trustees of occupational pension schemes taking steps to understand the ITR of their portfolios and disclosing this publicly.

74. The process of undertaking the analysis to determine the ITR of their portfolios will help trustees to gain greater understanding of their associated climate risk and opportunities. For example, where a scheme’s ITR is found to be 4°C, its trustees can see that it is likely to be significantly affected by public policy measures aimed at limiting the global average temperature increase to well below 2°C. This information can be used by trustees to better inform pension scheme strategy. In this respect, the value of calculating the ITR is similar to the process of scenario analysis recommended by the TCFD recommendations.

75. We also see benefit in schemes reporting their ITR. ITR is a reasonably simple representation of a complex concept. Reporting the ITR will therefore provide scheme members with a manageable metric to understand the scheme’s current position in relation to addressing climate risk and we see future value in the ITR figure being reported to members in the Annual Benefit Statement. This is not to say that calculating an ITR is simple and we recognise that there would likely need to be explanation to accompany the reported value. However, the ITR figure itself is likely to be easy to understand and would provide useful information to accompany the scheme’s wider TCFD reporting. This would also be valuable for TPR as a way of understanding the climate risk exposure of the sector.

76. A further benefit of reporting an ITR is that it may drive better practice across the occupational pension sector. Trustees and their advisers would benefit from sight of other schemes’ reported ITR and this may stimulate improved climate-related policies and practices across the sector. As with disclosure of TCFD reports, public scrutiny has an important role to play in driving improvement.

77. One alternative way of reporting Paris alignment would be for schemes to simply state whether or not they are aligned with the Paris Agreement. However, this approach lacks some of the nuance of reporting an ITR and would provide less information to members, the sector and regulators about the extent to which schemes are exposed to climate risk. Furthermore, it may not incentivise trustees to move towards Paris alignment if a very large percentage of the sector reports as ‘not aligned’. Having pension schemes report their ITR will provide useful data and case studies which would aid trustees and policymakers in improving their response to climate risk.

78. However, in order for ITR to be an effective metric to assess risks and opportunities for pension schemes, there needs to be a reliable and effective methodology, or methodologies, to calculate it. It is important that financial institutions, including pension schemes, and their stakeholders are able to rely on the output of any methodology and to trust in its accuracy.

79. At present, the available methodologies for measuring ITR are not widely considered to be sufficient. Our engagement with stakeholders working in this area suggests that there are potential risks to accuracy and reliability caused by gaps in data and in the methodologies themselves. There is also a lack of consensus around the modelling, which could lead to very different ITRs being calculated for the same portfolio/assets. This uncertainty poses a risk to the success of any policy measure related to ITR.

80. However, a substantial amount of work is currently being undertaken to review and assess these methodologies measuring portfolio alignment, including ITR. This work is likely to lead to better understanding of the existing approaches and further developments in the sophistication of the tools available to trustees of pension schemes. It is likely, therefore, that best practice in this area will continue to develop over the course of the next 12 months.

Next steps

81. In light of the above likely benefits of measuring and reporting the ITR of portfolios, the government is minded to take steps to require that pension scheme trustees do this. However, our engagement with stakeholders suggests that the work currently being undertaken in this area will result in better methodologies which will be more useful for trustees. We are therefore not consulting on Paris alignment and ITR in this consultation but intend to do so in the near future. This future consultation may also include consideration of other ways of measuring and reporting Paris alignment.

82. The government is supportive of leaders in the occupational pension sector who are already exploring how they can take steps towards Paris alignment.

Summary of proposals

Scope and Timing

We propose that larger schemes and authorised master trusts should disclose on the timescale shown below.

| The condition | Governance requirement | Disclosure Requirements | Disclosure Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| If | Trustees must meet the climate governance requirements for | Trustees must publish a TCFD report | Trustees must include a link to the TCFD report from |

| On 1st scheme year to end on or after 1 June 2020, the scheme has assets ≥ £5 billion Or On 1 October 2021, the scheme is an authorised master trust Or On 1 October 2021 the scheme is an authorised scheme providing collective money purchase benefits |

Current scheme year from 1 October 2021 to end of that scheme year. And [unless scheme is no longer authorised, and assets are < £500 million] Next full scheme year to begin after 1 October 2021 to end of that scheme year. |

Within 7 months of the end of the scheme year which is underway on 1 October 2021, or by 31 December 2022 if earlier. And Within 7 months of the end of the next scheme year to begin after 1 October 2021, or by 31 December 2023 if earlier. |

The Annual Report and Accounts produced for that scheme year |

| On 1st scheme year to end on or after 1 June 2021, The scheme has net assets ≥ £1 billion |

Current scheme year from 1 October 2022 to end of that scheme year | Within 7 months of end of that scheme year, or by 31 December 2023 if earlier. | The Annual Report and Accounts produced for that scheme year |

The largest corporate schemes have highest governance and resource capacity, and they will have the capability to produce TCFD disclosures in the first instance. Authorised master trusts will be expected to have met minimum standards, and government policy is to maintain a level playing field between master trusts.

On an ongoing basis, we propose that where scheme assets exceed £1 billion at the end of a scheme year, the governance requirements – and the period on which trustees must report – commences from the period beginning with start of the next scheme year. Schemes would remain in scope until assets fall below £500 million at scheme year end. The requirements would apply to authorised master trusts and schemes offering collective money purchase benefits from the point of authorisation, and fall away from the point of de-authorisation.

We would take stock in 2024 and consult more widely again before extending to schemes with < £1 billion in assets, taking account both of the quality of climate risk governance and associated disclosures carried out to date, and the current and future costs of compliance.

TCFD Requirements

Regulations vs. Statutory Guidance

We propose that regulations require trustees to meet climate governance requirements which underpin the 11 recommendations of the TCFD, and to report on how they have done so.

Statutory guidance, which trustees must have regard to, will set out steps to meet and report on TCFD requirements.

Trustees must meet the standards required by the regulations. They can diverge from statutory guidance, but they would need to be able to explain why.

Metrics, Targets and Scenario Analysis

Trustees are dependent on data from other parts of the investment chain and their investments are in a range of jurisdictions. Therefore, initially, we propose that trustees should carry out scenario analysis, calculate metrics and report against trustee-set targets ‘as far as they are able’.

We recognise that the key for scenario analysis is a range of scenarios allowing trustees to analyse both transition and physical risk. We therefore propose to prescribe at least two scenarios, of which at least one must correspond to a global average temperature rise of 2°C or lower above pre-industrial levels. Other possible scenarios would be set out in statutory guidance to which trustees must have regard.

For metrics, we propose that trustees are required to obtain data from their asset managers and in turn from investee firms on emissions and other characteristics of their investments that they wish to quantify, ‘as far as they are able’. This acknowledges the difficulties that schemes might face in acquiring full data for their portfolio in which they are confident.

Trustees would then be required to calculate and publish at least one metric that they use to measure, monitor and manage the climate-related risks and opportunities of the scheme. This can be either emissions-based or non-emissions-based.

The metrics trustees will be required to calculate should be measures that quantify the effects of climate-related risks and opportunities on the scheme, or the governance of those risks and opportunities. We do not plan to prescribe particular metrics in regulation. Instead we propose that trustees will be able to select those metrics from a range presented in statutory guidance, with the aim of driving consistency across the sector.

Trustees must then set at least one target. This must be a target for one of the metrics that they choose to publish.

We propose that scenario analysis must be carried out, and appropriate metrics and targets set, at least once each scheme year. In addition, underlying data for metrics and targets are obtained and calculated, and performance against targets is measured, at least quarterly. All other climate governance requirements are ongoing for the schemes to which they apply from the coming into force date of the legislation.

Integration with existing requirements

If these consultation proposals are adopted The Pensions Regulator (TPR) will give consideration to whether those trustees who meet the requirements set out in our regulations should be deemed to have also met the standards in the forthcoming Governance code[footnote 43] insofar as they relate to climate change.

Disclosure

Publishing the TCFD disclosures

We propose that schemes be required to publish their TCFD report on their own website, or the website of the scheme’s sponsor.

We propose to require that – as a key financial disclosure –TCFD reporting is referenced from the Annual Report. As TCFD Reports done well could be quite long and detailed, we do not intend that the information will need to be presented in full within the Annual Report.

Further expectations on publication to which trustees must have regard will be set out in statutory guidance.

Telling members about the TCFD report

We propose that members will be told via the annual benefit statement that the information has been published and where they can locate it. DB schemes would only be required to add the link to the annual benefit statements of members for whom they already are required to produce one.

Where schemes issue their annual benefit statement months in advance of their Annual Report they would be required to direct members to the most recent TCFD report, or in the first year, the location where the TCFD report will be published in due course.

Reporting information back to TPR

We propose to require that trustees provide TPR with the web address of where they have published their TCFD report via the annual scheme return form. We also propose to require that trustees provide a link to their SIP and (where applicable) implementation statement and published excerpts of the chair’s statement in the annual scheme return form.

Penalties

We propose that a mandatory penalty is appropriate for complete failure to publish any TCFD report. Other penalties would be subject to TPR discretion. Penalties in relation to climate change governance and publication could be imposed without recourse to the Determinations Panel. We propose that requirements to reference the TCFD report from the Annual Report and inform members about the TCFD report’s availability would be subject to the existing penalty regime in the Occupational and Personal Pension Schemes (Disclosure of Information) Regulations 2013[footnote 44]. Our proposed requirements to inform TPR of the web address of the published TCFD report and the web address of the published SIP, implementation statement (where applicable) and excerpts of the Chair’s statement would be subject to the penalty regime in section 10 of the Pensions Act 1995.

-

Aligning your pension scheme with the TCFD recommendations. The Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group. ↩

-

International Monetary Fund. Global Financial Stability Report on Climate Change: Physical Risk and Equity Prices. ↩

-

See for instance, E Campiglio, P Monnin and A von Jagow, Climate Risks in Financial Assets. Council on Economic Policies Discussion note 2019/2. ↩

-

P Grippa, J Schmittmann, and F Suntheim (International Monetary Fund). Climate change and financial risk. Finance and Development December 2019 vol 56 number 4. Reproduced with permission. ↩

-

All Swans are Black in the Dark: how the short-term term focus of financial analysis does not shed light on long term risks. ↩

-

See source in footnote 2. ↩

-

There is also a statutory duty on many schemes for pension scheme assets to be invested in the best interests of members and beneficiaries. See the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment) Regulations 2005 (S.I. 2005/3378), regulation 4(2)(a). ↩

-

Pensions Climate Risk Industry Group. Chapter 3 of Aligning your pension scheme with the TCFD recommendations: consultation guidance. ↩

-

The Kay Review of UK Equity Markets and Long-Term Decision Making: Final Report – July 2012. ↩

-

Fiduciary Duties of Investment Intermediaries (LC350) – July 2014. ↩

-

Clarifying and strengthening trustees’ investment duties: the Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment) Regulations. ↩

-

The Pension Protection Fund (Pensionable Service) and Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment and Modification) Regulations 2018 (S.I. 2018/ 988). ↩

-

The requirement to produce and publish an implementation statement, and to link to it from the annual benefit statement – see regulation 5(2), 5(4)(b) and 5(5)(c) of the Regulations above. ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Governance) (Amendment) Regulations 2018 – SI 2018/1103. ↩

-

Section 90(5) of the Pensions Act 2004. ↩

-

The Occupational Pension Schemes (Investment and Disclosure) (Amendment) Regulations 2019 – SI 2019/982. ↩

-

96% of Trustees prepared for new RI regulation despite 8/10 facing challenges. ↩

-

Putting ESG into practice: the SPP member research series. ↩

-

Defined Contribution trust-based pension schemes research: report of findings on the 2019 survey. ↩

-

Final Report: Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (June 2017). ↩

-

Accelerating green finance: a report by the Green Finance Taskforce ↩

-

Her Majesty’s (HM) Government. Green Finance Strategy. ↩

-

See source in footnote 1. ↩

-

CP20/3: Proposals to enhance climate-related disclosures by listed issuers and clarification of existing disclosure obligations. ↩

-

Mark Carney and Therese Coffey. “Pension schemes must disclose what they are doing to fight climate change” Daily Telegraph 12 February 2020. ↩

-

Pension Schemes Bill volume 802, column 156 GC. ↩

-

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change dealing with greenhouse-gas emissions mitigation, adaptation and finance signed in 2016. ↩

-

To be issued by The Pensions Regulator under the Occupational Pension Schemes (Governance)(Amendment) Regulations 2018 relating to the requirement for an effective system of governance under section 249A of the Pensions Act 2004. ↩

-

S.I.2013/2734. ↩