Consultation on the United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (New York, 2018)

Updated 2 March 2023

Please send your response by 1 April 2022 to PIL@justice.gov.uk

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1) International trade is worth over £1tn to the UK Economy[footnote 1], and therefore it is crucial that UK businesses, big and small, continue to have the confidence to enter into cross-border contracts, investment relationships and to operate across borders in the knowledge that there are effective mechanisms in place to settle disputes as and when they arise.

1.2) The mediation sector in the UK has grown considerably in the last 15-20 years, with the sector estimated to be worth £17.5bn in 2020[footnote 2], as businesses look for more cost‑effective methods of resolving disputes outside of the traditional routes of court‑based litigation and arbitration. Mediation is an important means of resolving cross‑border disputes, by enabling the disputing parties to reach a suitable and mutually acceptable resolution themselves, without having to go to court, saving valuable time and money. It is a process which the Government considers ought to be integral to the Justice system, and it is estimated that mediation can save businesses around £4.6 billion per year in management time, relationships, productivity and legal fees[footnote 3].

1.3) The Singapore Convention on Mediation aims to provide a harmonised framework to enable parties seeking to enforce a cross-border commercial settlement agreement to apply directly to a Competent Authority (usually a Court) for the enforcement of that agreement.

1.4) The UK is already regarded as an international seat for arbitration and the Government is keen to understand whether that reputation, as well our reputation as a preferred seat for other forms of international dispute resolution, would be further strengthened by making it the same for mediation.

1.5) The Ministry of Justice conducted a focused, limited and informal consultation in September 2019, on whether the UK should become party to this Convention. Further information on this earlier consultation can be found at Chapter 4 of this consultation. Responses were broadly favourable with stakeholder feedback indicating that joining the Convention would raise the profile of mediation internationally and maintain the UK as an attractive dispute resolution hub. The Government also indicated that it was considering joining this Convention during the passage of the Private International Law (Implementation of Agreements) Act 2020, and that it could be implemented using the powers in that Bill, subject to stakeholder consultation.

1.6) The Convention may also present opportunities to establish new relationships in the Indo-Pacific, Middle East and Africa, as well as strengthening existing relationships with parties to the Convention, many of whom are members of the Hague Conference on Private International Law. This would align with the Government’s Integrated Review of 16 March 2021, which outlines its vision for the UK’s role in the world over the next decade and the action that will be taken to 2025. It is noted that several countries mentioned in the Integrated Review are already signatories to the Singapore Convention, including 18 Commonwealth nations with senior Commonwealth leaders continuing to encourage their members to sign the Convention, as well as key UK trading partners USA, China and India.

1.7) However, as part of the Government’s decision-making process about whether to become Party to this Convention it is important to obtain a wide range of views, especially from those who have first-hand experience of mediation law and practices in the UK, what works well and where improvements are required. For this reason, we are particularly keen to hear the views of any person or group in the UK with expertise or interest in mediation or the dispute resolution sector more generally, businesses which operate internationally and trade organisations with an international element. This may include (but is not limited to) legal professionals, academics, or civil society groups / charities.

Chapter 2: Background

This consultation

2.1) In this consultation we are seeking views on whether the UK should become party to the Singapore Convention on Mediation 2018 and implement it in UK domestic law.

2.2) Please note that whilst there are questions and topics for discussion included in some sections of this consultation paper there is also a consolidated list of questions within the separate questionnaire at the end.

What is the Singapore Convention?

2.3) The United Nations Convention on International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (New York, 2018) (the “Singapore Convention on Mediation”) is a Private International Law agreement which establishes a uniform framework for the effective recognition and enforcement of mediated settlement agreements across borders. It provides a process whereby someone seeking to rely upon a mediated settlement agreement can apply directly to the competent authority of a Party to the Convention to enforce the agreement. Only in limited circumstances can the relevant authority refuse to do so (such as the agreement being void or having been subsequently amended).

2.4) The Singapore Convention aims to facilitate international trade and commerce by strengthening trust in dispute resolution and promoting mediation as an effective means to resolve any disputes in cross-border commercial transactions.

Scope of the Convention

2.5) The Singapore Convention only applies to international commercial settlement agreements resulting from mediation.

2.6) It does not apply to mediated settlement agreements: - concluded in the course of judicial or arbitral proceedings and which are enforceable as a court judgment or arbitral award; - concluded for personal, family or household purposes by one of the parties (a consumer); - or those relating to family, inheritance or employment law.

Negotiation and signing of the Convention

2.7) The Convention was negotiated at the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), a legal body that works for the modernisation and harmonisation of rules on international business and specialises in commercial law reform. It has negotiated a number of international agreements, conventions and model laws, including the 1958 New York Convention on arbitration.

2.8) The Convention was finalised in June 2018, alongside an updated Model Law on “International Commercial Mediation and International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, 2018”. The Convention was adopted under resolution 73/198 of the United Nations General Assembly on 20 December 2018.

2.9)The signing ceremony was held in Singapore on 7 August 2019; 70 countries attended this event, with 46 countries signing the Convention that day. The Convention came into force on 12 September 2020 (after the third instrument of ratification was deposited) and currently has 55 signatories and 9 parties have ratified it.

Becoming a party to the Convention

2.10) It should be noted that in international law a treaty does not enter into force upon signature, but only after ratification. In the case of the Singapore Convention this is six months after ratification. If the UK were to sign the Convention, then legislation would also need to be passed in order to ratify and become a Party to the Convention.

Who has signed the Singapore Convention?

Parties

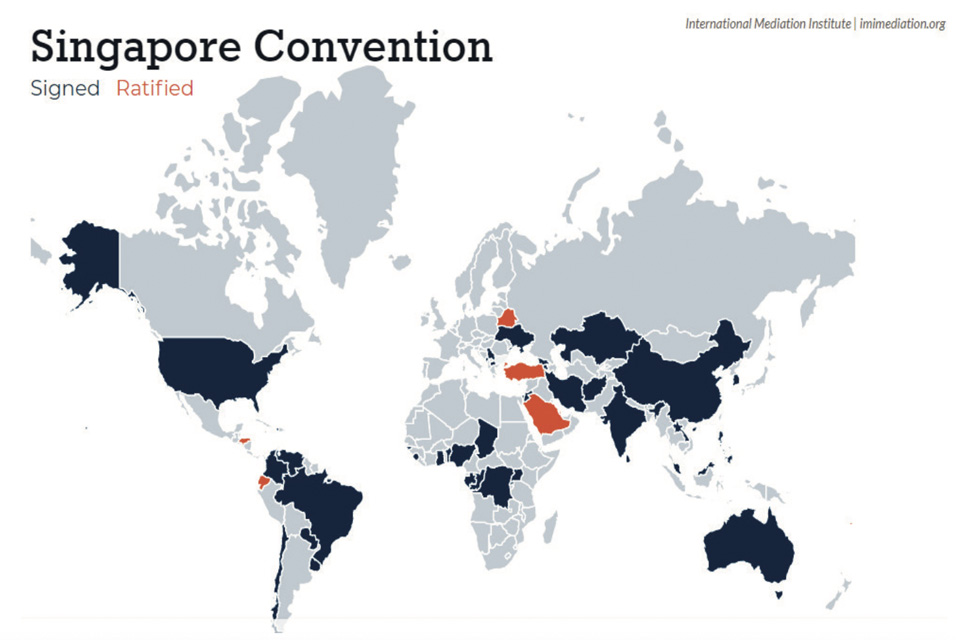

2.11) As stated above there are currently 9 parties to the Convention (Correct at time of publication). These are Fiji, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Belarus, Ecuador, Honduras, Turkey, Georgia and Singapore.

2.12) It is noted that Honduras ratified the Convention on 2 September 2021 and so the Convention will come into force for Honduras on 2 March 2022. The Convention will similarly come into force for Turkey, who ratified it on 11 October 2021, and Georgia, who ratified it on 29 December 2021, on 11 April 2022 and 29 June 2022 respectively.

Signatories

2.13) The following 55 countries have signed the Singapore Convention (Correct at time of publication):

Afghanistan, Armenia, Australia, Belarus, Belize, Brazil, Brunei, Chad, Chile, China, Colombia, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ecuador, Kingdom of Eswatini, Fiji, Gabon, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guinea-Bissau, Haiti, Honduras, India, Iran, Israel, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Laos, Malaysia, Maldives, Mauritius, Montenegro, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Palau, Paraguay, Philippines, Qatar, Rwanda, South Korea, Samoa, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Sierra Leone, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Timor Leste, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine, the USA, Uruguay and Venezuela.

Map of Singapore Convention signatories and parties[footnote 4]

Questions:

Q1: Do you consider that this is the right time for the UK to become a Party to the Convention (i.e. to sign and ratify as set out in 2.10 above)?

Q2: What impact do you think becoming Party to the Convention will have for UK mediation and mediators?

Q3: What impact do you consider the Singapore Convention would have on the UK mediation sector and particularly on the enforceability of settlement agreements?

Q4: What impact do you think becoming Party to the Convention might have on other forms of dispute resolution?

Q5: What legal impact will becoming Party to the Convention have in your jurisdiction (i.e. in England and Wales, in Scotland or in Northern Ireland)?

Q6: What might be the downsides of the UK becoming Party to the Convention?

Chapter 3: The provisions of the Convention

Key features of the Singapore Convention

3.1) In addition to only applying to settlement agreements resulting from mediation of commercial disputes, the Convention also sets out that the Competent Authority (for example the Courts) of a Party to the Convention is expected to handle applications either to enforce an international mediated settlement agreement which falls within the scope of the Convention, or to allow a Party to the Convention to invoke the settlement agreement in order to prove that the matter has already been resolved, in accordance with its rules of procedure, and under the conditions laid down in the Convention.

Definition of an International settlement agreement

3.2) A mediated settlement agreement will be international in nature, under the terms of Article 1(a) and (b) of the Convention, if at the time of its conclusion:

“(a) At least two parties to the settlement agreement have their places of business in different States; or

(b) The State in which the parties to the settlement agreement have their places of business is different from either:

(i) The State in which a substantial part of the obligations under the settlement agreement is performed; or

(ii) The State with which the subject matter of the settlement agreement is most closely connected.”

Reliance on the Convention

3.3) The terms of the Convention state that an agreement resulting from mediation must be concluded in writing by the parties resolving a commercial dispute and that an agreement is “in writing” if its content is recorded in any form, including through an electronic communication if the information contained therein is accessible “so as to be useable for subsequent reference”.

3.4) Article 4 of the Convention sets out the requirements for reliance on settlement agreements under the Convention:

3.5) Where relief is sought, a party relying on a settlement agreement will need to supply to the competent authority:

“(a) The settlement agreement signed by the parties;

(b) Evidence that the settlement agreement resulted from mediation, such as:

(i) The mediator’s signature on the settlement agreement;

(ii) A document signed by the mediator indicating that the mediation was carried out;

(iii) An attestation by the institution that administered the mediation; or

(iv) In the absence of (i), (ii) or (iii), any other evidence acceptable to the competent authority.”

3.6) The Convention establishes that the requirement that a settlement agreement shall be signed by the parties or, where applicable the mediator, is met in relation to an electronic communication if:

“(a) A method is used to identify the parties or the mediator and to indicate the parties’ or mediator’s intention in respect of the information contained in the electronic communication; and

(b) The method used is either:

(i) As reliable as appropriate for the purpose for which the electronic communication was generated or communicated, in the light of all the circumstances, including any relevant agreement; or

(ii) Proven in fact to have fulfilled the functions described in subparagraph (a) above, by itself or together with further evidence.”

3.7) The Convention states that if the settlement agreement is not in an official language of the Party to the Convention where relief is sought, then the competent authority may request a translation and the competent authority may require any necessary document in order to verify that the requirements of the Convention have been complied with.

Grounds for refusing relief

3.8) The Competent Authority of a Party to the Convention may refuse to grant relief, under Article 5.1, if the party against whom relief is sought provides proof that one of the grounds laid down in the Convention has been met, namely:

“(a) A party to the settlement agreement was under some incapacity;

(b) The settlement agreement sought to be relied upon:

(i) Is null and void, inoperative or incapable of being performed under the law to which the parties have validly subjected it or, failing any indication thereon, under the law deemed applicable by the competent authority of the Party to the Convention where relief is sought under article 4;

(ii) Is not binding, or is not final, according to its terms; or

(iii) Has been subsequently modified;

(c) The obligations in the settlement agreement:

(i) Have been performed; or

(ii) Are not clear or comprehensible;

(d) Granting relief would be contrary to the terms of the settlement agreement;

(e) There was a serious breach by the mediator of standards applicable to the mediator or the mediation without which breach that party would not have entered into the settlement agreement; or

(f) There was a failure by the mediator to disclose to the parties’ circumstances that raise justifiable doubts as to the mediator’s impartiality or independence and such failure to disclose had a material impact or undue influence on a party without which failure that party would not have entered into the settlement agreement.”

3.9) Article 5.2 states that the competent authority may also refuse to grant relief if it finds that:

“(a) Granting relief would be contrary to the public policy of that Party; or

(b) The subject matter of the dispute is not capable of settlement by mediation under the law of that Party.”

Seat of Mediation is not relevant under the Convention (non-reciprocal)

3.10) Under the Convention a Contracting Party to the Convention (I.e. a State Party to the Convention) is obliged to enforce an international mediated settlement agreement irrespective of where it emanates from. This means that the seat of the mediation, i.e. where the agreement was made or signed is not relevant. The Contracting Party’s obligations are not limited to enforcing agreements made in other Contracting Parties. As long as the settlement is international in nature and comes from a mediation (and is not otherwise excluded) it will qualify for enforcement in a Contracting Party, regardless of its place of origin. In this way the Convention has been described as being non-reciprocal.

3.11) This means it will be possible for a settlement agreement to be signed in the UK and then enforced under the Convention in another jurisdiction, if that state is a party, even if the UK decides not to ratify the Convention.

3.12) It is considered that, as the UK is already a well-established and attractive dispute resolution hub, the Convention could bring further mediation business to the UK regardless of whether the UK signs and ratifies the Convention. Disputants favouring UK law to resolve their disputes will know that they can seek to mediate in the UK and later pursue enforcement under the Convention in a jurisdiction which operates the Convention, if appropriate to do so.

Questions:

Q7: Are there any specific provisions which cause concern or that may adversely affect the mediation sector in the UK? For example, the broad definition of mediation in the Convention’s text?

Q8: The Convention states that a settlement agreement must be concluded “in writing” and that this requirement will be met if it is recorded ‘in any form’. Do you envisage any difficulties for the enforcement of settlement agreements under the Convention given the broad definition of “in writing”?

Q9: What types of “other” evidence should a Competent Authority consider as acceptable evidence of settlement agreements in the absence of the proof specified in Article 4.1.b (i)-(iii) of the Convention?

Q10: Article 5.1(e) of the Convention states that enforcement may be refused if “There was a serious breach by the mediator of standards applicable to the mediator or the mediation without which breach that party would not have entered into the settlement agreement”. Do you have any comments on which ‘standards’ may be applicable? (Please also see the linked Question 16 below.)

Q11: The Convention provides that each Contracting Party to the Convention shall enforce a settlement agreement. What types of provision is usually included in settlement agreements that may need to be enforced? I.e. will the Competent Authority need particular powers to cover these provisions?

Q12: What are your views on the provisions of the Convention meaning that:

a) If the UK were to become Party to the Convention, it would be expected to enforce settlement agreements of both contracting and non-contracting parties?

b) If the UK were not to become Party to the Convention, UK mediated settlement agreements could still be enforced in a country which is a Party to the Convention?

Reservations

3.13) A Party to the Convention may declare (under Article 8) that:

“(a) It shall not apply this Convention to settlement agreements to which it is a party, or to which any governmental agencies or any person acting on behalf of a governmental agency is a party, to the extent specified in the declaration;

(b) It shall apply this Convention only to the extent that the parties to the settlement agreement have agreed to the application of the Convention” (an opt-in clause).

3.14) These Reservations may be made by a Party to the Convention at any time and must be registered with the depositary. Reservations made at the time of signature will be subject to confirmation upon ratification, acceptance or approval and will take effect simultaneously with the entry into force of the Convention for that Party. Similarly, reservations made at the time of ratification, acceptance or approval will take effect when the Convention comes into force for that party, however reservations made after ratification will come into force six months after they are deposited with the depositary.

3.15) It is noted that some of the parties to the Convention have made reservations, with Belarus and Saudi Arabia stating that the Convention will not apply to public contracts involving the government or any of its agencies. It is also noted that at the time of signing the Convention, Iran also applied the 8(b) reservation whereby the parties have to have agreed to the application of the Convention (opt-in clause).

Questions:

Q13: The Government will consider whether the UK should make either reservation under Article 8 should it ratify the Convention, namely:

a) “it shall not apply this convention to settlement agreements to which it is a party or to which any governmental agencies or any person acting on behalf of a governmental agency is a party”; and/or

b) “It shall apply this Convention only to the extent that the parties to the settlement agreement have agreed to the application of the Convention”

What are your views on this?

Chapter 4: Summary of previous informal Ministry of Justice consultation of 2019

Potential advantages of becoming Party to the Convention

4.1) In the autumn of 2019, the Ministry of Justice conducted a focused, limited and informal consultation on the Convention. The mediation organisations who responded suggested that signing the Convention would help to maintain the UK’s status as a leading centre for mediation and may also have the effect of raising the profile of mediation internationally as an important method of dispute resolution, alongside arbitration and litigation. Some of the suggested benefits of mediation and the Singapore Convention that arose in that consultation are summarised as follows:

- The Convention will provide reassurance that a mediated outcome will have the same protection that international arbitral awards have, under the New York Convention 1958 on arbitration, namely that they will be readily enforceable in different jurisdictions.

- It may reduce frustration amongst mediators, who conduct numerous successful cross-border mediations without enforcement issues arising, but nonetheless face the reality that parties are reluctant to mediate due to worries over enforcement across different jurisdictions.

- Whilst it is possible for a mediation agreement to form part of an arbitration award, for example where an Arbitration-Mediation-Arbitration (Arb-Med-Arb) procedure is available, this procedure is not universally available. A summary procedure for the enforcement of mediated agreements is therefore generally desired by the commercial community.

- Endorsing the Convention will help to uphold the UK’s worldwide reputation for being at the centre of the commercial dispute resolution business. The UK risks losing out if, while still practically having an effective framework for mediation and enforcement of settlement agreements, it is not perceived to be backed up by the international legal framework which the Singapore Convention offers.

- Government policy for at least the last 20 years, since the Lord Woolf Civil Justice Reforms[footnote 5], has been to promote dispute resolution methods, particularly mediation, for domestic cases and so it would be inconsistent to adopt a different approach to international disputes. Ratification would signal the UK’s commitment to all forms of dispute resolution.

- The Convention would provide for more robust enforcement or clarification in the minority of cases where changed circumstances or new information means that a party may seek to extricate itself from, or to enforce, an agreement that has been apparently entered into freely.

- Evidence suggests that arbitration is no longer a quicker and more efficient alternative to litigation in commercial cases. Mediation has increased in popularity, as it can take place before and during the course of arbitration proceedings.

4.2) With regards to the last point, it is recognised that the Singapore Convention will not apply to International Mediated Settlement Agreements reached through hybrid proceedings, such as during the course of court proceedings or arbitration. However, the Convention may encourage more parties to rely solely on mediation proceedings to resolve their dispute, rather than seeking to initiate arbitration proceedings, during the course of which a mediation may take place as part of a longer and potentially more costly process.

Question:

Q14: Do legal practitioners consider that there could still be confusion or uncertainty about when the Singapore Convention may apply? I.e., could a disputing party seek to invoke the Convention if, during the course of arbitral proceedings, a mediation resolves the matter at hand without an arbitral award being handed down?

4.3) In addition to the above feedback, it is also noted that the International Mediation Institute (IMI) previously conducted a short survey in October and November 2014 which included an assessment of the extent to which a mediation enforcement convention was desired. In response almost 93% of respondents answered positively that they would be more likely to mediate a dispute with a party from another country if they knew that country had ratified a UN Convention that meant any settlement could easily be enforced there[footnote 6].

Questions regarding about the practical benefits of the Convention

4.4. Although the feedback to the Ministry of Justice’s 2019 consultation was largely supportive of the UK signing the Convention, some practitioners stated that, in practice, there is rarely a need to enforce a mediated settlement agreement as the parties to a mediation agree to the process and the settlement is reached by mutual consensus. Stakeholders stated:

- There is no universal consensus among practitioners that concerns about the ability to enforce mediated settlement agreements is holding the dispute resolution sector back significantly and has resulted in a reluctance to mediate.

- The broad definition of mediation in the Convention may result in settlements which have been negotiated with some relatively informal third-party assistance falling within the scope of the Convention.

- Unlike the New York Convention on Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral awards 1958, under the Singapore Convention the UK would be agreeing that its courts should enforce settlement agreements between international parties reached in mediations held anywhere in the world, irrespective of the seat of the mediation.

- There may be an argument for considering that granting to mediation the kind of enforcement regime that international arbitration has enjoyed since 1959, under the New York Convention, is more about branding mediation as a product than addressing a real concern among the international business community.

- There was opinion that the Convention will only be called upon in a limited number of cases. Mediation practitioners stated that as mediation outcomes are achieved voluntarily and after difficult negotiations, parties are more likely to comply with settlement agreements, as opposed to litigated actions or international arbitration.

4.5) It is acknowledged that the Convention’s broad definition of ‘mediation’ could mean that an agreement could be reached with relatively informal assistance. It is also noted that there is currently no formal regulation for mediators as a defined group and so an agreement could be reached without reference to the relevant codes of conduct and standards ordinarily applicable. It is however noted that the majority of UK mediators will be legal practitioners who are themselves regulated by their respective professional bodies.

4.6) Since finalising the text of the Convention and accompanying Model Law, UNCITRAL, through its Working Group ii which negotiated those texts, have commenced work on negotiating further guidance and rules on international commercial mediation. The draft texts seek to address the various aspects of mediation practice, including conduct and standards. The links to these documents are included below:

- Draft UNCITRAL mediation Rules

- Draft UNCITRAL Notes on Mediation

- Draft Guide to Enactment and Use of the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Mediation and International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (2018)

4.7) It is intended that these Mediation documents, when finalised, will be consistent with the texts of the Singapore Convention and Model Law already in force, although they will also be applicable for hybrid proceedings (such as arbitration with mediation) as well as for use with the Convention and will therefore provide information and guidance on mediation processes and procedures.

Question:

Q15: Do you consider that a lack of regulation and the potential differences in conduct and standards amongst Parties to the Convention could present any particular challenges to the application of the Convention in the UK?

Chapter 5: Cross-Border Mediation in the UK at the present time

5.1) From 1 January 2021, the EU Mediation Directive (Directive 2008/52/EC) generally ceased to apply between the UK and the EU member states[footnote 7]. Cross-border mediations which commenced in the UK after this date are now subject to the same rules as our domestic mediations, except where (before the end of the transition period) the court invited or ordered the parties to use mediation or where the parties agreed to mediation. UK solicitors involved in a cross-border mediation which takes place outside of the UK are now subject to the foreign lawyers’ practice of the respective country in which the mediation is being conducted.

5.2) It is noted that there are existing mechanisms in UK domestic law, in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, that allow for the enforcement of mediated agreements. For example, a party to such an agreement from elsewhere in the world can in principle bring an action for breach of contract in the courts in England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland to enforce that agreement (subject to our usual jurisdiction rules and contractual law).

5.3) Whilst this consultation is specifically about the Singapore Convention, the Government is also working more widely on the Dispute Resolution in the England and Wales. If you are interested in finding out more about this work please contact: disputeresolution.enquiries.evidence@justice.gov.uk

Questions:

Q16: What impact do you consider the Singapore Convention would have on the UK mediation sector and particularly on the enforceability of settlement agreements?

Q17: Would you foresee any intra-UK considerations if the Singapore Convention was to be implemented in only certain parts of the UK?

Chapter 6: Present enforcement of an international commercial mediated settlement agreement in the UK vs enforcement under the Singapore Convention

6.1) A successful cross-border mediation usually results in an International Mediated Settlement Agreement (IMSA). However, these agreements traditionally have the same legal status as any other contract. There is currently no mechanism for IMSAs to be directly enforced in the UK and so if one of the parties refuses to honour the terms of the IMSA, the other party will have to rely on usual methods for contractual enforcement.

6.2) As the Singapore Convention only applies to international settlement agreements reached through mediation, and not, for example, as part of arbitration proceedings, we will focus on the enforcement of such agreements in the UK as a contract as compared to direct enforcement under the Singapore Convention.

Contract Law in the UK

6.3) An IMSA can at present typically be enforced as a contract in the UK if the contract is valid, does not exclude a UK court from having jurisdiction and the UK court accepts jurisdiction.

6.4) This method of enforcement requires the aggrieved party to bring a claim for breach of contract in order to enforce an obligation in the contract.

6.5) The Singapore Convention aims to provide for the direct enforcement of international commercial settlement agreements resulting from mediation. It could therefore establish an expedited procedure which does not currently exist in the UK.

Enforcement under the Singapore Convention

6.6) It is anticipated that a party seeking to enforce a settlement agreement will file an application or claim form with a court (competent authority) for direct enforcement, rather than seeking a mediation settlement enforcement order.

6.7) For the Singapore Convention to apply an IMSA must be in writing, signed by all parties and there should be an attestation from the mediator or mediation organisation. It is therefore expected that such an agreement will result in a new contract between the parties, the text of which could be presented directly to a Competent Authority for enforcement of any breaches of the terms agreed.

6.8) The Convention does not stipulate the grounds which must be included in a settlement agreement, but instead provides a framework for the disputing parties and the mediator to work within and for enforcement where necessary.

6.9) It is expected that any facts and representations which are crucial to the terms of a settlement will be included in the settlement agreement, including any costs involved, agreements to deliver goods or services (known as performance) as well as any consequences for failure to adhere to those terms, and that the terms will have been scrutinised by the legal representatives to the parties.

6.10) Although we anticipate that the majority of agreements will be honoured, it will nonetheless be important for agreements to be clearly drafted to help maintain amicable business relationships between the parties, and to also ensure that the agreement falls within the scope of the Convention.

Grounds for Refusing Enforcement

6.11) In common law, for England and Wales, if a court determines that a mediated commercial settlement agreement constitutes a contract, or that a foreign judgment relating to a settlement agreement is valid, then enforcement can only be refused on the grounds of unfairness, illegality, public policy or fraud. This provides parties with a mechanism for challenging the enforcement of a mediated settlement agreement but limits such challenges so as to prevent a party from refusing to honour an agreement on the basis that they have simply had a change of heart.

6.12) As set out above, the Singapore Convention also contains grounds under which a Competent Authority of a Party to the Convention may refuse to grant relief, and so provides a method of challenging the enforceability of a mediated settlement agreement, but only in a limited set of circumstances. Although this does include mediator conduct, there would have to be evidence of a serious breach of mediator standards, so that the party could establish that it would not otherwise have entered into the agreement.

Questions:

Q18: In relation to paragraph 6.11 (above) how do you consider that the provisions for enforcement under the Convention would apply in your jurisdiction?

Q19: What are your opinions on the practical benefits of the Singapore Convention providing for direct enforceability or in respect of the benefits of the wider grounds than in the existing common law?

Q20: Who do you consider to be the appropriate Competent Authority for a Party to the Convention to lodge an application or claim with, in order to enforce a mediated settlement agreement (e.g. the County Court, High Court, Court of Session)?

Q21: Would the implementation of the Convention require any procedural changes to the Court systems of England and Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland, to enable its effect operation?

Chapter 7: The Model Law on International Commercial Mediation and International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation (2018)

7.1) UNCITRAL has also updated its “Model Law on International Commercial Conciliation”, originally adopted in 2002, and this can be used as the basis for enactment of legislation on mediation, including the Singapore Convention.

7.2) The Model Law[footnote 8] is designed to:

- assist States in reforming and modernising their laws on mediation procedure.

- provide uniform rules in respect of the mediation process

- encourage the use of mediation and ensure greater predictability and certainty in its use.

7.3) The Model Law text has also been amended to ensure consistency with the Convention. It now only refers to “mediation”, instead of referring to both “conciliation” and “mediation” as interchangeable phrases.

7.4) The Model Law addresses procedural aspects of mediation, including but not limited to: the appointment of mediators, the commencement and termination of mediation, the conduct of the mediation and the communication between the mediator and other parties and confidentiality and admissibility of evidence.

7.5) The Model Law also provides ‘uniform rules on enforcement of settlement agreements and addresses the right of a party to invoke a settlement agreement in a procedure. It provides an exhaustive list of grounds that a party can invoke in a procedure covered by the Model Law’.

Question:

Q22: As mediation practice and legislation are well established in the UK, the government does not intend to use the Model Law provisions to implement the Singapore Convention. Do you have any views on this or on whether the UK should in fact apply the Model Law instead of ratifying the Convention?

Chapter 8: Parliamentary Scrutiny

8.1) In the event that the Government decides, having given careful consideration to all of the representations received in response to this consultation, that the UK should sign and ratify the Singapore Convention on Mediation, then the convention would be implemented under the terms of the Private International Law (Implementation of Agreements) Act 2020, via Secondary Legislation. It would be subject to the normal parliamentary scrutiny procedures, including under the Constitutional Reform and Governance (CRaG) Act 2010 and the affirmative Statutory Instrument (SI) procedure. An SI laid under the affirmative procedure must be actively approved by both Houses of Parliament.

8.2) Negotiating and joining international Conventions like this is a reserved matter with regard to Scotland and Northern Ireland; however, the implementation in domestic law is a devolved matter in these jurisdictions. With regard to Wales the negotiation, joining and implementation of any Convention like this is a reserved matter. We would work closely with the Devolved Administrations regarding the implementation of the Convention in their respective jurisdictions.

Chapter 9: The Proposals

9.1) This consultation is intended to gather expert views from practitioners, academics, businesses, and any other persons with an interest in or who may be affected by cross-border commercial mediation in the UK, to enable the UK Government to decide whether to sign and ratify the Singapore Convention on Mediation.

9.2) In addition to analysing responses to this consultation, officials will engage with relevant experts, including the Lord Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on Private International Law, prior to publishing the results of this consultation.

9.3) Officials will give careful consideration to all responses to this consultation. In the event that the overall analysis of the Singapore Convention on Mediation confirms that UK stakeholders are in favour of the UK becoming a Party to the Convention, then the Government intends to make a final decision on signing and ratifying in a timely manner and would commence the necessary processes to ensure that this can be achieved within a reasonable timescale, in consultation with the devolved administrations of Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales.

9.4) The Singapore Convention would be implemented in UK domestic law under the terms of the Private International Law (Implementation of Agreements) Act 2020, subject to appropriate parliamentary scrutiny. The Convention would enter into force for the UK six months after the date it deposits its instrument of ratification.

Thank you for participating in this consultation exercise.

-

DIT, 2021. UK Trade in Numbers, January 2022] ↩

-

Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution ‘The full Ninth Mediation Audit’ - www.cedr.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CEDR_Audit-2021-lr.pdf ↩

-

Centre for Effective Dispute Resolution ‘The full Ninth Mediation Audit’ ↩

-

International Mediation Institute website, article on Turkey becoming a Party to the Convention dated 14 October 2021 - Turkey Ratifies the Singapore Convention — International Mediation Institute (imimediation.org). ↩

-

This year marks the 25th anniversary of Lord Woolf’s report on Access to Justice. ↩

-

https://www.imimediation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/IMI-UN-Convention-on-Enforcement-Survey-Summary-final-27.11.14.pdf ↩

-

The Directive is preserved in certain situations under Article 67 1(b) of the Withdrawal Agreement -see EUR-Lex - 12019W/TXT(02) - EN - EUR-Lex (europa.eu) ↩

-

UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Mediation and International Settlement Agreements Resulting from Mediation, 2018 (amending the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Conciliation, 2002) ↩