Public consultation on trade negotiations with Australia (web/online version)

Updated 17 June 2020

Foreword from the Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade

The United Kingdom is on the cusp of a new era in our great trading history. For the first time in nearly 50 years, we will have the freedom to pursue an independent trade policy to build a stronger, fairer and more prosperous country, more open and outward-looking than ever before.

The government, led by my Department for International Trade, has been preparing for the United Kingdom to have an independent trade policy after we exit the European Union. We have made great strides forward. We have opened 14 informal trade dialogues with 21 countries from the United States to Australia to the United Arab Emirates. We have also been working closely with our existing trading partners to ensure the continuity of European Union trade deals. The United Kingdom’s trade with countries with which we are seeking continuity[footnote 1] accounted for £139 billion or 11% of the United Kingdom’s trade in 2018.[footnote 2]

We have already signed a number of these continuity agreements which replicate the effects of the existing agreements, as far as possible. This includes Switzerland, which is one of our key trading partners and worth 2.3%[footnote 3] of the United Kingdom’s total trade. Other agreements have been signed with Israel, the Palestine Authority, Chile, the Faroe Islands, Eastern and Southern Africa, Caribbean countries, Iceland and Norway, Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Colombia, Peru and Ecuador.[footnote 4] We have also agreed in principle an agreement with Korea which will be signed shortly. In addition to this, we have also signed Mutual Recognition Agreements with Australia, New Zealand and the United States. We will continue to work tirelessly to deliver the maximum possible continuity and certainty for when we leave the European Union.

In addition, we have made significant headway on the United Kingdom’s future independent membership of the World Trade Organization: we have submitted our proposed commitments on goods and services; established our own independent trade remedies system (the Trade Remedies Authority); and published the Export Strategy and launched 14 working groups and a number of trade reviews with key partners.

The government is determined to build a new economic relationship with the European Union. One which sees the United Kingdom leave the Single Market and the Customs Union to seize new trading opportunities around the world, while protecting jobs, supporting growth and maintaining security co-operation. We recognise that our future economic partnership with the European Union will have considerable and immediate implications for the way the United Kingdom can develop its future trade policy, in terms of its trading agreements with the rest of the world. We will continue to listen and respond to our stakeholders’ views on this as we develop our own independent trade policy in parallel with the direction of the future relationship negotiations with the European Union.

An independent trade policy means we can negotiate trade agreements specifically tailored to the United Kingdom, building links with old friends and new allies, enabling the United Kingdom to take advantage of emerging sources of growth and to deepen ties with our established partners to create shared and sustainable growth.

In July last year, we launched consultations on new free trade agreements. The consultations demonstrated the United Kingdom’s intention to seek free trade agreements with the United States, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the United Kingdom potentially seeking accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, a plurilateral agreement with 11 existing members).

We have engaged fully with the devolved administrations, and consulted extensively with stakeholders across the business community, civil society, academia and the general public on priorities for trade negotiations to ensure we represent the interests of the whole of the United Kingdom in any future negotiation.

We have received 601,121 responses to the 4 consultations on future trade agreements. I would like to thank all those who took the time to contribute to this consultation. The government is committed to an inclusive and transparent trade policy, so today, I am publishing a summary of the consultation responses we received across the 4 consultations.

The Rt Hon Dr Liam Fox Secretary of State for International Trade and President of the Board of Trade

Introduction

Background

1) As the United Kingdom (UK) leaves the European Union (EU), we will have an independent trade policy for the first time in nearly 50 years. This will give us the opportunity to forge new and ambitious trade relationships around the world, and to enter into new free trade agreements (FTAs) with other countries or groups of countries.

2) The government remains committed to building a deep and special trading partnership with the EU, but through our new independent trade policy, we can also take advantage of shifts in the global economy: According to the IMF, 90% of the world economic growth over the next 5 years is forecast to come from outside the EU[footnote 5] ; and 54% of the UK’s exports of goods and services are now traded outside the EU[footnote 6] , compared with only 46% in 2006.

- Through negotiating FTAs, we can work with our trading partners around the world to break down barriers to trade in goods and services, ensure that UK businesses are treated fairly, and protect our right to regulate and maintain high standards, creating the conditions for individuals and businesses to prosper. Our ambition is to:

- increase economic growth and productivity, through increased trade and investment, promoting greater competition and innovation

- provide new employment opportunities, including higher-skilled jobs, from greater specialisation, increasing wages and opportunity across the UK

- deliver a greater variety of products for consumers at a lower cost while maintaining quality

Why this free trade agreement?

4) An early priority for the UK’s independent trade policy will be to negotiate a comprehensive FTA with Australia. A UK-Australia FTA would further cement our existing bilateral partnership, which is built on our shared heritage and values and extensive people-to-people links. The UK and Australia already enjoy a strong and growing trade relationship, with UK-Australia trade worth £15.3 billion in 2018.[footnote 7] The UK is the third largest investment partner in Australia and the 9th most popular destination for UK foreign direct investment (FDI). Australia is the 13th largest source of FDI in the UK.[footnote 8]

5) Australia is also one of our closest allies, sharing the same head of state, HM the Queen, and cooperating extensively across security, prosperity and defence. We are both active supporters of the international rules-based system and the UK works closely with Australia in many multilateral forums including the United Nations (UN), G20, World Trade Organization (WTO) and the Commonwealth. We are both strong advocates of free trade and, at a time of rising protectionism, our co-operation sends a strong message and provides the opportunity to negotiate the highest quality FTA.

A transparent and inclusive trade policy

6) As set out in the Trade White Paper Preparing for our future UK trade policy published in October 2017, the government is committed to pursuing a trade policy which is inclusive and transparent. To ensure that any future FTA works for the whole of the UK, the government is therefore committed to seeking views from a broad range of stakeholders from all parts of the UK. In July 2018, the government published DIT’s approach to engagement for the pre-negotiation phase of trade negotiations setting out its plan for pursuing new trade negotiations collaboratively by engaging with the widest range of stakeholder groups, as it takes forward its free trade agenda. For new FTAs, we have run broad open consultations. We will continue to engage as widely as possible as we look ahead to negotiations potentially starting soon.

7) On 20 July 2018, the Department for International Trade (DIT) launched four 14-week public consultations seeking views on potential FTAs with the United States (the US), Australia and New Zealand, and potential accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). To support this, the government ran a series of events around the UK to promote the consultations. All 4 consultations closed on 26 October 2018. This document sets out the findings from the responses received.

8) DIT welcomed feedback and comments from all interested parties to the consultations. Across the 4 consultations, the government received over 600,000 responses including those submitted by campaigns. They have been analysed and are informing the government’s overall approach to the 4 potential future trade deals. The consultation feedback will also support the government in meeting its commitment to delivering a UK trade policy which will benefit the UK economy, and businesses, workers, producers and consumers.

9) While many respondents welcomed the opportunities that an independent trade policy will bring as we leave EU, many respondents also mentioned the importance of the UK’s future economic relationship with the EU. We recognise that the UK’s future trade policy, including our ability to negotiate FTAs, will depend on the scope and substance of our future economic relationship with the EU. While comments on the UK government’s vision for the Future Economic Partnership (FEP) with the EU were outside the scope of the questions asked in this FTA consultation, they have, however, been included in our analysis.

What we asked

10) Each consultation was based on a series of questions concerning the respondent’s priorities and concerns regarding the relevant agreement. The questions were broad to ensure the consultation exercise was inclusive and would encourage participation from a wide range of stakeholders. We received responses from individuals, businesses, business associations, public sector bodies, trade unions and other non-governmental organisations (NGOs). The online survey covered a range of policy areas which are typically included in any comprehensive FTA.

These were:

- tariffs

- rules of origin (RoO)

- customs

- procedures services digital

- product standards, regulation and certification

- sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures

- competition

- government (public) procurement

- intellectual property (IP)

- investment

- labour and environment

- trade remedies and dispute settlement

- small and medium sized enterprise (SMEs) policy

- other

Respondents were also able to submit additional comments not related to the areas listed above. A full list of all the questions asked during this consultation is available in annex A.

This report

11) This document is a summary of what respondents said in the consultation on trade negotiations with Australia (the consultation). The evidence provided from the responses to this consultation (as summarised in this document), will inform the government’s overall approach to our future trading relationship with Australia, including our approach to negotiating any trade agreement. As we look ahead to finalising our negotiating objectives, we will continue to actively consider the consultation feedback to inform this work. Decisions made as a result of this consultation will therefore be published alongside our negotiating objectives before potential negotiations start. This report, therefore, does not set out government policy with respect to future trade policy, but simply provides a summary of what consultation respondents have told us. The government will take all responses to this consultation into account. A number of respondents raised points which fell outside the scope of this consultation. However, they have still been included in the statistical analysis.

12) We also received a large number of responses from outside the UK. The views provided in these responses will be analysed carefully and considered.

13) This document does not contain a list of the respondents or contain any personal or organisational details of the respondents. Their views are summarised in the following sections of this report but are not attributed to any individual respondent or business. The figures in this document refer to those who responded to the consultation, so should not be treated as statistically representative of the public at large.

14) The government does not intend to publish any individual consultation responses it received. Many organisations have published their own responses independently.

15) DIT commissioned the research agency Ipsos MORI to analyse responses for all 4 consultations and produce statistical analysis with a summary of the overall findings. This analysis supplements the review of consultation feedback undertaken by the government. Ipsos MORI developed a code frame to allow for systematic statistical analysis of the responses. The codes within the code frame represent a ‘theme’ based on an amalgamation of responses submitted and are intended to comprehensively represent all responses. The code frame and methodology, produced by Ipsos MORI, have been published alongside this report.

Overview of the responses

16) On the closure of the consultation on a potential UK-Australia trade deal, the Government had received 146,188 responses, submitted via the online survey and by email or post.

Table 1: A breakdown of the overall response numbers

| Method of response | Number of responses received |

|---|---|

| Online survey responses | 2199 [footnote 9] |

| Post | 1 |

| Emails (non-campaign) | 63 |

| Emails (campaign) | 145,905 |

| Total | 146,188 |

17) Respondents were categorised into one of the following 5 groups:

-

An individual - Responding with personal views, rather than as an official representative of a business, business association or another organisation.

-

Business - Responding in an official capacity representing the views of an individual business.

-

Business association - Responding in an official capacity representing the views of a business representative organisation or trade association.

-

Non-governmental organisation (NGO) - Responding in an official capacity as the representative of a non-governmental organisation, trade union, academic institution or another organisation.

-

Public sector body - Responding in an official capacity as a representative of a local government organisation, public service provider, or another public sector body in the UK or elsewhere.

Online consultation portal

18) The Consultation Portal was hosted by Citizen Space (an online software tool) and contained an online survey with a total of 67 questions. This was tailored to each of the 5 respondent groups with additional questions for certain groups. The survey for each group asked what areas of an FTA respondents viewed as being priorities and concerns and offered respondents the opportunity to select from across 14 trade policy areas relevant to an FTA. Respondents were also given the opportunity to submit supplementary comments and to raise any other issues. In addition, business respondents and business organisations were asked to select their top priority area and top concern. Respondents could simply answer the online survey questions selecting from the 15 options for priorities and concerns with textboxes available for additional comments. While many respondents chose not to submit additional comments after filling in the questionnaire, these responses are still subject to the same analysis and will be taken into account in developing our policy.

19) Of the 67 questions, there were 5 general questions for all respondents to answer, 11 specific questions for individuals, 10 specific questions for NGOs, 17 questions for businesses, 15 specific questions for business associations and 9 specific questions for public sector bodies. See annex A for the full list of questions asked.

20) Table 2 shows a breakdown of the number of Consultation Portal responses per respondent group.

Table 2: Total Consultation Portal responses broken down by respondent group

| Respondent group | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Individual | 117 |

| Non-governmental organisation (NGO) | 27 |

| Business | 34 |

| Business association | 34 |

| Public sector body | 7 |

| Total | 219 |

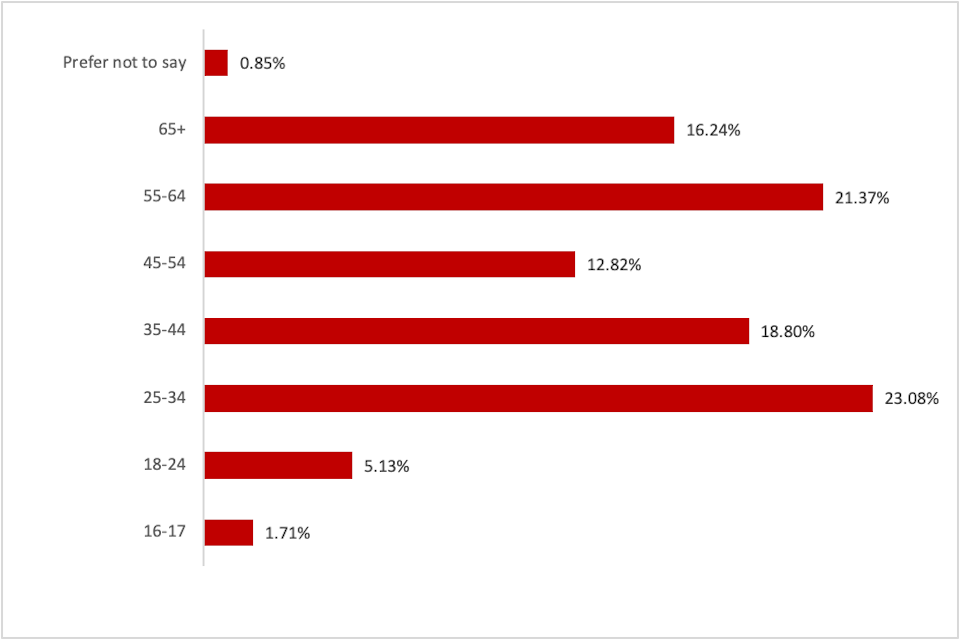

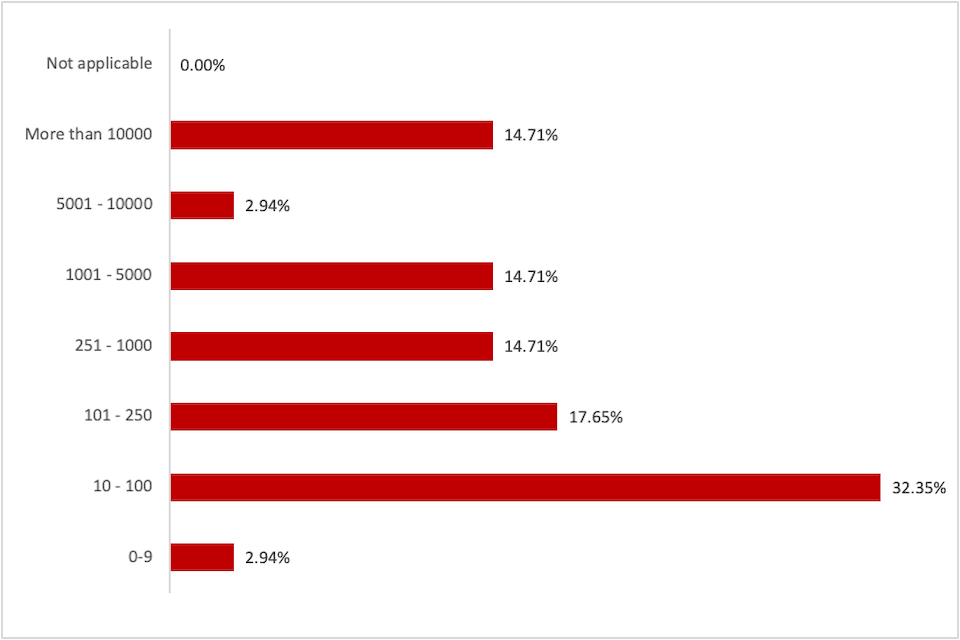

Respondents’ demographic profile

21) The online survey gave respondents the option to provide additional data about themselves or their organisation. This included questions such as their geographical location, age, gender, size of business and the number of businesses the business associations represent. Using this data, we have provided a detailed breakdown of respondents’ profiles in annex B.

Responses via email and post

22) Some respondents opted to submit their responses to the consultation via email. On request, questions from the Consultation Portal survey were made available to respondents. In this case, the majority of respondents submitted a letter with specific comments tailored to the needs and circumstances of their organisation. The table below (see table 3) shows a breakdown of the number of responses by respondent group. Over two thirds of the responses sent via email were from business and industry.

Table 3: Total number of email responses broken down by respondent group

| Respondent group | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Individual | 5 |

| Non-governmental organisation (NGO) | 12 |

| Business | 5 |

| Business association | 35 |

| Public sector body | 6 |

| Total | 63 |

23) One response was submitted by post from an NGO.

Campaign responses

24) A campaigning group (38 Degrees) organised and actively encouraged responses from its members to the consultation. Nearly 150,000 responses were submitted.

Table 4: Breakdown of the number of campaign responses

Campaigning organisation: 38 Degrees

Number of responses: 145,905

Title of campaign: Submission to DIT’s consultation on future trade deals

25) We have not categorised responses in any way other than how they were received. In the summary of responses section of this document, which summarises the detailed comments received by respondents, responses have been considered in the relevant policy area where they would be in a typical FTA.

Consultation feedback

Consultation events

26) As part of DIT’s work to promote all 4 consultations, we held 12 ‘town hall’ and roundtable events across the UK, seeking views from a broad range of stakeholders. Additionally, the Minister of State for Trade Policy, George Hollingbery MP, chaired a webinar (openly advertised on Twitter) with over 100 people registering. The webinar was specifically designed to discuss FTAs with specific relevance to how small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) operate.

Table 5: Location, date and partner organisation of each event

| Location | Date | Partner organisation |

|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | 5 September 2018 | The Scottish Council for Development and Industry |

| Manchester | 21 September 2018 | British American Business |

| Exeter | 28 September 2018 | Confederation of British Industry |

| Birmingham | 1 October 2018 | British American Business |

| Norwich | 3 October 2018 | Confederation of British Industry |

| Belfast | 4 October 2018 | Invest Northern Ireland |

| London | 5 October 2018 | Confederation of British Industry |

| Nottingham | 8 October 2018 | Geldards |

| Durham | 10 October 2018 | British Chambers of Commerce |

| Leeds | 12 October 2018 | Trades Union Congress |

| Cardiff | 15 October 2018 | British Chambers of Commerce |

| Reading | 17 October 2018 | Federation of Small Businesses |

| Webinar | 22 October 2018 | Federation of Small Businesses |

27) The events were intended to encourage individuals and businesses from all parts of the UK to participate in the consultations. We partnered with leading business associations and other representative organisations to host these events with each event adapting to meet the needs and interests of the registered attendees. In total, there were over 300 attendees with a broad spectrum of trade policy interests.

28) The events were chaired by either the Secretary of State, a minister or a senior official from DIT. Leading country and policy team experts from the department were also available to answer questions. These events allowed us to hear first-hand from a range of experts from across business, trade unions, NGOs, consumer groups and other civil society representatives. Events were held under the Chatham House Rule, with comments not attributed to stakeholders. This facilitated an open and honest discussion. Feedback from attendees was positive with the events being reported as informative and valuable.

29) From these events, we gathered the following feedback to all 4 consultations:

- appetite for engagement was high. Stakeholders valued the opportunity for a genuine dialogue with ministers and senior officials, an opportunity to exchange views, gather information and to be involved in the policy-making process

- stakeholders welcomed the government’s commitment to an inclusive and transparent trade policy and asked for this transparency to continue throughout the negotiation process. They requested more digital content on trade to be made available, and for the Department to signpost main issues to assist them accessing pertinent information

- levels of general knowledge of FTAs were mixed

- many businesses were engaged but were open about the fact that the FEP with the EU and EU-Exit contingency planning was their main focus. This was consistently seen as the more immediate priority for business

30) Understanding of FTAs varied across different stakeholder groups, with there being mixed levels of awareness about the impact of trade deals and their wider benefits to the general public. DIT recognises the need to raise awareness of future FTAs and their impact at both local and national level. The insights gained from these events will inform DIT’s stakeholder engagement plans for any future stakeholder consultation exercises and for any future engagement during potential trade negotiations. The government will continue to build upon its commitment to deliver an informed, inclusive and transparent trade policy.

Engagement with devolved administrations, Crown dependencies and overseas territories

31) As set out in the Trade White Paper Preparing for our future UK trade policy the government is committed to ensuring the devolved administrations (DAs) have a meaningful role in trade policy after we leave the EU. To develop and deliver a UK trade policy that benefits businesses, workers and consumers across the whole of the UK we will take into account the individual circumstances of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Working closely with the devolved administrations to deliver an approach that works for the whole of the UK continues to be a priority for DIT.

32) During the consultation, we took steps to engage widely in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, including holding round tables in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast.

33) The Scottish and Welsh governments have provided views on the potential UK-Australia FTA via written responses and during discussion with DIT ministers and officials. We welcome and thank both governments for these views.

34) The Northern Ireland Civil Service has published technical data in relation to Australia and trade and discussed this data with DIT officials. We thank them for this information.

35) DIT will continue to actively engage with the devolved administrations regarding any new potential trade deal with Australia through a new DIT/DA Ministerial Forum and our regular Senior Officials Group and policy roundtables.

36) We recognise the interest in potential UK FTAs from the Crown dependencies and overseas territories, including Gibraltar, and remain fully committed to engaging them as we develop our independent trade policy for the UK. The Secretary of State for International Trade made this commitment clear in his letter to the chief ministers of the Crown dependencies (and overseas territories) at the launch of the consultations in July 2018. Discussions between DIT and the Crown dependencies continue on a range of trade policy topics.

37) We will continue to seek views from the Crown dependencies and overseas territories, including Gibraltar, during any potential future FTA negotiations to ensure that their interests and priorities are properly taken into account.

Engagement with Parliament

38) The government is committed to providing Parliament with the ability to inform and scrutinise new trade agreements as we progress with developing our future trade policy. The Secretary of State for International Trade, Minister of State for Trade Policy and the government’s Chief Trade Negotiation Adviser held a briefing session on the FTA consultations, open to all Members of Parliament (MPs), on 12 September 2018. Twenty-four MPs attended, and the questions were-wide ranging, covering all 4 consultations. Comments sent to DIT by MPs on behalf of their constituents were also considered as part of our analysis of the consultation feedback. The House of Commons International Trade Committee also published a report on UK-US Trade Relations, to which the government responded on 10 July 2018. We will consider the committee’s conclusions from its inquiry on Trade and the Commonwealth: Australia and New Zealand.

39) On 21 February 2019 there was a debate in government time in the House of Commons on the 4 potential new FTAs. The purpose of this was to help the government to understand parliamentarians’ priorities for the new FTAs before formulating our negotiating objectives.

40) On 28 February 2019 we published a paper, Processes for making a free trade agreement after the United Kingdom has left the European Union, which sets out proposals on public transparency for future FTAs and the role of Parliament and the devolved administrations. This included confirmation that at the start of negotiations, the government will publish its outline approach, which will include our negotiating objectives, and an accompanying scoping assessment, setting out the potential economic impacts of any agreement. The government stands by its commitment to ensure that Parliament has a role in scrutinising these documents so that we can widen the range of voices heard and ensure that as many views as possible are taken into account before commencing negotiations.

41) The government plans to draw on the expertise and experience of Parliamentarians throughout negotiations, working closely with a specific parliamentary committee, or alternatively one in each House. We envisage that the committee would have access to sensitive information that is not suitable for wider publication and could receive private briefings from negotiating teams. This would ensure that the committee(s) was able to follow negotiations closely, provide views throughout the process and take a comprehensive and informed position on the final agreement.

Summary of responses

General themes

Respondents across all stakeholder groups provided a wide range of comments on their priorities and concerns regarding a future UK-Australia FTA. More detailed analysis can be found in the ‘analysis of responses by policy area’ section. The summary below sets out the key themes raised within the 5 policy areas which received the greatest volume of substantive comments. We also received a large volume of campaign responses, not all of which included individual comments. These are summarised in the ‘summary of campaign responses’ later in this document.

The UK’s existing labour standards and environmental protections should not be reduced or negatively impacted by any future FTA with Australia

Across all stakeholder groups, respondents raised the importance of maintaining the UK’s high labour and environmental standards. It was felt that a UK-Australia FTA should protect workers’ rights and should not adversely impact wages or job security. Respondents also reflected that increased trade generated by an FTA could contribute to climate change through additional transport activity and carbon emissions. Respondents reflected that an FTA provided an opportunity to ensure that the levels of protection and standards for both countries were aligned to the highest level.

There could be benefits to the UK from lowering or removing tariffs with Australia, but there may be some industries that would be best supported by maintaining existing tariffs

A number of comments focused on the potential benefits of reducing or removing tariffs between the UK and Australia. The perception was that this could further enhance trade between both countries and that it should be a key priority for a future FTA, as long as Australia did not stand to benefit more than the UK. Stakeholders stressed the importance of protecting some sectors by maintaining existing tariffs. In particular, respondents highlighted concerns that a reduction in tariffs (and an FTA more broadly) could have on certain sectors such as agriculture. It was recommended by some stakeholders that tariffs should be maintained in these sectors or reduced over time to manage any negative impacts to UK industries.

Any UK-Australia FTA should ensure a level playing field for UK businesses

Respondents highlighted that an FTA could increase competitiveness for UK products and ensure a fairer and level playing field for businesses operating in Australia. However, many stakeholders emphasised the importance of ensuring that an FTA did not negatively impact UK producers and businesses by exposing them to increased competition. Any reductions in standards through an FTA were seen as having the potential to make UK businesses more vulnerable to unfair competition. Stakeholders also highlighted the need to protect UK businesses from practices that were perceived as being unfair, such as undercutting producers by flooding the market with cheap imports.

The UK’s existing product standards should be maintained through any future UK-Australia FTA

Stakeholders identified the importance of ensuring the UK’s high product standards were not reduced or compromised through an FTA with Australia. Some recommended that standards should continue to align with those applied in the EU, and that standards should be harmonised across all future trading partners to reduce bureaucracy and ensure quality and consumer safety. Respondents stressed the importance of reducing the regulatory and administrative burden of product certification (particularly on SMEs), while balancing this against retaining high standards.

A future UK-Australia FTA could have a beneficial impact on services trade between both countries

Respondents highlighted the opportunities that an FTA could provide in terms of increasing services trade between both countries. Mutual recognition of professional qualifications (MRPQs), and inclusion of provisions to support greater movement of skilled workers between both countries were identified as having the potential to benefit trade. Respondents also highlighted that areas such as digital and financial services should form part of an FTA, noting these were areas of comparative strength for both countries. Concerns focused on ensuring that Australia did not stand to benefit more than the UK from any services provisions.

Other main themes

In addition to the above, a number of key themes were reiterated through the comments received through the consultation. A significant number of stakeholders raised the importance of protecting public services, with particular reference to the National Health Service (NHS). This was mirrored in the responses received through the 38 Degrees organised campaign. The government has made its position clear that decisions about public services will continue to be made by UK governments, including the devolved administrations, and not future trade partners.

Other key messages included requesting that the UK maintain the UK’s high food and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures with concerns focused on the potential negative impacts on consumers of lowering food and SPS standards. In addition, stakeholders raised the importance of protecting the UK’s Intellectual Property (IP) through any future UK-Australia FTA and ensuring that more widely, FTA provisions helped reduce the administrative and financial burdens of trade between both countries.

Stakeholders were positive about the potential for a UK-Australia FTA but highlighted that it should not compromise or negatively impact on the FEP with the EU.

Overview of priorities

Respondents who completed their consultation response via the online survey, were classified into different respondent groups (individual, NGO, business, business association and public sector body) and asked a series of questions (set out in annex A).

All respondent groups were asked what they wanted the UK government to achieve through a UK-Australia trade agreement and which of the 14 policy areas provided (as set out below) best described the priorities outlined in their previous answer. Business and business association respondents were also asked what they wanted the UK government to achieve by reference to the 14 policy areas, and were provided with a supplementary question, asking which of these policy areas is their top priority.

The table below shows the top 3 policy areas selected as a priority for each of the different respondent groups.

Table 6: Top priorities selected by different respondent groups

| Type of respondent (total number) | First most selected priority (total selected by) | Second most selected priority (total selected by) | Third most selected priority (total selected by) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals (114) | Product standards, regulation and certification (70) | Tariffs (69) | Customs procedures (63) |

| Businesses (32) | Tariffs (10) | Services (7) | Trade remedies and dispute settlement (4) |

| Business associations (31) | Tariffs (10) | Product standards, regulation and certification (5) | Services (5) |

| NGOs (26) | Tariffs (17) | Product standards, regulation and certification (14) | Labour and environment (14) |

| Public sector bodies (6) | Tariffs (4) | Competition/Investment (3) | Sanitary and phytosanitary measures (3) |

Overview of concerns

All respondent groups were asked what concerns they had about a UK-Australia trade agreement and which of the 14 policy areas provided (as set out below) best described the concerns outlined in their previous answer.

Business and business association respondents were also asked about their concerns by reference to the 14 policy areas, and were provided with a supplementary question, asking which of these policy areas was their top concern.

The table below shows the top 3 policy areas selected as a concern for each of the different respondent groups.

Table 7: Top concerns selected by different respondent groups

| Type of respondent (Total number) | First most selected concern (Total selected by) | Second most selected concern (Total selected by) | Third most selected concern (Total selected by) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individuals (88) | Product standards, regulation and certification (44) | Labour and environment (37) | Tariffs (36) |

| Businesses (27) | Services (8) | Tariffs (6) | Digital (3) |

| BusinessAssociations (27) | Tariffs (7) | Services (7) | N/A |

| NGOs (25) | Product standards, regulation and certification (13) | Tariffs (13) | Sanitary and phytosanitary measures/intellectual property (11) |

| Public sector bodies (5) | Tariffs/Competition (3) | Product standards, regulation and certification/labour and environment (2) | Sanitary and phytosanitary measures/rules of origin (2) |

Analysis of responses by policy area

This section contains a detailed analysis of the free text comments submitted. The feedback has been summarised with reference to the 14 policy areas and other comments provided and grouped by respondent type:

- Individuals

- Businesses

- Business associations

- NGOs

- Public sector bodies.

Please note that where respondent feedback from across these different groups reflected similar views, comments or issues highlighted might overlap. Technical terms can be found in the glossary located in annex C.

Tariffs

Overall, respondents were positive about the potential benefits of a trade agreement with Australia. There was a strong preference for either lower tariffs or their complete removal, with businesses explaining how they could benefit from this and the resulting increased trade between the UK and Australia. However, the need for protection of the UK market was also highlighted in many responses. A few respondents, notably from the agricultural food sector, stressed the importance of maintaining certain tariffs or reducing them gradually over time to protect UK producers’ and farmers’ livelihoods.

Individuals

Thirty-one individual respondents prioritised tariffs in their comments with the main message being that the reduction or removal of tariffs should be a key priority for an FTA with Australia. Some individuals highlighted the importance of reducing both tariffs and non-tariff barriers to facilitate trade and promote increased trade flows between the UK and Australia. Eighteen individuals called for an FTA without any tariffs on goods. However, 3 individuals flagged concerns, including the need for the UK not to diverge from existing EU tariffs and standards given the EU is the UK’s biggest market. There was also concern expressed about future FTA provisions, including those on tariffs, being more beneficial to Australia.

Businesses

Twenty-four businesses asked for the UK government to prioritise tariffs in a future FTA with Australia. Eleven businesses called for the removal or reduction of tariffs, citing the opportunities this could bring from increased trade between both countries, with one respondent noting that promoting electronic commerce (e-commerce) could be one such opportunity. Responses included requests for reductions on specific tariffs, such as for grain, or their removal for products such as raw cane sugar and wine. Many respondents called for any changes to tariffs to be fair to both the UK and Australia and not negatively impact UK industries or agriculture. A need to respect the WTO Pharmaceutical Tariff Elimination Agreement was also raised (to note, Australia is already a participant). Some respondents asked for any future trade negotiation to aim for trade liberalisation for all products manufactured by the life sciences industry. Seven businesses expressed general concerns, with one commenting specifically about the potential significant impact on the affordability of UK products and competitiveness. There were concerns about whether the outcome of negotiations between the UK and Australia would be fair and equal.

Business Associations

Forty-five business associations raised tariffs as a priority in their comments and welcomed the removal or reduction of tariffs which could greatly benefit particular UK industries, for example, cosmetics, spirits, books, journals and newsprints. Representatives of the Scottish salmon sector also indicated support for removal of tariff rate quotas (TRQs). One respondent highlighted the potential benefits for the automotive sector of removing of Australian automotive tariffs. However, there was a wider recognition that in some cases reducing or removing tariffs might increase competition faced by UK business or reduce benefits from tariff preferences granted to developing countries. Twenty-six business associations raised concerns about tariffs which included points about the affordability of high shipping costs between UK and Australia singled out for comment.

NGOs

Fifteen NGO respondents raised tariffs as a priority in their comments. Responses highlighted potential benefits from a reduction of tariffs. Ensuring that exceptions were available for agricultural food products was also highlighted by respondents as being a priority. A few respondents favoured the reduction or removal of tariffs and TRQs. Seeking improved terms of trade for products manufactured or designed in the UK (such as in the textile industry) was also flagged as being important. Eleven NGOs highlighted concerns around the impact of tariff reduction on UK businesses. Comments included the need to consider how this might interact with domestic reforms, such as the withdrawal from the EU Common Agriculture Policy.

Public sector bodies

Six public sector bodies referenced tariffs as being a priority in their comments and 4 as a concern. Responses tended to focus more on non-tariff barriers and one respondent was of the view that given Australia currently does not impose tariffs on certain products (like most seafood) any tariff reductions negotiated in an FTA would not significantly improve the terms of trade for UK exporters.

Rules of origin (RoO)

Respondents, particularly businesses and business associations, tended to highlight the importance of RoO for current global supply chains, including those involving the EU. A common theme among business association respondents, who expressed views on behalf of their members, was to call for further simplification and support in understanding RoO. Comments were also raised by respondents in this section on geographical indications (GIs) however, in an FTA, GIs are contained within the IP chapter and therefore have been considered in that section.

Individuals

Individuals did not specifically raise RoO as either a priority or a concern in their comments. However, a comment was raised calling for RoO, as well as market access and regulatory aspects of trade policy, to be designed to facilitate trade and not impede it. The impact that changing RoO may have on the quality of imported products was noted as a concern.

Businesses

Fourteen businesses raised RoO as being a priority in their comments, and 5 identified it as being a concern. On content requirements, one responding business, based on its experience in extractive and metal industries, recommended using the regional value content (RVC) approach as the most effective way of determining product specific RoO. Some business respondents recommended allowing products to benefit from diagonal cumulation with the EU, along with calls to simplify and harmonise RoO. Ensuring the similarity of RoO to be applied in future UK FTAs with those already agreed in EU FTAs, was flagged as being important in reducing administrative burdens. One business, with global supply chains, was concerned that products developed in the UK might not be considered in the future as originating in the UK due to components coming from overseas and being sourced from within the supply chain.

Business associations

Thirty-two business associations referenced RoO as being a priority for a UK-Australia FTA and 19 viewed it as a concern. Due to the importance of their global supply chains, some business associations highlighted that some of their members would not be able to meet restrictive RoO requirements. As a result, business associations requested alternative requirements for determining origin which were more reflective of global supply chains. Seven respondents suggested diagonal cumulation with the EU or other countries, seeking RoO that were compatible with the future EU-UK relationship, or replicating EU-standard preferential RoO.

Eight business associations called for simplifying or minimising the administrative burden of RoO. Suggestions included self-certification, use of electronic preferential origin documentation and certification, trusted trader relationships and standard rules between major trading blocs. Other respondents sought greater flexibility for imports to the UK market and highlighted vulnerability to dumping, with some respondents suggesting a link between RoO and dumping practices. One respondent included a need for tight, well-defined RoO to avoid circumvention. They suggested the change of tariff heading as being a preferred approach or, in certain cases, the use of regional content thresholds of more than 50%.

NGOs

Three NGOs referenced RoO as being their priority in their comments, and two identified it as a concern. One respondent suggested that RoO cumulation requirements between the UK and Australia, as well as other developed countries, should be set at 25%, which they regarded as being a world-leading liberal standard and highlighted as being well below the lowest threshold set in CPTPP - namely originating materials representing at least 30% of the value of goods - and thresholds set in other trade agreements.

Public sector bodies

Public sector bodies did not specifically raise RoO as either a priority or a concern in their comments, although a concern was raised over the potential impact of removing current regulations on RoO.

Customs procedures

Most of the comments raised by respondents focused on the need to have efficient and cost effective customs procedures in place to ensure that they do not impose an administrative or financial burden for economic operators, notably SMEs, and do not interfere with the operation of many industries, for example, those which work based on supply chains and ‘just in time’ deliveries.

Individuals

Three individual respondents raised custom procedures as a priority in their comments. Responses focused on the need to keep the administrative burden as low as possible (particularly for small exporting businesses) to make trade with Australia as easy and frictionless as possible. Respondents suggested we look towards similar customs procedures as currently applicable in trade between Australia and the EU. One respondent suggested that new technology, such as a blockchain ledger, could be introduced to record and enhance trade in goods between Australia and the UK by reducing the need for customs intermediaries. Two individuals marked customs procedures as a concern, with the need to reduce ‘red tape’ being mentioned repeatedly.

Businesses

Twenty-one business respondents viewed customs procedures as a priority in an FTA with Australia. Most comments related to minimising the regulatory burden with requests to improve the overall speed of custom clearances and to keep paperwork minimal. Suggestions included using the Integrated Cargo System or another electronic/online system. Several respondents called for customs-related requirements to be reduced, eg limited to certification proving origin, specifically for food. Respondents also made reference to the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, which contains provisions for effective co-operation between customs and other appropriate authorities on trade facilitation and customs compliance issues. The recommendation was to build on this agreement by standardising approaches to customs legislation to give certainty to traders. A concern expressed by some Australian wine producers was the effect of possible queues and delays at borders and ports in the UK once the UK has left the EU, given the UK is currently the central European hub for the flow of Australian wine exports moving across Europe. Seven business respondents raised customs procedures as a concern. Comments included the effect on ‘just in time’ supply chains once the UK has left the EU with the potential for delays in obtaining or transferring component parts to and from overseas leading to high levels of storage and inefficiencies.

Business Associations

Twenty-five business associations called on the UK government to prioritise customs procedures in a future FTA with Australia and 18 raised concerns. As with businesses, reducing bureaucracy and costs were the main recommendations made by business associations. These included the potential impact on electronic transfer of data, checks carried out in transit to avoid delays in ports, as well as investment in infrastructure of ports and airports to ensure effective handling of merchandise. Respondents also raised the issue of disproportionate costs and burdens for SMEs, suggesting customs procedures should be effective, but ‘light touch’. The frequency of changes in Australian regulations was also raised as an issue as they require manufacturers to frequently adjust information on the product or in the export documents. One respondent referred to the need for valuation and transfer pricing policies that are consistent with Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) guidelines.

NGOs

Four NGOs raised customs procedures as a priority with the focus on minimising administrative burdens for UK businesses trading with Australia. One respondent emphasised the benefits that trade facilitation measures could bring about for business thus leading to enhanced levels of economic activity. One NGO asked for robust customs procedures to be maintained for agricultural produce entering the UK from Australia. Five NGOs raised concerns, including anti-business customs practices, which could lead to costly customs delays. Moreover, the issues of import duties and border Value Added Tax (VAT), VAT payment systems, trade finance (including letters of credit), and marine, aviation and transport insurance and reinsurance were raised.

Public sector bodies

No public sector bodies commented on customs procedures as a priority or a concern in their feedback.

Services

Respondents recognised the importance of services in trade agreements, covering several sectors including professional and financial services. Feedback was largely sector specific with comments relating to particular requirements for those industries. For financial services, respondents covered a broad range of sub-sectors which included asset management, banking, insurance, financial technology (FinTech), green finance and infrastructure finance. The importance of MRPQs was referenced. Respondents also emphasised the need for FTAs which prioritised the movement of skilled workers, allowing businesses access to the best talent. Relevant comments on public services, including the NHS, were also raised in the consultation sections on investment and government procurement but have been considered in this section.

Individuals

Thirteen individuals viewed services as a priority for a future FTA with Australia, and 5 raised concerns. Generally, individuals’ views on an FTA with Australia were positive, with many pointing to historic and cultural links between the two countries. Many individuals identified greater MRPQs and a reciprocal streamlined visa system as being their priority, with respondents calling for movement of professionals and workers between Australia and UK to be prioritised. One respondent stated that they would like to see the UK join the Trans-Tasman Travel Arrangement (TTTA) which could facilitate intra-company transfers in areas of mutual benefit to both economies. Some respondents emphasised they did not want any future FTA to negatively impact existing public services, specifically the NHS. Similar concerns were raised about the perceived threat to NHS services from private healthcare companies if public services were liberalised in a UK-Australia FTA. The impact of distance on trading services with Australia was also perceived by some individuals as being a potential issue.

Businesses

Twelve businesses referenced services trade, particularly professional and financial services, as a priority and identified a preference for MRPQs to be included in a future FTA with Australia and the need for the flexibility to recruit overseas staff and for staff temporarily moving to work overseas. One business specifically highlighted the need for measures enabling the temporary movement of workers and professionals for business reasons, while other businesses highlighted the need for measures reducing visa fees, minimising experience thresholds for intercompany transfers and extending the Australian skilled occupations visa eligibility list. Business respondents who called for an FTA to prioritise the movement of highly skilled professionals in order to enable their global business networks to grow, emphasised the heavy reliance that businesses have on cross border activity and movement.

For financial services, both business and business associations had a particular interest in supervisory and regulatory co-operation, highlighting the opportunities for the asset management sector, including streamlining of regulatory reporting, mutual recognition, and the example of the Asia region funds passport. Several businesses stated that a key priority for a UK-Australia FTA was maintaining access to both countries market insurance and reinsurance businesses through cross-border trade and establishment. Several respondents identified that they would like to see the removal of restrictions in relation to retail, banking and insurance. These respondents also called for the UK to use its expertise as a leading hub for green finance to cooperate with Australia’s similar expertise. Recognition of licences and certificates and harmonisation of regulations were also identified as priorities across several sectors. In total 8 businesses expressed concerns on trade in services, with several respondents remarking that an FTA could not benefit the UK as much as Australia, with regards to trade in services.

Business associations

Twenty-two business associations viewed trade in services as a priority in their comments. Business associations also wanted financial services to be at the forefront of policy development for the future trading relationship with Australia, with particular interest in closer regulatory cooperation. One respondent identified that Australia has invested over £1.8 billion (as of 2016) in UK financial services and is the second largest investor in the UK’s insurance sector.

Some respondents stressed that trade in services is particularly important to SMEs seeking to export services and called for the inclusion of tailored SME provisions in a services chapter of an FTA. There was also a request for an FTA to liberalise the movement of skilled workers and MRPQs and to see the implementation of the Customs Declaration Services, which could ease the administrative burden on SMEs when exporting. It was noted by one business association that minimising the bureaucracy of visa applications provides an opportunity for the UK, as they felt the UK is currently losing out on Australian business ventures to the US due to UK visa restrictions on highly qualified personnel. Ten business associations raised concerns about a potential UKAustralia FTA, with a recurring concern about dispute settlement mechanisms in a potential FTA and encouraged the UK government to consult industry and civil society.

NGOs

Thirteen NGOs viewed trade in services as a priority, with several respondents calling for the frictionless movement of services. Some NGOs called for the inclusion of MRPQs in a services chapter of a potential UK-Australia FTA, including certificates and licences. Some NGOs saw the greatest opportunity for increased trade flows to be trade in services, with one stating that the difference in time zones is beneficial as services and support can be provided from various offices and across time zones, boosting the globalised services industry. NGO respondents also commented that the UK is a leader in financial services and called for the UK’s high regulatory requirements to be protected. Thirteen NGOs raised concerns on a number of services related issues, including ISDS and a lack of transparency in any potential negotiations. One NGO raised concerns around the limited role of the devolved administrations stating that any future trade agreement may affect devolved matters. Respondents also commented on the importance of protecting public services, including the NHS.

Public sector bodies

Five public sector bodies asked the UK government to prioritise trade in services, with two raising concerns. Many respondents were keen for a bilateral FTA with Australia, noting the ease by which financial and related professional services could do business and use expertise in the region and that UK businesses could expand in this market. Public sector body respondents also highlighted the need to ensure free movement of skilled workers between Australia and the UK. Comments also referenced the value in harmonising services standards. Several public sector bodies also identified the benefits of free movement of financial services employees and welcomed strong financial services elements in any future FTA. Respondents also identified that cross-border trade in financial services supports competition across financial markets and provides a wide range of choice to customers. One respondent identified that in 2017, the UK exported £832 million of financial services to Australia, up from £814 million in 2016.

Public sector bodies expressed concerns that an FTA could potentially lead to the privatisation of public services. One public sector body called for the uncertainties and timeframes surrounding visa applications to be addressed, flagging the benefits that reciprocal business visas could bring to both the Australian and UK businesses and markets. There was also a comment about excluding public services, including the NHS, from the scope of FTAs.

Digital

A recurring theme of the feedback was the need for free flow of data, with respondents highlighting the importance of effective data protection and the need to prevent data localisation. There was general support for global rather than national responses to the tax challenges of digitisation and for rules on digital goods not being a barrier to trade. With regards to telecommunications respondents, many respondents wanted to enhance non-discrimination clauses to protect net neutrality and ensure better market competition. Some respondents also used the consultation as an opportunity to express their opposition to any changes to current EU platform liability rules.

Many respondents were of the view that Australian businesses can already access the UK’s audio-visual (AV) market. A number of respondents focused on how an FTA might adversely affect the UK’s AV ecosystem, with one respondent making particular reference to the positive impact of the UK’s Public Service Broadcasting (PSB) system to the success of UK businesses abroad. Some respondents were also of the view that advertising time is discriminatory against non-Australian content, and that media businesses are subject to foreign ownership restrictions.

Respondents from the newspaper industry called for there to be no unjustified restrictions on the cross-border publication dissemination of UK newspapers, in print and online, or news brands subscriptions and advertising services. Responses from the gaming sector were positive, emphasising the need to maintain frictionless trade and break down barriers where these existed with trading partners.

Individuals

Three individuals raised digital as a priority in their comments and two raised it as a concern. Comments included enforcing every party’s right to regulate data in the national interest to protect privacy. The opportunity to enable content to be shared between Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) and the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) to help counter use of virtual private networks (VPN) and illegal torrenting was also flagged by one respondent. One respondent perceived data and privacy protections to be weaker in Australia.

Businesses

Thirteen businesses prioritised digital in a UK-Australia FTA and 9 raised digital as a concern. Businesses called for alignment of digital regulatory requirements across future UK FTAs, including through reference to internationally accepted standards (for example, one respondent called for alignment with Information Commissioner Office (ICO) guidelines on big data), as well as mutually recognised standards. Three businesses commented that it is important to ensure free flow of data and two businesses raised the control of data movements across borders as being particularly important. Data protection and privacy were also key concerns for 3 businesses.

Business Associations

Fourteen business associations referenced digital as a priority while 15 identified this area as a concern. Business associations called for several areas to be covered in a UK-Australia FTA. These included calls for the UK’s Enterprise Act to form a part of a future FTA and for it to reflect the Digital Economy Act of 2017 for user data. There were also requests for the FTA to align with the ICO guidelines on big data; for a data sharing agreement with Australia; and calls for cooperation on data ethics and artificial intelligence (AI). Four business associations mentioned the importance of ensuring that an FTA with Australia does not have compulsory data localisation. Data protection and privacy was a concern for 6 respondents. Some respondents asked for the government to consult at a detailed sectoral level throughout the negotiation process.

NGOs

Three NGOs viewed digital as being a priority and 2 NGO respondents referenced this area as a concern in their comments. Two NGOs raised the importance of maintaining current arrangements with the EU on digital trade policies. NGOs also wanted a UK-Australia FTA to ensure the free flow of data, aligning data protection regulations and prioritising economic growth. One NGO recommended ensuring digital trade remains untaxed and that provisions should be included to stop governments from imposing requirements that restrict digital services. The need to enforce data privacy obligations to ensure that data flows as smoothly as possible was also commented upon.

Public sector bodies

Three public bodies prioritised digital in their comments, with no public sector bodies raising concerns in their response. One respondent suggested that cyber security could be a potential market for UK businesses in Australia. Two public sector bodies mentioned the importance of increasing co-operation and partnership in the digital economy.

Product standards, regulation and certification

This policy area covers technical regulations, voluntary product standards and the procedures to ensure that these are met. Standards and measures to protect humans, animals and plants as well as to regulate food, animal and plant safety are discussed under the SPS section of this document.

The terms ‘standards’ and ‘technical regulations’ are used frequently in trade agreements when addressing ‘technical barriers to trade’. While the word ‘standard’ is used informally to mean a level of quality or attainment, in the context of trade agreements ‘standards’ have a formal technical meaning. ‘Standards’ in this sense are voluntary documents developed through consultation and consensus which describe a way of, for example, making a product, managing a process, or delivering a service. While standards are voluntary, when cited in a regulation, their use can become compulsory. Standards are not set or controlled by the government. ‘Technical regulations’ are mandatory requirements set out in the legislation and they are controlled by governments and legislators (Parliament in the UK). For regulated products and services, standards can be used to support compliance.

A significant number of responses focused on product standards, regulation and certification with a need to maintain current high standards and continue to align UK standards and regulations with those applicable in the EU. There were a number of in-depth sector specific responses focusing on regulatory frameworks and potential sectoral annexes to the future FTA. Relevant comments regarding standards that were raised in the consultation section on labour and environment have been considered in this section.

Individuals

Seventeen individual respondents viewed product standards, regulation and certification as a priority and 9 as a concern. Several respondents asked for existing regulations for products and consumer rights to be maintained or improved to ensure a high level of quality and safety. Some respondents also commented on harmonising arrangements between trading partners, either through aligned standards or aligned certification. The most frequently raised concern was in relation to the impact of lowering standards and levels of protection which might result from trade liberalisation and increased trade flows with Australia. This included concerns about the potential impact from low quality imported goods and the potential for reduced control over what could be imported into the UK.

Businesses

Fifteen businesses referenced standards in their comments as being a priority in a future trade agreement with Australia, with an emphasis placed on maintaining current UK standards and aligning with the EU. A key focus was on the need for mutual recognition of conformity assessments, regulatory co-operation with Australia and alignment of future FTA provisions to EU FTAs. Some respondents also stressed the benefits of mutual recognition agreements (MRAs). This allows states to officially recognise the results of inspections and tests conducted in another state as being equal to their own inspections and testing. As such MRAs are perceived to reduce administrative burdens, time delays and costs, eg the need to re-test imports or exports. In this context, they noted that the UK currently benefits from the EU-Australia MRA on conformity and called for this to continue after we leave the EU.

Respondents were also in favour of the UK being involved in international co-operation related to development of international standards which could be then applied by the UK and its partner countries. Some respondents supported greater co-operation towards recognition of the equivalence of applied technical regulations and standards to facilitate trade. One respondent was in favour of alignment between the quality mark of the British Standards Institution (Kitemark) with an Australian equivalent to facilitate marking and recognition of high-quality products which are safe for consumers. Three businesses expressed concerns which focused mainly on the need to prevent low quality imports that do not meet UK standards and regulations from entering the UK. There was also unease around the amount of regulation and bureaucracy connected with the adoption of national product standards and the effect of a lack of harmonisation with standards used internationally.

Business associations

Thirty-three business associations viewed product standards, regulation and certification as being a priority for a future FTA with Australia and 18 expressed concerns. Many respondents stressed a need for simplified procedures and reduced regulatory and administrative burden, particularly for SMEs. For example, through mutual recognition of inspection results, while at the same time balancing this with the need to maintain high standards, and not permit imported products which do not adhere to these. Some respondents also highlighted the importance of the UK remaining aligned with standards and regulations used in the EU. Continued alignment with standards and regulations used in the EU including co-operation with the European Medicines Agency (EMA) was flagged as a top priority for the pharmaceutical industry associations who responded.

Some respondents were also in favour of MRAs between the UK and Australia to facilitate trade. One respondent thought the UK government should seek, through the FTA, to strengthen cooperation with Australia on standards, technical regulations and conformity assessment procedures, with a view to increasing the mutual understanding of their respective systems and facilitating access to markets. It was suggested that regulatory dialogues could be established both at the horizontal and sectoral levels. The UK and Australia could exchange information, simplify technical regulations and conformity assessment requirements (when appropriate), as well as choose or refer to the most relevant standards in areas which might affect trade. Greater cooperation in the development of international standards, guidelines and recommendations was also supported. Specific detailed comments were made on standards and regulations covering the following sectors: publishing, cosmetics, automotive sector and food and drink. Respondents also flagged the challenges faced by SMEs in complying with technical regulations and standards in international trade. Others referenced benefits of the EU-Australia MRA.

NGOs

Eighteen NGOs prioritised standards, regulation and certification in a future trade agreement with Australia in their feedback. The main focus of the feedback was on maintaining or improving product standards and consumer protection rights. Other priorities included ensuring that standards applicable in the UK were adopted by all future trading partners and aligning standards with those used internationally. Fourteen NGOs raised concerns, focusing on changes in product standards impinging on consumer rights and protection and the possibility that importing lowquality goods might have a negative impact on standards more generally, through unfair competition and the ‘race to the bottom’.

Public sector bodies

Three public sector bodies prioritised standards, regulation and certification in their comments. All comments called for harmonisation or mutual recognition of standards with Australia, in technology and manufacturing sectors, as well as regarding medical devices, medicines and non-medical consumables. One public sector body respondent expressed concerns about the impact of changes to the environmental standards of production.

Sanitary and phytosanitary measures (SPS)

This policy area covers standards and measures to protect humans, animals and plants as well as to regulate food, animal and plant safety. Voluntary product standards and the procedures to ensure that these are met are discussed under the product standards, regulation and certification section of this document.

Responses generally centred around the need to maintain high UK food requirements and on SPS. Respondents also expressed concerns that the food standards may be lowered as a result of new trade agreements. Others highlighted a need to continue to align the standards and regulations with those applicable in the EU, as well as pointed to differences between the UK’s and Australia’s regulatory approach to “hormone beef” and antibiotics.

Individuals

Sixteen individuals viewed SPS as being a priority in a future FTA with Australia and 13 as a concern. A recurring theme in the feedback was the importance of not lowering or compromising on the UK’s current high food standards. Five respondents highlighted the need to maintain animal welfare standards. Several respondents focused on continuing to align SPS measures with those applicable in the EU. Many respondents emphasised the need to maintain effective border controls to prevent the spread of diseases, as well as imports of products related to processing practices or farming methods prohibited in the UK (such as “chlorine-washed chicken” and hormones) or subject to different regulation (genetically modified organisms (GMOs) and pesticides).

Businesses

Ten businesses identified SPS as being a priority and 4 as a concern in their comments. Responses focused on the importance of achieving equivalence in standards and regulations. One respondent suggested that tariffs should only be removed where overall SPS measures are materially equivalent. Some respondents within specific agricultural-food sectors also stressed that SPS measures should not be more stringent than those currently applied by the EU.

Business Associations

Twenty-two business associations referenced SPS measures as being a priority in their response and 18 as a concern. Several respondents advocated the use in an FTA with Australia of EU SPS measures recently agreed with third countries, as well as the continued alignment of UK standards with those applicable in the EU. Some respondents highlighted the importance of food safety regulation being risk-based, minimally burdensome and able to facilitate competition and innovation. There was also a call for the UK government to consider more carefully the impact on SMEs. Seven respondents emphasised the importance of maintaining and improving standards, including on animal welfare. One organisation expressed concern about a potential reduction of UK standards and the negative impact for domestic producers. Representatives of some sectors, such as cheese and meat (notably beef) highlighted difficulties in exporting these products to Australia on sanitary grounds. Respondents were of the view that the UK government should address these barriers in negotiations.

NGOs

Twelve NGOs referenced SPS as a priority in their comments and 16 as a concern. Many NGO respondents highlighted the importance of maintaining domestic food standards and the need to prevent the imports of lower quality food produce. Several NGO respondents focused on specific SPS concerns, notably hormone-growth in Australian beef and the negative impacts this may have on UK domestic production. The use of antibiotics in Australian farming practices was also raised with reference made to the UK’s official support for the UN World Health Organisation (WHO) Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) One Health Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) Strategy. The rates of food poisoning (notably salmonella) in Australia were also highlighted in a number of NGO responses. Here, the respondents linked high rates of food poisoning with lower standards of animal welfare. Several NGOs referenced continuing to align domestic SPS measures with those applied in the EU.

Public sector bodies

Two public sector bodies prioritised SPS and 3 expressed concerns relating to food standards which included the potential consequences for the public. One respondent, with an interest in the fishing sector, highlighted that SPS requirements (regarding seafood) in the UK and Australia are already largely aligned through existing SPS arrangements between the EU and Australia. One respondent flagged their concerns for farming producers in their area that might be negatively impacted by a significant increase of Australian produce in the UK market at a time of transition for the farming sector.

Competition

Although the terms ‘competition’ and ‘competitiveness’ are sometimes used interchangeably, they have distinct technical meanings. Competition policy covers the rules and regulations concerning the way businesses operate within a market and the enforcement of such rules. Competition laws, for example, typically cover anti-competitive agreements between firms, abuse of a dominant position and merger control. Competitiveness refers to the general ability of a firm to operate in a market compared to other firms that operate in the same market, or the strength of a whole industry or economy relative to another.

Overall, most respondent groups commented on the impact of FTAs on competitiveness, not on competition policy or legal regimes. The respondents referred to high standards applicable in the UK and the related compliance costs in the context of international competitiveness. Some referred also to monopolistic practices of large firms and the need to address them.

Individuals

Fifteen individual respondents referenced competition as a priority in their comments and 15 respondents viewed it as a concern. The main issues raised were around the risk of unfair competition for UK producers, primarily in the farming and meat industry, due to better weather conditions and the potential for lower standards to give imports a comparative advantage. Comments also included the perception (by some respondents) of weaker food, drink, data, privacy and labour protections in Australia which might make UK businesses vulnerable to unfair competition. Alternatively, some respondents were positive about the opportunities arising from more market competition, lower prices for consumers and higher wages.

Businesses

Fourteen businesses prioritised competition and 11 viewed it as a concern in their comments. Many respondents recognised that the UK could be a benchmark for quality in any agreement covering services, digital trade and telecommunications and requested the removal of any trade barriers such as lack of liberalisation, which bars foreign competition. One comment from an international communications company asked for consistent, pro-competitive regulation of business grade wholesale access to communications networks to prevent discrimination by major suppliers. A media company was concerned that a trade deal with Australia might impact, some or all the PSB regime, which allows the UK to compete strongly with other countries in the AV market.

Business associations