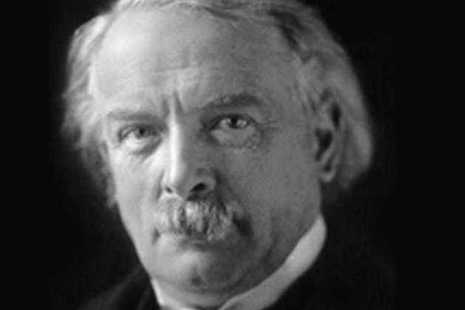

David Lloyd George

Liberal 1916 to 1922

On the House of Lords: “…a body of five hundred men chosen at random from amongst the unemployed.”

Born

17 January 1863, Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester

Died

26 March 1945, Ty Newydd, Llanystumdwy, Caernarvonshire

Dates in office

1916 to 1922

Political party

Liberal

Major acts

Education Act 1918: raised the school leaving age to 14. Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Act 1920: prohibited the employment of children below the limit of compulsory school age in railways and transport, building and engineering works, factories and mines.

Interesting facts

He is the only Prime Minister to have spoken Welsh as his first language.

Biography

David Lloyd George was one of the 20th century’s most famous radicals. He was the first and only Welshman to hold the office of Prime Minister.

Lloyd George, although born in Manchester, grew up in Caernarvonshire under the care of his uncle, who was a cobbler. Partly self-taught, he excelled in his studies at the village school, learning Latin and French in order to qualify for legal training.

He is remembered as a man of great energy and an unconventional outlook in character and politics. In 1890 he was elected Liberal MP for Caernarvon, aged 27. His scathing wit made him a dreaded - but respected - debating opponent in the House.

In 1906 he was made President of the Board of Trade, and became recognised as a very able politician. Herbert Henry Asquith later promoted him to Chancellor and he became one of the great reforming chancellors of the 20th century, introducing state pensions for the first time and declaring a war on poverty.

To pay for wide-ranging social reforms, as well as naval expansion, he intended, controversially, to tax land. He responded to the resulting outcry with passionate condemnation of landowners and aristocrats.

His reforming budget only passed after the 1911 Parliament Act greatly weakened the power of the House of Lords to block legislation from the Commons. During the war, he threw himself into the job of Minister for Munitions, organising and inspiring the war effort.

Lloyd George accepted an invitation to form a government in December 1916. His dynamism made sure he was regarded as the right man to give Britain’s war a much needed boost, yet despite his success at centralising the government machine, the army remained beyond the reach of his reforming efforts. With the end of the war in 1918 on Armistice Day he declared: “This is no time for words. Our hearts are too full of gratitude to which no tongue can give adequate expression.”

He was acclaimed as the man who had won the war, and in 1918 the coalition won a huge majority. It was the first election in which any women were allowed to vote. In 1919 he signed the Treaty of Versailles, which established the League of Nations and the war reparations settlement.

He was troubled by domestic problems, though. His agreement to the independence of the South of Ireland was reluctant, and he presided over a period of depression, unemployment and strikes. There were also concerns that he was eager for war in Turkey, and serious allegations that he had sold honours. As a result of the many scandals he had attracted his popularity faded.

When the Conservatives broke up the coalition, he handed in his resignation.

Lloyd George remained a very controversial figure; his own party could not decide whether to support him or abandon him. He largely disregarded the problems facing the party, preferring to work for himself. As a result, one of the greatest Liberal leaders was also largely responsible for the party’s downfall.

The Liberal party never ran the government again. Lloyd George later sped up the fall of Neville Chamberlain by attacking his wartime failure in Norway in 1940. In the meantime, he had spent the 1930s with journalism and travel, and the writing of his memoirs.

In 1944 he was created Earl Lloyd-George of Dwyfor, and died the following year aged 82. He is buried on the banks of the River Dwyfor.