Scientists decipher El Niño role in spread of waterborne diseases

New research shows that recent devastating outbreaks of Vibrio disease witnessed in Latin America are linked to significant El Niño events

Effects of El Nino

Scientists from the Centre for the Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas) and co-authors, including scientists from US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, the US Food and Drug Administration and University of Bath have published today in Nature Microbiology.

Dr Craig Baker-Austin a Cefas author on the paper said:

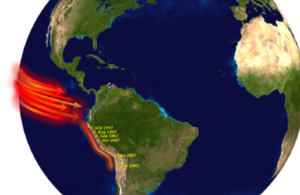

El Niño is a climate pattern that describes the unusual warming of surface waters along the tropical west coast of South America. These events tend to occur every 3-7 years, and are not strictly predictable. The major manifestation of El Niño is the displacement of warm water from the Western to Eastern side of the Pacific Ocean. The impact of El Niño is immense - this natural oceanographic phenomenon plays a significant role in local weather patterns, the health of fisheries, extreme meteorological events as well as global climate.

Strikingly, during the last 3 decades and coinciding with the last 3 significant El Niño events (1990-91, 1997-98 and 2010), new variants of waterborne pathogens have emerged into Latin America. These have included a devastating cholera outbreak in Peru in 1990 (caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae), and two instances in 1997 and 2010 where new variants of Vibrio parahaemolyticus – a bacterium that can cause human illness from the consumption of shellfish.

A particularly interesting observation is that reported illnesses have appeared to move in tandem with when and where these warm waters make contact with land. But are these instances a pure coincidence, or is El Niño responsible for transporting these pathogens into Latin America?

New data, including information gleaned from whole genome sequencing of strains causing illness in Latin America suggest that there may indeed be a linkage between organisms that cause illness in Asia, and those that emerge in Latin America - in particular Peru and Chile. In addition, these strains have been identified in environmental sources – providing further evidence that El Niño waters may be responsible for the transportation of these emergent pathogens thousands of miles. But how can this happen?

Dr Craig Baker-Austin continued:

Microscopic bacteria found commonly in seawater can attach to larger organisms, such as zooplankton. Vibrios have been shown to bind to and use these larger organisms as an energy source in numerous studies. Hence, they may be able to essentially ‘piggyback’ enormous distances, driven by tidal patterns. An El Niño event could therefore represent an efficient long-distance ‘biological corridor’ allowing the displacement of marine organisms from distant areas. This process could provide both a periodic and unique source of new pathogens into America with serious implications for the spread and control of disease.

Notes

-

For more information also read Craig Baker-Austin’s blog

-

For more information contact helen.egar@cefas.co.uk