Surviving Sandy

The Defence Attache in Washington, Major General Buster Howes, recalls his role in helping to manage the crisis that was Hurricane Sandy.

US Marines arrive in Staten Island, New York, with shovels, axes and other tools to assist local residents with clean-up efforts in the wake of Hurricane Sandy [Picture: Elaina Marie]

As the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy continues to affect the US East Coast, Major General Howes, the British Defence Attache in the USA and one of the Embassy’s designated crisis managers, described his role as the situation unfolded.

Hurricane Sandy didn’t exactly take the US by surprise as for several days the US media were warning of a storm of biblical proportions shunting its way in from the south.

This provoked a practical response from many - boarding up windows and evacuating homes along the coastal regions, but in places like Washington DC it generated a subdued sense of apprehension and expectation. The streets were empty and people braced themselves for ‘The Storm of a Lifetime’.

General Howes explained that the Embassy prepares for a range of civil emergencies, including natural disasters, with the specific aim of being able to assist British nationals who may be affected by such events.

The assistance focuses on passing information between the US and the UK and particularly helping to locate people in difficulties; assisting with travel arrangements when they have been disrupted as well as accommodation problems.

There are about eight million British visitors to the US each year, so there is a high probability that British nationals will be caught up in such events, much as they were when the World Trade Centre was attacked on 9/11.

On the day of the hurricane, the Embassy was due to run a crisis exercise, involving teams in London, DC and New York, to further develop procedures and staff competence.

Major General Buster Howes [Picture: Leading Airman (Photographer) Dean Nixon, Crown Copyright/MOD 2012]

General Howes said:

We chose New York for a whole raft of technical reasons. We were due to do the final planning conference on the Monday, to test all the systems on Tuesday, and run it on the Wednesday - just at the time when Sandy struck.

As Sandy approached, the British Embassy in Washington and the consulates in New York and Boston began contingency planning for a hurricane and prepared for a possible crisis. A strong storm hit DC, but minimal damage actually resulted.

In comparison, the coastal areas around New York were devastated, inundated by a powerful, storm-driven tidal surge which was compounded by the full moon state and spring tides. Federal buildings were shut down for two days in DC as a precautionary measure, which also affected the Embassy.

Driving in metropolitan DC is pretty ‘wild’ at the best of times so this measure was designed to relieve traffic congestion in potentially bad conditions which would have compounded the risk of accidents.

As a consequence of the dramatic media reporting, there was a general run on supermarkets for food and batteries and lanterns, since electrical supplies are often compromised by storm damage, as well as petrol.

Describing the mood, Major General Howes said:

Clearly the vast majority of people aren’t British but within the Embassy there was a sense of calm expectation. We have a good system for passing information amongst Embassy staff which we obviously utilised, so between that and the television our people remained well informed throughout.

A log jam on the Potomac River next to the Tidal Basin [Picture: Glyn Lowe Photoworks]

He dismissed any notion of hysteria saying:

It was pretty understated with considerable humour. We were all stuck at home so, as the responsibility to help manage some of the consequences of the hurricane developed, people were networked at home.

Instead of being holed up in a crisis centre, General Howes worked from home.

One consequence was that his personal hotmail account crashed at one stage under the weight of e-mails. Asked if he worked closely with the consular office, General Howes described a ‘battle rhythm’ punctuated with daily early morning and late night calls to London, regular sit-reps and daily telephone conferences.

Early on, the media focus switched to New York as it became clear that the worst devastation had affected Maryland, New Jersey, Delaware and the whole eastern seaboard of the US leaving 2.5 million homes and businesses crippled by surging seawater and loss of power.

Around 140 Defence Staff work in the British Embassy, underpinned by a team of support staff stretching across 34 of the 50 states. General Howes is based in the British Embassy, although he travels widely.

He praised the way that military and civilians pulled together, saying:

We weren’t acting in a military way, though the expertise, experience and brain power involved military people. That said, the ‘crisis’ meant that people were isolated so the whole Embassy didn’t spin into action the way it would for a more extensive crisis affecting British nationals.

Flood barriers up at Washington Harbour [Picture: Glyn Lowe Photoworks]

Hypothetically, if there was a terrorist attack in Massachussetts, the Embassy would swing into crisis mode, everyone would coalesce, and more people would get swept into the operation. However, because we were all at home until Wednesday morning, fewer people were engaged but there were still military people involved.

Asked if there was a sense of detachment given that the focus was in New York, General Howes said:

Well, we just happen to be in DC because it’s the capital but if there’s a problem in America, the Embassy has a lead in helping to resolve it.

The fact that the storm impact was on and around New York made gaining situational awareness in DC a bit harder and our job was to support people struggling with the impact there.

With an estimated 50,000 Brits thought to be staying in New York, General Howes explained that the crisis team provided consular care to British nationals as necessary and kept London informed of developments, issuing emergency travel papers and providing assistance to 57 British nationals who contacted the New York Consulate looking for help.

This included supporting 25 schoolchildren whose flight was cancelled and helping 20 British nationals who fled without their luggage following their evacuation from the Salisbury Hotel adjacent to a dangling crane on West 57th Street:

We didn’t send people into the field in such uncertain and potentially hazardous circumstances. They anyway would have struggled to get where they wanted to go, but if people called in to say ‘hey, I need help, I’m British’, we were in a position to advise, direct and assist where we could.

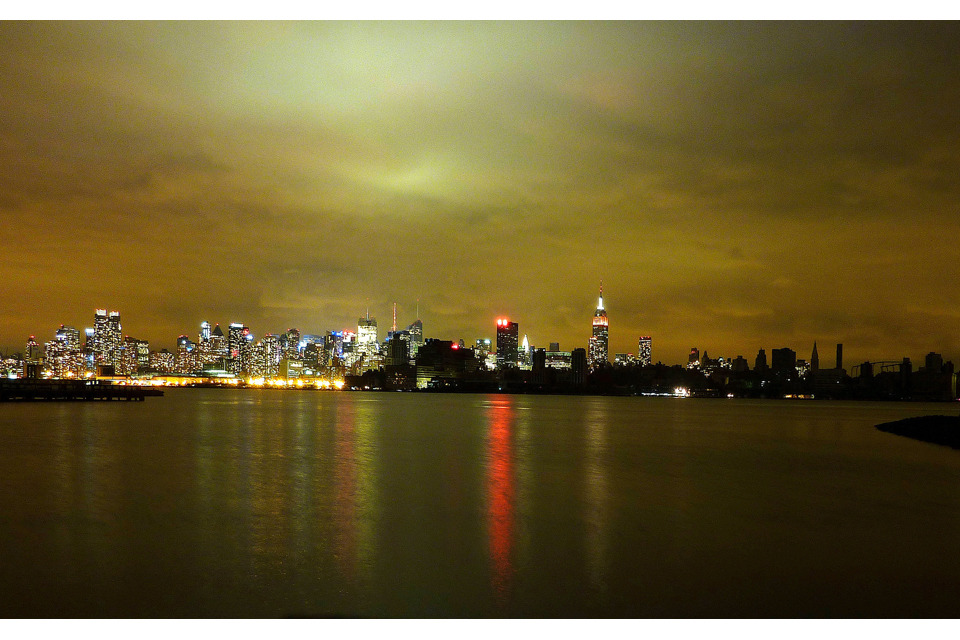

Hurricane Sandy rages over Manhattan [Picture: Michael Cairns]

Asked for his abiding memory of Sandy, General Howes explained:

Well - from DC’s perspective - if you imagine a very powerful storm with 60mph [97km/h] winds and torrential rain for two days, that’s what it felt like.

General Howes added:

I think the abiding memory is thinking how fortunate we were here and how powerful nature is when it gets angry. It was also slightly surreal watching the drama playing out around New York on TV at home.

This is absolutely not a story of personal drama. It’s important to reinforce the fact that the story wasn’t in DC. In a modest way, we helped manage the unfolding mayhem as it affected UK nationals in the area.

Our ability to influence what was happening in Delaware, New Jersey and Ocean City was non-existent, but through the TV images we had a profound sense of ‘There but for the grace of God go we’.