The Great Escape 70 years on

The 'Great Escape' from Second World War prisoner-of-war camp Stalag Luft III took place on this night 70 years ago.

![A replica of one of the escape tunnels (library image) [Picture: Senior Aircraftman Neil Chapman, Crown copyright]](https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a619ecded915d0afc463f15/s300_MNT-10-011-OUT-UNC-0087.jpg)

A replica of one of the escape tunnels at Stalag Luft III (library image)

Although 200 airmen had planned to escape through man-made tunnels, only 76 managed to taste freedom and 73 were later captured. Of those who broke out, only 3 reached safety, and, of the 73 recaptured, 50 were shot dead by Nazi Germany’s feared secret police force, the Gestapo.

Today, a ceremony to commemorate the Great Escape took place in Zagan, Poland; a town near to the site of the Luftwaffe-run prisoner-of-war camp. Attending the ceremony were survivors of the Stalag Luft, which means ‘camp for aircrew’, families of those held there and UK and Polish officials.

The ceremony in Poland was the first formal act of remembrance held in their honour. Between 5 and 10 survivors of the prisoner-of-war camp were expected to attend.

Poznan Old Garrison Cemetery, Poland [Picture: Commonwealth War Graves Commission]

Fifty RAF personnel will now march for 4 days to the cemetery at Poznan, where many of the 50 murdered prisoners of war are buried, and lay wreaths in their memory.

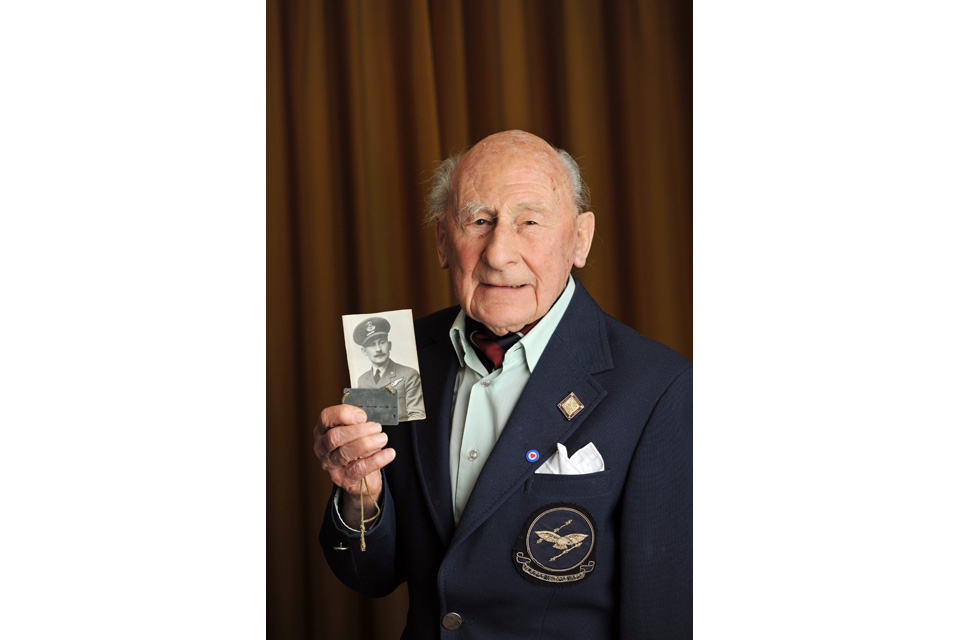

Former Flight Lieutenant Jack Lyon, now 96, was one of those who didn’t manage to escape that night. He was discovered in Hut 104, waiting to go down the tunnel. Despite the high price paid by many, he still thinks it was all worth it:

It was a costly operation but not necessarily unsuccessful. It did do a lot for morale, particularly for those prisoners who’d been there for a long time. They felt they were able to contribute something, even if they weren’t able to get out. They felt they could help in some way and, trust me, in prison camps, morale is very important.

Former Flight Lieutenant Jack Lyon [Picture: Adrian Brooks/Imagewise]

You can read more survivors’ stories on a blog on the Royal Air Force Benevolent Fund website , set up to commemorate the amazing story 70 years on.

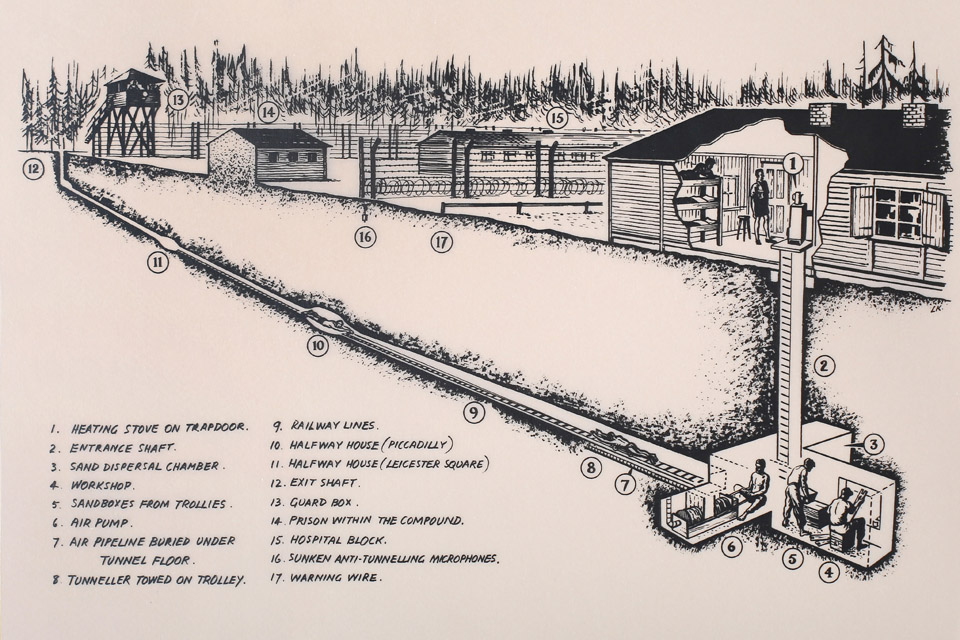

The tunnels

In 1943, under the leadership of Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, RAF prisoners at Stalag Luft III started the mammoth task of digging 3 tunnels, known as ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’. The tunnels were 30 feet deep and were meant to run more than 300 feet into woods outside the camp.

A drawing showing the proposed route of one of the escape tunnels, by wartime artist Ley Kenyon, a prisoner-of-war in Stalag Luft III at the time of the Great Escape in March 1944 [Picture: from the original drawings of Ley Kenyon 1943]

The prisoners used anything they could find, or steal, in the camp to line the tunnels with wood, run a railway and electric lighting, and create primitive ventilation. They also made civilian clothes, maps, compasses and German passes to help them escape.

Tunnel Tom was discovered in September 1943 just as it reached the woods and ‘Dick’ was abandoned for storage. All hopes were pinned on ‘Harry’, which was ready in early 1944.

In the aftermath of the escape, when news of the 50 officers murdered reached Britain, there was outrage over the killings.

The British demanded that the killers be brought to justice. After the war, they kept their word, and many of the killers were punished by Allied courts.