Treating PTSD in the Armed Forces

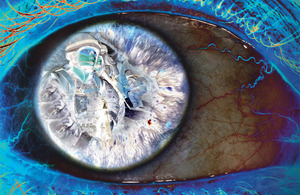

How eye pupil movement is helping Service personnel fight the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing is a cutting-edge therapy helping PTSD sufferers

When Sergeant Steve Johnson was asked if he would like to trial a mindboggling new treatment for post-traumatic stress he had nothing to lose:

I’d already rehearsed how I would kill myself, what would be the cleanest way, and how it would affect others.

Lost in mental illness, he became one of the first troops to try out the intriguing and cutting-edge therapy called eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) - a practice which would force him to relive suicidal thoughts but ultimately go on to help save his life.

The psychotherapy technique is based on the idea that if people think about a traumatic image while watching an object move back and forth, distressing feelings will reduce in intensity. Basic eye movement, sounds or taps to the skin all help to activate networks in the brain which can become blocked following disturbing experiences.

By clearing these pathways, the mind is allowed to properly process thoughts and anxieties that have been previously locked out by individuals. And sci-fi connotations aside, the results of the method appear hard to deny.

Royal Marines brace themselves against the downdraft from an incoming RAF Chinook helicopter in Afghanistan [Picture: Leading Airman (Photographer) Rhys O'Leary, Crown Copyright/MOD 2012]

On his return from Afghanistan with the Royal Military Police in 2007, Sergeant Johnson, also a veteran of Bosnia, Rwanda, Kosovo and Iraq, began suffering recurring nightmares and flashbacks for the first time in 15 years of operational service. The mental state of the soldier deteriorated fast so his doctor sent him to be assessed:

I was waking up screaming and smelling burning flesh. I could taste things from all my tours. Everything I had seen had come back; the sensations running through my body.

Africa was horrific, I saw lots of bodies in the road as a result of genocide; people lying dead in the street.

On Operation Telic 1 (Iraq) I was part of the mop-up team, clearing trenches. I saw burnt, charred bodies. Teeth don’t burn - that was one of the many visions that haunted me during my career.

Watching the TV afterwards I would sometimes zone out. I wouldn’t be there; my mind would be somewhere else and I’d have constant flashbacks.

Diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, Sergeant Johnson was sent to Woking’s Priory Hospital where he was the only serviceman. After trying cognitive behavioural therapy and an endless list of medications, the centre recommended EMDR but warned that it would be physically draining:

The therapist said I would relive all the feelings and sensations I had during the events I was thinking about. My reaction was to ask myself ‘do I want to go back?’

But, willing to try anything, he agreed:

I knew I needed to do something; I made the decision to undergo the first session because you can only really be scared of something you’ve experienced.

British soldiers from the Brigade Reconnaissance Force conducting a search of compounds in Afghanistan [Picture: Sergeant Wes Calder RLC, Crown Copyright/MOD 2011]

The serviceman sat down opposite a therapist while she tapped each hand 12 times to sensitise the nerve endings. During the 30-minute appointment in a quiet room, he was then asked to relay encounters from his past:

I suppose it was like being hypnotised, then coming back to reality and talking through the things I had described. As soon as she started talking to me it felt like I was out in theatre.

I was back in a seven-hour contact in Afghanistan - something I thought I had dealt with. When I was brought back round I was so tired I couldn’t walk, just like when I had actually been there.

After that first consultation the traumatised soldier maintained that he could not go through it again but was encouraged to do so in a bid to try and move on:

I wasn’t really happy about it but the sessions ended up processing what had happened in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere - all things I thought I had dealt with.

Undertaking weekly meetings over 3 months while staying in the Surrey clinic, Sergeant Johnson was then released and put on sick leave, during which time he underwent more of the psychotherapy as a day-patient.

Eager to get back in uniform, in December 2007 he started a gradual return to work programme and was posted to Northern Ireland the following year. Despite military missions clearly having triggered his mental health issues, Sergeant Johnson had no doubts whatsoever that his future remained in the Service:

I just wanted to get back to work because I love it. Without the Army I wouldn’t have been able to help the people I have or do the good things I’ve done.

In what is a quite remarkable transformation, Sergeant Johnson is now preparing to deploy on Operation Herrick 18 as a police advisor:

I am really looking forward to it as it’s been my end goal to return to active service where it all started.

Royal Marines conducting a deliberate action against Taliban insurgents in Afghanistan [Picture: Petty Officer Airman (Photographer) Sean Clee, Crown Copyright/MOD 2007]

As one of the first members of the Armed Forces to receive the powerful treatment, the soldier has welcomed the emergence of trained EMDR therapists in every defence community mental health centre. And although some sceptics refuse to believe the science behind the process, excitement about its results is palpable across the military.

Explaining the simple technique, which was approved by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in 2005, MOD consultant clinical psychologist Susanne McGowan said:

The theory is that our minds have a system where difficult things are processed, sorted and filed away.

With traumatic experiences it seems this does not happen - the image gets shut in a different part of the brain. EMDR is an unlocking process.

With some clinicians suggesting that the impact of the treatment is nothing more than a placebo, debate over its results is set to continue. But whatever the future for the strange therapy, Sergeant Johnson is clear that its use has finally helped him to put severe anxiety to one side:

I thought I had dealt with everything I saw but the sessions brought it out and put it back in order. Different things help people in different ways but for me EMDR is the only reason I am here today. I can’t explain the science behind it, but it worked.

This article by Joe Clapson first appeared in the January 2013 edition of Soldier magazine.

You can also listen to a report by Caroline Wyatt on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme (35 minutes into the programme) or read her online article on the BBC News website.