UK-built Solar Orbiter catches a second comet by the tail

The UK-built Solar Orbiter spacecraft has flown through the tail of a comet for the second time in its mission so far

Composite of images of Comet Leonard captured 15-16 December 2021 in ultraviolet light from the Metis instrument on Solar Orbiter. Credit: ESA/Solar Orbiter/Metis Team.

The event was predicted in advance by astronomers at University College London, and the spacecraft has been able to collect a wealth of science data for analysis.

Built by Airbus in Stevenage, Solar Orbiter is designed to conduct unique studies of the Sun but is also making a name for itself exploring comets. For several days in December 2021, the spacecraft found itself flying through the tail of Comet C/2021 A1 Leonard.

The ESA/NASA mission, which launched in February 2020 and has already taken the closest images ever of the Sun, captured information about the particles and magnetic field present in the tail of the comet. This will allow astronomers to study the way the comet interacts with the solar wind, the stream of energetic particles that emanate from the Sun and sweeps through the solar system.

Comet tail crossings are relatively rare events. Both of Solar Orbiter’s encounters were predicted in advance thanks to the computer code developed by Geraint Jones from the University College London Mullard Space Science Laboratory.

The work also helps build experience for ESA’s Comet Interceptor mission, for which Geraint is the Science Team Lead. The mission will visit an as-yet undiscovered comet, making a flyby of the target with three spacecraft to create a 3D profile of a ‘dynamically new’ object that contains unprocessed material surviving from the dawn of the Solar System.

In the meantime, the instrument teams on Solar Orbiter are busy analysing the Comet Leonard data not only for what it can tell them about the comet but about the solar wind as well.

Caroline Harper, Head of Space Science at the UK Space Agency, said:

This is a brilliant example of scientists working together and pooling expertise across different missions, to get the most from them by seizing opportunities of this kind.

Now we can look forward to many more fascinating insights from Solar Orbiter’s main mission - to study the Sun and how it affects space weather. And we can expect great things from Comet Interceptor when it launches in 2029.

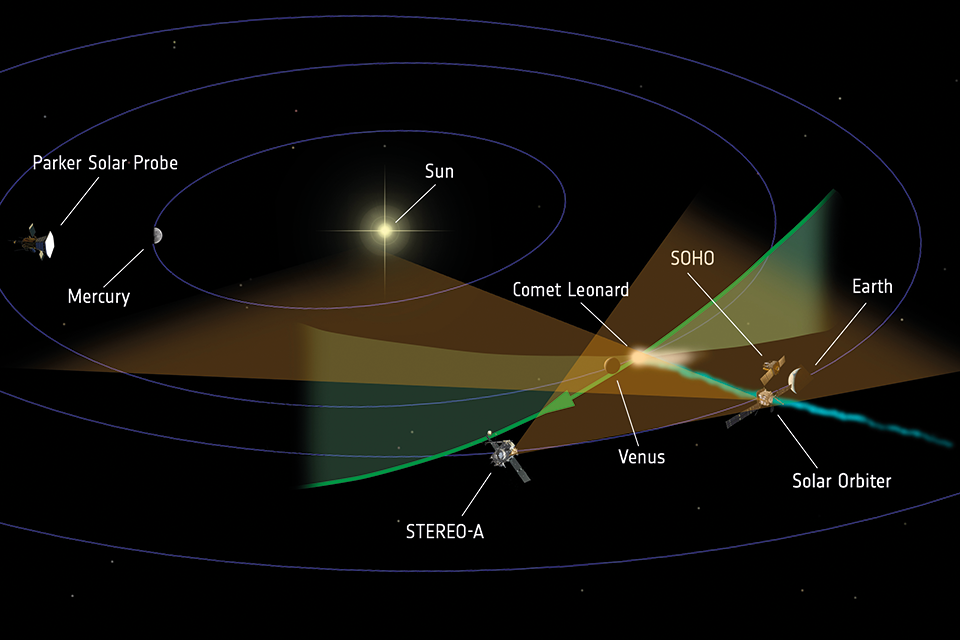

Solar Orbiter flew through the tail of Comet Leonard in December 2021. Credit: G Jones and S. Grant (UCL).

The crossing had been predicted by Samuel Grant, a post graduate student at University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory. He adapted an existing computer program that compared spacecraft orbits with comet orbits to include the effects of the solar wind and its ability to shape a comet’s tail.

Samuel Grant, from University College London’s Mullard Space Science Laboratory, said:

I ran it with Comet Leonard and Solar Orbiter with a few guesses for the speed of the solar wind. And that’s when I saw that even for quite a wide range of solar wind speeds it seemed like there would be a crossing.

At the time of the crossing, Solar Orbiter was relatively close to the Earth having passed by on 27 November 2021 for a gravity assist manoeuvre that marked the beginning of the mission’s science phase, and placed the spacecraft on course for its March 2022 close approach to the Sun. The comet’s nucleus was 44.5 million kilometres away, near to the planet Venus, but its giant tail stretched across space to Earth’s orbit and beyond.

So far, the best detection of the comet’s tail from Solar Orbiter has come from the UK-led Solar Wind Analyser (SWA) instrument suite. Its Heavy Ion Sensor (HIS) clearly measured atoms, ions and even molecules that are attributable to the comet rather than the solar wind.

Ions are atoms or molecules that have been stripped of one or more electron and now carry a net positive electrical charge. SWA-HIS detected ions of oxygen, carbon and nitrogen, as well as molecules of carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide and possibly water.

As a comet moves through space, it tends to drape the Sun’s magnetic field around it. This magnetic field is being carried by the solar wind, and the draping creates discontinuities where the polarity of the magnetic field changes sharply from north to south and vice versa.

Data from the magnetometer instrument (MAG), also led by the UK, suggests the presence of such draped magnetic field structures but there is more analysis to be done to be sure.

Lorenzo Matteini, a co-investigator on MAG from Imperial College, London, said:

We are in the process of investigating some smaller scale magnetic perturbations seen in our data and combining them with measurements from Solar Orbiter’s particle sensors to understand their possible cometary origin.

In March, Solar Orbiter makes its closest pass to the Sun yet at a distance of 0.32 au (approximately one-third of the Earth-Sun distance, or about 50 million kilometres). It is one of almost 20 close passes to the Sun that will occur during the next decade. These will result in unprecedented images and data, not only from close up, but also from the Sun’s never-before seen polar regions.

The UK is at the heart of the Solar Orbiter mission with UK industry winning £200 million worth of contracts and the UK Space Agency investing £20 million in the development and build of the instruments.