What can we learn from the Seadogz accident?

In this article we consider best practice in RIB operations and how risks can be controlled.

When you are trying to promote the fun element of an activity, also telling your customers that it can be hazardous might appear counterproductive. This could explain the reluctance of the ‘small-craft passenger/experience ride’ industry to acknowledge and take action on the findings from recent accident investigations. However, until the lessons are acknowledged and appropriate actions taken, passengers will continue to suffer life-changing injuries and possibly death as the (MAIB’s) investigation report into the Seadogz accident illustrates. If this sounds like a hard-hitting message, it is meant to be.

Early warnings – “Houston, we have a problem”

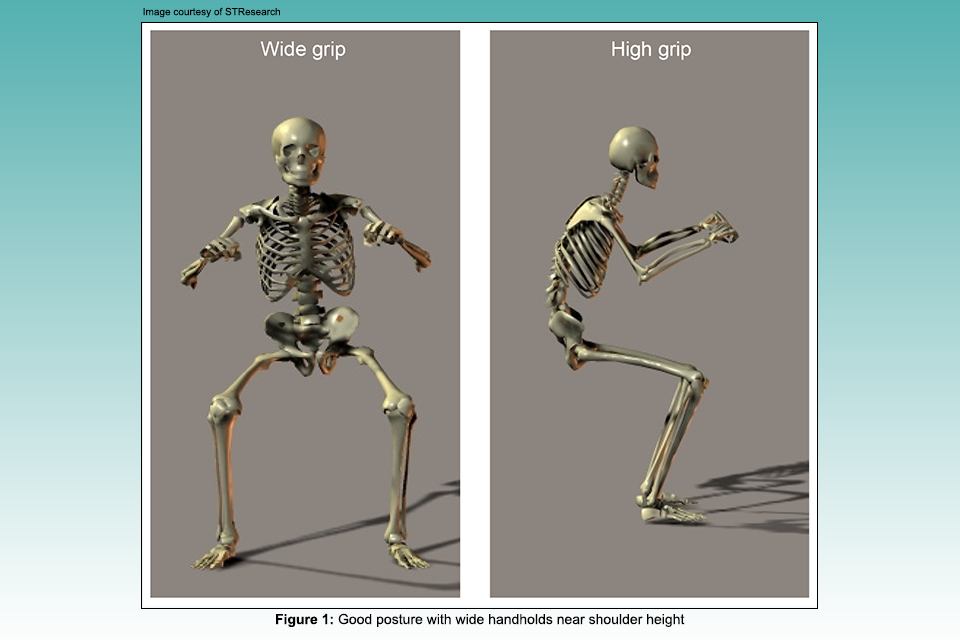

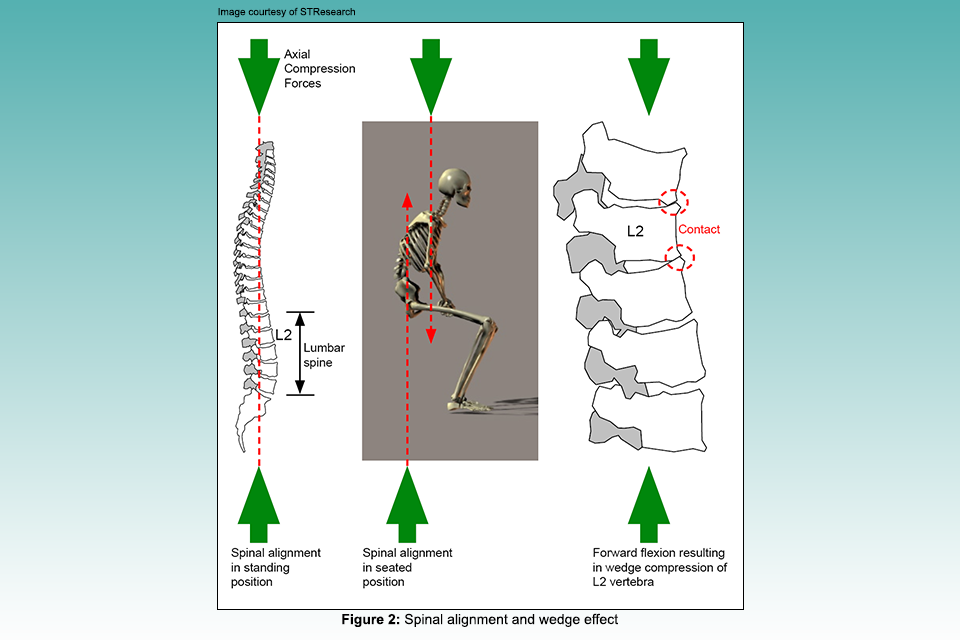

The MAIB has investigated numerous rigid inflatable boat (RIB) accidents, many of which are referred to in this article. While the early investigations focused on the usual crop of collisions and groundings, it was not until the investigation into the heavy landing of the RIB Celtic Pioneer (MAIB report 11/2009) in 2008 that passenger vulnerability to injury came into focus. That investigation report drew on recent academic and practical research to highlight the importance of good seating, posture and handholds to help mitigate against spinal injuries (Figure 1). The particularly vulnerable part of the spine was found to be the lower lumbar region (L1 to L3) (Figure 2), which could suffer wedge compression fractures, but other spinal injuries were not uncommon.

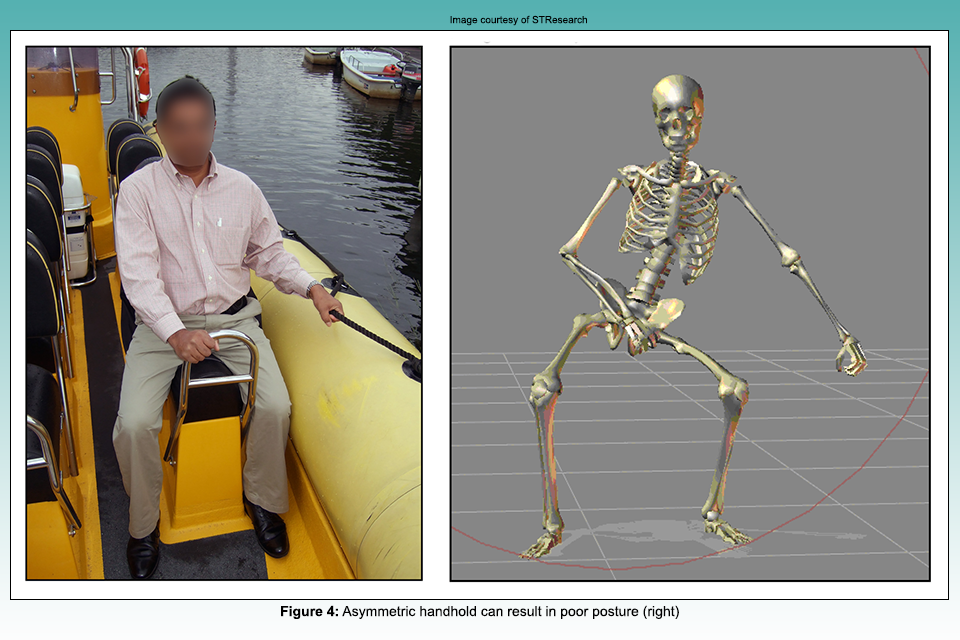

Fortunately, passengers suffering less damaging injuries often walked off the RIB with a sore back but, if the pain persisted, they would see their doctor a few days later, by when the link between the injury mechanism (the RIB ride) and the injury had been lost. Consequently, the MAIB was only aware of those accidents where the emergency services were called to extract the injured party. This resulted in a skewed picture of the actual injury rate. Nonetheless, there were still sufficient accidents being reported for the branch to heavily warn against the consequences of poor posture and inadequate seating (Figures 3 and 4).

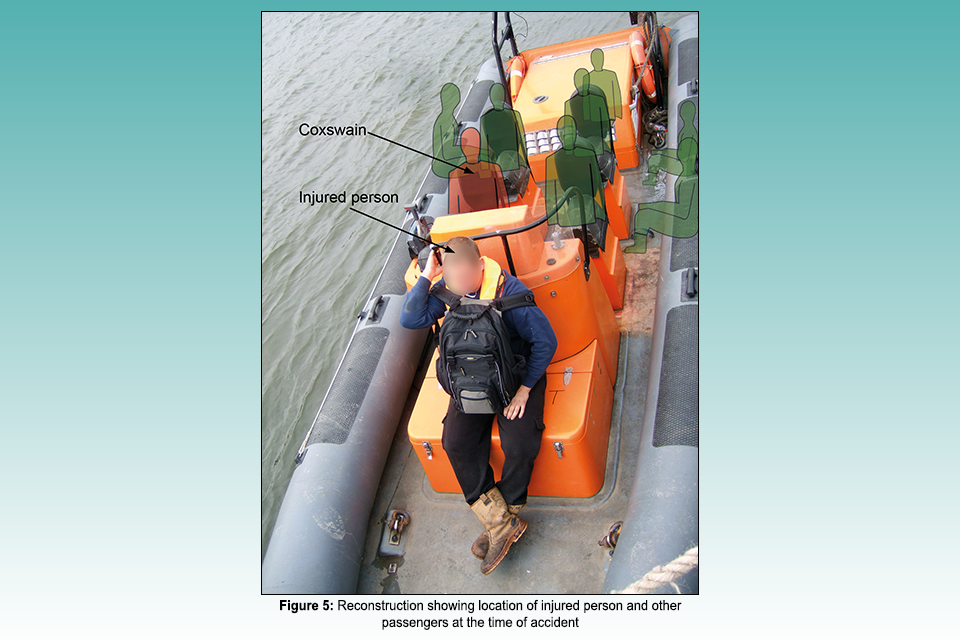

Unfortunately, the messages were not getting through and a short while later a person travelling to work on the River Thames suffered a very serious back injury when the Delta RIB (MAIB report 1/2011) they were travelling on crossed the wake of another vessel at about 30 knots. The worker was sitting on top of a locker with no padding or handholds and had their rucksack across their chest (Figure 5).

The combination of the hard seat and poor posture resulted in the victim suffering anterior wedge fractures of the first and third lumbar vertebrae (L1 and L3). The victim was fitted with an external body brace in hospital and remained off work for more than 4 months while recovering, though was still receiving physiotherapy treatment 8 months after the accident.

In response to the MAIB’s recommendations the industry produced two voluntary codes of practice for RIB operators, but initial take-up was patchy.

The hazard of side impact

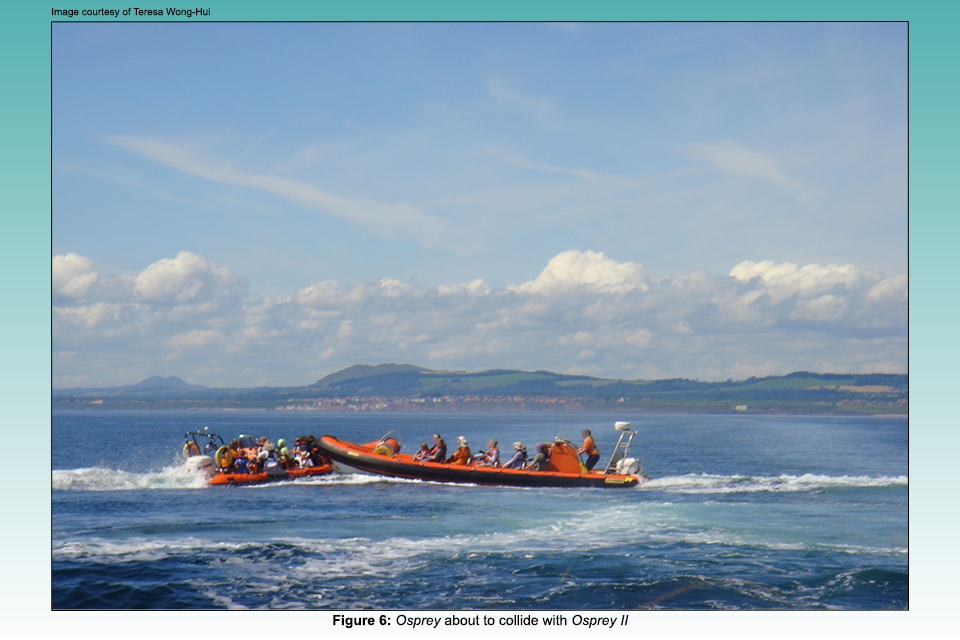

The collision between Osprey and Osprey II (MAIB report 10/2017) that left a passenger with life-changing injuries highlighted how vulnerable passengers in small boats were to side impact injuries.

Accidents involving small race boats had shown how easily one boat hitting the other side-on could ride up and over it, and that the passengers in the receiving boat had little or no protection. RIBs were particularly vulnerable as the shape of the tubes helped lift the bow of the colliding boat so it crossed the seating area, and any passengers seated on the tubes could take the full force of the impact. Not only was it impossible to maintain a good posture when seated on a tube, but the added risks from side impact were considered too high and the MAIB recommended that when the Maritime and Coastguard Agency (MCA) updated the small commercial craft codes it included a requirement that every passenger in a commercially operated passenger-carrying RIB had a suitable seat.

The Osprey RIBs accident also highlighted the hazards of fast/high-speed craft operating close to each other where, unless their manoeuvres were well coordinated, the risk of collision could be high. Although the two RIBs usually passed each other during a scheduled high-speed turn, on the day of the accident their start positions were reversed. As the RIBs approached each other head-on (Figure 6), the skippers were confused as to whether they should pass ‘as normal’ or follow the COLREGs and each alter to starboard. Although both skippers reduced speed the RIBs collided, crushing a passenger against the console. Had the risk of collision during the turn been considered before the trip, risk mitigation measures could have been planned.

Head-on impact – Seadogz

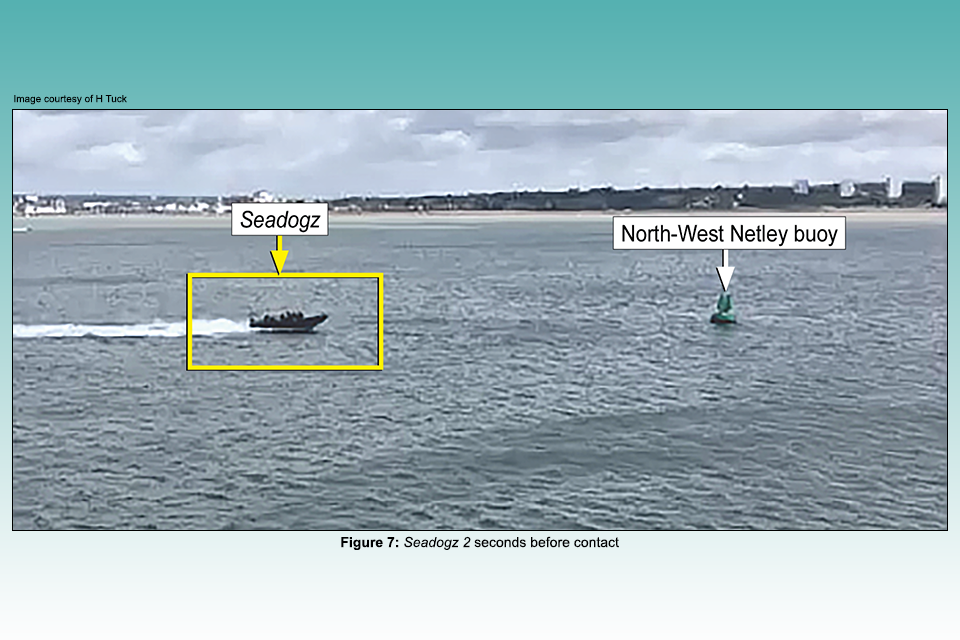

On 22 August 2020, the commercially operated RIB Seadogz (MAIB report 10/2023) hit a navigation buoy at high speed in Southampton Water (Figure 7).

The skipper and the 11 passengers suffered impact injuries; two passengers were thrown into the water and 15-year-old Emily Lewis, who was sitting in the middle of the bench seat, sustained fatal injuries. The MAIB’s investigation concluded that the skipper did not see the buoy in sufficient time to avoid it as he had lost positional awareness, most likely due to the high mental workload of operating the RIB alone and at high speed. Further: the seating and handholds on the RIB afforded little protection to the passengers during rapid deceleration; the operator’s safety management procedures were cursory and generic; and the current regulations for such operations needed updating.

Other safety issues were also identified. Two of the passengers were ejected into the water, one of whom started to panic as their lifejacket rode up on inflation as it had not been fitted properly. From the helm position, the bow-up trim of the RIB and the passengers’ heads combined to limit the skipper’s forward visibility. Most worrying, the conduct of the trip fell short of ‘good practice’ in many ways. The tight figure-of-eight turns carried out at speed introduced the risk of a ‘hook’; the RIB was being jumped over wakes, and the frequent close passes to the large navigation buoys desensitised the passengers to the risk of collision. When Seadogz was heading directly towards North-West Netley lateral buoy it is likely that most of the passengers expected the RIB to turn away at the last minute. When that did not happen, it was too late to warn the skipper of the impending collision.

In response to the accident, the Royal Yachting Association (RYA) has started to update the Passenger Safety on Commercial High Speed Craft and Experience Rides – a Voluntary Code of Practice, and the MAIB has, again, made a number of recommendations. The investigation report recommended that the MCA introduce updated guidance (the Sport and Pleasure Vessel Code) as soon as possible. However, noting the risks to passengers from vertical impacts and side impacts already identified in previous investigations, the MAIB also recommended that the MCA carry out a full anthropometric assessment of the risks to passengers travelling in small high-speed craft, the results from which should be reflected in the new Code as soon as possible. The port and harbour associations were also recommended to provide guidance to harbour authorities on how they should oversee the activities of small commercial craft operating in harbour areas.

So what now?

Initial feedback is that many operators seem to be distancing themselves from the Seadogz accident by stating that the lessons do not apply to their operation: Sea safaris and wildlife sightseeing trips are not high-speed/thrill rides, so we can carry on as normal. Perhaps too much focus has been put on ‘high speed’, but the reality is that passengers in RIBs can suffer horrific injuries at even slow speeds. The collision between Osprey and Osprey II occurred at relatively slow speed, but these large RIBs each weighed several tonnes so the crushing force was significant. And, last year, a passenger on a sea safari RIB suffered life-changing spinal injuries when the RIB, travelling at quite slow speed, fell off a wave into a deep trough.

Time will tell whether the public shunned RIB rides in 2024 as a result of the Seadogz accident, but we can be certain that those taking trips do not expect to spend the rest of their life in a wheelchair because of an injury sustained during the trip. Good practice is being taught during RYA training, and there is plenty of guidance available in the Commercial High Speed Craft and Experience Rides Code and on the RYA’s website. However, it is worth reiterating a few key points.

Operating procedures

Operators should be clear about the sort of trips they are offering, assess the hazards, and ensure that suitable mitigating measures are in place. If the mitigations cannot be delivered, then do not offer the trip. Pay particular attention to feedback; if someone has been injured in the past, adjust the trip/route to prevent it happening again. Further, all helms should be briefed on what they should be doing and what is off limits. If, for example, the RIB’s seating does not provide shock mitigation, then strict speed and sea state limits need to be set and adhered to. If the trip involves high-speed manoeuvres, is a second crew required to help keep a lookout and an eye on passenger safety while the skipper is concentrating on helming?

Pre-departure briefing

There is a lot to fit in to a good pre-departure brief besides telling the passengers what they are about to experience. Lifejacket operation must be explained and their fit checked; passengers need to know how to sit correctly, brace themselves and hold on; each passenger must be allocated to a seat suitable for them and checks made to ensure their feet can gain firm purchase on the floor, their backs can rest on the back support, and they can grip the handholds correctly. Finally, the means of signalling concern or a problem needs to be both understood and achievable. Passengers are unlikely to raise their hands if they are clinging on for dear life. All this takes time, so scheduling must allow for it, or other staff be used. Carrying out the brief while walking to the boat or donning lifejackets while underway might save time, but it will not save lives.

Conduct of the trip itself

The trip should always be operated in line with the offering made. If passengers have booked on a wildlife sea safari ride, they might not expect to be subjected to a thrill ride involving tightly banked turns at speed or wave and wake jumping. Even thrill-seeking passengers might find manoeuvring at 25 to 30 knots exciting so operating at 40 to 50 knots could stray into a terrifying experience. It is worth remembering that skippers can easily become insulated from the experience on offer. If the RIB has an aft helm position, then the motion experienced by the crew will be much softer than that affecting passengers near the bow; the skipper is looking ahead and helming so they can anticipate the boat’s motion; they are experienced at bracing themselves; and, of course, they have done the trip multiple times before. A passenger RIB ride is not the time to start exploring the operating limits of their boat; whatever the experience on offer, the skipper’s prime concern must be to return their passengers safely ashore uninjured.

So is that it? Should we shut up shop?

Absolutely not. RIB rides are accessible and fun when conducted well and there is a strong market for them. However, while the Sport and Pleasure Vessel Code is coming and the Passenger Safety on Commercial High Speed Craft and Experience Rides – a Voluntary Code of Practice is being updated, there is no need to wait for these before improvements are made. If the sector’s reputation is to survive accidents like Seadogz, owners and operators need to start owning best practice, controlling the risks and demonstrating that their trips are safe.

This article by the MAIB first appeared in https://powerboatandrib.com/

Media enquiries (telephone only)

Media enquiries during office hours 01932 440015

Media enquiries out of hours 0300 7777878