A fairer private rented sector

Updated 2 August 2022

Applies to England

Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities and Minister for Intergovernmental Relations

June 2022

CP 693

ISBN 978-1-5286-3348-2

Foreword from the Secretary of State

Everyone has a right to a decent home. No one should be condemned to live in properties that are inadequately heated, unsafe, or unhealthy. Yet more than 2.8 million of our fellow citizens are paying to live in homes that are not fit for the 21st century. Tackling this is critical to our mission to level up the country.

The reality today is that far too many renters are living in damp, dangerous, cold homes, powerless to put things right, and with the threat of sudden eviction hanging over them.

They’re often frightened to raise a complaint. If they do, there is no guarantee that they won’t be penalised for it, that their rent won’t shoot up as a result, or that they won’t be hit with a Section 21 notice asking them to leave.

This government is determined to tackle these injustices by offering a New Deal to those living in the Private Rented Sector; one with quality, affordability, and fairness at its heart.

In our Levelling Up White Paper - published earlier this year - we set out a clear mission to halve the number of poor-quality homes by 2030.

We committed to levelling up quality across the board in the Private Rented Sector and especially in those parts of the country with the highest proportion of poor, sub-standard housing - Yorkshire and the Humber, the West Midlands, and the North West.

This White Paper – A Fairer Private Rented Sector – sets out how we intend to deliver on this mission, raising the bar on quality and making this New Deal a reality for renters everywhere.

It underlines our commitment, through the Renters Reform Bill, to ensure all private landlords adhere to a legally binding standard on decency.

The Bill also fulfils our manifesto commitment to replace Section 21 ‘no fault’ eviction notices with a modern tenancy system that gives renters peace of mind so they can confidently settle down and make their house a home.

These changes will be backed by a powerful new Ombudsman so that disputes between tenants and landlords can be settled quickly and cheaply, without going to court.

This white paper also outlines a host of additional reforms to empower tenants so they can make informed choices, raise concerns and challenge unfair rent hikes without fear of repercussion.

Of course, we also want to support the vast majority of responsible landlords who provide quality homes to their tenants. That is one of the reasons why this White Paper sets out our commitment to strengthen the grounds for possession where there is good reason for the landlord to take the property back.

Together, these reforms will help to ease the financial burden on renters, reducing moving costs and emergency repair bills. It will reset the tenant-landlord relationship by making sure that complaints are acted upon and resolved quickly. Most importantly, however, the reforms set out in this White Paper fulfil this government’s pledge to level up the quality of housing in all parts of the country so that everyone can live somewhere which is decent, safe and secure - a place they’re truly proud to call home.

Executive summary

The case for change

Everyone deserves a secure and decent home. Our society should prioritise this just like access to a good school or hospital. The role of the Private Rented Sector (PRS) has changed in recent decades, as the sector has doubled in size, with landlords and tenants becoming increasingly diverse. Today, the sector needs to serve renters looking for flexibility and people who need to move quickly to progress their careers, while providing stability and security for young families and older renters. It must also work for a wide range of landlords, from those with a single property through to those with large businesses.

Most people want to buy their own home one day and we are firmly committed to helping Generation Rent to become Generation Buy. We must reduce financial insecurities that prevent renters progressing on the path to home ownership and, in the meantime, renters should have a positive housing experience.

This White Paper builds on the vision of the Levelling Up White Paper and sets out our plans to fundamentally reform the Private Rented Sector and level up housing quality. Most private landlords take their responsibilities seriously, provide housing of a reasonable standard, and treat their tenants fairly. However, it is wrong that, in the 21st century, a fifth of private tenants in England are spending a third of their income on housing that is non-decent.[footnote 1] Category 1 hazards – those that present the highest risk of serious harm or death – exist in 12% of properties, posing an immediate risk to tenants’ health and safety.[footnote 2]

This means some 1.6 million people are living in dangerously low-quality homes, in a state of disrepair, with cold, damp, and mould, and without functioning bathrooms and kitchens.[footnote 3] Yet private landlords who rent out non-decent properties will receive an estimated £3 billion from the state in housing related welfare.[footnote 4] It is time that this ended for good. No one should pay to live in a non-decent home.

Poor-quality housing is holding people back and preventing neighbourhoods from thriving. Damp, and cold homes can make people ill, and cause respiratory conditions. Children in cold homes are twice as likely to suffer from respiratory problems such as asthma and bronchitis.[footnote 5] Homes that overheat in hot summers similarly affect people’s health. In the PRS alone, this costs the NHS around £340 million a year.[footnote 6] Illness, caused or exacerbated by living in a non-decent home, makes it harder for children to engage and achieve well in school, and adults are less productive at work. There is geographical disparity with the highest rates of non-decent homes in Yorkshire and the Humber, the West Midlands and the North West.[footnote 7] Visibly dilapidated houses undermine pride in place and create the conditions for crime, drug-use, and antisocial behaviour.

Too many tenants face a lack of security that hits aspiration and makes life harder for families. Paying rent is likely to be a tenant’s biggest monthly expense and private renters are frequently at the sharpest end of wider affordability pressures. Private renters spend an average of 31% of their household income on rent, more than social renters (27%) or homeowners with mortgages (18%),[footnote 8] reducing the flexibility in their budgets to respond to other rising costs, such as energy.

Frequent home moves are expensive with moving costs of hundreds of pounds.[footnote 9] This makes it harder for renters to save a deposit to buy their own home. Over a fifth (22%) of private renters who moved in 2019 to 2020 did not end their tenancy by choice, including 8% who were asked to leave by their landlord and a further 8% who left because their fixed term ended.[footnote 10] The prospect of being evicted without reason at 2 months’ notice (so called ‘no fault’ Section 21 evictions) can leave tenants feeling anxious and reluctant to challenge poor practice. Families worry about moves that do not align to school terms, and tenants feel they cannot put down roots in their communities or hold down stable employment. Children in insecure housing experience worse educational outcomes, reduced levels of teacher commitment and more disrupted friendship groups, than other children.[footnote 11] In 2019 to 2020, 22% of tenants who wished to complain to their landlord did not do so.[footnote 12] In 2018, Citizens Advice found that if a tenant complained to their local council, they were 5 times more likely to be evicted using Section 21 than those who stayed silent.[footnote 13]

The existing system does not work for responsible landlords or communities either. We must support landlords to act efficiently to tackle antisocial behaviour or deliberate and persistent non-payment of rent, which can harm communities. Many landlords are trying to do the right thing but simply cannot access the information or support that they need to navigate the legal landscape, or they are frustrated by long delays in the courts. In addition, inadequate enforcement is allowing criminal landlords to thrive, causing misery for tenants, and damaging the businesses and reputations of law-abiding landlords.

Collectively, this adds up to a Private Rented Sector that offers the most expensive, least secure, and lowest quality housing to 4.4 million households, including 1.3 million households with children and 382,000 households over 65.[footnote 14] This is driving unacceptable outcomes and holding back some of the most deprived parts of the country.

Our ambition

We are committed to delivering a fairer, more secure, and higher quality Private Rented Sector. We believe:

-

All tenants should have access to a good quality, safe and secure home.

-

All tenants should be able to treat their house as their home and be empowered to challenge poor practice.

-

All landlords should have information on how to comply with their responsibilities and be able to repossess their properties when necessary.

-

Landlords and tenants should be supported by a system that enables effective resolution of issues.

-

Local councils should have strong and effective enforcement tools to crack down on poor practice.

What we have done

We have taken significant action over the past decade to improve private renting. In 2010, 1.4 million rented homes were non-decent, accounting for 37% of the total. This figure has fallen steadily to 1 million homes today (21% of the total).[footnote 15]

To improve safety standards, we have required landlords to provide smoke and carbon monoxide detectors as well as regular electrical safety checks. We supported the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018, which means landlords must not let out homes with serious hazards that leave the dwelling unsuitable for occupation.

To help tenants and landlords in resolving disputes, we made it a requirement in 2014 for letting and managing agents to belong to a government-approved redress scheme. We have also given local councils stronger powers to take action against landlords who do not meet expected standards. We have introduced Banning Orders to drive criminal landlords out of the market, civil penalties of up to £30,000 as an alternative to prosecution, and a database of rogue landlords and agents. Over the last 5 years, we have awarded £6.7 million to over 180 local councils to boost their enforcement work and support innovation.

To reduce financial barriers to private renting, we have capped most tenancy deposits at 5 weeks’ rent and prevented landlords and agents from charging undue or excess letting fees. Between 2010-11 and 2020-21 the proportion of household income (including housing benefit) spent on rent by private renters reduced from 35% to 31%.[footnote 16]

We have taken additional steps to protect private tenants when exceptional circumstances required. During the Coronavirus pandemic our emergency measures helped tenants to remain in their homes by banning bailiff evictions, extending notice periods, and providing unprecedented financial aid. These measures worked. There was a reduction of over 40% in households owed a homelessness duty following the end of an Assured Shorthold Tenancy (AST) in 2020 to 2021 compared with 2019 to 2020,[footnote 17] and repossessions by county court bailiffs between January and March 2022 were down 55% compared to the same quarter in 2019.[footnote 18]

Our 12-point plan of action

While the government’s action over recent years has driven improvements, we know there is more to be done. We are committed to robust and comprehensive changes to create a Private Rented Sector that meets the needs of the diverse tenants and landlords who live and work within it. We have a 12-point plan of action:

-

We will deliver on our levelling up housing mission to halve the number of non-decent rented homes by 2030 and require privately rented homes to meet the Decent Homes Standard for the first time. This will give renters safer, better value homes and remove the blight of poor-quality homes in local communities.

-

We will accelerate quality improvements in the areas that need it most. We will run pilot schemes with a selection of local councils to explore different ways of enforcing standards and work with landlords to speed up adoption of the Decent Homes Standard.

-

We will deliver our manifesto commitment to abolish Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions and deliver a simpler, more secure tenancy structure. A tenancy will only end if the tenant ends it or if the landlord has a valid ground for possession, empowering tenants to challenge poor practice and reducing costs associated with unexpected moves.

-

We will reform grounds for possession to make sure that landlords have effective means to gain possession of their properties when necessary. We will expedite landlords’ ability to evict those who disrupt neighbourhoods through antisocial behaviour and introduce new grounds for persistent arrears and sale of the property.

-

We will only allow increases to rent once per year, end the use of rent review clauses, and improve tenants’ ability to challenge excessive rent increases through the First Tier Tribunal to support people to manage their costs and to remain in their homes.

-

We will strengthen tenants’ ability to hold their landlord to account and introduce a new single Ombudsman that all private landlords must join. This will provide fair, impartial, and binding resolution to many issues and be quicker, cheaper, and less adversarial than the court system. Alongside this, we will consider how we can bolster and expand existing rent repayment orders and enable tenants to be repaid rent for non-decent homes.

-

We will work with the Ministry of Justice and HM Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) to target the areas where there are unacceptable delays in court proceedings. We will also strengthen mediation and alternative dispute resolution to enable landlords and tenants to work together to reduce the risk of issues escalating.

-

We will introduce a new Property Portal to make sure that tenants, landlords and local councils have the information they need. The portal will provide a single ‘front door’ for landlords to understand their responsibilities, tenants will be able to access information about their landlord’s compliance, and local councils will have access to better data to crack down on criminal landlords. Subject to consultation with the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), we also intend to incorporate some of the functionality of the Database of Rogue Landlords, mandating the entry of all eligible landlord offences and making them publicly visible.

-

We will strengthen local councils’ enforcement powers and ability to crack down on criminal landlords by seeking to increase investigative powers and strengthening the fine regime for serious offences. We are also exploring a requirement for local councils to report on their housing enforcement activity and want to recognise those local councils that are doing a good job.

-

We will legislate to make it illegal for landlords or agents to have blanket bans on renting to families with children or those in receipt of benefits and explore if similar action is needed for other vulnerable groups, such as prison leavers. We will improve support to landlords who let to people on benefits, which will reduce barriers for those on the lowest incomes.

-

We will give tenants the right to request a pet in their property, which the landlord must consider and cannot unreasonably refuse. We will also amend the Tenant Fees Act 2019 so that landlords can request that their tenants buy pet insurance.

-

We will work with industry experts to monitor the development of innovative market-led solutions to passport deposits. This will help tenants who struggle to raise a second deposit to move around the PRS more easily and support tenants to save for ownership.

We know action is needed now and the Renters Reform Bill will bring forward legislation in this Parliamentary session to deliver on our wide-reaching commitments. Collectively, this 12-point plan will create a Private Rented Sector that is fit for the 21st century. It will give good landlords the confidence and support they need to provide decent and secure homes. It will end the geographical disparities whereby renters in deprived areas are most likely to have to put up with terrible conditions that harm their health.

This 12-point plan will provide further support for tenants on their path to home ownership, in addition to government-backed schemes such as the new First Homes programme, the new Help to Buy: Equity Loan scheme, Shared Ownership scheme and mortgage guarantee scheme. These schemes have already helped over 774,000 households to purchase a home. We are going further to support home ownership by examining reform of the mortgage market to boost access to finance for first time buyers, extend the Right to Buy to Housing Association tenants, delivering on a long-standing commitment made by several governments, and removing home ownership disincentives in the welfare system. We will accelerate our progress on housing supply by working with communities to build the right homes in the right places across England.

We continue to take on board recommendations from the recent National Audit Office review and Public Accounts Committee report[footnote 19] to inform our ambitious and comprehensive reforms. We are also very grateful to the wide range of stakeholders, tenants, agents, and landlords who have engaged with us, notably through a series of roundtables chaired by Eddie Hughes, Minister for Rough Sleeping and Housing. A summary of these discussions can be found annexed to this White Paper and we look forward to continuing to work with stakeholders to deliver these necessary reforms.

Chapter 1: The private rented sector in England

1.1 Key facts and figures

All data is from DLUHC analysis of English Housing Survey 2020 to 2021, unless otherwise specified.

-

In 2020 to 2021, the Private Rented Sector accounted for 4.4 million (19%) households (65% are owner occupied and 17% are social housing), housing over 11 million people.[footnote 20] While the sector has doubled in size since the early 2000s, the proportion of PRS households has remained stable at around 19% or 20% since 2013 to 2014.

-

Private renters are younger than those in other tenures. In 2020 to 2021, those aged 16 to 34 accounted for 43.5% of private renters in England, with 25 to 34-year-olds the most common age group of private renters at 31%.

-

Adults of retirement age make up 8.6% of private renters, corresponding to 382,000 households. This is a 38% increase over the last decade (since 2010 to 2011).[footnote 21]

-

There are over half a million more households with dependent children in the Private Rented Sector than in 2005, making up 30% of the sector.

-

Private renters spend an average of 31% of their income, including housing support, on rent. In comparison, those buying their home with a mortgage spent 18% of their household income on mortgage payments and social renters paid 27% of their income on rent. Excluding income from housing related welfare, the average proportion of income spent on rent was 36% for social renters and 37% for private renters.

-

73% of private renters are working – 58% of private renters are in full time work and 15% in part-time work. However, 45% of Private Rented Sector households have no savings.

-

In 2020 to 2021, there were an estimated 1.1 million households in England who received Housing Benefit to help with the payment of their rent, representing 26% of all households in the rented sector.

-

There is a wide regional disparity in rental prices. Between October 2020 and September 2021, the average monthly rent in England was £898, but in London this was £1,597. This contrasts with the North East where the average was £572.[footnote 22]

-

On average, private renters have lived in their current home for 4.2 years. This compares with 10.8 years for social renters and 16 years for owner occupiers. Of private renters who had lived in their current home for less than a year, 69% were previously in private rented housing.

-

Currently, 21% of homes in the Private Rented Sector are non-decent. The sector has the highest prevalence of Category 1 hazards – those that present the highest risk of serious harm or death. In 2020, 12% of PRS properties had such hazards, compared to 10% in the owner occupied sector and 5% in the social rented sector.

-

In total there are 333 local councils in England,[footnote 23] which play a vital role in regulating and enforcing compliance in the Private Rented Sector. Councils are made up of London boroughs, 2-tier county and district councils, metropolitan and unitary authorities. In 2-tier authorities, most PRS regulatory functions are run by district councils.

-

Regions in England with the highest percentages of private rented homes as a proportion of their total housing stock are London (27.3%), the South West (20.02%) and Yorkshire and the Humber (19.0%). The national average is 19.4%.[footnote 24]

-

While two-thirds of private renters could afford the monthly costs of the average mortgage, 45% have no savings, and just 9.5% of households have adequate savings to achieve a 95% loan to value mortgage.[footnote 25]

-

The majority of households who moved from a privately rented home ended their last tenancy because they wanted to move. However, more than one-fifth of renters (22%) who moved in the past year did not end their tenancy by choice, including 8% who were asked to leave by their landlord and a further 8% who left because their fixed term ended.[footnote 26]

1.2 The people who live, work, and invest in the PRS

Tenants

- There are an estimated 4.4 million households in the PRS, housing over 11 million people.[footnote 27]

Local councils

- There are a total of 333 local councils in England.[footnote 28]

Landlords

- There are an estimated 2.3 million landlords in England.[footnote 29]

Letting agents

- There are an estimated 19,000 letting agents in England.[footnote 30]

The Private Rented Sector (PRS) has changed in recent decades. The sector has doubled in size and both landlords and tenants have become increasingly diverse. It is still an important home for young professionals and students seeking flexibility but increasing numbers of families and older renters now also look to the sector for a stable and secure home. There is also great variety in landlords. Some are large corporates with equally large portfolios. Others are individuals letting a property as an investment for the future. As the distribution of PRS properties across England varies, the sector can also look and feel different depending on location. The PRS must function well for all those who live and work within it.[footnote 31]

We have undertaken robust analysis to understand the differing outcomes and experiences among private renters and how best we can support them, especially more vulnerable renters.[footnote 32] We have undertaken similar analysis to understand the different types of landlords letting in the PRS.[footnote 33] Detailed analysis through the English Housing Survey and English Private Landlord Survey continue to inform our policy plans and regulatory approach. A summary of this analysis is set out below.

Tenants

Private Rented Sector tenant profiles have changed markedly over the past 30 years. In the 1990s, a PRS tenant was most likely to be a student studying away from home, or a ‘young professional’ renting while saving up to buy their own home. Households with an older Household Reference Person (HRP, which is the person who is responsible for the household or in whose name the property is rented) have increased disproportionately more than those with younger HRPs. In 2020 to 2021, there were 77% more PRS households with a HRP under 35 than in 1995; in 2020 to 2021, there were 157% more households with a HRP aged 35 or older than in 1995.[footnote 34]

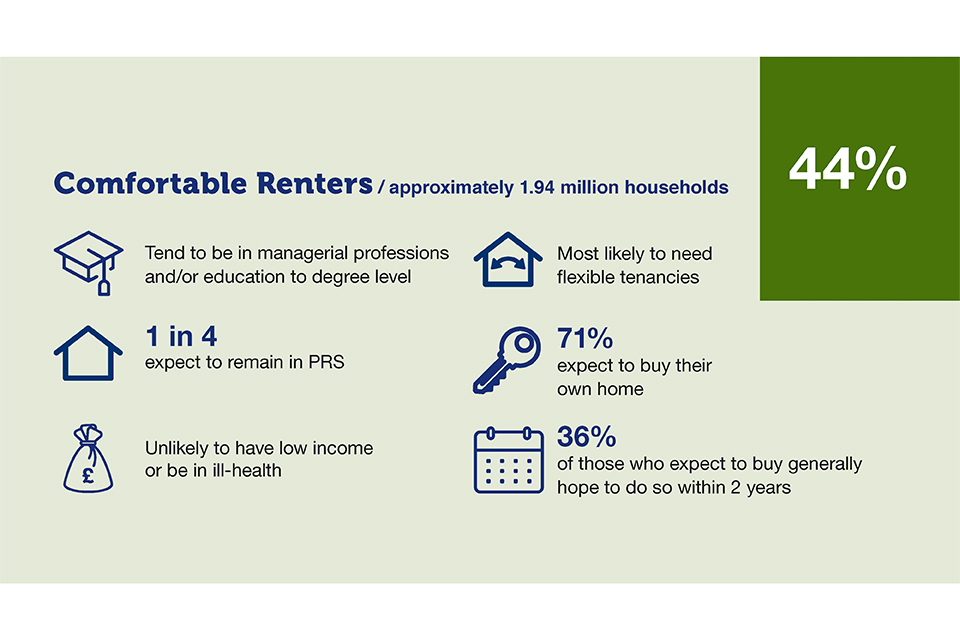

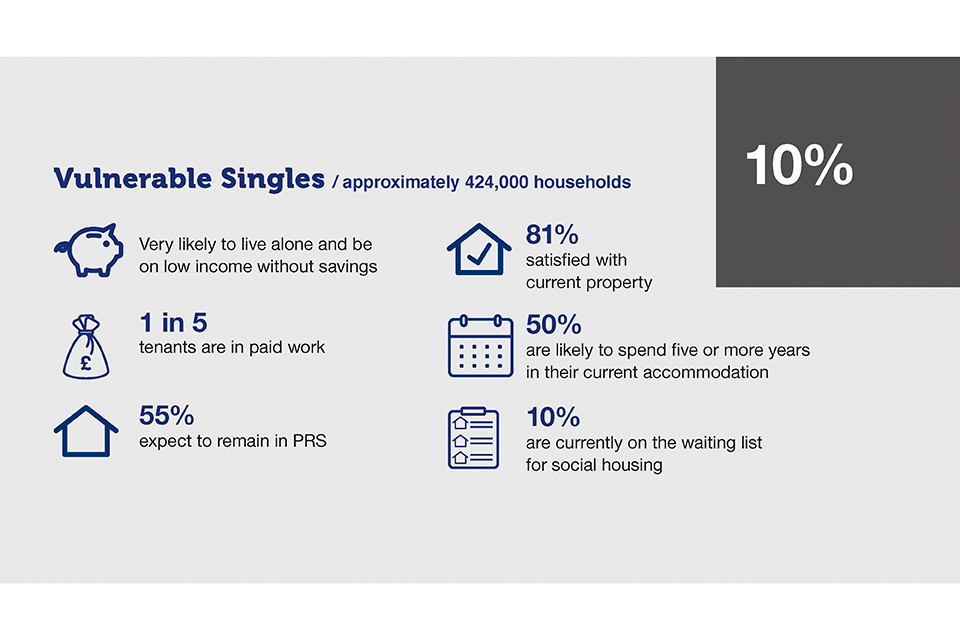

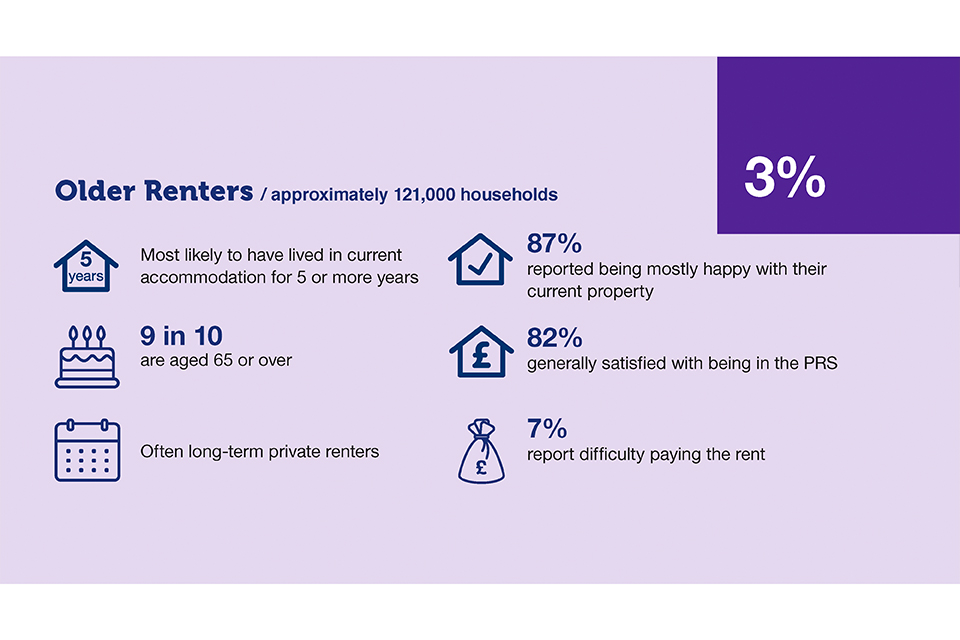

Based on what we know about the financial and housing circumstances of private renters, we can broadly separate them into 6 distinct groups (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Tenant groups, based on English Housing Survey analysis

Comfortable Renters - 44%

- Approximately 1.94 million households

- Tend to be in managerial professions and/or education to degree level

- 1 in 4 expect to remain in PRS

- Unlikely to have low income or be in ill-health

- Most likely to need flexible tenancies

- 71% expect to buy their own home

- 36% of those who expect to buy generally hope to do so within 2 years

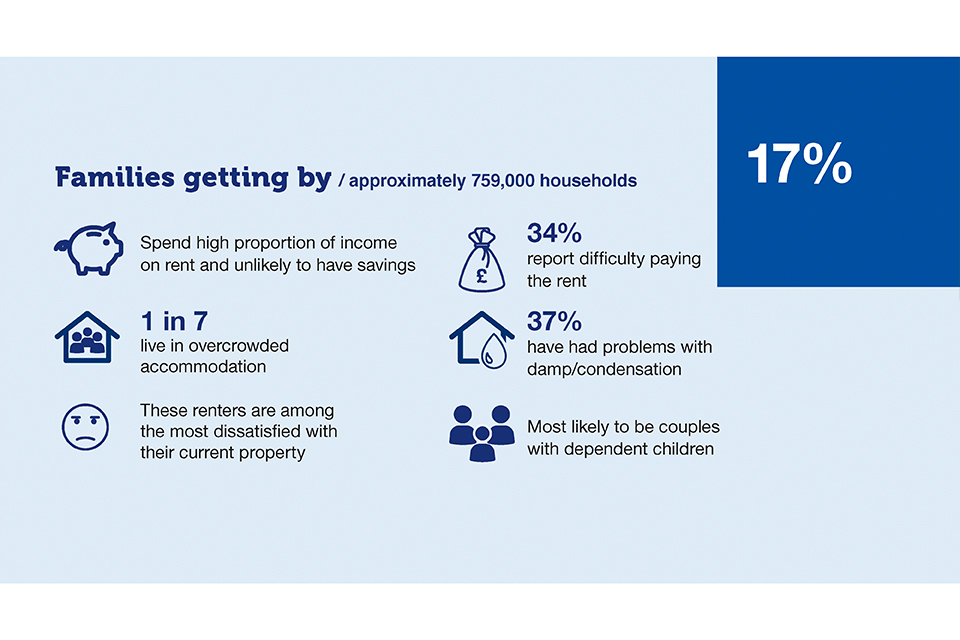

Families getting by - 17%

- Approximately 759,000 households

- Spend high proportion of income on rent and unlikely to have savings

- 1 in 7 live in overcrowded accommodation

- These renters are among the most dissatisfied with their current property

- 34% report difficulty paying the rent

- 37% have had problems with damp/condensation

- Most likely to be couples with dependent children

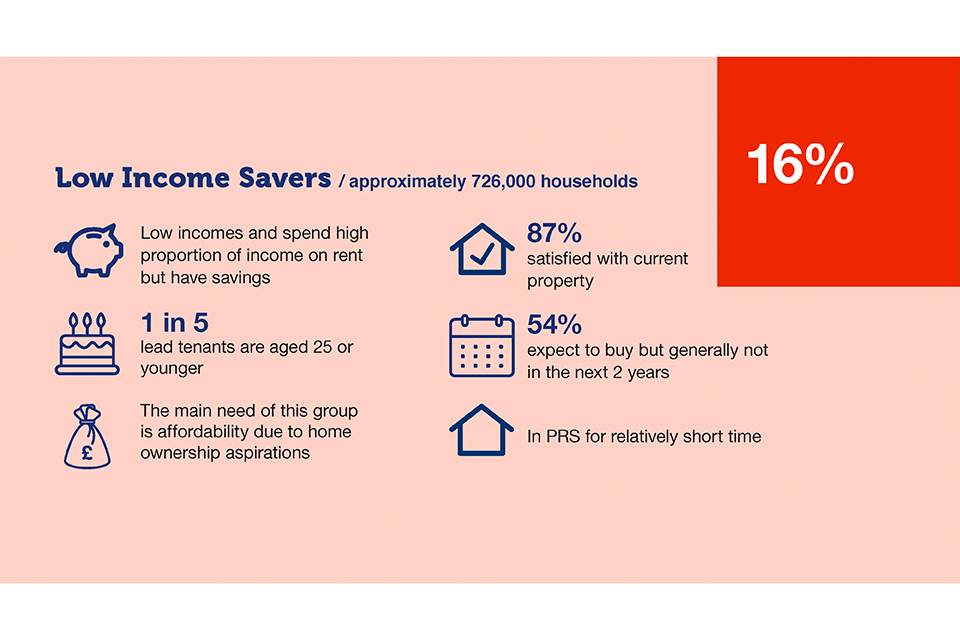

Low Income Savers - 16%

- Approximately 726,000 households

- Low incomes and spend high proportion of income on rent but have savings.

- 1 in 5 lead tenants are aged 25 or younger

- The main need of this group is affordability due to home ownership aspirations

- 87% satisfied with current property

- 54% expect to buy but generally not in the next 2 years

- In PRS for relatively short time

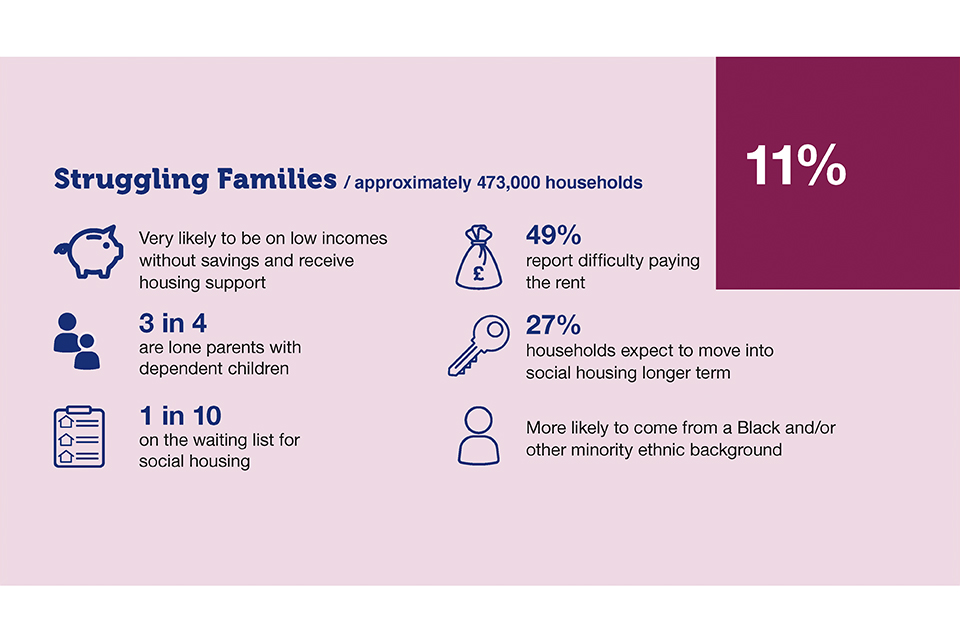

Struggling Families - 11%

- Approximately 473,000 households

- Very likely to be on low incomes without savings and receive housing support

- 3 in 4 are lone parents with dependent children

- 1 in 10 on the waiting list for social housing

- 49% report difficulty paying the rent

- 27% households expect to move into social housing longer term

- More likely to come from a Black and/or other minority ethnic background

Vulnerable Singles - 10%

- Approximately 424,000 households

- Very likely to live alone and be on low income without savings

- 1 in 5 tenants are in paid work

- 55% expect to remain in PRS

- 81% satisfied with current property

- 50% are likely to spend 5 or more years in their current accommodation

- 10% are currently on the waiting list for social housing

Older Renters - 3%

- Approximately 121,000 households

- Most likely to have lived in current accommodation for 5 or more years

- 9 in 10 are aged 65 or over

- Often long-term private renters

- 87% reported being mostly happy with their current property

- 82% generally satisfied with being in the PRS

- 7% report difficulty paying the rent

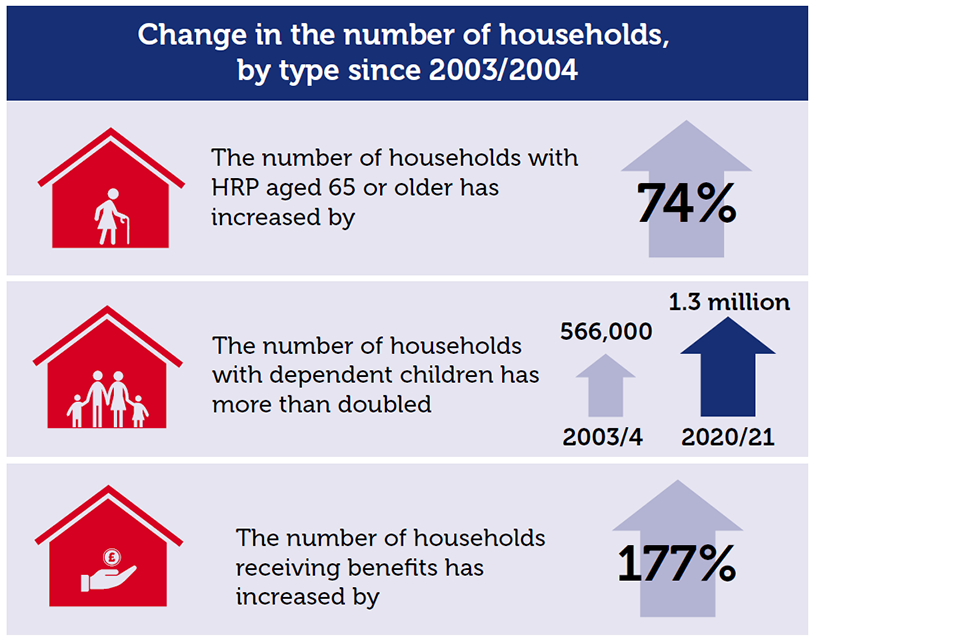

The PRS still provides a vital home for students and young professionals, but as Figure 2 shows, over recent decades there has been an increase in other groups who rent privately. For example, the number of households in the PRS receiving housing related welfare has almost tripled from 411,000 in 2003 to 2003/2004 to 1,140,000 in 2020/2021.[footnote 35] Compared to the 1990s, a PRS tenant in 2020 was, on average, older and much more likely to be living with children, to have reached retirement age, or to be renting on a low income.

Figure 2: Change in the number of households by type since 2003/2004

Change in the number of households, by type since 2003/2004

- The number of households with HRP aged 65 or older has increased by 74%

- The number of households with dependent children has more than doubled. In 2003/4 there were 566,000 households compared to 1.3 million in 2020/21

- The number of households receiving benefits has increased by 177%

(Source: English House Condition Survey 2003/2004 and English Housing Survey 2020/2021)

Landlords

There are approximately 2.3 million landlords operating in England.[footnote 36] Landlords have a range of reasons for letting out properties and this may affect their views on the role of a landlord. While not an exhaustive list, the graphic below describes 5 groups of landlords. We have segmented landlords based on patterns of compliance with legislation and good practice. The data shows that the majority of private landlords meet the legal requirement to rent out a property (54%) and only a small proportion (11%) of landlords have lower levels of compliance and awareness (see figure 3).

Figure 3: Landlord groups, based on English Private Landlord Survey analysis

Demonstrating good practice - 30% of the private landlord population

- Landlords most likely to be compliant with both legislation and good practice indicators

- Most likely get information from a landlord organisation and use this to ensure compliance

- Engaged and knowledgeable about the quality of their portfolio

- Concerned about legislative changes that may affect letting practices

- Property is a significant part of their professional and financial plan

- Aware of legislative changes and carried out relevant legal requirements

Mixed Compliance - 24% of the private landlord population

- Landlords likely to report mixed compliance with legislation, though many comply with good practice indicators

- Has some awareness of regulation changes but overall do not feel as though they have a good understanding of these

- Property is seen as a rental income and pension contribution.

- May not have carried relevant document checks, but would have carried out safety checks.

- A bit more hands-off and may not know all the details of their property

- Not a member of a landlord association and rely on GOV.UK and other online media and their letting agents for information

Meeting Legal Requirement - 35% of the private landlord population

- Landlords likely to be compliant with most legislation, though less likely to be compliant with good practice indicators.

- Engaged and responsible, ensuring all legal and safety requirements have been carried out, especially relating to EPC and safety.

- Aware of upcoming changes that might affect letting practices and have some concerns about legislative changes

- Property is viewed as source of investment income alongside other economic activities

- Get information from GOV.UK, online forum and letting agents

Lower Compliance & Awareness - 11% of the private landlord population

- Landlords least likely to be compliant with either legislation or good practice indicators

- Have limited awareness and knowledge about upcoming tax and regulatory changes

- Gets compliance and regulation information from informal sources

- Most likely to be concerned with tenant behaviour

- Tend not to have complied with various legal requirements or good practice indicators

- In work separate to landlord practice and detachment from property is reflected in letting practice

Criminal landlords

There is evidence of a small number of criminal landlords operating in the Private Rented Sector. The exact number is unknown as the English Private Landlord Survey only covers landlords who enrol in the deposit protection schemes.

-

Often target more vulnerable tenants, who may be less aware SCAM of their rights or unable to act on them

-

Behaviour includes scam lettings, frequent use of illegal eviction, harassment, theft, threats of violence and extreme overcrowding

Letting agents

There are an estimated 19,000 letting agents in England according to data from the Property Ombudsman and the Property Redress Scheme (all letting agents are required to join 1 of these 2 redress schemes).[footnote 37] Agents play an important role in the PRS. They support landlords to understand and comply with their responsibilities and help tenants find a suitable property to rent. The English Private Landlord Survey 2021 found that 49% of landlords did not use an agent, 46% used an agent for letting services and 18% used an agent for management services.[footnote 38]

Local councils

Local councils are responsible for enforcing relevant regulations and working with their local PRS, usually to intervene in poor conditions, poor management, or unlawful evictions. Local councils also have a duty to prevent and relieve homelessness, including by helping families to sustain their tenancies or access new properties.

The government’s New Burdens Doctrine is clear that anything which issues a new expectation on the sector (irrespective of whether it is legislation or guidance) should be assessed for new burdens. DLUHC will conduct a new burdens assessment into the reform proposals set out in this White Paper, assess their impact on local government, and, where necessary, fully fund the net additional cost of all new burdens placed on local councils.

Courts

Courts help to resolve disputes relating to the Private Rented Sector. Cases are primarily heard in 2 locations: the County Court and the First-tier Tribunal (Property Chamber). Examples of cases heard in the County Court include claims for possession by private landlords, claims for unpaid rent or damages by landlords and claims by renters for damages for unlawful/illegal eviction and injunctions. Examples of cases heard by the First-tier Tribunal include appeals by landlords against local council enforcement notices or prohibition orders, and financial penalties for housing offences, Banning Orders, and Rent Repayment Orders (RROs).

Others working in the PRS

As well as seeking legal remedies via the courts, tenants can seek support for resolving disputes from the letting agent redress schemes and deposit protection schemes operating in the Private Rented Sector. Charities and advice organisations, such as Citizens Advice and Shelter, also offer advice and guidance to renters about their landlord or property, and landlords can seek support or guidance about issues relating to their tenants or property from membership bodies such as the National Residential Landlords Association (NRLA).

Chapter 2: Safe and decent homes

We believe:

-

All tenants should have access to a good quality and safe home.

-

No-one should pay rent to live in a substandard, or even dangerous, property.

-

Standards in the Private Rented Sector should go beyond safety – an expectation that already exists in the Social Rented Sector.

-

Landlords should have a clear benchmark for standards in the properties that they let.

We have:

-

Passed regulations in 2015 requiring private landlords to provide smoke detectors and carbon monoxide detectors in all relevant properties.

-

Introduced legislation requiring properties to be fit for human habitation. The Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018 states that landlords must not let out homes with serious hazards that mean the dwelling is not suitable for occupation in that condition.

-

Required privately rented properties meet a minimum energy efficiency standard of EPC E, since 2020, to make it easier for renters to keep their homes warm, while supporting wider aims to make housing more energy efficient.

-

Introduced regulations in 2020 to require landlords to carry out electrical safety checks every 5 years.

We will:

1. Deliver on our Levelling Up housing mission to halve the number of non- decent rented homes by 2030 and require privately rented homes to meet the Decent Homes Standard for the first time.

2. Accelerate quality improvements in the areas that need it most.

Everyone deserves to live in a safe and decent home. Most landlords and agents treat their tenants fairly and provide good quality and safe homes. However, this is not universal practice and too many of the 4.4 million households that rent privately live in poor conditions, paying a large proportion of their income to do so. Poor-quality housing undermines renters’ health and wellbeing, affects educational attainment and productivity, and reduces pride in local areas.[footnote 39] Lower quality homes with poorer, or no, insulation can increase energy bills, adding to the pressures that low-income renters face.

Despite significant improvements over the past decade, over a fifth of privately rented homes (21%) are non-decent, and 12% have serious ‘Category 1’ hazards, which pose an imminent risk to renters’ health and safety.[footnote 40] A greater proportion of non-decent homes are in Yorkshire and the Humber, the West Midlands, and the North West.[footnote 41] Poor housing conditions are putting an unnecessary burden on health spending. It costs the NHS £340 million per year to treat private renters who are affected by non-decent housing.[footnote 42] It is also not acceptable for good landlords to be undercut by those offering a poor-quality home. We are committed to stamping out poor practice and making the PRS fit-for-purpose.

2.1 The Decent Homes Standard in the PRS

The Decent Homes Standard is a regulatory standard in the Social Rented Sector but there is no requirement for PRS properties to meet any standard of decency. It isn’t right that social renters can expect a higher quality home than a private renter.

“It is important that there are set standards across the PRS. I think this will be beneficial to both landlords and tenants.”

Landlord, South East, aged 35-44

We will legislate to introduce a legally binding Decent Homes Standard (DHS) in the Private Rented Sector for the first time. This is a key plank of our ambitious mission to halve the number of non-decent homes across all rented tenures by 2030, with the biggest improvements in the lowest performing areas. We will consult shortly on introducing the Decent Homes Standard into the Private Rented Sector and deliver parity across the rented tenures.

To be ‘decent’ we will require that a home must be free from the most serious health and safety hazards, such as fall risks, fire risks, or carbon monoxide poisoning. It is unacceptable that hazardous conditions should be present in people’s homes when they can be fixed with something as simple as providing a smoke detector or a handrail to a staircase.

Landlords must make sure rented homes don’t fall into disrepair, addressing problems before they deteriorate and require more expensive work. Kitchens and bathrooms should be adequate, located correctly and – where appropriate – not too old, and we’ll also require decent noise insulation. Renters must have clean, appropriate, and useable facilities and landlords should update these facilities when they reach the end of their lives. We will also make sure that rented homes are warm and dry. It is not acceptable that some renters are living in homes that are too cold in winter, too hot in summer, or damp and mouldy.

“I have experienced problems such as damp and mould in my property. After months of the problem not being addressed, I decided to move.”

Tenant, 25-34

Putting a legislative duty on private landlords to meet the Decent Homes Standard will raise standards and make sure that all landlords manage their properties effectively, rather than waiting for a renter to complain or a local council to take enforcement action. We will give local councils the tools to enforce the Decent Homes Standard in the PRS so that they can crack down on non-compliant landlords while protecting the reputation of responsible ones.

As part of the pathway to applying the Decent Homes Standard to the PRS, we will complete our review of the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS). This system is used to assess the seriousness of hazardous conditions (one element of the Decent Homes Standard), including things like fire and falls but also excess cold (which is common in the sector) and excess heat (which is a growing concern in light of the changing climate). The review is due to conclude in autumn 2022. We want to make it easier for landlords and tenants to understand the standards required, supporting increased compliance. The review will streamline the process that local councils take in inspecting properties to assess hazards.

To meet our net zero target, we need to have largely eliminated emissions from our housing stock by 2050. We will need to make significant progress towards that goal over the coming decade to meet our Carbon Budgets. In 2017, the government set out in the Clean Growth Strategy (CGS) its ambition for as many homes as possible to be upgraded to EPC Band C by 2035.[footnote 43] For the PRS, the CGS committed to upgrade as many homes as possible to EPC Band C by 2030, where practical, cost-effective, and affordable. Our collaborative work on Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) in the PRS with the Department for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) will mean warmer, more energy efficient homes. Upgrading energy efficiency to band C produces average cost savings for energy bill payers of approximately £595 per annum (upgrading from EPC band E) or £1,339 per annum (upgrading from EPC F/G).[footnote 44]

We have also announced our intention to introduce new powers for local councils to manage their local supported housing market and take action against poor quality providers, helping ensure residents receive the support they should expect.

These are ambitious reforms, and we will take steps to streamline requirements on landlords. We will consider how best to support good landlords, including phased introductions of reforms where needed. In the longer-term, we are interested in considering whether there is scope to introduce a system of regular, independent checks to make sure that tenants are confident in a property’s condition from the outset; exploring the costs and benefits of an independent regulator for the PRS; and considering the case for further consolidation of existing legislation. These are issues that we are keen to research further and explore with stakeholders.

2.2 Quality improvements in the areas that need it most

We will run pilot schemes with a selection of local councils to trial improvements to the enforcement of existing standards and explore different ways of working with landlords to speed up adoption of the Decent Homes Standard.

We have reinvigorated our engagement programme with a wide range of local councils, and we continue to expand our reach across England. We intend this to be an ongoing collaboration so that we better understand the challenges local councils face. We will use this ongoing engagement to provide enhanced guidance and identify exemplar enforcement approaches to create best practice information to share with all local councils.

Case study: better compliance and raising standards: a partnership with Blackpool

Blackpool has some of the worst housing conditions in the country. Many former bed and breakfast properties have been converted into privately rented homes, with large numbers of poor-quality Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs). One in 3 properties in inner Blackpool are non-decent under current standards, and there are high concentrations of people, often vulnerable, living in poor conditions: the NHS has estimated that hazards relating to poor housing carry a cost of £11 million a year to local health budgets. 80% of private renters in inner Blackpool receive housing support, meaning that many landlords are profiting from housing people in unacceptable conditions at the expense of the welfare budget.

The government is working with Blackpool Council to strengthen enforcement. This will drive up compliance with existing health and safety requirements, penalising or banning landlords who don’t meet basic standards, and gathering information on how rental properties in Blackpool measure up against the reformed Decent Homes Standard.

With funding from DLUHC, the Council will recruit an expanded local enforcement team to tackle exploitation in the local Private Rented Sector and supported housing market, driving up housing quality and protecting the most vulnerable. At the same time, the Council will run an information campaign to make sure that landlords understand their responsibilities and tenants know their rights.

Alongside this enforcement drive, Homes England will join forces with Blackpool Council, using additional funding to explore regeneration opportunities to improve Blackpool’s housing stock and quality of place.

There will also be further support for residents in supported housing, with funding to better standards of support and drive out unscrupulous providers.

To increase quality and value for money in supported housing, we will invest a total of £20 million to fund local councils facing some of the most acute challenges as part of a 3-year Supported Housing Improvement Programme. This programme will provide councils with the capacity and capability they need to address local challenges. Alongside this, we will increase the consistency and impact of local efforts to drive up the quality of supported housing by publishing best practice, based on the approaches that councils found most effective in driving up standards.

Chapter 3: Increased security and more stability

We believe:

-

No tenant should be evicted against their will without proper reason and proportionate notice.

-

Tenants, whatever their circumstances, should have confidence that they can remain in their home and be able to put down roots in their communities.

-

Tenants should be able to move if their life circumstances change or they are unhappy with the property.

-

Landlords should be able to regain possession of their properties efficiently when they have a valid reason to do so.

We have:

-

Introduced a model tenancy agreement to support landlords and tenants to agree longer-term tenancies.

-

Introduced temporary emergency measures during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to sustain tenancies by banning county court bailiff evictions, extending notice periods, working with the judiciary to implement a 6-month stay on possession proceedings and providing unprecedented financial aid.

We will:

3. Abolish Section 21 ‘no fault’ evictions and deliver a simpler, more secure tenancy structure.

4. Reform grounds for possession to make sure that landlords have effective means to gain possession of their property where necessary.

It has become increasingly apparent that the current tenancy system doesn’t always provide the security that those renting privately need or the flexibility to respond to changes in circumstances. This is hitting aspiration and making life harder for families. The lack of security makes it difficult for tenants to challenge poor practice or save for a home of their own. 22% of private tenants who moved from privately rented accommodation between 2019 to 2020 did not end their tenancy by choice, including 8% who were asked to leave by their landlord and a further 8% who left because their fixed term ended,[footnote 45] and nearly half of private renting households have no savings.[footnote 46]

The most common form of tenancy in the PRS is an Assured Shorthold Tenancy (AST). The current tenancy system mixes fixed-term tenancies with periodic tenancies. While this appears to offer choice, these complexities can be difficult to understand, and tenants do not always have the power to negotiate their preference at the outset. Both types of contracts are described in Figure 4.

Figure 4: tenancy types in the Private Rented Sector

Fixed terms commit both landlord and tenant for an agreed period, typically 6 or 12 months.

During a fixed term, landlords cannot use Section 21 to evict a tenant, though they can use other grounds for possession.

Tenants can only leave during a fixed term with the landlord’s agreement, and they must pay rent for the duration, unless agreed otherwise. At the end of a fixed term, tenancies do not automatically end – instead becoming periodic unless a new fixed term is agreed, or notice is served.

Periodic tenancies are weekly or monthly tenancies that do not last for a fixed period. They offer more flexibility to tenants and landlords.

If a tenant wants to leave the property, they are liable for the rent until the required notice period has expired. This is typically 1 month but can vary.

A landlord can end a periodic tenancy with 2 months’ notice by using a Section 21 eviction notice or by using other grounds for possession.

Locking parties into a contract undermines the flexibility that the Private Rented Sector offers and restricts tenants’ and landlords’ ability to react to changing personal circumstances. Similarly, it is wrong that tenants feel unable to challenge poor standards in their home because they worry that their landlord will use Section 21 to evict them, rather than deal with their complaints. In 2018, Citizens Advice found that tenants receiving a Section 21 notice were 5 times more likely to have recently made a complaint to their council compared to those who had not.[footnote 47]

Case study: Section 21 eviction during the winter

David was renting a property in Hastings for just over 8 years with his wife and children. During the course of this tenancy, they didn’t speak to their landlord as any issues were dealt with directly with the letting agency. In November 2021, David received a Section 21 eviction notice from his agency, without explanation. David spent the 2 months notice period struggling to quickly find an affordable and suitable rental property for his family. Moving in the run up to Christmas was hard on his family, especially his children.

The unexpected nature of the eviction put a large amount of stress on the family. His youngest child had spent most of his childhood years in this house and found it hard to leave the place he thought of as home. David felt like the lack of control and power he had when he received the eviction notice was unfair and humiliating. He felt as though his children looked up to their father and relied on him to offer them stability, but that the Section 21 eviction notice meant he was unable to provide this. David, 35-44, South East

For many tenants, the flexibility of the PRS is its attraction, for example those on the cusp of home ownership who want to be able to move quickly when the opportunity arises. For other tenants, a stable tenancy is paramount for employment, education, and social support. Frequent home moves are expensive, costing renters hundreds of pounds, and they must often pay higher rents for the home they move into.[footnote 48] Average asking rents for new properties have risen by 10.8%, with those in London having risen by 14.3% in the 12 months to March 2022.[footnote 49] This can put additional financial pressure on families, meaning they have less money available for a deposit when buying a home or for other essentials such as food or heating. For the most vulnerable, eviction can mean homelessness.

“I’m worried that if I complain to my landlord about a problem with my property, they might increase the rent or even evict me. It is really stressful and expensive to find suitable accommodation in the PRS, so I tend to sort the issue out myself as I don’t want to seem like a ‘bother’ to my landlord.”

Tenant, London, 25-34, focus group.

3.1 Abolish Section 21 evictions and deliver a simpler tenancy structure

We will abolish Section 21 evictions and simplify tenancy structures. To achieve this, we will move all tenants who would previously have had an Assured Tenancy or Assured Shorthold Tenancy onto a single system of periodic tenancies. This will provide greater security for tenants while retaining the important flexibility that privately rented accommodation offers. This will enable tenants to leave poor quality properties without remaining liable for the rent or to move more easily when their circumstances change, for example to take up a new job opportunity. Tenants will need to provide 2 months’ notice when leaving a tenancy, ensuring landlords recoup the costs of finding a tenant and avoid lengthy void periods. Landlords will only be able to evict a tenant in reasonable circumstances, which will be defined in law, supporting tenants to save with fewer unwanted moves. Removing Section 21 will level the playing field between landlord and tenant, empowering tenants to challenge poor practice and unjustified rent increases, as well as incentivising landlords to engage and resolve issues. With a single tenancy structure, both parties will better understand their rights and responsibilities.

“If both the landlord and tenant adhere to their responsibilities, longer tenancies are beneficial for both parties. It provides tenants with the stability of knowing they can stay in the property, while landlords do not have to worry about their property being vacant.”

Landlord, East Midlands, 45-54

Section 21 and Assured Shorthold Tenancies are used by a range of housing sectors. Most students will continue to move property at the end of the academic year. However, for certain students, this is not appropriate, for example because they have local ties or a family to support. It is important that students have the same opportunity to live in a secure home and challenge poor standards as others in the PRS. Therefore, students renting in the general private rental market will be included within the reforms, maintaining consistency across the PRS. We recognise, however, that Purpose-Built Student Accommodation cannot typically be let to non-students, and we will exempt these properties – with tenancies instead governed by the Protection from Eviction Act 1977 - so long as the provider is registered for a government-approved code.[footnote 50]

We will allow time for a smooth transition to the new system, supporting tenants, landlords and agents to adjust, while making sure that tenants can benefit from the new system as soon as possible. We will implement the new system in 2 stages, ensuring all stakeholders have sufficient notice to implement the necessary changes.

We will provide at least 6 months’ notice of our first implementation date, after which all new tenancies will be periodic and governed by the new rules. Specific timing will depend on when Royal Assent is secured. To avoid a 2-tier rental sector, and to make sure landlords and tenants are clear on their rights, all existing tenancies will transition to the new system on a second implementation date. After this point, all tenants will be protected from Section 21 eviction. We will allow at least 12 months between the first and second dates.

The government is clear that misuse of the system or any attempt to find loopholes will not be tolerated, and the reforms that we are putting in place for tenants will only make a difference if they are effectively enforced. We will consider the case for new or strengthened penalties to support existing measures, including the power for councils to issue Civil Penalties Notices for offences related to the new tenancy system. We will also explore how to help local councils in tackling illegal evictions.

Tenants in the PRS are protected from illegal evictions and harassment under the Protection from Eviction Act 1977. Local councils and the police have enforcement powers to investigate cases of illegal evictions and harassment and can prosecute where an offence has been committed. We understand, however, that successful prosecutions are rare and there is a great deal of variation in enforcement practice across the country. We recognise the need to clamp down on illegal evictions and ensure that the statutory framework is robust so that we can protect tenants. We will consider if amendments to the Protection from Eviction Act 1977 are necessary to help local authorities in tackling illegal evictions, for example permitting local councils to issue civil penalties for cases of illegal evictions and harassment; how we can support local councils to work effectively with the police; and how to ensure penalties reflect the serious impact that illegal eviction has on tenants.

3.2 Reformed grounds for possession

The system must work for responsible landlords, letting agents, and communities. Landlords who maintain good letting practices and standards are a valuable part of our housing market and must be able to regain possession of their properties when necessary. We will reform grounds of possession so that they are comprehensive, fair, and efficient, striking a balance between protecting tenants’ security and landlords’ right to manage their property.

Recognising that landlords’ circumstances can change, we will introduce a new ground for landlords who wish to sell their property and allow landlords and their close family members to move into a rental property. We will not allow the use of these grounds in the first 6 months of a tenancy, replicating the existing restrictions on when Section 21 can be used. This will provide security to tenants while ensuring landlords have flexibility to respond to changes in their personal circumstances.

Landlords have raised concerns that some tenants pay off a small amount of arrears – taking them just below the mandatory repossession threshold of 2 months’ arrears (which must be demonstrated both at time of serving notice and hearing) - to avoid eviction at a court hearing. Where tenants do this repeatedly it represents an unfair financial burden on landlords in lost rent and court costs and indicates that a tenancy may be unsustainable for a tenant. We will introduce a new mandatory ground for repeated serious arrears. Eviction will be mandatory where a tenant has been in at least 2 months’ rent arrears 3 times within the previous 3 years, regardless of the arrears balance at hearing. This supports landlords facing undue burdens, while making sure that tenants with longstanding tenancies are not evicted due to one-off financial shocks that occur years apart.

We will increase the notice period for the existing rent arrears eviction ground to 4 weeks and will retain the mandatory threshold at 2 months’ arrears at time of serving notice and hearing. This will make sure that tenants have reasonable opportunity to pay off arrears without losing their home. We recognise that tenants may sometimes breach the relevant thresholds for the mandatory rent arrears grounds because of the timing of their welfare payments. This could occur, for instance, because a relevant benefits payment – which the tenant has been assessed as entitled to – has not yet been paid out. We will prevent tenants in this scenario from being evicted, provided it is the reason they have exceeded the mandatory rent arrears threshold.

In cases of criminal behaviour or serious antisocial behaviour, we will lower the notice period for the existing mandatory eviction ground and explore whether further guidance would help landlords and tenants to resolve issues at an earlier stage.

We will introduce new, specialist grounds for possession to make sure that those providing supported and temporary accommodation can continue to deliver vital services. We will also ensure that Private Registered Providers continue to have access to the same range of grounds as private landlords and the agriculture sector can continue to function through grounds to support rural employment.

We know that when landlords pursue possession, they want a reasonable degree of certainty about the outcome. As far as possible, we have defined grounds unambiguously – so landlords can have certainty that the grounds will be met when going to court – and made them mandatory where it is reasonable to award possession. This means judges must grant possession if the landlord can prove that the ground has been met.

We will take a proportionate approach to the period of notice that a landlord must give when seeking possession. Tenants must be given sufficient time to find appropriate alternative housing when their landlord requires possession of a property. Equally, in some circumstances tenancies must end quickly, such as where a landlord faces undue burdens or there is a serious risk to community safety. We will require 2 months’ notice in circumstances beyond a tenant’s control, such as the landlord selling, with less notice required for rent arrears and serious tenant fault.

Further details on the new tenancy system, including how we will ensure effective enforcement of the new tenancy system and reforms to the grounds for possession, can be found in our response to the 2019 consultation on abolishing Section 21, which has been published alongside this White Paper on GOV.UK.[footnote 51]

Chapter 4: Improved dispute resolution

We believe:

-

All tenants should be empowered to challenge poor practice by their landlord, including unjustified rent increases.

-

Landlords and tenants should be supported by a system that enables effective resolution of issues.

We have:

-

Required letting and managing agents to belong to a government-approved redress scheme (The Property Ombudsman or The Property Redress Scheme) since 2014.

-

Introduced Tenancy Deposit Protection Schemes in 2007 to resolve end-of-tenancy deposit disputes.

-

Run a 9-month Rental Mediation Pilot scheme last year, which offered landlords and renters access to free, independent mediation as part of the court process for possession.

We will:

5. Only allow increases to rent once per year, end the use of rent review clauses, and improve tenants’ ability to challenge excessive rent increases through the First Tier Tribunal.

6. Strengthen tenants’ ability to hold landlords to account and introduce a new single Ombudsman that all private landlords must join.

7. Work with the Ministry of Justice and HM Courts and Tribunal Service (HMCTS) to target the areas where there are unacceptable delays in court proceedings.

With tenants empowered by the removal of ‘no fault’ Section 21 evictions, we expect dispute resolution to be more attractive, fostering certainty and security for both landlord and tenant. Many tenants and landlords work effectively together to resolve issues. However, where this is not possible, there are limited options for resolving disputes. This means simple disputes can escalate unnecessarily, often ending up in expensive, protracted, and adversarial court proceedings that harm both the landlord and the tenant.

Redress is the norm in other consumer sectors, such as finance, legal, energy, and the communications industry, but the PRS is falling behind other housing tenures. The Housing Ombudsman provides mandatory redress for all social tenants on the full range of issues concerning their tenancies. Redress schemes also exist in leasehold for managing and estate agents, and provision for the New Homes Ombudsman scheme is included in the Building Safety Act 2022. Private landlords can voluntarily join an agent redress scheme or the Housing Ombudsman but, at the time of publishing, this covers approximately 80 to 90 private landlords out of an estimated 2.3million.[footnote 52]

Private tenants can access redress where they have a complaint about their letting agent or managing agent. However, issues that are the responsibility of the landlord (such as conduct, repairs and conditions) are typically outside the remit of these schemes. We are committed to building on this work by mainstreaming early, effective, and efficient dispute resolution throughout the PRS.

“It takes such a long time for repair works to be done, I sometimes don’t bother asking my landlord.”

Tenant, London, 25-34

The vast majority of tenancy disputes do not end up in court,[footnote 53] but we accept that there are insufficient incentives or support for landlords to resolve disputes earlier. Where court action is necessary it should be transparent, fair, and efficient. We know that many landlords are frustrated by long delays in the courts and that court and tribunal processes can be challenging and intimidating for tenants to navigate.

4.1 Challenging unjustified rent increases

We understand the pressures people are facing with the cost of living, and that paying rent is likely to be a tenant’s biggest monthly expense. Almost 11,000 households in the Private Rented Sector reported moving recently because their landlord put up the rent.[footnote 54] Any unexpected changes to rent levels could leave tenants unable to afford their home and can impact a tenant’s ability to save for a home of their own. Finding new tenants is a significant cost for landlords too, and we strongly encourage early communication about what adjustments to rent are possible and sustainable for both landlords and tenants.

This government does not support the introduction of rent controls to set the level of rent at the outset of a tenancy. Historical evidence suggests that this would discourage investment in the sector and would lead to declining property standards as a result, which would not help landlords or tenants.

When a landlord needs to adjust rent, changes should be predictable and allow time for a tenant to consider their options. We will only allow increases to rent once per year (replicating existing mechanisms) and will increase the minimum notice landlords must provide of any change in rent to 2 months. We will end the use of rent review clauses, preventing tenants being locked into automatic rent increases that are vague or may not reflect changes in the market price. Any attempts to evict tenants through unjustifiable rent increases are unacceptable. Most landlords do not increase rents by an unreasonable amount but in cases where increases are disproportionate, we will make sure that tenants have the confidence to challenge unjustified rent increases through the First-tier Tribunal. We will prevent the Tribunal increasing rent beyond the amount landlords initially asked for when they proposed a rent increase.

Landlords charging multiple months’ rent in advance of a tenancy starting is currently uncommon, as for most tenants this will be unaffordable. Typically, landlords may choose to do so where tenants do not have guarantors, are moving to the UK from abroad, or cannot provide references. We will require landlords to repay any upfront rent if a tenancy ends earlier than the period that tenants have paid for. We will also introduce a power through the Renters Reform Bill to limit the amount of rent that landlords can ask for in advance. We will use this power if the practice of charging rent in advance becomes widespread or disproportionate.

Abolishing Section 21 will empower tenants to seek Rent Repayment Orders where appropriate. We understand that in exceptional circumstances tenants can be timed out in making an application for a Rent Repayment Order, and that in rent-to-rent cases it is not easy to know which landlord should be pursued and superior landlords can be let off the hook. We plan to bolster the existing system where appropriate and expand Rent Repayment Orders to cover repayment for non-decent homes. Periodic tenancies will also enable tenants to leave easily without remaining liable for the rent in unsuitable and unsafe accommodation.

Additionally, the government has introduced the Debt Respite Scheme (Breathing Space) to give eligible people in problem debt access to a 60-day period in which most interest, fees and charges are frozen. Enforcement action, including repossession due to rent arrears, are paused whilst they receive advice. Breathing spaces give debtors the time and space to fully engage with professional debt advisers to identify a positive and sustainable solution to their problem debt. This also means that they are less likely to sink into a cycle of debt, with their creditors more likely to receive higher repayments and spend less on recovery costs.

Case study: rent increases

Sue has been a landlord for 22 years and is based in Hastings. She owns 8 properties on the south coast and mostly lets to families with children. In March 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 lock-down, a family of 5 who were renting 1 of her 3-bedroom properties were especially badly hit by the pandemic restrictions. Unfortunately, both parents were furloughed and significantly affected financially. As a direct consequence of the pandemic, their household income was reduced overnight, making it very difficult to support a family with 3 children. Working with her tenants, Sue agreed to defer payment of her mortgage for 3 months in order allow her to be flexible about rent payments in the short-term and to relieve some of the family’s financial pressures. Fortunately, both parents were able to resume work after 4 months of furlough and Sue agreed a repayment plan, allowing the family to paydown their rent arrears in £50 instalments. Happily, the same family continue to make their home in her 3-bedroom property, and have since agreed a 2-year rent freeze to provide some stability as they recover financially.

Commenting on the relationship she has with her tenants, Sue said: “The pandemic affected so many families, and the last thing I wanted to do was put pressure on them to pay their rent. I’ve agreed a 2 year no rent increase, due to the fact that the cost of living has significantly increased, and to make sure the family are financially comfortable. They’re great tenants and I want them to be happy”. Sue, 50, South East

4.2 A new Ombudsman covering all private landlords

The government is committed to making sure that PRS tenants have the same access to redress as those living in other types of housing.[footnote 55] That is why we will introduce a single government-approved Ombudsman covering all private landlords who rent out property in England, regardless of whether they use an agent. This will ensure that all tenants have access to redress services in any given situation, and that landlords remain accountable for their own conduct and legal responsibilities. Making membership of an Ombudsman scheme mandatory for landlords who use managing agents will mitigate the situation where a good agent is trying to remedy a complaint but is reliant on a landlord who is refusing to engage.

Ombudsmen protect consumer rights. They provide fair, impartial, and binding resolutions for many issues without resorting to court. This will be quicker, cheaper, less adversarial, and more proportionate than the court system. A single scheme will mean a streamlined service for tenants and landlords, avoiding the confusion and perverse incentives resulting from competitive schemes. As well as resolving individual disputes, an Ombudsman can tackle the root cause of problems, address systemic issues, provide feedback and education to members and consumers, and offer support for vulnerable consumers. We will explore streamlining the requirement for landlords to provide details to both an Ombudsman and a digital Property Portal, including identifying a viable way to link datasets (detail on the Property Portal is in chapter 5).

“It is vital to have a positive relationship with your tenants based on open and frequent communication. This makes tenants feel comfortable reporting any issues to you. Likewise, as a landlord you understand your tenants and know that your property will be respected and looked after.”

Landlord, South East, 35-44

The new Ombudsman will allow tenants to seek redress for free, where they have a complaint about their tenancy. This could include complaints about the behaviour of the landlord, the standards of the property or where repairs have not been completed within a reasonable timeframe. We will make membership of the Ombudsman mandatory and local councils will be able to take enforcement action against landlords that fail to join the Ombudsman.

The Ombudsman will have powers to put things right for tenants, including compelling landlords to issue an apology, provide information, take remedial action, and/or pay compensation of up to £25,000. As part of providing compensation, we also intend for the Ombudsman to be able to require landlords to reimburse rent to tenants where the service or standard of property they provide falls short of the mark. In keeping with standard practice, the Ombudsman’s decision will be binding on landlords, should the complainant accept the final determination. Failure to comply with a decision may result in repeat or serious offenders being liable for a Banning Order. The government will also retain discretionary powers to enable the Ombudsman’s decisions to be enforced through the Courts if levels of compliance become a concern.

“I have had issues with my landlords in the past, but I don’t know who to complain to or how. If there was a process available, I would consider using it. I think this would also help to raise standards and make tenants feel more empowered. Tenants are essentially paying landlords for a service, so it is important that landlords adhere to the correct standards.”

Tenant, South East, 25-34

We will explore extending mandatory membership of a redress scheme to residential park home operators, private providers of purpose-built student accommodation and property guardian companies. This would provide access to redress for residents across approximately 2,000 park homes sites in England, 30% of university students living in purpose-built student accommodation,[footnote 56] and approximately 5,000 to 7,000 property guardians.[footnote 57]

4.3 A more efficient court process

Better access to redress at an earlier stage through the new Ombudsman will free up time for the courts to deal with the most serious cases, and we expect those cases to progress through the courts more quickly as a result. However, we are mindful that any changes to court processes must still allow sufficient time to access legal advice where necessary.

In our 2018 Call for Evidence to consider the case for a Housing Court, the 2 main areas of dissatisfaction private landlords raised were timeliness and the complexity of the County Court system. More than 90% of landlords who responded said that they had experienced delays when taking court action for possession. 95% indicated that the period between obtaining an order for possession and enforcement by county court bailiffs (who are HMCTS employees) took too long. While almost 80% of landlords indicated that they knew how the possession action process worked, the complexity of the process was their second biggest concern and more than 40% stated that they found the stage of the process between application and hearing to be too complex.[footnote 58]

The costs of introducing a new housing court would outweigh the benefits and there are more effective ways to increase the efficiency and timeliness of the court possession action process. Working in partnership with the Ministry of Justice (MOJ) and HM Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS), we will introduce a package of wide-ranging court reforms that will target the areas that particularly frustrate and hold up possession proceedings. These are county court bailiff capacity, paper-based processes, a lack of adequate advice about court and tribunal processes, and a lack of prioritisation of cases.

HMCTS have already taken steps to review county court bailiff capacity and introduced efficiencies by reducing administrative tasks. HMCTS have also introduced new payment options to increase the ways a Defendant can make payments to county court bailiffs, reducing the need for doorstep visits to enforce payment. This will continue to free up more county court bailiff resources to focus on the enforcement of possession orders.

We will go further to increase the efficiency and ease of the court possession process. The HMCTS Reform Programme has provided the opportunity to digitise a range of court and tribunal processes, resulting in better advice and guidance. This will reduce common user errors and enhance the user experience. Reforms to the possession process commenced in April 2022 and the project is expected to conclude in 2023. The reforms will provide the opportunity to review and implement improvements and provide HMCTS with better data to enhance performance and respond to user experience and feedback.

We will work with the courts to consider the prioritisation of certain cases, including exploring the feasibility of particular cases being listed as urgent.[footnote 59] We will consider how to expedite cases involving serious harm, including antisocial behaviour or where grounds are critical to the functioning of sectors such as temporary accommodation.

The Ministry of Justice will also trial a new system in the First-tier Tribunal (property chamber) to streamline how specialist property cases are dealt with where there is split jurisdiction between the civil courts and property tribunal. This would provide a single judicial forum for these types of cases, removing the need of litigants to deal with 2 judicial forums to determine a single case, reduce costs, and simplify the process in pilot areas. The Ministry of Justice will review the success of these trials and set out next steps in due course.

The Ministry of Justice is improving the provision of earlier access to legal advice for renters through the Housing Possession Court Duty Scheme,[footnote 60] to deliver more effective early legal advice for debt, housing, and welfare benefit matters, as announced in the Legal Support Action Plan.[footnote 61] The government’s response to the consultation was recently published on GOV.UK.[footnote 62]