Particulate matter (PM10/PM2.5)

Updated 27 June 2025

Accredited Official Statistics

Air quality statistics in the UK, 1987 to 2024 - Particulate matter (PM10/PM2.5)

Updated 26 June 2025

1. Why measure PM?

Particulate matter (PM) is everything in the air that is not a gas and therefore consists of a huge variety of chemical compounds and materials, some of which can be toxic. Due to the small size of many of the particles that form PM some of these toxins may enter the bloodstream and be transported around the body, lodging in the heart, brain and other organs. Therefore, exposure to PM can result in serious impacts to health, especially in vulnerable groups of people such as the young, elderly, and those with respiratory problems. As a result, particulates are classified according to size. The UK is currently focused on measuring the fractions of PM where particles are less than 10 micrometres in diameter (PM10) and less than 2.5 micrometres in diameter (PM2.5) based on the latest evidence for the effects of PM on health.

Both PM and the precursor pollutants that can form it can travel large distances in the atmosphere. A small proportion of the concentrations of PM that people in the UK are exposed to come from naturally occurring sources such as pollen and sea spray (approximately 15 per cent). Another third is transported to the UK from other European countries and international shipping. However, around half of UK concentrations of PM comes from anthropogenic sources in the UK such as domestic wood burning and tyre and brake wear from vehicles. As such, it is in the interest of the UK to measure concentrations of PM as close to these sources of anthropogenic emissions as possible in order to effectively assess exposure to PM that can be tackled via UK policies.

The Air Quality Standards Regulations 2010 require that concentrations of PM in the UK must not exceed:

-

An annual average of 40 µg/m3 for PM10;

-

A 24-hour average of 50 µg/m3 more than 35 times in a single year for PM10;

-

An annual average of 20 µg/m3 for PM2.5.

The annual compliance assessment, released in September covering the previous calendar year, provides detail on compliance across the UK at a zone level.

The Environmental Targets (Fine Particulate Matter) (England) Regulations 2023 require that in England by the end of 2040:

-

An annual average of 10 µg/m3 for PM2.5 is not exceeded at any monitoring station.

-

Population exposure to PM2.5 is at least 35 per cent less than in 2018.

Population exposure refers to the average concentration someone in England is exposed to and is based on urban or in some case suburban background measurements which are representative of the type of environment most people live and work in.

The Environmental Improvement Plan 2023 for England set interim targets to be met by January 2028:

-

An annual average of 12 µg/m3 for PM2.5 is not exceeded at any monitoring station.

-

Population exposure to PM2.5 is at least 22 per cent less than in 2018.

These interim targets are currently under review. Any updates will be available in the latest Environmental Improvement Plan set to be published later in 2025.

From the 2026 release, an assessment of progress towards the two PM2.5 Environmental Targets will be included in this publication.

2. Trends in concentrations of PM10 in the UK, 1992 to 2024

2.1 Annual mean concentrations of PM10 in the UK, 1992 to 2024

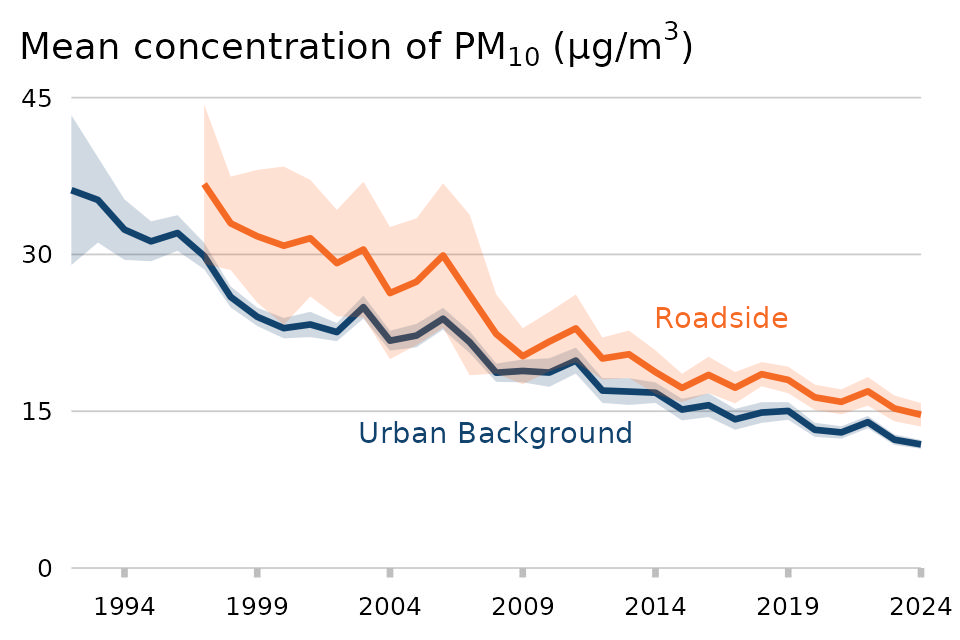

The PM10 index shows the annual mean, averaged over all included sites that had annual data capture greater than or equal to 75 per cent. The shaded areas represent the 95 per cent confidence interval for the annual mean concentration for roadside sites and urban background sites. These intervals narrow over time because of an increase in the number of monitoring sites for both roadside and urban background sites; and a reduction in the variation between annual means for PM10 measured at roadside sites. Annual means for individual sites can be found in the PM10 statistical tables that accompany this report.

Figure 5: Annual mean concentrations of PM10 in the UK, 1992 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

Urban background PM10 pollution has reduced in the long-term despite periods of little change in 2000-2006 and 2015-2019. There has been an overall decrease in annual mean concentrations of PM10 at urban background sites from 36.1 µg/m3 in 1992 to 11.8 µg/m3 in 2024, the lowest recorded.

Between 1992 and 2000 inclusive, the annual mean PM10 concentration at urban background sites rapidly decreased by an average of 1.7 µg/m3 each year. This reduction was observed at most monitoring sites across the UK and is at least partly linked to the large reduction in emissions of PM10 over the same period in the UK and Europe.

Between 2000 and 2006 the annual mean concentration fluctuated with no clear trend, and this was observed at most monitoring sites across the UK. Emissions of PM10 in the UK and Europe were still decreasing over this period but the reductions were largely driven by changes to fuels used for energy generation which may have a minimal impact on urban air quality.

Between 2006 and 2015 inclusive, the annual mean PM10 concentration at urban background sites decreased by an average of 1.0 µg/m3 each year. Concentration levels then plateaued from 2015 to 2019, after which there was a notable decrease of 12 per cent to 13.2 µg/m3 in 2020. Since then, concentrations have remained below pre-2020 levels and generally continued to fall to historically low levels, despite rising slightly in 2022.

Roadside PM10 pollution has reduced in the long-term despite a period of little change between 2015 and 2019. Annual average concentrations of PM10 at the roadside steadily declined from 36.7 µg/m3 in 1997 to 17.2 µg/m3 in 2015. Between 1997 and 2015 inclusive, the annual mean PM10 concentration at roadside sites decreased by an average of 1.1 µg/m3 each year. This reduction was observed at most long-running monitoring sites across the UK. This reduction is in part linked to the large reduction in emissions of PM10 over the same period in the UK, particularly from road transport sources.

Concentrations of PM10 at the roadside remained relatively unchanged between 2015 and 2019 before falling slightly in 2020 to 16.3 µg/m3. Since then, concentrations have remained below pre-2020 levels and generally continued to fall, despite rising slightly in 2022. Concentrations in 2024 were 14.7µg/m3, the lowest recorded.

The annual mean PM10 concentration in 2024 is greater at roadside sites compared to urban background sites. This is most likely due to the contribution of PM10 emissions from road transport sources, predominantly from non-exhaust sources (brakes, tyres and road wear), as well as the impact of resuspension due to vehicle movements.

3. Trends in concentrations of PM2.5 in the UK, 2009 to 2024

3.1 Annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 in the UK, 2009 to 2024

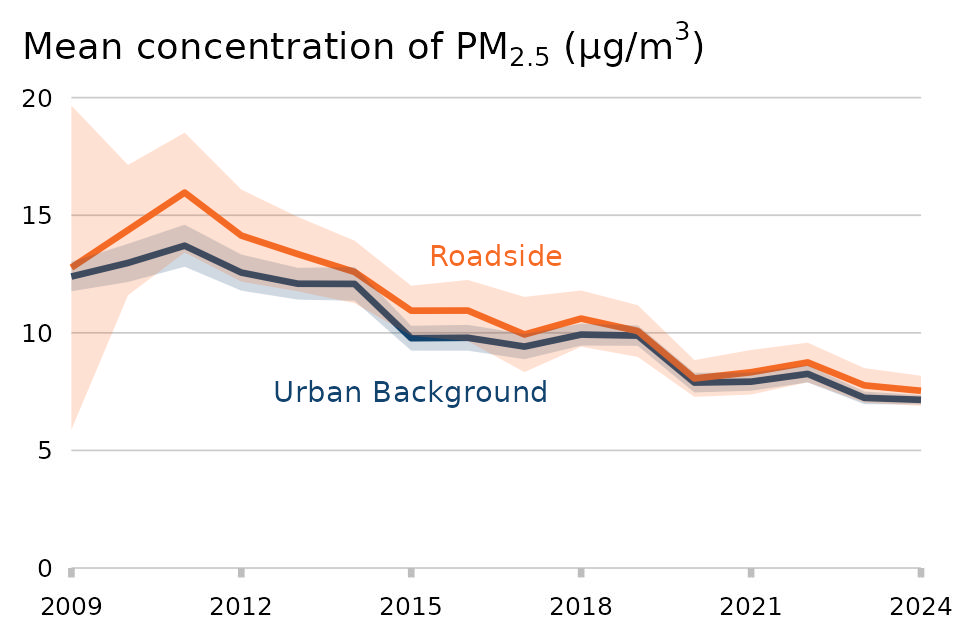

The PM2.5 index shows the annual mean, averaged over all included sites that had annual data capture greater than or equal to 75 per cent. The shaded areas represent the 95 per cent confidence interval for the annual mean concentration for roadside sites and urban background sites. The interval for roadside sites narrows over time because of an increase in the number of monitoring sites and a reduction in the variation between annual means for PM2.5 measured at roadside sites. Annual means for individual sites can be found in the PM2.5 statistical tables that accompany this report.

Figure 6: Annual concentrations of PM2.5 in the UK, 2009 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

Urban background PM2.5 pollution has generally decreased despite a period of little change between 2015 and 2019

In general, annual average concentrations of PM2.5 at urban background sites have decreased from 12.4 µg/m3 in 2009 to 7.2 µg/m3 in 2024, the lowest recorded. The decline in concentrations of PM2.5 at urban background sites approximately follows the trends seen for PM10 at urban background sites (PM2.5 is a subset of PM10).

Concentrations increased between 2009 and 2011, then a downward trend began towards 2015 followed by a period of relatively little change through to 2019. Concentrations then were lower in 2020 and have remained relatively stable since. In 2024, mean concentrations decreased by 1 per cent from 2023 levels.

Roadside PM2.5 pollution has generally decreased despite a period of little change between 2015 and 2019.

In general, annual mean concentrations of PM2.5 at the roadside have decreased from 12.8 µg/m3 in 2009 to 7.5 µg/m3 in 2024, the lowest level recorded. The decline in concentrations of PM2.5 at roadside sites approximately follows the trends seen for PM10 at roadside sites (PM2.5 is a subset of PM10).

There were 2 roadside monitoring sites in 2024 which recorded an annual mean greater than the maximum mean captured by any urban background monitoring site.

4. Average hours spent in ‘Moderate’ or higher PM pollution

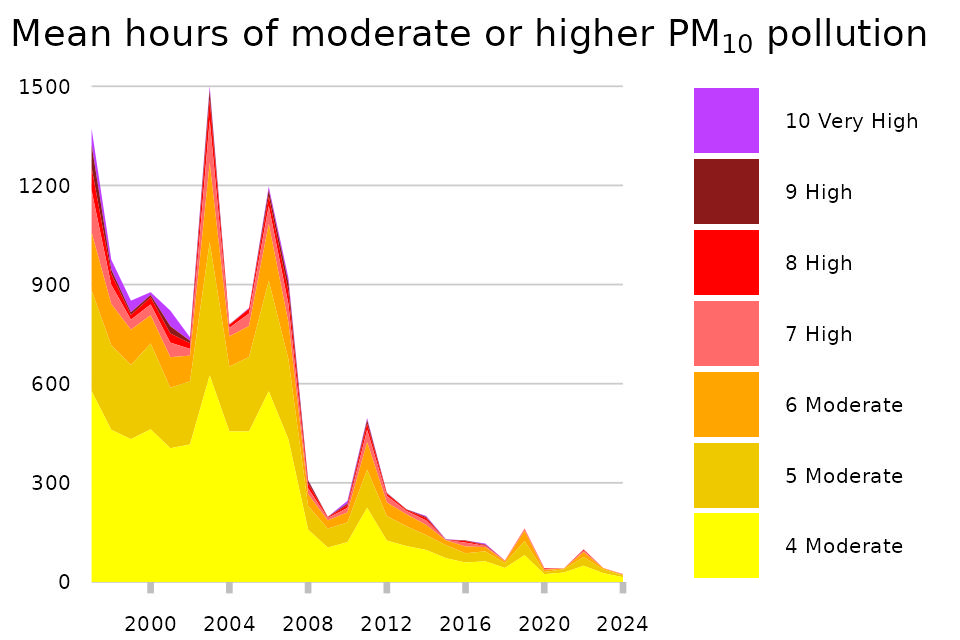

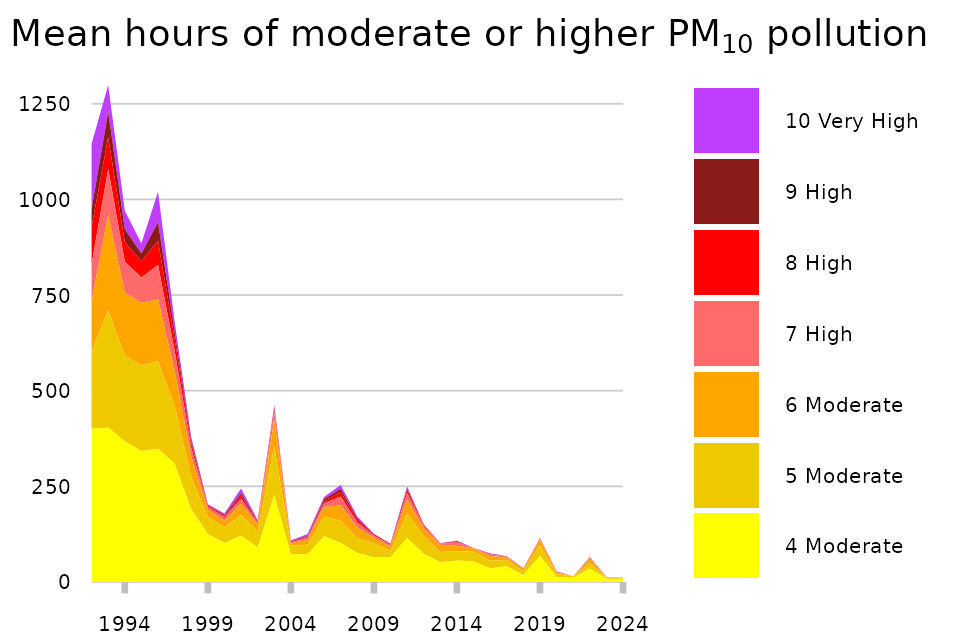

This metric measures the annual trend in the number of hours per monitoring site that concentrations are recorded at levels that may have impacts on human health. For example, ‘Moderate’ air pollution (which requires action by citizens who are vulnerable to the health impacts of air pollution) for PM10 is triggered when the latest 24-hour running mean concentration is greater than 50 µg/m3. The coloured categories relate to the categories of the Daily Air Quality Index (see Daily Air Quality Index Table in the statistical tables that accompany this release).

Figure 7: Annual mean hours when PM10 pollution was ‘Moderate’ or higher, for roadside sites, 1997 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

Figure 8: Annual mean hours per site when PM10 pollution was ‘Moderate’ or higher, for urban background sites, 1992 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

Roadside and urban background monitoring sites have recorded fewer hours of ‘Moderate’ or higher PM10 air pollution in the long term. At roadside and urban background sites the long-term trend has been a decline in the number of hours for which the mean PM10 concentration over the previous 24 hours exceeded 50 µg/m3.

At the roadside the mean number of hours where PM10 concentrations exceeded this ‘Moderate’ threshold for a monitoring site showed a decrease of 98 per cent between 1997 and 2024 to 24 hours; they decreased by an average of 50 hours per year over this period.

At urban background sites the mean number of hours where PM10 concentrations exceeded the ‘Moderate’ threshold for a monitoring site showed a decrease of 99 per cent between 1992 and 2024 to 11 hours; they decreased by an average of 35 hours per year over this period.

The downward trend in the time series has been interrupted in several years; most notably in 2003. In March and April 2003, meteorological analysis showed that concentrations at many monitoring sites were elevated due to primary emissions from Northern or Central Europe along with secondary particles caused by chemical reactions in the atmosphere. When cleaner Atlantic airflows became dominant in April 2003, pollution levels dropped considerably - see Air Pollution in the UK, 2003.

More recently, the downward trend was interrupted in 2019, but to a lesser degree. Meteorological analysis indicated that two UK-wide particulate pollution episodes occurred in February and April of 2019, and that these events primarily resulted from a combination of warm, sunny weather causing an increase in particulates from local and transboundary sources. In addition, light easterly winds transported a substantial amount of particulate matter from Europe. It is probable that these events contributed to the relatively high number of hours of PM10 pollution observed in 2019 - see Air Pollution in the UK, 2019.

During 2022 there was one significant widespread particulate pollution episode recorded. The episode occurred in spring and coincided with low wind speeds and air masses transported over Europe. Localised pollution events also occurred throughout the year – see Air Pollution in the UK, 2022.

For PM2.5, ‘Moderate’ air pollution (which requires action by citizens who are vulnerable to the health impacts of air pollution) is triggered when the latest 24-hour running mean concentration is greater than 35 µg/m3. The coloured categories relate to the categories of the Daily Air Quality Index (see Daily Air Quality Index Table in the statistical tables that accompany this release).

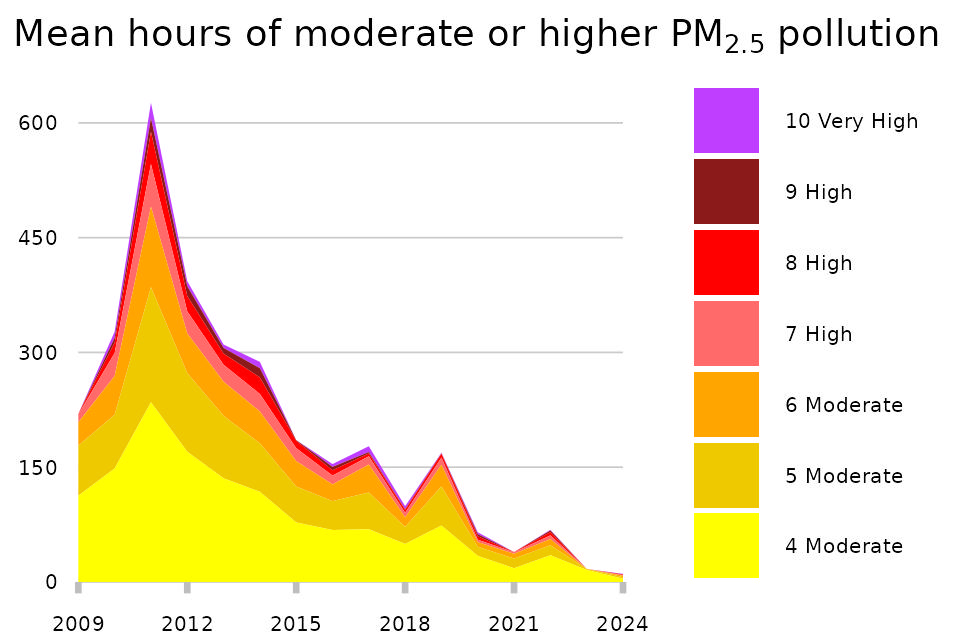

Figure 9: Annual mean hours when PM2.5 pollution was ‘Moderate’ or higher for roadside sites, 2009 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

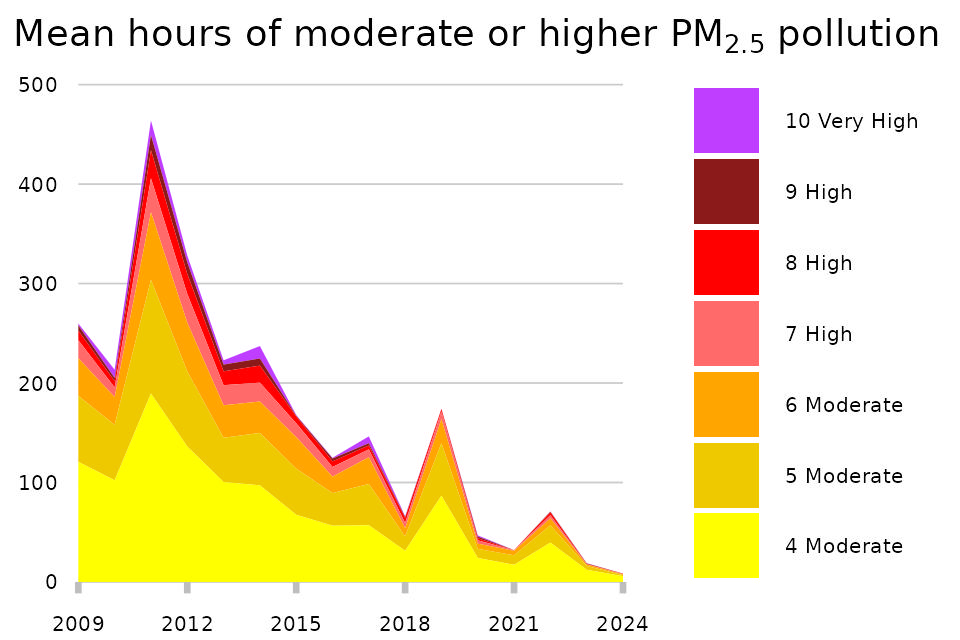

Figure 10: Annual mean hours when PM2.5 pollution was ‘Moderate’ or higher for urban background sites, 2009 to 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

Overall, roadside and urban background monitoring sites have recorded a decreasing trend in hours of ‘Moderate’ or higher PM2.5 air pollution since 2011. At roadside and urban background sites there has been a downward trend in the number of hours for which the mean PM2.5 concentration over the previous 24 hours exceeded 35 µg/m3 since 2011.

At the roadside the mean number of hours where PM2.5 concentrations exceeded this ‘Moderate’ threshold for a monitoring site showed a decrease of 98 per cent from the peak in 2011 to 11 hours per site in 2024.

At urban background sites the mean number of hours where PM2.5 concentrations exceeded the ‘Moderate’ threshold for a monitoring site showed a decrease of 98 per cent from the peak in 2011 to 8 hours per site in 2024.

Particulate pollution was particularly high in March and April 2011 due to a combination of secondary pollution being formed over mainland Europe and wind conditions carrying this pollution to the UK. A period of low wind conditions followed which allowed emissions from UK sources to build up in the atmosphere, leading to unusually high concentrations of particulate matter, see Air Pollution in the UK, 2011. Similar events occurred in February and April of 2019, resulting in a relatively high number of hours of PM2.5 pollution in that year - see Air Pollution in the UK, 2019. During 2022 there was one significant widespread particulate pollution episode recorded. The episode occurred in spring and coincided with low wind speeds and air masses transported over Europe – see Air Pollution in the UK, 2022.

5. Temporal variations in concentrations of PM2.5 in the UK, 2024

5.1 Monthly variations

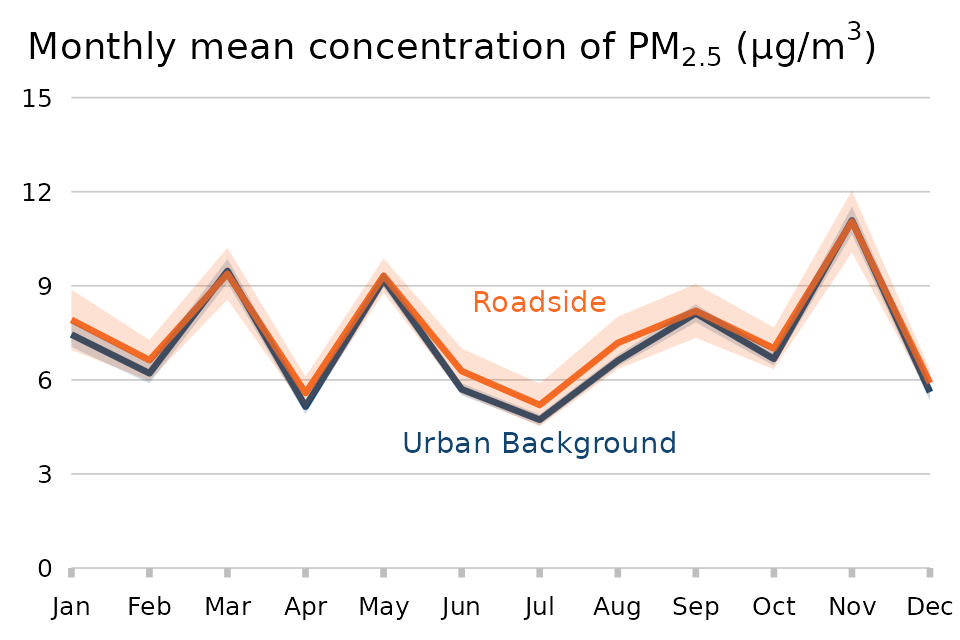

The PM2.5 index shows the monthly mean, averaged over all included sites that had monthly data capture greater than or equal to 75 per cent in a given year. The shaded areas represent the 95 per cent confidence interval for the monthly mean concentration for roadside sites and urban background sites.

Figure 11: Monthly mean PM2.5 concentration at roadside and urban background sites, 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

In 2024 PM2.5 concentrations were highest in November (11.0 µg/m3 for roadside sites and 11.1 µg/m3 for urban background sites).

Residential combustion of wood and coal in stoves and open fires is a large contributor to emissions of particulate matter both in the UK and across Europe, and is a contributing factor towards elevated concentrations towards the end of autumn and in winter months. Emissions from this source are typically located closer to urban background sites than roadside sides, which may explain the slight convergence between concentrations recorded at urban background and roadside sites throughout the winter months.

Concentrations of PM2.5 fell in December 2024. The weather in December 2024 was particularly unsettled, with stormy weather across the UK – see Met Office report. This would likely have contributed towards the drop in PM2.5 concentrations in December, as windy conditions increases the dispersion of pollutants, and since rain washes pollutants out of the air.

Looking back to the beginning of the year, concentrations fell between January and February before rising again to reach a peak in March. A peak in early spring is typical for PM2.5 concentrations, as elevated concentrations of nitrates are transported from agricultural operations across continental Europe - see the AQEG report.

Concentrations were reduced in April, before rising again in May. Concentrations then fell in June and July. Concentrations of PM2.5 are usually lowest in summer months, likely due in part to reduced pollution, such as less people burning fuels for heating.

It should be noted that there are many diverse emission sources for particulate matter, and there may be other sources which contribute to this pattern. There can also be considerable contribution from sources originating outside of the UK. The level of transboundary derived particulates is determined by weather conditions and prevailing winds.

5.2 Hourly variations

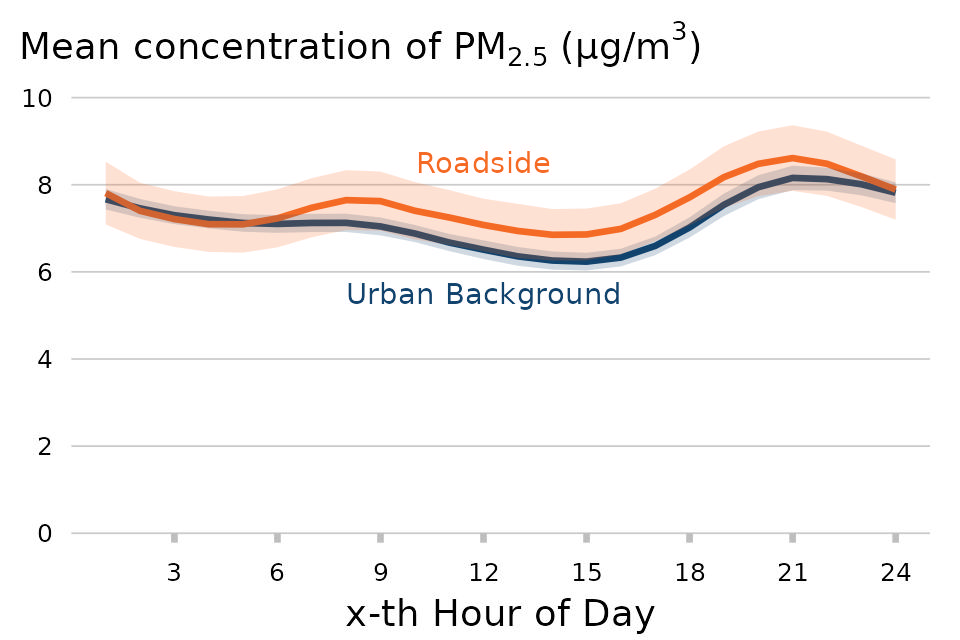

The PM2.5 index shows the hourly mean, averaged over all included sites that had data capture greater than or equal to 75 per cent for all instances of that hour in a given year. The shaded areas represent the 95 per cent confidence interval for the hourly mean concentration for roadside sites and urban background sites.

Figure 12: Hourly mean PM2.5 concentration at roadside and urban background sites, 2024

Download the data for this chart in CSV format

PM2.5 concentrations were greater in the evening compared to other times of the day; in 2024 the greatest mean concentrations were at 9pm for both roadside and urban background sites (8.6 µg/m3 and 8.2 µg/m3 respectively). This is thought to be the result of households burning wood, coal or other solid fuels in stoves or open fires for heating in the evenings, particularly in winter months. At urban background sites, concentrations of PM2.5 tend to slowly reduce to a minimum in the mid-afternoon before rising again. The average at roadside locations follows a similar pattern throughout the day, except there is also a smaller peak at 9am which is likely caused by morning rush hour road traffic. PM2.5 originating from road traffic also likely explains the slightly higher levels of PM2.5 concentrations during the day at roadside locations compared to the urban background locations.

6. Sections in this release

Background to concentrations of air pollutants

Concentrations of nitrogen dioxide

Days with ‘Moderate’ or higher air pollution (includes sulphur dioxide)