An introduction to the Prevent Duty in higher education (HE): notes for trainers

Updated 3 March 2023

Applies to England

1. Note to the trainer

These training notes are intended to support higher education (HE) providers delivering the ‘An introduction to the Prevent Duty in higher education (HE): PowerPoint presentation’. It can be adapted by the provider and delivered to large numbers of staff.

These training materials are not intended to be a replacement of the Home Office’s Prevent awareness training.

1.1 Top tips for delivering this training

- Apply the same principles you would to all training activities – know your audience, identify their training needs, plan your approach carefully, develop a communication plan so that staff understand the purpose of the training, and why they should engage with it.

- Be open and transparent - recognise that staff will have preconceptions and concerns about Prevent, draw these out and address them at the start of face-to-face sessions. This can work well as an icebreaker.

- Involve staff and students in discussions about training, working in partnership with staff and student representatives. Use both existing mechanisms (committees, staff-student liaison groups, departmental meetings and so on) and any Prevent-specific mechanisms in place.

- Think how you can use the expertise of other specialists in Prevent training – data protection and FOI officers, for example. Bringing in equality and diversity officers can help staff understand how Prevent interacts with equality and diversity legislation.

2. Title slide

This is an introductory module that provides essential information on Prevent, about which all staff working in HE should have an awareness. This module is also available as an e-learning module.

3. Who is the module for?

This module is intended for staff and other relevant personnel who need to understand the nature of the Prevent statutory duty as applicable to higher education.

This module provides an introduction to Prevent and contains essential information about the statutory Prevent duty.

Image of slide 1: who is this module for?

4. Outline

This session identifies the scope of the Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015 (as amended) and the Prevent duty requirements for RHEPs. The session will also outline the process of radicalisation, the Prevent referral process, and support available through Channel.

Image of slide 2: what will the session cover?

5. Counter-Terrorism and Security Act

This slide covers some brief details on the passage of the Act – drawing attention to section 26 which made it statutory for a number of specified authorities to engage with the Prevent Duty.

The duty is to have due regard to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism. You should at this point explain the meaning of ‘due regard’ - as used in the Act, this means that authorities should “place an appropriate weight on the need to prevent people being drawn into terrorism when they consider all the other factors relevant to how they carry out their usual functions”.

This recognises the need for a proportionate response to how individual organisations implement the Duty – “appropriate weight” will mean different things for different types of organisations.

The government has published general guidance for all authorities and separate guidance for each specified authority – there is separate guidance for HE institutions in Scotland.

Image of slide 3: counter-terrorism and security act

Is all this new?

The statutory nature of the duty is, but Prevent isn’t. Prevent was introduced by the Labour government following the 7/7 London attacks and the perceived increased risk of reprisal attacks on Islamic targets, individuals and mosques. The strategy was revised in 2011 by the Coalition government and then again in 2018 by the Conservative government when the Contest Strategy was refreshed. It is important to note that many institutions were already engaged with Prevent and this is noted in the HE-specific guidance, which also refers to the good practice that already exists.

6. Prevent strategy 2011

It is these 3 specific objectives which define the nature of the duty. If we are to understand the duty and our responsibilities relating to it, it is useful to explore what is meant by the terms used in the strategy – and in particular, “terrorism”, “radical/radicalisation” and “extremism”.

Image of slide 4: Prevent strategy - 3 specific objectives

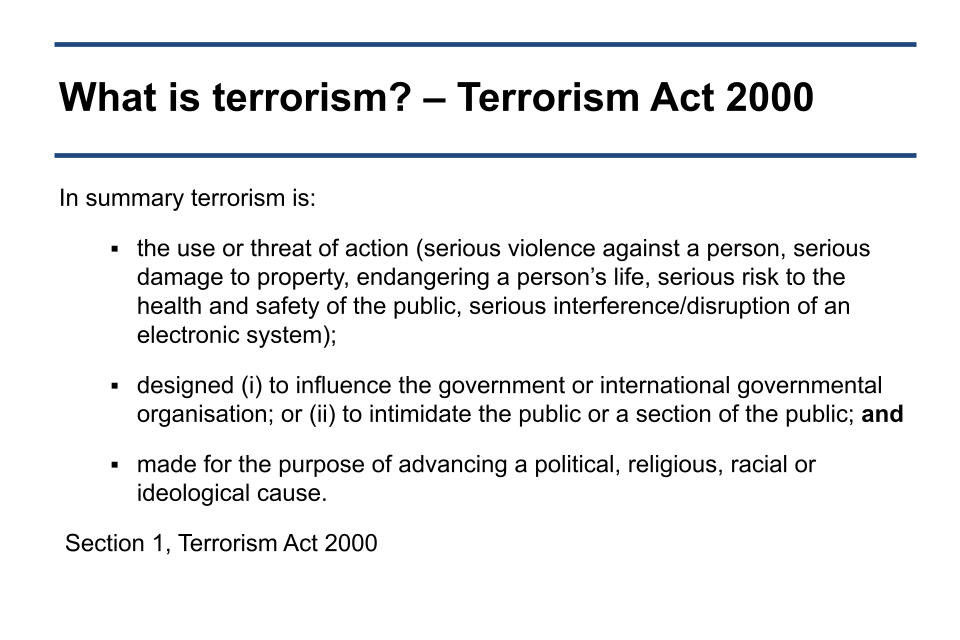

7. What is terrorism?

This is the definition from the Terrorism Act (2000). Involvement in illegal terrorist-related activity is a serious crime. Where there is a suspicion on the part of a specified authority that an individual may be involved in such activities, the suspicion must be reported to the police. Encouragement of terrorism and inviting support for a proscribed terrorist organisation are both criminal offences. RHEBs should not provide a platform for these offences to be committed. There is nothing contentious or controversial here.

Image of slide 5: What is terrorism? Terrorism Act 2000

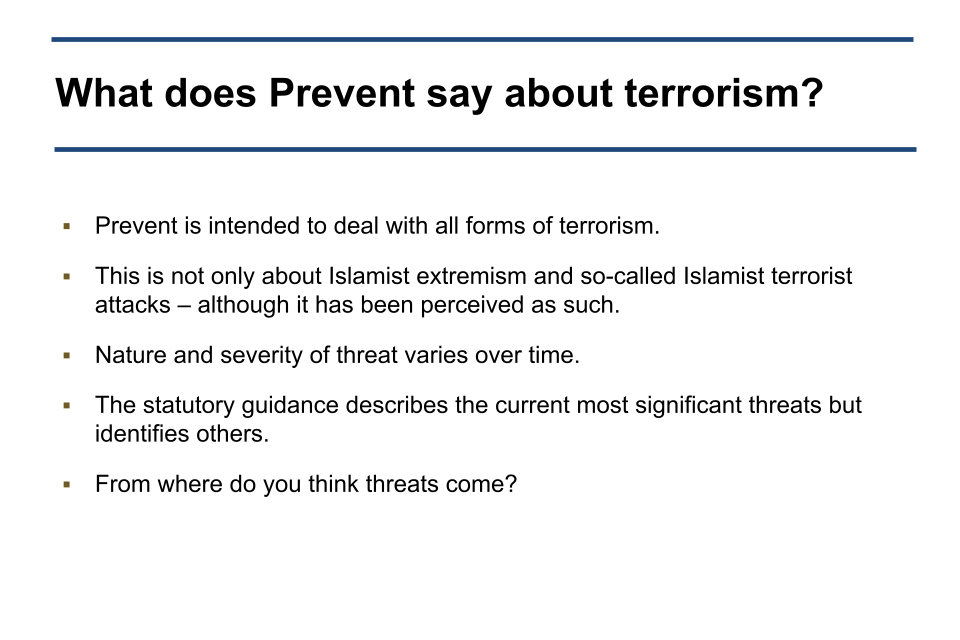

8. What does Prevent say about terrorism

One of the controversies surrounding Prevent is a perception that it is only about Islamist extremism and that Prevent itself encourages Islamophobia and alienates Muslim communities. Those responsible for implementing the Duty need to be sensitive to these perceptions and feelings.

The Prevent strategy stresses that it deals with all forms of terrorism but the nature and severity of threat varies over time.

Ask your audience where they think threats originate – list them on a flip chart if you wish.

Image of slide 6: What does Prevent say about terrorism?

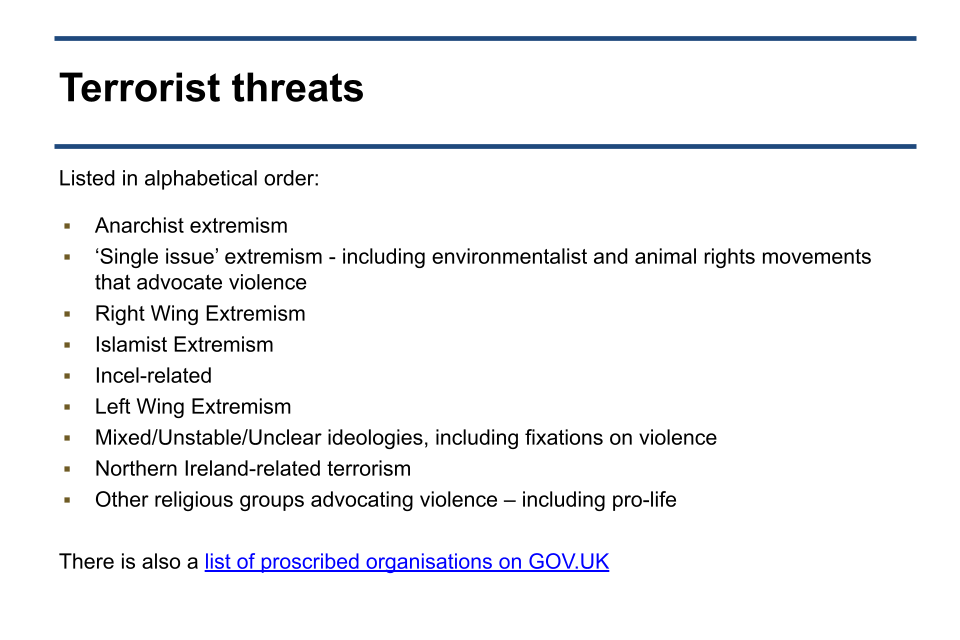

9. Terrorist threats

The Prevent Duty provides a framework for specified authorities to respond to the changing nature of threat in the UK. According to the government’s current Counter-Terrorism strategy, the main threat to the UK comes from Daesh (ISIS) or Al Qa’ida inspired terrorism, although right-wing terrorism is a growing threat (Contest 3.0, 2018).

Some groups and organisations are proscribed, which means that they are banned under counter-terrorism measures introduced under the Terrorism Act 2000 (for example, Da’esh and National Action).

Different parts of the country face different threats from terrorist groups and organisations. However, geographical proximity is less relevant when groups and individuals can engage others online.

The proportion of referrals from different categories of terrorism and extremism changes over time, as does the level of risk posed by each category.

Image of slide 7: Terrorist threats

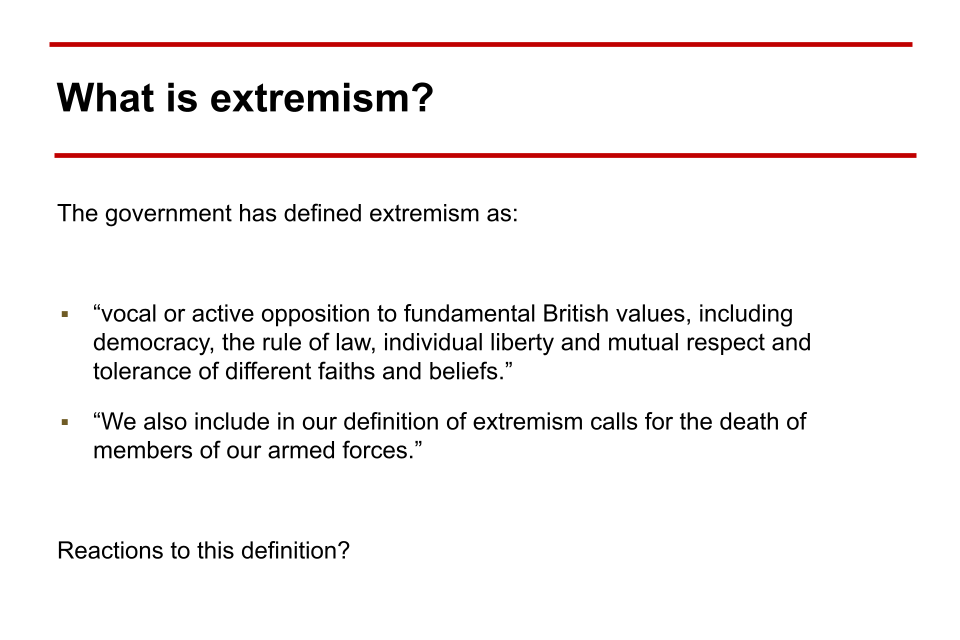

10. What is ‘extremism’?

Here is the government definition – ask for reactions. It is highly likely that participants will question whether the values are “fundamentally British” – these are values to which many societies subscribe. These are values which are consistent with the mission, vision and value statements of many providers.

The definition has caused concern that its application will stifle legitimate debate about numerous controversial issues. The NUS (National Union of Students) and UCU (Universities and Colleges Union) have based their opposition to Prevent on these grounds.

This is not the intention of the Duty. Higher education providers play an important role as a safe place to explore and challenge views and opinions, in a climate of free discussion and debate.

Image of slide 8 : What is extremism?

11. Holding and expressing views others might find offensive

It is not extremist to hold any extreme views provided they are not expressed in a way that harasses others or incites violence or furthered by statements, deeds or actions which result in harassment, intimidation or threats of violence against individuals or society itself – and this is the fundamental point.

This highlights the challenge in implementing the duty effectively – providers face criticism for allowing certain events to proceed where extremist views may be represented and at the same time for cancelling events and therefore limiting freedom of expression. Legislation is clear that lawful events should go ahead.

It is important that providers have appropriate policies and processes in place for assessing and managing the risks around external events. Providing that events have suitable mitigations in place (if required) to ensure freedom of speech can take place in a safe and managed way, they should be allowed to go ahead.

Please note that paragraph 11 of the Prevent HE guidance, which talks about balancing and mitigating risks, was subject to a judicial review decision in March 2019 - Butt v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2019] EWCA Civ. 256.

The statements in paragraph 11 that ‘an event must not be allowed to proceed if the RHEB is not entirely convinced that the risk, however small, of people being drawn into terrorism cannot be fully mitigated’, was considered unlawful by the Court of Appeal. This is because the statements are unconditional and do not permit RHEB’s to balance fairly their freedom of speech and prevent duties. The decision may be appealed by the government, but for now being unable to fully mitigate risks should not mean an event is automatically cancelled.

Image of slide 9: Holding and expressing views others might find offensive

12. The process of radicalisation

This builds on the previous slide and includes a quotation from the Prevent strategy, which suggests that it is likely that others (families, friends, work colleagues) will notice the signs of radicalisation, although this is not universally the case. The time it takes for someone to become radicalised varies between individuals – there is not a set period.

Image of slide 10: The process of 'radicalisation'

13. Preventing radicalisation

This is an important consideration and lies at the core of the Prevent strategy and duty – that people drawn into radicalisation, and therefore at risk of recruitment into terrorist activities can be identified and supported. It is on this premise that Prevent is regarded as essentially a safeguarding matter.

Image of slide 11: Preventing radicalisation

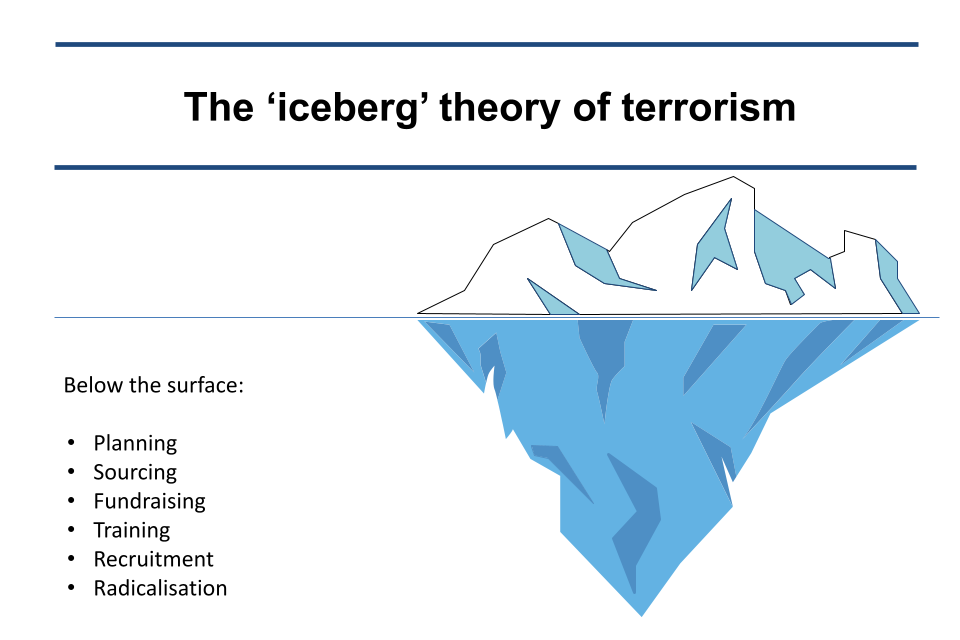

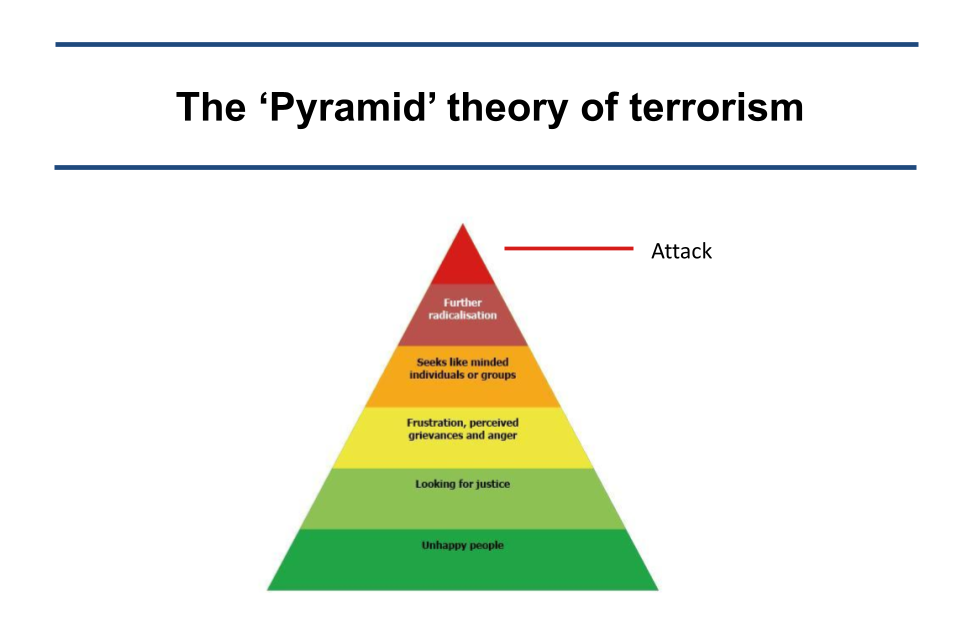

14. The ‘pyramid’ and ‘iceberg’ theory of terrorism

This is a popular and widely held theory – that terrorism or an act of terrorism is only the tip of an iceberg. An iceberg has only 10% of its total mass above the water and the analogy is that underneath (or, on a timeline, before) the actual terrorist attack there is a great deal going on.

This is likely to include a structure to support the furtherance of the objectives of the group or organisation and, in the case of individuals who may go on to commit terrorist acts, certain patterns of behaviour. The activities below the surface will include the exposure of vulnerable individuals to influences that draw them into terrorism.

Image of slide 13: The 'iceberg' theory of terrorism

The pyramid model that follows the image of the iceberg suggests that people with a complaint or grievance may move through a process, first of all seeking justice and, in the event that this fails, becoming increasingly angry and seeking out other like-minded people who have experienced the same injustice. Association with such individuals could expose them to further radicalisation, and in the worst scenario, complete the passage to becoming ‘a terrorist’. It is based on the work of McCauley and Moskalenko (read their article Mechanisms of Political Radicalisation: Pathways towards terrorism, in Terrorism and Political Violence, 2008). It is, of course, within the 90% of the iceberg below the surface that Prevent works.

Image of slide 12: The 'Pyramid' theory of terrorism

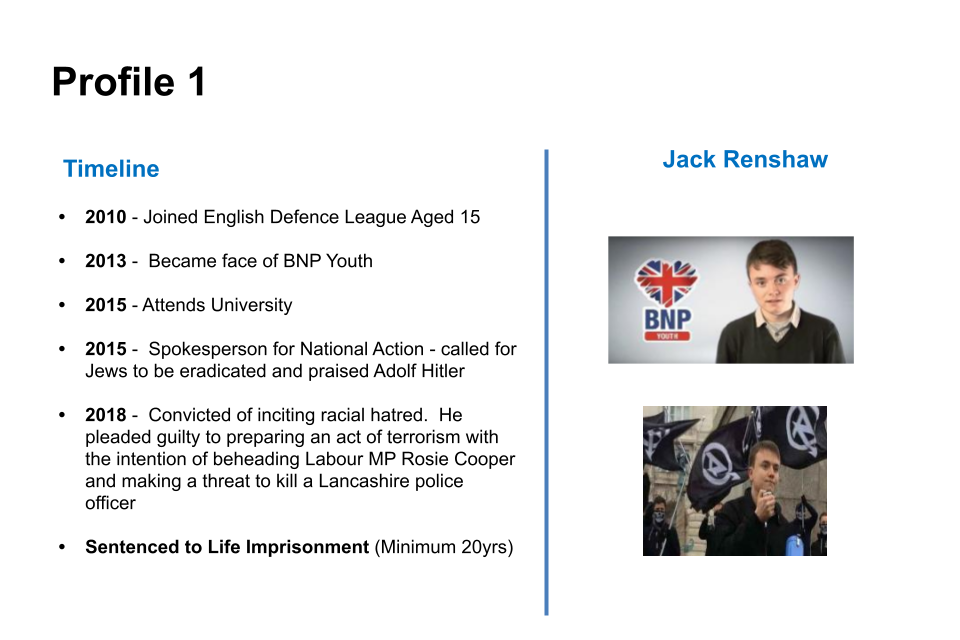

15. Jack Renshaw and Roshonara Choudhry

Jack Renshaw got involved with the English Defence League (EDL) aged 15. It was through the EDL that he became involved with the Justice for Charlene Downes cause and met British National Party (BNP) members and their leader, Nick Griffin. Jack began a course at university studying politics and economics in September 2013. It was at this time he became the face of the BNP Youth.

Anti-Semitic Facebook posts encouraging violence against Jewish people were reported by a student recruitment officer to their line manager. A concern was raised and formally reported to senior management. An open source and social media check was carried out on Renshaw, which resulted in a student case hearing being scheduled. Renshaw withdrew from his course and went on to speak at far-right events, calling for Jews to be eradicated.

On 12 June 2018, Renshaw pleaded guilty to preparing an act of terrorism with the intention of killing the Labour MP Rosie Cooper and to making a threat to kill a police officer. He had obtained a knife and spoken of his plans to carry out attacks.

Image of slide 14: Profile 1 Jen Renshaw

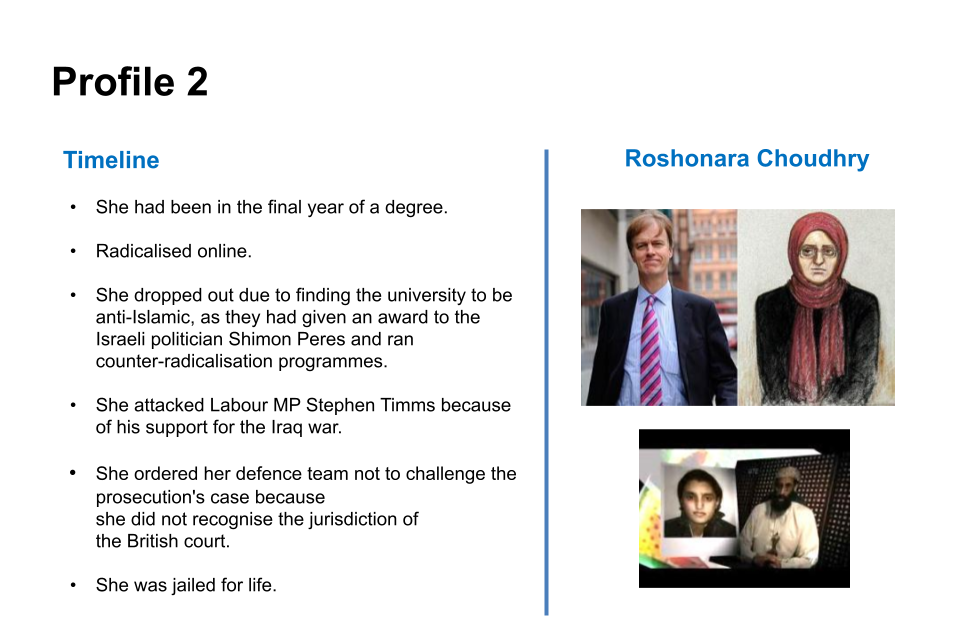

In May 2010, Roshonara Choudhry attempted to murder ex-Labour MP Stephen Timms because he had voted for the Iraq war. She dropped out of university in her third year having been a high-achieving student. She was radicalised online, and her family were as surprised as anyone by her actions. What we do know is that she retreated to her room for long periods because of domestic violence within the home.

Image of slide 15: Profile 2 Roshonara Choudry

This raises the question: is it possible to spot signs of radicalisation and vulnerability to being drawn into terrorism? In addition to the cases above, 2 of the 7/7 bombers were considered model students at the college they attended. Let’s look at this further – it is not always the case that signs of radicalisation will be evident – Prevent is about doing something if they are present

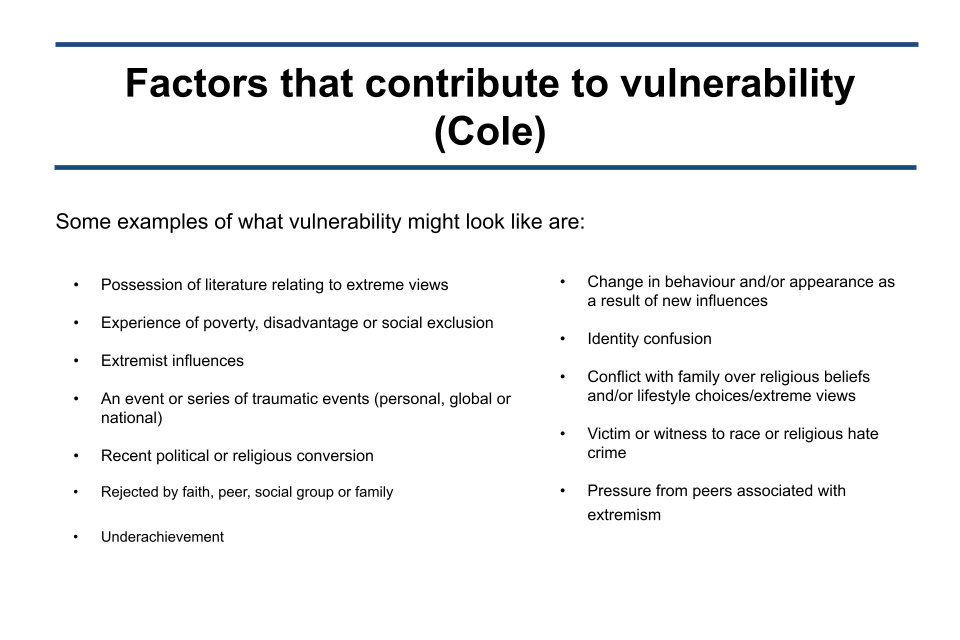

16. Factors that may contribute to vulnerability

The diagram identifies some of the factors that may contribute to vulnerability. Some of them are self-explanatory, but some of them (identity confusion and rejection by peer group) could, of course, be indications of other issues of concern. This is why it is important to align the Prevent duty with broader student safeguarding and welfare procedures for staff and students, meaning that any individual who becomes a cause for concern can be referred to agencies within the RHEB that can provide advice and identify the most appropriate support.

In the case of identifying someone who is vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism, this is relatively straightforward if there are overt signs, such as displaying certain emblems or expressing vocal support for known terrorist acts or proponents of terrorism. However, it is often the case that individuals will have been radicalised through influences outside the institution and may not exhibit behaviours that cause a concern.

What RHEBs must do, though, is to be aware of the risks, ask staff to be aware of any obvious signs, take every step to minimise risks within areas over which they have control and ensure that, where there are causes for concern, their procedures allow for appropriate interventions.

Image of slide 16: Factors that contribute to vulnerability (Cole)

17. The HE-specific Duty guidance

The Duty’s scope is wide – around 300 to 350 HE providers in England alone are covered by it, including both publicly funded and private providers. This figure excludes FE colleges, which fall under Ofsted’s monitoring regime. Emphasise that the governing body or proprietor is accountable for the effective implementation of the Prevent Duty.

Image of slide 17: HE-specific duty and guidance

18. Expectations

Emphasise that it isn’t only having policies in place; they will need to be actively applied and reviewed appropriately with clear evidence in place to demonstrate this. The other key point here is that risk assessments on the Prevent Duty must be undertaken and kept up to date – the level of risk will vary between providers, but the guidance emphasises that no provider is risk-free.

The risk assessment must assess where and how students at a particular RHEB may be at risk of being drawn into terrorism. Risk assessments will need to use information from external sources – in particular, from DfE regional FE or HE Prevent co-ordinators, local authorities, police and so on. Assessments will also include the physical management of the university estate, including policies and procedures for events by students, staff and third parties who use the premises.

Effective risk management will help a provider to manage the implementation of and compliance with the Duty. It will also help to ensure that the resulting action plan to mitigate risks is proportionate – a very important point.

Image of slide 18: Expectations

19. Prevent is not about…

Concerns about the Duty, as represented here, should be discussed.

Providers are expected to consult students on the Duty, and it is crucial that the types of issues that are central to the NUS’s opposition to Prevent, for example, are considered.

This is also the case with opposition by staff and their representative bodies. The best approach is to ensure that students and staff are well-informed on Prevent and their provider’s approach to implementing the Duty is transparent – including ‘busting any common myths’ - to avoid the perception that Prevent is somehow ‘secretive’ or a ‘snoopers’ charter’.

Image of slide 19: What Prevent is not about

20. Prevent Duty expectations

These, and the following 3 slides, go through what it is RHEBs must do to meet the Prevent Duty.

Risk assessment

Providers must undertake a risk assessment of where and how their students might be at risk of being drawn into terrorism. In addition, a risk assessment of their institutional policies regarding campus and student welfare. Assessments must also include the physical management of the university estate, including policies and procedures for events by students, staff and third parties who use the premises.

Partnerships

This would include active engagement from senior management of the RHEB with other partners including DfE regional FE or HE Prevent co-ordinators, local authorities, police and so on.

Action plans

To develop a Prevent action plan setting out the actions they will take to mitigate any risks.

Staff training

For appropriate members of staff to have an understanding of the factors that make people support terrorist ideologies or engage in terrorist-related activity. Such staff should have sufficient training to be able to recognise vulnerability to being drawn into terrorism and be aware of what action to take in response. This will include an understanding of where to get additional advice and support and when to make a a Prevent referral.

Welfare and pastoral care

To have clear and widely available policies for the use of prayer rooms and other faith-related facilities. These policies should outline arrangements for managing prayer and faith facilities (for example an oversight committee) and for dealing with any issues arising from the use of the facilities.

IT policies

Appropriate policies and procedures on IT and use of computers including due consideration of filtering.

Student unions and societies

To have clear policies setting out the activities that are or are not acceptable to take place on campus and any online activity directly related to the university. The policies should set out what is expected from the student unions and societies in relation to Prevent including making clear the need to challenge extremist ideas which risk drawing people into terrorism. We would expect student unions and societies to work closely with their institution and co-operate with the RHEB’s’ policies.

Image of slide 20: Prevent Duty expectations

Image of slide 21: Prevent Duty expectations (continued)

21. External speakers and events

The requirement to have in place policies on external speakers and events is not new – certainly in the case of publicly funded providers, there has been a longstanding requirement for them to do so in the context of the Education Acts 1986 and 1988.

The Prevent Duty guidance extends this requirement to providers not mentioned in these Acts – predominantly the ‘small and specialist providers’. We should note that there is no precise definition of ‘external speakers’ but there is an expectation that the policies should apply to all staff, students and visitors and clearly set out what is required for any event to proceed.

Policies should also cover online events where no speaker is actually present and off-campus events that are branded or affiliated to the university or Students’ Union, as well as the commercial use of premises by external groups.

Much of the policies will relate to events organised by students’ unions and student societies but there will need to be a procedure relating to speakers invited to contribute to teaching but relatively light touch.

The OfS would not necessarily expect curriculum-related speakers to be treated in the same way as non-curricular/unknown external speakers as there should already be mechanisms for managing guest lecturers with defined presentation content. This will usually be a matter for the academic department concerned but it is important that this is not overlooked.

Where appropriate, security staff may need to be consulted about events and measures put in place to ensure physical security.

Image of slide 22: External speakers and events

22. Policies on pastoral care

This is central to the Duty. Universities and colleges take seriously their duty of care to their students and to their staff. They have in place a range of support services, especially to support students identified as vulnerable. The Prevent Duty requires that such arrangements include support for students vulnerable to being drawn into terrorism. Cause for concern procedures should acknowledge this.

The trainer may wish to ascertain at this point how many delegates are aware of their own providers cause for concern’ policy or process and set this out in detail, including who is responsible for assessing whether a Prevent referral is required.

There is also a requirement that providers have in place arrangements to manage and oversee the use of prayer facilities, ensuring that their use is both appropriate and inclusive.

Image of slide 23: Policies on pastoral care

23. Case studies

Five scenarios are presented. Ask participants to say what they might do in each case. There is no need for lengthy discussion – gather immediate responses and say that there is no definitive answer.

-

What would you do?

There is nothing wrong with someone to converting to any religion, and lots of people rely on the internet for information. Most people here will probably say they would do nothing. In cases where an institution has a Muslim chaplain or a multi-faith chaplaincy, people might suggest the student is made aware of the services available there.

-

What would you do?

The most likely suggestion here is that the lecturer would ask to see the student and discuss the incident with him/her. S/he might also talk to colleagues to see if there were any other concerns about the student’s behaviour. -

What would you do?

Likely responses will include the suggestion that the person responsible for the prayer facility should see the student and remind him/her that the facility is for the use of all students and that s/he should respect this. -

What would you do?

People will probably note that there was no actual disturbance and the student is entitled to express such views. -

What would you do?

Participants are likely to suggest that context is important here and it would depend on what was said. The counsellor is best placed to decide what action to take, depending on his/her assessment of the behaviour and mood of the student. S/he will probably want to take advice from an appropriate colleague.

All these incidents (as indicated on slide 31) relate to a single individual who was subsequently convicted of preparing terrorist acts involving a shopping centre in Bristol. He was a student at the City of Bristol College at the time of his arrest. The incidents and any concerns associated with them were not reported and therefore, no connection between them was made.

Image of slide 30: It's a real case

The lesson therefore, is that institutions should make staff aware of the need to report such incidents, or at least, seek advice – ideally from a single point of contact within the institution as identified in the cause for concern procedures. Prevent action plans will need to cover this. It is also important that decisions about referring externally are also well-coordinated.

24. A procedure for advice, support, intervention and referral

This slide reinforces the points arising out of the case study.

Image of slide 35: A procedure for advice, support, intervention and referral

25. Making referrals to Prevent

Any initial concerns should be shared internally within the organisation utilising the existing safeguarding procedures. The Prevent Lead or Designated Safeguarding Lead can then make any necessary enquiries and if appropriate share the concern with external partners. During this information gathering and sharing part of the process, it is not necessary to obtain the individual’s consent (as it isn’t with other safeguarding issues).

If a formal referral is made to Prevent, it is good practice to do so with the individual’s acknowledgment or agreement. Referrals to Prevent should not be made directly by any member of staff or individual within a provider other than the Prevent Lead or Designated Safeguarding Lead.

In some circumstances, referrals can be made without the consent of the individual and participation in any support offered is voluntary – this is important in the context of data protection law and duties of confidentiality. Referrals without an individual’s consent will need to be justified within relevant data protection legislation – this is covered in the leadership challenge module. However, Prevent leads may seek advice from external contacts, including HE or FE regional Prevent co-ordinators to discuss anonymously cases they may be considering for referral.

An important point to remember is that referrals to Prevent will not show up on DBS checks.

Here, the trainer should set out the process for making referrals within their setting.

Image of slide 33: Making referrals to Prevent

26. Channel

Channel is an important part of Prevent. It’s aim is early intervention to provide support to vulnerable individuals

Image of slide 31: What is Channel?

27. The Channel process

Channel is the responsibility of the local authority. All parties subject to the Prevent duty must cooperate with the process. Where appropriate, the RHEB will be represented on a Channel panel.

Image of slide 32: The Channel process

28. Monitoring for compliance

It is the funding councils in England and Wales role to monitor the implementation of the Duty in HE. In Scotland, different arrangements apply. In all administrations, though, responsibility for compliance rests with the governing body or proprietor.

For RHEBs in England the monitoring body is the OfS. In Wales, the monitoring body is Higher Education Funding Council Wales (HEFCW). In cases where there are particular circumstances or risk factors at an individual provider, a Prevent review involving face-to-face meetings may take place.

OfS will be required to report to the government on the sector’s compliance. The framework they have devised, including the mandatory submission of certain data (numbers trained, number of referrals to Prevent, number of events and speakers referred to the highest levels of approval required by the providers procedures) is intended to provide appropriate levels of assurance to DfE and the Home Office on how the sector is engaging with the duty. RHEBs must also report any serious incidents to OfS.

It is for providers to decide what constitutes a serious Prevent-related incident, but we would expect this to include any incidents which have led to broader Prevent policies being fundamentally reviewed or revised, or have the potential to cause reputational harm (such as media coverage which raises substantive concerns) or actual harm (such as physical injury) to staff or students. Governing bodies will need to be made aware of any serious Prevent-related incidents reported to OfS and to be assured appropriate steps are being taken to address any concerns.

As the Prevent duty is a legal requirement, it is expected that governing bodies and proprietors will take this responsibility seriously – non-compliance is not an option.

Further information is available on the monitoring framework in England and HEFCW’s monitoring framework. RHEBs in Scotland should contact local multi-agency CONTEST groups and the national Prevent and CONTEST governance structures for support. Users will want to guide participants to relevant local policies and procedures on Prevent.

Image of slide 34: Monitoring for compliance