Autumn Statement 2016

Published 23 November 2016

1. Executive summary

Since 2010, the government has made huge progress in turning the economy around following the Great Recession. The employment rate is at a record high and the deficit has fallen by almost two thirds. But more needs to be done. The deficit remains too high and productivity too low. In addition, the government wants to see more people sharing in the UK’s prosperity and ensure that the tax system is one where everyone plays by the same rules.

In the near term, the UK’s economic outlook has become more uncertain. The British people’s decision to leave the EU presents new opportunities, but also new challenges. The Autumn Statement sets out policies which support the economy during this transition. Alongside the forthcoming Industrial Strategy it prioritises investment to improve productivity and ultimately living standards. It provides certainty for business to secure investment and create jobs; and reprioritises spending to build an economy that works for everyone.

1.1 UK economy

The UK economy showed considerable momentum in the run up to the EU referendum, and has shown significant resilience since. The UK is forecast to be the fastest growing country in the G7 in 2016 and economic activity grew 2.3% in the year to Q3 2016. The employment rate is at a record high of 74.5%, and between 2009-10 and 2015-16 the deficit was reduced by almost two-thirds from 10.1% to 4.0% of GDP.

The UK is likely to face a period of uncertainty, followed by adjustment. Reflecting this, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts that GDP growth will slow to 1.4% in 2017, and then recover to 1.7% in 2018, 2.1% in both 2019 and 2020, and 2.0% in 2021. The OBR expects lower business investment and household spending to weigh on GDP in the near term. Lower business investment is expected to exacerbate the long-standing weakness in UK productivity. The OBR highlights that there is a higher than usual degree of uncertainty in these forecasts.

1.2 Public finances and fiscal policy

The OBR’s forecast for the public finances shows a deterioration since Budget 2016, due to disappointing tax revenues over the first half of this year, a weaker economic outlook weighing on receipts from income taxes, and higher spending by local authorities, public corporations, and on welfare benefits. Compared with the OBR’s Budget 2016 forecast, borrowing is higher in every year of the forecast and £32 billion higher in 2020-21. Debt peaks at over 90% of GDP in 2017-18 due to a combination of higher borrowing, lower asset sales, and the impact of the Bank of England’s monetary policy operations.

The Autumn Statement sets out how the government will return the public finances to health, while providing flexibility to support the economy in the near term and addressing long-term economic weaknesses through increased investment. The government will return the public finances to balance as soon as possible in the next Parliament, with an interim objective of reducing the structural deficit to less than 2% of GDP, and for debt as a percentage of GDP to be falling by the end of this Parliament.

To achieve this, the government is committed to maintaining fiscal discipline. At the Autumn Statement the government chooses to borrow only to invest in highly-targeted infrastructure and innovation which will boost productivity. All other new commitments have been funded.

1.3 Productivity

The Autumn Statement, and the government’s forthcoming Industrial Strategy, will focus on raising productivity to raise living standards for people across the UK.

A new National Productivity Investment Fund will add £23 billion in high-value investment from 2017-18 to 2021-22. The government will target this spending at areas that are critical for productivity: housing; research and development (R&D); and economic infrastructure. The NPIF will take total spending in these areas to £170 billion over the period from 2017-18 to 2021-22, reaching 1.7% of GDP in 2021-22. The new spending includes:

-

£7.2 billion to support the construction of new homes, including spending by Housing Associations

-

£4.7 billion to enhance the UK’s position as a world leader in science and innovation

-

£2.6 billion to tackle congestion and ensure the UK’s transport networks are fit for the future

-

£0.7 billion to support the market to roll out full-fibre connections and future 5G communications

The government will encourage private investment with £400 million from the British Business Bank to unlock £1 billion of new investment in innovative firms planning to scale up, and a doubling of capacity to support exporters through UK Export Finance.

In addition the government will review the tax environment for R&D to look at ways to build on the introduction of the ‘above the line’ R&D tax credit to make the UK an even more competitive place to do R&D.

The government will raise productivity across the UK. The government is publishing the Northern Powerhouse Strategy, allocating £1.8 billion funding for regions through the Local Growth Fund, continuing discussions with the West Midlands and London on future devolution deals, and continuing to pursue city deals in Scotland and Wales.

1.4 Tax

Providing certainty is central to the government’s aims for the tax system. The government’s intention is to move to a single fiscal event in the autumn each year to provide more stability for businesses and individuals. Despite pressure on the public finances:

-

the government recommits to raising the personal allowance to £12,500 and the higher rate threshold to £50,000 by the end of the Parliament. By 2020, the government will have delivered a decade of income tax cuts, reducing taxes so that working families can take home more of what they earn. From that point the personal allowance will rise in line with the Consumer Prices Index

-

the government recommits to the business tax road map which sets out plans for major business taxes to 2020 and beyond, including cutting the rate of corporation tax to 17% by 2020, the lowest in the G20, and reducing the burden of business rates by £6.7 billion over the next 5 years.

In order to reduce living costs, and support those who are just about managing to get by, the government will freeze fuel duty from April 2017 for the seventh successive year. This will save the average driver around £130 a year, compared to pre-2010 fuel duty escalator plans.

The government will also take action to promote fairness in the tax system, ensuring everyone plays by the same rules, and to secure a sustainable tax base:

-

to tackle tax avoidance, the government will strengthen sanctions and deterrents and will take further action on disguised remuneration tax avoidance schemes

-

to ensure multinational companies pay their fair share, following consultation, the government will go ahead with reforms to restrict the amount of profit that can be offset by historical losses or high interest charges

-

to fund commitments made in the Autumn Statement, Insurance Premium Tax will rise from 10% to 12% in June 2017

-

to promote fairness and broaden the tax base, the government will phase out the tax advantages of salary sacrifice arrangements

1.5 Public spending

Putting the public finances on a sustainable path is vital to securing a strong and stable economy. Departments will therefore continue to deliver overall spending plans set at the Spending Review 2015. The Efficiency Review announced at Budget 2016 will update in autumn 2017.

The government will deliver welfare savings already identified but has no plans to introduce further welfare savings measures in this Parliament beyond those already announced.

To help people progress in work, the government will reduce the taper rate that applies in Universal Credit from 65% to 63% so working families will keep more of every pound they earn.

In order to support savers, NS&I will offer a new market leading 3-year savings bond, open to those aged 16 and over, available for 12 months from spring 2017.

Table 1: Autumn Statement 2016 policy decisions (£ million) (1)

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total tax policy decisions | +25 | +375 | +640 | +720 | +565 | +555 |

| Total spending policy decisions | -310 | -3,930 | -6,335 | -8,680 | -7,490 | -9,270 |

| Total policy decisions | -285 | -3,555 | -5,695 | -7,960 | -6,925 | -8,715 |

| Total policy decisions excluding NPIF and inherited policy | -220 | +40 | +170 | -5 | +30 | +130 |

| (1) Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. |

2. Economy and public finances

2.1 Economy

Government action since 2010 has helped to ensure that the fundamentals of the economy are strong. The government has taken steps to improve growth prospects and reduce the deficit, putting the economy on a sound footing. In recent years, the UK economy has grown at a faster pace than other major advanced economies, which has supported strong gains in employment. As data released since the EU referendum have shown, the economy has been resilient. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew at a solid rate through the first three quarters of 2016, and employment and living standards have continued to rise.[footnote 1]

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) judges that there will now be a period of economic uncertainty as the UK negotiates its departure from the EU. Beyond that, the economy will need to adjust to new relationships with the EU and the rest of the world. Consistent with most external studies, the OBR expects that this period of uncertainty and adjustment will lead to lower business investment. This has driven its assessment that the outlook for productivity growth is weaker than it had previously envisaged.

This section outlines the current position of the UK economy, and the OBR’s forecast for the economic outlook. This provides the backdrop for both meeting the challenge and seizing the opportunities that the next few years will bring.

2.2 UK economy

2.3 Growth

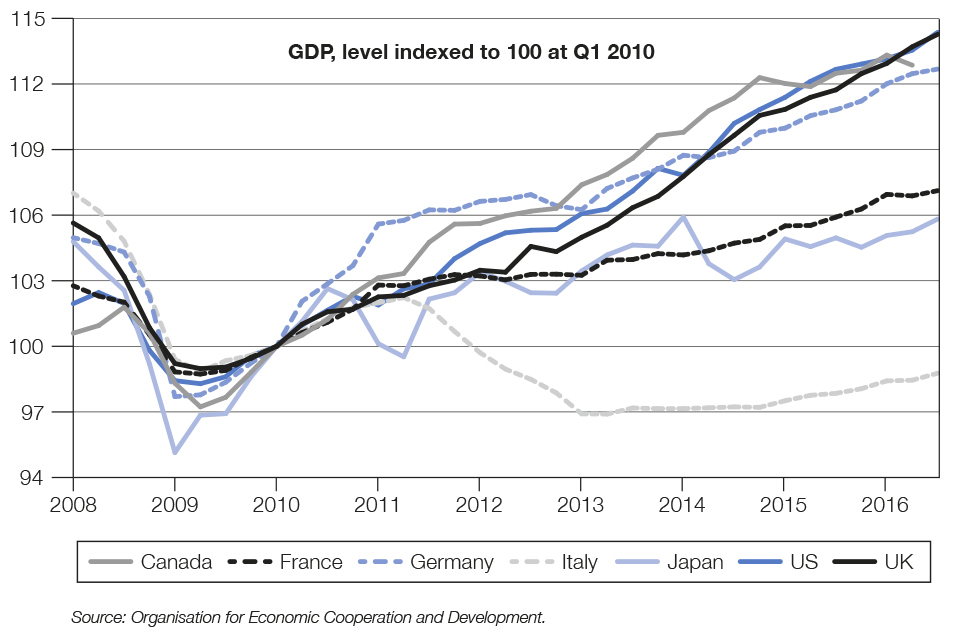

The UK economy has grown 14.3% in real terms since Q1 2010, second only to the US among major advanced economies. UK GDP grew 2.2% in 2015, and growth has remained solid in the first three quarters of 2016. GDP grew 2.3% in the year to Q3 2016, with average quarterly growth of 0.5% in 2016 to date.

On a per capita basis, UK GDP has increased 9.0% since Q1 2010, and has experienced the third fastest growth among major advanced economies since 2010. After falling during the financial crisis, GDP per capita grew slowly in the early years of the recovery, and only reached its pre-crisis peak in Q4 2015. Growth has since increased; GDP per capita grew 1.4% in 2015 and has continued to rise more recently, increasing 1.5% in the year to Q3 2016.

Household consumption growth has been consistently strong in recent years. Consumption rose by 2.5% in 2015, and growth picked up to 2.9% in the year to Q2 2016. Household saving as a proportion of disposable income has fallen from a recent peak of 11.5% in Q1 2010, and is now at 5.1%, having been broadly stable for the last three years.

Business investment increased by 5.1% in 2015, but has been weaker in recent quarters, falling by 0.8% in the year to Q2 2016. Official data on business investment in Q3 2016 will be published on 25 November 2016. Most private business surveys suggest that investment has remained subdued, and many firms cite uncertainty about future demand and the outcome of the EU negotiations as weighing on spending.

Chart 1.1 International comparison of GDP

Chart 1.1 International comparison of GDP

2.4 Trade

The total volume of exports increased 4.5% in 2015, while the volume of imports increased 5.4%. The trade in goods deficit widened to £126.4 billion while the trade in services surplus increased to £87.8 billion, combining to give a total trade deficit of £38.7 billion or 2.1% of GDP. This is in line with its average since 2010 and down from a peak of 3.0% of GDP in 2008.

The annual current account deficit was the largest on record in 2015, at 5.4% of GDP. On a quarterly basis, the deficit remained close to record highs, and wide by international and historical standards, at 5.9% of GDP in Q2 2016. The widening in recent years has been driven by a deterioration in the UK’s primary income balance, as the return on assets held overseas by UK residents was relatively weaker. There was a primary income deficit of 2.0% of GDP in 2015, in contrast to surpluses before 2012.

2.5 Prices

Consumer price growth has slowed in recent years, with the Consumer Prices Index (CPI) measure of inflation falling from a peak of 5.2% in September 2011. Falling fuel and food prices through 2014 and 2015 contributed to unusually low inflation, with CPI inflation averaging 0.0% in 2015, supporting real income growth and household spending. Inflation has risen in recent months, as fuel prices have started to increase internationally, and reached 1.0% in September 2016 before falling back to 0.9% in October. The post-referendum sterling depreciation has amplified the effect of global oil price rises, increasing the contribution of the energy and transport components to CPI inflation.

2.6 Labour market

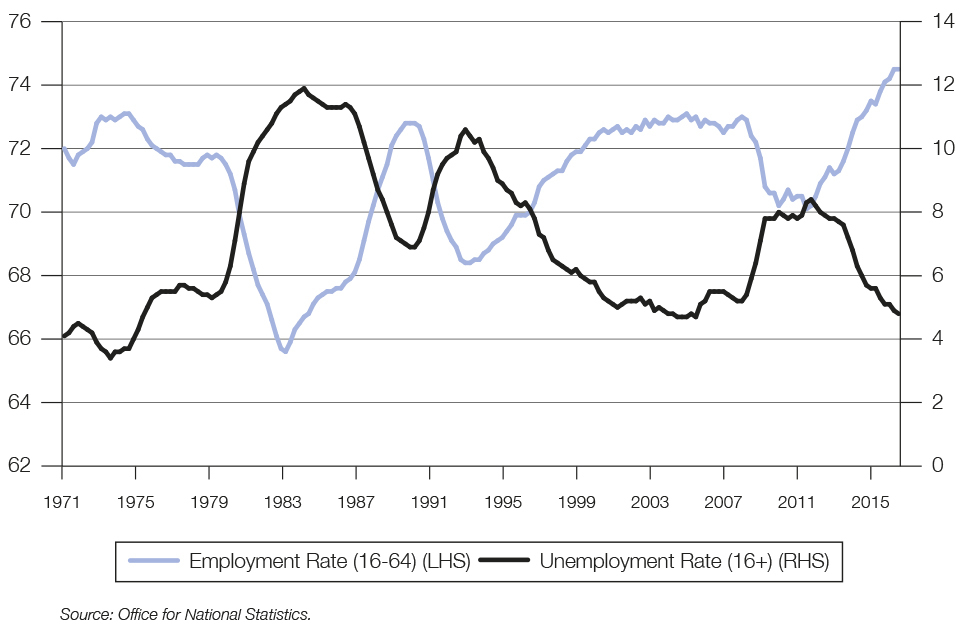

The employment rate has been rising since 2010 and stood at a record high of 74.5% in the three months to September 2016. The number of people in employment has also reached its highest ever level in recent months, and there are now over 2.7 million more people in work than in Q1 2010. Over the same period, average hours worked have increased 1.6% to 32.1 hours per week, with full-time workers accounting for 72% of employment growth. The unemployment rate was 4.8% in the three months to September 2016, its lowest in 11 years.

Chart 1.2 Employment rate and unemployment rate (percentage, quarterly)

Chart 1.2 Employment rate and unemployment rate (percentage, quarterly)

The UK has a longstanding productivity gap with other major advanced economies. In 2015, UK labour productivity, as measured on an output per hour basis, was 18 percentage points below the average of other G7 countries; 35 percentage points below Germany; and 30 percentage points below the US. UK labour productivity growth remains subdued, as in most advanced economies. The average rate of productivity growth across Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries fell to 0.9% between 2010 and 2014, compared with 1.8% in the five years before the financial crisis. Although UK productivity growth increased slightly to 0.9% in 2015, this is less than half the average growth rate experienced before the financial crisis.

With relatively slow productivity growth, earnings growth in the UK has remained subdued following the financial crisis – a trend observed in many advanced economies during this period. More recently, UK earnings growth has picked up. Total pay rose 2.3% in the three months to September 2016, compared with the same period a year earlier. Regular pay (excluding bonuses) grew 2.4% over the same period.

Some improvement in wage growth and unusually low inflation has supported increases in living standards, as measured by real household disposable income (RHDI) per capita, in recent years. RHDI per capita grew 2.8% in 2015 – the fastest rate of growth in 14 years – and has continued to increase in 2016, rising 2.0% in the year to Q2 2016.

2.7 Global economy

The global economy remains subdued, posing continued challenges for the UK economy. Global growth was 3.2% in 2015, the slowest pace since the financial crisis, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecasts that global growth will remain modest, at 3.1% in 2016 and 3.4% in 2017. Advanced economies grew 2.1% in 2015, while emerging economies grew 4.0%, the fifth consecutive year of slowing emerging economy growth. China’s growth has slowed, as policymakers seek to move to a more sustainable growth path, but, like in India, growth remains well above the global average.

Growth in global trade has also slowed in recent years to a rate well below its pre-crisis trend. World trade has grown at an average annual rate of 3.2% over the last four years, compared with an average annual rate of 7.1% in the two decades before the financial crisis. This is a weakening of the historical relationship between trade and GDP growth; global trade growth was lower than global GDP growth in 2015 and is expected to remain lower in 2016.

2.8 Economic outlook

The OBR’s Autumn Statement forecast is for slightly stronger GDP growth in 2016 than expected in March. The UK economy showed considerable momentum in the run up to the referendum, and has shown significant resilience since. Thereafter, the OBR’s forecast reflects a new set of circumstances for the UK economy, resulting from the decision to leave the EU. In the near term, economic uncertainty during the period of negotiation is likely to constrain business investment, and higher inflation, largely caused by the post-referendum sterling depreciation, is likely to put downward pressure on real incomes, weighing on household consumption growth.

The economy will then adjust to new relationships with the EU and the rest of the world over the coming years. In producing the forecast, the OBR has not attempted to predict the precise outcome of negotiations, nor the breadth and depth of new relationships that may be negotiated bilaterally with the EU or other trading partners. Instead, it has made assumptions in line with a range of external studies. As the OBR sets out, the unprecedented nature of the decision to leave the EU has increased uncertainty around the outlook for the UK economy.

The outlook for trend productivity growth is the most important and most uncertain judgement in the OBR’s economic forecast. The OBR now judges that uncertainty following the decision to leave the EU will reduce business investment. In turn, with lower investment the OBR has made a downward revision to productivity growth over the medium term. The level of potential output is forecast to be 1.5 percentage points lower than had been forecast in March. However, the OBR notes that in the absence of the referendum result it would have revised up its forecast for net migration and potential growth. As a result the OBR judges that the EU referendum result has served to reduce potential output by 2.4 percentage points.

2.9 Growth

With lower potential output over the next 5 years, the OBR expects weaker GDP growth than at Budget 2016. The OBR forecasts GDP growth to be 1.4% in 2017, rising to 1.7% in 2018, 2.1% in both 2019 and 2020, and 2.0% in 2021. GDP growth has been revised down by 0.8 percentage points in 2017 and by 0.4 percentage points in 2018, and is unchanged in both 2019 and 2020. GDP growth on a per capita basis has been revised down by the same amount, given the unchanged forecast for population growth.

Table 1.1: Summary of the OBR’s central economic forecast (1) (percentage change on a year earlier, unless otherwise stated)

| Forecast | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| GDP | 2.2 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 |

| GDP per capita | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Main components of GDP | |||||||

| Household consumption (2) | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| General government consumption | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Fixed investment | 3.4 | -0.1 | 1.2 | 3.6 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 3.3 |

| Business | 5.1 | -2.2 | -0.3 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 4.1 | 3.6 |

| General government (3) | -2.0 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 8.8 | 3.3 |

| Private dwellings (3) | 2.8 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 3.0 |

| Change in inventories (4) | -0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Net trade (4) | -0.4 | -0.2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | -0.1 | -0.1 | -0.1 |

| CPI inflation | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Employment (millions) | 31.3 | 31.7 | 31.8 | 31.9 | 32.0 | 32.2 | 32.3 |

| LFS unemployment (% rate) (5) | 5.4 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 5.4 | 5.4 |

| Productivity per hour | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| (1) All figures in this table are rounded to the nearest decimal place. This is not intended to convey a degree of unwarranted accuracy. Components may not sum to total due to rounding and the statistical discrepancy. |

| (2) Includes households and non-profit institutions serving households. |

| (3) Includes transfer costs of non-produced assets. |

| (4) Contribution to GDP growth, percentage points. |

| (5) Labour Force Survey. |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility, Office for National Statistics. |

The OBR has revised up its forecast for household consumption growth in 2016, based on recent data showing continued robust consumer spending during the year to date. However, consumption growth is then forecast to slow, as the recent decline in sterling is expected to put upward pressure on inflation and therefore restrict real income growth. This contributes to the weaker GDP growth forecast in 2017 and 2018. The OBR forecasts consumption growth of 1.2% in 2017 and 1.1% in 2018 – both 1.0 percentage point lower than forecast at Budget 2016 – before increasing to between 2.0% and 2.1% growth for the remainder of the forecast period.

As consumption growth is not expected to slow as much as household income growth, the OBR forecasts that household saving as a proportion of disposable income will fall to 3.8% in 2017, before increasing to 4.2% in 2018 and 2019, 4.3% in 2020 and 4.4% in 2021.

The downward revision to the outlook for business investment has been more substantial. A combination of weak recent data and the effect of higher uncertainty, cited by firms, mean that the OBR forecasts a 2.2% fall in business investment in 2016, followed by a 0.3% fall in 2017 – revised down by 4.7 percentage points in 2016 and 6.3 percentage points in 2017. The OBR expects that business investment will then return to growth, increasing 4.1% in 2018, 5.3% in 2019, 4.1% in 2020 and 3.6% in 2021. However, the level of investment is expected to remain permanently lower than that forecast at Budget 2016. This has the effect of depressing near-term GDP growth, and additionally slows the productive potential of the economy.

2.10 Trade

Sterling depreciated 14.2% on a trade-weighted basis between the beginning of June and the end of October. The OBR expects that this will support exports and reduce imports in the short term, with net trade adding 0.3 percentage points to GDP growth in both 2017 and 2018. In the longer term, forecasts for both import and export growth have been revised down by similar amounts, due to the loss of trade that the OBR judges will result from the UK leaving the EU. This judgement draws on a range of external studies of the effect of leaving the EU on UK trade. The effect is to leave the net trade contribution to GDP little changed from the March forecast in 2019 and 2020.

The OBR forecasts that the current account deficit will narrow, to 5.0% of GDP in 2017, 4.2% of GDP in 2018, 3.4% of GDP in 2019, 2.8% of GDP in 2020 and 2.7% of GDP in 2021. The OBR expects that recent net investment income deficits will fade and return to surplus as the rate of return on the UK’s stock of foreign assets normalises and the value of investment income received on those assets rises due to the depreciation of sterling.

2.11 Prices

The weaker exchange rate has a material effect on the OBR’s forecast for consumer prices. The depreciation is expected to put upward pressure on inflation, coupled in the short term with higher fuel prices and the drag from past falls in fuel and food prices falling out of the annual comparison. The OBR forecasts CPI inflation of 2.3% in 2017, 2.5% in 2018, 2.1% in 2019 and 2.0% in 2020 and 2021.

2.12 Labour market

The OBR forecasts that the number of people in employment will continue to increase, reaching 32.3 million in 2021. Weaker expected activity in the near term has also caused the OBR to revise its near-term forecast for the unemployment rate up slightly, compared to the forecast at Budget 2016. The unemployment rate is now forecast to be 5.2% in 2017, 5.5% in 2018, and 5.4% from 2019 to 2021.

The OBR forecasts that productivity growth will be 1.3% in 2017, 1.4% in 2018, 1.8% in 2019 and 2.0% in both 2020 and 2021. The OBR highlights that there was considerable uncertainty around the outlook for productivity pre-referendum, reflecting the marked difference across advanced economies between the weak growth seen in recent years and the preceding decades of stronger performance. As there is little by way of precedent to guide the forecast, the decision to leave the EU has increased this uncertainty around the prospects for productivity growth in the medium term.

Wages and salaries are expected to continue to increase, but the OBR now forecasts slower earnings growth than previously predicted, due to the weaker projection for productivity growth. The OBR forecasts average earnings growth of 2.4% in 2017 and 2.8% in 2018, followed by annual growth above 3.0% through to 2021.

The OBR expects that upward pressure on inflation and lower wage growth than previously anticipated will temporarily halt recent rises in living standards, with RHDI per capita forecast to fall 0.5% in 2017. RHDI per capita is then expected to return to growth, increasing 0.3% in 2018, 0.6% in 2019, 1.1% in 2020 and 1.3% in 2021.

2.13 Monetary policy

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) of the Bank of England has full operational independence to set monetary policy to meet the inflation target of 2.0%, as measured by the 12-month increase in the CPI. This is a cornerstone of the UK’s macroeconomic framework, which underpins the continued performance of the economy, including growth and employment.

On 4 August 2016 the MPC announced a monetary stimulus package to support economic growth and achieve a sustainable return of inflation to target.[footnote 2] The MPC:

-

cut Bank Rate, the Bank of England’s base interest rate, from 0.5% to 0.25%

-

extended the quantitative easing programme. The Bank of England will expand its purchases of UK government bonds by £60 billion, taking the stock of these asset purchases to £435 billion, and purchase up to £10 billion of corporate bonds, using newly created central bank reserves

-

introduced a new Term Funding Scheme to enable banks to pass on the Bank Rate cut to businesses and households

At its November meeting, the MPC voted unanimously to maintain the package of measures announced in August, and noted that the measures have supported financial conditions. Market interest rates have remained low, with the average rate on a new variable rate mortgage now below 2%. Sterling corporate bond spreads narrowed after the announcement of corporate bond purchases, reducing the cost for businesses of borrowing to invest.

2.14 Public finances

The UK’s public finances are in a much stronger position than in 2010 due to determined government action. However, the outlook for the public finances has deteriorated since Budget 2016, with disappointing tax revenues over the first half of this year, a weaker economic outlook weighing on receipts from income taxes, and higher spending by local authorities, public corporations, and on welfare benefits.

Continuing to reduce the deficit is vital to delivering a strong and stable economy. The government remains committed to returning the public finances to balance, ensuring that the UK lives within its means. However, given the weaker growth outlook, and the period of uncertainty that is likely while the UK negotiates a new relationship with the EU, the government will no longer seek to reach a fiscal surplus in this Parliament.

The government’s objective is to return the public finances to balance at the earliest possible date in the next Parliament. To ensure this objective is reached, the government has published a new Charter for Budget Responsibility. This commits to reducing the structural deficit to below 2% of GDP and to have debt falling as a percentage of GDP by the end of this Parliament. This new fiscal framework ensures the public finances continue on the path to sustainability, while providing the flexibility needed to support the economy in the near term.

Due to the pressure on the public finances, the government has chosen to focus discretionary support on highly-targeted investments to boost the productive capacity of the economy. This will, over the medium and long term, be the most important factor for continuing to raise living standards across the UK. Otherwise, the government is sticking to its overall spending plans set out in Spending Review 2015 and has reinforced its controls on welfare spending. All other new policies announced in Autumn Statement 2016 have been funded from savings or taxation.

2.15 Public finances since Budget 2016

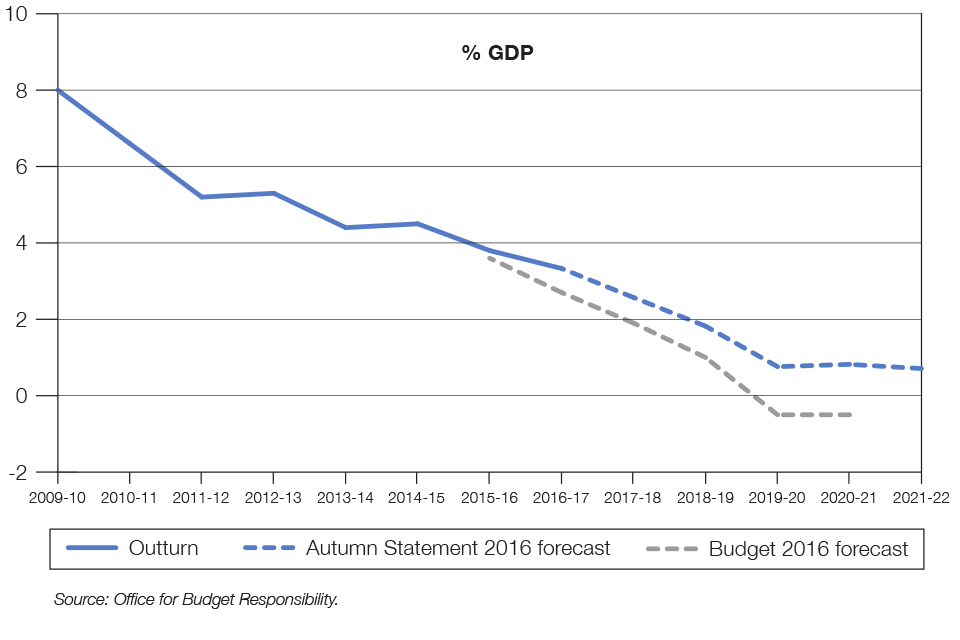

Over the last 6 years the deficit has been cut by almost two-thirds from its 2009-10 post‑war peak of 10.1% of GDP to 4.0% last year.[footnote 3] However, borrowing and debt remain high, and the OBR judges that the economic and fiscal outlook for the UK has deteriorated in the wake of the EU referendum. As a result, the OBR’s forecast shows that the public finances will no longer reach a surplus by 2019-20.

Public sector net borrowing (PSNB) is higher than forecast at Budget 2016 in every year and by £32 billion in 2020-21, reflecting primarily the impact of lower growth on tax revenues. The deterioration in the fiscal outlook since Budget 2016 is driven by a number of factors:

-

receipts are £15 billion lower by 2020-21 due in large part to lower income tax and National Insurance contributions (NICs) partly offset by higher corporation and other taxes. Total income tax and NICs receipts are forecast to be £23 billion lower by 2020-21, of which £7 billion can be attributed to weaker outturn data, £9 billion to slower earnings growth over the forecast period, and a further £3 billion to higher rates of incorporation which reduces the effective tax rate[footnote 4]

-

spending is £4 billion higher by 2020-21 due to previously announced decisions not to go ahead with changes to the Personal Independence Payment (PIP) proposed at Budget 2016, changes to the Universal Credit roll out schedule, and higher inflation which offset savings from lower debt interest payments

-

classification changes add a further £4 billion to borrowing in 2020-21. These include the Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) revision to the accounting treatment of corporation tax payments and the reclassification of non-England housing associations to the public sector

The OBR’s forecast also includes new policies announced in the Autumn Statement which target investment to raise the UK economy’s long-term productive capacity.

Table 1.2: Changes to the OBR forecast for public sector net borrowing since Budget 2016 (£ billion)

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Budget 2016 | 55.5 | 38.8 | 21.4 | -10.4 | -11.0 |

| Total forecast changes since Budget 2016 | 11.7 | 17.6 | 20.6 | 24.0 | 22.1 |

| of which (1) | |||||

| Receipts forecast | 6.7 | 9.3 | 13.1 | 15.2 | 15.3 |

| Spending forecast | 4.5 | 7.9 | 7.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 |

| Classification effects | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 | 6.4 | 4.1 |

| Total effect of government decisions since Budget 2016 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 4.5 | 8.4 | 9.6 |

| Total changes since Budget 2016 | 12.7 | 20.2 | 25.1 | 32.4 | 31.87 |

| Autumn Statement 2016 | 68.2 | 59.0 | 46.5 | 21.9 | 20.7 |

| (1) Equivalent to lines from 'Table 1.3 of the November 2016 Economic and fiscal outlook'; full references available in Autumn Statement 2016 data sources. | |||||

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations. |

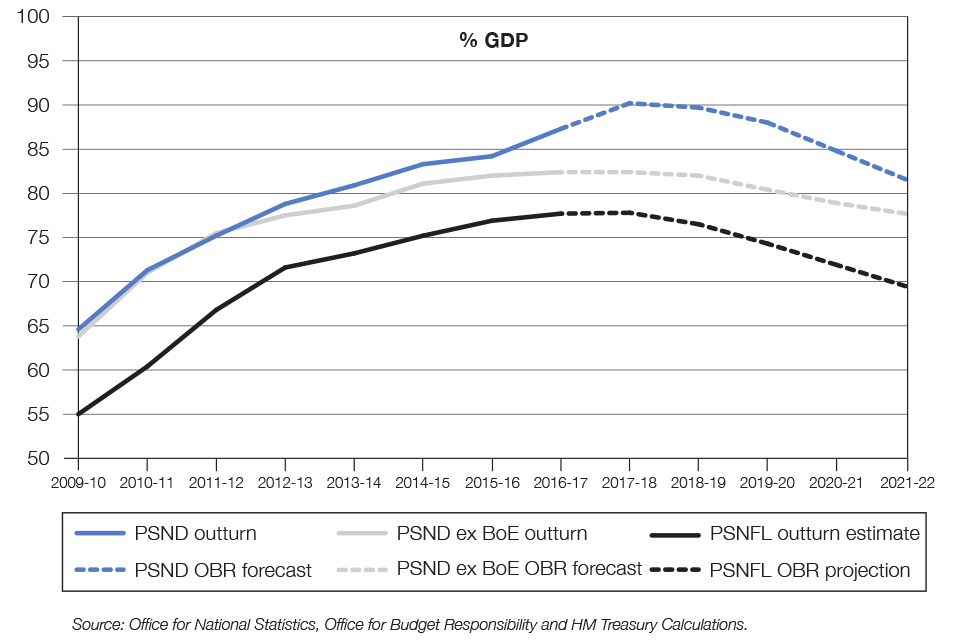

Public sector net debt (PSND) is also higher than forecast at Budget 2016 in every year, and peaks at 90.2% of GDP in 2017-18. This is partly due to higher government borrowing over this period. However, much of the near-term increase in debt is due to the liabilities created by the Bank of England through its monetary policy operations announced in August 2016, which will unwind from 2020-21. As noted by the OBR, some assets acquired by the Bank of England through these interventions are treated as illiquid and are not netted off against PSND. However, the loans extended are secured on collateral and are therefore very unlikely to generate losses for the public sector. The fiscal impact of these interventions is discussed in more detail below.

2.16 Fiscal framework

The government remains committed to returning the public finances to balance at the earliest possible date. In light of the changed economic circumstances that date will be in the next Parliament. To support this objective, the government has today published a revised Charter for Budget Responsibility which sets out the following targets for this Parliament:

-

a mandate to reduce cyclically-adjusted PSNB below 2% of GDP by 2020-21

-

a supplementary target for PSND as a percentage of GDP to be falling in 2020-21

-

a supplementary target to ensure that expenditure on welfare in 2021-22 is contained within a predetermined cap and margin set by the Treasury at Autumn Statement 2016

The government’s new fiscal framework strikes the right balance between restoring the public finances to health in the medium term whilst providing sufficient flexibility to support the economy in the near term.

2.17 Fiscal strategy

The new fiscal framework provides the space for additional investment in the productive capacity of the UK economy, the centrepiece of which is a new National Productivity Investment Fund (NPIF). The NPIF will be targeted at four areas that are critical for productivity: transport, digital communications, R&D and housing. It will provide for an extra £23 billion of spending between 2017-18 and 2021-22. The new fiscal framework also allows automatic stabilisers to support the economy during a period of near-term uncertainty as the UK negotiates its departure from the EU.

At the same time the government will continue to restore the underlying public finances to health. It will do so by sticking to departmental resource spending plans set out at Spending Review 2015 and delivering the £3.5 billion of additional savings in 2019-20 announced at Budget 2016. And it will continue to control welfare spending through a reformed welfare cap. All new policies announced in the Autumn Statement, with the exception of the NPIF, are fully funded through savings or additional tax revenues.

The government’s plan for tackling the structural deficit and to have debt falling by the end of this Parliament leaves it well placed to return the public finances to overall balance as soon as possible in the next Parliament, when the UK’s future relationship with the EU is clear.

Table 1.3: Overview of the OBR’s borrowing forecast as a percentage of GDP

| Outturn | Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| Public sector net borrowing | 4.0 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.7 |

| Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing | 3.8 | 3.3 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 |

| Treaty deficit (1) | 4.0 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Memo: Output gap (2) | -0.2 | -0.2 | -0.7 | -0.6 | -0.3 | -0.1 | 0.0 |

| Memo: Total policy decisions (3) | 0.0 | -0.2 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.3 | -0.4 | |

| (1) General government net borrowing on a Maastricht basis. | |||||||

| (2) Output gap measured as a percentage of potential GDP. | |||||||

| (3) Equivalent to the 'Total policy decisions' line in Table 2.1. | |||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics, Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations. |

Table 1.4: Overview of the OBR’s debt forecast as a percentage of GDP

| Outturn | Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| Public sector net debt (1) | 84.2 | 87.3 | 90.2 | 89.7 | 88.0 | 84.8 | 81.6 |

| Public sector net debt ex Bank of England (1) | 82.0 | 82.4 | 82.4 | 82.0 | 80.4 | 78.9 | 77.7 |

| Public sector net financial liabilities (2) | 76.9 | 77.7 | 77.8 | 76.5 | 74.3 | 71.9 | 69.5 |

| Treaty debt (3) | 87.8 | 88.7 | 89.2 | 88.7 | 87.2 | 85.5 | 84.2 |

| (1) Debt at end March; GDP centred on end March. | |||||||

| (2) Public sector net financial liabilities at end of March, GDP centred on end March; outturn estimate. | |||||||

| (3) General government gross debt on a Maastricht basis. | |||||||

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

2.18 Performance against the government’s fiscal targets

The OBR’s ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’ provides an assessment of the government’s performance against the new fiscal mandate. It shows that the government is on track to meet its fiscal mandate to reduce cyclically-adjusted PSNB below 2% of GDP by the end of this Parliament. The structural deficit is forecast to reach 0.8% of GDP in 2020-21.

Chart 1.3 Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing from 2009-10 to 2021-22

Chart 1.3 Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing from 2009-10 to 2021-22

The OBR’s ‘Economic and fiscal outlook’ also shows the government is on track to meet its supplementary target to have debt falling as a percentage of GDP by the end of this Parliament. PSND falls as a percentage of GDP in every year from 2018-19 onwards. The OBR also forecasts that welfare spending will be within the new cap and margin set in the Autumn Statement.

Chart 1.4 Public sector debt from 2009-10 to 2021-22

Chart 1.4 Public sector debt from 2009-10 to 2021-22

The government remains committed to bringing down the UK’s Treaty deficit in line with the 3% target set out in the Stability and Growth Pact. The OBR’s forecast indicates that this target will be met in 2017-18.

2.19 Supplementary fiscal aggregates

In order to maintain a consistent measure of the government’s fiscal position, the government’s target for debt will continue to be set in reference to PSND. However, while the liabilities created by the Bank of England to fund its monetary policy operations have a significant impact on PSND, the assets acquired through those operations are not fully captured in this measure.

To provide a more complete picture of the public sector balance sheet and in line with recommendations of independent experts[footnote 5], the government has asked the ONS to develop two supplementary fiscal aggregates.[footnote 6] The OBR has been asked to forecast these alongside PSND to provide additional information concerning the fiscal implications of the Bank’s operations and the sustainability of the public finances. These supplementary aggregates are:

-

PSND excluding the Bank of England (PSND ex BoE) – which deducts the assets and liabilities held on the Bank of England’s balance sheet from PSND

-

Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL) – a broader fiscal aggregate which recognises all public sector financial assets and liabilities recorded in the national accounts

2.20 Public spending

With the deficit still sizeable, control of public spending and delivery of efficiencies is vital. The government is committed to the overall plans for departmental resource spending set out at Spending Review 2015. In the Autumn Statement, new spending initiatives, with the exception of the NPIF, have been fully funded.

2.21 Efficiency Review

As announced at Budget 2016, the government intends to identify £3.5 billion of savings in 2019-20. The government intends to allocate £1 billion of these savings for re-investment in priority areas. (7)

The Efficiency Review was launched to help identify these savings and the government will report on progress in autumn 2017. Ongoing improvement in efficiency should be part of business-as-usual activity across the public sector. The Efficiency Review will look to embed a culture where incremental improvements in the efficiency of public services are made year on year.

Alongside this, the Treasury is reviewing its approach to spending control, with the aim of improving how it works with departments. This will ensure that the framework continues to provide the right incentives for departments to identify efficiencies and deliver high quality public services within budget, that public expenditure provides value for money, and that it can be reprioritised as necessary.

2.22 Departmental Expenditure Limits

Budget 2016 set out that departmental resource spending will continue to grow with inflation in 2020-21. Departmental spending will also grow with inflation in 2021-22.

The government will meet the commitments on public spending set out for this Parliament: including commitments to priority public services, to international development and defence, and to pensioners. The government will continue to constrain public spending in the next Parliament to reach a balanced budget and live within its means. The commitments it is able to make on protecting public spending priorities in the next Parliament will need to be determined in light of evolving prospects for the fiscal position. The government will do this at the next Spending Review.

Table 1.5 sets out the path for Total Managed Expenditure (TME), Public Sector Current Expenditure (PSCE), and Public Sector Gross Investment (PSGI) to 2021-22.

Table 1.5: Total Managed Expenditure (1), (2) (in £ billion, unless otherwise stated)

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current expenditure | ||||||

| Resource AME | 370.2 | 386.9 | 400.3 | 407.2 | 421.1 | 439.8 |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation (3) | 309.0 | 304.2 | 306.3 | 305.6 | 311.5 | 317.6 |

| Ring-fenced depreciation | 20.6 | 21.9 | 22.8 | 23.3 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Total public sector current expenditure | 699.8 | 713.0 | 729.4 | 736.2 | 754.5 | 780.1 |

| Capital expenditure | ||||||

| Capital AME (4) | 26.6 | 26.7 | 25.8 | 27.3 | 30.4 | 32.0 |

| Capital DEL (4) | 52.3 | 57.2 | 59.2 | 60.2 | 70.6 | 74.2 |

| Total public sector gross investment | 79.0 | 84.0 | 85.1 | 87.5 | 101.1 | 106.3 |

| Total managed expenditure | 778.8 | 797.0 | 814.5 | 823.7 | 855.6 | 886.4 |

| Total managed expenditure (% of GDP) | 39.9% | 39.8% | 39.1% | 38.0% | 38.0% | 37.8% |

| (1) Budgeting totals are shown including the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast Allowance for Shortfall. Resource DEL excluding ring-fenced depreciation is the Treasury's primary control within resource budgets and is the basis on which departmental Spending Review settlements are agreed. The OBR publishes Public Sector Current Expenditure (PSCE) in DEL and AME, and Public Sector Gross Investment (PSGI) in DEL and AME. A reconciliation is published by the OBR. | ||||||

| (2) The treatment of spending on Research and Development (R&D) has been updated to align with the revised treatment in the National Accounts. It is now treated as capital, rather than resource, spending. This adjustment was made in AME in the OBR's March forecast. In the current forecast R&D spending has moved from AME to DEL. More detail can be found in the OBR's Economic and Fiscal Outlook. | ||||||

| (3) In 2016-17 the Scottish Government resource DEL block grant has been adjusted by £5.5bn to reflect the devolution of SDLT and Landfill tax and the creation of the Scottish Rate of Income Tax. The resource DEL block grant has been adjusted by £12.4bn, £13.2bn, and £13.8bn from 2017-18 to 2019-20. This reflects the implementation of the Fiscal Framework agreed with the Scottish Government alongside the devolution of further Income Tax powers, Air Passenger Duty and revenues from Scottish courts. Resource DEL numbers for 2020-21 and 2021-22 are indicative as budgets have not been set. | ||||||

| (4) The OBR has revised the treatment of capital grants from central government to housing associations. In effect this switches spending from capital DEL to capital AME, so is neutral for overall capital spending. More detail can be found in the OBR's Economic and Fiscal Outlook. | ||||||

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations. |

2.23 Welfare cap

The government introduced the welfare cap at Budget 2014 to strengthen control and improve Parliamentary accountability of welfare spending. This followed the trebling of spending on working-age welfare in real terms between 1980 and 2014.[footnote 7] A full list of the benefits and tax credits that are within the scope of the welfare cap is set out at Annex B.

As a result of previous announcements on changes to tax credits and the PIP, the government has reassessed the level of the welfare cap. To maintain control of welfare spending the government is introducing a new medium-term welfare cap. The cap is based on the OBR forecast in the Autumn Statement of the benefits and tax credits in scope as set out in Annex B, and will apply to welfare spending in 2021-22. To manage unavoidable fluctuations in welfare spending there will be a margin rising to 3% above the cap; the cap will only be breached if spending exceeds the cap plus the margin at the point of assessment.

Performance against the cap will be formally assessed by the OBR in 2020-21. In the interim years, progress towards the cap will be managed internally, based on the OBR’s monitoring of forecasts of welfare spending. This will avoid the government having to make short-term responses to changes in the welfare forecast, while ensuring welfare spending remains sustainable in the medium term. Further details are set out in the revised draft Charter for Budget Responsibility, published alongside the Autumn Statement.

Table 1.6: New welfare cap (in £ billion, unless otherwise stated)

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cap | - | - | - | - | - | 126.0 |

| Interim pathway | 119.8 | 119.6 | 120.1 | 120.5 | 123.2 | - |

| Margin (%) | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Source: HM Treasury. |

2.24 Devolved administrations

The devolved administrations’ block grants will be adjusted in line with the Barnett formula, as set out in the Statement of Funding Policy. As a result of spending decisions taken by the UK government at the Autumn Statement, the application of the Barnett formula will provide each of the devolved administrations with additional funding to be allocated according to their own priorities. The Scottish Government’s block grant will be further adjusted to reflect its tax powers as agreed in the Scottish Government’s Fiscal Framework.

2.25 Financial transactions

Some policy measures do not directly affect PSNB in the same way as conventional spending or taxation. These include financial transactions that directly affect only the central government net cash requirement (CGNCR) and the PSND. Table 1.7 shows the effect of the financial transactions announced at the Autumn Statement on CGNCR.

Table 1.7: Financial transactions from 2016-17 to 2021-22 (1) (£ million)

| 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i British Business Bank Venture Capital | 0 | 15 | 35 | 55 | 75 | * |

| ii Northern Powerhouse Investment Fund | 10 | 20 | 15 | 30 | 20 | * |

| iii Midlands Engine Investment Fund | 5 | 35 | 25 | 40 | 25 | * |

| iv Digital Infrastructure Investment Fund | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | * |

| Total policy decisions | 15 | 170 | 175 | 225 | 220 | * |

| (1) Costings reflect the OBR's latest economic and fiscal determinants, and are presented on a UK basis. | ||||||

| Source: HM Treasury |

2.26 Financial assets

The government is committed to returning the financial sector assets acquired in 2008-09 to the private sector in a way that maximises value for taxpayers. To date, the government has recovered over £80 billion of proceeds from these assets.[footnote 8] Subject to market conditions the plan for asset disposals is as follows:

-

Lloyds – the government launched a trading plan on 7 October 2016, with a view to returning Lloyds Banking Group fully to the private sector by the end of 2017‑18. The trading plan involves gradually selling shares in the market over time in an orderly and measured way

-

RBS – the government will continue to seek opportunities for disposals, but the need to resolve legacy issues makes it unlikely that disposals will occur in the near term

-

UK Asset Resolution (UKAR) – UKAR has launched a programme of sales of Bradford & Bingley (B&B) mortgage assets, expected to raise sufficient proceeds for B&B to repay the £15.65 billion debt to the Financial Services Compensation Scheme, who in turn will repay the corresponding loan from the Treasury. The programme of sales is expected to conclude in full before the end of 2017-18. UKAR will also look to make sales of other assets over the course of the Parliament, currently expected to total £5 billion

The government continues to explore options for the sale of wider corporate and financial assets, where there is no longer a policy reason to retain them. The government is continuing to pursue the sale of the pre-2012 income contingent repayment student loan book, and subject to market conditions intends to launch the first sale in early 2017. The process to transfer the Green Investment Bank to private ownership is ongoing.

Following consultation the government has decided that HM Land Registry should focus on becoming a more digital data-driven registration business, and to do this will remain in the public sector. Modernisation will maximise the value of HM Land Registry to the economy, and should be completed without a need for significant Exchequer investment.

2.27 Debt management

The government’s revised financing plans for 2016-17 are summarised at Annex A.

3. Policy decisions

The following chapters set out all Autumn Statement policy decisions. Unless stated otherwise, the decisions set out in these chapters are ones which are announced at the Autumn Statement.

Table 2.1 shows the cost or yield of all new Autumn Statement decisions with a direct effect on PSNB in the years up to 2021-22. This includes tax measures, changes to allocated DEL and measures affecting AME.

The government is also publishing the methodology underlying the calculation of the fiscal impact of each policy decision. This is included in the supplementary document Autumn Statement 2016 policy costings published alongside the Autumn Statement.

Table 2.1: Autumn Statement 2016 policy decisions (£ million) (1)

| Head | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 (2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes to Inherited Policy | |||||||

| 1 Personal Independence Payment: not implementing Budget 2016 measure | Spend | -15 | -605 | -1,250 | -1,400 | -1,390 | -1,410 |

| 2 Universal Credit: reprofile | Spend | -20 | -295 | -445 | -185 | -110 | -425 |

| 3 Disability benefits: eligibility test change | Spend | -20 | -20 | -20 | -20 | -15 | -15 |

| 4 Social Sector Rent downrating: exemptions | Spend | 0 | -5 | -10 | -15 | -15 | -15 |

| 5 Pay to Stay: do not implement | Spend | 0 | -280 | -15 | -100 | -100 | -105 |

| 6 Local Housing Allowance: adjusted roll-out and supported housing fund | Spend | 0 | 0 | -305 | -265 | +160 | +125 |

| Public Spending | |||||||

| 7 Efficiency Review: reinvestment | Spend | 0 | 0 | 0 | -1,000 | - | - |

| National Productivity Investment Fund | |||||||

| 8 Housing | Spend | -10 | -1,465 | -2,060 | -2,490 | -2,145 | - |

| 9 Transport | Spend | 0 | -475 | -790 | -705 | -1,050 | - |

| 10 Telecoms | Spend | 0 | -25 | -150 | -275 | -290 | - |

| 11 Research and Development | Spend | 0 | -425 | -820 | -1,500 | -2,000 | - |

| 12 Long-term investment | Spend | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | -7,000 |

| An economy that works for everyone | |||||||

| 13 Fuel Duty: freeze in 2017-18 | Tax | 0 | -845 | -845 | -860 | -885 | -910 |

| 14 Universal Credit: reduce taper to 63% | Spend | 0 | -35 | -175 | -400 | -570 | -700 |

| 15 NS&I Investment Bond | Spend | 0 | -45 | -85 | -90 | -45 | 0 |

| 16 Right to Buy: expand pilot | Spend | 0 | -25 | -90 | -110 | -25 | 0 |

| 17 National Living Wage: additional enforcement | Spend | 0 | -5 | -5 | -5 | - | - |

| Tax reform | |||||||

| 18 Insurance Premium Tax: 2ppt increase from June 2017 | Tax | 0 | +680 | +840 | +840 | +845 | +855 |

| 19 National Insurance contributions: align primary and secondary thresholds | Tax | 0 | +170 | +145 | +145 | +145 | +145 |

| 20 Salary Sacrifice: remove tax and NICs advantages | Tax | -10 | +85 | +235 | +235 | +235 | +260 |

| 21 Money Purchase Annual Allowance: reduce to £4,000 per annum | Tax | 0 | +70 | +70 | +70 | +75 | +75 |

| 22 Company Car Tax: reforms to incentivise ULEVs | Tax | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | +25 | +5 |

| Avoidance, Evasion, and Imbalances | |||||||

| 23 VAT Flat Rate Scheme: 16.5% rate for businesses with limited costs | Tax | 0 | +195 | +130 | +130 | +125 | +115 |

| 24 Disguised Remuneration: extend to self-employed and remove company deduction | Tax | +10 | +25 | +180 | +310 | +40 | +65 |

| 25 Adapted motor vehicles: prevent abuse | Tax | 0 | +20 | +15 | +15 | +15 | +15 |

| 26 Employee Shareholder Status: abolish tax advantage for new schemes | Tax | * | +10 | +15 | +15 | +25 | +50 |

| 27 HMRC: administration and operational measures | Tax | -115 | -20 | +50 | +170 | +215 | +180 |

| 28 Offshore Tax: close loopholes and improve reporting | Tax | 0 | +10 | +25 | +15 | +60 | +70 |

| 29 Money Service Businesses: bulk data gathering | Tax | 0 | 0 | +5 | +5 | +10 | +10 |

| Other Tax and Spending | |||||||

| 30 Overseas Development Assistance: meet 0.7% GNI target | Spend | 0 | +80 | +210 | 0 | - | - |

| 31 MoJ: prison safety | Spend | 0 | -125 | -245 | -185 | - | - |

| 32 Grammar Schools expansion | Spend | 0 | -60 | -60 | -60 | -60 | - |

| 33 Tax credits: correcting awards | Spend | -95 | -80 | -65 | -55 | -40 | -25 |

| 34 Biomedical catalysts and Technology Transfers | Spend | 0 | -40 | -60 | -60 | -60 | - |

| 35 DCMS Spending | Spend | -10 | -10 | -20 | -15 | -10 | - |

| 36 Midlands Rail Hub | Spend | 0 | -5 | -5 | 0 | - | - |

| 37 Scotland City Deals and Fiscal Framework | Spend | 0 | -25 | -60 | -75 | -50 | -25 |

| 38 Mayfield Review of Business Productivity | Spend | 0 | -5 | -5 | -5 | - | - |

| 39 Business Rates: support for broadband and increase Rural Rate Relief | Tax | 0 | -10 | -15 | -15 | -20 | -25 |

| 40 Gift Aid: reforms | Tax | 0 | * | -10 | -15 | -15 | -20 |

| 41 Museums and Galleries tax relief | Tax | 0 | -5 | -30 | -30 | -30 | -30 |

| 42 Social Investment Tax Relief: implement with a £1.5m cap | Tax | 0 | +10 | +5 | +5 | * | -5 |

| 43 Offpayroll working: implement consultation reforms | Tax | 0 | +25 | +20 | +20 | +25 | +25 |

| Total policy decisions | -285 | -3,555 | -5,695 | -7,960 | -6,925 | -8,715 | |

| Total policy decisions excluding NPIF and inherited policy (3) | -220 | +40 | +170 | -5 | +30 | +130 | |

| Total tax policy decisions | +25 | +375 | +640 | +720 | +565 | +555 | |

| Total spending policy decisions | -310 | -3,930 | -6,335 | -8,680 | -7,490 | -9,270 | |

| * negligible | ||||||||

| (1) Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. | ||||||||

| (2) At Spending Review 2015, the government set departmental spending plans for RDEL for years up to 2019-20 and CDEL for years up to 2020-21. RDEL budgets have not been set for most departments for 2020-21 and beyond and CDEL for 2021-22. Given this, RDEL figures are not set out for 2020-21 and beyond and specific measures of CDEL are not set out for 2021-22. | ||||||||

| (3) Excluding measures 1-12 on the scorecard. | ||||||||

4. Productivity

4.1 Introduction

Raising productivity is the central long-term economic challenge facing the UK and will be a key area of focus for the forthcoming Industrial Strategy. Productivity determines living standards in the long term and improving it is the key to increasing wages. If the UK raised its productivity by one percentage point every year, within a decade it would add £240 billion to the size of the economy; £9,000 for every household in Britain. The government’s approach to raising productivity, set out in the 2015 Productivity Plan, is based on:

-

encouraging long-term investment in economic capital, such as technology, innovation, infrastructure, and skills

-

creating a dynamic economy which ensures resources are put to their best use

The fundamentals that underpin this plan have not changed. There has been a sustained worldwide slowdown in productivity since the financial crisis, which has exacerbated a long-standing gap between the UK and the most productive nations.[footnote 9] The vote to leave the EU presents new opportunities and challenges, in particular to maintain and take advantage of openness to trade, investment, and competition. The government will continue to focus on driving up productivity and taking action to close the UK’s productivity gap over the long term through promoting increased investment, particularly in innovation and infrastructure; a more flexible planning system; an open, trading economy; and a skilled workforce.

The Autumn Statement provides the financial backbone for the government’s forthcoming Industrial Strategy. The strategy will set out the broader framework for government and business to work together to address key economic challenges such as building the skills base the economy needs and turning great ideas into commercial success.

4.2 National Productivity Investment Fund

Improving productivity requires targeted and sustained investment. The government prioritised capital spending at Spending Review 2015 and is now setting out plans to go further. The Autumn Statement announces a new NPIF which will be targeted at 4 areas that are critical for improving productivity: housing, transport, digital communications, and research and development (R&D).

The NPIF will provide for £23 billion of spending between 2017-18 and 2021-22. This builds on existing plans for major investment over this Parliament, including the biggest affordable house building programme since the 1970s, resurfacing 80% of the strategic road network, the largest investment in the railways since Victorian times,[footnote 10] and prioritising science and innovation spending. The NPIF will take total spending on housing, economic infrastructure, and R&D to £170 billion over the next 5 years.

As a result of measures taken at Spending Review 2015 and the Autumn Statement, Public Sector Gross Investment is forecast to be at least 4% of GDP in each year of this Parliament and higher than in every year from 1993-94 until the financial crash.[footnote 11], [footnote 12]

This new investment will fund projects that demonstrate a clear and strong contribution to economic growth.

The NPIF will provide additional support in order to:

-

accelerate new housing supply

-

tackle congestion on the roads and ensure the UK’s transport networks are fit for the future

-

support the market to roll out full-fibre connections and future 5G communications, delivering a step change in broadband speed, security, and reliability

-

enhance the UK’s position as a world leader in science and innovation

The Autumn Statement sets out the priority areas for this new investment. Specific projects will be decided in due course, using value for money assessments, following HM Treasury standards. Where relevant, expert sector bodies such as Highways England, the Homes and Communities Agency, and UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) will make this assessment. There are no set departmental budgets for 2021-22, so allocations within the package for that year will be made in due course.

Table 3.1: National Productivity Investment Fund (£ million) (1)

| 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 (4) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | |||||

| Accelerated construction | 285 | 635 | 665 | 380 | * |

| Affordable housing (2) | 1,120 | 1,125 | 880 | 340 | * |

| Housing Infrastructure Fund | 60 | 300 | 945 | 1,425 | * |

| Transport | |||||

| Roads and local transport | 365 | 500 | 430 | 650 | * |

| Next generation vehicles | 75 | 100 | 110 | 115 | * |

| Digital railways enhancements | 30 | 55 | 165 | 285 | * |

| Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford corridor | 5 | 135 | 0 | 0 | * |

| Digital Communications (3) | |||||

| Fibre and 5G investment | 25 | 150 | 275 | 290 | * |

| Research and Development | |||||

| Research and Development funding | 425 | 820 | 1,500 | 2,000 | * |

| Total | 2,390 | 3,820 | 4,970 | 5,485 | 7,000 |

| (1) Figures represent the total costs associated with the funding allocations announced at the Autumn Statement, including the impact on Devolved Administration budgets through the application of the Barnett formula. | |||||

| (2) The affordable housing line includes the impact on Housing Association spending of £1.4 billion extra capital grant from central government to fund 40,000 new homes, and introducing tenure flexibility across the Affordable Homes Programme. | |||||

| (3) Figures show PSGI impact of policies only, and do not include funding for the Digital Infrastructure Investment Fund. | |||||

| (4) Capital budgets have not yet been set for 2021-22. Allocation of the £7 billion will be made in due course alongside wider capital budgets. | |||||

| Source: HM Treasury. |

The government is investing UK-wide in sectors for which it retains responsibility under the devolution settlements. The Barnett formula will be applied in the usual way, and where responsibility sits with the devolved administrations they will be able to use this significant funding boost to invest according to their own priorities for productivity and growth.

4.3 Housing

The government will publish a Housing White Paper shortly, setting out a comprehensive package of reform to increase housing supply and halt the decline in housing affordability. To help deliver this, the Autumn Statement announces:

-

Housing Infrastructure Fund – a new Housing Infrastructure Fund of £2.3 billion by 2020-21, funded by the NPIF and allocated to local government on a competitive basis, will provide infrastructure targeted at unlocking new private house building in the areas where housing need is greatest. This will deliver up to 100,000 new homes. The government will also examine options to ensure that other government transport funding better supports housing growth (8)

-

Affordable homes – the government will relax restrictions on grant funding to allow providers to deliver a mix of homes for affordable rent and low cost ownership, to meet the housing needs of people in different circumstances and at different stages of their lives. The NPIF will provide an additional £1.4 billion to deliver an additional 40,000 housing starts by 2020-21 (8)

Accelerated construction – In early October, the government announced that it would pilot accelerated construction on public sector land, backed by up to £2 billion of funding. To meet this commitment, the government will invest £1.7 billion by 2020-21 through the NPIF to speed up house building on public sector land in England through partnerships with private sector developers. The devolved administrations will receive funding through the Barnett formula in the usual way. (8)

Right to Buy – The government will fund a large-scale regional pilot of the Right to Buy for housing association tenants. Over 3,000 tenants will be able to buy their own home with Right to Buy discounts under the pilot. (16)

4.4 Economic infrastructure

4.5 National Infrastructure Commission

Economic infrastructure (transport, energy, flood defences, water, waste, and digital communications) is crucial for the economy and for people’s daily lives. The government has put infrastructure at the heart of its economic strategy and has set up the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) to provide expert advice on the country’s strategic infrastructure needs and independent recommendations on how to meet them. At Spending Review 2015, the government announced it would increase transport spending by 50% to invest £61 billion in this Parliament. Including the additional investment provided by the NPIF, annual central government investment in economic infrastructure will increase by almost 60% from £14 billion in 2016-17 to £22 billion in 2020-21.[footnote 13]

The government’s long-term investment decisions will be informed by the NIC to ensure they are targeted at the UK’s most critical infrastructure needs. To ensure the NIC’s recommendations are affordable, the government has set the NIC a fiscal remit. Government investment in the areas the NIC covers will rise to over 1% of GDP by 2020-21. The fiscal remit invites the NIC to set out recommendations on the assumption that spending on infrastructure will lie between 1% and 1.2% of GDP each year from 2020 to 2050. This would mark a sustained, long-term increase in infrastructure investment. The government will take all final spending decisions.

NIC study on Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford corridor – The government welcomes the NIC’s interim report into the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford growth corridor, accepts the recommendation for an Oxford-Cambridge expressway,[footnote 14] and will provide £27 million in development funding. The government will also bring forward £100 million to accelerate construction of the East-West Rail line western section and allocate £10 million in development funding for the central rail section. The government welcomes the NIC’s work looking at a range of delivery models for housing and transport in the corridor, including development corporations, and will carefully consider its final recommendations. Following a successful public call for ideas, the government has also asked the NIC to undertake a new study on how emerging technologies can improve infrastructure productivity. (9)

4.6 Transport

Roads and local transport – The NPIF will provide an additional £1.1 billion by 2020‑21 in new funding to relieve congestion and deliver much-needed upgrades on local roads and public transport networks. On strategic roads, an extra £220 million will be invested to tackle key pinch-points. The government will recommit to the National Roads Fund announced at Summer Budget 2015. (9)

Future transport – The NPIF will invest a further £390 million by 2020-21 to support ultra-low emission vehicles (ULEVs), renewable fuels, and connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs). This includes £80 million for ULEV charging infrastructure, £150 million in support for low emission buses and taxis, £20 million for the development of alternative aviation and heavy goods vehicle fuels, and £100 million for new UK CAV testing infrastructure. In addition to the tax incentives for ULEVs in company tax and salary schemes set out in the tax chapter, from today to the end of March 2019 the government will also offer 100% first-year allowances to companies investing in charge-points for electric vehicles. (9)

Rail: capacity and smart ticketing – From 2018-19 to 2020-21, the NPIF will allocate an additional £450 million to trial digital signalling technology, to expand capacity, and improve reliability. Around £80 million will be allocated to accelerate the roll out of smart ticketing including season tickets for commuters in the UK’s major cities. Construction of High Speed 2 Phase 1 will start next year, the government has announced its preferred route for Phase 2b of High Speed 2,[footnote 15] and is looking forward to receiving a business case for Crossrail 2. The government is also investing £5 million in development funding for the Midlands Rail Hub, a programme of rail upgrades in and around central Birmingham that could provide up to 10 additional trains per hour. (9) (36)

4.7 Digital communications

The government will invest over £1 billion by 2020-21, including £740 million through the NPIF, targeted at supporting the market to roll out full-fibre connections and future 5G communications. This will bring faster and more reliable broadband for homes and businesses across the UK, boost the next generation of mobile connectivity and keep the UK in the forefront of the development of the Internet of Things. This will be delivered through:

-

£400 million for a new Digital Infrastructure Investment Fund, at least matched by private finance, to invest in new fibre networks over the next 4 years, helping to boost market ambitions to deploy full-fibre access to millions more premises by 2020

-

a new 100% business rates relief for new full-fibre infrastructure for a 5 year period from 1 April 2017; this is designed to support roll out to more homes and businesses (39)

-

providing funding to local areas to support investment in a much bigger fibre ‘spine’ across the UK, prioritising full-fibre connections for businesses and bringing together public sector demand. The government will work in partnership with local areas to deliver this, and a call for evidence on delivery approaches will be published shortly after the Autumn Statement (10)

-

providing funding for a coordinated programme of integrated fibre and 5G trials, to keep the UK at the forefront of the global 5G revolution; further detail will be set out at Budget 2017 as part of the government’s 5G Strategy (10)

4.8 Energy and flooding

Over the next 15 years, more than £100 billion of private investment is expected in the UK’s energy sector, providing new cleaner generating capacity, upgrading to a smarter energy system, and developing new resources such as shale.

Levy Control Framework – The government is committed to decarbonising the economy while limiting costs on bills, and will continue to engage stakeholders as it develops an emissions reduction plan. The government is considering the future of the Levy Control Framework which it will set out at Budget 2017.

Carbon Price Support – To provide certainty to businesses, the government confirms it is maintaining the cap on Carbon Price Support rates at £18 t/CO2, uprating this with inflation in 2020-21. The government will continue to consider the appropriate mechanism for determining the carbon price in the 2020s.

Shale Wealth Fund – Following a consultation to ensure local communities share in the benefits of shale production, the Shale Wealth Fund will provide up to £1 billion of additional resources to local communities, over and above industry schemes and other sources of government funding. Local communities will benefit first and determine how the money is spent in their area.

Flood defence and resilience – The government will invest £170 million in flood defence and resilience measures. £20 million of this investment will be for new flood defence schemes, £50 million for rail resilience projects, including Dawlish, and £100 million to improve the resilience of roads to flooding.

4.9 Infrastructure financing and delivery

Treasury-backed infrastructure bonds – The Autumn Statement recommits to the UK Guarantees Scheme, and commits to extend it beyond the life of this Parliament, to at least 2026. The UK Guarantees Scheme has to date issued 9 guarantees that have delivered £1.8 billion of Treasury-backed infrastructure bonds and loans, supporting over £4 billion worth of investment.[footnote 16] The government is working with industry to understand the demand for construction-only guarantees.

Private Finance 2 (PF2) – The government will develop a new pipeline of projects that are suitable for delivery through the PF2 Public Private Partnership scheme. A list of projects to make up the initial pipeline, covering both economic and social infrastructure, will be set out in early 2017.

Infrastructure performance – The Chief Secretary to the Treasury will chair a new ministerial group that will oversee the delivery of priority infrastructure projects. The Infrastructure and Projects Authority will lead a review to identify ways government, working with industry, can improve the quality, cost and performance of UK infrastructure. The review will report in summer 2017.

4.10 Research and development

Research and development – Research and development (R&D) is a key driver of economic growth and is a vital part of the government’s Industrial Strategy. To help boost UK productivity the NPIF will provide an additional £4.7 billion by 2020-21 in R&D funding. This extra £2 billion a year by the end of this Parliament is an increase of around 20% to total government R&D spending, and more than any increase in any Parliament since 1979.[footnote 17] Through the NPIF the government will fund:

-

Industrial Strategy Challenge Fund – a new cross-disciplinary fund to support collaborations between business and the UK’s science base, which will set identifiable challenges for UK researchers to tackle. The fund will be managed by Innovate UK and research councils. Modelled on the USA’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency programme the challenge fund will cover a broad range of technologies, to be decided by an evidence-based process (11)

-

Innovation, applied science and research – additional funding will be allocated to increase research capacity and business innovation, to further support the UK’s world-leading research base and to unlock its full potential. Once established, UKRI will award funding on the basis of national excellence and will include a substantial increase in grant funding through Innovate UK (11)

R&D tax environment – To ensure the UK tax system is strongly pro-innovation, the government will review the tax environment for R&D to look at ways to build on the introduction of the ‘above the line’ R&D tax credit to make the UK an even more competitive place to do R&D.

Tech transfer and R&D facilities – In October the government committed an additional £100 million until 2020-21 to extend and enhance the Biomedical Catalyst. These funds will be allocated to Innovate UK. Funding of £100 million will also be provided until 2020-21 to incentivise university collaboration in tech transfer and in working with business, with the devolved administrations receiving funding through the Barnett formula in the usual way. (34)

Science and Innovation Audits – The government has selected 8 areas for the second wave of Science and Innovation Audits: Bioeconomy of the North of England; East of England; Innovation South; Glasgow Economic Leadership; Leeds City Region; Liverpool City Region +; Offshore Energy Consortium; and Oxfordshire Transformative Technologies. The government is also announcing a further opportunity to apply to participate in a third wave of audits.

4.11 Trade

UK Export Finance (UKEF) – The government will provide additional support through UKEF to ensure that no viable UK export should fail for lack of finance or insurance from the private sector, by:

-

doubling its total risk appetite to £5 billion, and increasing capacity for support in individual markets by up to 100%; this will be supported by an improved risk management framework and the use of private insurance markets to reduce Exchequer exposure

-

increasing the number of pre-approved local currencies in which UKEF can offer support from 10 to 40, enabling more overseas buyers of UK exports to pay in their own currency

Supporting trade policy and exiting the EU – Additional resource will be provided to strengthen trade policy capability in the Department for International Trade (DIT) and Foreign and Commonwealth Office, totalling £26 million a year by 2019-20. There will also be additional resource of up to £51 million in 2016-17 for the Department for Exiting the European Union to support the re-negotiation of the UK’s relationship with the European Union. Up to £94 million a year of additional resource will be allocated from 2017-18 until the UK’s exit is complete. In total this will mean up to £412 million of additional funding over the course of this Parliament.

4.12 Enterprise and finance

The government will take a series of actions to ensure businesses have the skills, finance, and stable framework within which to invest.

Patient capital – HM Treasury will lead a review to identify barriers to access to long-term finance for growing firms, supported by an advisory panel led by Sir Damon Buffini. The British Business Bank will also invest an additional £400 million in venture capital funds to unlock up to £1 billion of new investment in innovative firms planning to scale up.

Insurance Linked Securities – The government is consulting on a new regulatory and tax framework for Insurance Linked Securities. Alongside this the Prudential Regulatory Authority and Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) will consult on their approach to the authorisation and supervision of Insurance Special Purpose Vehicles. This will help to maintain London’s position as the most important global hub for reinsurance business. The government will place final regulations before Parliament in the spring.