Country policy and information note: women fearing gender-based violence, Bangladesh, January 2024 (accessible)

Updated 17 June 2025

Executive summary

The status of women in Bangladesh has improved over the past 20 years due to better literacy rates, increased access to formal sector employment and education, and improved access to family planning, reproductive and maternal health care.

However, such progression and improvements are not consistent across the country. Social and cultural norms, alongside prevailing patriarchal attitudes, impose discriminatory and stereotypical roles, rights and responsibilities according to gender.

Women form a particular social group (PSG) in Bangladesh within the meaning of the Refugee Convention because they share a common characteristic that cannot be changed and have a distinct identity which is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) against women and girls, including domestic abuse, rape, dowry-related violence, early and forced marriage, and sexual harassment, is reportedly widespread although sources note underreporting, difficulties with available statistics and the lack of official data. However, in general, women in Bangladesh, including those who fear SGBV, are not at real risk of persecution or serious harm from non-state actors.

The constitution, domestic legislation and policies aimed at protecting women remain largely unimplemented due to gender stereotypes and bias, lack of gender sensitivity on the part of law enforcement officials, lack of human and financial resources, and limited witness protection, corruption and delays in the criminal justice system. Police are reported to view domestic violence as a family matter and there may be impunity for perpetrators with ruling party affiliations.

Support services providing health care, police assistance, social services, legal assistance, psychological counselling and shelter services are available across the country however, the number and capacity of such services are inadequate compared to need.

In general, the state is able but unwilling, to provide effective protection to women who have a well-founded fear of gender-based violence.

Internal relocation may be reasonable in large urban areas, such as Dhaka and Chittagong, although the ability for single women to live alone is likely to be limited.

Assessment

About the assessment

This section considers the evidence relevant to this note – that is information in the country information, refugee/human rights laws and policies, and applicable caselaw – and provides an assessment of whether, in general:

- a person is likely to face a real risk of persecution/serious harm by non-state actors because they are a woman

- a person is able to obtain protection from the state (or quasi state bodies)

- a person is reasonably able to relocate within a country or territory

- a grant of asylum, humanitarian protection or other form of leave is likely, and

- if a claim is refused, it is likely or unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

Decision makers must, however, still consider all claims on an individual basis, taking into account each case’s specific facts.

1. Material facts, credibility and other checks/referrals

1.1 Credibility

1.1.1 For information on assessing credibility, see the instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

1.1.2 Decision makers must also check if there has been a previous application for a UK visa or another form of leave. Asylum applications matched to visas should be investigated prior to the asylum interview (see the Asylum Instruction on Visa Matches, Asylum Claims from UK Visa Applicants).

1.1.3 In cases where there are doubts surrounding a person’s claimed place of origin, decision makers should also consider language analysis testing, where available (see the Asylum Instruction on Language Analysis).

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

1.1.4 The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

1.2 Exclusion

1.2.1 Decision makers must consider whether there are serious reasons for considering whether one (or more) of the exclusion clauses is applicable. Each case must be considered on its individual facts and merits.

1.2.2 If the person is excluded from the Refugee Convention, they will also be excluded from a grant of humanitarian protection (which has a wider range of exclusions than refugee status).

1.2.3 For guidance on exclusion and restricted leave, see the Asylum Instruction on Exclusion under Articles 1F and 33(2) of the Refugee Convention, Humanitarian Protection and the instruction on Restricted Leave.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – Start of section

The information on this page has been removed as it is restricted for internal Home Office use.

Official – sensitive: Not for disclosure – End of section

2. Convention reason(s)

2.1.1 Women form a particular social group (PSG) in Bangladesh within the meaning of the Refugee Convention because they share a common characteristic that cannot be changed and have a distinct identity which is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

2.1.2 In the Country Guidance case SA (Divorced woman- illegitimate child) Bangladesh CG [2011] UKUT 254 (IAC), heard 29 and 30 September 2010 and promulgated 11 July 2011, the Upper Tribunal (UT) held that:

‘… a woman who was able to show that she was at a real risk of domestic violence on return to Bangladesh (to which there was no viable internal relocation alternative) may well be able to demonstrate on the evidence which was adduced before us, that despite the efforts of the government to improve the situation of such women, on account of the disinclination of the police to act upon complaints of domestic violence, she would not be able to obtain an effective measure of state protection by reason of the fact that she was a woman. If so, in these circumstances, the persecution to which she would fear being subjected would be domestic violence against which she would have no protection [because] she was a woman. Therefore she may be able to show a risk of serious harm for a Refugee Convention reason, i.e. membership of a particular social group, namely women in Bangladesh. Each case, however, must be determined on its own facts (paragraph 74).’

2.1.3 Whilst the Constitution of Bangladesh provides for equality of all citizens and numerous legislation has been enacted to protect women’s rights, in practice this is not systematically enforced because of deep-rooted social, cultural and economic barriers and prejudices.

2.1.4 Although women in Bangladesh (continue to) form a PSG, establishing such membership is not sufficient to be recognised as a refugee. The question is whether the particular person will face a real risk of persecution on account of their membership of such a group.

2.1.5 For further guidance on the 5 Refugee Convention grounds see the Asylum Instruction, Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

3. Risk

3.1.1 In general, women in Bangladesh, including those who fear sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), are not at real risk of persecution or serious harm from non-state actors. The onus is on the person to demonstrate otherwise. Decision makers must consider each case on its facts.

3.1.2 Of the nearly 170 million population in Bangladesh, approximately half are female. The status of women has enhanced over the past 20 years due to better literacy rates, increased participation in public and civic spheres, improved access to formal sector employment, education, family planning and reproductive and maternal health care. The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index for 2022 and 2023 ranked Bangladesh highest in the South Asia region in terms of gender parity in economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. Bangladesh has had a woman prime minister for 29 of the past 50 years, though this is not representative of the general position of women in political parties or society (see Social context and Socio-economic rights).

3.1.3 Women’s progression and improvements are not consistent across the country. Women in rural areas are disproportionately affected by poverty, negative social norms and discrimination, and a lack of empowerment in most spheres. Social and cultural norms, alongside prevailing patriarchal attitudes, impose discriminatory and stereotypical roles, rights and responsibilities according to gender. Women are expected to marry and have children, and they may face family and societal pressure to do so. Being single by choice is rare due to a lack of social acceptance and single women may face social stigma due to the expectation of marriage (see Social context).

3.1.4 The constitution, domestic legislation and policies aim to uphold the protection and advancement of women’s rights, both generally and relating to sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). However, the laws relating to SGBV are not always effectively implemented or enforced. Marital rape is not criminalised (see Legal context and Implementation of the law.

3.1.5 SGBV against women and girls, including domestic abuse, rape, dowry- related violence, early and forced marriage, and sexual harassment, is reportedly widespread, although sources note the difficulties with available statistics and the lack of official data. SGBV includes a wide spectrum of behaviour, some of which is not likely to be sufficiently serious by its nature and repetition to reach the high threshold of persecution or serious harm.

3.1.6 The last nationwide government survey on GBV took place in 2015 and found that 72.6% of women had experienced some form of violence by their husbands at least once in their lifetime. A study by the UN Development Programme (UNDP) of GBV trends between May 2018 and April 2021 (covering the coronavirus (COVID 19) pandemic) found rising reports of GBV, particularly in cases of sexual assault, followed by domestic abuse and dowry-related violence. In 2022, 9,764 cases filed under the Suppression of Repression against Women and Children Act (SRWCA) related specifically to violence against women. The actual number of SGBV cases are most likely higher due to underreporting (see Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV)).

3.1.7 Child marriage is prevalent, though according to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2022, women’s and girl’s age at marriage is slowly increasing although early marriage remains more common in rural areas. Early marriage is attributed to a wide range of social and cultural factors, and engrained in religious personal laws (see Early and forced marriage).

3.1.8 In regard to mothers of children born outside of marriage, the UT held in SA:

‘Under Muslim law, as applicable in Bangladesh, the mother, or in her absence her own family members, has the right to custody of an illegitimate child.

‘In custody and contact disputes the decisions of the superior courts in Bangladesh indicate a fairly consistent trend to invoke the principle of the welfare of the child as an overriding factor, permitting departure from the applicable personal law but a mother may be disqualified from custody or contact by established allegations of immorality.

‘The mother of an illegitimate child may face social prejudice and discrimination if her circumstances and the fact of her having had an illegitimate child become known but she is not likely to be at a real risk of serious harm in urban centres by reason of that fact alone’ (paras 110b to 110d).

3.1.9 There has been no material change in circumstances since SA was promulgated and therefore there are not “very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence” to justify departing from it. Social acceptance of single women and single mothers is low and they may face social stigma due to conservative attitudes (see Single women, women heads of households and unmarried mothers).

3.1.10 For further guidance on assessing risk, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

4. Protection

4.1.1 Where the person has a well-founded fear of persecution from non-state actors, including ‘rogue’ state actors, decision makers must assess whether the state can provide effective protection.

4.1.2 In general, the state is able but unwilling, to provide effective protection to women who have a well-founded fear of gender-based violence. Decision makers must consider each case on its facts, with the onus on the person to demonstrate that effective protection is not available.

4.1.3 In SA the UT held that:

‘There is a high level of domestic violence in Bangladesh. Despite the efforts of the government to improve the situation, due to the disinclination of the police to act upon complaints, women subjected to domestic violence may not be able to obtain an effective measure of state protection by reason of the fact that they are women and may be able to show a risk of serious harm for a Refugee Convention reason. Each case, however, must be determined on its own facts (paragraph 110a).’

4.1.4 Since the promulgation of SA, there have been positive developments, including an increase of female police officers, the introduction of women service desks at police stations, and the establishment of 99 Women and Children Repression Prevention Tribunals (for hearing cases of violence against women and children) across 64 districts. However, laws aimed at protecting women continue to remain largely unimplemented due to gender stereotypes and bias, lack of gender sensitivity on the part of law enforcement officials, lack of human and financial resources, and limited witness protection, corruption and delays in the criminal justice system. Police are reported to view domestic violence as a family matter and there may be impunity for perpetrators with ruling party affiliations. The findings in SA continue to apply as there are not “very strong grounds supported by cogent evidence” to justify departing from it (see State protection).

4.1.5 Support services are available across the country through the Multi-Sectoral Programme on Violence Against Women (MSPVAW), under the Ministry of Women and Children Affairs, providing health care, police assistance, social services, legal assistance, psychological counselling and shelter services in one place through One Stop Crisis Centres. However, the number and capacity of services and shelter homes, which often only provide immediate and short term accommodation, are inadequate compared to the need (see Access to support services).

4.1.6 Victims of SGBV often do not report to police due to stigma, victim blaming and shaming, and lack of formal legal redress (see Access to justice). Women without an income or on low wages can find access to justice prohibitive due to the costs of litigation and the distance to travel to courts, which are often outside their home area. A person’s reluctance to seek protection does not mean that effective protection is not available.

4.1.7 For further guidance on assessing state protection, see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status.

5. Internal relocation

5.1.1 Where the person’s fear is of persecution and/or serious harm by non-state, including ‘rogue’ state actors, decision makers must give careful consideration to the relevance and reasonableness of internal relocation taking full account of the individual circumstances of the particular person.

5.1.2 Internal relocation may be reasonable in large urban areas, such as Dhaka and Chittagong, although the ability for single women to live alone is likely to be limited to women to who are financially independent or who have family support. Decision makers must consider each case on its facts (see Single women, women heads of households and unmarried mothers).

5.1.3 In SA the UT held that:

‘The divorced mother of an illegitimate child without family support on return to Bangladesh would be likely to have to endure a significant degree of hardship but she may well be able to obtain employment in the garment trade and obtain some sort of accommodation, albeit of a low standard. Some degree of rudimentary state aid would be available to her and she would be able to enrol her child in a state school. If in need of urgent assistance she would be able to seek temporary accommodation in a woman’s shelter. The conditions which she would have to endure in re- establishing herself in Bangladesh would not as a general matter amount to persecution or a breach of her rights under article 3 of the ECHR. Each case, however, must be decided its own facts having regard to the particular circumstances and disabilities, if any, of the woman and the child concerned. Of course if such a woman were fleeing persecution in her own home area the test for internal relocation would be that of undue harshness and not a breach of her article 3 rights’ (paragraph 110e).

5.1.4 Since SA, shelters for women continue to run though they are limited in number and capacity in comparison to their need (see Access to support services).

5.1.5 For further guidance on considering internal relocation and factors to be taken into account see the Asylum Instruction on Assessing Credibility and Refugee Status and the Country Policy and Information Note on Bangladesh: Internal relocation.

6. Certification

6.1.1 Where a claim is refused, it is unlikely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002.

6.1.2 For further guidance on certification, see Certification of Protection and Human Rights claims under section 94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002 (clearly unfounded claims).

Country information

About the country information

This contains publicly available or disclosable country of origin information (COI) which has been gathered, collated and analysed in line with the research methodology. It provides the evidence base for the assessment.

The structure and content of this section follow a terms of reference which sets out the general and specific topics relevant to the scope of this note.

This document is intended to be comprehensive but not exhaustive. If a particular event, person or organisation is not mentioned this does not mean that the event did or did not take place or that the person or organisation does or does not exist.

Decision makers must use relevant COI as the evidential basis for decisions.

7. Legal context

7.1 Constitution

7.1.1 Article 27 of the Constitution provides for equality of all citizens and states: ‘All citizens are equal before law and are entitled to equal protection of law.’[footnote 1] The Constitution specifically prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex and states ‘Women shall have equal rights with men in all spheres of the State and of public life.’[footnote 2] Equal rights for women in education and employment are also provided for.[footnote 3]

7.2 Domestic legislation and policy

7.2.1 In its concluding observations on the eighth periodic report of Bangladesh, dated November 2016, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) welcomed legislative reforms and efforts to improve institutional and policy framework relating to the protection and advancement of women’s rights.[footnote 4] Despite some positive reforms, in a compilation of UN information to the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), published August 2023, it was noted that the Committee against Torture (UNCAT), the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) and the UN country team had ‘recommended strengthening the enforcement of legislation on sexual and gender-based violence and revising the Penal Code to recognize marital rape as an offence.’[footnote 5]

7.2.2 Domestic laws and provisions upholding the rights of women in Bangladesh, both generally and relating to violence against women specifically, include: the Human Trafficking Deterrence and Suppression Act 2012, the Hindu Marriage Registration Act 2012, the National Women’s Development Policy 2011, the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010, the Citizenship Amendment Act 2009, the Acid Crime Prevention and Acid Crime Control Acts 2002, the Prevention of Women and Children Repression Act 2000, the Suppression of Violence against Women and Children Act 2000[footnote 6], and The Dowry Prohibition Act 2018.[footnote 7]

7.2.3 In February 2000, the Suppression of Repression against Women and Children Act (SRWCA), also known as Prevention of Oppression Against Women and Children Act, came into force. The UN Women Global Database on violence against women (VAW) provided a brief description of the Act:

‘It is intended to address the need for more effective prosecution of perpetrators of violence against women and children than existed previously and provides redress for victims of various manifestations of violence including trafficking and acid throwing. The Act makes provision for compensation for the victim from the guilty person/persons. It also contains provisions for remedial measures for negligence or wilful faults committed by an investigating officer and for a child born as a result of rape to be maintained by the father’.[footnote 8]

7.2.4 In June 2023, UN Women noted the existence of the National Action Plan to Prevent Violence Against Women and Children (2018-2030) and the National Action Plan to Prevent Child Marriage (2018-2030), adding, ‘However, challenges remain in implementing these measures.’[footnote 9]

7.2.5 See also Sexual and gender-based violence and State protection.

7.3 Family laws

7.3.1 The CESCR –– noted in its concluding observations, dated April 2018, that ‘… religious personal laws governing women’s rights in relation to marriage, divorce, maintenance and property inheritance are largely discriminatory against women.’[footnote 10] The USSD HR report 2022 stated that ‘Women do not enjoy the same legal status and rights as men in family, property, and inheritance law. Family and inheritance laws vary by religion.’[footnote 11]

7.3.2 The South Asia Collective, a human rights group, noted in its State of Minorities Report 2022, that ‘Depending on the individuals involved and their religious views, there are modest variations in family laws pertaining to marriage, divorce and adoption. Every religion has its own set of family regulations.’[footnote 12] The same source added ‘The practice of discriminatory personal laws in the name of religion has been demeaning the status of women in the family and other socio-economic institutions. The Government of Bangladesh has been rejecting the demand for a uniform family law for more than three decades.’[footnote 13]

7.3.3 The laws governing marriage and divorce in Bangladesh, which apply to the whole of the country, include:

- for Muslims: the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance (1961), the Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act (1939) and the Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act (1974)

- for Hindus and Buddists: the Hindu Married Women’s Right to Separate Residence and Maintenance Act (1946)

- for Christians: the Christian Marriage Act (1872) and the Divorce Act (1869)[footnote 14]

7.3.4 To put into context the number of adherents potentially affected by family laws, according to the Population and Housing Census 2022, the majority of the population is Muslim (150.4 million or 91.08%), followed by Hindu (13.1 million or 7.96%), Buddhist (1 million or 0.61%), Christian (just under half a million or 0.30%) and others (about 100,000 or 0.06%)[footnote 15]. Around half of the population of each religion were women.[footnote 16]

7.3.5 The South Asia Collective report noted that ‘Marriage ceremonies and procedures are administered by the family law of the two spouses’ respective religions, and marriages are also registered with the state.’[footnote 17] Whilst registration is mandatory for marriages under the Muslim Marriages and Divorces (Registration) Act 1974 and the Christian Marriage Act 1872, failure to register the marriage does not invalidate it.[footnote 18]

7.3.6 For interfaith marriages, the Special Marriage Act 1872 applies. The Government of Bangladesh (GoB) report submitted to the CESCR, dated August 2017, noted:

‘In Bangladesh, marriage between persons professing different religions (interfaith marriage) is permissible in law. The Special Marriage Act, 1872 provides that marriages may be solemnized under this law between persons of different religious faiths. Under the Special Marriage Act, 1872, marriage may be solemnized between persons either of whom may be a Hindu, Sikh, Buddhist or Jain, or a person who does not profess the Christian, Hindu, Muslim, Jewish, Buddhist, Sikh or Jain faiths.’[footnote 19]

7.3.7 The South Asia Collective report highlighted the discriminatory aspects of personal laws:

‘Muslim personal laws are discriminatory in their embrace of polygamy for men, their greater barriers to divorce for women than men and their limited provisions on maintenance. Women have very limited power in terms of exercising guardianship…

‘Hindu personal law further discriminates against women by allowing polygamy for men and placing significant obstacles in the way of women receiving maintenance payments. Hindu women can seek judicial separation, but the law does not recognise divorce, which forces women to live in an unhappy marriage. Moreover, Hindu women in Bangladesh can exercise very limited rights over property…

‘In Christian personal law, divorce is allowed on limited grounds for both men and women, but the stipulations being far more restrictive for women. Men can seek a divorce if they allege their wife committed adultery. Wives, on the other hand, must prove adultery plus other acts to secure a divorce. Such acts include: conversion to another religion, bigamy, rape, sodomy, bestiality, desertion for two years or cruelty.’ [footnote 20]

7.3.8 See also Early and forced marriage.

8. Social context

8.1 Demography

8.1.1 According to the 2022 census, the population of Bangladesh was estimated to be 169,828,911, approximately half of whom (50.45%) were female. The majority of the population (68.34%) live in rural areas.[footnote 21]

8.2 Position of women in society

8.2.1 A report by the World Bank on allowances for widowed, deserted and destitute women in Bangladesh, dated 1 January 2019, noted that:

‘Women’s situation in Bangladesh has progressed through improved literacy; better access to family planning options and reproductive and maternal health care; and enhanced access to education and formal sector jobs among other milestones. However, such empowerment is not uniform throughout the country and multiple challenges still exist. Social norms in Bangladesh continue to prescribe roles, rights and responsibilities according to gender. Patriarchy is prominent as men are deemed to be the breadwinners while women manage the household and raise children.

‘Women, in many cases, have limited role in household decision making, little access to household and individual resources and assets, heavy domestic workload and poor knowledge and skills. Therefore, the majority of women continue to depend on fathers, and husbands following marriage, for decision making and financial and social welfare. As a result, especially when poor women lose their husbands or get divorced, their vulnerability to poverty, exploitation and social isolation increases significantly.’[footnote 22]

8.2.2 In a foreword to the UN Development Programme (UNDP) Bangladesh 2023-2026 Gender Equality Strategy, published in March 2023, Stefan Liller, Resident Representative at UNDP Bangladesh, recognised women’s progress and challenges, noting that:

‘Over the last 20 years, the country has made remarkable progress in improving the lives of women and girls. Women are increasingly involved in public and civic spheres, maternal mortality rates are falling, there is greater gender parity in school enrolment, and women’s groups have mobilized themselves and ensured their voices are heard.

‘Persistent challenges remain, however, which threaten to stall or even reverse much of the progress achieved. Poverty, corruption, discriminatory laws, gender-based violence, child marriage, and climate change are among those challenges disproportionately affecting women and girls.’[footnote 23]

8.2.3 In April 2023 USAID (the US international development agency) also reported on women’s advancement, whilst acknowledging inequalities continued to exist:

‘Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in the last 20 years in improving the lives of women and girls. The maternal mortality rate has decreased by more than two-thirds since 2000 and continues to fall. The fertility rate is declining and there is greater gender parity in school enrollment. Bangladesh has also advanced regulations for protecting women’s rights and privileges, and, due to more women receiving education, progress continues to expand in women’s participation in the labor force.’[footnote 24]

8.2.4 UNDP Bangladesh reported on persistent social norms and gender stereotypes, noting that:

‘Patriarchal values, social norms, and gender-based discriminations permeate all levels of society in Bangladesh, acting as invisible barriers to long-term, comprehensive progress towards gender equality. These norms and values tend to privilege men and boys’ access to opportunities and control over resources. Studies in Bangladesh indicate that participation in income-generating activities positively affected women’s ability to make household decisions such as major purchases, healthcare for themselves and their family members, and engagement in recreational activities.’[footnote 25]

8.2.5 The same source added ‘Women with higher levels of education and income-generating activities are more likely to be involved in decision- making with their partners and are more likely to seek out sexual and reproductive health services than those with lower levels.’[footnote 26]

8.2.6 In an opinion piece in The Daily Star, dated October 2021, Shaheen Anam, executive director of Manusher Jonno Foundation (MJF), ‘one of the largest national grant making organisations in Bangladesh disbursing funds and capacity building support for human rights and governance work within the country’[footnote 27], wrote:

‘While it is well-known that women in all groups across Bangladesh suffer from various forms of abuse and neglect, the women and girls in rural areas suffer disproportionately from poverty, negative social norms and practices, discrimination within households, and a lack of empowerment in most spheres. Research indicates that poverty rates in rural areas across most regions are higher than those in urban areas, impacting women disproportionately.’[footnote 28]

8.2.7 The evaluation report of a project aimed at preventing intimate partner violence (IPV), by international humanitarian organisation CARE (Bangladesh) and its local partner Gram Bikash Kendra (GBK), published in July 2023, citing various sources, noted that:

‘Bangladesh is a conservative, traditional country with gender-related norms, attitudes and practices handed down over generations. Open discussion, equitable decision-making, and joint problem-solving by husbands and wives is not common. Women are socialized to be submissive to men and to obey their decisions, limiting their autonomy and agency. In most homes, women disproportionately assume unpaid labor in the home such as cooking, cleaning and childcare. Women’s lower social status is reinforced and reproduced by low literacy, rural residence, lack of economic independence, abusive in-laws, and disempowering sociocultural practices such as child marriage and dowry, handed down through generations.’[footnote 29]

8.2.8 In the compilation of UN information for the UPR, published August 2023, it was noted that the International Labour Organization (ILO) Committee of Experts asked Bangladesh to ‘… address legal and practical obstacles to women’s employment, including patriarchal attitudes and gender stereotypes, enhance women’s economic empowerment and promote their access to equal opportunities in formal employment and decision-making positions, and encourage girls and women to choose non-traditional fields of study and occupations, while reducing early school dropout among girls.’[footnote 30]

8.2.9 The same report noted that:

‘The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights was concerned that women did not enjoy equality in economic, social and cultural rights. It recommended promoting gender equality in all spheres of life, adopting a unified family law that provided for equal rights for men and women in relation to marriage, divorce, maintenance and property inheritance, raising awareness of gender equality and enhancing free legal assistance to enable women to claim their equal rights.’[footnote 31]

8.2.10 For further information relating to the position of women, see Socio-economic rights.

8.3 Single women, women heads of households and unmarried mothers

8.3.1 A representative from Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK), a national legal aid and human rights organisation, consulted during the Home Office FFM to Bangladesh in May 2017, stated in regard to single women:

‘There are big problems with the social acceptance of single women, even for educated women who are working. There are also financial constraints. To live without male support is almost impossible. Bangladesh is a very family-orientated society. Even educated women are afraid to leave their families… It is difficult for single women to rent a place to live in Dhaka or anywhere since society does not accept this and the state fails to assure security. It turns out to be a great obstacle towards single potential women’s empowerment. Single childless women may be able to find work in someone else’s home (as a domestic worker), but a woman with children would find such work difficult to obtain. […] Single woman living alone are often called Bhabi which means “sister-in-law”. It is for their protection and also suggests they are unfamiliar with or unaccustomed to being with a single woman.’[footnote 32]

8.3.2 The representative from the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) told the Home Office FFM that:

‘It would not be easy for a young single woman to relocate or live alone without a good family support base. It would not be usual or seen as normal for a woman to live alone. Some professional affluent women might be able to do this but would still face harassment – even older single women. Renting a property alone would be difficult. Employment would be accessible to single women but mostly available to those from middle classes with access to family support. Single women from poor backgrounds would be destitute. Marriage is seen as the main source of social acceptance.’ [footnote 33]

8.3.3 According to Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) country information report, dated November 2022, based on DFAT’s on-the- ground knowledge and discussions with a range of sources in Bangladesh, and taking account of other government and non-government sources[footnote 34]:

‘Single women are likely to encounter social and economic difficulties. It is possible for a woman to be head of a household in the event her husband has died or left her (such households exist in practice, both in urban and rural areas) but the ability to do so successfully would depend on a woman’s capacity to support herself financially.

‘Sources told DFAT that women who are heads of households would not face discrimination in employment or health care, for example, but securing sufficient work and childcare would nonetheless be difficult. Being single by choice is virtually unheard of due to social stigma related to being a single woman. Remarriage is often considered socially unacceptable, for both widows and divorcees due to conservative societal attitudes toward marriage. Most women are married very young, including as children, and face significant family and societal pressure to get married.’[footnote 35]

8.3.4 According to a 2022 BBS report, which referred to 2020 figures, 25.4% of women over the age of 10 were single, compared to 38.3% of men.[footnote 36] The same source noted that ‘The drop in the proportion of being single is steeper among women than among men as age advances. 100 percent of the men are single in age group 10–14, this drop [sic] to 96.3 percent when they are aged 15–19, and further to about 73.5 percent when they reach to 20–24. The corresponding proportions among the women are 95.6, 76.8 and 28 percent.’[footnote 37] The data indicated that less than 10% of women were single in the age group 25 to 29, and less than 5% were single in the age group 30 to 34.[footnote 38] Figures in the 2022 census continued to indicate that women were more likely to be married than men, married younger than men, and that marriage status was similar in both rural or urban areas.[footnote 39]

8.3.5 According to research on 156 single mothers in Dhaka, undertaken in 2016/2017, 44.2% of them were raising their children alone due to the death of their husbands, 34.60% were divorced, and 21.20% separated due to their husband’s extramarital affairs, second marriages, and physical abuse. Among these single mothers, 44.3% were employed[footnote 40]. Citing the same survey, the Dhaka Tribune wrote in May 2023 that ‘ … the concept of single motherhood is still not widely understood or accepted in society.’[footnote 41]

8.3.6 According to data compiled from World Bank surveys, 87.1% of Dhaka households (in 2018), and 84.2% of Chittagong households (in 2019) were headed by men.[footnote 42]

8.3.7 A response on the treatment of women by authorities and society, including single women and heads of households, by the Research Directorate of the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB), which was ‘prepared after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the Research Directorate within time constraints’, dated 5 January 2023, noted:

‘An article by Inaya Zaman, published on the blog of the James P. Grant School of Public Health (JPGSPH) at BRAC University [a university in Dhaka “with very close links” to the BRAC NGO (BRAC University n.d.)], reports that the “growing” prevalence of single working women in Bangladesh has resulted in “a heavy increase in internal migration by young women to Dhaka city” (Zaman 2020-02-04).

‘Zaman writes that landlords and other tenants “usually” refuse to rent dwellings to single women, instead “requiring them to be married,” or otherwise only have access to dwellings with the “poorest facilities at incredibly high prices” (2020-02-04). A short documentary on single working women in Dhaka, produced and based on research by BRAC JPGSPH, interviews a women [sic] who, with a female friend, entered into a joint rental lease for an apartment when the landlord stopped responding to their calls in the five days before the start of the lease; the woman reported that the landlord later explained that the residents of the building did not agreed [sic] to let them rent the apartment because they were unmarried (BRAC University 2019-03-31, 3:15-3:25). Similarly, the Associate Professor [North South University in Dhaka] indicated that single women have “difficult[y]” accessing housing in Dhaka and Chittagong “if they are not married or do not have a family” (2022-12-07).’[footnote 43]

8.3.8 During the Home Office FFM in May 2017, Mohammed Asaduzzaman Sayem of the UK Bangladesh Education Trust (UKBET) told the delegation that it was ‘extremely rare’ for women to have children outside of marriage.[footnote 44] The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) informed the FFM team that although sex before marriage was not illegal, it was particularly frowned upon for women and to have a child outside of marriage would be unacceptable to family and society.[footnote 45]

8.3.9 A 2020 opinion peace on abortion rights in Bangladesh by Tasnia Ahmed and Nujhat Jahan Khan, both part of She Decides (Bangladesh), a global movement fighting for bodily autonomy[footnote 46], noted that ‘Unmarried young Bangladeshi women becoming pregnant face multiple challenges from the outset. They will be shamed for being sexually active, for their decision to keep the pregnancy, or for the decision to terminate the pregnancy.’[footnote 47]

8.3.10 In January 2023, the High Court ruled that it was no longer mandatory for a father’s name to be cited in forms for educational institutions, and that the mother’s name alone (or any other legal guardian) was sufficient. The ruling followed a petition filed in 2009 after a regional education board prevented a student from sitting for high school exams because her father’s name was not listed on an information form[footnote 48] [footnote 49]. It was not clear if this ruling applied to other official documents.

8.3.11 For general information on access to housing, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Bangladesh: Internal relocation.

8.4 Lesbians and bisexual women

8.4.1 See the Country Policy and Information Note on Bangladesh: Sexual orientation and gender identity or expression.

9. Socio-economic rights

9.1 Global equality / inclusivity ranking

9.1.1 In terms of gender equality, the UN Development Programme (UNDP) Gender Inequality Index (GII), measures gender-based disadvantage in terms of reproductive health, empowerment and the labour market. The GII ranges from 0, where women and men fare equally, to 1, where one gender fares as poorly as possible in all measured dimensions, showed Bangladesh’s progress since 1990 (when it measured 0.730), up to 2021 (0.530), bringing the country closer to the world average of 0.465.[footnote 50]

9.1.2 The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Global Gender Gap Index, which measures parity between men and women in economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment[footnote 51], gave Bangladesh a score of 0.722 (imparity = 0, parity = 1), and ranked Bangladesh 59 out of 146 countries in 2023 [footnote 52] (one being the narrowest gender gap and 146 the widest[footnote 53]), an increase of 12 points since 2022[footnote 54]. In both 2022 and 2023, Bangladesh ranked first out of the 9 countries in the South Asia region[footnote 55] [footnote 56]. The Index noted that Bangladesh’s trajectory in 2023 was ‘mostly characterized by continuous progress on Political Empowerment.’[footnote 57] See also Political participation and representation.

9.1.3 The Georgetown Institute’s 2023/2024 Women, Peace and Security Index (GIWPS), which measures women’s status in terms of: inclusion (economic, social, political), justice (formal and informal discrimination), and security (at the individual, community, and societal levels), ranked Bangladesh 131 out of 177 countries and scored it 0.593 (where one demonstrates the highest levels of inclusion, justice and security for women and 0 the least). [footnote 58]

9.2 Education and literacy

9.2.1 The USSD HR Report 2022 explained ‘Education is free and compulsory through eighth grade by law, and the government offered subsidies to parents to keep girls in class through 10th grade.’ But added ‘Teacher fees, books, and uniforms remained prohibitively costly for many families, despite free classes, and the government distributed hundreds of millions of free textbooks to increase access to education. Enrollments in primary schools showed gender parity, but completion rates fell in secondary school, with more boys than girls completing that level. Early and forced marriage was a factor in girls’ attrition from secondary school.’[footnote 59]

9.2.2 According to a survey by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), the functional literacy rate of women aged 11 to 45 years was 73.25% in 2023 (up from 50.20% in 2011), compared to 74.10% of men[footnote 60]. According to the Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics (BANEIS), as of 2021, 97.44% of girls were enrolled in primary school[footnote 61], and nearly half (49.54%) of all primary school students were girls.[footnote 62] As of 2022, over half (54.69%) of the number of students enrolled in secondary school were girls[footnote 63], and girls made up 50.27% of students enrolled in higher education.[footnote 64]

9.2.3 According to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2022, conducted under the National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT), Medical Education and Family Welfare Division, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, ‘Almost 60% of women have at least some secondary education, and 24% have a secondary education or higher.’[footnote 65]

9.3 Employment and income

9.3.1 The IRB response, published in January 2023, noted that:

‘According to a 2019 figure provided by the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the unemployment rate among women in Bangladesh is 6.6 percent, compared to 3.2 percent for men (2021-04, 3). A modelled estimate and projection by the International Labour Organization (ILO)… published in November 2022 provides the following unemployment rate by sex for Bangladesh:

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female age 15 and over | 7.5% | 7.5% | 7.1% |

| Male age 15 and over | 4.1% | 3.9% | 3.5% |

‘The ADB indicates that 6.2 percent of women employed in 2019 were paid a wage equivalent in their local currency to a purchasing power “below [US]$1.90” per day, compared to 5.3 percent of men (2021-04, 2).’[footnote 66]

9.3.2 The USSD HR Report 2022 stated that labour law in Bangladesh prohibits wage discrimination on the basis of ‘sex or disability’, but does not prohibit other types of discrimination on that basis[footnote 67]. The same source noted that the ‘law does not include a penalty for discrimination’ and that it was not ‘effectively enforce[d].’[footnote 68]

9.3.3 Referring to the informal employment sector, the IRB response noted:

‘Citing the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) labour force survey for 2015-2016, the UN Entity for Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women (UN Women) indicates that 95.4 percent of women are part of the “informal” employment sector, as either wage earners, self-employed persons, unpaid family labourers, or other hired labourers (UN n.d.a). According to a study by Sharmind Neelormi, associate professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University in Dhaka (The Daily Star 2021-04-25), which was conducted from November to December 2020 with interviewees from nine urban and rural districts, 87 percent of whom were women, and 47 percent of whom were homemakers, 96.7 percent of employed women are “engaged in” the informal sector (Neelormi [2021-04], 17).’[footnote 69]

9.3.4 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted that the informal sector was not covered by labour laws, adding that ‘In both urban and rural areas, women and youth were more likely to be in informal employment. Nearly half the workers in the informal sector had received no schooling.’[footnote 70]

9.3.5 According to provisional figures in the BBS labour force survey for 2022, female labour force participation (FLFP) rate in Bangladesh increased to 42.67%, compared to 36.3% in 2016/17[footnote 71]. The same survey noted that male labour force participation rate stood at 79.71% in 2022.[footnote 72] By comparison, the UK’s FLFP was 75.2% in 2021/2022.[footnote 73]

9.3.6 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted that ‘Women made up more than 50 percent of the total workforce in the garment industry according to official statistics. Even in the garment sector, however, women faced discrimination in employment and occupation. Women were generally underrepresented in supervisory and management positions and generally earned less than male counterparts even when performing similar functions.’[footnote 74]

9.3.7 In April 2023, USAID noted the expansion of women’s participation in the labour force over the past 2 decades, though added, ‘This workforce participation, however, remains constrained to limited, low-paying sectors. Three million women are employed in the lucrative ready-made garment sector, Bangladesh’s largest export industry. Increasing numbers of women are involved in small and medium enterprises, but there remain large finance gaps that women face despite government initiatives.’[footnote 75]

9.3.8 UNDP Bangladesh noted in its March 2023 report that:

‘Microfinance has had a tremendously empowering effect on women: 92 per cent of borrowers are women, increasing their economic independence, social inclusion, and political participation. Nevertheless, systemic barriers continue to prevent women’s economic empowerment: women account for only 5 per cent of Bangladesh’s businesses are owned by women, and only 25 per cent of women have an account at a formal financial institution.

‘Furthermore, regardless of whether they are employed, they continue to take on the majority of unpaid domestic care work. Women are also disproportionately affected by unemployment, underemployment, and vulnerable employment.’[footnote 76]

9.3.9 The IRB response referred to social welfare, noting that:

‘According to the Ministry of Social Welfare’s website for the Allowances for the Widow, Deserted and Destitute Women social protection program, the government provides a cash transfer of 300 Bangladesh Taka (BDT) [c.£2.20[footnote 77]] per month, paid quarterly, to 1.15 [million] Bangladeshi women beneficiaries (according to 2016–2017 figures) who are either widowed, divorced, whose husbands have “deserted” them, or who are “wealthless/homeless/landless” (Bangladesh n.d.a). Data compiled from a 2018 World Bank survey for Dhaka and a 2019 World Bank survey for Chittagong, indicates that 1.4% of households in Dhaka received “money from social safety-net” programs, and 1.5 percent did so in Chittagong.’[footnote 78]

9.4 Political participation and representation

9.4.1 The WEF Global Gender Gap Index for 2023 noted in regard to political empowerment that ‘At 55.2% parity, Bangladesh ranks seventh globally on this subindex. It has had a woman head of state for 29.3 years out of the last 50 years, the longest duration in the world. However, its shares of women in ministerial (10%) and parliamentary positions (20.9%) are relatively low.’[footnote 79]

9.4.2 The USSD HR Report 2022 stated that:

‘No laws limited participation of women or members of minorities in the political process, and they did participate. In 2018, parliament amended the constitution to extend by 25 additional years a provision that reserves 50 seats for women. Female parliamentarians are nominated by the 300 directly elected parliamentarians. The seats reserved for women are distributed among parties proportionate to their parliamentary representation. Political parties failed to meet a parliamentary rule that women comprise 33 percent of all committee members by the end of the 2020, leading the Electoral Commission to propose eliminating the rule altogether.’[footnote 80]

9.4.3 Freedom House noted in its annual report covering 2022 events that ‘In the National Parliament, 50 seats are allotted to women, who are elected by political parties based on their overall share of elected seats. Women lead both main political parties. Nevertheless, societal discrimination limits female participation in politics in practice. Men are likelier to be selected as candidates, while women are often relegated to serving in women’s wings of their parties; women also face social pressure to refrain from political activity.’[footnote 81]

9.4.4 UNDP Bangladesh reported in March 2023 that:

‘The [50 reserved] seats are allotted to the parties based on their proportional representation in parliament, but they are not elected and have no constituency. Women’s political participation has thus not yet reached a satisfactory level, both at the national and local levels. Persistent gendered social norms and stereotypes, as well as early marriage and familial duties, act as barriers to women’s rise to political leadership in Bangladesh. Increasing women’s participation in the political sphere requires a whole-of- society approach that dismantles these barriers effectively.’[footnote 82]

9.5 Healthcare and reproductive rights

9.5.1 The USSD HR Report 2022, regarding reproductive rights for women, noted:

‘There were no reports of coerced abortion or involuntary sterilization on the part of government authorities. A full range of contraceptive methods, including long-acting reversible contraception and permanent methods, were available through government, NGO, and for-profit clinics and hospitals.

Low-income families were more likely to rely on public family planning services offered free of cost. Religious beliefs and traditional family roles served as barriers to access. Government district hospitals had crisis management centers providing contraceptive care to survivors of sexual assault. Due to cultural and religious factors, many women were unable to access contraception without their husbands’ permission.’[footnote 83]

9.5.2 According to the DHS 2022, 55% of currently married women aged 15 to 49 used ‘modern methods of contraception.’[footnote 84]

9.5.3 Maternal mortality rate has decreased from 441 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to an estimated 123 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020.[footnote 85] The DHS 2022 found that 88% of women who had given birth in the 2 years preceding the survey had received anti-natal care (ANC) at least once during their pregnancy from a ‘medically trained provider’, 70% of deliveries were attended by a ‘medically trained provider’, and 55% of women received post- natal care within 2 days of delivery.[footnote 86]

9.5.4 Termination of a pregnancy, defined in the Penal Code as ‘causing miscarriage’, is a criminal offence, unless done ‘in good faith’ to save the life of the woman.[footnote 87] However, the government’s policy on birth control allows for menstrual regulation (MR) procedures up to 12 weeks and menstrual regulation with medication (MRM) up to 9 weeks.[footnote 88] [footnote 89] Marie Stopes Bangladesh, a provider of sexual and reproductive health services in partnership with the government’s National Family Planning Programme[footnote 90], offered both surgical MR[footnote 91] and MRM.[footnote 92]

9.5.5 For information on the healthcare system in general, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Bangladesh: Medical treatment and healthcare.

10. Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV)

10.1 Overview of data on SGBV

10.1.1 The UN Development Programme (UNDP) Bangladesh, Research Facility, together with UNDP’s ‘Partnerships for a Tolerant and Inclusive Bangladesh’ (PTIB) project (UNDP study), provided an insight on GBV (gender-based violence) data by analysing information from the period May 2018 to April 2021, drawn from the Bangladesh Peace Observatory (BPO) database – an initiative of PTIB.[footnote 93] The BPO’s online database ‘contains verified open- source data on violence since 2014, based on selected Bangla and English print and online media reports.’[footnote 94] The UNDP study stated in regard to GBV data that ‘Available statistics are often fragmented, typically provide snapshots of the situation or can be inaccessible, making it difficult to gauge meaningful trends over time.’[footnote 95] The same source noted that ‘… it is difficult to gauge GBV’s true extent especially in hard-to-reach areas using only the BPO database.’[footnote 96] According to USAID, ‘Gender-based violence remains a prevalent issue that inhibits rural communities in particular from participating in inclusive growth.’[footnote 97]

10.1.2 Amnesty International wrote in its annual report covering 2022 events that ‘… a culture of impunity persisted for gender-based violence and the lack of official data on violence against women and girls made it difficult to assess the true extent of its prevalence.’[footnote 98]

10.1.3 The last nationwide government survey on GBV took place in 2015 and found that 72.6% of ever-married women (aged 15 and over) had experienced some form of violence by their husbands at least once in their lifetime.[footnote 99] As a worldwide comparison, 2018 global estimates by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that 26% of women aged over 15 had experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence at least once in their life.[footnote 100]

10.1.4 According to the WEF Global Gender Gap Index 2023, the prevalence of gender violence in the lifetime of women in Bangladesh was estimated at 53.3%.[footnote 101] As regional comparisons, the same source noted that prevalence for India was 28.7%, and 85% for Pakistan.[footnote 102]

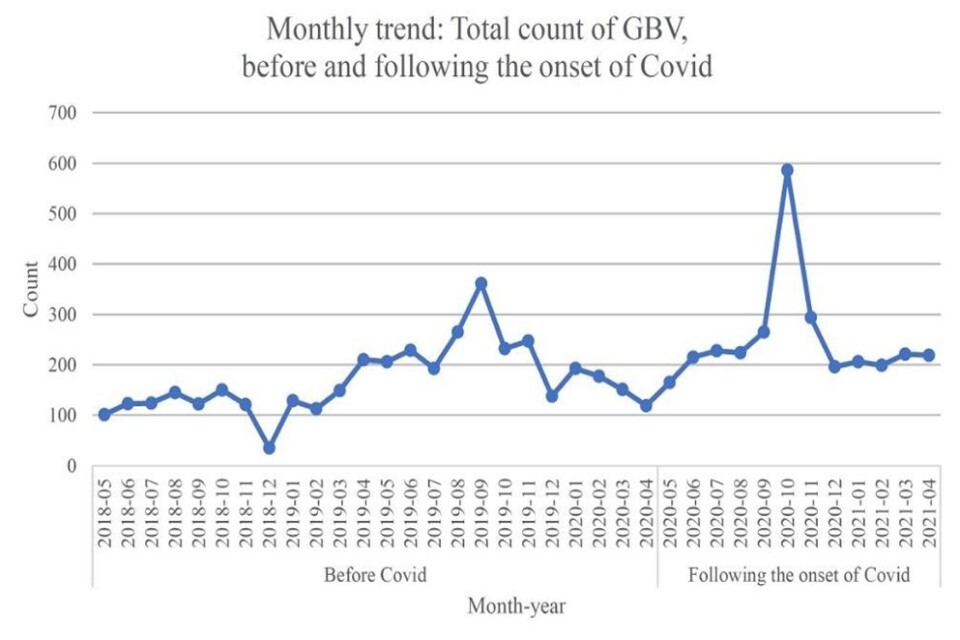

10.1.5 The UNDP study’s data on GBV, which aimed to ‘understand trends prior to and covering the [coronavirus – COVID 19] pandemic’, found ‘… an increasing trend in reported GBV incidents since May 2018… It tends to peak around September or October annually. This may be tied to the annual lean season in rural Bangladesh that can induce stress linked to poverty and with it, violence. Overall, the violence further spiked with the onset of the COVID pandemic in March 2020 – as documented by many studies.’[footnote 103]

10.1.6 The UNDP study[footnote 104] indicated that GBV trends have been rising since 2018:

Monthly trend: total count of GBV before and following the onset of COVID-19.

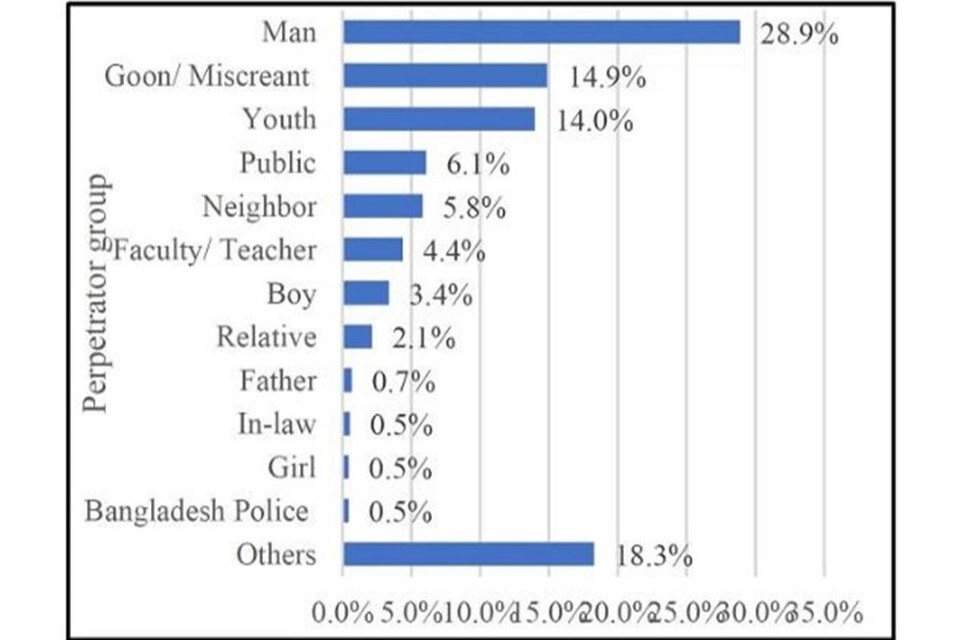

10.1.7 The UNDP study reported that ‘Women and girls are the biggest victims of GBV. Girls, including children, faced 60% of sexual assaults in 2020-21 alone. When we aggregate women, girls, and children, they account for 88.2% of GBV cases. Men make up most of the perpetrators.’[footnote 105]

10.1.8 The UNDP recorded[footnote 106] the main perpetrators of GBV:

UNDP main perpetrators of GBV.

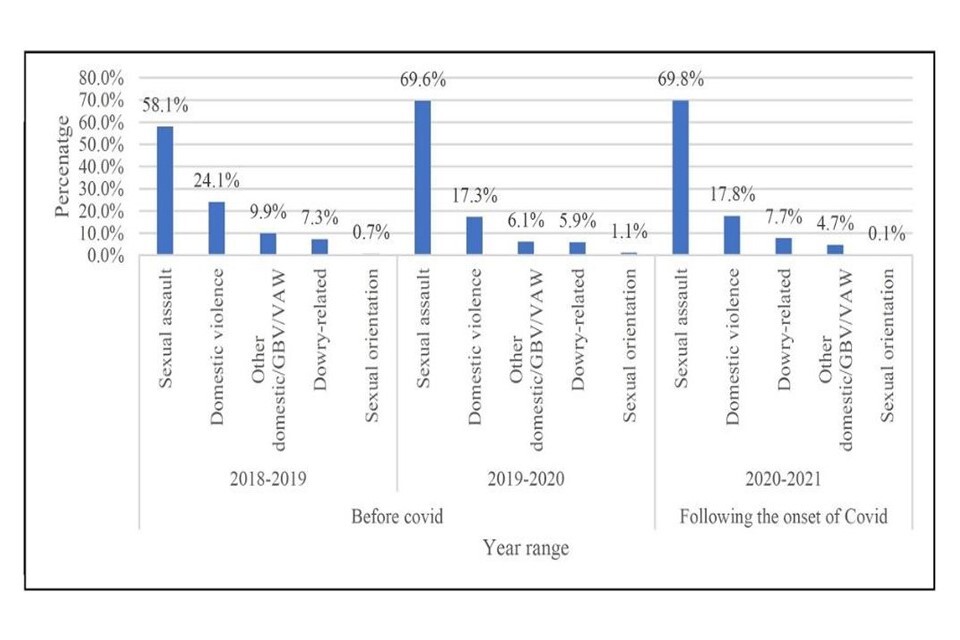

10.1.9 The UNDP study recorded annual trends in types of GBV reported before and following the COVID-19 onset, noting that ‘Sexual assault is the most reported source of violence over time, accounting for at least 3 in 5 reported incidents. Domestic violence trails second: it had dipped before COVID’s onset but seems to have risen with the crisis. Similarly, reported dowry-related incidents also showed a downward trend in recent years before picking up with the pandemic.’[footnote 107][footnote 108]

Annual trends in types of GBV reported before and following the COVID-19 onset.

10.1.10 According to police headquarters data, 99,638 cases had been filed under the SRWCA between 2018 and 2022 (up to October[footnote 109]):

| Year | Number of cases filed |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 16,234 |

| 2019 | 21,752 |

| 2020 | 22,501 |

| 2021 | 22,124 |

| 2022 (till October) | 17,027 |

10.1.11 Of the cases filed in 2022 (till October), 9,764 related specifically to cases of VAW.[footnote 110]

10.1.12 National human rights NGO, Odhikar, noted in its annual human rights report covering 2022, which was based on data collection, reports sent by human rights defenders and information published in various media[footnote 111], that ‘Due to lack of accountability and impunity, women have been subjected to various forms of oppression and violence, including rape by ruling party activists and members of law enforcement agencies. Moreover, gender discrimination in various fields, including education, and the health sector, and in the legal framework, has increased violence against women.’[footnote 112]

10.1.13 Concluding her visit to Bangladesh, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Michelle Bachelet, stated in August 2022 that ‘Violence against women, including sexual violence, remains high…’[footnote 113] The compilation of UN information for the UPR, published August 2023, repeated the High Commissioner’s concerns, and also noted the UNCAT’s and CESCR’s concerns about all forms of SGBV in Bangladesh, ‘including domestic violence, rape and sexual harassment.’[footnote 114]

10.1.14 In June 2023, UN Women observed that, despite national action plans in place to prevent violence against women and girls and to prevent child marriage, ‘Women have limited access to affordable, essential, and adequate redressal services. Simultaneously, the social stigma attached to survivors of violence, restrictive social norms, and behaviours that normalize violence, all hinder women, girls, and sexual minorities from enjoying their human rights and fully participating in public and private life.’[footnote 115]

10.1.15 See also State protection.

10.2 Domestic violence

10.2.1 A Human Rights Watch (HRW) report on violence against women and girls, published October 2020, stated that the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act of 2010 (DVPP Act 2010) was ‘… an important step forward in broadening the definition of domestic violence against women and children to include physical, psychological, sexual, and economic abuse.’[footnote 116]

10.2.2 A report on the DVPP Act 2010, published in June 2023 by Maheen Sultan and Pragyna Mahpara from the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), Bangladesh, noted that ‘In Bangladesh, dominant social norms have led to stereotyping domestic violence as a trivial, personal matter, which has led to service providers delegitimising and deprioritising the issue. Combined with all the gender biases that operate within the judiciary and other government departments, this has resulted in an unsatisfactory use of the [DVPP] Act for women seeking redress from violence.’[footnote 117]

10.2.3 The same report noted that ‘Marriage is seen as the norm, emphasis is put on the restitution of marriage and therefore women are expected to live with violence and abuse in order to save their marriage.’[footnote 118] See also State protection.

10.2.4 Legal aid and human rights organisation, Ain o Salish Kendra (ASK) reported that 224 women were murdered by their husbands in 2021[footnote 119], and 206 women were murdered by their husbands in 2022 (based on media reports and its own data)[footnote 120]. According to the same source and data collection methods, 170 women were murdered by their husbands between January and September 2023.[footnote 121]

10.2.5 The NGO, Human Rights Support Society (HRSS), also recorded data on domestic violence (described as ‘family feud’) in its 2022 annual human rights report. Based on data collected from prominent national dailies and the HRSS investigation unit, the HRSS noted the deaths of 224 women, 83 injuries and 65 suicides related to domestic violence in 2022.[footnote 122]

10.2.6 The DFAT report of November 2022 stated that ‘Although less common than in the past, acid attacks against women in the name of “family honour” remain a problem… Most acid attacks are reportedly related to marital, family, land, property or money disputes, or to a woman’s refusal to accept a marriage proposal.’[footnote 123]

10.2.7 The HRSS report provided information about acid attacks, noting that:

‘… Bangladesh has a long history of acid violence, with women being the primary victims. The year 2022 was no exception, as acid attacks continued to occur, highlighting the urgent need for action to prevent this devastating crime. The roots of acid violence in Bangladesh can be traced back to socio- cultural factors such as gender inequality, lack of education, and patriarchal attitudes. Acid attacks have been used as a weapon of revenge, control, and punishment against women who refuse proposals of marriage, demand divorce, or seek independence. Despite efforts to curb this practice, acid violence remains a significant problem in Bangladesh.

‘The situation regarding acid violence in Bangladesh is concerning. Despite the existence of laws criminalizing acid attacks and regulating the sale and use of acid, the perpetrators often go unpunished due to weak law enforcement and a culture of impunity.’[footnote 124]

10.2.8 The Human Rights Watch report published in 2020 noted that:

‘Over the last 20 years, according to ASF [Acid Survivors Foundation], there have been over 3,800 reported cases of acid violence in Bangladesh, with the vast majority of attacks perpetrated by men targeting women or girls who they know. Inextricable from gender inequality, acid attacks often occur within a pattern of ongoing domestic violence, in response to rejection of sexual advances or a marriage proposal, as a punishment for seeking education or work, or as a form of retribution in land or dowry disputes.’[footnote 125]

10.2.9 The same report noted that:

‘Existing government facilities for burn treatment are overburdened and primarily centered in Dhaka, the capital city, and thus largely inaccessibly to rural populations. All of the survivors interviewed for this report expressed suffering severe pain… Acid violence is rarely directly fatal. Rather, victims live on with physical, emotional, economic, and social suffering. Victims are often left with severe and permanent disabilities and may depend on family members for ongoing care, sometimes for the rest of their lives. Despite this, some women said that after they were attacked, their families or husbands abandoned them… Disability resulting from an acid attack can severely impact a woman’s ability to perform physical work that she previously may have been able to do, thus cutting off an important component to financial independence. Acid attack survivors in Bangladesh also face cultural stigma that exacerbates the discrimination they face as people with disabilities. For instance, Shammi explained that she could no longer find work because, she said, “socially, people are afraid to see me.”’[footnote 126]

10.2.10 The USSD HR report 2022 noted that ‘Assailants threw acid in the faces of survivors, usually women, leaving them disfigured and often blind. Acid attacks were frequently related to a woman’s refusal to accept a marriage proposal or were related to land or other money disputes. A total of 13 acid attacks were reported.’[footnote 127]

10.3 Dowry-related violence

10.3.1 The HRSS human rights report for 2022 briefly described the practice of dowry, which is prohibited by law under The Dowry Prohibition Act 2018, and the reasons behind dowry-related violence, despite its criminalisation:

‘Dowry-Related Violence is a common form of violence against women in Bangladesh, which has been prevalent for centuries. It is a crime that often leads to physical, psychological, and emotional harm to women, and sometimes even to death. Unfortunately, the year 2022 was no exception, as it continued to be a serious problem in Bangladesh. The historical context of Dowry-Related Violence in Bangladesh can be traced back to the socio- cultural practices that encourage or enforce the exchange of dowries during marriage. The practice of dowry is deeply ingrained in the society and is considered a part of tradition and culture. However, this has led to a situation where the bride’s family is expected to provide a substantial amount of money or property to the groom’s family as part of the marriage contract.

When the bride’s family is unable to fulfill these demands, they often face threats and violence’.[footnote 128]

10.3.2 Prothom Alo, a Bangladeshi daily newspaper and website, cited data from police headquarters from January to October 2022, which recorded 2,675 women were physically abused due to dowry related issues, and 155 women were killed for not fulfilling dowry demands.[footnote 129]

10.3.3 In 2022, the HRSS recorded 159 incidents of dowry-related violence, resulting in around 70 deaths, 7 suicides and the physical abuse of 82 women over dowry demand[footnote 130]. HRSS reported 42 deaths, 4 suicides and 113 cases of physical abuse related to dowry in 2021[footnote 131]. ASK recorded in 2022 the deaths of 79 women and 75 physical assaults in dowry-related violence[footnote 132], compared to 72 deaths and 111 physical assaults in 2021.[footnote 133]

10.4 Rape

10.4.1 Section 375 of the Penal Code defines ‘rape’ as sexual intercourse taking place without the will or consent of, or by obtaining consent with false promises, with any women under the age of 14. Marital rape is not criminalised providing the wife is aged over 13 years.[footnote 134]

10.4.2 The SRWCA 2000 provided a different definition of rape, as noted in a joint report by the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) and the Philippine Alliance for Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA), published in May 2021, based on a range of sources, which stated that ‘The law, originally in Bangla, can be translated to: “If a man has sexual intercourse with a woman (under or over the age of sixteen), outside of marriage, with or without her consent, and, if consent was given, it was under threat or connivance, then he is said to have committed the offense of rape”.’[footnote 135]

10.4.3 The same source noted that ‘Although the age has been changed to 16 from 14, for all purposes, the conditions of rape contained in the Penal Code are followed. Both the definitions rely on proof of resistance by the victim.’[footnote 136]

10.4.4 HRW reported in November 2020 that ‘The current legal definition of rape in Bangladesh specifically excludes rape within marriage and defines as rape only acts by a man against a woman, excluding men, boys, and transgender, hijra, or intersex people from protection. There is no definition of penetration under the law, meaning that cases of rape that include the insertion of objects or other parts of the rapist’s body are more likely to lead to acquittal.’[footnote 137]

10.4.5 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted that ‘Conviction of rape is punishable by life imprisonment or the death penalty. Human rights organizations found rape remained a serious issue in the country… There were allegations of rapists blackmailing survivors by threatening to release the video of the rape on social media.’[footnote 138]

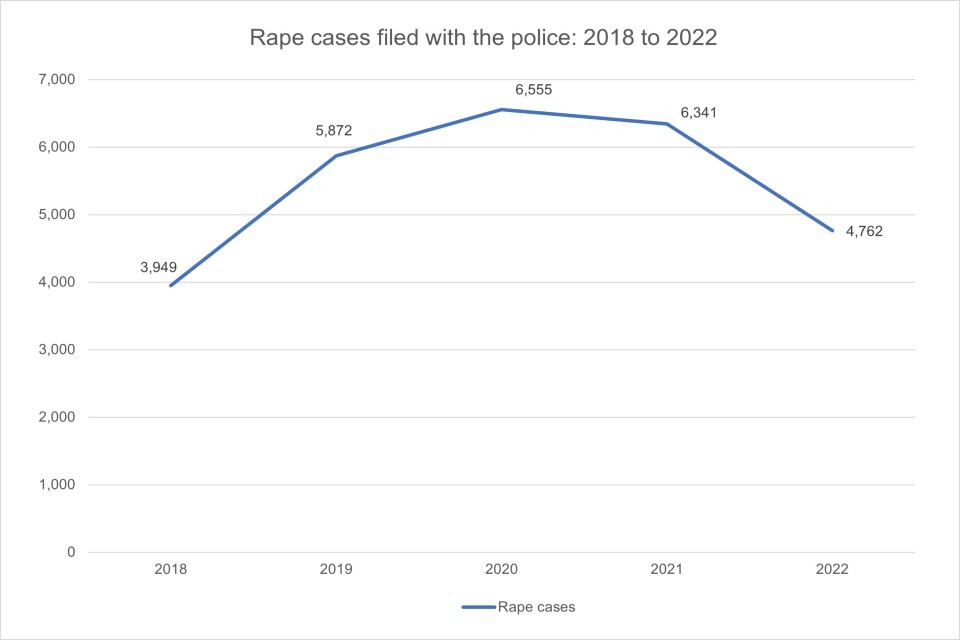

10.4.6 Bengali newspaper, Kaler Kantho, reported in February 2023 that, according to police statistics, 27,479 rape cases were filed between 2018 and 2022: 3,949 cases in 2018, 5,872 cases in 2019, 6,555 cases in 2020, 6,341 cases in 2021, and 4,762 cases in 2022.[footnote 139]

Graph produced by CPIT.

10.4.7 The actual number of rape incidents is most likely higher than the number of cases filed, due to underreporting.[footnote 140] [footnote 141]

10.4.8 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted that ‘According to human rights monitors, many survivors did not report rapes due to lack of access to legal services, social stigma, fear of further harassment, and the legal requirement to produce witnesses. The burden is on the rape survivor to prove a rape occurred, using medical evidence.’[footnote 142]

10. 5 Early and forced marriage

10.5.1 The USSD HR Report 2022 noted that, ‘The legal age of marriage is 18 for women and 21 for men. The law includes a provision for marriages of women and men at any age in “special circumstances.”’[footnote 143] A child marriage under the undefined ‘special circumstances’ of the Child Marriage Restraint Act 2017 should be in the ‘best interest of the child’, at the direction of a court, and with the consent of the parents or guardian.[footnote 144] The consent of the child is not required.[footnote 145]

10.5.2 The DHS 2022 found that age at marriage was slowly increasing, and that early marriage was more common in rural areas.[footnote 146] In 2022, 50% of women aged 20 to 24 married before age 18, compared to 65% in 2011, and just under 27% of women married before age 16 in 2022, compared to 43% in 2011.[footnote 147]

10.5.3 In October 2023, the NGO, BRAC, reported on a survey, conducted by its Social Empowerment and Legal Protection (SELP) Programme, of nearly 50,000 households across 27 districts, which found that in the past 5 years 44.7% of girls were under 18 at the time of their marriage, and nearly 7% of those were under 15.[footnote 148] The survey found that ‘Factors like household income or poverty, school attainment, and having more girl children did not show any significant correlation with child marriage. Instead, it indicates the deeply rooted cultural practices that perpetuate child marriage…’[footnote 149]

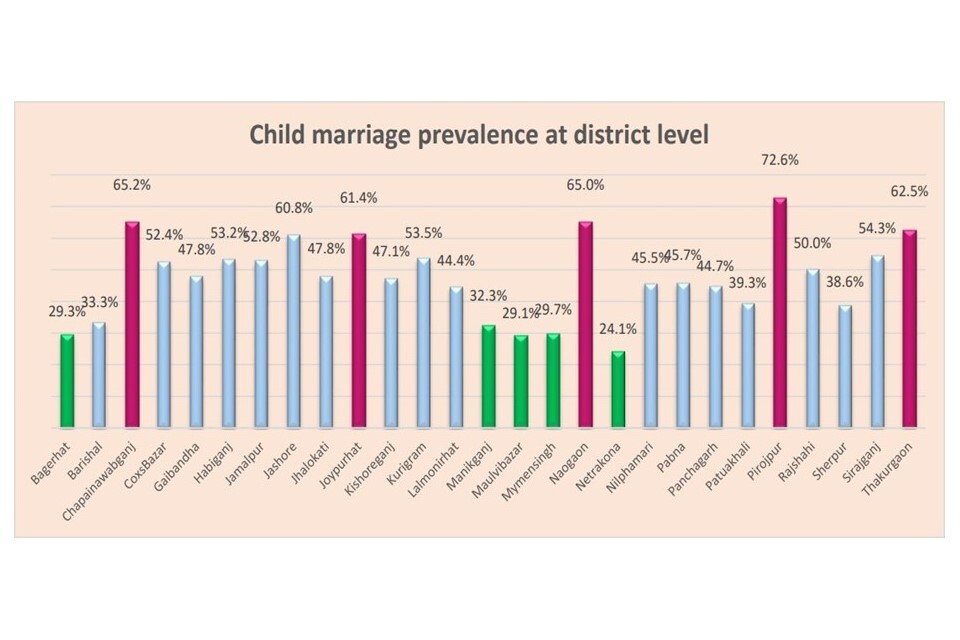

10.5.4 The BRAC graphed[footnote 150]the child marriage prevalence at district level:

10.5.5 According to the USSD HR Report 2022:

‘To reduce early and forced marriages, the government offered stipends for girls’ school expenses beyond the compulsory level. The government and NGOs conducted workshops and public events to teach parents the importance of their daughters waiting until age 18 before marrying.

‘According to the Ministry of Women and Children’s Affairs, two mobile services were available to report cases of child marriage and other services; the Joya App and a “109 Hotline.” According to the ministry, more than 1,000 girls used the hotline every day.’[footnote 151]

10.5.6 A report by the Government of Bangladesh (GoB) to the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review (UPR), dated 1 September 2023, noted that ‘Between 2017-2022, the licenses of 40 marriage registrars and 3 notary public were terminated for involvement in child marriage. 15 million girl students are receiving stipends to prevent child marriage. Between 2012- April 2023, 10,024 child marriages have been stopped through calls received in helpline “109”.[footnote 152]

11. State protection

For general information on protection by the state, see the Country Policy and Information Note on Bangladesh: Actors of protection.

11. 1 Women in the justice system

11.1.1 The Business Standard noted that, as of January 2021, there were 191,295 police personnel[footnote 153]. According to the Bangladesh Police Women Network (BPWN), as of November 2023, there were 16,126 women police officers (compared to 2,520 in 2008), with 13,064 at constable level[footnote 154]. The GoB report to the Working Group on the UPR, dated 1 September 2023, noted that ‘Service desks attended by trained female officers are being launched in all police stations, ensuring a safe and friendly environment where women can file their case without any fear.’[footnote 155] In a 2022 report, BRAC observed that there were 48 women help desks in police stations across the country[footnote 156]. The Business Standard noted that Sub-inspectors (SIs) were assigned to investigate cases but, as there were too few female SIs to have one appointed at every police station, it was mostly male officers who investigated cases of repression of women.[footnote 157]

11.1.2 A UN brief on gender equality, dated October 2022, noted that ‘In the judiciary system, Bangladesh now has seven women judges out of 95 in the high court and 550 women judges out of 2000 in the lower courts across the country. Among the 10,373 members in the Supreme Court Bar Associations 1,636 are women.’[footnote 158]

11.1.3 Prothom Alo reported in September 2023 that there were 99 Women and Children Repression Prevention Tribunals (for hearing cases of violence against women and children) across 64 districts. However, the report noted that, according to High Court sources, ‘… as many as 161,218 cases are pending till 30 June [2023]. 21 per cent of these cases are under trial for five years although the cases with the tribunal are supposed to be disposed of within 180 [days].’[footnote 159]

11.2 Implementation of the law

11.2.1 The June 2023 report by Sultan and Mahpara noted that the implementation of the Domestic Violence (Prevention and Protection) Act 2010 was weak:

‘It has been 12 years since the enactment of the Act, yet the struggle for effective implementation continues… The lack of progress in implementation of the law demonstrates that political action has fallen short of addressing the problem. The government rhetoric about the importance of addressing violence against women and girls, as reflected in various policy documents and laws, does not translate into the allocation of financial or human resources, or the development of capacity for the prevention or redress of DV.’[footnote 160]

11.2.2 In November 2021, The Daily Star, an English-language daily, reported that a judge for the Tribunal for the Prevention of Women and Children Repression, Dhaka, asked the police to refrain from registering rape cases that were reported more than 72 hours after the incident because semen could not be traced after this time.[footnote 161] ASK condemned the court’s statement, adding that the Code of Criminal Procedure does not specify a time limit for bringing cases of any crime into the legal system.[footnote 162]

11.2.3 The USSD HR report 2022 noted:

‘According to guidelines for handling rape cases, the officer in charge of a police station must record any information relating to rape or sexual assault irrespective of the place of occurrence. Chemical and DNA tests must be conducted within 48 hours from when the incident was reported. Guidelines also stipulate every police station must have a female police officer available to survivors of rape or sexual assault during the recording of the case by the duty officer. The statements of the survivor must be recorded in the presence of a lawyer, social worker, protection officer, or any other individual the survivor deems appropriate. Survivors with disabilities should be provided with government-supported interpretation services, if necessary, and the investigating officer along with a female police officer should escort the survivor to a timely medical examination.’[footnote 163]

11.2.4 Amnesty International noted in its report on the human rights situation in Bangladesh, covering 2022, that:

‘Following sustained pressure from women’s rights groups, parliament passed an amendment bill for the Evidence Act 1872, repealing Section 155(4) which allowed defence lawyers to subject rape complainants to questions about their perceived morality and character. However, the Rape Law Reform Coalition criticized the bill for crucial omissions and ambiguities, which could continue to allow victim-shaming in court even in the absence of Section 155(4).’[footnote 164]