Budget 2021 (HTML)

Published 3 March 2021

- Presented to Parliament as a return to an order of the House of Commons

- Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 3 March 2021

- HC number 1226

- © Crown Copyright 2021

- ISBN 978-1-5286-2394-0

1. Executive summary

The Budget follows a year of extraordinary economic challenge as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Like that of many other countries, the UK’s economy has been hit hard, with both the direct effects of the virus and the measures necessary to control it leading to an unprecedented fall in output and higher unemployment.

In the face of this threat, the government acted swiftly to provide support to protect businesses, individuals and public services across the UK, adapting its economic response as the pandemic evolved. Thanks to people’s hard work and sacrifice, supported by the success of the initial stages of the vaccine rollout, there is now a path to the reopening of the economy.

The Budget sets out how the government will extend its economic support to reflect the cautious easing of social distancing rules and the reopening of the economy in the government’s roadmap[footnote 1]. Support in the Budget reflects the easing of restrictions to enable the private sector to bounce back as quickly as possible.

As the economy reopens, the Budget sets out the steps the government is taking to support the recovery, ensuring the economy can build back better, with radical new incentives for business investment and help for businesses to attract the capital, ideas and talent to grow.

Once economic recovery is durably underway, the public finances must be returned to a sustainable path, following a period of record peacetime borrowing. The Budget sets out clearly the size of the challenge and steps to deliver more sustainable public finances, providing certainty and stability to people and businesses and supporting a strong recovery. This action will be underpinned by principles of fairness and sustainability as the government continues to invest in excellent public services and infrastructure to create future growth.

By taking action to protect the economy, support the recovery and repair the public finances, the government is taking the most sustainable route to continuing to deliver first-class frontline public services, funding investment to level up across the whole of the UK, and creating an outward-looking, low-carbon, high-tech economy.

1.1 Economic and fiscal context

COVID-19 has had a profound effect on the UK economy. As the pandemic hit, the UK entered its first recession in 11 years. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted by 24% between February and April 2020, with economic output then rising as restrictions were lifted. Increased cases into the Autumn required renewed restrictions, which led to a slowing of activity and a further fall in November. GDP for 2020 as a whole fell by 9.9%,[footnote 2] the largest annual fall in 300 years.[footnote 3]

COVID-19 has disrupted livelihoods and prevented many people from working. In Spring 2020, many firms stopped hiring and the number of advertised vacancies fell sharply. Redundancies subsequently rose to a record high and vacancies remain low.

The government’s package of economic support has been unlike anything in the UK’s peacetime history. The significant support for individuals, businesses and public services set out at Spending Review 2020[footnote 4] (SR20) and the Budget totals £352 billion across this year and next year. Taking into account the measures announced at Budget 2020, which included significant capital investment, total support for the economy amounts to £407 billion this year and next – the largest peacetime support package for the economy on record. Without this support, the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic would have been considerably worse. The measures in the Budget, particularly the CJRS extension, provide further support to the labour market and the wider economy. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) now expect the peak in unemployment to be 340,000 lower than that assumed in their November 2020 forecast.

The OBR expects the economy to recover quickly when restrictions are lifted. The measures in the Budget, alongside previous support – including next year’s significant £100 billion capital programme – provide a significant boost to the economy this year and into the next, while continuing to support people, businesses and public services. The OBR judges that the Budget’s investment package will boost business investment by around 10% at its peak in 2022-23. Despite more severe restrictions in the first quarter of this year than anticipated in the November forecast, the economy will recover to its pre-crisis peak around six months earlier, with GDP around 0.75% higher in Spring and Summer 2021, as a result of policy measures announced since November.

As a result of the pandemic, borrowing reaches 16.9% of GDP in 2020-21, the highest level of peacetime borrowing on record, and underlying debt will peak at 97.1% in 2023-24. Thanks to the fiscal repair measures set out in the Budget, the OBR forecast shows that the medium-term outlook for the public finances has improved, with the current budget almost in balance, and underlying debt as a share of GDP is expected to fall in the last two years of the forecast.

1.2 Protecting the jobs and livelihoods of the British people

The government’s economic response to COVID-19 has limited the most damaging economic effects of the virus and the restrictions introduced to slow its spread. Annex A of this document sets out all COVID-19 economic support announced before Budget 2021.

Since March 2020 the government has provided £20 billion of grants to businesses alongside over £10 billion of business rates holidays and £73 billion loans and guarantees, supporting every sector of the economy.

The Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) and Self-Employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) have protected jobs and businesses in every part of the UK. Incomes have been further protected through increases to Universal Credit and Working Tax Credit recipients, expanded Statutory Sick Pay, and help with rent and Council Tax. Alongside this, government action through the Plan for Jobs, including the Kickstart and Restart schemes, is helping people looking for work.

The Budget builds on this, extending this support to reflect the cautious reopening of the economy set out in the roadmap. Further investment in vaccine deployment and public services to ensure that people continue to receive the vital support which they need at this stage of the pandemic.

The CJRS and SEISS will be extended to provide protection to businesses and individuals that continue to be affected by the restrictions. For those in need of direct income support, the government is extending the temporary Universal Credit increase and making a one-off payment to Working Tax Credit. The Budget also confirms rates for a range of taxes and duties for the coming year. To help people with the cost of living as the economy recovers, this includes freezes in fuel and alcohol duty.

A new UK-wide mortgage guarantee scheme will make home ownership more achievable for thousands of people, and in England and Northern Ireland extension to the temporary cut in Stamp Duty Land Tax will support the housing market and protect and create jobs.

Alongside this, the Budget extends business rates reliefs, Statutory Sick Pay support and the VAT cut for the UK’s tourism and hospitality sector. The Recovery Loan Scheme will ensure that businesses in all parts of the UK can access the finance they need. The new one-off Restart Grants will give businesses further certainty in order to plan ahead and safely begin trading again over the coming months. The government is also increasing support for traineeships and apprenticeships to help people looking for work. Where certain measures do not apply UK-wide, the devolved administrations will continue to receive funding through the Barnett formula in the usual way.

1.3 Strengthening the public finances

In the near term, continuing to support businesses, jobs and people’s livelihoods up and down the country is vital to give the economy the best possible chance of rebounding as restrictions are lifted. However, it will be necessary to take steps to get the public finances back on track once the economic recovery is durably underway.

The fairest way repair the long-term impact of the crisis on the public finances is to ask everyone to contribute, with the highest income households paying more.

The Budget takes steps towards this by maintaining certain personal tax allowances and thresholds until the end of the forecast period. Those in the highest income households will contribute more and nobody’s take home pay will be less than it is now.

In 2023, well after the economy has regained its pre-pandemic peak, the rate of corporation tax paid by the largest and most profitable businesses will increase. This is a fair way to deliver more sustainable public finances while protecting the UK’s strongly competitive position as the nation with the lowest corporation tax rate in the G7.

The government’s action to repair the public finances will be supported by new steps to tackle tax avoidance and evasion that will raise £2.2 billion between now and 2025-26.

1.4 An investment-led recovery

As well as addressing the immediate challenges of the pandemic and the requirement to return the public finances to a sustainable path in the medium term, the government is acting now to lay the foundations for a recovery driven by the private sector that spreads investment and opportunity throughout the UK, by helping businesses to grow, and improving access to skills, capital and ideas.

A radical new super-deduction tax incentive for companies investing in qualifying plant and machinery will mean for every pound invested companies will see taxes cut by up to 25p.

The government will help over 100,000 small businesses UK-wide to boost their productivity by supporting them to improve their management and adopt new technologies. This will enable them to learn new skills, save time and money, and reach their full potential.

The Budget will further help businesses access the skills, technology and capital they need by modernising and streamlining migration rules, reviewing tax support for research and development, reforming pension rules on investment and reviewing rules for equity offerings. The government is also launching Future Fund: Breakthrough to support the scale up of the most innovative, R&D-intensive businesses.

The Budget will position the UK to make the most of global opportunities after EU exit. The government will create eight new Freeports in England, areas where businesses will benefit from more generous tax reliefs, simplified customs procedures and wider government support, bringing investment, trade and jobs which will regenerate regions across the country that need it most. Freeports will benefit the whole of the UK. Discussions continue between the UK government and the devolved administrations to ensure the delivery of Freeports in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as soon as possible. The Levelling Up, UK Community Renewal, Towns and Community Ownership Funds will create well-paid jobs, revitalise places, and develop hubs of innovation in every part of the UK.

Alongside the Budget, the government’s wider economic plan for significant investment in skills, infrastructure and innovation is set out in ‘Build Back Better: our plan for growth’.[footnote 5] Public investment is a significant part of the government’s economic and fiscal strategy and will contribute to productivity growth. At SR20 the government announced £100 billion of capital investment in 2021-22, a £30 billion cash increase compared to 2019-20.[footnote 6] This is the next stage in plans to spend over £600 billion in gross public investment over the next five years. The Budget also sets out more detail on the new UK Infrastructure Bank. The Bank will partner with the private sector and local government to increase infrastructure investment to help tackle climate change and promote economic growth across the country.

In the year the UK holds the presidency of the UN climate change talks (COP26), the government remains committed to growth that is based on a foundation of sustainability, as the UK makes progress towards meeting its commitment to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in 2050.

Table 1: Budget 2021 policy decisions (£ million)(1)

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total spending policy decisions | -2,765 | -34,770 | +215 | +345 | +720 | +875 | |

| Total tax policy decisions | -3,245 | -24,095 | -8,005 | +12,760 | +24,305 | +28,860 | |

| Total policy decisions | -6,010 | -58,865 | -7,785 | +13,105 | +25,025 | +29,735 | |

| 1 Costings reflect the OBR’s latest economic and fiscal determinants. |

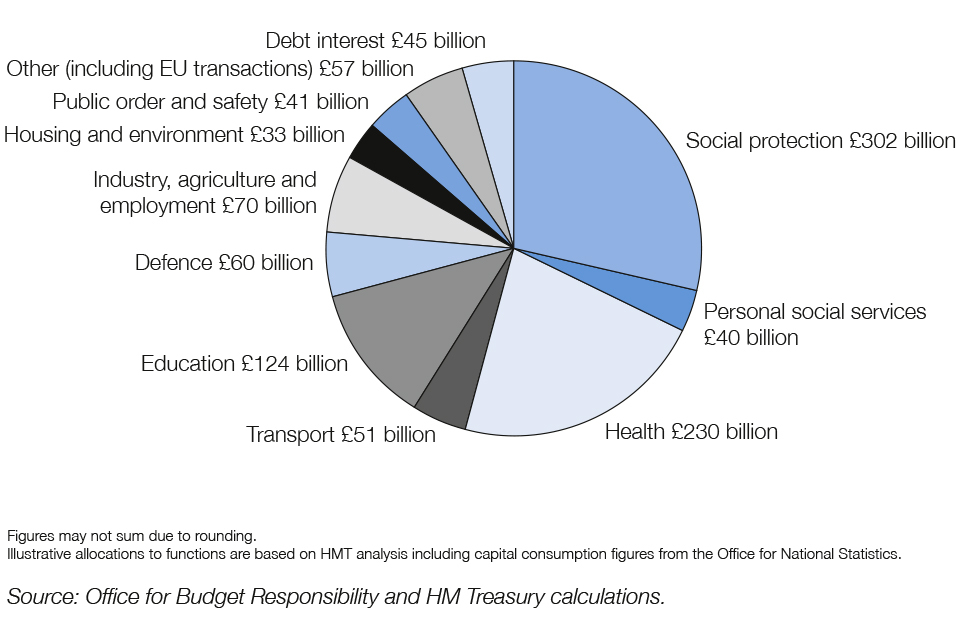

Chart 1: Public sector spending 2021-22

Chart 1: Public sector spending 2021-22

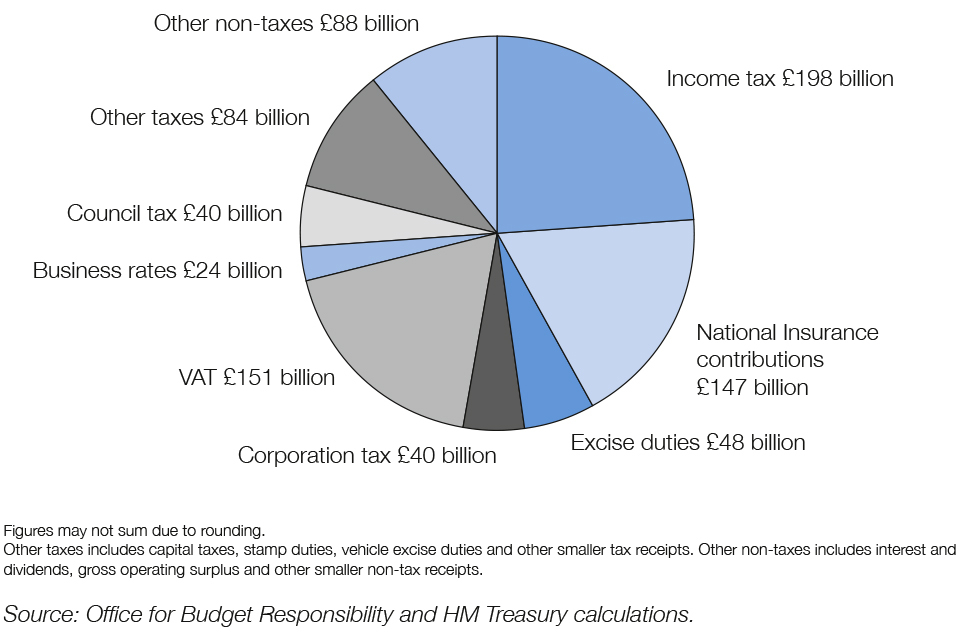

Chart 2: Public sector current receipts 2021-22

Chart 2: Public sector current receipts 2021-22

2. Economy and public finances

The challenges faced by the UK over the past twelve months have been substantial, and the period since the beginning of the year has been the most difficult yet. Responding to the emergence of a new and more transmissible variant of COVID-19, the government took the necessary decision to increase restrictions in order to protect the NHS and save lives. The economic impact of these restrictions has been substantial, though it would have been worse without the unprecedented steps the government has taken throughout the pandemic to protect jobs and livelihoods, support businesses and boost public services across the UK.

The Budget sets out the next phase of the government’s response, providing additional support for people, public services, and businesses most affected by the pandemic of £65 billion in 2020-21 and 2021-22. The Budget confirms the continuation of the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (CJRS) in its current form until the end of June 2021, further income support for the self-employed, and continued significant welfare support. The measures in the Budget, particularly the CJRS extension, will provide further support to the labour market and the wider economy. The OBR now expect the peak in unemployment to be 340,000 lower than that assumed in their November forecast.

The success of the UK’s vaccine programme means the UK can now chart a clear course out of lockdown and the additional measures in this Budget will strengthen the economic recovery. The roadmap will allow businesses to open, providing consumers with more opportunities to spend some of the additional £125 billion of savings accumulated so far during the pandemic. The Budget sets out measures to help the economy bounce back as restrictions are lifted, including a temporary uplift to capital allowances that the OBR expect to raise the level of business investment by around 10% at its peak in 2022-23. In total, the OBR expect GDP to be approximately 0.75% higher in the spring and summer of 2021 due to measures announced since November, and the economy to return to its pre-COVID size six months earlier than previously expected. The unemployment rate is now expected to peak 1 percentage point lower than in the OBR’s November forecast.

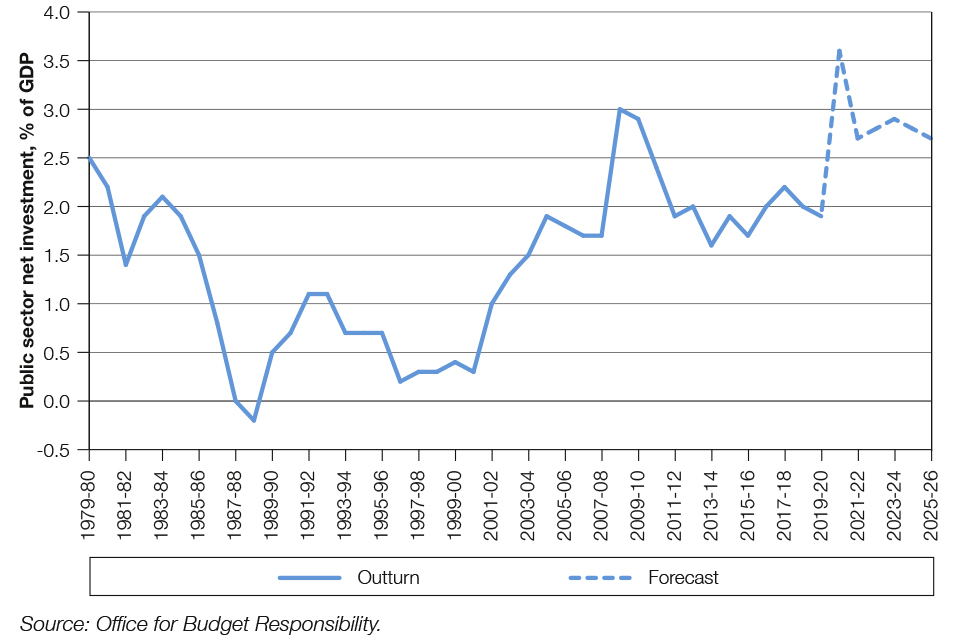

The Budget builds on the government’s existing support, which has helped to limit lasting damage while strengthening the economy in the longer term. Including measures announced at Budget 2020, total support for the economy comes to £407 billion this year and next year – the largest peacetime support package for the economy on record. This includes a step change in capital investment, which will deliver the highest sustained levels of public sector net investment as a proportion of GDP since the late 1970s. The Budget lays the foundations for a strong recovery and greener economy, levelling up the country and spreading prosperity across every part of the UK.

The pandemic and the government’s policy response has led to an unprecedented increase in government borrowing and debt. This is necessary and affordable in the short term, but it would not be sustainable to allow debt to continue to rise indefinitely. The Budget therefore takes action to strengthen the public finances once a durable recovery has taken hold. Setting out a transparent and credible plan now to put the public finances on a sustainable path in the medium term provides certainty and stability. This is necessary given the risks from high debt and will build fiscal resilience, allowing the government to provide support to households and the economy when it is needed most.

2.1 Economic effect of COVID-19

COVID-19 has had a profound effect on the economy. The virus and the restrictions put in place by the government and devolved administrations saw the UK enter its first recession in 11 years in the second quarter of 2020.[footnote 7]

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) contracted by 24% between February and April 2020, with economic output then rising as restrictions were lifted. Rising cases into the autumn required renewed restrictions, which led to slowing growth and a fall in GDP in November. GDP in 2020 fell by 9.9%, the largest annual fall in 300 years.[footnote 8]

COVID-19 has disrupted livelihoods and prevented many people from working. In spring 2020, the number of advertised vacancies fell. Redundancies subsequently rose to a record high and vacancies have remained low. Exceptional support through the government’s Plan for Jobs has helped prevent many more job losses, with 11.2 million jobs furloughed across the UK between March 2020 and 15 February 2021. However, it has not been possible to save every job. The number of people on company payrolls fell by 882,000 between February and November 2020. By the end of last year, the unemployment rate had risen to 5.1%.

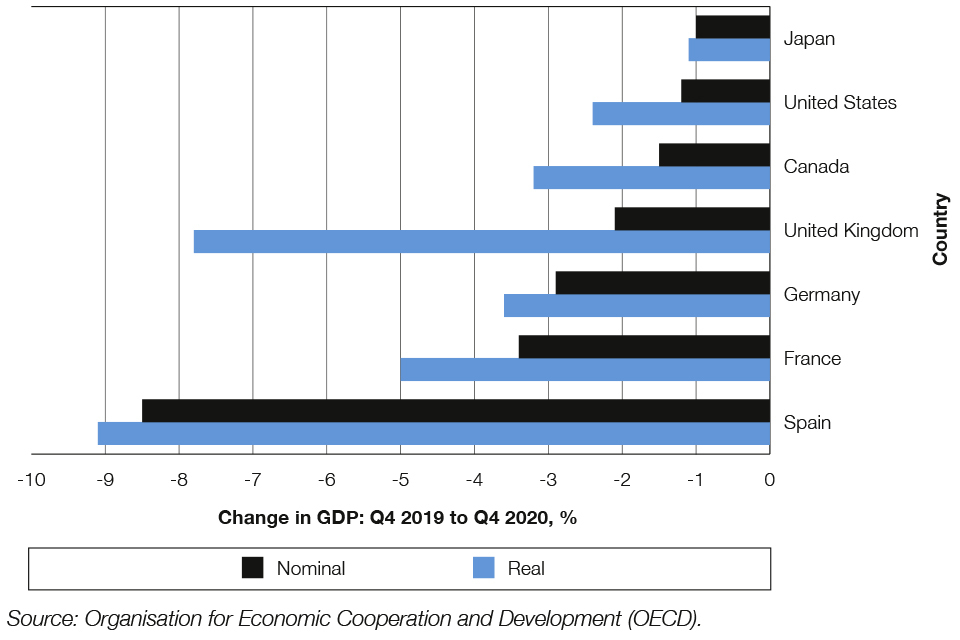

The impact of COVID-19 has been felt around the world. International comparisons of real GDP should be made with care at present because differences in the methods used by national statistical institutes have been exacerbated by the pandemic. The impact of COVID-19 on nominal UK GDP since the start of the pandemic has been broadly in line with that of other advanced economies, reflecting relatively strong government spending and relatively weak consumer spending. Comparing real measures excluding government spending reveals that consumer spending has fallen by more in the UK than other major advanced economies. The UK’s interventions have supported jobs, and the UK labour market has performed relatively well internationally (Box 1.A).

Box 1.A: International Comparisons of Economic Performance

Measuring economic activity during the COVID-19 pandemic has presented unusual challenges. The independent Office for National Statistics (ONS) have said that international comparisons of real GDP growth should be made with care at the moment because there are substantial differences in methods used to estimate real terms public sector activity.

The ONS’s approach to measuring public sector output in real terms follows international best practice. UK estimates are based on what is known as “direct volume measurement” that estimates the actual ‘outputs’ of many public services directly. To do this, the ONS use data such as the number of children attending school or GP appointments carried out, weighted by the cost per unit of the relevant activity. Many other countries instead measure outputs indirectly through the value of ‘inputs’ – such as the money governments spend on teachers’ salaries or the cost of medicines – adjusted for inflation.

The pandemic has led to many countries having to close schools or cancel non-urgent healthcare while also maintaining or even increasing levels of public spending. The UK’s output-based approach records this as a large fall in measured real output and a large increase in price, whereas the input-based approach used in other countries does not to the same extent. The OBR have previously estimated that, if the UK used the input-based approach, then the measured fall in the first estimate of Q2 GDP would have been around 4 percentage points smaller. (a) However, quantifying the precise relative effect is challenging, given variation in methods across countries. In light of this, the ONS has advised that nominal GDP estimates are currently more internationally comparable, as they are not affected by the aforementioned differences in public sector measurement. (b) The level of nominal UK GDP in Q4 2020 was 2.1% lower than at the start of the pandemic, broadly in line with other advanced economies (Chart 1.1).

Chart 1.1: International comparison: Change in GDP since the start of the pandemic: Real and Nominal

Chart 1.1: International comparison: Change in GDP since the start of the pandemic: Real and Nominal

As well as differences in measurement, consumer spending has fallen by more in the UK than other advanced economies, with overall spending broadly in line due to greater government expenditure. (c) Volume measures excluding government consumption will therefore be weaker for the UK. Lower consumer spending was likely driven by two factors. First, restrictions often remained in place longer in the UK than elsewhere. Notably, the national lockdown in the spring of 2020 lasted longer in the UK than many other countries. (d) Second, UK consumer spending is weighted towards social activities – the category of expenditure most affected by restrictions. Social consumption makes up more than 20% of total consumption in the UK, compared to around 16% in the US, Germany, and France. These factors acted to restrict a greater share of consumption in the UK and have contributed to the UK household saving ratio increasing by over 9 percentage points between Q4 2019 and Q3 2020, a larger increase than in France, Germany and Italy, although similar to the US and Spain.

The factors that are driving the relative weakness in the estimates of UK real GDP are expected to unwind as public services return to normal and restrictions are lifted. To the extent that they do, the Bank of England has noted that they could act to boost growth, relative to peer economies. (e)

UK labour market outcomes compare favourably to international peers. As with GDP, the ONS has acknowledged the challenges of accurately measuring unemployment during the pandemic, which may affect comparability. (f) The UK’s unemployment rate has risen by substantially less than the OBR projected in July 2020, with the UK’s CJRS likely to have played a major role in limiting the increase in the unemployment rate last year to just 1.1 percentage points between the three months to February and the three months to December. This increase was smaller than those experienced by France, Spain, Canada and the US over this period. In October 2020 the IMF expected that UK unemployment would average 7.4% in 2021, lower than in France, Italy, Spain and Canada. Taking into account policies announced at the Budget and public health developments including the government’s vaccine programme, the OBR now expect the UK unemployment rate to average 5.6% in 2021.

a Economic and Fiscal Outlook, OBR, November 2020.

b International Comparisons of GDP during the Covid-19 Pandemic, ONS, 2021.

c Quarterly National Accounts Data, OECD, 2021.

d Monetary Policy Report February 2021, Bank of England, 2021.

e Monetary Policy Report February 2021, Bank of England, 2021.

f Measuring the labour market during the pandemic, ONS, 2020.

2.2 Estimating the economic effect of COVID-19 and public health restrictions

As set out in the government’s publication ‘Analysis of the health, economic and social effects of COVID-19 and the approach to tiering’,[footnote 9] the virus and necessary restrictions to contain COVID-19 have had major effects on the economy and public finances.

While the economic impacts of COVID-19 have been substantial, it is not possible to know with confidence how the virus would have evolved or how people and the economy would have responded in different scenarios. Lacking these counterfactuals, estimates of the economic impact of specific restrictions are subject to wide uncertainty and are inevitably only partial.

It is now possible to observe economic indicators under different levels of restrictions throughout 2020, providing some evidence on their economic impact, including for the most recent round of restrictions. This illustrative analysis is backward-looking and based on both the direct impact of restrictions and the behaviour of households and businesses over the period. The OBR’s March 2021 forecast sets out how the economy is expected to evolve based on the government’s roadmap for easing public health restrictions.

UK output fluctuated over the final quarter of 2020 as restrictions were tightened and then loosened. The tiering and lockdown restrictions discussed in this section were specific to England (Table 1.1), with the devolved administrations setting their own public health restrictions.[footnote 10] The tiering system was introduced in October and the majority of the UK was under tier 1 or 2 restrictions.[footnote 11] Reflecting a continued recovery in sectors not affected by restrictions, GDP in October was 5.2% lower than its pre-COVID (February 2020) level and around 2.5 million jobs were furloughed. In November – the month of the second English lockdown, in which the level of restrictions across England was broadly equivalent to tier 4 – output fell to 7.4% below February 2020 levels and around 4 million jobs were furloughed. Following the move back into a stricter form of tiering in December, with tier 2 and 3 involving more restrictions than before and most English regions assigned to either tier 3 or 4, output was 6.3% below February 2020 levels and around 4 million jobs were furloughed.[footnote 12]

Table 1.1: Restrictions and the associated level of activity

| September | October | November | December | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of restrictions (1) | ||||

| Tier 1 (% England's GDP) | 88.2 | 56.8 | 0 | 0.6 |

| Tier 2 (% England's GDP) | 11.8 | 37.6 | 0 | 37.6 |

| Tier 3 (% England's GDP) | 0 | 5.6 | 0 | 30.7 |

| Tier 4 (% England's GDP) | 0 | 0 | 100 | 31.2 |

| UK economic activity | ||||

| GDP (change relative to February 2020) (2) | -5.8% | -5.2% | -7.4% | -6.3% |

| Furlough use (million) (3) | c.3.0 | c.2.5 | c.4.0 | c.4.0 |

| PAYE change since February 20204 | -801k | -820k | -882k | -809k |

| 1 ‘Regional gross domestic product local authorities’, ONS, 2019. The percent of England GDP under each tier is estimated using Local Authority level GDP from 2018 (latest data) and is taken as an average over the month. Tier 4 is itself a category but also covers the November national lockdown. Tiers 2 and 3 were made stricter in December. Prior to the tiering system, all local restrictions across England have been classified as tier 2 following JBC’s definition of local restrictions during that period. |

| 2 ‘GDP monthly estimate, UK: December 2020’, ONS, 2021. |

| 3 ‘Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme statistics’, HMRC, 2021. Figures used are averages over the month. |

| 4 ‘Earnings and employment from Pay As You Earn Real Time Information (RTI) (Experimental Statistic) seasonally adjusted', ONS, 2021. |

The impact of restrictions on the economy has changed over time: in the final quarter of 2020, GDP was higher than through the spring lockdown. In part this reflects schools and colleges remaining open to all students for face-to-face teaching and businesses adapting to a more targeted set of restrictions.

The immediate economic impact of limiting face-to-face teaching in schools and colleges is substantial: output in the education sector fell by around a third in April and May 2020, compared to February 2020. These restrictions also depressed output in other sectors by reducing parents’ working hours. Analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) found that hours worked among all parents halved in May 2020 compared to 2014-15, in part driven by increased childcare responsibilities.[footnote 13] In addition, there are likely to be substantial long-term economic effects, including negative impacts on human capital, productivity and lifetime earnings.

Nearly every sector fared better in November than April 2020, though some sectors were particularly improved, reflecting both more targeted restrictions and businesses having adapted. Manufacturing, construction, distribution and public sector output were all significantly higher in the second lockdown than the first. In November, 11% of firms reported they had temporarily paused trading, compared to 24% in the first two weeks of the first national lockdown in April. This was the case even for heavily affected sectors. For example, 45% of firms in the accommodation and food services sector reported that they were open in November, compared to 18% in early April, possibly reflecting adaptation to the way they deliver their services, such as by offering takeaway services.[footnote 14]

The economic impact of restrictions has not been felt equally. Staff in the hardest hit, largely consumer-facing sectors, such as hospitality, are more likely to be young, female, from an ethnic minority, and lower paid. The unemployment rate for those aged 18 to 24 increased from 10.5% in the three months to February 2020 to 13.4% by the end of the year. The unemployment rate for ethnic minorities increased from 5.8% in the three months to December 2019 to 9.5% in the three months to December 2020.

Analysis led by the Department of Health and Social Care shows that the fall in economic activity and increase in unemployment from the pandemic – including the restrictions put in place to contain it – could have substantial mortality and morbidity impacts, in the medium and long term.[footnote 15] Mental health and wellbeing have suffered during lockdowns, and anxiety and depression levels are now consistently higher than pre-pandemic averages.[footnote 16]

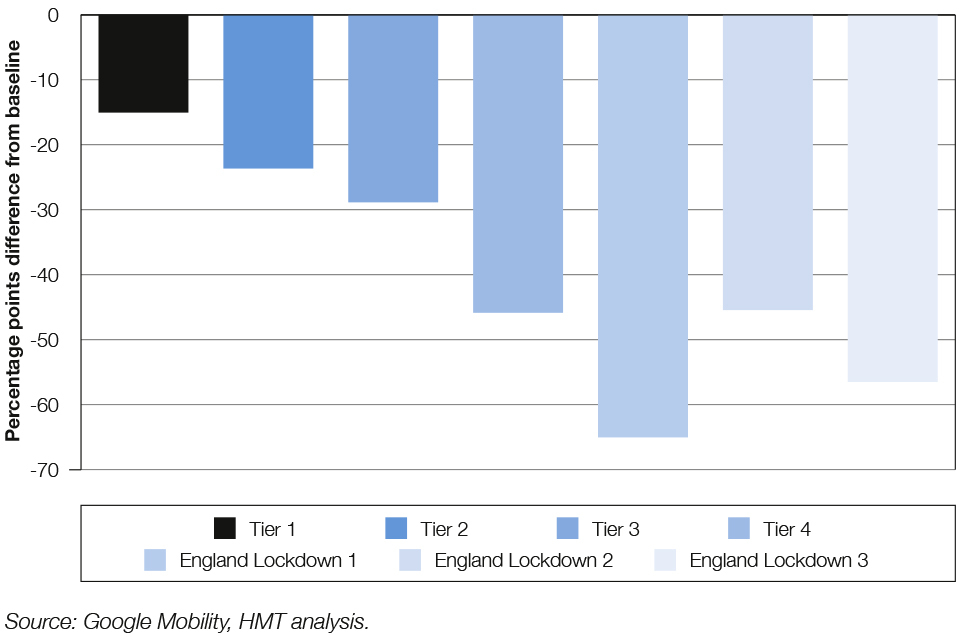

Mobility data published by Google, which measures the amount of time people spend in different types of locations relative to normal, provides another way to assess the short-term impacts of restrictions.[footnote 17] On average, tier 1 restrictions reduced time spent in recreation and retail settings by 15% compared to normal (Chart 1.2).[footnote 18] That increased to a 29% reduction under tier 3 restrictions post-November and a 46% reduction under tier 4 restrictions, similar to the national lockdown in England in November. The impact of the lockdown since the start of January 2021 has been a reduction of time spent in retail and recreation settings of 56%, a larger reduction than in the November lockdown, but a smaller reduction than in the spring lockdown.

Chart 1.2: Estimates of the impact of tiering and lockdown restrictions on retail and recreation mobility

Chart 1.2: Estimates of the impact of tiering and lockdown restrictions on retail and recreation mobility

Measures of mobility have been highly correlated with GDP, though the correlation has decreased over time as restrictions have become more targeted and businesses and households have adapted to them. As set out by the OBR, ”the sharp fall in mobility in April was associated with sharply lower GDP, which fell to 23 per cent below pre-pandemic levels (excluding health and education). But since then, it has improved by more than the recovery in mobility alone would imply, being only 8 per cent below pre-pandemic levels during the second lockdown in November”.[footnote 19]

A range of indicators suggest that the hit to economic activity in January 2021 was greater than November but less than in the spring lockdown. Card spending data from the Bank of England’s Clearing House Automated Payments System (CHAPS) suggests that, on average, spending in January was around 34% below pre-COVID levels observed in February 2020, compared to 14% and 44% below February 2020 levels in November and April 2020 respectively.[footnote 20] In January, 14% of firms reported they had temporarily paused trading, compared to 24% in the first two weeks of the first national lockdown and 11% in November 2020.[footnote 21] Furloughed jobs rose from 4 million at the end of December to 4.7 million at the end of January. Taken together, these indicators suggest activity is currently well above the level seen in the spring, but lower than the November lockdown. In line with this, the OBR forecasts that GDP will fall by 3.8% in the first quarter of 2021.

This backward-looking analysis does not explore the potential for longer-term impacts or economic scarring of COVID-19 and public health restrictions. The OBR has assumed a degree of long-term scarring in its forecast, outlined in paragraph 1.50.

2.3 Responding to COVID-19

Within the government’s wider response to the virus, its economic and fiscal strategy provides:

-

large-scale, targeted economic support for jobs, livelihoods, businesses and public services that preserves the productive capacity of the economy and will help it to bounce back strongly

-

evolving support as restrictions are lifted that prioritises continued investment in the economy to raise productivity, alongside strengthening the public finances over time

2.4 Support to date

The government has already acted to support the economy on a scale unmatched in recent history. It has prevented an even more dramatic fall in output and reduced the adverse effects of the pandemic on the economy’s productive capacity over the longer term. As highlighted by the OBR, this support “has cushioned the blow to employment, consumption and business finances that would otherwise have resulted from the pandemic” in the short term, while in the medium term, the government’s action “will have reduced unnecessary job losses and business failures, thus limiting any persistent ‘scarring’ of the economy’s supply capacity and future tax base”.[footnote 22]

Previous announcements, including at the Spending Review, have already delivered support for:

-

Jobs: The support provided by the government since the start of the crisis has prevented a larger rise in unemployment. For example, the government has helped 1.3 million employers to pay the wages of 11.2 million jobs[footnote 23], with £53.8 billion paid out across the UK, protecting jobs that might otherwise have been lost.

-

Livelihoods: The government expanded statutory sick pay, increased welfare support, and provided help to pay rent and Council Tax, supporting the incomes of millions of households. At the same time, the government has introduced a rent moratorium, and worked with the Financial Conduct Authority to provide mortgage holidays to help borrowers manage their finances during a period of uncertainty. An increase in the National Living Wage from April ensures that the lowest paid will continue to receive pay rises.

-

Businesses: Grants, loans, and tax holidays and reliefs for businesses have helped businesses stay afloat, hold onto workers and keep up to date with their taxes. These measures have helped to reduce the number of insolvencies, which were 27% lower in 2020 compared to 2019. For example, over £70 billion of support and 1.5 million loans have been approved through the government’s UK-wide loan schemes. Through the COVID-19 business grant schemes, government has made available up to £20 billion in cash grants. Government has also provided over £10 billion of support through business rate holidays.

-

Public services: To ensure public services are supported and resilient to the pressures of the pandemic the government provided over £100 billion of support across the UK in 2020-21, including £63 billion to help frontline health services tackle the virus. At SR20 the government announced a further £55 billion to support public services in 2021-22.

On top of substantial UK-wide support, such as CJRS, the government has funded the devolved administrations to provide their own support schemes in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Since the start of the pandemic the devolved administrations have received a total of nearly £19 billion through the Barnett formula, on top of their Budget 2020 baseline funding.

The Bank of England’s independent policy committees have also played an important role by using the policy levers at their disposal, reducing Bank Rate to 0.1%, expanding the MPC’s asset purchase program by £450 billion and reducing the countercyclical capital buffer rate to 0%. The IMF noted that the UK’s macroeconomic policy response has been “one of the best examples of coordinated action globally”.[footnote 24]

2.5 Further support at the Budget

As restrictions are lifted, it is important that the government continues to offer economic support UK-wide as the country fights the virus. Further support provided at the Budget reflects the roadmap set out in the government’s publication ‘COVID-19 Response – Spring 2021’,[footnote 25] and provides the devolved administrations with funding to deliver their own tailored responses, ensuring that as restrictions ease the economy is gradually and safely reopened. The level of support for businesses and individuals continues to be tailored to reflect the changing circumstances. This will facilitate the adjustment necessary for the economic recovery and maximise value for the taxpayer while protecting jobs, livelihoods, individuals and businesses.

Overall, the Budget provides further support of £65 billion in 2020-21 and 2021-22. Taken together with the direct support for the economy provided in response to COVID-19 to date, this represents around £352 billion across 2020-21 and 2021-22.[footnote 26] Once also accounting for support provided at Budget 2020, which included a step change in capital investment, it comes to £407 billion – the largest peacetime support package for the economy on record.[footnote 27], [footnote 28] The government’s support package is one of the largest and most comprehensive in the world (Box 1.B).

This support will help drive an economic recovery that will boost tax receipts and lead to lower government borrowing over time. As explained in Box 1.C fiscal policy remains supportive across the forecast.

Protecting jobs and supporting livelihoods remains a key priority in preventing economic scarring and supporting incomes. The Budget confirms the continuation of the CJRS in its current form until the end of June 2021. As the economy reopens and demand returns, the government will introduce employer contributions towards the cost of unworked hours until September 2021. The Budget also confirms a fourth SEISS grant worth 80% of three months’ average monthly trading profits, and that a fifth and final SEISS grant will be available over the summer. The value will be determined by a turnover test to ensure that support is targeted at those who need it most as the economy reopens. The Budget also confirms continued significant welfare support, including extending the temporary £20 per week increase to the Universal Credit Standard Allowance for a further six months in Great Britain and funding the Northern Ireland Executive to match this uplift. Alongside this, the government will make a one-off payment of £500 to eligible Working Tax Credit recipients across the UK. The Budget also increases support for traineeships for young people and payments for employers who hire new apprenticeships to further help those looking for work.

Businesses are the backbone of our economy, and significant further support confirmed at the Budget will help the economy bounce back once restrictions are lifted. The Budget continues to help businesses which have been most affected by the pandemic, through business rates reliefs; UK-wide VAT reductions for tourism and hospitality; a UK-wide VAT deferral scheme; a new UK-wide loan guarantee scheme supporting businesses’ access to loans and overdrafts; and Restart Grants in England of up to £6,000 per premises for non-essential retail businesses and up to £18,000 per premises for hospitality and other sectors that are opening later; and an additional £425 million of discretionary business grant funding for local authorities to distribute.

Alongside support to address immediate challenges, the government recognises the need to act now to create the conditions to support investment and private sector growth. The Budget includes a package to deliver this including a temporary super deduction for companies investing in qualifying new plant and machinery assets.

Further details of policies confirmed in the Budget are provided in Chapter 2.

Box 1.B: International Comparisons of Direct Fiscal Support

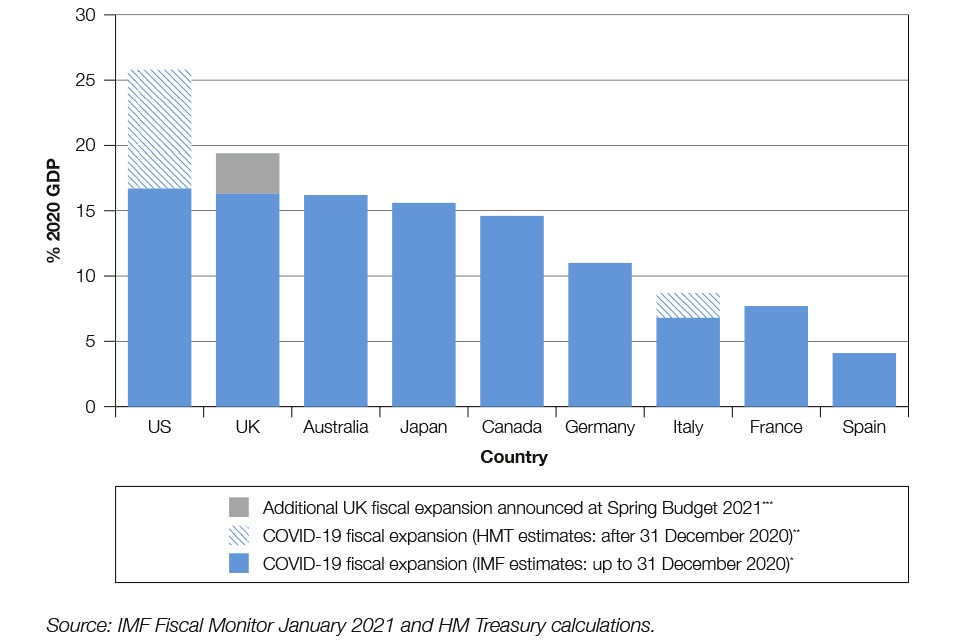

The UK has introduced one of the largest and most comprehensive fiscal packages globally. The UK’s discretionary fiscal expansion in response to COVID-19 amounted to 16.3% of GDP as of 31 December 2020, according to the IMF’s latest published estimates of discretionary fiscal expansion, which show direct fiscal support (a) announced by other countries. Chart 1 shows the IMF estimates, and adds HM Treasury’s illustrative estimates of the possible size of the additional direct fiscal expansion that has been announced by other countries in 2021 for implementation in 2021: the proposed American Rescue Plan in the US and Italy’s increased debt ceiling for its 2021 budget. Incorporating recently proposed measures, including those taken at the Budget, the UK’s remains one of the largest and most comprehensive fiscal packages globally. (b)

Chart 1.3: IMF estimates of discretionary fiscal expansion announced in 2020, with additional measures announced for implementation in 2021 estimated by HM Treasury

Chart 1.3: IMF estimates of discretionary fiscal expansion announced in 2020, with additional measures announced for implementation in 2021 estimated by HM Treasury

a The chart does not include fiscal expansion measures proposed in EU countries’ draft plans for Next Generation EU financing. In its January 2021 Fiscal Policies Database, the IMF states that fiscal expansion from these sources will comprise 3.8% of EU GDP in total with certain countries, including Spain and Italy, expected to receive substantial funding that will supplement the fiscal expansion measures presented in the above chart.

b While the totals are very similar, for consistency across the dataset the UK fiscal expansion presented in the chart builds on the IMF estimates of COVID-19 fiscal expansion and therefore differs from HMT headline figures for fiscal support due to differences in methodologies. For example, IMF figures only include measures classified by the IMF as responding to COVID-19, whereas HMT figures include overall support for the economy based on net policy decisions (as described in Box 1.C). Additionally, the figures here do not account for recostings produced by the OBR in Table A.5 of the Economic and Fiscal Outlook.

- Cumulative discretionary fiscal expansion (additional spending and foregone revenue) announced by governments in response to the COVID-19 pandemic as of 31 December 2020, from the IMF January 2021 Fiscal Policies Database. Excludes automatic stabilisers. Estimates included here are preliminary as governments are taking additional measures or finalising the details of individual measures. Measures are implemented over a varying number of years by country, although the majority of measures are implemented in 2020 and 2021.

** Additional COVID-19 discretionary fiscal expansion announced for implementation in 2021, estimated by HMT based on government announcements. For the US, this assumes full passage of the proposed $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan package. For Italy, this reflects a €32 billion increase in the debt ceiling for the 2021 budget announced in January 2021. While France and Spain have announced further COVID-19 fiscal measures in 2021, the budget and fiscal impact of these proposals have not yet been published and cannot therefore be included above.

*** The additional UK fiscal expansion reflects policy decisions confirmed at this Budget and is equal to the public sector net borrowing impact of policy decisions from this Budget on the scorecard in 2020-21 and 2021-22 Table 2.1.

Box 1.C: Measuring the fiscal policy response to COVID-19

The extent to which fiscal policy is supporting the economy can be measured in multiple ways. A ‘bottom up’ approach sums policy decisions over time and is shown in Table 1.2. The Spending Review and the Budget combined provide £352 billion of direct fiscal support in 2020-21 and 2021-22. Once also accounting for support provided at Budget 2020, which includes a step change in capital investment, total support provided to the economy comes to £407 billion. Overall, including measures announced last March, decisions taken by this government provide material fiscal support to the economy up to 2023-24.

Table 1.2: Total impact of policy decisions on borrowing 2020-21 to 2024-25 (1)

| £bn | Forecast(2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | |

| (1) Budget 2020 | -17.9 | -36.4 | -38.5 | -41.2 | -41.9 |

| (2) Spending Review 2020(3) | -283.9 | -39.4 | 11.6 | 14.3 | 15.0 |

| (3) Re-costings of virus-related support measures(4) | 33.3 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| (4) Budget 20215 | -6.0 | -58.9 | -7.8 | 13.1 | 25.0 |

| Memo: Total excluding (1) | -256.6 | -95.7 | 4.5 | 27.4 | 40.1 |

| Total | -274.5 | -132.2 | -34.0 | -13.7 | -1.9 |

| 1 2025-26 is not included because it was not part of the Budget 2020 forecast horizon |

| 2 Negative numbers represent net support to the economy, including for direct COVID-19 support and wider measures at successive events |

| 3 As published at the Spending Review 2020, before any adjustments made as a result of the OBR's recosting process |

| 4 Table A.5 of the OBR's Economic and Fiscal Outlook includes recostings for some measures that were included in their November forecast |

| 5 Further details of policy decisions at the Budget are given in Table 2.1 |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations |

Alternatively, ‘top down’ indicators use the level or change in headline or cyclically-adjusted borrowing. The ‘fiscal stance’ is the net injection by the government into the non-government sector, or the extent to which fiscal policy is contributing directly to the level of GDP. The ‘fiscal impulse’ shows how the stance changes over time, or how fiscal policy is contributing directly to GDP growth. These top-down measures should be interpreted with caution. First, because they often rely on estimates of the output gap which is unobservable and difficult to assess at present. Second, because the economic impact of the fiscal position depends on the composition of fiscal policy and the context in which support is provided.

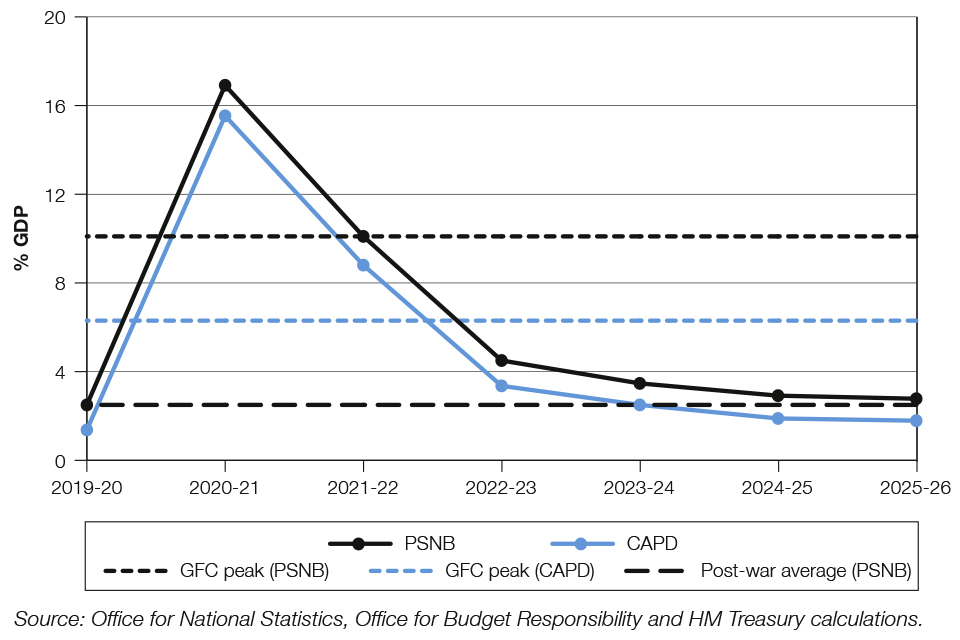

Chart 1.4 illustrates the fiscal stance as measured by headline borrowing and the cyclically adjusted primary deficit (CAPD). (a,b) This indicates that fiscal policy has provided significant support to the level of GDP, particularly in 2020-21 and 2021-22 where the stance remains more supportive than at any time during the global financial crisis. Beyond this point, although headline borrowing falls it remains higher than the post-war average. (c) The fiscal impulse can be measured using the year-on-year change in CAPD, which implies a large positive impulse in 2020-21 and negative impulses in subsequent years. This pattern largely reflects the unique nature of the shock from the pandemic. A large proportion of the positive fiscal impulse results from supporting businesses and individuals as restrictions were implemented in 2020-21 to slow the spread of COVID-19. As restrictions are lifted in 2021-22 this support will reduce alongside a rebound in private sector activity. Overall, both ‘bottom-up’ and ‘top-down’ measures show that fiscal policy is providing significant support to the economy.

Chart 1.4: Fiscal stance

Chart 1.4: Fiscal stance

a Exact definitions of stance and impulse vary. The IMF have noted that a number of metrics can be used as indicators of the fiscal stance. ‘Guidelines for Fiscal Adjustment’, International Monetary Fund.

b One typical fiscal aggregate used is the Cyclically Adjusted Primary Deficit (CAPD). The primary deficit takes the difference between government expenditures (less net interest payments) and revenues. Cyclically adjusting the deficit aims to isolate the actions of government by removing those parts of expenditure and revenue which move automatically with the economic cycle (automatic stabilisers). This process relies on correctly measuring the output gap. Unlike CAPD, headline borrowing (public sector net borrowing) also includes the effects of automatic stabilisers.

C Based on ONS data, public sector net borrowing averages 2.5% of GDP between 1948-2019.

2.6 Near-term outlook

In the near term, the OBR expects the economy to bounce back as restrictions are lifted and government support continues. The success of the UK’s vaccine programme means the government has been able to chart a course out of lockdown and will begin to cautiously ease restrictions in a way that will facilitate economic activity, while continuing to protect public health and NHS capacity. The roadmap published on 22 February 2021 outlines the sequencing and indicative timing for easing restrictions in England. Each full step of the roadmap will be informed by the latest available data and will be five weeks apart in order to provide time to assess the data and provide one week’s notice to businesses and individuals. The devolved administrations are set to ease restrictions to different timescales. The government will work with the devolved administrations to ensure clarity for those who live and work in different parts of the UK.

The package of measures announced at the Budget will protect jobs, support businesses and boosts output over the short term. The OBR judge the temporary increase to capital allowances announced at Budget will increase the level of business investment by approximately 10% at its peak in 2022-23, equivalent to around £20 billion per year. This, combined with other measures announced at Budget and those announced since the OBR’s November forecast, are expected to boost GDP by around 0.75% in the spring and summer of 2021.

The responsiveness of spending to these measures is supported by a strengthening in household finances and corporate balance sheets in aggregate since the onset of the pandemic. Government support, including through the CJRS and SEISS, has supported household incomes, which were in aggregate higher than pre-COVID levels in Q3 2020. Overall household balance sheets have strengthened, with household saving over the first three quarters of 2020 £125 billion higher than in the same quarters in 2019.

While many firms have been hit hard by the pandemic, data on corporate deposits at banks suggest that in aggregate firms accumulated additional savings of close to £100 billion between March and December 2020.[footnote 29] The cost of corporate borrowing from banks was also down to 1.9% in December 2020 from 2.7% in January 2020.[footnote 30]

Economic growth was stronger at the end of last year than the OBR expected in their November forecast, with output ending the year 6.3% below its February 2020 level, around 1 percentage point higher than originally estimated. Following an expected 3.8% fall in GDP in the first quarter, the OBR expects growth to return from the second quarter of this year, with GDP reaching pre-COVID levels two quarters earlier and its unemployment forecast revised down compared to November. GDP is expected to increase by 3.9% in the second quarter, and is then forecast to rise by 3% and 3.3% in the third and fourth quarters. Annual growth is expected to be 4% in 2021. While the unemployment rate is expected to peak in the fourth quarter of this year, at 6.5%, this is 1 percentage point below the peak in the OBR’s November forecast, with the OBR pointing to the extension of the CJRS and additional fiscal support as being largely responsible for this reduction. The unemployment rate then falls gradually throughout the forecast period to 4.4% at the end of 2024.

Table 1.3: Summary of the OBR’s central economic forecast (percentage change on year earlier, unless otherwise stated) (1)

| 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP growth | 1.4 | -9.9 | 4.0 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.7 |

| GDP growth per capita | 0.9 | -10.4 | 3.8 | 6.9 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.5 |

| Main components of GDP | |||||||

| Household consumption (2) | 1.1 | -11.0 | 2.9 | 11.1 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.3 |

| General government consumption | 4.0 | -5.7 | 12.0 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| Fixed investment | 1.5 | -8.7 | 3.7 | 10.8 | 2.6 | -0.5 | 3.3 |

| Business investment | 1.1 | -10.7 | -2.2 | 16.6 | 3.0 | -2.3 | 5.1 |

| General government | 4.0 | 3.8 | 17.8 | 4.2 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Private dwellings (3) | 1.2 | -11.7 | 6.1 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

| Change in inventories (4) | 0.1 | -0.7 | 2.4 | -1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Net trade (4) | -0.1 | 0.7 | -3.6 | -0.4 | 0.3 | 0.0 | -0.1 |

| CPI inflation | 1.8 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Employment (millions) | 32.8 | 32.7 | 32.3 | 32.4 | 32.8 | 33.1 | 33.2 |

| Unemployment (% rate) | 3.8 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 5.9 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| Productivity per hour | 0.2 | 0.5 | -0.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| 1 All figures in this table are rounded to the nearest decimal place. This is not intended to convey a degree of unwarranted accuracy. Components may not sum to total due to rounding and the statistical discrepancy. |

| 2 Includes households and non-profit institutions serving households. |

| 3 Includes transfer costs of non-produced assets. |

| 4 Contribution to GDP growth, percentage points. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

2.7 Medium-term economic and fiscal strategy

With the OBR forecasting a strong rebound in activity in the second half of this year, the measures set out in the Budget support economic recovery over the medium-term. The Budget includes measures to stimulate investment and support an economic recovery in all parts of the UK that is driven by private sector growth, and is transparent about the need to strengthen the public finances. It supports economic stability and gives greater certainty to people and businesses by announcing measures to return to a more sustainable fiscal position once a durable recovery has taken hold.

The government’s fiscal policy at this Budget prioritises support for the economy in the short term, while reducing borrowing to sustainable levels once the economy recovers. The OBR forecast confirms that the current budget deficit as a share of GDP is expected to fall over the forecast period, and that the current budget almost reaches balance in the final year of the forecast.

The crisis has led to a significant increase in public sector debt. While interest rates are currently forecast to remain low, there is a risk that they could rise sharply, which would have significant consequences for the affordability of debt. At the Budget the government has therefore aimed to ensure debt is on a sustainable path. Underlying debt as a share of GDP falls in each of the last two years of the forecast.

This government’s approach at the Budget has balanced the opportunities and risks of the current low interest rate environment, putting the public finances on a sustainable path while also taking advantage of low interest rates to borrow to invest in capital projects that can drive future growth; the government’s significant plans for capital investment are worth over £100 billion in 2021-22 alone.

With sound fiscal management and careful prioritisation, fiscal sustainability can be achieved while continuing to deliver first-class frontline public services and building the future economy. The government will seek to strengthen the public sector balance sheet over the longer term, continuing to manage assets and liabilities, including those arising from the response to COVID-19, to deliver lasting improvements and sustainable public finances.

2.8 Investing in growth

Investment is a significant part of the government’s economic and fiscal strategy. Investment makes the UK economy more productive by improving the technology, infrastructure, and skills that workers need to produce goods and services. Both private and public investment is needed to facilitate productivity growth, which in turn helps secure the UK’s future prosperity and raises living standards. The Budget takes significant steps to address UK productivity growth which has consistently lagged its international peers and is unevenly distributed, deepening geographical inequalities.

As the government begins the work of building the future economy, public investment is needed to level up across the UK and drive the economic recovery. At SR20 the government announced £100 billion of capital investment in 2021-22, a £30 billion cash increase compared to 2019-20.[footnote 31] SR20 also provided multi-year funding certainty for select capital programmes – such as school and hospital rebuilding, and flagship transport schemes. This is part of the government’s plans to spend over £600 billion in gross public investment over the next five years.

Over the long term, increased public investment is expected to increase output. As the OBR stated in March 2020, “the large planned increase in public investment should boost potential output too – eventually by around 2.5 per cent if the increases in general government investment as a share of GDP in the Budget were to be sustained indefinitely”[footnote 32].

As well as boosting public investment, the government is also taking steps to support private sector investment over the medium and long term. One reason for the UK’s relatively poor productivity performance is the low diffusion of technology and best practice through the economy. The UK has relatively low adoption of digital technologies and software compared to international competitors,[footnote 33] while UK SMEs are less likely to use formal management practices than SMEs in peer countries.[footnote 34] Evidence suggests that these directly affect productivity – for example, the use of one business organisation software is associated with a productivity premium of at least 10%,[footnote 35] while ONS analysis shows that small improvements in management practices are associated with a 10% increase in productivity.[footnote 36] The government has published ’Build Back Better: our plan for growth’[footnote 37] alongside the Budget, setting out a vision to tackle these long-standing issues in order to achieve an economic recovery built on three pillars of investment: infrastructure, skills and innovation.

The Budget contains a range of measures designed to support this vision. Innovative, fast-growing firms will likely be a key driver of future growth – despite accounting for less than 1% of UK companies, such firms add £1 trillion to the UK economy, and account for the majority of net employment growth and output growth.[footnote 38] The Budget enables these firms to continue driving growth, for example by providing support for SMEs to boost their digital and management capabilities; a UK Infrastructure Bank with £12 billion of equity and debt capital to finance local authority and private sector infrastructure projects across the UK; and a new £375 million fund to help scale up the most innovative, R&D intensive businesses.

These actions will also help spread opportunity across the UK, achieving the government’s ambition of levelling up every part of the country. They will also be crucial to supporting the government’s vision for a Global Britain, and contributing to the transition towards a net zero society.

As a result of the COVID-19 crisis, some economic scarring is expected. In its central forecast, the OBR assumes some long-term scarring in the economy of around 3% of GDP, unchanged since its November forecast. However, it is likely that in the absence of government support, this long-term impact would be much greater, with the OBR noting that “the scope for scarring would have been considerably greater if the full effect of public health measures on output had fed through to private sector employment and incomes rather than continuing to be partly borne by the Government via the furlough scheme, business support grants and other measures”.[footnote 39]

The OBR have not made material adjustments to the forecast in light of the new Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) signed between the UK and EU. They have concluded that the terms of the agreement are broadly in line with the typical free-trade agreement assumed in previous forecasts. The OBR now expect temporary “near-term disruption to EU-UK goods trade to reduce GDP by 0.5 per cent in the first quarter of this year”,[footnote 40] but this effect dissipates afterwards as firms on both sides of the Channel grow accustomed to new trading arrangements.

2.9 Sustainable public finances

Strong public finances are a fundamental part of a strong economy and a strong Union. The stability and certainty that comes from ensuring the public finances are on a sustainable path will support economic recovery across the UK. This is also necessary given the risks from high debt and will build fiscal resilience, allowing the government to provide support to households and the economy when it is needed most.

The economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government’s response have resulted in significant increases in borrowing and debt, which are necessary and affordable in the short term, but which would be unsustainable over the longer term. Public sector net borrowing is 10.3% of GDP in 2021-22,[footnote 41] the second highest on record during peacetime after 2020-21.[footnote 42] Underlying debt (public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England) is 93.8% of GDP in 2021-22.

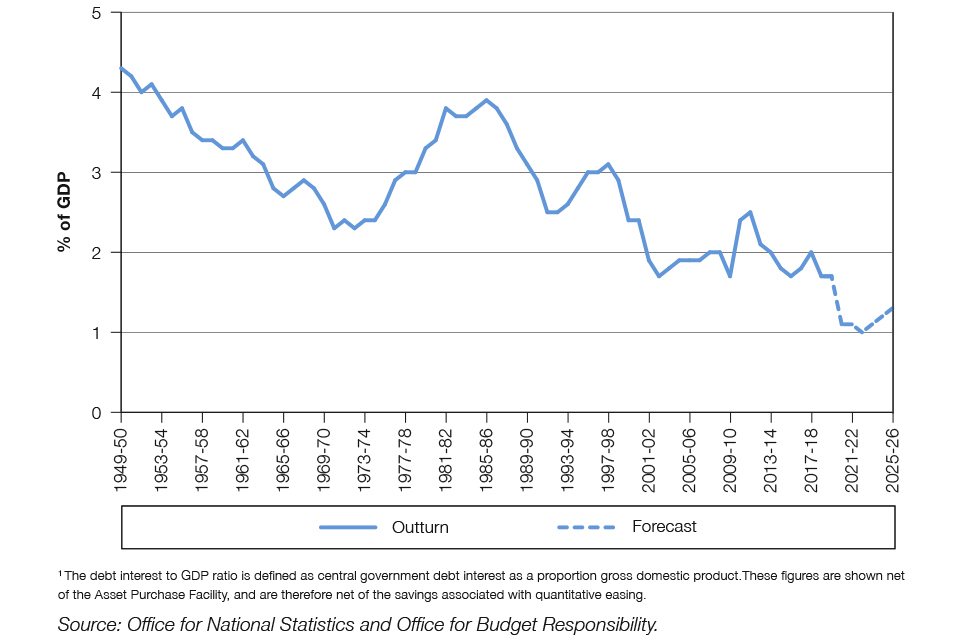

Despite the current historically low cost of borrowing and the measures taken today to strengthen the public finances, the OBR forecasts that central government debt interest net of the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) will be £33.7 billion in the final year of the forecast. While borrowing costs are currently forecast to remain low, there is a risk that they will rise which would have significant consequences for the sustainability of the public finances (as set out in Box 1.D). It is important to take action as the economy durably recovers to limit the UK’s exposure to this risk and to build fiscal resilience. The recent sharp increases in many global sovereign bond yields, largely driven by positive economic sentiment, have already led to an increase in expected government borrowing costs.[footnote 43]

It is also important to maintain space to address any future economic challenges. The UK has experienced two ‘once-in-a-generation’ economic shocks in just over a decade, highlighting the importance of strong public finances. Action taken over the last decade to restore the public finances to health, enabled the government to fund a comprehensive package of support for the economy when most needed. Returning the public finances to a more sustainable path will rebuild vital space to respond to future economic challenges and ensure the government can continue to prioritise investment in public services and the economic recovery.

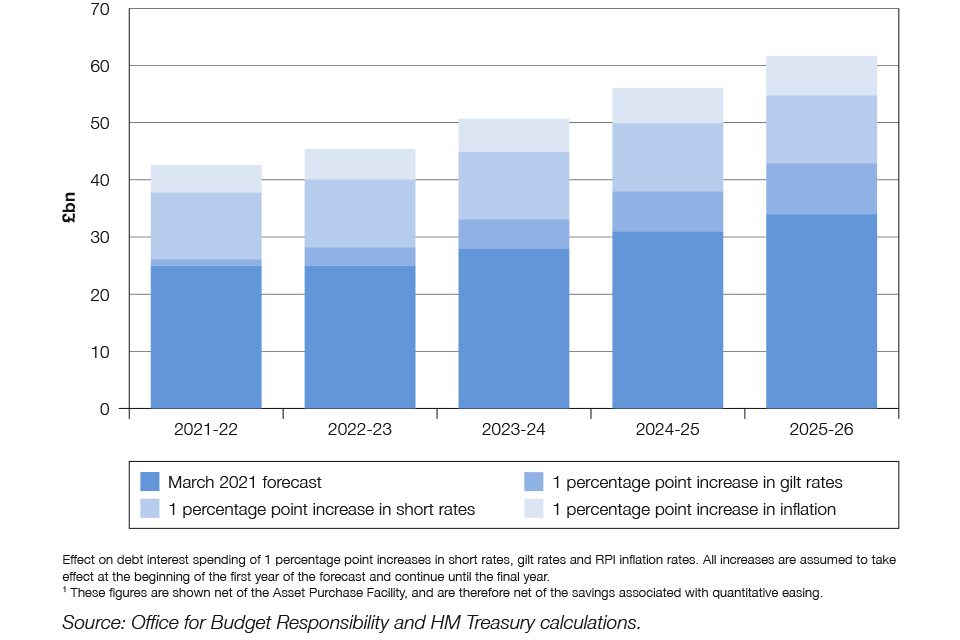

Box 1.D: Sensitivity of debt interest to changes in interest rates and inflation

Today’s low interest rates, shown in Chart 1.5, mean that current levels of government borrowing are affordable in the short term. Demand for the UK’s debt remains strong with a well-diversified investor base and Debt Management Office (DMO) auctions since the beginning of the crisis have performed well. Having rebuilt the strength of the public finances over the previous decade, and underpinned by the UK’s strong institutional framework, the government has been able to borrow to provide a comprehensive package of support for the economy. However, increased borrowing leaves the public finances more vulnerable to future shocks. As the OBR has shown, since March 2020, debt interest spending in the last year of the forecast has become 41% more sensitive to a 1 percentage point increase in gilt rates, and nearly twice as sensitive to a 1 percentage point increase in short rates. The OBR estimates that the sensitivity to changes in RPI inflation is broadly similar.[footnote 44] As the OBR notes, the overall impact on the public finances would depend on the source of the shock; if the increase in interest rates reflected higher economic growth, the debt stock could be lower and the primary balance more favourable.

The increased sensitivity to gilt rates reflects both higher initial debt and higher net borrowing over the forecast. The average annual net cash requirement is expected to rise from 2.8% over the remainder of the March 2020 forecast, to 5.5% of GDP over the remainder of the Budget forecast. A 1 percentage point increase in gilt rates would increase debt interest spending by £8.9 billion in the final year of the forecast.

Extensions of the APF have increased sensitivity to short rates, as longer-maturity gilts have been substituted for Bank of England reserves that are used to finance the APF’s holdings of those gilts.[footnote 45] Bank Rate is paid on these reserves, increasing sensitivity to short rates. A 1 percentage point increase in short rates would now increase debt interest spending by £11.9 billion in the final year of the forecast, assuming the APF remains at its current target level.

The UK’s relatively large stock of inflation-linked debt increases the UK’s sensitivity to inflation; a 1 percentage point increase in RPI inflation would increase spending on debt interest by £6.9 billion. However, the sensitivity of debt interest to RPI is largely unchanged from March 2020, which in part reflects the government’s strategy to reduce the share of inflation-linked debt in total issuance.

The combined impact of 1 percentage point changes to each of these variables would be a £17.6 billion increase in spending on debt interest by next year, and if sustained, would increase spending by £27.8 billion in 2025-26.

Chart 1.5: Central government debt interest net of APF (1)

Chart 1.5: Central government debt interest net of APF

Chart 1.6: Central government debt interest net of APF (1) following sustained rises in rates

Chart 1.6: Central government debt interest net of APF1 following sustained rises in rates

Having borrowed to support workers and households, businesses and public services through the most challenging stages of the pandemic, the government is committed to tackling the challenge of repairing the public finances over the medium term. The fairest way to continue to fund excellent public services is with the highest earning households contributing more and companies contributing in recognition of the support they have received from government. Maintaining both the personal allowance and higher rate threshold will mean nobody’s take-home pay will be less than it is now. In 2023, the main rate of corporation tax, paid on company profits, will increase to 25%.

The Budget provides transparency on the necessary repairs to the public finances over the medium term, giving advance notice of future tax changes which brings increased certainty for people and business. Fiscal policy adjusts gradually and remains historically supportive as outlined in Box 1.C. Policy measures announced by this government including Budget 2020 overall remain materially supportive until 2023-24. Additional measures at this Budget continue to support the economy until 2022-23. By 2023-24, a broad range of metrics suggest that economic recovery will be durably underway. For example, the OBR forecasts that real GDP will reach its pre-pandemic peak by Q2 of 2022; that the economy will be close to potential across 2023; and that the unemployment rate returns close to its pre-crisis low over the course of 2024. After taking account of all the measures in this Budget, the OBR expects this economic recovery to be sustained with unemployment continuing to fall and output remaining close to potential in the later part of the forecast.

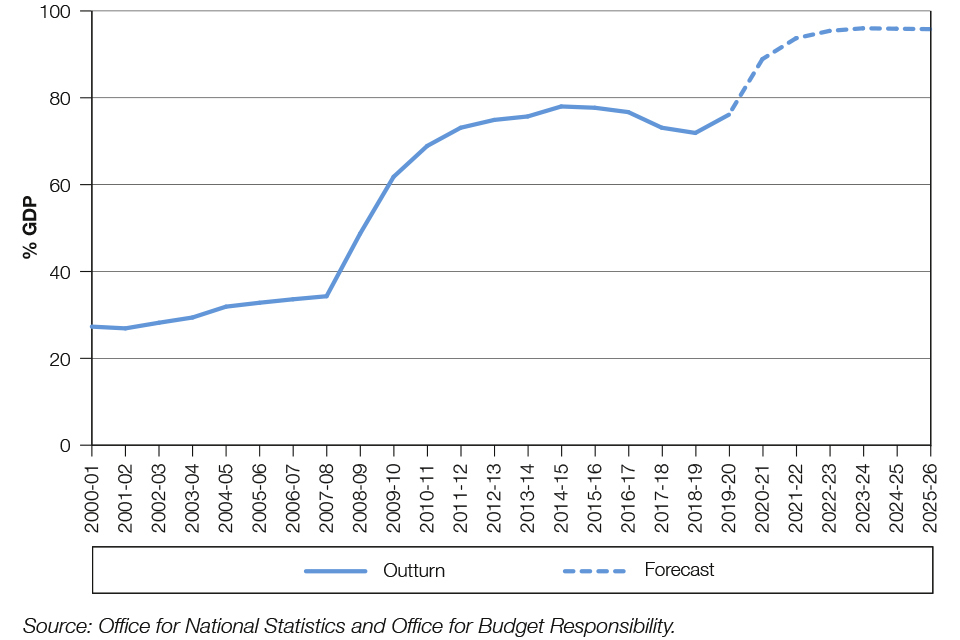

The OBR forecast shows that the medium-term outlook for the public finances has returned to a more sustainable path, supported by the fiscal repair measures set out in the Budget.[footnote 46] The current budget deficit falls over the forecast period to £0.9 billion in the final year of the forecast while public sector net investment remains at 2.9% of GDP on average over the forecast. Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing is 2.7% of GDP in the final year of the forecast. Underlying debt reaches 97.1% of GDP in 2023-24 but falls in the final years of the forecast albeit remaining significantly above pre-pandemic levels as shown in Chart 1.7.

Chart 1.7: Public sector net debt excluding Bank of England

Chart 1.7: Public sector net debt excluding Bank of England

Table 1.4: Overview of the OBR’s debt and borrowing forecasts (% GDP)

| Outturn | Forecast | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | |

| Public sector net debt(1) | 84.4 | 100.2 | 107.4 | 109.0 | 109.7 | 106.2 | 103.8 |

| Public sector net debt ex Bank of England(1) | 76.1 | 88.8 | 93.8 | 96.0 | 97.1 | 97.0 | 96.8 |

| Public sector net financial liabilities(1) | 71.5 | 86.9 | 90.4 | 90.8 | 90.2 | 88.9 | 87.4 |

| General government gross debt(2) | 84.4 | 107.6 | 107.2 | 107.8 | 109.3 | 110.0 | 110.4 |

| Public sector net borrowing | 2.6 | 16.9 | 10.3 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 2.9 | 2.8 |

| Cyclically-adjusted public sector net borrowing | 2.6 | 16.5 | 9.7 | 4.2 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 2.7 |

| Public sector current budget deficit | 0.6 | 13.3 | 7.6 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

| Cyclically-adjusted current budget deficit | 0.7 | 12.9 | 6.9 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| General government net borrowing(2) | 2.8 | 17.1 | 10.6 | 4.5 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| 1 Debt and liabilities at end of March; GDP centred on end of March. |

| 2 Consistent with Manual on Government Deficit and Debt, Eurostat, 2019. |

| Source: Office for National Statistics and Office for Budget Responsibility. |

Table 1.5: Changes to public sector net borrowing since Spending Review 2020 (£ billion)

| 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spending Review 2020 | 393.5 | 164.2 | 104.6 | 100.4 | 99.6 | 101.8 |

| Total changes since Spending Review 2020(1) | -38.9 | 69.7 | 2.3 | -15.1 | -25.1 | -28.2 |

| of which | ||||||

| Direct effect of policy decisions(2) | 9.0 | 58.9 | 5.5 | -15.1 | -27.5 | -32.4 |

| Indirect effect of policy decisions | -0.5 | -5.4 | -5.5 | -4.0 | -4.0 | -4.1 |

| Other | -47.4 | 16.2 | 2.3 | 4.1 | 6.3 | 8.3 |

| Budget 2021 | 354.6 | 233.9 | 106.9 | 85.3 | 74.4 | 73.7 |

| Figures may not sum due to rounding |

| Note: This table uses the convention that a negative figure means a reduction in PSNB. |

| 1 Equivalent to lines from Table 3.25 of the OBR (March 2021) 'Economic and fiscal outlook'; full references available in 'Budget 2021 data sources'. |

| 2 For the purposes of this table, definitions aligned with OBR Table 3.25 |

| Source: Office for Budget Responsibility and HM Treasury calculations |

Table 1.5 shows the impact of Budget measures on public sector net borrowing which falls across the forecast period to 2.8% of GDP in 2025-26. The OBR note that the stabilisation of underlying debt is entirely due to the impact of the government’s policy measures.[footnote 47]

Policy makers around the world face common challenges in addressing the impact of COVID-19 on public finances. The UK’s approach to fiscal policy, prioritising substantial support in the near-term and investment during the economic recovery while restoring the public finances to health when the recovery takes hold is in line with the international consensus. While stressing that fiscal adjustment should not come prematurely, the IMF has noted that it is not too early to begin to lay the groundwork for strong public finances and note the benefits of early announcement of plans.[footnote 48], [footnote 49]

The current level of uncertainty means it is not yet the right time to set new medium-term fiscal rules and many countries around the world have suspended their fiscal rules. The fiscal framework remains under review, and the government intends to set out new fiscal rules later in the year, providing economic uncertainty recedes further. The autumn 2016 Charter for Budget Responsibility[footnote 50] remains in force at the current time.

2.10 Public spending

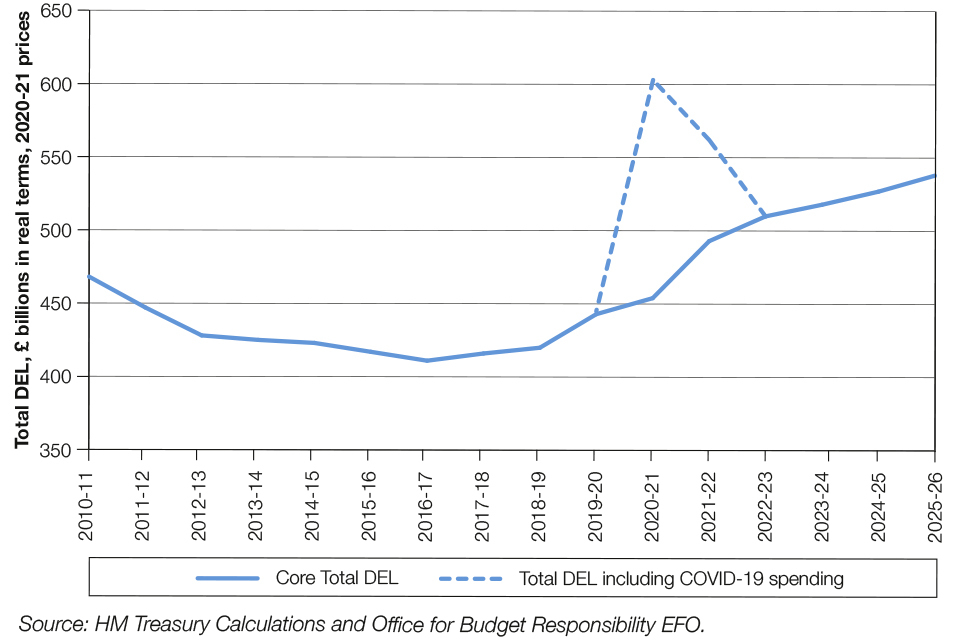

The government has overseen record increases in public spending to fund world-class public services, providing a high quality, resilient healthcare system, a quality educational experience for all learners, and supporting local authorities in their efforts to serve local communities.

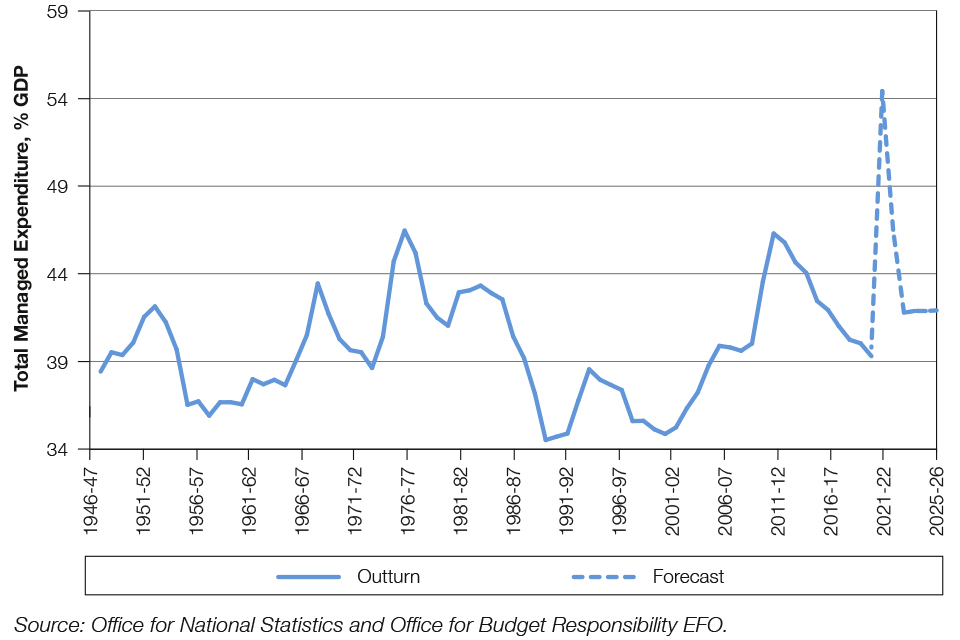

In 2020-21 the government increased day-to-day departmental spending by £20 billion in a single year.[footnote 51] In 2021-22 there was a further increase in core day-to-day spending – before taking into account COVID-19 – of £22 billion.[footnote 52] This means that across 2019-20 to 2021-22 day-to-day departmental spending has risen at a 3% average annual real growth rate. This is in addition to the government’s significant plans for capital investment, worth £100 billion next year, a £30 billion cash increase compared to 2019-20. This means that outside of the global financial crisis, public spending will be the highest as a share of GDP recorded for over 40 years.

- Individual budgets for all departments have been set until 2021-22 for both departmental capital totals (CDEL) and departmental resource totals (RDEL). Longer-term settlements have been announced for schools, the NHS and the Ministry of Defence. At SR20, the government also agreed select multi-year settlements to maintain momentum on key infrastructure projects, including targeted investment to deliver a green industrial revolution, tackle climate change and support hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Table 1.6: Departmental Programme and Administration Budgets (Resource DEL excluding depreciation)

| £ billion | Outturn (1) | Plans (2) | Plans | Plans | Plans | Plans | Plans |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | |

| Resource DEL excluding depreciation | |||||||

| Health and Social Care | 133.4 | 140.3 | 147.1 | 58.9 | 22.0 | 199.2 | 169.1 |

| of which: NHS England | 123.7 | 129.7 | 136.1 | 18.0 | 3.0 | 147.7 | 139.1 |

| Education | 63.5 | 67.4 | 70.8 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 69.1 | 71.6 |

| of which: schools | 44.4 | 47.6 | 49.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 47.6 | 49.8 |

| Home Office | 11.5 | 12.9 | 13.7 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 14.7 | 13.7 |

| Justice | 7.9 | 8.4 | 8.4 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 8.9 | 8.7 |

| Law Officers' Departments | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 |

| Defence | 29.5 | 30.8 | 31.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 30.8 | 31.6 |

| Single Intelligence Account | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office | 10.4 | 9.7 | 7.4 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 9.7 | 7.4 |

| MHCLG Local Government (3) | 7.0 | 5.4 | 8.5 | 16.1 | 9.1 | 21.5 | 17.6 |

| MHCLG Housing and Communities | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| Transport | 3.5 | 4.1 | 4.7 | 13.0 | 2.1 | 17.0 | 6.8 |

| Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 25.3 | 5.5 | 27.6 | 8.1 |

| Digital, Culture, Media and Sport | 1.6 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 3.6 | 1.7 |

| Environment, Food and Rural Affairs | 2.0 | 4.2 | 4.2 | 0.4 | 0.0 | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| International Trade | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Work and Pensions | 5.7 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 1.1 | 3.6 | 6.7 | 9.2 |

| HM Revenue and Customs | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 4.6 | 5.6 |

| HM Treasury | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Cabinet Office | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.7 |

| Scotland (4) | 28.6 | 30.5 | 31.6 | 9.6 | 2.5 | 40.1 | 34.2 |

| Wales (5) | 12.0 | 13.1 | 13.6 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 18.9 | 15.1 |

| Northern Ireland | 11.4 | 11.9 | 12.0 | 3.3 | 0.9 | 15.2 | 12.9 |

| Small and Independent Bodies | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| Reserves | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.9 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 0.0 | 26.7 |

| Total Resource DEL excluding depreciation | 343.0 | 362.7 | 385.0 | 140.6 | 68.0 | 503.3 | 453.0 |

| Allowance for Shortfall (6) | - | - | - | - | - | -19.9 | -7.5 |

| Total Resource DEL excluding depreciation, post allowance for shortfall | - | - | - | - | - | 483.3 | 445.5 |

| 1 2019-20 final PESA outturn, adjusted for £2.2 billion of COVID-19 spend. |

| 2 2020-21 figures reflect the control totals set at Supplementary Estimates. The devolved administrations’ total RDEL funding for 2020-21 includes £1.6 billion announced in February 2021 that can be spent in 2020-21 or 2021-22. |

| 3 2021-22 figures are not directly comparable with previous years because 2019-20 and 2020-21 are reduced by Business Rates Retention pilots that switched spending into AME from DEL. 2020-21 is also lower than other years due to a switch at main estimates of £0.9 billion from Local Government DEL to MHCLG Housing and Communities DEL and a further Main Estimates reduction of £1.5 billion due to that amount being brought forward into 2019-20. |

| 4 Resource DEL excluding depreciation is before adjustments for tax and welfare devolution as set out in the Scottish Government’s fiscal framework. |

| 5 Resource DEL excluding depreciation is after adjustments for tax devolution as set out in the Welsh Government’s fiscal framework. |

| 6 The Office for Budget Responsibility's forecast of underspends in Resource DEL. |

Table 1.7: Departmental Capital Budgets (Capital DEL)