About the Strategy

Published 9 August 2018

Applies to England

Developing the Strategy

Engagement

In spring 2018 the Office for Civil Society in the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport carried out a public engagement exercise. The purpose was to develop the Strategy through discussion and debate across the country and across sectors, building on the experiences and knowledge from the past and shaping the future of the country we want to live in.

We invited views and ideas on how the government can work with and for civil society to:

- support people of all ages and backgrounds to play an active role in building a stronger society

- unlock the full potential of the private and public sectors to support social good

- help improve places to live and work in, including breaking down barriers in our communities and building a common sense of shared identity, belonging and purpose

- build strong local public services that respond to the needs of communities and draw on the talents of diverse people and organisations from across different sectors

We encouraged people to share their views using our online platform on GOV.UK. We also encouraged people to have group discussions and feedback via the online platform. We offered guidance and toolkits to help facilitate these conversations.

We held a number of workshops. These included regional workshops in Birmingham, Leicester, London, and York, cross-government workshops with officials from different departments, co-hosted workshops with social sector partners such as the Small Charities Coalition, five workshops with young people specifically facilitated by youth organisations, and workshops on emerging issues such as social value and digital skills.

We held a ministerial conference in May, and over 100 leaders across sectors took part. We also held discussions at Office for Civil Society stakeholder forums, including the Large Charities Group.

In total we received 513 responses via the online platform and over 90 standalone responses by email or post. To analyse the responses and discussions we used both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Annex A outlines demographic information about respondents to the online platform. A summary of what we heard is set out below. While the responses and discussions have been fundamental in shaping the Strategy, and all views have been considered, not everything that was said is picked up in the Strategy itself. The summary therefore does not represent a statement of government policy.

What we heard

We heard that the government’s relationship with civil society should build on a number of values and behaviours. Commitment was a key value raised. Participants told us this meant commitment to engage over the long-term, beyond electoral cycles, and a commitment to genuine partnership. We also heard that the government should commit to a genuine cross-government approach when working with and for civil society. It should work with the complexity of civil society, recognising and accepting that civil society is hugely diverse and cannot be ‘tamed’ towards overarching goals. Trust was a further key value participants highlighted. We heard that the government should trust in local knowledge and experience, and devolve decision-making.

Participants also told us respect is essential. We heard that the government should respect and value civil society by engaging and listening, and feeding back what is being done as a result. The government should acknowledge the important role charities play in increasing democratic engagement and civic participation. It should recognise and promote more social enterprises and mission-led businesses, as well as value the contribution of smaller, local organisations. The need to listen to young people’s voices also came through strongly throughout the engagement exercise. We also heard that the government should be transparent about decision-making and public sector funding.

Inclusion was an important value raised throughout the engagement exercise. The government’s work with and for civil society should be inclusive of people of all ages, backgrounds, and abilities. It should include not just urban, but also rural areas, and not just bigger civil society organisations, but also smaller ones.

To demonstrate its commitment to and investment in civil society, we heard that the government should play a range of different roles. It should encourage and enable people to take part. This includes, for example, promoting a range of opportunities that are flexible and suit people’s abilities and life circumstances. It involves increasing people’s understanding of their civic responsibilities, and their ability to influence change at a local and national level, starting from a young age. Enabling people to contribute to society also requires the government to ensure that people have sufficient access to services and opportunities to meet their basic needs in the first instance.

Participants told us that the government should enable capability and capacity building in civil society. Training, advice, guidance, and sharing of best practices were examples of the forms this could take. Further examples included the funding of core costs, a focus on the resilience of civil society organisations, and support for activities and services that work, not just innovation and growth. Supporting the use of digital technology to reach audiences, beneficiaries, and donors was another way for the government to build capability and capacity.

We also heard that the government should build the evidence base of what works and promote improvement of civil society activities and services. To do so, the government should recognise how hard it can be to clearly and quickly demonstrate the impact of work, which is often only measurable a long time after a project is completed. The government should support the measurement and demonstration of social value, especially by smaller civil society organisations.

Participants told us that the government should facilitate partnerships and promote sharing within communities and across sectors. This includes the sharing of information, data, ideas, and networks. Sharing more physical and virtual spaces, places, and events would allow more people to come together, connect, and work towards shared goals. The government should bring people and organisations together to pool funding and leverage new sources of funding to address issues.

We heard that the government should re-evaluate its approach to funding and financing civil society organisations. For example, it should recalibrate its focus on social investment to ensure that an appropriate range of funding and financing models are available to the social sector. We heard that the government should provide more of the right kind of funding, including smaller and regular grants, offer multi-year funding, and seed funding. Further examples include the pursuit of asset transfer policies with greater vigour, the growing of social investment, blended finance, and start-up loans, as well as promoting alternative and new models of funding such as crowdfunding, community shares, and match-funding. Participants told us that the government should influence the wider funding environment through place-based investment strategies, leveraging funding from new sources, encouraging philanthropy, and the imaginative use of dormant assets.

We heard that the government should improve commissioning. This includes, for example, reforming the Social Value Act, genuinely co-producing services, enabling local solutions, and using a range of financial models in commissioning.

Participants also told us that the government should ensure the legal framework enhances civil society. We heard calls to reform regulatory policy to protect and promote independence, voice, and the right to campaign. Views ranged from abolishing the Lobbying Act to clarifying it. Participants also told us to strengthen the Social Value Act.

People and organisations who took part in the engagement exercise said that the government should ensure that tax frameworks support civil society. This included suggestions to bring greater coherence to taxing charities, social enterprises, cooperatives, and businesses. We heard that the government should publicise existing tax reliefs better, expand Social Investment Tax Relief, and incentivise cross-sector collaboration.

We would like to thank everyone who took the time to engage with us, sharing views, ideas, knowledge, and experience.

Photo credit: Policy Lab

Scope of the Strategy

The Civil Society Strategy extends to England only. Policy responsibility for civil society matters are devolved in Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. However, the Strategy references some policies which extend beyond England. In these cases the extent of the policy is highlighted in the text or an endnote.

Defining civil society

In its original meaning, ‘civil society’ refers to the institutions which exist between the household and the core functions of the state. More recently, the term has become synonymous with a ‘sector’, sometimes called the ‘voluntary’, ‘third’ or ‘social’ sector - essentially the range of organisations not owned by the government and which do not distribute profits.

The responses that the government received during its engagement exercise, and the conversations we held with public, private, and social sector leaders in preparation for this Strategy, have convinced us that the original meaning is too broad and the recent meaning is too narrow.

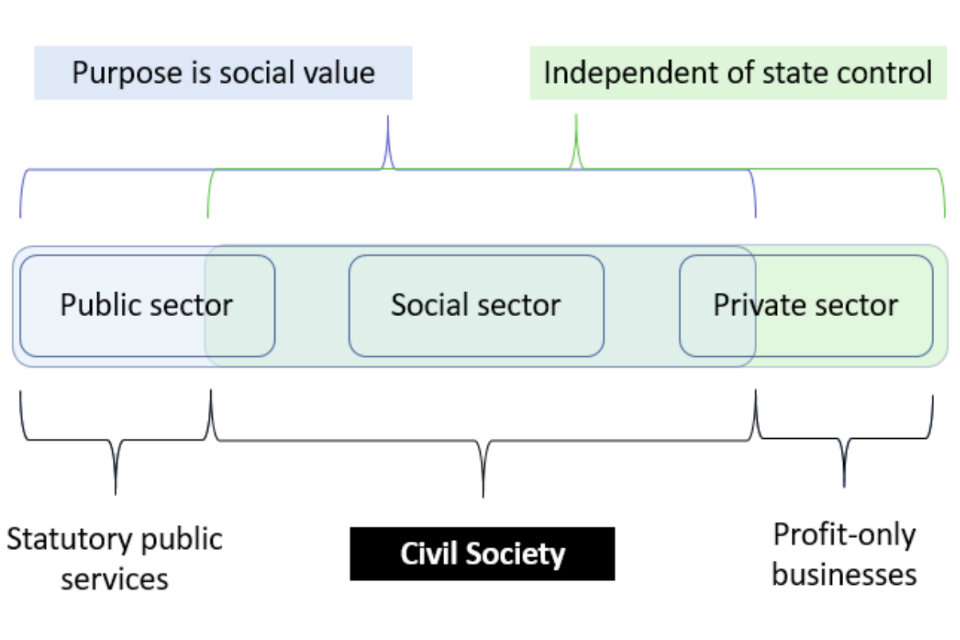

For the purposes of this Strategy, therefore, we define civil society not by organisational form, but in terms of activity, defined by purpose (what it is for) and control (who is in charge).

Civil society refers to all individuals and organisations, when undertaking activities with the primary purpose of delivering social value, independent of state control.

This definition includes the social sector of volunteers, charities and social enterprises. It excludes a lot of private sector and public sector activity - the private sector work for which the governing purpose is to deliver profits for owners, for example, or the public sector work delivered solely with statutory resources. But it includes parts of those sectors, as the following graphic illustrates:

As this suggests, it is not possible to draw precise boundaries around civil society without losing important aspects of it. The common definition of civil society as the ‘third sector’ not only demotes what is, in fact, older than both the modern state and the corporation; it also implies a tidy separation between spheres which overlap. These overlaps are where a lot of value lies.

Businesses are changing, to pursue social as well as economic purpose. The state is helping public service employees take control of their service through creating mutuals, reforming commissioning to support local and non-profit providers, and localising power. All of this is ‘civil society’ - not a sector, but a range of independent activity aimed at achieving social value.

In what follows we use the term ‘civil society’ in this hybrid sense, and ‘civil society organisations’ may be charities, public service mutuals, or businesses with a primary social purpose. To describe the ‘core’ of civil society we refer to ‘voluntary, community, and social enterprise organisations’, or simply ‘the social sector’.

Measuring success

The Civil Society Strategy sets out a clear intent from the government to enhance the strength of the five foundations, namely the work of people, places, the social sector, the private sector, and the public sector.

A desire for better impact measurement is already apparent throughout civil society and much work is done across different organisations and sectors to achieve this. Intentions and methods are often aligned and the government is keen to shape this thinking. As part of the Civil Society Strategy, the government will explore effective indicators to measure the strength and growth of the five foundations. We want to explore the best means of measuring the wellbeing of communities and the social value created, such as the positive outcomes that thriving communities deliver. However, there exists a significant knowledge gap in terms of what makes some communities thrive more than others, and how, for example, different resources and capabilities come together in different places. The government will explore options to develop an empirical and practical knowledge base for evaluating the financial, physical, natural, and social capital of communities.

To show the government’s ongoing commitment to the Civil Society Strategy, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport will give a biennial public update report on the ambition and commitments of the Strategy.

The document

Chapter 1 of this document focuses on the role of citizens in civil society and the importance of a lifetime of contribution to society, with particular reference to the role of young people. Chapter 2 presents a vision of ‘place’, and the role of government in supporting local communities. Chapter 3 explains the government’s approach to the core of civil society, referred to as the ‘social sector’, comprising charities, voluntary organisations, and social enterprises, including mutuals. Chapter 4 outlines the role of government in supporting the contribution of business, finance, and tech to civil society. Chapter 5 explains how the government sees the future role of civil society organisations in the delivery of public services.

The Strategy outlines a bold vision that will be realised over the long-term. This period will span multiple parliaments and government spending periods. The Strategy sets out numerous areas of interest and commits to exploratory work to shape the projects and programmes that will help to realise this vision. The emergence of new pieces of work will inevitably depend on the outcomes of this exploratory work and decisions taken at future reviews of spending with the agreement of all relevant departments.

Throughout the document are case studies and illustrations of the work done by government, business, and communities to strengthen civil society and create social value, as well as key messages and quotes we have heard throughout the engagement exercise.

We also feature short articles authored by ministers from across government, highlighting how a civil society approach is helping meet public policy priorities.