Consolidated budgeting guidance: 2025-26

Published 27 February 2025

Foreword

Context

This document sets out the principles and standards underpinning the budgeting system mandated for use by all bodies classified as central government, including departments, devolved governments, and arm’s length bodies. This budgeting system is a key part of the UK public spending framework. It enables the Treasury to control public spending, and appropriately incentivises departments to manage spending effectively.

Years of applicability

This budgeting guidance applies to in-year control from 2025-26.

Substantive changes to the guidance for 2025-26:

This section sets out the main areas where the guidance has been changed for 2025-26:

- Technical updates/clarifications have been made in the following areas:

- The guidance for budgeting for insurance contracts has been updated to reflect the implementation of IFRS 17 – Insurance Contracts across central government in 2025-26.

-

The guidance for the budgeting treatment of policy losses for financial transactions has been updated.

- Clarification on budgeting for profit and loss recognised in accounts on behalf of an associate.

- There are also other minor changes to clarify wording following comments received during the year.

Which bodies does this guidance apply to?

The budgeting guidance in this document applies to all bodies classified by the Office of National Statistics (ONS) to central government.

The sector classification of bodies assessed by the ONS is published in their Sector Classification Guide publication.

The Treasury also publishes a guidance note on sector classification. In broad terms, bodies are in central government if they are owned or controlled by central government bodies and they are not a Public Corporation (which is a separate ONS classification). A body will be controlled, for example, if the sponsoring department appoints a majority of board members.

Sometimes a lesser degree of influence can still be held to give control. The legal form of a body does not tell you what sector it is in. For example, if an Arms Length Body (ALB) sets up a wholly owned subsidiary in the form of a limited company under the Companies Act, that body would be classed as central government because it would be wholly controlled by the ALB.

Subsidiaries, interests in associates and joint ventures classified to central government are consolidated with parent bodies for budgeting. So, if an ALB sets up a public sector body that is not a public corporation, it will be part of the ALB’s DEL allocation from the parent department.

Departments and public bodies who are in doubt about an actual or proposed body’s sector classification should approach the Treasury for advice. The ONS should only be approached via the Treasury. That restriction on direct access to the ONS is so that the Treasury can:

- advise departments on the interaction of classification and policy (the ONS are independent and are not involved in policy formulation);

- consider the implications for budgeting of any proposal and;

- provide the right information to ONS in the right way, without lobbying, and respecting ONS independence.

Departments that are setting up a new body should contact the Treasury’s budgeting and classification branch with their proposals for budgeting, accounting and recording the body. The Treasury will pass the information on to the ONS, who will classify the new body.

The Cabinet Office has a separate process for classifying central government bodies for accountability and governance purposes, using their own criteria. Where departments are setting up a new body, they should also contact the Cabinet Office to discuss the governance arrangements. Throughout the rest of this document, the term ‘arms length bodies’ (ALBs) is used to refer to all bodies in a departmental boundary that have been classified as central government by the ONS and will not use the Cabinet Office-specific classifications (such as NDPBs or executive agencies).

Departments should not spend money on consultancy advice regarding national accounts sector classification and should discourage their sponsored bodies from doing so. Sector classification is unlikely to be an area where consultants have expertise. The Treasury will provide advice on request. Devolved governments are part of central government for ONS purposes.

1 Overview: Introduction to budgeting

This document sets out the principles and standards underpinning the budgeting system mandated for use in central government.

This chapter provides a general overview of the budgeting system. This includes an overview of:

-

the purpose of the budgeting system

-

the interaction between budgets and the public spending framework

-

the roles of budgeting system participants

-

budgetary categories

-

adjustments to budgets

-

policies that affect other departments’ spending

-

budget exchange

-

different presentations of total spending

Further chapters in this document provide guidance on the budgeting treatment for specific transactions. These chapters are organised by types of budgetary category or types of transactions.

Purpose of the budgeting system

The budgeting system set out in this document is the primary means by which HM Treasury controls public spending.

The budgeting system has two main objectives:

-

to provide a structure under which the Treasury can control public spending. This supports the government in realising its fiscal objectives, in return supporting macro-economic stability; and

-

to appropriately incentivise departments to manage spending effectively. This supports the provision of high-quality public services that offer value for money to citizens

Interaction between budgets and the public spending framework

The budgeting system is designed to support the UK’s public spending framework. It interacts with a number of different elements of the public spending framework:

-

fiscal policy and national accounts

-

departmental accounts

-

Supply Estimates (‘Estimates’)

-

cash requirements

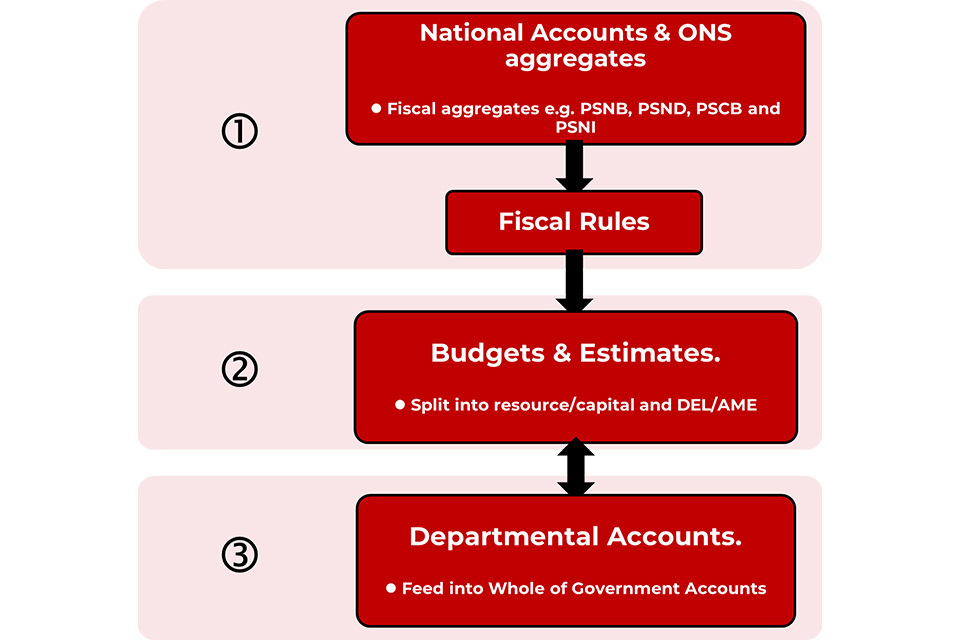

Diagram 1.A provides a visual overview of the public spending framework.

Chart 1.A: Public Spending Framework

Chart 1.A Public Spending Framework

The interaction between the budgeting system and each of these elements of the public spending framework is explained in more detail below.

Budgets, fiscal policy and national accounts

The budgeting system is designed to support the specific objectives for fiscal policy set by the government.

As confirmed at Autumn Budget 2024, fiscal policy decisions for at least this Parliament will be guided by the following mandate:

- The current budget must be in surplus in 2029-30, until 2029-30 becomes the third year of the forecast period. From that point, the current budget must then remain in balance or in surplus from the third year of the rolling forecast period, where balance is defined as a range: in surplus, or in deficit of no more than 0.5% of GDP

The Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is supplemented by:

- a target to ensure debt, defined as Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL), is falling as a share of the economy by 2029-30, until 2029-30 becomes the third year of the forecast period. Debt should then fall by the third year of the rolling forecast period.

To ensure that expenditure on welfare remains sustainable, the Treasury’s mandate for fiscal policy is further supplemented by:

- a target to ensure that expenditure on welfare is contained within a predetermined cap and margin set by the Treasury

At the current time, while balance sheet statistics are still being developed and analysed in the UK, the government’s approach will not be to target one specific metric but to aim to strengthen over time a range of measures of the public sector balance sheet such as public sector net debt, public sector net financial liabilities and public sector net worth through effective management of assets, liabilities and risks.

These targets are measured with reference to fiscal aggregates, including:

-

Public Sector Net Financial Liabilities (PSNFL), which is a wider measure of the balance sheet than public sector net debt (PSND), and includes all financial assets and liabilities recognised in the National Accounts. The differences from PSND are due to including additional liabilities (such as funded pensions obligations and standardised guarantees) and also net of both liquid and illiquid assets (such as equity holdings and loans)

-

Public Sector Current Budget Deficit (PSCBD), which is a measure of the difference between the government’s current expenditure (total expenditure excluding capital investment) and its current receipts (principally tax receipts), plus depreciation costs

-

Public Sector Net Investment (PSNI), which is a measure of the capital investment made by the government. This includes the acquisition of fixed assets (such as hospitals or other infrastructure), less any disposals, plus capital grants. This measure is presented net of public sector depreciation costs

The PSNFL and PSCBD aggregates, along with other fiscal aggregates, are aligned with national accounts concepts, which are a set of accounts showing economic activity throughout the UK, both in the public and private sector.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS), acting as an independent agency, prepares the UK’s national accounts in accordance with the ‘European System of Accounts 2010’ (ESA10) framework and the accompanying Manual on Government Deficit and Debt 2022 (MGDD). ESA 10 in turn is consistent with the System of National Accounts (SNA08), is an internationally agreed standard adopted by the United Nations and used globally. ESA10 and SNA08 provide a standardised international framework for preparing national accounts.

In summary, the budgeting framework supports the government’s fiscal objectives, which are measured using fiscal aggregates derived from the national accounts. Therefore, the budgeting rules, where possible, are consistent with the ESA10 framework used to prepare national accounts.

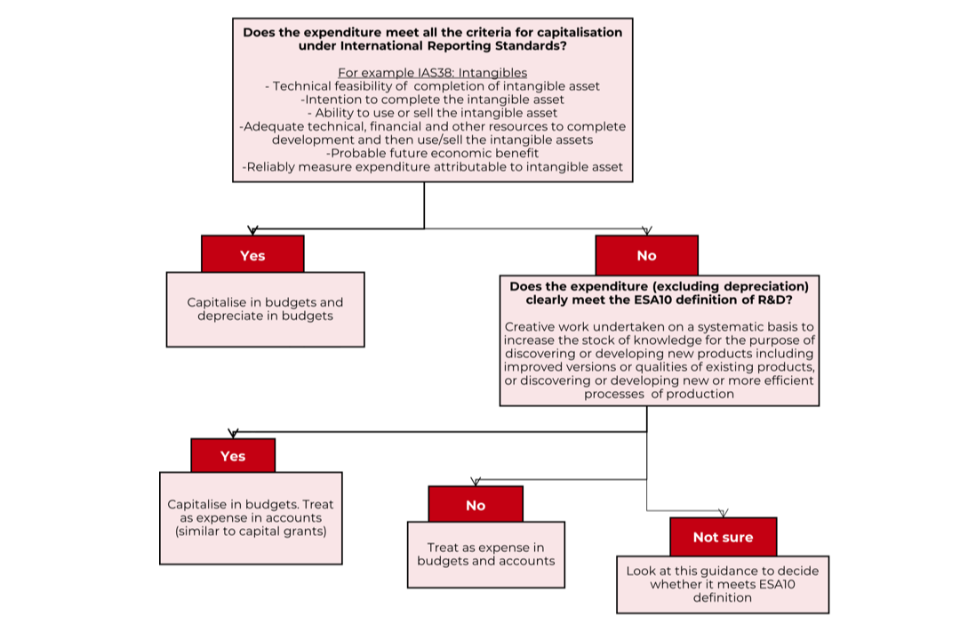

Budgets and departmental accounts

Departmental accounts are laid in Parliament and publicly available, audited, annual report and accounts that report how departments have used the resources at their disposal. They are based on International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as interpreted by the Financial Reporting Manual (FReM) (which is produced by the Treasury). The vast majority of transactions are treated in the same way in departmental accounts and national accounts: for example, pay is a current expense in any system of accounts.

Moreover, as part of the ‘Clear Line of Sight’ Treasury Alignment Project, the budgeting framework was amended to substantially align the treatment of transactions between budgets, Estimates and departmental accounts. Most of the spending by departments and their arm’s length bodies (ALBs) scores in the budgets and Estimates at the same value and with the same timing as in departmental accounts. This ensures that financial reporting is consistent, transparent, accurate and straightforward, and keeps compliance costs down for departments.

However, there are some differences between budgets and departmental accounts. Most of these differences are largely due to differences between the ESA10 framework (on which national accounts, and therefore budgets, are based) and the IFRS framework (on which departmental accounts are based). For example, ESA10 has different rules regarding the treatment of research and development costs as compared to IFRS.

Additionally, there are differences between budgets and departmental accounts where controlling spending against information in departmental accounts may not provide the right incentives for departments. Annex A lists the main differences between budgets and departmental accounts.

When there are differences between budgets and departmental accounts, Estimates will normally follow the budgeting treatment (see section on budgets and Estimates below).

Considering that budgets and departmental accounts are substantially aligned, it will likely be most cost-effective for departments to determine how to score a transaction for budgeting purposes in the following way:

-

start by considering the treatment of the transaction in departmental accounts

-

consider whether the budgeting treatment is the same as the departmental account treatment or different, and so establish the budgeting and Estimates treatment

-

as budgeting information generally feeds into national accounts, once you know the budgeting treatment and how it aligns with national accounts you can determine the fiscal effect of the transaction. This document spells out where budgeting information is not aligned to national accounts

In some places this budgeting guidance summarises or describes the accounting treatments in departmental accounts. This is done to provide context for the budgeting rules. However, the only authoritative description of accounting treatments is in the FReM.

Budgets and Estimates

Estimates are the mechanism by which Parliament authorises departmental spending. Estimates are generally presented using the budgetary framework in this document.

Estimates require Parliament to vote limits for different budgetary categories of spending, as well as any voted spending outside of budgets and the department’s Net Cash Requirement. These voted limits may differ from the figures in departmental budgets, as elements of the department’s budgets may fall within non-voted spending. The sum of voted and non-voted spending in Estimates will equal the figures in departmental budgets.

In the same way as budgets, Estimates are voted net of retained income. Generally, any income retained in budgets will net off against voted limits in the Estimate. This is discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

The Supply Estimates guidance manual contains full guidance on Estimates.

Budgets and cash requirements

The budgeting system is based on accruals accounting rather than cash accounting, consistent with both national accounts and departmental accounts. Accruals accounting provides a better basis for spending control, giving a more accurate picture of the expense incurred by a department in any period.

Cash is, therefore, not controlled directly through the budgeting system. Cash balances do not convey spending power and the availability of cash does not translate into budget cover.

However, cash is controlled elsewhere in the public spending framework. The Net Cash Requirement for Supply Expenditure is controlled through the Estimates processes. The concept of annuality is important in cash management; departments cannot carry forward cash from year to year. Departments need to return any unspent cash at the end of each financial year.

Changes in the expected level of use of cash provide useful monitoring information. For example, unexpected increases in cash outflows can serve as a trigger to check whether spending is rising above expectation. Departments should discuss the reasons for planned increases in the level of cash spending with their Treasury spending teams. The Supply Estimates guidance manual provides more guidance about the Net Cash Requirement and the process for returning cash.

Summary of the interaction between this guidance and other public spending framework documents

This document only provides guidance on the budgeting framework. As described above, there are a number of other documents that provide guidance on other areas of the public spending framework. Please refer to Annex E for a complete list of other areas of guidance. Some of the most important pieces of guidance are summarised below:

Table 1.A: Public spending framework documents

| Topic | Guidance |

|---|---|

| National accounts | European System of Accounts 2010 (ESA10) |

| Departmental accounts | Financial Reporting Manual (FReM) |

| Estimates | Supply Estimates guidance manual |

| Managing Public Money (i.e. guidance around accountability, governance, Parliamentary reporting responsibilities, etc.) | Managing Public Money |

Roles of budgeting system participants

There are two main participants in the budgeting system: departments and the Treasury.

Throughout this document, references are made to ‘departments.’ This document generally applies to devolved governments as well; however, some unique budgeting arrangements might be agreed between the Treasury and devolved governments. Further information on arrangements for the devolved governments is in the Statement of Funding Policy.

Role of the department

The budgeting system aims to ensure that departments have appropriate incentives to manage their business well, to prioritise across areas of spend, and to obtain value for money (as defined in the Green Book). Departments’ roles in improving spending control are further set out in Chapter 2, and in Managing Public Money.

Sometimes departments or public bodies commission consultants to offer them suggestions for ways around the spending control framework. The Treasury has no interest in such schemes. Departments are asked to go with the spirit of the spending control framework. If a transaction is clearly just a way around the letter of the rules, then departments should follow the spirit of the rules. If you are in doubt, talk to your Treasury spending team.

Role of HM Treasury

The Treasury is responsible for the design of the budgeting system and can offer advice and explanations in applying this system. It is only the Treasury which may finally determine the budgeting treatment of a transaction.

The guidance in this document cannot cover every case. Sometimes it is deliberately kept simple for departments because transactions are rare or typically small. There may be cases where if a large instance of such a transaction were to take place it would impact on the fiscal framework. In such cases the Treasury will sometimes impose restrictions, even if the guidance does not provide for them, to protect the fiscal framework or to provide better incentives for departments. If departments face new circumstances, which might lead to difficulties for the fiscal framework or where the budgeting is unclear, they should contact their Treasury spending team before they undertake the transaction.

Treasury ministers have the right to modify the budgeting guidance at any time, although in practice we try to keep changes to a minimum and consult departments before making significant changes.

Budgetary categories

The budgeting framework disaggregates a department’s budget into a number of different budgetary categories, each with its own control limit. These controls support the achievement of the fiscal framework and provide management incentives for departments. Each category, and the importance of spending control, is summarised below.

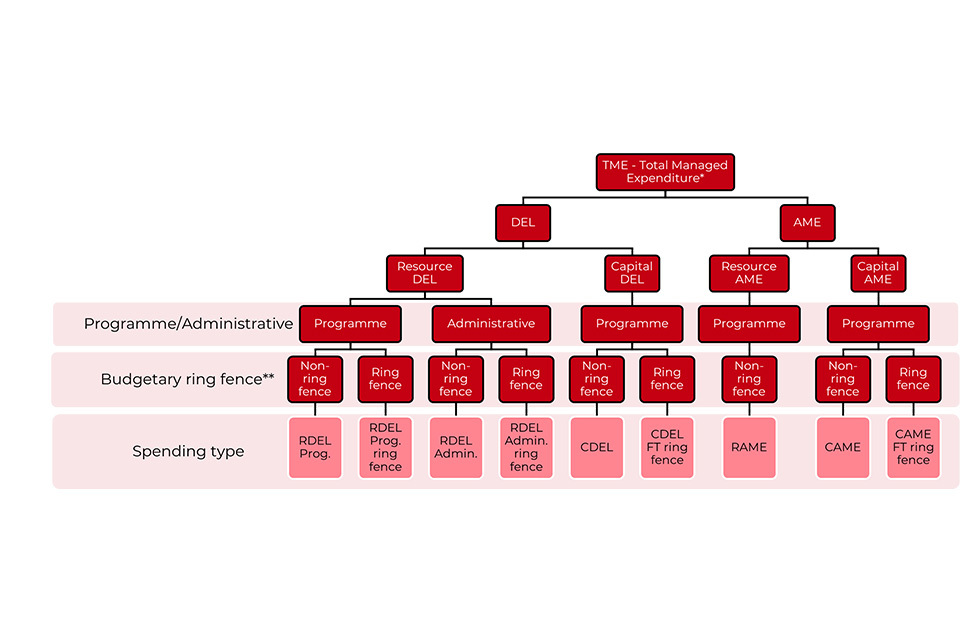

Chart 1.B provides an overall summary of the different budgetary categories.

Chart 1.B Budgeting Framework

*Total Managed Expenditure is made up of DEL and AME, plus accounting adjustments

** Budgetary ring fences (the depreciation and impairment resources budget ring fence and the financial transactions capital budget ring fence) are separate policy ring fences. Not all departments are subject to the financial transactions ring fences.

Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) and Annually Managed Expenditure (AME)

Departmental budgets are first disaggregated into two different categories:

-

Departmental Expenditure Limits (DEL) –this budgetary category captures spending that is subject to limits set in the Spending Review (SR). Departments may not exceed the limits that they have been set

-

Annually Managed Expenditure (AME) –this budgetary category captures spending that is subject to budgets set by the Treasury. Departments need to monitor AME closely and inform Treasury if they expect AME spending to rise above forecast. Whilst Treasury accepts that in some areas of AME inherent volatility may mean departments do not have the ability to manage the spending within budgets in that financial year, any expected increases in AME require Treasury approval

Within both DEL and AME, departments are expected to pursue efficiencies and prioritise expenditure in order to optimise value for money (as defined in Box 18 of the Green Book).

The combination of the resource/capital budgetary categories (described below) with the DEL/AME categories gives rise to a number of separate budgetary control and planning totals (for example capital DEL, resource AME). Departments and their Treasury spending teams should at all times have a shared understanding of what the control and planning totals are and how the department’s spending matches up against them. See Chapter 2 for a more detailed discussion of tracking control and planning totals.

Appendix 2 to this chapter sets out the budgetary categories diagrammatically. Appendix 3 sets out a list of a department’s control and planning totals.

Criteria for treatment in DEL or AME

The following paragraphs provide a brief overview of whether transactions should be recorded in DEL or AME.

Generally, all areas of spend are in DEL unless the Chief Secretary of the Treasury has determined that they should be in AME. The Chief Secretary may agree to put areas of spend into AME if:

-

they are not only demand-led but also exceptionally volatile in a way that could not be controlled by the department and where the areas of spend are so large that departments could not be expected to absorb the effects of volatility in their DELs (for example, most welfare spending) or

-

for other reasons, they are not suitable for inclusion in firm multi-year plans set in the SR. For example: lottery spending funded by the National Lottery which may not be reprioritised elsewhere. Certain levy-funded bodies, which serve particular industries, are also in AME – Appendix 4 to this chapter sets out the criteria determining whether levy-funded bodies should be in AME

Additionally, transactions may score in AME when they do not have an immediate impact on the fiscal aggregates (for example, revaluations or provisions). This document provides detailed guidance for these transactions.

The Treasury regularly reviews whether areas of spend in AME are still suitable for AME treatment. Where appropriate these are moved into DEL.

Normally, an area of spend will have both its resource and capital budget impact in either DEL or AME, but there are some exceptions. Where a department agrees an exception with Treasury it should be included in their settlement letter during the SR process.

Resource and capital budgets

In addition to being split into DEL or AME, departments’ budgets are also split into resource and capital categories.

-

Resource budgets capture current expenditure (including depreciation, which is the current cost associated with fixed assets). It is paramount for Treasury to retain control over the level of current spending. Within the resource budget some transactions will have an immediate or near-immediate impact on fiscal aggregates, for example pay and procurement. Other transactions will only have an effect in future periods, for example the take-up of provisions. Resource budgets are discussed further in Chapters 3 and 4

-

Capital budgets capture new investment and financial transactions. It is important to control capital budgets alongside resource budgets because spending in this budget increases public sector net debt and government’s borrowing requirements. Capital budgets are discussed further in Chapters 6 and 7

Programme and administration budgets

Resource budgets are further split into programme and administration budgets.

-

Programme budgets capture expenditure on front line services

-

Administration budgets capture any expenditure not included in programme budgets. They are controlled to ensure that as much money as practicable is available for front line services. Administration budgets are discussed further in Chapter 5

Types of adjustments to budgets

Budgetary limits in each budgetary category are set at each SR. However, there can be subsequent adjustments within or between these budgetary limits. These adjustments fall into three categories. In summary:

-

Policy/plan adjustments reflect deliberate decisions by departments to increase or decrease spending in a particular policy area, or in the way a policy is delivered (for example introducing a charging regime). These represent ‘real world’ changes in spending or plans. There are restrictions on the adjustments that departments can make to budgetary limits in this area; this is discussed further below

-

Classification adjustments reflect changes in budgetary totals driven by changes in the way spending is classified rather than by actual changes in the level of spending. For example, changes in IFRS accounting standards or ESA10 national accounts standards that are implemented in the budgetary framework are classification adjustments. Classification adjustments also include Machinery of Government changes where responsibility for spending moves from one central government body to another. Accounting policy changes – whether driven by the department or by the National Audit Office – also count as classification changes; note that accounting policy changes need the agreement of the Treasury

-

Inter-departmental adjustments/budget cover transfers reflect changes in spending plans as a result of an agreed transfer of budgetary cover from one department to another. Examples of where a transfer is appropriate include where there is an allocation from a ‘shared pot’, or when a department agrees to transfer cover to another department to cover costs incurred as a result of a change in policy

The changes are implemented in different ways in budgets:

-

Departments are expected to accommodate the effects of policy/plan adjustments in their budgets, making offsetting reductions in spending

-

classification adjustments lead to budgets being restated, normally across all the open years on the Online System for Central Accounting and Reporting (OSCAR) system

-

inter-departmental adjustments/budget cover transfers lead to restated limits of the departments concerned

In addition, departments may record changes to their expenditure numbers as budgetary outturn adjustments, which are not a change to the budget – they are used to describe changes against final budget allocations and are used for recording outturn.

It is the Treasury that ultimately determines what type of adjustment a change is. Departments that are in doubt should contact their Treasury spending team.

Annex E sets out where to find further guidance on types of adjustment. Appendix 4 to this chapter provides more guidance on Prior Period Adjustments, i.e. adjustments to budgets in prior periods.

Policy/plan adjustments and ‘switching’ across categories

As stated previously, departments are expected to accommodate policy/plan adjustments (which are real-world changes in spend) in their existing budget limits. One way they can achieve this is if spend increases in one area of a budgetary category (for example, capital DEL), a department can reduce spend in another area of that same budgetary category. Another way of accommodating policy/plan switches is to ‘switch’ budget provision from one budgetary category to another.

So that control totals are effective, departments are restricted in the switches they may make between budgetary categories:

-

departments may not switch provision from AME to DEL. Departments may not exceed the DEL limits set in each SR; they cannot avoid exceeding these limits by switching provision from AME to DEL. Where the actions/inaction of a department increase AME, they are assumed to fund the increases in AME by reductions in their DEL budgets

-

departments may not switch provision from capital budgets to resource budgets; such switches would mean that money that had been earmarked for investment was used for current spending. It is paramount for Treasury to retain control over the level of current spending via the resource budget; this control should not be risked via switches from capital to resource budgets. Departments may switch provision from resource budget DEL to the capital budget DEL but not from ring-fenced elements of those budgets

Departments are expected to manage their resource budget DEL as an integrated whole, optimising spending across different areas (including areas managed by ALBs and those involving Public Corporations). In order to encourage value for money and to support achievement of the fiscal framework, there are some general restrictions on the freedom to move provision across resource DEL:

-

departments may not switch from programme budgets to administration budgets. Such switches would mean increasing provision for back-office or policy staff at the expense of frontline staff and programmes. Departments are free to switch provision from administration budgets to programme budgets

-

depreciation and impairments of fixed assets are ring-fenced within resource DEL (or exceptionally resource AME) and budget cover may not be reprioritised from within the ring-fence. Departments may freely switch provision from outside of the ring-fence to depreciation and impairments costs

-

finally, there are also restrictions on switching into and out of support for local authorities

To relax any of the above restrictions could impact on the government’s fiscal mandate or its administration costs target and would therefore need to be absorbed by the Reserve (see Chapter 2). For this reason, any request to waive the above restrictions is viewed in the same way as a request for support from the Reserve and the same process (which is outlined below) will be followed. Note that requests to switch budget cover out of the resource DEL depreciation ring-fence will not be approved.

In addition, as part of the SR settlement or through subsequent agreement, some spending might be subject to specific policy ring-fences. If so, departments may not move money across these ring-fences, except as specified in their SR settlement. Ring-fences are normally set at the level of resource DEL or capital DEL. However, closer controls (for example on administration spending) may be set.

Policies that affect other departments’ spending

One department’s policies may affect the spending of another department. Sometimes the link is obvious, for example where several departments have joint responsibility for a change to outcomes. In other cases, the link may be less clear: for example, the creation of a new offence may impose burdens on the police, prosecutors, legal-aid, and offender-management budgets.

There is a long-standing set of general principles governing the question of policy changes with resource implications affecting more than one department. These include:

-

any department proposing new policies, in whatever context, must always quantify the effects on public expenditure prior to a policy decision being made. In doing so, it must assess the effects not only on its own spending but also on the spending of other government departments, the devolved governments for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and local authorities

-

decisions on how to finance a new proposal must be taken simultaneously with the policy decision. It is for the department proposing a change to consult those concerned (including the Treasury and any other departments for which there are dependencies that could have spending implications) and agree new policy, including the finance of that policy, before a proposal goes forward for collective consideration

-

the agreement on financing the downstream costs of new policy on another department may provide either that the costs be met by the originating department or that they be met by the department on which those costs fall

-

in the absence of explicit agreement to the contrary, the normal presumption is that the originating department will absorb the cost

-

where consultation has not taken place, the default is that all costs, including those affecting other departments, will be absorbed within existing budgets by the department responsible for the policy change that creates additional costs. The Chief Secretary will not consider any requests to provide further funding for pressures which arise as a result of consultation not taking place

-

where the originating department absorbs the cost, it should make budget transfers to affected departments covering the whole of the SR period

-

where the costs fall, or come fully on stream, in the next SR period, it is for the department(s) that will meet the costs to conduct the SR discussions with the Treasury on funding in the next SR period. Where that department is the originating department, it should make budget transfers after the conclusion of the SR

-

these arrangements include cases where a department’s policies impact on the AME spending of another department. The originating department may be expected to make DEL offsets to cover increases in AME spending

-

Treasury agreement is needed for all new policies with expenditure implications (see Managing Public Money). However, the Treasury does not arbitrate between departments on the question of who should bear downstream costs and will not provide funding where no agreement has been reached

Where a department introduces a policy that benefits another department, it may seek a contribution to the costs to the implementation of that policy, and this should be explored ahead of any policy decision. Cost-sharing may only be appropriate in some circumstances, but discussion between departments to understand potential benefits, costs and dependencies should support improved spending and policy decisions. This is to be agreed between affected departments and again the Treasury will not arbitrate.

The budget consequences of any new proposals, regardless of where they originate, fall to the department responsible for implementing the proposals.

Charging for services

Where a department introduces charges for a service previously provided for free or moves from a subsidised service to full cost recovery, it should normally transfer DEL cover to any customers in the central government sector to leave them no better and no worse off.

New burdens on local authorities

Where a department wishes to impose additional burdens on local authorities, it is responsible for securing the necessary resources and fully funding them. A new burden is defined as any policy or initiative which increases the cost of providing local authority services. This includes duties, powers, or any other changes which may place an expectation on local authorities, including new guidance.

The policy applies to any new burden imposed on local authorities (including police and fire authorities) except for policies which apply the same rules to local authorities and to private sector bodies (for example a change in the rate of employers’ National Insurance contributions).

Departments contemplating a potential new burden should contact the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) at the earliest possible stage to discuss the procedures to be followed – newburdens@communities.gov.uk

Transactions between departments

Transactions between public sector bodies should be constructed simply. For example, where Department A buys an asset from Department B, the purchase price should normally be paid in full in cash on the day of completion. Departments should not enter into or spend money on complex deals which do not have a clear justification in fairness or incentives as these are unlikely to be good value for the public sector overall. Departments should not seek to exploit differences in budgeting rules between different public sector entities. Where departments are unsure how best to construct a transaction with a public sector body they should consult the Treasury.

Budget Exchange

Budget exchange is a mechanism that allows departments to carry forward a forecast DEL underspend from one year to the next. Budget exchange provides departments with flexibility to manage their budgets, while strengthening spending control and providing greater certainty in order to support effective planning.

Under budget exchange, departments may return a forecast DEL underspend in advance of the end of the financial year (by means of a DEL reduction in the Supplementary Estimate) in return for a corresponding DEL increase in the following year, subject to a prudent limit.

There is no scope to carry forward underspends that are not forecast in advance of the Supplementary Estimate.

Departments may not generally carry-forward an underspend if they are simultaneously seeking to draw funds from the Reserve (the Reserve is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2). As always, Reserve support is subject to an assessment of need and so emerging underspends should be deployed to meet pressures before additional funding is sought. For example, a department with a capital pressure and a resource underspend should not seek to Budget exchange the latter. Budget exchange is available on all DEL control totals (including non-voted DEL). This is subject to the usual restrictions on switches discussed in paragraphs 1.60-1.64.

Separate arrangements apply to the devolved governments.

Approval process

Treasury approval is required for any increase to DELs. However, it is intended that approval to utilise budget exchange will be granted automatically up to a prescribed limit and subject to the other conditions detailed below, though Treasury reserves the right to withhold approval in exceptional circumstances.

The amounts that departments will be permitted to carry forward are set out in the table below, where the limit is expressed as a percentage of resource DEL and capital DEL in the year in which the underspend is forecast to occur. These limits vary by size of department in recognition of the difficulties faced by smaller departments in managing slippage between years and there are separate limits for resource DEL and capital DEL.

Table 1.B: Separate arrangements apply to the devolved governments

| Size of Department | RDEL Limit | CDEL Limit |

|---|---|---|

| Total DEL[1] less than £2billion | 2% | 4% |

| Total DEL greater than £2billion but less than £14billion | 1% | 2% |

| Total DEL greater than £14billion | 0.75% | 1.5% |

[1] Where total DEL = Resource DEL excluding depreciation + Capital DEL

Resource DEL carried forward through budget exchange may not be switched between administration and programme budgets or between the ring-fences.

Preventing the accumulation of spending power over time

To further ensure that the fiscal cost of budget exchange is manageable, and that spending power is not allowed to accumulate over time, budget exchange will only be permitted from one year to the next. This works by any carry-forward from the previous year being netted off the amount that can be carried forward into the next year. A worked example is shown below for a department with £1 billion DEL each year:

-

in year one the department forecast an underspend of £20 million. It reduces its year one DEL to £980 million and increases its year two DEL by a corresponding amount to £1,020 million

-

in year two the department forecasts an underspend of £30 million (against its new DEL of £1,020 million). It reduces its DEL by this amount, to £990 million. However, the amount brought forward from year one must be netted off the amount that the department is allowed to carry into year three. Therefore, the department is only allowed to increase its year three DEL by £10 million to £1,010 million

-

in year three the department forecasts an underspend of £10 million (against its new DEL of £1,010 million) and reduces its DEL by this amount, to £1,000 million. However, it cannot carry anything forward to year 4 as the £10 million carried over from year two is netted off

In the above example, we assume all other budget exchange rules are in effect.

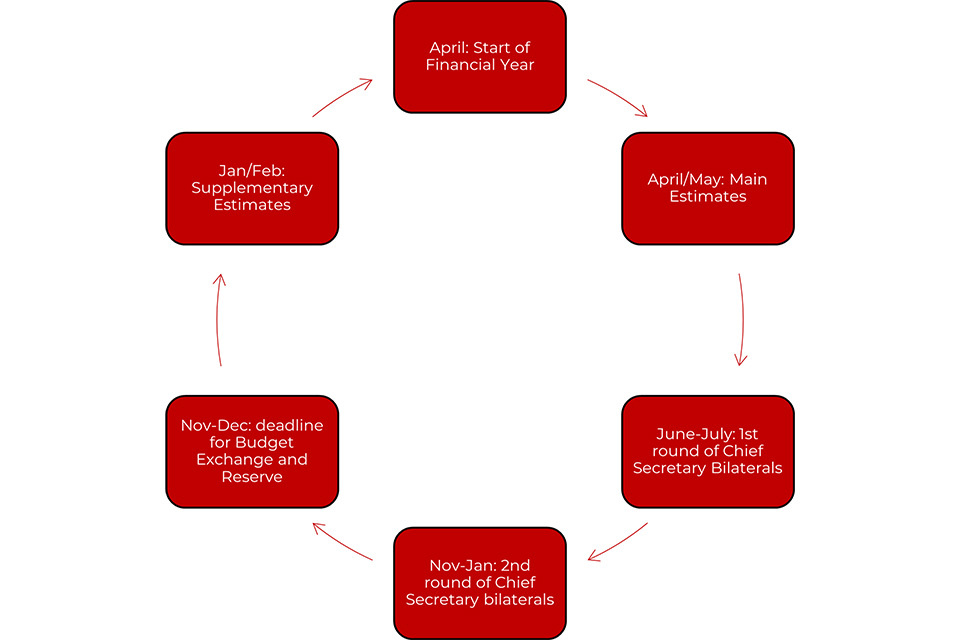

Timing

The budget exchange process is run to a Supplementary Estimates timetable. The exact timing will be confirmed in a Public Expenditure System (PES) paper ahead of the Supplementary Estimate, but it is likely that departments will need to inform the Treasury of the amounts that they wish to carry forward by late November/early December.

The in-year DEL reductions will be reflected in the Supplementary Estimate, with the corresponding DEL increase awarded at the time of the Main Estimate the following year.

Overspends

There is no scope to change DELs after the Supplementary Estimate. Any department that uses budget exchange and then subsequently breaches a DEL control total will be treated like any other overspend and will be subject to the same process outlined in Chapter 2. Departments will need to take this into consideration when making a budget cover return for a forecast underspend. Departments are under no obligation to return their entire forecast underspend.

Flexibility for managing large capital projects

Managing large projects can pose significant challenges to departments, who currently have to manage spending within annual budgets which may have been set several years before the start of the project.

To recognise this challenge, departments are offered greater flexibility to carry-forward capital DEL underspends related to significant investment programmes:

-

to qualify for additional flexibility, the programme must have a capital DEL budget of over £50 million in the year in question

-

carry forward will not count towards the standard capital DEL budget exchange limits, but may not exceed 20% of the programme’s capital DEL budget in the year from which it is being carried forward

-

carry forward may be spread across multiple years

-

this will be subject to the following conditions:

-

the Treasury will consider each application on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the overall value for money of the programme and the likelihood of successful project delivery being enhanced by the carry forward. Departments will be expected to provide evidence to support their application

-

the programme in question must continue to be delivered to the originally agreed timescale

-

departments must notify their Treasury spending team 6 weeks ahead of the Supplementary Estimate if they wish to take advantage of this flexibility, to allow time for the effect on the fiscal aggregates to be assessed

Flexibility for the retention of income from asset sales

It can be challenging for departments to match asset-sale proceeds with capital expenditure perfectly on an annual basis. Therefore, departments will automatically be allowed to carry forward the capital DEL proceeds from the sale of surplus property assets (i.e. assets no longer serving a policy purpose), in line with any asset disposal targets. Departments can retain 100% of capital DEL proceeds from asset sales, up to 1.5 times their target and 50% between 1.5 and 5 times the target. Further guidance on the scoring of asset disposal proceeds, including on the treatment and retention of resource DEL profits/losses recorded as a result of the sale, is covered in Chapter 4.

Departments manage a range of asset types which are held for policy purposes, such as financial assets, investments in public corporations, and fixed assets. Departments should regularly review assets on their balance sheets and explore potential for disposals where assets are surplus or where there is no longer a public interest rationale for ownership. In addition to the flexibilities on surplus property assets above, the Treasury will welcome proposals from departments regarding flexibility to carry forward a proportion of the capital DEL proceeds from other asset sales across multiple years. The flexibility will be considered on a case-by-case basis, subject to the following conditions:

-

For sale of fixed assets, the department can demonstrate clearly that it has approved capital projects in subsequent years on which to spend these receipts

-

the asset sale in question must have been completed before budgets will be adjusted and

-

receipts may not be switched between the general and financial transaction capital DEL boundaries, without prior agreement from the Treasury.

In some cases, departments may prefer to share the resource benefit that results from the Exchequer using asset-sale proceeds to pay down debt and hence reduce interest payments. Therefore, instead of keeping the proceeds from a fixed asset sale, departments may return the proceeds in full to the Exchequer in exchange for a resource DEL uplift equivalent to 3.5% of the proceeds returned. This would be a non-baselined uplift in each year of the period for which resource DEL budgets had been set. The Treasury will consider each application on a case-by case basis.

In order that the Treasury can monitor the overall effect of these policies on the fiscal aggregates, departments should notify their Treasury spending team 6 weeks ahead of a fiscal event if they envisage using either of these flexibilities on asset sales in that financial year.

These flexibilities do not affect any other rules around the retention and utilisation of asset sale income.

For areas of protected spend, the Treasury may not be able to offer the asset-sale flexibilities above. Departments should discuss asset sales in areas of protected spend with their Treasury spending team directly.

Cascading Budget Exchange

Departments are responsible for deciding whether to cascade budget exchange, or an alternative system for carrying forward underspends, to their ALBs. Departments will be responsible for managing any pressures this would create within their DEL.

Presentation of total spending

Budgetary information can be used to present figures about central government spending in a number of different ways. The primary budgetary presentations of spending are summarised below.

Total Managed Expenditure

The government’s main measure for reporting overall public spending is Total Managed Expenditure (TME), a measure drawn from the national accounts. TME may be defined as the sum of the public sector’s current and capital expenditure. Current expenditure is presented net of sales of goods and services while capital expenditure is presented as net of asset sales.

The composition of TME is discussed in more detail in the Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (PESA) document.

Resource and capital budgets

A department’s resource budget is the sum of resource DEL and resource AME. The capital budget is the sum of capital DEL and capital AME.

Neither the resource budget nor the capital budget is a control total, since departments may not make switches from AME to DEL. They are still useful numbers to present since they show the total current and capital spending in the budgets of the department.

Total DEL

In addition to the control totals, there is a presentational aggregate; Total DEL. Total DEL is not a control total. It is a standard way of showing total current and capital spending in DEL. It is defined as:

-

resource budget: DEL

-

plus capital budget: DEL

-

less depreciation in DEL

Depreciation here includes DEL impairments.

Depreciation is excluded from total DEL because adding together depreciation and investment may be seen by some as double counting the cost of assets.

Tax impacts on departmental budgets

Budgets will not be changed as a result of changes in tax treatment. This includes where the Chancellor announces tax increases at a fiscal event that impact on departments.

Appendix 1 to Chapter 1: Summary content of budgets

This table summarises the main standard contents of resource and capital budgets.

Table 1.C: Contents of budgets

| Resource budget | Capital budget | |

|---|---|---|

| Department’s own transactions with the private sector | Expenditure on an accruals basis, including administration costs, pay, superannuation liability charges and other pensions contributions or current service pensions costs, grants to individuals, subsidies to private sector companies. Take up of provisions, movements in value of provisions, and release of provisions (as well as the expenditure offset by the release of the provision – except provisions related to capital expenditure). Profit/loss on disposal of assets. Depreciation and impairments on the department’s assets. Less income retained in DEL/AME, for example sale of services. Note: Excludes revaluations charged to revaluation reserve. | Expenditure on new fixed assets on an accruals basis; includes leases and other transactions that are in substance borrowing (i.e. on-balance sheet PPP deals). Less Net book value of sales of fixed assets. Net policy lending to the private sector. Capital grants to the private sector. Research and Development expenditure (per ESA10) |

| ALB transactions with the private sector | As the department. Note: the department’s grant in aid to ALBs is excluded from budgets. | As the department |

| NHS Trusts (England) | As the department | As the department |

| Support for local authorities | Current grants to local authorities | Capital grants to local authorities Supported Capital Expenditure (revenue) |

| Public Corporations | Subsidies paid to Public Corporations. Less interest and dividends received from Public Corporations | Investment grants paid to Public Corporations. Net lending to Public Corporations (Voted and NLF). Public Corporations’ market and overseas borrowing (including on balance sheet PPP). Less equity withdrawals from Public Corporations |

Appendix 2 to Chapter 1: The department’s control and planning totals.

Departments and their Treasury spending teams should at all times have a shared understanding of what their control and planning totals are, whether the department’s spending is on track to stay within limits, and what the risks are.

The control totals are:

-

resource DEL (broken down into the non-ringfenced and depreciation ringfenced budgets)

-

administration budget

-

capital DEL (for some departments, broken down into the non-ringfenced and financial transaction ringfenced budgets)

-

any department-specific policy ring-fences

The planning totals are:

-

resource AME

-

capital AME

Appendix 3 to Chapter 1: Criteria for AME treatment of levy-funded bodies

The Chief Secretary has determined that the spending of a number of levy-funded bodies should be in AME rather than DEL. The Chief Secretary takes such decisions case by case using the criteria below. The AME treatment of individual bodies is kept under review.

Where an AME treatment has been approved for spending, the income from the levy must also be recorded in AME by the body.

While the Treasury has no plan to recommend to the Chief Secretary that any further levy-funded bodies should have AME treatment, the criteria that the Chief Secretary uses are set out below.

| Box 1.A: Criteria for deciding whether a levy-funded body should score in AME |

-

the body should in broad terms provide services (“services” could include a compensation fund) to an industry or group of industries or the workforce in that industry

-

the body should be wholly or mainly funded by a levy on the industry. There should be substantial industry consensus involved in the setting of the levy or the direction of the expenditure or both

-

the expenditure must be suitably ring-fenced. Normally, that would mean that the whole body should fall into this category

-

the body should be self-financing in cash terms. With no recourse to departmental grants or subsidies. Where, exceptionally, grants or subsidies are paid, the expenditure funded by those grants would score in DEL

-

draw-down of reserves should be permitted and normal short-term modest size overdrafts. But the bodies should not normally borrow long term. Where, exceptionally, borrowing other than short-term overdrafts, finances expenditure, it would normally score in DEL

-

the body should meet relevant efficiency and other criteria:

-

the licence or levy is appropriate, i.e. applied in the economically most advantageous way in the circumstances

-

introducing the levy or licence should not materially restrict the government’s fiscal policy

-

there should be adequate efficiency regimes in place to keep costs down, including stretching targets and regular efficiency reviews

-

suitable arrangements should exist to prevent the body from abusing its power to set the level of the levy. For example, the levy might need approval by the minister

-

there will be periodic reviews involving the Treasury of the operation of the levies, including whether they should exist at all, what scale of activity is appropriate, and the level of charges set

-

Appendix 4 to Chapter 1: Prior Period Adjustments

Prior period adjustments (PPAs) are adjustments where data for an earlier year needs to be restated. PPAs are primarily an accounting concept. They negate the need to re-open accounts where a material error or omission is found from previous years, or where a department makes a material change to its accounting policies. All PPAs should be discussed with the auditor at the earliest possible opportunity.

PPAs in Estimates

Although PPAs are primarily an accounting concept, they also impact Estimates. From an Estimates perspective PPAs fall into two categories:

-

a restatement of outturn data following a change in accounting standards or other changes to accounting policy outside the department’s control or

-

the correction of an error or omission in the previously recorded data, or a change in accounting policy under the department’s control

Where a PPA results from a change in accounting standards, this is treated as a classification adjustment for budgets. There is therefore no need to seek Parliamentary authority, but the change and its impact should be identified in “Note F Accounting Policy changes” in the next available Supply Estimate.

Where a PPA results from the correction of an error, or a department’s choice to change accounting policy, it has the potential to change net budgets and thus the reported outturn for previous years. In such cases the Treasury believes it is proper that Parliamentary authority is sought for the budgetary cover that should have been sought previously had the expenditure been identified correctly. Such PPAs must therefore be included as non-budget expenditure in an Estimate.

This is required even when the department was in a position to fund the expenditure from budget cover if it had been recognised in the correct year initially (i.e. there were underspends in previous years).

PPAs can only be made for genuine errors, omissions, or changes in accounting policy. Estimates non-budget cover is only appropriate for known and costed PPAs that have been discovered at the time of preparing the Estimate. It follows that non-budget cover should not be sought for potential PPAs.

Materiality

There is no such concept of materiality in budgets (the database goes down to the nearest £1,000). If the NAO have accepted at the time of the preparation of the annual report and accounts that a PPA is not material in accounting terms, they may propose that the PPA is absorbed in that year’s budgetary outturn. HMT will not contest that decision.

Excess Votes

Normally departments do not have any non-budget provision unless a genuine PPA is identified before the Supplementary Estimates are finalised. If the need for a PPA is discovered whilst departmental accounts are being compiled, it will be allocated to the non-budget section of the Statement of Parliamentary Supply (SoPS). The PPA should reflect the prior-year data only but capped by the start of resource accounting in government (i.e. departments should not seek cover for events prior to 2001-02, the first full year of resource accounting).

If there is insufficient non-budget provision in the Estimate for the PPA, then it will lead to an Excess Vote. The normal process for regulating Excesses will then be followed.

Negative PPAs: no need for approval

Whilst it is possible to have negative PPAs in accountancy terms, Supply does not require Parliament to approve a smaller number. Parliament approves a ceiling for expenditure against which departments are judged; it has no need to vote something which is already within an approved limit.

Re-recording budgets on the database

Once the year in which the PPA features has passed, departments should re-state budgets to reflect the corrected budgetary outturn (DEL or AME, resource or capital) in the years affected on the OSCAR database. Note that the database will only hold outturn for five previous years; any impact beyond that cannot be captured electronically but should be reported in the departmental accounts and noted in the Estimate.

Appendix 5 to Chapter 1: Machinery of Government Change (MOG)

A Machinery of Government (MOG) change occurs when there is a transfer of function between one (or more) government departments and there is a resulting change in the Departmental Accounting Officer responsibility. Departments should begin the process of agreeing amounts and budgets to be transferred as soon as a MOG has been announced. In accounting a MOG change would be treated as a ‘Transfer by Merger’. Departments should refer to the MOG guidance, but should be aware of the following key points when reflecting a MOG change:

-

a MOG in isolation should not affect the spending power of either the transferring or receiving department (i.e., no department should be left better or worse off as a result of the transfer of the budget)

-

the transfer must completely net out between the two (or more) departments, (for example DEL budget being transferred by one department must be recorded as DEL by the receiving department). Each department involved in the MOG should ensure that the information being provided by them is checked and agrees with that being provided by the other department to ensure that information provided is complete, consistent and correct

-

should the function (following the transfer) require provision in excess of the amount being transferred, the additional provision will not be part of the MOG, and the receiving department may seek additional budget. As normal, access to the Reserve will only be given in exceptional circumstances.

The Accounting Officer in the transferring department will have formal responsibility for the transferred function up until the relevant Supply Estimate and related legislation has received Parliamentary approval. From that point onward, the Accounting Officer in the receiving department will be fully accountable for the transferred function (i.e. not only in the current and future year but also for the historical period). It is therefore essential that the Accounting Officer in the receiving department seeks assurance about the values of transferred items and that they receive all documentation relating to the function from the transferring department.

Other transfers of functions within the public sector, for example, transfers between ALBs within a single departmental group, (regarded as transfer by absorption in accounts) will not require historic restatement. The net impact of assets and liabilities transferring should not affect the spending power of the transferring or receiving department. The FReM provides further guidance on the accounting treatment for all business combinations under common control.

2 Spending Control

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the overall spending control framework that allows the government to manage public money effectively. The budgetary framework is an important part of spending control.

At a high level, spending control is achieved through robust spending plans, set at Spending Reviews (SRs), and supported by a framework for delivering the government’s priority outcomes. Delivering these plans requires efforts in each of the following areas:

-

Monitoring spending: ensuring there is accurate and timely management information about what is being spent in all parts of the public sector. This allows the government to monitor progress and intervene when plans go off track

-

Managing spending: improving capacity and capability to manage spending and ensure that efficient and sustainable choices are made about how public funds are used. This requires systems and processes that allow the government to act to mitigate risks, and where risks do materialise, managing them within the spending limits set at SRs

-

Delivering priority outcomes: ensuring that policy proposals are aligned to priority outcomes based on evidence of what works, there is a plan for prioritising key outcomes, aligning activity towards delivering them and using data on progress against priority outcomes to drive improved delivery

-

Governance, scrutiny and oversight: from those responsible for managing public money at Ministerial and Official level and on Departmental Boards, to ensure that progress and practice is regularly reviewed and challenged

Each of these areas is summarised in this chapter, with a summary checklist at the end of each section for departments to consider. Additionally, refer to the Government Finance Function Strategy document for more detail on how efforts are being made to improve each of these areas across government and the finance functional standard for more detail on the expectations for a high performing finance function.

Monitoring spending

The public sector, on behalf of the citizens, manages over £900 billion of public spending a year. It is essential that the government has good information about what it plans to spend, and what it actually spends. This information should be:

-

Robust and reliable: so that data is accurate, and forecasts are as good as they can be

-

Consistent: within and between organisations and

-

Timely: so that data is provided on a monthly basis and with minimum delay

This is a prerequisite for effective spending control and is the kind of information that any well-run organisation should have in any case. It enables the government to monitor spending; intervening where necessary to ensure the government delivers its plans.

All organisations that are part of the central government have the same responsibilities to produce and share robust, timely financial information to support the management of the public finances. Working with the Treasury, departments should agree with their ALBs how this need will be met. This duty is entirely consistent with the freedoms and flexibilities that departments and ALBs have to manage their money.

Departments and devolved governments provide financial information to the Treasury via the Online System for Central Accounting and Reporting (OSCAR).

This information is published in a number of reports for Parliament and the public, providing the main source of central government expenditure data for the Budget, Supply Estimates, Public Expenditure Statistical Analyses (PESA), monthly Public Sector Finances and the national accounts.

Additionally, this information should be used in evaluation plans for new and existing programmes of spend (discussed in more detail below).

The Government Finance Function has also established a set of principles for the design of reporting processes, systems and technology, with departments should refer to. Departments should also refer to the NOVA reference model for more detailed collateral on the design of finance processes, finance data standards and performance indicators.

Robust, relevant data

Decisions about the management of public money must be made on the basis of robust and relevant information. This information must allow frontline organisations, departments and the Treasury to assess whether spending control totals will be met based on current plans and on actual spend to date. And it must allow risks to spending control to be identified and mitigated.

For the purposes of on-going spending control, all departments and devolved governments must monitor and share spending information with the Treasury on a monthly basis.

Departments and the Treasury must agree what information will be provided, focusing on the core information needed to manage the public finances. The exact requirements for each department will be agreed with the Treasury, but will, at a minimum, include accurate information on actual and planned spend. This should include robust forecasts of full year spend, and a breakdown of monthly spend, every month from the beginning of the financial year. Forecasts should be based on departments’ best information and an assessment of risks.

This is necessary to provide information to ministers about forecast levels of public spending, both to enable them to monitor the overall fiscal position but also to take spending decisions and to ensure expenditure is allocated in a way that provides value for money. Sound forecasts enable the government to ensure that departments are not overspending but also to identify in good time, and then reallocate, any underspends.

Departments and devolved governments should confirm the accuracy of their OSCAR data by reconciling it to internal management information. Good practice is to have OSCAR fully aligned at every level or to be able to explain any differences.

The Treasury will support departments and devolved governments by providing clear and comprehensive guidance on the classification of public spending data, and by providing a robust system (OSCAR) to collect, analyse and report this information.

Where the information currently provided is insufficient to monitor public spending effectively, the Treasury will agree with departments the steps needed to rectify this and how the department can be supported to achieve this. In addition to data on actual and planned spend, departments should provide detail on how SR plans will be implemented and achieved.

Where departments have a good track record of providing accurate and timely information, OSCAR data will already mirror internal management information, and flexibilities such as Budget Exchange will be fully available to these departments within the rules set out in this document.

For departments who produce or share less accurate or incomplete information, the Chief Secretary may take steps to minimise the risk to the public finances and to incentivise improvement. These may include restrictions of access to Budget Exchange and other budgetary flexibilities, lowered delegated authorities and mandating Departmental Unallocated Provision (DUP).

Consistent data

There must be consistent information about what the government is spending, both within and between organisations. Data should not be withheld. This ensures that decisions are taken on the basis of financial information that is as accurate and comparable as possible. Data supplied should be consistent with rules as set out in this document, and with definitions as stated in the Treasury Chart of Accounts.

Sharing of information must also be consistent. Departments should under no circumstances withhold basic data about public spending. The public has a right to know how its money is being spent. The Treasury is responsible for ensuring that spending is managed effectively, on behalf of citizens and Parliament. This fundamental role on behalf cannot be fulfilled without complete transparency about what is being spent.

Timely data

Without timely information, the government cannot take action to prevent plans going off track before it is too late.

A minimum of monthly data should be the presumption for spending departments and devolved governments, and it should usually be available no more than one month in arrears.

Evaluation plan

As part of monitoring spending, everyone involved in the implementation of a new policy or programme should understand what its success or failure would look like. This makes it necessary to reach agreement on appropriate metrics for evaluating impact at the start, which can only be measured accurately if implementation is designed to facilitate collection of that specific data.

Bids for new projects and programmes (and preferably legacy spend) should have robust evaluation plans included. Business case approval will not be secured without commitment to some measuring impact, an understanding of which is best gained through rigorous experimentation, for example a randomised control trial. Data collection and evaluation of this standard should be carried out throughout the policy’s life – which should in the first instance be a pilot, with continuation subject to meeting the agreed success level against the observed metric. Please refer to the Green Book for more detail on business cases and spending bids.

Box 2.A: Monitoring spending checklist

1) All departments and devolved governments must monitor and share spending information with the Treasury on a monthly basis. Departments and the Treasury must agree what information will be provided, focusing on the core information needed to manage the public finances. All organisations that are part of the public sector have the same duty to produce and share robust, timely financial information. The exact requirements for each department will be agreed with the Treasury, but will, at a minimum, include accurate information on actual and planned spend. Departments and devolved governments should confirm the accuracy of their OSCAR data by reconciling it to internal management information. Good practice will be to have OSCAR fully aligned at every level or to be able to explain any differences.

2) The Treasury will support departments and devolved governments by providing clear and comprehensive guidance on the classification of public spending data, and by providing a robust system (OSCAR) to collect, analyse and report this information.

3) Departments and devolved governments must provide robust forecasts of full year spend, and a breakdown of monthly spend, every month from the beginning of the financial year, which reconciles with their internal management information.

4) The data provided to the Treasury must be consistent with the data departments use for internal management purposes, so that decisions are taken on the same basis and there is an agreed position on what departments are spending. Departments and devolved governments should therefore confirm the accuracy of their OSCAR data each month by reconciling it to their internal management information.

5) Departmental Boards, supported by their Non-Executive Directors, are responsible for ensuring that the data provided to the Treasury is consistent with the information used internally.

6) A minimum of monthly data should be the presumption for spending departments and devolved governments, and it should usually be available no more than one month in arrears.

7) All new programme spend (and ideally legacy spend) must have an evaluation plan.

Managing spending

Good business planning is an essential part of managing spending. Each public sector organisation should plan to use the limited budget that it has to achieve good value for money and ensure that efficient and sustainable choices are made about how public funds are used. This means keeping an eye on the medium- and long-term picture, re-assessing risks and evaluating alternative ways of achieving policy objectives. Departments must follow the principles and methodology laid out in the Green Book when determining whether a prospective proposal would be value for money.

In order to manage spending, departments need to assess risks and change priorities effectively. Key to this is:

-

good risk management

-

a robust approach to contingency so that when risks do materialise, they can be managed within existing budgets

-

having the right skills and embedding spending control in the culture of public sector organisations

-

controlling spending throughout the year and

-

efficient cash management

Risk management

The Treasury has a range of risk management processes, based on its principle of devolving responsibility for managing spending as far as possible. In particular:

-

Treasury spending teams work closely with their respective departments to identify and monitor risks to delivering SR plans

-

those risks of the highest order, which would have a significant impact on the government’s overall fiscal position, are monitored by the Chief Secretary on a monthly basis, when the latest intelligence on likelihood and scale of risks, and departments’ plans to mitigate these are scrutinised

-

the Chief Secretary conducts a programme of bilaterals with the relevant departments on a regular basis, to discuss how these risks are being managed and

-

the Chief Secretary updates the Chancellor on a regular basis, ensuring oversight of the top-level risks

Complementing this process, departments are expected to have:

-

a rigorous approach to assessing risk, conducting an evidence-based assessment of the likelihood and scale of risks occurring, and sharing this with the Treasury. To support this, departments should regularly review their departmental financial risk management systems in discussion with the Treasury, agreeing priorities for improvement

-

a proactive and collaborative approach to risk management: Public sector organisations, departments and the Treasury should work together to mitigate risks before they hit the public finances, using early warning systems to intervene in a timely way. Departments should share their in-depth assessment of spending risks with the Treasury on a monthly basis, agreeing mitigating actions and monitoring systems as presented to departmental boards and

-

a process for continually monitoring AME, with an understanding of the volatility of the area of spending should be used to identify when spending is off track and where interventions should be made to bring costs back to planned levels so that forecasts are met

Please refer to the Orange Book for a more detailed description of risk management across government.

Approach to contingency

Apart from in a small number of exceptional cases, departments are expected to manage new pressures within their existing budgets. Departments are therefore expected to have a robust approach to contingency.

All departments must identify around 5 per cent of their allocated DEL that could be reprioritised to fund unforeseen pressures in their area of responsibility, and to share these plans with the Treasury. This amount can be made up either by having a list of contingency plans for how the department could reprioritise resources should this ever be necessary, or by a DUP, or a combination of the two.

While recognising the differences between DEL and AME, departments with particularly large non-pension AME spending should consider options for reprioritisation across Total Managed Expenditure.

Bilaterals with the Chief Secretary to the Treasury will provide the opportunity for departments to discuss contingency plans with the Treasury. The level of assurance required by the Treasury on this will depend on the Spending Team’s judgement of the level of risk presented to the Exchequer.

Departmental unallocated provision (DUP)

Departments are encouraged not to allocate their DELs fully against their programmes at the start of a financial year but to hold some provision back to deal with unforeseen pressures that emerge subsequently, including utilisation of provisions. This unallocated budget is referred to as the DUP.

DUP is reported in the Main Estimate as the difference between budgetary limits and the amounts allocated to specific functions; it is included within its own separate Estimate Line (within voted DEL) but cannot be spent by the department unless it is subsequently reallocated to appropriate functions in the Supplementary Estimate. Note that there is no such concept as negative DUP: this is a way of disguising over-programming and is forbidden.

The Reserve

Departments are expected to manage within their DEL budgets. If pressures arise in one part of a DEL, departments should respond by:

-

managing the pressures down

-

using their DUP

-

re-prioritising and making offsetting savings elsewhere in the budget

-

deferring spending elsewhere in the budget and

-

transferring provision from resource DEL to capital DEL (if the pressure is in capital DEL).

As part of the spending plans announced in SRs, the government allocates a Reserve for genuinely unforeseen contingencies that departments cannot absorb within their DELs. Separate Reserves are held for resource and capital DEL; both are small.

Exceptionally, a department may seek support from the Reserve. The Reserve can only be used for genuinely unforeseen, unaffordable and unavoidable pressures, or certain special cases of expenditure that would otherwise be difficult to manage, as agreed with the Chief Secretary.