2. Parents and carers Spotlight

Updated 18 November 2021

Applies to England

Introduction

This Spotlight is part of a series within the COVID-19: mental health and wellbeing surveillance report.

The series describes variation and inequality in the population. Spotlights have also been published for:

- age

- gender

- ethnicity

- experience of people with pre-existing mental health conditions

- employment and income

This spotlight is composed of 2 main categories of information:

-

weekly data drawn from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study up to week 8 of 2021 (22 February)

-

analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects made publicly available by week 7 of 2021 (15 February) or added by special request

The 2 categories of information have separate purposes.

Weekly data serves as an early warning system for potentially large changes and differences between groups. It should not be used to draw conclusions about smaller changes or differences between groups from week to week. This is because the data has not been analysed to control for any confounding factors or potential biases.

The analysis from academic research offers a good picture of change over time and differences between groups. Although less up to date, this intelligence is the basis for more nuanced interpretation and also feeds into the Important findings chapter.

The latest available version of the data presented in this spotlight can be found in the Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) tool.

Note:

Any deterioration of mental health captured in studies and weekly reporting should not be automatically interpreted as an increase in mental illness or need for mental health services. This is a difficult and stressful time for many, and some short-term increases in psychological distress and anxiety are to be expected.

Note:

To enable this Spotlight to be as up to date as possible, some pre-print (and therefore not yet peer reviewed) academic research is presented. Even with this approach there is still a time delay between data being gathered and findings reported.

Note:

The UCL COVID-19 Social Study focuses on the psychological and social experiences of adults living in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. This self-selected study sample is not representative of the UK population though was designed to have good stratification across a wide range of socio-demographic factors. Results were weighted to the national population. It is also important to note that some of the baseline levels for the UCL COVID-19 Social Study graphs use data from other countries and therefore may not be wholly representative of UK pre-COVID-19 levels.

Respondents to the COVID-19 Social Study weren’t specifically asked whether they were parents - they were asked if they live alone, with children, or with others. Adults who live with children can be considered to generally be their parents or carers, though there will be some exceptions to this. Where findings reported are drawn from this study, we use the term ‘adults who live with children’ rather than ‘parents’.

Main findings

During the COVID-19 pandemic:

-

on average, adults living with children reported a rise in symptoms of anxiety, psychological distress and stress in April 2020, which then subsided over the summer, but appears to have increased again over the winter and into 2021

-

there may have been an increase in the proportion of parents reporting depressive symptoms during the first national lockdown, but prevalence has remained lower than for adults living alone

-

adults living with children have been less likely to report feeling lonely, or increasing loneliness over time, than adults living alone

-

financial and food insecurity, loneliness and increased time spent on childcare and home schooling have been associated with worsening mental health and wellbeing among parents

-

both home and informal carers have been more likely to report higher and increasing levels of psychological distress, anxiety and depressive symptoms than non-carers throughout the pandemic, but were also more likely to report a greater sense of life being worthwhile than non-carers during the first national lockdown

Graphs tracking mental health and wellbeing in the population

Parents

Graphs tracking mental health and wellbeing of those living with children compared to those living with other adults (without children), or alone, during the pandemic.

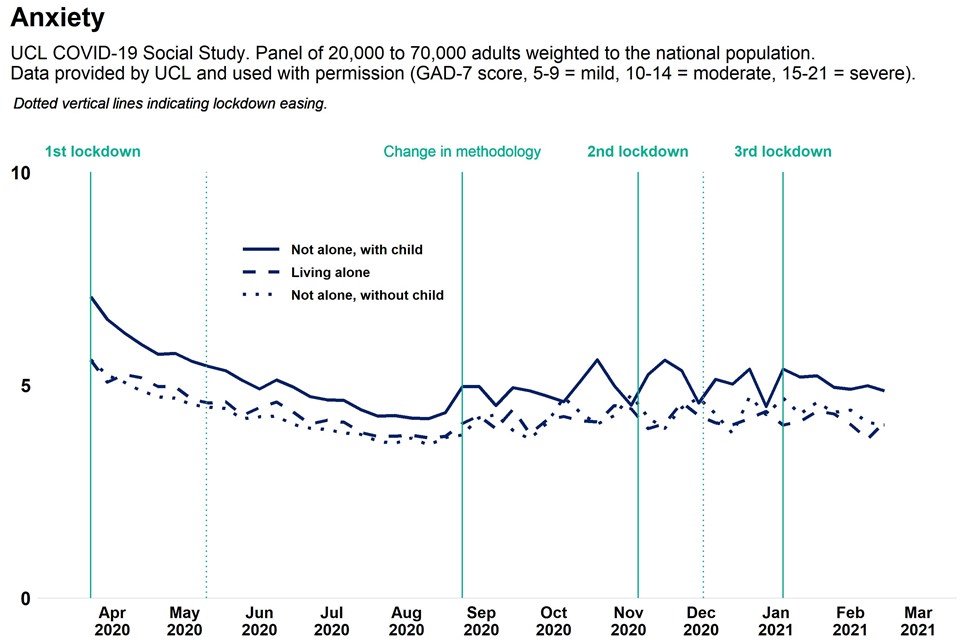

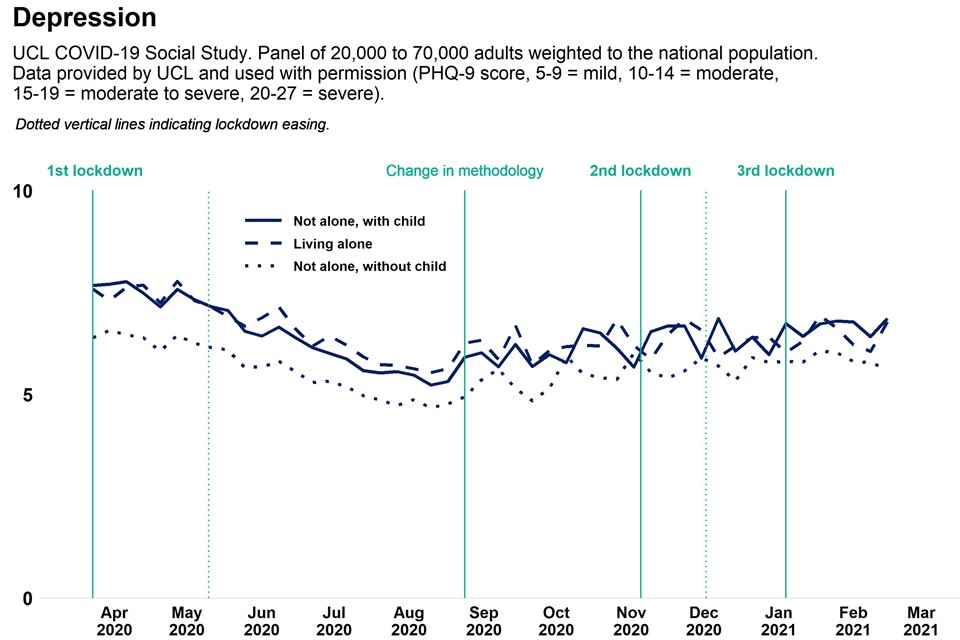

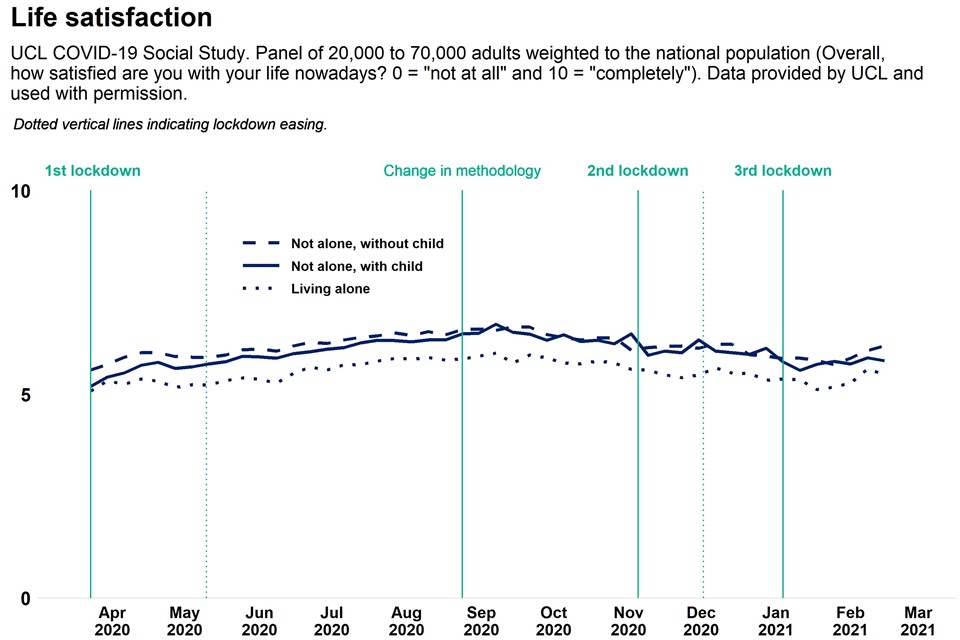

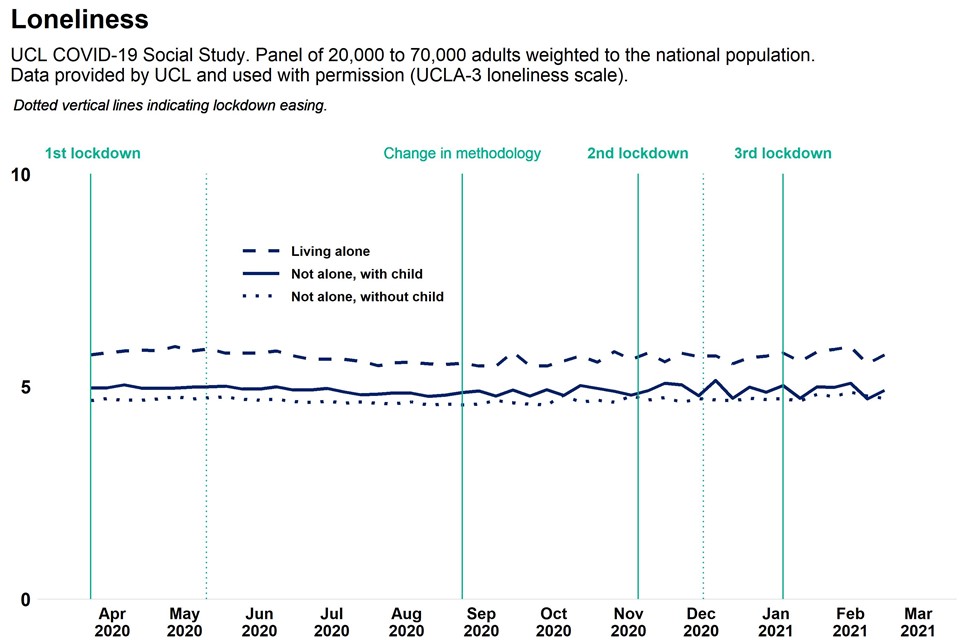

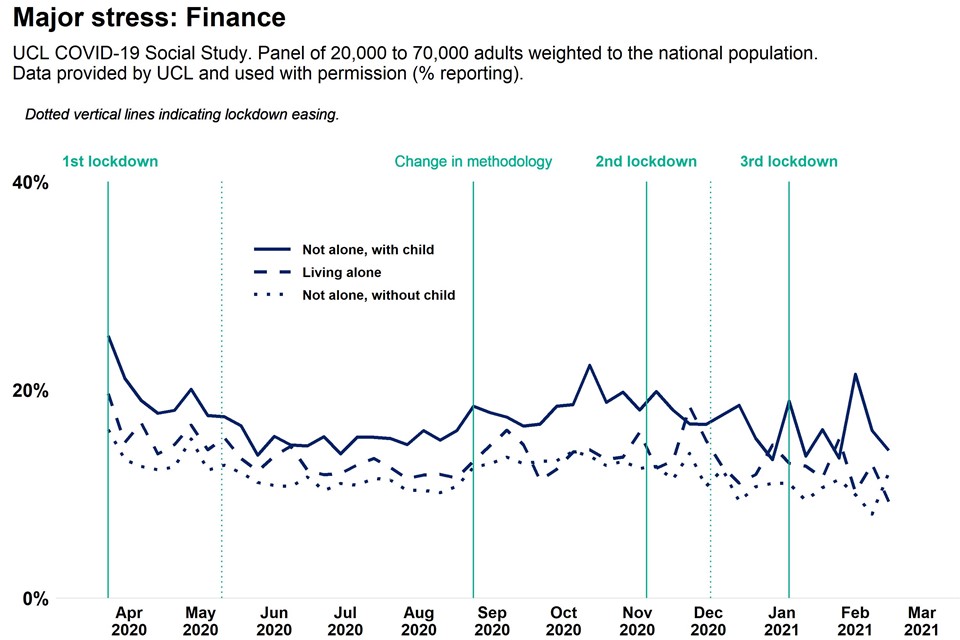

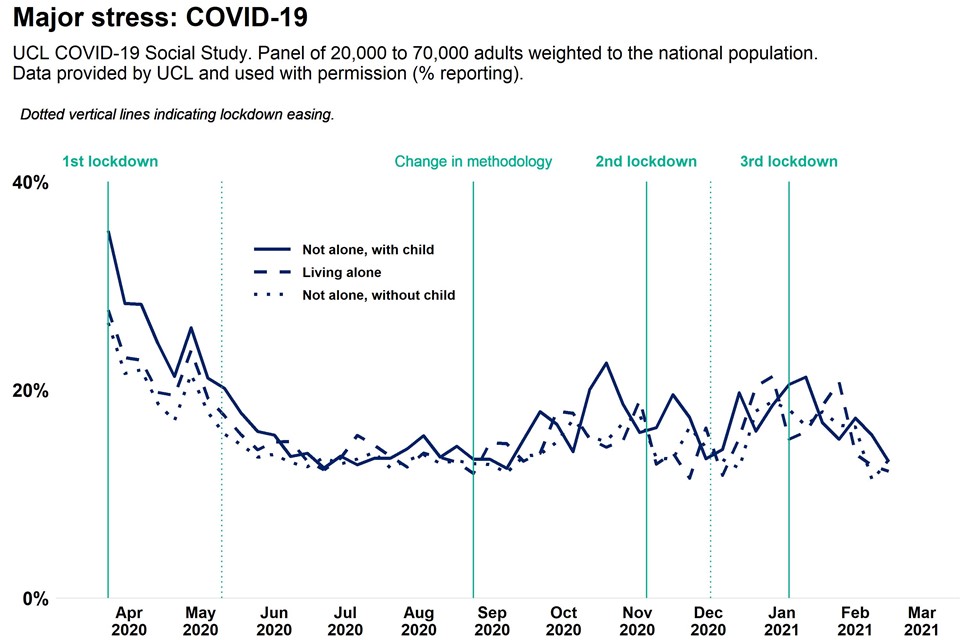

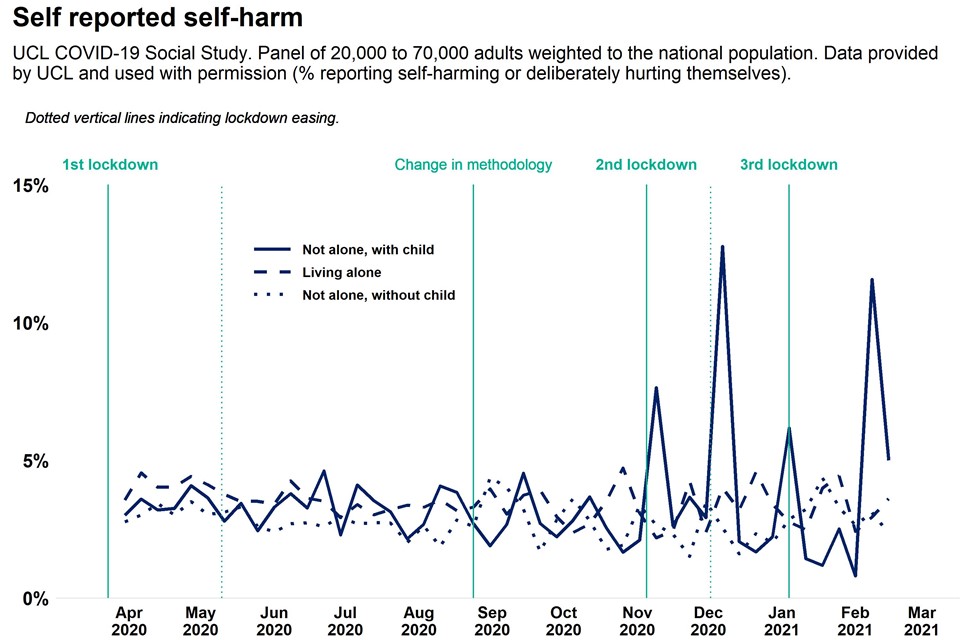

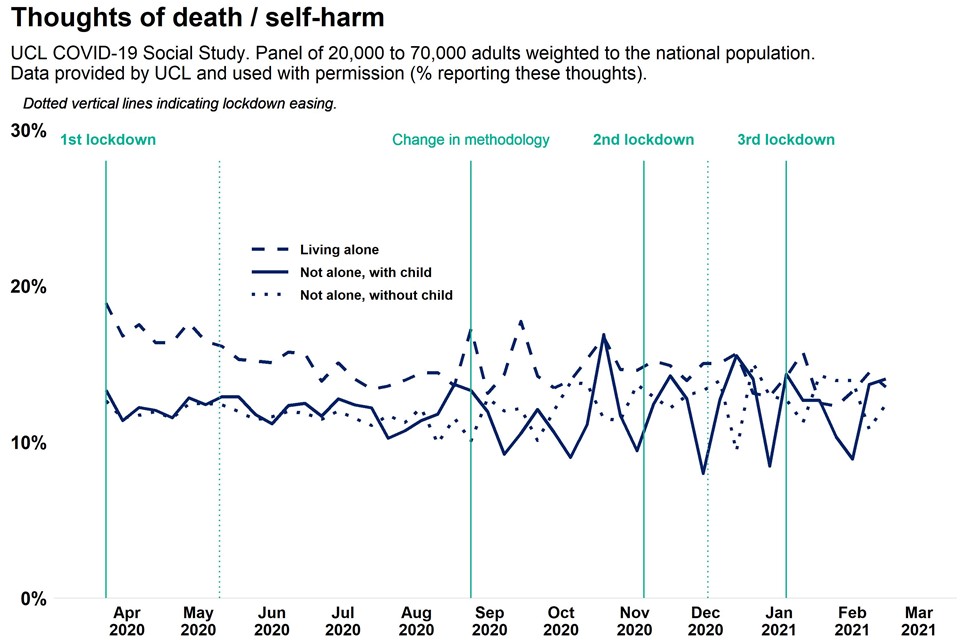

Based on observation of weekly trend data from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study:

-

average levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms in both parents and non-parents decreased between April and September 2020, but may have risen since

-

adults living with children have consistently reported higher levels of anxiety symptoms and finance related stress, but better life satisfaction than adults living alone

-

adults living with children have consistently reported either lower or similar levels of depression and loneliness compared to adults living alone

-

any association between self-reported self-harm, thoughts of death and self-harm, and living with children is unclear

Note:

The increase in volatility seen for some measures post September 2020 is likely to be due to a revision in methodology introduced at this time.

Each of these observations are based on unadjusted trendlines. This is to enable viewing of the most recent data available, but it may hide or exaggerate some patterns. Further analysis of the data (such as that presented in the academic projects section below) adjusts for relevant factors and gives a more accurate picture of mental health burden, changes over time and differences between groups. However, the analysis takes time, and so is not as up to date as the unadjusted trendlines.

Up-to-date data is available on the WICH tool.

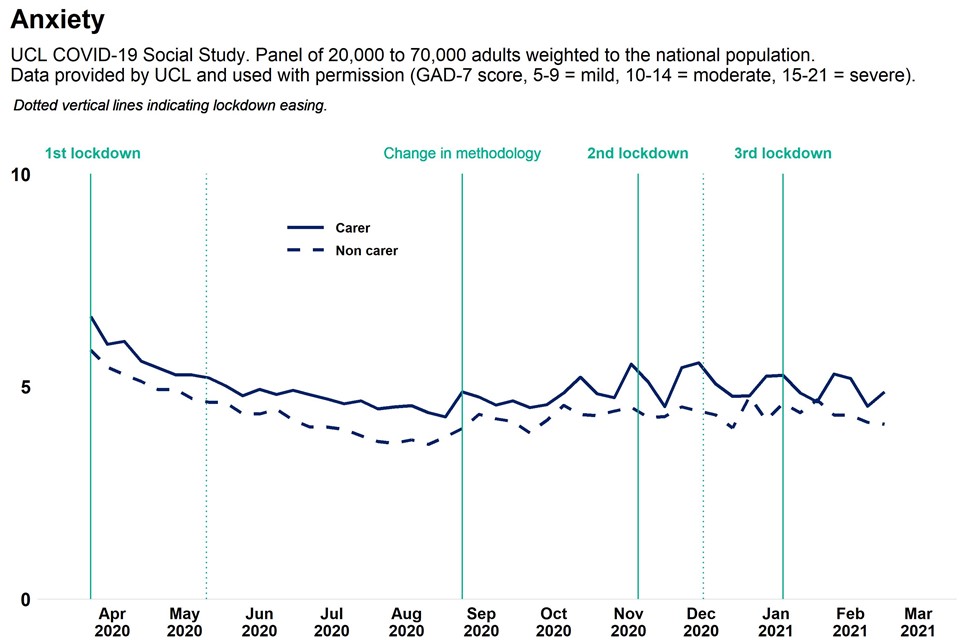

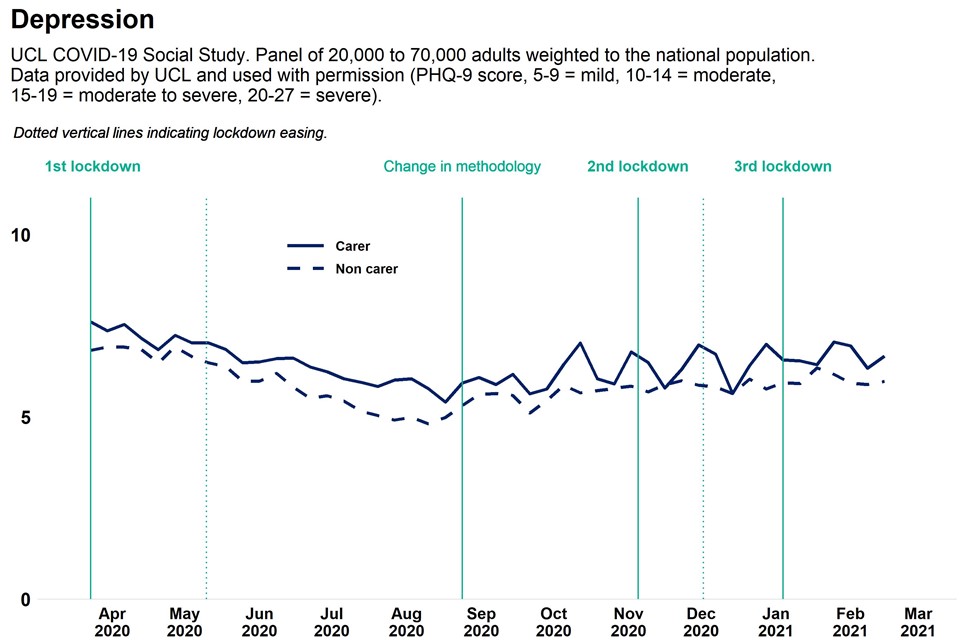

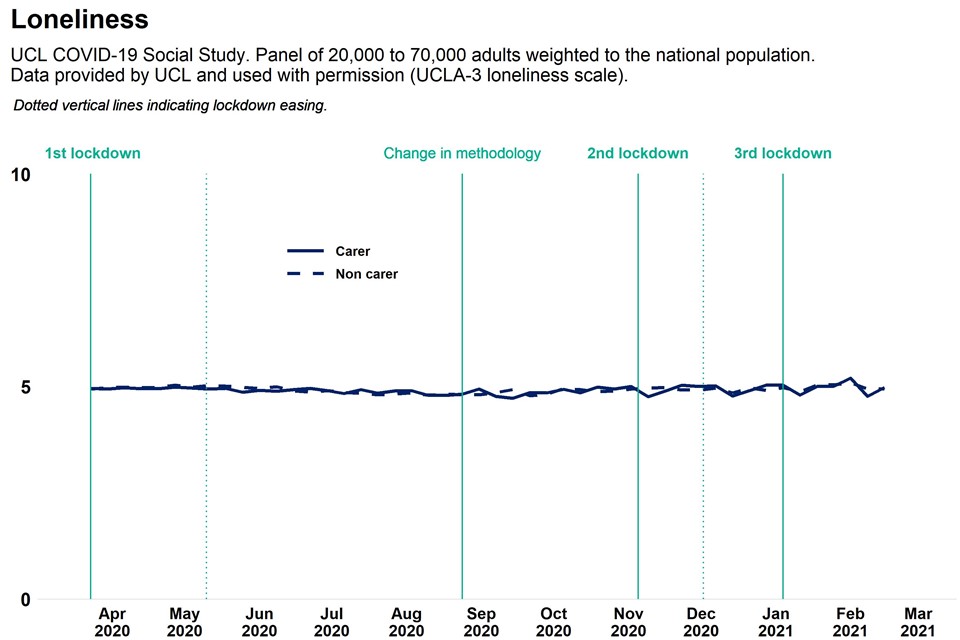

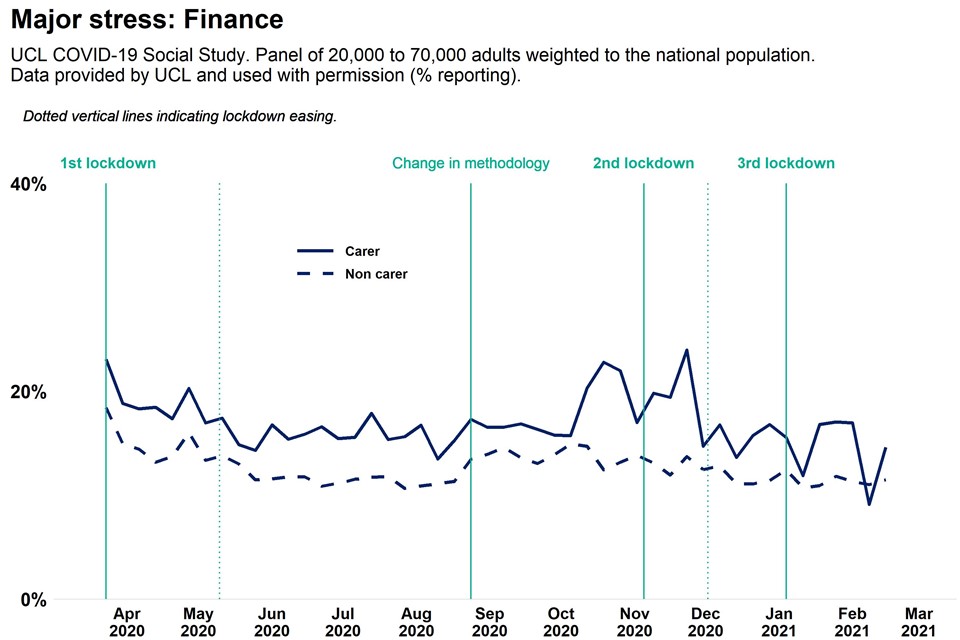

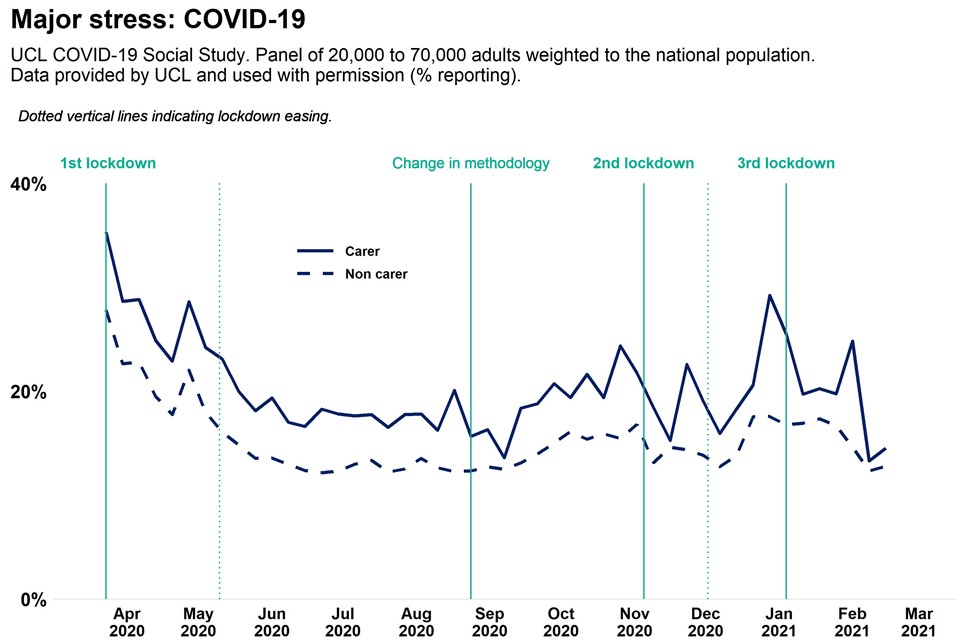

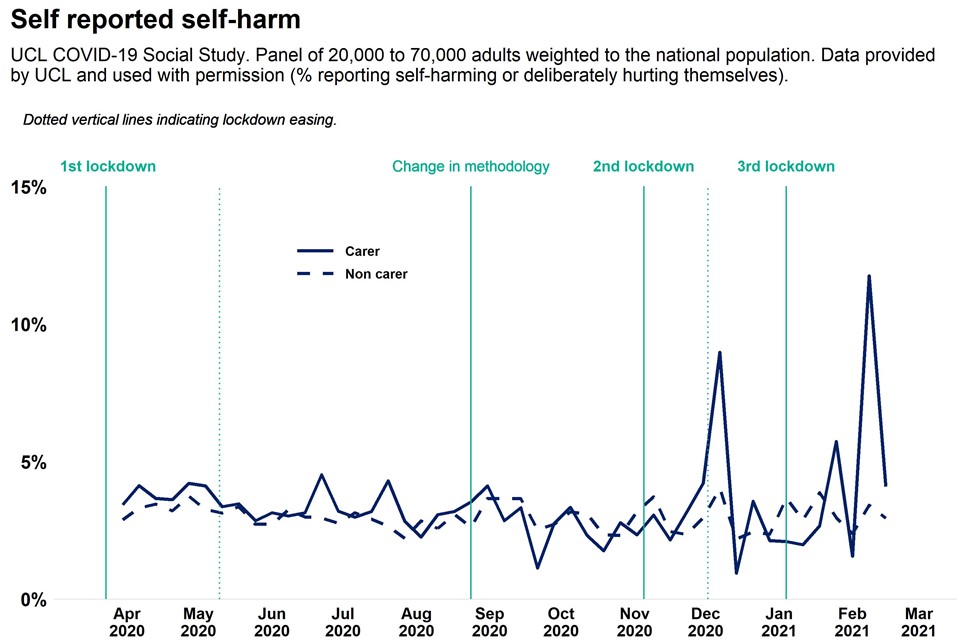

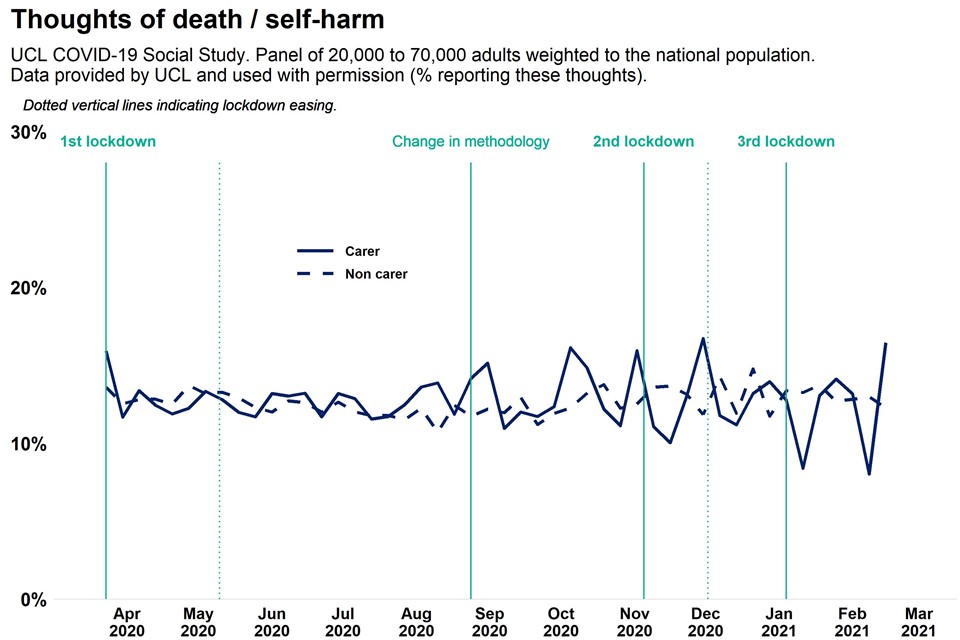

Carers

Graphs tracking mental health and wellbeing of adults with caring responsibilities (providing care for elderly relatives or friends, people with long-term conditions or disabilities, or grandchildren) compared to adults without caring responsibilities, during the pandemic.

Based on observation of weekly trend data from the UCL COVID-19 Social Study:

-

average levels of anxiety, depressive symptoms and stress among both carers and non-carers decreased between April and September 2020, but may have risen since

-

adults with caring responsibilities have consistently reported higher average levels of anxiety, depression and stress than adults without caring responsibilities

-

there is not a clear association between having caring responsibilities and self-reported loneliness, life satisfaction, self-harm or thoughts of death and self-harm

Note:

The increase in volatility seen for some measures post September 2020 is likely to be due to a revision in methodology introduced at that time.

Each of these observations are based on unadjusted trendlines. This is to enable viewing of the most recent data available, but it may hide or exaggerate some patterns. Further analysis of the data (such as that presented in the academic projects section below) adjusts for relevant factors and gives a more accurate picture of mental health burden, changes over time and differences between groups. However, the analysis takes time, and so is not as up to date as the unadjusted trendlines.

Up-to-date data is available on the WICH tool.

Parents - analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects

Was there an association between mental health and wellbeing and being a parent before the pandemic?

The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey, last conducted in 2014, found that common mental health disorders (CMDs) were most common among adults aged 16 to 59 who lived alone with no children. The prevalence of CMDs was lower among adults who lived with one other adult but no child, and adults who lived in a small family. Adult women who lived in large families or large adult households were more likely to report a CMD than those in smaller families or households.

Mental health and wellbeing of parents during the pandemic

Anxiety and depression

The evidence appears to be consistent for anxiety but mixed for depression.

One study found that adults living with children were more likely to report high levels of anxiety and depression in April 2020 than adults living without children. When specifically focusing on COVID-19 related anxiety, controlling for other factors such as age and gender increased the association between anxiety and living with children. However, when focusing on more general anxiety, controlling for these other factors decreased the association between anxiety and living with children. A second study found that the prevalence of depressive symptoms among parents of children aged under 16 increased from around 6% before the pandemic to 20% in June 2020. A third study, focusing on a sample of mothers in Bradford, found that clinical levels of depression and anxiety increased from 11% and 10% respectively before the pandemic to 19% and 16% between April and June 2020.

A study with more recent national data has supported these findings for anxiety, but is less consistent for depressive symptoms. It found that adults living with children reported higher levels of anxiety but lower levels of depressive symptoms than adults living alone. Adults living alone reported higher levels of depressive symptoms but comparable levels of anxiety to people living with other adults (but no children).

Between early April and late August 2020 people living with children reported faster improvements in symptoms of anxiety and depressive symptoms than adults living alone or with other adults (but no children).

A separate smaller study has reported (PDF, 2.1MB) that, while levels of stress and depressive symptoms had gone down over the summer and then back up towards Christmas, levels of anxiety had remained relatively constant among parents. After a period of stability, parental anxiety and depression started to rise again around November 2020, and in January and February 2021 both were higher than their previous peak in April 2020.

Psychological distress

Studies analysing psychological distress have found similar results to those measuring anxiety. Adults living with a partner reported lower levels of psychological distress in April 2020 than adults living alone. Adults living with children in the household (particularly children aged under 5) reported higher levels of psychological distress than adults living with no children.

After factors such as age, gender and household income were accounted for, living with children under 5 years was associated with a notably larger increase in psychological distress in April 2020 compared to before the pandemic.

A more recent study has found that the levels of psychological distress reported by adults living with or without a partner returned to the respective levels reported before the pandemic by September 2020. This particular paper does not comment on the experience of adults with young children.

Stress

Two small studies have reported on stress among parents. The first found a higher prevalence of traumatic stress in April 2020 among adults living with children than adults living without children. The second is more recent (PDF, 2.1MB) and has found that average levels of stress among a sample of parents decreased around July and August 2020, but then rose again towards the end of the year. Average levels of stress reported in January and February 2021 were higher than the previous peak in April 2020.

Sleep loss

Adults living with children in the house were more likely to report symptoms of sleep loss in April 2020 than adults living without children. This gap was larger where the children were younger and remained after other factors, such as age and gender of the adult were controlled for. The study does not comment on the change since before the pandemic among adults living with children.

Loneliness

While the overall proportion of adults reporting that they felt lonely was stable throughout the first national lockdown, there was variation between sub-groups. In April, adults living alone were more likely to report being lonely than adults not living alone (including adults living with children). Adults living alone were also more likely to report increasing, rather than decreasing, loneliness between the end of March and the beginning of May 2020 than adults not living alone (including adults living with children).

Possible causes of deterioration in the mental health and wellbeing of parents

Among the sample of mothers in Bradford, loneliness and financial insecurity were the factors that were most strongly associated with increases in depression and anxiety. Other factors that showed strong associations with anxiety and depression were food and housing insecurity, a lack of physical activity and poor partner relationships. Free text responses to the survey also highlighted anxiety about becoming ill or dying from COVID-19.

An earlier report from the same study highlighted that many of the families lived in poor quality (28%) or overcrowded (19%) housing, and that this was more common among the families of Pakistani heritage and other ethnicities than the White British families. Financial (37%), food (20%), employment (37%) and housing (10%) insecurities were common, particularly where the respondent had been furloughed, self-employed, not working or unemployed. When financial insecurity was taken into account, Pakistani heritage mothers were less likely than White British mothers to experience an increase in depression and anxiety.

An ongoing national survey of parents and their children (PDF, 2.9MB) has highlighted higher levels of stress, depression and anxiety among parents with children aged younger than 10, low incomes, children with special educational needs or neurodevelopmental differences (SEN/ND) and single parents. One caveat to the above summary is that reports of depressive symptoms among parents were more common once the child was older than 10. Early 2021 also saw a sharp increase in the number of parents or carers who reported that they could not meet the needs of both their child and their work. This was more common (PDF, 2.1MB) among parents or carers of young children, and parents or carers of children with SEN/ND.

Other studies with national samples have explored the relationship between increased childcare responsibilities and psychological distress.

One study has reported that adults who were spending 16 hours or more a week on childcare or home schooling were more likely to develop a clinical level of distress than those who had no children or did not spend any time on childcare. However, they also report that this gap may have decreased by June 2020.

An earlier analysis of data from the same project highlighted that working parents had reported a worse deterioration in psychological distress than adults not living with children – and that this was associated with increased financial insecurity and time spent on childcare or home schooling. Moreover, they report that these burdens have not been shared equally between men and women (with women taking on more childcare and home schooling), or between richer and poorer households (with poorer households experiencing more financial insecurity).

On average, women reported spending 5 more hours on housework and 10 more hours on childcare than men per week during the first national lockdown. This increased housework and childcare was associated with higher levels of psychological distress among women. Both men and women who had to adapt their work patterns because of childcare or home schooling reported worse levels of psychological distress than those who did not. This association was much stronger if one parent was the only member of the household who adapted their work patterns, or if that parent was a lone mother.

Another feature of parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic has been the return home of older children. Nearly a quarter (24%) of the Millennium Cohort Study, currently aged 19, reported a change in the people they were living with as a result of COVID-19. Often this was the respondent returning to live with their parents. These changes in living arrangements were associated with increased likelihood of stress and family conflict.

Carers – analysis from a range of ongoing academic research projects

At the start of 2020, around 9 million adults were unpaid carers (PDF, 126KB) of people with disabilities, long term health conditions or issues related to old age. About half of this group were caring for someone living in the same household (home carers).

Home carers (defined as people who look after or give special care to someone who is sick, disabled or elderly within their household) were already more likely to report worse levels of psychological distress than non-caregivers before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the increases in reported psychological distress between 2019 and April 2020 were larger among home carers than non-carers. This was followed by further increases in psychological distress (PDF, 126KB) for home carers compared to non-carers, between April and July 2020. These 2 studies did not report on the experience of people caring for someone outside of their household.

Those caring for a child under 18 or for someone with a learning disability reported (PDF, 126KB) larger increases in psychological distress between 2019 and April 2020 than home carers who were looking after a spouse/partner. Home carers of children under 18 then reported reducing distress between April and July 2020, while those caring for adult children (where the person being cared for is an adult, but also the carer’s child) saw a marked worsening of their mental health. In addition, the more time a home-carer needed to spend on care-related activities, the larger the increases in distress between 2019 and July 2020. Increases in psychological distress throughout the pandemic have also been greater for home carers who had formal help prior to lockdown but then lost it.

After adjustment for factors such as age, gender and income, caregivers were more likely to report depressive symptoms during the first national lockdown than non-caregivers. Caregivers who reported high levels of loneliness were almost 4 times as likely as those who did not report high levels of loneliness to also report depressive symptoms. Sixty per cent of caregivers with depressive symptoms reported not accessing any therapeutic support (for example online or face to face) during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is supported by a third study (using a different dataset), which has found that informal carers (defined as people who had caring responsibilities for elderly relatives or friends, people with long-term conditions or disabilities, or grandchildren, not necessarily living within the same household) experienced higher levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety (PDF, 836KB) than non-carers at 5 different time points in 2020. However, during the first national lockdown carers also experienced a higher sense of life being worthwhile. No association was found between informal caring responsibilities and levels of loneliness and life satisfaction.

References

- Shevlin M, McBride O, Murphy J, Miller JG, Hartman TK, Levita L, et al. STUDY: Anxiety, Depression, Traumatic Stress, and COVID-19 Related Anxiety in the UK General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2020 May 18

- ONS. Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain - Office for National Statistics

- Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19: longitudinal analyses of 36,520 adults in England. medRxiv. 2020 Nov 3

- Pearcey S, Creswell C. Report 09: Update on children’s & parents/carers’ mental health; Changes in parents/carers’ ability to balance childcare and work: March 2020 to February 2021 (PDF, 2.1MB)

- Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, Hatch S, Hotopf M, John A, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul

- Daly M, Robinson E. Longitudinal changes in psychological distress in the UK from 2019 to September 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a large nationally representative study. PsyArXiv; 2021 Jan

- Falkingham J, Evandrou M, Qin M, Vlachantoni A. Sleepless in Lockdown: unpacking differences in sleep loss during the coronavirus pandemic in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 Jul 21

- Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. 2020 Jul 16

- Bu F, Steptoe A, Fancourt D. Loneliness during lockdown: trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 35,712 adults in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 May 29

- Dickerson J, Kelly B, Lockyer B, Bridges S, Cartwright C, Willan K, et al. Experiences of lockdown during the Covid-19 pandemic: descriptive findings from a survey of families in the Born in Bradford study. Wellcome Open Res. 2020 Oct 2

- Pearcey S, Waite P, Creswell C. Report 07: Changes in parents’ mental health symptoms and stressors from April to December 2020. (PDF, 2.9MB)

- Chandola T, Kumari M, Booker CL, Benzeval MJ. The mental health impact of COVID-19 and pandemic related stressors among adults in the UK. medRxiv. 2020 Jul 7

- Tani M, Cheng Z, Mendolia S, Paloyo AR, Savage D. Working Parents, Financial Insecurity, and Child-Care: Mental Health in the Time of COVID-19. 2020

- Xue B, McMunn A. Gender differences in the impact of the Covid-19 lockdown on unpaid care work and psychological distress in the UK [Internet]. SocArXiv; 2020 Aug

- Evandrou M, Falkingham J, Qin M, Vlachantoni A. Changing living arrangements, family dynamics and stress during lockdown: evidence from four birth cohorts in the UK. SocArXiv; 2020 Sep

- Whitley E, Reeve K, Benzeval M. Tracking the mental health of home-carers during the first COVID-19 national lockdown: evidence from a nationally representative UK survey. medRxiv. 2021 Jan 25 (PDF, 126KB)

- Gallagher S, Wetherell MA. Risk of depression in family caregivers: unintended consequence of COVID-19. BJPsych open. 2020 Nov

- Mak HW, Bu F, Fancourt D. Mental health and wellbeing amongst people with informal caring responsibilities across different time points during the COVID-19 pandemic: A population-based propensity score matching analysis. medRxiv. 2021 Jan 25 (PDF, 836KB)