CVL research report for the Insolvency Service

Published 17 December 2024

Applies to England and Wales

Executive Summary

In April 2022, the Insolvency Service published its First Review on the operation of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (“the Rules”). These Rules came into effect in 2017 with the overall aim being to provide better outcomes from insolvency and increased returns to creditors. That report included a commitment to review the creditors’ voluntary liquidation (CVL) process, including but not limited to pre-appointment expenses.

This report will partially fulfil that commitment by reviewing the efficiency and effectiveness of the CVL process, and on pre-appointment expenses / fees in general.

Analysis has been performed in relation to a randomly sampled dataset of 2,717 completed CVLs which started in 2017.

Efficiency

Efficiency is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives with the minimum of resources, in particular time taken, costs of the process and recoveries for creditors. Literature[Annex A] has highlighted three key quantitative measures of efficiency: time, cost and recovery rate.

- 6% of cases sampled were still ongoing at the time of data collection.

- The median length of time it took to complete a CVL was 712 days.

- The median cost (fees as a percentage of the value of the estate) was 163%.

- The median recovery rate for all creditors was 0%.

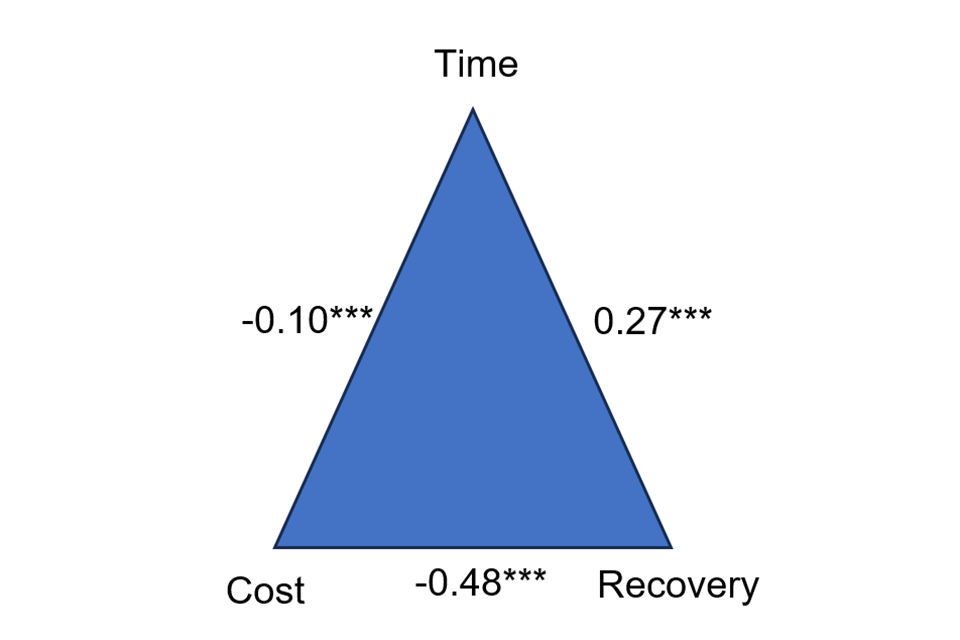

- Statistically significant relationships were found between time, cost and recovery rate. The largest of these was a negative association between cost and recovery rate.

Effectiveness

This is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives. The Insolvency Service identified three key processes within a CVL for this analysis: timely resolution, achieving the best outcome for creditors, and reporting directors’ conduct.

-

In 86% of cases no payments were made to creditors.

- The median amount paid to creditors as a percentage of assets realised was 0%.

- The median amount paid to IPs as a percentage of assets realised was 21%.

- 54% of cases were sifted in, which means they were identified by the Insolvency Service as in scope for investigation, of which 19% were then targeted for investigation. Of those targeted for investigation, the outcome led to a disqualification (DQ) in 49% cases. This corresponds to 5% of the total dataset resulting in a DQ.

- Across 1,618 cases where time charged was provided, the median investigation time (as a % of total hours) was 15%.

Pre-appointment fees

- 83% of cases included pre-appointment fees.

- The median of pre-appointment fees paid as a percentage of total fees paid was 51%.

- The median pre-appointment fee was c£4,000.

- The relationship between pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates was tested and was not statistically significant.

Introduction and background

Background

CVL is a UK company insolvency process in which companies that are unable to pay their debts are closed; the assets of the company are realised, and used to help repay debts to creditors (after the expenses of the process). This should enable an efficient exit from the market of non-performing corporate entities, with any business and assets recycled back into the economy by way of distributions, all overseen by a licensed insolvency practitioner (IP).

A CVL is initiated by the shareholders of an insolvent company via a company resolution (often assisted by the IP). The directors must then prepare a statement of affairs (showing the company’s assets and liabilities) to send to the creditors for consideration. An IP is appointed as liquidator with creditor approval and the directors must provide the liquidator with all relevant information and documentation, and otherwise co-operate with them, to ensure that the liquidator can perform their duties.

The liquidator will then wind up the company’s affairs. They do this this by realising all the company’s assets and distributing them to creditors and shareholders, after expenses of the liquidation have been paid. In addition to realising the company’s assets the liquidator(s) is/are responsible for regular reporting to creditors, reporting on the conduct of the directors in relation to the company to the Secretary of State for the Department of Business and Trade (in practice, to the Insolvency Service), and other statutory duties.

Distributions to creditors are made when the liquidator has sufficient funds in hand for that purpose, while retaining funds necessary for the expenses of the winding up. Distributions follow a priority (sometimes known as ‘the waterfall’) set out in law, which defines particular classes of creditors, for example ‘preferential creditors’, and their place in this priority.

When a company’s affairs are fully wound up, the liquidator must send a copy of the final account to Companies House. Three months after the final report has been filed, a liquidated company will be dissolved and will cease to exist.

CVLs are the most prevalent UK corporate insolvency process. In the last 10 years CVLs have averaged 74% of all UK corporate insolvencies, and 85% in the last three years (to Q4 2023). In the last 10 years there have been an average of 16,808 CVLs per annum and insolvency statistics released on 30th January 2024 show CVLs at their highest levels for some 20 years.[2]

Rationale for research

In April 2022, the Insolvency Service published its First Review[3] on the operation of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 (“the Rules”). These Rules came into effect in 2017 with the overall aim being to provide better outcomes from insolvency and increased returns to creditors. That report included a commitment to future work, including to “Review the creditors’ voluntary liquidations (CVL) process, including but not limited to use of statutory declarations; timing and content of the information provided to creditors; pre-appointment expenses.”

Pre-appointment expenses were identified by respondents to the First Review as an area of concern. Respondents suggested that the payment of pre-appointment expenses in a CVL should be allowed in the winding up on a similar basis to their treatment in an administration. In administration, there is a statutory process via which creditors approve expenses incurred pre-appointment with a view to achieving the objective of administration once that process commences. The review noted that the informal arrangements around pre-appointment fees are not fully transparent and subject to less control by creditors.

This report will partially fulfil the commitment made in the Rules review by collecting data on the efficiency and effectiveness of the CVL process, and on pre-appointment expenses / fees in general. Statutory declarations and the timing and content of information provided to creditors are outside the scope of this report.

Having an efficient out of court mechanism for the private sector to deal with smaller insolvent companies could be considered desirable, as it allows those in financial difficulty to obtain a resolution without government intervention. But concerns have been raised by stakeholders in key areas:

- In addition to the First Review, research[4] has highlighted the debate around IP remuneration and that this is not unique to the UK, but is an issue that has invited legislative and judicial intervention in several other jurisdictions. Whilst it has been suggested that cases where the liquidator appears to be the main beneficiary of the liquidation should be closely scrutinised, a careful balance needs to be struck as a certain level of IP remuneration may be needed to incentivise a good quality profession, which ultimately helps underpin confidence in the insolvency regime[5].

- Khan (2023)[6] suggested that there is a gap in empirical analysis around insolvency procedures: “Though empirical work in this area of law is growing there is still scope for further research”. A similar point is highlighted in research by Hardman and MacPherson (2023)[7]: “More generally, there is only a limited number of examples of empirical analysis of insolvency law in England and Wales and across the wider United Kingdom”. The lack of empirical data in insolvency regimes has been acknowledged by the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[8] who suggest that “there are virtually no assessments of insolvency systems based on empirical data. The assessments and design of insolvency regimes should be based on relevant statistics, thereby providing the infrastructure for sound policy decisions.”

- Concerns have also been raised around so-called ‘burial liquidations’. Whilst there is no legal definition of ‘burial’ or ‘buried liquidations’ it can be interpreted as relating to CVL cases where an IP seeks to wind up and dissolve a company without conducting adequate investigations into the conduct of directors and/or not pursuing all of a company’s potential assets. In the Second Reading debate of the Economic Crime and Corporate Transparency Bill in the House of Lords on 8th February 2023, The Lord Agnew of Oulton DL described these as “an unholy trinity of company director, local accountant and so-called ‘friendly’ insolvency practitioner quietly liquidate a company on a voluntary basis with no questions asked as to how the director might have ripped value out of the company for his own benefit prior to the liquidation”[9].

- Concerns have also been raised about the emergence of ‘CVL factories’. These relate to IPs or IP firms where CVLs are being advertised at a very low cost. Whilst efficiency is desirable there is a concern as to whether full duties can be carried out for such a cost.

Methodology

In 2021 the Insolvency Service drew a simple random sample[10] of 2,900 CVL cases for a commissioned data collection exercise (from a total population of 10,197 CVLs in England and Wales in 2017). At that time 2,071 of the 2,900 cases had been completed. The present research has opted to build upon that dataset. The basis for this is that, when collecting data on CVLs, there is a balance to be struck between finding cases that are not too old, but also have been completed[11]. Whilst older cases can be criticised for not reflecting the situation at present, recent samples may be biased by only including cases with a shorter time to completion. As the sample has been selected using a simple random approach, the findings of this research will be generalisable back to the target population, i.e., CVLs in England and Wales starting in 2017.

In all CVL processes the IP has a statutory duty to file key documents at Companies House, the content of which is subject to statute and best practice guidance. Key elements of this documentation (such as the total costs incurred) are not available until the liquidation is closed, hence the sample being limited to closed cases. Whilst the majority of information is similar, or the same for many of the data fields, aiding analysis, there are variations by IP or dependent on which firm they work for (see below for limitations).

Key documents

During the present research, key documents relied upon, and which for each CVL are filed at Companies House, consisted of:

- Liquidators’ appointment documentation;

- Company statement of affairs (as prepared by the directors);

- Liquidators’ final account; and

- Company statutory filed accounts.

Data collection

- Initial sample checking - 75 of the original data set of 2,071 cases were checked by senior staff for accuracy, even though they had already undergone quality assurance when previously collected. The sample checking consisted of comparing the information in the data set to the source documents at Companies House. The sample size represented 3.5% of the cases and was determined as sufficient due to low level of errors identified and resource constraints.

- Additional variables - the additional 829 previously incomplete cases were compared to filings at Companies House to determine the dissolution date.

- Manual input – many of the fields required manual input from the source documents on Companies House: a. the original analysis of 2,071 cases required manual input of the investigation time as this had not been part of the original data collection in 2021. b. The remaining cases that had since completed required manual input of all the required variables. The required variables are included in Annex A.

- Quality assurance - given the high degree of manual input required by junior members of staff, and the different quality of information supplied by the IPs, sample validation was required (a random sample of 85 of the now completed 646 cases were validated). The sample size reflected 10% of the cases. Due to low level of errors and resource constraints this was deemed sufficient.

Limitations

- Time (the duration of the liquidation) – the end date of the liquidation is by reference to the date a company was dissolved. However, the actual liquidation will have come to an end at least 3 months prior to this date when the liquidator issues their final report stating that the liquidation has come to an end. This will mean that, when performing calculations/analysis where time is included, it may be overstated. For example, the median length of time a case is open is 712 days (2.0 years), however, if 92 days (3 months) are deducted to reflect when the actual liquidation ended, then the median length of time a case is open is 620 days (1.7 years).

- Pre-appointment fees – details are not always provided in the documentation available in respect of the amounts paid. Where there is no amount in respect of pre-appointment fees, this may be because there was no fee paid as there were no funds available, or a pre-appointment fee was not charged. If the data field is blank or nil it is assumed that there was no pre-appointment fee paid. If a pre-appointment fee had been paid, it would be disclosed in either the receipts and payments account or included in the narrative of the liquidator’s report in accordance with legislation and best practice.

- Post-appointment costs a. Remuneration charged – details of the time costs spent by the IP and their staff in administering the cases are not always provided. This is either because: i. The post-appointment remuneration is not solely based on time costs, and so total time charged is not required to be disclosed; or b. Remuneration paid - where there is £0 in respect of post-appointment fees, this may be because: i. A fee resolution was not sought as there were no assets to realise; ii. There were no assets available to pay the agreed fee; or iii. A director or third party may have paid the agreed fee and so disclosure was not required.

- Assets realised – there are instances of a third party or a director paying part/all of the fees. This may be recorded by the IP as a ‘contribution to costs’ and recorded as an asset realisation. However, this does not necessarily provide an accurate reflection of the assets of the company that have been realised by the liquidator. The assets realised figures included within the data collected may include third party contributions to costs if this is how the IP has recorded them.

- Fees as % of asset realisations – for the reasons stated above in 3 and 4, this metric benefits from clarification. For example, the liquidator’s report could state that asset realisations were £1,000, total fees were £3,000 but the director(s) personally paid £2,000. The calculation of “fees as a % of realisations” in this instance would show as 300%, as the money to pay the fees comes from elsewhere to supplement the available company assets.

- Investigation time – this is not always available within the liquidators’ reports. If a liquidator’s post-appointment fees are not based wholly on a time cost basis, then there is no regulatory requirement to include a breakdown of all time costs incurred.

- Availability of information - there were some instances where the relevant pages within the documents were not included in the version filed at Companies House, or they were illegible, or the narrative did not support the figures in the receipts and payments account. Issues with consistencies in filings and collecting data from Companies House documents have been reported elsewhere.[12]

Uncertainty

Uncertainty exists whenever conducting research and producing statistics. Communicating uncertainty helps to promote public trust and mitigate against inappropriate conclusions being drawn.[13] One way for communicating uncertainty around a sample-based methodology is via the margin of error.[14] This provides an estimate for the precision of results. A smaller value indicates results are likely to be closer to the true value. The number of completed cases in the sample was 2,717. Based on a target population of just over 10,197, a maximum margin of error of less than 2 percentage points around results can be estimated using a confidence level of 95%.

Analysis

The analysis carried out in this report focuses on the 2,717 completed cases.

Approach to analysis

The analysis is set out in the following key sections.

- Efficiency – efficiency is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives with the minimum of resources. This section includes: a. Time – the number of days from the start to the end of the CVL process; b. Cost – the sum of pre-appointment and post-appointment fees charged as a percentage of the assets realised; and c. Recovery rate – the percentage of amount paid to creditors over amount owed to creditors. Also included is a breakdown of the recovery rate by type of creditor, as well as a recovery rate for IPs.

- Effectiveness – this is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives. The Insolvency Service identified three key processes within a CVL for this analysis: a. The World Bank principles[15] identify that an effective insolvency system should aim for timely resolution of insolvencies. This is the same measure of time as under Efficiency; b. The liquidator’s duty is to achieve the best possible outcome for all creditors; and c. The liquidator has an important role in identifying misconduct by the company’s directors prior to the insolvency. This analysis focuses on the level of “sifted in” cases, and those identified by the Insolvency Service as requiring further investigation, and where there were either transaction at an undervalue (TUV) or Preference claims.

- Pre-appointment fees – this section considers the prevalence and amounts of pre-appointment fees paid to the IP. It also investigates the relationship between pre-appointment fees and aspects of investigations.

The analysis uses median as a default for the average during this report. This is to recognise the IMF’s observation that, whilst mean values are often used when considering insolvency data, median values can often be a more suitable measure due to large differences between complex and small cases.[16] The mean is reported in Annex B to this report.

For the analysis, it is helpful to clarify certain terms used:

Cost: This is the sum of pre-appointment and post-appointment fees charged as a percentage of the assets realised.

Fees: This is the amount charged for the service provided. Fees only include charges to the IP or to a third party. It does not include liquidators’ disbursements that have to be incurred to ensure that the IP is complying with the relevant statutory and regulatory requirements, storage costs in relation to the company’s books and records, advertising the appointment in the Gazette, or the costs incurred in realising the assets.

Paid: This is the amount received for the service provided.

For the purposes of this report pre-appointment fees are the same as the amount paid pre-appointment.

Efficiency

This section considers efficiency in line with recommendations from the IMF.

The IMF has highlighted quantitative indicators that provide a basis for a general assessment of the efficiency of an insolvency system: time, cost and recovery rate.[17]

To analyse the efficiency of CVLs our analysis is based on:

Time: number of days the case is open, i.e. from start to end date

Cost: ((pre-appointment fees + post-appointment fees)/assets realised) x 100

Recovery: (amount paid to creditors / amount owed to creditors) x 100

Time

Of the CVLs within the sample (2,900), 6% (183) were still ongoing at the date of the analysis.

The analysis shows the length of time a CVL case is open from the start date, being the date that the liquidator is appointed, to the end date, being the date the company was dissolved.

Figure 1 CVL length in days

The median length of time it took to complete a CVL was 712 days (or just under 2 years). The minimum length of time was 122 days, and the maximum was 2,460 days.

Time is an important consideration that has been recognised in international best practice for an efficient insolvency regime. The World Bank principles for an effective insolvency regime include a key objective to ‘Provide for timely, efficient, and impartial resolution of insolvencies’.[18]

The median time of 712 days might be considered a lengthy period of time for a process designed to provide a ‘timely resolution’. This compares to an administration appointment where there is an initial period of 12 months, and to extend beyond that period requires approval of creditors, or potentially the court. However, there can be many reasons why a liquidation could last for this duration, e.g., lengthy asset investigations, sale of a property, settlement of a debt paid over a prolonged period, or legal proceedings. What is determined as ‘timely’ can be subjective and will be dependent upon the individual circumstances of each case.

Cost

Cost is defined as the amount paid pre-appointment plus the amount charged by the IP in post-appointment fees reported as a percentage of the value of the estate. The amount charged is usually the number of hours spent by the IP or their staff multiplied by the hourly charge out rate: it is not the amount the IP has been paid. The amount charged has been used to better reflect the economic cost, i.e., the full value of the resources used to provide the service.

Fees only include charges to the IP or to a third party (potentially an accountant for assistance with the statement of affairs). It does not include liquidators’ disbursements that have to be incurred to ensure that the IP is complying with the relevant statutory and regulatory requirements (for example ‘bonding’, (a mandatory form of insurance to cover any fraud or dishonesty by the IP acting as liquidator)), storage costs in relation to the company’s books and records, advertising the appointment in the Gazette (and potentially other newspapers), or the costs incurred in realising the assets (for example insurance, property/chattel agents and legal fees).

Figure 2: IP post-appointment fees

In 392 cases (14%) the post-appointment fees data was not available and so is not included in the above chart.

For the 2,325 cases where post-appointment fees data was available, 50% (1,162) of them had charged less than £10,000 with the median post-appointment fees being £10,004.

The basis for fixing the liquidator’s fees is set out in Rule 18.16 of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016 and guidance is provided for IPs in Statement of Insolvency Practice 9 (“SIP9”).[19]

This Rule states that the basis of fees must be fixed:

- as a percentage of the value of the assets which are realised, distributed or both, by the liquidator,

- by reference to the time properly given by the liquidator and their staff in attending to matters arising in the liquidation, or

- as a set amount (fixed fee).

Any combination of these bases may be used to fix the fees and different bases may be used for different things done by the liquidator. Where the fee is fixed as a percentage, different percentages may be used for different things done by the liquidator. Where remuneration is sought on more than one basis by the liquidator, it should be clearly stated to which part of the liquidator’s activities each basis relates. Per SIP 9 “payments to an office holder from an estate should be fair and reasonable reflections of the work necessarily and properly undertaken in an insolvency appointment”. Those responsible for approving payments from a liquidation to a liquidator should be provided with sufficient information to enable them to make an informed judgement about the reasonableness of the liquidator’s requests. Such information provided by the liquidator should be presented in a manner which is transparent, consistent throughout the life of the appointment and useful to creditors and other interested parties, whilst being proportionate to the circumstances of the appointment.

In a CVL it is the liquidation committee (if one has been formed) that determines the basis for fixing the liquidator’s fees. If a committee has not been formed, then the creditors will be asked to approve a resolution that specifies the basis of the liquidator’s fees. If the creditors do not pass the resolution, then the liquidator(s) will need to apply to court to confirm their fees.

The amount charged, i.e., time costs incurred by the IP, will not necessarily be disclosed in all circumstances:

Figure 3: Total fees (pre-appointment fees + post-appointment fees)

In 116 cases (4%) the total fees information was unavailable as there was no pre-appointment fee and post-appointment fee data was not available and so they are not included in the above chart.

Total fees were greater than £0 for 2,601 cases (96%). Total fees were greater than £0 and less than £10,000 for 980 cases (38%) and greater than £0 and less than £30,000 for 86% (2,226) of cases.

The median total fees figure for the 2,601 cases was £12,937.

Tables 1, 2 and 3 in Annex B provide additional details in respect of pre-appointment fees, post-appointment fees and total fees.

Figure 4: Assets realised

In respect of asset realisations in a liquidation, it is usually the case that the value realised is less than the value held in the balance sheet. This is often because the assets are sold as quickly as possible in order to minimise the fees involved in holding and selling them.

Tables 4 and 5 in Annex B provides details of the value of assets realised and cost.

Figure 5: Cost

There were 369 cases (14%) where there were no assets realised and an additional 40 cases with no total cost data.

There were 2,308 cases where there were asset realisations greater than £0 and total cost greater than £0. The median cost for those 2,308 cases was 163%.

With reference to the World Bank principles for an efficient insolvency process, a key objective is to maximise the value of a firm’s assets and recoveries by creditors. Furthermore, the IMF states that an efficient insolvency framework liquidates non-viable businesses and rehabilitates viable ones in a way that minimises costs and maximises value.[20] Although the value of asset realisations may have been maximised in these cases, the fees of the process are more than the assets realised in the majority of cases therefore the process is arguably not efficient.

Median total fees are £12,937 - if total fees are greater than the assets realised in the majority of cases then the value of assets realised must be lower than this amount. The median value of assets realised is £5,798.

In some cases where there are low asset realisations the IP must ensure third party costs are paid in priority to their own fees, which is potentially a reason for the relatively low level of IP fees paid. In insolvency processes there is a statutory order of priority of payments that are to be made from the assets realised; for CVLs these are set out in rule 6.42 of the Insolvency (England and Wales) Rules 2016.[21]

There are limited funds available to cover the costs of the liquidation in these cases, i.e., fees are limited to the net asset realisations, irrespective of how much time is spent working on the case.

Creditor recovery

Creditor recovery for this report is defined as amount paid to creditors as a percentage of amount owed to creditors with the amount being paid referred to as a ‘distribution’. For example, if a creditor was owed £100 and was paid 10 pence in the £, then they would receive a £10 distribution / 10% return.

As noted in the introduction there are different classes of creditors, paid in a statutory order of priority, and we have shown the distribution both by type of creditor and as a percentage of all creditors.

The types of creditors are:

- Fixed – those with a fixed charge over assets, typically a secured lender with a charge over property.

- Preferential – for this dataset, certain claims relating to employment, for example arrears of wages.

- Floating charge – those with a floating charge registered over moveable assets. Typically, this will relate to a bank or other type of lender to the company and the charge will be over moveable assets such as stock.

- Unsecured creditors[22] – all other creditors of the company, and usually consists of suppliers.

Creditor recovery by creditor class is based on those cases where there was that class of creditor.

Figure 6: Recovery – Fixed charge creditor

There were 250 cases (9%) in which there was a fixed charge creditor that had a debt outstanding at the date of appointment of a liquidator. In 59 of these cases (24%) there was a distribution and in the remaining 191 cases (76%) the fixed charge creditor did not receive anything. The median was 0% for all cases with a fixed charge creditor.

In cases where a distribution was made, the median was 100%.

Figure 7: Recovery – Preferential creditors

There were 905 cases (33%) where there was an amount owed to preferential creditors. In 197 cases (22%) there was a distribution and in 708 cases (78%) preferential creditors did not receive anything. The median was 0% for all cases with a preferential creditor.

In cases where a distribution was made, the median was 100%.

Figure 8: Recovery – Floating charge creditors

There were 250 (9%) cases in which there was a floating charge creditor that had a debt outstanding. In 49 cases (20%) there was a distribution and in 201 cases (80%) the creditor did not receive anything.

The median was 0% for all cases with a floating charge creditor.

In cases where a distribution was made, the median was 63%.

Figure 9: Recovery – Unsecured creditors

There were 2,697 cases (99%) in which there were unsecured creditors that were owed money. In 266 cases (10%) there was a distribution and in 2,299 cases (90%) the creditor did not receive anything.

The median was 0% for all cases with unsecured creditors.

In cases where a distribution was made, the median was 9%.

Across all creditors, irrespective of class, in the majority of cases (86%) the return is nil.

Khan (2023)[23] considered CVL cases initiated between December 2016 and December 2018 and so overlaps with the time period considered by the current research. A different approach was taken by Khan (2023), who considered returns to creditors where returns looking across all cases were considered, rather than our approach, which is to calculate a return per case. Khan’s research stated that unsecured creditors only received 1.48% in returns. Furthermore, in 94% of cases unsecured creditors received 0% of their debt. These findings are consistent with the current research, with 90% of cases unsecured creditors receiving 0% of their debt.

Table 6 in Annex B summarises the creditor recovery rates.

IP recovery rate

The Cost section above dealt with total fees that included post-appointment fees to a case and as stated, this is not necessarily the amount paid to the IP. Details of the amounts paid to the IP post-appointment are provided in table 7 in Annex B.

The IP recovery rate is post-appointment fees paid as a percentage of post-appointment fees.

Figure 10: IP recovery rate

In 392 cases (14%) the IP recovery rate (amount paid to IP post-appointment as a % of post-appointment fees) could not be calculated as there was no post-appointment fees data. This left a total of 2,325 cases with post-appointment fees, where the median recovery rate was 14%.

In 33% of cases (761) the IP had a recovery of nil, i.e., the IP received no payment against the post-appointment fees.

In 888 cases (38%) the IP recovered less than 50% of their post-appointment fees.

In 28 cases the IP had a recovery rate of more than 100%; this may be due to the IP being paid on a mixed fee basis (e.g., time costs and fixed fee) and the post-appointment fees data is in respect of the time costs element of their fee only.

Table 8 in Annex B provides additional detail in respect of IP recovery rates.

Associations between quantitative indicators of efficiency

A correlation is a method that can quantify the relationship between two variables, with the outcome represented in a score between -1 and +1. A negative relationship indicates that as one variable decreases the other increases, whilst a positive relationship means the two variables move in the same direction together. Whilst a correlation shows the relationship between two variables, it does not tell us if one variable caused the other.

When analysing correlations, it is useful to consider the p-values and the effect size. P-values are calculated assuming that there is no effect or difference between two variables (the null hypothesis)[24] and provides the probability of seeing an effect at least as large as the one we found in the sample. The p-value is then assessed against a significance level, which are commonly 0.05* , 0.01** or 0.001***. If the p-value is less than the significance level, we can reject the null hypothesis.

Whilst the p-value provides a measure of statistical significance, the effect size[25] provides information regarding the magnitude of the result. For a correlation, the correlation coefficient is called r, but its magnitude can be used as an effect size.

Analysis considered the relationship between time, cost and recovery, using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Spearman’s was used as it is more suitable when the relationship between two variables is not linear (which is the case in the data being used) and is less influenced from outliers (which is a common feature of the CVL dataset).

Figure 11: Correlations between quantitative indicators of efficiency

The effect size can be interpreted as follows[26]:

r = 0.00 < 0.10 - Negligible

r = 0.10 < 0.20 - Weak

r = 0.20 < 0.40 - Moderate

r = 0.40 < 0.60 - Relatively strong

r = 0.60 < 0.80 - Strong

r = 0.80 < 1.00 - Very strong

As can be seen in Figure 11:

- Cost and time have a weak negative association of r = -0.10, p <.001. A longer duration for a case is associated with lower cost, but this association is weak.

- Recovery and time have a moderate positive association of r = 0.27, p < .001. A longer duration for a case is moderately associated with higher returns to creditors.

- Recovery and cost have a relatively strong negative association of r = -0.48, p <.001. Higher costs are relatively strongly associated with lower returns to creditors.

Efficiency summary

Based on the time metric, the CVL process does not seem to be efficient, as the median length of time for a CVL to be concluded is 712 days (2 years). This compares to Australia where statistics show that those processes take between 5 months and 1 year.[27]

However, perceptions of what is, or is not, ‘timely’ are subjective - a CVL’s length will depend upon the specific facts of the case, for example, if the only asset to realise is a cash balance held in the company’s bank account, then this should not take a long time to realise. Conversely, if there is a case with a litigation claim that requires time to investigate, gather evidence, make the claim and go through the legal process, then this will take a far longer time to realise – both examples may be ‘timely’ on the facts of those cases.

The median cost per case was 163% indicating typical amount of assets in a company are lower than the typical resource required effectively to wind it up. This finding is consistent with Hardman and MacPherson (2023)[28] who, although focused on liquidations in Scotland, found that insolvency expenses can use up a large proportion of assets on a case, particularly for smaller companies. They suggest that insolvency expenses should be proportionate to the assets on a case and that a more streamlined process for smaller companies might be appropriate.

Regarding creditor recovery, the majority of all classes of creditor do not receive any recovery in relation to the amount they are owed.

Based on the above three measures of efficiency the CVL process is arguably not efficient. Although this is against a scenario where companies entering a CVL typically don’t have a high level of assets, with the median value of assets realised being £5,798.

However, this analysis has not looked at the timing of distributions to each class of creditor compared to the length of the process. The timings of distributions to different classes of creditor may also be affected by the statutory order of priority of payments, for example there may be sufficient assets realised after 6 months to make a distribution to preferential creditors but it takes a further 6 months to realise the remaining assets which would then enable a distribution to be made to the unsecured creditors.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives. The analysis focuses on the following three areas:

- Time: Liquidation is an insolvency proceeding by which a company’s activities are generally brought to a close. World Bank principles highlight that effective insolvency systems should aim for a timely resolution of insolvencies. As this is also a measure of efficiency, it is already covered in the ‘Efficiency’ section above.

- Outcome for stakeholders: The liquidator’s duty is to achieve the best possible outcome for the body of creditors as a whole and so the liquidator should act in the best interests of creditors to maximise their returns. The analysis considers a derived variable of amount paid to different stakeholders as a percentage of assets realised.

- Investigation: The liquidator also has an important role to play reporting on the conduct of the company’s directors prior to the insolvency and this analysis considers several metrics in relation to that. However, there are other aspects of misfeasance which will not be captured within this analysis.

Outcome for stakeholders

Analysis has been undertaken on the amount paid to different classes of creditor, as well as to IPs, as a percentage of assets realised.

Figure 12: Outcome – Fixed charge creditors

250 cases had a debt due to a fixed charge creditor and in 58 cases (23%) there was a payment made to them.[29]

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for all cases that have an amount outstanding to a fixed charge creditor is 0%.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for those cases where there was a distribution was 43%.

Figure 13: Outcome – preferential creditors

905 cases had a debt due to preferential creditors and in 197 cases (22%) there was a payment made to them.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for all cases that have an amount outstanding to preferential creditors is 0%.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for those cases where there was a distribution was 5%.

Figure 14: Outcome – Floating charge creditor

250 cases had a debt due to floating charge creditors and in 49 cases (20%) there was a payment made to them.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for all cases that have an amount outstanding to a floating charge creditor is 0%.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for those cases where there was a distribution was 21%.

Figure 15: Outcome – Unsecured creditors

2,697 cases had a debt due to unsecured creditors and in 266 cases (10%) there was a payment made to them.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for all cases that have an amount outstanding to unsecured creditors is 0%.

The median payment as a percentage of assets realised for those cases where there was a distribution was 33%.

Table 9 in Annex B includes additional detail in respect of outcomes for creditors.

Figure 16: Outcome – All creditors

In the majority of cases (86%) no class of creditor received a payment. The median amount paid to creditors (irrespective of class) as a % of assets was 0%.

Figure 17: Outcome – IPs post-appointment fees paid

2,348 cases had asset realisations greater than £0. In 675 of these cases (29%) the IP did not receive a payment post-appointment.

The median payment to IPs post-appointment as a percentage of assets realised is 21%.

Table 10 in Annex B includes additional detail in respect of the outcomes for IPs.

Investigation

If a company has entered into formal insolvency proceedings (which means administration, administrative receivership and CVL) in England, Wales and Scotland, the IP appointed has a legal duty to send a report to the Secretary of State for Business and Trade on the conduct of the directors. The Insolvency Service, acting for the Secretary of State, reviews the reports from the IP, along with any other information received. If the Insolvency Service decides there is sufficient reason to investigate, and that investigation is in the public interest, they may do so with a view to disqualification.

Figure 18: Investigation stages

Figure 18 and Table 11 in Annex B shows the number of cases that were “sifted in” and the outcomes of the further investigations. As noted in the glossary, a case that is “sifted in” has been selected from the submissions by the IP, following their investigations, to go forward for further review, investigation and potential action by the Insolvency Service.

This analysis also considered the proportion of cases with TUVs and/or preferences. These are claims brought by the IP under sections of the Insolvency Act against the directors of the liquidated company to realise monies for creditors. It should be caveated that: i) unsuccessful TUV or preference claims will not be recorded, although considerable time/cost may have been incurred pursuing such a claim; and ii) potentially other claims such as misfeasance will not be captured from the variable list.

1,468 cases (54%) were sifted in, which means they were identified by the Insolvency Service as in scope for investigation. 281 cases (10%) were then targeted for investigation.

Of those targeted for investigation, the outcome led to a disqualification (either via order or an undertaking) in 138 cases (5%).

One case/company can have multiple directors. So whilst the numbers above count the number of companies for which there has been a disqualification order/undertaking, it may be that multiple directors from the same company had a disqualification order/undertaking.

Only a very small number of cases had a recovery in respect of a TUV (1 or 0%) or preference (13 or 0%).

These low figures could be due to the high burden of proof to pursue such claims, or the costs of pursuing them being greater than any potential recovery (including legal costs). It may also be the case that IPs pursue recovery under a separate misfeasance claim and come to a commercial settlement with the directors to ensure costs (IP and legal) are kept to a minimum to ensure the maximum return to the creditors.

Any recovery under the above scenario would not necessarily be classified as a TUV or preference within the liquidator’s reporting.

Investigation time

The analysis also considered the amount of time an IP or their staff have spent reviewing and reporting on the conduct of the directors.

In respect of cases with no data, this will be due to the basis upon which the IP has fixed their fees. If the basis of fees is anything other than time costs, then a full SIP 9 time cost analysis (as is required when a time-cost fee resolution is passed) does not need to be provided. It does not mean that the IP has not undertaken their statutory duties in respect of investigations.

Figure 19: Investigation time

There were 1,618 cases where time charged was provided and the median investigation time (as a % of total hours) was 15%.

The median number of hours spent on investigations was 7 compared to the median number of total hours of 48 spent on the case.

Tables 12 and 13 in Annex B give further details of investigation time.

Effectiveness summary

In relation to outcomes for creditors, and the low amounts they receive as a percentage of assets, the current process may be viewed as ineffective. The median amount received by creditors as a percentage of assets is 0%, compared to a median of 21% in respect of IP payment post-appointment.

However, there are the costs of administering the process, in addition to the IP’s fees, which have to be paid in priority to creditors. In addition, there is a statutory priority for the payment of creditor classes, with unsecured creditors being last in the order of creditor payments.

In relation to investigations, and the results of those investigations, the cases identified as in scope for investigation are 54% (1,468), ultimately leading to disqualification (order or undertaking) in 138 cases which accounts for 5% of all completed cases. There is limited research into the level of disqualification or investigation which may prove to be a deterrent to poor director behaviour and as such it is difficult to conclude if this level is effective.

Pre-appointment fees

Pre-appointment fees are generally charged for: assisting the directors of the company with advice and guidance in the days/weeks prior to the liquidation; preparation of or assisting with the preparation of the statement of affairs; and preparing the other relevant documents required to put the company into liquidation.

It should be clarified that there is nothing inherently wrong with pre-appointment fees. If an insolvent company has no, or limited, assets the costs of the CVL process still need to be met (if no-one wishes to petition the court for its winding up), or else the insolvent company will continue to exist, possibly dormant, until it is dissolved. By charging a pre-appointment fee, the IP should then be able to carry out their legislative and regulatory duties. However, pre-appointment fees are an area of some concern to creditors as they have no control over them and often have limited visibility over what was paid, and by whom. A commitment was made in the First Review to gather additional information on this area.

Figure 20: IP fees

In 2,267 cases (83%) a pre-appointment fee was paid, with 780 then going on to have no post-appointment fees paid.

In 255 cases (9%) the IP did not have a fee paid.

Figure 21: Pre-appointment fees

The majority of cases (51%) had a pre-appointment fee of between £2,500 - £5,000. In 2,233 cases (82%) the IP received pre-appointment fees of greater than £0 and less than or equal to £10,000. The median level of pre-appointment fees is £4,000.

This analysis also considers if there is any relationship between pre-appointment fees, sift-in rates and investigation outcomes.

Analysis in respect of pre-appointment fees and investigations is undertaken to assess whether there is evidence of potential ‘burial liquidations’. A ‘burial liquidation’ can be interpreted as relating to CVL cases where an IP seeks to wind up and dissolve a company without carrying out adequate investigations into the conduct of directors and/or not pursuing all of a company’s potential assets. A relationship between pre-appointment fees and investigations may exist because the IP, theoretically, has some potential to manipulate the director conduct return or the amount of time they spend investigating a case.

The relationship between pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates has been tested using a point-biserial correlation. This is used in circumstances where there are two variables, which in this case are pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates, and one of the variables only has two possible values. In this case the sift-in rates variable only has two values: yes or no.[30]

In this scenario the null hypothesis is there is no effect or difference between pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates.

The point-biserial correlation for pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates is r = 0.024, p = 0.21 and therefore is a negligible positive relationship which is not statistically significant. Therefore, we fail to reject the null hypothesis.

The relationship between pre-appointment fees and investigation time has been tested using a Spearman’s correlation.

Pre-appointment fees and investigation time (as a % of total hours) have a weak negative association, although it is statistically significant, r = -0.10, p <.001. Higher pre-appointment fees are weakly associated with a lower investigation time (as % of total hours). Overall, this analysis does not indicate a widespread issue between pre-appointment fees and investigations.

Cases less than £10,000

Concerns have been raised in particular around ‘burial liquidations’ and the emergence of ’CVL factories’[31] and the possibility that IPs do not carry out adequate investigations to identify misconduct by directors because they are paid a low fee. There are CVLs being advertised at a very low cost. Whilst efficiency is desirable there is a concern as to whether full duties can be carried out for such a cost.

In the dataset analysed, cases with total fees paid of less than £10,000 account for 73% of cases (Table 2 below).

The analysis has analysed the relationship between:

- sift-in rates and cases with total fees (pre-appointment fee + post-appointment fee) of less than £10,000.

- sift-in rates and cases with total paid of less than £10,000.

To analyse the relationship between sift-in rates and cases with total costs and total fees paid of less than £10,000 a chi-square test of independence[32] was used. This test can determine whether there is a significant association between two categorical variables. In this case the following hypotheses were used:

0 - sift-in rates and fees (or costs) of less than £10,000 are independent

1 - sift-in rates and fees (or costs) of less than £10,000 are not independent

For the chi-squared test of independence the effect size phi (φ) is suitable where each variable has only two categories and can be used to help interpret the magnitude of effect[33]:

φ = 0.1 Small

φ = 0.2 Medium

φ = 0.5 Large

For total fees and sift-in rates the result is statistically significant and so we can reject the null hypothesis and find there is an association between sift-in rates and fees, X² = 18.07, p <.001, φ = 0.08. In this case there are fewer cases sifted in with fees less than £10,000 than would be expected if there was no association. Nevertheless, we must also recognise that the effect size of this association is small. There is also the possibility that this association might be impacted by other unobserved variables, for example lower fees might be reflective of smaller businesses with more straightforward affairs.

For total paid and sift-in rates the result is not statistically significant and so we fail to reject the null hypothesis and do not find evidence of an association, X² = 1.46, p = 0.10, φ = 0.02.

Table 1: Total fees and investigation outcomes

| Fee | Original dataset | % of total cases | Cases sifted in | Cases sifted in as % of cases in fee band |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | 116 | 4% | 65 | |

| £0 - £5,000 | 347 | 13% | 163 | |

| £5,001 - £10,000 | 633 | 23% | 310 | |

| < £10,000 | 1,096 | 40% | 538 | 49% |

| > £10,000 | 1,621 | 60% | 930 | 57% |

| Total | 2,717 | 1,468 |

1,096 cases (40%) had total fees of less than £10,000. Of these cases, 538 were sifted-in (49% of cases with total fees less than £10,000).

1,621 cases (60%) had total fees of more than £10,000, of which 930 were sifted-in (57% of cases with total fees more than £10,000).

Table 2 provides a summary of cases with total paid (pre-appointment fee + post-appointment fee paid) below £10,000 and the cases sifted in.

Table 2: Total fees paid and investigation outcomes

| Fee | Original dataset | % of total cases | Cases sifted in | Cases sifted in as % of cases in fee band |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nil | 255 | 9% | 142 | |

| £0 - £5,000 | 1,116 | 41% | 589 | |

| £5,001 - £10,000 | 602 | 22% | 321 | |

| < £10,000 | 1,973 | 73% | 1,052 | 53% |

| > £10,000 | 744 | 27% | 416 | 56% |

| Total | 2,717 | 1,468 |

In 1,973 cases (73%) the IP was paid less than £10,000 in total. Of these cases, 1,052 were sifted-in (53% of cases with total fees paid of less than £10,000).

In 744 cases (27%) the IP was paid more than £10,000 in total. Of these cases, 416 were sifted-in (56% of cases with total fees paid of more than £10,000).

Conclusions

The analysis of 2,717 concluded CVLs in England and Wales (a random sample from cases commenced in 2017) has sought to partially fulfil the commitment made in the First Review, with particular reference to efficiency, effectiveness and pre-appointment fees. Respondents to the First Review highlighted pre-appointment fees as an area of concern and both ‘burial liquidations’ and ‘CVL factories’ have also been raised as areas of concern which might be considered by part of this analysis.

In addition, this analysis seeks to reference and add to the relatively limited empirical research covering England and Wales insolvency processes whilst signposting areas that could be the subject of further analysis or research.

The key findings in each of the areas are set out below.

Efficiency

Efficiency is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives with the minimum of resources, in particular time taken, costs of the process and recovery for creditors.

- 6% of cases were still ongoing at the time of data collection.

- The median length of time it took to complete a CVL was 712 days.

- The median cost (fees as a percentage of the value of the estate) was 163%.

- The median recovery rate for all creditors was 0%.

There are no readily available statistics covering the length of all insolvency proceedings in England and Wales, but statistics in relation to Australian insolvency[34] stated that those processes take between 5 months and 1 year.

Khan (2023)[35] also concluded that the average return to unsecured creditors was 1.48%, and in 94% of cases unsecured creditors received 0%. This was also confirmed in the analysis of the additional dataset, where the median recovery to all creditors was 0%.

A process that takes an average of 2 years to complete and an average recovery of 0% to the majority of creditors is, arguably, not efficient by these measures.

Creditors of all categories may wait a considerable amount of time for any recovery, and it is difficult to conclude that CVLs provide a ‘timely resolution’ for creditors. We have not, however, looked at the timing of distributions to creditors compared to the length of the process.

Effectiveness

This is a measure of the extent to which the insolvency system achieves its intended objectives: timely resolution; achieving the best outcome for creditors; and reporting directors’ conduct.

- In 86% of cases no payments were made to creditors.

- The median amount paid to creditors as a percentage of assets realised was 0%.

- The median amount paid to IPs as a percentage of assets realised was 21%.

- 54% of cases were sifted in, which means they were identified by the Insolvency Service as in scope for investigation, of which 19% were targeted for investigation. Of those targeted for investigation, the outcome was a DQ in 49% cases. This corresponds to 5% of the total dataset resulting in a DQ.

- Across the 1,618 cases where time charged was provided, the median investigation time (as a percentage of total hours) was 15%.

The median level of cost (163% above) and the median amount paid to creditors as a percentage of assets realised (0%) could suggest that all of the asset realisations are paid to IPs. Hardman and MacPherson (2023)[36] found that in an average case (in Scotland) most money from assets will go to IPs to cover fees and expenses. However, the present research found the median amount paid to IPs as a percentage of assets realised was 21%. The key reason for this apparent discrepancy is the other costs/disbursements which the IP has to pay before they are paid, for example agents’ costs for selling assets, statutory advertising, insurance or legal fees. The present research therefore adds to the debate by highlighting that IPs themselves, through their fees, do not appear to take the majority of funds raised by assets.

Pre-appointment fees

- 83% of cases included pre-appointment fees.

- The median of pre-appointment fees paid as a percentage of total fees paid was 51%.

- The median pre-appointment fee was c£4,000.

- The relationship between pre-appointment fees and sift-in rates was tested and was not statistically significant.

Of the completed CVLs, 83% (2,267) have a pre-appointment fee that is not subject to any approval by the creditors of the company. Of those cases with a pre-appointment fee, 34% (780) do not have a post-appointment fee paid. In those circumstances, it may indicate that the fees were paid by a third party, or potentially paid upfront.

This research shows that pre-appointment fees are present in the majority of CVL cases, and so may legitimise concerns around their transparency, given their prevalence. However, no evidence of a systemic relationship between pre-appointment fees and either sift-in rates or investigation time has been found.

Additional dataset

The analysis also considered an additional dataset of 400 completed cases commencing in 2020 - 2021 to understand if there are any notable differences with the original earlier dataset. The additional dataset was not the focus of the analysis as there are far fewer completed cases available and therefore the data will be skewed to those cases that have completed quicker.

This is borne out by the observation that the only notable difference between the original dataset and the additional dataset is the median length of time the cases were open: 712 days for the original dataset compared to 436 days for the additional dataset.

All other key metrics in relation to efficiency and effectiveness were comparable. Annex C includes the detail of the key metrics for the original and additional dataset.

The additional dataset did not consider data in relation to sift-in or investigation outcomes.

Further potential research

- Whilst this research provides data around CVLs in 2017, we don’t know whether metrics around efficiency or effectiveness are changing over time. More regular monitoring of the key statistics in this analysis (for example annually) could address this gap so that trends can be identified and reviewed.

- There is limited research into the level of investigation or disqualification which might prove to be a deterrent to poor director behaviour, or by which such a process can be assessed as effective. A comparison of different international approaches may be required to understand the optimum level, or more research over time so that trends in the UK can be identified.

- Burial liquidations’ have been highlighted as a potential issue, whereby no action is taken against errant directors and if this was on a large scale there is potential for a wider impact on confidence in the UK economy. The scale of the potential issue is currently difficult to estimate or research. Where allegations of such burial liquidations are made, and such cases are able to be confirmed, it may be possible to identify key characteristics of such cases providing more information for further research.

Glossary of terms

| Term | Description |

|---|---|

| Insolvency Service | The Insolvency Service is an executive agency, sponsored by the Department for Business and Trade, that helps to deliver economic confidence by supporting those in financial distress, tackling financial wrongdoing and maximising returns to creditors |

| Companies House | Companies House incorporates and dissolves limited companies. It registers company information and makes it available to the public. Companies House is an executive agency, sponsored by the Department for Business and Trade |

| Creditor | A person or organisation that is owed money by a third party |

| CVL | Creditors’ Voluntary Liquidation, a formal insolvency procedure which involves the directors of an insolvent company voluntarily choosing to wind the company up |

| Dissolved | A company that has been struck off the Companies House register and is no longer a legal entity |

| Distribution/Dividend | Funds realised from the assets of a company and paid out to creditors |

| DQ | Disqualification order, pre-issue undertaking or post-issue undertaking which prevent a person subject to disqualification from acting in the promotion, formation of management of a limited company |

| HMRC | HM Revenue and Customs. |

| Investigation time | Work undertaken by an Insolvency Practitioner or their staff in relation to reporting on the conduct of the directors of an insolvent company |

| IP | Insolvency Practitioner, someone who is licensed and authorised to act in relation to formal insolvency procedures |

| Liquidator | An IP who is appointed during a CVL process to wind up the affairs of a company |

| Mean | The total of all the values, divided by the number of values (often referred to as the ‘average’) |

| Median | The value separating the higher half from the lower half of a data sample. For a data set, it may be thought of as “the middle” value |

| Misfeasance | A claim that can be brought against directors who do not fulfil their responsibilities of acting in the best interests of other parties, namely creditors. Under section 212 of the Insolvency Act 1986, an insolvency practitioner can bring a claim against a director of an insolvent company if it appears that the director has misapplied or retained, or become accountable for, any money or other property of the company, or been guilty of any misfeasance or breach of any fiduciary or other duty in relation to the company |

| Preference | An Insolvency Act claim that can be brought against directors who have done something (for example made a payment) which has the effect of putting one or more creditors into a better position than other creditors |

| Preferential creditor | A creditor of a company that has priority over other unsecured creditors, for example HMRC and employees |

| Secured creditor | A creditor of a company that holds security (mortgage/charge) over the assets of a company |

| SIP 9 | Statement of Insolvency Practice 9 sets out the requirements in relation to payments to IPs |

| Statement of Affairs or SOA | Statement Of Affairs is a document listing the assets and liabilities of a company |

| TUV | Transaction at an undervalue. An Insolvency Act claim that can be brought against directors which have undertaken a transaction at undervalue e.g., sold or transferred an asset outside the company for less than it is worth |

| Unsecured creditor | A creditor of a company that does not hold any security over the assets of a company and is not a preferential creditor. |

Annex A

List of variables in relation to the dataset

| Variable | Output | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CRN | Company Reference Number | The Company Reference Number is unique so can be used to identify companies on the Companies House register. |

| Company Name | Company name | Company name |

| Start Date | Date dd-mm-yyyy | Appointment of liquidator date |

| End date | Date dd-mm-yyyy | Final gazette |

| Number of Employees | Value | Number of employees as reported in the latest company accounts. |

| Audit Exemption | Yes/No | If no employee numbers are found, report whether the company is entitled to exemption from audit under section 477 of the Companies Act 2006 relating to small companies. |

| IP Firm | IP Firm name | The name of the IP firm dealing with the case |

| Pre-appointment costs or statement of affairs fee | Value | To capture any payments made prior to the liquidation starting, in “Liquidator’s final account’ |

| Fee estimate | Value | Initial fee estimate. Found in “Liquidator’s final account” |

| IP remuneration –amount charged | Value | Amount included as an Annex in “Liquidator’s final account” |

| IP remuneration – actual amount paid | Value | Final IP fee in “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Assets realised by IP | Value | Assets realised in “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Transactions at Under Value (TUV) income | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Preferences income | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Completion | Yes | Confirmation that the case is completed by checking filings to see if the liquidation is completed |

| Total owed to fixed charge holders | Value | Check “Statement of Affairs” and “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total owed to preferential creditors | Value | Check “Statement of Affairs” and “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total owed to floating charge holders | Value | Check “Statement of Affairs” and “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total owed to unsecured creditors | Value | Check “Statement of Affairs” and “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total owed to creditors | Value | The sum of amounts paid to fixed charge holders, preferential, floating charge holders and unsecured creditors. |

| Total owed to HMRC | Value | Check “Statement of Affairs” and “Liquidator’s final account”. This will be a subset of amount owed to unsecured creditors. |

| Total paid to fixed charge holders | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total paid to preferential creditors | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total paid to floating charge holders | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total paid to unsecured creditors | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total paid to all creditors | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

| Total amount paid out as the prescribed part | Value | Check “Liquidator’s final account” |

The Insolvency Service also provided two additional variables relating to investigations for all 2,900 cases. These are shown in the table below:

| Variable | Output | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sift in | 1/0 | |

| Where 1 is when a case has been sifted in | IPs are required to submit a director conduct return form to the Insolvency Service when completing a CVL.[1] This form then undergoes initial review to determine if the case is in scope for investigation. | |

| Investigation outcome | Disqualification order, pre-issue undertaking, post-issue undertaking, not proceeded with. | This describes the outcome of a case. |

Annex B

Additional tables

When there are bandings of a value in a table, ‘>’ means that the cases in that band will be greater than the lowest number. For example in the banding >£0 - £2,500 the lowest value included would be £0.01 and the highest value would be £2,500.00.

Table 1: Pre appointment fees

| Original dataset | ||

| Blank/Nil | 450 | |

| >£0 - £2,500 | 380 | |

| >£2,500 - £5,000 | 1,397 | |

| >£5,000 - £10,000 | 456 | |

| >£10,000 - £15,000 | 24 | |

| >£15,000 - £20,000 | 2 | |

| >£20,000 | 8 | |

| Total | 2,717 | |

| Mean | £3,775 | |

| Median | £4,000 |

Table 2: Post-appointment fees

| Original dataset | ||

| No data | 392 | |

| >£0 - £5,000 | 482 | |

| >£5,000 - £10,000 | 680 | |

| >£10,000 - £15,000 | 427 | |

| >£15,000 - £20,000 | 228 | |

| >£20,000 - £25,000 | 133 | |

| >£25,000 - £30,000 | 88 | |

| >£30,000 - £35,000 | 79 | |

| >£35,000 - £40,000 | 59 | |

| >£40,000 - £45,000 | 30 | |

| >£45,000 - £50,000 | 24 | |

| >£50,000 - £100,000 | 77 | |

| >£100,000 - £150,000 | 9 | |

| >£150,000 | 9 | |

| 2,717 | ||

| Median | £10,004 | |

| Mean | £16,029 |

Table 3: Total fees (pre-appointment fee + post-appointment fees)

| Original dataset | |||

| No data | 116 | ||

| >£0 - £5,000 | 347 | ||

| >£5,000 - £10,000 | 633 | ||

| >£10,000 - £15,000 | 556 | ||

| >£15,000 - £20,000 | 355 | ||

| >£20,000 - £25,000 | 213 | ||

| >£25,000 - £30,000 | 122 | ||

| >£30,000 - £35,000 | 94 | ||

| >£35,000 - £40,000 | 79 | ||

| >£40,000 - £45,000 | 42 | ||

| >£45,000 - £50,000 | 37 | ||

| >£50,000 - £100,000 | 101 | ||

| >£100,000 - £150,000 | 13 | ||

| >£150,000 | 9 | ||

| 2,717 | |||

| Median | £12,937 | ||

| Mean | £18,271 |

Table 4: Assets realised

| Original dataset | |

| £Nil | 369 |

| >£0 - £10,000 | 1,463 |

| >£10,000 - £25,000 | 460 |

| >£25,000 - £50,000 | 214 |

| >£50,000 - £100,000 | 111 |

| >£100,000 - £200,000 | 54 |

| >£200,000 - £500,000 | 33 |

| >£500,000 - £750,000 | 4 |

| >£750,000 - £1,000,000 | 2 |

| >£1,000,000 | 7 |

| 2,717 | |

| Median | £5,798 |

| Mean | £36,618 |

Table 5: Total cost

| Original dataset | % of total original cases | |||

| No assets realised | 369 | 16% | ||

| No total cost data | 40 | 2% | ||

| No data | 409 | 18% | ||

| >0% - 10% | 28 | 1% | ||

| >10% - 20% | 32 | 1% | ||

| >20% - 30% | 50 | 2% | ||

| >30% - 40% | 52 | 2% | ||

| >40% - 50% | 55 | 2% | ||

| >50% - 60% | 60 | 3% | ||

| >60% - 70% | 69 | 3% | ||

| >70% - 80% | 89 | 4% | ||

| >80% - 90% | 127 | 6% | ||

| >90% - 100% | 141 | 6% | ||

| >100% - 110% | 86 | 4% | ||

| >110% - 120% | 86 | 4% | ||

| >120% - 130% | 71 | 3% | ||

| >130% - 140% | 70 | 3% | ||

| >140% - 150% | 58 | 3% | ||

| >150% - 160% | 57 | 2% | ||

| >160% - 170% | 93 | 4% | ||

| >170% - 180% | 61 | 3% | ||

| >180% - 190% | 61 | 3% | ||

| >190% - 200% | 57 | 2% | ||

| >200% - 210% | 44 | 2% | ||

| >210% - 220% | 32 | 1% | ||

| >220% - 230% | 52 | 2% | ||

| >230% - 240% | 42 | 2% | ||

| >240% - 250% | 46 | 2% | ||

| >250% - 260% | 46 | 2% | ||

| >260% - 270% | 39 | 2% | ||

| >270% - 280% | 27 | 1% | ||

| >280% - 290% | 27 | 1% | ||

| >290% - 300% | 28 | 1% | ||

| >300% - 400% | 167 | 7% | ||

| >400% - 500% | 83 | 4% | ||

| >500% | 272 | 12% | ||

| Total cases with data | 2,308 | |||

| Median | 163% |

The mean has not been reported as it is distorted by a number of cases with very low asset realised values compared to the total costs.

Table 6: Creditor recovery - Original dataset

| Fixed | Preferential | Floating charge | Unsecured | All creditors | ||||

| 0% | 191 | 708 | 201 | 2,431 | 2,338 | |||

| >0% - 10% | 8 | 6 | 10 | 145 | 214 | |||

| >10% - 20% | 4 | 5 | 7 | 46 | 60 | |||

| >20% - 30% | 3 | 5 | 1 | 30 | 38 | |||

| >30% - 40% | 1 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 13 | |||

| >40% - 50% | 3 | 8 | 1 | 13 | 22 | |||

| >50% - 60% | 1 | 9 | - | 7 | 7 | |||

| >60% - 70% | 1 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 11 | |||

| >70% - 80% | 1 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| >80% - 90% | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||

| >90% - 100% | 33 | 146 | 15 | 5 | 6 | |||

| >100% | 1 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Cases with a distribution | 59 | 197 | 49 | 266 | 374 | |||

| Cases with that class of creditor | 250 | 905 | 250 | 2,697 | 2,712 | |||

| Median - cases with creditor | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |||

| Median - cases with a distribution | 100% | 100% | 63% | 9% | 9% | |||

| Mean - cases with a creditor | 17% | 18% | 10% | 2% | 2% | |||

| Mean - cases with a distribution | 71% | 85% | 53% | 17% | 16% |

Table 7: Post appointment fees paid

| Original dataset | |||

| Nil | 1,034 | ||

| >£0 - £1,000 | 394 | ||

| >£1,000 - £2,500 | 268 | ||

| >£2,500 - £5,000 | 261 | ||

| >£5,000 - £10,000 | 265 | ||

| >£10,000 - £20,000 | 263 | ||

| >£20,000 + | 232 | ||

| Total | 2,717 | ||

| Median | £810 | ||

| Mean | £6,145 |

Table 8: IP post-appointment fee paid as % of post-appointment fee

| Original dataset | ||

| No data | 392 | |

| Nil | 761 | |

| >0% - 10% | 312 | |

| >10% - 20% | 210 | |

| >20% - 30% | 132 | |

| >30% - 40% | 119 | |

| >40% - 50% | 115 | |

| >50% - 60% | 87 | |

| >60% - 70% | 96 | |

| >70% - 80% | 76 | |

| >80% - 90% | 109 | |

| >90% - 100% | 280 | |

| > 100% | 28 | |

| 2,717 | ||

| Median | 14% | |

| Mean | 32% |

Table 9: Total paid to creditors as percentage of assets realised

| Fixed | Floating | Preferential | Unsecured | All creditors | |

| 0% | 191 | 201 | 708 | 2,431 | 2,338 |

| >0% - 10% | 9 | 9 | 136 | 36 | 55 |

| >10% - 20% | 6 | 15 | 44 | 55 | 58 |

| >20% - 30% | 6 | 9 | 11 | 31 | 36 |

| >30% - 40% | 6 | 3 | 3 | 40 | 43 |

| >40% - 50% | 5 | 4 | 2 | 31 | 47 |

| >50% - 60% | 6 | 5 | - | 31 | 45 |

| >60% - 70% | 7 | 4 | 1 | 20 | 35 |

| >70% - 80% | 3 | - | - | 9 | 18 |

| >80% - 90% | 2 | - | - | 7 | 16 |

| >90% - 100% | 6 | - | - | 5 | 16 |

| > 100% | 2 | - | - | 1 | 4 |

| Total receiving a distribution | 58 | 49 | 197 | 266 | 373 |

| Total with debt to that class of creditor | 250 | 250 | 905 | 2,697 | 2,712 |

| Total with debt to that class of creditor and assets realised > £0 | 226 | 227 | 851 | 2,333 | 2,343 |

| Median - cases with that creditor class | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Median - creditors receiving a payment | 43% | 21% | 5% | 33% | 38% |

| Median - creditor class and assets > £0 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Mean - all cases with that creditor class | 19% | 6% | 2% | 4% | 7% |

| Mean - creditors receiving a payment | 72% | 27% | 8% | 36% | 44% |

| Mean - creditor and assets > £0 | 19% | 6% | 2% | 4% | 7% |

Table 10: Post-appointment fee paid as % of assets realised

| Original dataset | ||||

| No assets realised | 369 | |||

| 0% | 675 | |||

| >0% - 10% | 201 | |||

| >10% - 20% | 286 | |||

| >20% - 30% | 204 | |||

| >30% - 40% | 200 | |||

| >40% - 50% | 211 | |||

| >50% - 60% | 192 | |||

| >60% - 70% | 134 | |||

| >70% - 80% | 102 | |||

| >80% - 90% | 69 | |||

| >90% - 100% | 62 | |||

| > 100% | 12 | |||

| Total cases with assets realised > £0 | 2,348 | |||

| Median | 21% | |||

| Mean | 368% |

Table 11: Investigation outcomes

| Number of cases | % of total completed cases | % of sifted in | % of targeted for investigation | |

| Total dataset | 2,900 | |||

| Completed cases | 2,717 | |||

| Sifted in | 1,468 | 54% | ||

| Targeted for investigation | 281 | 10% | 19% | |

| DQ/undertaking | 138 | 5% | 9% | 49% |

| TUV recovery | 1 | 0% | ||

| Preference recovery | 13 | 0% |

Table 12: Investigation time in hours

| Original dataset | |

| No data | 1,099 |

| Nil | 50 |

| >0 - 5 | 557 |

| >5 - 10 | 443 |

| >10 - 15 | 225 |

| >15 - 20 | 95 |

| >20 - 25 | 56 |

| >25 - 30 | 46 |

| >30 - 35 | 26 |

| >35 - 40 | 28 |

| >40 - 45 | 20 |

| >45 - 50 | 12 |

| >50 + | 60 |

| Total number of cases with time costs | 1,618 |

| Median | 7.0 |

| Mean | 12.6 |

Table 13: Investigation time as % of total time charged

| Original dataset | ||

| No data | 1,099 | |

| 0% | 50 | |

| >0% - 10% | 492 | |

| >10% - 20% | 484 | |

| >20% - 30% | 295 | |

| >30% - 40% | 166 | |

| >40% - 50% | 72 | |

| >50% - 60% | 33 | |

| >60% - 70% | 14 | |

| >70% - 80% | 4 | |

| >80% - 90% | 1 | |

| >90% - 100% | 7 | |

| Total with time charged | 1,618 | |

| Total | 2,717 | |

| Median | 15% | |

| Mean | 2% |

Annex C

Comparison of medians for key metrics between original dataset and additional dataset

| Original dataset | Additional dataset | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | |||

| length of time a case is open (days) | 712 | 436 | |

| Cost | |||

| pre-appointment fee + post-appointment fee as a percentage of assets realised | 163% | 178% | |

| Recovery | |||

| amount paid to creditors as percentage of amount owed | |||

| Fixed charge | 0% | 0% | |

| Floating charge | 0% | 0% | |

| Preferential | 0% | 0% | |

| Unsecured | 0% | 0% | |

| Outcome | |||

| amount paid to creditors as percentage of assets realised | |||

| Fixed charge | 0% | 0% | |

| Floating charge | 0% | 0% | |

| Preferential | 0% | 0% | |

| Unsecured | 0% | 0% |

[1] https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2019/02/04/The-Use-of-Data-in-Assessing-and-Designing-Insolvency-Systems-46549

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/company-insolvency-statistics-october-to-december-2023