Debt Management Report 2025-26 (Accessible)

Updated 2 April 2025

1. Introduction

The ‘Debt management report’ is published in accordance with the ‘Charter for Budget Responsibility’.[footnote 1] The Charter requires the Treasury to “report through a debt management report – published annually – on its plans for borrowing for each financial year” and to set remits for its agents. The Charter requires the report to include:

-

the overall size of the debt financing programme for each financial year

-

the planned maturity structure of gilt issuance and the proportion of index-linked and conventional gilt issuance

-

a target for net financing through National Savings & Investments (NS&I)

The UK Debt Management Office (DMO) publishes detailed information on developments in debt management and the gilt market over the previous financial year in its ‘Annual Review’.[footnote 2]

Chapters 2 and 3, along with Annexes A and B, contain information on the government’s wholesale debt management activities. Information about financing from NS&I is set out in Annex C. The Exchequer cash management remit for 2025-26 is contained in Annex D.

2. Debt Management Policy

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the government’s debt management framework and sets out medium-term considerations for debt management policy. The debt management framework is part of the overall macroeconomic framework, which includes the fiscal, macroprudential, and monetary policy frameworks.

Debt management framework

The debt management framework includes:

-

the debt management objective

-

the principles that underpin the debt management policy framework

-

the roles of HM Treasury and the Debt Management Office (DMO)

-

the full funding rule

Debt management objective

The debt management objective, as set out in the ‘Charter for Budget Responsibility’,[footnote 3] is:

“to minimise, over the long term, the costs of meeting the government’s financing needs, taking into account risk, while ensuring that debt management policy is consistent with the aims of monetary policy.”

While decisions on debt management policy must be taken with a long-term perspective, specific decisions on funding the government’s gross financing requirement are taken annually. Remit decisions are announced in advance of the forthcoming financial year and are typically revised in April (a technical adjustment to reflect outturn data from the previous financial year) and as the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) publishes subsequent fiscal projections. The remits may also be revised at other times in exceptional circumstances. Any such in-year revisions will be announced transparently to the market.

Components of the debt management objective

The costs of meeting the government’s financing needs arise directly from the interest payable on debt (coupon payments and the difference between issuance proceeds and redemption payments) and the operational costs associated with issuance. “Over the long term” refers to the fact that the government expects to issue debt beyond the forecast period. This expectation is reflected in the government’s choice of debt management strategies.

A number of risks are taken into account when selecting possible debt management strategies. Five particularly important risks are:

-

interest rate risk – interest rate exposure arising when new debt is issued

-

refinancing risk – this includes interest rate exposure arising when debt is rolled over, with an increase in risk if redemptions are concentrated in particular years, as well as liquidity and execution risks arising from sizeable redemption payments, particularly if these occur in the near term

-

inflation risk – exposure to inflation, given that principal and coupon payments due on index-linked gilts are indexed to the Retail Prices Index (RPI)

-

liquidity risk – the risk that the government may not be able to borrow freely and smoothly in the required size or manner at a particular time because of insufficient liquidity

-

execution risk – the risk that the government is not able to sell the offered amount of debt at a particular time, or must sell it at a large discount to the market price

These are the major risks that the government has taken into account in recent years and expects to take into account in the future. The weight placed on each risk can change over time. An explanation of how risk is taken into account in determining the DMO’s financing remit for 2025-26 is set out in Annex B.

Debt management policy principles

The debt management objective is achieved by:

-

meeting the principles of openness, predictability, and transparency

-

encouraging the development of a liquid and efficient gilt market

-

issuing gilts that achieve a benchmark premium

-

adjusting the maturity and nature of the government’s debt portfolio

-

offering cost-effective retail financing through NS&I, while balancing the interests of taxpayers, savers, and the wider financial sector

The framework is underpinned by the institutional arrangements for debt management policy as established in 1998 – in particular, the creation of the DMO with responsibility for the implementation and operation of debt management policy.[footnote 4]

Roles of HM Treasury and the DMO

The respective roles of HM Treasury and the DMO are set out in the DMO’s ‘Executive Agency Framework Document’.[footnote 5]

In support of the government’s approach to debt management policy:

-

the DMO will conduct its operations in accordance with the principles of openness, predictability, and transparency

-

HM Treasury and the DMO will explain the basis for their decisions on debt issuance as fully as possible, in order to allow market participants to understand the rationale behind them

-

the DMO will encourage the development of liquid and efficient gilt and Treasury bill markets

HM Treasury sets the annual financing remit using the projected financing requirement, which is calculated on the basis of the OBR’s forecasts for the government’s cash borrowing needs. The DMO has responsibility for announcing the details of its issuance plans to the market, including a planned auction calendar (which sets out the operation dates and type of gilt to be issued).

The full funding rule

An overarching requirement of debt management policy is that the government fully finances its projected financing requirement each year through the sale of debt. This is known as the ‘full funding rule’. The government therefore issues sufficient wholesale and retail debt instruments, through gilts, Treasury bills (for debt financing purposes), and NS&I products, so as to enable it to meet its projected financing requirement in full.

The rationale for the full funding rule is:

-

that the government believes that the principles of transparency and predictability are best met by the full funding of its financing requirement

-

to avoid the perception that financial transactions of the public sector could affect monetary conditions, consistent with the institutional separation between monetary policy and debt management policy

The total amount of financing raised in a financial year will in practice differ from the projected financing requirement. This divergence normally occurs towards the end of the financial year and can be explained by a number of different factors. These include:

-

the difference between the projected central government net cash requirement and its outturn

-

the difference between the projected net contribution to financing from NS&I and other sources, and their respective outturns

-

auction and/or gilt tender proceeds in the period following the Spring fiscal forecast that are different from those required to meet relevant financing targets

-

the implementation of the syndication programme at year-end

The difference will be reflected in a change in the DMO’s cash balance at the end of the financial year. To meet the full funding rule, the government adjusts the projected net financing requirement in the following financial year in order to offset any difference; however, this does not affect the DMO’s cash management operations, which are intended to smooth the government’s cash flows across the financial year (see Annex D). The DMO’s flexibility to vary the stock of Treasury bills for cash management purposes is implemented with full adherence to the full funding rule.

Debt management considerations

Each year, the government assesses the costs and risks associated with different possible patterns of debt issuance, taking into account the most up-to-date information on market conditions and demand for debt instruments.

At present, annual debt management decisions are also made in the context of an elevated level of debt relative to gross domestic product, and an ongoing large gilt redemption profile. Consistent with the long-term focus of the debt management objective, the government takes decisions annually that enhance fiscal resilience by:

-

mitigating refinancing risk; that is, the need to roll over high levels of debt continuously and to avoid concentrating redemptions in particular years, by taking decisions which spread gilt issuance along the maturity spectrum

-

encouraging the liquidity and efficiency of the gilt market

-

maintaining a diversity of exposure, both real and nominal, across the maturity spectrum, reflecting its preference for a balanced portfolio

As a result, subject to cost-effective financing, the government will:

-

have regard to the average maturity of the debt portfolio, in order to limit its exposure to refinancing risk

-

issue an appropriate balance of conventional and index-linked gilts over a range of maturities, taking account of structural demand, the diversity of the investor base, and the government’s preferences for inflation exposure

-

maintain the Treasury bill stock at a level that will support market liquidity and the cash management objective

Index-linked gilts

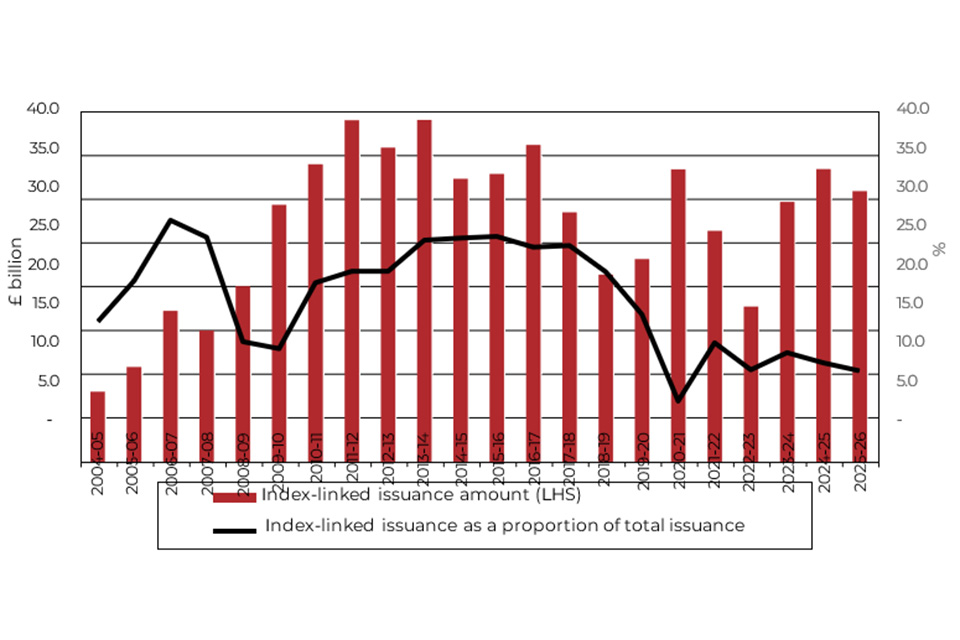

The UK’s stock of index-linked debt stood at around £619 billion at the end of 2024, making up 24.5% of the government’s wholesale debt portfolio (Chart A.10).[footnote 6]

Issuing index-linked gilts has historically brought cost advantages for the government due to strong investor demand. Analysis by the Debt Management Office shows that, for gilts that matured since their introduction in 1981 but prior to January 2025, the government generated direct savings of around £90.8 billion in total from the issuance of index-linked gilts if valued at maturity, or £184.7 billion in 2025 terms.[footnote 7] Issuing index-linked gilts has also built the UK’s financial resilience by supporting both the UK’s long average debt maturity and diversifying the investor base. Tying debt interest payments to RPI has historically helped to underscore the credibility of the government’s commitment to low and stable inflation, particularly during the period prior to central bank independence. The UK’s relatively large stock of index-linked debt does however also increase the sensitivity of the public finances to inflation shocks.

The government decides index-linked gilt issuance on an annual basis, and in practice the share of total issuance will vary from year to year depending on factors including the size of the net financing requirement, demand, and market conditions. In the 2025-26 financing remit, planned index-linked gilt issuance accounts for 10.3% of total gilt issuance.[footnote 8]

Decisions on the precise levels of index-linked and conventional gilt issuance will continue to be taken as part of the annual financing remit and in consultation with market participants.

Sovereign Sukuk

Sukuk are financial certificates, similar to bonds, but which comply with the principles of Islamic finance. In March 2021, the government issued its second UK sovereign Sukuk, raising £500 million. The Sukuk took an al-Ijara structure and will mature in July 2026. The government has no plans to issue further sovereign Sukuk in 2025-26.

The issuance of sovereign Sukuk is not part of the government’s regular debt management programme but is instead intended to deliver wider benefits, including reinforcing London’s status as the leading centre for Islamic finance outside the Islamic world, supporting greater financial inclusion in the UK, and promoting greater trade and investment into the UK.

Green gilts and retail Green Savings Bonds

The government launched the UK’s Green Financing Programme with the publication of the Green Financing Framework (‘the Framework’) in June 2021.[footnote 9] The government also launched the world’s first sovereign retail Green Savings Bond (GSB), tied to the same framework as green gilts, through NS&I, in October 2021. The GSB is a three-year fixed-term savings product.[footnote 10] Under the Green Financing Programme, the government has raised £47.9 billion through the sale of green gilts, via the DMO, and retail Green Savings Bonds (GSB), via NS&I.[footnote 11] There are currently two green gilts in issue – 0⅞% Green Gilt 2033 and 1½% Green Gilt 2053.

In 2024-25, the DMO raised £10.0 billion across six transactions. The focus in the last three financial years has been on re-opening the existing green gilts, in order to build up liquidity.

The government plans to issue £10.0 billion of green gilts in 2025- 26, subject to demand and market conditions.

The GSB has been repriced several times in response to market developments and to meet the requirements of the Green Financing Programme. Issue 7 was launched in January 2024, with an interest rate of 2.95%. NS&I estimates a total of £1.9 billion to have been invested in GSB since its initial October 2021 launch.

In October 2024 the first GSBs issued began to mature. At maturity, customers have the option to either reinvest in GSB (or another NS&I product) or withdraw their investment. As a result of this, NS&I forecasts £166.0m of outflows against forecast inflows of £7.0 million in 2024-25. Financing raised through GSB is monitored throughout the year to ensure the requirements of the Green Financing Programme can be met and that funds raised remain balanced against proceeds from green gilts.

Proceeds from the GSB are additional to NS&I’s annual Net Financing remit but they do contribute to the overall gross financing requirement – and have been reported alongside the financing arithmetic in Chapter 3 and Annex C.

On 17 October 2024, HM Treasury published the third annual Allocation Report for the Programme.[footnote 12] It presents allocation data from 39 expenditures financed by the Programme in financial year 2023-24.

Digital Gilt Instrument

The Chancellor of the Exchequer announced at Mansion House on 14 November 2024 that the government intends to launch a pilot digital gilt instrument (DIGIT) issuance. This was followed by further details being announced by the Economic Secretary to the Treasury on 18 November, and the launch of the Preliminary Market Engagement Notice on 18th March.[footnote 13]

‘Distributed ledger technology’ (DLT) refers to a variety of technologies characterised by their use of networks of ledgers that update and synchronise simultaneously. The pilot intends to utilise the Digital Securities Sandbox (DSS), which opened for applications in September 2024 and allows UK firms to develop and test DLT in a temporary regulatory environment. This issuance will support the government’s commitment to maintaining the UK as a world-leading and global financial centre.

The government is working with the financial services sector to test this new technology across the life cycle of a government debt instrument. This will enable the government to explore the potential benefits that DLT could bring to the debt issuance process, as well as stimulating the wider development of DLT platforms and infrastructures across UK capital markets.

The pilot is experimental in nature and, therefore, will be independent of our existing debt management programme.

Borrowing by devolved administrations

The Scottish and Welsh governments and the Northern Ireland Executive have the power to borrow for capital investment, as set out in the Scotland Act 1998,[footnote 14] Government of Wales Act 2006,[footnote 15] and Northern Ireland (Loans) Act 1975,[footnote 16] respectively. The Scottish and Welsh governments’ capital borrowing powers were updated in the ensuing Scotland Act 2016 and Wales Act 2017, with further detail set out in their respective fiscal frameworks. The Northern Ireland Executive’s borrowing powers were updated in the Northern Ireland (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 2006.

All three devolved administrations can borrow for capital investment from the National Loans Fund. The Scottish and Welsh governments also have the power to borrow from commercial lenders and issue bonds to finance capital investment. The Scottish and Welsh governments will be solely responsible for meeting their liabilities and the UK government will provide no guarantee on any bonds issued by the Scottish and Welsh governments. If there is an increase in the Scottish or Welsh government’s borrowing limits, the UK government will also review devolved administrations’ powers to issue bonds. In addition, the Scottish and Welsh governments would need further approval from HM Treasury to issue in any currency other than sterling.

Borrowing by local authorities

Under the prudential code, each local authority is responsible for meeting its own liabilities, including those taken on through extending guarantees. The UK government provides no guarantee on local authority borrowing.

Local authority capital financing decisions are subject to prudential guidance as published by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA), the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG), the Scottish Government, and the Welsh Government. Taken together, these documents form the prudential framework.

Local authorities undertake the majority of their borrowing via the Public Works Loan Board (PWLB), which is overseen by HM Treasury. In recent years, HM Treasury has updated the guidance on the terms of lending to ensure that PWLB loans are not diverted into financial investments that serve no direct policy purpose, and to address lending to authorities where there is a more than negligible risk of non-repayment. Local authorities are also now able to borrow from the National Wealth Fund to deliver economic infrastructure projects in the UK.

3. The Debt Management Office’s financing remit for 2025-26

Introduction

The financing arithmetic sets out the components of the gross financing requirement (GFR) and the DMO’s net financing requirement (NFR) as well as the contributions from various sources of financing. The DMO’s financing remit sets out how the DMO, acting as the government’s agent, will finance the projected NFR.

Financing arithmetic

The OBR’s forecast for the central government net cash requirement (excluding NRAM Ltd, Bradford & Bingley, and Network Rail) (CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR)) in 2025-26 is £142.7 billion. This is the fiscal aggregate that determines gross debt sales and is derived from public sector net borrowing (PSNB).

The forecast NFR in 2025-26 of £304.2 billion also reflects: projected gilt redemptions of £168.2 billion; a planned short-term financing adjustment of £6.7 billion resulting from unanticipated underfinancing in 2024-25; and other financing items of £1.8 billion.

Proceeds from NS&I are expected to make a £12.0 billion (within a range of ± £4.0 billion) net contribution to financing in 2025-26 (excluding Green Savings Bonds (GSBs)), following a forecast net contribution of £10.5 billion in 2024-25. Projected net financing of £12.0 billion (± £4.0 billion) in 2025-26 assumes gross inflows to NS&I products of £50.1 billion. In addition to NS&I’s net financing contributions, NS&I expect to have attracted inflows of £7.0 million from the sale of GSB in 2024-25. Accounting for withdrawals, NS&I expect to have raised £1.7 billion of inflows since the initial October 2021 launch to March 2025. Net GSB flows are projected to be -£0.2 billion in 2024-25. This is reflected in the financing arithmetic for 2024-25. Full details of NS&I’s Net Financing target are set out in Annex C.

The 2025-26 NFR is planned to be met by gilt issuance of £299.2 billion and net issuance of Treasury bills for debt financing purposes of £5.0 billion.

Table 3.A sets out details of the financing arithmetic for 2024-25 and 2025-26.

Table 3.A: Financing arithmetic in 2024-25 and 2025-26 (£ billion)(1)

| 2024-25 | 2025-26 | |

|---|---|---|

| CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR)(2) | 172.6 | 142.7 |

| Gilt redemptions(3) | 139.9 | 168.2 |

| Financing adjustment carried forward from previous financial years(4) | 6.5 | 6.7 |

| Gross financing requirement | 319.0 | 317.7 |

| less: | ||

| NS&I Net Financing(5) | 10.5 | 12.0 |

| NS&I Green Savings Bonds(5) | -0.2 | -0.3 |

| Other financing(6) | 2.1 | 1.8 |

| Net financing requirement (NFR) for the DMO | 306.6 | 304.2 |

| DMO’s NFR will be financed through: | ||

| Gilt sales, through sales of: | ||

| Short conventional gilts | 103.8 | 110.9 |

| Medium conventional gilts (including green gilts)(7) | 92.0 | 89.7 |

| Long conventional gilts (including green gilts)(8) | 59.2 | 40.2 |

| Index-linked gilts | 33.4 | 30.9 |

| Unallocated amount of gilts | 8.5 | 27.5 |

| Total gilt sales for debt financing(9) | 296.9 | 299.2 |

| Total net contribution of Treasury bills for debt financing | 3.0 | 5.0 |

| Total financing | 299.9 | 304.2 |

| DMO net cash position | -4.4 | 2.3 |

| 1: Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

| 2: Central government net cash requirement (excluding NRAM Ltd, Bradford & Bingley, and Network Rail). |

| 3: Gilt redemptions do not reflect the full value of inflation uplift on index-linked gilts because accrued inflation uplift on any redeeming gilts is split between redemptions and the CGNCR. Specifically, where an index-linked gilt is re-opened (following an initial issue) any inflation uplift on that gilt accrued before the re-opening will be treated as principal (and therefore part of the redemption total). Any inflation uplift that occurs after the re-opening of the gilt will be treated as a return to the investor and thus will be included within the CGNCR for the year in which the gilt matures. |

| 4: The £6.5 billion financing adjustment in 2024-25 carried forward from previous years reflects the 2023-24 CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR), as first published on 23 April 2024. The £6.7 billion adjustment in 2025-26 is the amount required to restore the estimated DMO net cash position at end-March 2026 to £2.3 billion. |

| 5: These figures are forecasts based on current performance but are subject to change throughout the remainder of the financial year. Outturn will be confirmed in NS&I’s 2024-25 Annual Report and Accounts, which are to be published in the summer. For further detail on outflows from Green Savings Bonds please see Chapter 2. |

| 6: This financing item is typically comprised of estimated income from coinage and unhedged reserves. |

| 7: Including green gilt sales of £6.7 billion in 2024-25 and planned green gilt sales in 2025-26. |

| 8: Including green gilt sales of £3.3 billion in 2024-25 and planned green gilt sales in 2025-26. |

| 9: Gilt sales figures as at Autumn Budget 2024 have been used for 2024-25. The outturn amounts will be published at the technical remit adjustment following publication of the 2024-25 cash outturn in April 2025. |

Source: Debt Management Office, HM Treasury, NS&I, and Office for Budget Responsibility.

Other short-term debt

The Ways and Means facility functions as the government’s overdraft account with the Bank of England.[footnote 17] Ordinarily, a standing negative balance of around £0.4 billion is maintained at all times to support Exchequer cash management. It is planned to remain at around £0.4 billion in 2025-26.

The projected level of the DMO’s net cash balance at 31 March 2025 is -£4.4 billion, £6.7 billion below the level projected at Autumn Budget 2024.[footnote 18] The level will be increased to £2.3 billion during 2025- 26, as shown by the planned short-term financing adjustment of £6.7 billion, and this will in turn increase the NFR in 2025-26 accordingly.

Gilt issuance by method, type, and maturity

Auctions will remain the government’s primary method of gilt issuance. In addition, the government will continue issuance via syndications and gilt tenders. Any type and maturity of gilts can be issued via syndication or gilt tender.[footnote 19] Further details are set out in the DMO’s 2025-26 financing remit announcement.

The government currently plans to raise £10.0 billion by sales of green gilts in 2025-26.

The government plans gilt sales via auction of £231.7 billion (or 77.4% of total issuance) which is currently planned to be split by maturity[footnote 20] and type as follows:

-

£110.9 billion of short-dated conventional gilts (37.1.% of total issuance).

-

£73.7 billion of medium-dated conventional gilts (24.6% of total issuance).

-

£26.7 billion of long-dated conventional gilts (8.9% of total issuance).

-

£20.4 billion of index-linked gilts (6.8% of total issuance).

The government is also currently planning to sell approximately £40.0 billion of gilts (13.4% of total issuance) via syndication. The DMO’s remit announcement sets out further detail about the planned syndication programme.

In addition, the DMO’s financing remit includes an initially unallocated portion of £27.5 billion (9.2.% of total issuance), through which gilts of any type or maturity may be sold, via any issuance method.

The deployment of the unallocated amount of gilt sales is designed to facilitate the effective delivery of the gilt financing programme while remaining consistent with the debt management principles of openness, predictability, and transparency.

To maintain the operational viability of syndicated offerings at the end of each financial year, the overall cash size of the syndication programmes (conventional and/or index-linked gilts but not green gilts) may be increased by up to 10% at the time of the final syndicated offering of each type.

Gilt sales from either the syndication or auction programmes at any maturity sector may vary from a broadly even-flow delivery during the financial year. Proceeds raised following the final transaction of each syndication programme may also vary from the planned total for each programme. Any variations of this nature may lead to a minor adjustment to the type and maturity of gilts sold via any issuance method towards the end of the financial year.

Through its gilt issuance programme, the government aims to achieve regular issuance across the maturity spectrum throughout the financial year and to build up benchmarks at key maturities in both conventional and index-linked gilts.

The current planning assumption for gilt issuance in 2025-26 by type, maturity, and issuance method is shown in Table 3.B.

Table 3.B Breakdown of currently planned gilt issuance in 2025-26 by type, maturity, and issuance method (£ billion and % of total)(1)

| Auction | Syndication | Gilt tender | Unallocated | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short conventional | 110.9 | 110.9 (37.1%) | |||

| Medium conventional(2) | 73.7 | 16.0 | 89.7 (30.0%) | ||

| Long conventional(3) | 26.7 | 13.5 | 40.2 (13.4%) | ||

| Index-linked | 20.4 | 10.5 | 30.9 (10.3%) | ||

| Unallocated | 27.5 | 27.5 (9.2%) | |||

| Total | 231.7 (77.4%) | 40.0 (13.4%) | 0.0 (0.0%) | 27.5 (9.2%) | 299.2 |

| 1: Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

| 2, 3: Including planned green gilt sales. |

Source: DMO.

Gilt auction calendar

Alongside this report, the DMO has published a planning assumption for the gilt auction calendar that is consistent with the remit.[footnote 21] The planned auction calendar may be adjusted during the year. The DMO will explain the parameters for this alongside the publication of the auction calendar.

Post-Auction Option Facility (PAOF)

In 2025-26, the DMO will continue to offer successful bidders at auction (both primary dealers and investors) the option to purchase additional stock. The details of how this facility works are set out in the DMO’s gilt market Operational Notice.[footnote 22] The PAOF will however not be applicable to any auctions of green gilts, reflecting the requirement that proceeds from green gilt issuance must not exceed the available amount of eligible green spending in the relevant period.

The Standing Repo Facility

For the purposes of market management, the DMO may create and repo out gilts in accordance with the provisions (which are revised from time to time) of its Standing Repo Facility, as launched on 1 June 2000.[footnote 23] Any such gilts created will not be sold outright to the market and will be cancelled on return.

Other operations

The DMO has no current plans for a programme of reverse or switch auctions, or conversion offers, in 2025-26.

Coupons

As far as possible, the DMO will set coupons on new issues to price any new gilt close to par at the time of issue.

Purchases of short maturity debt

The DMO may buy in gilts that are close to their final maturity date in order to help manage Exchequer cash flows.

Treasury bill issuance

It is currently planned that Treasury bill issuance for debt financing purposes will make a £5.0 billion net contribution to debt financing in 2025-26. The amount that Treasury bills have contributed to debt financing up to, and including, 2024-25 will be reported by the DMO shortly after the end of 2024-25.

New gilt instruments

There are no current plans to introduce new types of gilt instruments in 2025-26. Work is underway to develop the Digital Gilt Instrument (DIGIT), which will sit separately from the standard debt programme.

Revisions to the remit

In addition to planned updates to the remit, any aspect of this remit may be revised during the year in light of relevant new information. For example, this might include revisions in response to substantial changes in the following:

-

the government’s forecast for the NFR

-

the level and/or shape of the gilt yield curves

-

market expectations of future interest and inflation rates

-

market volatility

Any such in-year revisions will be announced transparently to the market.

Medium-term projections for annual financing requirements

Table 3.C shows projections for financing requirements in the fiscal forecast period. The financing requirements include the forecast path for CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR) and the gilt redemption profile. These projections are not forecasts of future gilt sales. Rather, they are a broad indication of future finance to be raised through a combination of gilt sales, Treasury bills, NS&I, and other financing sources. Table 3.C sets out the financing requirement projections from 2024-25 to 2029-30.

Table 3.C Financing requirement projections, 2026-27 to 2029-30 (£ billion)(1)

| 2026-27 | 2027-28 | 2028-29 | 2029-30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR)(2) | 129.1 | 137.5 | 137.4 | 109.2 |

| Currently projected redemptions(3) | 141.5 | 128.1 | 146.6 | 92.7 |

| Illustrative gross financing requirement | 270.6 | 265.6 | 284.1 | 201.9 |

| 1: Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

| 2: Central government net cash requirement (excluding NRAM Ltd, Bradford & Bingley, and Network Rail). |

| 3: Projected redemptions reflect the amounts of gilts currently in issue (net of government holdings) in these financial years. Includes gilt auction sizes announced up to Spring Statement 2025. To the extent that further gilt issuance of bonds redeeming within the forecast period occurs, these amounts will increase accordingly. In financial years in which index-linked gilt redemptions take place, the nominal amount in issue (excluding any government holdings) will form part of the redemption total, whereas the inflation uplift will be split between the redemption total and the CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR). |

Source: DMO, HM Treasury, and OBR.

Annex A: Debt Portfolio

The total nominal outstanding stock of central government sterling wholesale debt excluding official holdings was £2,522.4 billion at end-December 2024.[footnote 24] The components of this stock are set out in Table A.1.

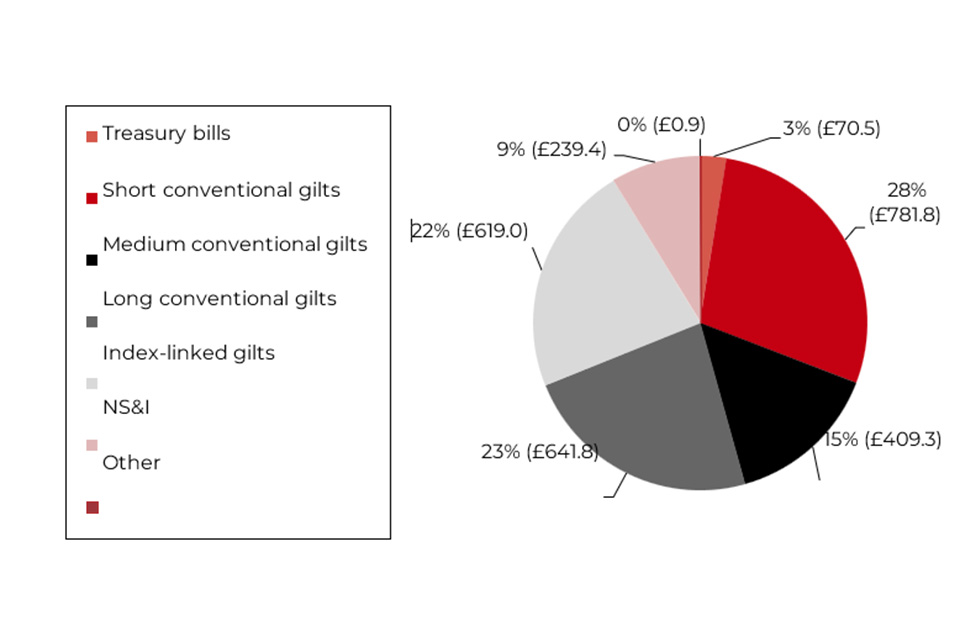

Chart A.1 shows the composition of the government’s debt portfolio at end-December 2024.[footnote 25] Conventional and index-linked gilts made up the largest proportion of government debt (totalling 89%).

Chart A.1 Composition of central government sterling debt in % and £ billion (end-December 2024)(1),(2)

Chart A.1 Composition of central government sterling debt in % and £ billion (end-December 2024)

| 1: Figures may not sum due to rounding. Nominal uplifted values. |

| 2: Other is comprised of Ways and Means and Sukuk. |

Source: DMO, HM Treasury, and NS&I.

Table A.1 Composition of central government wholesale and retail debt(1)

| £ billion nominal value | End-December 2023 | End-December 2024 |

|---|---|---|

| Wholesale | ||

| Conventional gilts | 1,834.5 | 1,996.9 |

| Less government holdings | 151.2 | 164.0 |

| 1,683.4 | 1,832.9 | |

| Index-linked gilts | 382.0 | 393.5 |

| less government holdings | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| plus accrued inflation uplift | 230.8 | 227.6 |

| 610.0 | 619.0 | |

| Treasury bills for debt management | 69.5 | 70.5 |

| Total wholesale debt | 2,362.8 | 2,522.4 |

| Retail | ||

| NS&I | 231.4 | 239.2 |

| Other | ||

| Balance on Ways and Means Advance | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| Sovereign Sukuk | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Total central government sterling debt | 2,595.1 | 2,762.7 |

| Other government debt less liquid assets | 100.7 | 60.0 |

| Public sector net debt | 2,695.8 | 2,822.7 |

| Public sector net debt to GDP (%)(2) | 97.0% | 97.2% |

| Wholesale debt | ||

| Wholesale debt to GDP (%)(2) | 87.8% | 88.6%(3) |

| Average time to maturity (years)(4) | 14.3 years | 14.0 years |

| Debt maturing in one year (%) | 9.2% | 9.9% |

| 1: Figures may not sum due to rounding. |

| 2: Adjusted to GDP centred on end-December. |

| 3: GDP figures for 2024 includes quarterly estimate for Q4. |

| 4: Calculated on a nominal weighted basis, excluding government holdings, including accrued inflation uplift and Treasury bills for debt management purposes. |

Source: DMO, NS&I, OBR, and ONS

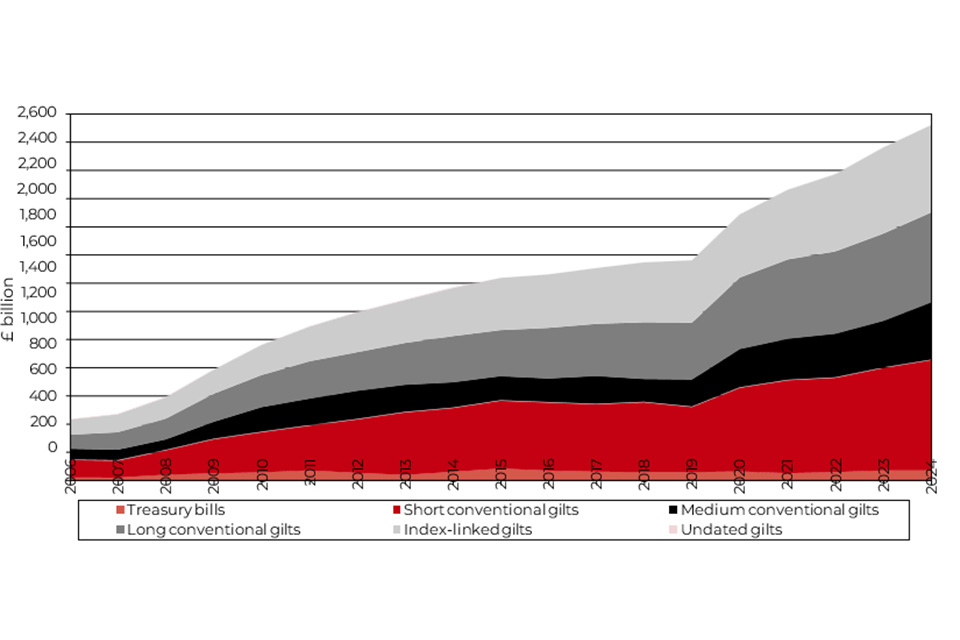

Chart A.2 shows the evolution of the wholesale government debt stock over time. Conventional gilts continue to make up the largest share of the gilt stock.

Chart A.2 Composition of central government wholesale debt stock, 2006-2024 (end-December values)

Chart A.2 Composition of central government wholesale debt stock, 2006-2024 (end-December values)

Source: DMO.

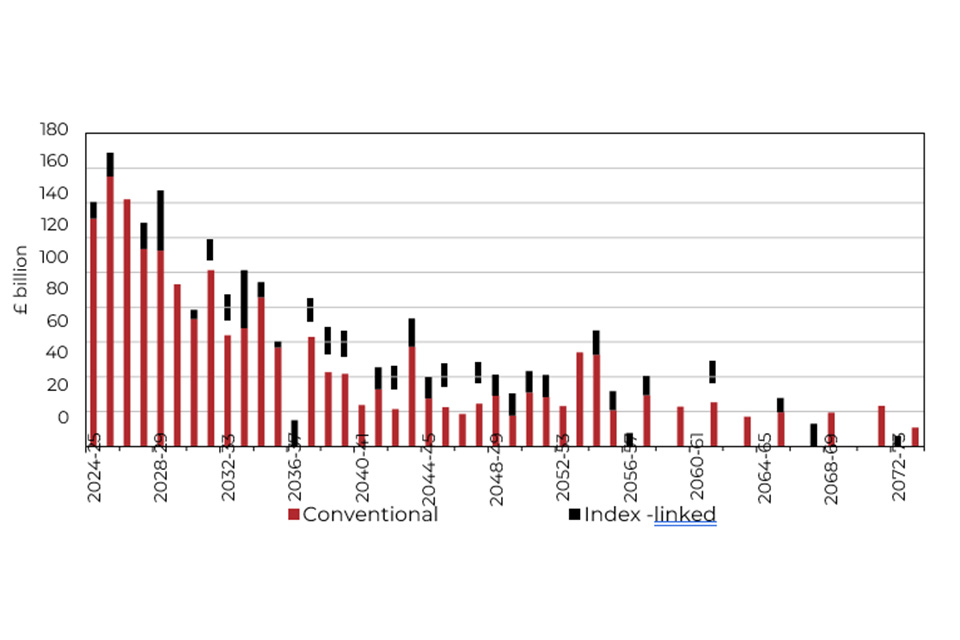

Chart A.3 shows the government’s gilt redemption profile as of 24 March 2025. The longest maturity gilt in issue is due to redeem in the 2073-74 financial year. The longest maturity index-linked gilt will mature in 2072-73.

Chart A.3 Gilt redemption profile (as of 24 March 2025)

Chart A.3 Gilt redemption profile (as of 24 March 2025)

Source: DMO.

Maturity and duration of the debt stock

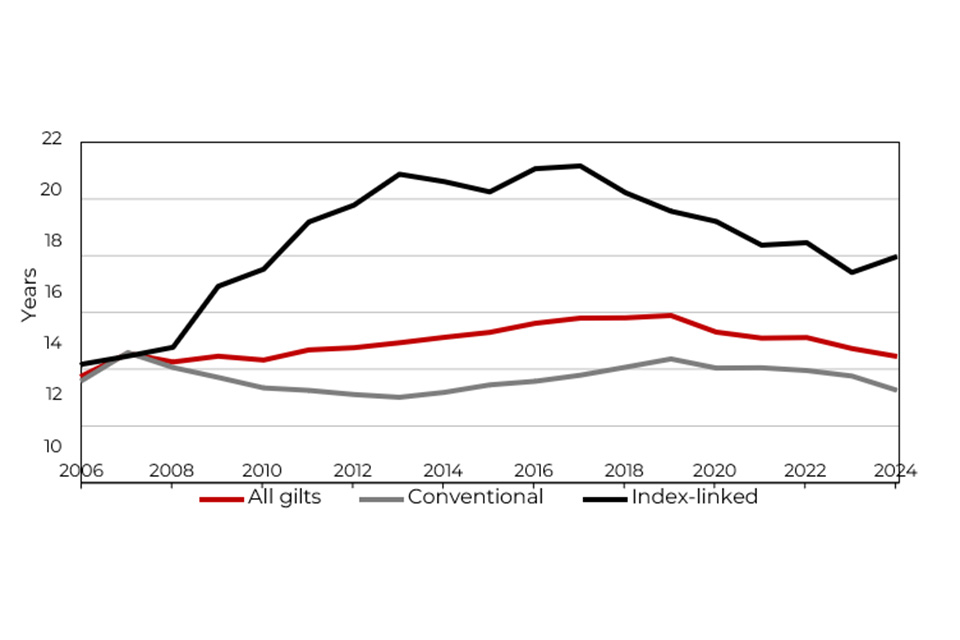

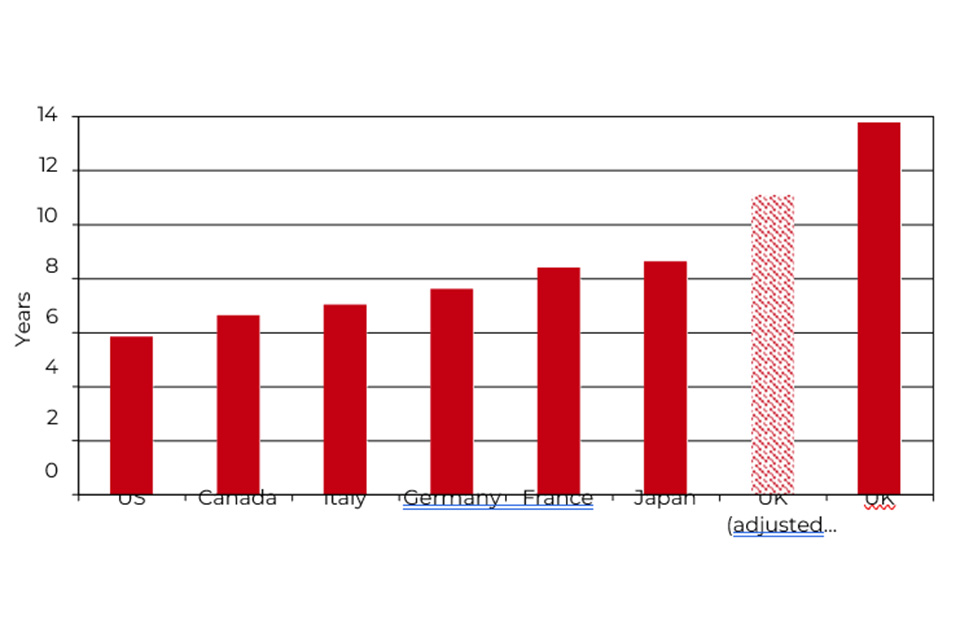

At end-December 2024, the average maturity of the total stock of gilts was 14.4 years, as shown in chart A.4. The average maturity of the stock of conventional gilts fell from 13.7 years at end-2023 to 13.2 years at end-2024. The average maturity of index-linked gilts rose slightly, from 17.4 years at end-2023 to 18.0 years at end-2024. The average maturity of the government’s wholesale marketable debt remains consistently longer than the average across the G7 group of advanced economies, as shown in Chart A.5. This remains true even after adjusting the UK figure for the impacts of Quantitative Easing (QE), where the Bank of England purchased gilts from March 2009 to December 2021, and without applying any QE adjustment to other countries which will also face significant QE effects.[footnote 26] This effect on maturity is now unwinding as QE unwinds which will increase the UK’s effective debt maturity, all else equal. A long average maturity of debt significantly reduces the UK government’s exposure to refinancing risk, by enabling gilt issuance and redemptions to be spread along the maturity spectrum.

Chart A.4 Average maturity of UK gilt stock (end-December 2024 values)(1)

Chart A.4 Average maturity of UK gilt stock (end-December 2024 values)

| 1: Calculated on a nominal weighted basis, excluding official holdings, including accrued inflation uplift. |

Source: DMO.

Chart A.5 Average maturity of the debt stock by country (end- December 2024)(1)

Chart A.5 Average maturity of the debt stock by country (end- December 2024)

| 1: Calculated on a nominal weighted basis, excluding inflation uplift, including Treasury bills using Bloomberg. QE adjusted figure based on HMT calculations using DMO and Bank of England data, excludes inflation uplift and includes Treasury bills for debt management purposes. |

Source: Bloomberg L.P., Bank of England, and HM Treasury calculations.

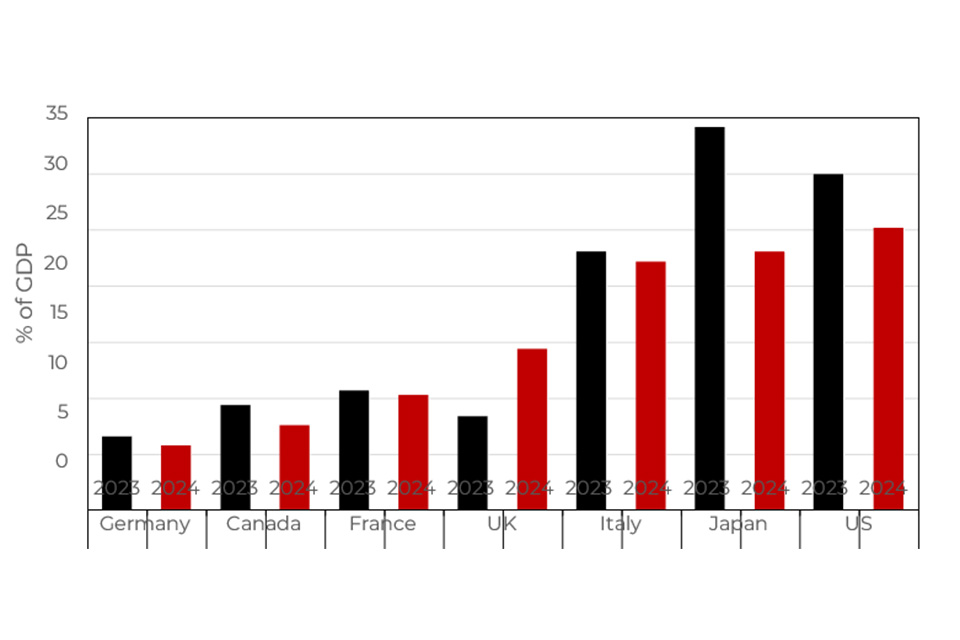

Chart A.6 shows the expected gross financing requirement as a share of GDP for all G7 countries in 2023 and 2024. [footnote 27]

Chart A.6 Annual gross financing requirement as a % of GDP

Chart A.6 Annual gross financing requirement as a % of GDP

Source: IMF Fiscal Monitor October 2023-2024.

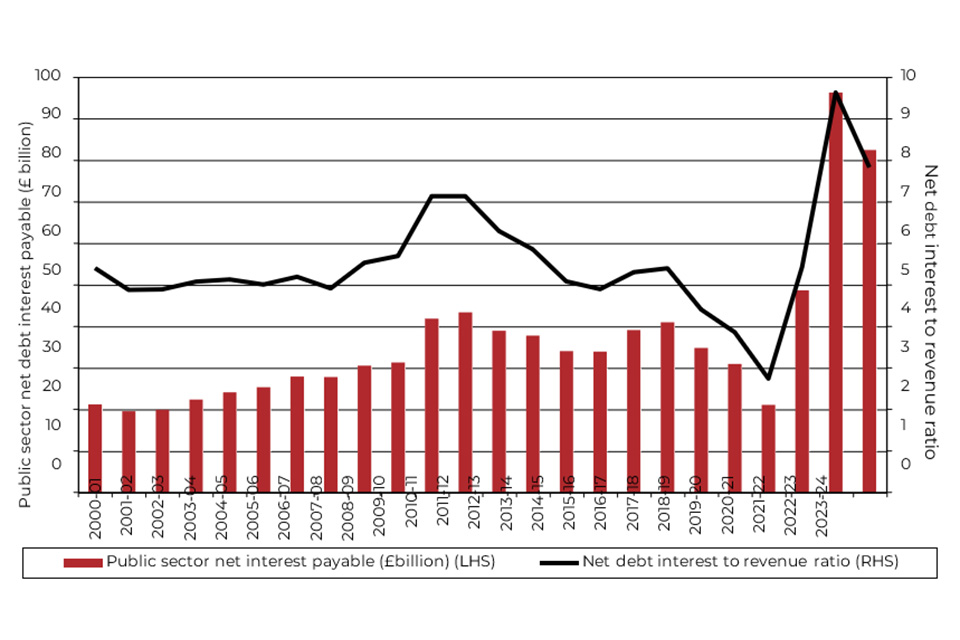

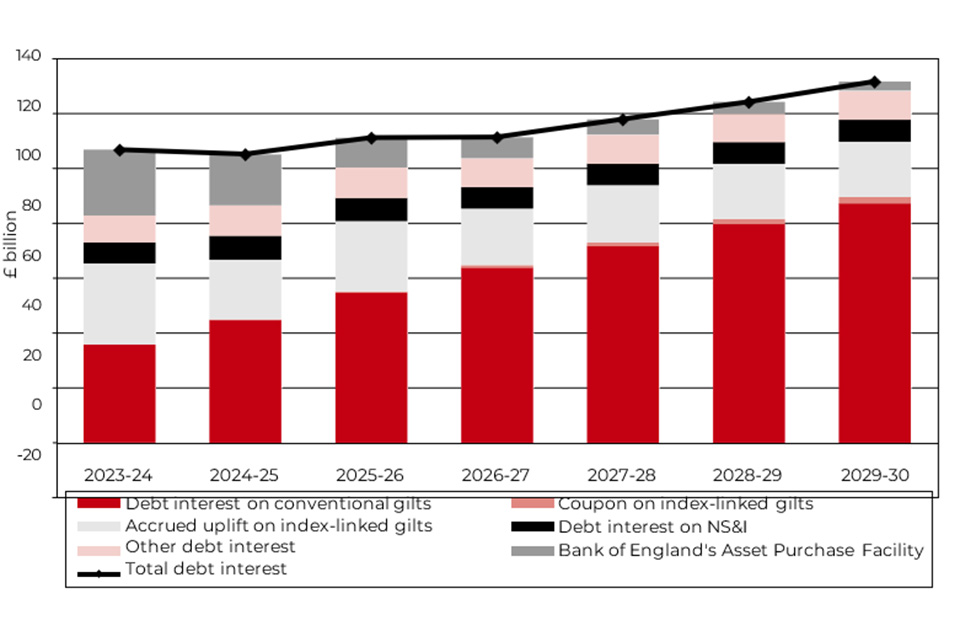

Debt Interest

Public sector net debt interest spending fell in 2023-24 after a significant rise in 2022-23, as shown in Chart A.7. Total gross debt interest spending is forecast by the OBR to reach £87 billion in 2024-25. Central government debt interest (net of the APF) in 2024-25, at £105 billion, is forecast to be broadly the same as the previous year, as shown in Chart A.8. This higher level of debt interest is forecast to persist throughout the next few years due primarily to increased interest rates but also as a result of high projected borrowing requirements.

Chart A.7 Net debt interest in £ billion and as % of public sector receipts(1)

Chart A.7 Net debt interest in £ billion and as % of public sector receipts1

| 1: The debt interest presented in this chart is public sector debt interest expenditure net of interest and dividends receipts, all on an accrued basis. This reflects the use of debt liabilities to purchase financial assets which provide a rate of return. |

Source: ONS

Chart A.8 Breakdown of gross debt interest forecast(1)

Chart A.8 Breakdown of gross debt interest forecast

| 1: Gross debt interest reflects the instruments issued as outlined in the outturn financing remits and forward projections. This aggregate does not include any negative debt interest from the Asset Purchase Facility nor from any financial assets held by government. |

Source: HM Treasury calculations and OBR.

Gilt holdings by sector

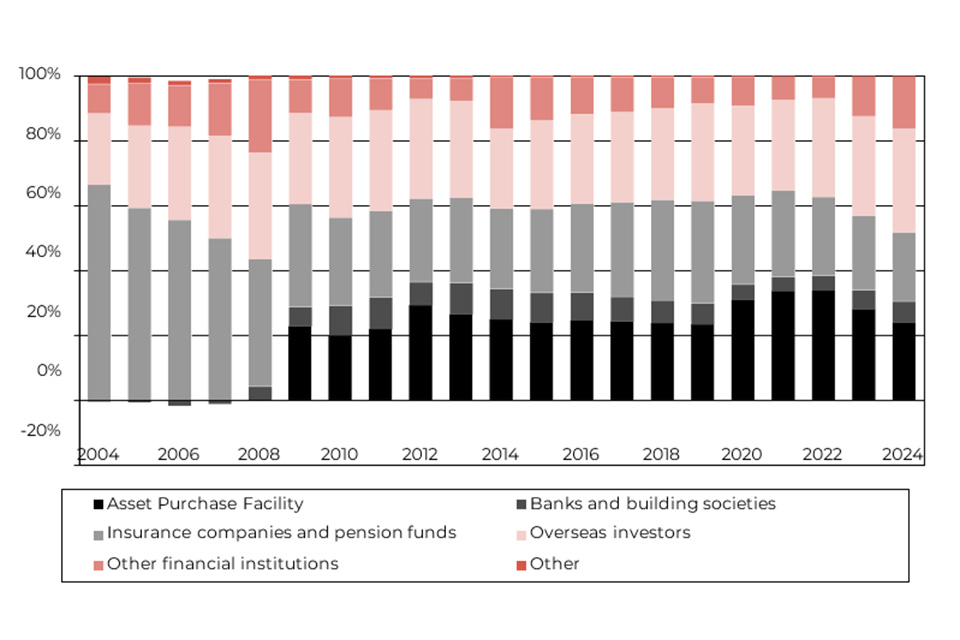

At end-September 2024, the largest investor groups in gilts continued to be overseas investors (32% of total gilt holdings), the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (24%), and insurance companies and pension funds (21%), as shown in Chart A.9.

Chart A.9 Gilt holdings by sector (% of total market value gilt holdings)(1)

Chart A.9 Gilt holdings by sector (% of total market value gilt holdings)

| 1: All end-December data, except 2024, for which data are only available until end-September. The Bank of England’s holdings of gilts which are not related to the Asset Purchase Facility are included in the ‘Banks and building societies’ category. |

Source: ONS and Bank of England.

The introduction of quantitative easing (QE) through the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) has caused the largest change to gilt holdings by sector over time, as shown in Chart A.9. Between its introduction in March 2009 and the last QE gilt purchases in December 2021, the stock of gilts held in the APF increased to £875bn. In February 2022, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) voted to begin unwinding the stock of gilts held in the APF by ceasing to reinvest maturing gilts. In September 2022, the MPC voted to begin active sales of gilts, which began in November 2022. In September 2024, the MPC voted to unwind the gilts held in the APF by £100bn in the following 12 months, comprising both active sales and passive unwind as gilts mature. Since its peak in December 2021, the size of the APF has been reduced by around 30% (in purchase proceeds terms). The market value of holdings in the APF has also decreased: as of end-February 2025, gilt holdings in the facility stood at around £473.7 billion.

Gilt issuance

The central government net cash requirement (excluding NRAM Ltd, Bradford & Bingley, and Network Rail) (CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR)), gilt redemptions, and the volume of gilt sales for each financial year since 2008-09 are shown in Table A.2.

Table A.2 Central government net cash requirement, redemptions and gilt sales (£ billion)

| CGNCR (ex NRAM, B&B, and NR)(1) | Redemptions | Gross gilt sales(2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-09 | 162.4 | 18.3 | 146.5 |

| 2009-10 | 198.8 | 16.6 | 227.6 |

| 2010-11 | 139.6 | 38.6 | 166.3 |

| 2011-12 | 126.5 | 49.0 | 179.4 |

| 2012-13 | 98.6 | 52.9 | 165.1 |

| 2013-14 | 79.3 | 51.5 | 155.4 |

| 2014-15 | 92.3 | 64.5 | 126.4 |

| 2015-16 | 78.5 | 70.2 | 127.7 |

| 2016-17 | 71.1 | 69.9 | 147.6 |

| 2017-18 | 40.7 | 79.5 | 115.5 |

| 2018-19 | 36.9 | 66.7 | 98.6 |

| 2019-20 | 55.8 | 99.1(4) | 137.9 |

| 2020-21 | 334.5 | 97.6 | 485.8 |

| 2021-22 | 129.2 | 79.3 | 194.7 |

| 2022-23 | 115.4 | 107.1 | 169.5 |

| 2023-24 | 158.8 | 117.0 | 239.1 |

| 2024-25(3) | 172.6 | 139.9 | 296.9 |

| 2025-26(3) | 142.7 | 168.2 | 299.2 |

| 1: Central government net cash requirement (excluding NRAM, Bradford and Bingley, and Network Rail). |

| 2: Figures are in cash terms. |

| 3: Spring Statement 2025 projections. |

| 4: Includes £0.2 billion for the redemption of the 2014 sovereign Sukuk in 2019-20. |

Source: DMO, HM Treasury, ONS, and OBR.

Index-linked gilts

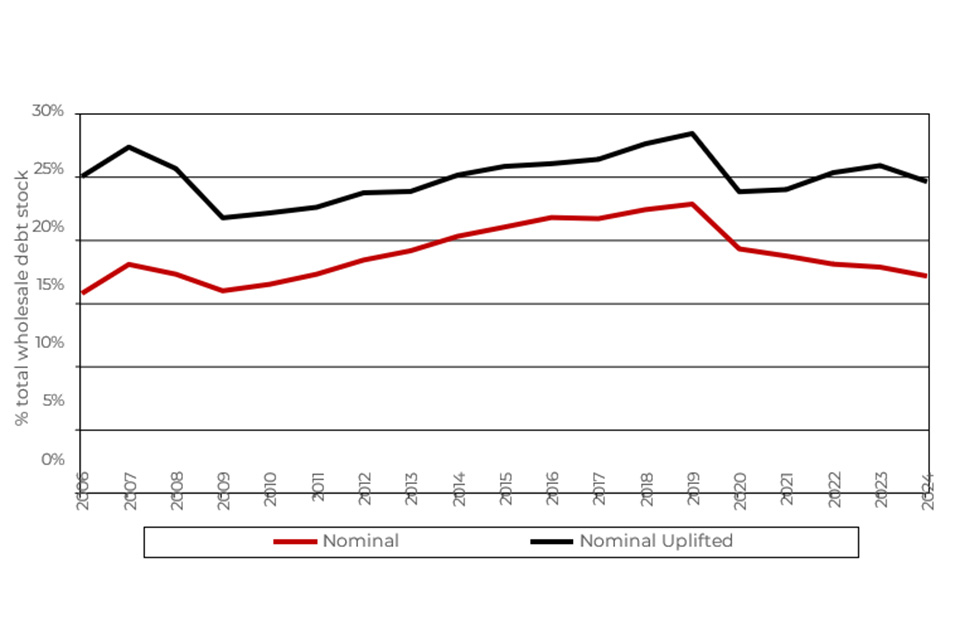

The stock of index-linked gilts has increased over time and stood at around £619.0 billion in nominal uplifted terms at the end of 2024. Index-linked gilts make up 24.5% of the government’s debt portfolio in nominal uplifted terms (Chart A.10). The proportion of index-linked debt in the government’s wholesale debt portfolio is higher than across the G7 group of advanced economies and is around twice as large as the second highest G7 country.[footnote 28] This is largely owing to the historical high level of structural demand for such instruments in the UK, from the domestic pensions sector in particular.

Chart A.10 Index-linked proportion (share of the wholesale debt stock)(1)

Chart A.10 Index-linked proportion (share of the wholesale debt stock)

| 1: The term ‘nominal value’ refers to the nominal amount of gilts in issue; the term ‘nominal uplifted’ refers to the nominal amount in issue multiplied by the known inflation uplift on the gilts to date. |

Source: DMO.

Chart A.11 Annual index-linked gilt issuance(1)

Chart A.11 Annual index-linked gilt issuance

| 1: Data up to, and including 2023-24, are outturns. 2024-25 data is based on planned gilt sales as of Autumn Budget 2024. For 2025-26: (i) data are based on initial planned issuance, which is subject to change as the initially unallocated amount of gilts is distributed over the year; and (ii) no assumption is made about in-year transfers from the initially unallocated portion of issuance. |

Source: DMO

Annex B: Context for decisions on the Debt Management Office’s financing remit

Introduction

This annex provides the context for the government’s decisions on gilt and Treasury bill issuance in 2025-26, setting out the qualitative and quantitative considerations that have influenced them.

The government’s decisions on the structure of the financing remit, which are taken annually, are made in accordance with the debt management objective, the debt management framework, and wider policy considerations (see Chapter 2).

In determining the overall structure of the financing remit, the government assesses the costs and risks of debt issuance by maturity and type of instrument. Decisions on the composition of debt issuance are also informed by an assessment of investor demand for debt instruments by maturity and type as reported by stakeholders, and as manifested in the shape of the nominal and real yield curves, as well as the government’s appetite for risk.

Alongside these considerations, the government takes into account the practical implications of issuance (for example, the scheduling of operations throughout the year).

Demand

Both Gilt-edged Market Makers (GEMMs) and investors have reported ongoing support for the current design of the issuance programme, which has helped to support market functioning.

At the annual consultation meetings with the Economic Secretary to the Treasury in January 2025, market feedback noted the continued shift in gilt demand from investors, in particular noting declining demand from the defined benefit pension sector at longer maturities. As such, attendees expressed support for the DMO to reduce long conventional issuance in 2025-26 relative to 2024-25, whilst increasing the proportion of short- and medium-dated conventional gilts.

Feedback from market participants also suggested that the proportion of index-linked gilts should be maintained at broadly the same level as in 2024-25, or perhaps reduced given lesser pension fund demand.

Demand for Treasury bills is expected to be strong in 2025-26, with some market feedback suggesting that the size of the Treasury bill programme could be increased relative to the current year.

Good investor appetite for further green gilt issuance was also reported, with market feedback supporting the continuation and expansion of the programme.

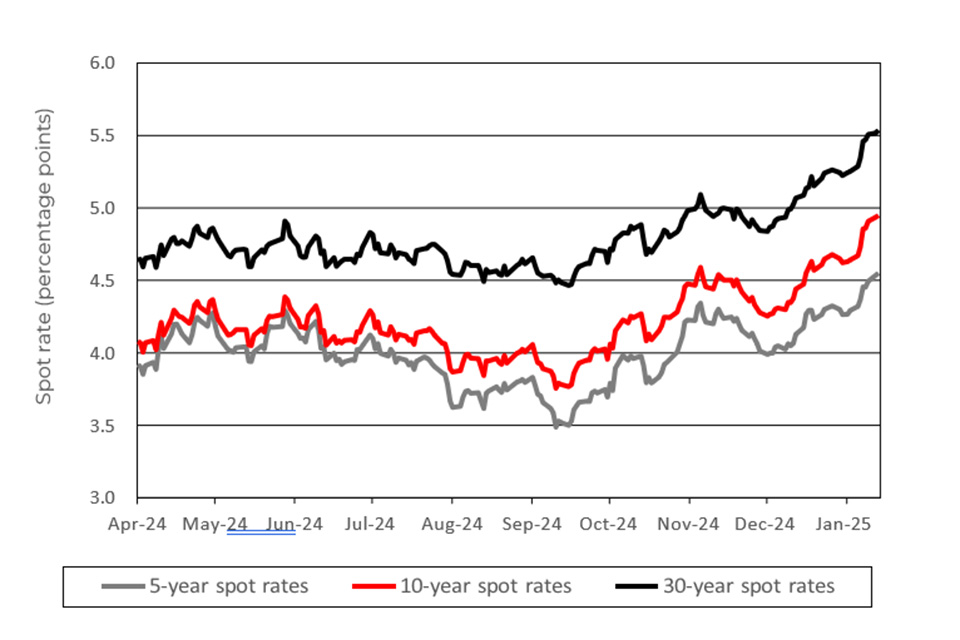

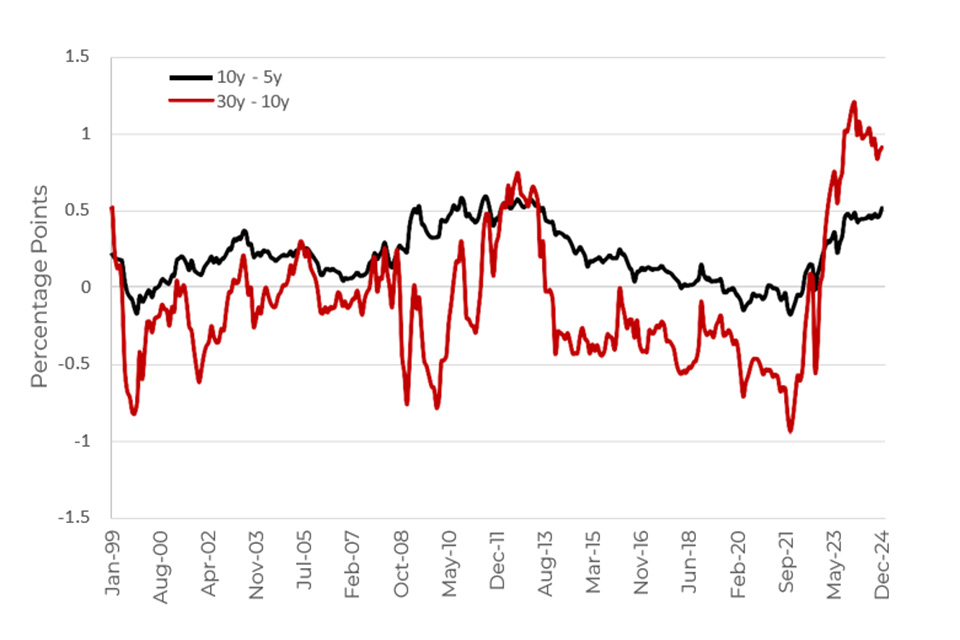

Cost

This section provides an overview of cost considerations. These analyses complement the qualitative demand feedback and help to inform evaluations of the relative cost effectiveness of different types of gilt issuance. Chart B.1 reports the evolution of nominal spot yields for several maturities since the beginning of 2024-25.[footnote 29] It shows that, in the first quarter of the financial year, the 5- and 10-year yields were oscillating around the 4% area and 30-year yield around the 4.5% area before a fall in yields at end of July 2024. After increasing slightly, yields fell in the first half of September, with the 5-year yield reaching a low of around 3.5%. This was followed by an increase of around 100 basis points (bps) across the selected maturities in the period up to February 2025. The chart illustrates large changes in yields throughout the year. It should be noted that, particularly during periods of volatility, outturn yields during the financial year may differ from observations made at the time at which the annual remit is set. Hence, immediately observable cost factors must be weighed carefully against other considerations.

Chart B.1 Nominal spot yield dynamics (to February 2025)(1)

Chart B.1 Nominal spot yield dynamics (to February 2025)

| 1: Daily spot yields for selected maturities from 2 April 2024 to 3 February 2025. |

Source: DMO.

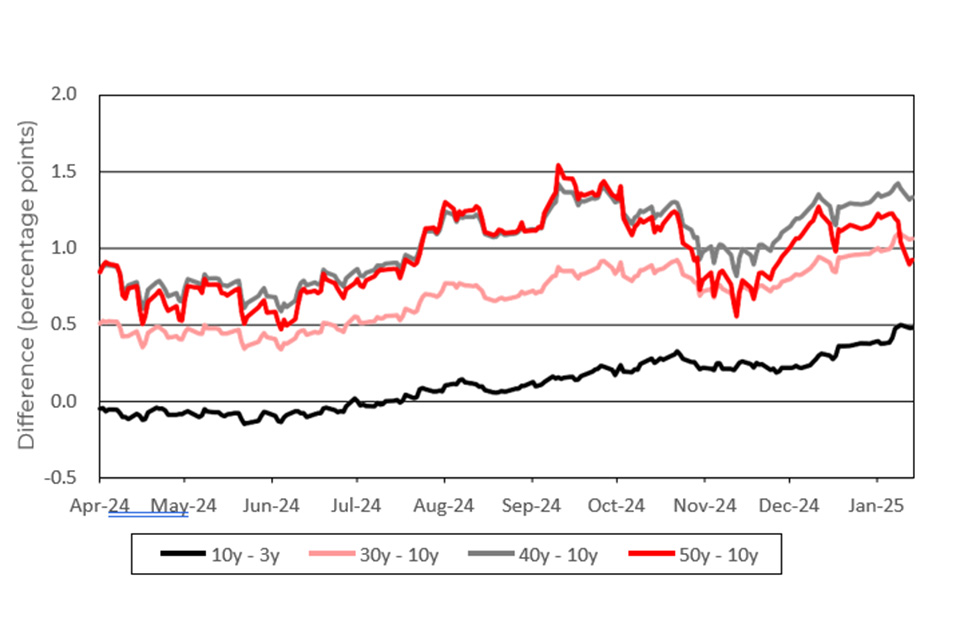

In the period between April and July 2024, the 3-year yield was higher than the 10-year yield. This inversion slowly diminished, with the spread between the 3- and 10-year yields reaching positive territory in July. Following this, there was a gradual steepening of the curve as longer maturity yields increased at a faster rate than shorter maturity yields. This trend reversed for longer term yields during the period between September and November before steepening again from November onwards, as shown in Chart B.2.

Chart B.2 Differences across spot yields of different maturities (to January 2025)(1)

Chart B.2 Differences across spot yields of different maturities (to January 2025)

| 1: The black line shows the difference between 10-year and 3-year spot yields to 3 February 2025. The pink, grey, and red lines show the difference between the 30-, 40-, 50-year spot yields and the 10- year spot yields to 3 February 2025, respectively. |

Source: DMO.

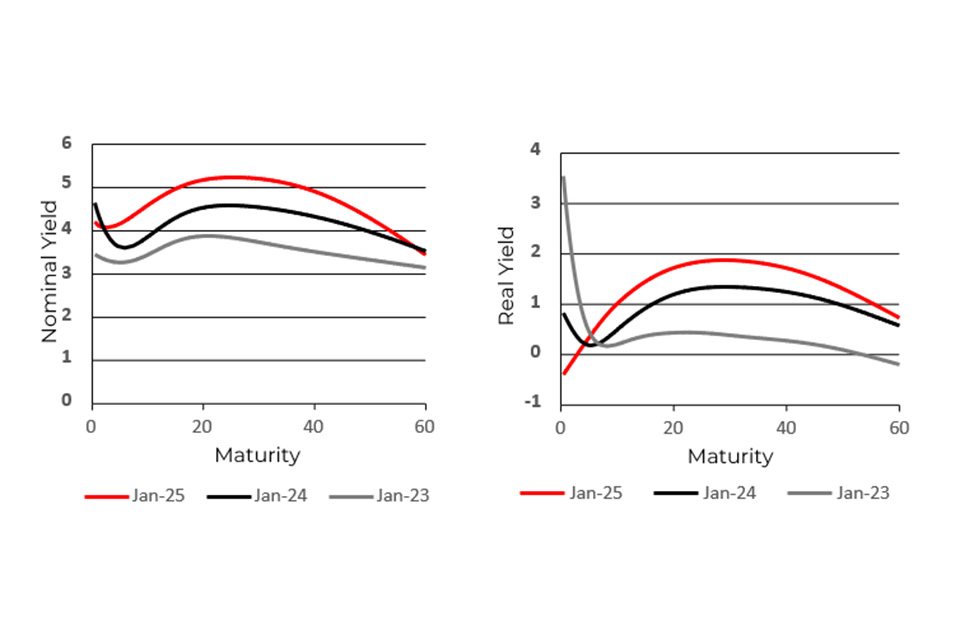

The changes described above, together with current demand conditions, have resulted in an upward shift in the nominal yield curve. This can be seen in Chart B.3, which displays the shapes of both the nominal and real spot yield curves as at 31 January 2023, 2024, and 2025.

Chart B.3 Nominal and real spot yield curves (as at end of January 2023, 2024, and 2025)(1)

Chart B.3 Nominal and real spot yield curves (as at end of January 2023, 2024, and 2025)

| 1: The left-hand (right-hand) side panel shows the shape of nominal (real) spot yield curves as at 31 January 2023, 2024, and 2025. |

Source: DMO.

Taking into account the market pricing of gilts is an important consideration in determining the appropriate composition of maturities to issue. To illustrate, the yield of a long-term, zero-coupon gilt can be decomposed into two components: a ‘risk neutral’ yield and a risk premium (also called a term premium). The former corresponds to the average expected future short-term interest rates over the life of the gilt. The latter is normally thought of as the additional return that risk- averse investors demand as compensation for the possibility of capital loss if a gilt is sold before maturity and, in the case of conventional gilts, the risk of the bond value being eroded by inflation.

The risk premium may also be determined by supply and demand imbalances for a specific instrument, which may be driven by changes in investors’ risk preferences and expectations, and unanticipated macroeconomic shocks.[footnote 30] All else being equal, cost considerations would tend to prompt a government to issue at maturities where the risk premium demanded by investors is lowest relative to other maturities.

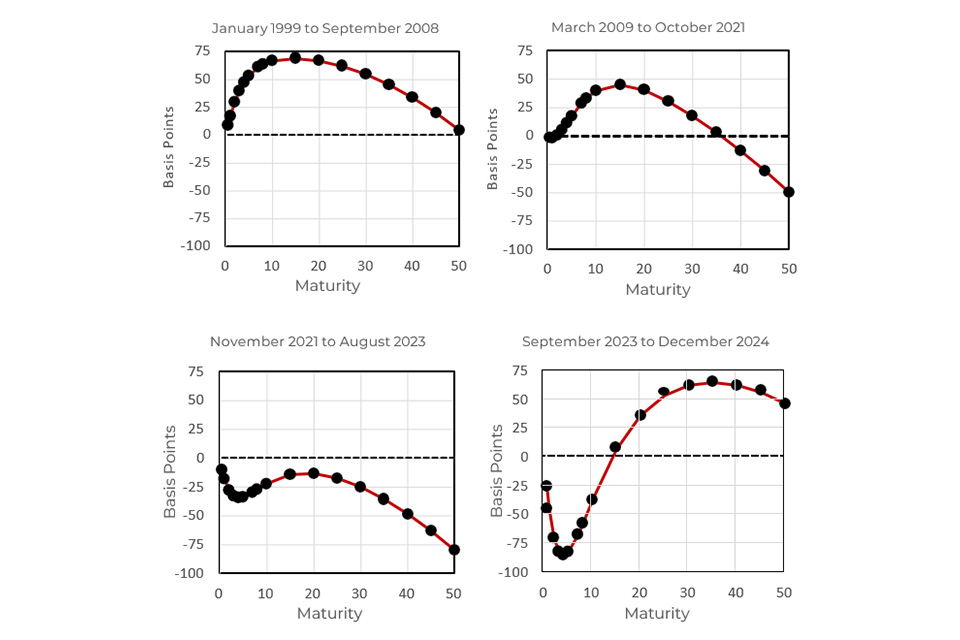

Risk premia cannot be directly observed but must be inferred from bond yields by mathematical modelling techniques. Several models exist: while they may differ as to the levels of risk premium they estimate, especially when market moves are large, they typically agree on the direction of risk premium changes, and on relative term premia across maturities. Risk premium analysis can therefore provide important insights into the nature of changes of investor expectations and demand dynamics.

Chart B.4 displays the term structure of risk premia, with each individual panel showing averages over a selected time period. The top left panel focuses on the period before the global financial crisis, when risk premia were higher than today. Following the global financial crisis, we observe a period with lower and inverted risk premia – i.e. premia in longer maturities is lower than that of shorter maturities. The bottom left panel shows premia estimates during the recent period of increases in Bank Rate, in which there is a further inversion of the curve. Finally, the bottom right panel shows premia estimates during the last year. In this period, shorter-dated gilts have significantly lower risk premia.

Chart B.5 shows the evolution of differences in risk premia between different maturities. It can be observed from the chart that, over the last year, risk premia have been increasing further in longer maturities in comparison to shorter maturities.

Chart B.4 The term structure of risk premia in the UK conventional gilt market over selected sample periods(1)

Chart B.4 The term structure of risk premia in the UK conventional gilt market over selected sample periods

| 1: Averages of time-varying risk premia over selected time periods are based on the AFNS model of Christensen, J. H., Diebold, F. X., & Rudebusch, G. D. (2011). “The affine arbitrage-free class of Nelson– Siegel term structure models”. Journal of Econometrics, 164(1), 4-20. |

Source: DMO.

Chart B.5 Differences of risk premia across different maturities (to January 2025)

Chart B.5 Differences of risk premia across different maturities (to January 2025)

Source: DMO

The government also undertakes an evaluation of the relative cost-effectiveness of index-linked gilts (ILGs), in addition to its analysis of conventional gilts. ILGs differ from conventional gilts as both the principal and coupon payments are indexed to the value of the Retail Prices Index (RPI). One cost consideration for issuing ILGs is whether investors are willing to pay an additional premium for the protection from inflation that these securities provide.

One way to take account of the cost-effectiveness of ILGs against conventional gilts is to evaluate the break-even inflation rate (BEIR). It is typically calculated as the difference between the yield of a nominal gilt and the yield of an ILG of the same maturity. The BEIR can be seen as the average rate of inflation, over the life of a gilt, at which an issuer should be indifferent on cost grounds between issuing either a conventional gilt or an ILG.

The BEIR can be decomposed into an expected inflation component and two additional factors: the additional premium investors are willing to pay for protection against inflation, and the discount they require for holding less liquid bonds. Consequently, one possible way to assess the cost-effectiveness of an ILG relative to a conventional gilt is to compare the actual inflation outturn over the life of the gilt with the market-implied BEIR.

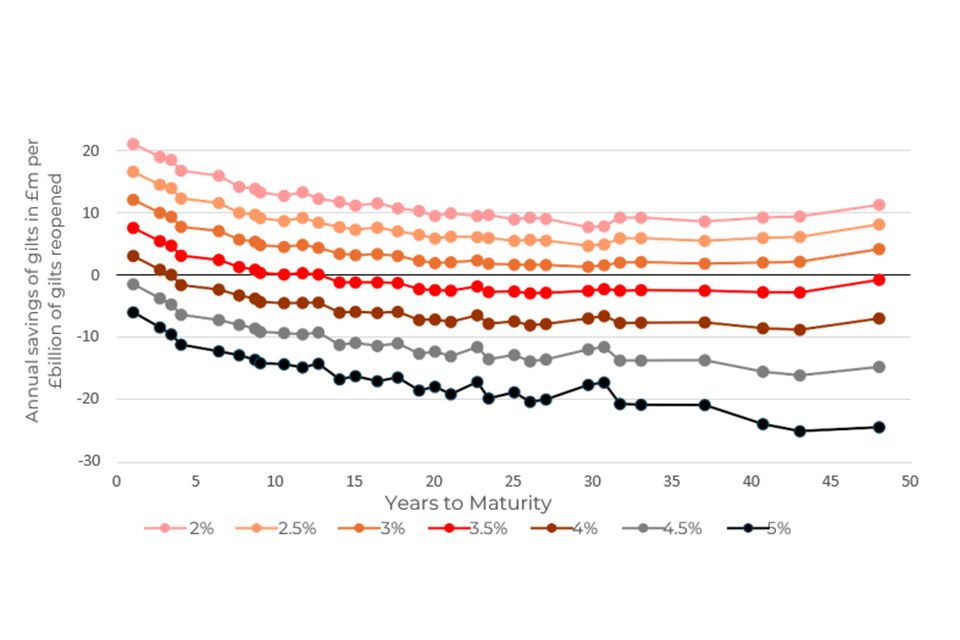

Chart B.6 illustrates potential annualised costs or savings from ILG issuance relative to conventional issuance under different RPI inflation scenarios (expressed in £ million per £ billion of each gilt issued).[footnote 31] Note that these are purely illustrative and not forecast scenarios. The analysis shows that issuing ILGs is cost-effective at all maturities relative to an equivalent conventional gilt in scenarios where RPI does not exceed 3.0% (on average) over the life of the gilt.

For a given level of average inflation, the analysis shows that shorter maturity ILGs are more cost effective than longer maturity ILGs. Assuming that CPI inflation will return to target and that the methodology and data sources of CPIH will be brought into the RPI from 2030, the average inflation rate over the life of the bond is however likely to be higher for shorter maturities than for longer maturities. If CPI inflation were to be consistently at the Bank of England target (2.0%), the effect of RPI reform in 2030 would be that the average inflation rate over the next 30 years would be around 0.2 percentage points below the average inflation rate over the next 10, assuming a wedge between RPI and CPI inflation of 0.9 percentage points until RPI reform in 2030 and 0.4 percentage points thereafter.[footnote 32]

Taking this into account implies that issuing at longer maturities remains at least as attractive as issuing at shorter maturities.

Chart B.6 The cost effectiveness of index-linked gilts relative to conventional gilts under different RPI scenarios (as of 7 Feb 2025)(1)

Chart B.6 The cost effectiveness of index-linked gilts relative to conventional gilts under different RPI scenarios (as of 7 Feb 2025)

| 1: Data markers in each line on the chart represent results from specific index-linked gilts maturing at each point in time illustrated. The jagged path of the lines in Chart B.6 reflects the fact that gilts with higher coupons have a greater sensitivity to the Index Ratio. In such cases, a greater saving or cost occurs in comparison with gilts of the same maturity but with a smaller coupon. As can be seen in the chart, the effect also grows in scenarios with higher average levels of RPI. |

Source: DMO.

Risk

In the context of the long-term focus of the debt management objective, the other key determinant in the government’s decisions on debt issuance by maturity and type of instrument is its assessment of risk. In reaching a decision on the overall structure of the remit, the government considers the risks to which the Exchequer is exposed through its debt issuance decisions, and assesses the relative importance of each risk in accordance with its risk appetite.

The government places a high weight on minimising near-term exposure to refinancing risk. The government also places importance on avoiding, when practicable, large concentrations of redemptions in any one year. To achieve this, the government will issue debt across a range of maturities, smoothing the profile of gilt redemptions to the extent possible.

The government is mindful of the long-term inflation exposure in the public finances and gives due consideration to ensuring inflation risk is prudently managed. The government will manage this exposure through its decisions on the appropriate balance between index-linked and conventional gilts in its debt issuance in the coming years.

Prudent debt management is also served by promoting sustainable market access, which the remit is designed to support. The government places significant importance on encouraging the development of a deep, liquid, and efficient gilt market, and a diverse investor base, in order to maintain continuous access to cost-effective financing in all market conditions.

Promoting these features of the gilt market will also serve to minimise debt costs to the government over the long term, because investors reward an issuer for providing a continuous and ready market, and a globally recognised benchmark product.

Gilt distribution

Auctions will remain the primary method of issuance in 2025-26. The use of syndications will continue in 2025-26. Any type and maturity of gilt can be sold through syndication and the DMO will announce on a quarterly basis its planned syndication programme.

Gilt tenders may be used in 2025-26 to issue any type and maturity of gilt. Further details are set out in the DMO’s 2025-26 financing remit announcement.

The scheduling of gilt operations throughout 2025-26 will, as usual, take into account the timing of gilt redemptions in the financial year.

The government remains committed to the GEMM model to distribute gilts through auctions, syndications, and gilt tenders, and the government recognises that GEMMs play an important role in helping to facilitate liquidity in the secondary market.

Gilt issuance by maturity and type in 2025-26

In determining the split of gilt issuance, the government has taken into account its analysis of the relative cost-effectiveness of the different gilt types and maturities, its risk preferences (including for the portfolio as well as the issuance programme), the market feedback it has received, and operational viability.

Continuing strong demand for short-dated conventional gilts is anticipated in 2025-26, which has been balanced against managing the government’s near-term exposure to refinancing risk. Relative to the 2024-25 programme from Spring Budget 2024, the planned issuance of short-dated conventional gilts in 2025-26 has increased from 35.9% to 37.1%.

In deciding the proportion of medium-dated conventional gilts to issue, the government recognises the important role that they (particularly at the 10-year maturity) play in facilitating the hedging of a wide range of gilt market exposures through the futures market, which helps to underpin liquidity in the sector. Relative to the 2024-25 programme from Spring Budget 2024, a 1.0 percentage point proportional decrease in the issuance of medium-dated conventional gilts is planned in 2025-26 (at 30.0%).

Market feedback suggested declining demand for long-dated conventional gilts, in particular from the domestic pension fund sector. Additionally, in determining the amount of long-dated conventional gilts to issue, the government has taken into account changes in the relative cost effectiveness of long conventional gilts relative to shorter maturities, and the role of long-dated conventional issuance in mitigating its near-term exposure to refinancing risk.

Relative to the 2024-25 programme from Spring Budget 2024, a 5.0% percentage point proportional decrease in the issuance of long- dated conventional gilts is planned in 2025-26 (at 13.4%).

Issuing index-linked gilts has historically brought cost advantages for the government due to strong demand from the domestic pensions sector in particular. Some market participants have suggested that pension fund demand for index-linked gilts has been declining more recently.

Relative to the 2024-25 programme from Spring Budget 2024, the planned issuance of index-linked gilts in 2025-26 is reduced (at 10.3%).

£27.5 billion of issuance (9.2% of total issuance) will be initially unallocated in 2025-26. This is somewhat higher than announced at Spring Budget 2024 for 2024-25 (3.8%), in order to facilitate the DMO scheduling gilt tenders in a more programmatic way and so as to take account of market feedback, which emphasised the importance of maintaining flexibility. The unallocated pot can be used to issue any type or maturity of conventional (excluding green) gilts and index- linked gilts via any issuance method. It is intended to facilitate remit delivery by permitting gilt supply to be tailored more responsively in- year to developments in the gilt market, while remaining consistent with the principles of openness, predictability, and transparency.

Treasury bill issuance in 2025-26

Treasury bills are used for both debt and cash management purposes. In relation to the former, changes to the Treasury bill stock have historically offered an efficient way to accommodate in-year changes to the financing requirement.

The government does not have a target for the planned end-year total Treasury bill stock (i.e. also including Treasury bills issued for cash management purposes). Information on the outstanding stock of Treasury bills will continue to be published monthly in arrears on the DMO’s website.

It is expected that net issuance of Treasury bills will make a £5.0 billion contribution to debt financing in 2025-26.

Annex C: NS&I’s financing remit for 2025-26

This annex sets out information on the activities of NS&I in 2024- 25 and 2025-26. NS&I is both a non-ministerial department and an executive agency of the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Its activities are conducted in accordance with its remit, which is to provide cost- effective finance now, and in the future, for the government. It does this by raising deposits and investments from retail customers, whilst balancing the interests of the taxpayer, its savers, and the wider financial services sector. This will remain the case in 2025-26.

NS&I’s contribution to meeting the government’s financing needs is agreed with HM Treasury each year, and is based on the government’s gross financing requirement, conditions in the retail financial services market, and NS&I’s ability to raise the funding without distorting the market.

As a HM Treasury policy product, proceeds from retail Green Savings Bonds (GSB) are in addition to NS&I’s Net Financing target. As such, they have been reported alongside the financing arithmetic for 2024-25 and 2025-26.

Volume of financing in 2024-25

NS&I’s contribution to financing in 2024-25 is projected to be £10.5 billion, with gross inflows (including reinvestments and gross accrued interest) of approximately £59.6 billion. This is against a 2024-25 target of £9.0 billion (within a range of ± £4.0 billion).

Table C.1 shows changes in NS&I’s product stock during 2024-25.

Table C.1: Changes in NS&I’s product stock in 2024-25 (£ billion)(1)

| 2023-24 | 2024-25(1) | Year-on-year changes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable rate | 177.8 | 190.7 | 13.0 |

| Fixed rate (exc. GSB) | 31.4 | 29.8 | -1.6 |

| Index Linked | 19.5 | 18.7 | -0.8 |

| Total | 228.7 | 239.2 | +10.5 |

| Green Savings Bonds | 1.9 | 1.7(2) | -0.2 |

| 1: Projections for 2024-25. |

| 2: This reflects proceeds from Green Savings Bonds from the period Oct 2021 to Jan 2025, and a projection to end March 2025 |

Source NS&I

Volume of financing in 2025-26

Gross inflows (including reinvestments and gross accrued interest) into NS&I’s products are projected to be around £50.1 billion in 2025-26. After allowing for expected maturities and withdrawals, NS&I will have a 2025-26 Net Financing target of £12.0 billion (within a range of ± £4.0 billion).

Further details of NS&I’s activities in 2024-25 and 2025-26 will be included in its 2024-25 Annual Report and Accounts, which is scheduled to be laid in Parliament in Summer 2025, and which will be published on NS&I’s website.

Annex D: The Exchequer cash management remit for 2025-26

Exchequer cash management objective

The government’s cash management objective is to ensure that sufficient funds are always available to meet any net daily central government cash shortfall and, on any day when there is a net cash surplus, to ensure this is used to best advantage. Cash management operations are intended to work alongside debt management activities so that the government can always rely on sufficient funds being available to finance its activities. HM Treasury and the DMO work together to ensure a suitable framework is in place to achieve this.

HM Treasury’s role is to make arrangements for a forecast of the daily net flows related to revenue and expenditure into or out of the central Exchequer funds (and its objective in so doing is to provide the DMO with timely and accurate forecasts of the expected net cash position over time).

The DMO’s role is to make arrangements for funding and for placing the net cash positions, primarily by carrying out market transactions in light of the forecast (and its objective in so doing is to minimise the costs of cash management, while operating within the risk appetite approved by ministers).

The government’s preferences in relation to the different types of risk-taking inherent in cash management are defined by a set of explicit limits covering four types of risk, which, taken together, represent the government’s overall risk appetite. [footnote 33] The risk appetite defines objectively the bounds of appropriate government cash management activities, in accordance with the government’s policy for cash management; that is, as a cost minimising – rather than profit maximising – activity, and one that plays no role in the determination of interest rates. The DMO may not exceed this boundary but, within it, the DMO will have discretion to take the actions it judges will best achieve the cost minimisation objective.

DMO’s cash management objective

The DMO’s cash management objective is to minimise the cost of offsetting the government’s net cash flows over time, while operating within the government’s risk appetite. In so doing, where possible, the DMO will seek to avoid actions or arrangements that would:

-

undermine the efficient functioning of the sterling money markets

-

conflict with the operational requirements of the Bank of England for monetary policy implementation

Instruments and operations used in Exchequer cash management

The range of instruments and operations that the DMO may use for cash management purposes, including the arrangements for the issuance of Treasury bills, is set out in the DMO’s Exchequer cash management Operational Notice.

Treasury bills may be used for both cash and debt management purposes. In relation to the latter, any positive or negative net contribution to the government’s debt financing plans that is attributable to changes in the stock of Treasury bills is set out in the financing arithmetic (Table 3.A).

For cash management, the DMO uses Treasury bills to help manage fluctuations in the government’s cashflow profile throughout the year and does so by varying the amount raised through Treasury bills, with reference to the forecast net cash position. In order to provide flexibility for the DMO to use Treasury bills across the financial year’s end for cash management, no end-year target stock of Treasury bills is set. Information on the total stock of Treasury bills is published monthly on the DMO’s website.

As a contingency measure, the DMO may issue Treasury bills to the market at the request of the Bank of England and, in agreement with HM Treasury, assist the Bank of England’s operations in the sterling money markets, for the purpose of implementing monetary policy, while meeting the liquidity needs of the banking sector as a whole. In response to such a request, the DMO may add a specified amount to the size(s) of the next Treasury bill tender(s) and deposit the proceeds with the Bank of England, remunerated at the weighted average yield(s) of the respective tenders. The amount being offered to accommodate the Bank of England’s request will be identified in the DMO’s weekly Treasury bill tender announcement. Treasury bills may also be issued bilaterally to the Bank of England, in order to support intervention schemes. Treasury bill issuances made at the request of the Bank of England will be identical in all respects to Treasury bills issued in the normal course of DMO business. The DMO may also raise funds to finance advances to the Bank of England and would, in conjunction with HM Treasury, determine the appropriate instruments through which to raise those funds.

DMO collateral pool

Gilts and/or Treasury bills may be issued to the DMO to help in the efficient execution of its cash management operations. The amounts will be chosen to have a negligible effect on any relevant indices. This will normally be on the third Tuesday of April, July, October, and January. Any such issuances to the DMO will be used as collateral and will not be available for outright sale. The precise details of any such issuances to the DMO will be announced at least two full working days in advance of the creation date. If no issuance is planned to take place in a particular quarter, the DMO will announce that this is the case in advance.

In the event that the DMO requires collateral to manage short- term requirements, it may create additional gilt and Treasury bill collateral at other times. Any such issuances to the DMO will only be used as collateral and will not be available for outright sale by the DMO.

The DMO’s collateral pool may also be used to support HM Treasury’s agreement to provide gilt collateral for the purpose of the Bank of England’s Discount Window Facility. The gilt collateral will be held by the DMO and lent to the Bank of England on an ‘as needed’ basis; gilts created for this purpose will not be sold or issued outright into the market.

Active cash management

The combination of HM Treasury’s cashflow forecasts and the DMO’s market operations characterises an active approach to Exchequer cash management. A performance measurement framework for active cash management – in which discretionary decisions that are informed by forecast cashflows are evaluated against a range of indicators – has been in place since 2007-08. These include qualitative measures as well as measures quantifying returns to active management, after deducting an interest charge representing the government’s cost of funds. Performance against these key indicators is reported in the DMO’s Annual Review.

-

Charter for Budget Responsibility Autumn 2024’, HM Treasury, January 2025. ↩

-

Charter for Budget Responsibility Autumn 2024’, HM Treasury, January 2025. ↩

-

More information about the DMO can be found on the DMO Who We Are webpage ↩

-

‘United Kingdom Debt Management Office Executive Agency Framework Document’, April 2005. ↩

-

In nominal uplifted terms. ↩

-

Each tranche of index-linked gilt (ILG) issuance was compared to a hypothetical conventional gilt of the same maturity raising the same amount of cash as the ILG issued. The cashflows of each hypothetical conventional gilt were calculated by setting its coupon to be equal to the nominal par yield at the relevant maturity observed on a fitted curve of conventional gilt yields at the same time that the ILG tranche was issued. In order to make the different cashflow structures of the conventional and index-linked gilts comparable, it was assumed that the cashflows on each gilt were financed until maturity at the zero-coupon rates that applied at the time of the cash flow. The gain or loss for each tranche of issuance was calculated by taking the difference between the value of all the cashflows of the ILG and its hypothetical conventional equivalent as at the maturity date. These gains or losses were also translated into present value terms by applying the zero-coupon rates from the maturity date of each tranche until January 2025. ↩

-

As is the case for conventional gilts of all maturity buckets, actual index-linked gilt issuance may differ from planned issuance due to transfers from the unallocated pot. ↩

-

‘UK Government Green Financing Framework’, HM Treasury, June 2021. ↩

-

Customers can access the transparent annual allocation reports and biennial impact reports planned for the wider Green Financing Programme. ↩

-

Retail Green Savings Bond proceeds are up to and including February 2025. ↩

-

‘UK Government Green Financing: Allocation Report 2024’, HM Treasury, October 2024. ↩

-

Chancellor of the Exchequer’s speech at Mansion House 2024, November 2024; ‘Government debt issuance pilot using distributed ledger technology’, Tulip Siddiq, November 2024; Announcement of Preliminary Market Engagement Exercise for the Digital Gilt Instrument (DIGIT) Pilot, March 2025 ↩

-

Automatic transfers from the government’s Ways and Means account at the Bank of England offset any negative end-of-day balances in the Debt Management Account. ↩

-

Autumn Budget 2024 HM Treasury, 30 October 2024. ↩

-

It is not currently expected that green gilts will be issued via gilt tenders. ↩

-

Maturities are defined as follows: short (0-7 years), medium (7-15 years), and long (over 15 years). ↩

-

As pre-announced by the DMO on 19 December 2024, on 14 March 2025 the DMO published the gilt auction calendar for the weeks commencing 31 March, 7 April and 14 April 2025, in order to give the market advance notice of these operations. ↩

-

Official Operations in the Gilt Market An Operational Notice ↩

-

Terms and Conditions of Standing Repo Facility: 6 February 2025 ↩

-

Official holdings of gilts comprise holdings by the Debt Management Office (DMO) of gilts created for use as collateral in the conduct of its Exchequer cash management operations (such gilts are not available for outright sale to the market). This also includes any DMO purchases of near-maturity gilts. ↩

-

Maturities here are defined as follows: short (0-7 years), medium (7-15 years), and long (over 15 years). The maturity ranges defined here represent the residual maturities of the relevant instrument categories. ↩

-

Calculated on a nominal weighted basis, excluding inflation uplift, including Treasury bills. To adjust the UK’s weighted average maturity of government debt outstanding for the impact of the asset purchase facility (APF), gilts held in the APF are treated as having a maturity of zero. By financing the purchase of fixed rated government bonds using floating overnight rate central bank liabilities, quantitative easing shortens the effective maturity of government debt outstanding. This effect is present across all countries where central banks have engaged in quantitative easing, including all G7 countries, but is only shown in the chart for the UK. ↩

-

2024 outturn gross financing requirements may differ from these projections, which were published in October 2024. ↩

-

Source: Bloomberg ↩

-

The spot yield for any maturity is defined here as the yield on a theoretical zero-coupon gilt which gives a single payment at that maturity. The spot yield reflects the current yield at a particular point in time. ↩

-

More generally, the risk premium can be decomposed into several components, including: (i) a premium which compensates investors for duration risk that increases for longer maturity investments; (ii) a credit and default risk premium; (iii) a liquidity discount or premium owing to the different levels of liquidity in some bonds or maturities, which enhances or restricts investors’ ability to hedge; and (iv) an inflation risk premium to compensate investors in nominal bonds for uncertainty owing to inflation. ↩

-

Each scenario rate represents the average rate of inflation over the life of the gilt. ↩

-

The four types of risk are defined as: liquidity, interest rate, foreign exchange, and credit risk. ↩