Using appeal judgement transcripts to assess changes in the presence of digital evidence in police investigations

Published 19 May 2022

Applies to England and Wales

Victoria Richardson, Pamela Hanway, Roger Baxter, Jack McMillan

We are very grateful to the following individuals who helped the authors review the appeal summaries:

Lauren Lever, Madeleine Thomas, Abbie Cameron, Anjana Kaur Laugani, Scarlett Furlong, James Haslam, Laura Dewar, Shameem Hussain, Daniel Farrugia, Lilly Stribling, Rory Negus, Tamsin Sharp and Ruby Forshaw.

We would also like to thank our three independent peer reviewers for their comments.

Executive summary

Introduction

Digital forensics is the process of examining digital evidence, which involves the extraction of information from diverse digital systems and data storage media, rendering information into a usable form, then processing and interpreting the information to obtain intelligence for investigations, or evidence for court proceedings. The rapid and sustained growth in using digital devices has resulted in many crimes now being reported where digital evidence is essential to the investigation.

However, there are no established measures of the growth in digital evidence in criminal investigations. Some research has examined the presence of digital evidence in one-off, crime-type-specific studies. But very few studies have sought to examine the change in the presence of digital evidence over time, particularly since the advent of the smartphone. This study seeks to help address this gap.

The current study seeks to estimate national level changes in the extent to which police investigations use digital evidence, over time, through the analysis of criminal appeal judgements.

Methodology

Since digital forensic evidence data are not collected consistently by all police forces nor are they held centrally at the national level, we used appeal judgements as the source of data to act as a proxy to assess changes within police investigations. The Court of Appeal full hearing judgements are transcribed and include a summary of the relevant facts, including the evidence on which the judgements are based. By analysing these summaries, we demonstrated the changes in using digital evidence at a national level.

We chose 2010 and 2018 to best reflect the growth in using smartphone technology. The focus was primarily on assessing the presence of digital evidence in more traditionally ‘offline’ crimes (e.g. theft or public order offences) rather than ‘cyber-dependent’ crimes (e.g. technology-facilitated abuse or offences such as hacking or virus spreading attacks).

We reviewed and systematically assessed all appeal judgement summaries[footnote 1] in 2010 and 2018 for digital evidence. There was no selection of cases nor sampling. Digital evidence related to mobile phone cell-site analysis (where call data records are analysed to identify the potential location of the communication device), internet and personal computing, calls and communications, mobile device data and network intelligence were in scope. Digital material captured by the police or police staff (e.g. body-worn video, data collected at the scene by police practitioners) or independently of victims, witnesses, suspects (e.g. CCTV) was considered out of scope.

We also collated information on the offence type, key dates, primary and secondary sources of digital evidence (mobile phone calls, cell-site analysis, texts, social media etc.), and the type of hardware the information was extracted from. We made a qualitative assessment of the evidential weight of the digital material based on the summaries in the judgements.

Across 2010 and 2018, the total number of appeal cases fell markedly. However, the split of offence types across both years was broadly consistent, with appeals for drugs, violence and sexual offences being the most common offence categories in both years. Between them, the three offence types accounted for just under six in ten appeals in the dataset in both 2010 and 2018 (58% and 59% respectively).

Main findings

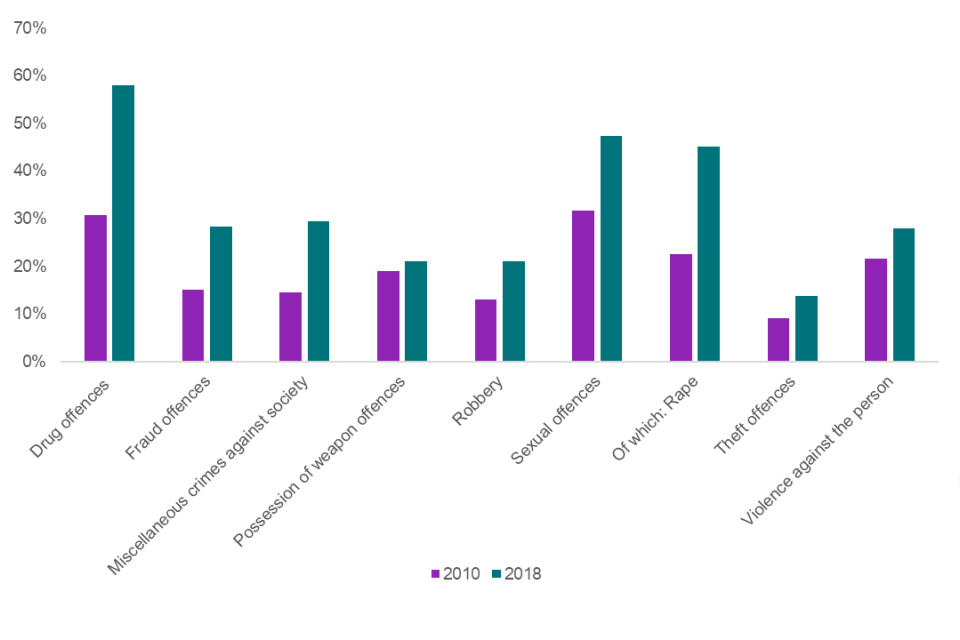

The analysis found that there was a statistically significant increase in the proportion of appeal cases that contained references to digital evidence, up from 21% in 2010 to 34% in 2018. The increasing presence of digital evidence builds on earlier findings of a marked growth in the presence of mobile phone evidence in appeal cases during the second half of the 2000s (McMillan et al., 2013).

We found an increase in the proportion of Court of Appeal judgement summaries referencing digital evidence across all high-level offence types – drugs, sexual offences, violence against the person, fraud, robbery, theft and miscellaneous crimes against society[footnote 2]. There were statistically significant differences for sexual, drugs, miscellaneous crimes against society and violence against the person offences.

Appeals involving drug offences had the highest increase in the proportion of cases with digital evidence. In 2018, 58% of appeal cases for drugs offences had digital evidence, up from 31% in the 2010 summaries.

For all sexual offences, almost half of appeal judgement summaries (47%) had references to digital evidence in 2018, up from 32% in 2010. And looking specifically at rape cases, the proportion of appeal cases referencing digital evidence almost doubled between 2010 and 2018, from 23% to 45%.

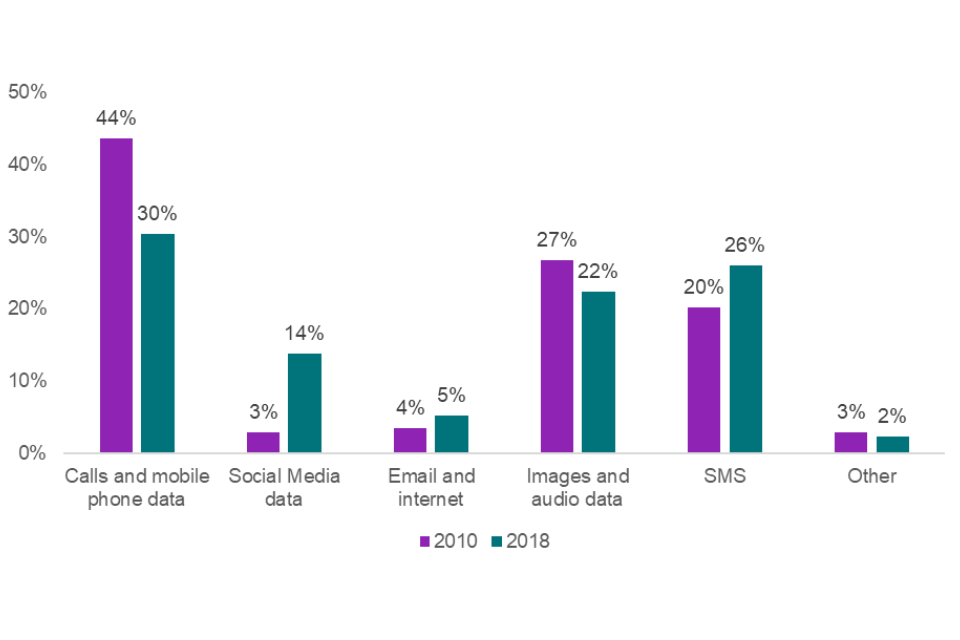

We analysed the sources of digital evidence for those appeal cases which indicated its presence. For all offences combined, there was a decline in references to mobile phone calls and call data. These accounted for 44% of digital evidence in 2010, but the proportion had fallen to 30% in 2018.

In contrast, there was a marked increase in digital evidence sourced from social media platforms, e.g. Facebook and WhatsApp, albeit from a low base (up from 3% to 14%). Digital evidence sourced from text messaging also increased – from one-fifth (20%) in 2010 to just over one-quarter (26%) in 2018 of all digital evidence.

We found variations in the type of digital evidence across different offence types. Rape offences saw an increased proportion in cases referencing images and audio, and social media. For drug offences, the proportion of appeal cases referencing call records decreased in 2018, but there was an increase in the proportion of references to SMS data.

The analysis also found an increase in the dominance of mobile devices as the main hardware from which digital evidence is extracted. There was an increase in the proportion of mobile/smartphone references in 2018 cases (89%) compared with 2010 (75%).

Analysis of the time taken for cases to progress from offence to appeal indicated it typically takes two years (although, the elapsed time was far greater in some cases). In this sense, the digital profile evidenced from the appeal judgement summaries in this study reflects digital evidence in offences typically committed in 2008 and 2016.

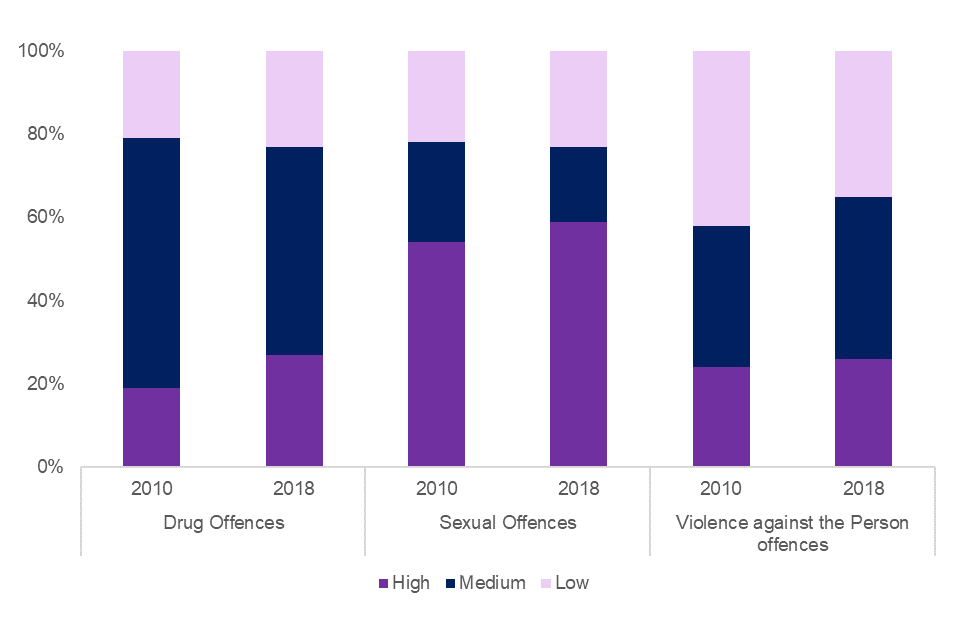

Where we found digital evidence present in the appeal judgement summaries, researchers qualitatively assessed the ‘weight’ of digital evidence – how relevant it appeared to be at the court and appeal stage – as being high, medium or low for each case summary. Where digital evidence was present, reviewers assessed the evidence as having more weight for sexual offences than for drug offence cases or violence offences. For sexual offence cases, the proportion of cases assessed as having ‘highly’ weighted digital evidence was over half in both years. For drug and violence offences, the equivalent figures ranged between one in five and less than one in three.

Limitations

Appeal judgement transcripts are not designed to enable analysts to examine, consistently, the evidence presented in the original case, nor to assess the relevance of digital evidence in the case. This means that the level of evidential detail reported in the transcripts was rarely consistent between cases because it depended on why the appeal was being heard.

Using appeal judgements means it is likely that, for the cases reviewed, the findings will tend to underestimate the extent of digital evidence seized and analysed within the original police investigation. This is because some transcripts with no reference to the collection and analysis of digital evidence – and therefore classified as non-digital – will still have involved investigations with a digital component. The judgement summary is unlikely to reflect investigative activity with a digital element that was routine or failed to generate material of relevance.

So, our assessment is that the proportion of ‘digital evidence cases’ is best perceived as an indication of a minimum level of the presence of digital evidence in these cases. In this sense, they show the visible part of the digital ‘iceberg’ in criminal cases heard at appeal.

The analysis is based on the small subset of offences that make it to appeal. The issue here is less the relatively modest number of cases reviewed, but more the extent to which appeal cases reflect the upstream criminal justice system (CJS). The figures for the overall proportion of digital cases within appeals are likely to be a poor proxy measure for the percentage of digital cases within the totality of police recorded crime. This is because the crime-type profile of Appeal Court cases is markedly different from offences recorded by the police. The former has proportionately more violence, drugs and sex offences; the latter is dominated by theft offences.

However, for a handful of selected individual crime types – mainly those more serious offences where levels of investigative effort are higher, such as sexual offences and drugs trafficking – it is likely the appeal case findings are somewhat more in step with the ‘digital profile’ of police investigations.

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Digital forensics relates to the science of recovering digital evidence from mobile or electronic devices to support the investigation of crimes using forensically sound and accepted methods (Barmpatsalou et al., 2013). It is more widely viewed as being a relatively new science compared with more traditional forensic approaches, such as fingerprint analysis (Page et al., 2019). In the 2020 Codes of Practice and Conduct, the UK Forensic Science Regulator (FSR) describes digital forensics as the process of examining digital evidence, which involves the extraction of information from diverse digital systems and data storage media, rendering information into a usable form, then processing and interpreting the information to obtain intelligence for investigations, or evidence for court proceedings (Forensic Science Regulator, 2020). Digital evidence is, therefore, important for police investigations as it can generate information that can support or challenge narratives about an incident or a crime (Dodge, 2019).

The rapid and sustained growth in using digital devices is well established. In the past decade, Ofcom (Office of Communications) reported that adults’ use of various forms of technology has risen; for example, the use of smartphones by adults has increased from 54% in 2014 to 87% in 2021 (Ofcom, 2021). Digital evidence can now be extracted from an increasing number of possible sources, including: end user devices (phones, computers, hard drives), network devices (routers), the internet (websites, social media), remote storage devices (cloud storage), communications (texts, emails, contact lists, call records), security devices (CCTV, body-worn video footage) and ‘Internet of Things’ (e.g. connected home appliances and smart home security systems). For a review of the use of these sources, see Douglas et al., 2019 and Rappert et al., 2020. These multiple sources of digital evidence, the increased use of digital technologies, and the ‘always connected’ consumer have resulted in many crimes now being reported where digital evidence is essential to the investigation (NPCC, 2020).

But while it is widely recognised that the use of digital evidence in police investigations has grown, there are limited data on the underlying rate of the growth within criminal cases. A request made by the authors to police forces (in England and Wales) for data on the presence of digital forensics, or other proxy measures of digital demands within criminal investigations, yielded little comparable or usable data. Although all forces approached could provide data on certain aspects of the digital evidence seized and analysed, data on the volume were not captured consistently. This is not unexpected. As part of a freedom of information (FOI) request, a Big Brother Watch report on police access to digital evidence identified a lack of data on the number of devices seized by UK police forces (Big Brother Watch, 2017). Thirty-two police forces could not provide the information because it was not held centrally, or it was difficult to retrieve (ibid). As part of the Digital Forensic Science Strategy, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) investigated issues and challenges of increased digital demand on policing and undertook a bespoke survey to capture baseline data from police forces on their digital demands, capabilities and resources to “define the state of digital forensics in England and Wales for the first time” (NPCC, 2020).

An initial rapid review of the published academic literature on digital forensics identified useful research on digital evidence and the challenges faced by the police (e.g. Casey, 2019; NPCC, 2020; Lillis et al. (2016); Rappert et al. 2020), issues for the criminal justice system (CJS) more widely (e.g. Karie & Venter, 2015; Kovacs-Wilson, 2021), and solutions to the challenges of digital forensics (e.g. NPCC, 2020; Quick & Choo, 2014). It is beyond the scope of this study to include a review of these areas, instead the focus will be on digital evidence in police investigations and at court, and how this has changed over time.

We identified very few studies that quantified the change over time. Berman et al. (2015) investigated the increased use of global positioning systems (GPS) in court cases between 1993 and 2013. Graves et al. (2020) considered changes over time in using social media as digital forensic evidence in US courts. McMillan et al. (2013) examined the increased use of mobile phone evidence from 2006 to 2011 in appeal cases in the UK. These studies, the police data and other academic literature have provided information about the presence and use of digital evidence. However, we could not find any previous research that quantified national level changes in the presence of digital evidence in police investigations over time for a broader range of digital devices. The current study seeks to address this gap.

1.2 The current study

The current study aims to assess the presence and nature of digital evidence in criminal appeal cases in England and Wales and how this has changed over time. The study draws on a similar methodology to that used by McMillan et al. (2013), which assessed the presence of mobile phone evidence in criminal cases through a systematic examination of appeal case summary judgement transcripts. The scope of the current research includes all types of digital evidence, except for CCTV and body-worn video (BWV) evidence. CCTV and BWVs were excluded because the digital evidence held on these was likely to be more readily available for examination by the police, compared with evidence from digital devices recovered from victims, witnesses and suspects. It is recognised that challenges remain when examining data from these devices (see Garfinkle, 2013).

We reviewed the judgements on criminal cases heard in the Court of Appeal in the calendar years of 2010 and 2018, for the presence of digital evidence. Offence-based analysis grouped cases by the highest Home Office grouping level, i.e. the ‘class’ of offence.[footnote 3] Rape cases were identified separately within sexual offences.

The focus was primarily on assessing the presence of digital evidence in more traditionally ‘offline’ crimes (e.g. theft or public order offences). So called ‘cyber-dependent’ crimes, which rely on computers and networks (e.g. technology-facilitated abuse or offences such as hacking or virus spreading attacks), were not the primary focus for the study. However, we did include these types of crimes for analysis at the class grouping level if there was an appeal judgement within the chosen time frame. The study also reviewed the types of digital forensic evidence and devices involved, if we could discern these characteristics from information contained in the appeal judgement summaries. In summary, the aims of the research were to:

- Assess changes in the presence of digital evidence in appeal judgements, for 2010 and 2018, to help infer changes in digital demand in police investigations.

- Improve understanding of how digital evidence varies by offence type and examine how patterns have changed over time.

- Increase understanding of the importance of digital evidence at the appeal stage and, through this indirect means, at the police investigation stage, and assess changes over time.

2. The current evidence base

2.1 Changes in the use of digital devices

Over a relatively short period of time, there has been a rapid increase in using computers, and more recently mobile devices, to access the internet and use social media. In 2000, 25% of UK households had access to the internet, in 2010 it was 73% and in 2020, 96% (ONS, 2020a). Internet use for different activities has also increased over time. For example, using the internet for sending and receiving emails increased from 60% of internet users in 2010 to 85% of users in 2020, and for accessing social media there has been an increase from 45% in 2011[footnote 4] to 70% in 2020 (ibid).

The 2020 ONS Internet Users Survey estimated that 49 million UK adults (92%) had used the internet in the previous three months, with almost all (99%) of adults aged 16 to 44 years being recent internet users (ONS, 2021). The Ofcom communications report found that adult internet users estimated they spent an average of 25 hours online per week, a figure which has remained unchanged since 2017 (Ofcom, 2018). However, the report also found that how people access the internet is changing; 93% of people now use a device other than a computer to go online, compared with just 6% using non-computer devices for online access in 2014 (Ofcom, 2018). Ofcom’s Adults’ Media Use and Attitudes report (Ofcom, 2021) showed that in 2020, 85% of adults used smartphones, with each smartphone user processing around 1.9GB of data per month. A growing proportion of adults in the UK only use a mobile for internet access; this increased from 3% of adults in 2014 to 11% in 2020 (ibid).

2.2 Digital evidence – police investigations

Information gathered from social media and other digital sources are a means for gathering evidence in police investigations and can be valuable to investigators, for example, when creating a timeline of events or to show intent or conspiracy to commit crimes (Powell & Haynes, 2019). Thus, an increased use of internet and mobile technology will increase the amount of digitally stored data that may be relevant for police investigations. Examinations of computer use and digital devices can be beneficial for evidence gathering, for example, in the investigation of cyber-dependent crimes, which are committed with computers/networks (e.g. bank fraud), or cyber-enabled crimes where evidence relating to the crime is recorded digitally (e.g. child exploitation; Garfinkel, 2010). In addition, some argue that more traditionally ‘offline’ offences now have digital evidence elements. For example, for burglary or robbery offences, police investigations can make use of CCTV footage, dashcam evidence, mobile phone cell-site analysis, text messages, call records from mobile phones and fitness tracker devices (NPCC, 2020). Digital examinations are also an important tool for intelligence-gathering purposes, including the examination of mobile technologies during terrorism investigations (Cahyani et al., 2017; Griffiths et al., 2017) and the online presence of gang members, which can be useful for law enforcement purposes (Pyrooz et al., 2015). In short, every text, search, phone call, email, and picture or video uploaded or shared, is stored and, in many cases, can help establish the sequence in which events occurred, the patterns of behaviours and alibis of suspects (Kovacs-Wilson, 2019). They may also be used to verify, clarify or challenge a victim’s account of an event or its precursors.

As previously noted, research into the presence of digital evidence within police investigations is limited. And while some estimates have appeared in the public domain (such as evidence presented to the House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee in 2020 estimated that 90% of crime now had a digital element), the precise evidential base for this figure was not cited.[footnote 5]

Studies which have assessed the presence of digital evidence within criminal cases have tended to analyse data from cases recorded within a short space of time (e.g. a single year) or in a narrow geographical area. For instance, Gogolin (2010) interviewed digital investigators in 45 of the 83 sheriff’s departments in Michigan in 2009. It was estimated that 50% or more of their cases had a digital component (ibid). Other studies have explored the presence of digital evidence within individual crime types. These studies have tended to focus on more serious offences. A recent UK study (Rumney & McPhee, 2020) examined the evidential value of digital data for rape offences (female complainants over the age of 14 years) from two policing areas in England and Wales. Over a two-year period, data from 441 cases were collected and documents searched for key words, e.g. ‘email’, ‘text’ and devices such as ‘phone’ and ‘laptop’. Of the 441 cases, 61 (14%) were identified as containing requests for the collection of digital evidence (ibid). Murphy et al. (2020) also reviewed all allegations of rape (446) reported to the Metropolitan Police Service (MPS) during April 2016. Coding of the cases included whether technological evidence was gathered as part of the investigation. The researchers found technological evidence was referred to in the police case file in 27% of cases (Murphy et al., 2021). A Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) Inspectorate review of digital forensic evidence in rape cases found that 71% of CPS lawyers and 78% of CPS managers believed that electronic data requests had increased since January 2018, and that 73% of police finalised cases involved devices containing potentially relevant electronic data (HMCPSI, 2019).

Other studies have offered a more qualitative view of the growth in offending with a digital component. The increased use of digital devices – smart phones in particular – has been noted in domestic abuse offences (Freed et al., 2018; Women’s Aid, 2017). A qualitative study with Australian survivors of domestic and family violence highlighted the ways digital media and devices can serve to escalate and amplify abuse, enabling potential harassment, identity theft, distribution of sexual images and abusive messaging; these offences could be committed via one or more technologies or media, such as text, calls, audio, photos, GPS, tracking, social media, email, Skype (or equivalent), and CCTV (Douglas et al., 2019).

As part of the scoping work for this study, we undertook a small-scale exercise to dip sample offences in one UK police force. We randomly selected the cases within each offence type. Analysis of the data provided an outline of the types and size of digital evidence that was associated with five offences: burglary, domestic abuse, drugs, rape and serious sexual assault (RASSO) and indecent image offences. In total, we reviewed 70 case files. We found two-thirds of the RASSO cases had digital evidence associated with them and, on average, five devices or pieces of information were linked to each case. Three-quarters of the domestic abuse cases had digital evidence associated with them, with evidence typically extracted from mobile phones. Indecent image offences, as expected, contained the most digital evidence, with around 9,000 images per case. Drug offences were typically associated with evidence from mobile phones; these offences had approximately six downloaded pieces of information per case. Property crimes had very little digital evidence associated with them. A second police force undertook dip sampling of 41 cases with mobile phones and found that RASSO and drugs offences had the highest use of memory byte sizes, and largest numbers of files and folders, per case.

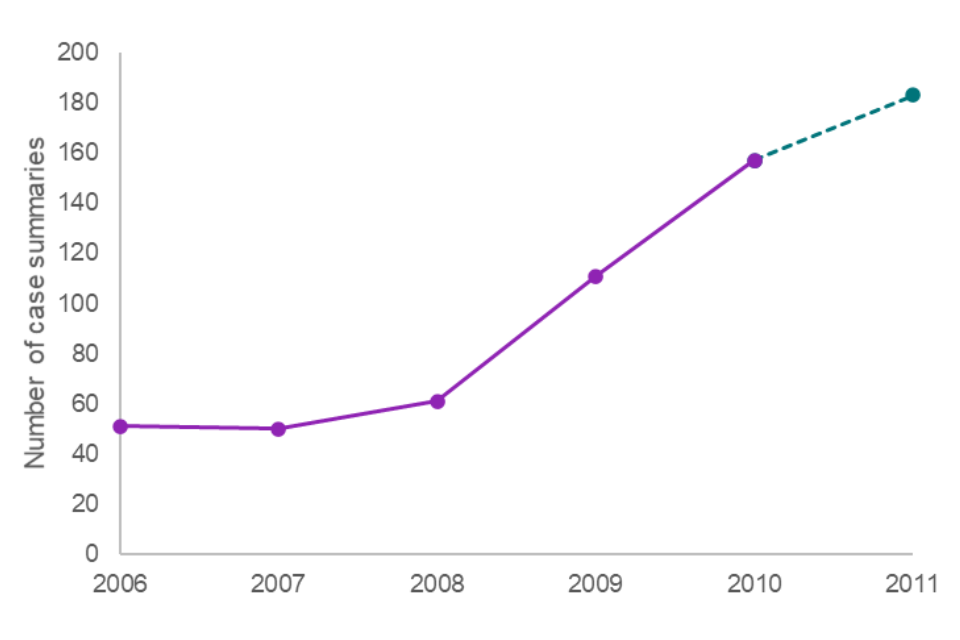

2.3 Digital evidence – court case analysis

Several studies have turned to data from cases which reach court to identify the presence of digital evidence. While these studies are looking at the end point of the criminal justice process, they provide an equally important insight into the nature of evidential material. Research by McMillan and colleagues (2013) is one of a handful of studies which sought to measure the change in the presence of one type of digital evidence – mobile phone evidence – within criminal appeal cases over time. They used keywords to search for the presence of mobile phone digital evidence in appeal case judgements reported in three legal databases (LexisNexis, Westlaw and the British and Irish Legal Information Institute (BAILII)). The researchers found the use of mobile phones in criminal appeal cases increased from around 50 cases in 2006 and 2007 to over 150 cases in 2010, with the number projected to be over 180 in 2011 (see Figure 1). The researchers also examined the type of evidence associated with offence types. They found drug offences were often associated with call records and contact lists, while sexual offences were associated with images and videos. The most common types of evidence reported were call records, followed by SMS messages and images (McMillan et al., 2013).

Figure 1. Number of appeal judgements that contained digital evidence from mobile phones for 2006 to 2011 (projected)

Notes:

- Data for 2006 to 2010 were for the full years, for 2011 data were collected until July so the authors provided a projected figure based on the partial year figure. Data taken from McMillan et al. (2013).

Three further studies – Berman et al. (2013), Graves et al. (2020) and Stevens et al. (2021) – have also examined changes using information taken from court cases. In the first study, the number of criminal and civil cases which mentioned GPS and geographical location evidence between 1993 and 2013 in the UK and Europe were examined (Berman et al., 2013). GPS history evidence has been introduced as evidence in criminal and civil cases since 1993 but the researchers found that the use of GPS evidence increased rapidly from 2003. In the first decade (1993 to 2002), there were only 12 cases identified with GPS evidence, but in the second decade (2003 to 2013), there were 71 cases, with 75% of the court cases with GPS evidence being recorded from 2007 onwards (ibid).

The second study, in California (USA), showed that as social media use – such as social networking sites including Facebook – has increased in recent years, so the use of digital evidence obtained from social media websites has increased in court cases (Graves et al., 2020). This study examined the use of social media evidence in Federal (Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals) and State (Californian) appellate cases between 2000 and 2017. The researchers used keywords to search for court cases with social media evidence in two legal databases (LexisNexis and Fastcase). The first State Court cases where social media evidence was present emerged in 2007 and there was an increase from 11 cases in 2008 to 160 cases in 2016 (ibid).

In the third study, Stevens et al. (2021) did not look at change over time but estimated the proportion of domestic abuse cases which had a digital element. The researchers looked at the frequency with which Computer Misuse Act (1990) offences were flagged in court cases reported in three legal databases (Westlaw, Lexis Nexis and BAILII). They then looked at how many of these cases involved ‘computer misuse’ and ‘intimate partner violence’. Of more interest to this study, the researchers then searched the same legal databases for domestic abuse cases within a six-month period. They retrieved 95 cases from the databases, which they then reviewed for references to tech-abuse including the use of digital technology, digital media and any form of internet connected device, such as cameras, washing machines and doorbells. They found that 21% (20 cases out of 95) of the domestic abuse cases they reviewed had a digital element (Stevens et al., 2021).

2.4 The impact of digital evidence on case outcomes

There is limited research on assessing the impact of digital evidence on investigative outcomes or case building. During their investigation of rape cases within two UK police forces, Rumney and McPhee (2020) found that of 61 cases containing requests for the seizure of digital devices, 36% included evidence that assisted the police/prosecution and 31% contained evidence that may have assisted the defence. In addition, this research found that 21% of the 61 cases resulted in the suspect being charged; in 16% of the cases, the suspect was convicted of a sexual offence; and there was a conviction of rape in 10% of cases (Rumney & McPhee, 2020). Reporting lower percentages, which also diverged from Rumney and McPhee’s findings, Murphy et al. (2021) completed a case-file analysis of 446 allegations of rape and found that of the 27% of rape cases in the MPS with technological evidence, 7% of the evidence supported the victim’s case and 12% supported the suspect’s case, but for 47% it supported neither case (Murphy et al., 2021).

Daly (2021) undertook an observational study of two English sexual offences trials in 2019 to explore how digital evidence is used in practice by observing how the digital evidence was ‘animated’ during the court proceedings. While for both cases the prosecution argued the seemingly unambiguous digital evidence proved guilt, taken out of context, the digital communication evidence could be made to fit an opposing narrative, drawing on rape myths and gendered narratives to undermine the prosecution’s case (ibid).

Taking a different approach to understanding how digital evidence can impact case outcomes, Jackson and Gwinnett (2021) undertook a case-file analysis of online child sexual exploitation cases at the police investigation stage. They looked at 217 cases received by one police force between July 2016 and December 2019 where digital forensics were involved. They collected data from the case files to understand the contribution digital forensic evidence made to each of the seven ‘impact points’ they identified within the police investigation. Impact points included: establishing whether a crime had been committed; safeguarding of victims and suspects; and admission of guilt at an earlier stage. The authors found that the percentage of opportunities where digital forensic evidence contributed exclusively to the impact points were particularly profound for informing interview strategies (64%) and to establish that a crime had been committed (61%). They also found digital forensic evidence contributed generally (i.e. it was not exclusively as a result of the digital evidence) to the attainment of all seven impact points. The contribution across the seven impact points ranged from 22% to 84% and this was particularly the case when digital examiners went to the crime scene as part of the triage team (range was 49% to 97%).

At the end of the CJS process, the appeal stage, studies assessed the relevance of the digital evidence in the cases identified. Berman et al. (2016) found that while not the main piece of evidence, GPS evidence was increasingly being admitted in court between 1993 and 2013. The researchers assessed three-quarters (63%, n=52) of the GPS evidence to be medium or high in terms of supporting the main piece of evidence. McMillan et al. (2013) found the relevance of mobile phone evidence from all cases with digital evidence was low in 64% of the appeal cases examined. In terms of support for the judgement, evidence was supportive of the case in one-third of cases and of high relevance to gaining a conviction in 2% of the cases. Digital forensic examinations can, therefore, impact the outcome of criminal investigations (Wilson-Kovacs, 2019). The Digital Forensic Science Strategy review highlighted that although experts in the field reported anecdotally the value that digital forensic examinations added to support investigations and prosecutions, there was a lack of evidence on the topic (NPCC, 2020).

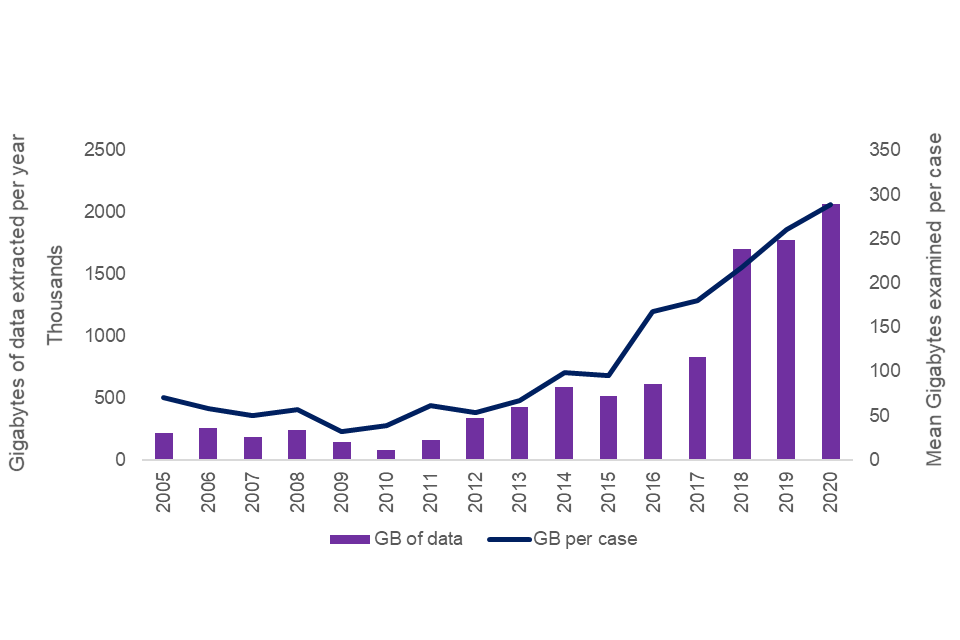

2.5 The wider impact of increased digital demands on police investigations

This final section covers the wider question of the impact of an increase in digital evidence demands on the police. Here the evidence is less clearly distinguishable between cyber-dependent crimes and the presence of digital evidence in crimes more broadly. We approached forensic leads in English and Welsh forces to identify data which might provide some clear evidence of the changing demands from digital evidence. The exercise yielded some data but at differing levels of detail. However, one police force provided information on the size of the imaged data (i.e., the exact copy of the device’s data) taken from devices submitted to the force Digital Forensic Unit (DFU). As Figure 2 shows, the size of imaged data, in terms of gigabytes (GB) per case, has grown steadily from 2009 to 2020; there was a steep rise from 2015 to 2016 with further rises year-on-year to 2020. The data are only for devices examined by DFU and do not include data downloads undertaken by other departments.

Figure 2. Total GB of imaged data taken from devices and the mean number of GB per case examined by DFU in one police force, 2005-2020

Notes:

- In 2016/17 there was an increase in capacity at DFU and more devices could be examined (cases examined 2005-2017 M = 4,364 and for 2018-2020 M = 7,260). This partly explains the large increase in GB of imaged data captured from the exhibits. We included the number of GB per case to control for the increase in DFU capacity. ‘Cases’ relate to individual exhibits that are submitted for analysis. These data are for exhibits seized and where an exact copy of the device’s data is taken by DFU, which handles complex digital data-rich cases. Other departments complete additional data downloads, for example from mobile phones, but are not included in these data.

Police forces are inconsistent in what digital evidence and records they require from rape victim complainants leading to a postcode lottery (Barr & Topping, 2018). In a freedom of information request, police forces did not provide digital forensic data as they are not being collected centrally, or the requests for data would have been too resource intensive to address (Big Brother Watch, 2017). HMICFRS’s assessed that while some forces have made good progress in understanding the scale of digital evidence in crime, others are in the ‘starting blocks’ (HMICFRS, 2015).

Since digital forensic examinations do not have a separate category within the overall forensic spend of police forces, it is difficult to track the annual policing costs for digital forensics overtime. Digital forensic spend is one of many categories captured in ‘other forensic services’ and this spend has increased from £61 million in the year ending 2013 to £78 million in the year ending 2018 (Home Office, 2019). The Digital Forensic Science Strategy reported that police forces in England and Wales spent approximately £120 million on digital forensics in 2019/20 and there were 1,500 full-time staff working in frontline DFUs. The strategy also reported that the average DFU will process approximately 930 computer and 5,000 phone items annually with an average turnaround time of ten weeks for phones and 17 weeks for computers (NPCC, 2020). The College of Policing have reported that digital investigators can each receive over 300 exhibits to examine every year (HMICFRS, 2020), and the methods used to collect digital forensic evidence can add to the volume of analyses being conducted (Jordan, 2008).

Increased digital media use, resulting in a rapid rise in the presence of digital forensic evidence, presents a challenge to the CJS (Science and Technology Select Committee, 2019). For example, the 2017 HMICFRS Peel inspection report suggests that, although 17 forces showed improvements in their management of digital data, including reducing delays (n=2) or good prioritisation of cases (n=6), some police forces (n=6) have long backlogs of cases awaiting digital forensic examination and others require a better approach to retrieving data (n=3) (HMICFRS, 2018). The Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) has raised concerns that the UK police forces’ approach to mobile phone data extraction (MPE) was inconsistent and there was an overly wide approach, i.e. too many MPEs were being carried out (ICO, 2020). Garfinkel (2010) identified that an emphasis on completeness of the data examination, with a desire not to miss potential evidence, was problematic for investigations, and may add to the volume of digital examinations. Daly (2021) also highlighted concerns that ‘irrelevant’ digital evidence (driven by the desire to gather all potential evidence) may be used against the victim-survivor to undermine their credibility.

The tools, techniques, processes and procedures used in digital examinations must meet scientific standards to be acceptable as potential evidence in criminal cases (Karie & Venter, 2015). Casey (2019) highlighted that increases in the volume of data can magnify issues inherent to the field, including the potential for technical and interpretive errors, inadequate understanding of the operations of hardware and software, and flawed interpretation of data. These limitations to, or errors in, digital forensic examinations are all likely to be amplified by the rate of change in the field (Casey, 2019). The increased collection of digital evidence has resulted in many police forces reporting that the associated increased digital demands have led to delays (HMIC, 2015) and cases not being pursued due to the workload for digital forensic examiners (Gogolin, 2010).

Delays in processing digital evidence can lead to considerable waiting times for charging decisions to be made and prosecutions to be conducted (Rumney & McPhee, 2020). This can impact the CJS as delays in the investigative process, particularly for sexual and domestic abuse offences, may have a severe impact on victims. Victims may have to give up their phones for long periods of time, which is especially acute when they are going through a challenging time in their life because of sexual victimisation (Casey, 2019). When there is a pre-existing relationship and high levels of digital communication to examine, victims are particularly at risk of re-victimisation due to shortcomings (e.g. lengthy investigations and delayed trials) within the CJS (Jordan, 2008; Randall, 2010). The Victims’ Commissioner for England and Wales recognised that due to the complexity of sexual assault cases, enquiries can be protracted, for periods of weeks and months (Victims’ Commissioner, 2019).

Dodge et al. (2019) assessed the complexity of cases and the use of digital forensic evidence in sexual assault cases in Canada. In this qualitative research, researchers undertook 70 interviews and two focus groups with police personnel in sex-crime units. Interviewees reported that most of the cases they investigated had digital evidence because the victim and suspect almost always knew each other and had built up a digital history. As a result, investigators commented that there was a backlog of cases and increased waiting times, which had a negative impact on the victim and the CJS. The digital evidence was, therefore, identified as being a ‘double-edged sword’, in that, due to the often-pre-existing relationship between victim and offender, more digital forensic evidence was available to help investigations into ‘difficult to prove’ sexual assault cases, but the complexity of the cases, and the burdens on both investigators and victims had increased due to the digital forensic examinations.

2.6 Summary

Digital and mobile technology use has grown rapidly in recent years. This along with the plethora of digital devices and wide range of digital evidence, has contributed to an increase in demand for digital forensic examinations during criminal investigations. However, there is little empirical research that has specifically examined the increase in digital forensic examinations in criminal investigations over time. A deeper understanding of the volume and nature of digital examinations is, therefore, required. Conducting a more robust examination of the scale of digital forensic demand on police investigations will attain additional knowledge of how digital forensics can be forward managed. As no national data are available, to examine any changes in the use and volume for a range of digital devices nationally, the current study followed a similar methodology to McMilllan et al. (2013).

3. Methodology

The current research followed a similar methodology to that adopted by McMillan et al. (2013) and aimed to update and expand their findings to reflect technological developments over the past decade. We searched three legal databases – Lexis®Library (LexisNexis), Westlaw UK and BAILII – for criminal cases heard by the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) in 2010 and 2018. We then reviewed the identified appeal case judgements to assess any change in the presence of digital evidence over the two years. We analysed the data by type of offence and by type of evidence. We reviewed and assessed the written judgements on cases with digital evidence present in the case summaries to establish the relevance of digital evidence to the case.

3.1 Approach

The Lexis®Library, Westlaw UK and BAILII databases used for this research hold legal materials, transcripts of judgements and law reports containing the official transcripts from the higher courts, including the Court of Appeal (criminal) division cases. In many appeal cases, the transcripts provide detailed summaries of individual criminal cases and include details of evidence presented when the case was heard in the Crown and Magistrates’ Courts.

Criminal cases in England and Wales are initially heard at Magistrates and Crown Courts. Magistrates can deal with some cases but their powers are limited. More serious matters are committed for trial or sentence to the Crown Court. A person convicted and sentenced at either Court may appeal against their conviction or sentence. If the person was convicted and sentenced at a Magistrates Court, their appeal hearing will be heard at the Crown Court. For cases where a conviction or sentence takes place at a Crown Court, appeals are made to the Court of Appeal Criminal Division (Gov.UK, n.d.). A total of 7,250 applications for leave to appeal were received by the Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) in 2010 and 5,101 applications in 2018 (Royal Courts of Justice [RCJ], 2020). In most cases, a High Court Judge (the single Judge) reviews applications for leave to appeal against conviction or sentence and decides if leave to appeal should be granted or refused. If granted, the appeal is listed for hearing by the Full Court of Appeal (this could be a three- or two-Judge Court, depending on the case). If the single Judge refuses leave to appeal, an applicant can renew their application, in which case it will be prepared for a hearing before the Full Court to consider whether leave to appeal should be granted or refused (Judiciary for England and Wales, 2021).

The Court of Appeal (Criminal Division) publishes statistics annually, which includes figures on the outcome of appeals against conviction and sentence (and others e.g. confiscation orders). In 2010, 2,577 Court of Appeal results were recorded and in 2018 there were 1,411 cases for which a result was recorded (RCJ, 2020). These figures indicate the volume of cases heard at the Courts of Appeal for each year and may include cases that are not within scope of the current research, for example, cases with 2009 and 2017 citation numbers which were not included in the current research.

When the Court makes its final determination of a case, it will give a judgement, usually in open Court, at the hearing. The judgement is transcribed and approved by the Judge who gave judgement. Usually, the judgement will include a summary of the relevant facts and the grounds of appeal before setting out its conclusions and the decision that the Court came to. This is critical for the current research as few decisions at the Magistrates or Crown Court are officially recorded in law reports (Stevens et al., 2021). The Court of Appeal judgements are referenced, which includes the date of hearing, jurisdiction of the Court, the case name and the unique case number (citation index). In many cases, judgements are distributed to law reporters and publishers of legal materials for publication on their websites.

We used the information in these judgement summaries as the source material for assessing changes in the presence of digital evidence dealt with in police investigations. For this report, we may refer to the appeal case judgement transcripts as ‘case summaries’ as they contain a summary of the relevant facts, including the evidence for each appeal case. These should not be confused with The Criminal Appeal Office’s case summaries produced for every case that goes before the Court. In their study, McMillan et al. (2013) demonstrated that it was possible to glean key information from the judgement on the presence of digital evidence. However, some technical details were lacking.

3.2 Data protection

While the data collected from the legal databases were not personal data, we exported the case names and citation numbers that could identify an appellant. We kept the case names and citation numbers separately in a password protected spreadsheet and only for as long as required to undertake a matching exercise. This allowed duplicate cases within the dataset to be identified and removed.

3.3 Selection of comparison years and data cleaning

The current research focused on data from two years, 2010 and 2018. We chose 2010 primarily because this was the last full year of data analysed by McMillan et al. (2013) and allowed examination of trends post 2010. In addition, since the first iPhone was launched in January 2007, 2010 would act as a helpful baseline that reflects low levels of smartphone take-up (appeal cases are likely to be heard some time after the offence). In this study, typical elapsed times between offence and appeal were two years. By comparing 2010 with 2018, we could assess any changes from the start of the smartphone era.

We initiated an extensive data cleaning exercise before undertaking any analysis. Combined, the three databases generated 5,748 and 2,989 appeal entries in 2010 and 2018, respectively. According to published statistics, these figures are far higher than the equivalent number of cases with results recorded by Courts of Appeal in each year. The two main reasons for the difference between the database entries and published statistics are out-of-scope cases and duplicate entries.

We deemed the following case summary entries to be out of scope:

- the case was from a Court outside England and Wales

- the case summary referred to a point of law (for example, pointing to Attorney General advice or case precedent) or was for a Confiscation or Protection Order and contained no/very little evidential detail

- the case date was out of scope

- the case summary included company names or corporations (i.e. the case did not relate to an individual)

- the case was not a criminal citation (i.e. it was a family or civil case)

- the case summary contained null and void details

This first data cleaning exercise eliminated 31 out-of-scope database entries across the three databases in 2010 and 76 in 2018. The second data cleaning exercise, at the review stage, eliminated another 101 cases in 2010 and 81 in 2018.

A far bigger issue was the existence of duplicates. Duplicates occurred for two reasons. First, the case was reported in two, or sometimes all three, databases. Second, there were multiple entries covering separate hearings for the same case. In these cases, the initial or intermediate hearings tended to contain less comprehensive case summaries. In total across the database populations, we identified 2,487 duplicate entries in 2010 and 1,201 in 2018. We discovered some further duplicates while reviewing the judgement transcripts (see tables 2a and 2b in Annex A for a full breakdown of the numbers removed in the cleaning exercises).

The final appeal case dataset figures align reasonably closely with the Court of Appeal hearing results statistics for the two years. The number of reviewed summaries identified for 2010 (minus the duplicates) was 2,765 cases, 7% more than the equivalent figure of 2,577 from published RCJ statistics. The equivalent figures for 2018 were closer – 1,386 cases were identified in the dataset, 2% less than the 1,411 Appeal Court hearings results.

In practice, the number of cases reviewed was below the target figure – the estimated number of unique cases to be reviewed. This was due to the practicalities of identifying unique and duplicate cases. Some appeal cases – particularly those relating to appellants under the age of 18 or those involved in sexual offences – were anonymised across two of the three legal databases. This made it more difficult to ascertain whether the case was a duplicate, particularly when there were multiple cases with the same case initial.

At the later review stage, some cases which were initially classified as duplicates – and excluded from the review process – were, upon more detailed investigation, identified as unique cases. It was decided not to extend the review process at this stage of study. The number of individual cases that should have been reviewed but were incorrectly identified as a duplicate and excluded was 165 in 2010 and 101 in 2018.[footnote 6] Table 1 summarises the key statistics for the stages in building the core appeal case dataset.

Table 1. Number of appeal judgements resulted at court, and numbers identified at each stage of data collection and review process

| Stage of data collection | 2010 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|

| Court of Appeal judgements resulted(a) | 2,577 | 1,411 |

| Combined database population | 5,748 | 2,989 |

| Estimated unique number of cases in the legal databases | 3,230 | 1,712 |

| Target number of cases to be reviewed | 2,990 | 1,434 |

| Actual number of reviewed cases used in the dataset | 2,664 | 1,305 |

(a) Source: RCJ annual tables – 2020, table 3_8

3.4 Review of appeal judgement summaries

We used the judgement summaries to review and assess whether offences could be classed as having a digital component. Initially we applied a keyword approach, drawing heavily on the technique used by McMillan et al. (2013). We developed a list of keywords relevant to digital evidence and its extraction to identify relevant cases within the dataset. Unfortunately, this approach turned out to be overly complex and poor at discriminating between digital and non-digital cases (see Annex C). While McMillan et al.’s approach had been effective at identifying appeal cases involving mobile phones, the proliferation of digital devices and platforms – and their corresponding terms – made a keyword search approach for this study markedly more complex and time-consuming. In the end, individual researchers identified and reviewed each case summary and assessed them case-by-case. This yielded a much higher degree of confidence in the analysis but was labour intensive.

The appeal judgements were reviewed by Home Office analysts using CloudNine. CloudNine is a cloud-based legal review platform which enables multiple analysts to work on batches of summaries simultaneously, summarising the text into a coding framework – i.e. the review questions. A summary version of the coding framework is given below. The full coding framework is in Annex B.

- database source: LexisNexis, Westlaw, BAILII

- age and gender of appellant

- offence category (highest grouping level), rape cases identified separately

- digital/non-digital evidence in the case summary

- type of digital evidence (primary and secondary)

- physical device holding the evidence

- weight of the digital evidence (high/medium/low)

- date of offence (first offence, if a series)

- appeal judgement date

- appeal outcome

- date of arrest (only for all sexual offences for 2018 and rape offences only in 2010 and only taken from LexisNexis)

- date of conviction (only for sexual offences for 2018 and rape offences only in 2010 and only taken from LexisNexis)

- a free text box allowed analysts to include brief review notes (e.g. to clarify case review details) or to confirm that case had been reviewed for quality assurance reasons

Defining digital evidence

We used the FSR Codes of Practice and Conduct (Forensic Science Regulator, 2020) to inform the definition of digital material and guide whether a case should be classified as digital for the purposes of the research. On this basis it was decided that digital material captured by the police or police staff (e.g. body-worn video, data collected at the scene by police practitioners) or independently of victims, witnesses, suspects (e.g. CCTV) would be out of scope. A case where evidence related solely to body-worn video and/or CCTV and included no other digital components, would be classified as non-digital for the purposes of the coding exercise.

To summarise, the following digital evidence was in scope for the research:

- mobile phone cell-site analysis

- internet and personal computing (search history and files)

- calls and communications/audio

- mobile device data – texts, social media, images

- network intelligence – computer network traffic information gathering

The following was out of scope for the research:

- incident scene and network forensics (data captured by practitioners at the crime scene)

- CCTV (an Internet of Things camera would have been in scope)

- automatic number plate identification

- video footage from body-worn video cameras

Although the coverage of appeal judgements within each of the three databases varied, the content of the appeal transcripts on the same case was remarkably consistent. This meant that there was little added value from seeking out duplicate entries on other databases, where these existed.

An offence was categorised as having digital evidence if there were references to how the evidence was assessed to support the case presented at court. For example, if the case summary mentioned that call records placed the offender in a particular location at a particular time, this would be classed as a digital case. Similarly, if text messages provided a chronology of events before or after an offence, this would be considered as digital evidence. However, references to simply making a call with no further details related to these being used as evidence were classified as non-digital (see Annex B). Where there were multiple types of digital evidence within the summary, the two types we judged to be most crucial for the case were collected within the coding framework. These were classified as ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ elements, with primary elements being perceived as carrying more evidential weight, where it was possible to make this assessment. The decisions reached were, to some extent, subjective and made based on the material presented in the appeal judgement summaries. Where there was doubt, the team discussed the case.Analysts also made a subjective assessment on how relevant the digital evidence appeared to have been within the police investigation, or at court and during the appeal. Using the definition of ‘relevance’ described by McMillan et al. (2013), we assessed the evidence as follows:

High – the digital evidence was relied on in court or was considered vital to the outcome of the case. The digital evidence was also high in relevance if it was mentioned that the police appeared to have spent a long time downloading or analysing it.

Medium – the digital evidence supported the case but was not perceived as vital to the case-building or the appeal. Other non-digital evidence was mentioned as being relevant.

Low – digital evidence was mentioned in the summary, but only in passing. There was no active language to describe the reliance on digital evidence.

Again, review team members discussed ambiguous cases to mitigate any potential biases in the analysis. A second reviewer independently assessed a sample of cases.

Reviewers were provided with a briefing pack including a coding framework to standardise their decision-making as much as possible (Annex B). In addition, regular meetings, held after every review of a batch of cases, ensured that reviewers were constantly checking their decisions with others. Independent reviewers again checked all cases as having digital evidence to ensure the digital assessment was correct, and randomly checked approximately one-third of the non-digital cases. An analyst, who had not previously reviewed that case and who ‘blind’ coded the cases, undertook reliability checks. The coding was then compared, and any differences reconciled.

As we consider below, aside from the atypical profile of appeal cases compared to the population of all police investigations, the main limitation of this approach is the amount of detail included in the appeal judgement transcripts. A reasonable hypothesis is that, typically, appeal cases may have many ‘digital’ components which are part of more routine enquiries but are not detailed within the judgement summaries. This is because they yielded no salient information, were just part of more routine elements of the investigation or were not considered relevant to the judgement. In this sense, the analysis that follows will certainly be only a minimum estimate of the presence of digital elements within criminal investigations. What is reported on is very much the visible part of the digital iceberg in criminal cases.

Testing for statistical significance

As the intention was to capture the entire population of relevant and unique judgements in 2010 and 2018, we can make a case for not using tests of statistical significance. However, some argue that it is good practice to apply significance testing on population data where some cells have small numbers. This can particularly be the case where findings are presented as percentages, as differences can look but not actually be reliable (in a statistical sense). For some offence types in this study the numbers of judgements was under 20 and it was therefore decided to apply significance testing for some of the analyses.[footnote 7]

4. Analysis and findings

4.1 Sample composition

In total, we reviewed 2,664 unique cases for 2010 and 1,305 for 2018. The different proportions reflect the decrease in the number of appeal cases resulting from the Appeal Courts in both years. Violence against the person offences contributed the largest percentage of appeal summaries reviewed, accounting for just over one-quarter (26%) of all case summaries in both 2010 and 2018. Sexual offences accounted for almost one-fifth (18% in 2010 and 19% in 2018), while drug offences accounted for 14% in both years. There were some slight differences in the proportions of other offence types, but the largest difference was for possession of weapon offences, which accounted for 6% of analysed appeal cases in 2018 compared with only 3% in 2010 (see Table 2 for details). A chi-square test of all offence types found the offence make-up to have changed between 2010 and 2018 (X2 = 29.39, df=10, p = .001), but when looking at each offence type individually, it was only the possession of weapons offences which had changed statistically significantly between years (p < .001).

Table 2. Volume and percentage of appeal cases reviewed by offence type for appeal judgements in 2010 and 2018

| Offence type(a) | 2010 N | 2010 % | 2018 N | 2018 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arson and criminal damage | 43 | 2% | 14 | 1% |

| Drug offences | 371 | 14% | 188 | 14% |

| Fraud offences | 226 | 8% | 92 | 7% |

| Miscellaneous crimes against society | 236 | 9% | 95 | 7% |

| Possession of weapon offences | 79 | 3% | 76 | 6% |

| Public order | 52 | 2% | 16 | 1% |

| Robbery | 216 | 8% | 114 | 9% |

| Sexual offences | 481 | 18% | 245 | 19% |

| Of which rape offences(b) % is of sexual offences | 195 | 41% | 104 | 42% |

| Theft offences | 273 | 10% | 123 | 9% |

| Violence against the person | 686 | 26% | 341 | 26% |

| Of which homicides where a rape offence was also listed, (b) % is of violence against person | 9 | 11% | 6 | 2% |

| Offence not known | 1 | 0% | 1 | 0% |

| Total | 2,664 | 100% | 1,305 | 100% |

(a) Coding was based on the primary (i.e. most serious) offence where the appeal case involved multiple offences

(b) Where an appeal case included the offence of rape this was recorded. Most rape cases were classed as sexual offences, but some rape offences were recorded in the violence against the person crime category. This was where the most serious offence was a homicide, but a further offence of rape was also identified in the appeal case summary

We examined the demographics of appellants across all the appeal judgements (see Table 3). Cases were overwhelmingly brought by males. For 2010 appeal cases, where gender was recorded (n = 2,656), 91% of appellants were male. For 2018 (n = 1,305), the proportion of males was 94% – a statistically significant change (X2 = 8.68, df = 1, p = .003). This is in line with the profile of persons convicted at Crown Court – in 2010, 89% were male and in 2018, 91% were male (MoJ, 2020). While male appellants dominated for all offences, the pattern varied across different offence types. Lower proportions of male appellants were found for miscellaneous offences against society (80% in 2010 and 86% in 2018) and public order offences (87% in 2010 and 88% in 2018). For 2010 and 2018, the largest proportion of appellants were aged 21 to 30 (33% in 2010 and 35% in 2018). Full details of cases reviewed are in the accompanying data tables in Annex A. Table 3 sets out the appellants’ gender in both years.

Table 3. Percentage of male and female appellants and totals, by offence type and year

| Offence | 2010 | 2018 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | N | Male | Female | N | |

| Arson and criminal damage | 86% | 14% | 43 | 86% | 14% | 14 |

| Drug offences | 91% | 9% | 371 | 93% | 7% | 188 |

| Fraud offences | 83% | 17% | 226 | 90% | 10% | 92 |

| Miscellaneous crimes against society | 80% | 19% | 236 | 86% | 14% | 95 |

| Possession of weapon offences | 90% | 10% | 79 | 99% | 1% | 76 |

| Public order | 87% | 13% | 52 | 88% | 13% | 16 |

| Robbery | 97% | 3% | 216 | 100% | 0% | 114 |

| Sexual offences | 98% | 2% | 481 | 98% | 2% | 245 |

| Theft offences | 92% | 8% | 273 | 93% | 7% | 123 |

| Violence against the person | 91% | 9% | 686 | 92% | 8% | 341 |

| Total percentage and number* | 91% | 9% | 2,664 | 94% | 6% | 1,305 |

*Unknown offence type for one case in 2010 and 2018

4.2 Digital evidence in appeal judgement summaries

The focus of the study was to explore the extent to which appeal cases show a change in the proportion that reference digital evidence. However, it is important to note that this is against a backdrop of a 45% fall in the total number of appeal cases between 2010 and 2018. Overall, the analysis reveals a marked increase in the proportion of appeal cases where digital evidence was referenced between 2010 and 2018. In 2010, digital evidence was referenced in just over one-fifth (21%) of appeal judgement summaries. In 2018, the proportion of cases with digital evidence had increased to just over one-third (34%) of the appeal cases reviewed. Overall, the change in cases containing digital evidence was statistically significant (X2 = 68.52, df = 1, p < .001)

The proportion of cases with digital evidence increased across all offence types comparing 2010 with 2018 (see Figure 3 and Table 4). Applying the chi-squared test of significance across the two years showed statistically significant differences for drug offences, sexual offences, violence against the person and miscellaneous crimes against society offences. In 2018, digital evidence was most commonly found in drug offence appeal summaries, 58% up from 31% in 2010 (X2 = 28.15, df = 1, p < .001). For sexual offences, the proportion was 47% in 2018 compared with 32% in 2010 (X2 = 16.61 df = 1, p < .001). For rape cases, 44 out of 195 cases (23%) in 2020 had digital evidence present in the case summary. The proportion had increased by 2018 when 47 of 104 rape case appeal summaries (45%) referenced digital evidence. For violence against the person (X2 = 4.21, df = 1, p = 0.04) and miscellaneous crimes against society offences (X2 = 7.94, df = 1, p = 0.005), the proportion of cases with digital evidence saw more modest increases across the period.

Figure 3. Percentage of appeal cases referring to digital evidence, 2010 and 2018: selected offence types(a)

(a) Excludes public order and criminal damage/arson offences due to small numbers

Table 4. Number of appeal judgements by offence type and percentage referring to digital evidence, 2010 and 2018

| Offence | 2010 Total cases | 2010 % digital | 2018 Total cases | 2018 % digital | % point change 2010-2018 | Chi-square sig test 2010 & 2018 (c) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arson and criminal damage | 43 | 7% | 14 | 29% | +22(b) | ns |

| Drug offences | 371 | 31% | 188 | 58% | +27 | *** |

| Fraud offences | 226 | 15% | 92 | 28% | +13 | ** |

| Miscellaneous crimes against society | 236 | 14% | 95 | 29% | +15 | ** |

| Possession of weapon offences | 79 | 19% | 76 | 21% | +2 | ns |

| Public order | 52 | 4% | 16 | 44% | +40(b) | ** |

| Robbery | 216 | 13% | 114 | 21% | +8 | ns |

| Sexual offences | 481 | 32% | 245 | 47% | +15 | *** |

| Of which rape | 195 | 23% | 104 | 45% | +22 | |

| Of which other sexual offences | 286 | 38% | 141 | 49% | +11 | |

| Theft offences | 273 | 9% | 123 | 14% | +5 | ns |

| Violence against the person | 686 | 22% | 341 | 28% | +6 | ** |

| Total(a) | 2,664 | 21% | 1,305 | 34% | +13 | *** |

(a) In two cases the offence type was unclear

(b) For arson/criminal damage and public order offences, the number of appeals was small, particularly so in 2018. The percentage/percentage change figures should be treated with caution

(c) ns = not significant; ** = p<0.05; *** = p<0.001

4.3 Sources of digital evidence

It is also possible to analyse the main sources of digital evidence as mentioned in the case summaries. ‘Source’ here refers to the type of digital communication from which evidence is extracted (e.g. text message, social media), rather than the hardware (e.g. mobile phone, computer), which is covered separately. These were coded into primary and secondary sources as many offences drew on more than one source of evidence (e.g. text and social media).

Combining the primary and secondary sources, the appeal judgement summaries contained 786 and 653 sources of digital evidence recorded in 2010 and 2018, respectively. Figure 4 shows the respective shares of digital data across the two years. To some degree, the change across the two years reflects the changing nature of digital usage across the period, and in particular the growing use of social media. Calls and mobile phone data (i.e., calls, call records, cell-site analysis[footnote 8]) contributed a lower proportion of digital evidence in 2018 (30%) than in 2010 (44%). In contrast, the proportion of digital evidence obtained from social media (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp and Snapchat) increased from just 3% in 2010 to 14% in 2018. The proportion for images and audio data (i.e. photographs, images and video) was also lower in 2018 (22%) than in 2010 (27%). When SMS (text messaging) was the source of digital evidence, there was an increase from 20% in 2010 to 26% in 2018.

Figure 4. Source of digital evidence, 2010 and 2018(a)

Notes:

- ‘Calls and mobile phone data’ includes: call records, calls, cell-site analysis, contact lists and mobile contacts. ‘Social media data’ includes: Facebook, WhatsApp, Snapchat and other social media. ‘Images and audio data’ includes: photographs, images, audio and video.

(a) Based on primary and secondary sources of digital evidence in case summaries assessed as containing digital evidence. N = 786 (2010), N = 653 (2018). In total, all cases in 2010 were assessed as having at least one source of digital evidence and 97% of cases in 2018; 42% of cases in 2010 and 50% of cases in 2018 had at least two types of digital evidence in 2010 and 2018

In terms of the type of device identified in the appeal judgements, of the 555 judgement summaries reviewed for 2010 with digital evidence present, 475 (86%) included reference to a specific digital device. The corresponding figures for 2018 were 382 (86%) of the 442 summaries. The type of devices mentioned most often were mobiles/smartphones (Table 5), with a larger proportion present in the digital case transcripts in 2018 (89%) compared with 2010 (75%). Other digital devices, including hard drive, camcorder, DVD/CD saw lower proportions present in 2018 compared with 2010.

Table 5. Digital devices referenced in the 2010 and 2018 summaries

| Device type | 2010 N | 2010 % | 2018 N | 2018 % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile/Smartphone | 356 | 75 | 341 | 89 |

| Camcorder | 13 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Hard drive | 57 | 12 | 15 | 4 |

| Laptop/tablet | 22 | 5 | 22 | 6 |

| Recordable discs/CDs(a) | 15 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 12 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Total(b) | 475 | 101 | 382 | 101 |

(a) For 2010, there were 15 cases in 2010 with external storage, which included recordable disc/CDs (7), SD card (1), SIM card (4), USB storage (2) and floppy disc (1). There were no cases that included these storage devices in 2018

(b) Total number of case summaries assessed as containing digital evidence where the device was specified. Percentage totals do not add up to 100 due to rounding

4.4 Source of digital evidence by offence type – selected offences

This section explores sources of digital evidence by offence type. The analysis is limited to three main offence types: sexual offences (divided between rape and other sexual offences), drugs offences and violence against the person. These three offence categories have the highest number of appeals, which allows for more meaningful breakdowns of the sources of digital evidence.

Where the appeal judgement transcripts indicated any offence of rape, reviewers gave the offence type a discrete code. This was due to the particular concern about the growing importance of digital evidence in rape cases and its impact on investigations (see George and Ferguson, 2021). Reviewers categorised most rape cases under the higher offence category of ‘sexual offences’. However, they counted a few rape cases under ‘violence against the person’. In these cases, the primary offence in the appeal was a homicide, but a rape had also been committed. However, as the case reviewers could not say for certain if the digital evidence was associated with the rape or the homicide, they included the rape homicides under the ‘violence against the person’ offence category. There were 195 appeal judgements involving rape offences in 2010 and these had 63 primary and secondary sources of digital evidence referenced within the summaries. In 2018, there were half as many summaries with rape offences, but 75 sources of digital evidence. For ‘other sexual offences’ there were 286 (2010) cases with 166 sources of digital evidence and approximately half as many cases in 2018 (141) and 114 sources of digital evidence.

Table 6. Percentage of appeal cases with digital evidence and the number containing the source of digital evidence information by offence type, 2010 and 2018

| 2010 | 2018 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offence | Total offences | % with digital evidence | Number of sources of digital evidence | Total offences | % with digital evidence | Number of sources of digital evidence |

| Rape (excludes rape homicides) | 195 | 23% (n=44) |

63 | 104 | 43% (n=43) |

75 |

| Other sexual offences | 286 | 38% (n=108) |

166 | 141 | 48% (n=68) |

114 |

| Drugs | 371 | 31% (n=114) |

155 | 188 | 58% (n=109) |

140 |

| Violence against the person (incl. rape homicides) | 686 | 22% (n=148) |

210 | 341 | 28% (n=95) |

145 |

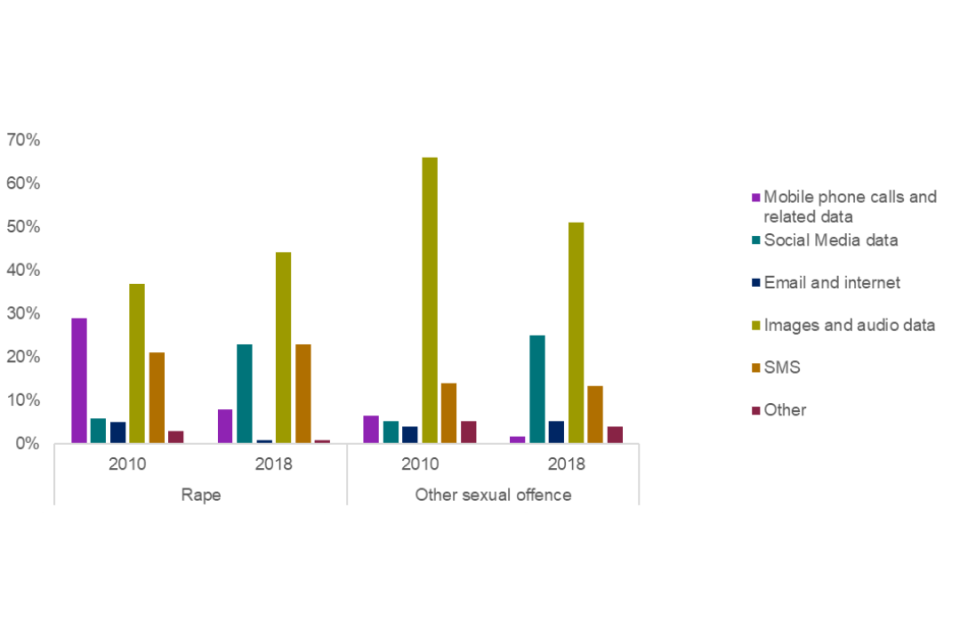

The largest proportion of the digital evidence for both rape and other sexual offences was categorised as ‘images and audio data’ (other sexual offences: 66% in 2010 and 51% in 2018; rape: 37% in 2010 and 44% in 2018 – see Figure 5). There were increases in the proportion of digital cases where the evidence was from social media data (i.e. Facebook, Snapchat and WhatsApp). These increased from 5% in 2010 to 25% in 2018 for other sexual offences, and 6% in 2010 to 23% in 2018 for rape cases.

Figure 5. Sources of digital data in case summaries for rape and other sexual offences, 2010 and 2018

Notes:

- Care should be taken with these data due to the reduced number of cases for analysis (e.g. for email and internet there were under 10 cases for each offence type/year). The analysis showed that there were some differences and similarities in the use of digital evidence between other sexual offences and rape offences; volumes for cases are in Annex A: Data tables for the report.

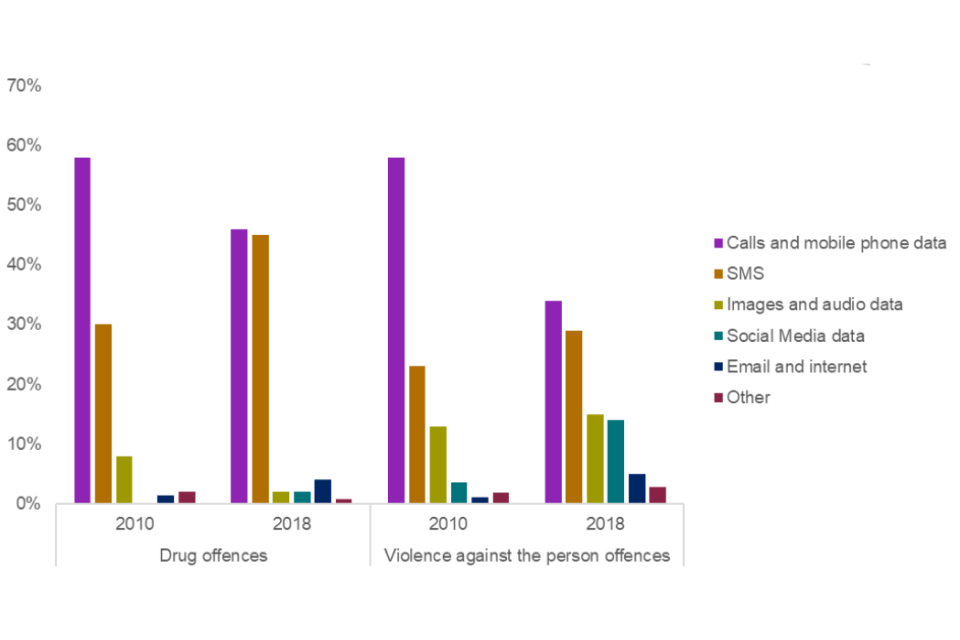

For drugs and violence against the person offences, ‘calls and mobile phone data’ were the predominant sources of digital evidence in both years (Figure 6). However, for both offence types, the proportion of cases citing ‘calls and mobile data’ decreased between 2010 and 2018 – down from 59% to 46% for drug offences and from 58% to 34% for violence offences. There was a corresponding increase in cases citing ‘SMS evidence’ across the two years, up from 30% to 45% for drugs offences and from 23% to 29% for violence offences. Modest increases in social media sources were evident for both offences, but by 2018 these accounted for only 2% and 14% of all digital sources for drug and violence offences, respectively.

Figure 6. Sources of digital data in case summaries for drug and violence offences, 2010 and 2018

Even for these more common offence types, the numbers limit the extent to which we can make confident statements about changes in the pattern in digital sources between 2010 and 2018. Some of the change will simply represent natural variation in the case mix in each year. However, it does appear that distinct digital evidential source profiles exist for different offence types, reflecting the nature of the offences committed and the evidence associated with them (e.g. the importance of call and mobile phone data in drugs and violence offences). Sexual offences, by contrast, have a different profile with image and audio data dominating.

4.5 Case durations

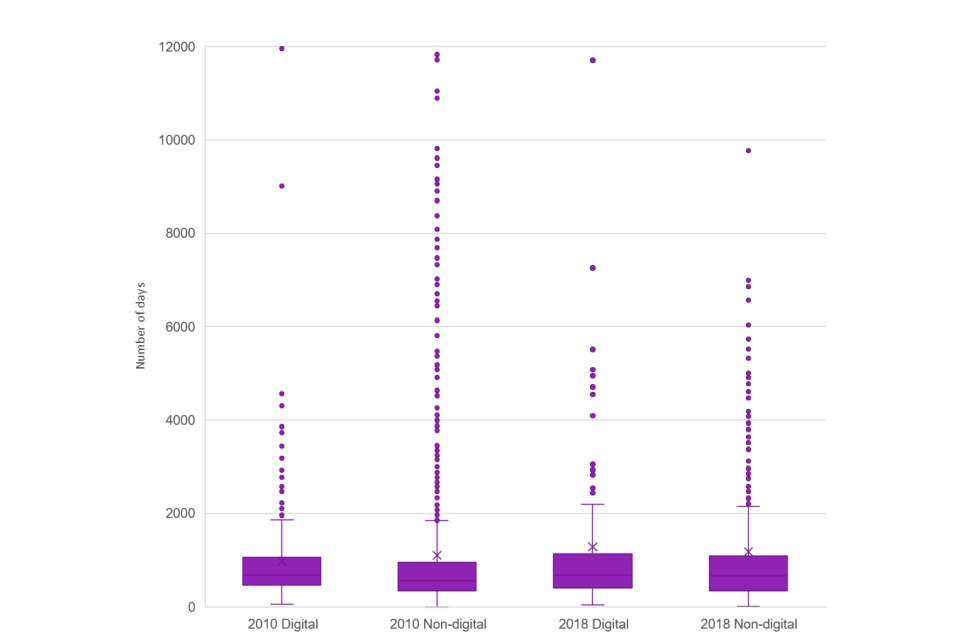

We calculated the time for all cases to proceed. The key dates were the date of the first offence and the date of the appeal outcome. Where the appeal related to a series of offences, the date of the first offence was recorded. To deal with the impact of ‘historical’ cases having a disproportionate effect on average values, the median number of days was preferred to the mean. Outlier cases were particularly marked for appeals involving historical offences, although a few appeals were heard very quickly after the offence.

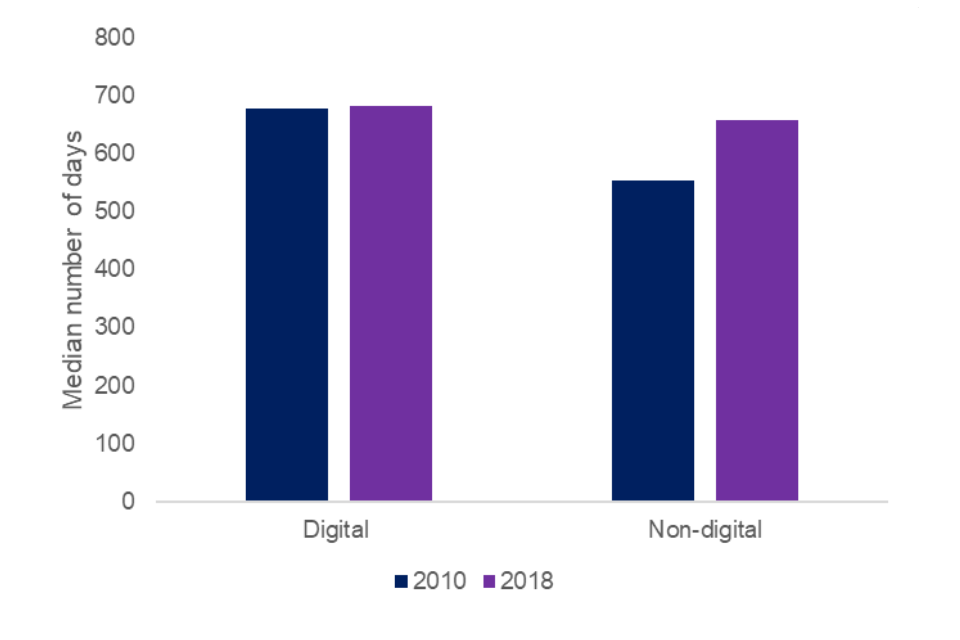

Figure 7 shows that for all the appeal cases reviewed, the cases with digital evidence had similar durations in 2010 (678 days) and 2018 (682 days). Cases categorised as non-digital had a lower median duration and there was a slight increase in the number of days between first offence date and appeal date for 2018 (658 days) compared with 2010 (554 days). The increase was not statistically significant using a Mann-Whitney test.[footnote 9] This is against a background of fewer Court of Appeal cases in 2018.

Figure 7. Median number of days between date of first offence and appeal date for digital and non-digital cases in 2010 and 2018

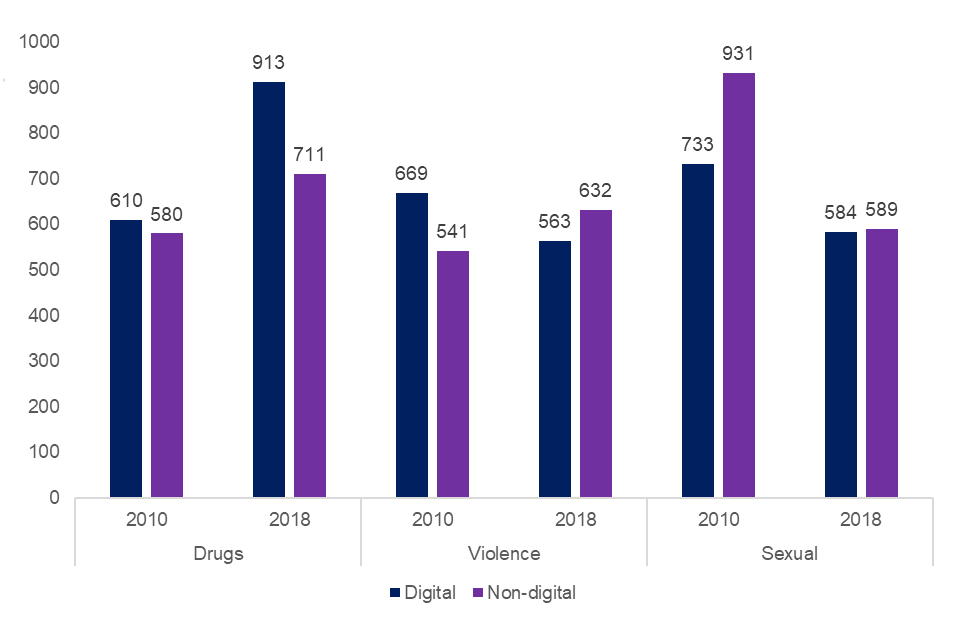

Some differences emerge between offence types with and without digital evidence. Figure 8 shows there was an increase in the median time from offence-to-appeal date between 2010 and 2018 for drug offences for both digital and non-digital cases. For violence against the person offences, offence-to-appeal durations decreased for digital cases between 2010 and 2018 and increased for the non-digital cases. For sexual offences, median days decreased between 2010 and 2018 for both digital and non-digital cases, with the digital and non-digital cases having similar median durations in 2018. These findings should be viewed against a backdrop of fewer appeal cases in 2018 compared with 2010. Since there are so many factors that influence offence-to-appeal durations – the time to report the offence, the time to charge, the time to trial and the time to appeal – it is hard to interpret these patterns. The critical point, however, is that for all appeal cases there is typically a two-year delay from offence to appeal for digital cases, and in this sense, the digital profile evidenced from the appeal judgements in this study more typically relates to digital usage in offences committed around 2008 and 2016.

Figure 8. Median number of days from offence date to appeal date for drug offences, violence against the person and sexual offences, 2010 and 2018

4.6 Evidential weight