Digital radio and audio review

Updated 28 April 2022

Decorative image

Executive Summary

Introduction

0.1 Radio is a great British success story. It has evolved to embrace new digital opportunities to maintain its universal appeal to audiences. It has innovated to remain current, vibrant and vital. Alongside a thriving radio market, new online audio formats including on-demand music streaming and podcasts from both existing broadcasters and new entrants have emerged and grown rapidly, bringing increased choice and new habits to the UK’s audio sector.

0.2 The Digital Radio and Audio Review was commissioned by the government in February 2020 with the objective of assessing likely future trends in listening and to make recommendations on ways of strengthening UK radio and audio. The Review was undertaken in conjunction with a broad cross-section of industry stakeholders and is intended to complement work already done or currently being undertaken to ensure a healthy future for a thriving UK media, such as the Cairncross Review,[footnote 1] the Online Harms White Paper and the Ofcom Public Service Broadcasting Review.

0.3 As set out in the terms of reference, this report describes sector commitments and options for future government support. The government will need to consider recommendations for future action on its part, and will publish its formal response in due course.

Overview

0.4 Radio remains a strong, trusted medium in the UK delivering significant public value. 89% of the population tunes in every week,[footnote 2] a figure which has remained remarkably consistent in the last decade. A feature of radio’s enduring popularity is its unique ability to be simultaneously an intimate medium while remaining part of a collective experience. Radio is a valuable and integral part of the UK creative economy with a reach across all parts of the UK. The BBC invests around £500m per year on radio content,[footnote 3] excluding distribution costs, while commercial radio’s annual revenues were around £703m in 2019.[footnote 4]

0.5 Radio is first and foremost a trusted medium and people turn to it for news, vital information and as a crucial source of company, especially the newly working from home. This was recently demonstrated during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. The BBC launched temporary local stations in key areas to help communities through lockdown, enhanced its news output both on air and on-demand with specialist commissions about the pandemic and provided virtual church services. Commercial radio expanded the availability of news and current affairs during the pandemic with the launch of the new Times Radio service, the expansion of local information and the growth in news podcasts. Community radio stations continued to stay on air, in spite of the COVID-19 restrictions, providing valuable local information to their communities.

0.6 Another good example of radio’s social impact is the joint industry initiative focusing on well-being and mental health, including the cross-industry Mental Health Minute campaign, and emergency programming focusing on pandemic-related content, particularly loneliness. In the absence of spectator access to live music and sport during the COVID-19 pandemic, radio delivered live performances from artists’ homes and later from COVID-19 controlled venues, big music events recreated through archive material, and - for the first time - live commentary of every Premier League football game.

0.7 Over the past 10 years, listening choices have expanded greatly thanks to digital technology and in particular to the successful development of the DAB digital radio platform. As well as online listening, there are 574 stations available on DAB across the UK, in addition to thousands of online stations and streams and 333 analogue (FM/AM/MW) stations.[footnote 5] There are also over 300 analogue community radio stations which collectively reach over 1 million listeners every week.[footnote 6] Smart speakers, which emerged only five years ago, are owned or accessed by a third of all adults, and account for 6% of all audio consumption. 64% of audio consumed on a smart speaker is live radio.[footnote 7]The rapid growth of streaming and podcasts demonstrates the enduring appeal of audio and the medium of radio in a multitasking world.

0.8 Broadcasters and technology providers have innovated to achieve continuing success, taking advantage of many new ways to reach listeners. Radioplayer is one example of successful cross-industry collaboration – a broadcaster-led, not-for-profit organisation dedicated to keeping radio listening simple on computers, smartphones, tablets and smart speakers, now with a sharp focus on in-car listening. BBC Sounds aggregates content from across its radio, music and podcast output to create a curated experience for listeners. Other platforms, including Global Player and Bauer’s Planet Radio, are also extending their content and functionality. As online listening increases, the challenge for broadcasters is to ensure their strong brands continue to resonate and for the government to ensure that UK consumers continue to have easy access to UK-generated radio and audio content.

0.9 Listener behaviour is also changing with the widespread availability of connected devices giving access to almost unlimited choice, accelerated by the uptake of smart speakers; changes that appear to have gathered further pace during the pandemic. This is particularly the case for younger audiences who are early adopters of on-demand audio services, sometimes at the expense of listening to live radio. For radio to remain strong and readily available to mass audiences, it is critical that the UK audio sector continues to innovate and evolve.

0.10 Future listening projections show that radio will retain a central role in UK media for at least the next 10-15 years. While it is impossible to make entirely accurate projections too far into the future, the Review’s conclusion is that live radio will still account for over 50% of UK audio listening in the mid-2030s. In terms of how radio and audio is delivered to the listener, with so many new ways to consume audio content, a hybrid future, albeit with the majority of listening being on broadcast platforms, seems the most likely for the foreseeable future. The Review examines the various distribution platforms and long term challenges of broadcasting on multiple platforms.

0.11 Radio’s future must be both digital and multiplatform. DAB digital radio has given listeners a greater choice of services - with small-scale DAB opening up new opportunities for smaller commercial and community radio services. But the landscape over the past 10 years has become more complex. IP delivered services - via smart speaker - have grown rapidly in the past 3 years and will be part of radio’s future.

0.12 The response to these challenges requires a strengthening of industry collaboration on future distribution including network planning, cost efficiencies and the need to progressively reduce environmental impact. There is also scope to strengthen industry collaboration to support radio listening in cars. In the home, regulatory change to support UK content providers will be necessary as more and more radio listening is consumed via new digital platforms. As radio - for the first time in its 100 years - becomes partially reliant on non-broadcast infrastructure, it will also be vital that its free-to-air route to market is guaranteed for the long-term, and new regulation, coupled with increased powers for Ofcom and possibly new competition powers, will be needed.

0.13 Radio’s audience must, it goes without saying, be central to the transition to a wholly digital and hybrid future. So while an eventual switch-off of AM and FM networks will help to reduce the long-term costs of dual networks, the transition needs to work for all listeners in all parts of the UK. AM - which according to estimates calculated for the Review now accounts for just 3% of all radio listening - has reached the point where the BBC, commercial radio and Ofcom need to prepare for the retirement of national services. However, traditional radio, including FM services, is valued by many listeners - particularly those who are older or vulnerable, drive older cars or live in areas with limited DAB or broadband coverage. On current trends, therefore, the Review’s conclusion is that FM will be needed until at least 2030.

0.14 Looking at the longer term, the projected decline in analogue radio listening (which Mediatique estimates will account for just 12%-14%[footnote 8] of all radio listening by 2030 according to their forecasts conducted for the Review) means that the UK radio industry should begin preparing the ground for a possible switch-off of analogue services at some point after 2030. A failure to prepare carefully for this scenario, or to take the necessary steps as an industry when radio is in a relatively strong position, would be to gamble with the future of the UK’s oldest and arguably most successful broadcast medium.

0.15 UK radio’s success has produced a creative sector that is well placed to succeed as listening changes in the future. While live listening to radio will increasingly share audiences with a range of on-demand formats in the future it is clear there will still be a central role for live radio. The UK radio and audio sector has weathered technology changes in the past and is already showing how it will adapt again through innovation in formats and distribution to deliver more to audiences. With collaboration across the sector, UK government support for the changing nature of radio, and a commitment to put audiences first, who would bet against it?

Chapter 1 – Background and scope of the Review

1.1 Radio sits at the heart of UK life. Still among the most trusted mediums for news[footnote 9] and information, radio reaches all parts of the country; it is free-to-air and a highly valued source of entertainment and of discovery; and it is a companion to the isolated and lonely. Over recent years, live radio has been strengthened by the emergence of a small - but dynamic - independent production sector that produces content for the BBC and commercial radio as well as adding to the growing presence of UK audio content on podcast and other audio platforms.

1.2 The value of live radio and of UK-produced audio content has never been more apparent than during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a third of commercial radio listeners have reported listening to more radio than previously,[footnote 10] and stations and audio content creators across the nation have responded with innovative initiatives and programming which has brought the country together.

Radio and audio industry response to COVID-19

The Mental Health Minute, marking its third year, was broadcast across the entire radio industry to 20 million listeners on over 500 stations. The unique, one-minute message on the importance of talking about mental health issues and reaching out included contributions from The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, England captain Harry Kane, and singer-songwriter Dua Lipa.

As millions of people were forced to stay in their homes, and were isolated from friends and families, BBC local radio teamed up with manufacturers, retailers, and charity Wavelength to offer free DAB radios to the most vulnerable people aged over 70.

BBC local radio’s Make a Difference campaign helped bring communities together and offered information and practical support, with initiatives including a laptop donation campaign to help pupils in need of devices while learning in lockdown.

BBC local radio launched new temporary digital radio services in Bradford, Wolverhampton and Sunderland, where Covid-19 cases were significantly increasing, to support listeners during the crisis and provide more localised information and news to the communities.

The BBC’s five pop music stations came together for a mass singalong to lift the nation’s spirits every Thursday morning during the lockdown, and Radio 3 and Radio 4 supported artists and cultural institutions through the BBC’s Culture in Quarantine initiative, keeping the arts alive in people’s homes with special commissions.

Community radio stations, through the efforts of volunteers, overcame disruption and restrictions to continue to stay on air to provide valuable local information and support to their communities. Throughout the Covid-19 crisis many community stations broadcast vital public service and health announcements and news to their communities in multiple languages, and donated free airtime to provide support for local businesses and charities.

Local commercial radio stations increased their commitment to news and information significantly throughout lockdown, broadcasting 25% more news bulletins on average that lasted 28% longer

Capital produced a special best of the Summertime Ball, simulcast live on Sky One, with special interviews from pop stars appearing on the station to talk about what the event means to them.

Children’s radio station Fun Kids launched a daily Stuck at Home podcast that included ideas for activities and expert advice on how to discuss the crisis in a relevant tone for younger ones.

XS Manchester broadcast a daily 3 minute speech comedy drama based on the empty streets of the city.

Absolute 40s, a 24-hour pop up station, celebrated VE day in lockdown with hits from the decade entertaining listeners as they took part in socially distanced celebrations across the country.

The Audio Content Fund greenlit 28 new public service projects in its emergency coronavirus round, including Heart’s Hometown Heroes, featuring short audio blogs from local key workers; Absolute Radio’s Front Room Festival, a celebration of live music in self-isolation; and talkRADIO’s Undiscussable, exploring the rise in domestic violence during lockdown.

Podcasters responded with daily content to reflect the rapidly moving news agenda and programming to support mental health and well-being.

1.3 Nevertheless, radio is facing significant challenges. While the BBC and commercial broadcasters have invested heavily in developing and improving DAB transmission infrastructure, and broadcast platforms continue to dominate both in-home and in-car audio entertainment, the options for what to listen to and the ways of listening to radio services continues to increase. Audiences are changing, distribution is changing, and connected audio and global streaming platforms such as YouTube, Amazon Music and Spotify are competing for the radio audience. The future is still a bright one - especially as opportunities open up for the audio production sector - but significantly less certain, and much will depend on industry continuing to collaborate to sustain a thriving audio ecosystem of UK-produced content.

Radio’s digital journey

1.4 UK radio broadcasters have been on a digital journey for more than 25 years, with the launch in the mid-1990s of DAB digital radio and the more recent emergence of internet radio and online audio services.

1.5 Progress to develop radio’s digital presence in the early 2000s was initially slow in spite of the development of the BBC’s new digital radio services in 2002. The 2008 recession put paid to plans to develop a second national commercial DAB network (at that stage), and curtailed efforts to develop DAB coverage. The initial costs of receiver equipment and the fact that the UK was an early adopter of DAB were also factors in the slow adoption of DAB by car and vehicle manufacturers.

1.6 The government’s Digital Radio Action Plan, launched in 2010, aimed to provide a clear framework to encourage the industry to work together towards securing a robust and viable digital future. By any measure, the collaboration has been successful. The financial support provided by the government alongside investments made by the BBC and commercial radio led to a major expansion of DAB network coverage between 2013 and 2018, resolving a number of network deficiencies including local DAB. Other initiatives such as the launch of the second national commercial multiplex, the extension of the Digital One commercial network to Northern Ireland and the launch of further local multiplexes since 2012 have helped to support the growth of new services over the past decade. Meanwhile, the joint efforts of the radio industry, led by Digital Radio UK and the automotive sector, have resulted in almost all new passenger cars now having DAB and DAB+ installed as standard, having been practically zero in 2010.

1.7 The development of radio’s own digital network supported a longer-term aspiration to switch off older analogue networks once sufficient progress had been made by listeners to move to digital platforms. This aspiration was defined in the Digital Radio Action Plan, which proposed that the earliest date that the government could consider setting a switch-off timetable for FM and AM networks was when digital accounted for at least 50% of all UK radio listening. The government considered this question again in December 2013, when the then Minister for Culture and the Digital Economy, Ed Vaizey, confirmed that although good progress had been made, with digital representing around 35% of all radio listening, an announcement of a future switchover timetable was premature.

1.8 Since 2013, the partnerships developed as part of the Digital Radio Action Plan have continued to support steady growth, boosted by the transition of radio listening in-car and more recently by the emergence of connected audio devices. In 2018, digital listening passed the 50% of all radio listening threshold. In response, the then Minister for Media and the Creative Industries, Margot James, announced in May 2019 that the government would set up a broad-based digital radio and audio review to help guide collective thinking about the direction of travel with digital and analogue broadcasting in the light of the wider changes in listener behaviours.

The Review

1.9 Over this time radio listening, and audio listening more broadly, had changed with the growth of IP-based services. In light of this, the Review was established in February 2020 and tasked with considering a range of longer-term issues facing radio in the next 10-15 years as online technologies mature, with a view to strengthening and protecting the core public value that radio provides to the UK.

The Terms of Reference were to:

(a) Investigate future scenarios for the consumption of UK radio and audio content on all radio and online platforms and assess the impact of these scenarios on access to UK radio services;

(b) Assess the impact of likely models of future listener trends on current and future distribution strategies for UK radio groups and industry;

(c) Make recommendations on further measures and collaborative actions to strengthen the UK radio and audio industry for the benefit of all listeners and to promote innovation.

1.10 Although the Terms of Reference make no explicit mention of a future switchover or setting of a future switchover timetable, a key issue for the Review was the progress of the evolution of radio listening from analogue to digital radio, which would underpin collective advice to the government on how long analogue radio services would be needed. It was clear from the outset of the Review that while digital radio listening remains strong, with growth of DAB+ services and the rollout of small-scale DAB licences, this is no longer a simple question of an analogue-to-digital switchover. Instead, consideration was needed of the present mixed ecosystem of: DAB listening and rapidly growing IP listening, increasingly via smart speakers; and on-demand options including music streaming and podcasts.

Approach to the Review

1.11 The Review has been led by the Digital Radio and Audio Review Steering Board (“the Steering Board”), composed of senior representatives from the BBC, the main commercial radio groups (Global, Bauer and Wireless), Arqiva, Radiocentre, techUK, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), and chaired by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS). The Secretariat was provided by DCMS supported by resources from Digital Radio UK (DRUK) and industry, with Ofcom acting as an observer.

1.12 Three main industry working groups were established. These working groups - which drew in a wider range of industry stakeholders and input - were asked to consider different aspects essential for the future development of radio and audio, namely:

-

changing listening habits and how the industry should evolve to stay relevant

-

the changing device and automotive environment

-

future network coverage and planning

1.13 Additional sub-groups were formed to look at two specific areas highlighted as priorities during early discussions:

-

the impact of online audio platforms, aggregators, smart speakers and voice-activation on the future of radio and audio

-

ensuring the widening of opportunities for talent from diverse backgrounds to enter the industry

1.14 The approach taken has been to try and reach a cross-industry consensus on the issues considered, and to reflect this in the conclusions and recommendations. This approach means that the focus has been on issues where there is a common or collective cross-industry interest or where a common industry-wide approach to issues is more likely to deliver benefits to the sector as a whole. There have been a few areas where there has been disagreement, and where there are dissenting comments, these are reflected in the text.

1.15 The analysis and recommendations have been underpinned by the commissioning of new research, which has provided additional insight on a number of the emerging trends and changes in listener views and behaviours. In all, nine separate studies were commissioned, and all are published with this report.

Research reports and studies commissioned by the Review

Mediatique - Future Audio Consumption in the UK, October 2019; Update December 2020

Mediatique - Ownership and use of audio-enabled devices in 2035, June 2021

(Mediatique - Explainer - Radio and Audio Reports)

Futuresource - Trends in Audio and Radio Consumption in the UK, February 2020

Plum Consulting - Wireless Delivery of Audio Services, January 2021

PwC - Consumer attitudes to devices and consideration to purchase, February 2021

Dynata - Ethnic minorities radio listening project, March 2021

Ethnic Opinions - Ethnic minorities audience perceptions and consumption of radio and alternatives, April 2021

Community Radio Audiences and Values, February 2021

RAJAR/Ipsos/RSMB - Audience Estimates for UK Community Radio Stations (April 2019 - March 2020), report prepared April 2021

1.16 The Review has also taken views from a number of industry stakeholders through a series of stakeholder engagement sessions and through discussions with key industry groups, including liaison with the UK audio production sector and a very detailed engagement with the manufacturing industry about the future prospects for DAB radio technologies. This approach - along with specific research commissioned by the Review - has enabled identification of issues that are likely to shape the way that radio develops over the next 20 years. In particular, it was identified that:

Radio continues to see a significant gap in terms of its use and engagement with different ethnic communities. While broadcasters have themselves carried out some research into the needs and interests of these communities (to drive programme development), there was no comprehensive research on the reason for the continued under-indexing and on how the radio industry could better serve all audiences. As a result, broadcasters and DCMS jointly funded two research projects (by Dynata and Ethnic Opinions), which are both published with this report. The two reports have provided the basis for recommendations to build on existing initiatives to make radio and audio more diverse and to increase the focus on sector training and skills.

The emergence and growing use of connected audio devices like smart speakers, and the shift of platforms into the radio and audio space, has started to impact on the strategy of UK radio broadcasters. A separate working group was established to look at this issue, and had the benefit of access to research by Frontier Economics (commissioned by Bauer Media Audio) to look at transfer of value between UK content providers and platforms, and how the increased penetration of platforms to carry radio services and related audio content could influence the future economics of the sector. In addition, Radiocentre commissioned MTM to examine issues of prominence and access on these platforms. This work has resulted in new thinking about the future challenges and the need for the government to consider extending protections being discussed for other digital markets to support UK radio and audio.

1.17 In addition, the government’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and set stricter targets to achieve reductions by 2035 apply to all industries, including radio broadcasting. The first cross-industry assessment of energy use by radio broadcasting networks is an important step, drawing on new work carried out by BBC R&D. This underpins an important recognition of the need to manage emissions across broadcast and receiving devices, and led to recommendations on the process for retiring analogue networks after 2030 in a way which minimises the impact of listeners switching to more energy inefficient devices.

International aspects

1.18 International trends affecting the development of digital radio in other countries were also examined, noting that the UK remains ahead of many other large nations in terms of the transition to digital, but that other online trends (including the growth of smart speakers) are prevalent around the world and could inform a view of likely future trends in the UK. Full details of these trends are set out in a report prepared by Digital Radio UK, which is also published alongside this report.

1.19 This report (Radio and Audio Review: International Market Report, September 2021) shows that across Europe, sales of DAB+ radios and digital radio listening are continuing to grow, with France and Germany launching national DAB+ multiplexes and countries beginning to introduce laws to mandate the sale of digital receivers; Switzerland has announced plans to implement a formal analogue-to-digital switchover. The strong and sustained shift towards DAB+ across Europe, and particularly in Germany, France and Italy is a positive development for UK radio, creating opportunities to partner with European broadcasters and audio producers, particularly on issues such as research and development and on cross-industry initiatives in areas where there is a common interest.[footnote 11]

Timing of the Review Report

1.20 It was initially intended that the Review report would be delivered in March 2021, but the ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic meant that this date was pushed back. It was agreed by all stakeholders that doing so would enable full consideration to be given to all issues while also taking account of some of the effects of COVID-19 on the radio industry - including the disrupted home-to-work travel caused by the lockdown, and the greater level of homeworking which has increased demand for radio and audio services.

1.21 The conclusions of the Review identify a broad range of measures that can help UK radio and audio continue to thrive, to deliver public value, and to grow the UK creative economy in sectors with significant global opportunity. With the right action being taken now by both government and industry, radio and audio in the UK will continue to be world-leading for some time to come.

Listening data used in the Review Report

1.22 At the time of writing the Review Report the most recent published listening data available is for Q1 2020 following the suspension of the RAJAR survey, which uses face to face methodology, in March 2020 due to COVID-19 restrictions. The Review, therefore, refers to RAJAR Q1 2020 and MIDAS Spring 2020 data in its analysis but notes that listening patterns and metrics will inevitably have shifted in the intervening months and reflects alternative more current data points where possible. The Review has not sought - unless this is absolutely necessary - to substitute alternative data for data that would otherwise have been available from RAJAR.

Acknowledgements

1.23 The Review Steering Board was chaired by Ian O’Neill, DCMS. Members were Travis Baxter, Bauer Media; Jimmy Buckland, Wireless; Will Harding, Global; Siobhan Kenny, Radiocentre (until July 2021); Shuja Khan, Arqiva; Peter Lawton, Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT); Lindsey Mack, BBC; Craig Melson, techUK; Ian Moss, Radiocentre (from July 2021); and Jonathan Wall, BBC. Neil Stock, Ofcom, was an observer.

1.24 The Review Steering Board has benefited from the contributions and expert insight received from across the UK’s radio and audio industry and beyond and we are very grateful to everyone - including those not mentioned here - who has helped us with their time and wise counsel, particularly given the pressures the whole industry has had to face due to the challenges of COVID-19.

1.25 First and foremost we would like to thank Yvette Dore from Digital Radio UK, who led the Secretariat and has kept the Review Steering Board and Working Groups to task. It is thanks to Yvette that discussions and deliberations of the Working Groups have come together into a common position for the final report. We would also like to thank Harry Reardon and Alex Petrovic in the Radio Team at DCMS, and Robert Specterman-Green and Janis Makarewich-Hall at DCMS for their support throughout the Review.

1.26 The Review depended on the work of the three Working Groups and would like to recognise the hard work and contribution made by Lindsey Mack and Robin Holmes at the BBC, Travis Baxter at Bauer Media, Piers Collins at Wireless, Glyn Jones at Arqiva and Will Harding at Global in leading these groups, as well as extending our thanks to Kirsty Leith at Global for all her help in supporting the Listener Group and to Dr Janey Gordon from the Community Media Association. We would also like to thank Jonathan Robertshaw at the BBC for his contributions to the steering board discussions and for his insights into future radio and audio trends.

1.27 The work of the Devices and Automotive Group was informed by insights from techUK and the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) and valuable input from device manufacturers, technology providers, retailers and car makers. We are very grateful to both Craig Melson (techUK) and Peter Lawton (SMMT) for their help in organising this. We are also very grateful to Jon Butler for his help on DAB to support the Distribution and Coverage Group including his work on the assessment of the environmental impacts of radio broadcasting, and to Graham Plumb, Peter Madry and Alan Hills at Ofcom for their work on network and spectrum planning summarised in the Ofcom Contributions to DCMS Digital Radio and Audio Review.

1.28 The Review has had the benefit of new audience research on radio and audio listening. Some of this, for example the research reports into ethnic minority listening and community radio listening, provides new perspectives on how radio is seen by different audiences. We are very grateful to Mike Ireland and Rupert Steele (Radiocentre), to Mark Crawford and Natalie Compas (Global), Alison Winter (BBC), Clare McNally-Luke (Ofcom) and Dr Tom Brocket (DCMS) for their help with the listening research programmes, and to Matt Payton (Radiocentre) and Philip Pilcher (Bauer) for their help with the research into new smart speaker technologies.

1.29 The Review looked beyond radio with a focus on the UK’s audio production sector. We have been greatly helped here by Tim Wilson at AudioUK and from roundtable sessions with Bernard Achampong, Neil Cowling, Tim Hammond, Will Jackson, Karen Pearson, David Prest and Kellie While. Our thanks also to the broadcasters and producers, over 50 in total, based in the Nations and English regions, who attended the roundtable meetings and shared their views and perspectives, which have proved invaluable.

1.30 The Review draws extensively on three research reports that are the basis for much of the analysis on future market trends and we are grateful to Mathew Horsman and the team at Mediatique. We are also grateful to Ford Ennals from Digital Radio UK for his insights into the evolving nature of the UK radio and audio market and for providing the overview of audio and radio trends in international markets which forms one of the documents published with the report.

1.31 The Review looked in depth at the long-term implications of the emergence of new smart speaker technologies and related topics around securing radio’s access to market in this emerging new environment. We would like to thanks all those who participated in the discussions on smart speakers to help us get a deeper insight into market trends and the challenges facing the UK radio and audio industry in particular, Andrew Crowfoot and James Hickman (Global), Mukul Devichand and Ben Rosenberg (BBC), Philip Pilcher (who coordinated some significant external analysis and related report drafting) and Shana Hills (Bauer), and Jimmy Buckland (Wireless).

Chapter 2 – Listeners and ensuring the appeal of radio and audio

Supporting listener choice, sustaining local broadcasting, and ensuring the industry offers the widest opportunities to the broadest audiences and workforce

Introduction

2.1 Radio and audio listening habits are evolving, influenced by the development of new services and the growing adoption of digital devices: not just DAB radios, but also smartphones and smart speakers, which have given access to a huge array of online audio. Nevertheless, the radio habit remains strong, with 9 in 10 adults in the UK tuning in for an average of 20 hours a week[footnote 12]. As of Spring 2020, live radio accounted for 72% of all UK audio listening, with on-demand music streaming accounting for 14%, followed by podcast listening at 4% and other forms of audio including listen again, audiobooks, online tracks, vinyl and CDs accounting for the remaining 10%. Online listening has grown in particular among younger audiences with on-demand music streaming accounting for 44% of 15-24s listening time and podcast listening accounting for a further 5%.[footnote 13]

SHARE OF AUDIO % (EXCLUDING VISUAL)

2.2 The Review formed a Listener Working Group - including research specialists and stakeholders from across the sector. This set out to:

(a) understand the changes in listener behaviour in much more detail and understand the factors driving these changes;

(b) assess how these changes might develop over the next 10-15 years;

(c) understand how well radio was serving different audiences and what actions might be appropriate to help UK radio and audio develop and strengthen choice for all audiences, particularly those groups that felt under-served by radio services.

2.3 A review of an extensive body of existing research on radio and audio listening, including research carried out by the BBC, Radiocentre and larger commercial broadcasters, enabled the identification of evidence gaps and led to the commissioning of new research in two areas to help inform the understanding of current and future trends:

-

An assessment of community radio listening across the UK, consisting of quantitative research to provide insights into community radio audiences, and an audience measurement project using existing RAJAR data to derive an estimate of reach for all community radio stations combined

-

Detailed research into radio and audio listening among ethnic minority audiences, consisting of a quantitative study examining the differences in radio listening between different ethnic communities, and a qualitative study on the attitudes and views towards the current provision of UK radio services amongst different groups of ethnic communities

The findings of these two research projects are discussed in detail later within this chapter and have been published alongside this Report.

Value of radio and UK audio

2.4 Radio remains a very powerful medium which establishes a direct and personal relationship with each listener. While the proliferation of devices such as smartphones and tablets has made it possible for listeners to download and/or stream content on the move, the intimate feel of radio and its ability to mix news, information, music and entertainment have ensured its enduring popularity. Radio also plays a vital role in providing high-quality, trusted local news and information.

2.5 Radio and audio provide a unique relationship with the listener and have the power to gain a loyal and committed following even in an age of so many media distractions. The mixture of private and public funding and community support, plus the PSB remit of the BBC and the wide breadth of commercial and community radio services, means that every radio audience taste can be catered for. Added to this now are the new digital audio formats of podcasting and audiobooks, which serve to further engage the listener and enable them to take a deeper dive into their areas of interest, as well as growing the opportunity for new and diverse presenter and production talent to break through. There is also a vibrant independent audio production sector with companies based around the UK, delivering through its content a wide range of ideas, stories, voices and talent to broadcasters and digital platforms.

2.6 There is always more to do to ensure that radio and audio are available on the latest new devices, including in the new generation of connected cars, but what is not in doubt is the ability of radio services and also new forms of audio content to create an environment for people to enjoy, learn, and feel a sense of community.

2.7 Radiocentre’s research[footnote 14] consistently shows that radio is one of the most effective advertising media, another demonstration of audiences’ engagement with the medium. Podcast ad revenues are forecast to more than double in the UK over the next few years, which is a further sign of audio’s ability to gain audiences’ attention.

How listeners access audio

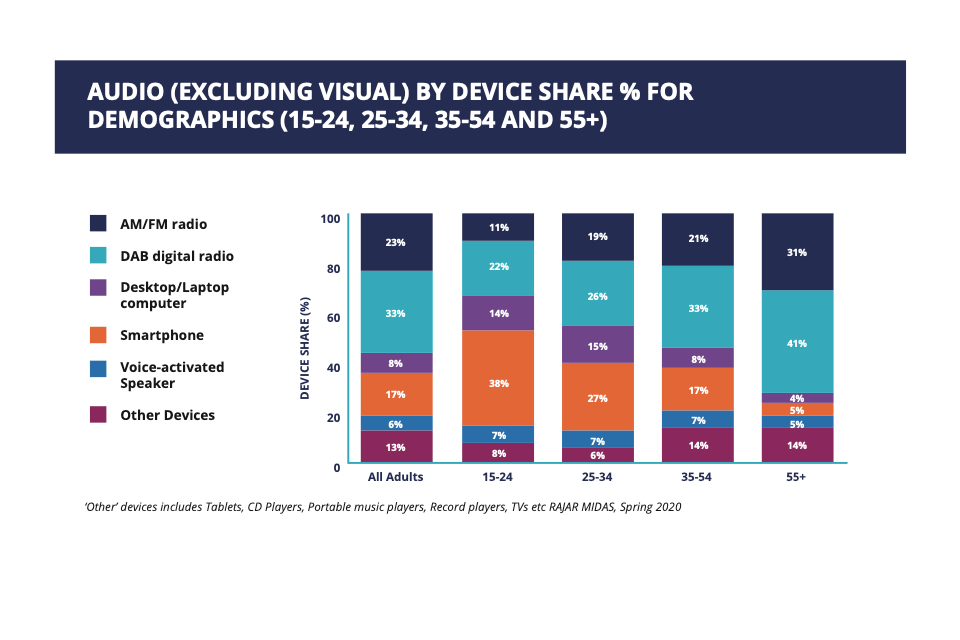

2.8 Listening on traditional FM/AM and DAB radios still dominates how listeners are accessing radio and other audio content, accounting for 23% and 33% of all audio consumption respectively, followed by smartphones on 17% as the next most popular audio-receiving device.[footnote 15]

AUDIO (EXCLUDING VISUAL) BY DEVICE SHARE % FOR ALL ADULTS

2.9 However, there are important differences between age groups which suggest this will change over time. Among 15-24 year olds smartphones are the first choice, accounting for 38% of audio consumption, with DAB accounting for 22% and FM/AM radios just 11%. Among 25-34 year olds, smartphones account for 27% of audio consumption, against 26% for DAB radios and 19% for FM/AM. In contrast, among listeners aged 55 and over, DAB radios account for 41% of all audio consumption and FM/AM radios a further 31%, with smartphones accounting for only 5%.[footnote 16]

AUDIO (EXCLUDING VISUAL) BY DEVICE SHARE % FOR DEMOGRAPHICS (15-24, 25-34, 35-54 AND 55+)

2.10 According to the most recent available MIDAS data, voice-activated smart speakers currently account for 6% of all audio consumption, with 33% of adults owning or accessing a smart speaker.[footnote 17] However, their role in radio, and audio listening, is growing rapidly, and according to Ofcom’s latest (and more recent) Technology Tracker (Q1 2021), as many as 42% of UK adults now regularly use a smart speaker.[footnote 18] Listening to audio is the most popular use of smart speakers by a significant margin, with 60% of all owners using one to listen to live radio, though with significant differences between age groups. Use of smart speakers to listen to the radio falls to 34% among 16-34s but rises to 67% among those aged 54 and over. In contrast, 67% of all smart speaker users listen to music via a streaming service on their device, rising to 77% of 16-34s but dropping to 55% of those aged 54 and over. This compares to the next most popular uses of ‘get weather report’ at 45% of all users and ‘searching for information online’ at 39% of all users.[footnote 19]

Smart speakers are explored in greater detail in Chapters 3 and 5.

2.11 Broadcast radio services continue to dominate in-car listening - which accounts for 24% of all live radio listening - and remains by far the most important platforms for live radio listening in-car. According to RAJAR Q1 2020, FM/AM accounts for 56% of all listening in cars, DAB for 42%, and IP for 2%. Live radio dominates in-car listening, accounting for 82% of all in-car listening hours.[footnote 20] However, the growing availability of connected audio services in cars (via phone mirroring or natively) represents an increasing challenge to the prominence of radio in the car as streaming services are presented alongside or even more prominently than radio services. These issues are explored further in Chapters 4 and 6.

Future radio and audio consumption

2.12 In order to understand likely future trends in radio and audio consumption the BBC, commercial radio groups and Arqiva commissioned Mediatique to model potential scenarios for the audio market in the UK between now and 2035, with a focus on forecasting the likely impact on live/broadcast radio. A summary of this modelling is included in Mediatique’s report for the Review - Future Audio Consumption in the UK (October 2019, updated December 2020). Mediatique analysed both the trends in the listening shares of different forms of audio, including live radio, on-demand music streaming and podcasts, and also how listening on different platforms, particularly FM, AM, DAB and online/IP platforms, would be likely to evolve in the long term.

2.13 Based on a simple extrapolation of current behaviours adjusted for demographic changes, Mediatique estimated that live radio listening would decline from its current share of 72% of all audio listening to around 66% by 2035. However, this does not take account of likely changes in behaviour as adoption of new digital platforms and services grows. Mediatique modelled a number of scenarios, ranging from a “moderate change” scenario, in which growth in take up of new devices such as smart speakers and connected cars grows less rapidly, consumers retain legacy behaviours and late adopters eschew patterns of use seen today among younger early adopters; through to a “radical acceleration” scenario in which take up of smart online devices accelerates both in the home and in-car, and consumers switch their audio consumption to online services at a much faster pace. Mediatique developed and refined a base case between these two scenarios.

2.14 Based on these scenarios, Mediatique estimated live radio’s share of total audio consumption would be between 46% and 58% by 2035. The base case estimate was 53%, suggesting that live radio will continue to account for over half of all UK audio consumption in 2035. Even in the most aggressive scenario, Mediatique forecast that live radio would remain the single largest form of audio consumed by listeners in the UK, significantly larger than either on-demand music streaming or podcasts.[footnote 21]

ADULTS 15+ SHARE OF AUDIO CONSUMPTION - SERVICE TYPE (% OF HOURS)

2.15 Mediatique also developed a number of scenarios for how listening by platform might develop. The recent, rapid growth in adoption of smart speakers, and the development of connected car technology, means that there is a great deal of uncertainty over how rapidly listening on online platforms will grow. It is clear from Mediatique’s analysis that online/IP platforms will grow in importance but that the main radio broadcast platforms (FM and DAB) will also remain very important for listeners.

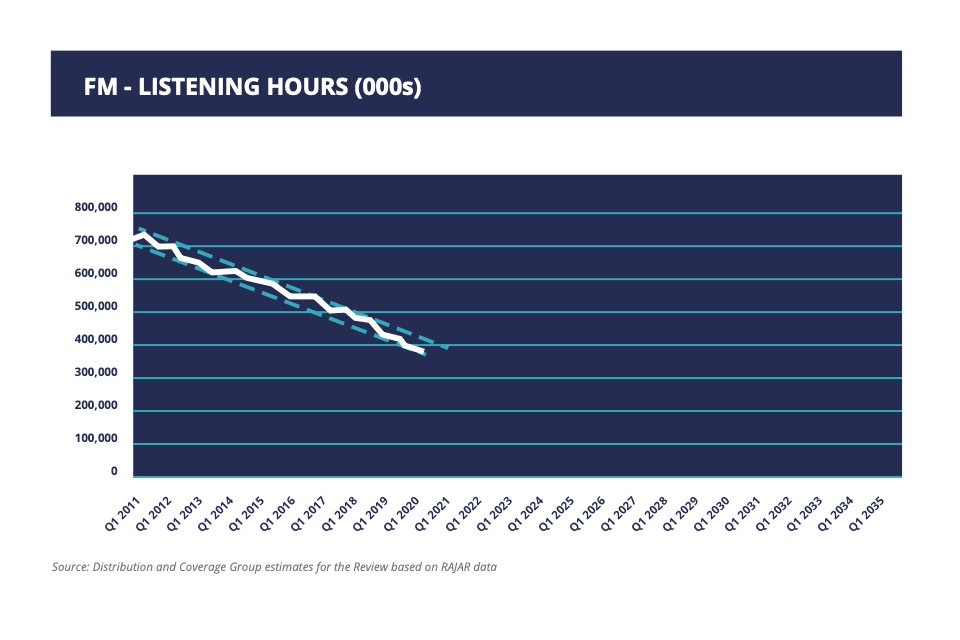

2.16 Mediatique estimated that online/IP platforms could account for 32%-40% of all live radio listening by 2035,[footnote 22] up from 14% in 2020. Although AM/FM listening is expected to continue to decline, broadcast platforms will continue to account for 52%-65% of all live radio listening in 2035.[footnote 23] Again, even in the most aggressive scenario, in which consumer adoption of connected devices continues to grow and listening habits change rapidly, broadcast platforms are still expected to account for more than half of all radio listening by 2035. This analysis also underpins the ongoing importance of FM to many listeners. While digital platforms now account for 59% of all live radio listening,[footnote 24] FM listening is expected to still account for around 12-14% of all live radio listening in 2030 and 8-10% of all live radio listening in 2035, according to Mediatique.[footnote 25]

MEDIATIQUE: SUMMARY OF OUTCOMES, RADIO LISTENING BY PLATFORM

2020[footnote 26]

What listeners want from audio services

2.17 Audience research consistently shows that listeners’ audio needs are both practical and emotional, including the need for mood enhancement, to know what is going on, to feel part of something and to feel connected.

2.18 Research conducted by Radiocentre in November 2020[footnote 27] reaffirms the valuable role live radio plays. In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, a third of commercial radio listeners reported that they were listening to more radio than previously. Reasons given centred on radio’s ability to satisfy both functional and emotional needs. In terms of function, 90% said they were listening to more radio because it kept them in touch with the world, while 89% said it kept them informed and 68% said it delivered trusted news. More radio listening was also happening because radio kept listeners company (84%), improved their mood (85%), and made them feel happy (82%).

THE ROLE OF RADIO IN LISTENERS' LIVES: FUNCTIONAL AND EMOTIONAL NEEDS (% AGREE)

2.19 While these needs existed for all audiences, the research also found that their importance varied between different audience demographics, and, importantly, the ways in which different audience groups met these needs also differed.

2.20 Live radio met a broad range of needs and stood out as the audio product that best met the need for company/support and keeping listeners ‘in the loop’. In the case of most other needs, on-demand listening formats are as important, or in some cases more important, in meeting the needs of audiences. The emotional needs which audio on demand was felt to meet most effectively (for example, mood management) were those to which younger audiences tended to attach most importance, compared to the more practical needs which dominated for older listeners.

2.21 Music remains as important an ingredient as ever in live radio. Research from both commercial radio and the BBC consistently shows that “variety of music” and “to hear music I like” are the most important reasons people listen to the radio.[footnote 28]

2.22 Speech radio stations attract an overall weekly reach of 33% of UK adults.[footnote 29] While Radio 4 remains the UK’s largest speech radio station, stations such as LBC and talkSPORT have enjoyed record audiences in recent years with new services such as talkRADIO, LBC News and Times Radio entering the market. The average age of a speech radio listener is 53, with speech stations generally having more success in attracting male than female listeners.[footnote 30] Podcasting appears to be filling a gap in the market for speech among younger listeners: 18% of all UK adults listened to podcasts in 2020 (up from 14% in 2019) with the highest reach being among 25 to 34 year olds at 27%.[footnote 31]

2.23 Notwithstanding the ongoing appeal of live radio, research indicates that on-demand audio services, both music and podcasts, have several defining characteristics which audiences find appealing, offering listeners control over what they consume, personalisation and the ability to share content, chiefly now on social media, as well as being able to offer a greater breadth of content, that it is hard for a fixed number of live radio stations to replicate.

2.24 It is therefore important that the sector continues to innovate with new ways of curating content and with new formats, as it has done through online platforms such as Radioplayer, BBC Sounds, Global Player and Bauer’s Planet Radio. Initiatives like the Audio Content Fund enable the sector to develop public service programming that is traditionally more difficult to produce on a commercial basis, while schemes such as the BBC Sounds Audio Lab,[footnote 32] a new programme for grassroots podcasters and audio creatives with diverse stories, are helping to develop capabilities in the UK audio sector to address these audience needs through online content.

Serving all audiences

2.25 Having established a picture and forecast of how listening trends, behaviours and expectations may evolve over the next 10-15 years, it was important to also understand in more detail how these trends will be seen among under-served audiences and vulnerable groups, and how the needs of these listeners can be served by radio and audio in this changing landscape.

Older and disabled audiences

2.26 Several specialist organisations were consulted, including the Royal National Institute for the Blind, Wireless for the Blind Fund, Voice of the Listener and Viewer and Wavelength, to seek their views on any specific challenges or opportunities for the constituent audiences they represent. Unsurprisingly, live radio was deemed very important for older and more vulnerable audiences, as a way for people to keep connected with society and also to counter isolation and loneliness.

2.27 RNIB reports that the vast majority, 93%, of blind and partially-sighted people listen to the radio. A report by Wavelength, a charity which gives media technology to lonely people living in poverty, shows that people felt less lonely after receiving a radio. In March 2020, Wavelength received over 9,000 applications in response to a radio distribution scheme for the over-70s who were vulnerable and self-isolating, which highlighted both how valuable radio is for older listeners but also how for many, even the most everyday technology is not readily accessible.

2.28 The specialist organisations also reported that some older listeners are reluctant to move to IP listening, with a lack of understanding of technology and the cost of broadband cited as potential barriers. For those that had moved to listening over IP, smart speakers were viewed as a positive development, especially for those with visual impairments. There was some concern raised around both privacy issues and the potential impact of unregulated online environments on already vulnerable listeners. All groups were reassured that listening to live radio is forecast to remain robust in the future.

Young audiences

2.29 As highlighted previously in this Report, live radio is under increasing competition when it comes to younger audiences. This comes especially from audio on demand music streaming services but also from podcasts as well as the music offer from visual platforms, notably YouTube.

2.30 In the ten years from 2010 to 2020, the weekly reach of live radio among 15-24s declined by 8% (or 7.1 pp) from 88.7% to 81.6%. During the same period, the average hours per 15-24 listener fell by 23% (from 16h18m in Q1 2010 to 12h30m in Q1 2020). As a result, the total listening hours of 15-24 year olds fell during the period by 34%. Of particular concern is that young audiences do not seem to sufficiently grow into radio later in life to compensate: 25-34s today are listening to slightly less live radio (16h06m in Q1 2020) than they were ten years ago (16h18m among 15-24s in Q1 2010).[footnote 33] This suggests it is important for radio that listeners develop a strong live radio habit early on.

2.31 The UK radio industry is actively trying to address the shifting needs of these young listeners. Commercial radio has launched a number of new digital-only services such as KISS Garage and developed online audio players such as Global Player, while the BBC has further evolved BBC Sounds and launched, for example, a new stream of content to help young audiences manage stress and wellbeing. Existing initiatives show some signs of success but the challenge will intensify as online audio audiences grow, leading competing global providers to further increase their investment in music streaming and podcast services.

Black, Asian and minority ethnic audiences

2.32 RAJAR data consistently shows that radio listening is lower among ethnic minority audiences than White audiences. According to the most recent data, 77% of adults from ethnic minorities listen to the radio each week, in comparison to 89% of all UK adults, with commercial radio reaching 62% of ethnic minority listeners and BBC reaching 42%.[footnote 34]

2.33 To provide greater understanding of diverse audience listening, the Review commissioned research exploring radio and audio listening among ethnic minority audiences. An online survey was undertaken by Dynata in March 2021, with a nationally representative sample of 4,000 respondents split across four ethnic groups: White, Asian, Black and Mixed Race/Other ethnicities. This was followed up with in-depth qualitative groups and interviews carried out by Ethnic Opinions in April 2021. The headline findings of both Dynata and Ethnic Opinions’ studies are summarised below. The full reports are published alongside this report.

2.34 The research showed that ethnic minorities in the UK are less likely to listen to the radio than White audiences and those that do so listen with a lower frequency, as shown below. While the methodology of this research differs from that of RAJAR, the differences seen here are comparable and similar to the differences in listening by ethnicity shown in RAJAR.

FREQUENCY OF RADIO LISTENING IN A TYPICAL WEEK, BY ETHNICITY

2.35 The research found that ethnic minority audiences are more likely to agree with the statement “I don’t think radio is for people like me” than White audiences.[footnote 35] The research also suggested that listeners from ethnic minorities feel that national stations in particular are less likely to cater for them and do not adequately represent them. In contrast, ethnic minority audiences over-index for listening to community radio, and non-UK based stations and pirate radio.[footnote 36]

2.36 The research showed that representation (along with relevant content) was a critical element in making radio more valuable to ethnic minority audiences.[footnote 37] Participants in the research noted that they felt unaware of existing ethnic minority talent and that more could be done to raise the profile of stations that featured such talent in a genuine way. There was an appreciation amongst ethnic minorities that radio is doing somewhat better than many other public spheres, such as politics and other areas of the media, to improve diversity, including the range of content, more diverse presenters on air, and a more representative workforce in the industry more broadly.[footnote 38] However, listeners still said that there remains much more work to do, and this was especially the case for younger audiences who expect a faster pace of change in all areas of diversity irrespective of their own background. These issues are discussed in more depth later in this chapter.

The role of audio in serving local audiences

2.37 In recent years, listening to UK-wide radio stations has grown, to some extent at the expense of listening to local and regional stations. A large number of new national commercial stations have launched on DAB, giving live radio listeners much more choice. The main commercial groups have networked services into larger editorial areas, which has allowed investment into content but at the expense of some local content (the exception being local news). At the same time, online and, in particular, social media is delivering local and hyperlocal content which was once a key selling point for local radio.

2.38 Nevertheless, research shows that listeners continue to value local news and information on BBC and commercial local radio. 27% of weekly radio listeners say they value local news on radio, increasing to 39% of those who listen to local radio.[footnote 39] Between them, the commercial local stations and the BBC’s local and Nations’ stations still accounted for 31.8% of all radio listening at the start of 2020, with the BBC stations reaching 7.8 million listeners a week and commercial local stations 25.2 million.[footnote 40]

2.39 Commercial radio services range in the size of area they cover from small rural stations such as Radio Skye which covers c6,000 people, through town and county-sized stations such as Sun FM (Sunderland) to regional stations such as Wave 105 (South Coast). The services include a mixed model with many providing local output throughout the day including local news and information, while others provide national networks presented by well-known national talent, within which local news and information is embedded.

2.40 The BBC provides 39 local services in England, collectively covering the whole of England (generally at a county level), and national services in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, including separate services in Welsh and Gaelic. The stations provide news, sport, information and debate at a local level along with connection to local stories and communities through a mix of speech and music.

2.41 Ofcom’s development of small-scale DAB, which provides a low-cost route to digital broadcasting for small independent commercial and community stations, will further strengthen the provision of local content and increase listener choice through a range of innovative and diverse services. Ofcom is in the process of the UK-wide roll out of the licensing regime for small-scale DAB, which will lead to the launch of over 200 new hyper-local multiplexes offering potentially thousands of services.

Small-scale DAB

Radio is undergoing a quiet revolution. The UK’s digital radio platform is being opened up to more and more smaller stations allowing new stations to be established and internet-only stations to make the move to the digital radio platform. The technology for small-scale DAB was first piloted in 2013 and later trialled by Ofcom between 2015 and 2018 in 10 locations across the UK. The trials, involving around 140 different small stations, showed the feasibility of new low cost approaches to digital radio distribution.

Following a successful Private Members’ Bill, the government introduced regulations allowing Ofcom to license new small-scale multiplex areas covering smaller geographical areas and giving the smallest commercial stations as well as community radio the option of broadcasting on DAB. By the end of July 2021, Ofcom had awarded 25 small scale multiplex licences, with plans to roll out many new areas over the next 3-4 years.

2.42 The appetite for hyper-local content can be seen in the strong and growing community radio offer across the UK. There are now more than 300 community radio services across the UK (including over 40 specifically serving ethnic minority communities). Community radio stations typically cover a small geographical area with a coverage radius of up to 5km (3 miles). Services offer a diverse range of output targeting many different audiences, some with a geographic focus on a particular community, others on a particular segment of their community such as young people or the LGBT community, those of particular religious or ethnic groups, or those with particular interests such as education or the arts.

2.43 Recently the BBC has begun to work more with community radio with the sharing of news content during the pandemic and a range of experimental creative initiatives which may lead to a longer term collaboration between public service and community radio to help strengthen radio at a local level. The BBC’s Annual Plan included a commitment to explore ways to collaborate further with community radio.

2.44 To better understand the value and role of community radio, the Review undertook a study of community radio listening across the UK, consisting of quantitative research to provide insights into community radio audiences and an audience measurement project using existing RAJAR data to derive an estimate of reach for all community radio stations combined. This analysis indicates that:

-

Around 1 million (2%) adults 15+ in the UK population listen to community radio in an average week.[footnote 41]

-

Community radio is particularly effective at reaching audiences who are proportionately less well represented in the All Radio audience - especially C2DE listeners and those from a Black or Asian background.[footnote 42]

Full details of this analysis have been published alongside this report.

2.45 Alongside the RAJAR analysis, in February 2021, research was undertaken to explore the relationship that listeners have with their community radio stations and to provide insights into the value and needs being fulfilled by community radio for its audience.[footnote 43] The survey results underline the deep connection that listeners have with their community station. Having the ability to hear very local news is a valued attribute of community radio, especially in areas where there is no other local station, or if nearby stations cover wider areas. In some places, the absence of a local newspaper means community radio may be the only source of regular local news updates. Respondents specifically mentioned the way their community radio station provided practical and emotional support during the COVID-19 pandemic. The full results of this research are published alongside this Report.

Helping the radio and audio industry to serve all audiences

2.46 Having examined listeners and their attitudes to and requirements from radio and audio, the Review looked in more detail at those factors which could help the industry to thrive and prosper, delivering content which audiences value. This includes a range of factors which could enhance the listener experience, covering how content is produced, delivering the best regulatory framework to allow the acceleration of content innovation, and opening new pathways into the industry for the widest talent pool to influence the future. The development of digital radio has allowed for a broader range of national services, including services targeted at specific audiences such as Asian and Christian communities. The emergence of small-scale DAB, along with community radio, means there is a growing degree of diversity and choice of radio services, especially in urban areas. Stations such as KISS Fresh, Capital XTRA and BBC Radio 1Xtra have also provided a way into music and radio for new presenters with new ideas, helping to drive new music trends in the UK. These developments provide a basis to further encourage efforts to promote new services which can reach a broader range of listeners.

2.47 The analysis provided by Mediatique suggests that, while listeners’ habits will continue to change as listeners discover new forms of content and new ways to listen on new digital devices and platforms, broadcast platforms and traditional radio devices will remain important, with many listeners continuing to listen to live radio content via broadcast networks. At the moment FM still has a significant share and is projected to decline only slowly between now and 2030. FM will continue to be a vital platform for listeners for the rest of the decade.

2.48 The focus - as distribution moves to a hybrid DAB/IP future - needs to be on supporting investment and innovation in content and making that content available to the widest audiences, however they are listening. Giving priority to innovating in content, formats and presentation will help to give UK radio the best chance of remaining vital and relevant. There are also opportunities for the UK audio production sector as a whole to develop further to meet the growing demand - particularly from younger audiences and internationally - for varied audio content that relates to life in the UK as it is today, and to capitalise on the UK’s growing audio production base in the light of strong international demand for English language content.

2.49 There are four areas where a combination of government support and cross-industry attention would help to support broadcasters and content creators to further invest in strengthening the overall mix of content available from radio stations and audio producers:

-

A renewed focus by government to reduce regulatory burdens on commercial radio by bringing forward, as soon as possible, legislation as set out in its response to the government’s consultation on radio deregulation in December 2017 and make changes to the restrictive rules on terms and conditions that have specific impacts and opportunity costs for commercial radio

-

Continuing support from government and Ofcom for the development of hyper-local services to complement the existing networks of local commercial and community radio

-

Collective work by government and industry to support the development of the wider audio sector, including the consideration of tax relief to help UK producers take advantage of future growth opportunities and further action on skills and training to open radio and audio to more diverse talent and voices

-

More attention by industry to developing cross-industry initiatives to create content and services to better reflect and appeal to the UK’s diverse audiences - this means a strong commitment across the industry to tackle barriers and bring on talent from ethnic minorities in particular, both in terms of content and in the workplace

2.50 There is also an emerging issue about the regulatory environment around music copyright as UK radio broadcasters and audio producers evolve services to meet the needs of listeners with the shift of listening to IP-based platforms. The UK radio industry has for many years been a significant partner for music talent, labels, writing, and performance and events in the UK. By showcasing, nurturing and promoting new music and helping to develop new talent, UK radio has enjoyed a valuable and mutually beneficial synergy with the various elements of the UK music industry. UK radio contributions to music (through fees paid by the sector) are agreed by the BBC and commercial radio with the major UK collecting societies through scheme-based sector arrangements. There are well established principles that recognise the role of radio, the difference to music streaming and the need to treat radio in the same way across all platforms.[footnote 44]

2.51 As mentioned elsewhere in the Review, UK radio’s future success will be dependent on the sector innovating and investing significantly in talent, content, technology and brands in order to compete with the larger technology platforms. It is important that this innovation, especially into new areas of IP-based delivery, is supported and enabled by a fair and transparent music licensing regime. The Review therefore recommends that the sector tracks progress and challenges around this and provides an update report to DCMS on this issue by the end of 2022.

Reducing regulatory burdens

2.52 Radio is probably the most regulated part of UK media. Radio consistently scores as a trustworthy part of UK media according to various UK and international studies.[footnote 45] The structure of UK regulations, based on Ofcom licensing and content regulation, helps support this trust. However, the changing landscape for UK radio with increased competition means it is important that the regulatory structure keeps pace with these changes and is set in a way which encourages commercial organisations to invest in new content and services whilst still ensuring the availability of local news, which matters to audiences. It is also important to ensure the BBC has the right framework so it can evolve its offer to deliver value to all audiences in the context of the changing media environment and especially the shift to IP consumption.

2.53 The current structure still retains requirements relating to the format of content and how commercial radio services are organised with changes requiring approval from Ofcom. In February 2017 the government consulted on a wide package of changes, which were strongly welcomed by commercial radio broadcasters. The government set out its proposals in response to the consultation in December 2017. In order to create the environment for more investment in content, the government should bring forward plans to legislate in the forthcoming Media White Paper announced by the government in June 2021.[footnote 46]

2.54 The radio sector is also disproportionately affected by the existing rules relating to financial service advertisements for products that mention the cost of credit. In particular, the current regime requires a significant amount of time - often around a quarter of the length of the advert - to be taken up by complex terms and conditions. This is costly to the industry, off-putting for advertisers, and confusing for listeners. To address this, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) should consider putting in place a new, simpler regime that reflects the particular characteristics of radio and audio, while maintaining consumer protection.

Incentivising new local services

2.55 The recent growth of new DAB-only commercial stations and community stations has the potential to strengthen the range and diversity of radio and audio services. These services are valued by communities and have proved their worth (both individually and collectively) during the COVID-19 pandemic. The development of small-scale DAB opens up the opportunity of increasing the number of small local stations adding greatly to listener choice and plurality. As research carried out for the Review shows, community radio reaches around 1 million people each week and makes a considerable impact to the communities served, not least as a means of bringing together and communicating with different local community groups.

2.56 The BBC, as noted in its ‘Across the UK’ announcement,[footnote 47] remains committed to local radio as a core part of its public radio offer, and during the pandemic has been sharing news content and working on a range of collaborations with community radio stations, as referenced previously in paragraph 2.43, to support radio at a local level.

2.57 To maximise these benefits the government may want to consider extending support for community radio - for example by expanding the Community Radio Fund - and consider whether a new local news fund for radio might help to strengthen small local commercial and community stations. The Community Media Association has highlighted that the current funding - £400,000 per year - is actually £100,000 less than the size of the fund at its launch in 2005/6, when there were far fewer community stations on air, and that an increase in the level of funding would help support the new community digital radio stations that Ofcom is starting to license.

2.58 Finally, there could also be merit in the government working together with the commercial and community radio sectors to ensure that smaller stations benefit from being able to use their reach into communities to support targeted public information campaigns. The Cabinet Office’s BAME Radio Partnership, which began in the summer of 2020, has been a successful example of engagement and cooperation to increase the visibility and impact of campaigns.

BAME COVID-19 Radio Partnership

During the COVID-19 pandemic, as part of endeavours to ensure that people across the UK were receiving clear and accurate information, the Cabinet Office and its external partner Omnigov set up a partnership with 12 multicultural radio stations with a combined reach of around 900,000 people.

Through a programme of co-creation with each station, a series of campaigns were targeted at hard to reach audiences, while working in a partnership enabled work to be carried out at scale, and with the flexibility to deliver multiple messages over a short period of time.

Supporting the growth and development of independent audio production

2.59 A change to the UK content landscape over the past 10-15 years has been the development of the UK’s independent audio production sector. This creative sector is made up of SMEs based all around the UK, creating a wide range of audio-led content including radio programmes, podcasts and audiobooks. There is also a lively freelance community producing podcasts alongside working with larger production companies.

2.60 The sector has grown its work with the BBC, due first to a 10% voluntary quota established in 1990, then an additional 10% Window of Creative Competition created as a result of the 2010 BBC Trust Review into radio programme supply. Following this, as a result of discussions between the Radio Independents Group (now AudioUK) and the BBC it was decided, as part of the BBC’s overall ‘Compete or Compare’ strategy, to increase the amount of relevant radio hours available to be competed for by external producers to 60% by the end of 2022. This is written into the current BBC Agreement.

2.61 The BBC is proceeding towards this target, reaching 53% in its latest annual report.[footnote 48] Current proportions of eligible hours awarded to independent producers average out at 25.9% across all the BBC’s UK-wide analogue and DAB networks.[footnote 49] BBC Sounds is also using the 60% figure for contestability in its podcasting commissions.[footnote 50]

2.62 The Audio Content Fund (ACF) has created new partnerships between commercial and community radio and the independent production sector. The first six rounds of the fund, plus additional COVID-19 and loneliness rounds, have resulted in 115 projects from 73 production companies, broadcast on 320 stations. A survey by the Audio Content Fund of the successful bidding companies produced figures showing that ACF projects had created or supported a total of 4,301 freelancer days plus 28 full-time jobs and 141 part-time jobs. 27 of the companies said that winning an ACF commission had assisted them to win additional work elsewhere. The benefits to audiences was also clear, as the ACF has provided them with a range of innovative and high-quality PSB programmes on their chosen stations.

2.63 The opening up of some BBC radio commissioning and the advent of the Audio Content Fund has coincided with the growth of demand for audiobooks and podcasting content, which is creating new opportunities for audio content creators. The result has been an increase in UK audio production businesses and the value of the sector as a whole. This value has increased with the rise of new digital formats such as podcasts and audiobooks which the UK, with its already well-developed production sector, has been in a good position to enter into from the start.

Podcasting

Podcasts are digital recordings of broadcasts or pre-recorded audio content that is available via the internet for downloading or streaming to a computer, smartphone or other connected audio device. Podcasts are widely available from broadcasters’ own sites or audio providers such as Spotify, Acast, Apple and Amazon Music, and from specialist providers such as Buzzsprout, Podbean, Transistor, Simplecast, Audioboom and Spreaker.

Podcast content continues to grow in popularity with RAJAR’s Spring 2020 MIDAS data reporting around 10 million weekly listeners (18% of adults) with 32% of podcast listening taking place whilst driving/travelling.(ref1) Ofcom’s 2021 Podcast Survey(ref2) suggested that numbers of regular podcast listeners may be higher, finding that 25% of adults were regular podcast listeners.

According to RAJAR MIDAS Spring 2020:

-

79% of podcast/download listening hours happen on a smartphone

-

44% of podcast listeners listen when driving/travelling, and 34% when relaxing

-

65% of podcast listeners listen to the entire audio episode, and 68% listen to all/most of the episodes they download

-

92% of podcast sessions are a solo activity

The growth of podcast listening may have slowed due to the impact of COVID-19 lockdowns on travel to work patterns and the resulting changes in listening behaviour.(ref3) Nevertheless, eMarketeer is predicting that the number of listeners will grow to 16m by 2024.(ref4)

Ref1: RAJAR MIDAS Spring 2020

Ref2: Ofcom Podcast Survey 2021

Ref3: Ofcom Media Nations 2021, p77

Ref4: Emarketeer How the pandemic affected our UK digital audio listener forecast

2.64 In the UK, podcast advertising revenues amounted to £33.56m in 2020, and by 2024 is forecast to reach almost £75m annually.[footnote 51] This figure excludes significant investment in UK podcasting by the BBC. Meanwhile, in the US the podcast ad market has been valued at around £560m in 2020.[footnote 52]