ACMD Drug misuse prevention review (accessible)

Updated 18 May 2022

ACMD

Chair: Prof Owen Bowden-Jones

Prevention Working Group Secretary: Sara Babahami & Nimshi Mahamalimage

1st Floor, Peel Building

2 Marsham Street

London

SW1P 4DF

Rt Hon Kit Malthouse MP

Minister of State for Crime, Policing and Justice

2 Marsham Street

London, SW1P 4DF

16th May 2022

Dear Minister,

Re: Drug Misuse Prevention Review

We are pleased to enclose the report of the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) on prevention of drug misuse in vulnerable groups. The ACMD was commissioned in December 2021, following the publication of the Drug Strategy 2021, and this report builds upon previous ACMD advice on prevention and vulnerabilities and substance use. The commission sought advice on preventing drug use among vulnerable groups of people, and how those groups can be prevented both from first using and from developing dependence on drugs.

An ACMD Working Group was established at pace, comprising of national and international experts in the field of drug misuse prevention. The working group applied its extensive expertise alongside a set of gold standard evidence reviews to develop its advice.

This report explores:

-

the factors that contribute to vulnerability;

-

general principles and specific approaches to prevention that are supported by the available evidence;

-

the need for the delivery of interventions to be embedded properly in the wider system and context if their potential is to be achieved.

Among the conclusions in the report, the ACMD found:

-

A sole focus on vulnerable ‘groups’ will limit the reach of prevention activities; rather, prevention should be targeted also at the risk factors, contexts, and behaviours that make individuals vulnerable. Strategies to reduce vulnerability must also target structural and social determinants of health, well-being and drug use.

-

Despite reasonably good evidence of ‘what works’, the UK lacks a functioning drug prevention system, with workforce competency a key failing in current provision.

-

There is no ‘silver bullet’ that will address the problems of vulnerability to drug use. Improving resilience will require significant, long-term public investment to rebuild prevention infrastructure and coordination of the whole range of services that can be harnessed proactively to increase the likelihood of healthy development of children and young people across a range of domains, including efforts to address inequalities, social capital, and social norms.

The ACMD has made the following recommendations:

Recommendation 1

The ACMD endorses the selective prevention activities recommended by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) ‘International Standards’ for drug use prevention (UNODC & WHO, 2018) and the indicated prevention activities recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017a). These should be the starting point for selective/indicated prevention activities delivered under the auspices of the government’s drug strategy and their development, organisation and delivery should reflect the European Drug Prevention Quality Standards (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011).

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit (JCDU)

Measure of impact: Evidence that guidance and policy issued by government departments reflects the above advice.

Recommendation 2

ACMD’s strong advice is that drug prevention activities that have been ineffective, such as fear arousal approaches (including ‘scared straight’ approaches) or stand-alone mass media campaigns, should not be pursued or supported; funding for these would be better used elsewhere. Where the effectiveness of an intervention has not been demonstrated or is uncertain, its implementation should only be regarding properly resourced, methodologically robust, rigorous, peer-reviewed, evaluative research. National policy and guidance should reflect this advice, e.g., regarding drugs education, and in guidance to organisations tasked with implementing prevention at the local level.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Evidence that guidance and policy issued by government departments reflect the above advice.

Recommendation 3

There is a dearth of evidence relating to prevention approaches for adult populations. There is a pressing need to improve understanding of adult vulnerability to drug use and to develop effective prevention approaches suitable to the circumstances of vulnerable adults. Resources for research to support this should be identified within the cross-government innovation fund announced within the drugs strategy.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Call for research in this area to be issued, utilising resources within the cross-government innovation fund.

Recommendation 4

The UK should aim for a strategy in which universal, selective, and indicated prevention approaches are integrated across policy in a ‘whole system’ approach. There is a need to invest in workforce training to ensure that the professionals within the ‘whole system’ are equipped to respond appropriately to those who are vulnerable. This will require work to encourage the relevant professional bodies to embed prevention learning within their accredited training schemes, at qualifying and post-qualifying stages, including continuing professional development. This might be addressed by developing, for example, suitable central online training resources to supplement mandatory pre and post qualifying prevention training. This will need to be mandated and monitored given the failure of previous curriculum guidance for social and health care qualifying education.

Lead organisations: Joint Combating Drugs Unit, Department for Education (DfE), Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)

Measure of impact: The setting up and reporting of a joint working group involving JCDU, DfE, DHSC, professional bodies and prevention experts to investigate the development of curriculum content and supplementary training resources, to be embedded in accredited schemes.

Recommendation 5

A focus solely on ‘vulnerable groups’ will limit the reach of prevention activities and contribute to stigmatisation and discrimination, thus it is potentially counterproductive. Rather, government policy, advice and guidance should refer to vulnerable people, acknowledging the dynamic, complex and individual nature of vulnerability, reflecting the importance of characteristics, behaviours and contexts, including the significant influence of structural, environmental and social determinants of well-being.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Evidence of advice, guidance and policy having been issued by government departments reflecting the above advice.

We look forward to discussing the enclosed report with you ahead of its presentation at the forthcoming UK Drugs Summit.

Yours sincerely,

Professor Owen Bowden-Jones, Chair of ACMD

Professor Tim Millar, Chair of ACMD’s Prevention Working Group

May 2022

1. Introduction

1.1. The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) has produced this report in response to a ministerial commission to “provide advice on preventing drug use among vulnerable groups of people, and how those groups can be prevented both from first using and from developing dependence on drugs” (Home Office, 2021) in support of the government’s ten-year drugs strategy, published in December 2021.

1.2. A Working Group comprising ACMD members and co-opted national and international experts in the field of prevention volunteered their time and expertise to undertake this review (see Appendix B for details of Working Group members).

1.3. The commission for this report requested the ACMD’s advice to be available by Spring 2022. It was necessary to work at a considerable pace to meet this request and to take a pragmatic approach to the production of the report. Time constraints did not permit a new review of the literature in this area. Rather, the Working Group has used its extensive expertise alongside a set of available ‘gold standard’ evidence reviews to develop its advice. Also, this report has built on several recent ACMD reports in this area, synthesising the available evidence to produce an overview of what is currently supported and identified where the gaps in the research lie.

1.4. The report first explores the factors that contribute to vulnerability; this was considered to be essential background to understand how prevention may operate. The report then explores general principles and specific approaches to prevention that the available evidence supports. Finally, the report considers the need for the delivery of interventions to be embedded properly in the wider system and context if their potential is to be achieved.

1.5. Note that the commission for this report requests advice regarding prevention of drug use and, where appropriate, the terminology used in the report reflects this. However, readers should note that much of the available literature and guidance is concerned with substance use prevention in the wider sense, including psychoactive drugs (hereafter ‘drugs’), alcohol and tobacco use. Moreover, early use of alcohol and /or tobacco may be risk factors for other psychoactive drug use and use of these is associated with harm. Therefore, this report suggests that prevention, particularly for children and young people, should consider substance use in the wider sense.

2. Vulnerability

Framing vulnerability and resilience

2.1. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) frame vulnerability /resilience in the following terms:

“…. psychological and emotional well-being, personal and social competence, a strong attachment to caring and effective parents, attachment to schools and communities that are well organized and have enough appropriate resources are all factors that contribute to making young people less vulnerable to substance use and other risky behaviours.” (UNODC & WHO, 2018; page 2)

2.2. In a previous report the ACMD (2018) considered the question “what are the risk factors that make people susceptible to substance use problems and harm?”. The advice offered by that report still pertains. The following section is largely a synopsis of that report, augmented to address the focus of the current commission, and refined where appropriate. This report does not include the supporting evidence base in ACMD’s earlier report.

2.3. There is a large body of work that has considered the characteristics that are associated with the risk of developing drug /substance use problems and of experiencing drug /substance-related harm (both hereafter called ‘harm’), and the factors that may be protective against harm (ACMD, 2018).

2.4. Many of those who experiment with or use drugs do so without experiencing significant harm. Where harm does arise, it may do so because of the type of drug used (including the forms, routes of administration, amount consumed, context of use, and adulterants), the user’s individual characteristics (including genetic factors, mental, physical and social morbidities), and is significantly influenced by the wider context in which they use drugs. The latter includes policy and practice responses to drug use, social /socioeconomic factors, environmental factors (such as neighbourhood features that may encourage or discourage drug use), and structural factors (such as adequate access to education, employment and recreation). The interplay between these factors influences both the likelihood of an individual experiencing harm and the seriousness of that harm.

2.5. Some people may be at greater risk of harm than others because of the specific set of risk factors they experience, i.e., they are potentially more ‘vulnerable’. However, the relationship between risk factors and consequent harm is not deterministic, despite their exposure to risk, sufficient protective factors may increase some people’s resilience to harm.

2.6. Vulnerability, resilience, and the consequent harms that may arise from drug use are a manifestation of risk and /or protective factors that often are interrelated and that exert their influence at different levels (which may overlap) and at different stages of human development. For example:

-

Individual: e.g., personality, mental health /well-being, health /disability, trauma, experience of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), employment /educational /housing /economic status and genetics.

-

Interpersonal: e.g., prosocial relationships, peer influences and norms, family structure and functioning.

-

Community: e.g., ease of access to drugs, economic and housing opportunity, marginalisation and social isolation /cohesion.

-

Institutional: e.g., accessibility of drug use services and generic helping services, exclusion, and discrimination.

-

Policy: e.g., housing, employment, education, health and social policy and drugs legislation.

-

Macro social system: e.g., population mobility and social inequality.

2.7. Many of the factors that make some people vulnerable (or, conversely, resilient) are, to a great extent, beyond their personal control, constraining the behavioural choices and opportunities that are available to them: “…marginalized youth in poor communities with little or no family support and limited access to education in school are especially at risk” (UNODC & WHO, 2018; page 3). Moreover, while interventions have generally been targeted at individual-level factors, the greatest long-term impact is likely to be achieved by addressing the widest set of factors that foster vulnerability and impede resilience.

2.8. Persistent, systematic, multiple-factor deprivation is a key driver of negative health outcomes. Similarly, drug-related harm is strongly associated with socioeconomic position and social exclusion; harm is greater amongst those who live in economically deprived areas and those with lower individual and socioeconomic resources.

2.9. ACEs are events or circumstances in childhood that produce chronic stress responses. People with ACEs, and especially those with cumulative, multiple ACEs, may warrant particular attention as key risk factors in the trajectory towards vulnerability to drug /substance use. The effect of ACEs may cluster in areas of, or be exacerbated by, socioeconomic disadvantage and their impact may be inter-generational. However, the literature in this area is rather limited, and although it supports a relationship between ACEs and drug /substance use dependency in later life, further work is required to unpick the exact nature of, and factors that may mediate that relationship (Leza et al., 2021).

2.10. Parents /guardians substantially influence the development of their children. This arises through a range of factors including (epi-) genetics, environment, child-rearing practices and relationship quality (Hettema et al., 2005; Kendler et al., 2003). When there is adversity in childhood, several mechanisms may come into play, resulting in an observed association with vulnerability in children that has a long-lasting impact. In England, an estimated 2.3 million children live in risky home situations (Children’s Commissioner, 2021), including 478,000 children living with a parent /guardian who is experiencing problems with alcohol or drugs- a rate of 40 in 1000 children (Children’s Commissioner, 2020)- and 80,850 children in local authority care (Department for Education, 2021a). These children are vulnerable to drug use and related problems, with children who experience multiple adversity being ten times more likely to use drugs than those with no exposure to adversity (Hughes et al., 2017).

2.11. There is a large evidence base showing significant association between parental substance use disorder /dependence and children’s substance use (Cranford et al., 2010; Haugland et al., 2012; Haugland et al., 2013; Haugland et al., 2015; Jennison, 2014; Keeley et al., 2015; Kendler et al., 2013; Lieb et al., 2002; Shorey et al., 2013), with similar effect sizes being reported for both parents substance dependency (Malone et al., 2002; Malone et al., 2010; Korhonen et al., 2008).

‘Vulnerable groups’

2.12. Previous work has identified specific groups in which vulnerability to drug use may be more common. However, the model of ‘vulnerable groups’ may be an observational artefact, whereby we observe accumulated problems among certain groups and then ascribe vulnerability to members. Whereas the aetiological pathways to vulnerability are likely to be complex and operate at multiple developmental levels, from early /middle childhood onwards, and influenced by a range of characteristics, circumstances and experiences (as above). This would warrant earlier preventive interventions, but not necessarily aimed at the vulnerable groups, per se, which might be merely the observable endpoints of a suboptimal socialisation (analogous to the tip of a developmental iceberg).

2.13. It is important to recognise that vulnerability is dynamic, not a fixed characteristic. It may be heightened at key developmental stages (such as in infancy and early childhood and at the transition from childhood to adolescence) or during certain transitions or life events such as moving in /out of local authority care, prisons or secure settings, becoming homeless, moving between educational levels (i.e., from primary to secondary school, from secondary school to university) moving from the parental home, ending a relationship /divorce and becoming unemployed (UNODC & WHO, 2018). In this sense, vulnerability can shift depending on an individual’s circumstances.

2.14. Additionally, it is important to emphasise that identification of a specific group as vulnerable is, in part, a function of whether research has examined the needs of that group, i.e., we only find vulnerability in the places that we look for it. Notwithstanding that research has identified specific characteristics and circumstances that are associated with a higher risk of initiating drug use, others, whose needs have not been so thoroughly investigated, may be equally or more associated with vulnerability.

2.15. Labelling of /identifying vulnerable groups, together with contexts and behaviours associated with vulnerability, may be useful in prioritising resources, and in ensuring that we do not discriminate against designated groups. However, it should be noted that a focus solely on the characteristics of specific groups is likely to add to stigma and will obscure individuals’ unique differences in need and vulnerability. Moreover, it is essential to recognise that: vulnerability possibly associated with a specific group or characteristic does not automatically confer vulnerability on an individual who is a member of that group or shares that characteristic; not all of those who are vulnerable will go on to use drugs; and that drug use of vulnerable individuals will not necessarily escalate to a harmful level.

2.16. As described above, a sole focus on ‘vulnerable groups’ will limit the reach of prevention activities and can contribute to stigma and discrimination. A more effective approach would also consider risk factors, contexts and behaviours which may make individuals vulnerable to drug use. Strategies to reduce vulnerability must also target structural and social determinants of health and well-being / drug use, such as deprivation, disadvantage, social exclusion and adequate access to education, employment and recreation.

Prevalence of drug use among those with potential vulnerabilities

2.17. There is no single source to support a robust assessment of the UK prevalence of drug misuse amongst groups that share characteristics or circumstances potentially associated with vulnerability, which enables comparisons with prevalence in the wider population. It was beyond the resources available to the Working Group to undertake a proper review of the wider literature pertaining to this; in any case, that literature is likely to use disparate methodologies and definitions, that would present obstacles to providing a coherent, succinct summary, and international studies cannot be robustly generalised to the UK situation.

2.18. However, there are two sources (Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) and the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS)) that shed some light on the prevalence of drug use amongst some population groups, compared to others, and the prevalence of vulnerabilities amongst those whose drug use leads them to seek treatment.

2.19. The CSEW is a household survey of people aged 16 years and over and includes a component relating to drug use. The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the survey for the year ending 31 March 2021, but CSEW implemented a shortened telephone version. The sample was restricted to those aged over 19 years, but this provides some helpful insights into the association in adults. Based on this source, the observed prevalence of past year use (April 2020 to March 2021) of any drug was (ONS, 2022):

-

Higher among those unemployed (12.2%) than those economically inactive (7.9%) or employed (5.8%).

-

Higher among those who identified as bisexual (11.1%) than those identifying as gay/lesbian (8.8%) or heterosexual (6.5%).

-

Higher among those with a disability (8.6%) than among those without (6.1%).

-

Higher amongst those in financial difficulty (12.8%) than those financially stable (6.7%).

-

Lowest amongst those living in the least deprived areas.

-

Higher amongst those who had experienced violence (14.3%) than those who had not (6.3%).

2.20. Additionally, based on CSEW for year ending March 2020, the observed prevalence of past year use of any drug was (ONS, 2020):

-

Highest amongst those with the lowest household income.

-

Higher amongst those with lower life satisfaction (23%) than for those with medium (13.2%), high (11.7%), or very high (4.8%) life satisfaction.

-

The same pattern for people’s feelings of happiness.

2.21. Note that the simple comparisons, above, do not enable conclusions regarding the independent association of specific characteristics with drug use. For example, analysis that adjusted for factors such as age, sex and financial difficulty, (ONS, 2022) - found no statistically significant independent association between having experienced violence and past year drug use, despite the large observed difference in prevalence (similar analysis was not published for the other factors listed above). This suggests that the apparent association arose by virtue of a set of other, co-occurring factors /circumstances. Moreover, an observed association between a particular characteristic and drug use does not permit inferences to be drawn regarding the direction, or even the existence, of any causal effect, so we cannot conclude that one causes the other, but merely that they co-occur.

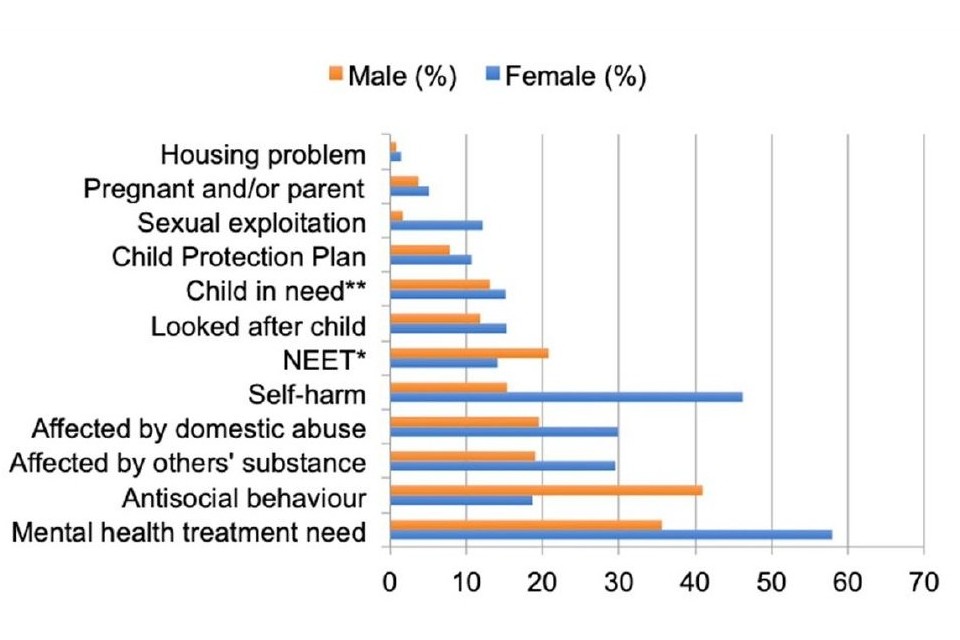

Figure 1: Vulnerabilities reported by persons under 18 presenting for substance use treatment in England, year ending March 2021

*NEET includes young people who have been permanently excluded from school or who are not in education.

** Child in need as defined under section 17 (10) of The Children Act 1989

2.22. Figure 1 shows the proportion of persons under 18 who started treatment for substance (drugs and /or alcohol) use in England during the year ending March 2021 who experienced factors that may confer vulnerability, as recorded by the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System[footnote 1] (OHID, 2022). 23% of young people who started treatment exhibited at least one of these vulnerabilities, 23% two, 16% three, and 20% four or more (figures provided by the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID)). The extent of vulnerability in this group has not been compared here to that in the equivalent general population, but it is apparent that there are high levels of potential vulnerability in this treatment-seeking group. Note that substance use amongst vulnerable young people may be more likely to come to official attention than substance use amongst their non-vulnerable peers, because of their contact with helping services, so they are more likely to be referred into treatment (almost a quarter of young people were referred to treatment via children and family services).

3. Prevention

3.1. This section includes some general considerations regarding prevention and the evidence base that supports it, highlights the potentially disproportionate benefits of universal prevention for vulnerable individuals, and describes selective and indicated approaches to intervention for which there is evidence of ‘what works’.

3.2. This section of the report draws particularly from guidance provided by the UNODC & WHO (2018), previous advice from the ACMD (2015) and recommendations from the NICE (2017a).

General considerations for prevention activities (children and young people):

3.3. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Health Organization describe prevention in the following terms:

“The overall aim of substance use prevention is… to ensure the healthy and safe development of children and youth …. Effective prevention contributes significantly to the positive engagement of children, youth and adults with their families and in their schools, workplaces and communities.” (UNODC & WHO, 2018)

3.4. Most of the supposed drug prevention ‘activities’ in use in the UK (and internationally) have not been evaluated sufficiently, so their effectiveness is unknown. However, there is evidence regarding ‘what works’, albeit that the range of activities judged to be effective is perhaps quite small, and there is evidence regarding what ‘does not work’ in drug prevention. Prevention is largely an unregulated field with an unregulated workforce, which typically has not received specific training in prevention (Ostaszewski et al., 2018). Concern has been expressed regarding the fidelity with which activities found to be effective in the research context are translated in practice, e.g., in school settings and student /parent programmes (Cuijpers, 2003; Newton et al., 2017). If those responsible for delivering, funding, and selecting prevention activity lack the skills to do so and do not adhere to the content of programmes and the underpinning principles of prevention that have been shown to be effective, then the implementation of ‘what works’ will not be optimal.

3.5. Because of a paucity of studies, it has not been possible to identify the active components necessary for interventions to exert a positive effect (UNODC & WHO, 2018). The latter also identifies publication bias as an issue; studies that report novel, positive findings are more likely to reach the public domain, while negative findings are less likely to be published, thus our view of ‘what works’ and how well it works is likely to be overly optimistic. Many interventions are not evaluated; those that have are often found to be ineffective, despite being widely used, and some have been shown to be counter-productive /harmful (they increase drug use or other risk behaviour). The latter highlights the potential danger inherent in commissioning untested approaches. Given there are not currently evidence-based interventions, in order to develop them, existing or new interventions will need to be tested and evaluated.

3.6. ACMD (2015) also highlighted that there is strong evidence of prevention activities that have consistently been ineffective at improving drug use outcomes, including: information provision (stand-alone school-based curricula designed only to increase knowledge about illegal drugs, rather than influence behaviour), fear arousal approaches (including ‘scared straight’ approaches), and stand-alone mass media campaigns (ACMD, 2015). The ACMD’s strong advice is that these activities should not be pursued or supported and that funding for these would be better used elsewhere. National policy should reflect this advice, e.g., regarding drugs education, and in guidance to organisations tasked with implementing prevention at the local level.

3.7. Where the effectiveness of an intervention is uncertain, its implementation should only be properly resourced, methodologically robust, rigorous, peer reviewed, evaluative research. Moreover, most research has considered the efficacy of prevention activities in well-controlled, small-scale settings (UNODC & WHO, 2018), but research also should explore whether the success of seemingly ‘effective’ interventions is replicated in real-world settings and routine practice, where the fidelity of implementation may be lacking.

3.8. The generalisability of prevention strategies is sometimes overstated. To illustrate, the Icelandic Prevention Model (IPM), that originated in 1980s research aiming to identify adolescent risk behaviour (Sigfusdottir et al., 2020), has received mounting enthusiasm internationally over the past decade or so. Although endorsed as a critical success that is ‘not unique to Iceland’ (Sigfusdottir et al., 2020) and being used in 32 countries worldwide, there were no published peer-reviewed papers evaluating its effectiveness outside Iceland (Koning et al., 2020). Others have noted that its impact must be considered in the context of Iceland’s strong alcohol and youth policy framework, which might not exist elsewhere (e.g., Koning et al., 2020), and that Icelandic cultural characteristics and political and environmental structures are critical ingredients of, or context for, any change in risk behaviours. For example, there may be higher acceptability of social control and support (e.g., by parents) in Iceland that might not apply in other countries. Koning et al., (2020) suggested that it is not yet possible to determine which elements are essential or might work well in other countries, limiting our understanding of the extent to which it is generalisable. Thus, without further evaluative work, we cannot assume that all interventions found to be effective elsewhere will necessarily be effective in the UK. This is not to dismiss the possibility that interventions shown to have promise elsewhere may transfer to the UK context, but this should not be assumed without prior, rigorous evaluation.

3.9. There are also difficulties in generalising between substances. A decade ago, the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA, 2010) observed that most universal drug prevention programs have addressed the more prevalent forms of drug /substance use (alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis) with much less attention given to low prevalence drugs. Twelve years later, this remains the case. It is important to recognise that such interventions may not transfer to lower prevalence drugs and indeed might contribute to unintended adverse outcomes (e.g., increased knowledge of, interest in and use of such drugs). There is a dearth of evidence supporting the assumption that, for example, an effective alcohol prevention approach will generalise to preventing heroin related harm.

3.10. Drug prevention activities commonly have been delivered as stand-alone interventions, focusing specifically on drug use. It is important to consider that many of the factors that contribute to vulnerability to drug use also are determinants of a range of risk behaviours, or un/healthy development (Blum et al., 2012; Patton et al., 2012; Viner et al., 2012; Arango et al., 2018). Evidence suggests that interventions targeting multiple behaviours are (cost) effective (e.g., Hale & Viner, 2012; Prochaska et al., 2008; Werch et al., 2010). Thus, these may be more efficient in modifying risk behaviours than a single focus on drug prevention. Parental engagement appears to be a critical element in the success of programs that target diverse behaviours (Mewton et al., 2018).

3.11. Interventions in other domains (e.g., prevention of mental health disorders, violence and bullying) might have relevance to drug use. Drug /substance use disorders and mental health disorders often coexist and many of the risk factors (exposure to childhood trauma, vulnerable and dysfunctional families, poor educational and community connectedness and engagement; intolerable environments) are common. So, strategies that are beneficial in one domain can have an impact in another – well-being and robust mental health are protective for alcohol and other drug use (e.g., see Arango et al., 2018). This is reflected in the approaches to drug prevention highlighted in the following sections as being effective; these promote healthy development and well-being, rather than use of drugs per se.

3.12. For some groups with multiple and intersecting vulnerabilities, research has shown that single interventions aimed at drug /substance use alone are not likely to be effective. For example, for drug experienced young people in contact with the criminal justice system, the ‘system’ of services and interventions was difficult to understand and navigate, and practitioners pointed to the need for integrated, holistic approaches to prevention activities, treatment and service provision (Gleeson et al., 2019; Duke et al., 2020; Frank et al., 2021). These holistic approaches would include substance use interventions, help for mental health problems and offending behaviour, as well as practical help with housing and education. Rather than a single intervention, these approaches require a system whereby agencies and organisations collaborate and work in partnership.

3.13. There is emerging evidence regarding the use of social /internet /digital platforms as a delivery mechanism for prevention activity, although this remains somewhat limited (Mewton et al., 2018). However, these approaches may hold promise insofar as they may be cost effective and provide less scope for divergence from the key components of the programme that they deliver than interventions delivered by an unskilled workforce.

3.14. Note that much prevention work focuses on the needs of children and young people, but there is remarkably little evidence of approaches that may be effective for vulnerable adults, as discussed in the following section.

General considerations for prevention activities (adults)

3.15. There is a dearth of evidence relating to prevention approaches for adult populations. Prevention among adults is more likely to focus on the prevention of harm from drug /substance use and, in particular, preventing harm from the escalation of use, although these are very important objectives. It may also apply to preventing the misuse of prescribed medication.

3.16. Key transitions in the life course, such as bereavement, social isolation, retirement and other personal and social changes in people’s lives, can provide a particular point of vulnerability to increased use of substances. However, they also provide a key opportunity for prevention:

“These transition points can provide an opportunity for intervention and support, but if left unresolved may make it more likely that there is a long-term change in substance use behaviours towards harmful outcomes.” (ACMD, 2018; p 25)

3.17. Traumatic experiences in childhood and adulthood can also affect adult substance use, as can social and health inequalities such as deprivation and multiple disadvantages. The ACMD’s previous reports in 2018 and 2019 highlighted these, and their conclusions and recommendations remain pertinent. It is beyond the remit of this Working Group to identify all the risk factors at individual and group level for adults’ increased use of substances across their adult life course. People will also fall into multiple ‘groups’ identified; for example, people who have experienced domestic abuse and have developed mental ill health and who may be in an older age category.

3.18. However, evidence showing increasing drug /substance related morbidity and mortality among older age cohorts reflects the ageing population in the UK and a group of people who need particular attention. In a Royal College of Psychiatrists report, Crome et al., (2018) summarised evidence that substance use by older people increased mortality rates and accelerated ageing and was often associated with mental ill health such as depression and anxiety. Prevention of harm and prevention of escalation of harm among older people will require attention to their specific needs and prevention, with intervention programmes tailored accordingly.

3.19. The other significant gap in the UK evidence base relates to the prevalence of drug use among people with learning difficulties and physical disabilities (including veterans). There is evidence from many other countries that drug /substance use among these groups of people is far higher than the general population (van Duijvenbode & VanDerNagel, 2019; Guimaraes et al., 2016) but the UK does not have an equivalent evidence base to support such claims. The first step in prevention work is to determine accurately the scale of concern. Prevention work can then be developed to counter the risk factors, develop the protective factors and build resilience.

Universal approaches to drug use prevention

3.20. Universal approaches to drug prevention are delivered irrespective of the level of risk of individuals or subgroups in the population that receives them. Although the commission for this report did not request consideration of universal approaches, such approaches may differentially benefit those who are most vulnerable.

3.21. For example, the ‘Good Behaviour Game’ (GBG) is an intervention applied to entire primary school classes during regular lessons that aims to enhance self-control, emphasising the role of being a student and significant others (teachers and peers) in children’s social adjustment in school. Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) report a beneficial impact up to the middle school years and even young adulthood, including reductions in alcohol and drug dependence disorders and a reduction in many other behavioural problems. The largest effects were found for children with the highest neuro-behavioural disinhibition at onset (Kellam et al., 2014), i.e., those with an individual characteristic that contributes to vulnerability derived the most benefit.

3.22. Similarly, evaluation of a universal programme targeting families, using a Dutch, school-based, multi-component programme designed to postpone onset of alcohol use found that the more vulnerable subgroups within the target population derived the most benefit (Koning et al., 2012).

3.23. Similar effects may be observed for environmental prevention approaches. For example, in a Canadian study (Zhao & Stockwell, 2017), minimum alcohol pricing was negatively associated with alcohol attributable hospitalisations; this effect was greater in low-income regions and inversely related to family income for some types of morbidity.

3.24. Interventions delivered during the early school years, that aim to improve educational environments and reduce social exclusion, also seem to have a moderating effect on later substance use (Toumbourou et al., 2007), without specifically targeting youths who experiment with drugs. Such prevention programs can also be beneficial in behavioural domains beyond substance use, such as violence, delinquency, academic failure, teenage pregnancies, and unprotected sex. Smoking, drinking, safe sex and healthy nutrition among adolescents share common factors- beliefs about immediate gratification and social advantages, peer norms, peer and parental modelling, and refusal of /low self-efficacy.

3.25. ACMD’s previous report on prevention highlighted that, while targeted, drug-specific prevention interventions are an approach for groups at high risk, these groups may derive more benefit than non-vulnerable groups from universal approaches. Research supports that universal drug prevention actions should be embedded in wider strategies that aim to support healthy development and well-being. ACMD suggested some promising approaches that are likely to be beneficial, such as pre-school family programmes, multi-sectoral programmes with multiple components (including the school and community) and some school programmes on skills-development (ACMD, 2015).

Selective approaches to prevention

3.26. Selective prevention intervenes with specific contexts, settings, risk behaviours, groups, families or communities that may be more likely to develop drug use or drug use disorders and /or dependence. As highlighted above, often this vulnerability to drug use stems from social exclusion, lack of opportunities, less nurturing family or community environments, and cultural and /or socially learned behaviours around substance use. This means that, in contrast to universal prevention, the situation and vulnerability of a target group must be studied before starting the invention, ideally regarding the views of the target population. Since this vulnerability assessment is at the group level, individual risk cannot be assessed. Much of the guidance in this area relates to children and young people rather than to vulnerable adults.

3.27. Selective approaches to prevention should, to a degree, be conceived and delivered as a proactive intervention because: i) they are directed at groups where vulnerability might be considered more likely to occur (e.g., people in deprived neighbourhoods); and ii) by fostering circumstances conducive to building up resilience, they might potentially ameliorate the effect of exposure to additional risk factors for people with individual vulnerabilities (e.g., children with neuro-behavioural disinhibition who live in deprived neighbourhoods). Also, as proactive interventions, they have potential to be delivered around key transitions in the lives and development of children and young people, which may be periods of particular risk. Moreover, because selective interventions are often designed to engender resilience in the broadest sense, they have the potential for a positive impact on a range of risky behaviours as well as on drug use.

3.28. Promising interventions in this field address social needs connected to drug use, rather than drug use behaviour, which in these populations is just one of several expressions of behavioural maladjustment. However, the ACMD (and others) advise that evidence for the effectiveness of selective prevention is currently limited because evaluations are difficult, of poor quality and are scarce.

3.29. Several researchers have raised concerns regarding possible iatrogenic effects when vulnerable young people come together in selective interventions (Dodge et al., 2006; Mager et al., 2005; Poulin et al., 2001). Problem behaviour may deteriorate when members of this selective group model other’s problem behaviour (‘deviance modelling’), thereby corroborating their belief that their behaviour is ‘normal’ while the surrounding social environment is not (‘norm narrowing’). Such iatrogenic effects are unlikely to occur in universal prevention.

Selective prevention: UNODC and WHO guidance

3.30. The UNODC and the WHO have produced International Standards for drug use prevention that feature very prominently in international prevention work (UNODC & WHO, 2018). These evidence reviews are based on an evidence gathering exercise that, notably, did not identify any systematic review of the evidence for selective interventions targeted at children and young people at high risk. No significant new evidence or thinking has emerged since the publication of these standards. Again, the UNODC and WHO standards are concerned primarily with children and young people.

3.31. The UNODC and WHO standards, developed by an international team including members of this ACMD Working Group, identify several selective approaches for which there is some evidence that they reduce drug use (UNODC & WHO, 2018). Note that several of these are family-based interventions and the EMCDDA’s European Prevention Curriculum provides further information regarding this type of intervention, along with school and workplace interventions, (EMCDDA, 2019a). The UNODC and WHO guidance is summarised below (interested readers are encouraged to read the full report):

-

Prenatal and infancy visits: targeted at groups living in difficult circumstances; delivered by trained health workers; involving regular visits up to age two; providing basic parenting skills; supporting mothers to address a range of socio-economic issues (health, housing, employment, etc).

-

Early childhood education: supporting social and cognitive development of pre-school children (2 to 5 years of age) from deprived communities; focused on children’s cognitive, social and language skills; conducted daily; delivered by trained teachers; providing family support on additional socioeconomic issues.

-

Parenting skills programmes: in middle childhood /early adolescence; designed to enhance family bonding; supporting parents to take an active role in children’s lives; demonstrating how to provide positive and appropriate discipline and how to be a role model; accessible; over a series of sessions; with activities for parents and children; delivered by trained individuals. Not: undermining parents’ authority; or only providing drug specific information to parents; or delivered by poorly trained staff.

-

Skills-based prevention programmes: in early adolescence; often universal but potentially focused on those at high risk (such as young people with mental health problems); provide interactive opportunities to develop and rehearse personal and social skills; focus on encouraging substance and peer refusal; using interactive methods; delivered over a series of sessions by trained facilitators; exploring risks of substance use; dispel views regarding substance use being a normative behaviour. Not interventions associated with no effect or iatrogenic effects such as: heavily information based; fear arousing; unstructured; focused solely on self-esteem /emotional education /ethical and moral decision-making; peer-delivered for high-risk groups; employing former users to describe their experience.

-

Mentoring programmes: in early adolescence; matching young people from marginalised situations with adults who engage them in activity and spend time with them; using adequately trained, properly supported mentors within a highly structured set of activities.

Indicated approaches to prevention

3.32. Indicated drug prevention encompasses interventions that are targeted specifically at individuals assessed as having increased vulnerability to drug use or drug harm. This is independent of current drug /substance use and might include, for example, children with externalising behaviours (e.g., ADHD, neuro-behavioural disinhibition). Unfortunately, these individuals may come to attention late because they have already started drug /substance use (although intervention may reduce the likelihood of escalation and /or target specific risks and harms, e.g., overdose or bloodborne infection). In the latter sense, indicated approaches (sometimes inaccurately referred to as ‘early intervention’) are reactive, because they address perceived ‘deficits’ in those individuals they consider to already to have developed vulnerability. It is notable that (as per following sections) relatively few indicated approaches to prevention have been shown to be effective.

Indicated prevention: guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

3.33. NICE has undertaken a review of the evidence for indicated prevention (which it refers to as targeted intervention for individuals assessed as vulnerable) that is likely to be effective “to prevent or delay harmful use of drugs in children, young people and adults who are most likely to start using drugs or who are already experimenting or using drugs occasionally” (NICE, 2017a - emphasis added). NICE is resourced to undertake comprehensive evidence reviews, which are of very high ‘gold standard’ quality.

3.34. The NICE review is relatively recent. After discussing whether significant new evidence or thinking has emerged since the publication of the review, it was considered this not the case. Thus, the findings of that review are highly pertinent, and represent the best and most up-to-date advice for the UK context.

3.35. The following provides a synopsis of the advice offered by NICE. This is intended as a brief guide; those responsible for implementing this advice should refer to the complete NICE recommendations.

3.36. Audience: The NICE guidance on targeted interventions for drug misuse prevention is designed for health /social care professionals, commissioners and providers, drug misuse prevention /specialist drug treatment practitioners, venues attended by people using /at risk of using drugs (e.g., gyms, pubs, clubs or music events), those responsible for educational governance, people who use drugs (and their carers and families) and the public.

3.37. Setting: NICE recommends that assessment and targeted prevention for people in at-risk groups should be embedded in existing statutory, voluntary or private services. This includes health services (including primary care /community-based /mental health /sexual and reproductive health /drug and alcohol /school nursing and health visiting services), specialist services for people in groups at risk, community-based criminal justice services (including adult, youth and family justice services) and accident and emergency services.

3.38. Assessment: NICE (2017b) suggests that it is “essential to have an assessment before intervention to ensure that the intervention offered is appropriate and no harm is done”. It is recommended that individuals attending services (as above) should be assessed regarding their vulnerability to drug misuse at routine or opportunistic contact. For example, at health assessments for looked after children, young people or care leavers; appointments with GPs, nurses, school nurses or health visitors; emergency department attendances due to alcohol or drug use; and contacts with community-based criminal justice agencies. NICE did not recommend a particular assessment tool.

3.39. Assessment approaches should be consistent, locally agreed, respectful and non-judgemental and proportionate to the person’s presenting vulnerabilities. They should consider: the individual’s circumstances (including drug use); whether there are immediate safety concerns; and the priorities of the individuals concerned. Where drug misuse already is apparent, responses should consider relevant NICE guidance on higher-level interventions.

3.40. Intervention (children and young people): for children and young people assessed as vulnerable, consider provision of skills training intervention, ensuring that carers or families also receive such training, noting that there may be specific circumstances where this is not appropriate (for older children and young people, NICE suggests that consideration is given to provision of information, as para 3.44. below, but this is unlikely to be effective in preventing drug use).

3.41. Skills training should be commissioned within existing services (as outlined in para 3.37 above), integrated with activities to increase resilience and reduce risk, and delivered by people who are competent.

3.42. Skills training should help to develop a range of personal and social skills such as listening, conflict resolution, refusal, identifying and managing stress, decision making, coping with criticism, dealing with feelings of exclusion and making healthy behaviour choices. For those who are looked after or care leavers, skills training should have specific emphasis on dealing with feelings of exclusion. When delivered to carers /families, it should help them develop skills in communication, develop and maintain healthy relationships, conflict resolution and problem solving. Training for foster carers should also involve the use of behaviour reinforcement strategies. The format, content and setting of training should consider the specific situation, needs and preferences of the individual.

3.43. Follow-up plans should be discussed and agreed during training, to assess whether additional skills training or referral to specialist services is required.

3.44. Intervention (adults): it is notable that NICE did not find evidence supporting indicated approaches that are effective in preventing initiation or escalation of drug use among adults. NICE recommended that adults assessed as vulnerable should be offered at the time of the assessment clear information on drugs and their effects, advice /feedback on their drug use (if present) and information on local advice /support services. This should be non-judgemental in line with other NICE guidelines, and tailored to the person’s preferences, needs and level of understanding. As above, follow-up plans should be discussed and agreed, to assess whether additional information or referral to specialist services is required. Information-only approaches are unlikely to be effective in preventing drug use; they may have value as a harm reduction intervention, but it is beyond the remit of this report to consider that function.

3.45. Intervention (people at risk of using drugs): the NICE guidance includes advice regarding people who might be at higher risk of using drugs because of their presence in particular settings. NICE suggests that information about drugs should be provided in settings attended by those who use or are at risk of using drugs. These might include nightclubs /festivals, wider health services, hostels /supported accommodation for people without permanent accommodation and gyms (regarding image- and performance- enhancing drugs). Information might be in various formats (e.g., web-based, written) and encompass drugs /their effects, local services, sources of advice and support, online self-assessment and feedback. It should conform with additional NICE guidelines on approaches to behaviour change, etc. As above, information-only approaches are unlikely to be effective in preventing drug use and related problems, although they may have value in targeted, specific harm reduction interventions.

3.46. Interventions not recommended by NICE: NICE considered the evidence for the effectiveness, cost effectiveness, and acceptability of a range of potential interventions. It concluded that the evidence did not support recommendation of the following for indicated prevention in the UK context:

-

personal and social skills training only for children and young people;

-

personal and social skills training only for carers /families;

-

family-based interventions as a whole;

-

manualised and licensed programmes for children /young people (the review included Focus on Families, Family Competence Program, Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care, Familias Unidas and Free Talk);

-

motivational interventions for children and young people or for adults (the review included motivational interviewing, brief interventions and motivational enhancement therapy);

-

skills training for adults.

3.47. Caveats: NICE highlighted several limitations to the evidence, notably that:

-

evidence for effectiveness and acceptability is limited;

-

there is no good quality evidence available for effectiveness or acceptability for some groups NICE considered to be at risk (those involved in commercial sex work /being sexually exploited; those not in employment, education or training; those who attend nightclubs and festivals);

-

none of the interventions were cost effective as a stand-alone intervention;

-

even the effective interventions generally had a limited effect on the proportion of participants who used drugs (“Most of the interventions did not change drug use by more than 5 percentage points.” NICE, 2017b);

-

none of the studies found a reduction in drug use sustained for more than one year;

-

most studies considered effect on use of cannabis and /or ‘ecstasy’, but not other drugs;

-

most evidence derives from outside the UK and may not, therefore, generalise to the UK situation.

3.48. For the intervention that it recommended (skills training for children and young people and their families), NICE noted only moderate evidence from four studies, all undertaken outside the UK. One RCT reported statistically significant reductions in drug use. Another study reported statistically significant reductions in some drug use but increases in cannabis use. One observational study reported no change in drug use. Three of the studies reported improvements in personal and social skills.

Indicated prevention: UNODC and WHO guidance

3.49. The UNODC and WHO standards identify only brief interventions as an indicated approach for which there is (some) evidence of reduction (specifically) in drug use (UNODC & WHO, 2018). This contrasts with NICE, which does not endorse brief interventions as being effective for the specific vulnerable groups that it has considered. However, the UNODC and WHO standards also note that the evidence for brief interventions suggests that effect sizes are small and do not persist beyond 6 to 12 months (interested readers are encouraged to read the full report).

Indicated prevention with families

3.50. Interventions which enhance family cohesion and relationship quality may moderate the impact of childhood adversity and prevent drug /substance use (Grummitt et al., 2021). Where the parent depends upon substances, integrated parenting interventions which combine components targeting substance use with those that seek to enhance parenting skill and parent-child relationships have been found to reduce the frequency of parental alcohol and drug use (McGovern et al., 2021a). However, while interventions to reduce parental substance use have been effective for parents, the review authors could not identify convincing evidence that this improved child outcomes. There is also an absence of evidence considering whether interventions which reduce parental substance use prevent their children from using drugs/ substances. It is likely, however, that children affected by parental substance use will need direct intervention to address their needs (McGovern et al., 2021b).

4. Prevention systems

4.1. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the World Health Organization describe prevention systems in the following terms:

“An effective national drug prevention system delivers an integrated range of interventions and policies based on scientific evidence, taking place in multiple settings and targeting relevant ages and levels of risk…. It is not possible to address such vulnerabilities by simply implementing a single prevention intervention, which is often isolated and limited in its time frame and reach.” (UNODC & WHO, 2018)

4.2. As noted elsewhere in this report, vulnerability to drug use (and a range of other risky, harmful or maladaptive behaviours) is a manifestation of exposure to a complex set of risk and protective factors, many of which are socially /socioeconomically determined. We might conceive of these factors as functioning as a system that, if circumstances align, engenders vulnerability. Whereas prevention has tended to be framed as a stand-alone, short-term activity, targeted at specific individual risk factors, and designed to address specific risky behaviour such as drug use. The ACMD supports the position of the UNODC and WHO (above) that prevention should be developed as a whole-system approach, whereby integrated, evidence-based interventions and policies are designed to pro-actively foster resilience. As noted in ACMD’s previous report, “Successful drug prevention is not just about what activities or programmes are delivered, but also how prevention systems are organised and implemented.” (ACMD, 2015; p.11).

Prevention systems approach: UNODC and WHO guidance

4.3. UNODC and WHO suggest that the foundations of an effective prevention system will require (UNODC & WHO, 2018):

-

“A supportive policy and legal framework.”

-

“Scientific evidence and research.”

-

“Coordination of the multiple sectors and levels involved (national, subnational and municipal /local).”

-

“Training of policymakers and practitioners.”

-

“Commitment to providing adequate resources and to sustaining the system in the long term.”

4.4. Interventions: should be evidence-based; support children and young people across the developmental course, with particular attention to transition periods when they may be more vulnerable; integrate universal, selective and indicated approaches; address individual and environmental risk factors and be situated across multiple settings.

4.5. Supportive policies: should embed regulatory policies (including for alcohol and tobacco) within a health-centred system; view drug use disorders as social and health conditions with complex, multi-faceted aetiology; sit within a national public health strategy for people’s healthy and safe development that targets a range of unhealthy /risky behaviours.

4.6. Regulatory foundations: should recognise quality standards (such as the European Drug Prevention Quality Standards (EMCDDA, 2011); include national professional standards; require the use, where possible, of only evidence–based approaches, possibly by making available a register of supported approaches;[footnote 2] require schools to implement prevention within the wider health and personal /social education curriculum as per current Department for Education guidance, (see Appendix C) and broader school policies (on substance use and adequate behaviours); require workplace prevention programmes; and require health, social and education services to support families to nurture the development of their children.

4.7. Research and planning: requires national systems to monitor the prevalence and patterns of drug use, the extent and impact of risk factors /vulnerabilities; proper mechanisms to review and respond to the evidence of need, of effectiveness and quality of interventions, and of adequacy of resources; and proper monitoring and evaluation of interventions, using experimental or quasi-experimental designs (also interrupted time series for environmental prevention strategies) to ensure that they are effective. The target population should be involved in framing and refining interventions, to enhance the latter’s acceptability.

4.8. Cross-sector involvement: all relevant sectors (e.g., health, education, welfare, youth, law enforcement) should be involved in planning, delivery, and monitoring, led by a coordinating agency.

4.9. Infrastructure: services responsible for delivery require adequate finance; individuals planning and delivering intervention require suitable, ongoing training and evaluation requires adequate resources.

4.10. Sustainability: medium- to long-term investment is required for prevention activities to reach their potential, and regular reviews of planning and progress are required.

Whole systems approach:

4.11. Systems-based perspectives have become increasingly influential in fields such as public health and criminal justice (EMCDDA, 2019b). Simply put, these types of approaches suggest that to better understand behaviours of interest (e.g., drug use) and the development of associated responses (e.g., prevention interventions), it is important to consider the dynamic interrelationships between different forces and factors across multiple levels (such as from the individual to society, and from social interactions to national policy), while also simultaneously considering behaviour of the system as a whole over time (Hassmiller Lich et al., 2013). Critically, the behaviour and characteristics of the system as a whole cannot always be anticipated from the behaviour and characteristics of any one element of that system, so, for example, policy and intervention may sometimes have unexpected effects.

4.12. There have been calls in the drug prevention field to think about prevention activity within a systems perspective (EMCDDA, 2019b; Hassmiller Lich et al., 2016; Sloboda & David, 2021). This would mean moving away from a focus on traditional evidence-based manualised prevention programmes and interventions delivered by specialists (e.g., Burkhart et al., 2022), although these are still valuable tools to support specific groups or to respond to specific drug-related issues (e.g., schools, nightlife settings). A systems perspective means thinking about how prevention can be ‘normalised’ across diverse areas of policy and practice so that it becomes embedded in professional practice, cultures and supportive environments. It also means that health and social care services and professionals, who would not ordinarily consider themselves being part of the drug prevention response, integrate and sustain evidence-based practices into their on-going work.

4.13. The above approach is implicitly supported in the 2021 Drugs Strategy, where multiple departments have responsibility for responses to drug use, and cited policy activity such as the Changing Futures and Supporting Families programmes, and Start for Life services, target ‘up stream’ risk factors for drug use, although it may not be directly labelled as drug prevention activity. However, this perspective requires learning and leadership to change attitudes, policies, and delivery systems, as in reality there may only be loose policy and infrastructural harmonisation (Armstrong et al., 2006; Babor et al., 2008; UNODC & WHO, 2018). It also requires an update in conceptualisations of drug prevention, whereby policy and research questions about what constitutes drug prevention (e.g., programmes vs. activities supporting health development), and whether drug prevention is ‘effective’ in isolation, are replaced with those that explore how prevention contributes to the overall effectiveness of the whole system response to drug use and associated harm, and encourages the planning and provision of resources for all the different components of the system that are necessary for effective prevention (EMCDDA, 2019b).

4.14. There are some other practical motivations to think about prevention in these ways. Unlike the treatment and harm reduction field, there is no professional role of drug prevention practitioner in the UK, relevant competencies are usually secondary to specialist treatment or other professional skills (e.g., drug worker, social worker, health improvement specialist), and there is no recognised qualifying route into practice, and so prevention is learned ‘on the job’ (Ostaszewski, et al., 2018; Pavlovská, et al., 2017; Sumnall, 2019). Embedding prevention within the ‘whole system’ will require that professionals within that system are adequately trained both, to identify those who are vulnerable and to deliver suitable intervention. For example, the social work and social care workforce are well placed to support prevention work across the life course, particularly with more vulnerable groups of people given the wide range of specialist social work disciplines. However, substance use education is neither a core, or a mandated part of their qualifying or post qualifying training (Galvani & Allnock, 2014; Hutchinson and Allnock, 2014). This will need addressing at qualifying and post qualifying levels to equip professionals to intervene appropriately.

4.15. The relative scarcity of expertise to deliver such training at the scale that is required may present challenges. However, these might be addressed via the development of, for example, suitable, central online training resources to supplement mandatory pre and post qualifying prevention training. In view of the past failures of social and health care qualifying programmes to include substance use in their curricula, any future inclusion, including prevention approaches will need to be mandated and monitored. Training for local decision makers also is required and the European Prevention Curriculum (EUPC) being developed by the EMCDDA may be especially informative in this regard (See, EUPC [Accessed on 06 May 2022]).

4.16. Over the last decade, as local authorities sought to protect statutory services and prioritise drug treatment services in response to reductions in funding (ACMD, 2017), drug prevention activity and infrastructure (service providers, professional roles, programmes) were scaled back (Black, 2020). While organisations such as NICE have developed specific prevention guidance for vulnerable young people, and previous UK drugs strategies included commitments to targeted drug prevention activity, these have not been implemented at scale, and it is unclear whether the UK has the capacity to do so (ACMD, 2015; NICE, 2017). New funding announced in response to the drugs strategy and the recommendations of Part 2 of the Dame Carol Black report (Black, 2021) could help rebuild prevention infrastructure, but this is likely to be a long-term activity that requires significant capacity building (Chinman, et al., 2019; Fagan, et al., 2019).

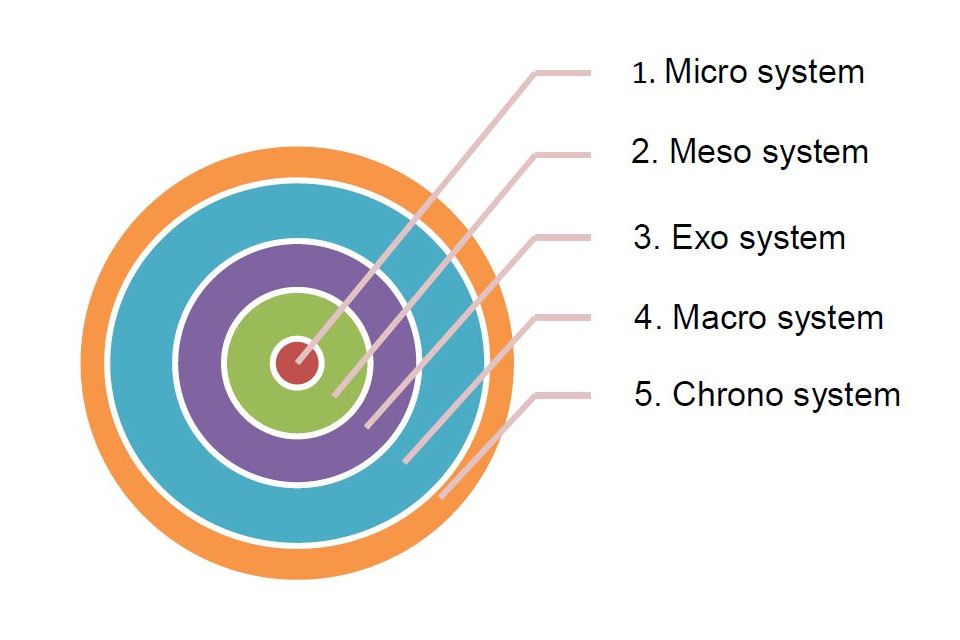

4.17. As noted above, Part 2 of the Black report (Black, 2021) and the government’s subsequent 10-year Drug Action Plan (HM Government, 2021) refer to a whole systems approach. The strategy states that success relies on a wide range of local partners working together toward its long-term ambitions. The Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (formerly Public Health England, PHE, 2019) has recognised such approaches as the required response for complex public health concerns such as obesity. Drug prevention work needs to be developed that aligns what is known about prevention with a whole systems approach, possibly through the vehicle of Integrated Care Systems (ICS) once their effectiveness is known. Whole systems approaches move beyond identifying key departments or organisations that need to be involved. It requires the involvement of individuals with lived experience (micro system), the communities they live within (meso system) and the organisations and policy structures that envelope them (exo system) (Bronfenbrenner, 1977; 1986). It also acknowledges that shared ideologies and cultures (macro system) play an influence and that systems change over time (chrono system). This is not a static approach but one that is dynamic within and between systems.

Figure 2: Bronfenbrenner’s model of nested systems.

4.18. Stansfield et al., (PHE, 2020; p.10) in their work for PHE identifies the five principles underpinning whole systems work as:

-

“ Bold leadership to adapt radical approaches to reduce health inequalities;

-

collective bravery for risk-taking action and a strong partnership approach that works across sectors and gives attention to power and building trusting relationships with communities;

-

co-production of solutions with communities, based on new conversations with people about health and place;

-

recognising the protective and risk factors at a community level that affect people’s health, and how these interact with wider determinants of health;

-

shifting mindsets and redesigning the system, aligned to building healthy, resilient, active and inclusive communities.”

4.19. Drug prevention at a whole systems level, for adults, for children, and young people, needs to develop interventions that are underpinned by these principles. The requirements in the strategy that each local area should have a strong partnership that brings together all the relevant organisations and key individuals to support the new Integrated Care Systems (ICS) should also apply to prevention work. They may provide a novel opportunity and mechanism for local implementation of prevention strategy. They need to be rigorously evaluated to improve the evidence base and knowledge of what works.

5. Conclusions

5.1. There is a variety of drug prevention interventions that are likely to be effective in the UK context, however, we cannot be certain that interventions that have been successful in other countries will generalise to the UK and that effect sizes even for ‘effective’ interventions tend to be small to moderate. There is evidence of what does not work in drug prevention.

5.2. Although the evidence base for prevention amongst children and young people is reasonably well-developed, there is a dearth of evidence regarding ‘what works’ for vulnerable adults.

5.3. The most efficient interventions target multiple risk behaviours, rather than focusing specifically on drug use, and are designed to enhance well-being and healthy development across a range of domains.

5.4. Despite some evidence of ‘what works’, the UK lacks a functioning drug prevention system, with workforce competency a key failing in current provision. As illustrated by the NICE guidance above, identification of and responses to risk needs to be embedded across the health, social care and educational systems, etc. However, a lack of workforce skills, including at decision maker levels, impedes implementing effective strategies.

5.5. There is no ‘silver bullet’ that will address the problems of vulnerability to drug use. Improving resilience will require significant, long-term public investment to rebuild prevention infrastructure and coordination of the whole range of services that can be harnessed proactively to increase the likelihood of healthy development of children and young people across a range of domains, including efforts to address inequalities, social capital and social norms (UNODC & WHO, 2018).

5.6. A sole focus on vulnerable ‘groups’ will limit the reach of prevention activities; rather, prevention should be targeted also at the risk factors, contexts, and behaviours that make individuals vulnerable. Strategies to reduce vulnerability must also target structural and social determinants of health, well-being and drug use.

6. Summary of recommendations:

Recommendation 1

The ACMD endorses the selective prevention activities recommended by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) ‘International Standards’ for drug use prevention (UNODC & WHO, 2018) and the indicated prevention activities recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, 2017a). These should be the starting point for selective /indicated prevention activities delivered under the auspices of the government’s drugs strategy and their development, organisation and delivery should reflect the European Drug Prevention Quality Standards (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2011).

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit (JCDU)

Measure of impact: Evidence that guidance and policy issued by government departments reflects the above advice.

Recommendation 2

ACMD’s strong advice is that drug prevention activities that have been ineffective, such as fear arousal approaches (including ‘scared straight’ approaches) or stand-alone mass media campaigns, should not be pursued or supported; funding for these would be better used elsewhere. Where the effectiveness of an intervention has not been demonstrated or is uncertain. its implementation should only be regarding properly resourced, methodologically robust, rigorous, peer-reviewed, evaluative research. National policy and guidance should reflect this advice, e.g., regarding drugs education, and in guidance to organisations tasked with implementing prevention at the local level.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Evidence that guidance and policy issued by government departments reflect the above advice.

Recommendation 3

There is a dearth of evidence relating to prevention approaches for adult populations. There is a pressing need to improve understanding of adult vulnerability to drug use and to develop effective prevention approaches suitable to the circumstances of vulnerable adults. Resources for research to support this should be identified within the cross-government innovation fund announced within the drugs strategy.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Call for research in this area to be issued, utilising resources within the cross-government innovation fund.

Recommendation 4

The UK should aim for a strategy in which universal, selective, and indicated prevention approaches are integrated across policy in a ‘whole system’ approach. There is a need to invest in workforce training to ensure that the professionals within the ‘whole system’ are equipped to respond appropriately to those who are vulnerable. This will require work to encourage the relevant professional bodies to embed prevention learning within their accredited training schemes, at qualifying and post-qualifying stages, including continuing professional development. This might be addressed by developing, for example, suitable central online training resources to supplement mandatory pre and post qualifying prevention training. This will need to be mandated and monitored given the failure of previous curriculum guidance for social and health care qualifying education.

Lead organisations: Joint Combating Drugs Unit, Department for Education (DfE), Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC)

Measure of impact: The setting up and reporting of a joint working group involving JCDU, DfE, DHSC, professional bodies and prevention experts to investigate the development of curriculum content and supplementary training resources, to be embedded in accredited schemes.

Recommendation 5

A focus solely on ‘vulnerable groups’ will limit the reach of prevention activities and contribute to stigmatisation and discrimination, thus it is potentially counterproductive. Rather, government policy, advice and guidance should refer to vulnerable people, acknowledging the dynamic, complex and individual nature of vulnerability, reflecting the importance of characteristics, behaviours and contexts, including the significant influence of structural, environmental and social determinants of well-being.

Lead organisation: Joint Combating Drugs Unit

Measure of impact: Evidence of advice, guidance and policy having been issued by government departments reflecting the above advice.