Final report

Published 23 July 2021

Summary: Building a comprehensive and competitive electric vehicle charging sector that works for all drivers

Overview of our findings

The UK has committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 28% by 2035 and moving to Net Zero by 2050. Transport, in particular cars, is the largest source of emissions (accounting for 27%). Transitioning from petrol and diesel cars to electric vehicles (EVs) is therefore key to reducing emissions and meeting Net Zero. Reflecting this, the UK Government has committed to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars/vans from 2030.

For this to happen, however, it is essential that there is a comprehensive and competitive EV charging network in place, one that people can trust and they are confident using – much like filling up with petrol or diesel. If this is not the case, and the charging network is perceived as inadequate, or as not offering a fair deal to people, that will be a major barrier to EV take-up.

The scale of the shift to EVs – requiring the development of an entirely new network – should not be underestimated. While it is difficult to know precisely how much charging will be needed, forecasts suggest that at least 280 to 480,000 public chargepoints will be needed by 2030 – more than 10 times the current number (around 25,000).

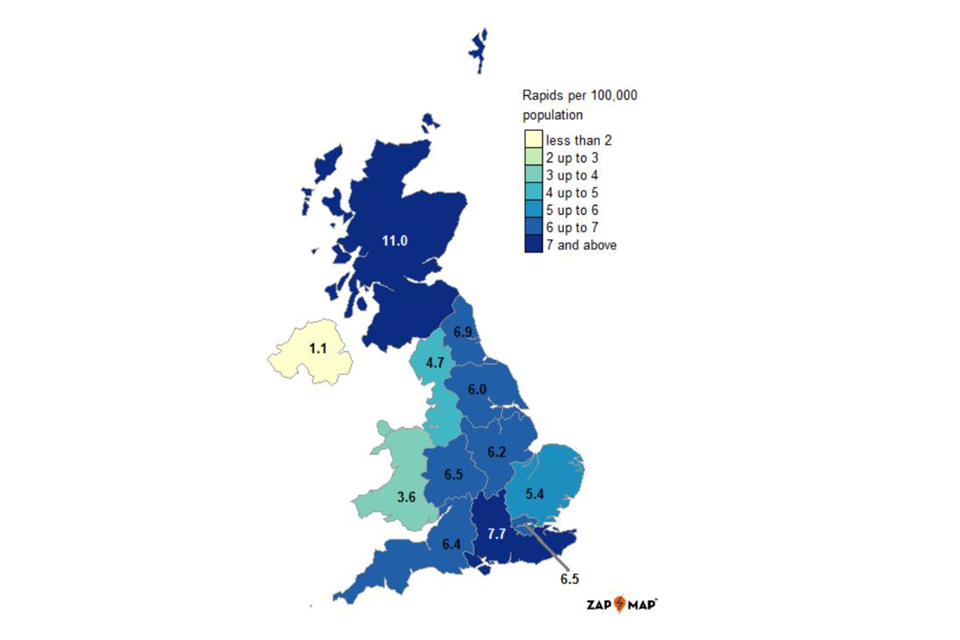

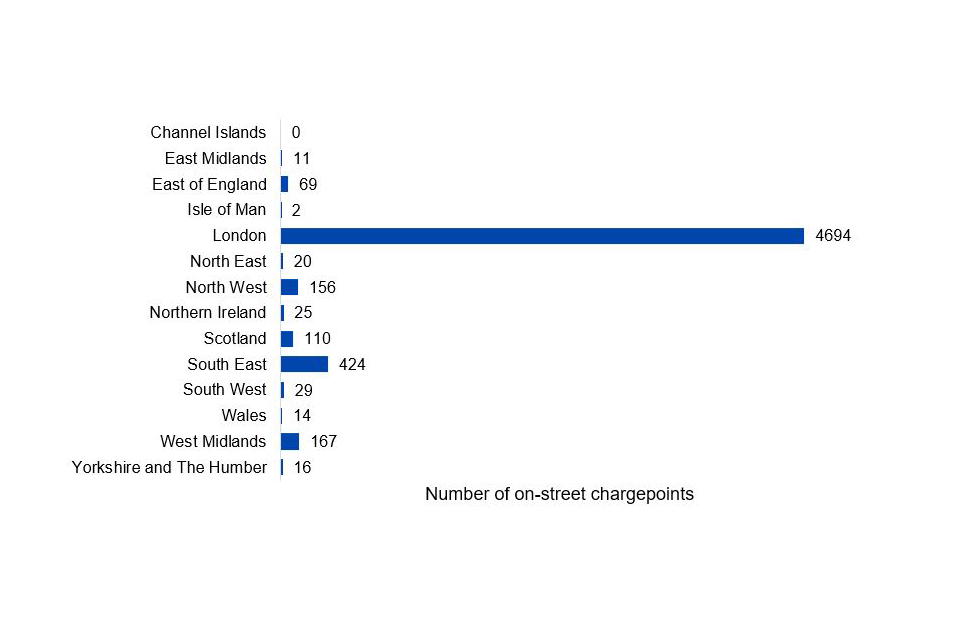

There will also need to be a suitable mix of different types of charging spread across the UK. While many people will regularly charge at home or work (if they can), a sufficient range of public charging is important to encouraging EV-take up. Rapid charging on longer journeys (such as on motorways and in remote areas) and on-street charging at the kerbside (for those without a driveway or garage) will be particularly important. But this is currently far from the case - access to suitable charging can be a ‘postcode lottery’. For example, outside London there are only 1,000 on-street chargers (out of 5,700). Some areas are at risk of getting left behind – for example, the number of total chargepoints per head in Yorkshire and the Humber is a quarter of those in London.

We have examined how this critical new sector is developing and whether the sector left to its own devices can deliver what is needed. While some parts of the sector are developing relatively well (such as rapid charging at destinations like shopping centres and charging at home or work), other parts are lagging behind. We found greater challenges in rolling-out charging along motorways, remote locations and on-street. Therefore, targeted interventions are necessary to kickstart more investment and unlock competition:

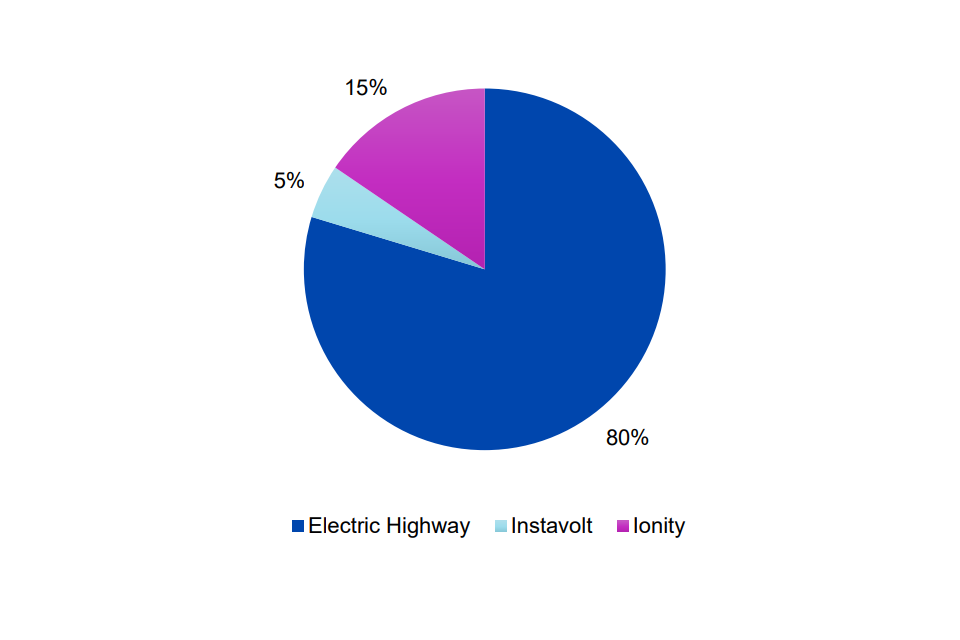

- along the motorways where competition at service stations is very limited (one chargepoint operator – the Electric Highway - has a share of 80%). Constraints on electricity grid capacity and long-term exclusive contracts (covering around two-thirds of service stations) prevent entry by competitors at many sites. The Government’s commitment to fund grid upgrades provides an important opportunity to open up competition within these key sites, as well as putting in many more chargepoints

- in remote areas, where the commercial case for investment is very weak, which means there’s a risk these will be left unserved

- in on-street charging where roll-out is very slow and local monopolies could arise if the market is left unchecked. Local authorities (LAs) play a crucial role here in rolling-out chargepoints and actively overseeing the market to maximise competition and protect local residents, but they are not all currently sufficiently equipped or incentivised to do this

We have also found that there are other problems for EV drivers which can make EV charging challenging. It can be difficult and frustrating to find and access working chargepoints, and to compare costs and pay for charging. Emerging developments like subscriptions and bundling could create more problems in the future like ‘lock-ins’ (difficulties exiting contracts).

In practice, using and paying for charging should be as simple as petrol or diesel. Everyone should be able to access convenient and affordable charging, no matter where they live. As we’ve seen in other markets, if it becomes complex or confusing, this damages people’s trust – which is not only a concern in itself but also a barrier to EV take-up. Deliberately steering the sector in the right direction now will help ensure that people do not lose confidence at this crucial early stage.

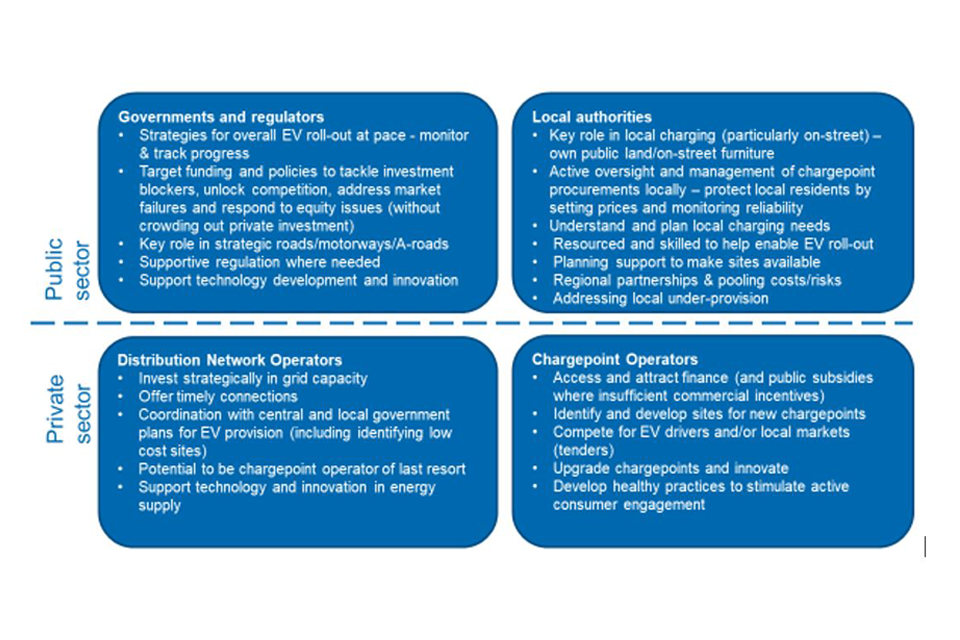

While healthy competition will be critical to meet these challenges, market forces alone will not deliver what is required – in particular due to the wider environmental benefits of reducing carbon pollution. Even further government support, funding and oversight is also needed to push forward the pace of roll-out ahead of demand, working alongside key bodies like LAs and regulators.

We have made 8 recommendations to promote competition, unlock investment, and build people’s trust, both now and in the future. But there are still many uncertainties, so it is important for measures to be responsive and for the sector to be monitored closely going forward.

Very limited competition along motorways

Being able to recharge as quickly as possible on longer journeys (en-route charging) is crucial to persuade drivers to switch to EVs as it will alleviate concerns about ‘range anxiety’ (the fear of running out of charge). But on motorways there has been very limited competition to date. At most motorway services there is just one chargepoint operator – the Electric Highway –leaving little choice for drivers. Customer satisfaction has been very low, driven by concerns about poor reliability and limited chargepoints.

Many of these critical motorway services require costly increases in grid capacity before more chargepoints can be installed, which is a major barrier. The Government’s £950 million Rapid Charging Fund (RCF) has been set up to fund these grid upgrades in England - this provides a pivotal opportunity to open up and increase charging competition within motorway services, as well as increasing grid capacity. This will play a critical role in enabling there to be more than one chargepoint operator at service stations. Greater competition at services will help to deliver more choice, better reliability, low prices and continued innovation. But to achieve this, the RCF needs to be designed in the right way, otherwise there is a risk that if the funding primarily goes to the existing operators it could further entrench competition problems.

We also have concerns about the long-term exclusivity agreements between the Electric Highway and 3 motorway service operators (Roadchef, MOTO and Extra) which cover around two-thirds of service stations and last between 10 to 15 years since the contracts were entered into, with several years remaining on these. We are concerned that these arrangements increase barriers to entry for other chargepoint operators and, importantly, risk undermining the effectiveness of the RCF. While some period of exclusivity may have been necessary initially, the need for this increasingly looks far from clear, particularly given greater certainty over future EV demand and the introduction of the RCF. Several competitors told us they would look to enter and compete at motorway services but are prevented by these agreements.

Risk of ‘charging deserts’

Off the motorway in remote locations like rural areas or at tourist spots (where connection costs are high but demand may be lower), the business case for commercial investment in rapid en-route charging may be weak. This increases the risk of ‘charging deserts’ emerging which could deter EV take-up, both for EV drivers living in those areas and for those travelling to or through them.

Challenges for local authorities supporting on-street roll-out

We also found problems for some people charging near their home – where more than a quarter of drivers do not have access to a driveway or garage and cannot install a home chargepoint (over 8 million households). For those drivers, having convenient and affordable local public charging will be crucial to EV take-up. On-street slow or fast charging near the home (where EVs can charge overnight), offers a more convenient, easier and cheaper way to charge than relying on rapid hubs (akin to petrol forecourts) or destination charging. Drivers could save over £100 a year by using an on-street chargepoint rather than rapid charging (which costs around 60% more than home charging). It also has greater benefits for the grid as when EVs are plugged in they can help manage the intermittency of renewable energy sources by providing flexibility as well as smoothing demand.

But roll-out in on-street has been slow and is very patchy. The commercial case for on-street charging is weak and it is currently reliant on government subsidies. This is delivered through grant funding which LAs can apply for, though many haven’t – a third of the available funding has gone unspent.

LAs in Great Britain have a key gatekeeper role as they are responsible for parking and street furniture like lampposts where on-street charging is often installed. They also understand local needs. But while there are some examples of good practice, we found that generally LAs do not have any plans in place, dedicated personnel, financial resources or in some cases the appetite to drive forward roll-out. They do not have a clearly defined role – EV charging is not one of their statutory duties and so it can be a lower priority, particularly given competing demands on their resources and the other services they must provide.

The costs of installing on-street chargepoints and the fact that people generally want to charge near their home, means that on-street competition (where there’s a choice between different operators) is often not feasible – at least at the moment. Therefore, there is a risk that, if left unchecked, local monopolies could develop. An alternative way to create competitive pressure is through tenders currently run by LAs ‘for the market’. To be effective these need to be actively managed and monitored. But many LAs do not have sufficient resources - with some favouring working with a single chargepoint operator in an area, which, while easier, could put LAs in a weaker position in the long-run leading to worse quality or prices for residents.

To deliver sufficient, competitive on-street charging which encourages EV take-up, a step change is needed. LAs will need to play a much more active role in rolling-out charging and maximising competition by actively overseeing the market to ensure high quality, affordable charging for local residents. To do this effectively LAs need to be sufficiently equipped, supported and overseen at national levels – ensuring that no areas lag behind.

Frustrations facing EV drivers

Building trust in the sector is also vital for successful EV take-up, particularly at this early stage. Using and paying for public charging needs to be a simple, positive experience – much like it is with petrol and diesel.

While there have been some improvements, many EV drivers find charging to be complex, confusing and frustrating at times. On top of a lack of chargepoints which is a significant concern, reliability can be poor (on average 1 in 25 chargepoints are out of service – though this has been improving). Not all chargepoint operators make live data on availability and working status freely available which can make it hard to find chargepoints. It can also be difficult to find and pay for charging easily (with multiple apps or cards needed) as well as comparing prices. Currently only 9% of public chargepoints have contactless bank account payment which is a simple way to pay for charging.

Some people may have even greater problems engaging in this sector (such as those with disabilities who may face additional barriers due to the design or location of chargepoints or those who are less ‘tech-savvy’). Charging should be designed to meet different needs so that no-one is left behind. Open and interoperable charging networks that can be used easily by all drivers and brands of EVs is fundamental.

There are also some emerging developments which could cause problems down the line for people. For example, we have seen evidence of growing consideration by chargepoint operators of subscriptions and bundling. There is a risk that if these become more common, they could make it even more confusing for people, harder for them to understand and compare deals, and potentially lead to harmful subscription traps that exploit people’s inertia and make it difficult to exit.

We expect that some aspects of the charging experience, such as reliability, are likely to improve over time as the sector evolves, competition develops and more chargepoints are rolled-out. However, in the meantime, a difficult charging experience will undermine trust and put people off EVs.

While home charging is generally easier for people to use, we found that there are some issues which mean that people may not benefit from smart charging or other future benefits. Smart charging (ie enabling drivers to charge when energy is cheapest) can save people money, benefits the grid as it helps manage demand and maximises the use of renewable electricity. Therefore, we welcome the Government’s plans to require home chargepoints to be smart, otherwise people could miss out by buying ‘dumb’ chargepoints. Open standards for controls and data used by home chargepoints can help to fully maximise the benefits of smart charging by simplifying and automating it. It will also make it easier for third-parties to develop innovative solutions and applications for controlling home charging and other home energy services. As we found in banking, open data and standards can be critical to opening up competition in markets.

Markets alone cannot deliver – government support is critical

In addition to the specific challenges facing some parts of the sector, there are various underlying factors which explain why market forces alone will struggle to deliver the EV charging infrastructure needed by 2030. In particular, left to their own devices, markets do not take into account the full benefits of carbon reduction. Changing to an electricity-based transport system will also result in significant upfront infrastructure costs for example, the costs of installing chargepoints and connecting to the grid, many of which fall on the industry. There is also a ‘chicken and egg’ problem, where the commercial viability of EVs depends on a widespread charging network being in place, but the case for building that network is also dependent on the number of EVs on the road.

The transition to EVs will also impact the energy system. While there is expected to be enough power available to meet demand, in some places, grid upgrades will be required. However, EVs will also benefit the electricity system by providing flexibility to store energy and balance demand when plugged in for long periods of time, helping avoid the need for upgrades. Smart, slower charging at home or on-street will provide more of this flexibility than rapid charging.

The scale of these challenges and the need for a rapid roll-out mean that left to their own devices, markets will not be able to deliver. As a result, continued active government involvement at local and national levels will be needed to push forward the pace of roll-out and target funding and support at the areas where it is most needed, building on what is already being done. The energy regulators (Ofgem and Uregni) and energy distribution companies responsible for making connections to the grid, will also need to play their part to ensure that new EV charging infrastructure is installed efficiently and quickly. Many chargepoint operators told us that it can be a very lengthy process to connect to the grid and upgrades can be very costly – which has a significant impact on the pace and incentives for roll-out.

Our recommendations

We have made 8 key recommendations to unlock greater investment, promote competition and boost trust in the sector.

While transport is partly devolved and therefore approaches between the nations vary, we have found that the broad challenges are similar and therefore our recommendations are UK-wide. However, we recognise that circumstances and needs vary within each nation, therefore some have more or less relevance. It is important for lessons to be shared between nations, to help ensure that a comprehensive network is in place across the UK.

Meeting the scale of the overall challenge

- UK Government sets out an ambitious National Strategy for rolling out EV charging between now and 2030, alongside strategies from each of the Devolved Administrations – building on the work already underway

- Ofgem and Uregni make changes to speed up grid connections, invest strategically and lower connection costs - so that the electricity system supports roll-out

Unlocking competition along motorways and targeting rural gaps

- UK Government rolls-out the Rapid Charging Fund as quickly as possible to increase capacity at motorway service stations and attaches conditions to this funding so that it opens up competition at these key sites (eg no exclusivity in future, open tendering, chargepoints interoperable with all EVs and open networks available to all brands of EV). We also have concerns about the long-term exclusivity in the contracts between the Electric Highway and motorway service operators (Roadchef, MOTO and Extra), and therefore we have launched a competition law investigation into these

- Off motorways, governments consider targeting funding at gaps in remote areas which may otherwise not be served

Boosting investment and maximising competition in on-street charging

- LAs take a more active role in planning and managing the roll-out of on-street charging to maximise competition and protect local residents, putting in place local plans and take into account key factors we have set out

- Governments take action to properly equip and incentivise LAs while also providing greater support and oversight - including providing funding for dedicated expertise and defining their role eg via a statutory duty – in order to achieve a step change, and work with LAs to explore and pilot other ways of rolling-out on-street charging

Creating a sector that people can trust and have confidence in

- UK Government sets open data and software standards for home chargepoints so people can benefit from smart charging and flexible energy systems

- UK Government takes into account the following principles to ensure charging is as simple as filling up with petrol/diesel and tasks a public body with implementing, overseeing and monitoring these as the sector develops to build people’s trust:

- It is easy to find working chargepoints for example, people can access open data on live availability and working status and rely on minimum reliability standards

- It is simple and quick to pay for example, no sign-ups needed, contactless bank account payment is widely available and charging networks keep up with payment technology

- The cost of charging is clear for example, prices are presented in a simple standardised pence-per-kilowatt hour format

- Charging is accessible and interoperable for example, all chargepoints can be used by all drivers, are not limited to a single brand of car, and follow inclusive design principles

Next steps

We will continue to work with the governments as well as the industry, to ensure a healthy charging sector develops. There are still many uncertainties about how the sector and technology will evolve. As a result, strategies, plans and measures for the development of EV charging must be flexible and responsive.

Given how important this sector is, we will oversee progress as it evolves over the next few years. We will take further action if the sector or parts of it are developing in a way that is damaging competition and investment and not working well for people.

Key statistics

Scale of the challenge

At least 10 times the current number of charge points needed by 2030.

Current provision:

- UK network has grown to around 25,000 public chargepoints

- only 34 public chargepoints per 100,000 people on average in the UK

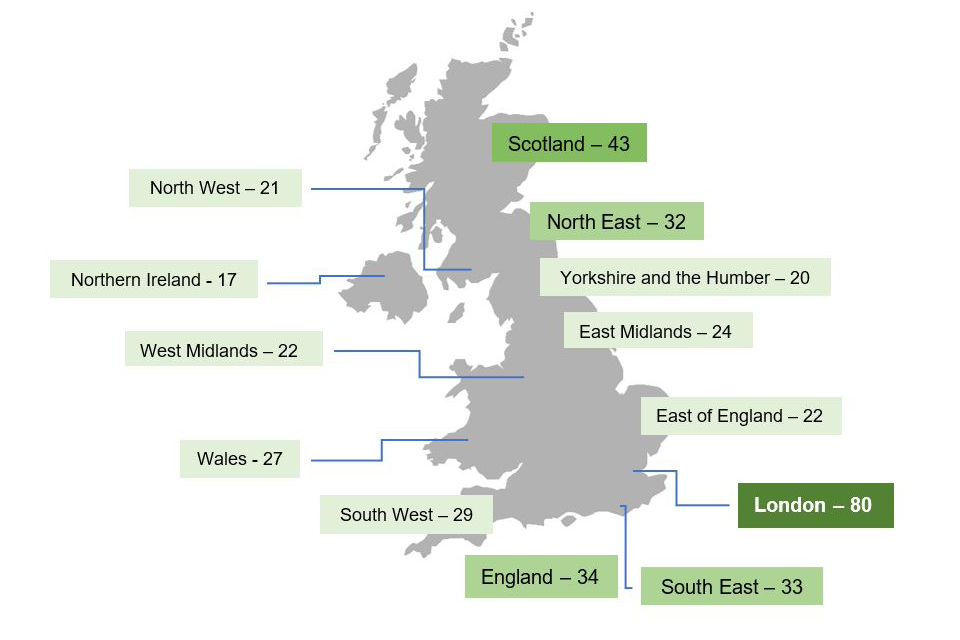

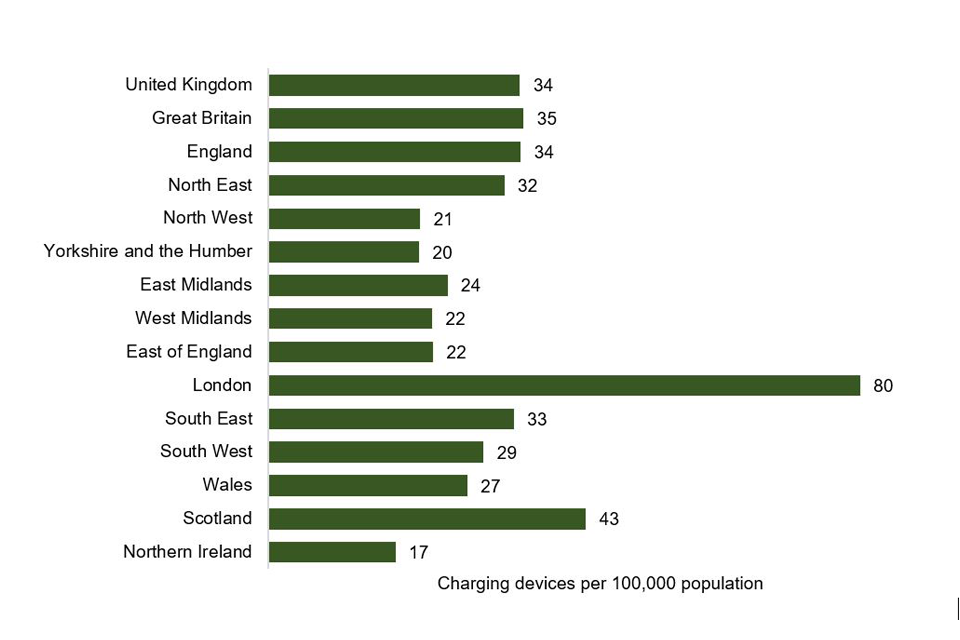

Uneven and patchy provision:

Chargepoints per 100,000

Image showing how many chargepoints there are in areas around the United Kingdom

En-route charging

500+ chargepoints installed at motorway stations, estimated 2,300 needed.

- Lengthy exclusivity agreements covering around two-thirds of motorway service stations

On-street charging

Only 1,000 on-street chargepoints outside of London - out of 5,700 in the UK.

- over a quarter of drivers don’t have a driveway or garage – 8 million+ households

- drivers could save over £100 a year using on-street as opposed to rapid charging

- almost one-third of government funding has not been taken up by LAs (ORCS)

People’s experience of public charging

- only 9% of chargepoints offer contactless payment – 50% of rapid / ultra-rapid

- 1 in 25 chargepoints, 1 in 10 rapid are out of service at any given time on average

Summary of the CMA’s recommendations

""

""

1. Introduction

The transport sector is the largest source of carbon emissions in the UK. The majority of these emissions come from cars, [footnote 1] and therefore a smooth transition to electric vehicles (EVs) will be critical to achieving the UK Government’s legally binding commitments for Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050. [footnote 2] This shift is even more imminent following the UK Government’s commitment to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030. Supporting the transition to a low carbon economy is a CMA priority.

Putting in place sufficient EV charging infrastructure in the right locations, and building consumer trust and confidence in the sector, will be key to successfully transitioning at pace to EVs. ‘Range anxiety’ - the worry an EV will run out of charge - is currently a key barrier to EV take-up, among other factors. It is therefore a priority to put in place a comprehensive charging network and as the sector develops it will be important to encourage greater growth and investment which maximises competition, as well as ensuring that the charging network works well for all consumers.

Purpose of the study

Our market study has considered the supply of chargepoints for electric passenger vehicles (cars and light vans)[footnote 3] across the UK, which is an emerging but fast-growing sector. We focused on 2 key themes:

-

whether the sector can deliver the scale and pace of investment needed in a way that also enables a competitive sector which delivers good outcomes to consumers, and what measures can help to unlock competition and incentivise investment in the sector

-

how people interact with this new and potentially complex sector and any problems they may face, and what measures may be needed to ensure charging is easy and convenient, so that mistrust does not become a barrier to roll-out

We looked at the EV charging sector as a whole and whether there are particular issues in different parts of the sector for example, charging at home, work or publicly. We particularly focused on charging on-street and along motorways, which have additional challenges and are likely to be particularly important going forward to help drive EV take-up and address range anxiety.

While we have examined EV charging, we recognise that there are a number of other relevant factors impacting EV take-up, including the upfront cost of EVs and their supply. [footnote 4] We note that over time prices are expected to fall alongside the development of a second-hand market and a number of car manufacturers have recently announced intentions to increase supply. [footnote 5] We consider other factors which are relevant to the development of the EV charging sector, including potential technological developments and the sector’s interrelation with the electricity system, in chapter 2 and chapter 3.

Work undertaken

We gathered and assessed a wide range of evidence and views, including submissions, internal documents and data from businesses in the sector and other key stakeholders such as consumer and trade bodies. We also held a series of roundtable sessions to discuss key challenges. We received around 50 submissions directly from individual consumers. All submissions are published on the case page, alongside our 2 progress updates.

We carried out analysis using data commissioned from Zap-Map, a third-party aggregator of information on chargepoints and networks. The data included reports on the number of chargepoints in the UK, pricing and reliability. We also carried out analysis on prices based on this Zap-Map data, as well as information from chargepoint operators. More detail on both of these is set out in Appendix E. As part of our information gathering, we received a wide range of internal investment plans and business models from chargepoint operators which we examined in detail, particularly in relation to on-street charging and motorways. We also assessed a range of consumer research.

We engaged regularly with governments across the 4 nations and relevant regulators, who are also undertaking significant work in this area (as set out further in chapter 2 and subsequent chapters). We also engaged with other competition authorities and government bodies, in particular Norway, France, the Netherlands and Germany. A number of UK organisations have recently or are currently carrying out work in this area, which we have considered in our study.[footnote 6]

This report

This final report sets out our findings and proposes measures to address the issues we have identified during our market study.[footnote 7]

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Chapter 2 provides background on what EV charging is and the sector

- Chapter 3 sets out the progress of roll-out and scale of growth needed

- Chapter 4, Chapter 5 and Chapter 6 provide an analysis of investment and competition in en-route, on-street and in home, workplace and destination charging

- Chapter 7 looks at the problems people face using public charging

- Chapter 8 presents the CMA’s conclusions and recommendations

- Further details on the evidence we have considered is set out in supporting appendices

2. Background to electric vehicle charging and the sector

This chapter provides an overview of EV charging and the sector. It covers:

- how and where EVs are charged

- charging and the electricity system

- developments in technology

- chargepoint operators and private investment in the sector

- policy approach and public funding (UK and in the 4 nations)

- regulatory framework

How electric vehicles are charged

There are 2 types of EV – all-electric (battery operated) and plug-in hybrids. The number of EVs is growing - as of end of May 2021, there were over 500,000 EVs registered in the UK, representing growth of 66% from 2019.[footnote 8] The Climate Change Committee (a public body which sets and advises UK Government on meeting carbon budgets) estimates that by 2030 there could be around 16 million EVs in the UK (though this is dependent on various factors - see also chapter 3).

In order to charge, EVs need to be parked and plugged into a chargepoint which is connected to the electricity network. The time it takes to charge an EV will vary according to the speed of the chargepoint - ultra-rapid, rapid, fast or slow[footnote 9] - which is based on its power output (in kilowatts - kW), and the type of battery in the EV. EVs can also charge via a three-pin plug, though this has a low power output and is therefore much slower. Table 1 sets out the estimated charge time based on the speed of charge. Currently only high-end EVs are capable of charging at ultra-rapid speeds.[footnote 10]

Table 1: charging speed by power (kW) and charge time

| Slow | Fast | Rapid | Ultra-Rapid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power | 3 to 6 kW | 7 to 22 kW | 23 to 50 kW | 51+ kW |

| Charge time (varies by EV model) | 3 to 8 hours | 1 to 3 hours | 20 to 40 minutes | 15 to 30 minutes |

EVs can charge with either Alternating Current (AC) or Direct Current (DC) electricity.[footnote 11] AC electricity can be used by all speeds of chargepoints whereas DC electricity can only be used by rapid or ultra-rapid chargepoints.

EVs have different types of connector for different speeds of charge:

- for slow / fast AC charging, EVs typically use a Type 1 or Type 2 connector (typically used by new EVs)

- for ultra-rapid / rapid DC charging, EVs typically use either a Combined Charging Standard (CCS) or CHAdeMO connector type

EVs can only plug into chargepoints with the same type of connector, unless an adapter is used.[footnote 12] Most chargepoints offer multiple connector types (for example, both CCS and CHAdeMO) and are therefore largely interoperable with different EV models.[footnote 13] In practice this means that most EVs will generally be able to use most public chargepoints. The main current exception is the Tesla Supercharger network which is a closed network that currently can only be used by Tesla EVs – we discuss this further in chapter 7.

Where charging takes place

Chargepoints can be installed in various places, each representing a different segment of the sector. Different speeds of charging can be more suitable in each of these segments:

-

home charging - charging in a driveway or garage for those with off-street parking (approximately three-quarters of drivers).[footnote 14] A slow or fast chargepoint is installed and connected to the home electricity supply

-

workplace charging - charging in workplace car parks generally for use by employees. Chargepoints are typically slow or fast and can be used as an alternative to charging at home[footnote 15]

-

destination charging - charging in car parks at places which consumers have travelled to for example, supermarkets, shopping centres, cinemas, restaurants and tourist attractions. Chargepoints are typically fast or rapid (slow or ultra-rapid are less prevalent)

-

on-street charging - charging which largely comprises chargepoints set up on the kerbside (for example, installed in lampposts or bollards) or in car parks regularly used by local residents, and is generally used by those who do not have access to off-street parking. These chargepoints are slow or fast and can be used overnight – similar to home charging.

-

en-route charging - charging along motorways at motorway service areas (MSAs) or at service stations on A roads and trunk roads, for drivers to top up generally when travelling on longer journeys. Chargepoints are rapid and ultra-rapid. Rapid hubs (groups of chargers) are also being developed in local areas (more akin to petrol stations).

Throughout this report we refer to destination, on-street and en-route charging collectively as ‘public charging’ because chargepoints in these segments are generally accessible to the general public.[footnote 16]

Currently where consumers choose to charge is largely dependent on the provision of chargepoints in the different segments - which we explore in chapter 3. People’s preferences and needs will also influence their charging choices. These will vary depending on their living, working and travel behaviours (ie jobs, commuting, lifestyle, type of home, parking), as well as the physical characteristics of the area they live in (ie rural/urban).[footnote 17] Given the early stage of this sector, the extent to which the different segments will be used in future is uncertain. However, it is likely that drivers with off-street parking will charge at home most of the time. Around a quarter of drivers who are without off-street parking will likely charge at work if they can, or will be reliant on the public charging network (on-street charging is likely to be particularly important for day to day charging).[footnote 18] All drivers will need to use public charging at some point, for example using destination chargers to top up locally or using en-route charging when travelling on longer journeys.

We set out the current number of chargepoints and forecasts for the sector’s likely required growth in chapter 3, before exploring the development of the 5 segments in chapter 4, chapter 5 and chapter 6. The rest of this chapter provides an overview of other factors relevant to the sector and its development.

Charging and the electricity system

Chargepoints need to be connected to an electricity supply to charge EVs and as EV take-up increases over time, so will demand on the electricity system.[footnote 19] The system will therefore need to have sufficient generation, storage and network capacity. When charged overnight or for longer periods of time EVs can also provide flexibility to the electricity system - by charging more slowly or even providing energy when it is scarce and providing other flexibility services like managing load on local distribution networks.[footnote 20] Chargepoints are connected to the electricity network which both transmits and distributes electricity. Transmission refers to the high voltage system that crosses the country, distribution refers to the lower voltage local networks that provide electricity to all but the biggest customers.

The electricity system is regulated by Ofgem in Great Britain and Uregni in Northern Ireland. Distribution network operators (DNOs) are licensed companies which manage the local electricity infrastructure for homes and businesses. DNOs are critical players in the EV charging sector as they help to facilitate the installation of chargepoints by making new connections and reinforcements to the electricity network when additional capacity is required. In some cases, the cost of these connections and reinforcement can be substantial (see chapter 3 and chapter 4, but this varies significantly between areas depending on different factors.

Ofgem and Uregni play an important role in supporting the development of the EV charging sector through the incentives given to DNOs to deliver the necessary investment (including price controls – see chapter 3). We note that Ofgem will be publishing its high-level priorities to ensure that regulation can play a key role in enabling the transition to EVs at pace and ensure that consumers benefit from the shift. Ofgem will also identify priority actions it should take to support EV take-up and deliver its objectives in this area. Earlier this month Ofgem published its consultation on its minded-to proposals in relation to network connection costs. Currently customers seeking a large new or modified connection to the electricity network have to contribute towards the reinforcement costs needed to facilitate this. Ofgem is seeking views on whether to reduce or remove this cost.

Ofgem announced in May 2021 that as part of its Green Recovery Scheme it would invest £300m in over 200 low carbon projects in electricity distribution and transmission (through funding for DNOs) ‘to get Britain ready for more electric transport and heat’. This includes new infrastructure such as cabling and sub-stations to support 1,800 new ultra-rapid chargepoints at MSAs as well as for chargepoints to be installed in towns and cities across Britain.[footnote 21]

Developments in technology

Developing technologies are expected to improve the functionalities of EVs and chargepoints and significantly impact how consumers engage with the charging sector in future.

Notably smart charging has significant benefits: it can save consumers money and help manage demand on the electricity system, which will be increasingly important as the number of EVs increases. Smart charging allows EV charging to be intelligently controlled, so the charging occurs when the electricity network has surplus capacity or there is less demand (such as overnight) and electricity is cheaper. Smart chargepoints can currently be used for home and workplace charging, though in future it could potentially be deployed in other segments such as on-street. This would reduce the cost for consumers of using on-street charging and have wider environmental and electricity system benefits.[footnote 22]

There are also other, emerging technologies and innovations that are still in the early stages of development such as solar forecourts, ground-embedded chargepoints and wireless charging (embedding charging infrastructure in the roadside). Vehicle-to-grid (V2G) is also an important emerging technology that can enable EV batteries to store energy and discharge it back to the network when this is most needed, helping to manage the load on electricity distribution networks and make savings or earnings for consumers.[footnote 23] ‘Plug and charge’ – technology which enables drivers to initiate automatic payment by connecting their EV to a chargepoint - can also help to simplify aspects of the charging experience (see also chapter 7). In the longer-term other technological developments such as the evolution of autonomous vehicles may also impact the nature of charging, for example robotic charging systems automating the connection between the vehicle and the chargepoint.

Such changes could significantly impact how the sector develops. While they may be beneficial to the sector and the consumer experience of charging, they also create some uncertainty about how and where charging will take place in the future.

Chargepoint operators and private investment in the sector

Recent years have seen a significant expansion in companies entering the sector and an increase in the level of private investment. Chargepoints are provided by commercial entities known as chargepoint operators. There is a wide range of chargepoint operators, some of which are active across the sector (for example, by providing chargepoints at different speeds in different segments) and some of which focus on particular segments.

To install chargepoints, operators need to engage with site owners who procure and contract for chargepoints. Site owners can include homeowners and landlords, retailers, other types of businesses, MSA operators and local authorities (LAs) who are responsible for local roads, parking and street furniture like lampposts (particularly relevant to on-street charging).

Chargepoint operators can have different business models. Currently the main models in public charging are:[footnote 24]

- full operator: the chargepoint operator funds the infrastructure and charges EV drivers directly. The site owner is paid a rent and/or a proportion of the revenue from charging

- service provider: the chargepoint operator provides the chargepoint for a fee. It then manages the operation, payments, servicing and data collection. The host takes any revenue from charging

- concession: this approach is similar to full operator, except the infrastructure is funded largely through Government grants (see next section). This is the model widely used by LAs in on-street charging

In home charging, the main business model is a one-off purchase by the consumer of hardware and installation from a provider, with the contract for electricity supply to the chargepoint being separately provided to the consumer by the home energy supplier. Models for workplace charging can be a combination of hardware and software but may also include ongoing services like data processing and electricity supply.

As highlighted above, in public charging chargepoint operators generally only recoup the costs of their investment when their chargepoints are used. This can be risky at this early stage of the sector when EV take-up is fairly low (albeit increasing) and given ongoing uncertainties around people’s charging preferences and behaviours and developments in technology. These factors, among others, can mean some charging segments have lower utilisation levels than others. Therefore, the payback period for the initial investment can be relatively long (historically this has been potentially between 6 to 9 years, though it is expected to vary depending on the segment and business model).

Low demand and these uncertainties have also historically impacted the type of private sector investment attracted to the sector to date. These factors have made it difficult for infrastructure and pension funds seeking stable low-risk long-term investments. The sector has also been less attractive to private equity or venture capital funds seeking short to medium-term returns before exiting the sector.[footnote 25] Therefore investment to date has mainly been corporate venture capital from large vehicle manufacturers or energy suppliers.

Private investment to date has largely focused on where demand and returns have been strongest - home and workplace charging, and fast/rapid charging.[footnote 26] Private investment has been weaker in parts of en-route (ie along motorways and in remote areas) and in on-street charging, where it can be more difficult and costly to roll-out charging. We explore these barriers in chapter 4 and chapter 5.

The UK Government’s recent commitment to end the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030 has provided reassurance on EV take-up and significantly reduced the investment risks. While the pace of take-up remains a risk, a number of chargepoint operators we spoke to emphasised that the shift to EVs had become a matter of when, rather than if, it happens. We note that there has also been some recent activity from private funds in the sector.[footnote 27]

In addition to chargepoint operators, established commercial players in infrastructure and transport are increasingly moving into the EV charging sector, often through partnering with chargepoint operators and/or through acquisitions. To date this includes: oil and gas providers seeking to take advantage of their existing forecourt presence (e.g. BP, Shell, Total);[footnote 28] energy companies seeking to take advantage of their networks and expertise in electricity generation and supply (e.g. EDF, Centrica, Ovo, E.ON, Engie)[footnote 29] and car manufacturers (eg Tesla[footnote 30] and Ionity[footnote 31]).

Policy approach and public funding

UK-wide

The UK Government has identified the decarbonisation of road transport - including the successful transition to EVs - as key to achieving its legally-binding commitment for Net Zero by 2050. It is providing significant support and funding to help the charging sector as set out below.

In November 2020, the UK Government published a Ten-point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution which announced it was ending the sale of new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030 (brought forward from 2040). It also published a National Infrastructure Strategy (NIS), which outlined its approach to the roll-out of EV charging. This approach has been to maximise private investment into the sector, however, while the sector is developing and the availability of charging infrastructure is a barrier to EV take-up, the UK Government has committed to invest £1.3bn to support EV charging infrastructure roll-out in the 2020 Spending Review.

Earlier this month the UK Government published its Transport Decarbonisation Plan. The Plan emphasised the need for ‘an extensive network of charging and refuelling infrastructure’ and the Government’s support for the development of a market-led charging network. As the sector grows, the Government has committed to increasingly focus its efforts ‘on putting in place a policy and regulatory framework that supports increased investment and competition whilst meeting the needs of consumers’.

Alongside this, it published a 2035 Delivery Plan to help reach the 2030 phase out date for petrol/diesel cars and vans. This set out a number of commitments to accelerate EV infrastructure roll-out, including plans to publish an EV Infrastructure strategy later this year, which will set out its expectations for the roles that industry and government will play in delivering EV charging.

The UK Government has also introduced a number of UK-wide grant schemes and funds.[footnote 32] Alongside a sector-wide fund, grants have focused largely on home and workplace charging, with some grant funding also being available for on-street charging roll-out. The main current schemes are set out in Table 2. In the NIS the UK Government committed to extend these existing grants (subsequently confirmed as to the value of £275m in the 2020 Spending Review.

Table 2: Overview of UK-wide public funds and grants [footnote 33]

| Grant | Focus | Overview | Value to date £’Millions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charging Infrastructure Investment Fund (CIIF) | Sector-wide | Announced in the Budget 2017, a 50:50 public-private investment fund focused on charging infrastructure. It has a 10-year life span to 2030. All of the funds must support investment in public charging. The Fund is managed by Zouk capital and to date it has invested in 3 UK companies: InstaVolt, Liberty Charge (a joint venture with Liberty Global), and EO Charging. | 400 |

| Electric Vehicle Homecharge Scheme (EVHS) | Home charging | EVHS launched in 2015 (replacing a device grant scheme which was in place since 2013) and provides part funding for up to 75% of the installation cost of home chargepoints. As at April 2021 the grant covers up to £350 per chargepoint (conditions apply). The grant rate has reduced over time (from £950 in 2015). Over 135,000 home chargepoints installed via EVHS. | 69+ |

| Workplace Charging Scheme (WCS) | Workplace charging | WCS launched in 2016 and is a grant designed to help organisations implement EVs into their fleets, staff cars or simply to encourage employees to purchase electric vehicles and charge them at work. Funding provided for over 4,000 businesses to date. As at April 2021 the grants covers up to £14,000 (£350 per chargepoint) (conditions apply). | 6+ |

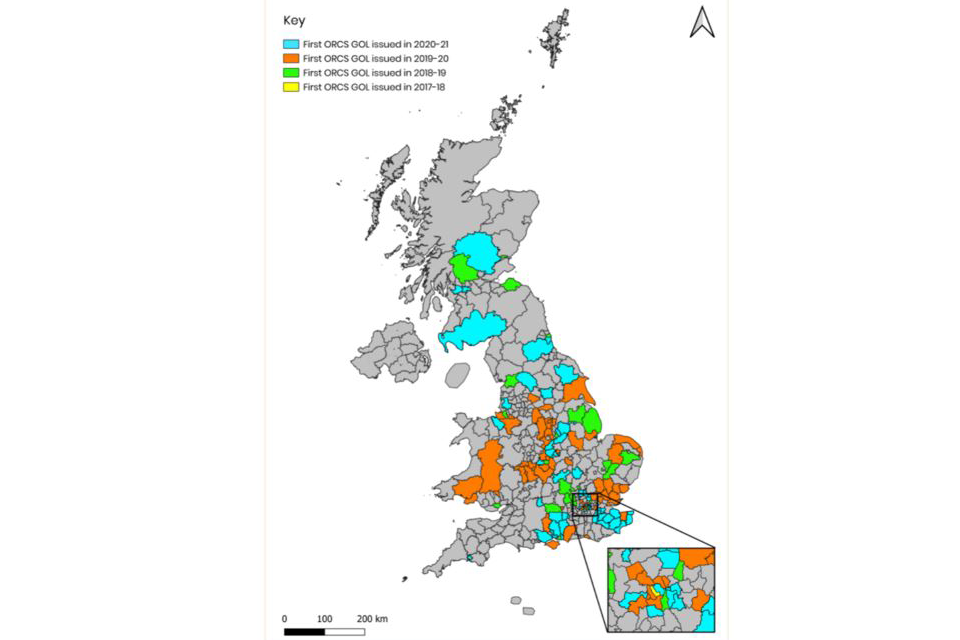

| On-street Residential Charging scheme (ORCS) | On-street charging | ORCS launched in 2017 and provides up to 75% of hardware and installation costs to LAs for on-street and rapid charging. Delivered over 600 chargepoints to date with funding awarded for over 3,000 to be installed in future. It has a fund of £20 million for 2021/2022. | 20 (2021/22) |

In June 2021, the UK Government announced the launch of the UK Infrastructure Bank. The bank’s strategic objectives are to help tackle climate change, and to support regional and local economic growth. Its operating principles include ‘prioritis[ing] investments where there is an undersupply of private capital’.

In addition to providing public funding for the sector, the UK Government is also stepping in to support the sector’s development in other ways. It will be regulating later this year to improve the consumer experience of using public chargepoints, following a consultation by the Office for Zero Emission Vehicles (OZEV).

The UK Government has also set out its aim to maximise the use of smart charging. It recently announced plans to mandate smart charging capability for all new home and workplace chargepoints in Great Britain later this year.[footnote 34],[footnote 35] It is also consulting on proposals for all new-build homes and workplaces to be fitted with smart chargepoints.

Transport policy is also partly devolved and therefore there is some variation in approach to the roll-out of EV charging and to public funding in the nations.

Approach in the nations

In England, the approach has reflected the UK Government’s focus on encouraging and leveraging private sector investment to build a comprehensive network of chargepoints.[footnote 36] There are currently over 50 chargepoint operators and charging networks within England, covering the overall sector and operating within particular segments.

To date, the UK Government has committed various funds to support chargepoint roll-out in England, including commitments in the NIS for additional funding for en-route and on-street charging. A £950m Rapid Charging Fund will fund upgrades to the electricity network to help meet future demand for chargepoints on MSAs and key A road locations where the costs of chargepoint installation are prohibitively expensive and uncommercial. Working with the private sector, it aims to ensure at least 6 rapid/ultra-rapid chargepoints at all MSAs in England by 2023, with a longer-term target of 6,000 along the entire Strategic Road Network in England by 2030. As well as committing additional funding in the 2020 Spending Review for home, workplace and on-street charging schemes (as noted above), a new £90m Local EV Infrastructure Fund will support the roll-out of large local on-street charging schemes and rapid charging hubs across England.

In Scotland, the Government has taken a different approach by setting up a national public charging network. Since 2011, the Scottish Government has spent over £45m to establish and roll-out ChargePlace Scotland.[footnote 37] The majority of public chargepoints in Scotland are connected to this network. Most public chargepoints are currently free to use, with a single back-office provider (currently SWARCO, until 2023) secured through a tender process run by Transport Scotland. Public charging has generally been free of charge in Scotland (we consider the implications for the different policy approaches for chargepoint roll-out in chapter 3).

In November 2020, the Scottish Government launched the Scottish National Investment Bank, which provides long-term investment for a number of purposes including supporting Scotland’s transition to Net Zero. The Scottish Government has also implemented its own grant schemes in addition to the UK-wide schemes to support chargepoint roll-out. These include its Switched on Towns and Cities Challenge Fund and the Local Authority Installation Programme, in which the Scottish Government (through Transport Scotland) invested £21m in 2019 to support EV charging. Funds are offered to all LAs in Scotland to install with a condition of the grant that chargepoints are on the Chargeplace Scotland network. An additional grant to the EVHS and WCS is available for home and workplace charging in Scotland. [footnote 38]

The Welsh Government published its EV charging strategy in March 2021. [footnote 39] Covering the period to 2030, the strategy estimates the need for up to 55,000 fast chargepoints and 4,000 rapid chargepoints and has allocated £30m to be spent by 2025. The strategy will be supported by an action plan to track and manage delivery, which will be monitored and reviewed annually. The Welsh strategy promotes a private sector led roll-out while addressing gaps in provision (particularly in rural areas) through a competitive tender for rapid chargepoint provision. The Welsh Government is rolling out the first round of grants and tasked Transport for Wales to deliver 12 rapid chargepoints at strategic locations, which it is doing through £2m of funds to procure a suitable chargepoint operator. The Welsh Government, as stated in its new Programme for Government, is to launch a new 10-year Wales Infrastructure Investment Plan for a zero-carbon economy and is setting a new target of 45% of journeys by sustainable modes by 2040.

Northern Ireland is at an earlier stage in developing its approach. Since 2014 there has been limited private investment in charging due to restrictions on the maximum resale price of electricity, and planning legislation also made it difficult to repair and replace broken chargepoints. Both barriers have recently been removed, as of March 2020 and December 2020 through legislative amendments, respectively.

All public chargepoints in Northern Ireland are currently free to use and are operated and maintained by a single private provider, Electricity Supply Board (ESB) which is currently in the process of upgrading older chargepoints. The Department for Economy is consulting on an Energy Strategy to decarbonise the energy sector by 2050 at least cost to the consumer. The draft strategy proposes the development of an EV Charging Infrastructure Plan to ‘support the upgrade and extension of the [charging] network’. It also recognises that the private sector will have a role to play in EV charging roll-out and aims to remove further barriers to the commercial viability of EV charging.

Recognising the differences in approach across the nations has been a key consideration in our study. As highlighted, the policy approach in each nation has had implications for the levels of private investment and the scale of roll-out, which we consider in chapter 3. We consider specific differences in investment, competition and consumer engagement in the sector throughout our report.

Regulatory framework

There are some regulatory requirements in place for the operation of EV chargepoints - the Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) sets and enforces compliance with product and installation standards for chargepoints. The installation and other operational aspects of chargepoints are not currently regulated. As set out earlier, the electricity supply in the UK is regulated by Ofgem and Uregni.

There are 2 key pieces of UK-wide legislation relating to the sector. The Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Regulations 2017 (AFIR) applies to public chargepoints – covering technical specification and consumer experience standards. [footnote 40] Through the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 (AEVA), the Department for Transport (Secretary of State) has powers to improve the consumer experience, ensure provision at key strategic locations and require that all connections are smart. Secondary legislation is required for UK Government to introduce these changes.

3. Scale of the challenge facing the EV charging sector

- While it is difficult to know precisely how much charging that will be needed, estimates suggest an additional 280,000 – 480,000 public EV chargepoints will need to be installed by 2030 to meet anticipated demand. This is more than 10 times the size of the current network - currently about 25,000 public chargepoints.

- There are a number of factors which explain why market forces alone will struggle to deliver the pace and type of EV charging infrastructure needed to meet the UK Government’s greenhouse gas reduction targets.

- These factors include the cost of changing from a fossil-fuel based transport system to an electricity-based system (such as new network connections/upgrades), the cost of carbon pollution, the ‘chicken and egg problem’ of interrelated demand for EVs and charging infrastructure, and the spillover benefits EVs could have to the electricity system (eg when plugged in for an extended period of time, EVs can help balance changing demand and supply patterns).

- As a result, even greater active government involvement both at local and national level will be needed to provide a comprehensive EV charging network that is competitive and consumers can trust. DNOs must also play their part to ensure that new charging infrastructure can be connected efficiently and rapidly.

- We recommend that the UK Government puts in place an ambitious National Strategy for EV chargepoint deployment between now and 2030, alongside strategies from each of the Devolved Administrations – building on the work already underway across the nations.

- We also recommend Ofgem/Uregni use forthcoming price control reviews to strengthen DNO incentives to speed up EV charging grid connections, invest strategically in network reinforcement and lower new connection charges by removing the charge for any reinforcement costs.

Introduction

In order to meet the government’s carbon reduction targets and enable switching to EVs ahead of the planned 2030 prohibition on sales of new petrol and diesel cars/vans, there needs to be a comprehensive network of chargepoints at home, on residential streets, at destinations such as supermarkets, workplaces and on the road network for en-route charging.

The opportunity of a major increase in demand for EV charging, supported by government funding, have driven investment, entry and emerging competition. However, the pressing need to deploy charging networks rapidly and overcome several significant barriers to investment and competition means that market forces alone will struggle to deliver. Therefore, active government involvement in the EV charging sector is essential to deliver a comprehensive network within this challenging timeframe.

This chapter is structured as follows:

- Why EV charging is important;

- Progress of roll-out to date;

- Significant growth needed in the sector;

- Broad factors impacting EV charging roll-out; and

- Measures to meet the overall challenges facing the sector

Why EV charging is important

The transport sector is responsible for more of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions than any other sector in the economy, accounting for 27% of total emissions in 2019 according to BEIS. [footnote 41] Two-thirds of emissions in this sector are from the use of petrol and diesel in road transport, particularly from cars and taxis. [footnote 42]

Decarbonisation of road transport is therefore vital to the achievement of the UK’s longer-term Net Zero goals. The UK has also committed to achieving substantial emissions cuts in the medium-term, reducing greenhouse gas emissions in 2035 by 78% compared to 1990 levels. [footnote 43] Transport is considered to be one of the easier sectors to decarbonise, and so will be responsible for a substantial proportion of these medium-term reductions.

While other technologies, such as hydrogen fuel cells or biomethane, continue to be developed for specialised road transport applications, recent falls in the cost of battery technology mean that a low carbon road transport system is likely to be almost entirely powered by electricity. This system will also require a comprehensive network of EV chargepoints throughout the UK, allowing drivers to charge their vehicles easily and conveniently.

Progress of roll-out to date

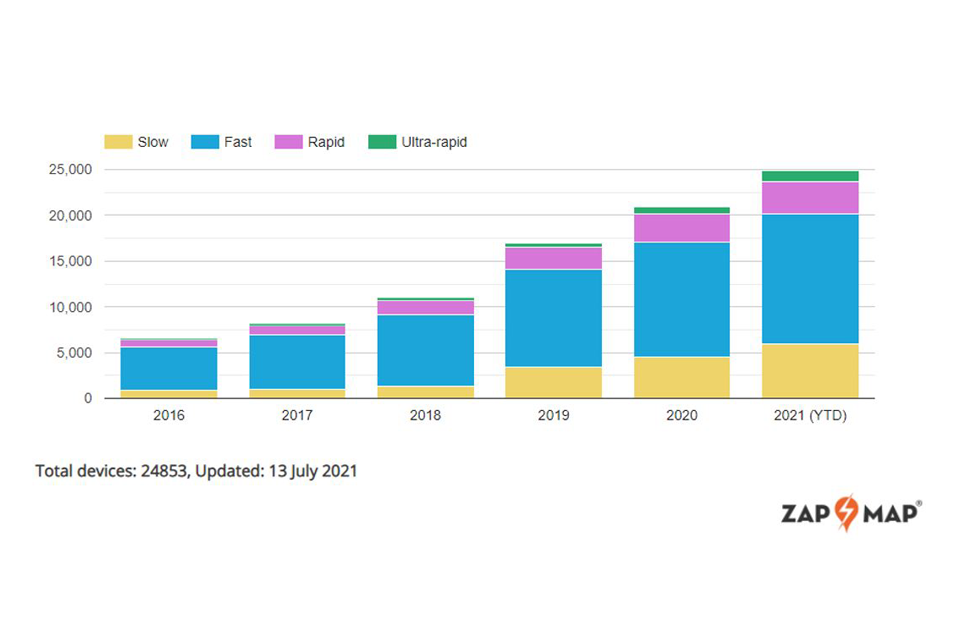

The current EV public chargepoint network

Figure 1 shows the yearly figures for the number of public chargepoints by charging speed from 2016 to June 2021. Over the period 2016 to 2020 the number of chargepoints has more than tripled, from over 6,000 to more than 20,000. To date, there are almost 25,000 public chargepoints. The growth rate over the period has increased year on year with the exception of 2020 when COVID-19 affected the ability of chargepoint operators to roll-out new chargepoints. In 2020 only 4,173 new chargepoints were installed, an increase of just 25% on the prior year. This compared with 5,737 new chargepoints in 2019, an increase of 52% on the prior year.

Figure 1: Number of public charging points by speed 2016 to date (13 July 2021)

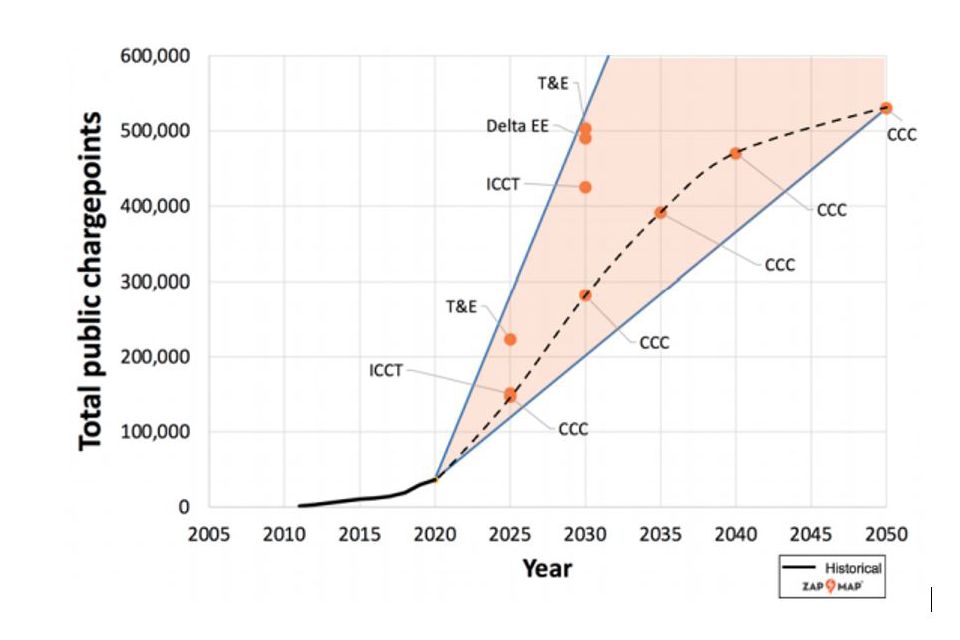

A graph showing the estimated forecasts on the number of chargepoints that will be required to service the growth in EVs drawing on four sources. It estimates that between 280,000 - 480,000 chargepoints will be needed by 2030.

Source: Zap-Map, 13 July 2021.

The geographical distribution of public chargepoints across the UK is however very uneven, with significant differences between the nations, regions and local authorities.

Figure 2: Public chargepoints per 100,000 of population by UK country and region

""

Source: Electric vehicle charging device statistics: April 2021.

Figure 2 shows that for the UK overall there were on average 34 public chargepoints per 100,000 people. However, there are wide variations between nations - in Scotland there were 43 per 100,000 people while in Northern Ireland there were only 17 per 100,000 people. There is also a significant variation within different English regions, for example with the figure for London being 4 times that of Yorkshire and the Humber.

There is also variation in chargepoint distribution between LAs. For example, in Scotland, Dundee has a ratio of 80 chargepoints per 100,000 people but Edinburgh only has a ratio of 24. Similar variations can be found across LAs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. We discuss local variations further in chapter 5.

These figures all show that while there has been significant growth in the number of public chargepoints, this growth has not been uniform across the UK.

Home and workplace charging

There are currently over 170,000 home chargepoints across the UK installed through the UK Government home chargepoint grants schemes (EVHS and DRS - see chapter 2. Estimates suggest that home chargepoints will need to increase to almost 6 million by 2030. [footnote 44] Last year around 40,000 home chargepoints were installed under the EVHS grants scheme. To meet the projected numbers this needs to increase significantly, and the rate of installations is to expected to grow as the number of EVs sold increases. OZEV measures the uptake of home chargepoint grants and is currently forecasting that 5% of UK homes with eligible off-street parking will have received a grant by 2025. In England alone, this equates to around 800,000 homes with chargepoints out of 16 million homes that have off-street parking. [footnote 45] This figure excludes home chargepoints that are not eligible for a grant (ie dumb chargepoints) and so is likely to be an underestimate.

There are over 13,000 sockets for workplace charging installed through the Government grant scheme (WCS – see chapter 2) in the UK. There are no national statistics on the number of workplaces with parking spaces or a breakdown of those parking spaces. However, in the UK, more than two-thirds (68%) of people in employment travel to work by car (driver and passenger) which equates to 21.4 million people. [footnote 46] Of those who drive to work, 70% report that they park in workplace car parks. [footnote 47] This suggests that charging at work will increase markedly over time. Estimates suggest that the number of work chargepoints will be up to 1.4 million by 2030. [footnote 48] OZEV considers that the number of workplace chargepoints will continue to increase, driven by EV uptake and future changes in legislation, such as UK Government proposals to require businesses in England with carparks that have over 20 spaces to install chargepoints.

How the UK compares to other countries

As shown in Table 3, as at December 2019 the UK had the fourth largest EV charging network (after France, Germany and the Netherlands). [footnote 49]

Table 3: Number of chargepoints by country (as of December 2019)

| Country | Total number of public chargepoints [1] | Public chargepoints per 100,000 people | Rapid chargepoints (22-100kW) per 100,000 people | Ultra-rapid chargepoints (110kW+) per 100,000 people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 43,730 [2] | 248 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Germany | 32,704 | 39 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| France | 29,538 | 44 | 2.6 | 0.9 |

| UK | 24,445 | 36 | 6.1 | 0.7 |

| Norway | 12,300 | 228 | 36.6 | 9.2 |

Source: Delta EE, CMA analysis [1] Data is taken from the European Alternative Fuels Observatory and cannot be directly compared to chargepoint data in other sections of the report as it is compiled from different sources [2] The Netherlands counts workplace chargers/hotels etc as ‘public’ even when they are not necessarily fully available to anyone who needs to charge, and this inflates its figures by approximately 18,000, according to Delta-EE.

Policy approaches vary between countries, with some countries taking a regulation-led approach. For example, the German Government has stated its intention to mandate EV chargepoints in all German petrol stations. The French Government, similarly to the UK Government, operates a grant system for EV chargepoints and in the Netherlands the Central Government provides different forms of support to help Local Governments with their local vision for EV charging. [footnote 50] With incentives in place for EV car ownership for many years, Norway has one of the most mature EV charging sectors. The Norwegian Government has drafted ambitious plans for EV charging infrastructure which falls to local authorities to carry out. [footnote 51]

EV charging sectors in most countries are in their infancy, therefore it is too early to tell whether particular policy approaches will be more or less successful in the long-term. While the UK’s charging network is growing, its roll-out is not as progressed in some respects as some other European countries – Norway and the Netherlands have over 5 times as many chargepoints per 100,000 than the UK, though the UK has on average the highest density of fast chargepoints on key strategic roads per 100km. [footnote 52] However, it is clear from our discussions with other competition authorities that all countries face similar challenges in providing the necessary charging infrastructure for the rapidly increasing numbers of EVs.

Significant growth needed in the sector

As set out in the progress of roll-out to date section, the UK’s public charging network has grown substantially since 2016. However, it is currently only a small fraction of the size it needs to be by 2030. Estimates set out below suggest the UK will need between approximately 280,000 to 480,000 chargepoints by 2030 – using the midpoint this would be at least 380,000 chargepoints. However, there are many uncertainties around the likely numbers that will be needed and therefore these are illustrative rather than precise forecasts.

The Committee on Climate Change (CCC) is an independent, statutory body whose purpose is to advise the UK and devolved governments on emissions targets, including the UK’s carbon budgets. We have used the CCC’s forecasts of public chargepoints as an authoritative source for our work, although we note that its forecasts are lower than others. To illustrate the scale of the increase required we have set out in Table 4 a breakdown of the forecast produced by CCC. Under even this forecast the UK needs nearly 12 times the current number of public chargepoints by 2030 - this varies between 6 and 41 times for different chargepoint speeds. This increase equates to nearly 27,000 new chargepoints per year - a similar number to the total installed to date. We note that other forecasts have different estimates of the number of different chargepoint speeds needed and these depend on the assumptions used of how EV drivers recharge.

Table 4: CCC forecast of the number of public chargepoints required

| Chargepoint speed | 2020 (thousands) | 2030 (thousands) | Increase (thousands) | Size of increase 2020-2030 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-7kW | 8.5 | 48.5 | 40 | 6x |

| 22kW | 9.7 | 106.3 | 96.6 | 11x |

| 50kW | 3.0 | 121.7 | 118.7 | 41x |

| 150kW+ | 0.3 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 17x |

| Total | 21.5 | 281.5 | 260 | 12x |

Source: Sixth Carbon Budget - Climate Change Committee (theccc.org.uk) Fig 3.1b Total electric cars on the road and supporting charging infrastructure in the balanced Net Zero Pathway.

The required number, location and speed of public chargepoints in the future is inherently uncertain. It depends on a variety of factors including the rate of EV uptake, EV usage, consumer preferences, future living and working patterns and the evolution of technology (see chapter 2). However, the estimates set out in Figure 3 indicate the overall scale of the likely necessary increase in chargepoints required to meet future EV demand. These projections, while approximate, indicate the substantial scale of the likely increase compared with the progress of chargepoint roll-out to date.

Figure 3: Estimated forecasts for public chargepoints

A graph showing the estimated forecasts on the number of chargepoints that will be required to service the growth in EVs drawing on four sources. It estimates that between 280,000 - 480,000 chargepoints will be needed by 2030.

Source: Policy Exchange, Forecasts from CCC, Transport & Environment, Delta-EE and ICCT - all 2020.

Figure 3 combines various forecasts from the CCC, Transport & Environment (T&E), Delta-EE and ICCT on the number of chargepoints that will be required to service the growth in EVs, which was set out by Policy Exchange. [footnote 53] It shows a range using these 4 forecasts of between 280,000 (CCC) and 480,000 (T&E) chargepoints needed by 2030. Though as noted above, it also illustrates that there remains a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the likely number of public chargepoints required by 2030.

Building a comprehensive public EV charging network will also involve significant financial investment. Slow and fast public chargepoints typically cost between £1,000 and £10,000, while rapid and ultra-rapid public chargepoints typically cost upwards of £25,000 just to install, excluding additional commissioning and electricity network connection costs. Taking the CCC’s forecast, the potential cost to meet 2030 forecast chargepoint numbers could be around £3-5bn and under other forecasts it could be as high as £6-10bn (both estimates are before commissioning and network costs). While these estimates are highly uncertain and sensitive to changes in assumptions, they illustrate the scale of the investment challenge.

While highly challenging, we consider that it is important for governments to assess the likely estimated numbers of future chargepoints required to support the uptake of EVs. This will help markets and governments track and monitor progress and identify where there is underinvestment so that future support can be targeted at the parts of the sector that need it most. We understand that further detailed work to model future requirements is being undertaken by EVET. Precise figures or targets will be difficult to formulate but modelling to better understand the likely range, using a variety of assumptions and scenarios, is likely to be informative. As noted above, estimates will vary depending on user needs and preferences, as well as many other assumptions, therefore in considering deployment requirements it will also be important to understand and monitor consumer needs and preferences. Estimates may also change over time therefore it will be important for these to be updated and reviewed regularly.

We also considered how the growth of EVs compares to the growth of the public charging network. Estimates suggest there could be almost 16 million EVs on the UK’s roads by 2030 [footnote 54] (compared to current numbers of over 500,000 in 2021 (including plug-in hybrids)). In 2019 there were almost 100,000 EVs registered in the UK with just under 17,000 chargepoints, equating to one chargepoint for every 6 EVs. By 2020 the number of registered EVs had increased to just over 200,000 [footnote 55] while the number of chargepoints had increased to just under 21,000, with the proportion falling to one chargepoint for every 10 EVs. In 2021, there is approximately one chargepoint for every 21 EVs.

This highlights the challenges facing the sector in keeping pace with the increasing take-up of EVs. Numbers of EVs per public chargepoint (both in relation to number and speed of chargepoints) is also informative of the progress being made towards sufficient chargepoint deployment and therefore will be useful to monitor and track.

Broad factors impacting EV charging roll-out

The EV charging sector has seen significant private investment, competition between chargepoint operators and innovation. This has resulted in a growing network of chargepoints in all segments of the sector. However, as set out in the previous section, the rate of growth in the network needs to increase significantly over the next decade in order to anticipate future demand.

Typically, the prospect of a major increase in demand would be expected to generate a sufficiently large increase investment to meet that demand. There are, however, a number of factors which challenge the ability of the EV charging sector to grow at the rate and develop in a way that is needed to achieve the government’s greenhouse gas reduction targets, which we set out below.

The costs of changing to a low carbon transport system

Moving from a fossil fuel-based transport system to a low-carbon one, predominantly powered by electricity, involves significant interrelated costs. These costs include the direct investment required in EV charging networks, the EVs themselves, and the low carbon electricity needed to power them. System change costs also include the costs of changing consumer behaviour, and costs relating to the electricity system, such as reinforcement costs for reinforcing capacity and the costs of new connections.

These costs typically fall on those companies – such as chargepoint operators and EV manufacturers - involved in the new low carbon system and are then passed on to consumers. This puts their products at a competitive disadvantage compared to those companies operating in the legacy fossil fuel system, whose costs (for example fuel refineries or engine development) are largely sunk.

This cost disadvantage, unless addressed by government intervention, is likely to slow or even prevent the change to a low carbon transport system.

The ‘chicken and egg’ problem - interrelated demand for EVs and charging

In order for drivers to choose an EV, they must be confident that there is a sufficiently large EV charging network for them to be able to charge at home and when out and about. However, when deciding whether to deploy chargepoints, operators need to be confident that drivers will buy EVs and use chargepoints to enable them to make a return on their investment.

This ‘chicken and egg’ problem increases financial risks for both EV manufacturers and chargepoint operators, deterring investment and slowing the growth of charging networks. The problem is particularly acute at present when numbers of EVs and chargepoints are both relatively low. This means that rather than gradually scaling up the infrastructure in proportion with the growth in demand, significant investment will be needed ahead of demand to ensure a sufficient charging network is in place in order to encourage people to make the shift to EVs.

Carbon pollution costs

Carbon pollution costs are rarely taken into account by markets, because the climate change effects of carbon pollution are difficult to connect directly to actions in the market (such as buying a petrol car). This can lead to a bias towards higher carbon transport options, as the cost of pollution is not captured in market outcomes. While the government imposes fuel duty on petrol and diesel, this duty covers other environmental impacts beyond carbon pollution. Although measures such as carbon taxes can help to reflect these pollution costs, other factors such as the cost of switching to a less polluting car such as an EV can dampen the effectiveness of such measures.

Wider benefits of EVs to the electricity system

As the electricity system decarbonises, renewable generation technologies such as wind and solar make up a greater proportion of total generation. Renewable generation is intermittent, and one of the biggest challenges of a low carbon electricity system is managing the system to ensure that there is sufficient flexibility to keep demand and supply in balance.

In addition, as people turn to electricity to power their cars and heat their homes, load on the electricity distribution networks will increase, which could lead to costly network upgrades.

When plugged in for extended periods of time, EVs have the potential to reduce the costs of supplying and distributing renewable electricity. By controlling the speed and time of charging, or being able to supply energy from the EV’s battery to the network, the system operator can more easily balance changing demand and supply patterns, and DNOs can manage local network load in a ‘smart grid’.

If EVs were not available to provide these services, investment would be needed in alternative storage capacity and/or generation capacity, and network infrastructure, increasing the cost of electricity. However, currently only some of these benefits can be easily captured through market signals (such as time of use tariffs) in slower EV charging which provides them.

The importance of electricity networks

In addition, the electricity system will need to be able to support the mass uptake of EVs. Currently the costs of network reinforcement and upgrades for new connections in the UK can weaken the business case for new charging infrastructure. Ofgem is currently consulting on proposed connection charging changes to reduce and in some cases remove the cost of network reinforcement for new connections (including those intended for chargepoints), which should improve investment conditions. [footnote 56]

The cost and complexity of grid reinforcement means that certain locations will be prohibitively expensive to fit charging posts which could act as a barrier to consumer adoption. – E.ON.

There was widespread concern among chargepoint operators that the costs and difficulties of applying for network connections from DNOs can result in significant delays to installing chargepoints – and that a more transparent and timely process would significantly help to facilitate the faster roll-out of chargepoints at scale. For example, one chargepoint operator told us that connecting to the network was much slower in the UK than in other European countries. [footnote 57]

While power itself is not a barrier, the issues around it can create significant cost and cause significant delay to the expansion of infrastructure. With an end to end timeline of around 40 weeks for an average ultra-fast charging site, from feasibility study to commissioning, around 10 weeks of this can simply be waiting for a quote to be returned from a DNO. – bp pulse.

We consider that the external benefits set out in the broad factors impacting EV charging roll-out section of widespread EV adoption to both the transport and electricity systems may not be reflected in the electricity networks’ regulatory and financial incentives, many of which were set several years ago. [footnote 58]

The need for government and regulatory support