Employers’ understanding of the gender pay gap and actions to tackle it: a research report

Published 31 January 2019

Research report November 2017

James Murray, Paul Rieger and Hannah Gorry – OMB Research

Prepared by:

OMB Research

The Stables, Bradbourne House, East Malling, Kent ME19 6DZ

01732 220582

This research was commissioned by the Government Equalities Office (GEO). GEO is responsible for equality strategy and legislation across government. GEO works with the Department for Education (DfE) and as such this research has been published by DfE.

The research was undertaken by OMB Research. We would like to thank all of the private, voluntary and public sector organisations that kindly took the time to participate in the quantitative survey, and those who subsequently provided additional feedback during the qualitative follow-up interviews.

1. Executive summary

1.1 Introduction

The government has recently introduced new gender pay gap (GPG) transparency regulations,[footnote 1] which are designed to encourage large employers to take informed action to close their GPG where one exists. These regulations came into force in April 2017 and affect over 9,000 GB employers across the private, voluntary and public sectors.

This research provides a baseline measure of large employers’ understanding of the GPG and the transparency regulations, and the actions they are taking to close their GPG.

The core research consisted of a telephone survey of 900 large employers (with 250 or more staff), and 30 follow-up qualitative interviews to explore the key issues in more detail. It took place between March and May 2017.

An additional phase of 22 brief qualitative interviews was conducted among employers who had stated an intention to publish their GPG results in quarter 1 2017 but did not upload their data to the portal during this time. This additional research took place in September 2017.

1.2 Understanding of the GPG

Awareness of the term ‘gender pay gap’ was extremely high (98%). Half (48%) of all respondents (typically HR directors or managers) felt they had a good understanding of what the GPG was and how it was calculated, and a further 41% believed they had a reasonable understanding but were not sure of the specifics of how it was calculated. However, the qualitative interviews found that some of those reporting a good understanding could not provide a detailed or correct explanation of the GPG when asked.

Around two-thirds (63%) of respondents (typically HR directors or managers) reported that they had a good understanding of the difference between ‘closing the GPG’ and ‘ensuring equal pay between men and women’. In most cases they were reasonably confident that this knowledge extended to the top levels of the organisation. Over half (54%) believed that their board or leadership team had a fairly good understanding of the GPG and how it differs from equal pay, and a significant minority (17%) felt they had a very good understanding.

In all of the above areas, self-reported understanding was highest among public sector organisations and those with 1,000 or more employees.

The qualitative research suggests that many employers had not engaged with the topic of GPG before the introduction of the new regulations. Therefore, levels of understanding were mixed and somewhat superficial. As mentioned above, some of those claiming a good understanding in the quantitative survey were not able to spontaneously provide a clear or correct definition of GPG. This was typically due to confusion between GPG and equal pay. To clarify, the Gender Pay Gap is a measure of the difference between the average hourly earnings of men and women. In contrast, equal pay deals with the pay differences between men and women who carry out the same work, similar work or work of equal value, and it is unlawful to pay men and women unequally based on their gender.

1.3 Measuring the GPG and other gender analysis

Almost one-third of organisations (31%) had measured their GPG in the previous 12 months, so prior to the new transparency regulations coming into force. The qualitative interviews suggest that many of these employers had done so as a ‘dry run’ in advance of the regulations coming into force, and incidence of ‘true’ voluntary GPG measurement (not driven by the regulations) was low. It should be noted that these employers had not always calculated their GPG in a way that was entirely consistent with the approach mandated in the new regulations.

The proportion of employers that had measured their GPG increased in line with organisation size, ranging from 23% of those with 250 to 499 employees up to 47% of those with 1,000 or more employees. It was also higher in the public sector (40%).

The majority (58%) of large employers had conducted other gender analysis in the past 12 months. The most common other analyses were calculating the proportions of male and female employees at different pay levels (41%), measuring the proportions paid bonuses (31%) and examining the differences in average bonuses paid (24%). Larger organisations with 1,000 or more employees were considerably more likely to have conducted each of these types of gender analysis, as were those that had also measured their GPG.

The results of the GPG or other gender analysis were typically communicated to senior levels of the organisation, with two-thirds (66%) sharing them with the leadership team or board and a similar proportion (62%) sharing them with senior management. This analysis has also prompted employers to take action, with 38% using it to inform or revise their HR practices and 26% developing plans or strategies to address gender issues.

However, relatively few (11%) had communicated or published the results of their gender analysis externally. This finding supports the move to mandate publication of GPG data through the new transparency regulations. It should be noted that public sector organisations were considerably more open in this respect, with 42% having communicated the results externally (compared to 11% of voluntary and just 4% of private sector employers). This may be linked to the Public Sector Equality Duty, which requires public bodies with over 150 employees to report on the diversity of their workforce, as some organisations had published gender pay gap data as part of this.

1.4 Reducing the GPG

Employer attitudes to reducing the GPG varied widely, with 24% allocating it a high priority, 37% a medium priority and 33% a low (or non) priority.

Those treating their GPG as a high priority were typically motivated by moral or ethical considerations, such as a desire to be fair, provide equal opportunities. However, one-fifth (20%) identified the new regulations as the key driver.

Employers that allocated a lower priority to reducing their GPG often did so because they believed they did not have a (large) gender pay gap. However, a significant proportion felt it did not apply because all their workers were already paid equally regardless of gender, suggesting a degree of confusion between GPG and equal pay.

The qualitative research found that although there was a wide range of attitudes towards GPG, the fact that it was often ‘new’ to employers and had not been given much consideration to date meant that a somewhat passive mindset was common. Many of the interviewed employers were waiting until they had measured and analysed their GPG data before thinking in detail about whether and how to address any gap.

Reflecting this, the majority of employers had not yet developed any plans to reduce their GPG, with 50% intending to do so but 20% having no intention to take any action. While one-fifth (21%) had developed a formalised GPG plan, only 6% had already undertaken any of the actions in this plan. The proportion that had already developed a formal plan was highest among 1,000 or more employee organisations (34%).

However, the qualitative interviews found that few of these plans had been put in place specifically to address GPG. They either related to broader gender equality strategies (not developed with GPG in mind) or referred to a range of ad hoc measures implemented for various purposes (for example, increasing staff retention, attracting more female staff).

The most common measures included in these action plans were offering or promoting flexible working (71%) and promoting parental leave policies that encouraged both men and women to share childcare (65%). Half (51%) involved trying to change the organisational culture and over one-third included voluntary internal targets (39%) and women-specific recruitment, promotion or mentoring schemes (35%).

There appeared to be some reluctance to publicise GPG reduction measures, with only one-third (33%) of those that had or intended to develop a plan indicating that they would publish this externally (for example, on their website, in their annual report).

The greatest perceived barrier to reducing the GPG was difficulty attracting women to the organisation or to certain roles, with 14% mentioning the challenge of recruiting or promoting women, 10% highlighting the male-dominated nature of their sector and 5% identifying the fact that women do (or apply for) different types of job. These issues were most prevalent in the construction, manufacturing and financial sectors.

1.5 The GPG transparency regulations

Awareness of the new GPG transparency regulations was high (88%). In terms of knowledge, over half (54%) stated that they understood what was required and how to do it, and a further fifth (20%) felt that they knew what was required but were uncertain of how to go about it. The level of understanding increased in line with organisation size.

Perhaps reflecting the fact that they still had a year before the GPG reporting deadline, half of employers had done relatively little preparation by the time of the survey (30% had reviewed the requirements but nothing more, 7% had not thought about them at all, and 11% were unaware of them). The remainder believed they were already in a position to meet the regulatory requirements (17%) or had developed a plan for how they would do so (32%).

The larger the employer, the more likely they were to have prepared for the regulations. 60% of those with 1,000 or more employees reported that they were already able to meet them or had drawn up a plan, compared to just 42% of those with 250 to 499 employees.

Readiness was also greater in the public sector, with 62% of these organisations able to meet the regulations or with a plan in place to do so.

Generally, those employers interviewed in the qualitative stage regarded complying with the regulations as a high priority, usually because it was a legal requirement and they were keen to avoid penalties. However, although important, they did not see it as an urgent matter (due to the reporting timescales). As such, they tended not to have firm timetables in place for the compliance process and these tasks were often fitted in around other commitments.

If employers needed assistance in complying with the new GPG transparency regulations, most stated they would contact Acas (30%), a legal professional or advisor (30%), an external consultant (23%) or GEO (17%). Over half (59%) had already read the GEO and Acas guidance on GPG reporting.

The most widely mentioned types of support required were guidance on how to report their GPG (19%) and on how to measure their GPG (18%). However, one-third of employers (32%) did not feel they would need any external assistance, and the qualitative research suggests that most employers found the process of collating data and making calculations to be straightforward. It should be noted that employers were yet to tackle the reporting and interpretation of their GPG data, which was anticipated to be the most challenging aspect.

The majority (57%) of employers had not yet decided on a publication date. Many of the qualitative interviewees indicated they were delaying publishing their gender pay data until others had done so, in order to see how other organisations presented and explained the data.

The quantitative survey was conducted in March and April 2017, and at this point a significant proportion of employers intended to publish their GPG data much earlier than the April 2018 deadline, with 18% planning to do so in the first 2 quarters of the 2017 to 2018 financial year. However, it should be noted that the proportion of employers who actually went on to report their results in this time period was significantly lower than implied by the survey results. The initial qualitative research found that employers’ publication plans were not set in stone, which may explain the lower than expected rate of early reporting. Most interviewees described general ambitions, rather than set dates, and there was evidence of these being pushed back in response to other priorities.

Further qualitative interviews among employers that had intended to publish in the first quarter of the 2017 to 2018 financial year confirmed that other issues or tasks had often taken priority over early compliance with the GPG regulations. In addition, these interviews found that some employers had found the process more involved than expected, others had delayed their activity due to circumstantial factors such as restructuring of the organisation or delays in receiving data from third party payroll systems providers, and a few had published their GPG results on their own websites but not on the government portal.

Just 1 in 5 employers intended to publish any additional information alongside the mandatory reporting, and in most cases this was a narrative commentary on the results (15%). Private sector organisations were least inclined to go beyond the basic requirements, with 83% either not planning to produce additional information or unsure as to whether they would do so.

A minority of organisations intended to adopt a comprehensive and active approach to communicating their GPG results (16% for employees and 11% for external stakeholders). However, most either indicated that this would depend on the results or were unsure as to their communication strategy.

2. Introduction

This report provides the findings from a study commissioned by the Government Equalities Office (GEO) and carried out by OMB Research. The research provides evidence on large employers’ understanding of the gender pay gap (GPG), the action they are taking to close it, and their response to the new GPG transparency regulations.

The research used both quantitative and qualitative methodologies and was conducted between March and May 2017.[footnote 2]

2.1 Background

The government has committed to eliminate the gender pay gap within a generation. The GPG is an overall measure which reflects differences in median[footnote 3] hourly earnings and labour market participation by gender. Currently the overall gender pay gap for all employees (18.1%) is the lowest since records began.[footnote 4]

Employers are well placed to tackle many of the issues that drive the GPG. In 2011, the government launched the Think, Act, Report initiative, a set of principles and suggestions on how to improve gender equality in the workplace. While over 300 businesses signed up to Think, Act, Report only a small proportion of these voluntarily published gender pay gap information.

New regulations introducing mandatory gender pay gap reporting for large employers should encourage employers to take informed action to close their GPG where there is one. These regulations came into force in April 2017 and require private and voluntary sector organisations with 250 or more employees to publish GPG statistics every year. The same requirements have been introduced for public sector organisations in England (and non-devolved authorities operating across Great Britain) by amending the Specific Duties regulations made under Section 153 of the Equality Act 2010.

The Government Equalities Office (GEO) commissioned OMB Research to develop a robust research programme to provide a baseline measure of large employers’ understanding of the GPG and the transparency regulations, and understand the actions they are taking to close their GPG.

The primary aims of the research were:

- to provide insight on employers’ understanding of the GPG, including current levels of awareness of the GPG, understanding of the transparency regulations, ability to interpret GPG statistics and understanding of the factors that influence their GPG

- to understand how employers are planning to comply with the regulations, including when they plan to publish their statistics and what support employers think they need to be compliant

- to gather detail on the actions employers are planning or taking to address their GPG and employers’ experiences of taking action

- to understand the perceived barriers to taking action

The core elements of this research took place between March and May 2017, so coincided with the introduction of the new GPG transparency regulations. We acknowledge that there was therefore heightened attention on GPG at the time of the survey, but do not expect this to have had a significant bearing on the results.

2.2 Methodology

The research consisted of a quantitative survey of large employers, supplemented by qualitative depth interviews with a selection of those interviewed in the main survey.

Quantitative survey

Telephone interviews were conducted with 900 large employers between 10 March and 28 April 2017, and covered private, voluntary and public sector organisations with 250 or more employees. Interviews lasted an average of 22 minutes and were conducted with HR directors or managers or other senior staff able to talk about their organisation’s strategy in relation to gender pay differences. The survey communications positioned the research as focusing on gender in the workplace but did not specifically reference GPG.

The sample was provided by the Office for National Statistics and was sourced from the Inter-Departmental Business Register (IDBR), which has comprehensive coverage of large employers. All employers in Northern Ireland, and public sector organisations in Scotland and Wales, were excluded from the sample as they are not subject to the GPG transparency regulations.

Quotas were set on broad sector, size band and Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code to ensure good coverage of the large employer population. While these quotas were largely representative of the target population, the voluntary and public sectors were over-sampled to allow robust sub-analysis. For example, voluntary sector organisations account for 13% of the large employer universe but made up 27% of the interviews conducted. This resulted in statistical confidence intervals of:

- plus or minus 4.7% for the private sector

- plus or minus 5.6% for the voluntary sector

- plus or minus 5.5% for the public sector[footnote 5]

Table 1 sets out the profile of all large GB employers subject to the GPG transparency regulations, and the profile of the achieved interviews.

Table 1: Universe and achieved interviews by sector and size

| Sector | Size | Universe (ONS data): number | Universe (ONS data): % | Interviews: number | Interviews: % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 250 to 499 employees | 3,659 | 39% | 192 | 21% |

| Private | 500 to 999 employees | 1,801 | 19% | 113 | 13% |

| Private | 1,000 or more employees | 1,651 | 17% | 101 | 11% |

| Private | Sub-total: Private | 7,111 | 75% | 406 | 45% |

| Voluntary | 250 to 499 employees | 611 | 6% | 133 | 15% |

| Voluntary | 500 to 999 employees | 303 | 3% | 55 | 6% |

| Voluntary | 1,000 or more employees | 282 | 3% | 55 | 6% |

| Voluntary | Sub-total: Voluntary | 1,196 | 13% | 243 | 27% |

| Public | 250 to 499 employees | 412 | 4% | 87 | 10% |

| Public | 500 to 999 employees | 212 | 2% | 46 | 5% |

| Public | 1,000 or more employees | 533 | 6% | 118 | 13% |

| Public | Sub-total: Public | 1,157 | 12% | 251 | 28% |

| Total | 9,464 | 100% | 900 | 100% |

Overall, 91% of the interviews were conducted with organisations based in England, 6% in Scotland and 3% in Wales. This exactly replicates the geographical distribution of the larger employer universe.

The final survey data was then weighted back to the true profile of large GB employers, with the weights applied based on a combination of size (employee numbers) and sector.

Qualitative depth interviews

In addition to the main survey, a total of 30 qualitative follow-up interviews were completed during May 2017. These depth interviews were conducted by telephone and lasted an average of 30 minutes.

The sample consisted of respondents to the initial quantitative survey who had given consent to be contacted for further GEO research on the gender pay gap. Interlocking quotas were set on level of engagement with GPG (derived from the survey data[footnote 6]) and size of business. The quotas were intentionally skewed towards employers that were less engaged with GPG, in order to better understand why they did not consider it to be a priority.

The achieved interview profile is set out in the following table.

Table 2: Qualitative interviews by GPG engagement and size

| GPG engagement | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Already taking action or engaged | 3 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| Planning or likely to take action | 3 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| Not taking action or unengaged | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Total | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 |

Further quotas were set on broad sector. Overall, 19 of the qualitative interviews were conducted with the private sector, 6 with the voluntary sector and 5 with the public sector. As far as possible within the constraints of the above quotas, a representative spread was also achieved by SIC and region (including coverage of the devolved administrations).

Following analysis of the main research findings, further qualitative interviews were then conducted among employers who had indicated an intention to publish their GPG results in quarter 1 of the 2016 to 2017 financial year, but who had not yet done so via the GPG reporting portal. The purpose of this additional stage was to understand the reasons for not publishing within the intended timelines. We conducted 22 qualitative interviews lasting 5 to 10 minutes among a cross section of these employers. Results from this additional stage have been referenced at various points in this report, and full details of the methodology, sample and key findings can be found in Annex B.

2.3 Analysis and reporting conventions

This report contains findings from both the quantitative survey and the qualitative follow- up interviews. Where results are based on the qualitative data, this is clearly identified.

Quantitative reporting

Throughout this report, references to ‘all employers’ and the ‘total’ column in the charts and tables refer only to the employer population sampled for the survey – GB private, public and voluntary sector organisations with 250 or more employees.

Unless explicitly noted, all quantitative findings are based on weighted data. Unweighted bases (the number of responses from which the findings are derived) are displayed on tables and charts as appropriate to give an indication of the robustness of results.

The quantitative data presented in this report is from a sample of large employers rather than the total population. This means the results are subject to sampling error.

Differences between sub-groups are commented on only if they are statistically significant at the 95% confidence level (unless otherwise stated). This means that there is at least a 95% probability that any reported differences are real and not a consequence of sampling error.[footnote 7]

When interpreting the data presented in this report, please note that results may not sum to 100% due to rounding or due to employers being able to select more than one answer to a question.

Qualitative reporting

It should be noted that the qualitative phase of the research was based on interviews with a small sample of employers. Although the weight of opinion has sometimes been provided for clarity and transparency, these findings should be treated as indicative and cannot necessarily be extrapolated to the wider population.

Direct quotations have been provided as illustrative examples. However, in some cases these have been abbreviated or paraphrased for the sake of brevity and comprehension (without altering the original sense of the quote).

3. Understanding of the GPG

This chapter explores employers’ awareness and understanding of the gender pay gap. More specifically, it covers:

- awareness of the term “gender pay gap”

- understanding of what the GPG refers to and how it is calculated

- understanding of the difference between closing the GPG and ensuring equal pay between men and women

3.1 Awareness and understanding of the GPG

Overall, almost half (48%) of respondents felt they had a good understanding of what the GPG is and how it is calculated. Only 2% had never heard of the term “gender pay gap”. However, the qualitative interviews suggested that not all of those who claimed good knowledge of GPG actually had a full or correct understanding of this, as discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 1: Self-reported understanding of the GPG

| Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never heard of it | 2% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

| Heard term but don’t know anything about it | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 2% | 1% |

| Limited understanding of what it refers to | 7% | 8% | 5% | 5% | 9% | 8% | 4% |

| Reasonable understanding but not of how it’s calculated | 41% | 41% | 44% | 38% | 43% | 42% | 34% |

| Good understanding of what it is and how it is calculated | 48% | 47% | 49% | 58% | 43% | 47% | 60% |

Base: All respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 0%), Private (406, 0%), Voluntary (243, 0%), Public (251, 0%), 250 to 499 (412, 0%), 500 to 999 (214, 0%), 1,000 or more (274, 0%)

Public sector organisations and those with 1,000 or more employees were most likely to report that they had a good understanding of the GPG (58% and 60% respectively).

However, there were no differences based on the proportion of women on the senior management team, or in the organisation’s workforce as a whole.

Those claiming a good understanding of what the GPG is and how it is calculated were also more likely to have read the GEO and Acas guidance on the subject (76% versus 42% of those with less comprehensive understanding).

Qualitative insight

Evidence from the qualitative interviews provides further detail about levels of understanding of the GPG, how it is calculated and how to interpret it. While some of those claiming a good understanding of what the GPG is and how it is calculated could provide a detailed and accurate description, others were not able to correctly describe this. Their unprompted descriptions were sometimes vague, and sometimes incorrect (mostly due to a confusion between GPG and equal pay).

“It’s measuring the average pay of people doing the same job, making sure it is the same for men and women.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

Many explained that they had been unaware of the definition of the GPG before the new regulations were announced, and their understanding was primarily gained from either reading GEO and Acas guidance on the topic or from attending seminars or training courses run by law firms, recruitment agencies or professional bodies. Those reporting a good prior knowledge had often previously measured their GPG and other related gender statistics. Most were public sector organisations.

“Yes, it is the mean and median pay of men and women in the workforce. It is similar to what we have measured before, but the calculations have changed slightly with the new regulations.” (500 to 999 employees, public sector)

Those reporting limited or no understanding of the GPG and how it is calculated generally explained that they had not yet taken the time to fully engage with the new regulations and associated guidance. They were likely to confuse GPG with equal pay, or in some cases simply state that they were not sure what the GPG was beyond its connection to men and women’s pay.

“Well, that’s a difficult one. I am not sure exactly what it means. We haven’t really given it the time to find out yet.” (1,000 or more employees, voluntary sector)

The qualitative interviews also suggested a lack of understanding about how to interpret GPG data. Some respondents explained that they were unsure exactly what the different measures signified about their workforces and organisations. Others were particularly concerned about how best to present the data to protect their reputations as fair employers.

3.2 Understanding of difference between GPG and equal pay

Almost two-thirds (63%) of respondents believed they had a good understanding of the difference between ‘closing the gender pay gap’ and ‘ensuring equal pay between men and women’. A further 30% knew there was a difference but were not sure of the detail, and just 6% had either not heard of the GPG or did not know it differed from equal pay.

Figure 2: Understanding of the difference between ‘closing the GPG’ and ‘ensuring equal pay’

| Response | Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not heard of GPG | 2% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

| Didn’t know there was a difference | 4% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 6% | 4% | 1% |

| Know there’s a difference but not exactly sure what this is | 30% | 31% | 30% | 22% | 31% | 30% | 26% |

| Good understanding of how they differ | 63% | 60% | 63% | 76% | 57% | 64% | 71% |

Base: All respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 1%). Private (406, 2%), Voluntary (243, 0%), Public (251, 0%). 250 to 499 (412, 2%), 500 to 999 (214, 1%), 1,000 or more (274, 1%)

The proportion with a good understanding was highest among public sector organisations (76%). It also increased in line with size, ranging from 57% of those with 250 to 499 employees up to 71% of those with 1,000 or more employees.

Three-quarters (74%) of those that had read the GEO and Acas guidance on the GPG had a good understanding of how this differed from equal pay (compared to 46% of those not reading the guidance).

It should be considered that this data refers to respondents’ own perceptions of their understanding, and other evidence from this research indicates that this may not always be wholly accurate. A significant proportion did not see closing their GPG as a priority because they already paid equally regardless of gender (see Chapter 5.1), suggesting a degree of conflation between the concepts of GPG and equal pay. This is consistent with the qualitative findings, as discussed below.

Qualitative insight

During the qualitative interviews, when asked to provide a definition of GPG, most respondents included reference to equality of pay between men and women working in the same roles. The difference between GPG and equal pay was not always clearly described, and many respondents felt that the 2 concepts overlapped or explained that they were confused about exactly how they differ.

“It is the difference in pay between men and women, but I am not sure exactly. I think there is a real blurring between this and equal pay.” (1,000 or more employees, public sector)

However, a number of respondents were more informed and explicitly mentioned that GPG was not the same as equal pay.

“Gender Pay Gap is the difference in average pay between men and women, but not just those doing the same job…it is not the same as equal pay.” (250 to 499 employees, voluntary sector)

Some respondents expressed concern that their staff and prospective candidates would not understand the meaning of GPG or how it differs from equal pay. They were worried that if their organisation reported a significant GPG this could be interpreted as them paying men and women different amounts for doing the same job.

“It is definitely a confusing measurement. I am sure that most people would not know the difference between this and equal pay. I am worried about what the staff might think when the numbers are published, whether they will think it means we don’t pay men and women equally.” (1,000 or more employees, private sector)

Some added that without more comprehensive and impactful communication from government on this topic, there was potential for businesses to be viewed negatively by their customers and the public at large.

3.3 Leadership team’s understanding and engagement

When asked specifically about their leadership team or board, most (54%) felt that this group had a ‘fairly’ good understanding of the gender pay gap and the difference between this and equal pay. Only a minority (17%) described their leadership team as having a ‘very’ good understanding of this issue.

Table 3: Leadership team’s perceived understanding of GPG and the difference from equal pay

| Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (unweighted) | 900 | 406 | 243 | 251 | 412 | 214 | 274 |

| Very good | 17% | 17% | 15% | 22% | 14% | 19% | 22% |

| Fairly good | 54% | 53% | 53% | 57% | 54% | 52% | 55% |

| Fairly poor | 19% | 19% | 22% | 14% | 18% | 21% | 18% |

| Very poor | 4% | 4% | 1% | 2% | 5% | 4% | 2% |

| Don’t know | 4% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 6% | 2% | 2% |

| Not heard of the GPG | 2% | 3% | 2% | 0% | 4% | 1% | 1% |

Base: All respondents

Public sector organisations and those with 1,000 or more employees had the most confidence in their leadership team’s understanding of this issue, with more than three-quarters (79% and 77% respectively) judging this to be ‘very’ or ‘fairly’ good.

Qualitative insight

Qualitative exploration suggested that consideration of GPG as a specific issue had not been commonplace in the past. As such, senior management did not always have a clear understanding of the purpose of measuring GPG or the benefit to them or their employees. Engagement in the topic was therefore often said to be limited to, or focused on, how to comply with the regulations and the impact that publishing data would have.

In cases where the leadership team was said to have a strong understanding of the difference between GPG and equal pay, GPG had often been part of a broader strategy to measure and hit targets on diversity and equality. Respondents in these organisations also more commonly described senior leaders as the driving force behind both compliance with regulations and tackling GPG more generally.

“The board are all very aware of this issue, as with gender issues in general. They have implemented a range of policies and strategies in recent years.” (1,000 or more employees, private sector)

“Equality and diversity are really at the heart of everything we do here. The senior team are keen to make sure we measure this type of data and consider the diversity implications of all new policies and procedures.” (500 to 999 employees, public sector)

Some respondents explained that understanding of GPG was inconsistent within their leadership team. They noted that those in the leadership team with an HR or finance focus were more likely to be engaged in, and knowledgeable about, GPG.

HR managers sometimes reported that they had introduced GPG and the new regulations to their leadership team, who would otherwise have been unaware of it. However, a number felt that this information had probably been forgotten by most or all senior managers, and was not likely to be mentioned again until the GPG figures had been shared with them.

“I prepared a report on the dry run data a few months ago, so they know it is coming. But I don’t think they are giving it much thought at the moment.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

In some cases, respondents were unsure what senior manager understood about GPG. Some assumed that board members would have taken time to learn about the issue, while others were more sceptical. These more sceptical respondents explained that the leadership team were either disengaged with topics relating to gender equality in general, or were confident that they did not have a GPG and therefore were simply not concerned about it.

“This is a family business, run in a particular way. The board have lots of other things on their mind. They won’t have given this any thought yet.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

The qualitative interviews provide some evidence that a lack of understanding at board level can directly result in resistance to engagement with GPG and the new regulations. Some senior managers were concerned that their GPG might give the impression that their organisation did not pay men and women equally for doing the same work. They were not sure exactly what would be measured and how, leading to some ‘fear of the unknown’.

“I think some of the senior team were quite concerned about this when they first heard about the regulations. They were worried about being seen as paying unequal wages to men and women. I don’t think they fully understood it.” (500 to 999 employees, private sector)

4. Measuring the GPG and other gender analysis

This chapter looks at the extent to which employers had previously conducted analysis to identify differences between men and women’s pay in their organisation. Specifically, it covers:

- whether employers have calculated their GPG

- whether the GPG was measured in a similar way to that required by the new transparency regulations

- other types of gender analysis carried out

- how the GPG or other gender analysis is communicated and used

4.1 Measuring the GPG

Almost one-third (31%) of organisations had measured their GPG in the last 12 months, although only half (52%) of these respondents knew what their GPG was at the last measurement.

The mean GPG among organisations that had measured it in the last 12 months (n=159) was 14%, compared to the national average of 18%. However, it may be that those voluntarily measuring their GPG prior to the regulations coming into force were more engaged with the topic and therefore not representative of the wider population of large employers. This is supported by the qualitative findings, as discussed later in this chapter.

Figure 3: Employers measuring their GPG in last 12 months

| Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % measured GPG in last 12 months | 31% | 29% | 29% | 40% | 23% | 29% | 47% |

| % of those measuring that knew their score | 52% | 50% | 61% | 55% | 49% | 57% | 52% |

| Mean GPG (if measured) | 14% | 14% | 12% | 17% | 18% | 12% | 13% |

Base: All respondents (Base, Don’t know if measured GPG). Total (900, 7%). Private (406, 7%), Voluntary (243, 8%), Public (251, 3%). 250 to 499 (412, 7%), 500 to 999 (214, 6%), 1,000 or more (274, 7%)

Organisations with 1,000 or more employees were most likely to have measured their GPG (47%). Smaller organisations (250 to 499 employees) were least likely to have done so (23%), but reported the highest mean GPG (18%).

Public sector organisations were also more likely to have measured their GPG, and their mean GPG was higher (17%, compared to 14% for private and 12% for voluntary).

Again, it should be considered that those that had already measured this may not be reflective of all large employers, and may have lower than average GPGs.

There are a number of reasons why the public sector may be more engaged with the GPG issue. Firstly, public bodies with over 150 employees were already reporting on the diversity of their workforce under the Public Sector Equality Duty, and some of the interviewed employers may have undertaken gender pay gap analysis as part of this.

This was supported by the qualitative interviews, which found a particularly formalised and strategic approach to monitoring equality and inclusivity among public sector organisations. Secondly, early compliance with the regulations is arguably more important to the public sector from a reputational perspective.

Respondents who had calculated their GPG were asked a series of questions to determine whether they had done so in a way that was broadly consistent with the approach required under the new government legislation on gender pay transparency.

Four-fifths (80%) had calculated the median pay gap, two-thirds (69%) had presented the difference as a percentage of male average pay and a similar proportion (66%) had calculated it based on hourly pay (rather than annual salary).

Figure 4: Consistency in GPG reporting

80% calculated the median pay gap.

-

4% just calculated the median gap, and 75% calculated both the median and the mean.

-

8% just mean.

-

12% don’t know.

69% presented difference as percentage of male average pay.

-

9% other.

-

22% don’t know.

66% calculated on hourly pay.

-

52% calculated just on hourly pay, and 14% calculated on both hourly and annual pay.

-

26% annual pay.

-

8% don’t know.

Base: All that have measured GPG (Base). Total (291)

As this demonstrates, some organisations calculated their GPG in a way that is not entirely consistent with the mandated approach. However, when the mean GPG was analysed solely based on those using an approach that matches that set out in the regulations, it remained at 14%.

Qualitative insight

Among the qualitative sample, most of those interviewees who had measured their GPG in the previous 12 months had done so as a ‘dry run’ in advance of the regulations coming into force. This suggests that the incidence of ‘true’ voluntary GPG measurement (not driven by the regulations) may be low.

“We did a dip back in December, really just to see if there was anything that we needed to worry about…no, we would not have done that were it not for the regulations.” (500 to 999 employees, private sector)

The small minority of organisations that had measured their GPG for non-regulatory reasons were more focussed on gender and equality issues, and also reported that they were already taking action on GPG.

4.2 Conducting other gender analysis

Respondents were also asked whether their organisation had done any other gender analysis in the last 12 months.

Table 4: Other gender analysis undertaken in last 12 months

| Top mentions only (5% or more) | Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more emloyees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (unweighted) | 900 | 406 | 243 | 251 | 412 | 214 | 274 |

| Proportions of males and females at different levels of pay hierarchy | 41% | 36% | 47% | 65% | 32% | 39% | 59% |

| Proportions of males and females paid bonuses | 31% | 35% | 22% | 16% | 25% | 28% | 46% |

| Difference in average bonuses paid to males and females | 24% | 27% | 17% | 13% | 18% | 21% | 38% |

| Other analysis looking at differences between male and female employees | 31% | 27% | 37% | 50% | 25% | 32% | 42% |

| Not done any other gender analysis | 42% | 46% | 38% | 24% | 50% | 45% | 24% |

Base: All respondents

Over half (58%) of large employers reported that they had had conducted other gender analysis in the previous 12 months. Two-fifths (41%) had analysed the proportions of male and female employees at different pay levels, one-third (31%) had measured the proportions paid bonuses, and one-quarter (24%) had calculated the difference in the average bonuses paid.

One-third (31%) of organisations had also conducted some ‘other’ type of analysis looking at differences between male and female employees. When asked to provide details, the most widely mentioned analyses were assessing the gender balance at different levels of seniority (8% of all organisations), detailed salary bands by gender (5%), the gender balance of new employees (5%) and promotion rates by gender (4%).

Larger organisations with 1,000 or more employees were considerably more likely to have conducted each of the types of gender analysis detailed in Table 4.

Public sector organisations were most likely to have measured the proportions of males and females at different pay levels and undertaken ‘other’ gender analysis. However, private sector organisations were comparatively more likely to have assessed the proportions paid bonuses and the average value of these bonuses. This was particularly true of private sector firms with 1,000 or more employees (54% had analysed the proportion paid bonuses and 46% had calculated the difference in the value of these bonuses by gender).

Those organisations that had measured their GPG in the past 12 months were significantly more likely to have also conducted other types of gender analysis (87% versus 45% of those that had not measured their GPG).

4.3 Communicating and using GPG and other gender analysis

When asked about how they had used any of their GPG or other gender analysis, the most commonly reported actions were sharing results with the leadership team or board (66%) or senior management (62%). A further 38% indicated that it had informed their HR policies or practices and 26% had developed a plan or strategy to address the issues identified.

However, relatively few employers (11%) had communicated or published the results of their gender analysis externally.

Table 5: How employers have communicated and used their GPG or gender analysis

| Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (unweighted) | 597 | 240 | 154 | 203 | 233 | 138 | 226 |

| Shared with leadership team or board | 66% | 62% | 76% | 79% | 59% | 74% | 70% |

| Shared with senior management | 62% | 56% | 70% | 79% | 58% | 64% | 65% |

| Used it to inform or revise HR policy and practices | 38% | 32% | 41% | 58% | 33% | 40% | 42% |

| Developed formal action plan or strategy to address gender issues | 26% | 23% | 25% | 38% | 19% | 28% | 32% |

| Shared with wider workforce | 15% | 9% | 16% | 43% | 13% | 16% | 18% |

| Communicated or published it externally | 11% | 4% | 11% | 42% | 8% | 9% | 16% |

| Other actions | 4% | 3% | 5% | 6% | 2% | 5% | 5% |

| None of these | 14% | 15% | 12% | 8% | 18% | 9% | 11% |

| Don’t know | 3% | 3% | 1% | 0% | 2% | 1% | 4% |

Base: All that have measured GPG or done other gender analysis

Smaller employers and those in the private sector were least likely to have shared the results of any gender analysis with internal audiences (for example, leadership team, senior management, the wider workforce) or to have amended their HR practices as a result.

Public sector organisations were considerably more transparent with their gender analysis, with 42% communicating the results externally and 43% sharing them with their wider workforce. In contrast, only 4% of private sector employers had published their results.

5. Reducing the GPG

This chapter looks at the extent to which employers are seeking to reduce their gender pay gap, and the approaches they are adopting to do so. Specifically, it covers:

- the degree to which reducing the GPG is a priority, and the reasons behind this

- the extent to which employers have developed (and acted on) plans to reduce their GPG

- the specific actions or measures developed to reduce their GPG

- the extent to which the success of these measures is evaluated

- the main challenges or barriers to reducing the GPG

5.1 Priority given to reducing the GPG

There was a broad spectrum of employer attitudes when it came to the perceived importance of reducing their GPG (or ensuring they continued to have no GPG in the long term). Overall, one-quarter (24%) considered this to be a high priority, one-third (37%) a medium priority, one-fifth (21%) a low priority, and 13% judged it not to be a priority at all.

Figure 5: Priority given to reducing the GPG

| Response | Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not a priority at all | 13% | 14% | 13% | 5% | 16% | 13% | 7% |

| A low priority | 21% | 22% | 18% | 18% | 23% | 22% | 15% |

| A medium priority | 37% | 35% | 38% | 45% | 32% | 40% | 43% |

| A high priority | 24% | 24% | 25% | 28% | 24% | 21% | 29% |

Base: All respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 5%). Private (406, 5%), Voluntary (243, 6%), Public (251, 4%). 250 to 499 (412, 5%), 500 to 999 (214, 4%), 1,000 or more (274, 6%)

Public sector organisations and those with 1,000 or more employees were comparatively more likely to allocate a high or medium priority to reducing their GPG (73% and 72% respectively).

Employers with greater female representation at senior management level were less inclined to treat the GPG as a high priority (13% of those where over three-quarters of the management team were female, compared to 26% of those where less than a quarter of the management team were female). This was largely because they did not believe they had a pay gap. This is consistent with the fact that, among those that had measured it, the average GPG was lower among those with a higher proportion of female senior management.

The figure below details organisations’ reasons for the priority given to reducing their GPG. This was captured via an open question, with responses coded into common themes. All reasons mentioned by 5% or more of respondents in each group have been shown.

Figure 6: Reasons for priority given to reducing the GPG (unprompted)

High priority:

- Right thing to do or want to be fair or non-discriminatory – 34%

- Important for us to provide equal pay or opportunities – 21%

- Legal requirement or regulation – 20%

- Important to address our GPG or already working to reduce (or maintain) it – 14%

- Company reputation (for example, image, attracting staff) – 10%

- Want to know reasons or extent of gap or address any issues – 8%

- Have a GPG or gender imbalance in workforce (or certain areas) – 8%

Medium priority:

- Our GPG is small or not a big issue – 14%

- Don’t have a GPG or mainly female workforce – 13%

- Haven’t calculated GPG yet or not sure if it’s an issue – 13%

- Have a GPG or gender imbalance in workforce (or certain areas) – 10%

- Other more important priorities – 9%

- Important to address our GPG or already working to reduce (or maintain) it – 9%

- Right thing to do or want to be fair or non-discriminatory – 9%

- Legal requirement or regulation – 8%

- All workers are paid equally regardless of gender – 7%

- Nothing or little we can do (for example, nature of sector, few female applicants) – 6%

Low priority:

- Don’t have a GPG or mainly female workforce – 24%

- Other more important priorities – 19%

- Nothing or little we can do (for example, nature of sector, few female applicants) – 16%

- Our GPG is small or not a big issue – 15%

- All workers are paid equally regardless of gender – 14%

- Have a set pay scale or structure – 9%

- We employ or pay based on ability not gender or other factors – 8%

- Haven’t calculated GPG yet or not sure if it’s an issue – 5%

Not a priority at all:

- Don’t have a GPG or mainly female workforce – 40%

- All workers are paid equally regardless of gender – 23%

- We employ or pay based on ability not gender or other factors – 14%

- Our GPG is small or not a big issue – 9%

- Other more important priorities – 9%

- Have a set pay scale or structure – 8%

Base: All respondents. High (226), Medium (352), Low (176), Not at all (100). Top mentions (5% or more)

Among those allocating a high priority to reducing their GPG, this decision was primarily driven by moral or ethical considerations, such as a desire to be fair, provide equal opportunities. However, one-fifth of this group (20%) also highlighted the new regulations as a motivating factor.

Very few employers explicitly mentioned profit-related motives for addressing their GPG, suggesting that employers do not typically see a direct link between GPG and business performance. However, some of the more common motivations can be bridges to improved business performance (for example, company reputation).

The perceived lack, or small scale nature, of their GPG was the most significant reason given by those treating it as a medium, low or non priority. However, there also appears to be some confusion between equal pay and the GPG, with 23% of the non-priority and 14% of the low priority group indicating that this was because all their workers were already paid equally regardless of gender.

A significant proportion of employers also identified barriers to reducing their GPG as a reason for affording it a comparatively low priority (for example, there was little they could do due to the broader gender imbalance in their sector, a lack of female applicants, the fact that they had to follow a set pay scale).

Qualitative insight

The qualitative interviews further explored the level of priority afforded to reducing GPG, the reasons for this and who within the organisation was driving this.

In the vast majority of cases, respondents explained that the priority allocated to this issue was ultimately driven by the senior leadership team. HR staff were often said to be the driving force behind compliance with the regulations (see Chapter 6), and in some cases a push to improve opportunities for female staff. However, decisions to change policies and approaches on remuneration, recruitment, working conditions or contracts typically required approval from board members (or equivalent).

“I am not sure what the board will do. We will present the information to them, but it is up to them whether they take action.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

In a minority of cases, organisations (mainly public sector) reported that the strategic priority placed on closing GPG had been assessed along with a raft of other equality and diversity issues. They explained that these priorities were set on an annual basis, based on the perceived severity of the issue. They noted that going forward, the new GPG measurements required under the regulations would form an important source of evidence for these reviews.

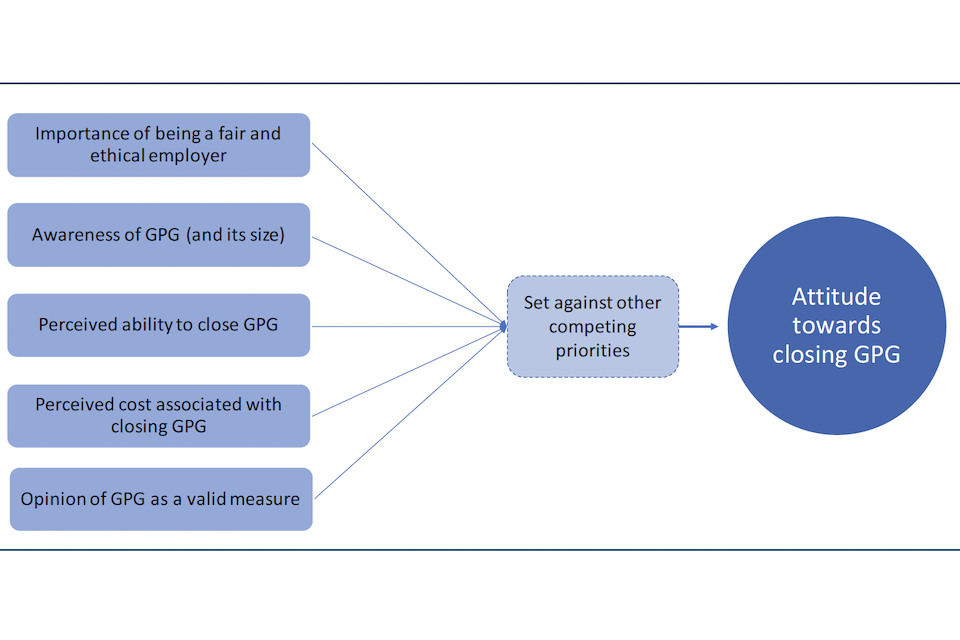

The priority that employers placed on closing their GPG (or ensuring one did not develop) depended on a number of factors. These are illustrated in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7: Factors impacting priority placed on closing GPG

These factors are defined as follows.

Importance of being a fair and ethical employer

The degree to which organisations place importance on looking after their employees and giving them opportunities regardless of their gender or any other defining characteristic.

Awareness of GPG (and its size)

Whether an employer knows (or thinks) it has a GPG, its size, and what is causing it. This will determine its perceived negative impact on staff, reputation, recruitment and sales.

Perceived ability to close GPG

Whether an organisation believes there is anything (more) that they can do to reduce their GPG or avoid one opening up.

Perceived cost associated with closing GPG

What an employer believes the likely costs to them will be of closing their GPG (direct financial costs as well as time and resources associated with taking steps).

Opinion of GPG as a valid measure

Whether employers consider GPG as a ‘valid’ indication of how fair and ethical they are, and therefore whether they feel that closing their GPG is necessary or appropriate.

When considering these factors, it is also important to note that employers usually described multiple reasons for their current GPG priority. Furthermore, their views were often complex and multifaceted. For example, while an organisation might have a strong desire to be a fair employer and see the value in having a low (or no) GPG, it might also assume that it has no significant problem in this area, hence reducing the priority given to the issue.

In addition, the priority afforded to closing their GPG was always set against the relative importance of other issues, challenges and ambitions that the organisation faced. In this context, no employers in the qualitative sample described closing GPG as one of their top priorities overall.

5.2 Attitudes towards reducing the GPG

Qualitative insight

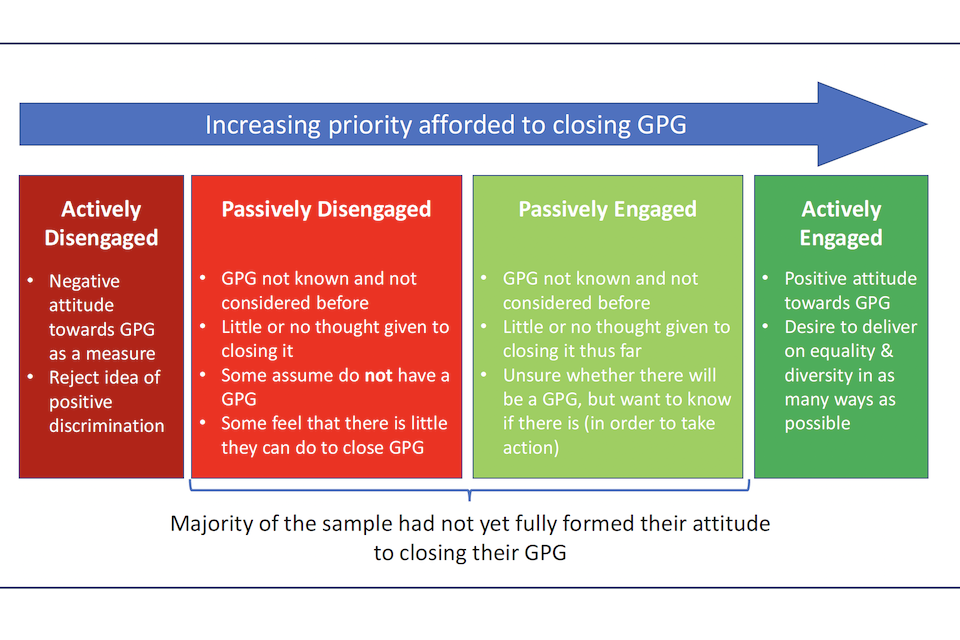

The qualitative research identified 4 broad groups in terms of employers’ attitudes to reducing their GPG, as summarised below.

Figure 8: Range of attitudes towards closing GPG

Actively engaged

A proactive attitude to addressing GPG was described in a minority of cases. These employers described a strong overriding desire to ‘do the right thing’ and be as fair and open as possible. This ambition was driven by the culture of the organisation and, in the case of some charities and public sector bodies, by the strategic priorities set out by senior leaders or trustees.

In some of these more proactive organisations (typically public sector or large employers), monitoring GPG as an indication of equality performance was considered important regardless of whether they had identified a large gap. Some explained that while they had no GPG, they considered it a priority to maintain this scenario (along with other related equality and diversity measures).

In a minority of cases, larger employers were highly motivated to deal with what they felt was an unacceptably high GPG within both their organisation and their sector as a whole. They described motivated senior leaders who were keen to deliver a shift in culture both internally and across the wider population. Others explained that they were keen to address some of the root causes of their GPG (higher rate of female staff turnover) for commercial reasons. For example, some in professional service sectors noted the high cost of training staff and the fact that this investment is ‘lost’ when these staff leave.

Passively engaged

As outlined previously, most employers had not considered GPG as a specific topic before the announcement of the new regulations, and most had not yet calculated and analysed their GPG. As such, many were unsure of the degree to which closing it would be a priority in the future, and described their attitude as one of ‘wait and see’.

These employers broadly accepted that GPG could be another useful measure of their performance in terms of being a fair and ethical employer. As such, they anticipated that were any GPG to exist (which many of this group felt was possible), it would be a priority to deal with it.

They generally recognised the potential benefits associated with reducing their GPG. In some cases, employers described these benefits in ‘altruistic’ terms, with a focus on delivering what is ethically the right thing to do. In others, the motivation to consider closing their GPG related to the potential commercial benefits associated with doing so. They explained the importance of being seen as an employer of choice, enabling them to attract and retain high calibre staff.

A minority anticipated that their (potential) customers were likely to become increasingly interested in knowing their GPG figures. Therefore, the potential to win business could be impacted if their GPG was high compared with the sector. They anticipated that this could have an impact on the priority placed on closing their GPG in the future.

Passively disengaged

Some employers described GPG as an issue that they had not considered before, but thought that they would (probably) not need to address it in the future, beyond meeting their regulatory reporting requirements.

In some cases, employers assumed that they had no GPG to deal with. A small minority had already measured their GPG, but others based this opinion on their high percentage of female employees (including at a senior level) or their rigid pay structure. Some also reported a considerable focus on equality and diversity at a general level, believing that this meant they did not have a GPG to be concerned about. It is important to note that a number of these employers displayed a limited understanding of GPG and how it differed from equal pay.

Other ‘passively disengaged’ employers described a lower GPG priority due to an assumption that they would not be able to close it. While they agreed that tackling GPG was a valid ambition, they argued that a lack of trained or interested female candidates meant that they were unable to address the issue. They often felt that they were already doing all they could to attract more female staff. As such they saw little point in prioritising a goal (reducing GPG) that they were not able to achieve. This attitude was most notable in the manufacturing and engineering sectors.

A lack of engagement with closing the GPG was attributed in some cases to a simple lack of interest in the topic among senior leaders. Some respondents in HR positions felt that their senior managers would simply not take much notice of the GPG data. They explained that their leadership teams were focused on delivering core commercial objectives, with issues relating to equality and diversity a relatively low organisational priority. Some reported that their senior leaders were unlikely to place any importance or urgency on closing their GPG unless they noticed an impact on sales or enquiries.

“If we start seeing that clients are asking about GPG it will become more of a priority.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

Actively disengaged

In a minority of cases, employers described a definitive and deliberate lack of engagement with closing their GPG. Some were not convinced about the validity of seeking to reduce their GPG ‘at all costs’. They felt that the measure failed to take into consideration broader factors such as the availability of women candidates in the sector or other valid reasons for differentials in average pay. They explained that their priority in relation to their (expected) GPG would be to explain rather than reduce it.

“We do not want to just reduce our GPG to get the number down. There can be legitimate reasons for a GPG.” (1,000 or more employees, private sector)

5.3 Approach to reducing the GPG

One-fifth (21%) of employers had developed a formalised action plan for reducing their GPG, but only one-third of this group (6% of all employers) had already implemented any of the specified actions. Half (50%) of all organisations intended to take action but had not yet developed any concrete plans, and one-fifth (20%) did not intend to do anything.

Figure 9: Employers’ current approach to reducing their GPG

| Response | Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No plans to take any action to reduce GPG | 20% | 22% | 17% | 11% | 25% | 16% | 14% |

| Intend to take action but not yet developed specific plans | 50% | 49% | 52% | 53% | 49% | 56% | 45% |

| Developed formalised plan but not yet implemented actions | 15% | 14% | 16% | 20% | 12% | 13% | 23% |

| Developed formalised plan and undertaken some or all actions | 6% | 6% | 6% | 8% | 5% | 5% | 11% |

Base: All respondents (Base, Don’t know). Total (900, 9%). Private (406, 10%), Voluntary (243, 9%), Public (251, 8%). 250 to 499 (412, 10%), 500 to 999 (214, 10%), 1,000 or more (274, 7%)

While still in the minority, large organisations (1,000 or more employees) were most likely to have already developed an action plan (34%). In contrast, one-quarter (25%) of those with 250 to 499 staff had no plans to take any action to reduce their GPG.

As might be expected, there was a correlation between the priority allocated to reducing their GPG and the degree of action taken to achieve this. Two-fifths (39%) of those treating it as a high priority had developed a formalised plan, compared to just 7% of those for whom it was a low or non priority. However, even among the high priority group, only 14% had already undertaken some or all of the actions in their plan.

Employers that had already measured their GPG or undertaken other gender analysis in the previous year were significantly more likely to have put together a formalised plan for reducing their GPG (27% versus 12% of those that had not done any gender analysis).

Those organisations that had or intended to take action to reduce their GPG were asked whether they would publish an action plan for this. As seen in the table below, half (48%) intended to publish this internally (to staff within their organisation) and one-third (33%) intended to make it available to external audiences. While only 16% reported that they definitely would not publish their action plan, a further 29% were unsure as to whether this would happen.

Table 6: Proportion of employers that will publish a GPG action plan

| Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (unweighted) | 662 | 281 | 178 | 203 | 275 | 161 | 226 |

| Yes – will publish externally (annual report, website) | 33% | 29% | 37% | 51% | 28% | 39% | 35% |

| Yes – will publish internally (intranet, staff newsletter) | 48% | 46% | 52% | 60% | 47% | 52% | 47% |

| No – will not publish action plan | 16% | 17% | 16% | 9% | 19% | 16% | 10% |

| Don’t know | 29% | 31% | 24% | 20% | 28% | 24% | 33% |

Base: All that have, plan or intend to take action to reduce their GPG

Although not shown in the table above, one-quarter (23%) of those asked only intended to publish their plan internally (23%), with 7% only publishing externally and 25% doing both. Public sector organisations displayed the most willingness to publish their GPG action plan externally (51%), followed by voluntary sector organisations (37%).

As detailed previously, 21% of employers had developed a formalised plan or strategy to reduce their GPG. In most cases these plans included measures to offer or promote flexible working (71%) and to promote parental leave policies that encouraged both men and women to share childcare (65%).

Figure 10: Measures included in GPG action plan

| Response | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Offering or promoting flexible working arrangements | 71% |

| Promoting parental leave policies that encourage men and women to share childcare | 65% |

| Making cultural changes within your organisation | 51% |

| Voluntary internal targets | 39% |

| Women-specific recruitment, promotion or mentoring schemes | 35% |

| Other | 12% |

Base: All taken or planning action (Base, Don’t know). Total (204, 10%)

The minority of organisations (6%, n=59) that had developed a plan and already undertaken at least some of the specified actions were asked about how and when the impact of these would be evaluated. Most of this group (57%) planned to evaluate the impact as part of a formalised process rather than on an ad hoc basis, and 38% had already assessed the current impact of these actions.

When asked to assess the success of the actions implemented to date, the majority judged them to have been either very successful (23%) or fairly successful (38%). Most of the remainder were unsure or felt it was too early to say.

Qualitative insight

The qualitative sample was structured to cover employers that had or planned to take action to close their GPG and those that did not plan to do so (based on their responses to the quantitative survey). However, the qualitative interviews revealed some confusion and overlap between these 2 groups, often linked to limited knowledge and engagement with GPG.

Those taking or planning action

Qualitative exploration suggested that the level of formalised planning to take action on closing GPG may be even lower than the survey data suggests. Some interviewed employers in this group described plans which had been put in place specifically to address GPG within the organisation. However, others explained that the plans to which they had referred related to much broader gender equality strategies that had not been developed with GPG in mind.

Other employers interviewed in the qualitative stage explained that the action they were referring to (which may help close their GPG) was not part of any formalised plan as such, but rather a series of ad hoc measures. These had been implemented to address a number of issues, including attracting more female staff to the workplace and increasing staff retention in general, as well as promoting and increasing fairness and equality overall.

“We don’t have a specific plan for GPG, but we do a lot to make sure we have a balanced workforce.” (500 to 999 employees, private sector)

In some cases, the plans referred to in the quantitative survey were in fact not related to reducing their GPG per se. Some of these plans were related to complying with the GPG regulations (analysing and reporting the data) rather than reducing their GPG. Others were related to action aimed at eliminating unequal pay practices.

“We went through the process of moving the pay scales to single status a few years ago.” (250 to 499 employees, public sector)

Those not planning to take action

Although this group indicated in the quantitative survey that they were not planning any action to reduce their GPG, further discussion revealed that many had a number of measures in place which could potentially have an impact on GPG, but these were not designed with that purpose in mind. The most commonly mentioned of these measures included offering enhanced maternity or paternity leave and flexible working. However, the impact of these measures on their GPG had not yet been considered or measured.

“We have a good approach to flexible working, but that’s because we want to retain staff overall. We hadn’t thought about the impact on GPG before.” (250 to 499 employees, private sector)

After further discussion and consideration during the qualitative interviews, some agreed that these measures were likely to have had some impact on their GPG (although they had not yet measured this). Others were doubtful that these measures would have made any difference, suggesting that other factors (for example, lack of female candidates, slow turnover of senior staff) were likely to override any impact on their GPG.

Some employers explained that they did not expect to have a GPG and therefore had no plans to take action, but if they completed their calculations and discovered a (bigger than expected) GPG, they would reconsider.

“We have no plans to take action at the moment, but we will definitely approach this in the spirit it is intended and look at what is needed when we know more.” (500 to 999 employees, private sector)

Actions to reduce GPG

Employers described specific activities in relation to reducing their GPG. These closely mirrored those reported in the quantitative survey. They included the following.

Flexible working

Nearly all businesses in the qualitative sample offered flexible working of some kind. Doing so was often part of a general drive to retain staff or to attract and retain female employees. While only rarely described as a measure designed specifically to reduce GPG, a number of employers attributed their perceived low (or zero) GPG at least in part to these practices.

Offering enhanced maternity or paternity leave

Many employers in the qualitative sample offered enhanced maternity and paternity leave (with those who only offered statutory often explaining that this was due to a lack of available funding). They understood that such policies encourage women and men to share childcare responsibilities, and therefore enable women to return to work (sooner). However, shared parental leave was often described as being unpopular among employees and too complicated for them to take advantage of.

Making cultural changes

In a small number of cases, employers in the private sector were taking steps to encourage different attitudes and behaviour among mid-level management in relation to recruitment, professional development and negotiation of wages. They were providing information and guidance, as well as raising the topic in meetings and reviews. They wanted managers to think more about the equality and diversity implications of their staffing decisions. Some were keen to challenge what they considered to be unconscious biases towards hiring other men rather than women or considering men for promotion more readily. Some suggested that they would be able to use the GPG data as evidence to managers of the need for such a change.

Voluntary internal targets

A small minority of employers had put in place targets on the number of women employed in senior positions. The ratio of men to women targeted varied, depending on the starting point and sector (for example, a legal firm aiming for 30% of partners to be women, a voluntary sector care provider aiming for an equal split of men and women in senior positions).

Women-specific recruitment, promotion or mentoring schemes

Some employers had implemented equality or gender initiatives aimed at increasing opportunities for women to join, stay and progress.

A number had mandated that at least one woman should be invited for interview (if possible), while others insisted that there must be female representation on all interview panels. Some large employers also mentioned providing back to work interviews after maternity leave for their female staff.

Others had put in place mentoring programs aimed at encouraging junior female staff to aim for career progression through advice and guidance from women in senior positions in the organisation.

Reaching out to local education institutions was also mentioned. These employers were working with schools to raise awareness of their professions among female students. They felt that this long-term approach was important to combat one of the primary factors driving GPG.

“We try to have 50% women on all candidate shortlists…we insist on a 50/50 split in senior positions.” (500 to 999 employees, voluntary sector)

Measuring impact

The qualitative interviews pointed to a relatively informal approach to measuring the impact of actions to reduce GPG. Respondents were not able to describe any formal assessment processes linking GPG to specific actions or initiatives. They often explained that closing a GPG would take a considerable period of time, and that it would be difficult to attribute any success to specific measures.

However, where formalised plans were in place to encourage women back to work or to encourage more female applicants (both external and internal), employers were monitoring the direct impact on these particular objectives (rather than on GPG).

Furthermore, some explained that now that GPG measurement was mandatory, this would form part of the formalised assessment of these measures in the future.

5.4 Barriers to reducing the GPG

Respondents were asked to give details of the main challenge to reducing their organisation’s GPG, via an open questioning approach. The table below shows all reasons mentioned by 3% or more of respondents.

Table 7: Main challenge to reducing employers’ GPG (unprompted)

| Top mentions only (3% or more) | Total | Private sector | Voluntary sector | Public sector | 250 to 499 employees | 500 to 999 employees | 1,000 or more employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base (unweighted) | 900 | 406 | 243 | 251 | 412 | 214 | 274 |

| Recruiting or attracting or promoting more women | 14% | 15% | 10% | 12% | 12% | 16% | 18% |

| Male dominated sector or business | 10% | 12% | 5% | 3% | 11% | 11% | 8% |

| Financial constraints or cost | 5% | 4% | 10% | 8% | 5% | 5% | 4% |

| Men and women do or apply for different jobs | 5% | 5% | 5% | 10% | 5% | 5% | 6% |

| Gathering or analysing GPG data | 5% | 4% | 6% | 4% | 3% | 6% | 7% |

| Changing organisational culture or educating staff | 4% | 4% | 4% | 3% | 3% | 3% | 6% |

| Women more likely to take career breaks or require flexible working | 3% | 2% | 3% | 6% | 2% | 3% | 4% |

| Lack of understanding or priority at senior level | 3% | 3% | 1% | 2% | 2% | 4% | 3% |

| None – no barriers or challenges | 7% | 7% | 10% | 4% | 7% | 7% | 6% |

| None – don’t have a (significant) GPG | 15% | 16% | 14% | 10% | 18% | 15% | 11% |

| Too early to say or haven’t calculated GPG yet | 9% | 9% | 10% | 10% | 8% | 9% | 10% |

| Don’t know | 15% | 15% | 15% | 18% | 18% | 13% | 12% |

Base: All respondents

A wide array of different challenges were identified by the surveyed organisations. However, the biggest issue related to difficulties in finding or attracting women to the organisation or to certain roles, with 14% mentioning the challenge of recruiting or promoting women, 10% highlighting the male-dominated nature of the sector and 5% identifying the fact that women do (or apply for) different types of jobs. This barrier was particularly prevalent in the construction sector, with 51% of private sector firms operating in this area giving one of these 3 reasons.