Laboratory surveillance of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia (England): 2021

Published 27 February 2023

Applies to England

Introduction

The following analysis is based on voluntary surveillance of diagnoses of bloodstream infections (BSI) caused by Enterococcus spp. reported by laboratories between 2012 and 2021 in England. Voluntary surveillance data for England were extracted on 7 October 2022 from both the communicable disease reporting (CDR) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) modules of the UK Health Security Agency’s (UKHSA) Second Generation Surveillance System (SGSS).

Rates of laboratory reported bacteraemia were calculated using mid-year resident population estimates for the respective year and geography (1). Geographical analyses were based on the patient’s residential postcode. Where this information was unknown, the postcode of the patient’s General Practitioner was used. Failing that, the postcode of the reporting laboratory was used. Cases were further assigned to one of 9 local area regions (UKHSA Centres), formed from the administrative local authority boundaries (2).

The report looks at the trends and geographical distribution of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia cases with further breakdown by species, age and sex. Antimicrobial susceptibility trends are based on SGSS AMR data, and reported for the period 2017 to 2021.

An appendix is available featuring the data behind the findings of this report.

It should be noted that the data presented here for earlier years may differ from those in previous publications due to the inclusion of late reports.

Main points

Principal conclusions of this report are that:

-

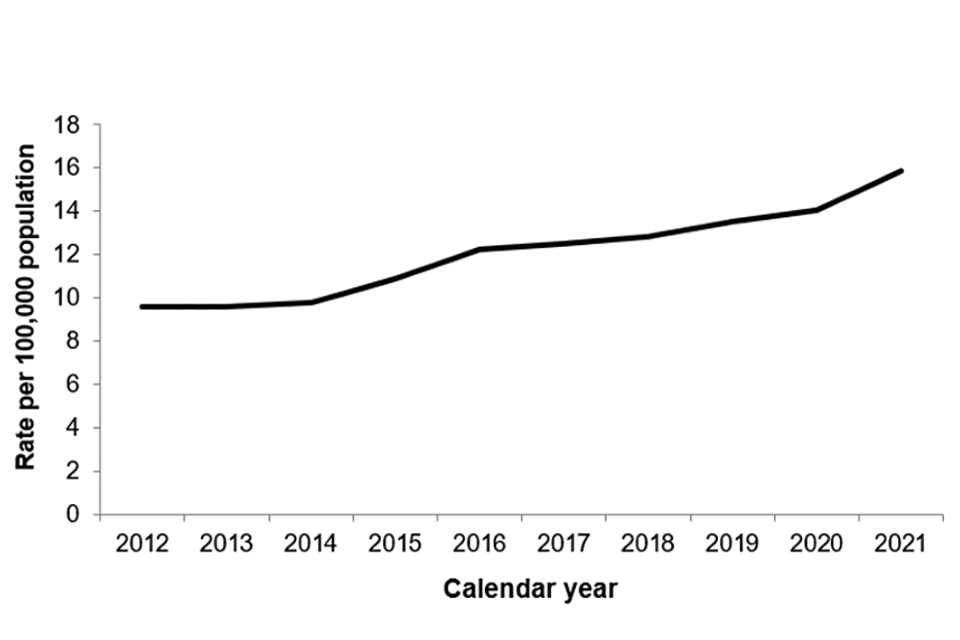

in 2021, the overall rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia in England was 15.9 per 100,000 population, an increase from 14.1 per 100,000 population in 2020, continuing a year-on-year increasing trend since 2012 (9.6 per 100,000 population)

-

the rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia in England increased from 2012 to 2021, unlike other pathogens such as Escherichia coli which increased from 2012 to 2019 but then saw a decrease in 2020 and subsequent increase from 2020 to 2021

-

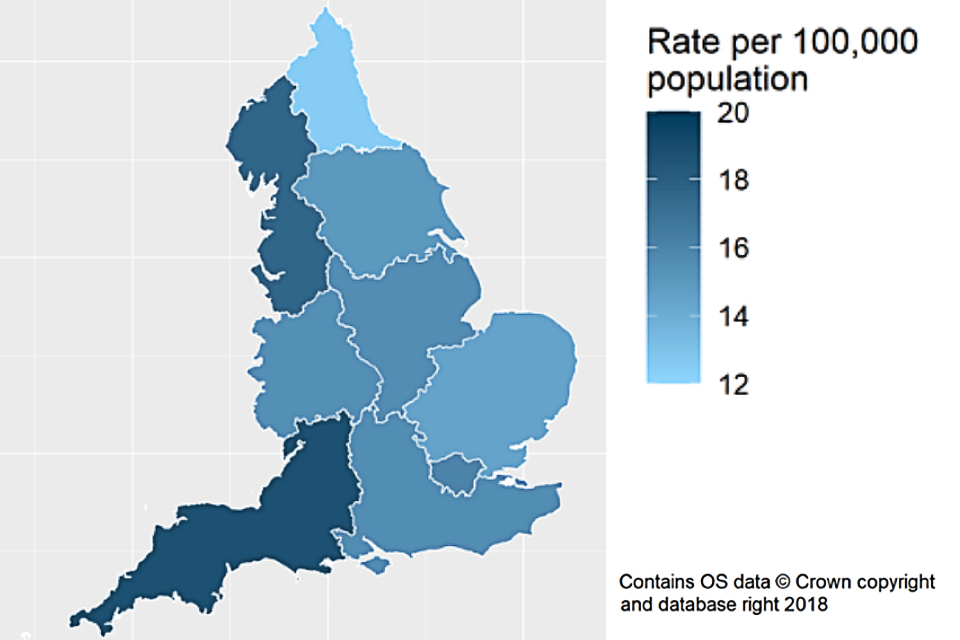

regionally, Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia rates in England ranged from 12.5 per 100,000 population in the North East of England to 18.8 in the South West, with all regions showing an increase in rate from 2020 to 2021

-

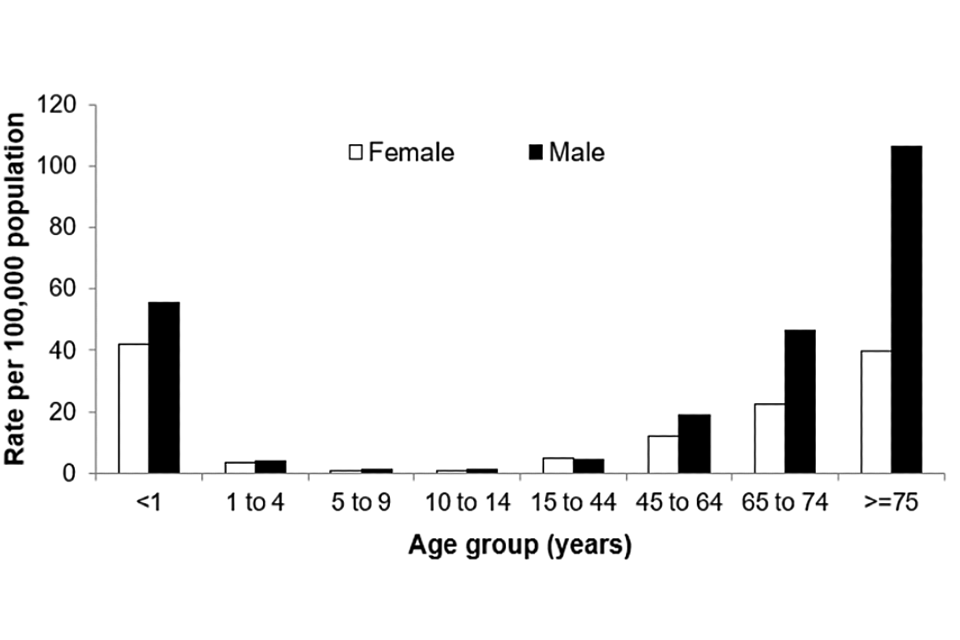

the highest rates of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia were seen in the elderly (over 75 years), with males having a higher rate compared to females (males: 106.4 per 100,000 population and females: 39.8 per 100,000 population)

-

males had a higher rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia in all age groups, except for the 15 to 44 year age group (males: 4.5 per 100,000 population and females 4.8 per 100,000 population)

-

in 2021, the large majority of isolates from enterococcal bacteraemia episodes (90%) were identified to a species level

-

in England in 2021, the most frequently identified Enterococcus spp. from blood was E. faecium (44.5%) followed by E. faecalis (40.5%); this is in contrast to previous years (2017 onwards) where the most frequently identified Enterococcus spp. was E. faecalis

-

antibiotic resistance in E. faecalis was generally low in 2021 when compared to AMR in E. faecium, with the highest resistance to teicoplanin at 2.8%, increasing from 1.9% in 2017

-

resistance of E. faecium to teicoplanin increased from 19.5% in 2020 to 22.1% in 2021 and increased for linezolid from 1.3% in 2020 to 1.9% in 2021; resistance to Ampicillin/Amoxicillin remained high at 92.0%, which has been consistent over the past 5 years

-

the COVID-19 pandemic affected the general case-mix of hospital patients during much of 2020, this has likely impacted trends for the 5-year period

Trends

The rate of bacteraemia caused by the Gram-positive bacterium Enterococcus spp. in England has been increasing year-on-year since 2012 (Figure 1), from 9.6 per 100,000 population in 2012 to 15.9 per 100,000 population in 2021 (an increase of 65.8%). Between 2020 and 2021, the rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia saw the highest yearly increase over the 10-year reporting period (12.7% increase, 14.1 per 100,000 population to 15.9 per 100,000 population).

Figure 1. Rates of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia per 100,000 population in England: 2012 to 2021

Of note, there was an increase in the incidence of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia between 2019 and 2021, unlike other key pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa which experienced a decrease, most likely due to multifactorial effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which commenced in early 2020 (3).

The increase in Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia rates could potentially be due to the increased number of patients being admitted to intensive care units (ICU) and the subsequent risk of ICU-acquired bacteraemia, including those caused by Enterococcus spp. (4). This increase is however likely to be multifactorial.

Table 1. Rates of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia per 100,000 population in England caused by Enterococcus species: 2012 to 2021

| Region / Local Area | Rate in 2017 | Rate in 2018 | Rate in 2019 | Rate in 2020 | Rate in 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 11.7 | 11.0 | 12.8 | 13.2 | 16.0 |

| North East | 11.3 | 12.4 | 12.7 | 12.3 | 12.5 |

| North West | 12.8 | 11.9 | 15.2 | 15.8 | 17.6 |

| Yorkshire and Humber | 9.2 | 13.2 | 12.1 | 12.9 | 15.0 |

| East Midlands | 13.2 | 13.8 | 13.8 | 14.1 | 15.6 |

| East of England | 12.7 | 11.2 | 11.8 | 12.0 | 14.5 |

| West Midlands | 14.2 | 14.5 | 12.8 | 14.3 | 15.5 |

| South East | 12.3 | 12.8 | 13.7 | 15.0 | 15.6 |

| South West | 14.9 | 16.1 | 16.8 | 16.1 | 18.8 |

| England total | 12.5 | 12.8 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 15.9 |

From a public health perspective, England is split into 9 constituent geographical areas (local area region) and 4 geographical regions. In 2021, the local area region with the highest rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia was the South West (18.8 per 100,000) (Figure 2), which has seen the highest rate for the past 5 years (Table 1). The lowest reported rate in 2021 was in the North East of England (12.5 per 100,000 population).

Between 2017 to 2021, all local area regions reported an increase in the rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia; this increase was the highest in Yorkshire and Humber, which saw a 62.5% increase in between 2017 to 2021 (9.2 per 100,000 population to 15.0 per 100,000 population). The lowest increase was seen in the West Midlands, which saw an 8.8% increase between 2017 to 2021 (14.2 per 100,000 population to 15.5 per 100,000 population. To note, variances in reporting, the occurrence of local outbreaks, in addition to diversities in local demographics could potentially account for the differences between different local area regions observed.

Figure 2. Geographical distribution of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia rates per 100,000 population (England): 2021

Species distribution

Ninety per cent of isolates from Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia episodes reported in 2021 were identified to a species level in England, a figure which has been rising year on year (Table 2). The most frequently identified species in 2021 was E. faecium (3,996 reports, 44.5%). This differs from previous years, where the most frequently identified species has been E. faecalis. The second most commonly reported Enterococcus species in England in 2021 was E. faecalis (3,637 reports, 40.5%). This recent replacement of E. faecalis by E. faecium as the predominant enterococcal species in bacteraemia in England has been noted elsewhere (5).

Table 2. Reports of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia by species (England): 2017 to 2021

| Enterococcus species | Reports (%): 2017 | Reports (%): 2018 | Reports (%): 2019 | Reports (%): 2020 | Reports (%): 2021 |

| Total | 6948 (100) | 7174 | 7621 | 7960 | 8972 |

| E. avium | 64 (1.0) | 74 (1.0) | 60 (1.0) | 72 (1.0) | 79 (1.0) |

| E. casseliflavus | 60 (1.0) | 73 (1.0) | 77 (1.0) | 80 (1.0) | 83 (1.0) |

| E. durans | 27 (<1) | 15 (<1) | 16 (<1) | 19 (<1) | 22 (<1) |

| E. faecalis | 3032 (43.6) | 3137 (43.7) | 3290 (43.2) | 3386 (42.5) | 3637 (40.5) |

| E. faecium | 2588 (37.2) | 2795 (39.0) | 3151 (41.3) | 3364 (42.3) | 3996 (44.5) |

| E. gallinarum | 90 (1.3) | 117 (1.6) | 97 (1.3) | 86 (1.1) | 117 (1.3) |

| E. raffinosus | 59 (1.0) | 55 (1.0) | 73 (1.0) | 72 (1.0) | 60 (1.0) |

| Other named ǂ | 36 | 31 | 21 | 11 | 14 |

| Other (not named) | 977 | 859 | 820 | 851 | 945 |

ǂ: Includes E. cecorum, E. columbae, E. gilvus, E. hirae, E. italicus, E. maldoratus, E. mundtii, E. pnoeniculicola, E. saccharolyticus and E. thailandicus.

Age and sex distribution

As noted in previous annual reports, Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia is most prevalent in younger and older age groups (Figure 3) (6).

Figure 3. Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia rates by age and sex (England): 2021

In 2021, as seen in previous years (6), the highest overall rate of bacteraemia caused by enterococci was in persons 75 years old and over (68.6 per 100,000 population overall). This was followed by under 1 year olds (51.3 infections per 100,000 population overall). The overall rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia per 100,000 population in the 1 to 4 year, 5 to 9 year and 10 to 14 year age groups was 3.8, 1.0 and 1.1 per 100,000 population, respectively.

In all ages groups, except in 15 to 44 years, males experienced a higher rate of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia compared to females. Differences between rates in males and females were more noticeable in the older age groups, most noticeable in the over 75 year olds (106.4 per 100,000 population compared to 39.8 per 100,000 population seen in females). Being male or over 70 years old have both been associated with an increased risk of acquiring enterococcal BSI (7).

Antimicrobial resistance: England

Resistance of Enterococcus spp. to glycopeptides (vancomycin or teicoplanin) is monitored in the English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) annual report (8) as it is one of the key pathogen and antimicrobial combinations identified by the Department of Health and Social Care Advisory Committee for Antimicrobial Prescribing, Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (APRHAI).

The 2 most frequently isolated Enterococcus species, E. faecalis and E. faecium, are often considered similar and therefore treated as such. However, E. faecium has been associated with BSI in more severely ill patients and a higher mortality compared to E. faecalis. Resistance rates are also higher (8).

In 2021, antimicrobial resistance in E. faecalis bacteraemia remained rare, at around 2% resistant to several antimicrobial agents (ampicillin/amoxicillin, vancomycin, teicoplanin) and 1% to linezolid (Table 3a). Resistance in E. faecalis to the antimicrobial agents reported here all increased over the 5-year period from 2017 to 2021, with the highest increase seen in resistance to linezolid (0.4% to 1.4% resistant in 2017 to 2021, respectively).

The percentage of E. faecium bacteraemia episodes reported as resistant to glycopeptides from 2017 to 2021 has remained relatively stable, around 21% for both vancomycin and teicoplanin. The percentage of isolates that were resistant to linezolid remained low, at around 2% resistant in 2021 (Table 3b). Resistance of E. faecium to linezolid has increased over the 5-year period – from 0.9% in 2017 to 1.9% in 2021 – but decreased very slightly for vancomycin and teicoplanin over the same time period (21.2% to 21.0% and 22.3% to 22.1%, respectively) (Table 3b).

The switch from E. faecium becoming the more dominant species in England could have significant treatment implications in light of higher resistance rates compared to those seen in E. faecalis BSI.

Table 3a. Antimicrobial susceptibility for E. faecalis bacteraemia isolates (England): 2017 to 2021

Note: E. faecalis samples resistant to ampicillin/amoxicillin have not been confirmed by the reference laboratory and as such are unlikely to be correctly identified as ampicillin/amoxicillin resistance in this species is rare.

Key: ‘S’ = susceptible; ‘I’ = susceptible, increased exposure ; ‘R’ = resistant

| Antimicrobial agent | S (%): 2017 | I (%): 2017 | R (%): 2017 | S (%): 2018 | I (%): 2018 | R (%): 2018 | S (%): 2019 | I (%): 2019 | R (%): 2019 | S (%): 2020 | I (%): 2020 | R (%): 2020 | S (%): 2021 | I (%): 2021 | R (%): 2021 |

| Ampicillin/Amoxicillin | 98 | <1 | 2 | 98 | <1 | 2 | 98 | <1 | 2 | 98 | <1 | 2 | 98 | <1 | 2 |

| Vancomycin | 99 | 0 | 1 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 |

| Teicoplanin | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 97 | <1 | 3 |

| Linezolid | 100 | <1 | <1 | 99 | 0 | 1 | 100 | 0 | <1 | 99 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 0 | 1 |

Table 3b. Antimicrobial susceptibility for E. faecium bacteraemia isolates (England): 2017 to 2021

Key: ‘S’ = susceptible; ‘I’ = susceptible, increased exposure; ‘R’ = resistant

| Antimicrobial agent | S (%): 2017 | I (%): 2017 | R (%): 2017 | S (%): 2018 | I (%): 2018 | R (%): 2018 | S (%): 2019 | I (%): 2019 | R (%): 2019 | S (%): 2020 | I (%): 2020 | R (%): 2020 | S (%): 2021 | I (%): 2021 | R (%): 2021 |

| Ampicillin/Amoxicillin | 9 | 0 | 91 | 9 | <1 | 91 | 9 | <1 | 91 | 8 | <1 | 92 | 8 | <1 | 92 |

| Vancomycin | 79 | 0 | 21 | 78 | 0 | 22 | 79 | 0 | 21 | 81 | 0 | 19 | 79 | 0 | 21 |

| Teicoplanin | 78 | 0 | 22 | 77 | 0 | 23 | 79 | 0 | 21 | 81 | 0 | 19 | 78 | 0 | 22 |

| Linezolid | 99 | 0 | 1 | 99 | 0 | 1 | 98 | 0 | 2 | 99 | 0 | 1 | 98 | 0 | 2 |

Microbiology services

The percentage of reports of enterococcal bacteraemia in which the organism was not fully identified has decreased year on year from 14.1% in 2017 to 10.5% in 2021 (Table 2). As noted previously, the ability to define enterococci at species levels would assist in providing appropriate treatment regimes, in addition to monitoring trends of the most prevalent species, together with emerging enterococci (9).

Laboratories are requested to send any enterococcal isolates with suspected linezolid or tigecycline resistance and isolates that show resistance to teicoplanin but not vancomycin to UKHSA’s Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) Reference Unit for further investigation (amrhai@ukhsa.gov.uk) (9, 10). AMRHAI will also examine isolates with suspected high-level daptomycin MICs (a daptomycin MIC for E. faecium >4mg/L and for E. faecalis >2mg/L), although it should be noted that there are no EUCAST clinical breakpoints. For advice on treatment of antibiotic-resistant infections due to these opportunistic pathogens, laboratories should contact the medical microbiologists at UKHSA’s Bacteriology Reference Department at Colindale.

Acknowledgements

These reports would not be possible without the weekly contributions from microbiology colleagues in laboratories across England, without whom there would be no surveillance data. The support from colleagues within the UKHSA and UKHSA AMRHAI Reference Unit (10) in particular, is valued in the preparation of the report. Feedback and specific queries about this report are welcome and can be sent to hcai.amrdepartment@ukhsa.gov.uk

References

1. Office for National Statistics (ONS). Mid-year population estimates for England, Wales and Northern Ireland

2. UKHSA. UKHSA regions, local centres and emergency contacts

4. Buetti N and others (2021). COVID-19 increased the risk of ICU-acquired bloodstream infections: a case-cohort study from the multicentric OUTCOMEREA network. Intensive Care Medicine: volume 47 issue 2, pages 180-187

5. Horner C and others (2021). Replacement of Enterococcus faecalis by Enterococcus faecium as the predominant enterococcus in UK bacteraemias. JAC-Antimicrobial Resistance: volume 3 issue 4

6. UKHSA (2021). Laboratory surveillance of Enterococcus spp. bacteraemia in England: 2020

7. Billington E and others (2014). Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes for Enterococcus spp. Blood Stream Infections: A Population-Based Study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases: volume 26, pages 76-8

8. UKHSA (2021). English Surveillance Programme for Antimicrobial Utilisation and Resistance (ESPAUR) Report 2020-2021

9. PHE (2021). UK SMI ID4: identification of Streptococcus species, Enterococcus species and morphologically similar organisms

10. UKHSA. Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections (AMRHAI) Reference Unit